Economic and Social Reports

The changing nature of work since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic

DOI: https://doi.org/10.25318/36280001202300700003-eng

Skip to text

Text begins

Abstract

Before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, rapid advances in automation and artificial intelligence were often featured in discussions around the changing nature of work. The concern, which is still present today, centred around the possibility that machines and robots could perform certain tasks more efficiently than humans, possibly resulting in rapid job transformation and potential disruptions. At the same time, increased globalization and industrial shifts may have further altered the type of tasks performed in the workplace. Previous work found that while the workforce was moving away from jobs involving routine, manual tasks and moving toward those involving non-routine, cognitive tasks, changes were moderate and very steady between 1987 and 2018 (Frank et al. 2021). This pace could have allowed workers time to adjust to the slowly evolving realities of the changing workplace, either by retraining or through demographic forces (i.e., attrition of routine, manual jobs as older workers retire). The COVID-19 pandemic and associated lockdowns may have accelerated these trends for several reasons. On the supply (worker) side, the lockdowns created many economic and health concerns for affected workers, primarily those who had close contact with the public or co-workers. This may have encouraged some workers to seek employment with less human contact. On the demand (employer) side, some businesses may have sought to make their production and delivery processes more resilient to future lockdowns by investing in automation technology, while entire industries may have expanded or contracted to match new market conditions. This article finds that some of the long-term trends in the nature of work present before the onset of the pandemic not only continued during the pandemic, but they also accelerated. In particular, the increase in the share of employed individuals in managerial, professional and technical occupations (non-routine, cognitive tasks) registered during the pandemic was higher than in the previous three decades. While the increases in non-routine, cognitive jobs registered during the pandemic were similar for men and women, the corresponding declines in other types of jobs were not. For men, most of the increase in managerial, professional and technical occupations was accompanied by important declines in production, craft, repair and operative occupations (routine, manual tasks) and service occupations (non-routine, manual tasks). For women, most of the increase in managerial, professional and technical occupations was accompanied by a decline in service occupations. For men and women, the decline in service occupations was particularly notable, especially given that the share of service jobs actually increased moderately during the three decades prior to the pandemic. For men, the decline in production, craft, repair and operative occupations represented a modest acceleration of the long-term gradual decline established before the pandemic. Finally, the increase in managerial, professional and technical occupations and the decline in service occupations were considerably more pronounced among younger workers (aged 25 to 34 years) compared with older workers (aged 45 to 54 years). Changing occupations may have required training in certain cases, and government supports were available to help displaced workers pursue this route if they chose.

Author

Marc Frenette is with the Social Analysis and Modelling Division, Analytical Studies and Modelling Branch, at Statistics Canada.

Introduction

Tracking trends in the nature of work is important for many reasons. For example, rapidly advancing technology—particularly in the forms of artificial intelligence and machine learning—may replace some work tasks traditionally performed by humans. This could lead to job transformation or job replacement. Increased globalization could also affect the nature of work, depending on the comparative advantage held by different countries in the production of various goods and services. In fact, both factors could enable one another, because new trade agreements can accelerate technology adoption and technology adoption may allow firms to compete in foreign markets (Fort et al. 2018). The effects of technology adoption and increased globalization could be positive or negative, depending on how well workers adapt to their new roles. One important consideration is how rapidly these changes are happening—slow, predictable changes may allow workers, firms and policy makers time to make necessary adjustments (e.g., to allow for training).

Another reason the nature of work matters is that career success is not defined solely by earnings. The type of work activities may also factor into the equation. Evidence suggests that achieving occupational goals can be challenging, because there is a large disparity between the occupations high school students aspire to attain by age 30 and the actual distribution of occupations held by 30-year-olds (Frenette 2009).

Frank et al. (2021) examined trends in the types of jobs held by Canadians between 1987 and 2018. Their work revealed a steady and gradual movement away from routine, manual work and toward non-routine, cognitive work during this period. Interestingly, Frank et al. (2021) did not find an acceleration of the trends that one may have expected during the 2010s, when artificial intelligence and machine learning made substantial advances.

Since then, the COVID-19 pandemic and its associated lockdowns created many economic and health concerns for workers and employers, which may have affected the supply and demand for certain job tasks. On the supply side, workers may have sought employment with less direct contact with people, such as professional jobs, which can often be performed from home in case of a lockdown. On the demand side, employers may have aimed to make their production and delivery processes more resilient in the event of future lockdowns. This involves automating tasks since machines, robots and computer algorithms are not susceptible to biological viruses. In fact, there is evidence that robot investments accelerated during the pandemic.Note By contrast, Cardoso and Malloy (2021) point to a reduction in globalization (as measured by imports and exports between Canada and the United States) that was directly linked to the severity of COVID-19 (as measured by cases, hospitalizations and deaths). In some instances, industries may have contracted or expanded because of the pandemic to match new market conditions. These supply and demand factors are not independent entities, as workers in jobs facing the lowest risk of transformation because of automation (typically highly educated individuals, according to Frenette and Frank 2020) are also the most likely to be able to do their work at home (Messacar et al. 2020). Conversely, some workers in services and production may face relatively high automation risks and be in close contact with the public or co-workers.

Whether the trends outlined by Frank et al. (2021) continued to hold during the pandemic is an open question. The purpose of the current study is to update the trends in the changing nature of work established by Frank et al. (2021) with new data covering the pandemic period (up to and including 2022). The approach, based on Autor et al. (2003), classifies occupations into four broad types: managerial, professional and technical occupations (non-routine, cognitive tasks); service occupations (non-routine, manual tasks), sales, clerical and administrative support occupations (routine, cognitive tasks); and production, craft, repair and operative occupations (routine, manual tasks).Note

Acceleration of the long-term trend toward non-routine, cognitive tasks during the pandemic

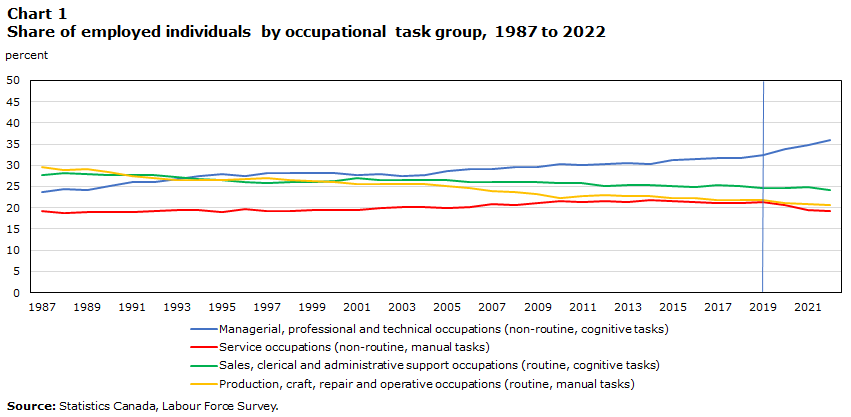

In the three decades before the pandemic, the Canadian workplace gradually shifted away from jobs requiring mostly routine, manual tasks and toward jobs requiring mostly non-routine, cognitive tasks (Chart 1). This transformation was slow but steady. In 1987, 29.5% of employees worked in production, craft, repair and operative occupations (routine, manual tasks). By 2019, this figure declined to 21.8%. Over the same period, the share of employees who worked in managerial, professional and technical occupations (non-routine, cognitive tasks) went from 23.7% in 1987 to 32.3% in 2019. Smaller changes were registered in service occupations (19.2% in 1987; 21.3% in 2019) and sales, clerical and administrative support occupations (27.6% in 1987; 24.6% in 2019).

Data table for Chart 1

| Managerial, professional and technical occupations (non-routine, cognitive tasks) | Service occupations (non-routine, manual tasks) | Sales, clerical and administrative support occupations (routine, cognitive tasks) | Production, craft, repair and operative occupations (routine, manual tasks) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| percent | ||||

| 1987 | 23.7 | 19.2 | 27.6 | 29.5 |

| 1988 | 24.4 | 18.7 | 28.1 | 28.8 |

| 1989 | 24.1 | 19.0 | 27.8 | 29.1 |

| 1990 | 25.1 | 18.9 | 27.6 | 28.4 |

| 1991 | 26.0 | 18.9 | 27.7 | 27.5 |

| 1992 | 26.1 | 19.3 | 27.6 | 26.9 |

| 1993 | 26.7 | 19.5 | 27.3 | 26.5 |

| 1994 | 27.4 | 19.4 | 26.8 | 26.4 |

| 1995 | 28.0 | 19.1 | 26.5 | 26.5 |

| 1996 | 27.4 | 19.7 | 26.1 | 26.8 |

| 1997 | 28.1 | 19.3 | 25.7 | 26.9 |

| 1998 | 28.3 | 19.1 | 26.0 | 26.6 |

| 1999 | 28.2 | 19.4 | 26.1 | 26.3 |

| 2000 | 28.2 | 19.6 | 26.2 | 26.1 |

| 2001 | 27.8 | 19.6 | 27.0 | 25.7 |

| 2002 | 27.9 | 19.9 | 26.5 | 25.7 |

| 2003 | 27.6 | 20.2 | 26.6 | 25.6 |

| 2004 | 27.7 | 20.2 | 26.6 | 25.5 |

| 2005 | 28.5 | 20.0 | 26.4 | 25.1 |

| 2006 | 29.2 | 20.2 | 26.0 | 24.6 |

| 2007 | 29.1 | 20.8 | 26.1 | 24.0 |

| 2008 | 29.6 | 20.7 | 26.1 | 23.7 |

| 2009 | 29.6 | 21.1 | 26.0 | 23.3 |

| 2010 | 30.4 | 21.6 | 25.7 | 22.4 |

| 2011 | 30.0 | 21.4 | 25.9 | 22.7 |

| 2012 | 30.4 | 21.5 | 25.1 | 23.0 |

| 2013 | 30.6 | 21.4 | 25.3 | 22.7 |

| 2014 | 30.2 | 21.7 | 25.4 | 22.7 |

| 2015 | 31.2 | 21.5 | 25.1 | 22.2 |

| 2016 | 31.5 | 21.3 | 24.9 | 22.3 |

| 2017 | 31.7 | 21.2 | 25.3 | 21.9 |

| 2018 | 31.7 | 21.1 | 25.2 | 21.9 |

| 2019 | 32.3 | 21.3 | 24.6 | 21.8 |

| 2020 | 33.8 | 20.5 | 24.6 | 21.0 |

| 2021 | 34.8 | 19.4 | 25.0 | 20.8 |

| 2022 | 36.0 | 19.2 | 24.3 | 20.5 |

|

Note: The blue vertical line is positioned over the year 2019 in order to separate the pre-pandemic period (2019 and earlier) from the pandemic period (2020 to 2022). Source: Statistics Canada, Labour Force Survey. |

||||

The gradual movement toward jobs associated with non-routine, cognitive tasks accelerated during the pandemic. Specifically, the share of employees in managerial, professional and technical occupations went from 32.3% in 2019 to 36.0% in 2022. This represented a 3.7 percentage point increase (significant at 0.1%) over a short period (three years). The growth in the share of employees in managerial, professional and technical occupations over the past 3 years accounted for 30.1% of the growth over the past 35 years.

The 3.7 percentage point increase in the share of managerial, professional and technical occupations during the pandemic was accompanied by declines in service occupations (-2.1 percentage points, significant at 0.1%) and production, craft, repair and operative occupations (-1.2 percentage points, significant at 0.1%). The decline in service occupations was particularly notable, especially given that the share of service jobs increased moderately during the three decades before the pandemic. The share of jobs in sales, clerical and administrative support occupations was relatively stable during this time (-0.3 percentage points, not significant at 10%).

Of course, some of the changes in the nature of work during the pandemic could have been brought on by new market conditions or technology adoption that may have affected the industry distribution of employment. After changes in industry composition across the entire period (1987 to 2022) are accounted for, the share of employment in managerial, professional and technical occupations increased by 2.0 to 2.3 percentage points between 2019 and 2022 (down from a 3.7 percentage point increase in the raw data). This change was considerably larger than in any three-year period recorded during the 1987-to-2022 period, except for the 1992-to-1995 period, when a similar increase was registered.Note

Recent trends in job tasks different for men and women

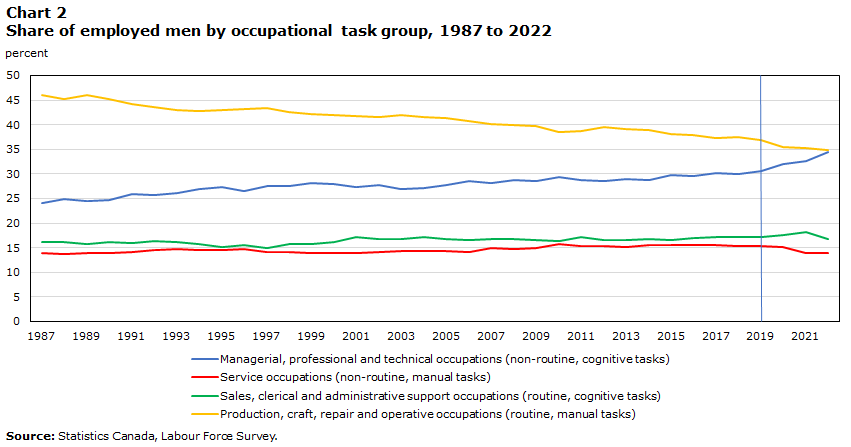

Although there were similar increases in the share of employed men and women in managerial, professional and technical occupations during the pandemic, both sexes experienced declines in the shares of different types of occupations.

Indeed, the share of employed men in managerial, professional and technical occupations increased by 3.8 percentage points (significant at 0.1%) during the pandemic, from 30.7% in 2019 to 34.5% in 2022 (Chart 2). This increase was only slightly greater than that registered by women—3.6 percentage points (also significant at 0.1%)—as the share rose from 34.0% in 2019 to 37.6% in 2022 (Chart 3).

Data table for Chart 2

| Managerial, professional and technical occupations (non-routine, cognitive tasks) | Service occupations (non-routine, manual tasks) | Sales, clerical and administrative support occupations (routine, cognitive tasks) | Production, craft, repair and operative occupations (routine, manual tasks) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| percent | ||||

| 1987 | 24.1 | 13.8 | 16.1 | 46.0 |

| 1988 | 24.9 | 13.8 | 16.2 | 45.2 |

| 1989 | 24.4 | 13.9 | 15.7 | 46.0 |

| 1990 | 24.6 | 14.0 | 16.2 | 45.2 |

| 1991 | 25.9 | 14.1 | 16.0 | 44.1 |

| 1992 | 25.7 | 14.5 | 16.3 | 43.5 |

| 1993 | 26.0 | 14.8 | 16.1 | 43.0 |

| 1994 | 26.9 | 14.6 | 15.7 | 42.9 |

| 1995 | 27.4 | 14.4 | 15.2 | 42.9 |

| 1996 | 26.5 | 14.7 | 15.6 | 43.3 |

| 1997 | 27.5 | 14.1 | 15.0 | 43.4 |

| 1998 | 27.5 | 14.2 | 15.7 | 42.6 |

| 1999 | 28.1 | 14.0 | 15.8 | 42.2 |

| 2000 | 28.0 | 13.9 | 16.2 | 41.9 |

| 2001 | 27.3 | 13.9 | 17.2 | 41.7 |

| 2002 | 27.7 | 14.1 | 16.7 | 41.6 |

| 2003 | 26.9 | 14.3 | 16.8 | 41.9 |

| 2004 | 27.1 | 14.2 | 17.2 | 41.6 |

| 2005 | 27.7 | 14.3 | 16.7 | 41.3 |

| 2006 | 28.6 | 14.2 | 16.6 | 40.7 |

| 2007 | 28.2 | 14.9 | 16.7 | 40.2 |

| 2008 | 28.7 | 14.6 | 16.7 | 40.0 |

| 2009 | 28.6 | 15.0 | 16.6 | 39.8 |

| 2010 | 29.4 | 15.8 | 16.3 | 38.5 |

| 2011 | 28.8 | 15.3 | 17.2 | 38.8 |

| 2012 | 28.6 | 15.3 | 16.5 | 39.6 |

| 2013 | 29.0 | 15.2 | 16.6 | 39.2 |

| 2014 | 28.7 | 15.6 | 16.8 | 38.9 |

| 2015 | 29.8 | 15.6 | 16.6 | 38.1 |

| 2016 | 29.7 | 15.5 | 16.9 | 38.0 |

| 2017 | 30.1 | 15.5 | 17.2 | 37.3 |

| 2018 | 29.9 | 15.4 | 17.3 | 37.5 |

| 2019 | 30.7 | 15.4 | 17.1 | 36.9 |

| 2020 | 32.0 | 15.1 | 17.5 | 35.5 |

| 2021 | 32.6 | 14.0 | 18.1 | 35.3 |

| 2022 | 34.5 | 13.9 | 16.8 | 34.8 |

|

Note: The blue vertical line is positioned over the year 2019 in order to separate the pre-pandemic period (2019 and earlier) from the pandemic period (2020 to 2022). Source: Statistics Canada, Labour Force Survey. |

||||

Data table for Chart 3

| Managerial, professional and technical occupations (non-routine, cognitive tasks) | Service occupations (non-routine, manual tasks) | Sales, clerical and administrative support occupations (routine, cognitive tasks) | Production, craft, repair and operative occupations (routine, manual tasks) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| percent | ||||

| 1987 | 23.4 | 25.6 | 41.3 | 9.9 |

| 1988 | 23.9 | 24.5 | 41.9 | 9.7 |

| 1989 | 23.8 | 24.7 | 41.8 | 9.7 |

| 1990 | 25.6 | 24.5 | 40.6 | 9.4 |

| 1991 | 26.0 | 24.4 | 40.7 | 8.9 |

| 1992 | 26.6 | 24.8 | 40.2 | 8.4 |

| 1993 | 27.4 | 24.7 | 39.7 | 8.2 |

| 1994 | 28.0 | 24.7 | 39.1 | 8.2 |

| 1995 | 28.6 | 24.2 | 38.9 | 8.3 |

| 1996 | 28.3 | 25.4 | 37.9 | 8.5 |

| 1997 | 28.8 | 25.0 | 37.6 | 8.7 |

| 1998 | 29.1 | 24.5 | 37.3 | 9.1 |

| 1999 | 28.5 | 25.3 | 37.2 | 9.0 |

| 2000 | 28.4 | 25.6 | 37.0 | 9.0 |

| 2001 | 28.4 | 25.6 | 37.4 | 8.7 |

| 2002 | 28.2 | 26.2 | 36.9 | 8.6 |

| 2003 | 28.2 | 26.4 | 36.9 | 8.5 |

| 2004 | 28.3 | 26.4 | 36.5 | 8.8 |

| 2005 | 29.4 | 25.8 | 36.6 | 8.1 |

| 2006 | 29.9 | 26.5 | 35.8 | 7.8 |

| 2007 | 30.1 | 26.8 | 35.9 | 7.3 |

| 2008 | 30.6 | 26.8 | 35.7 | 6.9 |

| 2009 | 30.7 | 27.3 | 35.6 | 6.5 |

| 2010 | 31.4 | 27.4 | 35.3 | 5.9 |

| 2011 | 31.3 | 27.7 | 34.9 | 6.2 |

| 2012 | 32.1 | 27.8 | 33.9 | 6.1 |

| 2013 | 32.2 | 27.7 | 34.2 | 5.9 |

| 2014 | 31.8 | 28.0 | 34.3 | 5.9 |

| 2015 | 32.7 | 27.7 | 33.9 | 5.7 |

| 2016 | 33.4 | 27.4 | 33.2 | 6.0 |

| 2017 | 33.3 | 27.1 | 33.7 | 5.9 |

| 2018 | 33.6 | 27.1 | 33.5 | 5.8 |

| 2019 | 34.0 | 27.5 | 32.4 | 6.1 |

| 2020 | 35.8 | 26.2 | 32.1 | 5.9 |

| 2021 | 37.0 | 25.2 | 32.1 | 5.7 |

| 2022 | 37.6 | 24.7 | 31.9 | 5.8 |

|

Note: The blue vertical line is positioned over the year 2019 in order to separate the pre-pandemic period (2019 and earlier) from the pandemic period (2020 to 2022). Source: Statistics Canada, Labour Force Survey. |

||||

For men, the increase in the share employed in managerial, professional and technical occupations was accompanied by declines in the shares employed in production, craft, repair and operative occupations (-2.1 percentage points) and in service occupations (-1.4 percentage points), both significant at 0.1%. By contrast, most of the increase in the share of employed women in managerial, professional and technical occupations was accompanied by a decline in the share employed in service occupations (-2.8 percentage points, significant at 0.1%).

The next two charts show the percentage point changes between 2019 and 2022 in the share employed in more specific occupations within each of the four broad occupational task categories for men (Chart 4) and women (Chart 5). These findings reveal the importance of disaggregating results by sex and the more detailed occupations. In fact, in most of these sex and broad occupation categories, the share of workers increased in some occupations, but declined in others. Moreover, the trends for the more detailed occupations were, at times, different for men and women.

Data table for Chart 4

| National Occupational Classification 2016 | Percentage point change between 2019 and 2022 |

|---|---|

| Managerial, professional and technical occupations (non-routine, cognitive tasks) | |

| Professional occupations in natural and applied sciences (21) | 1.91Note *** |

| Specialized middle management occupations (01-05) | 1.08Note *** |

| Professional occupations in business and finance (11) | 0.37Note * |

| Middle management occupations in trades, transportation, production and utilities (07-09) | 0.27Note * |

| Professional occupations in education services (40) | 0.27Data table for Chart 4 Note † |

| Professional occupations in law and social, community and government services (41) | 0.19Data table for Chart 4 Note † |

| Professional occupations in nursing (30) | 0.15Note ** |

| Middle management occupations in retail and wholesale trade and customer services (06) | 0.10 |

| Professional occupations in art and culture (51) | 0.07 |

| Professional occupations in health (except nursing) (31) | 0.03 |

| Technical occupations in health (32) | 0.01 |

| Senior management occupations (00) | -0.01 |

| Technical occupations related to natural and applied sciences (22) | -0.32Data table for Chart 4 Note † |

| Technical occupations in art, culture, recreation and sport (52) | -0.35Note ** |

| Service occupations (non-routine, manual tasks) | |

| Assisting occupations in support of health services (34) | 0.16Note * |

| Occupations in front-line public protection services (43) | 0.15Data table for Chart 4 Note † |

| Paraprofessional occupations in legal, social, community and education services (42) | 0.04 |

| Care providers and educational, legal and public protection support occupations (44) | 0.00 |

| Service representatives and other customer and personal services occupations (65) | -0.53Note *** |

| Service supervisors and specialized service occupations (63) | -0.62Note *** |

| Service support and other service occupations, not elsewhere classified (67) | -0.64Note *** |

| Sales, clerical and administrative support occupations (routine, cognitive tasks) | |

| Administrative and financial supervisors and administrative occupations (12) | 0.46Note *** |

| Office support occupations (14) | 0.18Data table for Chart 4 Note † |

| Distribution, tracking and scheduling co-ordination occupations (15) | 0.05 |

| Retail sales supervisors and specialized sales occupations (62) | -0.03 |

| Finance, insurance and related business administrative occupations (13) | -0.10 |

| Sales support occupations (66) | -0.21 |

| Sales representatives and salespersons - wholesale and retail trade (64) | -0.59Note *** |

| Production, craft, repair and operative occupations (routine, manual tasks) | |

| Other installers, repairers and servicers and material handlers (74) | 0.17 |

| Supervisors and technical occupations in natural resources, agriculture and related production (82) | 0.02 |

| Harvesting, landscaping and natural resources labourers (86) | -0.01 |

| Assemblers in manufacturing (95) | -0.04 |

| Processing and manufacturing machine operators and related production workers (94) | -0.07 |

| Workers in natural resources, agriculture and related production (84) | -0.09 |

| Trades helpers, construction labourers and related occupations (76) | -0.19Data table for Chart 4 Note † |

| Processing, manufacturing and utilities supervisors and central control operators (92) | -0.25Note * |

| Maintenance and equipment operation trades (73) | -0.35Data table for Chart 4 Note † |

| Transport and heavy equipment operation and related maintenance occupations (75) | -0.36Data table for Chart 4 Note † |

| Labourers in processing, manufacturing and utilities (96) | -0.40Note *** |

| Industrial, electrical and construction trades (72) | -0.54Note * |

Source: Statistics Canada, Labour Force Survey. |

|

Data table for Chart 5

| National Occupational Classification 2016 | Percentage point change between 2019 and 2022 |

|---|---|

| Managerial, professional and technical occupations (non-routine, cognitive tasks) | |

| Professional occupations in business and finance (11) | 1.17Note *** |

| Professional occupations in natural and applied sciences (21) | 0.68Note *** |

| Specialized middle management occupations (01-05) | 0.54Note *** |

| Professional occupations in law and social, community and government services (41) | 0.47Note ** |

| Professional occupations in health (except nursing) (31) | 0.30Note *** |

| Professional occupations in nursing (30) | 0.27Data table for Chart 5 Note † |

| Professional occupations in education services (40) | 0.24 |

| Technical occupations related to natural and applied sciences (22) | 0.14 |

| Technical occupations in health (32) | 0.05 |

| Middle management occupations in trades, transportation, production and utilities (07-09) | 0.04 |

| Professional occupations in art and culture (51) | 0.04 |

| Senior management occupations (00) | -0.02 |

| Middle management occupations in retail and wholesale trade and customer services (06) | -0.03 |

| Technical occupations in art, culture, recreation and sport (52) | -0.29Note * |

| Service occupations (non-routine, manual tasks) | |

| Assisting occupations in support of health services (34) | 0.10 |

| Occupations in front-line public protection services (43) | 0.02 |

| Paraprofessional occupations in legal, social, community and education services (42) | 0.00 |

| Care providers and educational, legal and public protection support occupations (44) | -0.14 |

| Service supervisors and specialized service occupations (63) | -0.65Note *** |

| Service support and other service occupations, not elsewhere classified (67) | -0.76Note *** |

| Service representatives and other customer and personal services occupations (65) | -1.40Note *** |

| Sales, clerical and administrative support occupations (routine, cognitive tasks) | |

| Administrative and financial supervisors and administrative occupations (12) | 0.47Note * |

| Retail sales supervisors and specialized sales occupations (62) | 0.06 |

| Finance, insurance and related business administrative occupations (13) | -0.02 |

| Sales representatives and salespersons - wholesale and retail trade (64) | -0.03 |

| Sales support occupations (66) | -0.07 |

| Distribution, tracking and scheduling co-ordination occupations (15) | -0.12 |

| Office support occupations (14) | -0.81Note *** |

| Production, craft, repair and operative occupations (routine, manual tasks) | |

| Maintenance and equipment operation trades (73) | 0.11Note * |

| Other installers, repairers and servicers and material handlers (74) | 0.06 |

| Processing, manufacturing and utilities supervisors and central control operators (92) | 0.04 |

| Transport and heavy equipment operation and related maintenance occupations (75) | 0.01 |

| Trades helpers, construction labourers and related occupations (76) | 0.00 |

| Industrial, electrical and construction trades (72) | -0.01 |

| Assemblers in manufacturing (95) | -0.01 |

| Workers in natural resources, agriculture and related production (84) | -0.02 |

| Supervisors and technical occupations in natural resources, agriculture and related production (82) | -0.03 |

| Harvesting, landscaping and natural resources labourers (86) | -0.07Data table for Chart 5 Note † |

| Processing and manufacturing machine operators and related production workers (94) | -0.10 |

| Labourers in processing, manufacturing and utilities (96) | -0.23Note ** |

Source: Statistics Canada, Labour Force Survey. |

|

Among managerial, professional and technical occupations, employment shares increased in most cases for both men and women, in particular among managerial and professional jobs. The largest increase for men was registered in professional occupations in natural and applied sciences—from 6.8% of all jobs among men in 2019 to 8.7% in 2022 (a 1.9 percentage point increase, significant at 0.1%). For women, the largest increase was in professional occupations in business and finance, going from 4.2% in 2019 to 5.4% in 2022 (a 1.2 percentage point increase, significant at 0.1%). Employment shares only declined (moderately) for a small number of occupations, all technical in nature (again, for both men and women).

Employment shares in service occupations declined in three cases for men and women: service representatives and other customer and personal services occupations; service supervisors and specialized service occupations; and service support and other service occupations, not elsewhere classified. The largest decline was registered in service representatives and other customer and personal services occupations among women, from 6.8% in 2019 to 5.4% in 2022 (a 1.4 percentage point decline, significant at 0.1%). Some very moderate gains in employment share were registered among men in assisting occupations in support of health services and in occupations in front-line public protection services.

Overall, and as previously noted, there were no changes in the employment share of sales, clerical and administrative support occupations. However, for men and women, the more detailed occupational breakdowns revealed a small number of gains and losses in employment shares. First, the share of employment in administrative and financial supervisors and administrative occupations increased by 0.5 percentage points for both men (significant at 0.1%) and women (significant at 5%). The employment share in sales representatives and salespersons - wholesale and retail trade declined for men (‑0.6 percentage points, significant at 0.1%). Interestingly, the employment share in office support occupations declined among women (-0.8 percentage points, significant at 0.1%), but increased moderately among men (+0.2 percentage points, significant at 10%). It is worth noting that a much smaller share of men were employed in office support occupations in 2019 (1.1%) compared with women during that year (7.0%).

Men registered significant declines in employment shares in many of the more detailed occupations under the broader category of production, craft, repair and operative occupations. For women, there were far fewer significant declines, and they were smaller than those registered among men. This finding is perhaps not surprising because the share of men employed in production, craft, repair and operative occupations (36.9%) was about six times higher than the share of women in these jobs (6.1%) in 2019.

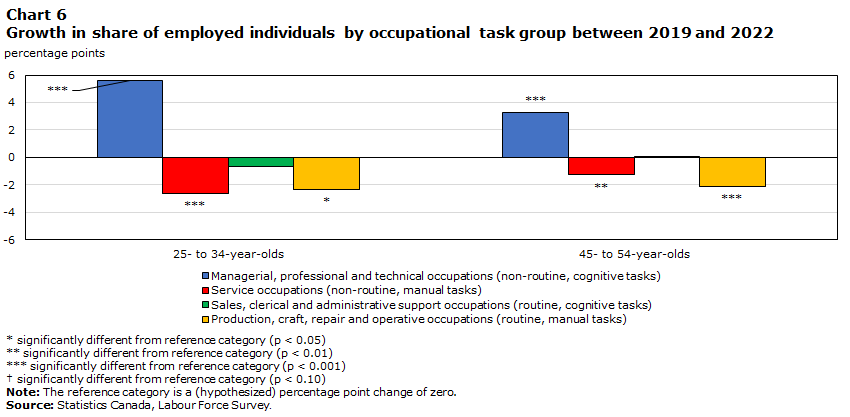

Increase in occupations requiring non-routine, cognitive tasks almost twice as large among younger workers as among older workers

The increase in managerial, professional and technical occupations and the decline in service occupations were considerably more pronounced among younger workers (aged 25 to 34 years) compared with older workers (aged 45 to 54 years). More specifically, the share of employed individuals in managerial, professional and technical occupations increased by 5.6 percentage points (significant at 0.1%) between 2019 and 2022 among 25- to 34-year-olds, compared with 3.2 percentage points (significant at 0.1%) among 45- to 54-year-olds (Chart 6). Meanwhile, the share of employed individuals in service occupations declined by 2.6 percentage points (significant at 0.1%) among 25- to 34-year-olds, compared with a decline of 1.2 percentage points (significant at 1%) among 45- to 54-year-olds. The declining employment shares in production, craft, repair and operative occupations were similar among both age groups.Note

Data table for Chart 6

| 25- to 34-year-olds | 45- to 54-year-olds | |

|---|---|---|

| percentage points | ||

| Managerial, professional and technical occupations (non-routine, cognitive tasks) | 5.61Note *** | 3.25Note *** |

| Service occupations (non-routine, manual tasks) | -2.61Note *** | -1.24Note ** |

| Sales, clerical and administrative support occupations (routine, cognitive tasks) | -0.68 | 0.07 |

| Production, craft, repair and operative occupations (routine, manual tasks) | -2.31Note * | -2.08Note *** |

Note: The reference category is a (hypothesized) percentage point change of zero. Source: Statistics Canada, Labour Force Survey. |

||

Although there is no guaranteed way to predict the future, the trends by age group may provide insight into future trends. The increasing demand for managerial, professional and technical occupations may be more easily met by younger workers, whose human capital may be more malleable. In other words, younger workers may be in a better position to pivot since they generally have fewer family responsibilities holding them back from returning to school, and they have more years to recover their investments.

Conclusion

For several decades before the COVID-19 pandemic, the nature of work in Canada was slowly shifting toward non-routine, cognitive tasks and away from routine, manual tasks. This trend was likely attributable to the gradual adoption of automation technology and increased globalization. Following shutdowns that were costly for firms and workers, firms may have sought to make the production of their goods and services more resilient through automation, while workers may have sought jobs that were less susceptible to future closures.

This article finds that some of the long-term trends in the nature of work that were present before the pandemic not only continued during the pandemic, but also began to accelerate for the first time in decades. In particular, the share of men and women employed in managerial, professional and technical occupations (non-routine, cognitive tasks) increased more rapidly than in the previous three decades. This change was accompanied by notable declines in the share of men and women employed in service occupations (non-routine, manual tasks) and, for men, a modest acceleration of a long-term downward trend in the share of employment in production, craft, repair and operative occupations (routine, manual tasks). Finally, the increase in Managerial, professional and technical occupations and the decline in Service occupations was considerably more pronounced among younger workers (aged 25 to 34 years) compared with older workers (aged 45 to 54 years). Changing occupations may have required training in certain cases, and government supports were available to help displaced workers pursue this route if they chose.

Future work in this area should continue to monitor these trends as the economy moves into a post-pandemic world, with changing demand and supply conditions for different types of workers. On the demand side, this is especially important as technology continues to evolve, and the resulting job transformation requires workers, firms and policy makers to think about the need for adaptive strategies. Understanding where the nature of work is headed can also provide useful information for individuals involved in making decisions about their education and for those involved in job search strategies. It will be particularly interesting to monitor the ability of artificial intelligence to mimic humans in advanced functions. For example, Korinek (2023) demonstrates the usefulness of large language models (such as ChatGPT) in economics as research assistants and tutors in six domains: ideation, writing, background research, data analysis, coding and mathematical derivations. Other forms of artificial intelligence are also developing rapidly in areas of music, visualization, simulated conversations, etc. On the supply side, the current labour shortages appear to be highly concentrated in jobs requiring no postsecondary education,Note and this could also affect trends in the type of work performed by the Canadian workforce (depending on how workers, employers and policy makers react to evolving labour market conditions).

References

Autor, D.G., F. Levy, and R.J. Murnane. 2003. The skill content of recent technological change: an empirical exploration. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 118, No. 4, pp. 1279-1333.

Cardoso, M. and B. Malloy. 2021. Impact of the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic on trade between Canada and the United States. Canadian Public Policy. Vol. 47, No. 4, pp. 554-572.

Dixon, J. 2020. How to build a robots! database.Methods and References, No. 28.

Fort, T.C., J.R. Pierce, and P.K. Schott. 2018. New perspectives on the decline of US manufacturing employment. Journal of Economic Perspectives. Vol. 32, No. 2, pp. 47-72.

Frank, K., Yang, Z., & Frenette, M. 2021. The changing nature of work in Canada amid recent advances in automation technology. Economic and Social Reports. Vol. 1, No. 1.

Frenette, M. 2009. Career goals in high school: Do students know what it takes to reach them, and does it matter? Analytical Studies Branch Research Paper Series. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 11F0019M320.

Frenette, M. and K. Frank. 2020. Automation and job transformation in Canada: Who’s at risk? Analytical Studies Branch Research Paper Series. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 11F0019M448.

Korinek, A. 2023. Language models and cognitive automation for economic research. National Bureau of Economic Research. Working paper No. 30957.

Messacar, D., Morissette, R., & Deng, Z. 2020. Inequality in the feasibility of working from home during and after COVID-19. StatCan COVID-19: Data to Insights for a Better Canada. Statistics Canada.

- Date modified: