Projections of the Indigenous populations and households in Canada, 2016 to 2041: Overview of data sources, methods, assumptions and scenarios

Skip to text

Text begins

Acknowledgments

This report is the work of the Demosim team. The following are or were members of the Demosim team during the development of the versions of the model based on the 2016 Census: Arnaud Bouchard-Santerre, Patrice Dion, Stéphanie Langlois, Anne Milan, Jean-Dominique Morency, David Pelletier, Elham Sirag, Stéphanie Tudorovsky, Gabriel Vesco and Samuel Vézina of the Centre for Demography; Dominic Grenier, Chantal Grondin and Amélie Lévesque of the Statistical Integration Methods Division.

For the development of this version of Demosim, funding was received from Statistics Canada and two external partners: Indigenous Services Canada (ISC) and Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC). Representatives of these departments were consulted at different stages, through an interdepartmental working group and an interdepartmental steering committee.

The Demosim team would like to thank especially the authors of the two previous versions of the Demosim technical report: Éric Caron-Malenfant, Simon Coulombe and Dominic Grenier. Large sections of these two previous versions of the technical report were directly incorporated into this updated version.

Thanks to Carol D’Aoust, for his technical support in preparing this report. Thanks also to Laurent Martel who reviewed a preliminary version of this document.

Introduction

For a third consecutive cycle, Indigenous Services Canada (ISC) has mandated Statistics Canada’s microsimulation population projection team to update projections of the IndigenousNote populations and households in Canada. For this new projection cycle, the objective is to produce prospective data for the period from 2016 to 2041, taking into account the most recent data sources, chief among which is the 2016 Census.

This new cycle of Indigenous populations projections differs from previous ones in several respects. First, much effort was put into improving parameter specification, integrating information from new data sources, and further validating the models’ functioning and the results. It also differs in that more attention was given to uncertainty in the early years of the projection, because it has been shown that many users of Indigenous projections used them for data needs over a very short horizon. In previous cycles, the choice of assumptions was essentially guided by long-term considerations. It did not explicitly aim to take into account the possible—sometimes significant—fluctuations that could occur in the short term for some components.

It further differs in the choice of dissemination products. In the previous cycle, two reports related to the projections of the Indigenous populations and households were made public: (1) an analytical report (Statistics Canada 2015-1) that described the projection assumptions and scenarios, as well as the main projection results, and (2) a technical report (Statistics Canada 2015-2) that provided an overview of how Demosim, the projection model used to produce these projections, generally works, its base population, and the data sources and methods related to each of its components. For this projection cycle, it will now be possible to extract, free of charge, the results of the projections of the Indigenous populations and households from the data tables available on the Statistics Canada website. In addition, an interactive data visualization tool and infographics will be made available to users. These various products (see Box 1) will replace the analytical report that was disseminated in the past.

Start of text box 1

Box 1. Dissemination products for results of Indigenous projections

Analysts and researchers interested in obtaining results from the current projections of the Indigenous populations and households are invited to consult the following products available to the public free of charge:

The Daily

The Daily is Statistics Canada’s official release bulletin. A special article in The Daily was published the day the projections of the Indigenous populations and households were disseminated. This article provides a brief description of the main projection results (Statistics Canada 2021-1).

Infographics

Five infographics were developed, one for each of the following population groups:

Each infographic presents results based on a selection of indicators at the 2041 horizon. These infographics are available on the Statistics Canada website (Statistics Canada 2021-2; 2021-3; 2021-4; 2021-5; 2021-6).

Projected data tables

Two data tables present the projected size of the Indigenous populations. The first table (table 17-10-0144-01: Statistics Canada 2021-9) is broken down using an Indigenous identity classification that gives precedence to Indigenous groups, while the second table (table 17-10-0145-01: Statistics Canada 2021-10) is broken down using an Indigenous identity classification that gives precedence to Registered or Treaty Indian status (see the “Key concepts related to Indigenous populations” section for more details regarding these classifications). In both cases, the projected population figures are broken down by age group, sex, region of residence, provinces and territories, and projection scenario for years 2016 to 2041. These tables are available on the Statistics Canada website and can be consulted using the following links: table 17-10-0144-01 and table 17-10-0145-01.

Interactive data visualization tool (dashboard)

An interactive data visualization tool, also available on the Statistics Canada website, can also be used to explore projection results regarding Indigenous populations in a dynamic manner. The base data for this tool are those from the two CODR tables (Statistics Canada 2021-11).

Data produced on demand

For users of data from the projections of the Indigenous populations and households who are unable to find the data that would be useful to them in the products presented above, it is possible to request custom data by contacting customer service at the Centre for Demography (statcan.demography-demographie.statcan@statcan.gc.ca). Custom tables are prepared using a cost recovery approach.

End of text box 1

Lastly, it is appropriate to mention that at the time of making these projections, the COVID-19 pandemic has occurred and is likely to have impacts on the demographic evolution of Indigenous populations in the coming years, impacts that are hard to predict at the time of writing given the recent nature of the pandemic. Readers are invited to see Box 4 in the “Cautionary notes” section for more information about this matter.

Base population

Projected characteristics

The base population for the version of Demosim used to prepare projections of the Indigenous populations and households is essentially derived from the 25% sample microdata file from the 2016 Canadian Census of Population,Note a database comprising 8.6 million records representative of the Canadian population living in private households on May 10, 2016. The main variables of the base population are as follows:Note

- Age;

- Sex;

- Indigenous group;

- Registered or Treaty Indian status;

- Registration category on the Indian Register (6[1] or 6[2]);

- Marital status;

- Place of birth (province/territory or country/world region);

- Immigrant status and time elapsed since immigration;

- Generation status;

- Immigrant admission category;

- Canadian citizenship;

- Visible minority group;

- Mother tongue;

- Language spoken most often at home;

- Knowledge of official languages;

- Education level (secondary [high] school diploma or equivalency certificate).Note

Registration category on the Indian Register is a variable that was added through file linkages, as it was not included in the 2016 Census database. Registration category, which defines the conditions for children to inherit Registered or Treaty Indian status from their parents, was obtained from pre-existing linkages between the Indian Register and the 2016 Census, to identify, among census respondents who reported being Registered or Treaty Indians, those who had status under subsection 6(1) of the Indian Act and those who had status under subsection 6(2).Note In 85% of cases, registration category was determined through file linkages. For the remaining 15%, categories 6(1) and 6(2) were either deterministically imputed using information on the registration of other census family members, or else were imputed using a probabilistic model (logistic regression).Note

Geographic infrastructure in Demosim

In addition to the characteristics listed above, Demosim also has a geographical infrastructure made up of 85 geographic regions. Among these 85 regions, there are 52 main regions. The main regions include all 35 Canadian census metropolitan areas (CMA) identified in the 2016 Census, the non-CMA part of each province, and the three territories. Some of these regions are further divided into sub-regions that are also part of the main regions: the Montréal CMA is divided into Montréal Island and the rest of the CMA; the Ottawa–Gatineau CMA is divided into its Ontario part and its Quebec part; and the non-CMA parts of New Brunswick and of Ontario are each divided into a part with a concentration of Francophones and a non-francophone part (see Caron-Malenfant [2015] for a map of these regions in New Brunswick and Ontario).

Of the main regions, 31 include at least one reserve. For these 31 regions, we distinguish an on-reserve and an off-reserve part. These 31 regions are non-CMA Newfoundland and Labrador, Prince Edward Island, Halifax, non-CMA Nova Scotia, Moncton, non-CMA francophone New Brunswick, non-CMA anglophone New Brunswick, Québec, Trois-Rivières, the part of the Montréal CMA outside the island of Montréal, non-CMA Quebec, Peterborough, Toronto, Brantford, Greater Sudbury, Thunder Bay, non-CMA francophone Ontario, non-CMA anglophone Ontario, Winnipeg, non-CMA Manitoba, Saskatoon, non-CMA Saskatchewan, Calgary, Edmonton, non-CMA Alberta, Kelowna, Vancouver, Victoria, Abbotsford–Mission, non-CMA British Columbia, and the Northwest Territories.

Likewise, three main regions (excluding Nunavut, all of which is included inside Inuit Nunangat) include portion of the Inuit homelands. For these three regions, we distinguish one part inside and one part outside Inuit Nunangat. The four regions of Inuit Nunangat are (1) Nunatsiavut (located in the non-CMA region of Newfoundland and Labrador), (2) Nunavik (located in the non-CMA region of Quebec), (3) Nunavut territory, and (4) the Inuvialuit region (located in the Northwest Territories).

Adjustments made to the 2016 Census microdata file

Some adjustments were made to the 2016 Census microdata file so that the Demosim base population reflects the entire Canadian population as closely as possible.

The population living on the 14 Indian reserves or Indian settlements that were incompletely enumerated in the 2016 Census were added to the Demosim base population. It was assumed that the population was consistent with estimates produced by the Statistical Integration Methods Division (SIMD) of Statistics Canada. Records were then imputed with characteristics that were representative of similarly sized reserves enumerated in the same province.

Adjustments were then made to obtain a population that was representative of the population estimates of May 10, 2016, which includes people living in institutions and in collective dwellings and accounts for the net undercoverage in the census. The adjustment for institutions and collective dwellings involved multiplying the sampling weights of individuals by the ratio of the 2016 short-form Census estimated population (which includes institutions and collective dwellings) to the 2016 long-form Census estimated population by age, sex and place of residence.Note

Lastly, correction factors were applied to sampling weights to take into account census net undercoverage of the population. An adjustment was first made by age, sex, and place of residence for the population living off Indian reserves for both Indigenous and non-Indigenous people. The approach assumes that Indigenous and non-Indigenous people are equally undercovered in the regions in question, an assumption that cannot be disproved because the data on undercoverage are not broken down by Indigenous identity.

Moreover, an additional adjustment was also applied to the weights of males with Registered or Treaty Indian status aged 15 to 54 years living off reserve. This adjustment was warranted given that the sex ratios of Registered or Treaty Indians decline when they are in their twenties, according to 2016 Census data (long-form questionnaire), a decline that can hardly be attributed to purely demographic processes. In fact, this decline instead appears to be because of the overrepresentation of men among the institutionalized population, outside of the long-form census questionnaire universe, and among the population with no fixed address, who are difficult to enumerate (see Akee and Feir, 2018). The adjustments made to the 2016 Census weights to account for the institutionalized population and for the net census undercoverage described above do very little to reduce the decline in sex ratios because they do not specifically take Indigenous identity into account. To remedy this situation, weights of males with Registered or Treaty Indian status have been adjusted to reflect the estimated sex ratios of Indian Register data, under the assumption that they are more realistic. In fact, despite some shortcomings, such as the occasional late registration of births and deaths, and incomplete updating of information on individuals’ place of residence, the Indian Register has the advantage of being little affected by undercoverage. Furthermore, it must be noted that similar declines in sex ratios are also observable among First Nations people without Registered or Treaty Indian status and Métis without Registered or Treaty Indian status, but no additional adjustments could be made because of a lack of reliable alternative data.

For the on-reserve population, adjustments for net undercoverage are made differently for the Registered or Treaty Indian population and the population without Registered or Treaty Indian status. For the population without Registered or Treaty Indian status, the same net census undercoverage rates are applied by age, sex and place of residence as they are for the off-reserve population. For the Registered or Treaty Indian population, the net census undercoverage rate for reserves in Canada is applied. The distribution of the net census undercoverage of Registered or Treaty Indians by age, sex and place of residence is assumed to be proportional to the gaps in the observed population (by age, sex and place of residence) between the Indian Register and the census for the on-reserve population.Note

All of these adjustments increased the total population by about 1.6 million people. These adjustments had a greater impact on some population groups—notably young adults, who had higher net undercoverage rates, and Registered or Treaty Indians, because of the adjustment for incompletely enumerated reserves.Note

Demosim’s general functions and features

These new projections of the Indigenous populations were produced using Demosim, Statistics Canada’s microsimulation population projection model.

Demosim projects individuals in the population one by one, rather than projecting the population on the basis of aggregate data, as is done with cohort-component and multistate models.Note Demosim simulates the life of each person in its base population, as well as that of the newborns and immigrants who are added to the population during the simulation.Note Individuals advance through time and are subject to the likelihood of “experiencing” various events simulated by the model (for example, the birth of a child, death, a change in education level) until they die, emigrate or reach the end of the simulation.

The probabilities (or risks) of “experiencing” each event depend on the individual’s characteristics. The probabilities are used to derive waiting times, which—being a function of the probabilities associated with the events, individual characteristics and a random process—correspond to the time that will elapse between the present and the occurrence of each event (see Box 2). The event with the shortest waiting time occurs first. After an event occurs, a new set of waiting times are calculated for the events that depend on the characteristic that has changed; the individual then advances through time to the next event (again, the one with the shortest waiting time), and so on. Since Demosim is a continuous-time model, the various simulated events may occur at any time of the year, although some of them occur on a fixed date (for example, birthdays). As well, some characteristics are imputed annually to the individuals. Events and waiting times are managed using the computer language Modgen,Note in which Demosim is programmed.

This approach is used to yield projections at a level of detail that is not possible using standard models because of their matrix nature. The simultaneous and consistent projection of a large number of variables made possible through microsimulation permits the use of more characteristics, both as determinants of simulated events and for tabulating results. Demosim has also shown flexibility in formulating assumptions and projection scenarios, as well as an ability to reproduce the results of cohort-component models at an aggregate level.Note

The use of this method assumes that the probabilities (or risks) associated with simulated events have been calculated in advance. Calculations are done using existing data sources (censuses, surveys, administrative data and database linkages) to which various methods are applied. The next section describes these methods in more detail.

Start of text box 2

Box 2. On calculating waiting times, as well as the concepts of transition rate (risk) and probability

In a continuous-time model like Demosim, events can occur at any time. Their occurrence depends on waiting times, which are associated with each individual based on his or her present characteristics. The individual-level waiting times required to run a microsimulation model like Demosim cannot be obtained from observation data; they must be derived.

Waiting times are derived from the transition rate (which quantifies the risk) denoted by λ. The transition rate is defined by the number of events observed divided by the number of person-years lived. An example of a transition rate in demography is the mortality rate (mx), found in mortality tables alongside the death probability (qx), which represents the probability that a person will die during the year.

The waiting time before an event occurs follows an exponential distribution of parameter λ. Under this exponential law, it is assumed that the risk of experiencing an event (e.g., death) remains constant during a given period of time. The risks in Demosim are thus assumed to be constant, as long as the characteristics that determine the modelled event remain unchanged for the individual. Since most events in Demosim are age-dependent, this period for these events is a maximum of one year.

The probability of an event occurring before or exactly at time t is given by the exponential distribution function: P(T ≤ t) = F(t) = 1- e-λt

The inverse exponential distribution function, t = -ln(1- F(t)) / λ, indicates the time t at which a proportion F(t) of the population will have experienced the event, knowing that the transition rate is λ.

Demosim uses a random process in conjunction with the inverse exponential distribution function to generate individual-level waiting times for each simulated event. First, a random value is obtained from the uniform distribution U[0,1]. This value is inserted into the inverse exponential distribution function in place of F(t). For example, if an event has a transition rate of λ = 0.15 and the random number generated is 0.5, then the waiting time generated for this event will be t = -ln(1- F(t)) / λ = -ln(1- 0.5) / 0.15 = 4.62 years. Any lower random value will give a waiting time below 4.62 years, and any higher value will give a longer waiting time.

The projection parameters often consist of probabilities rather than transition rates. When this is the case, they need to be converted to transition rates by isolating λ in the exponential distribution function to obtain λ = -ln(1- F(t)) / t , and then replacing F(t) with the annual probability and t with 1 year. Therefore, an annual probability of dying of 0.10 has a transition rate of 0.1053 because λ = -ln(1- 0.10) / 1 = 0.1053.

Although the concept of probability is frequently used in this document, it should be noted that the Demosim model actually uses risks to derive waiting times. Furthermore, the term “risk” is used in reference to the more precise concept of transition rate only for the sake of simplicity.

To learn more about calculating waiting times, please consult Willekens (2011).

End of text box 2

Key concepts related to Indigenous populations

Definition and classifications of the Indigenous identity population

The 2016 Census includes four questions related to Indigenous populations, i.e., questions 17, 18, 20 and 21. Question 17 deals with the ethnic or cultural origin of the respondent’s ancestors, and the information collected from this question is not projected in the current projections. Question 18 gives respondents the opportunity to self-identify with one or more Indigenous group(s): First Nations (North American Indian), Métis or Inuk (Inuit). Question 20 asks if the person is a Registered Indian or a Treaty Indian (Status Indian) and Question 21 whether the respondent is a member of a First Nation or an Indian band. The responses to these questions can be combined in various ways to define the Indigenous population (Guimond et al. 2009).

To clarify the language, it is important to distinguish between the categories of Question 18—First Nations (North American Indian), Métis or Inuk (Inuit) —each constituting what will be called here the Indigenous groups, and the Indigenous identity that results from the combination of responses given to Questions 18, 20 and 21 of the 2016 Census. Note , Note To meet the needs of various users, two separate Indigenous identity classifications are used to present the results of the Indigenous population projections, one focusing on Indigenous groups (Question 18) and the other giving precedence to Registered or Treaty Indian status (Question 20).

Indigenous identity, classification that gives precedence to Indigenous groups

- First NationsNote —single identity (respondents self-identifying only with the First Nations group [North American Indians] in response to Question 18);

- Métis—single identity (respondents self-identifying only with the Métis group in response to Question 18);

- InuitNote —single identity (respondents self-identifying only with the Inuit [Inuk] group in response to Question 18);

- other Indigenous people (respondents self-identifying with more than one Indigenous group in response to Question 18, or not self-identifying with any Indigenous group in response to Question 18 but reporting being a Registered or Treaty Indian in response to Question 20 or a member of a First Nation/Indian band in response to Question 21);

- non-Indigenous people (respondents not self-identifying with an Indigenous group in response to Question 18, and not reporting being a Registered or Treaty Indian in response to Question 20 or being a member of a First Nation/Indian band in response to Question 21).

Indigenous identity, classification that gives precedence to Registered or Treaty Indian status

- Registered or Treaty Indians (respondents reporting being a Registered or Treaty Indian [Status Indian] in response to Question 20 of the 2016 Census);

- First Nations—single identity—without Registered or Treaty Indian status (respondents self-identifying only with the First Nations [North American Indian] group in response to Question 18 and not reporting Registered or Treaty Indian status in response to Question 20);

- Métis—single identity—without Registered or Treaty Indian status (respondents self-identifying only with the Métis group in response to Question 18 and not reporting being a Registered or Treaty Indian in response to Question 20);

- Inuit—single identity—without Registered or Treaty Indian status (respondents self-identifying only with the Inuit [Inuk] group in response to Question 18 and not reporting being a Registered or Treaty Indian in response to Question 20);

- other Indigenous people without Registered or Treaty Indian status (respondents: 1) self-identifying with more than one Indigenous group in response to Question 18, or 2) reporting being a member of a First Nation/Indian band in response to Question 21 without reporting being a Registered or Treaty Indian in response to Question 20 or self-identifying with an Indigenous group in response to Question 18);

- non-Indigenous people (respondents not self-identifying with an Indigenous group in response to Question 18, and not reporting being a Registered or Treaty Indian in response to Question 20 or being a member of a First Nation/Indian band in response to Question 21).

These two classifications include exactly the same total number of people with an Indigenous identity. However, the second classification includes the “Registered or Treaty Indian” category, which leads to a corresponding reduction in population for all other Indigenous identities. Table 1 shows the distribution of the Indigenous identity population by the two Indigenous identity classifications.

| Classification that gives precedence to Indigenous groups | Classification that gives precedence to Registered or Treaty Indian status | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Indigenous identity population | Non-Indigenous people | ||||||

| Total - Indigenous identity population | Registered or Treaty Indian | Without Registered or Treaty Indian status | ||||||

| Single identity | Other Indigenous people | |||||||

| First Nations people | Métis | Inuit | ||||||

| thousands | ||||||||

| Total | 36,029 | 1,800 | 910 | 242 | 562 | 67 | 20 | 34,229 |

| Indigenous identity population | 1,800 | 1,800 | 910 | 242 | 562 | 67 | 20 | Note ...: not applicable |

| Single identity | ||||||||

| First Nations people | 1,072 | 1,072 | 830 | 242 | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable |

| Métis | 615 | 615 | 53 | Note ...: not applicable | 562 | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable |

| Inuit | 67 | 67 | 1 | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | 67 | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable |

| Other Indigenous people | 46 | 46 | 26 | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | 20 | Note ...: not applicable |

| Non-Indigenous people | 34,229 | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | 34,229 |

|

... not applicable. Note: The figures are in thousands and are rounded to the nearest thousand. Therefore, the sum of individual categories may not always add up to the total. Source: Statistics Canada, Centre for Demography, Demosim base population. |

||||||||

Registration category on the Indian Register

In this document, a few references will be made, in speaking of Registered or Treaty Indians, to the registration category on the Indian Register, in other words, to category 6(1) and category 6(2) Registered or Treaty Indians. Registration categories 6(1) and 6(2) are designated as such because they correspond to the rules set out in subsections 6(1) and 6(2) of the 1985 Indian Act, which establish the criteria that individuals must meet in order to be entitled to have their names included on the Indian Register. Within the meaning of the Act, people registered under subsection 6(1) differ from those registered under subsection 6(2) with regard to their ability to transmit their status to their children. All children with at least one Indian parent under category 6(1) are entitled to be registered: they are in category 6(1) if the other parent is also registered, and in category 6(2) if not. Children of a category 6(2) registered parent are entitled to be registered only if the other parent is also a Registered or Treaty Indian; children of such unions are in category 6(1).Note It should be added that some people may see their registration category change during the course of their lives. This would represent a case in which the registration category was “amended.”

| Registration category of both parents | Registration category of the child |

|---|---|

| 6(1) with 6(1) | 6(1) |

| 6(1) with 6(2) | 6(1) |

| 6(1) with NS | 6(2) |

| 6(2) with 6(2) | 6(1) |

| 6(2) with NS | NS |

| NS with NS | NS |

|

NS: Non-Status. Source: Statistics Canada, Centre for Demography, information based on the rules in the Indian Act. |

|

Main projected components in Demosim

This section, which aims to document the main components projected by Demosim, is divided into three main parts. The first is concerned with events that are modelled using waiting times, the second discusses characteristics that are imputed annually, and the third gives an overview of how individuals are created during the simulation.

Each of the components projected in Demosim corresponds to a “module,” which includes the computer code specifying the dimensions and functioning of the modelled event, including its relation to other parts of the model and its associated parameters. Table 3 presents the different components of the projection model and summarizes the methods and data sources used in modelling these components.Note

| Components | Data sources | Main methods |

|---|---|---|

| 1) Events with waiting times | ||

| Fertility | - 2016 Census; | - Own-children method; |

| - Canadian Vital Statistics - Birth Database. | - Rates; | |

| - Complementary log-log regressions. | ||

| Mortality | - Canadian Vital Statistics - Death database; | - Modified Li-Lee projection of mortality rates; |

| - 2006 and 2011 Canadian Census Health and Environment Cohorts (CanCHEC). | - Proportional hazards regressions. | |

| Internal migration | - 2001, 2006 and 2016 censuses; | - Complementary log-log regressions; |

| - 2011 National Household Survey (NHS); | - Matrices; | |

| - Data linkage between the 2011 and 2016 censuses; | - Rates. | |

| - Data linkage between the 2006 and 2011 censuses. | ||

| Emigration | - Demographic estimates; | - Rates; |

| - Longitudinal Administrative Databank (LAD) linked with the Longitudinal Immigration Database (IMDB). | - Proportional hazards regressions. | |

| Registration on the Indian Register and registration category amendment over an individual’s lifetime | - Indian Register; | - Registration and category amendment rates with predetermined targets. |

| - Linkages between the Indian Register and the 2016 Census. | ||

| Intragenerational ethnic mobility of Indigenous people | - 1996, 2001, 2006 and 2016 censuses; | - Residual method. |

| - 2011 National Household Survey (NHS). | ||

| Change in level of education | - 2001 General Social Survey; | - Logistic regressions; |

| - 2016 Census. | - Alignment methods. | |

| 2) Characteristics imputed annually | ||

| Marital status | - 2016 Census; | - Logistic regressions. |

| - 2011 National Household Survey (NHS); | ||

| - Linkages between the Indian Register and the 2016 Census. | ||

| Head of household and head of family | - 2016 Census. | - Headship rates. |

| Labour force participation | - Labour Force Survey; | - Participation rates; |

| - 2016 Census; | - Logistic regressions. | |

| - 2011 National Household Survey (NHS). | ||

| 3) Creation of individuals during the simulation | ||

| Creation of newborns | - 2016 Census; | - Deterministic imputation; |

| - 2011 National Household Survey (NHS); | - Matrices; | |

| - Linkages between the Indian Register and the 2016 Census. | - Multinomial regressions. | |

| Immigration | - 2016 Census; | - Imputation; |

| - Data from Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada. | - Distributions. | |

| Non-permanent residents | - 2016 Census; | - Imputation; |

| - Data from Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada. | - Distributions. | |

| Source: Statistics Canada, Centre for Demography. | ||

Events with waiting times

The first category of events contains those events that are modelled using waiting times (see Box 2). These events make it possible to create a dynamic and distinct life course for each simulated individual. Events in this category are fertility, mortality, internal migration, emigration, registration on the Indian Register and registration category amendment over an individual’s lifetime, intragenerational ethnic mobility of Indigenous people and changes in education level.

Fertility

The fertility module was designed to obtain a projection of births that reflects fertility differences between the various groups projected such as Indigenous people or immigrants. On the one hand, it includes “base probabilities” of giving birth by age, number of children at home, and having or not having an Indigenous identity. Calculated using the own-children methodNote applied to the 2016 Census data, they represent the probability of having given birth to at least one child during the year preceding census day.Note Base probabilities are adjusted to take into account children not living with their mother and deaths that may have occurred during the year, and calibrated to correspond to the estimated number of births according to data from the Canadian Vital Statistics - Birth database.

The base probabilities are then combined with the results of complementary log-log regressions (see Box 3) computed using the same 2016 Census data to which the own-children method was applied. The regressions aim to estimate the probability—for various combinations of age group, number of children in the home and Indigenous identityNote —of having given birth to one or more children during the same period according to other variables. These variables are marital status, education level, Indigenous group, Registered or Treaty Indian status and registration category on the Indian Register, immigrant status, time elapsed since immigration, generation status, immigrant admission category, place of birth, visible minority group, mother tongue and detailed place of residence (on or off Indian reserves, inside or outside Inuit Nunangat, in or outside a CMA, and province and territory in regression models for the Indigenous identity population and CMA of residence only in regression models for the non-Indigenous population).Note For the sake of consistency between base probabilities and regressions results, both estimate the number of women having given birth to one or more children, and not the total number of births (since multiple births are possible). To obtain the total number of births, an adjustment consisting of ratios between the number of births during the period and the number of women who have given birth, by Indigenous identity or visible minority group, is applied.

Start of text box 3

Box 3. Combining base rates or probabilities with regression results

In a number of Demosim modules, the likelihood of certain events is estimated using base rates combined with relative factors derived from results of regressions. Combining base rates and regression results increases the flexibility for developing projection assumptions and makes it possible to incorporate information from various data sources for event modelling. However, some difficulties are associated with it.

First, the reference category of regression models is normally not the entire population, but only one or more subgroups. A conversion or adjustment is therefore required if the results of such regressions are to be combined with one or more rates that refer to the entire population.

A second difficulty lies in differences between the composition of the population used to calculate the regression models and the composition of the population to which these regression results are applied, that is the base population for the projection. When a data source other than the Demosim base population is required to calculate parameters, the weighted sum of probabilities from the regression will not necessarily be equal to the sum that would be obtained by weighting these same probabilities using the population from another data source.

To address these difficulties, a calibration method is used to adjust the y-coordinate at the origin of the regression models without changing the model’s other coefficients. This adjustment is made in such a way as to reproduce target rates (base rates) within a population whose composition is the same as the composition of the Demosim base population.

To illustrate the method, let us suppose that we performed a logistic regression estimating the probability than an event Y will occur according to a set of characteristics X. This regression was carried out on a survey that we will call source A. This data source A has a population whose composition according to the X characteristics differs from the composition of the Demosim base population, to which, however, the probabilities from source A will be applied. We will call the Demosim base population data source B. Let us suppose that we also want to assume that the probability that the event in question will occur reaches a pre-established target, as is often the case when making projections.

Keep in mind that with a logistic regression, the probability PA (with A referring here to data source A) that event Y will occur given the set of characteristics X ( ) is calculated using the following formula:

If we weight the probabilities using weights derived from data source A ( ), the overall probability (or the mean probability in the population) that event Y will occur is

If we apply the probabilities resulting from this regression to another data source—say, source B—andwe weight it based on the composition of this source (with weights ), we will produce an overall probability of event Y occurring that will not be equal to either the one that we would obtain using only source A, or the one that that we could have obtained using only source B.

Let us now suppose that we want to find an adjustment to reproduce the overall probability for source A or source B. Since the result of the above equation gives the overall probability neither for source A nor for source B, it would not be sufficient to multiply it by the quotient of the two ( or the inverse).

The adjustment that we use for this purpose consists in using an iterative method to find an that we add to the ordinate at the origin so that

where .

This method, while used in the above example to reach a target such as the overall probability for source A or source B, can also be generalized to any target. In Demosim, to modify the assumption by changing the base rates (the target to be reached), a new adjustment specific to the desired target can simply be calculated. This type of adjustment can also be adapted to other types of regressions.

This method of calibrating the model makes it possible to preserve the odds ratios of the regression model while accurately reaching the target, assuming a population whose composition does not change from the start of the projection. Therefore, this method makes it possible to maintain compositional effects that may arise during the projection. As well, since the target set by the base rates is reached by adjusting the y-coordinate at the origin of the regressions, it limits the probabilities to no more than 100%, regardless of target. That also means that relative differences are maintained during the projection in terms of odds ratios (for logistic regression) or risk ratios (for proportional risk regression).

End of text box 3

Mortality

The mortality module has a similar structure to the fertility module, as it also uses base rates combined with relative mortality risks obtained through regressions models (see Box 3). The mortality module aims to simulate the future number of deaths, taking into account the differences between the projected groups. Owing to the lack of a single, comprehensive source of data, in Demosim’s previous projections of the Indigenous populations (Statistics Canada, 2015-1), relative mortality risks for the Indigenous groups (First Nations people, Métis, and Inuit) were modeled using a combination of both different data sources and methodology. The methods used this cycle, however, are consistent across all demographic groups. This is attributable to the use of the 2006 and 2011 Canadian Census Health and Environment Cohorts (CanCHECs)Note as the sole data source in the computation of relative risks. These CanCHECs were used to follow-up on a five-year period following the census date.

The CanCHECs are probabilistically-linked datasets that combine information from the long-form censuses or the National Household Survey (NHS) with death data from the Canadian Vital Statistics Death Database (CVSD). Beginning with the 2006 CanCHEC, the age criteria for inclusion in the cohort was extended from only those aged 19 or older to all individuals aged 0 or older on census day, allowing the computation of mortality parameters for all relevant ages within Demosim.Note

The base rates consist of projected age- and sex-specific mortality rates obtained from the most recent national population projections (Statistics Canada, 2019-2). For individuals aged 0 to 90, the base rates are combined with the results of proportional hazards regressions (Cox models) calculated from the CanCHEC data, stratified by sex. These regressions estimate the relative risk of death by various characteristics: Indigenous group, Registered or Treaty Indian status, residence on or off reserve, residence in an Inuit region, visible minority group, time elapsed since immigration, education level, region of residence, Note and age group.

The models were not stratified by age group, and instead included interactions between certain variables and age in order to account for potential differences in their impact on mortality outcomes. For individuals aged 91 and above, no relative risks were applied to the base rates. Results of regression models fit to these ages demonstrated little to no relationship between selected variables and mortality risks.

Internal migration

The purpose of the internal migration module is to simulate migratory movements among the 85 geographic regions in Demosim, taking into account the main characteristics included in the projection.

Two types of migrations are modelled:

- Interregional migration refers to migration between the 52 main regions of the model;

- Intraregional migration pertains to migration between on- and off-reserve partsNote , or between parts inside and outside Inuit Nunangat within each of the main regions where these distinctions exist.

Modelling internal migration includes several steps. The first steps aim to estimate interregional and intraregional migration based on the relationship between place of residence one year earlier and current place of residence (also known as one-year mobility in the census) contained in a database consisting of the 2001, 2006, and 2016 censuses, and the 2011 NHS, to which a constant geography, based on the geographical limits defined in the 2016 Census, has been applied.Note

Interregional migration modelling is broken down into nine distinct flows that take into account both the place of origin and the destination of migrants. This approach, which involves breaking migration flows into different paths, has the advantage of increasing flexibility when implementing assumptions. For example, it becomes easy to set specific migration levels to and from Indian reserves.

Here is a summary of these nine flows:

- migration from an off-reserve region outside Inuit Nunangat (ORROIN) to another ORROIN;

- migration from an ORROIN to a reserve region (RR);

- migration from an ORROIN to an Inuit Nunangat region (INR);Note

- migration from a RR to an ORROIN;

- migration from a RR to another RR;

- migration from a RR to an INR;

- migration from an INR to an ORROIN;

- migration from an INR to a RR;

- migration from an INR to another INR.

With respect to interregional migration between two ORROINs (by far the most frequent), the probabilities of leaving each of the regions are estimated using complementary log-log regression models based on a large number of individual characteristics: age group, education level, Indigenous group, Registered or Treaty Indian status, immigrant status, time elapsed since immigration, marital status, place of birth, generation status, visible minority group, number of children at home, age of the youngest child at home, mother tongue, language spoken most often at home, and knowledge of official languages.Note

Migrants who leave an ORROIN for another ORROIN are assigned a destination region based on probabilities estimated using a series of logistic regression models and transition matrices. Regression models first determine whether the migrants will settle in a francophone region and, if so, whether they will settle in a predominantly francophone region.Note The models are stratified by immigrant status and by whether the place of residence is in or outside a francophone region, and take into account the same variables used to estimate the probability of leaving a region. The specific destination region is ultimately determined from among the 50 available regionsNote using matrices that take into account the region of origin, place of birth, mother tongue, Indigenous group, Registered or Treaty Indian status, visible minority group and age.

For the other types of interregional migration flows, the probability of leaving a region is calculated from migration rates detailed by Indigenous identity and, when the data allowed it, by age group and education level. Matrices classified by region of origin and, when the data allowed it, by Registered or Treaty Indian status or Indigenous group are then used to determine the specific region of destination among all possible destinations.

Intraregional migration is simulated using migration rates specific to each combination of origin, destination, Indigenous identity, and, when the data allowed it, age group and education level.

Up until now, the calculation of migration parameters used census one-year-mobility data. The next steps involve applying a series of adjustments to the regression model results, migration rates and origin-destination matrices in order to have the migration parameters reflect the net migration observed using the census five-year-mobility variable. The idea is that if the one-year-mobility variable accurately captures the characteristics of migrants that are unlikely to change in the space of a single year, the calibration to the five-year-mobility variable anchors the intensity of migratory movements and their directions on greater numbers and longer periods, which reduces the weight of short-term and singular phenomena that are unlikely to reoccur in the future. The calibration ensures that the contribution of net internal migration to regional population growth reflects the average trends observed over the selected reference periods. Most of the adjustments were calculated using the same database used for the previous steps, based on the relationship observed between the census one-year-mobility and five-year-mobility information.

A recent study that explored the possibility of using linkages between censuses to analyze migration to and from Indian reserves showed that the retrospective information on place of residence five years before the census/NHS had several limitations that could affect the quality of migration flow estimates (Morency et al. 2021). The study also showed that estimates of the size of these flows seemed more adequate when measured from information about the place of residence obtained from two consecutive censuses. For this reason, the calibration of migration rates and origin-destination matrices related to migration to and from reserves based on the five-year-mobility data was carried out using linkages between the 2006 and 2011 short-form censuses and between the 2011 and 2016 short-form censuses.

Emigration

The purpose of the emigration moduleNote is to project net emigration, which is defined according to the components of Statistics Canada’s Demographic Estimates Program (DEP) as the sum of emigration and net temporary emigration, minus return emigration. The emigration module has a similar structure to the fertility and mortality modules, as it combines base rates and regression results (see Box 3) for the population aged 18 and older, making it possible to take into account several characteristics, in particular immigrant status, which is known to be a predisposing factor for emigration.Note For the population aged 18 and older, the base emigration rates were calculated by age and sex at the national level by dividing the net number of emigrants, as estimated by Statistics Canada’s DEP from 2002/2003 to 2011/2012, by the population (excluding non-permanent residentsNote ) from the same source for the same period.Note They are combined with the results of a proportional hazards regression model (Cox model) that uses a linkage between the Longitudinal Administrative Databank and the Longitudinal Immigration Database from 1995 to 2010 to estimate the propensity of the adult population to emigrate, by country/region of birth, period of immigration, province or territory of residence, age and sex.

For the population aged 17 and younger, net emigration rates were calculated by age, sex, and province or territory using population estimates for 2002/2003 to 2011/2012.

Registration on the Indian Register and registration category amendment over an individual’s lifetime

The modules involving registration on the Indian Register have three separate purposes: 1) to model registrations that may occur during an individual’s lifetimeNote as a result of legislative amendments; 2) to model the registration category amendments from 6(2) to 6(1) that may occur during an individual’s lifetime;Note and 3) to model the late registration of individuals who were entitled to registration at birth.

- The legislative amendments that could cause individuals to register during their lifetime are the 1985 amendments of the Indian Act (Bill C-31), the Gender Equity in Indian Registration Act (Bill C-3) which came into effect as of January 2011, as well as S-3: An Act to amend the Indian Act in response to the Superior Court of Quebec decision in Descheneaux c. Canada (Procureur général) (Bill S-3). The latter came into force in two phases, the first of which started in December 2017 and the second in August 2019. For these legislative amendments, target numbers of registrations by year of registration were estimated. From May 2016 to January 2021, target numbers were calculated from the actual registrations recorded on the Indian Register.Note For subsequent years, when very little data are available, the target numbers are derived from projection assumptions, which are described in the “Assumptions” section of this document. Once the targets had been determined, the individuals in the base population who were likely to register under these legislative amendments were identified from among those who did not have Registered or Treaty Indian status (according to distributions specific to each bill), and then their time of registration was determined in advance.Note The majority of individuals selected in this way were initially First Nations people without Registered or Treaty Indian status.

- Amendments from registration category 6(2) to category 6(1) may result from the application of Bill C-3, Bill S-3 or for various other reasons.Note Category amendments from 6(2) to 6(1) arising under C-3 or S-3 were modelled using a method similar to the one just described for registration under legislative amendments, except the target numbers by year of the change and other characteristics specific to each of these two bills were determined only from the category amendments that occurred from May 2016 to January 2021 based on the Indian Register. Thus, for the following years, the assumption was made that there would be no further category amendments under C-3 or S-3. For other registration category amendments from 6(2) to 6(1), annual category amendment numbers by sex and place of residence were calculated based on the average of the data from 2007 to 2017 from the Indian Register. These are assumed to be constant throughout the projection.

- The late registration of individuals entitled to registration on the Indian Register at birth is modelled separately for children and adults. For children born during the simulation, the modelling is done in two steps. First, in order to identify individuals potentially subject to this type of registration, we determine which of the simulated births will be entitled to registration on the register.Note Entitlement depends on the mother’s registration category, whether or not she was in a mixed union at the time the child was born, and the rules of transmitting Registered or Treaty Indian status. Those entitled to registration but not having a Registered or Treaty Indian status at birth are assigned a probability of registering on the Indian Register that depends on their age and whether or not they live on an Indian reserve. The probabilities were derived so that they can reproduce the progression by age observed in the 2016 Census of the proportion of children with a Registered or Treaty Indian status among children who are in principle entitled to register—namely the children with two parents who are Registered or Treaty Indians, or with one parent who is in registration category 6(1).Note Late registration rates derived from the same data are also applied to some children aged 0 to 2 years in the base population. Among adults aged 19 or older, a number of late registrations occur during the projection process among the at-risk population by age group and sex. The annual number of late registrations modelled is the average annual number of registrations of this type from 2007 to 2017, based on the Indian Register.

Intragenerational ethnic mobility of Indigenous people

The purpose of the Indigenous intragenerational ethnic mobility moduleNote is to simulate changes in the reporting of Indigenous group from one census to the next, a phenomenon that is behind a significant share of the increase in the number of Métis and First Nations people observed at least since 1986 in Canada.Note The parameters of the intragenerational ethnic mobility of Indigenous people were calculated using a residual method applied to data from the 1996, 2001, 2006, and 2016 censuses, and the 2011 NHS, adjusted for net undercoverage. It involves calculating the share of the residual growth of a given Indigenous group after the share that can be obtained through fertility, mortality and net migration have been taken into account, for each five-year period. This residual growth is interpreted as resulting from changes in the Indigenous group reported in the censuses (or the NHS). The net gains in Métis and First Nations people obtained this way were divided by the population that was non-Indigenous, non-immigrant and that did not belong to a visible minority group at the start of the period to obtain probabilities of an individual joining the First Nations or Métis group over five years, taking into account age and region of residence. Sets of probabilities were computed for four periods (1996 to 2001, 2001 to 2006, 2006 to 2011 and 2011 to 2016)Note and it is possible to combine them to prepare various projection assumptions.

Change in education level

The last event projected using waiting times is change in education level. Probabilities associated with this event were derived by combining 2001 General Social Survey (GSS) and 2016 Census data adjusted for net undercoverage which, together, include the information required for the projection. First, probabilities of change in education level by year of birth, age, sex, and immigrant status were obtained by fitting logistic regression models to retrospective data from the 2001 GSS. Alignment factors were then calculated to ensure that the previously calculated probabilities make it possible to accurately reproduce the distributions obtained from the 2016 Census for a number of key characteristics. These alignment factors help calibrate the education level of cohorts on the data from the 2016 Census by sex and immigrant status, and take into account the differences in terms of education that exist with respect to individuals’ province or territory of birth, visible minority group, Indigenous group, Registered or Treaty Indian status, and the registration category on the Indian Register.

Characteristics imputed annually

Some components of Demosim are not meant to project events but rather to impute certain characteristics to individuals, including marital status, head-of-family and head-of-household status as well as labour force participation. These characteristics are assigned once a year on a fixed date.

Marital status

Marital status is projected mainly for its use in determining other events during the simulation, particularly fertility, to which it is closely related.

The marital status module is derived from logistic regression models that are estimated using data from the adjusted 2016 Census for the population aged 15 and older. The initial models determine whether or not the individual is in a union. If the individual is in a union, other models determine the type of union (married or common law). Models are stratified by sex and by having or not having an Indigenous identity. They take into account age, education level, number of children at home and the age of the youngest child, immigration status, citizenship status, place of birth, mother tongue, language spoken most often at home, visible minority group, Indigenous group, Registered or Treaty Indian status and the registration category on the Indian Register, as well as place of residence (province or territory, in or outside a census metropolitan area, on or off reserve, or inside or outside Inuit Nunangat).

The probabilities derived from these models evolve during the projection based on trends observed in the 2011 NHS and 2016 Census (adjusted), which showed an increasing propensity for couples to live in a common-law union. The marital status module finds its complement in the mixed union parameters that are used to assign characteristics such as Registered or Treaty Indian status to newborns (see the “Creation of individuals during the simulation” section).Note

Head of household

A head-of-household statusNote is assigned to individuals annually to obtain a projection of the number of private households by certain characteristics, including Indigenous composition.Note The headship rate methodNote is used to establish a relationship between the number of heads of household and the population, by certain characteristics of the projected population. This rate is then multiplied by the projected population to obtain a future number of private households.

For the purposes of these projections, different types of households were identified in the data from the 2016 Census according to a combination of household characteristics (Indigenous composition, household size and the presence of individuals younger than 19 years of age, etc.Note ). The number of heads of household for each type by age group, Indigenous group, Registered or Treaty Indian status, marital status and place of residence was determined and then divided by the total population with the same characteristics to obtain headship rates for use in the annual imputation of head-of-household status during the simulation.Note

Head-of-household status is used strictly to derive a number of households. It is not used as a determinant of other events during simulation. The same holds true for labour force participation.

Labour force participation

The purpose of the labour force participation module is to impute a status to individuals aged 15 and older regarding their labour force participation. The module has been designed to take into account differences in labour force participation among the various groups projected (for example, Indigenous people, visible minority groups, and immigrants). It includes two sets of parameters.

The first is composed of labour force participation rates by sex and age group taken from Labour Force Survey (LFS) data. The parameters are then adjusted to take into account populations excluded from the survey, in particular Indian reserves.

The second is composed of the results of logistic regressions that estimate (separately by sex and age group) the probability of being in the labour force by the following variables: Indigenous group, Registered or Treaty Indian status and registration category on the Indian Register, visible minority group, immigrant status, time elapsed since immigration, immigrant admission category, generation status, marital status, presence of children and age of youngest child, education level, knowledge of official languages, citizenship status and place of residence. The logistic regressions use data from a file that combines data from the 2016 Census and the 2011 NHS (adjusted). Each January 1 in the simulation, these two sets of parameters are combined to determine the labour force participation (in the labour force or not in the labour force) for the upcoming year.

Creation of individuals during the simulation

Aside from individuals in the Demosim base population, individuals may be added to the population during the simulation as a result of births, immigration, and the arrival of non-permanent residents. New individuals are added by creating complete records, that is, records having all the characteristics required for them to be projected by Demosim. The process for assigning characteristics to new individuals is described below.

Creation of newborns

The creation of newborns from births occurring after the start of the simulation requires the use of methods that differ according to the characteristic to be assigned to new individuals. First, a number of characteristics can be assigned deterministically to newborns, such as marital status (not in a union), education level (less than high school), immigrant status (non-immigrant), Canadian citizenship (Canadian citizenship at birth), etc.

Other characteristics are instead assigned probabilistically. The sex of the child is determined by applying a sex ratio of 105 boys born for every 100 girls, as has been observed in Canada and in many other populations around the world for several decades.

For the visible minority group and the Indigenous group, assignment is based on parameters derived by applying the own-children method to the adjusted data from the 2016 Census. Once the youngest children are linked to the woman in the census or NHS most likely to be their mother, it becomes possible to calculate the probability that the child has certain characteristics based on those of their mother (see the characteristics considered in Table 4). Transition matrices and vectors were created for assigning visible minority group and Indigenous group.

| Characteristics attributed | Variables considered | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | N/A (a fixed sex ratio at birth is applied) | |

| Generation status | Characteristics of the child: | - Indigenous identity. |

| Characteristics of the mother: | - Immigrant status; | |

| - Mixed union status. | ||

| Visible minority group | Characteristics of the mother: | - Visible minority group; |

| - Immigrant status; | ||

| - Age at immigration; | ||

| - Place of residence. | ||

| Indigenous group | Characteristics of the mother: | - Indigenous group; |

| - Registered or Treaty Indian status; | ||

| - Visible minority group; | ||

| - Immigrant status; | ||

| - Age at immigration; | ||

| - Place of residence. | ||

| Registered or Treaty Indian status and registration category (6[1] or 6[2]) | Characteristics of the child: | - Indigenous group; |

| - Visible minority group. | ||

| Characteristics of the mother: | - Registered or Treaty Indian status; | |

| - Registration category; | ||

| - Marital status; | ||

| - Mixed union status; | ||

| - Place of residence. | ||

| Source: Statistics Canada, Centre for Demography. | ||

The methods for assigning Registered or Treaty Indian status, registration category on the Indian Register and generation status differ from the methods above by indirectly taking into account information about the child’s father. Births in Demosim are generated by women, and women are not associated with a spouse. Therefore, it is not possible to directly know the father’s characteristics at the time of birth. However, spousal characteristics may be associated with mothers through mixed unions. This is done in Demosim when a child is born.

A first mixed-union module determines whether the mother is in a union with a category 6(1) Registered or Treaty Indian, a category 6(2) Registered or Treaty Indian or an individual not having Registered or Treaty Indian status. The probability that the mother is in one of these types of unions is estimated using a file derived from adjusted 2016 Census microdata that—by using information on the relationship among members of the same census family—links women in a union who gave birth during the previous year to their spouse and their children. The probabilities are calculated based on the mother’s marital status, Registered or Treaty Indian status combined with registration category on the Indian Register, region of residence (on or off reserve) and province or territory of residence, and the child’s Indigenous group and visible minority status.

Probabilities were also calculated using the 2011 NHS to establish trends related to mixed unions by Registered or Treaty Indian status combined with the registration category on the Indian Register and the fact of living on or off reserve. Registered or Treaty Indian status (including the registration category) is then assigned to newborns probabilistically, using transition matrices that take into account the mother’s type of mixed union, as well as other characteristics of the mother and the child (Table 4).Note

An additional adjustment factor is applied to the probabilities of women being in a union with a Registered or Treaty Indian to take into account new registrations and registration category amendments from 6(2) to 6(1) (see the section “Registration on the Indian Register and registration category amendment over an individual’s lifetime”) that occurred during simulation and that cannot be accounted for in the 2016 Census data. This adjustment factor is necessary to increase the likelihood of having Registered or Treaty Indian status transmitted to children born during the simulation. The magnitude of this adjustment factor depends on the number of new registrations and category amendments that occurred during the simulation.

A second mixed-union module uses the same data source to calculate the probability that the woman is in a union with a spouse whose immigrant status is identical or different to her own at the time the child is born in order to determine the child’s generation status. The module includes a series of logistic regression models that take into account age, education level, visible minority group, Indigenous group, time elapsed since immigration, age at immigration, immigrant category, generation status, citizenship status, mother tongue and language spoken most often at home, knowledge of official languages, number of children at home and age of the youngest child and place of residence (province or territory, in or outside a census metropolitan area and on or off reserve).Note

Generation status is then assigned to the newborn as follows: the newborn is considered second generation if the mother is an immigrant not in a mixed union, 2.5 generation if the mother is in a mixed union, and third generation or higher if the mother is not an immigrant and not in a mixed union.

Immigration

Immigration also involves the creation of individuals possessing all the characteristics required for their simulation following their arrival in Canada. This module includes two main dimensions.

First, a predetermined number of newcomers is added annually to the projected population.

Second, the characteristics of new immigrants are determined using a donor imputation method, with donors being selected from among the immigrants in the Demosim base population. The result is a projected immigrant population whose composition is representative of the immigrant population of the donor pool (which itself may be a subset of the immigrant population, for example recently admitted immigrants). Adjustments are also made to some of the characteristics that are likely to have changed between the time of immigration and the time of the 2016 Census—the survey on which Demosim is based—so that they will be as close as possible to what they were at the time of arrival. For instance, when a new immigrant is created, the age assigned to the new immigrant is the donor’s age at immigration (and not the donor’s age in the 2016 Census); the marital status is imputed on arrival using Demosim’s annual marital status imputation parameters; and education on arrival is imputed by Demosim’s education module.

Non-permanent residents

The final Demosim component that requires the creation of individuals is the arrival of new non-permanent residents. This component functions similarly to immigration. Like immigrants, non-permanent residents are projected in two steps: (1) determining an annual net gain in non-permanent residents; and (2) imputing the characteristics of the new non-permanent residents using donors who are selected from among non-permanent residents in the Demosim base population.

Because of its special characteristics, the non-permanent resident population is processed separately in Demosim. Individuals are non-permanent residents for only a short time and there is almost no information available on the propensity of non-permanent residents to experience the events simulated. Therefore, and to maintain consistency with Statistics Canada’s population estimates data on non-permanent residents (annual net change), it is assumed that composition of the non-permanent resident population is perfectly stable. To achieve this, members of this population do not experience any of the events simulated except for fertility, since children born in Canada of non-permanent residents become Canadian citizens at birth. Thus, the assumption is made that each departing non-permanent resident is immediately replaced by the arrival of a new non-permanent resident with the same characteristics as the one who just left. The resulting stability is echoed by the data, at least regarding the composition of this population by age, sex and place of residence, in spite of slight variations from one period to the next.

Assumptions

As is true in any prospective exercise, these population projections were made on the basis of assumptions on the components of population growth. Assumptions were developed not only for Indigenous populations, but also for non-Indigenous populations, which are part of the projections. They were selected to meet the following objective: to create scenarios comprising a plausible range of possibilities for Indigenous populations until 2041.

The assumptions were developed by Statistics Canada in consultation with Indigenous Services Canada (ISC) and based on an analysis of the latest data, existing literature and consultations conducted by Statistics Canada.

The objective of this section is to provide a description and rationale for the main assumptions selected for this projection exercise. Particular attention is given to the description and rationale for the assumptions having the greatest impact on the evolution of Indigenous populations and households in Canada.

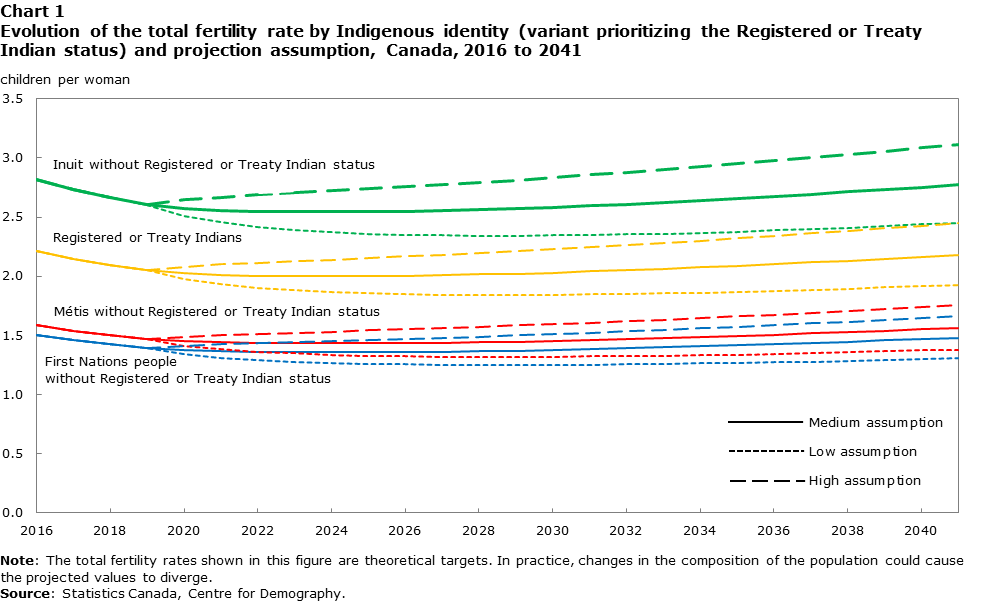

Table 5 offers a short description of the assumptions related to Indigenous populations for each of the main components of the projection model. Because they exert a strong influence on the growth of Indigenous populations, three distinct assumptions were developed for the components of fertility, mortality, intragenerational ethnic mobility, and registration on the Indian Register.

| Components | Number of assumptions | Assumptions |

|---|---|---|

| Fertility | 3Table 5 Note 1 | Level of total fertility rate (TFR) |

| 1 – Low growth: progressive attainment of a TFR of 1.7 children per woman in 2041;Table 5 Note 2 | ||

| 2 – Medium growth: progressive attainment of a TFR of 1.9 children per woman in 2041;Table 5 Note 2 | ||

| 3 – High growth: progressive attainment of a TFR of 2.2 children per woman in 2041.Table 5 Note 2 | ||

| 1 | Differences between population groups | |

| Differences estimated between 2015 and 2016 kept constant. | ||

| Intergenerational transmission of Indigenous group | 1 | Constant rates of transmission at the level observed between 2015 and 2016. |

| Intergenerational transmission of Registered or Treaty Indian status and registration category (including mixed unions) | 1 | Constant rates of transmission at the level observed between 2015 and 2016, with continuation of mixed unions trends observed between 2011 and 2016.Table 5 Note 3 |

| Mortality | 3 | Level of life expectancyTable 5 Note 4 |

| 1 – Low growth: men = 78.8 years / women = 83.0 years in 2041; | ||

| 2 – Medium growth: men = 80.2 years / women = 85.1 years in 2041; | ||

| 3 – High growth: men = 81.3 years / women = 85.6 years in 2041. | ||

| 1 | Differences between population groups | |

| Differences estimated between 2006 and 2016 kept constant. | ||

| Internal migration rates | 1 | Volume and direction of migration flows |

| - For all migration flows, excluding those to and from reserves: reference period from 1996 to 2016 (estimated five-year mobility from the 2001, 2006 and 2016 censuses, and the 2011 NHS); | ||

| - For flows to and from reserves: reference period from 2006 to 2016 (five-year mobility estimated from linkages between the 2006 and the 2011 censuses, and between the 2011 and the 2016 censuses). | ||

| 1 | Differences between population groups | |

| Differences observed between 1996 and 2016 (one-year mobility estimated from the 2001, 2006 and 2016 censuses, and the 2011 NHS) kept constant. | ||

| International migration | 1 | No international migration for Indigenous people. |

| Intragenerational ethnic mobility rate | 3 | 1 – Low growth: |

| Starting level corresponding to the lowest net rate estimated over the four most recent intercensal periods, converging linearly to the average net rate estimated from 1996 to 2016 by 2041; | ||

| 2 – Medium growth: | ||

| Starting level corresponding to the net rate estimated between 2011 and 2016, converging logarithmically to the average net rate estimated from 1996 to 2016 by 2041; | ||

| 3 – High growth: | ||

| Starting level corresponding to the highest net rate observed over the four most recent intercensal periods, converging linearly to the average net rate estimated from 1996 to 2016 by 2041. | ||

| Registration on the Indian Register and registration category amendment over an individual’s lifetime (other than registrations as a result of S‑3) | 1 | C-31 registrations: 1,300 registrations until 2020; |

| C-3 registrations: 3,900 registrations until 2019; | ||

| Late registrations of children aged 0 to 2 years: constant rates; | ||

| Late registrations of adults aged 19 years and over: 400 registrations per year; | ||

| Category amendments from 6(2) to 6(1) under C-3: 2,200 category amendments until 2019; | ||

| Category amendments from 6(2) to 6(1) under S-3 (phase 1): 20,200 category amendments between 2018 and 2019; | ||

| Category amendments from 6(2) to 6(1) under S-3 (phase 2): 24,600 category amendments between 2019 and 2021; | ||

| Category amendments from 6(2) to 6(1) for various other reasons: 700 category amendments per year. | ||

| Registration on the Indian Register as a result of S-3 | 3 | 1 – Low growth: |

| S-3 registrations (phase 1): 16,200 registrations between 2018 and 2032; | ||

| S-3 registrations (phase 2): 18,200 registrations between 2019 and 2041. | ||

| 2 – Medium growth: | ||

| S-3 registrations (phase 1): 25,600 registrations between 2018 and 2032; | ||

| S-3 registrations (phase 2): 40,900 registrations between 2019 and 2041. | ||

| 3 – High growth: | ||

| S-3 registrations (phase 1): 25,600 registrations between 2018 and 2032; | ||

| S-3 registrations (phase 2): 225,200 registrations between 2019 and 2041. | ||

| Household headship rates | 1 | Constant rates at the level observed in 2016. |

Source: Statistics Canada, Centre for Demography. |

||

Fertility