Victimization of First Nations people, Métis and Inuit in Canada

by Samuel Perreault, Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics

Highlights

- Due to the historical and intergenerational trauma resulting from colonialism and related policies, as well as individual and systemic racism, many Indigenous people today—that is, those who are First Nations, Métis or Inuit—face a number of deeply rooted social and economic challenges, including higher rates of criminal victimization.

- According to self-reported data from the 2019 General Social Survey on Canadians’ Safety (Victimization), about 4 in 10 Indigenous people experienced sexual or physical violence by an adult before the age of 15. The proportion was about twice as high among Indigenous people aged 55 and older (54%) compared with those aged 15 to 34 (26%).

- Child welfare services or police were about three times more likely to have been made aware of violence experienced by Indigenous children, compared to violence experienced by non-Indigenous children (16% versus 5.2%).

- Indigenous people aged 15 and older were nearly 10 times more likely than non-Indigenous people to have been under the legal responsibility of the government during their childhood (11% versus 1.3%). This overrepresentation in child welfare services could only be partially explained by the higher rates of child maltreatment or neglect.

- More than one-third of those who experienced sexual or physical violence while under the legal responsibility of the government during their childhood were Indigenous.

- More than one-quarter (26%) of Indigenous women experienced sexual violence by an adult during their childhood, compared with 9.2% of non-Indigenous women, 5.8% of Indigenous men and 2.8% of non-Indigenous men.

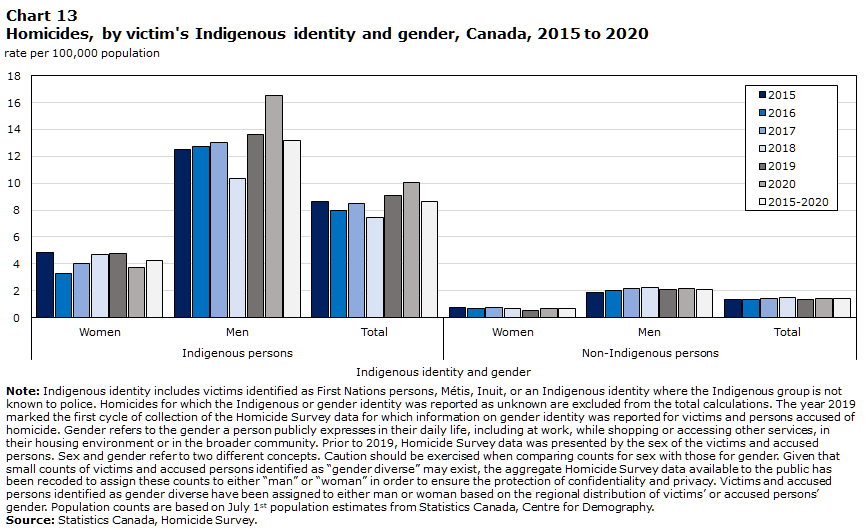

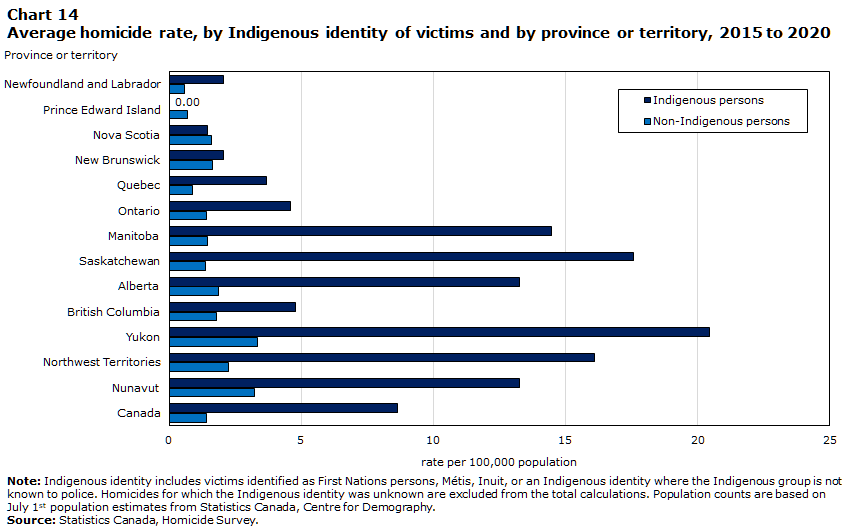

- For the period from 2015 to 2020, the average homicide rate involving Indigenous victims (8.64 per 100,000 Indigenous people) was six times higher than the homicide rate involving non-Indigenous victims (1.39 per 100,000 non-Indigenous people). The homicide rates for Indigenous people were particularly high in the Prairie provinces and in the territories.

- Nearly half (47%) of Indigenous women aged 15 and older who were murdered between 2015 and 2020 were killed by an intimate partner, a proportion similar to that of non-Indigenous women (49%), but much higher than for Indigenous men (7.3%) and non-Indigenous men (4.6%).

- In 2019, nearly 1 in 10 (8.4%) Indigenous people were victims of sexual assault, robbery or physical assault, about twice the proportion of non-Indigenous people (4.2%).

- Violence experienced during childhood is closely linked to the risk of violent victimization in adulthood. For example, more than one-quarter (27%) of Indigenous people who experienced sexual violence by an adult before the age of 15 were victims of a violent crime in 2019, compared with 3.7% of Indigenous people who did not experience violence during childhood.

- Among respondents aged 15 to 34, relatively similar proportions of Indigenous people (8.8%) and non-Indigenous people (7.3%) were victims of violence in the 12 months preceding the survey. However, among those aged 35 to 54, the proportion was three times higher among Indigenous people (12.4%) than among non-Indigenous people (3.9%).

- One-third of Indigenous people experienced discrimination in the five years preceding the survey. They were also more likely to have been the victim of a violent crime—14.9% of Indigenous people who experienced discrimination were victims of a violent crime in 2019, compared with 5.1% of Indigenous people who had not suffered discrimination.

- When taking key socioeconomic indicators into account, as well as factors related to social cohesion (e.g., trust in neighbours, discrimination), health (e.g., mental health, drug use) and history of child abuse and homelessness, Indigenous people were not at a higher risk of victimization than non-Indigenous people.

- Almost 4 in 10 (39%) Indigenous victims reported the most serious sexual or physical assault (excluding intimate partner violence) they experienced to police, more than twice the proportion of non-Indigenous victims who reported their victimization to police (18%). Indigenous victims were also more likely to have faced an armed assailant, to have been injured and to have used victim services.

- A little more than 1 in 10 (13%) Indigenous people with a current or ex-intimate partner experienced violence from their partner in the five years preceding the survey, a proportion twice as high as non-Indigenous people (5.7%).

- Over a 10-year period, the proportion of Indigenous women who experienced violence from a current or former spouse or common-law partner in the five years preceding the survey has decreased; in the provinces, it fell from 15%E in 2009 to 7.5% in 2019.

- Compared to non-LGBTQ2+ non-Indigenous people, LGBTQ2+ Indigenous people were more likely to have been sexually or physically assaulted by an adult when they were under age 15 (58% versus 26% of non-LGBTQ2+ non-Indigenous people), to have been sexually or physically assaulted since age 15 (82% versus 41%), and to have experienced intimate partner violence (37% versus 13%), or non-intimate sexual or physical assault in the 12 months preceding the survey (28% versus 5.9%).

- Indigenous people (17%) were about twice more likely than non-Indigenous people (9.2%) to have little or no confidence in their local police service. The differences between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people in this regard were greatest in Saskatchewan and in the territories.

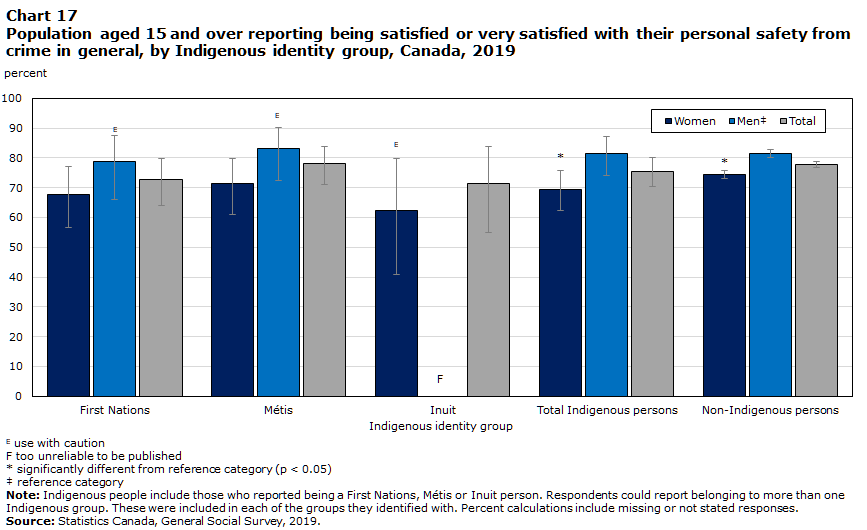

- Overall, similar proportions of Indigenous and non-Indigenous people reported feeling safe when walking alone in their neighbourhood after dark.

In recent years, several studies have shown that First Nations people, Métis and InuitNote are more likely than non-Indigenous people to have experienced violence during their childhood (Burczycka 2017), to have been sexually or physically assaulted (Boyce 2016; Cotter and Savage 2019; Perreault 2020), to have been victims of violence by an intimate partner (Heidinger 2021; Boyce 2016), or to have been victims of homicide (Armstrong and Jaffray 2021; Moreau 2021).

Due to the historical and ongoing colonialism and related policies—including the experiences of residential schools and the Sixties Scoop—as well as individual and systemic racism, many Indigenous people today deal with intergenerational trauma, socioeconomic marginalization. Both the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls and the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada indicated that persistent and deliberate human and Indigenous rights violations and abuses are the root cause behind Canada’s staggering rates of violence against Indigenous people (National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation 2015; National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls 2019).

To provide the most comprehensive picture of violent victimization among First Nations people, Métis and Inuit, the analyses in this article are based on various Statistics Canada data sources to measure the nature and extent of criminal victimization of Indigenous people.

The first two sections of the article use self-reported data from the 2019 General Social Survey (GSS) on Canadians’ Safety (Victimization) to provide a picture of childhood victimization and the nature and extent of violent victimization in the 12 months preceding the survey, including intimate partner violence. The third section outlines the main characteristics of violent crimes against Indigenous people using self-reported data from the 2018 Survey of Safety in Public and Private Spaces (SSPPS). Based on police-reported data from the Homicide Survey, the fourth section shows the key trends and characteristics of homicides involving Indigenous victims from 2015 to 2020. Finally, the fifth part briefly presents Indigenous people’s perceptions of the criminal justice system and their personal safety using 2019 GSS data.Note

Due to the ongoing concern of the victimization of Indigenous women, highlighted by the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls, a detailed analysis on victimization of Indigenous women is presented in a separate article (see Heidinger 2022).

Experiences of victimization during childhood

The recent media coverage about unmarked graves of Indigenous children who died while attending residential schools brought again to the forefront the violence and mistreatment experienced by many Indigenous peoples throughout history. In addition to the mistreatment that many Indigenous persons personally suffered as children, there is also the intergenerational transmission of the trauma that these experiences have caused.

The Sixties Scoop, in which many Indigenous children were forcibly removed from their communities by child protective services and placed in the care of non-Indigenous families, and other practices that resulted in Indigenous children being separated from their families and communities, also affected the childhood of many Indigenous people, including mistreatment in their new families and the loss of cultural references. Still today, Indigenous children are overrepresented in child welfare services and foster families, and many argue that the current child welfare system is the continuation of the residential school system and the Sixties scoop (Blackstock 2007; Choate et al. 2021; National Collaborating Centre for Indigenous Health 2017a). Indigenous people who were taken from their families as a child may have been exposed to weak parenting models in their foster families, and may have missed opportunities to learn positive parenting skills, including traditional parenting practices (Bombay et al. 2009).

In addition, many studies have established a link between disadvantage in terms of resources and a greater vulnerability to childhood violence or maltreatment (Lefebvre et al. 2017; Rothwell et al. 2018; Patwardhan et al. 2017; Paxson and Walfogel 1999). However, many Indigenous communities and Indigenous people face limited and inequitable access or barriers (e.g., cultural barriers) to a wide range of services, including health, education and employment services, which likely impacts their socioeconomic and health circumstances (National Collaborating Centre for Indigenous Health 2019, 2017b and 2017c). For example, GSS data shows that Indigenous people were more likely than non-Indigenous people to report that some services, such as shelters or transition homes, were not available in their area (17% versus 7.9%). Typically, those barriers are more frequent in rural or remote areas, where geography and population size may also pose challenges in terms of services availability.

In part by consequence of the various factors documented above, and deeply rooted within the historical and ongoing effects of colonialism, many Indigenous people face socioeconomic challenges. For example, 2016 Census data shows that Indigenous total average income was $36,043, compared to $47,981 for non-Indigenous people.Note GSS data also show that 22% of Indigenous people reported they have been unable to pay scheduled bills or make other payments in the 12 months preceding the survey, compared with 10% of non-Indigenous people. Another study noted that 26% of Inuit, 24% of First Nations people and 11% of Métis live in a dwelling in need of major repairs, compared with 6.0% of non-Indigenous people (Statistics Canada 2018). Moreover, 18% of Indigenous people live in an overcrowded dwelling, compared with 8.5% of non-Indigenous people. The same study also highlighted that Indigenous people were much more likely than non-Indigenous people to experience food insecurity.

Despite these challenges, Indigenous people also benefit from several social factors that can mitigate the risk of violent victimization. For example, GSS data show that 27% of Indigenous people report a very strong sense of community belonging (compared with 21% of non-Indigenous people), 33% said they know most people in their neighbourhood (versus 15%), and 85% said their neighbourhood was a place where people help each other. In addition, Indigenous people were more likely to report that their spiritual beliefs were very important to the way they live their life (35% versus 28% of non-Indigenous people). These indicators may be reflective of strong social cohesion, which is known to be a protective factor from criminal victimization (Fitzgerald and Carrington 2008; Rhineberger-Dunn and Carlson 2011; Sampson et al. 1997). In addition, some socioeconomic gaps may be narrowing. For example, the proportion of Indigenous people aged 20 to 24 with a high school diploma increased from 57% in 2006 to 70% in 2016, although a large gap still remains compared to non-Indigenous people from the same age group (91%) (Anderson 2021).

In 2014, questions were added to the GSS to measure childhood experiences of sexual or physical abuse perpetrated by an adult. It is important to note that these data reflect the childhood experiences of people aged 15 and over, and may not be representative of current child maltreatment. In 2014, results showed that, overall, Indigenous people aged 15 and over were 1.4 times more likely than non-Indigenous people to have experienced sexual or physical abuse as children (Burczycka 2017).

In addition to sexual and physical violence, childhood maltreatment can also include exposure to spousal violence, and experiences of neglect and harsh parenting. In 2019, more detailed questions, including questions about these types of maltreatment, were added to the GSS to better measure the nature and extent of childhood maltreatment and its impact in adulthood.

Previous studies revealed that experiencing violence during childhood was associated with various issues in adulthood, such a greater likelihood of reporting mental health problems, substance abuse, contact with the police and victimization experiences, as well as a greater risk of experiencing serious emotional or psychological consequences from victimization (Bombay et al. 2009; Boyce et al. 2015; Burczycka 2017, Cotter 2021; O’Neil et al. 2018; Perreault 2015; Scott 2007). Child abuse is rarely reported to police, and as such, self-reported retrospective measures as in the GSS are among the few available means to quantify the issue (Burczycka 2017).

Indigenous people more likely to report having experienced certain parenting practices or had basic needs unmet

The GSS covers a wide range of behaviours of varying severity that may be defined as harsh or severe parenting practices. These include spanking, slapping on the hand, saying hurtful comments and making children feel unwanted or unloved. Although harsh parenting may appear to be less serious than criminal behaviours such as sexual or physical violence, it is nevertheless closely linked to the risk of victimization in adulthood (Cotter and Savage 2019; Cotter 2021; Perreault 2020).

Although different from harsh parenting, the GSS also included a question to measure situations where children’s basic needs (e.g., washing, feeding, clothing) were not met, which can also be detrimental to children who experience it.Note

The majority of people living in Canada, whether Indigenous or non-Indigenous, reported experiencing at least one type of harsh parenting or situations where their basic needs went unmet before the age of 15. However, this proportion was higher among Indigenous people (78%) than among non-Indigenous people (66%) (Chart 1). More precisely, 84% of Métis and 74% of First Nations persons reported experiencing harsh parenting or had their basic needs unmet before the age of 15, whereas a similar proportion of Inuit persons (67%E) and non-Indigenous persons reported having such experiences (Table 1).Note

Chart 1 start

Data table for Chart 1

| Type of harsh parenting or neglect | Indigenous persons | Non-Indigenous personsData table for Chart 1 Note ‡ | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| percent | 95% confidence interval | percent | 95% confidence interval | |||

| from | to | from | to | |||

| Total harsh parenting | 73.3Note * | 68.0 | 77.9 | 61.5 | 60.3 | 62.6 |

| Was spanked or slapped on the hand | 61.4Note * | 55.6 | 66.9 | 52.5 | 51.5 | 53.6 |

| Was told things that really hurt their feelings | 48.6Note * | 42.9 | 54.3 | 39.6 | 38.4 | 40.8 |

| Felt unwanted or unloved | 26.0Note * | 21.3 | 31.3 | 16.8 | 16.0 | 17.7 |

| Basic needs were not metData table for Chart 1 Note 1 | 12.3Note * | 9.0 | 16.6 | 2.8 | 2.5 | 3.2 |

Source: Statistics Canada, General Social Survey, 2019. |

||||||

Chart 1 end

However, larger differences between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people were noted for specific childhood experiences. For example, Indigenous people (17%) were twice as likely as non-Indigenous people (7.8%) to have felt unwanted or unloved as children on multiple occasions (i.e., more than five times). Indigenous people were also about five times more likely to report that their basic needs had not been met, on multiple occasions, during their childhood (7.6% versus 1.4%).

Of note, the GSS does not capture who was responsible for these behaviours or situations. As such, it may have been biological parents, but it could have been a step or foster parent or another guardian. Some of these experiences, such as unmet basic needs, may also be the result of economic marginalization. For instance, several studies showed that food insecurity was higher among Indigenous people than among non-Indigenous people (First Nations Food, Nutrition and Environment Study 2021; Polsky and Garriguet 2022; Statistics Canada 2018)

Just over one-third of Indigenous people witnessed violence by a parent against another person

Previous studies reported higher rates of spousal or intimate partner violence among Indigenous people than among non-Indigenous people, a type of violence that can be linked to the history of colonization, intergenerational trauma, marginalization and economic deprivation (Andersson and Nahwegahbown 2010; Brownridge et al. 2017; Heidinger 2021; Public Health Agency of Canada 2012). In some cases, children in the household may witness intimate partner violence or violence by one parent against another adult or another child in the household. Regardless of whether they were themselves victims of violence, witnessing a parent’s violence against others is associated with several negative impacts (Wolfe et al. 2003; Wood and Sommers 2011).

Overall, just over one-third (34%) of Indigenous people (32% of First Nations people, 36% of Métis and 37%E of Inuit) witnessed violence by one parent against another person during their childhood. In comparison, this was the case for one in five (20%) non-Indigenous people (Table 1).

Witnessing a parent’s violence against another child in the household was most commonly reported, with just under one-quarter (23%) of Indigenous people having witnessed it during their childhood. Just over one in six (17%) Indigenous people reported witnessing violence by a parent against another parent. Seeing a parent hit an adult other than a parent was less common, but 13% of Indigenous people had nonetheless experienced it.

Compared with non-Indigenous people, Indigenous people were more likely to have witnessed parental violence on multiple occasions (i.e., more than five times). For example, Indigenous people were nearly four times more likely than non-Indigenous people to have witnessed violence by a parent against another parent on multiple occasions (8.8% versus 2.4%) and seven times more likely to have seen a parent hit another adult more than five times (4.2% versus 0.6%).

Approximately 4 in 10 Indigenous people report experiencing sexual or physical violence as children

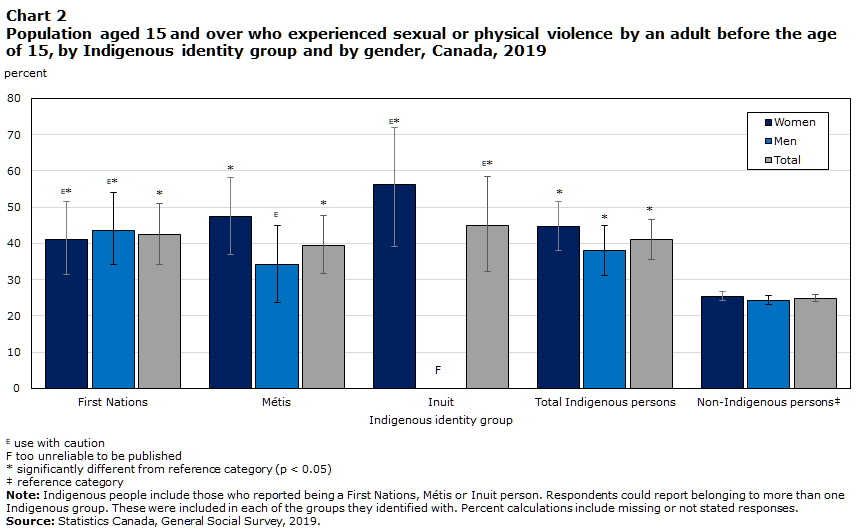

In 2019, Indigenous people were more likely than non-Indigenous people to report having experienced sexual or physical violence by an adult at least once before the age of 15. Approximately 4 out of 10 (41%) Indigenous people (42% of First Nations people, 39% of Métis and 45%E of Inuit) reported they had experienced such violence during childhood. Among non-Indigenous people, this proportion was 25% (Table 2, Table 3, Chart 2).

Chart 2 start

Data table for Chart 2

| Indigenous identity group | Women | Men | Total | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| percent | 95% confidence interval | percent | 95% confidence interval | percent | 95% confidence interval | ||||

| from | to | from | to | from | to | ||||

| First Nations | 41.1Note E: Use with caution Note * | 31.5 | 51.4 | 43.7Note E: Use with caution Note * | 29.7 | 58.6 | 42.3Note * | 34.1 | 50.9 |

| Métis | 47.3Note * | 36.8 | 58.1 | 34.3Note E: Use with caution | 23.8 | 46.6 | 39.4Note * | 31.7 | 47.7 |

| Inuit | 56.3Note E: Use with caution Note * | 39.2 | 72.0 | Note F: too unreliable to be published | Note F: too unreliable to be published | Note F: too unreliable to be published | 45.0Note E: Use with caution Note * | 32.3 | 58.4 |

| Total Indigenous persons | 44.7Note * | 38.0 | 51.6 | 37.9Note * | 29.3 | 47.5 | 41.0Note * | 35.6 | 46.6 |

| Non-Indigenous personsData table for Chart 2 Note ‡ | 25.4 | 24.2 | 26.7 | 24.2 | 22.9 | 25.6 | 24.8 | 23.9 | 25.8 |

|

E use with caution F too unreliable to be published

Source: Statistics Canada, General Social Survey, 2019. |

|||||||||

Chart 2 end

Among Canada’s various regions, Ontario has the highest proportion of Indigenous people who have experienced sexual or physical violence during childhood (54%E). In comparison, this proportion was 33% in the territories and 32% in the Prairies. In the Atlantic provinces (43%) and Quebec (37%E), the proportion of Indigenous people who experienced violence during childhood was closer to the national average (41%).Note

The overrepresentation of Indigenous people among victims of violence during childhood is declining with each new cohort

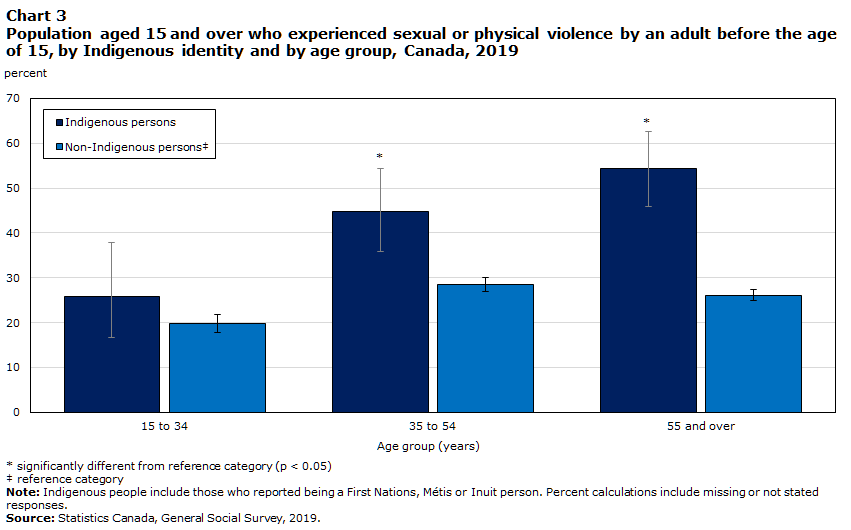

The 2014 GSS data revealed age differences, with younger Indigenous people less likely than older ones to have experienced sexual or physical violence by an adult during childhood (Burczycka 2017). The 2019 GSS data confirm what was noted in 2014—that Indigenous people aged 15 to 34 (26%) were significantly less likely than Indigenous people aged 35 to 54 (45%) or 55 and older (54%) to have experienced this form of violence during childhood (Chart 3).

Chart 3 start

Data table for Chart 3

| Age group (years) | Indigenous persons | Non-Indigenous personsData table for Chart 3 Note ‡ | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| percent | 95% confidence interval | percent | 95% confidence interval | |||

| from | to | from | to | |||

| 15 to 34 | 25.9 | 16.7 | 37.9 | 19.8 | 17.9 | 21.8 |

| 35 to 54 | 44.9Note * | 35.8 | 54.3 | 28.4 | 26.9 | 30.0 |

| 55 and over | 54.4Note * | 46.0 | 62.6 | 26.0 | 24.8 | 27.3 |

Source: Statistics Canada, General Social Survey, 2019. |

||||||

Chart 3 end

In fact, the proportion of Indigenous people aged 15 to 34 who experienced violence during childhood (26%) is relatively similar to the proportion of non-Indigenous people of the same age (20%), a difference that is not statistically significant. In contrast, Indigenous people aged 55 and older were nearly twice as likely as non-Indigenous people of the same age to have experienced violence during childhood (54% versus 26%).

Over one-quarter of Indigenous women experienced sexual violence during childhood

The GSS measures childhood violence using a set of five retrospective questions, two of which focus on sexual violence. More specifically, respondents are asked how many times an adult has sexually touched them and how many times they have been forced (including attempts) to engage in a sexual activity.

Overall, 16% of Indigenous people (14% of First Nations people, 17% of Métis and 27%E of Inuit) experienced sexual violence perpetrated by an adult at least once before the age of 15. Among non-Indigenous people, this proportion was 6.1% (Table 2, Table 3, Chart 4).

Both Indigenous and non-Indigenous womenNote were much more likely than men to have experienced sexual violence during childhood. More than one-quarter (26%) of Indigenous women experienced sexual violence during childhood, nearly three times the proportion of non-Indigenous women (9.2%). This proportion was also more than four times higher than that of Indigenous men (5.8%) (Chart 4). Due to the ongoing concern of the victimization of Indigenous women and girls, highlighted by the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls, a detailed analysis on childhood abuse experiences of Indigenous women is presented in a separate article (see Heidinger 2022).

Chart 4 start

Data table for Chart 4

| Indigenous identity group | Women | Men | Total | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| percent | 95% confidence interval | percent | 95% confidence interval | percent | 95% confidence interval | ||||

| from | to | from | to | from | to | ||||

| First Nations | 20.0Note * | 13.9 | 28.0 | 6.4Note E: Use with caution | 2.7 | 14.3 | 13.8Note * | 9.8 | 19.0 |

| Métis | 32.1Note * | 22.3 | 43.8 | 4.9Note E: Use with caution | 2.1 | 11.2 | 17.5Note * | 12.1 | 24.6 |

| Inuit | 38.0Note E: Use with caution Note * | 21.3 | 58.1 | Note F: too unreliable to be published | Note F: too unreliable to be published | Note F: too unreliable to be published | 27.2Note E: Use with caution Note * | 15.6 | 43.0 |

| Total Indigenous persons | 26.1Note * | 20.4 | 32.6 | 5.8 | 3.2 | 10.1 | 16.0Note * | 12.7 | 20.0 |

| Non-Indigenous personsData table for Chart 4 Note ‡ | 9.2 | 8.4 | 10.0 | 2.8 | 2.4 | 3.3 | 6.1 | 5.6 | 6.6 |

|

E use with caution F too unreliable to be published

Source: Statistics Canada, General Social Survey, 2019. |

|||||||||

Chart 4 end

Among the various forms of sexual violence, sexual touching was reported most often. Overall, nearly one in six Indigenous people (16%) were sexually touched by an adult during childhood, compared with 5.9% of non-Indigenous people. The difference is more pronounced when only those who have been sexually touched multiple occasions are considered; Indigenous people were about four times more likely than non-Indigenous people to have sexually touched more than five times (5.9% versus 1.4%, respectively).

Having been forced to engage in a sexual activity during childhood was reported less frequently but nonetheless experienced by 11% of Indigenous people, compared with 3.0% of non-Indigenous people. Indigenous people were about six times more likely than non-Indigenous people to have experienced this form of violence more than five times (4.5% versus 0.8%, respectively).

In more than half of cases, the sexual violence was perpetrated by a family member

The GSS asked individuals who experienced sexual violence by an adult during their childhood to share some information about the most serious incidentNote they experienced, including details about the person who committed it and the location of the assault.

The majority (56%) of Indigenous people who experienced sexual violence during childhood indicated that a family member was responsible for the most serious assault. More specifically, one-quarter (25%E) identified an immediate family member,Note and nearly one-third (31%E) identified an extended family memberNote as being responsible. In comparison, 44% of non-Indigenous people who experienced sexual violence during childhood reported being assaulted by a family member (23% by an immediate family member, 21% by an extended family member)Note (Table 4).

However, compared with Indigenous people, non-Indigenous people were more likely to have been sexually assaulted by a neighbour, friend or acquaintance (32% versus 21%E). Among both Indigenous (95%) and non-Indigenous (93%) people, a man was responsible for the most serious sexual assault in almost all cases.

Just over half (51%E) of Indigenous people who experienced sexual violence during childhood reported that the most serious incident occurred in the family home. Slightly more than one-third (35%E) reported that the incident occurred in another residence, usually that of the perpetrator, and nearly 1 in 10 Indigenous victims (8.8%E) reported that the most serious incident occurred at a school or residential school.Note Non-Indigenous people were also most likely to have been sexually assaulted in a private residence, but compared with Indigenous people, they were more likely to have been assaulted in a public place (15% versus 3.6%E).

More than one-third of Indigenous people experienced physical violence during childhood

Physical violence in childhood includes being slapped, beaten, pushed, grabbed, shoved, bitten, burned, kicked, punched or strangled; having an object thrown at them; or being otherwise physically assaulted. More than one-third (36%) of Indigenous people (38% of First Nations people, 36% of Métis and 34%E of Inuit) reported having experienced physical violence by an adult during childhood (Table 2, Table 3).

Overall, Indigenous people (36%) were more likely than non-Indigenous people (22%) to have experienced physical violence by an adult at least once during their childhood. However, the differences between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people are more pronounced when considering those who experienced violence on several occasions.

Compared with non-Indigenous people, Indigenous people were twice as likely to have been slapped or beaten more than five times (13% versus 6.5%), three times more likely to have been shoved, grabbed, pushed or to have had an object thrown at them on several occasions (11% versus 3.3%) and over four times more likely to have been bitten, burned, kicked, punched, assaulted or otherwise physically attacked on more than five occasions (6.9% versus 1.6%).

In most cases, a man was responsible for the most serious physical assault, both among Indigenous people (65%) and non-Indigenous people (58%). However, these proportions are lower than those for sexual assaults perpetrated by a man (95% and 93%, respectively).

In the large majority of cases, Indigenous people who experienced physical violence during childhood reported that the most serious incident was committed by an immediate family member (73%) and that it occurred in the family home (76%).

Few victims of childhood violence have talked about the violence to authorities, but Indigenous victims were more likely to have done so

Experiences of sexual or physical violence during childhood have rarely come to the attention of police or child protection services. About one in six (16%) Indigenous people who experienced sexual or physical violence by an adult during childhood reported that they had talked about it to the authorities, whether it was to the police (12%) or child protection services (10%), before the age of 15. Of note, GSS data does not ask how the violence came to the attention of authorities, which may have been reported by someone other than the victim.

Compared to Indigenous people, non-Indigenous people (5.2%) were less likely to have talked to the authorities about the violence they experienced while under the age of 15: 3.7 % of victims spoke to the police and 2.8% spoke to child protection services (Chart 5). In comparison, approximately one-quarter (24%) of violent crimes committed against all victims aged 15 and older, Indigenous and non-Indigenous, were reported to the police in 2019 (Cotter 2021).

Chart 5 start

Data table for Chart 5

| Person to whom the victim talked about the incidents before age 15 | Indigenous persons | Non-Indigenous personsData table for Chart 5 Note ‡ | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| percent | 95% confidence interval | percent | 95% confidence interval | |||

| from | to | from | to | |||

| Police or child protection services | 16.2Note * | 10.4 | 24.4 | 5.2 | 4.4 | 6.3 |

| Police | 12.0Note * | 7.4 | 19.0 | 3.7 | 3.0 | 4.5 |

| Child protection services | 10.1Note * | 5.5 | 18.0 | 2.8 | 2.2 | 3.7 |

| Family member | 35.3 | 27.2 | 44.4 | 28.3 | 26.5 | 30.3 |

| Friend | 18.3 | 12.4 | 26.1 | 15.4 | 13.8 | 17.2 |

| Health professional | 7.7 | 3.3 | 16.7 | 2.7 | 2.1 | 3.5 |

| Teacher | 5.2 | 2.0 | 13.1 | 2.0 | 1.5 | 2.7 |

| Other | 11.4Note * | 5.9 | 20.9 | 3.4 | 2.7 | 4.2 |

Source: Statistics Canada, General Social Survey, 2019. |

||||||

Chart 5 end

Some victims of childhood violence were also able to talk about the events to others, such as a family member or a friend. Overall, slightly less than half (46%) of Indigenous people who had experienced violence during childhood talked to someone other than the authorities about these violent events before the age of 15. Most of the time, they were family members (35%), friends (18%), health care workersNote (7.7%) or teachers (5.2%).

More than one-third of individuals who experienced sexual or physical violence while under the legal responsibility of the government are Indigenous

Indigenous people 15 years of age and older were about 9 times more likely than non-Indigenous people to have been under the government’s responsibility during their childhood (11% versus 1.3%). Specifically, 15% of First Nations people, 7.3% of Métis and 19%E of Inuit reported that they had previously been under the government’s responsibility (Table 2).

For many children, particularly Indigenous children, these placements under the responsibility of the government were accompanied by sexual or physical violence. Overall, more than one-third (34%) of people aged 15 and older who experienced violence while they were under the government’s responsibility are Indigenous.

Start of text box 1

Text box 1

Overrepresentation

of Indigenous people in child

protection services

Several studies and reports indicate that Indigenous people are overrepresented in child protection services (Assembly of First Nations 2006; Ma et al. 2019; National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation 2015; Sinha et al. 2011).

The higher proportion of Indigenous people who have been under the legal responsibility of the government during their childhood could be partly due to a higher severity and reporting of childhood violence among the Indigenous population. Indigenous people were more likely than non-Indigenous people to have experienced certain behaviours by an adult multiple times (i.e., more than five times) before the age of 15 (Table 1, Table 2). Respondents, whether Indigenous or non-Indigenous, who reported having been repeatedly subjected to certain behaviours were also more likely to have talked the authorities about it.

For example, non-Indigenous people who reported having been forced to engage in sexual activity more than five times, sexually touched more than five times, beaten more than five times, or pushed or grabbed more than five times were about as likely as Indigenous people who had the same experiences (15% and 21%,Note respectively) to have told authorities about it. As such, it is possible that the relatively high proportion of Indigenous people who have been under the legal responsibility of the government is, in part, attributable to the heightened frequency and severity of sexual and physical violence experienced as well as such violence being more commonly reported to authorities.

However, even among those who reported having experienced less serious or less frequent violence, it was more likely to have been reported to the authorities when it involved Indigenous people. For example, among those who were slapped or hit five times or less by an adult before the age of 15, Indigenous people were about four times more likely than non-Indigenous people to have talked to authorities (13%E versus 2.9%).

A multivariate analysis was conducted to analyze the factors involved in a greater likelihood of having been under the legal responsibility of the government. The analysis took into account the severity and frequency of the past acts of violence or neglect, as well as the relationship between the child and the person who committed the most serious assault, the location of the most serious assault and Indigenous identity of victim. However, several known correlates were not part of the General Social Survey and could not be included in the multivariate analysis, for example, the resources of parents (e.g., social network, financial resources), the mental health or substance use of parents, or the household situation (e.g., overcrowding in dwellings).

Nevertheless, the results show that the greater proportion of Indigenous people who have been under the government’s responsibility during their childhood is, at least partly, attributable to factors other than the severity or frequency of violence or neglect. Of all the factors considered, being Indigenous remained most closely related to the likelihood of having been under the legal responsibility of the government (odds ratio = 6.85)Note (Text box 1 table).

Many have criticized child protection systems as a continuation of the residential school system and for perpetuating experiences of marginalization, oppression and colonialism (Blackstock 2007; Choate et al. 2021; National Collaborating Centre for Indigenous Health 2017a). For its part, the report of the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls emphasized that the way in which child protection services investigate child apprehensions or substantiate their merits can be deemed racist and insufficient (National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls 2019).

In this context, former Bill C-92, An Act respecting First Nations, Inuit and Métis children, youth and families, received Royal Assent in June 2019. The purpose of the act is to enable Indigenous communities and groups to develop child protection policies and legislation based on their own histories, cultures and situations, to protect the relationship between children and their families, communities and cultures (Indigenous Services Canada 2019).

End of text box 1

Victimization experiences of people aged 15 and over in the 12 months preceding the survey

In addition to experiences of sexual or physical violence experienced by Indigenous people as children, the issue of overrepresentation of Indigenous people among victims of violent crime has also often been a focal point in recent news. The final report of the National Inquiry into MMIWG highlighted the high homicide rates and disappearances of Indigenous women and girls. Further, the report emphasized the context of such violence, often marked by intergenerational trauma; marginalization in the form of poverty, precarious housing or homelessness; and barriers to education, employment, health care and cultural support (National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls 2019). The most recent data continue to show higher homicide rates and violent victimization rates among Indigenous people than non-Indigenous people (Armstrong and Jaffray 2021; Cotter 2021).

Using data from the 2019 GSS, the next section presents an analysis of the nature and extent of more recent victimization (i.e., in the 12 months preceding the survey) among First Nations people, Métis and Inuit. In addition, it discusses the context and key factors associated with this violence.

Indigenous people are twice as likely as non-Indigenous people to have been victims of violent crime

Nearly 80,000 Indigenous people were victims of at least one sexual assault, robbery or assault in the 12 months preceding the 2019 GSS. This represents 8.4% of Indigenous people, twice the proportion of non-Indigenous people (4.2%) (Table 3, Table 5). Specifically, 4.1% of Indigenous people reported having been victims of one violent crime, while 4.3% reported having been victims of at least two violent crimes.Note In comparison, 2.2% of non-Indigenous people were victims of one violent crime, and 1.9% were victims of at least two violent crimes.Note

Overall, Indigenous people were the victims of just over 165,000 violent crimes, representing 6.4% of all violent crimes. This corresponds to a rate of 177 violent crimes per 1,000 Indigenous people, compared with a rate of 80 violent crimes per 1,000 non-Indigenous people.

Among the various crimes, physical assaults were the most frequent, accounting for more than two-thirds (68%) of violent crimes reported by Indigenous people. About one in five (20%) violent crimes were sexual assaults, while 12% were robberies.

Indigenous people living in rural areas are about as likely as non-Indigenous people to have been victims of violent crime

While, overall, Indigenous people were more likely than non-Indigenous people to report having been victims of a violent crime in 2019, this may not be the case in rural areas (that is, areas outside of census metropolitan areas or census agglomerationsNote ). In rural areas, 6.4% of Indigenous peopleNote reported having been the victims of a violent crime, a proportion not statistically different from that reported by non-Indigenous people in rural areas (3.9%). In contrast, Indigenous people living in urban areas were about twice as likely as their non-Indigenous counterparts to have been victims of a violent crime in 2019 (9.7%Note versus 4.2%) (Table 5, Table 6).

Previous studies based on police-reported data have found relatively high crime rates in the northern parts of the country—that is, in the provincial North and the territories (Allen and Perreault 2015; Perreault 2019), which are mostly rural. According to self-reported data from the 2019 GSS, 11% of Indigenous people living in northern areas were victims of a violent crime in 2019. However, the difference between that proportion and the proportion of victims among non-Indigenous people living in northern areas (6.2%) or among Indigenous people living in southern areas (7.6%) was not found to be statistically significant.

Start of text box 2

Text box 2

Indigenous

people living in the Atlantic provinces are less likely to have been victims of

a crime against the person than Indigenous people in other regions

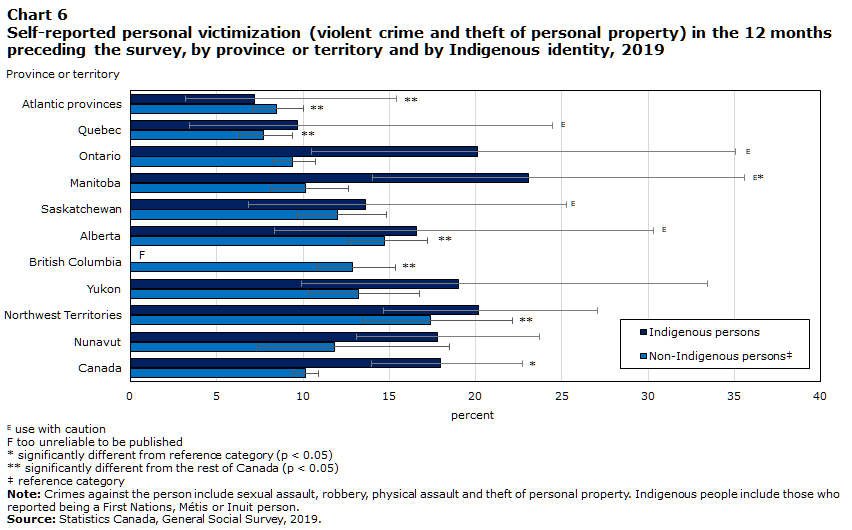

In addition to providing information on experiences of violent victimization, the General Social Survey collects data on thefts of personal property that occurred in the 12 months preceding the survey. Together, this information represents crimes against the person. The analysis of all crimes against the person helps identify certain differences between the provinces or territories, which would not be possible if the analysis focused on violent crimes only because of sample size.Note

Of the Indigenous population residing in all provinces and territories, Indigenous people living in the Atlantic provincesNote were least likely to have been victims of a crime against the person in 2019. In the Atlantic provinces taken as a whole, 7.2% of Indigenous people were victims of violent a violent crime or theft of personal property. In comparison, this proportion was 18% nationwide. In addition, the proportion of Indigenous people who were victims of a crime against the person in the Atlantic provinces was similar to the proportion of their non-Indigenous counterparts (8.5%) (Chart 6).

Chart 6 start

Data table for Chart 6

| Province or territory | Indigenous persons | Non-Indigenous personsData table for Chart 6 Note ‡ | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| percent | 95% confidence interval | percent | 95% confidence interval | |||

| from | to | from | to | |||

| Atlantic provinces | 7.2Note ** | 3.2 | 15.4 | 8.5Note ** | 7.1 | 10.0 |

| Quebec | 9.7Note E: Use with caution | 3.4 | 24.5 | 7.7Note ** | 6.3 | 9.4 |

| Ontario | 20.1Note E: Use with caution | 10.5 | 35.1 | 9.4 | 8.2 | 10.7 |

| Manitoba | 23.1Note E: Use with caution Note * | 14.0 | 35.6 | 10.2 | 8.1 | 12.6 |

| Saskatchewan | 13.6Note E: Use with caution | 6.9 | 25.3 | 12.0 | 9.6 | 14.9 |

| Alberta | 16.6Note E: Use with caution | 8.3 | 30.3 | 14.7Note ** | 12.6 | 17.2 |

| British Columbia | Note F: too unreliable to be published | 13.7 | 43.7 | 12.9Note ** | 10.8 | 15.4 |

| Yukon | 19.0 | 9.9 | 33.4 | 13.2 | 10.3 | 16.7 |

| Northwest Territories | 20.2 | 14.7 | 27.1 | 17.4Note ** | 13.5 | 22.1 |

| Nunavut | 17.8 | 13.1 | 23.7 | 11.8 | 7.4 | 18.5 |

| Canada | 17.9Note * | 14.0 | 22.7 | 10.1 | 9.4 | 10.9 |

|

E use with caution F too unreliable to be published

Source: Statistics Canada, General Social Survey, 2019. |

||||||

Chart 6 end

Manitoba was the province with the greatest difference in victimization between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people. Nearly one-quarter (23%E) of Indigenous people in that province reported they were victims of at least one violent crime or theft of personal property in the 12 months preceding the survey, compared with 10% of non-Indigenous people. This difference was mainly because of high victimization rates in urban areas. In rural areas, 5.4% of Indigenous people and 5.0% of non-Indigenous people reported being victims of a crime against the person.

End of text box 2

More than 1 in 10 Métis and Inuit were victims of a violent crime in 2019

The higher victimization rates among Indigenous people are primarily attributable to the high rates reported by Métis and Inuit. More specifically, 12% of Métis (225 violent crimes per 1,000 Métis) and 11%E of Inuit (265E violent crimes per 1,000 Inuit) reported experiencing at least one violent crime in 2019. Among First Nations people, 5.5% were victims of at least one violent crime (127 violent crimes per 1,000 First Nations people), a proportion relatively similar to that of non-Indigenous people (4.2%)Note (Table 3, Chart 7).

Chart 7 start

Data table for Chart 7

| Indigenous identity group | rate per 1,000 population | 95% confidence interval | |

|---|---|---|---|

| from | to | ||

| First Nations | 127 | 33 | 220 |

| Métis | 225Note * | 84 | 367 |

| Inuit | 265Note * | 114 | 415 |

| Total Indigenous persons | 177Note * | 97 | 258 |

| Non-Indigenous personsData table for Chart 7 Note ‡ | 80 | 68 | 92 |

Source: Statistics Canada, General Social Survey, 2019. |

|||

Chart 7 end

The higher prevalence of victimization among Métis and Inuit was observed primarily for physical assaults. The proportions of individuals who were sexually assaulted or robbed at least once were relatively similar in each Indigenous group and when compared to non-Indigenous people.Note In contrast, 10%E of Inuit and 8.5% of Métis were victims of at least one physical assault incident, compared with 4.5% of First Nations people and 2.6% of non-Indigenous people (Table 3).Note

Nearly 1 in 10 Indigenous women were victims of a violent crime in 2019

While the victimization of Indigenous women is a long-standing problem (see Miladinovic and Mulligan 2015 or Brzozowski et al. 2006), as a social issue, it has received more attention in recent years. In particular, the numerous cases of missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls led to the establishment of a national inquiry in 2016 (National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls 2019). Victimization among Indigenous women is discussed in depth in the article “Violent victimization and perceptions of safety: Experiences of First Nations, Métis and Inuit women in Canada” (Heidinger 2022).

According to 2019 GSS data, nearly 1 in 10 (9.3%) Indigenous women (5.9% of First Nations women, 15% of Métis women and 9.7%E of Inuit women) were victims of a violent crime in the 12 months preceding the survey (Table 5, Table 6). More specifically, 2.8% of Indigenous women were sexually assaulted, 1.8% were robbed and 6.3% were physically assaulted. Among non-Indigenous people, approximately 1 in 20 (4.9%) women were victims of a violent crime.Note

Among Indigenous men, 7.7% (5.1%E of First Nations people and 9.6%E of Métis men)Note were victims of a violent crime in the 12 months preceding the survey—twice the proportion of non-Indigenous men (3.4%).

Indigenous people aged 35 to 54 are most likely to have been victims of a violent crime

Most studies on victimization show that there is a strong link between age and risk of victimization (Cotter 2021; Perreault 2015; Siddique 2016). In general, victimization rates peak among those aged 15 to 24, then tend to decline gradually as age increases. A similar relationship has also been noted between age and the commission of crime, both in Canada and in most countries (Loeber et al. 2015; Ulmer and Steffensmeier 2014).

Among respondents aged 15 to 34 years, Indigenous and non-Indigenous people were the victims of a relatively similar level of violent crime in 2019. The highest rates were rather found among Indigenous people aged 35 to 54. As such, about one in eight (12%) Indigenous people (8.4%E of First Nations people and 19%E of Métis)Note aged 35 to 54 years were victims of at least one violent crime in the 12 months preceding the survey. This proportion is approximately four times higher than that of non-Indigenous people of the same age (3.9%) or Indigenous people aged 55 and older (3.4%) (Table 5, Table 6, Chart 8).

Chart 8 start

Data table for Chart 8

| Indigenous identity and gender | 15 to 34 years | 35 to 54 years | 55 years and over | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| percent | 95% confidence interval | percent | 95% confidence interval | percent | 95% confidence interval | ||||

| from | to | from | to | from | to | ||||

| Indigenous persons | |||||||||

| Women | 8.4Note E: Use with caution | 3.5 | 18.6 | 14.0Note E: Use with caution | 6.8 | 26.9 | 3.7Note E: Use with caution | 1.6 | 8.4 |

| Men | Note F: too unreliable to be published | Note F: too unreliable to be published | Note F: too unreliable to be published | 9.7Note E: Use with caution | 3.8 | 22.9 | 3.2Note E: Use with caution | 0.9 | 10.2 |

| Total | 8.8 | 4.9 | 15.3 | 12.4Note * | 6.8 | 21.5 | 3.4 | 1.7 | 6.8 |

| Non-Indigenous personsData table for Chart 8 Note ‡ | |||||||||

| Women | 9.3 | 7.5 | 11.6 | 4.4 | 3.4 | 5.8 | 1.8 | 1.4 | 2.3 |

| Men | 5.2 | 3.8 | 7.0 | 3.3 | 2.6 | 4.2 | 1.8 | 1.2 | 2.7 |

| Total | 7.3 | 6.1 | 8.7 | 3.9 | 3.2 | 4.7 | 1.8 | 1.5 | 2.3 |

|

E use with caution F too unreliable to be published

Source: Statistics Canada, General Social Survey, 2019. |

|||||||||

Chart 8 end

The higher rates of violent victimization among Indigenous people aged 35 to 54 may be related, in part, to the higher proportions of those who experienced violence during childhood in this age group compared with Indigenous people younger than 35. Having experienced violence during childhood is associated with mental health problems, substance use, marginalization and discrimination, which in turn can increase the risk of victimization (Boyce et al. 2015; Burczycka 2017; Cotter 2021; Perreault 2015).

Start of text box 3

Text box 3

Self-reported

spousal violence and intimate partner violence

Similar to violent victimization in general, several studies have noted higher rates of spousal violence or intimate partner violence among Indigenous people compared with non-Indigenous people (Boyce 2016, Burczycka 2016; Heidinger 2021). The ongoing legacy of colonization and cultural suppression may have led to the normalization of violence, especially against women (Andersson and Nahwegahbon 2010; Heidinger 2021; National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls 2019).

In 2019, 7.5% of Indigenous people (7.3% of First Nations people, 9.4% of Métis and 15%E of Inuit) who were married or in common-law relationships or had (or had contact with) a partner in the previous five years, experienced spousal violence in the five years preceding the survey. Among non-Indigenous people, the proportion was 3.4%. That said, there has been a significant decrease in spousal violence against Indigenous women. Specifically, the proportion of spousal violence victims among Indigenous women decreased by about 50% since 2009, from 15%E in 2009 to 7.5% in 2019 (Chart 9).

Chart 9 start

Data table for Chart 9

| Indigenous identity and gender | 2009 | 2014 | 2019Data table for Chart 9 Note ‡ | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| percent | 95% confidence interval | percent | 95% confidence interval | percent | 95% confidence interval | ||||

| from | to | from | to | from | to | ||||

| Indigenous persons | |||||||||

| Women | 15.4Note E: Use with caution Note *** | 10.8 | 21.4 | 9.7Note E: Use with caution Note ** | 6.3 | 14.5 | 7.5 | 4.0 | 13.6 |

| Men | Note F: too unreliable to be published | Note F: too unreliable to be published | Note F: too unreliable to be published | 8.0Note E: Use with caution Note ** | 4.7 | 13.4 | 6.2 | 2.8 | 13.5 |

| Total | 9.5Note ** | 6.9 | 13.1 | 8.8Note ** | 6.4 | 12.1 | 6.9Note ** | 4.3 | 10.9 |

| Non-Indigenous personsData table for Chart 9 Note ‡ | |||||||||

| Women | 6.0Note * | 5.4 | 6.7 | 3.3 | 3.0 | 3.8 | 4.1 | 3.4 | 5.0 |

| Men | 6.1Note * | 5.4 | 6.9 | 4.1Note * | 3.6 | 4.7 | 2.6 | 2.1 | 3.2 |

| Total | 6.1Note * | 5.6 | 6.6 | 3.7 | 3.4 | 4.1 | 3.4 | 2.9 | 3.9 |

|

E use with caution F too unreliable to be published

Source: Statistics Canada, General Social Survey, 2019. |

|||||||||

Chart 9 end

In 2019, questions were added to the General Social Survey to better measure the nature and extent of violence committed by current or former intimate partners other than married or common-law partners. Overall, 11% of Indigenous people (8.9% of First Nations people, 13% of Métis and 17%E of Inuit) reported having experienced violence from an intimate partner in the five years preceding the survey, more than double the proportion of non-Indigenous people (4.7%)Note (Chart 10).

More specifically, 11% of Indigenous people reported having been threatened with being hit; had an object thrown at them; been pushed, grabbed or slapped by an intimate partner. Meanwhile, 18% reported having been bitten, punched or kicked; hit with an object; beaten or choked; threatened with a weapon; and forced or manipulated into engaging in non-consensual sexual activity. In comparison, these proportions were 5.1% and 3.1% for non-Indigenous people, respectively.

Chart 10 start

Data table for Chart 10

| Indigenous identity group | Women | Men | Total | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| percent | 95% confidence interval | percent | 95% confidence interval | percent | 95% confidence interval | ||||

| from | to | from | to | from | to | ||||

| First Nations | 15.7Note E: Use with cautionNote * | 8.8 | 26.3 | 6.4Note E: Use with caution | 2.5 | 15.7 | 11.7Note * | 7.2 | 18.4 |

| Métis | 12.9Note E: Use with caution | 7.1 | 22.6 | 17.6Note E: Use with cautionNote * | 8.2 | 33.9 | 15.5Note * | 9.2 | 24.9 |

| Inuit | Note F: too unreliable to be published | Note F: too unreliable to be published | Note F: too unreliable to be published | Note F: too unreliable to be published | Note F: too unreliable to be published | Note F: too unreliable to be published | 22.0Note E: Use with cautionNote * | 11.6 | 37.5 |

| Total Indigenous persons | 13.5Note * | 9.0 | 19.7 | 12.9Note * | 7.0 | 22.7 | 13.3Note * | 9.3 | 18.5 |

| Non-Indigenous personsData table for Chart 10 Note ‡ | 6.5 | 5.7 | 7.5 | 4.9 | 4.1 | 5.9 | 5.7 | 5.1 | 6.4 |

|

E use with caution F too unreliable to be published

Source: Statistics Canada, General Social Survey, 2019. |

|||||||||

Chart 10 end

In addition to physical or sexual violence, violence between intimate partners can sometimes take the form of psychological or financial abuse. Just over one in four (27%) Indigenous people (21% of First Nations people, 30% of Métis and 47%E of Inuit) experienced psychological or financial abuse from an intimate partner,Note compared with 16% of non-Indigenous people.

For more information on intimate partner violence and spousal violence, see the Juristat articles “Spousal violence in Canada, 2019” (Conroy 2021) and “Intimate partner violence: Experiences of First Nations, Métis and Inuit women” (Heidinger 2021).

End of text box 3

Individuals who report drug use have higher victimization rates

Indigenous people were more likely than non-Indigenous people to report having used cannabis or illicit drugs in the 12 months preceding the survey. One-quarter (25%) of Indigenous people (19% of First Nations people, 30% of Métis and 46%E of Inuit) reported having used cannabis or illicit drugs, compared with 15% of non-Indigenous people. Various studies have noted an increased risk of victimization among people using cannabis or illicit drugs (Boyce 2016; Cotter and Savage 2019; Cotter 2021; Perreault 2015; Perreault 2020). The same association was noted with 2019 GSS data, where Indigenous people who used drugs were about three times more likely than those who did not use drugs to have been victims of at least one violent crime (17% versus 5.4%) (Table 7).

Among both Indigenous and non-Indigenous people, drug users were more likely than non-drug users to be aged 15 to 34 (49% versus 28%), to be single (41% versus 26%), to go out during the evening 20 or more times per month (31% versus 21%), to report binge drinkingNote at least once per month (52% versus 18%) and to have a partner who uses drugs or engages in binge drinking at least once per month (66% versus 19%).Note These factors are also associated with higher victimization rates. Thus, people who use drugs may be more exposed to violence.

Drug use is also associated with other difficult life experiences or experiences of marginalization. For example, drug use was more common among Indigenous people who had experienced childhood violence (33%) or harsh parenting (29%) than those who had not experienced such violence (21%) or harsh parenting (16%). Similarly, drug use was higher among people who had previously been homeless, who had a physical or mental disability, or who had been discriminated against in the last five years. However, these life experiences are also linked to an increased risk of victimization.

Finally, some victims may use drugs to deal with the negative impact of victimization. According to data from the 2018 SSPPS, 10% of people who use drugs and who had been victims of physical or sexual assault in their lifetimeNote reported using substances to cope with the negative impacts of victimization.

A history of violence or harsh or negligent parenting during childhood is closely linked to the risk of victimization in adulthood

Among both Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations, experiencing violence or harsh parenting practices during childhood is one of the main factors associated with the risk of victimization in adulthood (Burczycka 2017; Cotter 2021; Perreault 2015; Perreault 2020). As noted in the first section of this article, Indigenous people, particularly those aged 35 and older, were more likely than non-Indigenous people to have experienced violence during their childhood.

Thus, higher rates of violent victimization among Indigenous people may be tied with the greater proportion having experienced violence or harsh parenting practices. For example, 1.1% of Indigenous peopleNote who never experienced harsh or neglectful parentingNote were victims of a violent crime in the 12 months preceding the survey, a proportion similar to that reported by their non-Indigenous counterparts (1.7%). However, this proportion was approximately 10 times higher among Indigenous people who had experienced harsh parenting (11%, 7.5% of First Nations people and 15% of Métis), and approximately twice as high as non-Indigenous people who had also experienced such behaviours (5.7%) (Table 7).

Similarly, while 3.7% of Indigenous people who had not experienced childhood violence reported being the victims of a violent crime in 2019, this proportion was 14% (11%E of First Nations people and 22%E of Métis)Note among those who experienced physical violence and 27%E among those who experienced sexual violence. Among non-Indigenous people, these proportions were 2.9%, 7.6% and 10%, respectively.

Start of text box 4

Text box 4

Multivariate

analysis: Indigenous identity is not a factor associated with the risk of

violent victimization, but sexual violence in childhood is a significant factor

There is a close correlation between several factors that are associated with higher rates of violent victimization. For example, being young is generally associated with higher rates of violent victimization, but being young is also associated with being single, going out during the evening more often and using more alcohol or drugs. All these factors are also associated with higher victimization rates in general. A multivariate analysis (logistic regression) analyzes these factors independently, keeping the other factors constant, and determines which ones are the most decisive.

In this article, a first round of multivariate analyses was conducted across the population to determine whether Indigenous persons remained at greater risk of victimization when other factors remained constant.

When taking into account some key socioeconomic factors (i.e., age, gender, marital status, education, and sexual orientation) Indigenous people continued to be at slightly higher risk of violent victimization compared to non-Indigenous people (Model 1). However, when additional factors related to social cohesion (trust in neighbours, discrimination), health (poor mental health), lifestyle (drug use, frequency of evenings out) and, most important, certain circumstances (childhood abuse, homelessness) were also considered, Indigenous persons did not have a higher risk of violent victimization (Model 2) (Table 8). Said otherwise, higher victimization rates among Indigenous people can be attributed to factors such as socioeconomic and health conditions, as well as history of homelessness and childhood maltreatment.

Factors associated with an increased risk of victimization may however be slightly different among Indigenous people compared with the general population. Thus, another regression model was applied only to the Indigenous population. Age was also a risk factor among Indigenous people, but as noted earlier, the risk of victimization only drops significantly around the age of 55. As was the case with the general population model, a history of childhood sexual violence and harsh parenting were among the factors most closely associated with an increased risk of victimization among the Indigenous people. Finally, even when the various risk factors are considered, Indigenous people living in the territories or the Prairie provinces were more likely to have been victims of violent crime than Indigenous people living in the other provinces (Model 3) (Table 9).

End of text box 4

The rate of violent victimization is four times higher among Indigenous people who have experienced discrimination than among those who have not

In Canada, people belonging to certain population groups are more likely than others to be discriminated against (i.e., experience unfair treatment because of ethnicity or culture, gender, sexual orientation, or physical or mental disability) (Gorelik 2022; Ibrahim 2020; Gravel 2015; Statistics Canada 2020).

One-third (33%) of Indigenous people (44% of First Nations people, 24% of Métis and 29%E of Inuit) reported having experienced discrimination in the five years preceding the survey. The most common experiences of discrimination faced by Indigenous people occurred in a store, restaurant or bank (14%) and in the workplace (13%).

Compared with interactions with the staff of stores, restaurants and banks or interactions with co-workers, interactions with the police are generally infrequent. Thus, few people reported being discriminated against in their dealings with the police (1.2%). However, Indigenous people were overrepresented among victims of police discrimination. While they accounted for about 5% of those who had been discriminated against in general, Indigenous people accounted for 17% of those who had experienced discrimination in their dealings with the police. Systemic racism in policing in Canada is a growing concern and likely a contributing factor to Indigenous people’s overrepresentation in the criminal justice system (David and Mitchell 2021)

Several of the population groups most likely to face discrimination also record relatively high rates of violent victimization. This is true of Indigenous people, but also of women, people with physical or mental disabilities, and bisexual individuals (Cotter 2021). But even within each of these population groups, those who personally experienced discrimination were the most likely to have been victims of a violent crime. For example, 15% of Indigenous people who experienced discrimination were also victims of violent crime in 2019, a rate of 354 violent crimes per 1,000 people. This rate is four times higher than that of Indigenous people who did not experience discrimination (86 crimes per 1,000 people) (Table 5, Table 6).

Violence may be partly rooted in the same social structures as discrimination. Thus, the most marginalized Indigenous people may also be the most vulnerable to discrimination and violence. According to the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls, discrimination is one of the factors behind high rates of violence against Indigenous women (National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls 2019).

Start of text box 5

Text box 5

Victimization

of LGBTQ2+ Indigenous people

Previous studies have shown that LGBTQ2+ peopleNote were more likely to experience sexual or physical assaults, as well as other types of unwanted behaviours compared to non-LGBTQ2+ people (Jaffray 2020; Perreault 2020). The same studies have highlighted an increased risk of victimization among LGBTQ2+ individuals who also identify with another marginalized population group, such as people with a disability and Indigenous people.

The sample size of the 2019 General Social Survey on Canadian’s Safety (victimization) does not allow reliable estimates for LGBTQ2+ Indigenous people. However, data from the 2018 Survey on Safety in Public and Private Spaces do show that, compared to non-LGBTQ2+ non-Indigenous people, LGBTQ2+ Indigenous people were more likely to have experienced sexual or physical assault as well as intimate partner violence (IPV). More specifically, LGBTQ2+ Indigenous people were about twice as likely to have been sexually or physically assaulted by an adult when they were under age 15 (58% versus 26%), to have been sexually or physically assaulted since age 15 (82% versus 41%), and to have experienced IPV since age 15 (81% versus 40%) (Text box 5 chart).

Text box 5 chart 1 start

Data table for Text box 5 chart 1

| Experiences of victimization | Indigenous LGBTQ2+ persons | Indigenous non-LGBTQ2+ persons | Non-Indigenous LGBTQ2+ persons | Non-Indigenous non-LGBTQ2+ personsData table for textbox 5 Chart 1 Note ‡ | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| percent | 95% confidence interval | percent | 95% confidence interval | percent | 95% confidence interval | percent | 95% confidence interval | |||||

| from | to | from | to | from | to | from | to | |||||

| Assault before age 15Data table for textbox 5 Chart 1 Note 1 | 58.0 | 43.2 | 71.4 | 37.0 | 33.4 | 40.7 | 41.5 | 37.2 | 45.9 | 26.3 | 25.6 | 27.0 |

| Assault since age 15Data table for textbox 5 Chart 1 Note 2 | 82.3 | 70.1 | 90.2 | 60.9 | 57.3 | 64.5 | 62.4 | 57.8 | 66.8 | 41.4 | 40.6 | 42.2 |

| IPV since age 15Data table for textbox 5 Chart 1 Note 3 | 80.8 | 67.3 | 89.6 | 56.2 | 52.4 | 60.0 | 60.1 | 55.1 | 65.0 | 39.5 | 38.7 | 40.3 |

| Assault in the preceding 12 monthsData table for textbox 5 Chart 1 Note 2 | 28.3 | 16.4 | 44.2 | 10.6 | 7.8 | 14.1 | 13.6 | 11.0 | 16.6 | 5.9 | 5.4 | 6.3 |

| IPV in the preceding 12 monthsData table for textbox 5 Chart 1 Note 3 | 36.7 | 19.8 | 57.7 | 17.3 | 13.8 | 21.6 | 23.7 | 19.1 | 28.9 | 12.6 | 11.9 | 13.3 |

Source: Statistics Canada, Survey on Safety in Public and Private Spaces, 2018. |

||||||||||||

Text box 5 chart 1 end

The picture was similar for more recent victimization, but the differences were even wider. Compared to non-LGBTQ2+ non-Indigenous people, LGBTQ2+ Indigenous people were about three times more likely to have experienced IPV in the 12 months preceding the survey (37% compared to 13% of non-Indigenous non-LGBTQ2+ people), and almost five times more likely to have experienced sexual or physical assault in the 12 months preceding the survey (28% compared to 5.9%).

End of text box 5

Characteristics of violent victimization incidents

In the 2019 GSS, respondents who were victims of criminal acts were asked to provide some information about each of these crimes. However, the sample size prevents analyzing the characteristics of crimes involving Indigenous victims.

As a complement to the GSS, the 2018 SSPPS is another source of data on criminal victimization. Compared with the GSS, the larger sample size may allow for the analysis of some additional information on crimes involving Indigenous victims.Note However, while the GSS collects information on each of the criminal victimization incidents survey respondents experienced, the SSPPS data is limited to the physical and sexual assault that the victim considered to be the most serious in the 12 months preceding the survey.

The following section presents some of the key findings from the SSPPS data on the main characteristics of the most serious sexual or physical assault experienced by Canadians in the 12 months preceding the survey.Note For almost half (46%) of non-Indigenous people and one-third (33%) of Indigenous people, the most serious assault was a sexual assault.Note The characteristics of the crimes exclude assaults by an intimate partner, which were collected through a separate set of questions.

More than one-third of Indigenous victims were injured during the most serious assault they experienced

The SSPPS data indicate that Indigenous victims were more likely than non-Indigenous victims to have been physically injured in the most serious assault. More specifically, more than one-third (36%) of Indigenous victims suffered injuries in the most serious assault they experienced in the 12 months preceding the survey. This proportion was more than double that of non-Indigenous victims (15%). Similarly, nearly one-third (32%) of Indigenous victims reported that their assailant was armed, compared with 13% of non-Indigenous victims (Table 10, Chart 11).

Chart 11 start

Data table for Chart 11

| Selected characteristics of the most serious assault | Indigenous persons | Non-Indigenous personsData table for Chart 11 Note ‡ | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| percent | 95% confidence interval | percent | 95% confidence interval | |||

| from | to | from | to | |||

| Victim felt blamedData table for Chart 11 Note 1 | 27.8 | 16.5 | 42.9 | 21.5 | 17.9 | 25.5 |

| Victim used victims services | 29.8Note * | 15.7 | 49.2 | 7.7 | 6.0 | 9.8 |

| Crime was reported to police | 39.3Note * | 25.0 | 55.7 | 17.8 | 14.8 | 21.2 |

| Victim suffered injuries | 36.2Note * | 21.7 | 53.7 | 15.0 | 12.3 | 18.3 |

| Offender had a weapon | 32.2Note * | 20.0 | 47.4 | 12.8 | 10.1 | 16.2 |

| Linked to offender's substance use | 46.6 | 31.6 | 62.3 | 35.7 | 31.6 | 40.1 |

| Offender was a manData table for Chart 11 Note 2 | 87.9 | 79.5 | 93.1 | 81.4 | 77.5 | 84.7 |

| Offender was a strangerData table for Chart 11 Note 3 | 31.7 | 20.1 | 46.1 | 45.5 | 41.0 | 50.2 |

| Took place in a private residence | 38.7 | 25.7 | 53.5 | 32.1 | 27.9 | 36.7 |

Source: Statistics Canada, Survey of Safety in Private and Public Spaces, 2018. |

||||||

Chart 11 end

The presence of injuries or weapons may be indicators of the potential level of severity of the assaults. In fact, these are key factors in classifying levels of sexual assault and assaults in the Criminal Code.

Indigenous people are twice as likely as non-Indigenous people to have reported the most serious assault to the police

Among both Indigenous and non-Indigenous people, the majority of assaults identified as the most serious experienced by victims in the 12 months preceding the SSPPS were not reported to the police. However, the most serious assaults on Indigenous people were approximately twice as likely to be brought to the attention of the police either as a result of the victim reporting the incident or otherwise.

Among Indigenous victims, nearly 4 in 10 (39%) assaults were brought to the attention of the police, compared with 18% among non-Indigenous victims. The difference was particularly pronounced among women, with one-third (32%) of Indigenous women and 12% of non-Indigenous women reporting the most serious assault (Table 10, Chart 11). Higher reporting rates may be another indicator of a higher level of severity, as the reporting rate tends to increase with severity (Sinha 2015).

Indigenous people were also more likely to have used victim services. Nearly one-third (30%) of Indigenous victims reported using services following the most serious assault, compared with 7.7% of non-Indigenous victims. Among victims who did not use victim services, the majority (51%) indicated that they did not feel the need to do so, and 29% said that the incident was too minor.Note

Nearly half of Indigenous women felt blamed

The term “secondary victimization” is sometimes used to refer to criticizing victims or making them feel responsible for their own victimization. A lack of support for victims or criticism can lead victims to blame themselves and therefore remain silent rather than confide in others, report the incident or seek help. Victim-blaming can have many negative emotional impacts on victims, such as increased distrust of others, anxiety or depression (Harber et al. 2015).

Nearly half (44%) of Indigenous women who were victims of a violent crime reported feeling blamed for the most serious assault they had experienced in the 12 months preceding the SSPPS. This proportion was more than double that noted among Indigenous men (17%). Among non-Indigenous women, it was rarer for them to feel blamed, with three-quarters (75%) of them reporting that they did not feel criticized or blamed for their most serious assault (Table 10).

Indigenous victims are less likely to have been assaulted by a stranger

Previous studies have shown that Indigenous victims were generally less likely than non-Indigenous victims to have been assaulted by a stranger (Allen 2020; Boyce 2016; Heidinger 2022). This trend was confirmed by the SSPPS data. Slightly less than one-third (32%) of the most serious assaults experienced by Indigenous people in the 12 months preceding the survey, excluding assaults by an intimate partner, were committed by a stranger (Table 10, Chart 11).

In comparison, almost half (46%) of non-Indigenous victims were targeted by a stranger. The difference was particularly pronounced among women, with 19% of Indigenous women having been assaulted by a stranger, compared with 39% of non-Indigenous women.

This difference may be, in part, because a greater proportion of Indigenous people than non-Indigenous people reside in rural or remote areas, where interactions with strangers may be less frequent. Other studies have also shown that crimes committed by strangers are less common in rural areas than in urban areas (Burczycka 2022; Perreault 2020).

Most Indigenous victims were assaulted by a man

Among both Indigenous (88%) and non-Indigenous (81%) people, most victims of a crime committed by a person other than an intimate partner were assaulted by one or more men. However, Indigenous people (6.3%) were less likely than non-Indigenous people (16%) to have been assaulted by one or more women. This difference was particularly pronounced among men, as 6.6% of Indigenous men were assaulted by one or more women, compared with 20% of non-Indigenous men (Table 10).

Indigenous people less likely to have been assaulted in a store or institution than non-Indigenous people

Overall, a relatively large proportion of assaults in 2018 occurred in a commercial or institutional establishment (37%), most often in a restaurant or bar (15% of all victims). However, Indigenous victims were less likely than non-Indigenous victims to have been assaulted in a commercial or institutional establishment (21% compared with 38%). Indigenous men, in particular, were more likely than non-Indigenous men to have been assaulted on the street or in another public place (51% versus 25%) (Table 10).

Indigenous women were more likely than non-Indigenous women to consider that the assault could be related to the assailant’s alcohol or drug use. For example, slightly more than half (52%) of Indigenous women believed that the most serious assault they had experienced could be related to the assailant’s substance use, compared with 29% of non-Indigenous women.

Indigenous victims more likely than non-Indigenous victims to have withdrawn from social activities because of the most serious assault

Among both Indigenous and non-Indigenous people, the vast majority of individuals who had been physically or sexually assaulted in the 12 months preceding the 2018 SSPPS reported having suffered emotional or psychological repercussions because of the most serious assault. However, compared with non-Indigenous victims, Indigenous victims were somewhat less likely to report being little affected (4.1% versus 12%) (Chart 12).

Chart 12 start

Data table for Chart 12

| Type of consequence | Indigenous persons | Non-Indigenous personsData table for Chart 12 Note ‡ | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| percent | 95% confidence interval | percent | 95% confidence interval | |||

| from | to | from | to | |||