Criminal victimization of First Nations, Métis and Inuit people in Canada, 2018 to 2020

Archived Content

Information identified as archived is provided for reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It is not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards and has not been altered or updated since it was archived. Please "contact us" to request a format other than those available.

Released: 2022-07-19

Indigenous people are more likely to have experienced violence in their lifetime

First Nations people, Métis and Inuit are overrepresented among victims of violence in Canada. Previous research has suggested a link between this violent victimization and past and present colonial policies, including the residential school system, marginalization and institutionalized racism. These policies have resulted in the disruption of community and family structures, as well as resulted in intergenerational trauma, which are also both linked to violent victimization of Indigenous people.

Overall, approximately 4 in 10 Indigenous people (41%) were sexually or physically assaulted by an adult before the age of 15, and nearly two-thirds (62%) experienced at least one sexual or physical assault after the age of 15. By comparison, these proportions were 25% and 42%, respectively, for non-Indigenous people. Indigenous people were also twice as likely as non-Indigenous people to report being the victim of a violent crime in the 12 months preceding the survey (8.4% compared with 4.2%). For the period from 2015 to 2020, the rate of homicides involving an Indigenous victim (8.64 homicides per 100,000 Indigenous people) was six times higher than the rate of homicides involving non-Indigenous victims (1.39 per 100,000 non-Indigenous people).

Results from the 2019 General Social Survey (GSS) on Canadians' Safety (Victimization), the 2018 Survey of Safety in Private Spaces (SSPPS), and the 2020 Homicide Survey are being released today in the Juristat article entitled "Victimization of First Nations people, Métis and Inuit in Canada." This article examines Indigenous people's experiences based on self-reported violent victimization and police-reported data on homicides. The article also looks at perceptions of the justice system and feelings of safety. It follows on an earlier article entitled "Violent victimization and perceptions of safety: Experiences of First Nations, Métis and Inuit women in Canada."

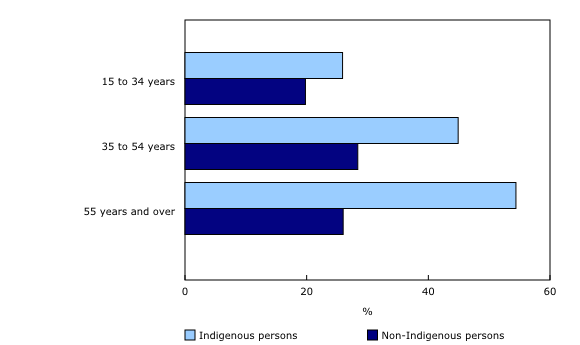

Indigenous people aged 35 years and older are more likely to have experienced sexual or physical violence during childhood, while younger Indigenous people are less likely

Around 4 in 10 Indigenous people (41%, or 42% of First Nations people, 39% of Métis, and 45% of Inuit) aged 15 years and older reported experiencing sexual or physical violence by an adult before the age of 15. In contrast, 25% of non-Indigenous people reported experiencing violence during childhood. More specifically, 36% of Indigenous people experienced physical violence and 16% experienced sexual violence. Among non-Indigenous people, these proportions were 22% and 6%, respectively.

This difference between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people was mainly observed among older persons. More than half (54%) of Indigenous people aged 55 years and older and 45% of those aged 35 to 54 years reported experiencing violence during childhood. Among Indigenous people aged 15 to 34 years, this proportion decreased to 26%, which is similar to that of non-Indigenous people of the same age.

Indigenous people were also overrepresented among people who had previously been under the responsibility of child protection services. Around 1 in 10 Indigenous people (11%, or 15% of First Nations people, 7.3% of Métis, and 19% of Inuit) reported that they had been under the responsibility of the government before the age of 15, compared with 1.3% of non-Indigenous people. Many of these individuals, particularly Indigenous people, experienced physical or sexual violence during that time, as more than one-third (34%) of individuals 15 years and older who experienced childhood violence while under the custody of the government were Indigenous.

Indigenous people were twice as likely as non-Indigenous people to be victims of violent crime in the 12 months preceding the survey

Nearly 1 in 10 Indigenous people (8.4%, or 5.5% of First Nations people, 11.7% of Métis, and 11.5% of Inuit) reported being victims of at least one sexual assault, robbery or physical assault in the 12 months preceding the 2019 GSS. This is double the proportion for non-Indigenous people (4.2%).

Among both Indigenous and non-Indigenous people, certain groups had higher rates of victimization. This was particularly true for young adults, people who experienced violence during childhood, people with a history of homelessness, people who have experienced discrimination, and LGBTQ2+ people. After controlling for these factors as well as other socioeconomic factors, the risk of victimization among Indigenous and non-Indigenous people was similar.

Indigenous victims were more likely than non-Indigenous victims to have reported the most serious assault they had experienced to the police during the year (39% compared with 18%). This higher reporting rate may be partly due to the greater seriousness of some assaults, with Indigenous victims being injured more often (36% compared with 12% of non-Indigenous victims) or having faced an armed assailant (32% compared with 13%). Indigenous victims were also more likely to have experienced aftereffects of an assault, such as symptoms compatible with post-traumatic stress disorder, withdrawing from social activities, or staying at home.

In 10 years, the rate of spousal violence has fallen by half among Indigenous women

In the provinces, Indigenous people who had a partner or an ex-partner in the five years prior to the 2019 GSS were around twice as likely as non-Indigenous people to have experienced spousal violence during that time (6.9% compared with 3.4%). Specifically, 7.5% of Indigenous women and 6.2% of Indigenous men reported experiencing spousal violence. Among women, this proportion is around half of the proportion in 2009 (15%).

When factoring in all intimate relationships (i.e., spouses and other types of intimate partners), about one in seven Indigenous people (14%, or 12% of First Nations people, 15% of Métis and 22% of Inuit) had experienced violence from an intimate partner in the five years preceding the survey.

Indigenous people are around six times more likely than non-Indigenous people to be the victims of homicide

From 2015 to 2020, the average rate of homicides involving an Indigenous victim was six times higher than the rate of homicides involving non-Indigenous victims (8.64 Indigenous victims per 100,000 Indigenous people compared with 1.39 per 100,000 non-Indigenous people). Among the provinces, Saskatchewan (17.57 per 100,000 Indigenous people), Manitoba (14.46 per 100,000 Indigenous people), and Alberta (13.24 per 100,000 Indigenous people) had the highest rates of homicide involving an Indigenous victim. Yukon (20.43 per 100,000 Indigenous people) had the highest rate among the territories.

During this period, the majority of homicides involving an Indigenous victim that were solved by police were committed by a person known to the victim (91% of Indigenous victims compared with 81% of non-Indigenous victims). Moreover, one in six homicides were committed by an intimate partner, and more Indigenous women (42%) than Indigenous men (7.1%) were killed by an intimate partner.

People who have been victims of violence in their lifetime are more likely to experience other social or health issues

Overall, nearly two-thirds (62%, or 61% of First Nations people, 64% of Métis, and 51% of Inuit) reported experiencing at least one sexual or physical assault in their lifetime. By comparison, this proportion was 42% among non-Indigenous people.

Among both Indigenous and non-Indigenous people, individuals who had experienced an assault in their lifetime were more likely to report experiencing other social issues than those who had not experienced an assault. For example, Indigenous people who had experienced an assault were more likely to have seriously considered suicide (41% versus 16% of Indigenous people who had not experienced an assault), have a low level of satisfaction with their lives as a whole (24% compared with 9%) or have been homeless in the past (37% compared with 10%).

About three-quarters of Indigenous people report that they are satisfied with their personal safety from crime

Despite higher victimization rates, Indigenous people (76%, or 73% of First Nations people, 78% of Métis, and 71% of Inuit) reported being generally satisfied or very satisfied with their personal safety from crime at a similar proportion as non-Indigenous people (78%). This proportion was lower for women (69% of Indigenous women and 74% of non-Indigenous women) than for men (82% for both Indigenous and non-Indigenous men).

However, Indigenous people were more critical of the criminal justice system. They were more likely than non-Indigenous people to report having no confidence in their local police service (17% compared with 10%) or in criminal courts (30% compared with 20%). In addition, among people who had contact with police at least once during the year, Indigenous people were more likely to report that their experience was negative (18% compared with 12%). Indigenous people also accounted for 21% of people who reported experiencing discrimination by police in previous years.

Note to readers

This Juristat article is based on results from the 2019 General Social Survey (GSS) on Canadians' Safety (Victimization) and the 2018 Survey of Safety in Public and Private Spaces (SSPPS). In addition, some findings from the Homicide Survey are included. A similar study dealing specifically with Violent victimization and perceptions of safety: Experiences of First Nations, Métis and Inuit women in Canada is also available.

The main objective of the GSS on Canadians' Safety is to better understand issues related to the safety and security of Canadians, including perceptions of crime and the justice system, experiences of intimate partner violence, and how safe people feel in their communities.

In the GSS, self-reported violent victimization is defined as:

Sexual assault: Forced sexual activity; attempted forced sexual activity; unwanted sexual touching, grabbing, kissing or fondling; or sexual relations without being able to give consent.

Robbery: Theft or attempted theft in which the offender had a weapon or there was violence or the threat of violence against the victim.

Physical assault: An attack (being hit, slapped, grabbed, pushed, knocked down, or beaten), a threat of physical harm, or an incident with a weapon present.

Due to changes to collection methods, it is not recommended to compare 2019 GSS results with results from previous GSS cycles, except for the results on spousal violence.

The SSPPS collected information on Canadians' self-reported experiences of violent victimization since the age of 15 ("lifetime violent victimization"). In the SSPPS, violent victimization includes physical assault and sexual assault.

The target population for both the GSS and the SSPPS was persons aged 15 and older living in the provinces (including on-reserves) and territories, except for those living full-time in institutions.

In the GSS and SSPPS, Indigenous people include those who reported being First Nations, Métis or Inuit. Respondents could indicate belonging to more than one Indigenous group. They are included in each group they reported belonging to. In the Homicide Survey, Indigenous people include victims identified as being First Nations, Métis, Inuit or belonging to an Indigenous group not known to police. Indigenous identity is reported by the police and is determined through information found on the victim (such as status cards) or through information supplied by the victims' families, community members, or other sources.

Products

The article "Victimization of First Nations people, Métis and Inuit in Canada" is now available as part of the publication Juristat (85-002-X).

Contact information

For more information, or to enquire about the concepts, methods or data quality of this release, contact us (toll-free 1-800-263-1136; 514-283-8300; infostats@statcan.gc.ca) or Media Relations (statcan.mediahotline-ligneinfomedias.statcan@statcan.gc.ca).

- Date modified: