Labour Force Survey, July 2017

Archived Content

Information identified as archived is provided for reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It is not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards and has not been altered or updated since it was archived. Please "contact us" to request a format other than those available.

Released: 2017-08-04

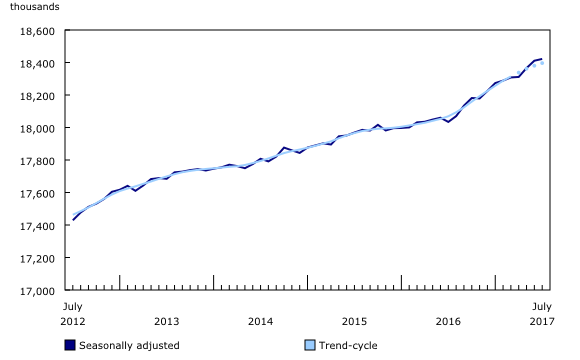

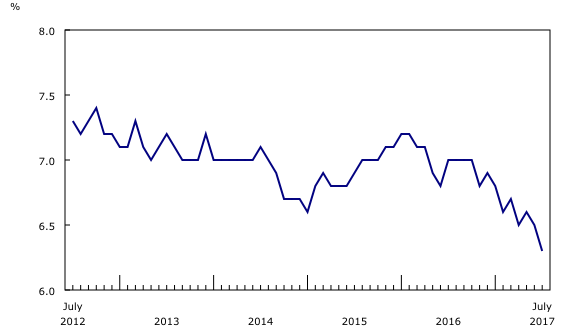

Following two months of notable increases, employment was little changed in July (+11,000 or +0.1%). As the number of people searching for work edged down, the unemployment rate declined by 0.2 percentage points to 6.3%. This is the lowest rate since October 2008, just prior to the onset of the 2008-2009 labour market downturn.

In the 12 months to July, employment rose by 388,000 (+2.1%), mostly the result of increases in full-time work (+354,000 or +2.4%). Over this period, the number of hours worked increased by 1.9%.

Highlights

In July, employment increased among women aged 55 and older. There was little employment change among the other demographic groups.

Employment increased in Ontario and Manitoba, while it declined in Alberta, Newfoundland and Labrador as well as in Prince Edward Island.

More people were employed in wholesale and retail trade; information, culture and recreation; manufacturing; transportation and warehousing; and natural resources. At the same time, employment fell in educational services, public administration and agriculture.

Employment increases for women aged 55 and older

Employment increased for a second consecutive month for women aged 55 and older, up 14,000 in July. Their unemployment rate was little changed at 5.4%. Compared with 12 months earlier, employment for this group grew by 66,000 (+3.9%).

For men aged 55 and older, employment held steady in July. The unemployment rate for men in this age group declined 0.7 percentage points to 5.3%, as fewer of them searched for work. On a year-over-year basis, employment for men aged 55 and older increased by 69,000 (+3.4%).

Among workers aged 55 and older, 8 out of 10 were between the ages of 55 and 64. The estimated year-over-year employment growth rate for this group (unadjusted for seasonality) was 2.9%, relatively in line with their population increase (+2.1%). In comparison, people aged 65 and older comprised a smaller share of older workers, but their proportion has been increasing over the past decade. This group had the fastest year-over-year employment growth rate among the major demographic groups in July, rising 7.3% and outpacing their rate of population growth (+3.7%). For more information about recent trends among older workers, see "The impact of aging on labour market participation rates."

Core-age and youth employment little changed

Employment for people aged 25 to 54 held steady in July. The unemployment rate increased 0.2 percentage points to 5.6%, as more core-aged women searched for work. Compared with 12 months earlier, employment among men and women in this age group rose by 173,000 (+1.5%), with most of the gains occurring from October 2016 to March 2017.

In July, employment for youth aged 15 to 24 was little changed. As fewer youth searched for work, their unemployment rate fell 0.9 percentage points to 11.1%, the lowest rate since August 2008. On a year-over-year basis, youth employment was up by 80,000 (+3.3%).

Employment increases in Ontario and Manitoba

Employment in Ontario rose by 26,000 in July, and the unemployment rate fell 0.3 percentage points to 6.1%. Compared with 12 months earlier, employment in the province was up 138,000 (+2.0%), with most of the increase in full-time work.

In Manitoba, the number of people working increased by 4,800 in July, continuing an upward trend that began in January. The unemployment rate declined by 0.3 percentage points to 5.0%, the lowest rate among the provinces, and the lowest recorded in Manitoba since October 2014. On a year-over-year basis, employment in the province rose by 13,000 (+2.1%), mainly in full-time work.

Overall employment in Quebec was little changed in July, as increases in full-time work were mostly offset by declines in part-time employment. In the 12 months to July, employment in the province was up 124,000 (+3.0%) and the unemployment rate fell 1.2 percentage points to 5.8%, the lowest rate since comparable data became available in 1976.

Employment in New Brunswick was little changed on both a monthly and year-over-year basis. As fewer people participated in the labour market, the unemployment rate declined by 1.6 percentage points to 6.5% in July, the lowest rate since comparable data became available in 1976. Since the start of 2017, unemployment has fallen in New Brunswick, while employment has been relatively unchanged. As a result, both the total labour force and the unemployment rate have fallen sharply.

Following three months of little change, employment declined by 14,000 in Alberta, and the unemployment rate increased 0.4 percentage points to 7.8% in July. Despite this decline, employment in the province increased by 35,000 (+1.5%) compared with 12 months earlier, led by gains in natural resources.

In Newfoundland and Labrador, the number of workers fell by 5,300 in July, continuing a long-term downward trend, which has become more pronounced since 2016. The unemployment rate rose 0.8 percentage points to 15.7%, the highest rate since April 2010. In the 12 months to July, employment in the province declined by 13,000 (-5.4%).

Employment in Prince Edward Island was down by 1,000 in July, and the unemployment rate was little changed at 10.0% as fewer people participated in the labour market. On a year-over-year basis, employment in the province increased by 2,100 (+2.9%).

Employment gains in several industries

In July, employment in wholesale and retail trade increased by 22,000 (+0.8%). Employment in the industry has trended upwards since the latter part of 2016, coinciding with higher sales reported at both the wholesale and retail level. On a year-over-year basis, employment in this industry rose by 94,000 (+3.4%).

Employment in information, culture and recreation was up by 18,000 in July, but was little changed compared with 12 months earlier.

The number of people working in manufacturing rose by 14,000 in July, the third notable gain in five months. The increase in July was mainly in Quebec. Compared with 12 months earlier, national employment in this industry was up by 53,000 (+3.1%).

In transportation and warehousing, employment increased by 8,400 in July, largely in Ontario. On a year-over-year basis, employment in this industry rose by 33,000 (+3.6%).

In July, employment declined by 32,000 in educational services, mainly in Ontario and Alberta. Nationally, the decrease was largely in primary and secondary schools. Compared with July 2016, employment in this industry was virtually unchanged.

Employment in public administration fell by 10,000 in July. Despite this decline, employment in this industry increased by 48,000 (+5.3%) compared with 12 months earlier, with the bulk of the increase occurring in the second half of 2016.

In agriculture, employment also decreased by 10,000 in July, bringing total losses to 16,000 (-5.3%) on a year-over-year basis.

The number of employees in the private and public sectors was little changed in July. Compared with 12 months earlier, the number of private sector employees increased by 221,000 (+1.9%), while public sector employment rose by 135,000 (+3.8%).

The number of self-employed workers was little changed both on a monthly and year-over-year basis.

Summer employment for students

From May to August, the Labour Force Survey collects labour market data on youths aged 15 to 24 who were attending school full time in March and who intend to return full time in the fall. Published data are not seasonally adjusted; therefore, comparisons can only be made on a year-over-year basis.

In July, employment among students aged 15 to 24 rose 113,000 (+9.1%) compared with July 2016. From July 2010 to July 2016, employment for this group had declined by 80,000 (-6.0%), reaching a recent low point in 2016 (see Chart 8 in the Labour Force Information publication). In the 12 months to July 2017, their unemployment rate declined 2.5 percentage points to 13.9%, the lowest rate since 2008.

For students aged 20 to 24, employment increased by 39,000 (+7.6%) compared with 12 months earlier. At the same time, their unemployment rate edged down 1.3 percentage points to 6.8%, a similar rate to the one observed in July 2008.

Employment for students aged 17 to 19 was up by 62,000 (+12.1%) compared with July 2016, when employment for these students reached a recent low point. In the 12 months to July, the unemployment rate for 17- to 19-year-old returning students fell 3.4 percentage points to 13.9%, the lowest rate for the month of July since 2008.

Compared with 12 months earlier, employment increased by 12,000 (+5.6%) for students aged 15 and 16, and the unemployment rate edged down 2.4 percentage points to 27.9%.

In celebration of the country's 150th birthday, Statistics Canada is presenting snapshots from our rich statistical history.

Labour force participation of seniors

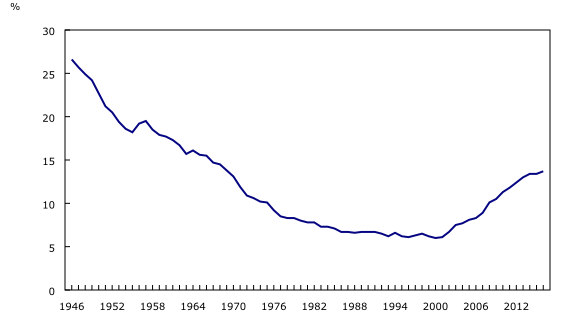

Like many other industrialized countries, the age structure of the Canadian population has changed dramatically in the last century. The proportion of seniors aged 65 and older who participate in the labour market has also changed substantially over this time.

In 1921, the Census of Population found that about one-third (33.7%) of those aged 65 and older were either employed or looking for work. At this time, income support programs for seniors were rare; the Old Age Security Program, for example, would not be introduced until 1927.

In 1946, following the Second World War, the first Labour Force Survey data indicated that 26.6% of seniors participated in the labour market. In subsequent decades, the labour force participation rate of seniors continued to decline, reaching a low in the period from 1986 to 2002, when the rate varied between 6% and 7%. This decline in the labour force participation of older people was likely related to a combination of economic conditions and the growth of public and private pension plans.

Since the early 2000s, there has been a notable upward trend in the proportion of seniors participating in the labour force, which more than doubled from 6.1% in 2001 to 13.7% in 2016.

As the baby-boom cohort continues to age, the recent trend towards a higher proportion of seniors participating in the labour market can be expected to continue. Indeed, demographic projections of Canada's labour force show that by the year 2026, 40% of the total labour force could be aged 55 and older.

Sources: A. Fields, S. Uppal, and S. LaRochelle-Côté. 2017. "The impact of aging on labour market participation rates." Insights on Canadian Society (75-006-X); tables D107-122 and D205-222 in Historical Statistics of Canada (11-516-X); and CANSIM table 282-0002.

Note to readers

Impact of the forest fires in British Columbia on the Labour Force Survey collection and estimates

As a result of forest fires, Labour Force Survey (LFS) data were not collected in a small number of communities in British Columbia in July. Using standard statistical techniques, missing data for these cases were replaced by substituted values taken from similar respondents from surrounding areas.

The population of the areas affected by forest fires represents a very small proportion of the population of British Columbia. Therefore, the impact of not collecting labour force data is minimal on provincial estimates, and negligible on national estimates.

However, the impact is likely larger for smaller sub-provincial areas, specifically for the economic region of Cariboo, where approximately 60% of collection was affected. Estimates for economic regions are presented in the form of three-month moving averages, so any impact of not collecting labour force data will be minimized.

The LFS estimates for July are for the week of July 9 to 15.

The LFS estimates are based on a sample and are therefore subject to sampling variability. As a result, monthly estimates will show more variability than trends observed over longer time periods. For more information, see "Interpreting Monthly Changes in Employment from the Labour Force Survey." Estimates for smaller geographic areas or industries also have more variability. For an explanation of the sampling variability of estimates and how to use standard errors to assess this variability, consult the "Data quality" section of the publication Labour Force Information (71-001-X).

This analysis focuses on differences between estimates that are statistically significant at the 68% confidence level.

The LFS estimates are the first in a series of labour market indicators released by Statistics Canada, which includes indicators from programs such as the Survey of Employment, Payrolls and Hours (SEPH), Employment Insurance Statistics, and the Job Vacancy and Wage Survey. For more information on the conceptual differences between employment measures from the LFS and SEPH, refer to section 8 of the Guide to the Labour Force Survey (71-543-G).

The employment rate is the number of employed people as a percentage of the population aged 15 and older. The rate for a particular group (for example, youths aged 15 to 24) is the number employed in that group as a percentage of the population for that group.

The unemployment rate is the number of unemployed people as a percentage of the labour force (employed and unemployed).

The participation rate is the number of employed and unemployed people as a percentage of the population.

Full-time employment consists of persons who usually work 30 hours or more per week at their main or only job.

Part-time employment consists of persons who usually work less than 30 hours per week at their main or only job.

Seasonal adjustment

Unless otherwise stated, this release presents seasonally adjusted estimates, which facilitate comparisons by removing the effects of seasonal variations. For more information on seasonal adjustment, see Seasonally adjusted data – Frequently asked questions.

Chart 1 shows trend-cycle data on employment. These data represent a smoothed version of the seasonally adjusted time series, which provides information on longer-term movements, including changes in direction underlying the series. These data are available in CANSIM table 282-0087 for the national level employment series. For more information, see the StatCan Blog and Trend-cycle estimates – Frequently asked questions.

Next release

The next release of the LFS will be on September 8.

Products

A more detailed summary, Labour Force Information (71-001-X), is now available for the week ending July 15.

More information about the concepts and use of the Labour Force Survey is available in an updated issue of the Guide to the Labour Force Survey (71-543-G).

The updated Labour Market Indicators dashboard (71-607-X) is now available. This new, interactive dashboard provides easy, customizable access to key labour market indicators. Users can now configure an interactive map and chart showing labour force characteristics at the national, provincial or census metropolitan area level.

Contact information

For more information, contact us (toll-free 1-800-263-1136; 514-283-8300; STATCAN.infostats-infostats.STATCAN@canada.ca).

To enquire about the concepts, methods or data quality of this release, contact Andrew Fields (613-951-3551; andrew.fields@canada.ca), Emmanuelle Bourbeau (613-951-3007(emmanuelle.bourbeau@canada.ca) or Client Services (toll-free 1-866-873-8788; statcan.labour-travail.statcan@canada.ca), Labour Statistics Division.

- Date modified: