Firearms and violent crime in Canada, 2022

by Samuel Perreault

Highlights

- Police services in Canada reported around 14,000 incidents of firearm-related violent crime in 2022, roughly 1,400 more than the previous year.

- In 2022, the rate of firearm-related violent crime was 36.7 incidents per 100,000 population, an 8.9% increase from 2021 (33.7 incidents per 100,000 population). This is the highest rate recorded since comparable data were first collected in 2009.

- The increase in the rate of firearm-related violent crime from 2021 is mainly attributable to fairly significant increases in Ontario (1,016 more incidents, a rate increase of 24%), New Brunswick (64 more incidents, a rate increase of 24%) and British Columbia (194 more incidents, a rate increase of 12%).

- In Toronto, Canada’s largest census metropolitan area (CMA), the proportion of violent crimes that were firearm-related (4.7%) was the second-highest among CMAs. Its rate of firearm-related violent crime (43.2 incidents per 100,000 population) rose 36% from 2021 and 93% since a low in 2013.

- Canada’s other two largest CMAs also saw their rate of firearm-related violent crime increase in 2022. In Montréal, the rate (28.0 incidents per 100,000 population) increased slightly (+0.4%) from 2021, following a 12% increase from 2020 to 2021. In Vancouver, the rate (23.6 incidents per 100,000 population) increased 24% from 2021.

- From 2009 to 2013, the rate of firearm-related violent crime in Canada saw a relatively significant drop of 30% (33.9 incidents to 23.7 incidents per 100,000 population). Since then, the rate has been rising again.

- Both the violent crime rate and the rate of firearm-related violent crime have increased since 2013, but the increase in firearm-related violent crimes was larger (+55% compared with +24%). The rate of firearm-related violent crime increased because violent crime in general is on the rise, but also because violent crimes are increasingly likely to involve firearms (2.8% of violent crimes in 2022 compared with 2.2% in 2013).

- The increase in the rate of firearm-related violent crime can be seen for almost all violent offences. Over the last few years, robbery has been one of the few crimes for which the rate was declining, whether a firearm was involved or not. However, the rate of robbery involving a firearm saw an increase in 2022 (from 7.9 incidents per 100,000 population in 2021 to 9.8 in 2022).

- The rate of firearm-related violent crime was largely driven upward by violent offences specific to firearms—discharging a firearm with intent, using a firearm in the commission of an offence, pointing a firearm—for which the rate has more than doubled since 2013 to reach 12.2 incidents per 100,000 population in 2022.

- All provinces and territories have seen the rate of firearm-related violent crime increase since the low in 2013. The largest increases were recorded in the Northwest Territories (+303%), Saskatchewan (+165%), Yukon (+149%) and New Brunswick (+126%).

- Among the provinces, Saskatchewan (109.6 incidents per 100,000 population) had the highest rate of firearm-related violent crime in 2022, while Prince Edward Island recorded the lowest rate (10.0 incidents per 100,000 population).

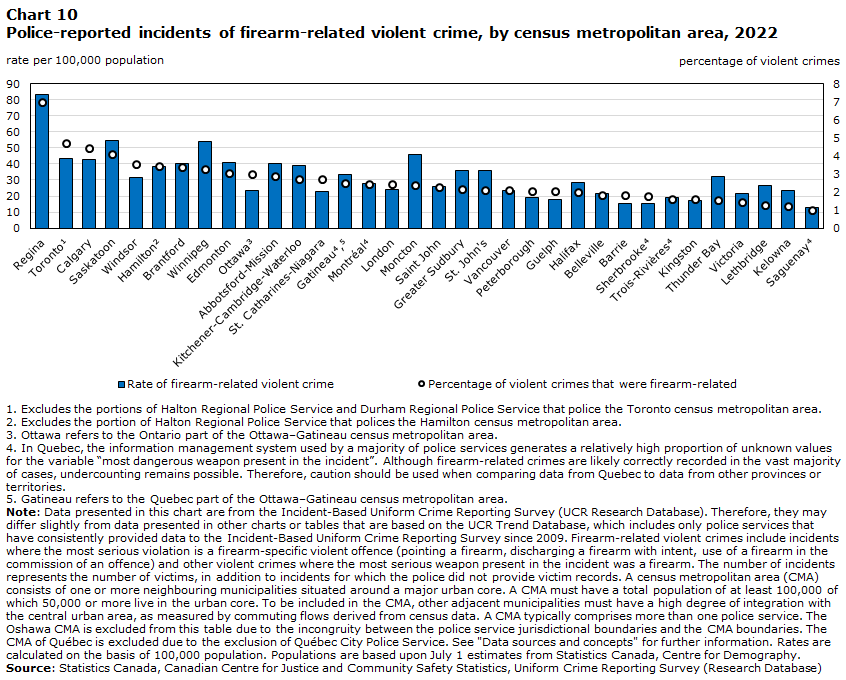

- In 2022, Regina (83.0 incidents per 100,000 population, representing 7.0% of violent crimes) recorded the highest rate and percentage of firearm-related violent crime among CMAs.

- The increase in firearm-related violent crime from 2013 to 2022 was especially large in the territories (+139%) and in rural areas of the Provincial North (+141%). In urban areas in the Provincial South, the rate rose 45% during this period.

- The increase in the rate of firearm-related violent crime can be seen for all types of firearms. However, crimes involving handguns (+50%) and firearms in the “firearm-like weapons or unknown types of firearms” category (+76%) have increased the most since 2013.

- In 2022, 1.7% of victims of violent crimes who sustained injuries were injured by a firearm. However, this proportion varies according to the level of injury: a firearm was involved in 1.0% of minor injuries, 8.6% of major injuries and 40% of fatal injuries.

- Unlike violent crimes in general, in which the majority (53%) of victims were women, firearm-related violent crimes mostly targeted men in 2022 (66%). Men also accounted for approximately 8 in 10 victims injured by firearms.

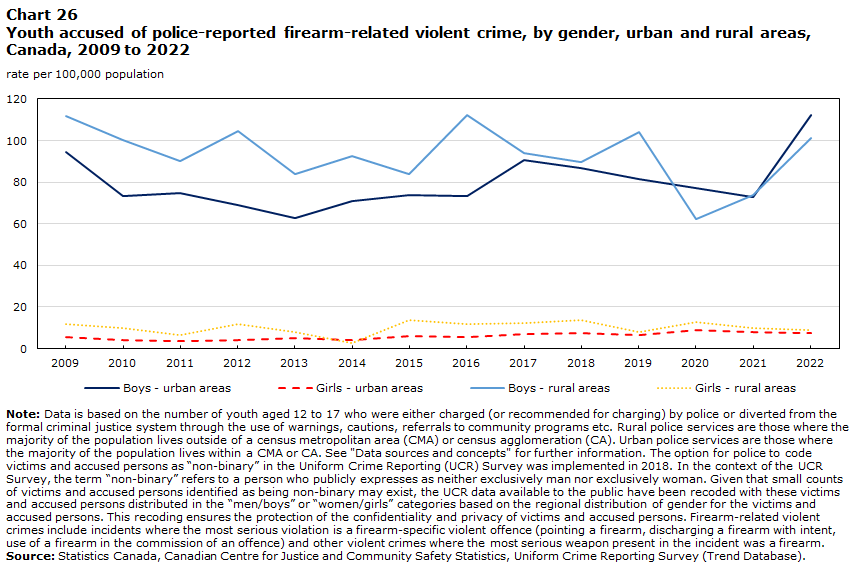

- Like for violent crimes in general, most persons accused of firearm-related violent crimes in 2022 (89%) were men. However, the rate of accused women rose faster over the last ten years (+88% compared with +26% among men).

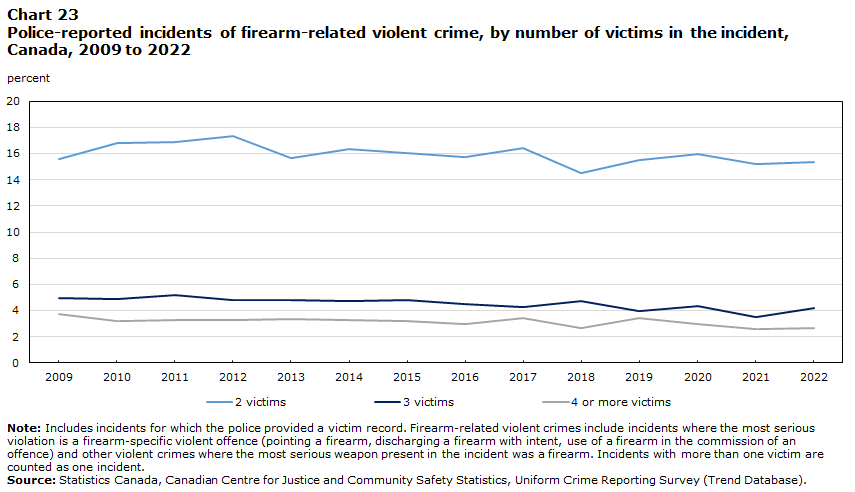

- Compared with violent crimes in general, firearm-related violent crimes were more likely to have been committed by more than one accused person (25% compared with 6.0%) or to have resulted in more than one victim (22% compared with 10%).

- In 2022, organized crime or gang-related crime accounted for 4.3% of firearm-related violent crime. This proportion is higher than for violent crimes in general (0.3%). In addition, 9.4% of firearm-related violent crimes resulting in major injuries and nearly half of those resulting in the death of the victim were organized crime-related.

- The rate of firearm-related homicide stood at 0.88 incidents per 100,000 population in 2022, the highest rate observed since 1991. Since 2016, firearms have been the main method for committing homicide, overtaking knives and other sharp objects. This increase is mostly due to homicides involving handguns.

Firearm-related violent crime represents a small proportion of crimes in Canada, among both police-reported crime and crimes reported by Canadians in victimization surveys. However, firearm-related violent crimes represent a larger share of the most serious crimes—such as homicide, attempted murder, robbery and aggravated assault—and gang-related crime.

Firearm-related violent crime can have major detrimental impacts on the affected persons and communities. These of course include the physical injuries, often more serious or lethal compared to crimes committed with other types of weapons. Exposure to firearm-related violence is also known to impact mental health (Holloway et al., 2023; Turner et al., 2019). These physical injuries and the impacts on mental health can result in significant costs for the healthcare system. In addition, firearm-related crime can adversely affect the perception of crime and safety, particularly because of the extensive media coverage that these incidents sometimes receive. Further, it has been established that an increase in or high level of firearm-related crime can have a negative impact on a community’s economy and well-being (Glasser et al., 2022; Irvin-Erickson et al., 2017).

As a result, firearm-related violent crime remains a major concern in terms of public safety and justice, and the challenges associated with gun control regularly fuel public debate. Over the past few years, various legislative changes, funding mechanisms, and programs aimed at reducing and preventing this type of crime have been proposed or implemented (Public Safety Canada, 2021, December 2; Public Safety Canada, 2023, November 3).

Using data from the Uniform Crime Reporting Survey and the Homicide Survey, this Juristat article examines the latest trends in firearm-related violent crime, as well as certain characteristics of these incidents, the victims and the accused persons.

This article was produced with funding from Public Safety Canada.

The rate of firearm-related violent crime reaches a 14-year high

In 2022, police services in Canada reported nearly 14,000 firearm-related violent crimesNote (see definition in Text box 1), representing 2.8% of all violent crimes reported by the police that year (Table 1).

The rate of firearm-related violent crime was 36.7 incidents per 100,000 population in 2022. This is an 8.9% increase from the previous year, when the rate was 33.7 incidents per 100,000 population. Moreover, firearm-related violent crime increased more quickly than other types of violent crimes. From 2021 to 2022, the firearm-related violent crime rate rose 8.9%, while the increase was 2.7% for all violent crimes combined (Chart 1).

Chart 1 start

Data table for Chart 1

| Year | Incidents of firearm-related violent crime | Victims of firearm-related violent crime | Total violent crime incidents |

|---|---|---|---|

| rate per 100,000 population | |||

| 2009 | 33.9 | 29.4 | 1,300.8 |

| 2010 | 29.3 | 25.3 | 1,267.7 |

| 2011 | 28.4 | 24.6 | 1,217.0 |

| 2012 | 27.2 | 23.1 | 1,174.4 |

| 2013 | 23.7 | 20.4 | 1,075.1 |

| 2014 | 25.0 | 21.5 | 1,025.8 |

| 2015 | 28.6 | 24.4 | 1,048.8 |

| 2016 | 28.8 | 24.5 | 1,046.6 |

| 2017 | 30.5 | 26.0 | 1,079.5 |

| 2018 | 30.2 | 25.3 | 1,116.6 |

| 2019 | 32.5 | 26.5 | 1,244.7 |

| 2020 | 34.1 | 27.4 | 1,231.5 |

| 2021 | 33.7 | 26.9 | 1,297.4 |

| 2022 | 36.7 | 29.2 | 1,332.2 |

|

Note: Firearm-related violent crimes include incidents where the most serious violation is a firearm-specific violent offence (pointing a firearm, discharging a firearm with intent, use of a firearm in the commission of an offence) and other violent crimes where the most serious weapon present in the incident was a firearm. The number of incidents represents the number of victims, in addition to incidents for which the police did not provide victim records. Rates are calculated on the basis of 100,000 population. Populations are based upon July 1 estimates from Statistics Canada, Centre for Demography. Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics, Uniform Crime Reporting Survey (Trend Database). |

|||

Chart 1 end

Since comparable data became available in 2009, the rate of firearm-related violent crime reached a low in 2013 (23.7 incidents per 100,000 population), after which a general upward trend began. The year 2021 saw a certain lull, with the rate having dropped slightly from 2020 before rising again in 2022. In fact, the rate of firearm-related violent crime in 2022 was 55% higher than the low in 2013.

Generally speaking, the trend for all violent crime—whether or not a firearm was involved—was rather similar to the trend observed for firearm-related violent crime. The rate of violent crimes reached a low in 2014, then generally trended upward, marked by a few annual fluctuations. However, the increase in the rate of all violent crime was more modest than the increase for firearm-related violent crime, rising 30% from the low in 2014. By comparison, the rate of firearm-related violent crime has increased by 55% since the low in 2013, and by 47% since 2014.

The proportion of victims injured by a firearm is increasing

For the Incident-based Uniform Crime Reporting Survey, police services collect information on injuries suffered by victims, including on the weapon that caused the injuries. Injuries caused by a firearm are still relatively rare: 1.7% of injuries suffered by victims of violent crimes were caused by a firearm in 2022. The remaining victims were injured by physical force (74%), a knife or sharp object (6.9%), burning liquid or spray such as pepper spray (4.6%), a blunt instrument (3.7%) or another weapon (9.5%) (Chart 2). However, the proportion of victims injured by a firearm varies depending on the level of injury. For example, a firearm was used in 1.0% of cases where victims suffered minor injuries. This proportion rose to 8.6% of victims who suffered major injuries and 40% of victims who were fatally injured.

Chart 2 start

Data table for Chart 2

| Year | Firearm | Knife or sharp object | Blunt instrument | Burning liquidData table for Chart 2 Note 1 | Other weapon |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| percent | |||||

| 2009 | 1.2 | 5.4 | 3.5 | 0.0 | 10.5 |

| 2010 | 1.0 | 5.1 | 2.9 | 0.0 | 10.4 |

| 2011 | 0.9 | 5.2 | 3.0 | 0.0 | 10.6 |

| 2012 | 1.0 | 5.1 | 2.9 | 0.0 | 10.8 |

| 2013 | 1.0 | 5.6 | 2.9 | 0.2 | 10.1 |

| 2014 | 1.1 | 6.1 | 3.2 | 1.3 | 9.1 |

| 2015 | 1.3 | 6.1 | 3.3 | 2.0 | 9.1 |

| 2016 | 1.4 | 6.3 | 3.2 | 2.4 | 9.0 |

| 2017 | 1.5 | 6.6 | 3.4 | 3.0 | 8.8 |

| 2018 | 1.4 | 6.4 | 3.3 | 3.3 | 8.9 |

| 2019 | 1.5 | 6.5 | 3.3 | 3.7 | 9.0 |

| 2020 | 1.7 | 6.9 | 3.6 | 4.4 | 9.4 |

| 2021 | 1.7 | 6.7 | 3.8 | 4.6 | 9.7 |

| 2022 | 1.7 | 6.9 | 3.7 | 4.6 | 9.5 |

Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics, Uniform Crime Reporting Survey (Trend Database). |

|||||

Chart 2 end

In addition, trend analysis reveals that on the one hand, an increasingly large proportion of victims are injured after being attacked with a weapon, as opposed to being injured from, for example, a beating. On the other hand, the proportion of victims whose injuries were caused by a firearm increased more quickly than for most other types of weapons. In 2013, when the rate of firearm-related violent crime fell to a low, 1.0% of injuries suffered by victims of violent crimes had been caused by a firearm. In 2022, this proportion was 1.7%—an increase of 76%. By comparison, the proportion of victims whose injuries were caused by a knife or sharp object rose 25% during this same period. The proportions of victims whose injuries were caused by a blunt object (+27%) or by another weapon (+37%) have also increased since 2013.

Start of text box 1

Text box 1

Measuring firearm-related violent crime

For the purposes of this analysis, a firearm-related violent crime refers to a crime where a firearm was present during the commission of the offence and for which the police determined that the firearm was relevant to the crime, whether or not it was used. Crimes involving a firearm-like weapon, such as an imitation weapon or a pellet gun, are also included in the analyses. Firearm-specific offences—such as discharging a firearm with intent, pointing a firearm and using a firearm during the commission of an offence—are also counted as crimes involving firearms, including cases in which information on the weapon was unknown. Information on the presence of a firearm comes from the Incident-based Uniform Crime Reporting Survey (UCR2), which covers 99% of the Canadian population.

Various approaches can be taken to measure violent crime. First, analyses can be based on the number of victims. When many persons are victims in the same incident, a single incident is counted multiple times, once per victim record. However, for some violent offences reported in the UCR2 survey, information on the victims may not always be provided.Note For firearm-specific violent crimes, a victim record may be provided, but is not required. The same applies for robberies and threats. This is why another method of measuring firearm-related violent crime involves taking into account the number of incidents instead of the number of victims. With this method, each incident is counted the same way, whether or not there is any information on the victims and regardless of the number of victims.

Finally, there is a hybrid approach that involves counting incidents by the number of victims, but also includes incidents for which the police did not provide information on the victims; these incidents are counted as one incident. The annual release on police-reported crime statistics is usually based on this approach (Statistics Canada 2023, July 27).

Although various approaches can be used to measure firearm crime, it should be noted that they all produce relatively similar results. Therefore, regardless of the approach, firearm-related violent crime has been trending upward since the low in 2013.

That said, over the past few years, the increase in firearm-related violent crime was particularly significant for crimes with no information on the victims, driven by firearm-specific crimes such as discharging a firearm. Therefore, an approach that counts only victims may underestimate the increase in firearm-related violent crime. For example, since the low in 2013, the rate of victims of firearm-related violent crime has risen 43%, whereas the increase is 55% when both the victims and crimes with no victim information (hybrid approach) are counted. Counting incidents alone, regardless of the number of victims, also poses some problems. Crimes involving firearms are more likely to result in several victims; counting only incidents would therefore underestimate the incidence of gun violence compared with other types of crime. It is for this reason that this study adopts a hybrid approach, where each crime and each victim is counted. Thus, each victim record is considered a “criminal incident,” as is each incident record with no victim information; it is in this sense that the term “incident” or “crime” is used in this article.

It should be noted that the most recent Juristat articles about firearm-related violent crime were based on the number of victims rather than on the number of incidents. The trends noted in this article could therefore slightly differ from what had been published in these articles.

End of text box 1

Start of text box 2

Text box 2

Reporting firearm-related violent crime to the police

In Canada, the official statistics on crime and criminal victimization mainly come from two types of data sources: data reported by the police (e.g., Incident-Based Uniform Crime Reporting Survey, Homicide Survey) and data from self-reported victimization surveys (e.g., General Social Survey [GSS] on Canadians’ Safety [Victimization], Survey of Safety in Public and Private Spaces).

The data presented in this article are based on police-reported data. Thus, they are limited to crimes known to the police. However, only a portion of crimes actually come to the attention of the police. According to data from the 2019 GSS on Canadians’ Safety, just under one-quarter (24%) of violent crimes were reported to the police. This proportion was two times higher when victims were men (36%) than when victims were women (18%), a difference largely attributable to the small proportion of sexual assaults that are reported to the police (Cotter, 2021).

The sample size, combined with the relatively low frequency of firearm-related crime, does not allow for the calculation of the reporting rate for firearm-related crime to the police. However, data from the GSS indicate that violent crime in which a weapon—a firearm, knife, stick or bat, or another weapon—was present was reported in more than half (51%) of the cases.

Firearm-related crime represented 2.2% of violent crimes reported through the 2019 GSS. This proportion is slightly lower than the proportion among police-reported crimes in 2022 (2.8%). This may reflect the fact that firearm-related crime is more likely to be reported to the police than crimes where no weapon was present.

End of text box 2

First increase in five years in robberies involving firearms

Since 2013, most offences have seen a significant increase in the rate of firearm-related incidents. However, robberies, which represented just over one-quarter of firearm-related violent crime in 2022, showed a very different trend. From 2013 to 2017, the rate fluctuated slightly upward, then began a decline that was accentuated by the COVID-19 pandemic (for more details on impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on crime, see Moreau 2022). However, in 2022, the rate of robberies involving firearms started to rise again, increasing 24% from 2021 (Chart 3). It is possible that the increase in the rate of robberies involving firearms reflects a certain return to normal activities after the drop recorded during the first years of the COVID-19 pandemic. That said, from 2021 to 2022, the increase in firearm-related robberies (+24%) was larger than the increase in robberies not involving firearms (+14%).

Chart 3 start

Data table for Chart 3

| Year | Homicides and other violations causing death, attempted murder | Robbery | Sexual assaults | Assaults | Firearm-specific violent offences (pointing, discharging, using) | Threats, extortion and intimidation | Other violent crimes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rate per 100,000 population | |||||||

| 2009 | 1.73 | 15.48 | 0.25 | 6.90 | 5.23 | 2.68 | 1.62 |

| 2010 | 1.40 | 12.63 | 0.18 | 5.90 | 5.60 | 2.53 | 1.11 |

| 2011 | 1.27 | 12.45 | 0.15 | 5.92 | 5.50 | 2.18 | 0.95 |

| 2012 | 1.48 | 11.11 | 0.18 | 5.53 | 5.93 | 2.13 | 0.86 |

| 2013 | 1.22 | 9.33 | 0.20 | 4.78 | 5.56 | 1.92 | 0.73 |

| 2014 | 1.25 | 10.12 | 0.14 | 4.88 | 5.37 | 2.42 | 0.83 |

| 2015 | 1.58 | 11.78 | 0.23 | 5.06 | 6.57 | 2.46 | 0.90 |

| 2016 | 1.65 | 11.01 | 0.16 | 5.57 | 7.07 | 2.59 | 0.75 |

| 2017 | 1.77 | 11.81 | 0.22 | 5.51 | 7.64 | 2.73 | 0.87 |

| 2018 | 1.79 | 11.51 | 0.30 | 5.39 | 7.46 | 2.95 | 0.81 |

| 2019 | 1.90 | 10.92 | 0.25 | 5.93 | 9.42 | 3.24 | 0.79 |

| 2020 | 2.05 | 9.17 | 0.27 | 7.12 | 10.94 | 3.61 | 0.90 |

| 2021 | 1.89 | 7.94 | 0.39 | 7.33 | 11.63 | 3.52 | 1.03 |

| 2022 | 2.00 | 9.84 | 0.32 | 7.65 | 12.23 | 3.71 | 0.97 |

|

Note: Firearm-related violent crimes include incidents where the most serious violation is a firearm-specific violent offence (pointing a firearm, discharging a firearm with intent, use of a firearm in the commission of an offence) and other violent crimes where the most serious weapon present in the incident was a firearm. The number of incidents represents the number of victims, in addition to incidents for which the police did not provide victim records. Rates are calculated on the basis of 100,000 population. Populations are based upon July 1 estimates from Statistics Canada, Centre for Demography. Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics, Uniform Crime Reporting Survey (Trend Database). |

|||||||

Chart 3 end

Increases in the rate of crime involving weapons were also noted for most of the other offences. From 2021 to 2022, the rate of firearm-related homicide, other violent crimes causing death, and attempted murder and was up 5.8% overall. The rate of threats, extortion and intimidation rose 5.3%, while the firearm-specific crime rate increased 5.2% (Table 2). In contrast, the rate of sexual assault involving a firearm fell 18%. However, the 2021 rate of police-reported sexual assault involving a firearm was the highest on record since 2009.

As an offence category, firearm-specific crime increased the most in recent years

Among violent crime involving firearms, firearm-specific crime is the category that has increased the most in recent years. Since the low in firearm crime in 2013, the rate of these crimes has more than doubled (+120%) (Chart 3). Firearm-specific crimes involving a handgun increased the most. Their number has more than tripled since 2013, and more than quadrupled since 2009. The number of firearm-specific offences involving other types of firearms has doubled since 2009.

In comparison, the rate of threats, extortion or intimidation involving firearms climbed 93% during the same period. The rate of firearm-related homicides, other violent crimes causing death, and attempted murder, as well as the rate of sexual assault involving a firearm, has risen 64% since 2013 (Chart 3).

The rate of firearm discharge offences is almost 10 times higher than in 2002

Over a 20-year period,Note the rate of incidents of discharging a firearm with intent has shown a strong upward trend. In 2022, the rate for these offences was almost 10 times higher than it was in 2002 (5.5 per 100,000 population in 2022 compared with 0.6 in 2002) (Chart 4).

Chart 4 start

Data table for Chart 4

| Year | Discharging a firearm with intent | Use of a firearm in the commission of an offence | Pointing a firearm |

|---|---|---|---|

| rate per 100,000 population | |||

| 2002 | 0.57 | 0.76 | 5.55 |

| 2003 | 0.69 | 1.02 | 5.56 |

| 2004 | 0.71 | 1.24 | 4.96 |

| 2005 | 0.81 | 1.09 | 4.27 |

| 2006 | 0.77 | 1.16 | 2.76 |

| 2007 | 0.94 | 1.51 | 2.54 |

| 2008 | 1.26 | 1.02 | 2.17 |

| 2009 | 1.58 | 1.16 | 2.42 |

| 2010 | 1.82 | 1.22 | 2.89 |

| 2011 | 1.66 | 1.22 | 2.78 |

| 2012 | 1.85 | 1.24 | 2.83 |

| 2013 | 1.58 | 1.13 | 2.68 |

| 2014 | 1.92 | 1.11 | 2.23 |

| 2015 | 2.58 | 1.17 | 2.86 |

| 2016 | 3.07 | 1.22 | 2.74 |

| 2017 | 3.16 | 1.42 | 2.99 |

| 2018 | 3.11 | 1.34 | 3.28 |

| 2019 | 4.02 | 1.57 | 3.84 |

| 2020 | 4.93 | 1.64 | 4.45 |

| 2021 | 5.38 | 1.77 | 4.52 |

| 2022 | 5.45 | 1.86 | 4.87 |

|

Note: Data are based on the most serious violation in the incident. Rates are calculated on the basis of 100,000 population. Populations are based upon July 1 estimates from Statistics Canada, Centre for Demography. Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics, Uniform Crime Reporting Survey. |

|||

Chart 4 end

The increase in firearm discharge incidents is largely responsible for the increase in the rate for all firearm-specific violent offences. The rate of incidents related to using a firearm during the commission of an offence also increased significantly (+145%) during this period, but to a lesser extent than firearm discharge incidents (+861 %). Conversely, the rate of incidents related to pointing a firearm (4.9 incidents per 100,000 population) was lower in 2022 than in 2002 (5.6). However, the rate for these incidents declined rapidly until 2008, then fluctuated until it resumed an upward trend starting in 2014 (Chart 4).

Start of text box 3

Text box 3

Gun control in Canada

According to the Criminal Code, firearms are classified into three categories: prohibited firearms, restricted firearms and non-restricted firearms. Prohibited firearms include fully automatic firearms, sawed-off rifles and shotguns, and any other firearm prescribed as prohibited under the regulations, such as certain types of handguns. Handguns not falling into the prohibited category are classified as restricted weapons, while rifles and shotguns, also called long guns, are usually included in the non-restricted firearms category.

Canadian law requires anyone who wants to own a firearm or purchase ammunition to hold a valid firearms licence under the Firearms Act (1995). Over the years, various amendments were made to the Criminal Code and the Firearms Act. In 2012, Bill C-19 (An Act to amend the Criminal Code and the Firearms Act) abolished the requirement to register non-restricted firearms. Subsequent amendments simplified the firearms licensing regime for individuals, limited the discretionary authority of chief firearms officers, and permitted information-sharing about commercial importations of firearm (Bill C-42; 2015) and imposed certain conditions with respect to the transfer of non-restricted firearms, removed some automatic authorizations to transport prohibited and restricted firearms, and grandfathered certain individuals and firearms previously prescribed as restricted or non-restricted (Bill C-71; 2019).

More recently, through Orders in Council, the government amended the classification of some firearms, strengthening licence verification for the transfer of non-restricted firearms and restricting the transfer and carrying of handguns (also called the “handgun freeze”). Further measures are proposed in Bill C-21, An Act to amend certain Acts and to make certain consequential amendments (firearms). This bill, which was passed by the House of Commons and was being reviewed by the Senate at the time of this article's writing, would establish new circumstances under which a prohibition order or a search or seizure warrant can be issued, or a licence suspended. It would also create new offences (e.g., altering a magazine) and increase the maximum penalties for certain firearm offences. If made law, Bill C-21 would terminate, with some exceptions, the issuing of registration certificates for handguns to individuals; without a registration certificate, an individual cannot legally own a handgun.

End of text box 3

Ontario sees the largest increase in firearm-related violent crime between 2021 and 2022

Among the provinces and territories, the rate of violent crime involving firearms increased the most in Ontario compared with 2021. It rose from 25.8 to 32.1 incidents per 100,000 population, a 24% increase. In 2022, 3.3% of police-reported violent crime in Ontario involved firearms. New Brunswick had the second-largest increase, with the rate rising from 32.8 to 40.6 incidents per 100,000 population (Table 1).

However, the Northwest Territories (230.2 incidents per 100,000 population) recorded the highest rate of firearm-related violent crime. The high rate of firearm-related violent crime in the Northwest Territories is the result of the high number of violent crimes in this territory in general. In fact, its proportion of firearm-related violent crime (1.9%) was lower than that recorded across the country (2.8%). Moreover, the situation is similar in the other two territories, where the rate of violent crime involving firearms was relatively high despite having a relatively low proportion (1.5%) of violent crimes there that involved firearms (Table 1).

Despite relatively notable decreases, Nunavut (182.6) and Saskatchewan (109.6) were also among the provinces and territories with the highest rates of firearm-related violent crime. Prince Edward Island (10.0) and Newfoundland and Labrador (22.8) recorded the lowest rates.

Since 2009, the trend in gun violence has varied across the provinces and territories. In the Atlantic provinces in particular, each province posted a very different trend. Newfoundland and Labrador saw an increase in firearm-related violent crime between 2009 and 2015. Since then, the rate has been relatively stable. In Prince Edward Island, despite some significant annual fluctuations inherent to the small size of the population, the rate has remained relatively stable around an annual average of 12.8 firearm-related violent crimes. In the other two Atlantic provinces, the rate of firearm-related violent crime reached a low in 2014 in New Brunswick and in 2016 in Nova Scotia, before resuming an upward trend. In Nova Scotia, however, the rate has dropped since 2020, when the province saw the deadliest shooting in the country’s history (22 killed in the Portapique area) (Chart 5).

Chart 5 start

Data table for Chart 5

| Year | Newfoundland and Labrador | Prince Edward Island | Nova Scotia | New BrunswickData table for Chart 5 Note 1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| rate per 100,000 population | ||||

| 2009 | 15.7 | 17.9 | 35.0 | 20.0 |

| 2010 | 16.9 | 7.8 | 26.2 | 19.8 |

| 2011 | 14.9 | 16.0 | 33.6 | 22.3 |

| 2012 | 21.8 | 13.1 | 33.5 | 27.5 |

| 2013 | 19.0 | 5.6 | 24.1 | 18.0 |

| 2014 | 18.0 | 11.1 | 25.2 | 16.8 |

| 2015 | 25.4 | 15.9 | 19.3 | 17.7 |

| 2016 | 24.2 | 12.2 | 17.4 | 26.8 |

| 2017 | 21.6 | 17.3 | 24.5 | 26.4 |

| 2018 | 24.7 | 16.3 | 21.1 | 27.1 |

| 2019 | 22.2 | 12.1 | 23.4 | 32.6 |

| 2020 | 20.7 | 15.5 | 31.6 | 33.4 |

| 2021 | 25.0 | 9.1 | 29.6 | 32.8 |

| 2022 | 22.8 | 10.0 | 28.7 | 40.6 |

Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics, Uniform Crime Reporting Survey (Trend Database). |

||||

Chart 5 end

In Quebec,Note the rate of firearm-related violent crime decreased from 2011 to 2016, then remained stable through 2019. Since then, an upward trend has seemed to emerge, despite a very slight decline from 2021 to 2022. In Ontario, the rate decreased sharply from 2009 to 2013, before beginning an upward trend. In 2021, the rate decreased from the previous year for the first time since 2013. However, this was followed by the largest year-to-year increase to date, with a 24% increase from 2021 to 2022. In British Columbia, the trend was relatively similar to that of Quebec: the rate fell to a low in 2018 before resuming an upward trend (Chart 6).

Chart 6 start

Data table for Chart 6

| Year | QuebecData table for Chart 6 Note 1 | Ontario | British Columbia |

|---|---|---|---|

| rate per 100,000 population | |||

| 2009 | 31.9 | 32.7 | 33.9 |

| 2010 | 32.9 | 23.1 | 30.6 |

| 2011 | 34.7 | 21.4 | 25.5 |

| 2012 | 28.0 | 21.0 | 29.3 |

| 2013 | 24.7 | 18.2 | 24.0 |

| 2014 | 24.1 | 20.2 | 23.9 |

| 2015 | 23.0 | 22.2 | 29.5 |

| 2016 | 19.7 | 25.5 | 23.6 |

| 2017 | 20.5 | 28.1 | 22.5 |

| 2018 | 20.6 | 28.7 | 19.6 |

| 2019 | 19.5 | 29.1 | 25.8 |

| 2020 | 22.2 | 29.4 | 26.8 |

| 2021 | 25.1 | 25.8 | 24.9 |

| 2022 | 24.8 | 32.1 | 28.0 |

Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics, Uniform Crime Reporting Survey (Trend Database). |

|||

Chart 6 end

In each of the Prairie provinces, the rate fell to a low around 2013 or 2014 before beginning an upward trend. However, the extent of this increase was not the same everywhere. For example, Alberta (+71%) had a relatively significant increase since the low in 2013, but this increase was much smaller than in Saskatchewan, where the rate rose by 165% over the same period. In Manitoba, the rate of firearm-related violent crime has also seen a significant increase (+103%) since falling to a low in 2014 (Chart 7).

Chart 7 start

Data table for Chart 7

| Year | Manitoba | Saskatchewan | Alberta |

|---|---|---|---|

| rate per 100,000 population | |||

| 2009 | 49.9 | 42.3 | 38.7 |

| 2010 | 45.1 | 44.8 | 36.7 |

| 2011 | 43.3 | 44.2 | 35.0 |

| 2012 | 38.2 | 46.0 | 33.2 |

| 2013 | 38.2 | 41.4 | 31.9 |

| 2014 | 34.7 | 48.8 | 35.6 |

| 2015 | 43.8 | 61.1 | 47.9 |

| 2016 | 55.7 | 74.9 | 44.0 |

| 2017 | 56.2 | 93.9 | 42.7 |

| 2018 | 60.1 | 83.0 | 43.0 |

| 2019 | 69.7 | 99.8 | 46.3 |

| 2020 | 60.2 | 106.2 | 51.8 |

| 2021 | 70.4 | 117.9 | 51.5 |

| 2022 | 70.5 | 109.6 | 54.5 |

|

Note: Firearm-related violent crimes include incidents where the most serious violation is a firearm-specific violent offence (pointing a firearm, discharging a firearm with intent, use of a firearm in the commission of an offence) and other violent crimes where the most serious weapon present in the incident was a firearm. The number of incidents represents the number of victims, in addition to incidents for which the police did not provide victim records. Rates are calculated on the basis of 100,000 population. Populations are based upon July 1 estimates from Statistics Canada, Centre for Demography. Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics, Uniform Crime Reporting Survey (Trend Database). |

|||

Chart 7 end

In the territories, given the low number of firearm-related violent crimes and the small population size, significant annual fluctuations are observed. Nevertheless, each of the territories recorded a low sometime in the mid-2010s before an overall upward trend began. This increase was particularly strong in the Northwest Territories, where the rate has more than quintupled since the low in 2014 (Chart 8).

Chart 8 start

Data table for Chart 8

| Year | Yukon | Northwest Territories | Nunavut |

|---|---|---|---|

| rate per 100,000 population | |||

| 2009 | 38.5 | 44.0 | 162.6 |

| 2010 | 80.9 | 64.7 | 140.9 |

| 2011 | 39.5 | 87.3 | 163.8 |

| 2012 | 38.6 | 77.9 | 201.9 |

| 2013 | 30.1 | 57.1 | 121.7 |

| 2014 | 75.4 | 43.3 | 155.7 |

| 2015 | 69.0 | 76.9 | 172.7 |

| 2016 | 67.5 | 98.5 | 121.7 |

| 2017 | 55.5 | 75.7 | 197.1 |

| 2018 | 54.3 | 113.4 | 201.9 |

| 2019 | 84.6 | 159.8 | 207.3 |

| 2020 | 113.7 | 176.4 | 158.3 |

| 2021 | 71.8 | 212.7 | 236.7 |

| 2022 | 75.1 | 230.2 | 182.6 |

|

Note: Firearm-related violent crimes include incidents where the most serious violation is a firearm-specific violent offence (pointing a firearm, discharging a firearm with intent, use of a firearm in the commission of an offence) and other violent crimes where the most serious weapon present in the incident was a firearm. The number of incidents represents the number of victims, in addition to incidents for which the police did not provide victim records. Rates are calculated on the basis of 100,000 population. Populations are based upon July 1 estimates from Statistics Canada, Centre for Demography. Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics, Uniform Crime Reporting Survey (Trend Database). |

|||

Chart 8 end

Sharp increase in the rate of firearm-related violent crime in Toronto and Vancouver, rate in Montréal relatively stable after two years of increase

After declining over the previous two years, the rate of firearm-related violent crime significantly increased in two of the three largest census metropolitan areas (CMAs)Note in Canada, namely Toronto and Vancouver. In Toronto,Note − which in 2022 accounted for slightly more than half of firearm-related violent crime in Ontario, and 18% in Canada − police reported 2,576 incidents of firearm-related violent crime in 2022, 725 more than the preceding year. The rate of firearm-related violent crimes rose from 31.7 incidents per 100,000 population in 2021 to 43.2 in 2022 (+36%). Firearm-related violent crime reached its highest rate in over 10 years in 2022, thereby concluding 3 consecutive years of declines (Chart 9).

Chart 9 start

Data table for Chart 9

| Year | MontréalData table for Chart 9 Note 1 | TorontoData table for Chart 9 Note 2 | Vancouver |

|---|---|---|---|

| rate per 100,000 population | |||

| 2009 | 40.7 | 46.4 | 39.2 |

| 2010 | 42.4 | 28.2 | 36.9 |

| 2011 | 46.8 | 26.7 | 28.3 |

| 2012 | 35.0 | 25.8 | 34.8 |

| 2013 | 29.7 | 22.4 | 26.9 |

| 2014 | 28.4 | 29.1 | 26.5 |

| 2015 | 28.1 | 32.6 | 32.6 |

| 2016 | 21.8 | 38.2 | 24.5 |

| 2017 | 21.3 | 41.5 | 20.2 |

| 2018 | 21.7 | 41.8 | 19.7 |

| 2019 | 19.9 | 41.7 | 24.1 |

| 2020 | 24.8 | 39.1 | 21.6 |

| 2021 | 27.9 | 31.7 | 19.1 |

| 2022 | 28.0 | 43.2 | 23.6 |

Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics, Uniform Crime Reporting Survey (Trend Database). |

|||

Chart 9 end

In Vancouver, the rate of firearm-related violent crime in 2022 (23.6 incidents per 100,000) increased by 24% from 2021. However, the rate in 2021 (19.1) was the lowest recorded since 2009 and followed a generally downward trend. Despite this increase, the rate of firearm-related violent crime in Vancouver remained lower than that of Toronto and Montréal.

Firearm-related violent crime in Montréal, Canada’s second largest CMA, followed a relatively similar trend to Vancouver, generally decreasing during the 2010s. From 2019, the rate of firearm-related violent crime started an upward trend that was reinforced in 2022, with the rate increasing slightly (+0.4%) compared with 2021 (28.0 incidents per 100,000 population compared with 27.9).

Regina has the highest rate of firearm-related violent crime among the CMAs

In 2022, Regina was the CMA that had by far the highest rate of firearm-related violent crime (83.0 incidents per 100,000 population), with 7.0% of violent crime in this CMA involving firearms. Despite a slight drop from 2021 (-4.9%), the rate of firearm-related violent crime in Regina almost quadrupled in 10 years, from a rate of 22.4 in 2012. Only the Greater Sudbury (+298%) and Thunder Bay (+287%) CMAs had larger increases in the rate of firearm-related violent crime during this period (Table 3, Chart 10).

Chart 10 start

Data table for Chart 10

| Census metropolitan area | rate per 100,000 population | percentage of violent crimes |

|---|---|---|

| Regina | 83.0 | 7.0 |

| TorontoData table for Chart 10 Note 1 | 43.2 | 4.7 |

| Calgary | 43.0 | 4.4 |

| Saskatoon | 54.3 | 4.1 |

| Windsor | 31.6 | 3.5 |

| HamiltonData table for Chart 10 Note 2 | 38.5 | 3.4 |

| Brantford | 40.0 | 3.4 |

| Winnipeg | 54.2 | 3.3 |

| Edmonton | 40.8 | 3.1 |

| OttawaData table for Chart 10 Note 3 | 23.2 | 3.0 |

| Abbotsford-Mission | 40.5 | 2.9 |

| Kitchener-Cambridge-Waterloo | 39.3 | 2.7 |

| St. Catharines-Niagara | 22.6 | 2.7 |

| GatineauData table for Chart 10 Note 4 Data table for Chart 10 Note 5 | 33.1 | 2.5 |

| MontréalData table for Chart 10 Note 4 | 28.0 | 2.4 |

| London | 24.3 | 2.4 |

| Moncton | 45.6 | 2.4 |

| Saint John | 25.9 | 2.3 |

| Greater Sudbury | 36.2 | 2.1 |

| St. John's | 35.6 | 2.1 |

| Vancouver | 23.6 | 2.1 |

| Peterborough | 19.1 | 2.0 |

| Guelph | 18.0 | 2.0 |

| Halifax | 28.5 | 2.0 |

| Belleville | 21.4 | 1.8 |

| Barrie | 15.5 | 1.8 |

| SherbrookeData table for Chart 10 Note 4 | 15.5 | 1.8 |

| Trois-RivièresData table for Chart 10 Note 4 | 19.4 | 1.6 |

| Kingston | 17.4 | 1.6 |

| Thunder Bay | 32.1 | 1.6 |

| Victoria | 21.5 | 1.4 |

| Lethbridge | 26.6 | 1.3 |

| Kelowna | 23.5 | 1.3 |

| SaguenayData table for Chart 10 Note 4 | 12.8 | 1.0 |

Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics, Uniform Crime Reporting Survey (Research Database) |

||

Chart 10 end

Saskatoon (54.3 incidents per 100,000 population) recorded the second-highest rate of firearm-related violent crime among the CMAs in Canada, followed closely by Winnipeg (54.2). However, the Toronto CMA recorded the second-highest proportion of firearm-related violent crime: 4.7% of violent crime there involved firearms.

Compared with 2012, the most significant increases in the rate of firearm-related violent crime were recorded in Greater Sudbury (+298%), Thunder Bay (+287%) and Regina (+270%). That said, almost all CMAs saw a higher rate of firearm-related violent crime in 2022 than what was recorded 10 years earlier. Only the Halifax (-41%), Vancouver (-32%), Montréal (-20%) and Barrie (-1.1%) CMAs posted lower rates of firearm-related violent crime in 2022 than in 2012 (Table 3).

The rates of firearm-related violent crime are higher in northern rural areas, particularly in the northern Prairies

Firearm crime does not affect only metropolitan areas. Rural areas are also affected, and even more so. For all CMAs combined, the rate of firearm-related violent crime was 33.5 incidents per 100,000 population in 2022. When small or medium-sized cities (census agglomerations) were added, this rate increased slightly (33.8) (Table 3).

In rural areas of the provinces, the rate of firearm-related violent crime (50.2) in 2022 was almost 50% higher than in urban areas (33.8).Note This difference is mainly attributable to northern rural areas,Note where the rate is 148.9 incidents per 100,000 population. Several studies noted that crime rates are relatively high in the northern rural areas, and that the gap between them and areas in the south has increased in recent years (Allen & Perreault, 2015; Perreault, 2023; Perreault, 2019). The high rate of firearm-related violent crime in northern rural areas primarily stems from the relatively high overall crime rate, although the proportion of violent crime involving firearms (3.3%) is also higher than in southern (2.9%) and northern (1.8%) urban areas (Table 1).

The rate of firearm-related violent crime in 2022 was particularly high in the northern rural areas of the Prairie provinces. In northern Saskatchewan, police reported 309 violent crimes involving firearms for a total population of about 40,000. This is equivalent to a rate of 766.3 incidents per 100,000 population. However, this rate, which is higher than elsewhere in Saskatchewan, mostly reflects the fact that crime in general is relatively high in the province’s northern areas, with 4.4% of violent crime involving firearms, compared with 4.8% in southern urban areas (Table 1).

In other regions in the Prairies, the rate stood at 318.5 firearm-related violent crimes per 100,000 population in rural areas of northern Manitoba and 194.4 in rural areas of northern Alberta. The proportion of violent crime involving firearms was especially high in rural areas of northern Alberta, where 5.5% of violent crimes involved a firearm in 2022.

Chart 11 start

Data table for Chart 11

| Year | Provincial urban South | Provincial urban North | Provincial rural South | Provincial rural North | Territories |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rate per 100,000 population | |||||

| 2009 | 34.7 | 25.9 | 24.4 | 65.9 | 77.6 |

| 2010 | 29.1 | 21.1 | 24.5 | 65.7 | 92.6 |

| 2011 | 28.1 | 23.7 | 23.6 | 62.5 | 95.5 |

| 2012 | 26.0 | 25.4 | 25.4 | 67.6 | 103.0 |

| 2013 | 23.0 | 21.7 | 20.4 | 61.7 | 68.3 |

| 2014 | 24.1 | 24.9 | 22.0 | 63.7 | 88.0 |

| 2015 | 27.4 | 32.1 | 24.6 | 74.8 | 103.9 |

| 2016 | 27.6 | 23.5 | 24.7 | 89.9 | 95.7 |

| 2017 | 29.1 | 29.2 | 27.3 | 90.6 | 106.5 |

| 2018 | 29.0 | 33.7 | 24.9 | 84.2 | 121.3 |

| 2019 | 30.7 | 33.4 | 29.5 | 94.9 | 149.6 |

| 2020 | 30.6 | 39.8 | 36.7 | 116.0 | 149.9 |

| 2021 | 29.5 | 41.3 | 35.9 | 139.8 | 172.8 |

| 2022 | 33.5 | 41.1 | 33.5 | 148.9 | 163.0 |

|

Note: Rural police services are those where the majority of the population lives outside of a census metropolitan area (CMA) or census agglomeration (CA). Urban police services are those where the majority of the population lives within a CMA or CA. See "Data sources and concepts" for further information. Provincial North encompasses the northern regions of Newfoundland and Labrador, Ontario, Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta and British Columbia (North and South ― Variant of Standard Geographical Classification 2021). Firearm-related violent crimes include incidents where the most serious violation is a firearm-specific violent offence (pointing a firearm, discharging a firearm with intent, use of a firearm in the commission of an offence) and other violent crimes where the most serious weapon present in the incident was a firearm. The number of incidents represents the number of victims, in addition to incidents for which the police did not provide victim records. Rates are calculated on the basis of 100,000 population. Populations are based upon July 1 estimates from Statistics Canada, Centre for Demography. Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics, Uniform Crime Reporting Survey (Trend Database). |

|||||

Chart 11 end

Although southern urban areas have seen a certain upsurge in violent crime involving firearms overall since the low in 2013, the rate recorded in 2022 remained slightly lower than it was in 2009. The situation is quite different in rural areas and northern regions. Since 2009, the rate of firearm-related violent crime more than doubled in rural areas of the Provincial North (from 65.9 to 148.9 incidents per 100,000 population) and in the territories (from 77.6 to 163.0 incidents per 100,000 population). In northern urban areas (+59%) and rural areas in the south (+37%), the rate of firearm-related violent crime in 2022 was also higher than in 2009 (Chart 11).

Handguns involved in over half of firearm-related violent crimes

In 2022, more than half (53%) of firearm-related violent crime involved a handgun. In comparison, 15% of firearm-related violent crime involved a rifle or shotgun, 4.8% involved a fully automatic or sawed-off firearm, and 27% involved a firearm-like weapon (e.g., airgun, imitation firearm) or an unknown firearm.Note

The relatively large proportion of handgun crime across the country was mainly due to the fact that these weapons are most common in incidents in southern urban areas, and more particularly in big cities, where most of the population lives and where the majority of firearm-related violent crime is recorded. In southern urban areas, 62% of firearm-related violent crime involved a handgun. In Toronto, the largest CMA in Canada, this proportion was 83% (Chart 12).

Chart 12 start

Data table for Chart 12

| Census metropolitan areas, and southern and northern urban and rural areas | Handgun | Rifle or shotgun | Fully-automatic or sawed-off firearm | Firearm-like weapon or type of firearm unknownData table for Chart 12 Note 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| percent | ||||

| Halifax | 56.2 | 15.3 | 4.4 | 24.1 |

| Montréal | 63.6 | 3.2 | 4.8 | 28.4 |

| OttawaData table for Chart 12 Note 1 | 70.5 | 4.2 | 1.5 | 23.9 |

| TorontoData table for Chart 12 Note 2 | 82.6 | 2.3 | 0.5 | 14.6 |

| HamiltonData table for Chart 12 Note 3 | 70.0 | 2.6 | 3.0 | 24.3 |

| Kitchener-Cambridge-Waterloo | 57.4 | 3.2 | 3.2 | 36.1 |

| London | 65.7 | 5.7 | 2.1 | 26.4 |

| Winnipeg | 58.7 | 11.9 | 6.7 | 22.7 |

| Regina | 24.7 | 23.3 | 17.9 | 34.1 |

| Saskatoon | 41.1 | 13.7 | 23.7 | 21.6 |

| Calgary | 59.0 | 9.5 | 3.0 | 28.5 |

| Edmonton | 50.2 | 18.4 | 8.1 | 23.3 |

| Vancouver | 65.8 | 6.5 | 3.9 | 23.8 |

| Urban South | 62.4 | 9.1 | 4.3 | 24.2 |

| Urban North | 43.1 | 21.9 | 7.0 | 28.0 |

| Rural South | 25.5 | 33.0 | 5.9 | 35.6 |

| Rural North | 15.6 | 37.5 | 6.6 | 40.2 |

| Territories | 32.1 | 39.2 | 0.5 | 28.3 |

| Canada | 52.6 | 15.4 | 4.8 | 27.2 |

Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics, Uniform Crime Reporting Survey (Trend Database). |

||||

Chart 12 end

The proportion of firearm-related violent crimes involving handguns was much lower in some CMAs with the highest rates of gun violence. In Regina, the CMA with the highest rate of firearm-related violent crime in the country, a quarter (25%) of these crimes were committed with a handgun in 2022. In Saskatoon, this proportion was 41%.

However, handguns accounted for the lowest proportion of firearm-related violent crime in rural areas. More specifically, a quarter (25%) of firearm-related violent crime in southern rural areas involved handguns. In northern rural areas, this proportion was 16%.

Increases in firearm-related violent crime seen with all types of firearms

Handguns are often at the forefront of discussions and debates on gun control, as evidenced by the recent “freeze on the handgun market” (see Text box 3). While the rate of violent crime involving handguns has increased by 50% since the low in 2013 (from 12.8 to 19.3 incidents per 100,000 population), the trend is relatively similar for all types of firearms. For example, the rate of violent crime involving a fully automatic firearm or a sawed-off rifle or shotgun—prohibited weapons—was up 35% during the same period. Crimes involving a rifle or shotgun rose 45% (Table 4, Chart 13).

Chart 13 start

Data table for Chart 13

| Year | Handgun | Rifle or shotgun | Fully-automatic or sawed-off firearm | Firearm-like weapon or type of firearm unknownData table for Chart 13 Note 1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| rate per 100,000 population | ||||

| 2009 | 19.5 | 4.7 | 2.5 | 7.3 |

| 2010 | 15.4 | 5.0 | 2.0 | 6.9 |

| 2011 | 15.4 | 4.4 | 1.6 | 7.0 |

| 2012 | 14.5 | 4.3 | 1.5 | 6.9 |

| 2013 | 12.8 | 3.9 | 1.3 | 5.7 |

| 2014 | 14.0 | 4.0 | 1.1 | 5.9 |

| 2015 | 16.1 | 4.8 | 1.6 | 6.1 |

| 2016 | 16.1 | 5.1 | 1.3 | 6.3 |

| 2017 | 16.8 | 5.5 | 2.0 | 6.2 |

| 2018 | 17.3 | 5.2 | 1.8 | 5.9 |

| 2019 | 18.4 | 5.7 | 1.8 | 6.6 |

| 2020 | 17.7 | 6.1 | 1.7 | 8.5 |

| 2021 | 17.4 | 5.9 | 1.7 | 8.7 |

| 2022 | 19.3 | 5.7 | 1.7 | 10.0 |

Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics, Uniform Crime Reporting Survey (Trend Database). |

||||

Chart 13 end

However, the biggest increase was observed in the firearm-like or unknown weapon category. The rate for these crimes rose from 5.7 incidents per 100,000 population in 2013 to 10.0 incidents per 100,000 population in 2022, an increase of 76%. In 2022, these crimes represented 27% of all firearm-related violent crimes, compared to 21% in 2009 (Chart 14). This relatively large increase may be due in part to a higher number of incidents of discharging a firearm with intent; the proportion of these crimes for which the type of firearm was unknown was relatively high. But crime involving firearm-like weapons may also be on the rise, as various sources seem to indicate (Canada Border Services Agency, 2023, June 21; Mauro & Mancini, 2023, January 10; Royal Canadian Mounted Police, 2023, September 19). Bill C-21 plans to better define and regulate firearm-like weapons, such as airsoft guns, BB guns, pellet guns, airguns or replica firearms.

Chart 14 start

Data table for Chart 14

| Year | Handgun | Fully-automatic or sawed-off firearm | Rifle or shotgun | Firearm-like weapon or type of firearm unknownData table for Chart 14 Note 1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| percent | ||||

| 2009 | 57.5 | 7.3 | 13.8 | 21.5 |

| 2010 | 52.6 | 6.7 | 17.1 | 23.6 |

| 2011 | 54.2 | 5.7 | 15.5 | 24.6 |

| 2012 | 53.3 | 5.6 | 15.7 | 25.5 |

| 2013 | 54.1 | 5.5 | 16.4 | 24.0 |

| 2014 | 56.0 | 4.5 | 15.9 | 23.5 |

| 2015 | 56.4 | 5.5 | 16.9 | 21.3 |

| 2016 | 55.9 | 4.6 | 17.8 | 21.7 |

| 2017 | 55.0 | 6.6 | 18.1 | 20.3 |

| 2018 | 57.3 | 5.9 | 17.3 | 19.5 |

| 2019 | 56.7 | 5.5 | 17.4 | 20.4 |

| 2020 | 51.9 | 5.1 | 18.0 | 24.9 |

| 2021 | 51.7 | 5.1 | 17.4 | 25.8 |

| 2022 | 52.6 | 4.8 | 15.4 | 27.2 |

Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics, Uniform Crime Reporting Survey (Trend Database). |

||||

Chart 14 end

Compared with 2009, the proportion firearm-related violent crime involving handguns decreased slightly in urban areas, but increased in rural areas

Handguns are more often linked to gun violence in urban areas. As previously indicated, almost two-thirds (62%) of firearm-related violent crime in southern urban areas involved a handgun in 2022, approximately four times higher than in northern rural areas. Conversely, firearm-related violent crime in rural areas more often involves a rifle or shotgun. However, this difference tends to diminish over time. In rural areas, and especially in the territories, the number of handgun-related crimes has increased more rapidly than the number of crimes involving rifles or shotguns.

In 2009, police services in the territories reported seven violent crimes involving handguns, which was 8.2% of all firearm-related violent crime in the territories that year. In 2022, this proportion almost quadrupled, as there were 68 violent crimes involving handguns, which was 32% of all firearm-related violent crime in the territories.

In the Provincial North, the proportion of firearm-related violent crime that involved a handgun has also increased significantly. In northern rural areas, this proportion rose from 11% in 2009 to 16% in 2022 (+45%). In northern urban areas, the proportion of firearm-related violent crime that involved a handgun increased from 30% in 2009 to 43% in 2022 (+45%). Rural areas in the south were not spared from this trend, though the increase was more modest (+14%) (Chart 15).

Chart 15 start

Data table for Chart 15

| Year | Provincial urban South | Provincial rural South | Provincial urban North | Provincial rural North | Territories |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| percent | |||||

| 2009 | 66.3 | 22.4 | 29.7 | 10.8 | 8.2 |

| 2010 | 61.2 | 22.5 | 34.7 | 14.7 | 8.7 |

| 2011 | 63.2 | 23.4 | 36.7 | 13.0 | 5.6 |

| 2012 | 63.0 | 22.6 | 45.1 | 13.3 | 5.1 |

| 2013 | 63.1 | 22.1 | 47.3 | 14.5 | 12.7 |

| 2014 | 65.8 | 22.8 | 39.1 | 17.9 | 8.7 |

| 2015 | 65.6 | 24.8 | 42.2 | 18.3 | 17.9 |

| 2016 | 64.9 | 26.5 | 41.4 | 20.2 | 13.0 |

| 2017 | 64.5 | 25.9 | 40.6 | 16.4 | 4.6 |

| 2018 | 66.6 | 24.4 | 39.2 | 21.4 | 16.7 |

| 2019 | 66.7 | 24.9 | 38.2 | 16.9 | 21.9 |

| 2020 | 63.3 | 18.6 | 35.6 | 19.5 | 25.8 |

| 2021 | 62.2 | 26.9 | 44.7 | 17.5 | 27.5 |

| 2022 | 62.4 | 25.5 | 43.1 | 15.6 | 32.1 |

|

Note: Rural police services are those where the majority of the population lives outside of a census metropolitan area (CMA) or census agglomeration (CA). Urban police services are those where the majority of the population lives within a CMA or CA. See "Data sources and concepts" for further information. Provincial North encompasses the northern regions of Newfoundland and Labrador, Ontario, Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta and British Columbia (North and South ― Variant of Standard Geographical Classification 2021). Firearm-related violent crimes include incidents where the most serious violation is a firearm-specific violent offence (pointing a firearm, discharging a firearm with intent, use of a firearm in the commission of an offence) and other violent crimes where the most serious weapon present in the incident was a firearm. The number of incidents represents the number of victims, in addition to incidents for which the police did not provide victim records.

Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics, Uniform Crime Reporting Survey (Trend Database). |

|||||

Chart 15 end

In southern urban areas, the proportion of firearm-related violent crime that involved handguns fell slightly from 66% in 2009 to 62% in 2022. Nevertheless, the number of crimes involving handguns in southern urban areas rose during this period. However, the increase was faster for crime involving a firearm-like weapon or unknown weapon, as well as for crimes involving a rifle or shotgun. In contrast, the number of crimes involving a fully automatic or sawed-off firearm has declined 33% since 2009.

Men aged 18 to 24 are most likely to be victims of firearm-related violent crimes

Among victims whose genderNote was known, women accounted for just over half (53%) of the victims of all police-reported violent crimes in 2022. However, the picture is different when these crimes involved a firearm. According to police-reported data, in 2022, men accounted for about two-thirds (66%) of victims of firearm-related violent crime. More specifically, police services in Canada reported 38.7 firearm-related violent crimes per 100,000 men (3.6% of violent crimes targeting men) compared with 19.5 incidents per 100,000 women (1.6% of violent crimes targeting women) (Chart 16).

Chart 16 start

Data table for Chart 16

| Age group of victim | Firearm-related violent crime rate | Proportion of violent crimes that were firearm-related |

|---|---|---|

| rate per 100,000 population | percentage of violent crimes | |

| Men | ||

| Under 12 | 6.5 | 1.6 |

| 12 to 17 | 76.3 | 4.2 |

| 18 to 24 | 86.6 | 5.1 |

| 25 to 34 | 68.7 | 4.0 |

| 35 to 44 | 49.2 | 3.5 |

| 45 to 54 | 33.6 | 2.9 |

| 55 to 64 | 17.2 | 2.3 |

| 65 and over | 6.6 | 2.2 |

| Total | 38.7 | 3.6 |

| Women | ||

| Under 12 | 4.0 | 0.8 |

| 12 to 17 | 36.9 | 1.4 |

| 18 to 24 | 47.7 | 2.0 |

| 25 to 34 | 37.0 | 1.7 |

| 35 to 44 | 25.6 | 1.5 |

| 45 to 54 | 17.7 | 1.7 |

| 55 to 64 | 9.0 | 1.7 |

| 65 and over | 2.9 | 1.5 |

| Total | 19.5 | 1.6 |

|

Note: Includes incidents for which the police provided a victim record. Firearm-related violent crimes include incidents where the most serious violation is a firearm-specific violent offence (pointing a firearm, discharging a firearm with intent, use of a firearm in the commission of an offence) and other violent crimes where the most serious weapon present in the incident was a firearm. Excludes victims whose ages were reported as 80 years and older, but were identified as possible instances of miscoding, as well as victims in Quebec whose ages were unknown but were miscoded as 0. The option for police to code victims and accused persons as “non-binary” in the Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR) Survey was implemented in 2018. In the context of the UCR Survey, the term “non-binary” refers to a person who publicly expresses as neither exclusively man nor exclusively woman. Given that small counts of victims and accused persons identified as being non-binary may exist, the UCR data available to the public have been recoded with these victims and accused persons distributed in the “men/boys” or “women/girls” categories based on the regional distribution of gender for the victims and accused persons. This recoding ensures the protection of the confidentiality and privacy of victims and accused persons. Excludes victims where their gender was unknown. Rates are calculated on the basis of 100,000 population. Populations are based upon July 1 estimates from Statistics Canada, Centre for Demography. Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics, Uniform Crime Reporting Survey (Trend Database). |

||

Chart 16 end

Men aged 18 to 24 were most likely to have been the target of a violent crime involving a firearm in 2022. Police reported 86.6 victims per 100,000 men in this age group. Among victims in this age group, the proportion of incidents involving a firearm was also higher. Among men aged 18 to 24, 5.1% of violent crimes were committed with firearms in 2022.

Boys aged 12 to 17 had the second-highest victim rate—that is, 76.3 victims of firearm-related violent crime per 100,000 boys in this age group—and 4.2% of crimes targeting this group were committed with a firearm.

Overall, firearm-related violent crime with victims aged 18 to 24 has been declining since 2019. In 2022, the rate of firearm-related violent crime with victims aged 18 to 24 was lower than in 2009 (68.0 compared with 81.0 incidents per 100,000 population, respectively) (Chart 17).

Chart 17 start

Data table for Chart 17

| Year | Under 12 | 12 to 17 | 18 to 24 | 25 to 34 | 35 and over |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rate per 100,000 population | |||||

| 2009 | 7.1 | 57.3 | 81.0 | 45.3 | 17.5 |

| 2010 | 6.5 | 47.2 | 72.2 | 39.2 | 15.0 |

| 2011 | 6.8 | 45.3 | 71.6 | 38.2 | 14.4 |

| 2012 | 5.6 | 44.0 | 61.9 | 37.7 | 14.2 |

| 2013 | 4.8 | 34.6 | 58.0 | 33.9 | 12.3 |

| 2014 | 4.9 | 37.2 | 61.4 | 36.6 | 13.2 |

| 2015 | 6.0 | 38.5 | 70.9 | 43.2 | 14.8 |

| 2016 | 6.5 | 42.1 | 69.8 | 44.6 | 14.5 |

| 2017 | 5.2 | 47.7 | 72.4 | 45.0 | 16.3 |

| 2018 | 5.2 | 43.1 | 69.7 | 45.7 | 15.7 |

| 2019 | 4.6 | 46.9 | 74.6 | 48.8 | 15.9 |

| 2020 | 4.7 | 42.1 | 73.7 | 52.4 | 17.1 |

| 2021 | 4.4 | 45.8 | 69.8 | 52.6 | 16.6 |

| 2022 | 5.6 | 57.1 | 68.0 | 53.4 | 18.7 |

|

Note: Includes incidents for which the police provided a victim record. Firearm-related violent crimes include incidents where the most serious violation is a firearm-specific violent offence (pointing a firearm, discharging a firearm with intent, use of a firearm in the commission of an offence) and other violent crimes where the most serious weapon present in the incident was a firearm. Excludes victims whose ages were reported as 80 years and older, but were identified as possible instances of miscoding, as well as victims in Quebec whose ages were unknown but were miscoded as 0. Rates are calculated on the basis of 100,000 population. Populations are based upon July 1 estimates from Statistics Canada, Centre for Demography. Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics, Uniform Crime Reporting Survey (Trend Database). |

|||||

Chart 17 end

Since the low in 2013, the increase in the rate of firearm-related violent crime has mostly been driven by incidents with victims aged 12 to 17 (+65%) and aged 25 to 34 (+58%). The increase was particularly strong for 12 to 17-year-olds over the previous two years, with the rate having increased 36% from 2020 to 2022.

Women represent close to 9 in 10 victims of firearm-related violent crimes committed by an intimate partner

Overall, men represent the majority of victims of firearm-related violent crime, accounting for about two-thirds (66%) of victims in 2022—a proportion that has remained relatively stable since 2009. However, this proportion greatly varied depending on the relationship of the accused to the victim. In particular, women represented 89% of victims of violent crime involving firearms committed by a spouse or an intimate partner, and nearly half (44%) of incidents in which the perpetrator was another family member.

Moreover, violent crime perpetrated by an intimate partner or family member was less likely than crime perpetrated by a stranger to have been committed with a handgun. Among firearm-related violent crimes committed by an intimate partner or family member in 2022, 34% involved a handgun, while 28% involved a rifle or shotgun. When the accused person was a stranger, these proportions were 66% and 9.0%, respectively. This pattern was similar regardless of the victim’s gender.

Overall, firearm-related violent crime was mostly committed by strangers. In 2022, just over half (52%) of victims of firearm-related violent crime had been targeted by a person who was unknown to them. This proportion was much higher than that generally observed for violent crime, 26% of which was committed by a stranger in 2022. Conversely, relatively few firearm-related violent crimes involved a spouse or an intimate partner (9.2%) or a family member (6.0%) when compared with what is observed for violent crime in general (26% and 15%, respectively) (Chart 18).

Chart 18 start

Data table for Chart 18

| Type of violent crime | Spouse or intimate partner | Other family member | Friend or acquaintance | Stranger |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| percent | ||||

| All violent crimes | ||||

| Urban areas | ||||

| Men | 11.2 | 10.5 | 36.3 | 42.0 |

| Women | 38.5 | 14.0 | 29.0 | 18.6 |

| Total | 25.3 | 12.3 | 32.6 | 29.8 |

| Rural areas | ||||

| Men | 15.5 | 21.2 | 44.9 | 18.4 |

| Women | 41.3 | 22.3 | 29.2 | 7.3 |

| Total | 30.2 | 21.8 | 35.9 | 12.1 |

| All areas | ||||

| Men | 12.1 | 12.7 | 38.1 | 37.0 |

| Women | 39.2 | 16.0 | 29.0 | 15.8 |

| Total | 26.4 | 14.5 | 33.3 | 25.8 |

| Firearm-related violent crimes | ||||

| Urban areas | ||||

| Men | 1.4 | 3.3 | 30.9 | 64.4 |

| Women | 21.2 | 6.0 | 24.8 | 48.0 |

| Total | 7.8 | 4.2 | 29.0 | 59.0 |

| Rural areas | ||||

| Men | 2.6 | 13.0 | 54.6 | 29.7 |

| Women | 33.3 | 13.9 | 34.8 | 17.9 |

| Total | 14.8 | 13.3 | 46.8 | 25.1 |

| All areas | ||||

| Men | 1.6 | 5.1 | 35.3 | 58.0 |

| Women | 24.0 | 7.8 | 27.2 | 41.0 |

| Total | 9.2 | 6.0 | 32.6 | 52.2 |

|

Note: Includes victims with a known accused. If there were more than one accused, only the closest relationship to the victim was recorded. Excludes victims where the gender or the accused-victim relationship was unknown. The option for police to code victims and accused persons as “non-binary” in the Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR) Survey was implemented in 2018. In the context of the UCR Survey, the term “non-binary” refers to a person who publicly expresses as neither exclusively man nor exclusively woman. Given that small counts of victims and accused persons identified as being non-binary may exist, the UCR data available to the public have been recoded with these victims and accused persons distributed in the “men/boys” or “women/girls” categories based on the regional distribution of gender for the victims and accused persons. This recoding ensures the protection of the confidentiality and privacy of victims and accused persons. Firearm-related violent crimes include incidents where the most serious violation is a firearm-specific violent offence (pointing a firearm, discharging a firearm with intent, use of a firearm in the commission of an offence) and other violent crimes where the most serious weapon present in the incident was a firearm. Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics, Uniform Crime Reporting Survey (Trend Database). |

||||

Chart 18 end

Men in urban areas were most likely to have been targeted by a stranger in violent crime incidents involving a firearm in 2022. Almost two-thirds (64%) of male victims of a firearm-related violent crime in these regions were targeted by a stranger in 2022. Conversely, women in rural areas were less likely to have been targeted by a stranger (18%) and were more likely targeted by a spouse or intimate partner (33%) or by a friend or acquaintance (35%).

Despite an increase from 2021, the proportion of firearm-related violent crimes perpetrated by a stranger has generally been declining since 2009. In 2009, nearly two-thirds (65%) of firearm-related violent crimes were perpetrated by a stranger, compared to 52% in 2022. During the same period, the proportion of firearm-related violent crimes perpetrated by a spouse or intimate partner jumped by more than half, from 6.0% in 2009 to 9.2% in 2022, mainly due to crimes perpetrated by a boyfriend or ex-boyfriend (Chart 19).

Chart 19 start

Data table for Chart 19

| Year | Spouse or intimate partner | Other family member | Friend or acquaintance | Stranger |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| percent | ||||

| 2009 | 6.0 | 4.5 | 24.8 | 64.8 |

| 2010 | 6.9 | 4.6 | 26.2 | 62.3 |

| 2011 | 7.3 | 4.9 | 25.9 | 61.9 |

| 2012 | 7.8 | 4.7 | 26.6 | 60.9 |

| 2013 | 8.0 | 5.1 | 26.5 | 60.4 |

| 2014 | 8.0 | 5.0 | 27.3 | 59.6 |

| 2015 | 7.4 | 5.5 | 26.3 | 60.9 |

| 2016 | 8.2 | 5.3 | 28.3 | 58.1 |

| 2017 | 8.2 | 5.7 | 28.4 | 57.7 |

| 2018 | 8.5 | 5.3 | 29.0 | 57.2 |

| 2019 | 9.1 | 4.8 | 30.3 | 55.8 |

| 2020 | 9.8 | 6.1 | 33.4 | 50.8 |

| 2021 | 10.6 | 6.3 | 34.9 | 48.2 |

| 2022 | 9.2 | 6.0 | 32.6 | 52.2 |

|

Note: Includes victims with a known accused. If there were more than one accused, only the closest relationship to the victim was recorded. Excludes victims for which the accused-victim relationship was unknown. Firearm-related violent crimes include incidents where the most serious violation is a firearm-specific violent offence (pointing a firearm, discharging a firearm with intent, use of a firearm in the commission of an offence) and other violent crimes where the most serious weapon present in the incident was a firearm. Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics, Uniform Crime Reporting Survey (Trend Database). |

||||

Chart 19 end

The proportion of firearm-related violent crimes perpetrated by a friend or acquaintance also increased during this period, from 25% in 2009 to 33% in 2022. This increase is mainly due to a higher number of crimes having been committed by an acquaintance specifically. The proportion of crimes perpetrated by a neighbor also posted a sharp increase during this period; 1.2% of firearm-related violent crimes were perpetrated by a neighbor in 2009, compared to 2.5% in 2022.

Overall, the changes noted in the relationship between the victim and the accused in firearm-related violent crime mainly reflects patterns in urban areas, where these changes were noted among both male and female victims. For example, the proportion of firearm-related violent crimes in urban areas with a male victim perpetrated by a stranger went from 73% in 2009 to 64% in 2022. Among women, these proportions were 68% and 48%, respectively. During the same period, the proportion of women in urban areas who were targeted by a spouse or intimate partner increased from 11% to 21%.

This downward trend in the proportion of crimes committed by strangers is mostly observed in violent crimes involving handguns, and to a lesser extent, those involving a fully automatic or sawed-off firearm. For example, 78% of handgun-related violent crimes in 2009 were perpetrated by a stranger. This proportion had fallen to 63% in 2022.

Violent crimes involving firearms are less likely than violent crimes in general to cause injuries, but more likely to result in major injuries

Compared with violent crimes overall, victims of firearm-related violent crimes are less likely to sustain injuries. In 2022, 38% of victims of violent crimes involving a firearm sustained injuries, whether the injuries were inflicted by a firearm, another weapon or physical force. This proportion is lower than the proportion for all violent crimes, 45% of which resulted in injuries (Chart 20).Note

Chart 20 start

Data table for Chart 20

| Type of violent crime | No injury | Minor injuries | Major injuries | Death |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| percent | ||||

| Firearm-related violent crimes | 62.5 | 24.8 | 9.1 | 3.6 |

| All violent crimes | 54.9 | 42.3 | 2.6 | 0.3 |

|

Note: Includes incidents for which the police provided a victim record. Firearm-related violent crimes include incidents where the most serious violation is a firearm-specific violent offence (pointing a firearm, discharging a firearm with intent, use of a firearm in the commission of an offence) and other violent crimes where the most serious weapon present in the incident was a firearm. The data presented in this chart reflects all victims who suffered injuries, regardless of the weapon that caused the injuries. For example, some victims of firearm-related crimes may have suffered injuries that were not caused by a firearm (e.g., physical force); these victims would still be categorized as victims of a firearm-related crime who were injured. The percent calculation excludes victims for whom the level of injuries was unknown or not specified. Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics, Uniform Crime Reporting Survey (Trend Database). |

||||

Chart 20 end

However, firearm-related violent crimes were much more likely to result in major injuries or the death of the victim. In 2022, almost 1 in 10 firearm-related violent crimes (9.1%) resulted in major injuries, and 3.6% resulted in the death of the victim. Among all violent crimes, these proportions were 2.6% and 0.3%, respectively.

This trend was similar regardless of the victim’s gender, although firearm-related violent crimes involving male victims were more likely to have resulted in major injuries (11.6%) or the death of the victim (4.6%). For crimes with female victims, these proportions were 3.9% and 1.5%, respectively.

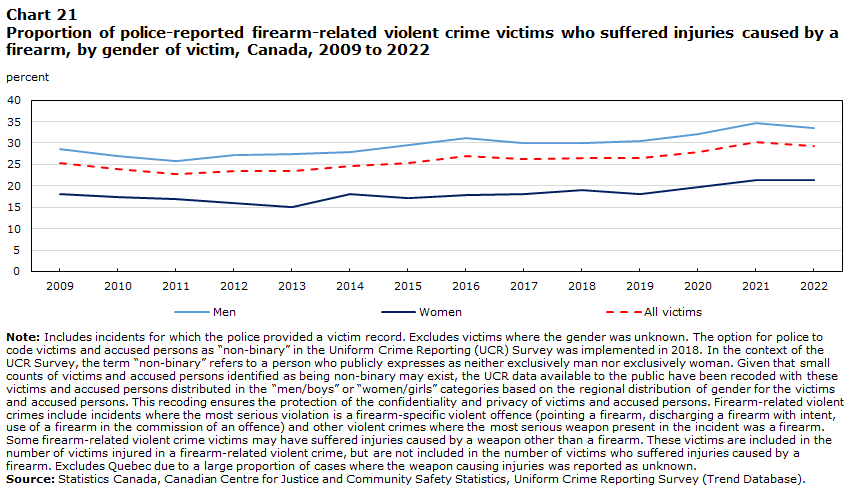

Slight decrease in the proportion of victims injured by a firearm despite an upward trend

In 2022, the proportion of victims of firearm-related violent crime who sustained injuries caused by a firearm declined slightly from the previous year (from 30% in 2021 to 29% in 2022). However, aside from this slight decline in 2022, it is noted that an increasing proportion of victims were injured by a firearm. The year 2011 represented a low, where 23% of victims of violent crime involving firearms suffered injuries.Note Following this, the proportion generally increased year after year until 2022. A particularly large increase was seen among female victims of firearm-related violent crime. In 2013, 15% of them suffered injuries caused by a firearm. In 2022, this proportion rose to 21% (Chart 21).

Chart 21 start

Data table for Chart 21

| Year | Men | Women | All victims |

|---|---|---|---|

| percent | |||

| 2009 | 28.7 | 18.0 | 25.3 |

| 2010 | 27.1 | 17.4 | 23.8 |

| 2011 | 25.7 | 17.0 | 22.8 |

| 2012 | 27.2 | 16.0 | 23.5 |

| 2013 | 27.5 | 15.2 | 23.6 |

| 2014 | 28.0 | 18.1 | 24.7 |

| 2015 | 29.6 | 17.2 | 25.4 |

| 2016 | 31.1 | 17.8 | 26.9 |

| 2017 | 30.1 | 18.0 | 26.2 |

| 2018 | 29.9 | 19.1 | 26.5 |

| 2019 | 30.4 | 18.0 | 26.5 |

| 2020 | 32.0 | 19.7 | 28.0 |

| 2021 | 34.8 | 21.3 | 30.3 |

| 2022 | 33.4 | 21.3 | 29.3 |

|

Note: Includes incidents for which the police provided a victim record. Excludes victims where the gender was unknown. The option for police to code victims and accused persons as “non-binary” in the Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR) Survey was implemented in 2018. In the context of the UCR Survey, the term “non-binary” refers to a person who publicly expresses as neither exclusively man nor exclusively woman. Given that small counts of victims and accused persons identified as being non-binary may exist, the UCR data available to the public have been recoded with these victims and accused persons distributed in the “men/boys” or “women/girls” categories based on the regional distribution of gender for the victims and accused persons. This recoding ensures the protection of the confidentiality and privacy of victims and accused persons. Firearm-related violent crimes include incidents where the most serious violation is a firearm-specific violent offence (pointing a firearm, discharging a firearm with intent, use of a firearm in the commission of an offence) and other violent crimes where the most serious weapon present in the incident was a firearm. Some firearm-related violent crime victims may have suffered injuries caused by a weapon other than a firearm. These victims are included in the number of victims injured in a firearm-related violent crime, but are not included in the number of victims who suffered injuries caused by a firearm. Excludes Quebec due to a large proportion of cases where the weapon causing injuries was reported as unknown. Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics, Uniform Crime Reporting Survey (Trend Database). |

|||

Chart 21 end

Although proportionally fewer victims were injured in violent crime incidents involving firearms, the sharp rise in these crimes from 2021 to 2022 still meant that the rate of persons injured by firearms has increased slightly over this period. In fact, the rate of persons injured by firearms increased 4.8% for men and 11% for women (Chart 22).

Chart 22 start

Data table for Chart 22

| Year | Victims of firearm-related violent crime | Victims injured by a firearm | ||