Publications

Healthy people, healthy places

+Demographic change

+Health status

+Health behaviours

+Environment

Perceived mental health

Archived Content

Information identified as archived is provided for reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It is not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards and has not been altered or updated since it was archived. Please "contact us" to request a format other than those available.

Respondents were asked to rate their mental health as poor, fair, good, very good or excellent.

Perceived mental health is a general indication of the number of people in the population suffering from some form of mental disorder, mental or emotional problems or distress, not necessarily reflected in self-perceived health.

Importance of Indicator

The World Health Organization defines mental health as "a state of well-being in which the individual realizes his or her own abilities, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully, and is able to make a contribution to his or her community"1.

Perceived mental health is a subjective measure of overall mental health status.

Although perceived mental health does not directly correspond with measured (or diagnosed) mental disorders2,3, perceptions are important in their own right and may affect service use.

Background

Recent research has demonstrated associations between perceived mental health and social class4 , family support and family cultural conflict5 , community belonging6, service use7,8,9,10,11 , continuation of antidepressant therapy12 and activity restriction and social role functioning3.

Persistent socio-economic disadvantages such as low levels of education and income and poor housing are recognized risks to mental health1.

Highlights and graphs

Time trend

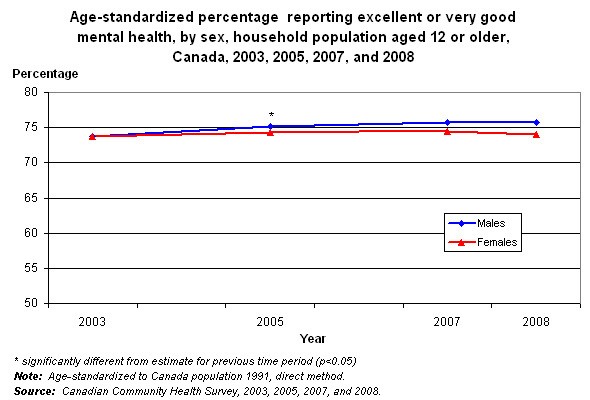

- From 2003 to 2008, the age-standardized percentage of Canadians reporting their mental health as very good or excellent was consistently high.

- In 2003, the difference between the percentages of males and females reporting very good or excellent perceived mental health was not significant. By 2007 and 2008, males were significantly more likely than females to report very good or excellent mental health.

Note: Age–standardized, direct method to 1991 Canada population.

Age group and sex

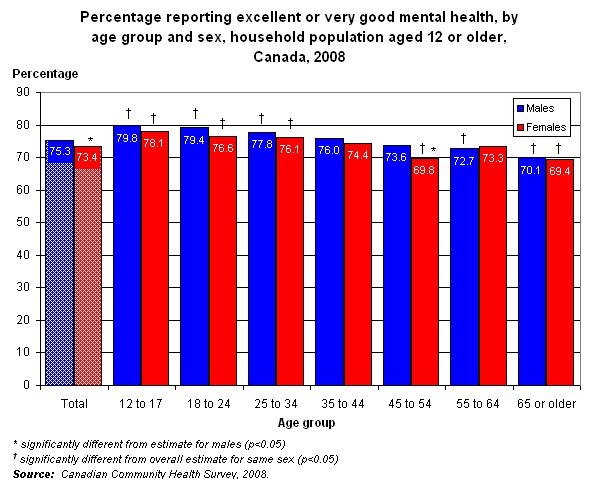

- Around three-quarters of males and females aged 12 or older perceived their mental health as very good or excellent in 2008.

- At ages 45 to 54, males were more likely than females to report very good or excellent mental health (73.6% vs. 69.8%). At all other ages, estimates for males and females did not differ.

- Younger Canadians—those aged 12 to 34—were more likely than Canadians overall to report excellent or very good perceived mental health; seniors were less likely to do so.

Province

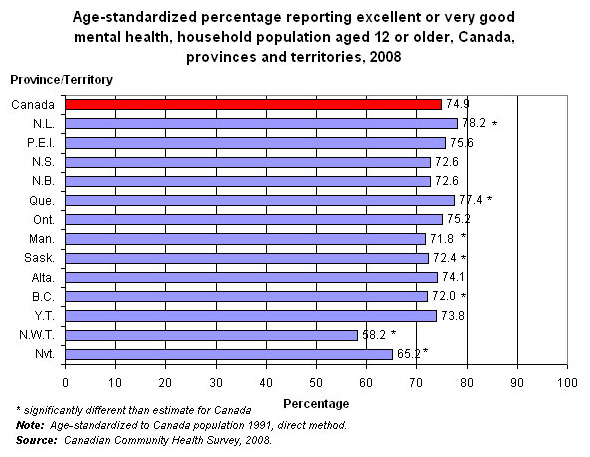

- In 2008, lower age-standardized percentages of people in Manitoba, Saskatchewan, British Columbia, Northwest Territories and Nunavut reported very good or excellent mental health, compared with Canadians overall.

- Residents of Newfoundland and Labrador and Quebec were more likely than Canadians overall to report excellent or very good mental health.

Note: Age–standardized, direct method to 1991 Canada population.

References

1. World Health Organization. Mental health: strengthening mental health promotion (Fact sheet No. 220). Geneva: World Health Organization, 2007.

2. Mawani F, Gilmour H. Validation study of self-rated mental health. Health Reports 2010 (in press).

3. Fleishman JA, Zuvekas SH. Global self-rated mental health: associations with other mental health measures and with role functioning. Medical Care 2007;45(7):602-609.

4. Honjo K, Kawakami N, Takeshima T et al. Social class inequalities in self-rated health and their gender and age group differences in Japan Journal of Epidemiology 2006;16:223-232.

5. Mulvaney-Day NE, Alegria M, Sribney W. Social cohesion, social support, and health among Latinos in the United States 2007 Social Science and Medicine 2007;64:477-495.

6. Shields M. Community belonging and self-perceived health. Health Reports (Statistics Canada, Catalogue 82-003) 2008;19(2): 51-60.

7. Katz SJ, Kessler RC, Frank RG, et al. The use of outpatient mental health services in the United States and Ontario : the impact of mental morbidity and perceived need for care. American Journal of Public Health 1997;87(7):1136-1143.

9. Albizu-Garcia CE, Alegria M, Freeman D, Vera M. Gender and health service use for a mental health problem. Social Science and Medicine 2001;53 :865-878

10. Ng TP, Jin AZ, Ho R, et al. Health beliefs and help seeking for depressive and anxiety disorders among urban Singaporean adults. Psychiatric Services 2008;59(1):105-108.

11. Zuvekas SH, Fleishman JA. Self-rated mental health and racial/ethnic disparities in mental health service use. Medical Care 2008;46(9):915-923.

12. Olfson M, Marcus SC, Tedeschi M, Wan GJ . Continuity of antidepressant treatment for adults with depression in the United States . American Journal of Psychiatry 2006;163:101-108.

- Date modified: