Labour Force Survey, August 2020

Archived Content

Information identified as archived is provided for reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It is not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards and has not been altered or updated since it was archived. Please "contact us" to request a format other than those available.

Released: 2020-09-04

Context: COVID-19 restrictions continue to ease

The August Labour Force Survey (LFS) results reflect labour market conditions as of the week of August 9 to 15, five months following the onset of the COVID-19 economic shutdown. By mid-August, public health restrictions had substantially eased across the country and more businesses and workplaces had re-opened.

Assessing the labour market as lifting of COVID-19 restrictions continues

This LFS release continues to integrate the international standard concepts such as employment and unemployment with supplementary indicators that help to monitor the labour market as restrictions are lifted and capture the full scope of the impacts of COVID-19.

A series of survey enhancements were continued in August, including supplementary questions on working from home, workplace adaptations and financial capacity. New questions were added on concerns related to returning to usual workplaces and receipt of federal COVID-19 support payments.

This release also includes, for the second time, information on the labour market conditions of population groups designated as visible minorities. Through the addition of a new survey question and the introduction of new statistical methods, the LFS is now able to more fully determine the impact of the COVID-19 economic shutdown on diverse groups of Canadians.

Data from the LFS are based on a sample of more than 50,000 households. Statistics Canada continued to protect the health and safety of Canadians in August by adjusting the processes involved in survey operations. We are deeply grateful to the many Canadians who responded to the survey. Their ongoing cooperation ensures that we continue to paint an accurate and current portrait of the Canadian labour market and Canada's economic performance.

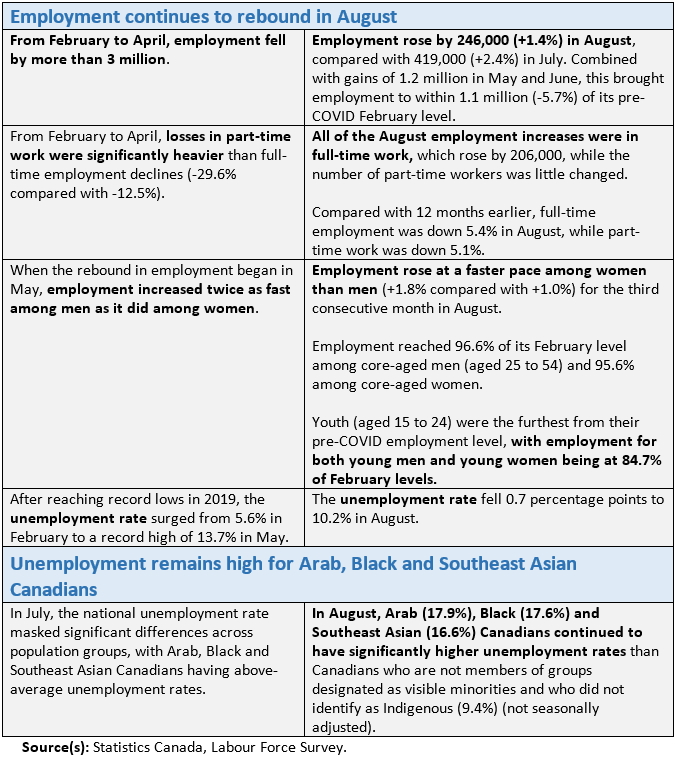

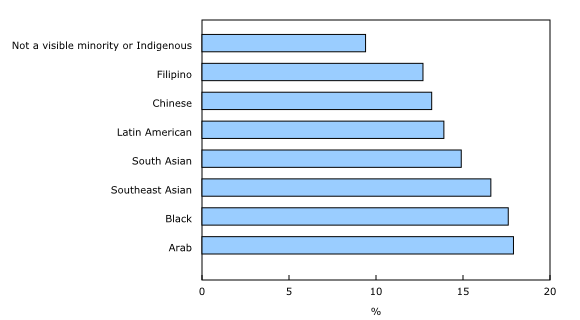

Employment continues to rebound in August

Employment rose by 246,000 (+1.4%) in August, compared with 419,000 (+2.4%) in July. Combined with gains of 1.2 million in May and June, this brought employment to within 1.1 million (-5.7%) of its pre-COVID February level.

The number of Canadians who were employed but worked less than half their usual hours for reasons likely related to COVID-19 fell by 259,000 (-14.6%) in August. Combined with declines in May, June and July, this left COVID-related absences from work at 713,000 (+88.3%) above February levels.

As of the week of August 9 to 15, the total number of Canadian workers affected by the COVID-19 economic shutdown stood at 1.8 million. In April, this number reached a peak of 5.5 million, including a 3.0 million drop in employment and a 2.5 million increase in COVID-related absences from work.

The number of Canadians working from home declines for the fourth consecutive month

In April, at the height of the COVID-19 economic shutdown, 3.4 million Canadians who worked their usual hours had adjusted to public health restrictions by beginning to work from home. This number has fallen each month since May, when the gradual easing of public health restrictions began, and reached 2.5 million in August.

Among Canadians who worked their usual hours in August, the total number working from home fell by nearly 300,000 compared with July, while the number working at locations other than home increased by almost 400,000.

Core-aged men and women edge closer to pre-shutdown employment levels

Employment rose at a faster pace among women (+150,000; +1.8%) than men (+96,000; +1.0%) for the third consecutive month in August.

Core-age men (aged 25 to 54) have been the least affected by the shutdown and their employment level in August reached 96.6% of its February level. Employment among core-aged women, which was hit harder and has been slower to recover, reached 95.6% of pre-pandemic levels, while employment among workers aged 55 years and older reached 94.5% of pre-COVID levels.

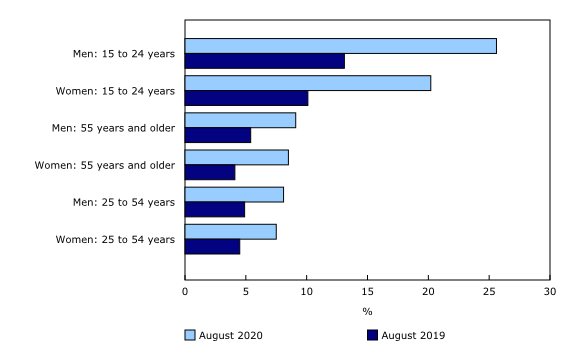

Youth (aged 15 to 24) were most affected and remained the furthest from their February employment level, with employment for both young men and young women being at 84.7% of February levels.

Employment growth concentrated in full-time work

All of the employment increase in August was in full-time work, which rose by 206,000 (+1.4%), while the number of part-time workers was little changed.

Nevertheless, full-time employment stood at 93.9% of pre-pandemic levels in August, compared with 96.1% for part-time work. In the months prior to the COVID-19 economic shutdown, full-time employment had reached record highs, while growth in part-time work was relatively flat. Compared with 12 months earlier, full-time employment was down 5.4% in August, while part-time work decreased 5.1%.

Self-employment declines for the first time since April

For self-employed Canadians, the COVID-19 economic shutdown and subsequent gradual re-opening of the economy have had a greater impact on total hours worked than on employment. From February to April, the self-employed experienced relatively modest job losses (-79,000; -2.7%) compared with employees (-2.9 million; -18.0%), but a greater reduction in total hours worked (-41.9% compared with -25.1%). As total employment rebounded from April to July, the number of self-employed workers was little changed, but their total number of hours worked increased notably, reaching 82.1% of pre-COVID levels in July.

In August, self-employment declined for the first time since April, falling by 58,000 (-2.1%). This was mostly the result of declines in the number of solo self-employed—that is, those with no employees (not seasonally adjusted). In August, 24.2% of the solo self-employed worked less than half of their usual hours, much higher than the share for employees (5.7%), but an improvement compared with 54.5% in April (not seasonally adjusted).

Unemployment rate continues to fall while labour force participation recovers

The unemployment rate fell 0.7 percentage points to 10.2% in August. As a result of the COVID-19 economic shutdown, the unemployment rate had more than doubled from 5.6% in February to a record high of 13.7% in May. By way of comparison, during the 2008/2009 recession, the unemployment rate rose from 6.2% in October 2008 and reached a peak of 8.7% in June 2009. It took approximately nine years before it returned to its pre-recession rate.

The unemployment rate fell most sharply in August among core-aged women aged 25 to 54 years old, down 1.2 percentage points to 7.5%, the lowest unemployment rate among all major groups. This decline was largely due to employment increases, as overall labour force participation was unchanged from July. The unemployment rate for core-aged men fell 0.7 percentage points to 8.1%, also the result of increased employment, with little change in their labour market participation.

The number of unemployed Canadians declined for the third consecutive month, falling by 137,000 (-6.3%) in August to just over 2.0 million. Nevertheless, this was well above the previous record high of 1.7 million in November 1992 during the recession of the early 1990s.

In any given month, the net change in unemployment is the difference between the number of people becoming unemployed and those leaving unemployment, either because they became employed or left the labour force. In August, 864,000 Canadians moved out of unemployment while 725,000 entered unemployment. The majority of those who left unemployment became employed (58.3%), while most of those who became unemployed in August (59.2%) had been out of the labour force in July.

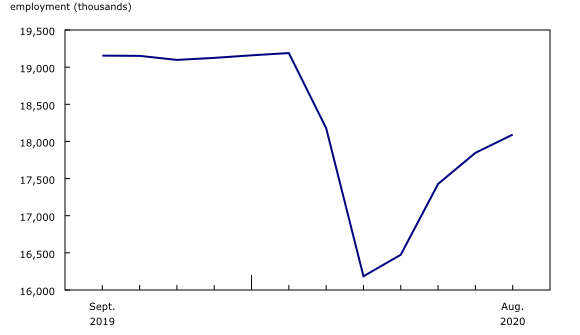

Temporary layoffs continue to decline, approaching pre-COVID levels

The unemployed include three main groups of people: those on temporary layoff who expect to return to a previous job within six months; those who do not expect to return to a previous job and are looking for work; and those who have arrangements to begin a new job within four weeks.

The number of Canadians on temporary layoff rose from 99,000 in February to a record 1.2 million in April, before falling to 460,000 by July. In August, the number of Canadians on temporary layoff continued to decline sharply, falling by half (-49.9%) to 230,000.

The net change in the number of people on temporary layoff is the difference between those becoming unemployed on temporary layoff and those leaving that status to become employed, to search for a new job or to leave the labour force. Just over one-third of those who were on temporary layoff in July became employed in August, while about one-sixth started looking for work and one-sixth left the labour force (not seasonally adjusted).

Number of job searchers increases for the sixth consecutive month

In August, 1.8 million Canadians were looking for work, following an increase that month of 93,000 (+5.4%) and a total increase since February of 782,000 (+75.6%). In comparison, the number of job searchers increased by 403,000 (+40.0%) during the 2008/2009 recession.

The profile of job searchers in August reflected the ongoing impact of the COVID-19 economic shutdown on the labour market. On a year-over-year basis, job seekers in August who had worked in the previous 12 months were more likely to have held their last job in the industries most affected by COVID-19, including the information, culture and recreation; accommodation and food services; and transportation and warehousing industries (not seasonally adjusted). Compared with 12 months earlier, job seekers in August 2020 were more likely be youth (33.7% versus 29.5%).

Gender gaps in labour force participation persist

The labour force—that is, the number of people counted as either employed or unemployed—rose by 109,000 (+0.5%) in August, the fourth consecutive monthly increase. Labour force participation increased by 72,000 (+0.8%) among women and by 37,000 (+0.4%) among men.

The labour force participation rate—the labour force as a share of the population aged 15 and older—rose to 64.6% in August, within 0.9 percentage points of its pre-COVID level (65.5%).

Among both core-aged men and women, the participation rate was unchanged in August. The rate for men in this age group was within 0.2 percentage points of its pre-COVID level (90.9% compared with 91.1%), while for core aged-women it was 1.3 percentage points lower than in February (82.1% compared with 83.4%). This is an indication that women continue to engage in non-employment-related activities—including caring for children and family members—at a higher rate than prior to COVID-19.

The labour force participation rate for young men aged 15 to 24 had virtually returned to its pre-COVID level (64.6% compared with 64.2%) by August. For young women, participation remained lower than in February (63.1% compared with 65.1%).

The number of people wanting a job but not searching holds steady

The number of people who wanted to work but did not search for a job was little changed in August. If people in this group were included as unemployed, the adjusted unemployment rate would be 13.0%. The adjusted unemployment rate was 13.8% in July and 7.3% in February.

Labour underutilization rate continues to decline

Labour underutilization occurs when people who could potentially work are not working, or when people could work more hours than they are currently. The "labour underutilization rate" combines those who were unemployed, those who were not in the labour force but who wanted a job and did not look for one, and those who were employed but worked less than half of their usual hours for reasons likely related to COVID-19.

In response to the COVID-19 economic shutdown, labour underutilization reached a peak of 36.1% in April. As of July, as the economy continued to recover, it had fallen to 22.4%. In August, labour underutilization continued to decrease, falling to 20.3%, but remained substantially higher than pre-pandemic levels (11.2% in February).

While the labour underutilization rate was similar for men and women prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the rate has been higher for women since February. In August, the rate remained slightly higher for women (21.0%) than men (19.7%). The labour underutilization rate for youth was 32.5% in August, down from its peak of 51.8% in May but still higher than pre-COVID levels (15.9%).

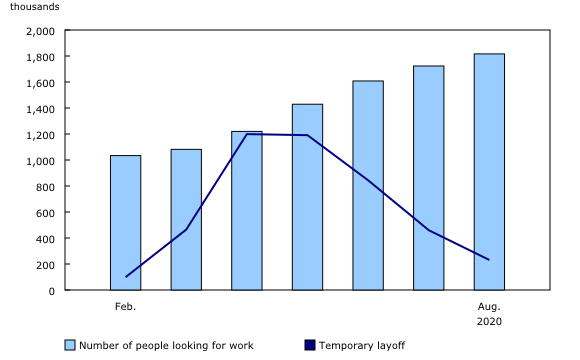

Differences persist in labour market conditions of diverse groups of Canadians

As part of Statistics Canada's ongoing commitment to understanding the impact of COVID-19 on diverse groups of Canadians, a new question was added to the Labour Force Survey in July, asking respondents aged 15 to 69 to report the population groups to which they belong. This new information will be used on an ongoing basis to shed light on the evolving labour market conditions of population groups designated as visible minorities, including the extent to which these are shaped by regional and sectoral conditions.

Unemployment remains high for Arab, Black and Southeast Asian Canadians in August

As in July, the national unemployment rate in August (11.1% among the population aged 15 to 69, not seasonally adjusted) masks significant differences across population groups. For example, Arab (17.9%), Black (17.6%) and Southeast Asian (16.6%) Canadians continued to have significantly higher unemployment rates than Canadians who were not a member of a population group designated as a visible minority and who did not identify as Indigenous (9.4%, not seasonally adjusted).

The unemployment rate among South Asian Canadians fell 2.9 percentage points in August to 14.9% (not seasonally adjusted). Half (49.9%) of South Asian Canadians live in the Toronto census metropolitan area (CMA), a region which saw strong employment growth (+121,000; +3.8%) and accounted for nearly half of total monthly employment gains in August.

Employment rate increases for very recent immigrants, driven by declining immigration

The employment rate among very recent immigrants (five years or less) rose for the fourth consecutive month, up 2.2 percentage points to 62.7% (not seasonally adjusted) in August. The increase was mostly due to an ongoing decline in the size of this population group resulting from a COVID-related drop in new immigrants to Canada.

In August, the employment rate also increased among landed immigrants of more than five years (+1.6 percentage points to 56.1%) and those born in Canada (+0.4 percentage points to 59.5%). Among the three groups, the employment rate for very recent immigrants was the closest to pre-pandemic levels (-1.5 percentage points), followed by those born in Canada (-1.9 percentage points) and landed immigrants of more than five years (-3.2 percentage points).

Employment declines for Indigenous people

Employment among Indigenous people living off-reserve decreased by 1.8% (-9,700) from July to August, while employment among non-Indigenous Canadians rose by 1.3% (+223,000) (not seasonally adjusted). In August, employment for Indigenous people was at 91.4% of its February level, compared with 96.7% for non-Indigenous Canadians.

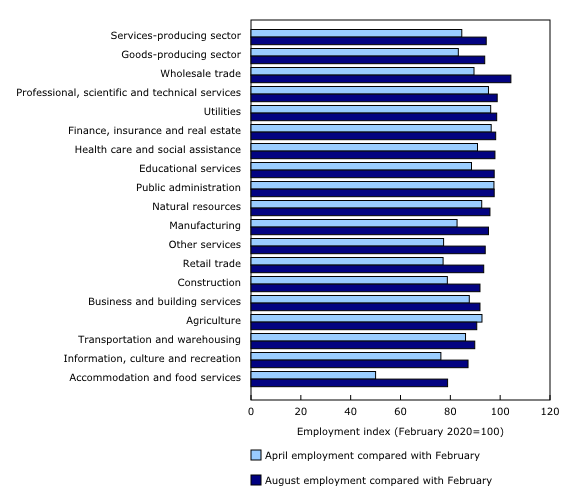

Employment growth in the services sector outpaces that of the goods-producing sector

Employment continued to increase at a faster pace in the services-producing sector (+218,000; +1.5%) in August than in the goods-producing sector (+28,000; +0.7%). Employment reached 94.4% of its pre-COVID February level in the services sector, compared with 93.8% for the goods-producing sector.

Employment growth in the services sector was driven by gains in educational services, accommodation and food services and the "other services" industry. In the goods sector, gains in manufacturing were partially offset by declines in natural resources.

Employment recovery slows in accommodation and food services and in retail trade

Accommodation and food services as well as retail trade were among the industries hardest hit by the initial COVID-19 economic shutdown. By April, employment had fallen to half (-50.0%) of its pre-pandemic level in accommodation and food services and to 77.1% of its pre-COVID-19 level in retail trade. Starting in May, employment rebounded in both sectors as many provinces began reopening their economy.

Employment growth in accommodation and food services rose by 18.4% per month on average from May to July. In August, however, the pace of growth in the industry slowed to 5.3% (+49,000). Despite these recent gains, employment in accommodation and food services was at 78.9% of its February level. August marked the fifth full month of international travel restrictions, which continues to affect industries with strong ties to tourism.

The number of people employed in retail trade edged up 0.7% (+14,000) in August, following average monthly increases of 6.3% over the previous three months. Employment in retail trade reached 93.4% of its pre-COVID-19 level, but fell just below the rate of recovery for total employment (94.3%).

While employment remained below pre-COVID-19 levels, retail sales in June were higher than in February and are expected to continue to rise in July, based on preliminary estimates. This highlights potential structural changes within the industry as employers have been able to increase their sales despite a smaller workforce.

Employment in educational services up sharply as return-to-school measures are implemented

Employment rose by 51,000 (+3.9%) in educational services in August, reaching 97.6% of its pre-pandemic level. This was the fourth consecutive monthly employment increase and the largest since April, when employment fell to 88.5% of its pre-pandemic level. As thousands of students return to school in August and September, almost all workers in educational services (99.2%) reported that they or their employer had put in place measures to reduce the risk to COVID-19 exposure, such as physical distancing protocols and access to personal protective equipment.

Continued easing of COVID-19 restrictions leads to employment growth in the 'other services' industry, including personal care services

The number of people employed in the 'other services' industry increased by 38,000 (+5.2%) in August, reaching 94.0% of its pre-COVID-19 level. This industry includes personal care services businesses, such as hair and beauty salons, which progressively reopened across Canada over the summer.

Employment gains in the goods-producing sector led by manufacturing

Employment growth in the goods-producing sector was almost entirely attributable to manufacturing (+29,000; +1.8%) in August, with the gains concentrated in Ontario, Quebec and British Columbia. Employment in manufacturing reached 95.3% of its pre-COVID-19 level.

Results from the most recent Canadian Survey on Business Conditions indicated that in June, nearly one-quarter of manufacturing businesses expected to add more employees over the next three months.

Meanwhile, the number of people employed in the natural resources sector declined by 9,000 (-3.0%), with most of the decrease in Alberta (-7,000; -5.0%). Capital expenditures in the oil and gas extraction industries declined by over half (54%) from the first quarter to the second quarter, including spending on exploration and evaluation. Nevertheless, employment in the natural resources sector was within 95.9% of its February level and remained above the all-industry average.

Employment increases in most provinces

Employment increased in every province except Alberta and New Brunswick, with the largest gains in Ontario and Quebec. For further information on key province-level and industry-level labour market indicators, see Labour Force Survey in brief: Interactive app.

Employment in Ontario rose by 142,000 in August (+2.0%), nearly all in full-time work, while the unemployment rate fell by 0.7 percentage points to 10.6%. Combined with the employment increases in June and July (+529,000), the gains in August brought employment in Ontario to within 93.6% of its pre-pandemic level. By the start of the August LFS reference week, restrictions had eased for most of Ontario, including Toronto and the Peel Region. By the middle of the week, on August 12, the region of Windsor-Essex joined the rest of the province in Stage 3.

In the CMA of Toronto, employment increased by 121,000 (+3.8%), nearly double the growth rate of the province, and reached 93.3% of its pre-pandemic level.

In Quebec, employment increased by 54,000 (+1.3%) in August, building on gains of 576,000 over the previous three months, and bringing employment in the province to within 95.7% of its pre-COVID level. August employment growth was entirely in full-time work and the unemployment rate fell by 0.8 percentage points to 8.7%, the fourth consecutive monthly decline.

In the Montréal CMA, employment grew by 38,000 (+1.8%) in August and reached 96.0% of its pre-pandemic level.

Employment rose in most Western provinces in August. British Columbia reported the largest increase, up 15,000 (+0.6%). Employment reached 94.1% of its February level and the unemployment rate fell 0.4 percentage points to 10.7%.

While employment in Alberta was little changed, the unemployment rate declined by a full percentage point to 11.8% as fewer people looked for work.

In Atlantic Canada, Nova Scotia had the largest employment gain in August, up 7,200 (+1.6%), mostly in part-time work. The unemployment rate was little changed at 10.3%, as more Nova Scotians participated in the labour market. After notable increases in May and June, employment in New Brunswick held steady for the second consecutive month.

Employment remains far below pre-COVID levels for both low-wage workers and youth

In August, employment increased at a faster pace (+2.3%; +64,000) among those who earned less than $16.03 per hour (two-thirds of the 2019 annual median wage of $24.04/hour) than among other employees (+1.7%; +213,000) (not seasonally adjusted).

Nevertheless, employment remained well below pre-pandemic levels for low-wage employees (87.4%) when compared with all other employees (99.1%, not seasonally adjusted). This gap is entirely driven by low-wage employment in the services-producing industries, which reached 86.0% of February levels in August (not seasonally adjusted). In contrast, employment for low-wage employees in goods-producing industries has been relatively stable around pre-COVID levels since June.

The employment recovery for low-wage employees was greater among men (89.3%) than women (86.1%), entirely due to faster recovery among young men (106.3%) than young women (96.8%) (not seasonally adjusted).

Southeast Asian Canadian employees most likely to earn low wages

Low-wage employees accounted for an above-average share of all employees in August in most of the population groups designated as visible minorities for which reliable estimates can be produced using the current LFS sample size. Nearly one-third of Southeast Asian (32.0%), one-quarter of Black (24.9%) and just over one-fifth of Arab (21.4%) employees made less than $16.03 per hour. The share of Chinese employees earning low wages (17.4%) was similar to that of employees who were not a visible minority and did not identify as Indigenous (15.9%) (not seasonally adjusted).

Youth employment increases in August but remains far below pre-COVID levels

After falling by over one-third (-34.2%; -873,000) from February to April, employment among youth aged 15 to 24 increased for the fourth consecutive month in August (+55,000; +2.6%). This was a slower pace than in June (+15.4%) and July (+6.9%). Employment gains were split among part-time (+28,000; + 2.4%) and full-time (+27,000; +2.8%) work.

Employment was 15.3% below pre-pandemic levels for both young men and young women in August, by far the largest gap among the main demographic groups.

On a year-over-year basis, youth employment in accommodation and food services was down 24.6% in August. In contrast, youth employment had fully, or almost fully, recovered in other large sectors in August, including wholesale and retail trade (101.1%), health care and social assistance (106.6%), and construction (99.1%), compared with 12 months earlier (not seasonally adjusted).

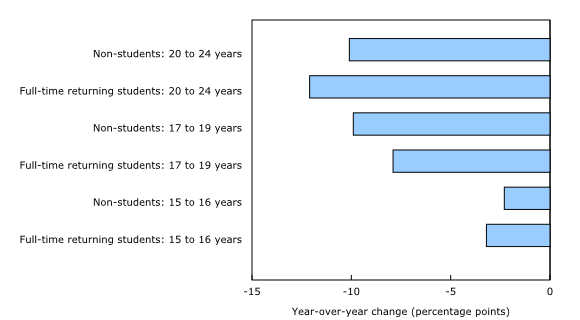

Summer students continue to face challenging labour market conditions

Employment among returning students aged 15 to 24—those who were enrolled full-time in March and intend to return in September—fell by 152,000 (-11.4%) on a year-over-year basis in August, with declines in both part-time and full-time work (not seasonally adjusted). The decline among non-student youth was even more pronounced, falling by 181,000 (-15.1%) year over year.

Almost 90% of the employment losses among returning students aged 15 to 24 (-135,000 on a year-over-year basis, not seasonally adjusted) occurred in Ontario, where restrictions were eased later than in other provinces.

The employment rate for returning students aged 15 to 24—that is, the share of returning students who were employed—declined on a year-over-year basis in every province except Manitoba, Quebec, and Saskatchewan, where the rates were little changed. In Ontario, the employment rate of returning students was 40.7% in August, down 11.9 percentage points year over year and the lowest among the provinces. The employment rate among returning students was highest in Prince Edward Island (69.8%) and Quebec (60.8%) in August (not seasonally adjusted).

Nationally, on a year-over-year basis, the employment rate for youth aged 15 to 24 was down by 7.6 percentage points to 47.2% for returning students, compared with a 10.1 percentage point decrease to 69.5% for non-student youth (not seasonally adjusted).

For youth aged 20 to 24, the year-over-year decline in the employment rate was slightly higher for returning students (-12.1 percentage points to 56.7%) than for non-students (-10.1 percentage points to 71.3%) in August (not seasonally adjusted).

For both returning students and non-student youth, the unemployment rate was higher among visible minority youth than among others. The unemployment rate among returning students who belonged to groups designated as visible minorities was 35.3%, compared with 19.9% (not seasonally adjusted) for returning students who were not members of a population group designated as a visible minority and did not identify as Indigenous.

For non-student youth, those belonging to groups designated as visible minorities had an unemployment rate of 28.2%, compared with 16.3% for non-student youth who were not members of a population group designated as a visible minority and did not identify as Indigenous (not seasonally adjusted).

Almost one-quarter (24.8%) of returning students aged 18 to 24 reported receiving the Canada Emergency Student Benefit (CESB) in the previous four weeks, a slight decline from July (-2.7 percentage points). A further 12.7% received the Canada Emergency Response Benefit (CERB), down 4.8 percentage points from July.

Youth unemployment rate remains high, especially for young men

In August, the youth unemployment rate was 23.1%, down from the record high of 29.4% in May. The unemployment rate for male youth (25.6%) continued to be higher than for all other groups, including young women (20.2%). The rates for both young men and young women were approximately double those observed in February. By comparison, during the 2008/2009 recession, the youth unemployment rate peaked at 16.4%.

Unemployment higher among visible minority youth

The unemployment rate for youth who were members of population groups designated as visible minorities was 32.3% (not seasonally adjusted). This was nearly 15 percentage points higher than the rate for youth who were not Indigenous or a member of a group designated as a visible minority (18.0%).

Compared with youth who did not identify as Indigenous and were not a visible minority, visible minority youth were more likely to be returning students (66.3% versus 54.6%) and to live in Ontario (51.4% versus 39.1%). Among unemployed youth who last worked in the past 12 months, more than one-third (37.5%, not adjusted for seasonality) last worked in either retail trade or accommodation and food services, with no notable difference between visible minority and other youth.

More than one-third of Filipino and Latin American Canadians live in a household facing financial difficulties

The share of Canadians living in households reporting difficulty meeting necessary expenses was little changed in August at 19.6% and has been relatively unchanged since April.

Among Canadians aged 15 to 69, those who were members of population groups designated as visible minorities were more likely to be in a household which experienced financial difficulties in August. This may reflect differences in the ongoing impacts of the COVID-19 economic shutdown and longer-standing differences in financial security across groups.

Over one-third of Filipino (35.2%) and Latin American (33.7%) Canadians reported living in a household experiencing financial difficulties, while 28.2% of Black Canadians and just over one-fifth of Chinese Canadians (22.7%) did so.

By way of comparison, 15.9% of Canadians aged 15 to 69 who were not a visible minority and did not identify as Indigenous, lived in a household which experienced financial difficulties.

Those experiencing financial pressures and difficulty returning to work account for increasing share of CERB beneficiaries

As of the LFS reference week (August 9 to 15), 16.1% of Canadians aged 15 to 69 reported receiving either the CERB, the CESB or regular Employment Insurance benefits in the four weeks preceding their LFS interview. This was down 2.3 percentage points from July.

Among people aged 15 to 69 who had received a CERB payment in the previous four weeks, more than one-third (37.7%) lived in a household reporting difficulty meeting necessary expenses, up 4.4 percentage points from July.

Recent CERB recipients were also less likely to be employed in August. About half (51.5%) were employed during the LFS reference week, down 4.7 percentage points from July.

Among recent CERB recipients who were not employed, the share who were looking for work increased 6.9 percentage points to 47.5%, while the share of those on temporary lay-off or out of the labour force declined.

Looking ahead as children return to schooling

In recent months, the LFS has reported notable differences between core-aged mothers and fathers in the extent to which employment has returned to pre-COVID levels. In July, for example, employment was furthest from February levels among mothers whose youngest child was aged 6 to 17.

The patterns reported in July remained stable in August, as employment was little changed for both core-aged fathers and mothers with children under 18 (not seasonally adjusted). Employment among fathers was at 99.8% of February levels, compared with 94.8% for mothers. This 5.0 percentage point gap may be attributable to several factors, some of which are reflective of normal seasonal variations.

Employment among mothers, for example, typically rebounds in September after falling in the summer months. As a prelude to this rebound, the number of mothers who are unemployed but have arrangements to start a new job within four weeks typically spikes in August. This seasonal pattern is largely driven by summer drops in employment in the educational services industry, which employs more mothers than any other industry except healthcare and social assistance.

When people with arrangements to start new jobs are added to August employment, the gap between mothers and fathers in the degree to which labour market conditions have recovered since February is reduced from 5.0 to 3.2 percentage points. This suggests that the employment recovery gap might narrow somewhat in September, as many mothers return to work in the education services industry.

Teleworking mothers of young children remain concerned about childcare

The extent to which mothers return to work in September will be the result of a number of factors, including the ability of families to balance COVID-related challenges and adaptations being made in both schools and workplaces.

Among parents who have adapted to the COVID-19 economic shutdown by beginning to work from home, just under one-third (32.9%) were concerned in August that a return to their normal work location would bring challenges in terms of childcare or caregiving. This was down slightly from July (-2.7 percentage points). The share citing this concern remained highest among teleworking mothers whose youngest child was less than 6 years old (51.1%).

The LFS results for September and October will shed light on how the return to school, and the ongoing return to regular workplaces, is impacting the employment situation of mothers and fathers.

Sustainable Development Goals

On January 1, 2016, the world officially began implementation of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development—the United Nations' transformative plan of action that addresses urgent global challenges over the next 15 years. The plan is based on 17 specific sustainable development goals.

The Labour Force Survey is an example of how Statistics Canada supports the reporting on the global sustainable development goals. This release will be used to help measure the following goals:

Note to readers

The Labour Force Survey (LFS) estimates for August are for the week of August 9 to August 15.

The LFS estimates are based on a sample and are therefore subject to sampling variability. As a result, monthly estimates will show more variability than trends observed over longer time periods. For more information, see "Interpreting Monthly Changes in Employment from the Labour Force Survey".

This analysis focuses on differences between estimates that are statistically significant at the 68% confidence level.

The LFS estimates are the first in a series of labour market indicators released by Statistics Canada, which includes indicators from programs such as the Survey of Employment, Payrolls and Hours (SEPH); Employment Insurance Statistics; and the Job Vacancy and Wage Survey. For more information on the conceptual differences between employment measures from the LFS and those from the SEPH, refer to section 8 of the Guide to the Labour Force Survey (71-543-G).

LFS estimates at the Canada level do not include the territories.

Since March 2020, all face-to-face interviews were replaced by telephone interviews to protect the health of both interviewers and respondents. In addition, all telephone interviews were conducted by interviewers working from their home and none were done from Statistics Canada's call centres. As in June and July, approximately 40,000 interviews were completed in August.

The distribution of LFS interviews in August 2020 compared with July 2020, was as follows:

Personal face-to-face interviews

• July 2020 0.0%

• August 2020 0.0%

Telephone interviews – from call centres

• July 2020 0.0%

• August 2020 0.0%

Telephone interviews – from interviewer homes

• July 2020 69.4%

• August 2020 69.2%

Online interviews

• July 2020 30.6%

• August 2020 30.8%

The employment rate is the number of employed people as a percentage of the population aged 15 and older. The rate for a particular group (for example, youths aged 15 to 24) is the number employed in that group as a percentage of the population for that group.

The unemployment rate is the number of unemployed people as a percentage of the labour force (employed and unemployed).

The participation rate is the number of employed and unemployed people as a percentage of the population aged 15 and older.

Full-time employment consists of persons who usually work 30 hours or more per week at their main or only job.

Part-time employment consists of persons who usually work less than 30 hours per week at their main or only job.

Total hours worked refers to the number of hours actually worked at the main job by the respondent during the reference week, including paid and unpaid hours. These hours reflect temporary decreases or increases in work hours (for example, hours lost due to illness, vacation, holidays or weather; or more hours worked due to overtime).

In general, month-to-month or year-to-year changes in the number of people employed in an age group reflect the net effect of two factors: (1) the number of people who changed employment status between reference periods, and (2) the number of employed people who entered or left the age group (including through aging, death or migration) between reference periods.

Supplementary indicators used in August 2020 analysis

To continue capturing the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on the labour market, the supplementary indicators used in March and April have been slightly adapted since then. Therefore, the May to August supplementary indicators are not directly comparable to the supplementary indicators published in April and March 2020.

Employed, worked zero hours includes employees and self-employed who were absent from work all week, but excludes people who have been away for reasons such as 'vacation,' 'maternity,' 'seasonal business' and 'labour dispute.'

Employed, worked less than half of their usual hours includes both employees and self-employed, where only employees were asked to provide a reason for the absence. This excludes reasons for absence such as 'vacation,' 'labour dispute,' 'maternity,' 'holiday,' and 'weather.' Also excludes those who were away all week.

Not in labour force but wanted work includes persons who were neither employed, nor unemployed during the reference period and wanted work, but did not search for reasons such as 'waiting for recall (to former job),' 'waiting for replies from employers,' 'believes no work available (in area, or suited to skills),' 'long-term future start,' and 'other.'

Unemployed, job searchers were without work, but had looked for work in the past four weeks ending with the reference period and were available for work.

Unemployed, temporary layoff or future starts were on temporary layoff due to business conditions, with an expectation of recall, and were available for work; or were without work, but had a job to start within four weeks from the reference period and were available for work (don't need to have looked for work during the four weeks ending with the reference week).

Labour underutilization rate (specific definition to measure the COVID-19 impact) combines all those who were unemployed with those who were not in the labour force but wanted a job and did not look for one; as well as those who remained employed but lost all or the majority of their usual work hours for reasons likely related to COVID-19 as a proportion of the potential labour force.

Potential labour force (specific definition to measure the COVID-19 impact) includes people in the labour force (all employed and unemployed people), and people not in the labour force who wanted a job but didn't search for reasons such as 'waiting for recall (to former job),' 'waiting for replies from employers,' 'believes no work available (in area, or suited to skills),' 'long-term future start,' and 'other.'

Time-related underemployment rate combines people who remained employed but lost all or the majority of their usual work hours as a proportion of all employed people.

New information on population groups

Beginning in July, the LFS includes a question asking respondents to report the population groups to which they belong. Possible responses, which are the same as in the 2016 Census, include:

• White

• South Asian e.g., East Indian, Pakistani, Sri Lankan

• Chinese

• Black

• Filipino

• Arab

• Latin American

• Southeast Asian e.g., Vietnamese, Cambodian, Laotian, Thai

• West Asian e.g., Iranian, Afghan

• Korean

• Other

For LFS records interviewed before July, population group characteristics were assigned using an experimental sample matching data integration method. This involved directly integrating LFS and census information for approximately 20% of LFS records. For the remaining 80%, population group characteristics were assigned using information available at the population level from both LFS and census. Further development of this method will continue in the coming months.

According to the Employment Equity Act, visible minorities are "persons, other than Aboriginal peoples, who are non-Caucasian in race or non-white in colour." In the text, data for the population who identify as Aboriginals are analyzed separately. The remaining category is described as "people not designated as visible minorities" or "people who are not a visible minority."

Seasonal adjustment

Unless otherwise stated, this release presents seasonally adjusted estimates, which facilitate comparisons by removing the effects of seasonal variations. For more information on seasonal adjustment, see Seasonally adjusted data – Frequently asked questions.

The seasonally adjusted data for retail trade and wholesale trade industries presented here are not published in other public LFS tables. A seasonally adjusted series is published for the combined industry classification (wholesale and retail trade).

Next release

The next release of the LFS will be on October 9.

Products

More information about the concepts and use of the Labour Force Survey is available online in the Guide to the Labour Force Survey (71-543-G).

The product "Labour Force Survey in brief: Interactive app" (14200001) is also available. This interactive visualization application provides seasonally adjusted estimates available by province, sex, age group and industry. Historical estimates going back five years are also included for monthly employment changes and unemployment rates. The interactive application allows users to quickly and easily explore and personalize the information presented. Combine multiple provinces, sexes and age groups to create your own labour market domains of interest.

The product "Labour Market Indicators, by province and census metropolitan area, seasonally adjusted" (71-607-X) is also available. This interactive dashboard provides easy, customizable access to key labour market indicators. Users can now configure an interactive map and chart showing labour force characteristics at the national, provincial or census metropolitan area level.

The product "Labour Market Indicators, by province, territory and economic region, unadjusted for seasonality" (71-607-X) is also available. This dynamic web application provides access to Statistics Canada's labour market indicators for Canada, by province, territory and economic region and allows users to view a snapshot of key labour market indicators, observe geographical rankings for each indicator using an interactive map and table, and easily copy data into other programs.

Contact information

For more information, or to enquire about the concepts, methods or data quality of this release, contact us (toll-free 1-800-263-1136; 514-283-8300; STATCAN.infostats-infostats.STATCAN@canada.ca) or Media Relations (613-951-4636; STATCAN.mediahotline-ligneinfomedias.STATCAN@canada.ca).

- Date modified: