Over-representation of Indigenous persons in adult provincial custody, 2019/2020 and 2020/2021

by Paul Robinson, Taylor Small, Anna Chen, and Mark Irving

Highlights

- In the two-year study period, 3% of the adult Indigenous population experienced incarceration in a provincial adult correctional centre. Indigenous men were most likely to experience incarceration, with almost one-in-ten Indigenous men aged 25-34 years experiencing incarceration over this period.

- In 2020/2021, Indigenous people in Canada were incarcerated at a much higher rate than non-Indigenous people. On an average day that year there were 42.6 Indigenous people in provincial custody per 10,000 population compared to 4.0 non-Indigenous people.

- According to the new Over-Representation Index, the incarceration rate of Indigenous persons was 8.9, or about 9 times higher than for non-Indigenous persons in 2020/2021.

- In 2020/2021, the Over-Representation Index for Indigenous people was highest in Saskatchewan at 17.7 times higher than the non-Indigenous population, followed by Alberta (10.8), British Columbia (7.9), Ontario (6.3), and Nova Scotia (1.9).

- Over-representation increased in 2020/2021 by 14% from the previous year, when the over-representation index was 7.8. Although, over-representation increased, the Incarceration rates for both Indigenous (down 18%) and non-Indigenous people (down 27%).

- The over-representation of Indigenous women in provincial correctional facilities (15.4 times higher than non-Indigenous women) was greater than for Indigenous men (8.4 times higher), in 2020/2021.

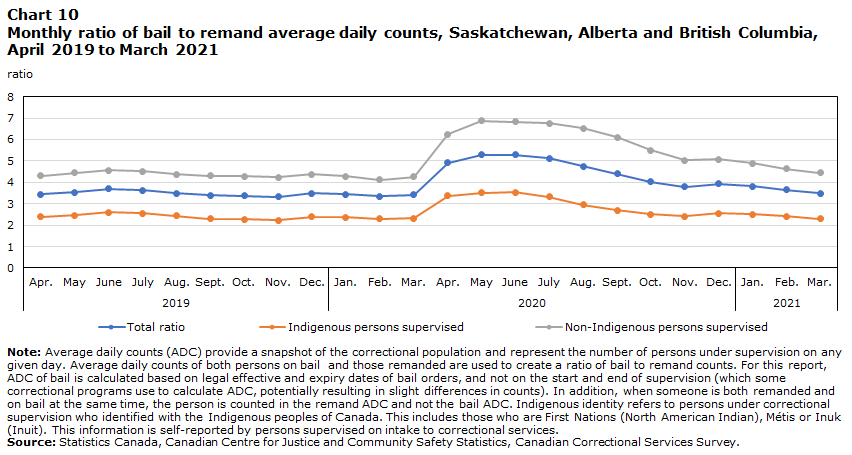

- In the three correctional services programs for which data are available, bail was used more frequently than remand for non-Indigenous persons. The ratio between average counts for bail and remand was 4.9 (that is for everyone one person in remand, almost 5 people were on bail), compared to 2.6 for the Indigenous population.

Introduction

The over-representation of specific population groups and sub-groups within and across the various sectors and stages of Canada’s criminal justice system remains a matter of significant and long-standing concern. In particular, the over-representation of IndigenousNote persons in correctional institutions across many parts of the country is a critical issue.

This Juristat article presents findings from the Canadian Correctional Services Survey (CCSS) in order to provide data and information on the extent of the over-representation of Indigenous persons in adult provincial custody for the fiscal yearsNote 2019/2020 and 2020/2021 for five provinces. Specifically, the analysis presented here capture adult corrections information from the following provincial correctional service programs: Nova Scotia, Ontario, Saskatchewan, Alberta, and British Columbia, which represent two thirds of the adult provincial/territorial custodial population.

This article is divided into two parts. The initial section presents, for the first time, three new population-based corrections indicators: Incarceration Rate, Over-Representation Index, and the Custodial Involvement Rate. These new indictors are used to analyze and compare the experiences of Indigenous and non-Indigenous populationsNote .

The second section of the article examines the use of bail and remand for Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations. For provincial correctional centres, the remand population comprise a majority of persons in custody (67% of the average daily count for all adult provincial correctional programs in 2020/2021). The section will analyze a number of different components of bail and remand, including examining (i) if there are differences in the conditions of bail between the two populations (e.g. use of certain conditions and mean and median number of conditions per bail order), (ii) the size of the bail and remand populations by creating a ratio of average daily counts to determine how frequently bail is used for certain populations relative to remand, and (iii) the number of remand admissions where the most serious offence related to the remand was a bail charge (e.g. when an individual is accused of failing to comply with a bail order or fails to appear in court).

Brief background and context

For at least three decades, a Royal CommissionNote , Commissions of InquiryNote , Supreme Court of Canada rulingsNote and other official investigationsNote have brought critical attention and awareness to the issue of the over-representation of Indigenous persons in Canada’s criminal justice system, including corrections.

There are numerous circumstances, explanations, and interpretations as to why Indigenous persons are significantly over-represented. Many of these are multifaceted, interrelated and relatively complex. For instance, factors and considerations – either on their own or in some combination – such as colonialism, displacement, socio-economic and cultural marginalization, and systemic discrimination have frequently been presented in the literature and in public discourse as plausible explanations for Indigenous over-representation (Clark, 2019; Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples, 1996).

The historical and ongoing impacts of colonialism and their direct links to criminal behaviour are well-documented (Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples, 1996; Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, 2015a). Colonialism, in its various forms and manifestations, has also been directly associated with culture clash, socio-economic marginalization and systemic discrimination (Clark, 2019). The existing literature clearly and comprehensively documents the effects of being dispossessed of traditional lands, being subjected to restrictive and discriminatory legislation such as the Indian Act, and experiencing the legacy of residential schools and the Sixties Scoop. These and other important factors have directly and indirectly contributed to the tragic toll on Indigenous individuals, families, and communities over many generations (Clark, 2019).

Many Indigenous peoples and communities continue to experience numerous health and socio-economic inequalities, challenges, and related issues. Among others, these include poor living conditions and sub-standard levels of housing, high rates of unemployment, harms associated with substance use, family violence, a lack of access to health care, and a high incidence of suicide especially for Indigenous youth (Clark, 2019).

Broadly speaking, Indigenous cultures – which are numerous and varied in Canada – tend to view and understand justice and wrong-doing somewhat differently than non-Indigenous cultures. Unlike the mainstream criminal justice system and its adversarial approach and focus on punishment and the finding of guilt, Indigenous approaches and world-views tend to emphasize rehabilitation, empowerment and healing at both the individual and community levels (Clark, 2019).

In June 1995, the Parliament of Canada passed former Bill C-41 – a bill amending the Criminal Code with regard to sentencing. The new law came into force in 1996. One of the main objectives of the legislation was to address the over-representation of Indigenous persons in custody (Clark, 2019). Specifically, paragraph 718.2(e) of the Criminal Code set out that before a court imposes a sentence, “all available sanctions other than imprisonment that are reasonable in the circumstances should be considered for all offenders, with particular attention to the circumstances of aboriginal offenders”.

A landmark Supreme Court of Canada case that tested the applicability of the law involved Jamie Gladue – a young Indigenous woman convicted of murdering her common-law husband.

In R v. Gladue in 1999, justices of the Supreme Court of Canada ruled that the lower courts should carefully consider an Indigenous offender’s background during sentencing. In another very important case in 2012 – R v. Ipeelee – the Supreme Court reaffirmed, provided further clarification, and expanded on the sentencing principles established in the Gladue decision. Despite these two important Supreme Court of Canada decisions as well as various sentencing and other criminal justice reforms over the years, the over-representation of Indigenous persons in corrections remains a critical issue and efforts are still ongoing by federal and provincial/territorial governments to address the over-representation of Indigenous populations in the justice system.

Part One – New indicators of over-representation

In 2020/2021, the Indigenous incarceration rate (18 years and over) in provincial custody was 42.6 per 10,000 population

In 2020/2021, for the five adult provincial correctional service programs reporting to the CCSS, the average daily count (ADC) of Indigenous persons in custody was about 4,100. This resulted in an Indigenous incarceration rate of 42.6 per 10,000 population (Table 1). Of the five provinces, Saskatchewan had the highest adult Indigenous incarceration rate at 100.7, followed by Alberta (54.9), Ontario (32), British Columbia (22) and Nova Scotia (7.9).

For the non-Indigenous population in the five reporting provinces, the incarceration rate was 4.0 in 2020/2021 (Table 2). There was less variation in the non-Indigenous incarceration rates across provinces. Ontario had the highest non-Indigenous incarceration rate (4.5), while British Columbia had the lowest (2.3). Note that comparisons between the Indigenous and non-Indigenous and done using the Over-Representation Index, which uses adjusted incarceration rates, accounting for age and gender between the underlying population. This analysis is presented in the following sections.

Start of text box 1

Text box 1

Indicators of over-representation in Correctional Services

The Incarceration Rate measures the proportion of a population in custody on an average day in the yearNote . It is calculated by taking the Average Daily Count (ADC) of the correctional population, dividing it by the general population estimate for that same year, then multiplying by 10,000Note . For the Canadian Correctional Services Survey (CCSS), the rate is expressed as the number of incarcerated persons per 10,000 population. Through the CCSS, the ADC is now available by Indigenous and racialized groups allowing Statistics Canada to produce both IndigenousNote and non-Indigenous incarceration rates.

The Over-Representation Index calculates the relative difference between Indigenous and non-Indigenous rates by controlling for age and sex differences between populations, as if both populations have an age/sex profile identical to the national population distributionNote . These adjusted rates address the impact demographic differences the underlying population may have on measuring over-representation.

The Custodial Involvement Rate (CIR) measures the proportion of a specific population experiencing incarceration over a reference period. The measure identifies the number of unique persons spending at least one day in custody during the reference period for a defined population (e.g. Indigenous adults, etc.), then calculates the percentage of the population experiencing incarceration.

For more background information on the development and use of these indicators, refer to Background, new indicators of over-representation

End of text box 1

Incarceration rates are higher for Indigenous men

In 2020/2021, the incarceration rate for Indigenous adult men was consistently higher than for Indigenous adult women in all five provinces (Table 1). For Indigenous men, the incarceration rate for all five adult provincial correctional service programs was 77.8 compared to 9.4 for Indigenous women. For non-Indigenous populations, the incarceration rate for men was 7.6 and for women it was 0.5 (Table 2).

Incarceration rates decreased in 2020/2021 from the previous year

Compared to the previous year, Indigenous and non-Indigenous incarceration rates decreased in 2020/2021. For the Indigenous population, the incarceration rate dropped 18% from the previous year, whereas the non-Indigenous incarceration rate fell 27% (Chart 1). Much of this decrease was attributable to the onset of COVID-19 (Statistics Canada, 2022, April 20). Correctional institutions faced unique challenges when it came to preventing COVID-19 infection and transmission among custodial populations, given the close-proximity living conditions and the lack of physical distancing options. Reducing the number of people held in correctional institutions was also seen as a preventive measure to reduce the public health risk. Some of the steps taken by the Canadian criminal justice and correctional systems to reduce the size of the population living in correctional institutions since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic included temporary or early release of people in custody who are considered at low risk to reoffend; extended periods for parole appeals and access to medical leave privileges; and alternatives to custody while awaiting trials, sentencing and bail hearings.

Chart 1 start

Data table for Chart 1

| 2019/2020 | 2020/2021 | |

|---|---|---|

| rate | ||

| Indigenous males | 92.5 | 77.8 |

| Indigenous females | 13.1 | 9.4 |

| Indigenous total | 51.7 | 42.6 |

| Non-Indigenous males | 10.3 | 7.6 |

| Non-Indigenous females | 0.8 | 0.5 |

| Non-Indigenous total | 5.5 | 4.0 |

|

Note: Represents data from Nova Scotia, Ontario, Saskatchewan, Alberta and British Columbia. The incarceration rate measures the proportion of a population in custody on an average day in the year. It is calculated by taking the average daily count (ADC) of the correctional population, dividing it by the general population estimate for that same year, then multiplying by 10,000. Indigenous identity refers to persons under correctional supervision who identified with the Indigenous peoples of Canada. This includes those who are First Nations (North American Indian), Métis or Inuk (Inuit). This information is self-reported by persons supervised on intake to correctional services. Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics, Canadian Correctional Services Survey. |

||

Chart 1 end

Start of text box 2

Text box 2

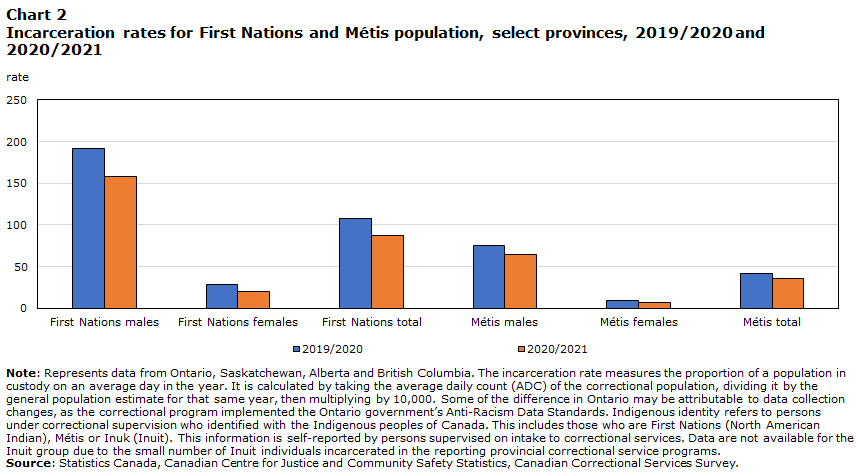

Incarceration rate higher for First Nations peoples than for Métis

Data on Indigenous group is available from OntarioNote , Saskatchewan, Alberta, and British Columbia. Looking at incarceration rates by Indigenous group, persons supervised identifying as First Nations had a higher incarceration rate than those identifying as MétisNote . In 2020/2021, the incarceration rate for the First Nations population was 86.8 (per 10,000 population), compared to a rate of 35.4 for the Métis population (Chart 2). This trend was consistent across all four provincial jurisdictions for both the 2019/2020 and 2020/2021 reference periods.

Chart 2 start

Data table for Chart 2

| 2019/2020 | 2020/2021 | |

|---|---|---|

| rate | ||

| First Nations males | 191.1 | 157.6 |

| First Nations females | 28.1 | 19.8 |

| First Nations total | 107.2 | 86.8 |

| Métis males | 75 | 64.6 |

| Métis females | 9.3 | 7.2 |

| Métis total | 41.5 | 35.4 |

|

Note: Represents data from Ontario, Saskatchewan, Alberta and British Columbia. The incarceration rate measures the proportion of a population in custody on an average day in the year. It is calculated by taking the average daily count (ADC) of the correctional population, dividing it by the general population estimate for that same year, then multiplying by 10,000. Some of the difference in Ontario may be attributable to data collection changes, as the correctional program implemented the Ontario government’s Anti-Racism Data Standards. Indigenous identity refers to persons under correctional supervision who identified with the Indigenous peoples of Canada. This includes those who are First Nations (North American Indian), Métis or Inuk (Inuit). This information is self-reported by persons supervised on intake to correctional services. Data are not available for the Inuit group due to the small number of Inuit individuals incarcerated in the reporting provincial correctional service programs. Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics, Canadian Correctional Services Survey. |

||

Chart 2 end

Incarceration rates were higher for men than for women in both Indigenous groups. For the First Nations population in the four provinces, the incarceration rate was 157.6 for men in 2020/2021 compared to 19.8 for women. For the Métis population, the male incarceration rate was 64.6 and the female rate was 7.2.

End of text box 2

The over-representation of Indigenous persons in corrections is about 9 times higher than non-Indigenous persons

In 2020/2021, the over-representation for the 5 provinces, as measured by the Over-Representation Index, was 8.9, indicating that the Indigenous incarceration rate was about 9 times higher than the non-Indigenous incarceration rate when adjusted for age and sex differences among the two populations. Among the five provinces, over-representation was highest in Saskatchewan at 17.7, followed by Alberta (10.8), British Columbia (7.9), Ontario (6.3), and Nova Scotia (1.9).

While the Over-Representation Index considers age and sex differences, it does not incorporate differences in the composition of the non-Indigenous population. Provincial differences related to the proportion of the non-Indigenous population comprised of racialized groups, especially Black Canadians (who are also over-represented in correctional systems) may impact findings on the over-representation of Indigenous people. For example, provinces like Ontario and Nova Scotia, with proportionally large Black populations, may have relatively higher non-Indigenous incarceration rates, which lessens the appearance of over-representation of Indigenous adults.

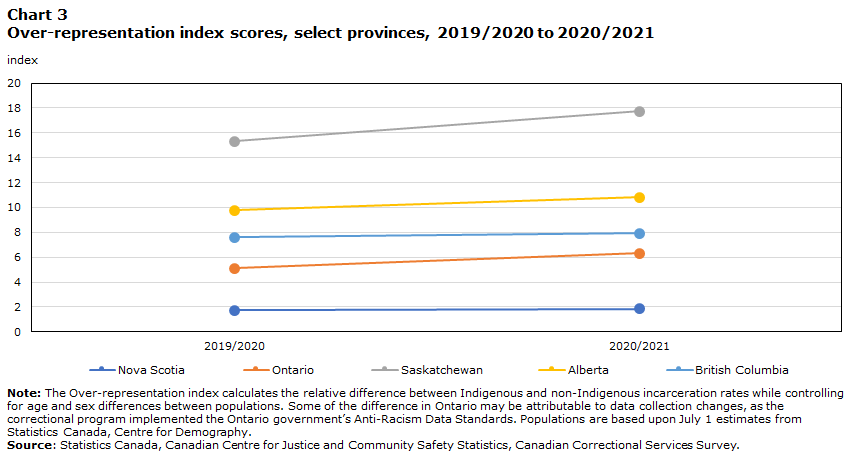

Over-representation of Indigenous persons increased by 14% between 2019/2020 and 2020/2021

Compared to the previous year, when the Over-Representation Index was 7.8, over-representation increased by 14% in 2020/2021. Over-representation increased the most in Ontario, up 24% from the previous year (although some of the difference may be attributable to data collection changes, as the correctional program implemented the Ontario government’s Anti-Racism Data StandardsNote in August 2020) (Chart 3). Over-representation also increased in Saskatchewan (+15%), and Alberta (10%) as well as more moderately increasing in Nova Scotia (+6%) and British Columbia (+3%).

Chart 3 start

Data table for Chart 3

| 2019/2020 | 2020/2021 | |

|---|---|---|

| index | ||

| Nova Scotia | 1.7 | 1.9 |

| Ontario | 5.1 | 6.3 |

| Saskatchewan | 15.3 | 17.7 |

| Alberta | 9.8 | 10.8 |

| British Columbia | 7.7 | 7.9 |

|

Note: The Over-representation index calculates the relative difference between Indigenous and non-Indigenous incarceration rates while controlling for age and sex differences between populations. Some of the difference in Ontario may be attributable to data collection changes, as the correctional program implemented the Ontario government’s Anti-Racism Data Standards. Populations are based upon July 1 estimates from Statistics Canada, Centre for Demography. Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics, Canadian Correctional Services Survey. |

||

Chart 3 end

Over-representation increased despite lower incarceration rates in 2020/2021 due primarily to COVID-19. As detailed in the previous section, the Indigenous incarceration rate was down 18%; however, the non-Indigenous rate fell even further with a decrease of 27% from the previous year.

Over-representation of Indigenous women is greater than for Indigenous men

While Indigenous women have much lower incarceration rates than Indigenous men (as detailed in the previous section), over-representation of Indigenous women compared to non-Indigenous women is much higher than for men. Using the Over-Representation Index, the incarceration rates of Indigenous women in adult custody were 15.4 times higher than for non-Indigenous women. In comparison, for men, over-representation was 8.4 in 2020/2021.

This pattern was found in all five provincial correctional programs involved in this study. Over-representation of Indigenous women was highest in Saskatchewan (28.5), followed by Alberta (15.5), Ontario (12.5), British Columbia (11.2), and Nova Scotia (3.3) (Chart 4).

Chart 4 start

Data table for Chart 4

| Male | Female | |

|---|---|---|

| index | ||

| Nova Scotia | 1.8 | 3.3 |

| Ontario | 5.9 | 12.5 |

| Saskatchewan | 16.9 | 28.5 |

| Alberta | 10.4 | 15.5 |

| British Columbia | 7.8 | 11.2 |

|

Note: The Over-representation index calculates the relative difference between Indigenous and non-Indigenous incarceration rates while controlling for age and sex differences between populations. Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics, Canadian Correctional Services Survey. |

||

Chart 4 end

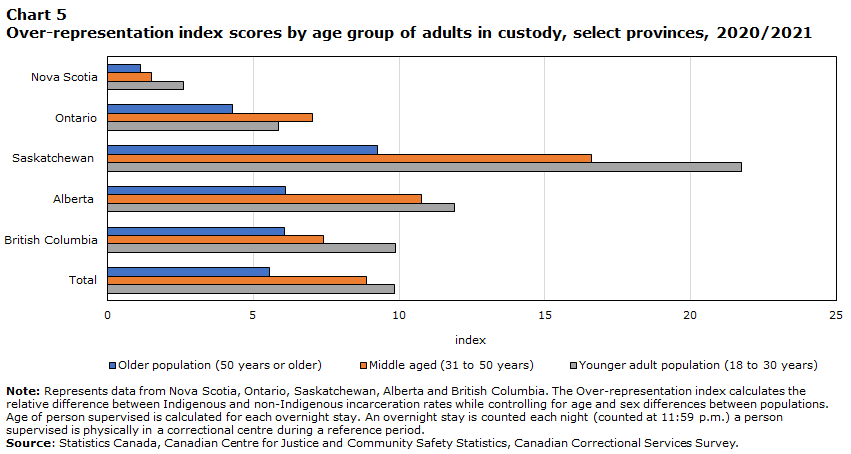

Younger adults have the highest over-representation of Indigenous persons in custody compared to middle-aged and older adults

Looking at different age groups, we can also compare over-representation for younger adults (18-30 years), middle-aged adults (31-50 years), and older adults (51+ years). Among the five provinces, over-representation was highest for younger adults, with an Over-Representation Index of 9.8 (Chart 5). Over-representation was also high for middle-aged adults (8.9) and more moderate for older adults (5.5). This pattern was the same in all jurisdictions, save for Ontario where over-representation for middle-aged adults (7.0) was slightly higher than for younger adults (5.9).

Chart 5 start

Data table for Chart 5

| Older population (50 years or older) | Middle aged (31 to 50 years) | Younger adult population (18 to 30 years) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| index | |||

| Nova Scotia | 1.1 | 1.5 | 2.6 |

| Ontario | 4.3 | 7.0 | 5.9 |

| Saskatchewan | 9.2 | 16.6 | 21.8 |

| Alberta | 6.1 | 10.8 | 11.9 |

| British Columbia | 6.1 | 7.4 | 9.9 |

| Total | 5.5 | 8.9 | 9.8 |

|

Note: Represents data from Nova Scotia, Ontario, Saskatchewan, Alberta and British Columbia. The Over-representation index calculates the relative difference between Indigenous and non-Indigenous incarceration rates while controlling for age and sex differences between populations. Age of person supervised is calculated for each overnight stay. An overnight stay is counted each night (counted at 11:59 p.m.) a person supervised is physically in a correctional centre during a reference period. Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics, Canadian Correctional Services Survey. |

|||

Chart 5 end

Over-representation of Indigenous persons is higher for sentenced persons than for remanded persons

In adult provincial custody, the vast majority of persons supervised are either remanded or sentenced. Remanded custody occurs when a person is incarcerated on charges and awaiting trial or sentencing. Sentenced custody consists mostly of persons serving a provincial custody sentence of less than two years, as well as persons on a federal sentence of two years or more awaiting transfer to a federal facility. It may also include those persons supervised by Correctional Service Canada but in temporary custody in a provincial correctional centre for community release and parole suspensions or awaiting a court appearance.

In most provincial correctional programs, on an average day, there are more individuals on remand than in sentenced custody (Statistics Canada, 2022). However, in 2020/2021, over-representation was higher for persons in sentenced custody. For persons supervised in sentenced custody, over-representation was 9.8, compared to 8.5 for persons supervised in remand.

Part Two – New indicators of persons experiencing incarceration

This section will examine the Custodial Involvement Rate (CIR) in five reporting provinces (Nova Scotia, Ontario, Saskatchewan, Alberta, and British Columbia) over a two-year period (from 2019/2020 to 2020/2021) to examine provincial differences in the custodial involvement of different groups by Indigenous identity, sex, and age.

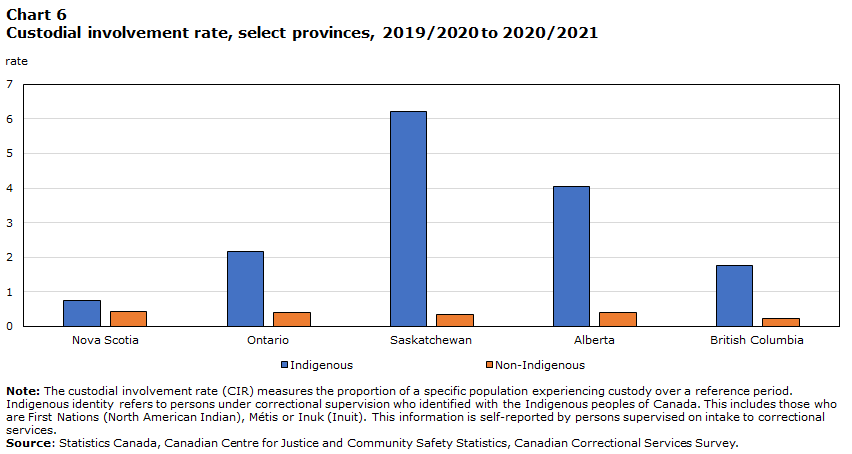

From April 1, 2019, to March 31, 2021, 3% of the adult Indigenous population experienced incarceration

Over a two-year period, from 2019/2020 to 2020/2021, just over 28,000 Indigenous adults experienced custody in a provincial correctional centre in Nova Scotia, Ontario, Saskatchewan, Alberta, and British Columbia, which was 3% of the adult Indigenous population in the five reporting provincesNote . This percentage was over 8.2 times higher than the proportion of non-Indigenous adults (<1%) experiencing incarceration over the same period. Within all five provinces, the proportion of Indigenous adults experiencing incarceration was greater than non-Indigenous adults over this period (Chart 6).

Chart 6 start

Data table for Chart 6

| Nova Scotia | Ontario | Saskatchewan | Alberta | British Columbia | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rate | |||||

| Indigenous | 0.7 | 2.2 | 6.2 | 4.1 | 1.7 |

| Non-Indigenous | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.2 |

|

Note: The custodial involvement rate (CIR) measures the proportion of a specific population experiencing custody over a reference period. Indigenous identity refers to persons under correctional supervision who identified with the Indigenous peoples of Canada. This includes those who are First Nations (North American Indian), Métis or Inuk (Inuit). This information is self-reported by persons supervised on intake to correctional services. Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics, Canadian Correctional Services Survey. |

|||||

Chart 6 end

Among the five provinces, the CIR was highest for Indigenous persons in Saskatchewan at 6%, followed by Alberta (4%), Ontario (2%), British Columbia (2%), and Nova Scotia (1%).

Provincial CIR patterns are similar to those for the Crime Severity Index (CSI), which measures the volume and the seriousness of police-reported crime in Canada (Statistics Canada, 2016, July 20). For example, the CSI was the highest among the Prairie provinces and British Columbia in 2021 (Moreau, 2022). Likewise, Saskatchewan and Alberta had the highest custodial involvement rates of the five reporting provinces and had the largest relative impact on the overall CIR. One difference was noted for Ontario where the CSI was lower than that of Nova Scotia, while the CIR was about three times higher.

In the five provinces, Indigenous men are most likely to experience incarceration

The CIR was highest for Indigenous men. Over the two-year period, 5% of Indigenous men experienced incarceration in the five reporting provinces (Chart 7). In comparison, 1% of non-Indigenous men experienced incarceration over the same period. Indigenous women also experienced incarceration at a slightly higher rate (1%) than non-Indigenous women (< 1%). This pattern was observed across all five of the reporting provincial correctional programs.

Chart 7 start

Data table for Chart 7

| Nova Scotia | Ontario | Saskatchewan | Alberta | British Columbia | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rate | |||||

| Female | |||||

| Indigenous | 0.3 | 0.9 | 2.6 | 1.8 | 0.5 |

| Non-Indigenous | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 |

| Male | |||||

| Indigenous | 1.2 | 3.5 | 9.9 | 6.4 | 3.1 |

| Non-Indigenous | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.4 |

|

Note: The custodial involvement rate (CIR) measures the proportion of a specific population experiencing custody over a reference period. Indigenous identity refers to persons under correctional supervision who identified with the Indigenous peoples of Canada. This includes those who are First Nations (North American Indian), Métis or Inuk (Inuit). This information is self-reported by persons supervised on intake to correctional services. Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics, Canadian Correctional Services Survey. |

|||||

Chart 7 end

Over the two-year period, the CIR for Indigenous men was the highest in Saskatchewan, where one in 10 (10%) of the Indigenous men had experienced incarceration, followed by Alberta (6%). The rates were similar in Ontario (4%) and British Columbia (3%), while Nova Scotia had the lowest CIR (1%) over the period.

Almost one-in-ten Indigenous men aged 25-34 years experienced incarceration over the two-year period

Over the two-year period, almost one-in-ten (8%) Indigenous men aged 25-34 years experienced incarceration in the five reporting provincesNote , the age group with the highest incarceration rates in provincial custody. In comparison, 1% of non-Indigenous men of the same age group experienced incarceration over the period.

There was some variation among provinces in the CIR for Indigenous men aged 25 to 34 years. In Saskatchewan, 16% of Indigenous men aged 25 to 34 experienced incarceration over the two-year period, followed by Alberta (10%), Ontario (6%), British Columbia (6%), and Nova Scotia (3%) (Chart 8). In comparison, the CIR for non-Indigenous men aged 25-34 years was lower in all five provinces. Nova Scotia had the highest CIR for this group (2%), while Ontario, Saskatchewan, Alberta, and British Columbia each had a rate of about 1%. The relatively higher rates in Nova Scotia and Ontario may be due to the proportionally large Black populations in those provinces (Statistics Canada, 2019), which is another group that is over-represented in the correctional system (Statistics Canada, 2022, April 20).

Chart 8 start

Data table for Chart 8

| Nova Scotia | Ontario | Saskatchewan | Alberta | British Columbia | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rate | |||||

| Indigenous | 2.6 | 6.2 | 16.4 | 10.3 | 5.5 |

| Non-Indigenous | 1.6 | 1.3 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 0.7 |

|

Note: The custodial involvement rate (CIR) measures the proportion of a specific population experiencing custody over a reference period. Indigenous identity refers to persons under correctional supervision who identified with the Indigenous peoples of Canada. This includes those who are First Nations (North American Indian), Métis or Inuk (Inuit). This information is self-reported by persons supervised on intake to correctional services. Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics, Canadian Correctional Services Survey. |

|||||

Chart 8 end

Indigenous women aged 25-34 years old also experience incarceration at a higher rate than non-Indigenous young women. During the two-year period, 2.3% of indigenous young women experienced incarceration in the five provinces, compared to 0.2% of non-Indigenous young women. There was some variation among the provinces, as Saskatchewan had the highest CIR for Indigenous young women (5%). This was followed by Alberta (3%), Ontario (2%), Nova Scotia (1%), and British Columbia (1%). In comparison, the CIR for non-Indigenous women aged 25-34 years was lower in all five provinces.

Part Three – Use of bail and remand for Indigenous and non- Indigenous persons

The first part of this article focused on the analysis of new indicators from the CCSS to provide information on the extent of Indigenous over-representation in adult custody. When examining this issue, it is also important to consider factors driving over-representation and impacting legislative change. For example, the use of bail and remand have been the focus of recent legislative reform to address challenges facing the criminal justice system and the over-representation of Indigenous persons.

In provincial custody, the majority of persons supervised are in remand, which is court-ordered temporary detention of a person, pursuant to a remand warrant, while awaiting trial or sentencing. In 2020/2021, for all provinces and territories, 67% of persons supervised in an adult provincial custodial centre on an average day were on remand (Statistics Canada, 2022).

As an alternative to remand, persons may be supervised in the community under a bail order. Bail is the release of an accused into the community while awaiting a trial in court or sentencing. In certain circumstances, bail can be granted by the police; otherwise, bail is granted by a court or a justice of the peace at a bail hearing. Bail supervision is governed by a judicial interim release order (Criminal Code of Canada, section 515). Under the guidelines set out in this section, an accused person will be granted bail if the police or court are satisfied the person will attend court to answer to the charge, the person does not pose a public safety risk and confidence in the criminal justice system will be maintained if the accused person is granted bail.

Bail may be revoked if the accused breaches a condition. In addition to the revocation, the accused may face an additional criminal charge of failure to appear or failure to comply with a condition of an undertaking or recognizance under section 145 of the Criminal Code of Canada.

Start of text box 3

Text box 3

Introduction of Bill C-75 and bail reform

To address significant challenge facing Canada’s criminal justice system, such as longer trials, large remand populations, the high number of administration of justice offences processed in criminal court and over-representation of Indigenous and Black Canadians (Justice Canada, 2022), on March 29, 2018, the Canadian government introduced Bill C-75, An Act to amend the Criminal Code, the Youth Criminal Justice Act and other Acts and to make consequential amendments to other Acts. (Library of Parliament, 2019, Justice Canada, 2019). The stated goal of the legislation was “to reduce delays in the criminal justice system and to make it more modern and efficient” (Justice Canada, 2021). The Act received Royal Assent in June 2019 and all provisions were fully in force by December 18, 2019. Among other provisions, former Bill C-75 changed the processes and procedures for bail to ensure that accused persons are released at the earliest possible opportunity and bail conditions are reasonable, relevant to the offence and necessary to ensure public safety. It further requires that the circumstances of Indigenous accused and accused from vulnerable populations are considered at bail.

End of text box 3

This section of the article will examine some new indicators related to the use of bail and remand to determine the extent that use differs between Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations. Using data from three correctional programs that operate bail programs and report to the CCSS, namely Saskatchewan, Alberta and British Columbia, this report will examine whether the number and types of bail conditions ordered differ between Indigenous and non-Indigenous persons supervised on bail. In addition, we will compare average daily counts of remand and bail for Indigenous and non-Indigenous persons, to identify any differences in the relative use of bail and remand between these populations. Finally, for all reporting provinces, we will examine the number of remand admissions where the most serious offence was failure to comply with a recognizance order.

In over one-third of bail orders, the person supervised self-identified as Indigenous

Between 2019/2020 to 2020/2021, about 93,550 bail orders were received by the three provincial correctional programs that supervise bail (Saskatchewan, Alberta, and British Columbia) (Table 3). In these provincial programs, bail orders with a report to supervisor condition are overseen by provincial community corrections. It should be noted that bail orders without this condition are not included in the analysis, and results only reflect bail supervision by correctional services, and not all bail cases authorized in these jurisdictions.

In 2020/2021, just over one-third (39%) of the total number of bail orders, the person supervised self-identified as Indigenous. Results varied by province. In Saskatchewan, the person supervised in 73% of bail orders was Indigenous, compared to 41% of orders in Alberta and 31% in British Columbia (Table 3). Proportions changed little between 2019/2020 and 2020/2021.

No difference in the median number of bail conditions between Indigenous and non-Indigenous persons

There was little difference in the median number of conditions per bail order for Indigenous and non-Indigenous persons. For both populations, the median number of conditions was 6 (Table 4) for all orders received in 2020/2021. For both groups, the median number of bail conditions did not change from the previous year.

Provincially, the median number of bail conditions was 6 in Alberta and British Columbia, and 8 in Saskatchewan (Table 4) for orders received in 2020/2021. For each province, median number of conditions were the same for both Indigenous and non-Indigenous persons being supervised.

In 2020/2021, the mean number of conditions on bail orders for the three provinces was 6.6 for both Indigenous and non-Indigenous persons. There was little difference in mean number of conditions between the two fiscal years.

In each province, the mean number of bail conditions was slightly lower for orders where the person supervised was Indigenous in 2020/2021. This was particularly true in Saskatchewan and Alberta, where the mean number of bail conditions was notably lower for Indigenous persons. In Saskatchewan, bail orders where the person identified as Indigenous had 7.7 conditions, compared to 8.4 conditions for bail orders where the person supervised was non-Indigenous. Similarly, in Alberta, there was a lower mean of 6.7 conditions for Indigenous persons compared to 7.3 for non-Indigenous persons. In British Columbia, there was little difference in the mean number of bail conditions between Indigenous (6.1) and non-Indigenous (6.2) persons.

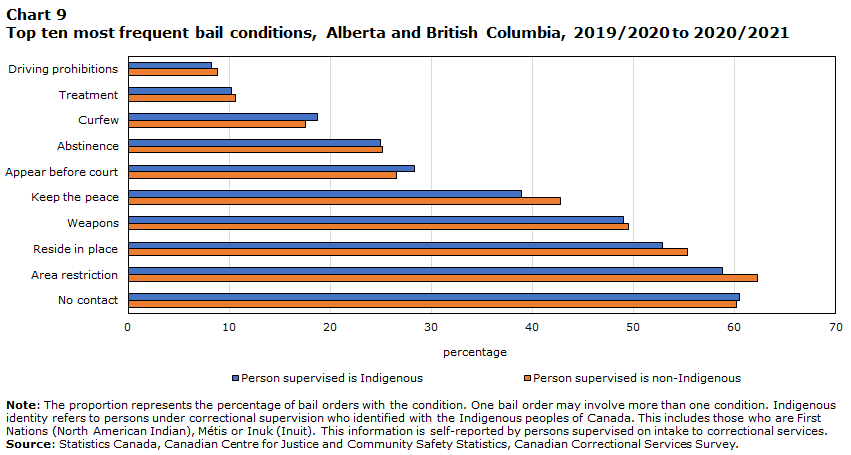

Little difference in the type of bail conditions between Indigenous and non-Indigenous persons

Information on the types of bail conditions issued by the court is available for Alberta and British Columbia. For this analysis, conditions related to supervision (for example, the requirements to report to a supervisor, which is present in almost all bail orders, and notification of changes, such as change of address) have been excluded.

Start of text box 4

Text box 4

Definitions – most common bail conditions

No contact condition - requires the accused to not be in contact with specified persons, or types of persons (e.g., persons who use substances).

Area restriction condition - the accused is restricted from entering certain establishments (like bars and pubs) or travelling beyond a specified area.

Reside in place - the accused is required to live at a specified address.

Weapons - conditions that prohibit the accused from possessing weapons.

Keep the peace (and be of good behaviour) - requires the accused to maintain public order and to refrain from unlawful behaviour.

Abstinence - avoidance of drinking alcohol and/or using drugs.

Appear before court - condition to appear before a court of law when required.

Curfew - requirement to remain indoors during specified hours of the day.

Treatment - requirements to attend or seek treatment, for example alcohol counseling.

Driving prohibitions - accused is not allowed to drive a motor vehicle or must surrender driver’s licence.

End of text box 4

In 2019/2020 and 2020/2021, the most common bail conditions found in bail orders issued in Alberta and British Columbia were “No contact” and “Area restriction” conditions, each found in 61% of bail orders. The third most common condition was “Reside in place”. This condition was specified in 53% of bail orders.

Other common conditions in bail orders included “Weapons” (on 49% of bail orders), “Keep the peace” (41%), “Appear before court” (28%), “Abstinence from alcohol and/or drugs” (25%), “Curfew” (16%), “Treatments” (10%), and “Driving prohibitions” (8%).

Although there was some variation in the use of bail conditions between Alberta and British Columbia, the most common conditions were used at roughly the same frequency. The most common conditions in Alberta were “Reside in place” (62%), “No contact” (57%) and “Weapons” (53%). In British Columbia, “Area restrictions” (66%), “No contact” (63%), and “Reside in place” (49%) were used most frequently in bail orders. There was very little difference in the use of bail conditions between orders where the person supervised identified as Indigenous and orders for non-Indigenous persons (Chart 9).

Chart 9 start

Data table for Chart 9

| Person supervised is Indigenous | Person supervised is non-Indigenous | |

|---|---|---|

| percentage | ||

| Driving prohibitions | 8 | 9 |

| Treatment | 10 | 11 |

| Curfew | 19 | 18 |

| Abstinence | 25 | 25 |

| Appear before court | 28 | 27 |

| Keep the peace | 39 | 43 |

| Weapons | 49 | 50 |

| Reside in place | 53 | 55 |

| Area restriction | 59 | 62 |

| No contact | 60 | 60 |

|

Note: The proportion represents the percentage of bail orders with the condition. One bail order may involve more than one condition. Indigenous identity refers to persons under correctional supervision who identified with the Indigenous peoples of Canada. This includes those who are First Nations (North American Indian), Métis or Inuk (Inuit). This information is self-reported by persons supervised on intake to correctional services. Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics, Canadian Correctional Services Survey. |

||

Chart 9 end

Bail used more frequently than remand for non-Indigenous persons than for Indigenous persons

Between April 1, 2019 and March 31, 2021, the average daily counts of persons on bail was just over 17,800 for the three reporting provinces (Saskatchewan, Alberta and British Columbia). The average daily count of remanded persons was 4,630Note , resulting in a bail to remand ADC ratio of 3.8 (meaning on an average day there are roughly four times as many persons supervised in bail than in remand).

The bail to remand ADC ratio was higher for non-Indigenous persons in the three reporting provinces, meaning overall bail was used more frequently for non-Indigenous persons. Over the two-year time period the ratio was 4.9 for non-Indigenous persons, compared to 2.6 for Indigenous persons.

These patterns were similar in all reporting jurisdictions. Bail to remand ADC ratio was highest in British Columbia (8.0), followed by Alberta (2.3) and Saskatchewan (2.1) (Table 5). In all three provinces as well, the non-Indigenous ratios are higher than the Indigenous ratios. In British Columbia, for example the non-Indigenous bail to remand ADC ratio is 8.5 compared to 6.2 for the Indigenous population. Similar differences are found in Alberta (2.9 to 1.6) and Saskatchewan (3.0 to 1.8). Caution should be used when making comparisons between provinces and between Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations, given the comparisons are not controlled for type of offence or risk level of the persons supervised, among other factors, which may differ between populations and affect the use of bail and remand.

COVID-19 greatly increased use of bail early in 2020/2021, however use dropped back to previous levels by the end of 2020/2021

Prior to the start of the COVID-19, the use of bail, relative to remand, was fairly constant in the three reporting provinces. Between April 2019 and March 2020, the overall bail to remand ADC ratio was 3.5Note (Chart 10) with little monthly variation. The use of bail was also consistent for the Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations, with bail to remand ADC ratios of 2.4 and 4.3 respectively.

Chart 10 start

Data table for Chart 10

| Total | Indigenous persons supervised | Non-Indigenous persons supervised | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ratio | |||

| 2019 | |||

| April | 3.4 | 2.4 | 4.3 |

| May | 3.5 | 2.5 | 4.4 |

| June | 3.7 | 2.6 | 4.6 |

| July | 3.6 | 2.6 | 4.5 |

| August | 3.5 | 2.4 | 4.4 |

| September | 3.4 | 2.3 | 4.3 |

| October | 3.4 | 2.3 | 4.3 |

| November | 3.3 | 2.2 | 4.2 |

| December | 3.5 | 2.4 | 4.4 |

| 2020 | |||

| January | 3.4 | 2.4 | 4.3 |

| February | 3.3 | 2.3 | 4.1 |

| March | 3.4 | 2.3 | 4.3 |

| April | 4.9 | 3.4 | 6.2 |

| May | 5.3 | 3.5 | 6.9 |

| June | 5.3 | 3.5 | 6.8 |

| July | 5.1 | 3.3 | 6.8 |

| August | 4.8 | 3.0 | 6.5 |

| September | 4.4 | 2.7 | 6.1 |

| October | 4.0 | 2.5 | 5.5 |

| November | 3.8 | 2.4 | 5.0 |

| December | 3.9 | 2.6 | 5.1 |

| 2021 | |||

| January | 3.8 | 2.5 | 4.9 |

| February | 3.6 | 2.4 | 4.6 |

| March | 3.5 | 2.3 | 4.4 |

|

Note: Average daily counts (ADC) provide a snapshot of the correctional population and represent the number of persons under supervision on any given day. Average daily counts of both persons on bail and those remanded are used to create a ratio of bail to remand counts. For this report, ADC of bail is calculated based on legal effective and expiry dates of bail orders, and not on the start and end of supervision (which some correctional programs use to calculate ADC, potentially resulting in slight differences in counts). In addition, when someone is both remanded and on bail at the same time, the person is counted in the remand ADC and not the bail ADC. Indigenous identity refers to persons under correctional supervision who identified with the Indigenous peoples of Canada. This includes those who are First Nations (North American Indian), Métis or Inuk (Inuit). This information is self-reported by persons supervised on intake to correctional services. Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics, Canadian Correctional Services Survey. |

|||

Chart 10 end

With the onset of COVID-19 pandemic in March 2020, the use of bail relative to remand quickly increased going from 3.4 in March 2020 to a peak of 5.3 in June 2020. Much of the increase was due to reduced custody counts as correctional programs and courts shifted away from incarceration and toward community supervision as part of the effort to protect against the spread of COVID-19 in correctional facilities (Statistics Canada, 2021, July 8). In the months following the start of the pandemic, remand counts in the three provinces dropped by more than 30%, while bail counts increased by around 10%, contributing to this rapid change in the ratio.

After the initial months of COVID-19, the bail to remand ADC ratio began to decrease as remand counts began to gradually increase and bail counts moderated, driven mostly by large decreases in the bail ADC in Alberta. By March 2021, the ratio was 3.5, roughly the same level seen during the period prior to COVID-19. Although the ratio in March 2021 reflected pre-implementation levels, there were fewer persons on bail and remand. Compared to April 2019, the first month in the reference period, the bail ADC in March 2021 was 15,580 (down 14%) and the remand ADC was about 4,475 (a decrease of 15%).

The change in bail and remand counts from pre-COVID-19 (April 2019 to March 2020) to post-COVID-19 (April 2020 to March 2021) varied greatly between the participating provincial correctional programs (Table 6). In Saskatchewan, the ADC rose for both bail and remand. Because bail counts increased more than remand, the ratio in Saskatchewan increased (+25%) to 2.3. In Alberta, there were large decreases in counts of persons in both bail and remand resulting in a 7% increase in the bail to remand ADC ratio in 2020/2021. In British Columbia, there was a slight increase in the bail ADC and a large decrease in remand. Consequently, British Columbia had the largest change in the bail to remand ADC ratio, increasing from 6.5 to 10.3 (+58%).

COVID-19 increased the use of bail more for non-Indigenous persons than Indigenous persons at the start of the pandemic

Early on in the pandemic, as the use of bail relative to remand increased rapidly, the use of bail increased more for non-Indigenous persons. In March 2020, the bail to remand ADC ratio was 4.3 (Chart 10); by June 2020, the month the use of bail relative to remand peaked, the ratio rose to 6.8, an increase of 60%. Conversely, for Indigenous persons, the bail to remand ADC ratio was 2.3 in March 2020. The use of bail also increased in the first few months of 2020/2021, rising to 3.5 in June. However, the use increased by 53%, a slower rate of increase than for non-Indigenous persons. The early difference in the use of bail, however, diminished throughout the rest of the year. By March 2021, the bail to remand ADC ratio was nearly identical to the ratios in March 2020.

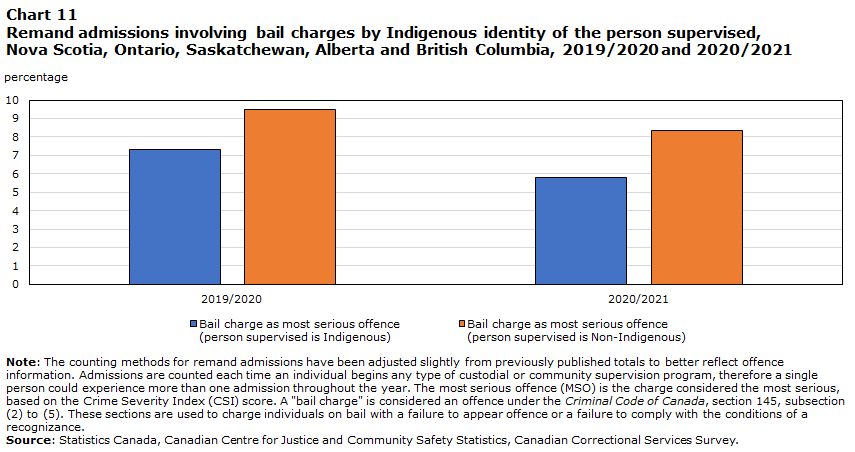

“Bail charges” were the most serious offence in almost one tenth of remand admissions

This next section focuses on remand admissions involving a “bail charge” to better understand the extent of non-compliance with bail that results in remanding individuals. Admissions are counted each time an individual begins any type of custodial or community supervision program, therefore a single person could experience more than one admission throughout the year. Data on remand admissions are available from five reporting provinces for this analysis, Nova Scotia, Ontario, Saskatchewan, Alberta, and British Columbia.

The term “bail charge” is used when an individual fails to comply with a bail order or fails to appear in court. Individuals on bail are charged either with a failure to appear offence or a failure to comply with the conditions of a recognizanceNote .

In total, there were around 59,500 remand admissions in the five correctional programs in 2020/2021. In about 8% of these remand admissions, the most serious offence (MSO) was a “bail charge”, where the MSO is the charge considered the most serious based on the Crime Severity Index (CSI) score (Chart 11). Since “bail charges” typically are considered less serious by the CSI scoring, if a “bail charge” is an MSO, it’s usually the only offence related to the admission. The proportion of admissions where a “bail charge” was the MSO varied between provinces, with Nova Scotia having the highest proportion (15% of remand admissions) and Saskatchewan the lowest (3%) (Table 7).

Chart 11 start

Data table for Chart 11

| Bail charge as most serious offence (person supervised is Indigenous) | Bail charge as most serious offence (person supervised is Non-Indigenous) | |

|---|---|---|

| percentage | ||

| 2019/2020 | 7.3 | 9.5 |

| 2020/2021 | 5.8 | 8.3 |

|

Note: The counting methods for remand admissions have been adjusted slightly from previously published totals to better reflect offence information. Admissions are counted each time an individual begins any type of custodial or community supervision program, therefore a single person could experience more than one admission throughout the year. The most serious offence (MSO) is the charge considered the most serious, based on the Crime Severity Index (CSI) score. A "bail charge" is considered an offence under the Criminal Code of Canada, section 145, subsection (2) to (5). These sections are used to charge individuals on bail with a failure to appear offence or a failure to comply with the conditions of a recognizance. Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics, Canadian Correctional Services Survey. |

||

Chart 11 end

There was little change in the proportion of remand admissions where the MSO was a ‘bail change’. In 2019/2020, about 9% of admissions had an MSO as a bail charge, although the actual number of remand admissions pre COVID-19 were considerably higher.

Most serious offence of remand admissions involving an Indigenous person are less likely to involve a “bail charge”

In the five-reporting provincial correctional programs, the proportion of admissions where the MSO was a “bail charge” was higher for non-Indigenous persons than Indigenous persons. In 2020/2021 about 8% of remand admissions of non-Indigenous accused were for a “bail charge”, compared to 6% of remand admissions of Indigenous persons (Chart 11).

Summary

As a result of the consequences of colonization, individual and systemic racism and other important factors, many Indigenous persons and communities continue to struggle with intergenerational trauma in addition to challenging social, economic and health conditions – which may be related to offending and victimization (Perreault, 2022).

Through the unveiling in this Juristat article of three new population-based corrections indicators (i.e. Incarceration Rate, Over-Representation Index, and Custodial Involvement Rate), it has been shown that the over-representation of Indigenous persons in correctional facilities and systems continues to be a significant and pressing issue in the five provinces.

Using the Over-Representation Index, which controls for age and sex differences between populations, the incarceration rate of Indigenous persons was about 9 times higher than the rate for non-Indigenous persons in 2020/2021. Indigenous populations, particularly young adult Indigenous men, experienced custody at a greater rate than non-Indigenous populations. With respect to the use of bail and remand, overall, bail is used more frequently for non-Indigenous populations than for Indigenous population, relative to the size of their remand populations

This article has also demonstrated the importance of and need for disaggregated data. It is hoped that the data, insights, and analyses contained herein will promote further discussion and a better understanding and awareness of the over-representation of Indigenous persons in corrections. It is important that decision-makers, criminal justice practitioners, Indigenous organizations and communities, researchers, and the public have access to accurate, reliable, relevant and timely data and information to help effectively address this serious and long-standing problem.

It is the intention of Statistics Canada to take this inaugural work and develop annual, national indicators of over-representation and correctional involvement to track trends and patterns over time, and future research will integrate federal corrections data with the information collected from provincial correctional programs. Through further indicator development and data analysis, we can all gain a better understanding of the experiences of Indigenous and racialized populations regarding their interactions with, and involvement in, correctional systems across Canada.

Detailed data tables

Table 1 Indigenous incarceration rates, by sex, select provinces, 2020/2021

Table 2 Non-Indigenous incarceration rates, by sex, select provinces, 2020/2021

Table 6 Ratio of bail to remand average daily counts, by fiscal year

Survey description

Canadian Correctional Services Survey

The Canadian Correctional Services Survey (CCSS) is conducted by the Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics (CCJCSS) at Statistics Canada. The CCSS is an administrative microdata survey that collects data from correctional services programs in Canada. The survey collects data on the characteristics of persons being supervised, their legal hold status while in correctional services, offences and conditions related to the various court orders, events related to the person that occur during the period of supervision, and results of any needs assessments done on persons while in correctional services. The CCSS is a census survey based on electronically extracted microdata that is conducted annually. The CCSS data requirements were developed with the assistance of representatives from correctional service programs in Canada and other federal and provincial government departments responsible for the administration of justice. The implementation of the CCSS is still under development in certain jurisdictions. The provinces currently reporting to the CCSS include Newfoundland and Labrador (youth corrections), Nova Scotia, Ontario (adult corrections), Saskatchewan, Alberta, and British Columbia.

Quality evaluation of Indigenous identity data collected by correctional services

The implementation of the Canadian Correctional Services Survey (CCSS) allows for more opportunities to assess the data quality of information collected by correctional service programs. One such opportunity is to integrate CCSS with other datasets to allow for data confrontation. Data confrontation (comparison of similar data across different datasets) is a main technique used to evaluate administrative data. The expectation is that there is a high degree of consistency between datasets which would indicate reliable data.

A component of this work is called response mobility. Response mobility is a phenomenon by which people provide different responses over time to questions about identity. This can reflect changes in perceptions of identity boundaries (e.g., Census categories) or changes in individuals’ self-identification over time. This technique has been used to better understand Indigenous data collected by the Census (O’Donnell & LaPointe, 2019). Identity correspondence is a different type of response mobility, looking at how identification varies across surveys, as opposed to over time (although response mobility could impact identify correspondence if information was collected at different points in time).

The Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics (CCJCSS) recently started the CCSS-Census of Population data confrontation project to compare Indigenous identity responses provided to correctional service programs to responses on the Census of Population. The main objective of the project was to flag if there were large inconsistencies between the CCSS and the Census in the reporting of Indigenous identity, which may indicate reliability concerns with the corrections dataset.

For this study, we limited the analysis to all persons incarcerated in 2019/2020 and 2020/2021 in the 5 correctional programs and compared responses with the 2016 Census of Population and the 2011 National Household Survey for individuals found in both the corrections dataset and the Census datasets. About 15% of the CCSS records were matched to the 2016 Census and 12% matched to the 2011 NHS.

Overall, the results of this comparison were very consistent. Of the matched individuals, 95% reported the same identity between the CCSS and the 2016 Census and 96% of the Indigenous identity responses were consistent between the CCSS and the 2011 NHS. In all provinces, most individuals reported consistently across datasets. In comparing the CCSS to the 2016 Census, Saskatchewan having the highest correspondence rate (97%) and Nova Scotia the lowest (93%) (Table 8).

The preliminary conclusions we can draw from the matched correctional population in the CCSS-Census data confrontation is that Indigenous identity responses are highly consistent between to the two datasets, indicating good data quality at least for the proportion of the CCSS dataset that matched to Census data. CCJCSS and Statistics Canada will continue to evaluate these data to assess data quality of both the matched and unmatched CCSS population, as well as potential for under-reporting Indigenous or non-Indigenous correctional populations.

Background, new indicators of over-representation

Incarceration Rates: measures the proportion of a population in custody on an average day in the year. When examined over a period of time, incarceration rates can provide a measure of prison population growth or decline relative to the overall Canadian population. As such it is an important measure to track when looking at the over-representation of the Indigenous population. It is calculated by taking the Average Daily Count (ADC) of the correctional population, dividing it by the general population estimate for that same year, then multiplying by 10,000. For the Canadian Correctional Services Survey (CCSS), the rate is expressed as the number of incarcerated persons per 10,000 population. For example, a rate of 100 for Canada means that, on an average day in the year, 1% of the population in Canada was incarcerated (see Evolution of average daily count data collection at the Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics).

Through the CCSS, the ADC is now available by Indigenous and racialized groups allowing Statistics Canada to produce both Indigenous and non-Indigenous incarceration rates for the population as a whole, or apply intersectionality to the rates (e.g., focus on adult men, adult women, youth between the ages of 12 and 17, etc.).Note Over-representation (e.g., of Indigenous persons) would be measured by the relative difference between the Indigenous and non-Indigenous Incarceration Rates.

Over-Representation Index: With new data on incarceration rates, over-representation can now be measured by calculating the relative difference between Indigenous and non-Indigenous incarceration rates for the same population. One issue with this approach, however, is that Indigenous populations are younger (Statistics Canada, 2022, Sept 21), and younger populations are more likely to be involved in the criminal justice system (Allen & Superle, 2016). Thus, some of the relative difference between Indigenous and non-Indigenous incarceration rates in adult custody is attributable to demographic differences in population and not just differences in rates of incarceration.

To address this limitation, Statistics Canada developed the Over-Representation Index. For a province or territory where the Indigenous population is younger, we could see a lower score on the Over-Representation Index than the actual relative differences between the Indigenous and non-Indigenous incarceration rates. Likewise, over time, as population profiles change for a province or territory, the Over-Representation Index controls for these changes, reducing the impact demographic shifts may have on the over-representation trends. Moving forward, it is the intention of Statistics Canada to develop the Over-Representation Index as its official measure of over-representation in corrections for Indigenous and racialized populations once coverage increases with the CCSS and data from the federal Correctional Service of Canada (CSC) is integrated with provincial data.

Custodial Involvement Rates: The custodial involvement rate is the measure of the proportion of a specific population experiencing custody over a reference period. The measure identifies the number of unique persons spending at least one day in custody during the reference period for a defined population (Indigenous, Black, young men, etc.), then calculates the percentage of the population experiencing incarceration. Individuals are counted equally, whether or not they spent one night in custody or the whole year.

While incarceration rates and custodial involvement rates are both population-based indicators, they have some notable differences. For instance, incarceration rates are based on both involvement in custody and length of supervision, whereas custodial involvement rates measure only involvement (as length of stay is not calculated as part of the indicator). Incarceration rate is considered a better indicator for measuring over-representation because it includes more elements of incarceration (i.e. involvement and length of stay). However, it may leave the perception that only a small number of persons go through custodial systems because it is based on a daily count. In contrast, the custodial involvement rate captures the total number of persons experiencing incarceration over a period of time, and as such helps us to understand what the true number of individuals who enter the correctional system are.

Evolution of average daily count data collection at the Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics

Average daily count (ADC) of persons supervised over the course of a reference fiscal year has been published by the Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics (CCJCSS) for a number of years, through another survey of correctional programs called the Key Indicators Report (KIR). The KIR is an aggregate survey, meaning CCJCSS only collects counts and has no ability to breakdown counts further than what is provided in the survey (type of legal status and sex). Furthermore, as the source for KIR is often head count data or warehoused aggregate counts, some correctional programs themselves have difficulty sub-setting these counts for analysis. Because of the difficulty in breaking down ADC by Indigenous identity, ADC and related indicators have not been used as a measure of overrepresentation, simply because the data has not been available to CCJCSS to do so. In the absence of this information, CCJCSS has focussed solely on admissions data as the sole indicator on overrepresentation.

The Canadian Correctional Services Survey (CCSS) represents a different approach to compiling ADC, through developing the concept of the overnight stay (i.e. an indicator that a person was in a correctional centre at a given time, which we calculate as 11:59pm each day), as the foundation for ADC. As stated above, the overnight stay has not been readily available in correctional systems for CCJCSS to use (although some programs have recently begun developing capacity to store overnight stay data in their information systems). In the CCSS, however, using movement data, logged by correctional staff when persons are moved in and out of correctional centres (intakes, discharges, temporary absences, court movements, escapes and recaptures, unlawfully at large, intermittent sentence movements and internal transfers between correctional centres) the CCJCSS is able to derive the overnight stay as a data record in our system, with the ability to cross-reference the overnight stay with demographic information of the person, such as Indigenous identity.

As the CCSS figures are a derivation, there may be slight inconsistencies between the CCJCSS counts and data published by correctional programs. These are due to rare data integrity issues in the movement data (e.g., an occasional movement may not be picked up by the CCSS) and definitional differences (particularly where persons on certain types of temporary absences should be considered as in-facility or on-register based on supervision requirements outside the correctional centre). The objective of CCJCSS is to produce an ADC figure that is within 1% of the counts produced by the correctional program, and so far, with the jurisdictions reporting to CCSS, differences are below 1%, often well below.

References

Allen, M.K. & Superle, T. (2016). Youth crime in Canada, 2014. Retrieved October 13, 2022.

Clark, S. (2019). Overrepresentation of Indigenous People in the Canadian Criminal Justice System: Causes and Responses. Research and Statistics Division, Department of Justice Canada.

Government of Ontario. (2018). Anti-Racism Data Standards – Order in council 897/2018. Retrieved September 26, 2022.

Justice Canada. (2022). Understanding the Overrepresentation of Indigenous People in the Criminal Justice System. State of the Criminal Justice System Dashboard. Retrieved September 26, 2022.

Justice Canada. (2021). Charter Statement – Bill C-75: An Act to Amend the Criminal Code, Youth Criminal Justice Act and other Acts and to make consequential amendment to other Acts. Justice Canada. Retrieved October 13, 2022.

Justice Canada. (2019). Legislative Background: An Act to amend the Criminal Code, the Youth Criminal Justice Act and other Acts and to make consequential amendments to other Acts, as enacted (Bill C-75) in the 42nd Parliament. Justice Canada. Retrieved September 26, 2022.

Library of Parliament. (2019). Legislative Summary of Bill C-75: An Act to amend the Criminal Code, the Youth Criminal Justice Act and other Acts and to make consequential amendments to other Acts. Library of Parliament. Retrieved September 26, 2022.

Moreau, G. (2022). Police-reported crime statistics in Canada, 2021. Juristat. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 85-002-X.

O’Donnell, V. & LaPointe, R. (2019). Response mobility and the growth of the Aboriginal identity population, 2006-2011 and 2011-2016. National Household Survey: Aboriginal Peoples. Statistics Canada. Retrieved September 26, 2022.

Office of the Correctional Investigator. (2021, December 17). Proportion of Indigenous Women in Federal Custody Nears 50%: Correctional Investigator Issues Statement. News Release. Retrieved September 26, 2022.

Office of the Correctional Investigator. (2020, January 21). Indigenous People in Federal Custody Surpasses 30%: Correctional Investigator Issues Statement and Challenge. News Release. Retrieved September 26, 2022.

Perreault, S. (2020). Victimization of First Nations people, Métis and Inuit in Canada. Juristat. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 85-002-X.

R. v. Ipeelee, 2012 SCC 13 (CanLII), [2012] 1 SCR 433.

R. v. Gladue, 1999 CanLII 679 (SCC), [1999] 1 SCR 688.

Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples (RCAP). (1996). The Report of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples. Canada Communication Group.

Statistics Canada. (2022, April 20). Adult and youth correctional statistics, 2020/2021. (The Daily).

Statistics Canada. (2022, September 21). Indigenous population continues to grow and is much younger than the non-Indigenous population, although the pace of growth has slowed. (The Daily).

Statistics Canada. (2022). Table 35-10-0154-01. Average counts of adults in provincial and territorial correctional programs [Data table]. Retrieved September 26, 2022.

Statistics Canada. (2021, July 8). After an unprecedented decline early in the pandemic, the number of adults in custody rose steadily over the summer and fell again in December 2020. (The Daily).

Statistics Canada. (2019). Diversity of the Black population in Canada: An overview. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 89-657-X2019002.

Statistics Canada. (2016, July 20). Measuring crime in Canada: A detailed look at the Crime Severity Index. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 11-629-x.

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. (2015a). Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada: Calls to Action.

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. (2015b). Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) Website.

- Date modified: