by Jane Y. Polsky and Didier Garriguet

DOI: https://www.doi.org/10.25318/82-003-x202200200002-eng

Correction Notice

In the article “Household food insecurity in Canada early in the COVID-19 pandemic” published on February 16, 2022, an error was found in figure 2.

The following correction has been made:

In figure 2, the provinces of New Brunswick and Nova Scotia were reversed.

The data tables for Figures 1 and 2 were updated to include confidence intervals.

Abstract

Background

Food insecurity linked to insufficient income is an important determinant of health. Whether the COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated levels of food insecurity in Canada, particularly among vulnerable groups, is unclear. This study estimated the proportion of Canadians reporting experience of household food insecurity six to nine months into the COVID-19 pandemic, and drew comparisons with pre-pandemic levels.

Data and methods

Data on household food security status during the pandemic came from the population-based cross-sectional Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS) collected from September to December 2020. Analyses were based on 26,831 respondents aged 12 and older residing in the 10 provinces. The Household Food Security Survey Module was used to categorize respondents’ household food security status within the previous 12 months as food secure or marginally, moderately or severely insecure. The percentage of Canadians reporting some experience of household food insecurity was estimated for the overall population and for various sociodemographic groups. T-tests were used to draw comparisons with pre-pandemic rates from the 2017/2018 CCHS.

Results

In fall 2020, 9.6% of Canadians reported having experienced some level of food insecurity in their household in the prior 12 months, which is lower than the estimate of 12.6% from 2017/2018. Overall estimates were also lower in fall 2020 when examined within levels of household food insecurity (i.e., marginal, moderate or severe). The percentage of Canadians reporting experience of household food insecurity was either unchanged or lower than in 2017/2018 among sociodemographic groups vulnerable to experiencing income-related food insecurity, including renters and those with lower levels of education.

Interpretation

During the second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in fall 2020, about 1 in 10 Canadians aged 12 and older reported experience of food insecurity in their household in the previous 12 months. This proportion was lower compared with 2017/2018, both overall and among several groups at higher risk of food insecurity. Monitoring household food insecurity will continue to be important during the COVID-19 pandemic and throughout the years of recovery ahead.

Keywords

Canadian Community Health Survey, food insecurity, food security, COVID-19 pandemic, inequalities

Authors

Jane Y. Polsky (jane.polsky@statcan.gc.ca) and Didier Garriguet are with the Health Analysis Division, Analytical Studies and Modelling Branch, Statistics Canada, Ottawa.

What is already known on this subject?

- Household food insecurity is a well-established determinant of health and is tightly linked with financial hardship.

- The COVID-19 pandemic has had a profound impact on the financial status of millions of Canadians.

- It is unclear whether the COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated levels of household food insecurity in Canada during the pandemic, particularly among vulnerable groups.

What does this study add?

- During the second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in fall 2020, about 1 in 10 Canadians (9.6%) aged 12 and older living in the 10 provinces reported experience of food insecurity in their household within the prior 12 months.

- This proportion was lower than the approximately one in eight Canadians (12.6%) who reported an analogous experience in the pre-pandemic period of 2017/2018.

- Among sociodemographic groups vulnerable to experiencing income-related food insecurity, including renters and those with lower levels of education, the proportion of people in food-insecure households was either unchanged or lower in fall 2020 compared with 2017/2018.

End of text box

Introduction

Food insecurity, or insecure or inadequate access to food because of financial constraints, is a potent determinant of health in Canada and other high-income nations.Note 1Note 2Note 3 Food insecurity has been shown to be consistently associated with a range of physical and mental health problems, and with increased health care costs for adults.Note 4Note 5Note 6Note 7Note 8Note 9 Certain groups are more vulnerable to food insecurity, including households with children, lone-parent families and individuals whose main source of income is government assistance.Note 10Note 11Note 12 In 2017/2018, the last time that household food security status was assessed at the national level as part of the Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS), 12.7% of Canadian households, or 1.8 million households, reported having experienced some level of food insecurity during the previous 12 months.Note 11

Since mid-March 2020, when the World Health Organization declared the novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) a pandemic, millions of Canadians have been faced with financial uncertainty, as public health measures directed the closure of workplaces and businesses to limit the spread of the virus. This led to immediate concerns about potentially rising levels of food insecurity and surging demand at food banks and other food charities.Note 13Note 14 Shortly after the onset of the pandemic, the Canadian government began to roll out a series of financial relief measures for individuals, households and businesses affected by the economic shutdowns.Note 15 Both in 2020 and again in 2021, the federal government also allocated emergency funding to national food assistance organizations to help improve access to food for people experiencing food insecurity in Canada because of the pandemic.Note 16Note 17

Whether the COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated levels of household food insecurity in Canada at various points during the pandemic, particularly among vulnerable groups, remains to be determined. A national-level online survey from the early pandemic period (May 2020) estimated that nearly one in seven Canadians (14.6%) reported some experience of food insecurity in their household in the previous 30 days.Note 18 Higher rates were documented among Canadians living in households with children and among those absent from work because of COVID-19 during the previous week. However, the ability to compare with pre-pandemic levels was highly limited because of differences in the survey designs, sampling frames and scales used to measure household food insecurity.

After halting operations because of the pandemic in mid-March 2020, the CCHS resumed data collection in September through December. The survey administered the 18-item Household Food Security Survey Module, a scale that has been routinely employed to monitor household food insecurity in Canada,Note 1 to respondents from all 10 provinces. Data from this survey provide, for the first time, an opportunity to estimate the prevalence of household food insecurity in all 10 provinces during the COVID-19 pandemic, and to draw robust comparisons with pre-pandemic rates. The objectives of this study were thus to estimate the proportion of Canadians reporting experience of food insecurity in their household six to nine months into the pandemic for the overall population and for various sociodemographic subgroups, and to provide comparisons with pre-pandemic levels.

Methods

Data sources

This study predominantly relied on two Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS) cycles to estimate pre-pandemic rates of food insecurity and rates during the pandemic: the annual component 2017/2018 cycle (before the pandemic)Note 19 and the fall 2020 September-to-December cycle (during the second wave of the pandemic; sub-annual file with the Canadian Health Survey on Seniors oversample).Note 20 Because only data for the 10 Canadian provinces were available from the 2020 cycle, only the provincial-level data from the 2017/2018 dataset were included in this study. In addition, the 2019 CCHS cycle contained data on household food security status for all provinces except British Columbia (which had opted out of the Household Food Security Survey Module) and was used to generate provincial-level estimates only.

The cross-sectional CCHS collects information about the health status, health care utilization and health determinants for the Canadian population aged 12 years and older. Excluded from the survey’s coverage are people living on reserves and other Indigenous settlements in the provinces, full-time members of the Canadian Armed Forces, youth aged 12 to 17 living in foster homes, the institutionalized population, and residents of certain remote regions. Together, these exclusions represent less than 3% of the Canadian population aged 12 and older.

Trained interviewers conducted CCHS interviews using computer-assisted interviewing software. For the 2017/2018 cycle, 87.2% of interviews were conducted via telephone and 12.1% in person.Note 19 For the fall 2020 cycle, all interviews were conducted via telephone.Note 20 When the selected respondent was 12 to 17 years of age, a more knowledgeable person in the household completed questions about household income and food security status. The overall response rate was 60.8% for the 2017/2018 cycle and 24.6% for the fall 2020 cycle. After 1,697 observations with missing values on household food security status were removed, the final analytic sample for the pre-pandemic 2017/2018 cycle was 109,332 respondents, representing over 30.5 million Canadians living in the 10 provinces. For the during-pandemic fall 2020 cycle, removal of 442 records with missing values yielded an analytic sample size of 26,831 respondents, representing nearly 31.8 million Canadians.

Definitions

Household food security status

Household food security status was assessed using the Household Food Security Survey Module (HFSSM), a standardized, validated, 18-item scale of food insecurity severity included in the Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS) since 2005.Note 1 Questions capture experiences of food insecurity within the previous 12 months and range from worrying about running out of food before there is money to buy more, to cutting the size of meals or skipping meals, to going a whole day without eating. The full wording of each question explicitly asks if the conditions were “because there wasn’t enough money for food.” Answers were coded using previously published methodologyNote 21 to capture four types of situations:

- Food secure: no indication of difficulty with income-related food access.

- Marginally food insecure: exactly one indication of difficulty with income-related food access, such as worry about running out of food or limited food selection.

- Moderately food insecure: indication of compromise in quality and/or quantity of food consumed.

- Severely food insecure: indication of reduced food intake and disrupted eating patterns.

For analyses using a binary version of food security status (i.e., food secure or food insecure), food insecurity was defined as marginal, moderate or severe.

Sociodemographic characteristics

Because the HFSSM assesses food security status of the entire household, this analysis primarily focused on sociodemographic characteristics at the household level. These included household composition (with children defined as those younger than 18 years), highest level of education achieved among all members of the household, dwelling ownership status, province of residence, and urbanicity (population centre or rural residence). Before-tax household income and the main source of household income were ascertained for the previous calendar year (e.g., in 2020, respondents reported their 2019 income). To improve the quality of income data, household income was derived from tax-linked data or imputed by Statistics Canada for 83.4% of respondents in the 2017/2018 CCHS and 96.6% in the fall 2020 CCHS. Household income was divided by the square root of the number of household members to adjust for household size.Note 12 Indigenous identity (First Nations, Métis, or Inuk or Inuit), visible minority status and immigrant status were determined at the respondent level. The concept of “visible minority” is based on the Employment Equity Act, which defines visible minorities as “persons, other than Aboriginal peoples, who are non-Caucasian in race or non-white in colour.” The number of years since immigration was ascertained only for landed immigrants and was used to categorize recent immigrants (less than five years) and longer-term immigrants (five years or more) to Canada. All other immigrants (e.g., non-permanent residents) were placed in a separate category.

Labour force participation

In both the 2017/2018 and the fall 2020 cycles, respondents aged 15 to 75 were asked about their labour force participation in the week before the interview. Both employed and self-employed respondents who were in the labour force were further asked to specify the type of business, industry or service. These answers were coded to the industry group according to the 2017 North American Industry Classification System at the two-digit level. Industry group was not available for respondents who indicated they had a job in the previous week but were absent because of a temporary layoff or seasonal layoff, or because their job was casual and there were no hours. Additionally, only respondents to the fall 2020 CCHS were asked whether they worked from home as a precaution against COVID-19. The estimation of food insecurity levels by work-from-home status in fall 2020 was limited to those respondents who had worked at a job or business in the previous week (8,868 respondents, representing 16.7 million Canadians).

Analytic techniques

Weighted frequencies and cross-tabulations were generated to examine the percentage of Canadians reporting experiences of household food security or insecurity overall and by province and sociodemographic characteristics. T-tests were used to test for differences between before the pandemic and during the pandemic. All analyses applied survey weights to account for the complex sampling design and the probability of non-response and to maintain population representativeness. The present analyses applied person-level weights to reflect the number of Canadians aged 12 and older who reported experiences of food security or insecurity in their household. Bootstrap weights provided with each survey cycle were used to calculate robust standard errors and coefficients of variation. All analyses were conducted in SAS 9.4 and SAS-callable SUDAAN 11.0. Statistical significance was assessed at the 0.05 alpha level.

Results

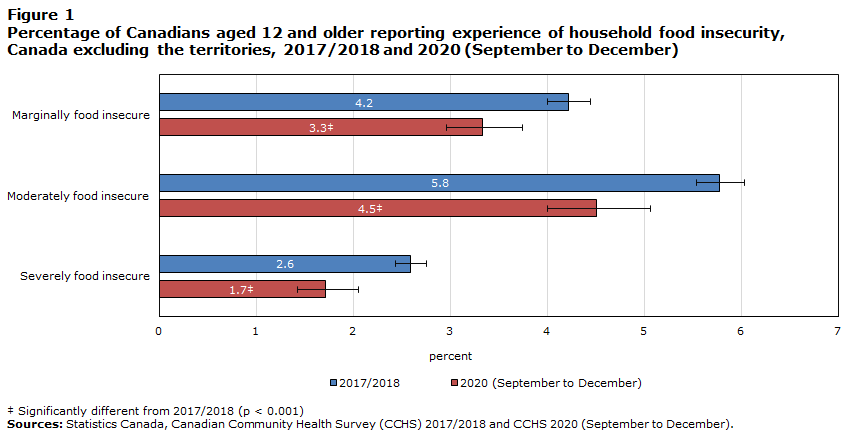

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, in 2017/2018, 87.4% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 87.1% to 87.8%) of Canadians aged 12 and older were living in households classified, according to the Household Food Security Survey Module (HFSSM), as food secure in the prior 12 months. Six to nine months into the pandemic, in the fall of 2020, this proportion increased to 90.4% (95% CI: 89.7% to 91.1%; p-value for comparison < 0.0001). Conversely, the proportion of Canadians in food-insecure households decreased from 12.6% (95% CI: 12.2% to 12.9%) before the pandemic to 9.6% (95% CI: 8.9% to 10.3%; p < 0.0001) during the pandemic. This decrease was significant within each category of food insecurity (i.e., marginal, moderate or severe) in the overall population (Figure 1).

Data table for Figure 1

| 2017/2018 | 2020 (September to December) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | 95% confidence interval | Estimate | 95% confidence interval | |||

| from | to | from | to | |||

| Severely food insecure | 2.6 | 2.4 | 2.8 | 1.7Data Table Figure 1 Note ‡ | 1.4 | 2.1 |

| Moderately food insecure | 5.8 | 5.5 | 6.0 | 4.5Data Table Figure 1 Note ‡ | 4.0 | 5.1 |

| Marginally food insecure | 4.2 | 4.0 | 4.4 | 3.3Data Table Figure 1 Note ‡ | 3.0 | 3.7 |

|

||||||

The 2019 Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS) administered the HFSSM to respondents from all provinces except British Columbia, making it possible to generate estimates for nine provinces for the year preceding the pandemic, in addition to the main pre-pandemic estimates (2017/2018) and estimates from during the pandemic (Figure 2). In 2019, the proportion of Canadians reporting experience of food insecurity in their household, by province, remained largely unchanged compared with 2017/2018. The exceptions were Ontario and Quebec, where rates decreased, particularly for Ontario (from 13.1% in 2017/2018 to 9.9% in 2019). A comparison of estimates from 2017/2018 with estimates from fall 2020 for all 10 provinces revealed significant decreases in the proportions of Canadians in food-insecure households for five provinces (Quebec, Ontario, Manitoba, Saskatchewan and British Columbia).

Data table for Figure 2

| Estimate | 95% confidence interval | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| from | to | ||

| 2017/2018 | |||

| B.C. | 12.5 | 11.7 | 13.4 |

| Alta. | 13.4 | 12.5 | 14.3 |

| Sask. | 14.2 | 12.8 | 15.6 |

| Man. | 13.3 | 12.1 | 14.7 |

| Ont. | 13.1 | 12.5 | 13.8 |

| Que. | 10.8 | 10.1 | 11.4 |

| N.B. | 12.8 | 11.3 | 14.4 |

| N.S. | 14.0 | 12.7 | 15.4 |

| P.E.I. | 13.9 | 12.1 | 15.9 |

| N.L. | 13.3 | 11.8 | 15.0 |

| 2019 | |||

| B.C. | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | .... |

| Alta. | 14.0 | 12.6 | 15.5 |

| Sask. | 13.5 | 11.4 | 15.9 |

| Man. | 11.7 | 9.7 | 14.0 |

| Ont. | 9.9Data Table Figure 2 Note ‡ | 9.2 | 10.6 |

| Que. | 9.4Data Table Figure 2 Note ‡ | 8.7 | 10.3 |

| N.B. | 13.4 | 11.3 | 15.9 |

| N.S. | 16.2 | 14.1 | 18.6 |

| P.E.I. | 15.0 | 12.3 | 18.2 |

| N.L. | 12.1 | 9.9 | 14.8 |

| 2020 (September to December) | |||

| B.C. | 8.9Data Table Figure 2 Note ‡ | 7.2 | 10.9 |

| Alta. | 11.8 | 9.9 | 14.2 |

| Sask. | 7.5Data Table Figure 2 Note ‡ | 5.6 | 10.0 |

| Man. | 9.3Data Table Figure 2 Note ‡ | 7.2 | 11.9 |

| Ont. | 10.3Data Table Figure 2 Note ‡ | 9.1 | 11.7 |

| Que. | 7.0Data Table Figure 2 Note ‡ | 5.8 | 8.5 |

| N.B. | 11.7Note E: Use with caution | 8.4 | 16.0 |

| N.S. | 12.8 | 9.7 | 16.8 |

| P.E.I. | 10.6Note E: Use with caution | 6.4 | 17.1 |

| N.L. | 11.0Note E: Use with caution | 7.7 | 15.7 |

|

... not applicable E use with caution

Sources: Statistics Canada, Canadian Community Health Survey, 2017/2018, 2019 and 2020 (September to December). |

|||

Table 1 presents the distribution of Canadians by sociodemographic characteristics and household food security status. Both before and during the pandemic, those reporting higher levels of household food insecurity were younger, with less than a high school education, living in lone-parent-led households, living in households reliant on social assistance or employment insurance as their primary source of income, those who rented rather than owned their dwelling and who identify as Indigenous or Black. Compared with the pre-pandemic period, levels of household food insecurity in fall 2020 were somewhat lower among several vulnerable groups, including people with Indigenous identity, households with children, lone-parent households, renters, and those with lower education levels. For example, among individuals living in households with less than a high school education, the proportion classified as food secure increased significantly, from 78.8% in 2017/2018 to 85.2% during the pandemic, while the proportion classified as moderately food insecure decreased from 9.5% to 5.9%. Few or no significant changes in household food security status were observed for people belonging to groups designated as visible minorities; immigrants to Canada; and individuals in households whose main source of income in 2019 was social assistance, employment insurance, or other or none.

The proportion of Canadians aged 15 to 75 experiencing household food insecurity according to working status in the week before the interview is shown in Table 2. Compared with 2017/2018, the prevalence of food insecurity was lower by over three percentage points among those who had worked at a job or business, and among those who did not have a job in fall 2020. When examined by industry group, the proportion of Canadians reporting household food insecurity was either unchanged or lower during the pandemic. Notable decreases were seen among Canadians working in retail trade (from 15.3% food insecure before the pandemic to 9.6% during the pandemic), accommodation and food services (from 19.6% to 11.9%), and other services (except public administration; from 14.2% to 8.7%).

| 2017/2018 | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Food secure | Marginally insecure | Moderately insecure | Severely insecure | |||||||||

| Estimate | 95% confidence interval | Estimate | 95% confidence interval | Estimate | 95% confidence interval | Estimate | 95% confidence interval | |||||

| from | to | from | to | from | to | from | to | |||||

| Sex (%) | ||||||||||||

| Male | 88.8 | 88.3 | 89.3 | 3.8 | 3.5 | 4.1 | 5.0 | 4.7 | 5.4 | 2.3 | 2.1 | 2.6 |

| Female | 86.0 | 85.5 | 86.5 | 4.6 | 4.3 | 5.0 | 6.5 | 6.2 | 6.9 | 2.8 | 2.6 | 3.1 |

| Age group (%) | ||||||||||||

| 12 to 17 | 79.4 | 78.0 | 80.7 | 7.3 | 6.5 | 8.3 | 10.0 | 9.0 | 11.1 | 3.3 | 2.8 | 3.9 |

| 18 to 34 | 84.4 | 83.6 | 85.2 | 5.3 | 4.8 | 5.8 | 7.1 | 6.5 | 7.7 | 3.3 | 2.9 | 3.6 |

| 35 to 49 | 85.6 | 84.8 | 86.4 | 4.6 | 4.1 | 5.0 | 6.9 | 6.3 | 7.4 | 3.0 | 2.7 | 3.3 |

| 50 to 64 | 89.4 | 88.8 | 90.0 | 3.2 | 2.8 | 3.7 | 4.8 | 4.3 | 5.3 | 2.6 | 2.3 | 2.9 |

| 65 and older | 94.1 | 93.6 | 94.5 | 2.5 | 2.2 | 2.8 | 2.5 | 2.2 | 2.8 | 1.0 | 0.8 | 1.2 |

| Indigenous identity (%) | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 72.8 | 70.8 | 74.6 | 5.2 | 4.5 | 6.2 | 13.3 | 11.9 | 14.8 | 8.7 | 7.5 | 10.1 |

| No | 88.0 | 87.7 | 88.4 | 4.2 | 3.9 | 4.4 | 5.5 | 5.2 | 5.7 | 2.3 | 2.2 | 2.5 |

| Visible minority status (%) | ||||||||||||

| South Asian | 84.1 | 81.9 | 86.2 | 6.7 | 5.3 | 8.5 | 7.9 | 6.4 | 9.7 | 1.2Note E: Use with caution | 0.7 | 2.1 |

| Chinese | 93.9 | 92.5 | 95.1 | 2.8 | 2.2 | 3.7 | 2.9Note E: Use with caution | 2.2 | 4.0 | X | X | X |

| Black | 70.8 | 67.2 | 74.2 | 6.3 | 4.8 | 8.2 | 16.0 | 13.5 | 19.0 | 6.9 | 5.2 | 8.9 |

| Filipino | 77.1 | 72.9 | 80.8 | 11.3 | 8.6 | 14.8 | 10.2 | 8.0 | 13.0 | X | X | X |

| Latin American | 78.0 | 73.9 | 81.7 | 8.8 | 6.5 | 11.7 | 9.2Note E: Use with caution | 6.8 | 12.4 | 4.0Note E: Use with caution | 2.6 | 6.0 |

| Arab | 79.7 | 75.1 | 83.6 | 6.2Note E: Use with caution | 4.2 | 9.1 | 12.1Note E: Use with caution | 9.0 | 16.3 | 1.9Note E: Use with caution | 1.0 | 3.6 |

| Southeast Asian | 87.8 | 83.8 | 91.0 | 4.6Note E: Use with caution | 2.8 | 7.6 | 6.6Note E: Use with caution | 4.4 | 10.0 | X | X | X |

| West Asian | 77.1 | 69.7 | 83.2 | 5.6Note E: Use with caution | 2.9 | 10.7 | 11.9Note E: Use with caution | 7.5 | 18.3 | X | X | X |

| Korean | 92.5 | 87.4 | 95.6 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Japanese | 85.4 | 76.5 | 91.3 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Other visible minority | 83.9 | 80.0 | 87.3 | 8.4Note E: Use with caution | 5.6 | 12.3 | 6.0Note E: Use with caution | 4.4 | 8.1 | 1.7Note E: Use with caution | 1.0 | 2.9 |

| Multiple visible minorities | 86.6 | 84.1 | 88.7 | 4.4Note E: Use with caution | 3.2 | 6.0 | 6.6 | 5.2 | 8.4 | 2.4Note E: Use with caution | 1.6 | 3.7 |

| Non-visible minority (White) | 89.4 | 89.1 | 89.7 | 3.5 | 3.3 | 3.8 | 4.6 | 4.4 | 4.9 | 2.4 | 2.3 | 2.6 |

| Immigrant status (%) | ||||||||||||

| Non-immigrant | 88.1 | 87.8 | 88.5 | 3.8 | 3.6 | 4.0 | 5.2 | 5.0 | 5.5 | 2.9 | 2.7 | 3.1 |

| Recent immigrant (less than five years) | 81.3 | 78.6 | 83.8 | 6.0 | 4.7 | 7.5 | 11.4 | 9.3 | 13.9 | 1.3Note E: Use with caution | 0.8 | 2.1 |

| Longer-term immigrant (five years or more) | 86.4 | 85.5 | 87.3 | 5.3 | 4.7 | 6.0 | 6.5 | 5.9 | 7.2 | 1.8 | 1.5 | 2.1 |

| Immigrant, other | 83.0 | 79.9 | 85.7 | 6.1Note E: Use with caution | 4.5 | 8.4 | 8.7 | 6.8 | 11.0 | 2.2Note E: Use with caution | 1.4 | 3.6 |

| Household type (%) | ||||||||||||

| Unattached, living alone or with others | 82.5 | 81.7 | 83.3 | 4.7 | 4.3 | 5.2 | 7.2 | 6.7 | 7.7 | 5.5 | 5.1 | 6.0 |

| Couple, no children | 93.7 | 93.2 | 94.1 | 2.6 | 2.3 | 2.8 | 2.5 | 2.2 | 2.7 | 1.3 | 1.1 | 1.5 |

| Couple with children | 86.9 | 86.2 | 87.5 | 4.9 | 4.5 | 5.3 | 6.7 | 6.2 | 7.2 | 1.5 | 1.3 | 1.8 |

| Lone parent | 67.5 | 65.5 | 69.5 | 8.3 | 7.3 | 9.5 | 16.6 | 15.1 | 18.2 | 7.5 | 6.6 | 8.6 |

| Other | 89.3 | 88.3 | 90.2 | 4.0 | 3.4 | 4.7 | 4.9 | 4.3 | 5.6 | 1.9 | 1.5 | 2.2 |

| Household-level education (%) | ||||||||||||

| Less than high school | 78.8 | 77.2 | 80.2 | 5.3 | 4.6 | 6.2 | 9.5 | 8.5 | 10.6 | 6.4 | 5.5 | 7.5 |

| High school | 81.1 | 80.0 | 82.1 | 5.5 | 4.9 | 6.1 | 8.9 | 8.1 | 9.7 | 4.5 | 4.1 | 5.0 |

| Certificate or diploma | 86.0 | 85.4 | 86.6 | 4.8 | 4.5 | 5.1 | 6.4 | 6.0 | 6.8 | 2.8 | 2.6 | 3.1 |

| Bachelor's degree or above | 92.4 | 91.9 | 92.9 | 3.1 | 2.7 | 3.4 | 3.4 | 3.1 | 3.8 | 1.1 | 1.0 | 1.3 |

| Missing | 84.6 | 82.6 | 86.4 | 4.5 | 3.6 | 5.8 | 7.6 | 6.2 | 9.3 | 3.3 | 2.6 | 4.1 |

| Mean household incomeTable 1 Note b ($ ± SE) | 71,210 | ± 673 | Note ...: not applicable | 48,796 | ± 2,736 | Note ...: not applicable | 34,288 | ± 533 | Note ...: not applicable | 31,526 | ± 3,225 | Note ...: not applicable |

| Main source of household income (%) | ||||||||||||

| Wages, salaries, self-employment | 88.1 | 87.7 | 88.5 | 4.4 | 4.2 | 4.7 | 5.5 | 5.3 | 5.8 | 1.9 | 1.8 | 2.1 |

| Seniors' income | 93.7 | 93.1 | 94.2 | 2.2 | 1.9 | 2.6 | 2.7 | 2.4 | 3.0 | 1.4 | 1.2 | 1.7 |

| Employment insurance, workers' compensation | 68.0 | 62.9 | 72.7 | 6.6Note E: Use with caution | 4.4 | 9.7 | 14.7 | 11.2 | 19.0 | 10.7 | 8.4 | 13.7 |

| Social assistance | 40.9 | 37.7 | 44.2 | 9.3 | 7.6 | 11.3 | 26.1 | 23.5 | 28.9 | 23.7 | 21.1 | 26.5 |

| Other or none | 79.4 | 76.8 | 81.7 | 5.6 | 4.5 | 7.0 | 9.5 | 8.0 | 11.1 | 5.6Note E: Use with caution | 4.0 | 7.7 |

| Missing | 86.7 | 84.6 | 88.5 | 3.8Note E: Use with caution | 2.8 | 5.1 | 6.3 | 5.0 | 7.9 | 3.2 | 2.5 | 4.1 |

| Dwelling tenure (%) | ||||||||||||

| Owner | 92.3 | 91.9 | 92.6 | 3.3 | 3.1 | 3.5 | 3.4 | 3.2 | 3.6 | 1.0 | 0.9 | 1.1 |

| Renter | 74.3 | 73.4 | 75.2 | 6.7 | 6.2 | 7.2 | 12.2 | 11.5 | 12.8 | 6.8 | 6.4 | 7.4 |

| Region of residence (%) | ||||||||||||

| Atlantic provinces | 86.6 | 85.7 | 87.4 | 4.1 | 3.7 | 4.6 | 6.3 | 5.8 | 6.9 | 3.0 | 2.6 | 3.4 |

| Quebec | 89.2 | 88.6 | 89.9 | 3.8 | 3.5 | 4.2 | 5.1 | 4.6 | 5.6 | 1.8 | 1.6 | 2.1 |

| Ontario | 86.9 | 86.2 | 87.5 | 4.6 | 4.2 | 5.0 | 5.7 | 5.3 | 6.2 | 2.8 | 2.5 | 3.1 |

| Prairie provinces | 86.5 | 85.8 | 87.2 | 4.1 | 3.7 | 4.5 | 6.6 | 6.1 | 7.1 | 2.8 | 2.5 | 3.1 |

| British Columbia | 87.5 | 86.6 | 88.3 | 4.0 | 3.5 | 4.6 | 5.7 | 5.1 | 6.3 | 2.8 | 2.5 | 3.2 |

| Urbanicity (%) | ||||||||||||

| Population centre | 86.9 | 86.5 | 87.3 | 4.4 | 4.1 | 4.6 | 6.1 | 5.8 | 6.3 | 2.7 | 2.5 | 2.9 |

| Rural | 89.9 | 89.4 | 90.5 | 3.5 | 3.2 | 3.8 | 4.5 | 4.1 | 4.9 | 2.1 | 1.9 | 2.4 |

|

... not applicable E use with caution

‡ significantly different from the corresponding household food security status category in 2017/2018 (p < 0.05) Note: SE = standard error. Sources: Statistics Canada, Canadian Community Health Survey, 2017/2018 and 2020 (September to December). |

||||||||||||

| 2020 (September to December) | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Food secure | Marginally insecure | Moderately insecure | Severely insecure | |||||||||

| Estimate | 95% confidence interval | Estimate | 95% confidence interval | Estimate | 95% confidence interval | Estimate | 95% confidence interval | |||||

| from | to | from | to | from | to | from | to | |||||

| Sex (%) | ||||||||||||

| Male | 91.2Table 1 Note ‡ | 90.1 | 92.2 | 3.2 | 2.7 | 3.9 | 4.3 | 3.5 | 5.2 | 1.3Table 1 Note ‡ | 1.0 | 1.7 |

| Female | 89.8Table 1 Note ‡ | 88.7 | 90.7 | 3.4Table 1 Note ‡ | 2.9 | 4.0 | 4.7Table 1 Note ‡ | 4.0 | 5.5 | 2.1Table 1 Note ‡ | 1.6 | 2.7 |

| Age group (%) | ||||||||||||

| 12 to 17 | 84.2Table 1 Note ‡ | 81.5 | 86.6 | 6.7 | 5.1 | 8.7 | 7.2Table 1 Note ‡ | 5.6 | 9.1 | 2.0Table 1 Note ‡ Note E: Use with caution | 1.2 | 3.2 |

| 18 to 34 | 87.8Table 1 Note ‡ | 85.7 | 89.7 | 3.5Table 1 Note ‡ | 2.7 | 4.5 | 6.2 | 4.9 | 7.8 | 2.5Note E: Use with caution | 1.7 | 3.6 |

| 35 to 49 | 89.4Table 1 Note ‡ | 87.8 | 90.7 | 3.9 | 3.0 | 5.0 | 4.9Table 1 Note ‡ | 3.9 | 6.1 | 1.9Table 1 Note ‡ Note E: Use with caution | 1.3 | 2.5 |

| 50 to 64 | 91.4Table 1 Note ‡ | 89.9 | 92.6 | 3.2 | 2.5 | 4.2 | 3.6 | 2.7 | 4.8 | 1.8Table 1 Note ‡ Note E: Use with caution | 1.3 | 2.4 |

| 65 and older | 96.1Table 1 Note ‡ | 95.5 | 96.6 | 1.5Table 1 Note ‡ | 1.2 | 1.8 | 2.0 | 1.6 | 2.5 | 0.5Table 1 Note ‡ Note E: Use with caution | 0.3 | 0.6 |

| Indigenous identity (%) | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 81.8Table 1 Note ‡ | 77.0 | 85.7 | 2.9Table 1 Note ‡ Note E: Use with caution | 1.8 | 4.9 | 8.5Table 1 Note ‡ Note E: Use with caution | 5.8 | 12.4 | 6.8Note E: Use with caution | 4.3 | 10.4 |

| No | 90.8Table 1 Note ‡ | 90.0 | 91.5 | 3.3Table 1 Note ‡ | 3.0 | 3.8 | 4.3Table 1 Note ‡ | 3.8 | 4.9 | 1.5Table 1 Note ‡ | 1.3 | 1.9 |

| Visible minority status (%) | ||||||||||||

| South Asian | 86.2 | 81.0 | 90.1 | 6.3Note E: Use with caution | 4.1 | 9.8 | 6.8Note E: Use with caution | 3.7 | 11.9 | X | X | X |

| Chinese | 90.4 | 85.7 | 93.7 | 5.7Note E: Use with caution | 3.2 | 10.0 | 3.7Note E: Use with caution | 2.0 | 6.8 | X | X | X |

| Black | 76.0 | 69.2 | 81.6 | 5.8Note E: Use with caution | 3.4 | 9.7 | 15.5Note E: Use with caution | 10.8 | 21.7 | X | X | X |

| Filipino | 74.7 | 65.2 | 82.3 | 8.3Note E: Use with caution | 4.8 | 13.9 | 16.8Note E: Use with caution | 10.4 | 26.0 | X | X | X |

| Latin American | 83.8 | 71.6 | 91.4 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Arab | 75.5 | 62.5 | 85.1 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Southeast Asian | 82.4 | 68.9 | 90.8 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| West Asian | 79.3 | 61.3 | 90.2 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Korean | 82.5 | 59.2 | 93.8 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Japanese | 93.7 | 78.9 | 98.3 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Other visible minority | 92.9 | 55.7 | 99.3 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Multiple visible minorities | 97.5Table 1 Note ‡ | 89.7 | 99.4 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Non-visible minority (White) | 93.0Table 1 Note ‡ | 92.3 | 93.6 | 2.6Table 1 Note ‡ | 2.2 | 3.0 | 2.9Table 1 Note ‡ | 2.5 | 3.3 | 1.6Table 1 Note ‡ | 1.3 | 1.9 |

| Immigrant status (%) | ||||||||||||

| Non-immigrant | 91.7Table 1 Note ‡ | 90.92 | 92.38 | 2.8Table 1 Note ‡ | 2.5 | 3.3 | 3.7Table 1 Note ‡ | 3.2 | 4.3 | 1.8Table 1 Note ‡ | 1.5 | 2.1 |

| Recent immigrant (less than five years) | 76.7 | 68.20 | 83.55 | 7.0Note E: Use with caution | 4.1 | 11.8 | 10.6Note E: Use with caution | 6.5 | 17.0 | X | X | X |

| Longer-term immigrant (five years or more) | 88.5 | 86.47 | 90.23 | 4.6 | 3.5 | 5.9 | 6.2 | 4.8 | 7.9 | 0.8Table 1 Note ‡ Note E: Use with caution | 0.4 | 1.4 |

| Immigrant, other | 86.2 | 80.04 | 90.68 | 3.5Note E: Use with caution | 1.8 | 6.8 | 7.2Note E: Use with caution | 4.0 | 12.4 | X | X | X |

| Household type (%) | ||||||||||||

| Unattached, living alone or with others | 89.2Table 1 Note ‡ | 88.1 | 90.3 | 2.6Table 1 Note ‡ | 2.1 | 3.2 | 4.9Table 1 Note ‡ | 4.2 | 5.7 | 3.3Table 1 Note ‡ | 2.7 | 4.1 |

| Couple, no children | 95.8Table 1 Note ‡ | 94.8 | 96.5 | 1.8Table 1 Note ‡ Note E: Use with caution | 1.3 | 2.6 | 1.7Table 1 Note ‡ Note E: Use with caution | 1.3 | 2.3 | Note F: too unreliable to be published | Note F: too unreliable to be published | Note F: too unreliable to be published |

| Couple with children | 89.6Table 1 Note ‡ | 88.1 | 91.0 | 4.4 | 3.6 | 5.4 | 5.1Table 1 Note ‡ | 4.1 | 6.3 | 0.9Table 1 Note ‡ Note E: Use with caution | 0.6 | 1.4 |

| Lone parent | 72.4 | 67.3 | 76.9 | 8.8 | 6.6 | 11.7 | 10.9Table 1 Note ‡ | 8.5 | 14.0 | 7.9Note E: Use with caution | 4.5 | 13.4 |

| Other | 89.5 | 87.4 | 91.3 | 3.1Note E: Use with caution | 2.3 | 4.3 | 5.6 | 4.2 | 7.5 | 1.7Note E: Use with caution | 1.2 | 2.5 |

| Household-level education (%) | ||||||||||||

| Less than high school | 85.2Table 1 Note ‡ | 81.9 | 88.0 | 3.9Note E: Use with caution | 2.8 | 5.5 | 5.9Table 1 Note ‡ Note E: Use with caution | 4.2 | 8.3 | 4.9Note E: Use with caution | 3.2 | 7.4 |

| High school | 86.1Table 1 Note ‡ | 83.6 | 88.3 | 3.7Table 1 Note ‡ | 2.8 | 4.8 | 6.4Table 1 Note ‡ | 4.9 | 8.3 | 3.8Note E: Use with caution | 2.4 | 5.9 |

| Certificate or diploma | 88.8Table 1 Note ‡ | 87.5 | 90.0 | 3.8Table 1 Note ‡ | 3.1 | 4.5 | 5.3Table 1 Note ‡ | 4.5 | 6.3 | 2.1Table 1 Note ‡ | 1.7 | 2.7 |

| Bachelor's degree or above | 93.9Table 1 Note ‡ | 93.0 | 94.8 | 2.8 | 2.2 | 3.5 | 2.8 | 2.2 | 3.6 | 0.5Table 1 Note ‡ Note E: Use with caution | 0.3 | 0.8 |

| Missing | 84.2 | 76.1 | 89.9 | 3.9Note E: Use with caution | 2.3 | 6.7 | 9.4Note E: Use with caution | 4.8 | 17.5 | X | X | X |

| Mean household incomeTable 1 Note b ($ ± SE) | 78,494Table 1 Note ‡ | ± 1,303 | Note ...: not applicable | 51,472 | ± 2,338 | Note ...: not applicable | 46,399Table 1 Note ‡ | ± 2,264 | Note ...: not applicable | 40,813Table 1 Note ‡ | ± 3,043 | Note ...: not applicable |

| Main source of household income (%) | ||||||||||||

| Wages, salaries, self-employment | 90.7Table 1 Note ‡ | 89.7 | 91.6 | 3.5Table 1 Note ‡ | 3.1 | 4.1 | 4.5Table 1 Note ‡ | 3.8 | 5.2 | 1.3Table 1 Note ‡ | 1.0 | 1.7 |

| Seniors' income | 96.1Table 1 Note ‡ | 95.3 | 96.8 | 1.6Note E: Use with caution | 1.1 | 2.3 | 1.8Table 1 Note ‡ | 1.4 | 2.4 | 0.5Table 1 Note ‡ Note E: Use with caution | 0.3 | 0.8 |

| Employment insurance, workers' compensation | 68.8 | 55.2 | 79.8 | X | X | X | 16.9Note E: Use with caution | 9.5 | 28.4 | X | X | X |

| Social assistance | 47.7 | 37.5 | 58.0 | 7.3Note E: Use with caution | 4.6 | 11.4 | 17.9Note E: Use with caution | 11.3 | 27.2 | 27.1Note E: Use with caution | 18.4 | 38.0 |

| Other or none | 79.7 | 74.5 | 84.1 | 7.9Note E: Use with caution | 5.0 | 12.2 | 8.4Note E: Use with caution | 5.6 | 12.3 | 4.0Note E: Use with caution | 2.6 | 6.2 |

| Missing | 90.7Table 1 Note ‡ | 88.5 | 92.6 | 2.7Note E: Use with caution | 1.8 | 4.2 | 5.1Note E: Use with caution | 3.7 | 6.9 | 1.5Table 1 Note ‡ Note E: Use with caution | 0.8 | 2.7 |

| Dwelling tenure (%) | ||||||||||||

| Owner | 94.1Table 1 Note ‡ | 93.4 | 94.7 | 2.7Table 1 Note ‡ | 2.3 | 3.2 | 2.5Table 1 Note ‡ | 2.1 | 3.0 | 0.7Table 1 Note ‡ Note E: Use with caution | 0.5 | 0.9 |

| Renter | 78.5Table 1 Note ‡ | 76.4 | 80.5 | 5.3Table 1 Note ‡ | 4.4 | 6.4 | 11.0 | 9.4 | 12.8 | 5.2Table 1 Note ‡ | 4.2 | 6.4 |

| Region of residence (%) | ||||||||||||

| Atlantic provinces | 88.0 | 85.7 | 90.0 | 4.3Note E: Use with caution | 3.1 | 5.8 | 5.5 | 4.1 | 7.3 | 2.2Note E: Use with caution | 1.5 | 3.1 |

| Quebec | 93.0Table 1 Note ‡ | 91.5 | 94.2 | 2.6Table 1 Note ‡ Note E: Use with caution | 1.9 | 3.7 | 3.4Table 1 Note ‡ Note E: Use with caution | 2.5 | 4.5 | 1.0Table 1 Note ‡ Note E: Use with caution | 0.6 | 1.6 |

| Ontario | 89.7Table 1 Note ‡ | 88.3 | 90.9 | 3.8 | 3.2 | 4.6 | 4.4Table 1 Note ‡ | 3.6 | 5.4 | 2.1Table 1 Note ‡ Note E: Use with caution | 1.5 | 2.8 |

| Prairie provinces | 89.3Table 1 Note ‡ | 87.8 | 90.7 | 2.9Table 1 Note ‡ | 2.3 | 3.7 | 5.8 | 4.7 | 7.1 | 1.9Table 1 Note ‡ | 1.5 | 2.6 |

| British Columbia | 91.1Table 1 Note ‡ | 89.1 | 92.8 | 3.1Note E: Use with caution | 2.3 | 4.2 | 4.4Note E: Use with caution | 3.1 | 6.2 | 1.4Table 1 Note ‡ Note E: Use with caution | 0.8 | 2.2 |

| Urbanicity (%) | ||||||||||||

| Population centre | 90.0Table 1 Note ‡ | 89.2 | 90.8 | 3.4Table 1 Note ‡ | 3.0 | 3.9 | 4.8Table 1 Note ‡ | 4.2 | 5.4 | 1.8Table 1 Note ‡ | 1.5 | 2.2 |

| Rural | 92.6Table 1 Note ‡ | 91.5 | 93.6 | 3.1 | 2.4 | 3.9 | 3.0Table 1 Note ‡ | 2.4 | 3.8 | 1.3Table 1 Note ‡ Note E: Use with caution | 0.9 | 1.9 |

|

... not applicable E use with caution F too unreliable to be published

Note: SE = standard error. Sources: Statistics Canada, Canadian Community Health Survey, 2017/2018 and 2020 (September to December). |

||||||||||||

| 2017/2018 | 2020 (September to December) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | 95% confidence interval | % | 95% confidence interval | |||

| from | to | from | to | |||

| Working status last week | ||||||

| Worked at a job or business | 11.2 | 10.7 | 11.7 | 7.8Table 2 Note ‡ | 7.0 | 8.8 |

| Had a job but did not work (absent) | 10.3 | 9.0 | 11.7 | 11.4Note E: Use with caution | 8.2 | 15.6 |

| Did not have a job | 16.5 | 15.8 | 17.3 | 13.1Table 2 Note ‡ | 11.8 | 14.6 |

| Industry groupTable 2 Note b | ||||||

| Agriculture and mining | 7.0 | 5.7 | 8.5 | 8.0Note E: Use with caution | 5.1 | 12.2 |

| Construction | 10.7 | 9.3 | 12.4 | 7.5Note E: Use with caution | 4.4 | 12.5 |

| Manufacturing | 11.3 | 10.0 | 12.7 | 9.9Note E: Use with caution | 6.6 | 14.4 |

| Retail trade | 15.3 | 13.7 | 16.9 | 9.6Table 2 Note ‡ Note E: Use with caution | 7.0 | 13.1 |

| Transportation and warehousing | 10.7 | 8.9 | 12.9 | 7.7Note E: Use with caution | 4.4 | 13.1 |

| Finance and insurance | 6.2 | 4.8 | 7.9 | 6.2Note E: Use with caution | 3.4 | 11.0 |

| Real estate and rental and leasing | 9.0Note E: Use with caution | 6.5 | 12.1 | 13.9Note E: Use with caution | 7.1 | 25.6 |

| Professional, scientific and technical services | 6.7 | 5.6 | 8.0 | 7.5Note E: Use with caution | 4.7 | 12.0 |

| Administrative and support, waste management and remediation services | 17.0 | 14.4 | 20.0 | 14.5Note E: Use with caution | 9.1 | 22.3 |

| Educational services | 8.1 | 6.9 | 9.5 | 5.0Table 2 Note ‡ Note E: Use with caution | 3.2 | 7.8 |

| Health care and social assistance | 12.2 | 11.0 | 13.5 | 9.0Table 2 Note ‡ | 6.9 | 11.6 |

| Arts, entertainment and recreation | 11.8 | 9.2 | 15.2 | 9.5Note E: Use with caution | 5.6 | 15.8 |

| Accommodation and food services | 19.6 | 17.3 | 22.1 | 11.9Table 2 Note ‡ Note E: Use with caution | 7.3 | 19.0 |

| Other services (except public administration) | 14.2 | 11.9 | 16.8 | 8.7Table 2 Note ‡ Note E: Use with caution | 5.1 | 14.4 |

| Public administration | 5.7 | 4.5 | 7.3 | 3.4Note E: Use with caution | 1.9 | 6.0 |

| Other (utilities, wholesale trade, information and cultural industries) | 6.4 | 5.3 | 7.7 | 4.9Note E: Use with caution | 2.9 | 8.3 |

E use with caution

|

||||||

In fall 2020, Canadians who had worked from home in the previous week reported lower levels of household food insecurity (5.3%; 95% CI: 4.1% to 6.9%) than those working outside the home (9.5%; 95% CI: 8.3% to 10.8%; p-value < 0.0001).

Discussion

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a profound economic impact on many Canadian households, leading to employment and income losses for many. Food insecurity is tightly linked with household income and financial hardship and is a well-established determinant of health.Note 1Note 2Note 10Note 11 The present study is the first, to the authors’ knowledge, to estimate the proportion of Canadians reporting an experience of food insecurity in their household during the COVID-19 pandemic using the full 18-item questionnaire routinely used to monitor household food security status in Canada, and to draw comparisons with pre-pandemic levels. Results indicate that six to nine months into the pandemic, in fall 2020, about 1 in 10 Canadians (9.6%) aged 12 and older living in the 10 provinces reported experiencing food insecurity in their household within the past 12 months.

This proportion is lower than the approximately one in eight Canadians (12.6%) who reported an analogous experience in 2017/2018, the last period when national-level data on household food security status were collected. Overall estimates were also consistently lower in fall 2020 than in 2017/2018 when examined within categories of food insecurity (i.e., marginal, moderate or severe). When ascertained for various sociodemographic groups, the proportion of people reporting experience of household food insecurity was either unchanged or slightly lower among groups historically vulnerable to experiencing insecure food access because of financial constraints.

Six to nine months into the COVID-19 pandemic, there was some improvement in levels of household food security compared with 2017/2018, both overall and for a number of groups at higher risk of food insecurity. This included younger Canadians, Indigenous people, renters, people living in households with children and those with lower levels of education. Shortly after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in March 2020 and the ensuing labour force disruptions, the federal government rolled out extensive pandemic-related financial assistance benefits to individuals and businesses to alleviate the financial impact of the crisis.Note 15 These benefits included the Canada Emergency Response Benefit (CERB), available to people who had lost their job or were working reduced hours; the Canada Emergency Student Benefit, to assist students; and supplements to the Canada Child Benefit, to provide additional financial support to families with children. In June 2020, for example, over one-quarter (28.3%) of working-age Canadians reported having received some type of federal income assistance since the onset of the pandemic.Note 22 Emerging reports suggest that pandemic relief benefits mitigated the impact of job and income losses for many Canadian households, particularly those with middle and lower income, and likely offset a potential surge in low income because of the pandemic for a large proportion of Canadian households.Note 23Note 24Note 25 This is consistent with findings of this study, given that food insecurity is tightly linked with financial hardship. Additionally, many households reduced overall consumer spending as a result of economic shutdowns and slowdowns during the pandemic.Note 23Note 26 This boost in disposable income may have served as an additional buffer against food insecurity for some households.

The food insecurity trends charted in this study are broadly consistent with evidence from other jurisdictions. In the United States, national-level data indicate that the overall prevalence of household food insecurity (classified as low or very low food security) in 2020 remained unchanged from 10.5% of households in 2019.Note 27 Also in the United States, expanded unemployment benefits were longitudinally associated with significant reductions in food insecurity between April and November 2020 among lower-income people who lost work because of the pandemic.Note 28 Low-income households with children in California also reported decreased levels of very low food security, from 19% in 2019 to 14% one to four months into the COVID-19 shutdown.Note 29 The authors postulated that the rapid rollout of federal and state benefits to financially vulnerable families likely explains the findings.

An analysis of a Quebec cohort is the only previous Canadian study, to the authors’ knowledge, to employ the 18-item Household Food Security Survey Module to estimate any change in levels of household food insecurity during the pandemic.Note 30 This study documented a slight reduction in the percentage of participants reporting moderate to severe food insecurity during the early shutdown months. However, the sample had very low baseline rates of household food insecurity (3.8%), and this challenges the generalizability of findings to vulnerable groups. Furthermore, although data on food bank usage in Canada in 2020 documented a surge in demand in the early weeks of the pandemic, at least half of food banks reported a decrease in usage in the following months.Note 31 It is worth noting that because only a small proportion of food-insecure households access food banks and other types of food charity, often doing so as a means of last resort,Note 7Note 32 charitable food program usage is not a reliable indicator of the scope of food insecurity in Canada.

While this study noted some improvement in household food security levels for a number of sociodemographic groups, it nonetheless documented that a significant portion of Canadians—about 1 in 10, or over 3 million people—were living in a household with some level of food insecurity in fall 2020. Of these, nearly 2 million reported moderate or severe food insecurity, which is linked to more serious health consequences, increased health care utilization and costs, and premature mortality.Note 5Note 8Note 33 Both before and during the pandemic, the main source of household income served as a key marker of food insecurity. The proportion of people reporting moderate or severe food insecurity in their household was highest, at over 40%, among those reliant on social assistance as their main source of income in the previous year, followed by those reliant on employment insurance, with no significant change during the pandemic. This finding points to the persistent challenge of household food insecurity among working-age people outside the workforce.Note 12Note 34 Many of these individuals would have been ineligible for those pandemic relief benefits that required recent workforce participation, such as the CERB.

Levels of household food insecurity also remained high among several other higher-risk groups, including recent immigrants and people belonging to some groups designated as visible minorities. Black Canadians, other visible minority groups and recent immigrants have faced more difficult labour market situations during the pandemic, including higher rates of unemployment and low income, than non-visible minorities and longer-term residents.Note 24Note 35Note 36Note 37 Canadians belonging to some visible minority groups and recent immigrants were also more likely to live with low income before the pandemic and to express concerns about their ability to meet basic financial needs during the pandemic.Note 25Note 38 Such conditions render these groups highly vulnerable to food insecurity.

Strengths and limitations

This study is strengthened by large population samples representative of the 10 Canadian provinces, the use of a validated 18-item scale to assess multiple categories of household food insecurity, and the examination of a range of sociodemographic characteristics.

Several limitations deserve mention. This study assessed food security status during the previous 12 months. For the fall 2020 cycle of the Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS), food security status thus overlaps with the pre-pandemic period. Additionally, because data from the territories were unavailable from the fall 2020 cycle, estimates cannot be considered nationally representative.

Because the CCHS is a cross-sectional survey, it was not possible to assess changes in household-level food security status or its determinants over time. Furthermore, the CCHS collects limited data on respondents’ current employment or financial status. The fall 2020 cycle of the CCHS did not collect data on any changes to respondents’ employment or financial status specifically since the pandemic, or data on the receipt of any pandemic-related financial supports. Nevertheless, differences could be examined in food security status by labour force participation during the week before the survey for respondents aged 15 to 75. Results were consistent with the main analysis and showed either no change or a decline, compared with 2017/2018, in the proportion of Canadians reporting some experience of household food insecurity according to working status and main industry of employment. Interestingly, notable declines in household food insecurity were observed among workers in some of the industries most severely affected by economic shutdowns in 2020, including accommodation and food services, other services (except public administration), and retail trade. Workers in these industries were also among those most likely to receive CERB payments in 2020.Note 39 Future studies could link the CCHS to other data sources, such as financial data, to examine how changes in households’ financial or employment status, as well as how various financial assistance benefits and programs, have shaped the risk of household food insecurity among different population groups.

Although all data for this study came from the CCHS, the fall 2020 cycle had some differences. Likely because of the limitations to survey collection during a pandemic and the use of telephone interviews only, the overall response rate was low, at 24.6%.Note 20 As with all previous CCHS cycles, for the fall 2020 cycle, survey weights were adjusted to minimize any potential bias resulting from non-response. Non-response adjustments and calibration using available auxiliary information were applied and are reflected in the survey weights provided with the dataset. Extensive validations of survey estimates were also performed and examined from a bias analysis perspective.Note 20 Despite these rigorous adjustments, the higher level of non-response increases the risk of residual bias. Estimates drawn from the fall 2020 cycle of the CCHS should therefore be interpreted with caution, particularly for estimates for small subgroups and for comparisons with previous cycles.

Conclusions

This study documents a generally lower proportion of Canadians reporting experience of household food insecurity in the overall population and among a number of vulnerable groups during the second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in fall 2020, compared with the pre-pandemic period of 2017/2018. Nevertheless, prevalence remained high in fall 2020, with about 1 in 10 Canadians aged 12 and older reporting some level of food insecurity in their household during the prior 12 months. Low income and financial hardship are tightly linked with food insecurity. Emerging evidence suggests that emergency government financial relief benefits likely offset a potential surge in low income in 2020 because of the pandemic. However, the temporary nature of the relief benefits, along with a notable rise in the cost of living in 2021,Note 40 including higher food prices, may have impacted the financial situation of many Canadian households and, therefore, their risk of food insecurity. As a result, continued monitoring of household food insecurity in Canada during multiple phases of the pandemic and beyond is important to inform the design of programs and policies to mitigate this important public health problem and its associated negative impacts on health and well-being.

- Date modified: