Police-reported crime statistics in Canada, 2023

Released: 2024-07-25

Overview

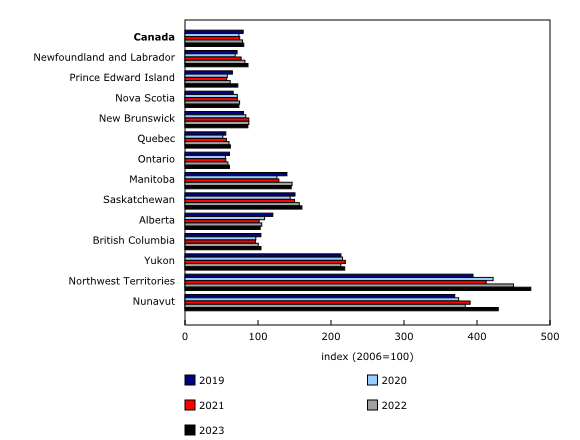

The volume and severity of police-reported crime in Canada, as measured by the Crime Severity Index (CSI), increased for the third consecutive year—up 2% in 2023—an upward trend that began in 2015. Relatively large shifts in certain types of crime led to an increase in the Non-violent CSI, while the Violent CSI remained virtually unchanged.

Understanding and using the Crime Severity Index

The Crime Severity Index (CSI) looks at both the number and the relative severity of crimes. It was developed to complement the conventional crime rate and self-reported victimization data. For detailed information about the methodology of the CSI see the Note to readers.

The CSI is not intended to be used in isolation or as a universal indicator of an area's overall safety. It is best understood in a broad context with other information on community safety and crime, as well as other characteristics, such as population and demographics, labour market conditions and activities, employment and income, and housing and families.

As an area-based index, the CSI does not account for the specific demographics of an area or how different groups of people may experience crime, harm and discrimination. For example, First Nations people, Métis and Inuit are historically overrepresented among victims of homicide, among self-reported victims of violence, and in the criminal justice system.

Area-based measures of crime can potentially gloss over complex systemic issues or may reflect these underlying issues. It is important to consider additional context when interpreting the CSI value for a given area to help also understand the lived experience of people in that area.

Ultimately, the CSI is one piece of a much larger puzzle that helps Canadians better understand the country—its population, resources, economy, environment, society, and culture.

For more information, see the new suite of products Understanding and using the Crime Severity Index, including a video, accompanying infosheet and reference document.

Police-reported crime data for 2023 are now available in the interactive data visualization dashboards through the Police-reported Information Hub. The accompanying infographic, "Police-reported crime in Canada, 2023" is also now available.

Detailed tables with police-reported information by violation and geography (province, territory, and census metropolitan area) are available at the end of this article.

For detailed community profiles and characteristics across Canada from the 2021 Census of Population, see Census Profile, 2021.

The Non-violent CSI—which includes, for example, property offences and drug offences—rose 3% in 2023, following a 5% increase in 2022. A significant contributor to the 2023 increase was a higher rate of police-reported child pornography (+52%).

Increased reporting of child pornography was partially the result of more cases—current and historical—being forwarded to local police services by specialized provincial Internet child exploitation police units and the National Child Exploitation Crime Centre.

Other types of non-violent crime also increased in 2023, including fraud (+12%), shoplifting ($5,000 or under; +18%), and motor vehicle theft (+5%). In contrast, breaking and entering dropped 5% from 2022, continuing a general downward trend in this crime since the 1990s.

The Violent CSI remained virtually unchanged (+0.4%) in 2023, following a 13% cumulative increase over the previous two years. Compared with 2022, the Violent CSI recorded lower rates of homicide (-14%) and sexual violations against children (-10%) in 2023. The Violent CSI also recorded higher rates of extortion (+35%), robbery (+4%) and assault committed with a weapon or causing bodily harm (+7%).

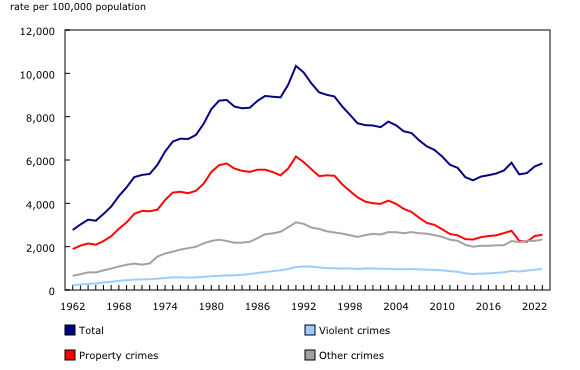

The CSI is one of several measures of crime in Canada. It looks at both the volume and the severity of crime, while the conventional crime rate measures only the volume of crime. In 2023, the police-reported crime rate increased 3% from a year earlier to 5,843 incidents per 100,000 population. While the Violent CSI was essentially unchanged in 2023 primarily because of a decline in lower-volume but more serious crimes—such as homicide—there was a 4% increase in the rate, or total volume, of violent crime, including higher rates of crimes such as assault, robbery and extortion.

Key trends in police-reported crime

Rise in the reported rate of child pornography is the largest contributor to the change in overall Crime Severity Index in 2023

The rate of police-reported child pornography (also sometimes referred to as child sexual exploitation or abuse material) increased 52% in 2023 to 53 incidents per 100,000 population. This increase was the largest contributor to the change in the overall CSI in 2023. Child pornography offences accounted for approximately 5% of the overall CSI value. The year-over-year increase was reflective of a general upward trend since 2008.

There were 21,417 incidents of child pornography reported by police in 2023. Making or distributing child pornography accounted for over three-quarters (76%) of child pornography incidents, while the remaining 24% of such incidents were possessing or accessing child pornography.

Notably, 79% of the increase in child pornography in 2023 was reported in British Columbia, and another 14% was reported in Alberta. Among the provinces, Manitoba reported a decrease.

More cases of child pornography coming to the attention of police

The increase in child pornography in 2023 was partially the result of more cases—current and historical—being forwarded to local police services due to increased public awareness about the topic and partnerships related to combatting and investigating child sexual exploitation and abuse on the Internet. These cases are subsequently reported as police-reported data. For additional information, see the Note to readers.

Majority of child pornography incidents include a cyber component

Relatively high proportions of child pornography and sexual violations against children included a cyber component. For instance, 79% of incidents of child pornography and 20% of sexual violations against children were recorded by police as cybercrimes. In 2023, nearly all (97%) of the increase in child pornography incidents involved those with a cybercrime component.

For a detailed discussion of online child sexual exploitation and abuse, see Online child sexual exploitation: A statistical profile of police-reported incidents in Canada, 2014 to 2022.

Rates of fraud and extortion continue to rise

Fraud—referring here to general fraud and excluding fraud with a specific identity information component (namely, identity theft and identity fraud)—was the second-highest contributor to the change in the CSI in 2023. The 2023 rate of fraud was 12% higher than in 2022, while identity fraud (-6%) and identity theft (-24%) dropped.

Overall, the combined rate of all fraud types (including identity theft and identity fraud) accounted for 9% of the total value of the overall CSI in 2023, behind breaking and entering (15%). There were over 201,000 total incidents of all fraud types in 2023, up from about 91,400 in 2013, resulting in a near-doubling of the rate over the course of a decade (501 incidents per 100,000 population in 2023 versus 260 incidents per 100,000 population in 2013).

Extortion up for fourth consecutive year

Extortion is a relatively serious violent crime that involves obtaining property through coercion and is often associated with fraud. The rate of police-reported extortion (+35% to 35 incidents per 100,000 population) increased for the fourth consecutive year in 2023, following similar increases in the previous three years.

Overall, the rate of extortion was five times higher in 2023 than in 2013, rising from 7 to 35 incidents per 100,000 population.

Almost one-quarter of incidents of all fraud types (24%) and almost half of incidents of extortion (49%) were reported as cybercrimes. Combined, these offences accounted for 60% of cybercrimes in 2023.

Despite the increases in fraud and extortion, many of these crimes go unreported to police. According to the 2019 General Social Survey on Canadians' Safety, just over 1 in 10 victims of fraud (11%) reported the fraud they experienced in the five years preceding the survey to the police.

Rate of breaking and entering is down, while rates of motor vehicle theft, robbery and shoplifting are up

In 2023, the rate of breaking and entering—the most severe type of property crime, according to the CSI—declined 5% from the previous year to 326 incidents per 100,000 population.

Despite the decline, there were still 130,748 incidents of breaking and entering in 2023, accounting for 15% of the total value of the overall CSI, the most of any violation.

Motor vehicle theft has been identified as a key area of concern by the Government of Canada, which hosted the National Summit on Combatting Auto Theft and released the National Action Plan on Combatting Auto Theft in 2024.

Motor vehicle theft up from 2022, but remains about 50% lower than 25 years earlier

In 2023, the rate of motor vehicle theft (286 incidents per 100,000 population) rose for the third year in a row, up 5% from 2022 and 24% higher than its pre-COVID-19 pandemic level. Despite the recent increases, the rate of motor vehicle theft in 2023 was about half of what it was 25 years earlier.

Most of the rate increase in motor vehicle theft in 2023 was recorded in Ontario (+16%) and Quebec (+15%). The three Prairie provinces of Manitoba (425 incidents per 100,000 population), Saskatchewan (464 incidents) and Alberta (411 incidents) recorded decreases in 2023, despite reporting the highest rates overall among the provinces.

Robberies up from 2022, but also remain about 50% lower than 25 years earlier

The rate of robbery—categorized as a violent offence because it involves the use or threat of violence during the commission of a theft—was up for the second year in a row, increasing 4% in 2023. Despite the increase, the rate was 5% lower than in 2019 and 46% lower than 25 years earlier. Overall, 23,651 incidents of robbery were reported in 2023, a rate of 59 incidents per 100,000 population.

In general, while several types of theft have trended down over the last 25 years—for instance, breaking and entering (-72%), motor vehicle theft (-48%) and robbery (-46%)—the rate of shoplifting of $5,000 or under (+28%) has increased. More specifically, following a large decrease at the onset of the pandemic in 2020, shoplifting has increased beyond pre-pandemic levels. In 2023, there were 155,280 incidents, a rate of 387 incidents per 100,000 population. This was 18% higher than in 2022 and 4% higher than in 2019.

Police-reported hate crime rises sharply for third time in four years

Hate crimes target the integral and visible parts of a person's identity and may affect not only the individual but also the wider community.

The number of police-reported hate crimes increased from 3,612 incidents in 2022 to 4,777 in 2023 (+32%), even though some victims might not report a hate crime they experienced. This followed an 8% increase in 2022, and a 72% increase from 2019 to 2021. Overall, the number of police-reported hate crimes (+145%) has more than doubled since 2019.

Higher numbers of hate crimes targeting a religion (+67%; 1,284 incidents) or a sexual orientation (+69%; 860 incidents) accounted for most of the increase in 2023. Additionally, hate crimes targeting a race or an ethnicity were up 6%. Most of the violations typically associated with hate crimes increased, including public incitement of hatred (+65%), uttering threats (+53%), mischief (+34%) and assaults (+20%).

According to the 2019 General Social Survey on Canadians' Safety (Victimization), Canadians self-reported being victims of over 223,000 criminal incidents that they perceived as being motivated by hate in the 12 months preceding the survey. Among these victims, approximately one in five incidents was reported to the police.

National homicide rate declines after four consecutive annual increases

Police reported 778 homicides in 2023, 104 fewer than a year earlier. The homicide rate declined 14%, from 2.27 homicides per 100,000 population in 2022 to 1.94 in 2023. The homicide rate dropped below 2 homicides per 100,000 people for the first time since 2019.

The drop in homicides was the primary reason for the Violent CSI being lower than it otherwise would have been and accounted for half of its decreasing portion.

Homicide counts vary by region

The national decrease in 2023 was largely the result of fewer homicides throughout much of the country, including British Columbia (-32 homicides), Ontario (-30 homicides), Manitoba (-15 homicides), Saskatchewan (-14 homicides), Quebec (-10 homicides), New Brunswick (-6 homicides), Nova Scotia (-5 homicides) and Alberta (-4 homicides).

However, in 2023, there were more homicides reported in Newfoundland and Labrador (+5 homicides), Prince Edward Island (+1 homicide) and in all three territories: Yukon (+2 homicides), the Northwest Territories (+3 homicides) and Nunavut (+1 homicide).

Detailed information on homicide counts, rates and victim characteristics can be found in the Police-reported Information Hub: Homicide in Canada, an interactive data visualization dashboard.

Rates of homicide victims higher among Indigenous people and racialized groups

Police reported 193 Indigenous homicide victims in 2023, 35 fewer than in 2022. Almost three-quarters (73%) of Indigenous homicide victims were identified by police as First Nations people, while 3% were identified as Métis and 5% as Inuit. A specific Indigenous group (First Nations people, Métis and Inuit) was not identified by police for 20% of Indigenous homicide victims.

The homicide rate for Indigenous people was over six times higher than for the non-Indigenous population (9.31 versus 1.46 homicides per 100,000 population). Since 2014—the first year for which complete information regarding Indigenous identity was reported for victims of homicide—Indigenous people have been overrepresented as victims of homicide.

Nearly one-third of homicide victims identified by police as racialized

There were 235 victims of homicide identified by police as racialized (those identified as belonging to a visible minority group, as defined by the Employment Equity Act), accounting for 30% of homicide victims in 2023.

The rate of homicide for the racialized population was lower than the previous year, down 19% from 2.44 homicides per 100,000 population in 2022 to 1.98 homicides per 100,000 population in 2023. This rate was higher than the rate in 2023 for the non-racialized population (1.90 homicides per 100,000 population). Almost two out of five racialized victims (39%) were identified by police as Black, and another 20% were identified as South Asian.

Did you know we have a mobile app?

Download our mobile app and get timely access to data at your fingertips! The StatsCAN app is available for free on the App Store and on Google Play.

See the Note to readers below for more information on homicide victim identification.

Note to readers

Uniform Crime Reporting Survey

Police-reported crime data (other than detailed information on homicides) are drawn from the Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR) Survey, a census of all crime known to police services. Police-reported crime statistics conform to a nationally approved set of common crime categories and definitions. They have been systematically reported by police services and submitted to Statistics Canada every year since 1962. Differences in local police service policies, procedures and enforcement practices can affect the comparability of crime trends.

Revisions to the UCR Survey are accepted for a one-year period after the data are initially released. For example, when the 2023 crime statistics are released, the 2022 data are updated with any revisions that have been made between May 2023 and May 2024. The data are revised only once and are then permanently frozen. Over the past 10 years, data have been revised upward 10 times, with an average annual revision of 0.38%. Additionally, the 2022 revision to counts of people charged and youth not charged resulted in a 0.56% increase to 2022 counts.

See "Definitions" for detailed explanations of common concepts and terminology used in the analysis of police-reported crime information.

Understanding the Crime Severity Index

The conventional crime rate and the Crime Severity Index (CSI) are two complementary ways to measure police-reported crime. The crime rate measures the volume of crime per 100,000 population, including all Criminal Code violations (except traffic violations). The CSI measures both the volume and the severity of crime and includes all Criminal Code and other federal statute violations. The CSI has a base index value of 100 for 2006. Both the conventional crime rate and the CSI measure crime based on the most serious violation in the criminal incident.

The CSI was developed to address the limitation of the police-reported crime rate being driven by high-volume, but relatively less serious, crimes. The CSI considers not only the volume of crime, but also the relative severity of crime. Therefore, the CSI will vary when changes in either the volume or the average severity—or both the volume and the average severity—of crime are recorded.

To determine severity, each crime is assigned a weight. CSI weights are based on the crime's incarceration rate, as well as the average length of prison sentences handed down by criminal courts. More serious crimes are assigned higher weights, while less serious crimes are assigned lower weights. As a result, relative to their volume, more serious crimes have a greater impact on the index.

For more information on concepts and the use of the Crime Severity Index, see the report "Measuring Crime in Canada: Introducing the Crime Severity Index and Improvements to the Uniform Crime Reporting Survey" (85-004-X) and the new suite of products for Understanding and using the Crime Severity Index, including a video, accompanying infosheet and reference document.

Police-reported child pornography

The offence of "child pornography" includes offences under section 163.1 of the Criminal Code, which makes it illegal to access, possess, make, print, or distribute child pornography. When the actual victim is not identified, this offence is reported to the UCR Survey with the most serious offence being "child pornography," which falls under the larger crime category of "other Criminal Code offences." In cases where an actual victim is identified, police will report the most serious offence as sexual assault, sexual exploitation or other sexual violations against children, which fall under the category of "violent crimes," and child pornography may be reported as a secondary violation.

Because of the complexity of cyber incidents, which represent a significant number of incidents of child pornography, these data likely reflect the number of active or closed investigations for the year rather than the total number of incidents reported to police. Data are based on police-reported incidents that are recorded in police services' records management systems.

Like with all crime, incidents of child pornography are subject to changes in the occurrence of incidents, as well as public awareness and policing practices. A variety of public safety initiatives at all levels of government, along with increased public awareness and changes in policies and technologies available to social media companies have contributed to increases in reports of child pornography incidents to police. As public awareness continues to increase, police services are reporting increases in recent and historical incidents which may also impact annual reporting of these criminal violations.

Additionally, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) National Child Exploitation Crime Centre (NCECC) serves as the primary point of contact in Canada for investigations related to sexual exploitation of children on the Internet. The NCECC and specialized provincial Internet child exploitation policing units also work in partnership with local police services and jurisdictions.

Within this partnership, cases may be forwarded to local police services for processing and investigation. As a result of this exchange, there may be delays in reporting current or historical incidents of child pornography. This means that the year in which incidents are reported may not correspond to the year in which they occurred.

The NCECC also serves as the national law enforcement arm of the National Strategy for the Protection of Children from Sexual Exploitation on the Internet.

In 2019, Public Safety Canada announced the expansion of the national strategy with increased funding over three years to support awareness of online child sexual exploitation, reduce the stigma of reporting, and increase Canada's ability to pursue and prosecute offenders of sexual exploitation of children online.

Police-reported cybercrime

A criminal incident may include multiple violations of the law. For the analysis of cyber-related violations, one distinct violation within the incident is identified as the "cybercrime violation." The cybercrime violation represents the specific criminal violation in an incident in which a computer or the Internet was the target of the crime, or the instrument used to commit the crime. For the majority of incidents, the cybercrime violation and the most serious violation were the same.

Homicide Survey

Detailed information on the characteristics of homicide victims and accused persons is drawn from the Homicide Survey, which collects police-reported information on the characteristics of all homicide incidents, victims and accused persons in Canada. This survey began collecting information on all murders in 1961 and was expanded in 1974 to include all incidents of manslaughter and infanticide. The term "homicide" is used to refer to each single victim of homicide. For instance, a single incident can have more than one victim. For the purpose of this article, each victim is counted as a homicide. Detailed homicide statistics can be found in data tables available online.

Indigenous identity is reported by police to the Homicide Survey and is determined through information found with the victim or accused person, such as status cards, or through information supplied by victims' families, by community members or from other sources (i.e., band records). Forensic evidence such as genetic testing results may also be an acceptable means of determining the Indigenous identity of victims. Given the potential limitations of secondary identification, victim identification may be underreported. Indigenous identity—whether the victim was Indigenous or not—was reported as unknown for 4% of homicide victims.

For the purposes of the Homicide Survey, Indigenous identity includes people identified by police as First Nations people (either status or non-status), Métis or Inuit, and people with an Indigenous identity whose Indigenous group is not known to police. Non-Indigenous identity refers to instances where the police have confirmed that a victim is not an Indigenous person. Indigenous identity reported as "unknown" by police includes instances where police are unable to determine the Indigenous identity of the victim or where the Indigenous identity is not collected by the police service. For more information and context on victimization of Indigenous people, see for example, the following articles: "Violent victimization and perceptions of safety: Experiences of First Nations, Métis and Inuit women in Canada;" "Victimization of First Nations people, Métis and Inuit in Canada;" "Understanding the Impact of Historical Trauma Due to Colonization on the Health and Well-Being of Indigenous Young Peoples: A Systematic Scoping Review;" "Reclaiming Power and Place: The Final Report on the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls;" and "Summary of the Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada."

In this article, data on racialized groups are measured with the visible minority variable. The non-racialized group is measured with the category "not a visible minority" for that variable, excluding Indigenous people. "Visible minority" refers to whether a person belongs to a visible minority group as defined by the Employment Equity Act. The Employment Equity Act defines visible minorities as "persons, other than Aboriginal peoples, who are non-Caucasian in race or non-white in colour." Groups designated as visible minorities include, among others, South Asian, Chinese, Black, Filipino, Arab, Latin American, Southeast Asian, West Asian, Korean and Japanese.

Self-reported information

Police-reported metrics include only incidents that come to the attention of police, either through reporting by the public or proactive policing. As a complementary measure, results from the 2019 General Social Survey (GSS) on Canadians' Safety (Victimization) found that under one-third (29%) of violent and non-violent incidents were reported to the police. Similarly, over one-fifth (22%) of incidents perceived to be motivated by hate were reported to police. The number of sexual assaults reported by police is also likely a significant underestimation of the true extent of sexual assault in Canada, since these types of offences often go unreported to police. Results from the 2019 GSS on Victimization show that 6% of sexual assault incidents experienced by Canadians aged 15 and older in the previous 12 months were brought to the attention of police.

Available tables

Homicide statistics: 35-10-0060-01, 35-10-0068-01 to 35-10-0075-01, 35-10-0119-01, 35-10-0125-01 to 35-10-0127-01, 35-10-0156-01, 35-10-0157-01, 35-10-0170-01 and 35-10-0206-01 to 35-10-0208-01.

Police-reported crime statistics and Crime Severity Index: 35-10-0001-01, 35-10-0002-01, 35-10-0026-01, 35-10-0061-01 to 35-10-0064-01, 35-10-0066-01, 35-10-0067-01 and 35-10-0177-01 to 35-10-0191-01.

Products

Data for 2023 are now updated in the interactive data visualization dashboards "Police-reported Information Hub: Selected Crime Indicators," "Police-reported Information Hub: Criminal Violations," "Police-reported Information Hub: Geographic Crime Comparisons," and "Police-reported Information Hub: Homicide in Canada," available through the "Police-reported Information Hub" as part of the publication Statistics Canada – Data Visualization Products (71-607-X).

The infographic "Police-reported crime in Canada, 2023" (11-627-M) is also released today.

Additional data, such as detailed microdata, are available upon request.

Contact information

For more information, or to enquire about the concepts, methods or data quality of this release, contact us (toll-free 1-800-263-1136; 514-283-8300; infostats@statcan.gc.ca) or Media Relations (statcan.mediahotline-ligneinfomedias.statcan@statcan.gc.ca).

- Date modified: