Home alone: More persons living solo than ever before, but roomies the fastest growing household type

Archived Content

Information identified as archived is provided for reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It is not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards and has not been altered or updated since it was archived. Please "contact us" to request a format other than those available.

Released: 2022-07-13

Trends in living arrangements reflect and influence socioeconomic conditions. Population growth and aging, urbanization, rising educational attainment, sustained immigration, rising ethnocultural diversity, and housing affordability have all contributed to shifts in the ways people live.

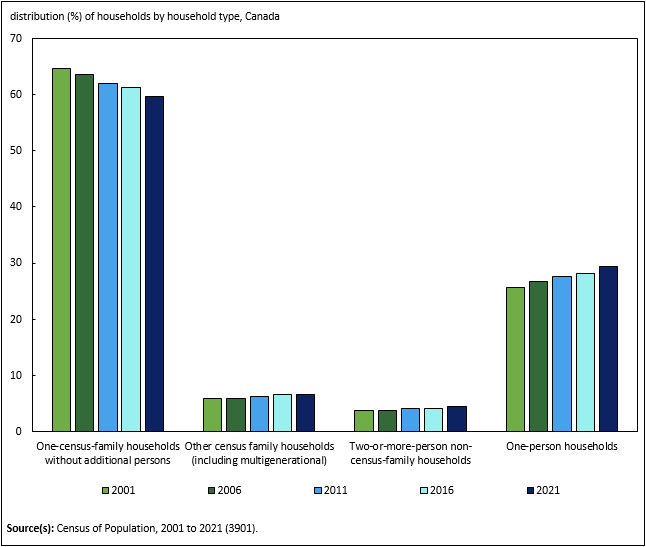

In recent decades, there has been a gradual decrease in the share of households composed of only one family with no additional people. Alternatives like living alone, with roommates, or with extended family members have grown in popularity. The diversification of living arrangements has implications for housing supply and demand, as well as individuals' care and support networks, spending, and economies of scale.

The social and economic disruptions following the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic have also led to changes in the living arrangements of some individuals. According to the Canadian Social Survey – Well-being, Unpaid Work and Family Time, about 1 in 10 adults (11%) surveyed from October to December 2021 stated that because of the pandemic, they had experienced changes in their living arrangements, even if the changes were only temporary.

Today, Statistics Canada is releasing new results from the 2021 Census, including information about families, households, and marital status. This article examines to what extent living arrangements have changed over time and following the onset of the pandemic. The most prevalent and fastest-growing modes of living are found to differ by age group, gender and region of the country.

Highlights

Continuing a long-term pattern of growth, 4.4 million people lived alone in 2021, up from 1.7 million in 1981. This represented 15% of all adults aged 15 and older in private households in 2021, the highest share on record.

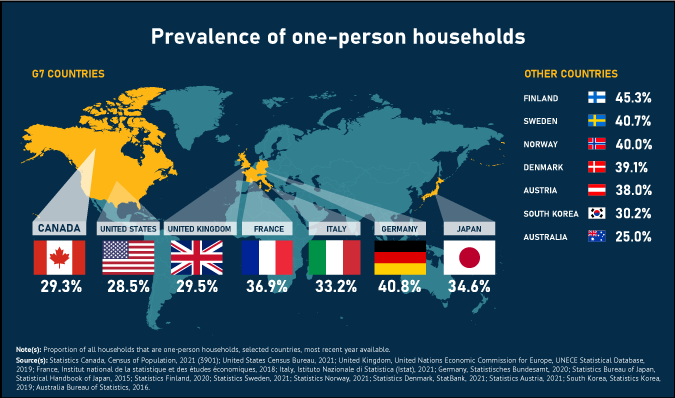

Despite the increase in solo living, the prevalence of one-person households is relatively low in Canada from an international perspective, representing about 3 in 10 households (29.3%) in 2021. Among G7 countries, only the United States had a slightly smaller share (28.5% in 2021).

Solo living is on the rise in middle-adulthood in Canada, with the share of people aged 35 to 44 who live alone doubling from 1981 (5%) to 2021 (10%). In contrast, the share of women aged 65 and older living alone has decreased over time, owing to gradual convergence in the life expectancies of men and women. This is allowing older adults—particularly women—to live as part of a couple for longer.

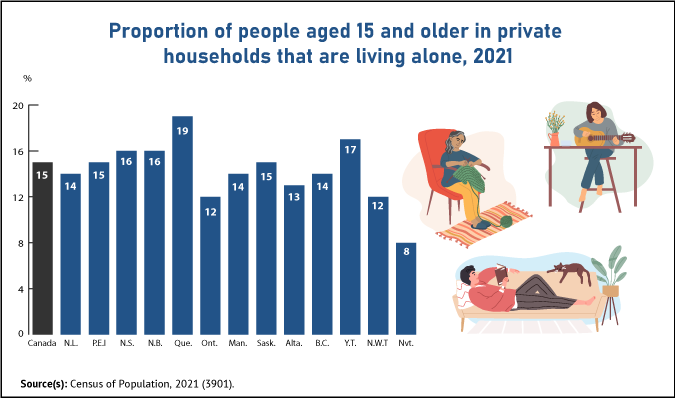

In a continuation of recent trends, the share of adults in private households living alone in 2021 was highest in Quebec (19%) and lowest in Nunavut (8%).

Households composed of roommates—that is, two or more people living together, among which none are part of a census family—are the fastest-growing household type. From 2001 to 2021, the number of roommate households increased by 54%. Despite the strong growth of households composed of roommates, they still represented a small share of all of Canada's households in 2021 (4%).

Nearly 1 million (986,400) households in 2021 were composed of multiple generations of a family, two or more census families, or one census family living with additional persons not in a census family. These households have grown relatively rapidly in the last twenty years (+45%) and represented 7% of all households in 2021.

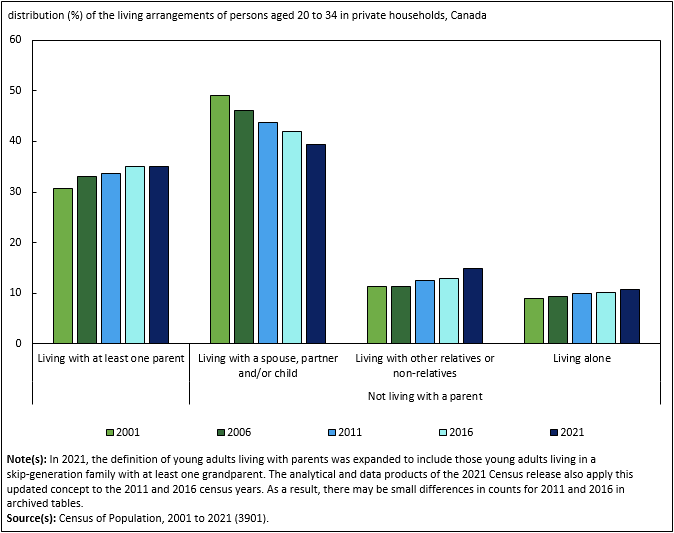

Following steady growth from 2001 (31%) to 2016 (35%), the share of young adults aged 20 to 34 living in the same household as at least one of their parents was unchanged from 2016 to 2021 (35%). In 2021, an additional 15% of individuals in their 20s and early 30s lived with roommates—that is, with extended relatives or other non-related people. This was the fastest-growing living arrangement for this age group from 2016 to 2021.

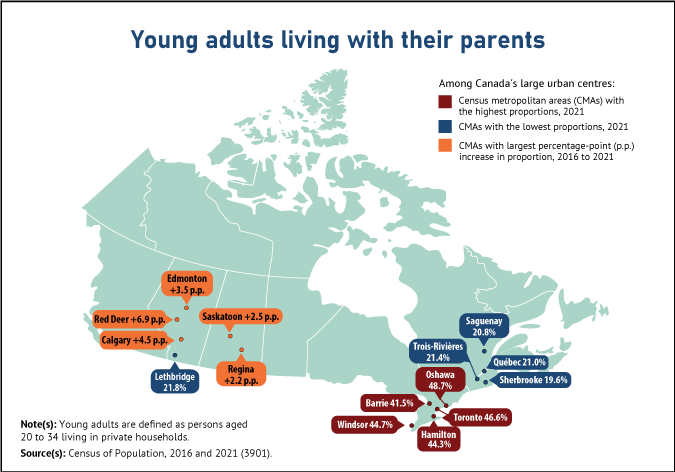

From 2016 to 2021, the largest growth in the proportion of young adults living with at least one parent was recorded in several large urban centres located in Alberta and Saskatchewan: Red Deer (+7 percentage points), Calgary (+5), Edmonton (+4), Saskatoon (+3) and Regina (+2). However, the prevalence remained highest in Ontario's large urban centres, particularly Oshawa, where nearly half (49%) of young adults lived with their parents in 2021.

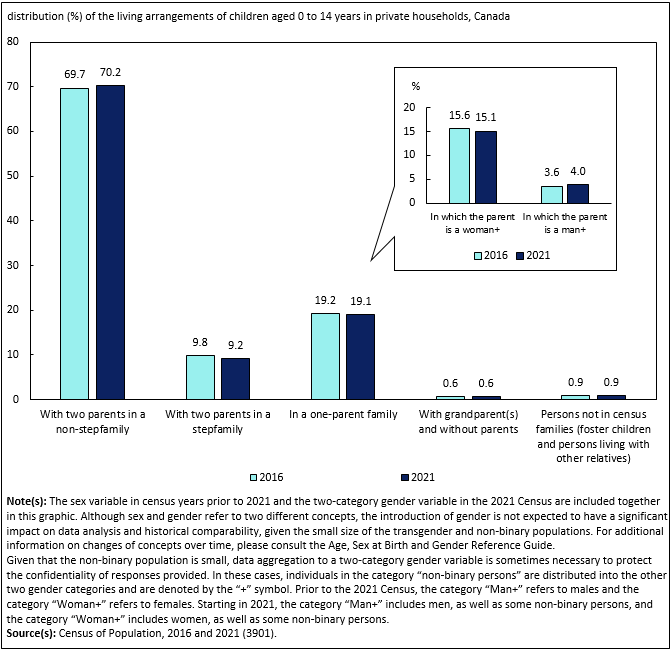

Generally, patterns in the living arrangements of children aged 0 to 14 in private households were fairly stable from 2016 to 2021. However, among children living in a one-parent family, a growing share—over one in five (21%) in 2021—were living with their father, up from 14% in 1981.

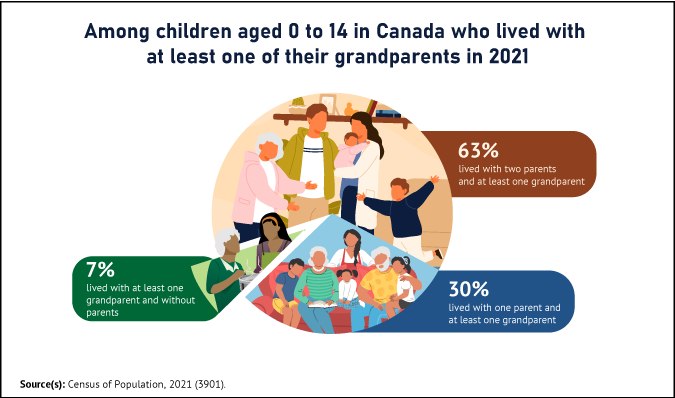

Almost 1 in 10 children aged 0 to 14 in census families (9%), or more than half a million (553,855) children, were living in the same household as at least one of their grandparents in 2021. The vast majority of these children (516,995) lived in a multigenerational household, meaning they lived with at least one parent and at least one grandparent. The remaining 36,860 lived in a skip-generation family with one or more grandparents and without parents present.

Over half a million (550,810) children aged 0 to 14 lived in a stepfamily in 2021, representing 9% of all children in this age group living in census families. This share has been stable since stepfamilies were first identified in the 2011 Census.

There were 26,675 foster children aged 0 to 14 in 2021, down 10% from the 29,590 reported a decade earlier.

Living solo? You're not alone

Continuing a long-term pattern of growth, 4.4 million persons lived alone in 2021, up from 1.7 million in 1981. This represented 15% of all adults aged 15 and older in private households in 2021, the highest share on record.

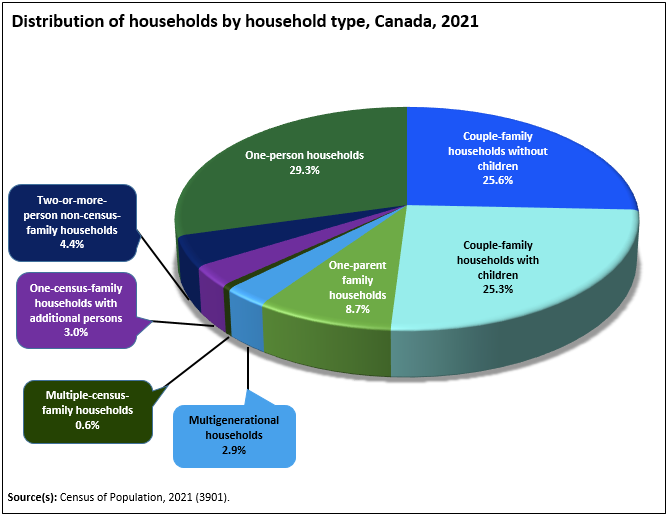

Hand-in-hand with the growing prevalence of living alone, the share of households comprised of only one person continues to grow, as has been the case since at least 1941 when they represented 6% of all households.

In 2016, one-person households became the predominant household type (28%) for the first time in Canada's 150-year history. One-person households continued to hold the top spot among households in 2021, representing just under 3 in 10 households (29%). The continued rise of one-person households—which occurred despite the economic downturn and housing affordability issues in some areas—is almost entirely explained by the aging of the population. Even though proportionately fewer older adults live alone today than in previous generations, living alone is still most prevalent at older ages.

The growth of one-person households has implications for the demand for various types of structural dwellings. In 2021, most one-person households (56%) were situated in an apartment—either in a building with fewer than five storeys (32%), a building with five or more storeys (18%) or a duplex (6%). In contrast, the majority of households with two or more people were in single-detached houses (61%).

Canada still has one of the lowest proportions of one-person households among the G7

Despite the growth of one-person households, the prevalence of these households is relatively low in Canada, from an international perspective. Among G7 countries, only the United States had a smaller share (28.5% in 2021). In contrast, in some European countries, such as Finland, Germany and Norway, more than 4 in 10 households were one-person households.

The relatively small share of one-person households in Canada is linked to its comparatively young population. As population aging accelerates in Canada, it is possible that the share of one-person households will continue to increase. That said, cultural preferences also play a role in the prevalence of living solo. For example, Japan has the oldest population in the world, but not the highest share of one-person households.

Solo living is on the rise among younger adults and declining among older women

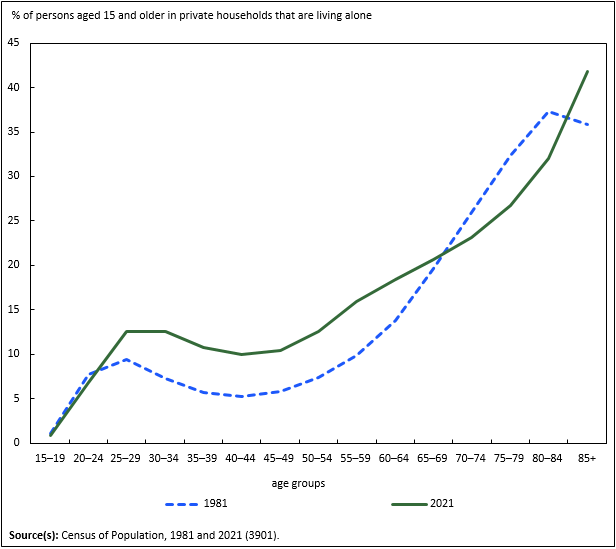

The prevalence of living alone has always been highest at older ages, and this remained the case in 2021: solo dwellers represented 42% of all people aged 85 and older in private households, compared with 7% of people aged 20 to 24.

Nonetheless, living alone has become less prevalent among older women in recent decades. This was the living situation of 53% of women aged 85 and older in private households in 2021, compared with 60% in 2001. Gradual convergence in the life expectancies of men and women since the 1980s has allowed for more people—particularly women—to keep living as part of a couple at older ages. Receiving care and support from a spouse or partner at home could allow more older adults to "age in place" in their homes, when desired.

In contrast, the prevalence of living alone has increased over time at younger ages, particularly in middle adulthood. For example, the share of people aged 35 to 44 living alone doubled from 1981 (5%) to 2021 (10%). This trend may reflect the members of Generation X and the millennials who made up this age group in 2021 postponing family formation until they have finished school and found stable employment. Other societal shifts such as growing relationship instability, the rise of non-cohabiting relationships, urbanization, changing lifestyle preferences and the growth of high-rise apartments offering single-person dwellings have also contributed to the rise in living alone among younger adults.

As a result of these shifts in the demographic characteristics of solo-dwellers, the socioeconomic, housing and family characteristics of people living alone have become more diverse in recent years.

Many solo-dwellers have close family connections and plans to form a union in the future

In the Census of Population, living arrangements are identified based on the usual place of residence of individuals—in most cases, the dwelling in which a person lives most of the time. However, some people who usually live alone also spend part of their time living with others. They may also have close familial connections or responsibilities owing to previous relationships.

According to the 2017 General Social Survey, close to three in four solo-dwellers aged 20 and older in Canada (72%) had previously lived as part of a couple, and over half (55%) had at least one child who lived elsewhere. Additionally, 17% of people living alone in 2017 were in a relationship with someone who lived elsewhere, a situation sometimes referred to as a "living apart together" relationship.

For some, living alone is only a short-term situation while transitioning between different phases of life. This is especially true for young adults: among people aged 20 to 34 who were living alone and not in a couple relationship in 2017, most stated that they were open to living in a common-law union in the future (72%), that they intended to marry in the future (60%) and that they intended to have a child someday (67%). For others, living solo may be a more permanent arrangement, reflecting their preferences and choice to live alone.

Quebec still the leader in solo living, while Nunavut still the lowest

As has been the case since 1996, Quebec held the highest share of persons living alone (19%) among the provinces in 2021. In contrast, Nunavut has held the lowest share of persons living alone since 2001, with 8% of adults in the territory living alone in 2021. Among the provinces, Ontario (12%) and Alberta (13%) had the two lowest shares of adults living solo in 2021.

Differences in sociodemographic characteristics, economic circumstances and housing conditions are among the factors contributing to these variations in solo living across Canada over time.

For instance, Nunavut's relatively younger population and high fertility contribute to fewer people living alone there, in addition to housing problems related to adequacy, affordability and overcrowding.

In contrast, Ontario's low proportion of solo dwellers may reflect higher average shelter costs and the elevated proportion of young adults living with their parents in the province.

Lower shelter costs, tax rebates for solo-dwellers in certain circumstances, as well as various sociocultural factors (link is in French only) including greater instability of unions, contribute to the higher prevalence of solo living in Quebec.

Generally, residents in the downtown core of large urban centres were considerably more likely to be living alone, reflecting the higher-density dwellings that tend to be situated in urban cores. Echoing provincial patterns, solo-living was particularly common in the downtowns of several large urban centres in Quebec: nearly half of adults lived alone in the downtowns of Trois-Rivières (48%) and Saguenay (45%)—two downtowns where the share of older adults is particularly high. Similar levels were found in the downtowns of Drummondville (44%), Québec (44%) and Sherbrooke (43%).

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought into focus the mental health of people living alone

Given that social connections play an important role in life satisfaction and health, concerns have been raised about the mental health implications of living alone.

The potential for experiencing social isolation may be particularly heightened among older solo-dwellers. Compared with previous generations, people aged 65 and older—particularly the younger members of this group who are part of the baby-boomer generation—have had fewer children on average and higher rates of conjugal separation and divorce, potentially shrinking the number of close kin. Those with adult children may no longer live in close geographic proximity to them if their children have moved to another community for work or other reasons.

Population aging and other societal changes have directed growing attention toward social isolation and loneliness in recent years. As evidence of this, in 2018, the United Kingdom announced the creation of a new government-wide initiative to combat loneliness, including the creation of a new ministerial lead for loneliness. Other countries, such as the United States, Sweden and Japan, have created similar governmental portfolios and directed public resources toward reducing loneliness. In Canada, loneliness is one of the indicators in the recently-established national Quality of Life Framework, which will be used to identify future policy priorities.

With the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in Canada in March 2020, many of the opportunities for in-person social connection were removed for solo dwellers as a result of lockdowns, physical distancing, household "bubbles" and other related public health measures. International survey findings suggest that loneliness increased during the pandemic.

As part of Statistics Canada's new Quality of Life Statistics Program, it was reported that in late 2021, nearly one-quarter (24%) of people living alone stated that they always or often felt lonely, more than twice the share among those living with others (11%). Furthermore, those who reported frequently feeling lonely were found to report poorer mental health and lower levels of overall life satisfaction than those who were lonely less often.

Roommates are the fastest-growing type of household

The majority of Canada's households (60%) have a relatively simple structure, containing one census family—defined as a couple, with or without children, or a one-parent family—and no additional people. Over the last 20 years, however, the share of households with other types of living arrangements has steadily increased.

Reflecting this phenomenon, roommate households—composed of two or more people not in a census family—experienced the fastest growth of any household type from 2001 to 2021 (+54%). This was also true in the last five years: from 2016 to 2021, the number of roommate households increased by 14%, more than triple the growth of households with one census family and no additional people (+4%). Nonetheless, the 663,835 roommate households in Canada represented a relatively small proportion of all households (4%) in 2021.

Regionally, the share of households composed of roommates was generally higher in the downtowns of large urban centres, particularly those that host one or more large post-secondary institutions. For instance, 17% of households in downtown Halifax were roommate households, compared with 7% for the entire metropolitan area of Halifax. Similarly, the downtowns of Kingston (12%) and Waterloo (12%) had elevated shares of roommate households. These households were also more prevalent in areas with popular tourist attractions, such as Whistler (13%), and Banff (12%).

Other types of census family households—multiple generations of a family sharing a home, two or more census families living together, or one census family living with additional people who may or may not be related—also grew rapidly in number over the last twenty years (+45%). These households numbered close to 1 million in 2021, representing 7% of all Canada's households. These shifts reflect in part challenges related to housing availability and affordability, as well as shifting lifestyle or cultural preferences.

More young adults live with roommates, while fewer live with a spouse, partner or child of their own

In 2001, almost half (49%) of young adults aged 20 to 34 lived with their spouse, partner or child, without their own parents present. This share fell to 39% in 2021. In contrast, the proportion of young adults living in other arrangements—sharing their home with at least one parent, living with roommates or living alone—has grown, from 51% in 2001 to 61% in 2021.

Since women tend to form unions at a younger age than men, young women were more likely (46%) than young men (32%) to live with their spouse, partner or child without any parents present. Conversely, young men were more likely (68%) than young women (54%) to live with parents, roommates or alone.

The fastest-growing living arrangement for people aged 20 to 34 was living with other people but outside a census family, increasing in number by 20% from 2016 to 2021. This includes sharing a home with roommates or living with an unrelated family or with extended family. This was the living situation of 15% of young adults in 2021, up from 11% in 2001. Young adults live with roommates for financial support, because of a lack of affordable alternative housing options, by choice, for companionship and emotional support, or for other reasons.

The share of young adults living with at least one of their parents levels off

While often considered a relatively new trend, the phenomenon of young adults living in the parental home has been a topic of interest examined by Statistics Canada for nearly a century.

After trending upward since 2001 (31%), the share of young adults aged 20 to 34 living in the same household as at least one of their parents was unchanged from 2016 to 2021 (35%). However, the age profile of young adults who lived with their parents continued to shift to older ages: in 2021, 46% of young adults who lived with their parents were aged 25 to 34, compared with 38% in 2001.

Similar to the reasons for living with roommates, young adults may live with their parents out of necessity, preference, or both. While some young adults may have always remained in their parents' home, others may have returned after one or more periods living elsewhere, including during the pursuit of studies, or to live with a spouse or partner, among other possibilities.

It is likely that during the COVID-19 pandemic, some post-secondary students left their student residence or cancelled plans to live there during their studies. However, given the usual place of residence concept used in the census—which counts individuals as living at their main address only, and indicates that students are to be recorded as living in their parental home, provided they return there periodically throughout the year—it is unlikely that the full extent of these specific pandemic impacts is captured in census data.

The number of young adults living with parents grows fastest in the large urban centres of Alberta and Saskatchewan

Similar to patterns seen in recent census years, the share of young adults living with parents was highest in several large urban centres (census metropolitan areas) in Ontario. Almost half of young adults in Oshawa (49%), Toronto (47%), Windsor (45%) and Hamilton (44%) were living in the same household as at least one parent. These areas generally have relatively high housing prices, close proximity to numerous post-secondary institutions, and relatively high shares of immigrant and racialized groups, the members of which are more likely to co-reside with their parents.

That said, from 2016 to 2021, the share of young adults living with parents decreased slightly in many of Canada's largest urban centres, including Vancouver (-3 percentage points), Montréal and Toronto (-1 percentage point in each). This decrease could stem from more young adults in Canada's largest cities opting to move to smaller communities following the onset of the pandemic. From 2020 to 2021, a record number of people relocated outside of these large urban centres, while rural areas of Ontario and Quebec saw large gains of migrants from within their provinces.

Among young adults living in Canada's large urban centres, living with parents was least common for those residing in the province of Quebec, specifically Sherbrooke (20%), Saguenay, Québec and Trois-Rivières (all 21%). These areas have relatively low housing costs, as well as a lower prevalence of immigrant and racialized groups.

From 2016 to 2021, the largest percentage-point increases in the proportion of young adults living with at least one parent occurred in several large urban centres located in Alberta or Saskatchewan: Red Deer (+7 points of percentage), Calgary (+5), Edmonton (+4), Saskatoon (+3) and Regina (+2). Despite this growth, the prevalence of this living arrangement remained relatively low in these large urban centres. For instance, just over one-quarter of young adults lived with at least one parent in Red Deer (27%) and Saskatoon (26%) in 2021.

Among the provinces and territories, Alberta and Saskatchewan experienced the largest declines in economic activity in the first year of the pandemic mainly as a result of lower energy prices. In the face of job loss, fewer job opportunities or fewer hours worked, some young adults may have chosen to stay in the parental home or move back in with their parents for a period of time. Findings from the 2011 National Household Survey indicate that young adults who live with parents are less likely than other young adults to be employed, to be working full year full time, and to have financial responsibility for household expenses.

Young adults may have delayed starting families during the pandemic

While the COVID-19 pandemic has brought disruption, stress and other challenges to the lives of individuals of all ages, young adults have arguably been particularly hard hit by the various public health measures put in place to combat the pandemic. Recent studies have found that since the onset of the pandemic, the financial, educational, employment and mental health situations of young adults have deteriorated disproportionately in comparison with those of older adults. This multitude of impacts of the pandemic—which were particularly significant for young adults in Canada compared with those in some other countries—could influence their employment and earnings trajectories for years to come.

In addition to the socioeconomic and health implications of the pandemic, lockdowns, physical distancing, and the move to virtual schooling may have created barriers for young adults seeking to form new social networks, friendships or romantic relationships.

According to the Canadian Social Survey – Well-being, Unpaid Work and Family Time, 18% of young adults surveyed from October to December 2021 stated that because of the COVID-19 pandemic, they had experienced changes in their living arrangements, even if the changes were only temporary. Among these young adults, more than one in five (21%) had moved in with at least one of their parents or in-laws.

The pandemic has also had a significant impact on the family planning of young adults. Recent findings indicate that just over 3 in 10 (31%) people aged 25 to 34—the prime childbearing years for women—reported that they now wanted to have fewer children or to have them later as a result of the pandemic.

A growing share of children in one-parent families live with their father

From 2016 to 2021, patterns in the living arrangements of children were fairly stable, as was the case from 2011 to 2016. The majority (70%) of Canada's nearly 6 million children aged 0 to 14 in private households lived with their two biological or adoptive parents, while 9% lived in stepfamilies and 19% lived in one-parent families. The remaining 2% of children lived either: with at least one grandparent and without parents; with other relatives; or were foster children.

The trend towards more equal sharing of parenting time after divorce or separation has contributed to a growing proportion of children with separated or divorced parents who are living in their father's home on Census Day. As a result, the share of children aged 0 to 14 in one-parent families who live with their father has increased in recent decades, from 14% in 1981 to 21% in 2021. This was the living situation of 4% of all children aged 0 to 14 in census families in 2021. Despite this recent increase in prevalence, the share of children living with their father in a one-parent family was even higher in the early decades of the 20th century, owing to higher maternal mortality at that time.

Over half a million children live with at least one of their grandparents, mainly in multigenerational households

Close to 1 in 10 children aged 0 to 14 in census families (9%, or 553,855 children) were living in the same household as at least one of their grandparents in 2021. This proportion was unchanged from 2016 but up from 7% in 2001.

Among the 553,855 children living with grandparents in 2021, the vast majority (93%) lived in a multigenerational household, meaning they lived with at least one parent and at least one grandparent. Specifically, 63% lived with two parents and at least one grandparent, while 30% lived with one parent and at least one grandparent. The remaining 36,860 children lived with at least one grandparent and without parents. Among these children, half (50%) lived with two grandparents, 42% with their grandmother only and 8% with their grandfather only.

Grandparents, parents and grandchildren may live together under the same roof for many reasons. Some may adopt this living arrangement largely out of necessity, for instance, to pool finances, to give or receive care, for reasons of family reunification or as a response to housing shortages. Additionally, living in close proximity to family may reflect cultural or individual preferences.

Previous studies have found that grandchildren living with their grandparents were more likely to live with an immigrant grandparent, have an Indigenous identity, belong to a racialized group, speak a non-official language in the home or be affiliated with Sikh, Hindu, Buddhist or Muslim religions. As the Indigenous and ethnocultural composition of the population in Canada continues to evolve alongside aging of the population, multigenerational living arrangements may play a growing role in the care and social support networks of children, parents and seniors in the coming years.

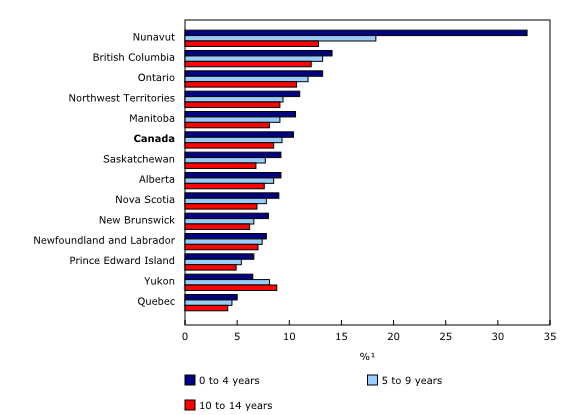

Continuing previous trends, there was wide geographic variation in the share of children living with at least one of their grandparents.

Among the provinces and territories, living with grandparents was most prevalent for children living in Nunavut (22%), British Columbia (13%), Ontario (12%) and the Northwest Territories (10%), reflecting the relatively higher proportions of Indigenous or immigrant population groups in these areas.

Generally, the share of children living with their grandparents was highest for young children aged 0 to 4, and lowest for those aged 10 to 14. Provincial and territorial variations were largest among very young children. In Nunavut, one-third (33%) of children aged 0 to 4 lived with at least one of their grandparents, compared with 5% of children of the same age group living in Quebec.

Among Canada's large urban centres, this living arrangement was particularly prevalent for children living in Abbotsford–Mission, where over one in five children (22%) lived in the same home as at least one of their grandparents. Shares were also elevated in several municipalities in the Greater Toronto Area, particularly Brampton (28%), Markham (23%), Caledon (20%), Mono (20%), Ajax and Pickering (each 19%).

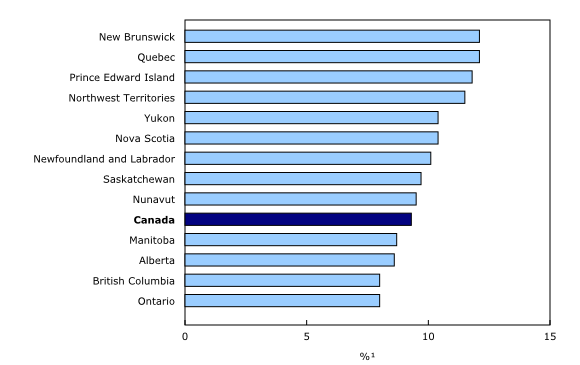

About 1 in 10 children live in a stepfamily, unchanged since 2011

Over half a million (550,810) children aged 0 to 14 lived in a stepfamily in 2021, representing 9% of all children aged 0 to 14 in census families. This proportion has been stable since data on stepfamilies were first collected in the 2011 Census of Population.

The prevalence of living in a stepfamily was highest among children living in New Brunswick and Quebec (12% each) and lowest in British Columbia and Ontario (8% each).

Did you know? Almost one in five children have experienced their parents' breakup

According to the 2019 Canadian Health Survey on Children and Youth, 18% of children aged 1 to 17 had experienced the separation or divorce of their parents. This represents the first national estimate of this phenomenon in many years.

As greater time has passed since their birth, older children are more likely than very young children to have experienced the separation or divorce of their parents, and any subsequent re-partnering. Consequently, regardless of the place of residence, the share of children living in stepfamilies was highest among older children aged 10 to 14 and lowest among younger children aged 0 to 4.

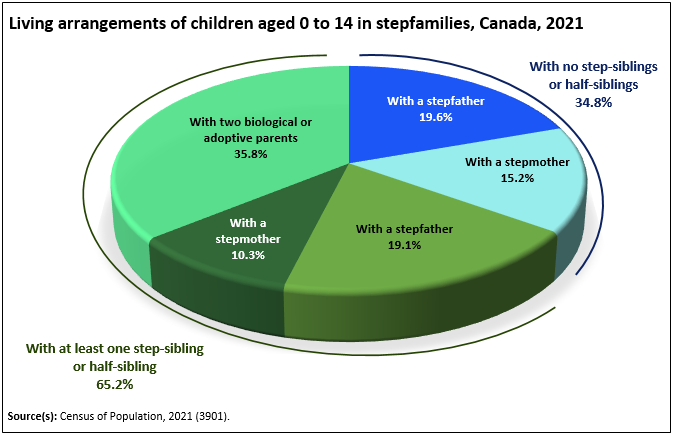

Among children in stepfamilies, just under two-thirds (65%) had at least one half sibling or step sibling. Just over one-third (35%) lived in families where all the children were the biological or adopted children of one parent only.

Among the 353,425 children who lived with a step-parent in 2021, more (60%) had a stepfather as opposed to a stepmother (40%). This may reflect the fact that following separation or divorce, mothers are more likely than fathers to have sole parenting responsibility for their children (sometimes referred to as sole custody).

Fewer foster children since 2011

Foster children are a small population of children who are placed in the foster care system when, for various reasons, they are not able to live in their parental home. Their time in foster care may range from a very short period to a more extended arrangement, depending on the circumstances.

Beginning in 2011, the Census of Population has collected data about foster children living in private households. As these relationships are self-reported, counts may differ from those produced by provincial or territorial agencies responsible for foster care. For instance, an individual may "age out" of the formal foster care system, but remain in the home of their foster parents.

The foster system is under the responsibility of the provinces and territories. While age criteria for foster care eligibility vary across jurisdictions, the majority (62%) of people in foster care in 2021 were aged 0 to 14.

There were 26,675 foster children aged 0 to 14 in Canada reported in the 2021 Census of Population, representing about 1 in every 250 children (0.4%) in this age group living in private households.

Despite growth in the size of the total population aged 0 to 14, the number of foster children in this age group has decreased by 10% from the 29,590 counted in 2011, the year data on foster children were first collected in the Census of Population. This pattern may reflect policies on the part of authorities to keep children with their parents or relatives when possible, through preventive interventions such as parental education and support programs. A lack of available foster families may also be a contributing factor: many provinces and territories have called for more foster families in recent years.

As has been the case since 2011, Manitoba had the highest share of children aged 0 to 14 in private households who were foster children in 2021 (2%). This was quadruple the national average and 10 times the proportion in neighbouring Ontario (0.2%). According to the 2016 Census, Indigenous children aged 0 to 14 were 13 times more likely (4%) than non-Indigenous children (0.3%) to be foster children.

Looking ahead

In the coming months, additional releases from the 2021 Census will reveal more details about the diversity of living arrangements among Canada's various population groups, including different ethnocultural, immigrant, language, and Indigenous communities, as well as according to the income and education characteristics of individuals.

Note to readers

Readers are invited to download the StatsCAN app to view the census results.

Definitions, concepts and geography

Counts are calculated on rounded data and may not necessarily add up to the total.

In censuses prior to 2021, concepts and classifications relating to the family characteristics of individuals used information from a question about the sex of individuals. Beginning in 2021, the census asks questions about both the sex at birth and the gender of individuals. While data about sex at birth are needed to measure certain indicators, for the purposes of the Families, Households and Marital Status release, gender (as opposed to sex) is now the standard variable used in concepts and classifications. For more details on the new gender concept, including impacts on historical comparability, see Age, Sex at Birth and Gender Reference Guide, Census of Population, 2021.

The new gender variable impacts the classification of family variables involving couples families. For more information, see Families, Households and Marital Status Reference Guide, Census of Population, 2021 and Gender diversity status of couples: New information in the 2021 Census.

The sex variable in census years prior to 2021 and the two-category gender variable in the 2021 Census are included together in this analysis to make historical comparisons. Although sex and gender refer to two slightly different concepts, the introduction of gender in 2021 is not expected to have a significant impact on data analysis and historical comparability, given the small size of the transgender and non-binary populations. For additional information on changes of concepts over time, please consult the Age, Sex at Birth and Gender Reference Guide, Census of Population, 2021.

Given that the non-binary population is small, data aggregation to a two-category gender variable is sometimes necessary to protect the confidentiality of responses provided. In these cases, individuals in the category "non-binary persons" are distributed into the other two gender categories. Unless otherwise indicated in the text, the category "men" includes men (and/or boys), as well as some non-binary persons. The category "women" includes women (and/or girls), as well as some non-binary persons.

Considerations for examining families and living arrangements with the Census of Population

As a consequence of changes in the family and society overall in recent decades, many people live at more than one residence throughout the year. However, the census does not capture the phenomenon of individuals who split their time living in multiple households.

The main purpose of the Census of Population is to enumerate the population. To ensure that individuals are counted once and only once in the census, individuals in private households are counted as residing at only one dwelling, and in only one household, by applying the concept of usual place of residence. As part of this concept, rules are applied for individuals who have multiple residences, including the following:

• Family members who live elsewhere for part of the year for work-related reasons should be included at their family's home regardless of the amount of time they spend there.

• Children who split their time throughout the year between the homes of two parents or guardians should be included in the home where they live most of the time. If they spend an equal amount of time with each parent or guardian, they should be included where they were staying on Census Day.

• Students who periodically return to their parents' home should be listed only at this home, even though they may spend more time living elsewhere.

2021 Census of Population products and releases

Today, Statistics Canada is releasing a third series of results from the 2021 Census of Population.

Several 2021 Census products are also available today on the 2021 Census Program web module. This web module has been designed to provide easy access to census data, free of charge.

Analytical products include two articles in The Daily.

Data products include the families, households, and marital status results for a wide range of standard geographic areas, available through the Census Profile and data tables.

Focus on Geography provides data and highlights on key topics found in this Daily release at various levels of geography.

Reference materials are designed to help users make the most of census data. They include the Guide to the Census of Population, 2021, the Dictionary, Census of Population, 2021, and the 2021 Census of Population questionnaires. The Families, Households and Marital Status Reference Guide is also available. A new census fact sheet, Gender diversity status of couples: New information in the 2021 Census, is also available. The Balancing the Protection of Confidentiality with the Needs for Disaggregated Census Data report was previously released in reference materials.

Geography-related 2021 Census Program products and services can be found under Census Geography. This includes GeoSearch, an interactive mapping tool, and thematic maps, which show data for various standard geographic areas, along with Focus on Geography and the Census Program Data Viewer, which are data visualization tools.

Videos on census concepts can be found in the Census learning centre.

An infographic, A portrait of Canada's families in 2021 is also available.

Over the coming months, Statistics Canada will continue to release results from the 2021 Census of Population and provide an even more comprehensive picture of the Canadian population. Please see the 2021 Census release schedule to find out when data and analysis on the different topics will be released throughout 2022.

Contact information

For more information, or to enquire about the concepts, methods or data quality of this release, contact us (toll-free 1-800-263-1136; 514-283-8300; infostats@statcan.gc.ca) or Media Relations (statcan.mediahotline-ligneinfomedias.statcan@statcan.gc.ca).

- Date modified: