Experiences of serious problems or disputes in the Canadian provinces, 2021

by Laura Savage, Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics and Susan McDonald, Department of Justice Canada

Highlights

- According to the 2021 Canadian Legal Problems Survey, just under one in five (18%) people living in Canada’s provinces had experienced at least one dispute or problem that they considered serious or not easy to fix in the three years preceding the survey.

- The most commonly reported problems were problems in the neighbourhood, including vandalism and property damage (21%), receiving poor or incorrect medical treatment (16%), being harassed (16%), being discriminated against (16%), or having a problem with a large purchase or service (15%).

- Almost four in ten (39%) people living in Canada’s provinces who reported experiencing at least one serious problem said that their problem happened during the COVID-19 pandemic (after March 16, 2020).

- Among those who reported experiencing a serious legal problem, more than half (55%) experienced one problem, while 22% experienced two serious problems and an additional 23% experienced three or more serious problems over the three-year period.

- Almost nine in ten (87%) Canadians who experienced a serious problem reported taking some form of action to address it, with most seeking resolution outside of the formal justice system.

- Two in ten (21%) people living in Canada’s provinces who had experienced a serious problem in the last three years said that their most serious problem had been resolved, with just under two in ten (19%) more stating that their serious problem was still in progress of being resolved. Just over one in ten (12%) Canadians who had reported a serious problem said that they had dropped or given up on resolving their serious problem.

- More than four in ten (42%) Canadians who had experienced a serious problem said that their dispute or problem worsened or became more difficult to resolve as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. There were no significant differences between men and women.

Every Canadian has the right to a justice system that is fair, timely and accessible. An accessible justice system is one that enables Canadians to obtain the information and assistance they need to help prevent legal issues from arising and help them to resolve these issues efficiently, affordably, and fairly, either through informal resolution mechanisms, where possible, or the formal justice system, when necessary (Department of Justice Canada 2019). The definition of an accessible justice system has evolved over time and may mean different things to different people depending on their own lived experiences and on social context (Farrow 2014).

Timely access to a fair and effective justice system—and the resolution of problems and disputes—helps support the well-being of individuals and communities (Pleasence et al. 2004; Smith et al. 2013). Recent Canadian research has found that approximately one-third of Canadians are confident that the Canadian criminal justice system is accessible to all people, while 27% are confident that it is fair to all people (Department of Justice Canada 2019).

Administrative data analyzing the number of court cases and case processing times are critical sources of information in highlighting the amount of time and resources needed to complete a case in federal and provincial courts. However, results from legal problems surveys in Canada and around the world show that the majority of individuals do not turn to the formal justice system to resolve their serious problems (Farrow et al. 2016). There are many reasons for resolving serious problems outside of the legal system, including the cost of legal representation, the time needed to navigate the justice system, a lack of available services in certain areas, along with other barriers to accessing justice (Trebilcock et al. 2012; Sandefur 2014). As a result, administrative data sources alone are unable to provide a complete picture of access to justice in Canada.

It is important to note that unequal access to justice caused by these barriers may perpetuate existing inequalities within society. Legal problems surveys, which ask people directly about problems in their daily lives that may have a legal dimension, highlight the experiences of different populations. This helps governments, decision-and policy-makers better understand people’s legal problems from their perspective, and aids in the development of effective justice programs and policies that will better serve Canadians. The move from a system-focused to a people-centered approach to access to justice represents a significant paradigm shift in the conceptualization of access to justice and, with it, the delivery of legal services.

In 2021, for the first time, Statistics Canada conducted the Canadian Legal Problems Survey (CLPS). The development and collection of this survey was funded by the Department of Justice Canada and other federal partnersNote as part of the Canadian federal government’s strategy to measure Canada’s progress in realizing the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 16: Equal access to justice for all (Text box 3). A legal problem, in the context of legal problems surveys, includes any problem that could have legal implications or a possible legal solution, and is not limited to problems that were addressed or resolved through the formal justice system or even recognized by the respondent as having a “legal” aspect.

Using data from the 2021 CLPS, this Juristat article highlights the frequency and types of serious problems that people living in Canada’s provinces experience,Note actions taken to resolve these problems, and the financial, socio-economic and health impacts of these problems on people’s everyday lives. Barriers to accessing justice are explored and, wherever possible, data are disaggregated to highlight the experiences of different populations in the 10 provinces.

There are two key methodological points to highlight regarding this analysis. First, this survey was not conducted in Canada’s territories. Second, respondents were asked two questions to determine whether they had experienced a problem within the scope of this survey. The first question was whether they had experienced any of a series of possible problems in the three years preceding the survey; and then those who had experienced a problem were asked if they considered these problems serious or not easy to fix. Analysis in this report focuses primarily on serious or difficult to resolve problems.

It is important to note that the ongoing global COVID-19 pandemic has had a drastic impact on access to justice. Courts, tribunals and other legal services were closed or limited to respect public health and safety requirements. Since then, the COVID-19 pandemic has created new serious problems for some Canadians living in the provinces or made existing problems more difficult to resolve. The pandemic has also further highlighted the challenges of accessing justice for many people in Canada’s provinces, affecting certain populations more than others. Data collection for the CLPS took place from February to August 2021. During this time, COVID-19 spread at different rates across the country, with some provinces imposing stricter restrictions than others. Respondents were specifically asked about the COVID-19 pandemic in relation to their serious problem(s) and the results are outlined in this Juristat article (see Text box 4).

Start of text box 1

Text box 1

How surveys define and measure legal problems

In Paths to Justice, the first legal problems survey in England and Wales, Hazel Genn defined a justiciable problem as “a matter experienced by a respondent which raised legal issues, whether or not it was recognized by the respondent as being ‘legal’ and whether or not any action taken by the respondent to deal with the event involved the use of any part of the civil justice system.” (Genn 1999). Building on this work, researchers and organizations have continued to define and measure justiciable problems, which are commonly referred to as legal problems, serious problems, or everyday legal problems.

Legal need arises when people require legal services in order to resolve problems which have a potential legal solution (Pleasence 2016). Access to justice is a broader term and involves not only legal services responding to legal need, but also a range of services that could help resolve problems.

Building on existing work, Statistics Canada conducted the Canadian Legal Problems Survey (CLPS) in 2021, which asked people to describe the problems or disputes they had experienced in the past three years. The survey was conducted among people aged 18 years and older in the ten provinces. It is important to note that a legal problem, in the context of legal problems surveys, includes any problem that could have legal implications or a potential legal solution, and is not limited to problems that were addressed or resolved through the formal justice system. Given this scope, respondents were asked about a series of problems that they may not necessarily consider to be a legal problem.

The types of problems were broken down into the following categories:

- A problem with a large purchase or service;

- A problem with an employer or a job;

- A personal injury or serious health issue;

- Vandalism, property damage or threats;

- A problem with a house, rent, mortgage or rent owed;

- Debt or money owed to the respondent;

- A problem with government assistance programs or amount received;

- A problem with immigration;

- Contact with the police;

- Breakdown of family;

- A problem related to child custody;

- A will, or taking care of financial or health issues for a person who was unable to look after theirself;

- Poor or incorrect medical treatment;

- Court or a letter threatening legal action;

- Being harassed;Note

- Being discriminated against;

- Other problems.

Respondents were asked whether any of the problems or disputes they had experienced in this period were serious and not easy to fix, and were then asked to identify their most serious problem. The analysis in this Juristat article focuses only on those problems considered to be serious by Canadians living in the provinces.

End of text box 1

Almost one in five Canadians experienced at least one serious problem in the previous three years

In 2021, approximately one-third (34%) of people living in Canada’s provinces reported experiencing at least one dispute or problem measured by the Canadian Legal Problems Survey (CLPS) during the previous three years. Among those who experienced a dispute or problem, almost one in five (18%, or 5.5 million Canadians) stated that the dispute or problem they experienced was serious and not easy to fix. Overall, experiencing a serious problem was as common for women (18%) as it was for men (18%) (Table 1).Note

Of the problems considered to be serious, problems in the neighbourhood, including vandalism and property damage was the most commonly reported problem (21%), followed by harassment (16%), poor or incorrect medical treatment (16%), a problem related to discrimination (16%), and a problem with a large purchase or service (15%). Notably, there were some gender differences in terms of the most common serious problems experienced, including poor or incorrect medical treatment (19% of women versus 14% of men) and harassment (18% of women versus 14% of men) (Table 1).

More than four in ten Canadians who reported at least one serious problem experience multiple serious problems

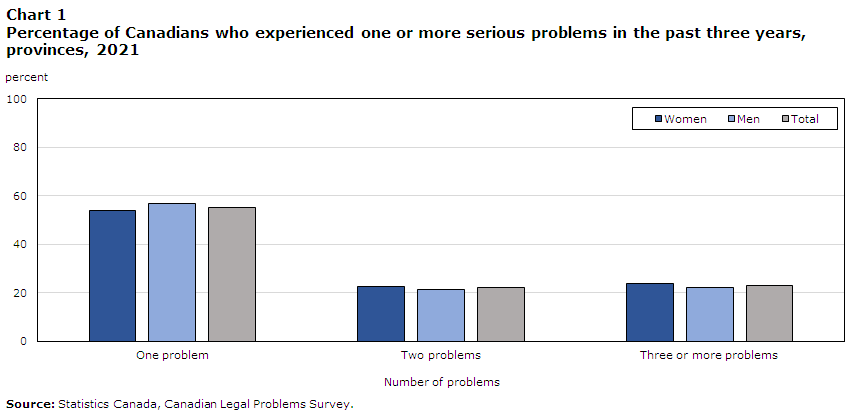

Research shows that most problems are not isolated incidents but instead tend to co-occur, with the risk of experiencing additional problems increasing as the number of current problems multiplies (Currie 2009; Pleasence et al. 2004; Smith et al. 2013). According to the CLPS, of those who experienced at least one serious problem in the three years preceding the survey, 55% experienced one serious problem, 22% experienced two serious problems, and an additional 23% experienced three or more serious problemsNote (Chart 1). There were no statistically significant differences between women and men when it came to the number of serious problems experienced in the past three years.

Chart 1 start

Data table for Chart 1

| Number of problems | Women | Men | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| percent | |||

| One problem | 54 | 57 | 55 |

| Two problems | 23 | 21 | 22 |

| Three or more problems | 24 | 22 | 23 |

| Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Legal Problems Survey. | |||

Chart 1 end

Some socio-demographic groups were more likely to report experiencing a serious problem

The likelihood of experiencing a serious problem is not the same for everyone. Research to date has shown that some socio-demographic groups are particularly disadvantaged when it comes to experiencing serious problems, as well as when accessing justice (The Hague Institute for Innovation of Law 2021). Specifically, research shows that people who experience various forms of systemic disadvantage—such as people with disabilities or people with low household incomes—are most at risk of experiencing multiple problems in their lifetime (Smith et al. 2013; Currie 2009).

Generations of First Nations people, Métis, and Inuit (Indigenous) continue to be negatively impacted by colonial policies and practices on Indigenous peoples, including socio-economic and health care gaps. The long standing impacts of residential schools and the sixties scoop continue to perpetuate the inequalities and disadvantages among Indigenous peoples (MMIWG 2019).

Notably, First Nations people, Métis and Inuit living in the provincesNote were much more likely than non-Indigenous people to report experiencing one or more serious problems in the three years preceding the survey (27% versus 18%) (Table 2). More specifically, 28% of First Nations people, 27% of Métis, and 24% of Inuit experienced one or more serious problems.

A multivariate regression model was conducted to analyze factors associated with increased odds of experiencing one or more serious problems, including age, gender, Indigenous identity, visible minority status and immigrant status. Indigenous people were 41% more likely than non-Indigenous people to experience a serious problem, when controlling for other factors (Model 1).

One-fifth (20%) of people belonging to a group designated as visible minority reported experiencing at least one serious problem—a proportion slightly higher than that of people who are not a visible minority (18%). This difference was driven by a higher proportion of Black people reporting a serious problem (28%) (Table 2). After controlling for other variables of interest, people belonging to a group designed as visible minority had significantly higher odds (+24%) of experiencing a serious problem compared to non-visible minorities (Model 1).

Almost one-quarter (24%) of people with household incomes of $20,000 or less reported experiencing at least one serious problem—a proportion much higher than their counterparts with higher household incomes (Table 2).

People with disabilities are much more likely than people without disabilities to experience three or more serious problems

Overall, people with disabilities were twice more likely than people without disabilities to report experiencing one or more serious problem in the past three years (33% versus 16%). The most significant differences in the types of serious problems experienced by people with disabilities compared to people without disabilities were a problem relating to poor or incorrect medical treatment (29% versus 13%), a problem with receiving disability assistance (17% versus 2%), with government assistance payments (12% versus 4%), harassment (20% versus 15%), and discrimination (19% versus 15%).

In addition, people with disabilities were much more likely than people without disabilities to report experiencing three or more problems in the three years preceding the survey. Previous research shows that people with disabilities are less likely to have some form of post-secondary education, are less likely to be participating in the labour force, and tend to have lower average personal income—all of which have been linked to an increased likelihood of experiencing multiple problems (Burlock 2017; Currie 2009; Morris et al. 2018; Turcotte 2014). In 2021, among those who experienced a serious problem, people with disabilities were far more likely than people without disabilities to experience three or more serious problems (34% versus 20%). The proportion of people with disabilities experiencing two serious problems was not statistically different from that of people without disabilities (Table 3).

Indigenous people more likely to report experiencing three or more serious problems in the past three years

Previous research has found that Indigenous people are more likely than non-Indigenous people to experience multiple serious problems (Currie 2009), and data from the CLPS also shows that this is the case. In 2021, 29% of Indigenous people who reported experiencing a problem said they faced three or more serious problems—a proportion higher than their non-Indigenous counterparts (23%) (Table 3).

Indigenous people more likely to experience harassment and discrimination

Experiencing harassment and discrimination is linked to reduced overall well-being (Todorova et al. 2010). The 2019 General Social Survey (GSS) on Victimization measured experiences of discrimination among Canadians 15 years of age and older. According to the GSS on Victimization, one in five (20%) Canadians said that they had been discriminated against or treated unfairly at least once in the five years preceding the survey. The Canadian Legal Problems Survey (CLPS) asked Canadians living in the provinces whether they had experienced a problem related to harassment or discrimination in the three years preceding the survey, and whether or not they considered these problems to be serious.

In 2021, 6% of Indigenous people living in the provinces reported experiencing a serious problem relating to harassment in the last three years, compared to 3% of non-Indigenous people (Table 4). Almost half (49%) of Indigenous people who experienced harassment said that the harassment happened in their community or neighbourhood, while 34% said that it happened online. Indigenous people were also significantly more likely than non-Indigenous people to be harassed at school (10% versus 6%), in a store, bank or restaurant (23% versus 14%), and at a government department or agency (12% versus 8%) (Table 4).

Almost four in ten (36%) Indigenous people who had experienced a serious problem related to harassment said that the harassment was based on their Indigenous identity, while 29% said that it was because of their race, colour, national or ethnic origin. Most experiences of harassment consisted of unfair treatment (72%), offensive remarks (66%), aggressive behaviour (63%), and personal attacks (61%) (Table 4).

According to the CLPS, 7% of Indigenous people reported experiencing a serious problem related to being discriminated against in the three years preceding the survey—a proportion double that of non-Indigenous people (3%) (Table 5). Notably, 45% said that it happened in a store, bank or restaurant, compared to 30% of non-Indigenous people. Almost four in ten (37%) Indigenous people said they were discriminated against at work or when applying for a job—a proportion lower than that of non-Indigenous people (43%). Nearly two-thirds (63%) of Indigenous people said that they thought they were discriminated against because of their Indigenous identity, while 44% said it was because of their race, colour, national or ethnic origin (Table 5).

Start of text box 2

Text box 2

Canadian and international studies on legal problems

To date several countries including Canada have conducted national studies on legal problems in order to identify the kinds of serious problems people face and how they attempt to resolve them. Some of the results of these surveys are provided below, it should be noted that results of these studies are not directly comparable due to differences in sampling methods, survey population, mode of collection, operational definitions and number of problems included in the survey instrument as well as overall differences in questionnaire design.

2014 National Survey of Everyday Legal Problems and Cost of Justice in Canada

- Telephone interviews with a sample of more than 3,000 respondents over the age of 18 years from the provinces.

- Questionnaire included 84 separate problems which fell into 17 categories.

- Reference period: previous three years.

- Fourth cycle of the survey, previous cycles were in the field in 2004, 2006, and 2008.

- According to this survey 45% Canadians in the provinces reported experiencing at least one serious problem and just over one-quarter (26%) of CanadiansNote who experienced a legal problem used the formal justice system to resolve it.

- About 19% of people obtained legal advice from any source (Currie 2016).

2019 Legal Needs of Individuals in England and Wales

- Online survey with a sample just under 29,000 respondents over the age 18 years from England and Wales. This sample drawn from the YouGov Panel.

- Questionnaire included 34 different legal issues.

- Reference period: previous four years.

- According to the survey, 64% of respondents experienced a serious problem and they were more likely to have experienced a contentious legal issue (53%) that a non-contentious legal issue (27%).

2020 United States Justice Needs and Satisfaction Survey

- Online survey with a sample of more than 10,000 respondents over the age of 18 from the United States.

- Reference period: previous four years.

- According to the survey two-thirds (66%) of Americans experienced a serious problem and the problem resolution rate was calculated at 49% being resolved completely.

End of text box 2

Start of text box 3

Text box 3

United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 16

This Juristat article highlights how results from legal problems surveys can contribute to indicators of access to justice, including the Global Indicator Framework (GIF) for the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDG). The United Nations 2030 Agenda and the SDGs are broad goals that 193 countries have committed to reaching by 2030.

SDG 16 reads: Promote peaceful and inclusive societies for sustainable development, provide access to justice for all and build effective, accountable and inclusive institutions at all levels.

There are 16 targets that make up SDG 16, but importantly Target 16.3 is to: Promote the rule of law at the national and international levels and ensure equal access to justice for all.

The SDGs include countries all over the world, both those considered developed and those less developed. Advocates also regard the inclusion of SDG 16 in the 2030 Agenda as a significant milestone in efforts to advance access to justice around the globe.

To support national statistical agencies with measuring progress on the SDGs, the Praia City Group on Governance Statistics was established in 2015 by the UN Statistical Commission. The Praia City Group released a Handbook in 2020 and notes in its chapter on access to and quality of justice that “approaches for people-centered justice measurement are expanding, and this will help deliver on the promise at the heart of the 2030 Agenda to ‘leave no one behind’” (Praia City Group on Governance Statistics 2020). Legal problems surveys are included as a best practice in efforts to measure progress and advance access to justice worldwide.

As part of the commitment to achieve the 17 SDGs, countries have committed to reporting on the progress through the GIF. Canada has also developed its own Canadian Indicators Framework (CIF). Until recently, there were two indicators for Target 16.3.

- Indicator 16.3.1: Proportion of victims of violence in the previous 12 months who reported their victimization to competent authorities or other officially recognized conflict resolution mechanisms.

- Indicator 16.3.2: Unsentenced detainees as a proportion of overall prison population.

The United Nations Statistical Commission meets regularly to review the indicators and propose changes which could include removing, revising or adding new indicators. In March 2020, the Commission met in New York following a comprehensive review by the UN Inter-Agency and Expert Group on SDG Indicators. Among the changes recommended and accepted was the addition of a civil justice indicator under SDG 16.3.3.

- Indicator 16.3.3: Proportion of the population who have experienced a dispute in the past two years and who accessed a formal or informal dispute resolution mechanism, by type of mechanism.

This is an important addition as three decades of legal needs/legal problems surveys around the world show that most serious problems that people experience are civil in nature, rather than criminal.

End of text box 3

Taking action to address or resolve most serious problem

The ability for citizens to resolve their most serious legal problems in a timely manner is a sign of an effective justice system. The financial, economic, and health costs of unaddressed legal problems can add up and negatively impact people’s everyday lives, including affecting their employment, personal relationships, physical and mental wellbeing, as well as their housing (Currie 2016; Currie 2009; Smith et al. 2013).

As may be expected, results from the CLPS show that people want to resolve their most serious problems. The vast majority (90%) of Canadians who experienced one or more serious problems in the three years preceding the survey reported that it was important for them to some degree to resolve the problem, with 47% stating that it was extremely important, 28% stating that it was very important, and 15% stating that it was somewhat important. Almost nine in ten (87%) Canadians reported taking some form of action to address their most serious problem (Table 6).

Majority of Canadians living in the provinces resolved their most serious problem without the use of the formal justice system

When looking at the types of action Canadians take to resolve their most serious problem, a minority—one-third (33%)—contacted a legal professional and 8% contacted a court or tribunal. This suggests that the majority of Canadians seek resolution without involving the formal justice system. It is important to note that finding a satisfactory resolution to a civil justice problem may not always require legal assistance or representation—there are a wide range of options available for resolution outside of the formal justice system (Sandefur 2019). Among those who did not use the formal justice system to resolve their most serious problem, the most common actions taken were, obtaining advice from friends or relatives (51%), searching the internet (51%), and contacting the other party involved in the dispute (47%). Another 21% contacted a government department or agency, 11% contacted a community centre or community organization, and 4% contacted a labour union (Table 6).Note

Barriers to accessing justice

The formal justice system may not be the best avenue to resolve all types of civil justice problems. Some problems (such as landlord-tenant disputes or consumer-related problems) may not require legal representation and court or administrative processes to come to a fair and effective resolution (Currie 2009; Sandefur 2019). However, some problems that do require resolution via the formal justice system are not resolved because of barriers that prevent individuals from accessing justice. Legal needs surveys like the CLPS help policy makers better understand what these barriers are and highlight inequalities surrounding equal access to justice (OECD 2019).

Research to date has noted that the high cost of legal representation, the time required to resolve a case, the complexity of navigating the justice system, a lack of knowledge about available services, and a lack of available services as key barriers to accessing justice (Currie 2016; OECD 2019; The Canadian Bar Association 2013). Further, certain populations may face additional barriers to accessing justice and resolving legal problems, such as literacy and language barriers, and perceived discrimination or bias. The overrepresentation of Indigenous peoples in the criminal justice system is often attributed to the negative consequences of colonialism, including systemic racism and discrimination (Wortley and Owusu-Bempah 2011; MMIWG 2019).Note

Respondents who did not take any action to resolve their most serious legal problem were asked a series of questions about the reasons why. Of the 12% of people who took no action, slightly more than half (53%) said that they did not think anything could be done about the problem (Table 6). Other commonly reported reasons were that they thought it would make the problem worse (19%), they did not know what to do or where to get help (18%), and they thought the process would be too stressful (18%). In general, more than half (52%) of Canadians who experienced a serious problem said that they did not understandNote the possible legal implications when they first became aware of their problem.

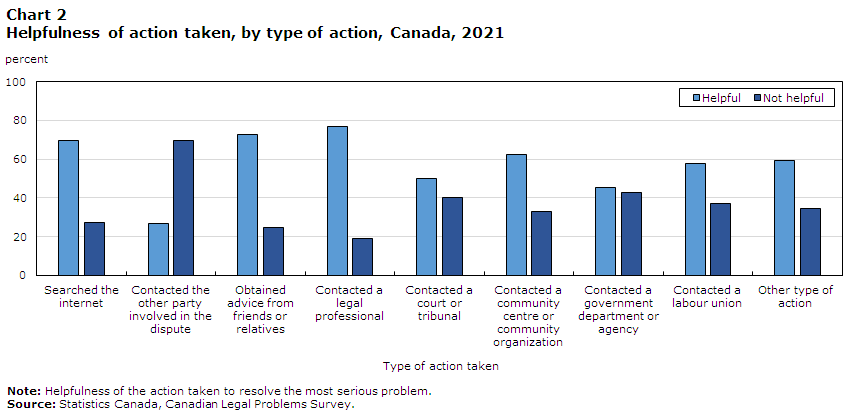

Among those who did take action, perceptions of the helpfulness of the action varied. For example, seven in ten (70%) people who contacted the other party involved in the dispute said that it was not helpful in resolving their most serious problem (Chart 2). However, most helpful actions reported included contacting a legal professional (77%), obtaining advice from friends or relatives (73%) and searching the internet (70%).

Chart 2 start

Data table for Chart 2

| Type of action taken | Helpful | Not helpful |

|---|---|---|

| percent | ||

| Searched the internet | 70 | 27 |

| Contacted the other party involved in the dispute | 27 | 70 |

| Obtained advice from friends or relatives | 73 | 25 |

| Contacted a legal professional | 77 | 19 |

| Contacted a court or tribunal | 50 | 40 |

| Contacted a community centre or community organization | 63 | 33 |

| Contacted a government department or agency | 45 | 43 |

| Contacted a labour union | 58 | 37 |

| Other type of action | 59 | 35 |

|

Note: Helpfulness of the action taken to resolve the most serious problem. Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Legal Problems Survey. |

||

Chart 2 end

Among those who took action to resolve their most serious problem but did not contact a lawyer, over one-third (37%) said that they could not afford legal help. Further, four in ten (41%) stated that they did not think legal help would be useful in solving their problem. One-third (33%) of respondents who did not contact a lawyer wanted to resolve their problem on their own.

Start of text box 4

Text box 4

Impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on access to justice

The data collection for the CLPS took place from February to August 2021. During this time, COVID-19 spread at different rates across the country, with some provinces and territories imposing stricter restrictions than others. The COVID-19 pandemic continues to disrupt the everyday lives of Canadians, and has had an impact on access to justice in Canada. In order to respect public health guidelines, courts and tribunals have provided more limited access to services at various times during the pandemic. In addition to limiting legal services, the COVID-19 pandemic has created new problems for some Canadians or has exacerbated existing problems.

Data from the CLPS show that more than four in ten (42%) Canadians who reported experiencing at least one serious problem in the three years preceding the survey said that their serious dispute or problem worsened or became more difficult to resolve as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. There was no significant difference between the problems reported by women (43%) and men (42%).

Almost four in ten (39%) Canadians who reported experiencing at least one serious problem said that their problem happened during the COVID-19 pandemic (after March 16, 2020). While these problems were not necessarily direct results of the COVID-19 pandemic or associated restrictions, the most commonly reported serious problems that happened during the pandemic were employment-related problems (82%), a problem related to discrimination (77%), problems involving a will or taking care of financial or health issues for a person unable to do so themselves (75%), and housing-related problems (79%).

Analysis on the economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic shows that Indigenous people, visible minorities and immigrants were more likely than their counterparts to report that the pandemic had a negative impact on their finances (Arriagada et al. 2020; Hou et al. 2020; LaRochelle-Côté and Uppal 2020). Of those who experienced at least one serious problem, more than four in ten (43%) Indigenous people said that at least one serious problem happened after the COVID-19 pandemic was declared a public health emergency in March 2020—a proportion significantly higher than non-Indigenous people (39%). Further, Indigenous people were also more likely to say that their serious problem worsened as a result of the pandemic (48% versus 42% of non-Indigenous people).

End of text box 4

Financial, socio-economic and health impacts stemming from serious problems

Research shows that experiencing one or more serious problems can have severe negative consequences on the mental and physical well-being, personal relationships, and financial security of individuals. Experiencing a serious problem may also create new, additional problems, further compounding these negative effects (Currie 2009; Pleasence 2006). In addition to questions about the types of problems Canadians experience and the actions they take to address or resolve these problems, the Canadian Legal Problems Survey (CLPS) also asked Canadians about the impacts of these problems on their daily lives. Impacts were broken down into three categories: financial impacts, socio-economic impacts, and health impacts.

Three-quarters of Canadians experience financial impacts resulting from their most serious problem

Three-quarters (75%) of Canadians who had experienced a serious problem said that they were impacted financially as a result of their most serious problem. The most commonly reported financial impacts were having to spend savings (49%), having to put expenses on a credit card (35%) and having to borrow money from family and friends (21%) (Table 7). These proportions were similar among women and men.

Women far more likely than men to report negative health impacts stemming from their most serious problem

The vast majority (79%) of Canadians said that their most serious problem contributed to some type of adverse health impact, and women were significantly more likely than men to report each type of health impact measured in the CLPS, as well as any sort of health problem overall (85% versus 72%) (Table 7). Among both women and men who experienced at least one serious problem, extreme stress was by far the most commonly reported health impact, yet women were significantly more likely than men to cite extreme stress (79% versus 65% of men).

Indigenous people more likely than non-Indigenous people to be negatively impacted by their most serious problem

Overall, three-quarters (75%) of Indigenous people reported experiencing some type of financial impact as a result of their most serious problem—the same proportion as that of non-Indigenous people (75%). Indigenous people were significantly more likely to state that they had to borrow money from friends or relatives (32%, versus 21% of non-Indigenous people), that they had to borrow money from a credit or loan agency (11% versus 6%), and that they had to miss a payment on bills or pay them late (32% versus 20%). Indigenous people were twice as likely as their non-Indigenous counterparts to say that their most serious problem caused or contributed to losing their housing (10% versus 5%). Socio-economic disparities stemming from the impacts of the historical oppression of Indigenous peoples have created greater financial burdens among Indigenous peoples.

More than eight in ten (82%) Indigenous people who had experienced at least one serious problem said that they faced health impacts as a result of their most serious problem, a proportion higher than that of non-Indigenous people (79%). When it came to specific health impacts, 56% of Indigenous people said that they experienced a mental health problem as a result of the problem, 49% experienced social, family, or personal issues, and 38% reported a physical health problem. These proportions were all higher than those of non-Indigenous people (45%, 40%, and 32%, respectively). Indigenous people were as likely as non-Indigenous people to report experiencing extreme stress as a result of their most serious problem (76% versus 72%).

Canadians who experienced three or more serious problems more likely to cite negative impacts from most serious problem

According to the CLPS, Canadians who experienced more than one serious problem within a three year period were more likely to experience a wide range of financial, socio-economic and health impacts. Just over three-quarters (72%) of Canadians who experienced one serious problem in the three years preceding the survey reported a health impact as a result of their most serious problem, compared with 82% of those who experienced two serious problems and 92% of those who experienced three or more serious problems (Table 8).

Extreme stress was the most commonly reported health impact, regardless of the number of problems experienced. As the number of problems experienced increased, so did the proportion of respondents reporting extreme stress. This was true across all types of health impacts.

Canadians experiencing three or more serious problems were more than twice as likely as those reporting one serious problem to report physical health problems as a result of their most serious problem (54% versus 24%) and much more likely to report mental health problems (67% versus 35%) (Table 8, Chart 3).

Chart 3 start

Data table for Chart 3

| One serious problemData table for Chart 3 Note † | Two serious problems | Three or more serious problems | |

|---|---|---|---|

| percent | |||

| Health impacts (total) | 72 | 82Note * | 92Note * |

| Physical health problem(s) | 24 | 33Note * | 54Note * |

| Mental health problem(s) | 35 | 48Note * | 67Note * |

| Social, family, or personal issues | 32 | 41Note * | 58Note * |

| Extreme stress | 64 | 76Note * | 87Note * |

|

|||

Chart 3 end

Almost nine in ten (86%) people who experienced three or more serious problems in the three years preceding the survey said that they experienced at least one financial impact as a result of their most serious problem (Table 8). People with three or more problems were twice as likely as people with one problem to have borrowed money from the bank (10% versus 4%) and were significantly more likely to have put expenses on a credit card (48% versus 29%). Further, more than six in ten (62%) Canadians who experienced three or more problems said that they had to spend their savings and one-third (33%) had to miss payments on bills or pay them late (Table 8).

The majority of serious problems remain unresolved

Overall, two in ten (21%) serious problems in the Canadian provinces had been resolved at the time of the survey. The proportion of resolved problems ranged from 16% in New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island to 24% in Newfoundland and Labrador (Table 9). Just under two in ten (19%) of problems in the Canadian provinces were in the process of being resolved. A higher proportion of Canadians living in Quebec (13%), Alberta (13%) and Ontario (12%) stated that they gave up trying to resolve their most serious problem.

The percentage of cases resolved also varied depending on the type of problem. The problems with the highest proportion of resolved cases were contact with the police or other part of criminal justice system involving being stopped, accused, charged, detained or arrested (53%E), a will or taking care of financial or health issues for a person unable to do so themselves (46%), and problems with an employer or job (37%) (Table 10).

People who had problems related to a large purchase or service or problems obtaining social or housing assistance were the most likely to report giving up on resolving their serious problem (31% and 25%, respectively).

Start of text box 5

Text box 5

A qualitative look at serious legal problems

Quantitative studies measuring the frequency and type of serious legal problems are important in providing a broad overview of the problems experienced by Canadians. However, qualitative studies are also extremely valuable in providing a better understanding of the types of problems specific to different population groups.

A Qualitative Look at Serious Legal Problems is the overarching title for a series of qualitative research studies undertaken by the Department of Justice Canada in 2020-2021Note aimed towards complementing the results from the CLPS. The studies explore access to justice issues experienced by minority populations in different parts of Canada. The five streams of research are:

- LGBTQ2S+ populations;

- Black Canadians;

- Persons with disabilities;

- Immigrants; and

- Indigenous people.

These studies are important because they qualitatively document peoples’ experiences of serious legal problems—what those problems are; how they have tried to resolve them and the outcomes; and the financial, emotional and physical impacts of those problems. Almost all the studies began at the outset of COVID-19 and data collection continued throughout 2020. As the months went by, it also became more evident that the COVID-19 crisis was having the greatest effect on the poorest and most marginalized populations in Canada.

The study participants are people from different ethnic origins and cultures, abilities, immigration statuses and sexual and gender identities. Each participant has their own identity and yet, many of the stories had similar themes. Barriers to access to justice on a whole range of matters included:

- finding accurate information;

- technical language and legalese;

- accessing assistance and representation;

- lack of time to address the problems;

- lack of legal aid coverage for their particular problem;

- perceptions of success;

- fear of consequences, particularly in cases of discrimination or family matters where there was violence; and

- experiencing multiple problems at the same time.

End of text box 5

Summary

This Juristat article presents initial findings from the 2021 Canadian Legal Problems Survey (CLPS), including the frequency and types of serious problems that Canadians experience, the actions they take to address or resolve these problems, and the impacts these problems have on their daily lives. The data collected through the CLPS fill an important data gap by providing a better understanding of the various formal and informal methods people use to resolve their serious problems and issues related to access to justice for Canadians.

In 2021, slightly more than one-third (34%) of Canadians reported experiencing one or more problems in the previous three years, with 18% stating that these problems were serious or not easy to fix. The most commonly reported serious problems experienced by Canadians were: obtaining social or housing assistance or other government assistance (21%), receiving poor or incorrect medical treatment (16%), being harassed (16%), being discriminated against (16%), and a problem with a large purchase or service (15%).

The majority (87%) of Canadians who experience a serious problem take action to resolve their most serious legal problems, but most choose to resolve them outside of the formal justice system. The most commonly reported actions taken were searching the internet (51%), obtaining advice from friends or relatives (51%), and contacting the other party involved in the dispute (47%). One-third (33%) of affected Canadians contacted a legal professional to help address and resolve their problems.

Of those who chose not to take any action towards resolving their most serious problem, slightly over half (53%) said that they did not think anything could be done about the problem. Other commonly reported reasons were that they thought it would make the problem worse (19%), they did not know what to do or where to get help (18%), and they thought the process would be too stressful (18%).

Across the provinces, 21% of cases were resolved at the time of the survey, with an additional 19% in progress. The proportion of cases resolved varied depending on the province, ranging from 16% in New Brunswick to 24% in Newfoundland and Labrador.

Most Canadians who experienced at least one serious problem stated that their most serious problem impacted them financially. Seven in ten (68%) people who experienced one serious problem experienced a financial impact as a result of their most serious problem, compared to 77% of people who experienced two serious problems and 86% of people who experienced three or more serious problems.

Detailed data tables

Table 8 Reported impacts resulting from most serious problem, by number of problems, provinces, 2021

Model 1 Logistic regression: odds of experiencing one or more serious problem, provinces, 2021

Survey description

In 2021, Statistics Canada conducted the first cycle of the Canadian Legal Problems Survey (CLPS). The purpose of the Canadian Legal Problems Survey (CLPS) is to identify the kinds of serious problems people face, how they attempt to resolve them, and how these experiences may impact their lives. The target population for the CLPS is the Canadian population aged 18 years of age and older living in one of Canada’s 10 provinces, with the exception of those residing in institutions.

Data collection took place from February to August, inclusively. Responses were obtained by self-administered online questionnaire or by interviewer-administered telephone questionnaire. Respondents were able to respond in the official language of their choice.

The sample size for the 10 provinces was 21,170 respondents. The overall response rate was 50.3%. Respondents in the sample were weighted so that their responses represent the non-institutionalized Canadian population aged 18 and older.

Data limitations

As with any household survey, there are some data limitations. The results are based on a sample and are therefore subject to sampling errors. Somewhat different results might have been obtained if the entire population had been surveyed.

For the quality of estimates, the lower and upper bounds of the confidence intervals are presented. Confidence intervals should be interpreted as follows: if the survey were repeated many times, then 95% of the time (or 19 times out of 20), the confidence interval would cover the true population value.

References

Arriagada, P., Hahmann, T. and V. O’Donnell. 2020. “Indigenous people in urban areas: Vulnerabilities to the socioeconomic impacts of COVID-19.” StatCan COVID19: Data Insights for a Better Canada. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 45-28-0001.

Burlock, A. 2017. “Women with disabilities.” Women in Canada: A Gender-based Statistical Report. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 89-503-X.

Canadian Bar Association. 2013. Reaching Equal Justice Report: An Invitation to Envision and Act.

Cotter, A. Forthcoming 2022. “Perceptions of and experiences with police and the justice system among the Black and Indigenous populations in Canada.” Juristat. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 85-002-X.

Currie, A. 2009. The Legal Problems of Everyday Life - The Nature, Extent and Consequences of Justiciable Problems Experienced by Canadians. Department of Justice Canada. Ottawa, Ontario.

Currie, A. 2016. Nudging the Paradigm Shift, Everyday Legal Problems in Canada. Canadian Forum on Civil Justice. Toronto, Ontario.

Department of Justice Canada. 2019. National Justice Survey 2018.

Farrow, T. C. W. 2014. “What is access to justice?” Osgoode Hall Law Journal. Vol. 51, no. 3. p. 957-988.

Farrow, T. C. W., Currie, A., Aylwin, N., Jacobs, L., Northrup, D. and L. Moore. 2016. Everyday Legal Problems and the Cost of Justice in Canada: Overview Report. Canadian Forum on Civil Justice. Toronto, Ontario.

Genn, H. 1999. Paths to Justice: What People Do and Think about Going to Law. Oxford. p. 12.

Hou, F., Frank, K. and C. Schimmele. 2020. “Economic impact of COVID-19 among visible minority groups.” StatCan COVID19: Data Insights for a Better Canada. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 45-28-0001.

LaRochelle-Côté, S. and S. Uppal. 2020. “The social and economic concerns of immigrants during the COVID-19 pandemic.” StatCan COVID19: Data Insights for a Better Canada. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 45-28-0001.

Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (MMIWG). 2019. Reclaiming Power and Place: The Final Report of the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls.

Morris, S., Fawcett, G., Brisebois, L. and J. Hughes. 2018. “A demographic, employment and income profile of Canadians with disabilities aged 15 years and over, 2017.” Canadian Survey on Disability Reports. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 89-654-X.

Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). 2019. Legal Needs Surveys and Access to Justice. OECD Publishing. Paris.

Pleasence, P., Balmer, N. J., Buck, A., O’Grady, A. and H. Genn. 2004. “Multiple justiciable problems: Common clusters and their social and demographic indicators.” Journal of Empirical Legal Studies. Vol. 1, no. 2. p. 301-329.

Pleasence, P. 2006. Causes of Action: Civil Law and Social Justice. 2nd edition. The Stationery Office. Norwich.

Pleasence, P. 2016, ’Legal Need’ and Legal Needs Surveys: A Background Paper. NAMATI.

Praia City Group on Governance Statistics. 2020. Handbook on Governance Statistics. New York, UN Statistical Commission. p. 101.

Sandefur, R. 2014. Accessing Justice in the Contemporary USA: Findings from the Community Needs and Services Study. American Bar Foundation. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

Sandefur, R. 2019. “Access to what?” Massachusetts Institute of Technology Press.

Smith, M., Buck, A., Sidaway, J. and L. Scanlan. 2013. “Bridging the Empirical Gap: New Insights into the Experience of Multiple Legal Problems and Advice Seeking.” Journal of Empirical Legal Studies. Vol. 10, no. 1. p. 146-170.

The Hague Institute for Innovation of Law. 2021. Justice Needs and Satisfaction in the United States of America: Legal Problems in Daily Life.

Todorova, I., Falcon, L., Lincoln, A. and L. Price. 2010. “Perceived discrimination, psychological distress and health.” Sociology of Health and Illness. Vol. 32, no. 6. p. 843-861.

Trebilcock, M., Duggan, A. and L. Sossin. 2012. “Middle income access to justice.” University of Toronto Press. Toronto, Ontario.

Turcotte, M. 2014. “Persons with disabilities and employment.” Insights on Canadian Society. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 75-006-X.

Wortley, S. and A. Owusu-Bempah. 2011. “The usual suspects: Police stop and search practices in Canada.” Policing and Society. Vol. 21, no. 4. p. 395-407.

- Date modified: