Violence against seniors and their perceptions of safety in Canada

by Shana Conroy and Danielle Sutton, Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics

Highlights

- According to the General Social Survey on Canadians’ Safety (Victimization), there were about 128,000 senior victims of violence in Canada in 2019. Rates of violent victimization were five times lower among seniors aged 65 and older compared to younger Canadians (20 versus 100 incidents per 1,000 population).

- Overall, three-quarters (76%) of seniors who reported experiencing violent victimization in 2019 were physically assaulted.

- A smaller proportion of seniors, compared to younger Canadians, reported experiencing abuse by an intimate partner in the five years preceding the survey: 7.1% of seniors reported experiencing emotional or financial abuse and 1.5% reported experiencing physical or sexual abuse by an intimate partner.

- Most seniors were somewhat or very satisfied with their personal safety from crime (82%), perceived their neighbourhood as having a lower amount of crime than other areas in Canada (77%) and reported a somewhat or very strong sense of community belonging (72%).

- According to the Uniform Crime Reporting Survey, the rate of police-reported violence against seniors increased 22% between 2010 and 2020, with the largest increase observed in the past five years among senior men. In contrast, police-reported violence against non-seniors decreased 9% during the same time period, with increases observed beginning in 2015 (+12% between 2015 and 2020).

- In 2020, nearly two-thirds (64%) of senior victims of police-reported violence were victimized by someone other than a family member or intimate partner. Acquaintances were implicated for more than one in four (28%) senior victims of violence while one-quarter (24%) of senior victims were victimized by stranger.

- Senior women who experienced police-reported violence were twice as likely to have been victimized by an intimate partner compared with senior men (16% versus 7%).

- More than half (60%) of all police-reported violence against seniors involved the use of physical force and an additional 19% involved the presence of a weapon. About one-third (35%) of seniors suffered a physical injury as a result of the violence they experienced.

- In 2020, the rate of police-reported violence against seniors was highest in the territories and New Brunswick. Between 2015 and 2020, police-reported senior victimization increased in every province and territory.

- The rate of police-reported violence was higher for senior men than senior women in every province and territory in 2020, and in nearly all census metropolitan areas.

- In 2020, the overall rate of police-reported senior victimization in the provinces was higher in rural compared to urban areas (247 versus 214 per 100,000 population).

- Between 2000 and 2020, 944 seniors were victims of homicide in Canada, which accounted for 7% of all homicide victims during this time. The large majority (88%) of these homicides were solved by police.

- The homicide rate among seniors increased between 2010 and 2020 (+9%), driven by the homicides of senior men (+28%).

- Among senior men who were homicide victims, two-thirds (67%) were killed by a non-family member, most commonly a friend (30%) followed by a stranger (20%) or an acquaintance (17%). Among senior women who were homicide victims, two-thirds (67%) were killed by an intimate partner (32%) or family member (35%), while one in eight (13%) senior women were killed by a stranger.

Seniors comprise almost one-fifth of all Canadians and their proportion of the population continues to grow as baby-boomers (i.e., those born between 1946 and 1965) age (Statistics Canada 2022; Statistics Canada 2021). In 2020, Canada was home to 6.8 million persons aged 65 years and older, comprising 18% of the total population (Statistics Canada 2021). In fact, demographic projections using a medium-growth scenario predict that, by 2030, more than one in five Canadians will be seniors, a figure that increases to one in four by 2060 (Statistics Canada 2019b).Note

Overall, older Canadians are aging better, are more active and are engaging in fuller lifestyles than previous generations. At the same time, however, they remain at risk of experiencing violence at the hands of family members, intimate partners, friends, caregivers and others (Miszkurka et al. 2016). Among seniors, a greater proportion (54%) are women in large part due to women living longer, on average, than men. The gender mortality gap, however, has diminished in recent years and is forecasted to continue shrinking in light of increased life expectancy among Canadian men (Statistics Canada 2019a). The growing proportion of seniors in Canada highlights the importance of understanding their risk of being victimized and, relatedly, their perceptions of safety and feelings of security. When seniors experience victimization, knowing where it occurs, who perpetrates it and whether it is reported to the police is crucial to understanding and mitigating risk.Note

Although prevalence estimates vary, violence against seniors is thought to affect approximately one in eight older adults living in the Americas (Yon et al. 2017). The risk of experiencing various forms of abuse is heightened among certain segments of the senior population. Specifically, those who are socially isolated, cognitively impaired, physically frail, living in institutionalized settings or dependent upon others for care are at an increased risk of experiencing abuse (Brijnath et al. 2021; Pillemer et al. 2016). The consequences of abuse, which in turn intensify the risk of recurrence, include an increased likelihood of developing mental or physical health conditions, hospitalization, cognitive decline, nursing home placement and mortality (World Health Organization 2021; Yunus et al. 2019).

This Juristat article relies on multiple data sources to examine the nature and prevalence of violent victimization of seniors. In addition, the article presents the various factors associated with perceptions of crime and safety among seniors. Self-reported data from the 2019 General Social Survey on Canadians’ Safety (Victimization) are presented first, detailing seniors’ experiences of violent victimization and their perceptions of safety. The sections that follow present police-reported data from the Uniform Crime Reporting Survey and the Homicide Survey, providing detail on annual trends, accused-victim relationships and incident characteristics. While 2020 was an unusual year due to the COVID-19 pandemic, police-reported incident data were similar for 2019 and 2020. As such, this article reports the latest police-reported data from 2020.

Start of text box 1

Text box 1

Defining the “senior” population

While seniors comprised 18% of the Canadian population in 2020, the proportion living in each of the provinces and territories varied. The Atlantic provinces and Quebec were home to the largest proportion of seniors, accounting for 20% to 22% of residents in each province (Statistics Canada 2021). The territories, on the other hand, were home to the smallest proportion of seniors: 4% of the population in Nunavut, 9% in the Northwest Territories and 13% in Yukon were seniors. The proportion of seniors living in Alberta was also relatively small (14%). The proportion of seniors living in each province and territory could impact how senior victimization is defined and the measures implemented to address it.

With an aging population in Canada, ongoing discussion and debates surround which age cut-off should be used to signify senior citizens. In keeping with the typical age of retirement and the age at which many individuals are entitled to receive full pension benefits, much of the research adopts a minimum age threshold of 65 years (Arriagada 2020; Gilmour and Ramage-Morin 2020).

Alongside an increasing life expectancy, higher proportions of seniors are living active lifestyles and continuing in the workforce beyond retirement age which challenges the appropriateness of using 65 years as a minimum threshold to denote senior citizens. Rather, some researchers advocate considering specific health, physical or cognitive abilities as a best practice to defining “senior” citizens (Addington 2012). While doing so would produce a valid definition, practical needs exist to quickly categorize segments of the population, calling for a definition which uses chronological age.

Using a single minimum age threshold threatens to obscure differences within a diverse group who have unique experiences, strengths and vulnerabilities throughout their senior years. One solution is to use multiple age subcategories. For example, some researchers have adopted a minimum age requirement (e.g., 60 or 65 years) to classify seniors and then use additional subcategories increasing in increments of ten years (e.g., 65 to 74 years, 75 to 84 years, and 85 years and older) to capture different experiences across the lifespan (Bows 2019; Logan et al. 2019).

In this article, “senior” refers to Canadians aged 65 years and older.Note In contrast, “non-senior” refers to Canadians aged 64 years and younger, or 15 to 64 years of age in the case of self-reported data.

End of text box 1

Start of text box 2

Text box 2

Senior victimization: What is abuse?

In and across Canada, various definitions of senior abuse exist and they vary in scope. Some, such as New Brunswick and Alberta, define senior abuse broadly, focusing on any action or inaction which causes harm or jeopardizes an older person’s health or well-being (Department of Justice 2015). Others, such as Manitoba and British Columbia, note how senior abuse must be perpetrated by someone an older adult has come to trust, be it a spouse, relative, caregiver, friend or staff member employed at a long-term care facility (Department of Justice 2015; Preston and Wahl 2002). Finally, some, such as Nova Scotia, and Newfoundland and Labrador, favour a broad definition while recognizing that a breach of trust frequently occurs in instances of senior abuse (Department of Justice 2015).

The terms used—such as “elder abuse,” “abuse of older adults” or “abuse of vulnerable adults”—also vary. Regardless of the terminology used, definitions of senior abuse often detail common types of abuse. For example, the Advocacy Centre for the Elderly define senior abuse as harm perpetrated against an older person by someone in a special relationship to them, including:

- Physical abuse such as slapping, pushing, beating or forced confinement;

- Financial abuse such as stealing, fraud, extortion and misusing a power of attorney;

- Sexual abuse as sexual assault or any unwanted form of sexual activity;

- Neglect as failing to give an older person in your care food, medical attention or other necessary care, or abandoning an older person in your care; and

- Emotional abuse as in treating an older person like a child or humiliating, insulting, frightening, threatening or ignoring an older person (ACE 2013).

As the above indicates, senior abuse can vary in terms of severity. While some of these acts meet the criminal threshold for prosecution in Canada (e.g., physical assault, sexual assault, extortion and criminal negligence causing bodily harm), others do not (e.g., humiliation).

End of text box 2

Section 1: Self-reported violent victimization among seniors

In Canada, the Uniform Crime Reporting Survey and the General Social Survey (GSS) on Canadians’ Safety (Victimization) are complementary data sources capturing both police- and self-reported victimization, respectively. While police-reported data are crucial to providing measurements of crime in Canada, they are limited to incidents that come to the attention of authorities. The majority of criminal incidents—especially those involving intimate partner violence and sexual assault—are not reported to police.Note Further, some evidence suggests that seniors are less likely to report victimization to police compared to younger Canadians (Cotter 2021a; Gabor and Kiedrowski 2009), thereby highlighting the importance of using self-reported data to complement police-reported statistics.

The true extent of senior victimization is difficult to measure. Some behaviours may not be perceived or recognized by seniors as abuse, while others do not meet the criminal threshold or—if they do—may not be reported to police, and some seniors are unable to report due to a disability. Consequently, both self-reported and police-reported data presented in this article may underestimate the degree of victimization among seniors in Canada. Keeping these caveats in mind, the aim of this section is to explore seniors’ self-reported experiences of violent victimization by drawing on findings from the 2019 GSS on Victimization.

The GSS on Victimization has a target population of persons aged 15 and older living in the community. As such, seniors living in institutionalized settings are not included in the survey. Similarly, seniors with severe disabilities may not have responded to the survey. The exclusion of both groups will impact public understanding of violence against seniors. About 7% of the senior population lives in institutional settings and an even larger proportion have declining cognitive or physical abilities, the latter of which increase the risk of violence against seniors (Pillemer et al. 2016; Walsh et al. 2011; WHO 2021).

Rate of violent victimization lower among seniors compared to younger Canadians

According to the GSS on Victimization, there were about 128,000 senior victims of violence—including physical assault, sexual assault and robbery—in Canada in 2019, a rate of 20 victims for every 1,000 Canadians aged 65 and older (Table 1).Note These self-reported data align with previous research documenting the relative low occurrence of violence experienced by seniors, often affecting about 2% of the senior population at any given time (MacDonald 2018; Policastro and Finn 2017; Rosay and Mulford 2017).

Keeping in mind that victimization typically declines with age (Cotter 2021a), the rate of violent victimization was significantly lower among seniors compared to younger Canadians—that is, those aged 15 to 64 (100 incidents per 1,000 population).Note The rate of violent victimization was also lower among senior women compared to non-senior women (24 versus 129) and among senior men compared to non-senior men (15 versus 70).

Among the senior population, the rate of violent victimization did not differ in a statistically significant way between senior women and senior men overall (24 versus 15). There were also no significant differences in the rate of violent victimization documented for seniors who are members of a visible minority group,Note in comparison to non-visible minority seniors and visible minority non-seniors (32E, 18 and 68, respectively).Note

Prior research has shown how rates of victimization are higher among people with a disability in general (Cotter 2021a) and among the senior population specifically (Pillemer et al. 2016; Walsh et al. 2011; WHO 2021). For seniors with a disability, rates of victimization may be higher due to increased dependency on caregivers, potential caregiver burnout and difficulties in defending themselves physically (Pillemer et al. 2016; Walsh et al. 2011). According to the GSS on Victimization, seniors who reported having a disabilityNote had a rate of violent victimization that was significantly higher than seniors who did not report having a disability (31 versus 11E incidents per 1,000 population).Note In contrast, however, the rate of violent victimization among seniors with a disability was lower than non-seniors with a disability (31 versus 181). Among those with a disability, senior women had a higher rate of violent victimization than senior men (42E versus 17E). The victimization rates among seniors with a disability are likely conservative estimates considering how the GSS excludes seniors living in institutional settings and those with a severe disability may not have responded to the survey.

Three-quarters of seniors who experience victimization are physically assaulted

Among those who experienced violent victimization in 2019, three-quarters (76%) of seniors were physically assaulted, a rate of 15 incidents per 1,000 population (Table 1). The rate of physical assault among seniors was significantly lower than what was documented for younger Canadians (54 incidents per 1,000 population).Note This finding applied to both senior women and men: the rate of assault was lower for senior women compared to non-senior women (16E versus 58) and the rate for senior men was lower compared to non-senior men (14 versus 50).

Among seniors who experienced violent victimization in 2019, sexual assault and robbery were less common than physical assault. The rate of sexual assault among seniors was 2.4E incidents per 1,000 population, significantly lower than the rate for younger Canadians (37).Note The same difference applied to senior and non-senior women (4.2E versus 63).Note Meanwhile, the rate for robbery was significantly lower among seniors than non-seniors (2.4E versus 8.2).Note Further analysis revealed that the significant difference observed between seniors and younger Canadians who were victims of robbery was driven by the rate of victimization among non-seniors aged 25 to 44.Note

A small proportion of seniors experience physical or sexual assault in intimate relationships

Intimate partner violence—a form of gender-based violence—includes a range of behaviours perpetrated by a current or former spouse or other intimate partner that can cause an individual to experience emotional, psychological, financial, sexual or physical harm. Regardless of age, the potential impacts of intimate partner violence can be immediate and enduring, and may result in victims feeling anxious, depressed, fearful and trapped by their partner (Cotter 2021b; Savage 2021). Much like their younger counterparts, seniors who experience intimate partner violence may be reluctant to disclose or discuss their experiences, thereby highlighting the importance of using victimization survey data to complement police-reported statistics. Again, data presented below may underestimate the scope of intimate partner violence among seniors considering how those living in institutional settings were not included in the GSS on Victimization, and those with certain disabilities might not have responded to the survey.

Among seniors with current or former intimate partners, 1.5% reported experiencing physical or sexual abuse by an intimate partner in the five years preceding the GSS on Victimization, significantly lower than the proportion of younger Canadians who experienced such abuse (6.9%) (Table 2).Note While the proportions of senior women and senior men who experienced intimate partner violence were not significantly different (2.3% and 0.9%, respectively), physical or sexual abuse by an intimate partner was higher among senior women aged 65 to 74 than similarly aged men (2.2% versus 1.1%).Note

When comparisons were made by gender, similar findings emerged. A smaller proportion of senior women (2.3%) experienced physical or sexual abuse by an intimate partner compared to non-senior women (7.6%) (Table 2). Likewise, a smaller proportion of senior men (0.9%) experienced such abuse compared to non-senior men (6.2%).

Fewer than one in ten seniors experience emotional or financial abuse by an intimate partner

Several studies have found psychological and financial abuse to be the most prevalent forms of senior victimization (Henderson et al. 2021; Rosay and Mulford 2017; Weissberger et al. 2020; Yon et al. 2017). While some of these behaviours may not reach the criminal threshold, they often carry detrimental consequences for victims, jeopardizing their economic security while undermining their sense of dignity and self-worth. Such abuse may result in victims’ withdrawal from social situations, and increased feelings of anxiety, hopelessness or inadequacy (Government of Canada 2017; Yunus et al. 2019). The GSS on Victimization includes questions related to emotionalNote and financialNote abuse.

Fewer than one in ten (7.1%) seniors reported experiencing emotional or financial abuse by an intimate partner in the five years preceding the GSS on Victimization, with similar proportions documented among senior women and senior men (7.2% and 7.0%, respectively) (Table 2).Note On the other hand, one in five (19%) Canadians between the ages of 15 and 64 experienced emotional or financial abuse by an intimate partner during the same time period, significantly higher than seniors. Additional analysis revealed that emotional or financial abuse by an intimate partner appears to decline with age. While a significantly lower proportion of seniors reported such abuse compared to younger age groups, the difference was smaller with increasing age (7.1% of seniors versus 35% of those aged 15 to 24, 21% of those aged 25 to 44 and 12% of those aged 45 to 64).Note

In addition to questions about emotional and financial abuse perpetrated by an intimate partner, the GSS on Victimization asked the same about relatives, friends and caregivers. A small proportion of seniors experienced emotional abuse (1.5%) or financial abuse (0.7%) from such a person in the five years preceding the survey (Table 2). Emotional abuse was significantly less common among seniors than non-seniors (1.5% versus 3.3%) while there was no notable difference for financial abuse (0.7% versus 1.0%).

Section 2: Perceptions of safety among seniors

Individual well-being is fundamentally associated with perceptions of personal safety. Early research (e.g., Hale 1996; Yin 1980) reinforced the conventional belief that seniors are more likely to fear crime compared to their younger counterparts, although they paradoxically experience lower rates of crime. Later research argued that seniors are not more fearful per se but behave more cautiously due to factors largely related to vulnerability (Greve et al. 2018). Fear of crime, or behavioural adaptations, may be heightened among seniors because some perceive themselves to be more vulnerable physically—ill-equipped to defend against an assault—and anticipate a longer recovery time should one occur (Hanslmaier et al. 2018; Sheppard et al. 2021). The aim of this section is to determine whether seniors’ perceptions of safety align with their lower rates of victimization documented above.

Large majority of seniors are somewhat or very satisfied with their personal safety from crime

According to the General Social Survey (GSS) on Canadians’ Safety (Victimization), and aligned with victimization patterns documented above, the large majority (82%) of seniors were somewhat or very satisfied with their personal safety from crime in 2019, a proportion that exceeded what was documented among younger Canadians (77%) (Table 3).Note Senior men were most satisfied with their personal safety from crime (86%) compared to both senior women (79%) and non-senior men (80%). In the provinces, a larger proportion of seniors living in rural areas reported being somewhat or very satisfied with their personal safety from crime compared to seniors living in urban areas (87% versus 81%).Note

There were no significant differences among Indigenous (First Nations, Métis and Inuit) and non-Indigenous seniors, and seniors who are and seniors who are not members of a visible minority group, in terms of satisfaction with personal safety from crime.Note Differences did emerge, however, when considering disability. Seniors with a disability were less likely than seniors with no disability to say they were satisfied with their personal safety from crime (80% versus 84%). Inversely, it was more common for seniors with a disability to say they were dissatisfied with their personal safety from crime (3.9%) or that they were neither satisfied nor dissatisfied (16%) than seniors with no disability (2.7% and 13%, respectively).

The GSS on Victimization asks several questions designed to measure Canadians’ satisfaction with their personal safety using behavioural indicators—such as while walking alone in the neighbourhood after dark, waiting for or using public transportation alone after dark, being home alone in the evening or at night—and whether they have taken measures to protect themselves or their property from crime.Note

Across these indicators a clear pattern emerged. A larger proportion of seniors reported feeling very or reasonably safe, or not at all worried about their personal safety from crime, compared to non-seniors (Table 3). The only exception was waiting for or using public transportation after dark, where feeling worried did not differ significantly between seniors and younger Canadians. Moreover, a smaller proportion of seniors reported taking measures in the previous 12 months to protect themselves or their property from crime than non-seniors (13% versus 23%).Note

Among seniors specifically, a significantly larger proportion of men than women reported feeling somewhat or very safe, or not at all worried about their safety from crime, across measures of perceived personal safety. That said, there was no statistically significant difference between senior men and women when it came to taking measures in the 12 months preceding the survey to protect themselves or their property from crime.

Most seniors perceive their neighbourhood as having a lower amount of crime compared to other areas in Canada

Aligned with positive perceptions of personal safety, and potentially due to less exposure to crime, over three-quarters (77%) of seniors perceived their neighbourhood as having a lower amount of crime compared to other areas in Canada, and this proportion was significantly higher than the proportion among younger Canadians who held the same view (70%) (Table 3).Note In contrast, significantly more Canadians aged 64 and younger perceived their neighbourhood to have a higher level of crime compared to other areas in Canada (4.9% versus 3.0% of seniors).

Similarly, it was more common for seniors (81%) to believe that crime in their neighbourhood had remained about the same over the five years preceding the GSS on Victimization than non-seniors (72%), despite national increases in the volume and severity of crime during the same period (Moreau et al. 2020).Note A greater proportion of non-seniors, on the other hand, held the view that crime in their neighbourhood had increased over the preceding five years than what was observed with seniors (21% versus 13%).

Similar patterns were observed when focusing on seniors specifically when comparing perceptions of crime between those who live in provincial rural areas and those who live in urban areas in the provinces. For example, a larger proportion of seniors living in rural areas perceived crime in their neighbourhood to be lower than other areas in Canada compared to seniors living in urban areas (88% versus 74%).Note In contrast, larger proportions of seniors living in urban areas perceived the level of crime in their neighbourhood to be about the same (21%) or higher (3.5%) than other areas in Canada compared to their rural counterparts (9.8% and 1.0%, respectively).

Seven in ten seniors report a somewhat or very strong sense of community belonging

Prior research has found that, across all age groups, feelings of community belonging are positively associated with physical and, to a greater extent, mental health (Michalski et al. 2020). Almost three-quarters (72%) of seniors reported a somewhat or very strong sense of community belonging, and this figure was significantly higher than what was documented among younger Canadians (58%) (Table 3).Note With considerably more free time available among seniors in general, some studies have noted an increase in leisure activity engagement during retirement (Evenson et al. 2002; Henning et al. 2020; Lee et al. 2020), allowing for increased opportunities to foster community belonging. Further analysis revealed, however, that a somewhat or very strong sense of community belonging was less common among seniors with a personal income of less than $30,000 per year compared to seniors who had a personal income of $30,000 or more per year (70% versus 74%).Note

While there were no significant differences among Indigenous and non-Indigenous seniors in terms of community belonging, seniors who are members of a visible minority group were less likely to report they had a somewhat or very strong sense of community belonging (61% versus 74% of non-visible minority seniors).Note Similarly, seniors with a disability less often said they had a somewhat or very strong sense of community belonging (70%) and more often said they had a somewhat or very weak sense of community belonging (18%) than seniors with no disability (74% and 14%, respectively).

Overall, a greater proportion of seniors reported that many people in the neighbourhood know each other (46% versus 31% of non-seniors) and that many people in the neighbourhood help each other (84% versus 81% of non-seniors) (Table 3).Note Among those who had lived in their neighbourhood for less than a year, there was no difference between seniors and non-seniors in terms of the proportions who reported that many people know each other. Seniors were, however, more likely than non-seniors to say that many people in the neighbourhood know each other when they had lived there for a longer time—that is, one to five years, five to ten years or ten years or more.Note

Tied to favourable perceptions of neighbourhood crime, a smaller proportion of seniors reported the presence of at least one indicator of social disorder than non-seniors (42% versus 60%) (Table 3).Note Among the senior population exclusively, however, a larger proportion with a personal income of less than $30,000 per year reported social disorder being a big problem in their neighbourhood compared to seniors who had a personal income of $30,000 or more per year (6.3% versus 4.0%).Note Social disorder refers to noisy neighbours, people hanging around on the streets, garbage or litter, vandalism or graffiti, violence motivated by race or ethnicity, the use or dealing of drugs and public intoxication or rowdiness.

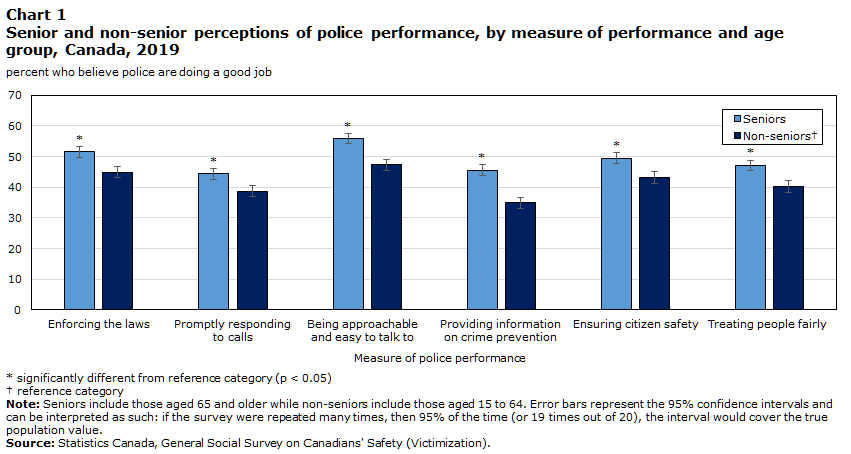

Seniors most commonly believe local police do a good job across all measures of performance

Across all measures of police performance collected by the GSS on Victimization, a greater proportion of seniors believed police were doing a good job relative to younger Canadians (Chart 1; Table 4). Compared to seniors, a larger proportion of non-seniors reported that police were doing an average or poor job across all indicators of police performance.

Chart 1 start

Data table for Chart 1

| Measure of police performance | Seniors | Non-seniorsData table for Chart 1 Note † | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| percent who believe police are doing a good job | 95% confidence interval | percent who believe police are doing a good job | 95% confidence interval | |||

| from | to | from | to | |||

| Enforcing the laws | 51.6Note * | 49.7 | 53.5 | 44.9 | 43.6 | 46.3 |

| Promptly responding to calls | 44.4Note * | 42.6 | 46.3 | 38.7 | 37.4 | 40.0 |

| Being approachable and easy to talk to | 55.9Note * | 54.1 | 57.7 | 47.3 | 46.0 | 48.7 |

| Providing information on crime prevention | 45.6Note * | 43.8 | 47.5 | 35.0 | 33.7 | 36.3 |

| Ensuring citizen safety | 49.5Note * | 47.7 | 51.4 | 43.2 | 41.9 | 44.5 |

| Treating people fairly | 47.2Note * | 45.3 | 49.0 | 40.2 | 39.0 | 41.5 |

Source: Statistics Canada, General Social Survey on Canadians' Safety (Victimization). |

||||||

Chart 1 end

Separating by gender, results from the GSS on Victimization showed that a larger proportion of senior men and senior women believed police were doing a good job across all performance indicators compared to younger men and younger women, respectively (Table 4). In terms of seniors who believed police were doing a good job, no significant differences were observed between senior women and senior men for any performance indicator. Across all indicators, however, significantly more senior men believed police were doing a poor job compared to senior women.

Aligned with the finding that most seniors believed police were doing a good job, half (50%) of all seniors reported having a great deal of confidence in police,Note a proportion that was significantly higher than among non-seniors (39%).Note Senior men more often reported having a great deal of confidence in police relative to younger men (49% versus 38%). Similarly, senior women more often reported having a great deal of confidence in police compared to younger women (50% versus 39%).

Indigenous seniors were more likely to report that they have not much or no confidence in police compared to their non-Indigenous counterparts (10%E versus 4.9%). Similarly, a larger proportion of seniors who are members of a visible minority group said the same compared to those who are non-visible minorities (9.7% versus 4.5%).Note Among seniors with a disability, a great deal of confidence was less common (46%), but some confidence was more common (48%), compared to seniors with no disability (53% and 42%, respectively).

Section 3: Police-reported violence against seniors

Building on self-reported data, this section examines the victimization of Canadian seniors by drawing on findings from the Uniform Crime Reporting Survey. For information about police-reported violence against seniors during the COVID-19 pandemic, see Text box 4.

Police-reported violence against seniors increasing

In 2020, there were 389,919 victims of police-reported violence in Canada, 15,157 (4%) of whom were seniors (Table 5).Note The rate of senior violent victimization increased 22% between 2010 and 2020, and rate increases were observed for both women (+18%) and men (+25%). In contrast, for non-seniors, increases in the rate of police-reported violence was observed beginning in 2015. Since then, the rate of victimization among younger Canadians increased (+12%), more for women (+16%) than men (+8%).

Rates of police-reported violence increased for each senior age group between 2010 and 2020 (Chart 2). The largest increase since 2010 was observed among seniors aged 85 and older (+39%), although a decline occurred from 2019 to 2020. The increase since 2010 for this age group was driven almost entirely by the violent victimization of senior women; there was a 63% rate increase among women aged 85 and older (from 108 to 176 victims per 100,000 population), whereas the rate increased 3% for senior men of the same age (from 132 to 136 per 100,000). Meanwhile, among senior men, the largest increase between 2010 and 2020 was among those aged 75 to 84 (+29%). It should be noted, however, that seniors in general—and seniors aged 85 and older in particular—represent a small proportion of police-reported victims of violence (4% and 0.4% in 2020, respectively). As such, fluctuations in the number of victims can have a large impact on the rate of victimization and resulting trend.

Chart 2 start

Data table for Chart 2

| Year | Seniors aged 65 to 74 | Seniors aged 75 to 84 | Seniors aged 85 and older | Seniors aged 65 and older |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| rate per 100,000 population | ||||

| 2010 | 231 | 132 | 117 | 183 |

| 2011 | 219 | 131 | 120 | 177 |

| 2012 | 215 | 136 | 122 | 177 |

| 2013 | 210 | 129 | 132 | 175 |

| 2014 | 204 | 134 | 130 | 173 |

| 2015 | 212 | 143 | 135 | 181 |

| 2016 | 213 | 143 | 146 | 184 |

| 2017 | 224 | 154 | 166 | 196 |

| 2018 | 232 | 157 | 172 | 202 |

| 2019 | 257 | 178 | 210 | 227 |

| 2020 | 269 | 161 | 162 | 223 |

|

Note: Rates are calculated on the basis of 100,000 population. Populations based on July 1 estimates from Statistics Canada, Centre for Demography. Seniors include those aged 65 and older. Excludes victims where age was coded as unknown and those where age was greater than 110 are excluded from analyses due to possible instances of miscoding of unknown age within this age category. Based on the Incident-based Uniform Crime Reporting Survey, Trend Database, which, as of 2009, includes data for 99% of the population in Canada. As a result, numbers may not match those presented elsewhere in the report. Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics, Incident-based Uniform Crime Reporting Survey, Trend Database. |

||||

Chart 2 end

Nearly two-thirds of senior victims experience violence perpetrated by someone other than a family member or intimate partner

According to police-reported data, more than six in ten (64%) senior victims of violent crime were victimized by someone other than a family member or intimate partner in 2020, while this was the case for a relatively lower proportion of non-seniors (56%) (Table 6). Among senior victims, almost three-quarters (72%) of senior men and over half (54%) of senior women were victimized by a non-family member. Acquaintances and strangers were implicated for just over half (52%) of senior victims. This finding was more pronounced among senior men, where an equal proportion was victimized by a stranger (29%) or an acquaintance (29%), whereas just over one-quarter (27%) of senior women were victimized by an acquaintance and a smaller proportion by a stranger (16%).

These police-reported data counter research that suggests seniors are often victimized by a family member (Brijnath et al. 2021; Weissberger et al. 2020). That said, both studies cited focused on victimization that was reported to abuse resource hotlines, which included both criminal and non-criminal forms of abuse. As such, consideration must be given to the issue of underreporting to police. There are many reasons why someone, regardless of age, may not report victimization by a family member to police including, but not limited to, fear of retaliation, dependency on the offender, shame or embarrassment, privacy-related issues or a desire to protect the offender (Dowling et al. 2018; Roger et al. 2021).

Senior women more likely than senior men to experience violence perpetrated by a family member or intimate partner

Police-reported data showed that overall a larger proportion of seniors were victimized by a family member than non-senior victims (Table 6). Specifically, one in four (25%) senior victims were assaulted by a family member while this was the case for 15% of victims under the age of 65.

Of note, there were gender differences—specifically a larger proportion of senior women experienced violence by a family member relative to senior men (30% versus 22%). Within this group, senior women were most often victimized by their child or an extended family member (e.g., grandchildren, nieces, nephews and in-laws).

Senior women were twice as likely to have been victimized by an intimate partner compared to senior men (16% versus 7%). Non-senior women were also three times more likely to have been victimized by an intimate partner relative to non-senior men (42% versus 13%). Therefore, intimate partner violence remains a largely gendered phenomenon whereby women are victimized more often than men (Conroy 2021; Cotter 2021b).

Just over one-quarter of senior victims of police-reported violence are victimized by another senior

There were 7,241 police-reported incidents of violence against seniors in which there was a single victim and a single accused person.Note Of these, three-quarters (75%) were perpetrated by a male accused. In terms of age, the largest proportion of seniors were victimized by someone aged 25 to 44 (34%), followed closely by someone aged 45 to 64 (31%). Just over one-quarter (27%) of seniors victims of violence were victimized by someone aged 65 years or older. Among accused aged 25 to 64, the largest proportion (55%) victimized someone other than an intimate partner or family member. This finding was particularly true for accused who victimized senior men (65%), but less so for those who victimized senior women (39%). Instead, accused aged 25 to 64 who victimized senior women most often shared a non-spousal family relationship (49% compared to 27% for senior men).

Of the accused who were also seniors, again, most (63%) victimized someone other than an intimate partner or family member. This was more common among senior men than women accused who victimized another senior (78% versus 55%). About one in three (33%) accused persons aged 65 and older victimized an intimate partner and this was more common among senior women victims compared to men (41% versus 18%).

Charges less common for persons accused of violence against seniors than non-seniors

Of the incidents that involved a single victim and a single accused person, nearly six in ten (58%) persons accused of violence against seniors had charges laid or recommended against them, less common than those accused of violence against non-seniors (74%).Note The laying or recommendation of charges was most common among accused aged 25 to 44 (65%) and 45 to 64 (63%). While over half (55%) of accused aged 12 to 24 were involved in incidents that were cleared by charge, this applied to less than half (43%) of accused aged 65 and older who were accused of violence against another senior. That said, compared to younger victims, a larger proportion of seniors requested that no further action be taken against the accused despite there being sufficient evidence to support a charge (26% and 18%, respectively).

Physical assaults most common violations among senior victims of police-reported violence

Aligned with police-reported violent crime overall (Moreau 2021), among all seniors, regardless of victim gender, the most common violation type reported to police involved physical assaults, followed by other offences involving actual or threatened violence (Table 7). Specifically, of all police-reported violence in 2020, 67% of senior men and 62% of senior women were physically assaulted. Of these victims, nearly eight in ten (79%) seniors experienced level 1 assault and an additional one in five (20%) experienced a level 2 assault (assault with a weapon or causing bodily harm).Note There were slight gender differences in that a larger proportion of senior women experienced assault level 1 (84% versus 75% of senior men) and a larger proportion of senior men experienced assault level 2 (24% versus 15% of senior women). These patterns align with what was observed among younger men and women.

Among seniors who reported other offences involving actual or threatened violence to police, more than five in ten (56%) victims were threatened, about one in seven were robbed (15%) and a smaller proportion experienced criminal harassment (12%). Again, there were gender differences. While the largest proportion of both senior men and women experienced uttering threats (59% and 52%, respectively), a greater proportion of men were victims of robbery (18% versus 12% of senior women) whereas women were more often victims of criminal harassment (16% versus 9% of senior men).

Senior victims, both women (81%) and men (63%), were most often victimized inside a residential location.Note These figures exceed what was observed among younger Canadians, where 73% of non-senior women and 51% of non-senior men were victimized inside a residential location. These patterns, however, may be a result of lifestyle characteristics rather than age alone. For example, previous data show how victimization risk is elevated among those who frequently partake in evening activities outside the home and have consumed marijuana in the past 30 days (Cotter 2021a); behaviours which are arguably more common among the young.

Start of text box 3

Text box 3

Living arrangements of seniors

The preference for many seniors is to remain in the community, or age in place (Puxty et al. 2019), a reality for about nine in ten senior Canadians who currently live in the community (Public Health Agency of Canada 2020; Puxty et al. 2019). Further, research has shown the importance of living arrangements on seniors’ mental health and well-being (Puxty et al. 2019; Srugo et al. 2020). Senior Canadians who live with a spouse or partner, compared to those who live alone or with other relatives, report better measures of perceived mental health, physical health, life satisfaction and sense of community belonging (Srugo et al. 2020).

While police-reported data do not reveal precise living arrangements, of all seniors whose violent victimization was reported to police in 2020, almost three-quarters (71%) were victimized inside a residential location. Of these victims, 83% were victimized inside a private residence and 15% inside communal residence, namely a retirement or nursing home.Note These data may indicate an overrepresentation of seniors being victimized within institutional settings as, according to the Census of Population, a small proportion (7%) of all Canadian seniors live in such locations (Puxty et al. 2019).Note Seniors who were victimized in a communal residence were most commonly victimized by an acquaintance (40%), a neighbour (19%), a stranger (11%), a roommate (9%) or an authority figure (7%).Note

The limited number of studies examining criminal and non-criminal victimization among institutionalized seniors has documented high proportions of staff-resident and resident-resident abuse (ranging from 20% to 64%) (Lachs et al. 2016; Royal Commission 2020; Yon et al. 2018). One potential explanation for this overrepresentation is the number of institutionalized seniors living with dementia or other severe cognitive impairments. Data show that about four in ten seniors with dementia reside in institutions (Canadian Institute for Health Information 2021), and thus comprise a substantial proportion of all seniors living in institutional settings. Living with a cognitive impairment, such as dementia, is a well-documented risk factor for experiencing victimization (Pillemer et al. 2016; Yon et al. 2018).

Caution should be exercised in any discussion about victimization of seniors within institutionalized settings. Canadian survey data do not capture the institutionalized population and severe cognitive limitations preclude many seniors from providing consent and participating. Police-reported data, therefore, are often the best source available but limited to instances that come to the attention of authorities.

End of text box 3

Physical injury more common for senior men than senior women who experience violence

More than half (60%) of all police-reported violence against seniors involved the use of physical force and an additional 19% involved the presence of a weapon (Table 8). Of note, more than one in five senior men were victimized with a weapon while this was the case for about one in eight senior women (23% and 13%, respectively).

About one-third (35%) of seniors suffered a physical injury as a result of the incident, of which a higher proportion of men sustained an injury (37% versus 32% of women). The potential consequences of sustaining even a minor injury in older age are significant. Compared to non-seniors, seniors who suffer serious injuries are at a heightened risk of sustaining another injury, hospitalization and mortality (Xu and Drew 2018). In addition, quality of life among seniors post-injury may be greatly reduced through the development or worsening of mental health issues, fear of re-injury, social withdrawal, increased pain and frailty and decreased ability to live independently (Xu and Drew 2018).

Rates of police-reported violence among seniors highest in territories

Similar to police-reported crime in general (Moreau 2021), violence against seniors was highest in the territories in 2020 (Table 9). Meanwhile, in the provinces, police-reported violence against seniors was highest in New Brunswick (311 per 100,000 population) and lowest in Prince Edward Island (178). While the rate of physical assault in New Brunswick (173) was higher than other Atlantic provinces, it was similar to those reported in some other provinces.Note The higher rate of victimization observed in New Brunswick may be better explained by other offences involving actual or threatened violence (128 per 100,000 population), a rate that was double what was found in most other provinces.Note

Between 2010 and 2020, the rate of senior victimization increased in many provinces and territories; however, between 2015 and 2020,Note the rate increased in every province and territory, around the time when the senior population began to outnumber those aged 14 and younger for the first time in history (Statistics Canada 2019a). The largest rate increases between 2010 and 2020 were documented in New Brunswick (+54%), Ontario (+38%) and Prince Edward Island (+36%) (Table 9).

Moreover, victimization rates were higher for senior men than senior women in every province and territory in 2020. The largest gender differences were observed in Manitoba and the Northwest Territories, where the rate of reported violence was 1.8 times higher among men than women (329 versus 180 per 100,000 population in Manitoba and 4,258 versus 2,334 in the Northwest Territories).

Different trends were observed for non-seniors. While rates continue to be highest in the territories, among the provinces, the highest rates of police-reported violence among younger Canadians were documented in Saskatchewan (2,335 per 100,000 population) and Manitoba (2,222). Victimization rates were higher for younger women compared to men in every province and territory in 2020.

Provincial rates of police-reported violence among seniors higher in rural versus urban areas

In 2020, the overall rate of police-reported violence against seniors in the provinces was higher in rural areas compared to urban areas (247 versus 214 per 100,000 population) (Table 9).Note This pattern was similar for non-seniors, and for women and men—regardless of age group—though the urban-rural difference was larger for non-seniors. Aligned with this finding, rates of victimization for nearly all violation types were higher in rural compared to urban areas, for both senior men and women. The primary exception being robbery—the rate of robbery was four times higher in urban compared to rural areas (12 versus 3 per 100,000 population).Note

Between 2010 and 2020, similar rate increases for seniors were documented in both urban and rural areas (+22% and +21%, respectively). In urban areas, the rate increase was larger for senior men (+25%) than senior women (+19%). In rural areas, the rate increase was also higher for senior men (+25%) than senior women (+16%).

Meanwhile, for younger Canadians, the rate of police-reported violence declined in urban areas (-12%) and increased slightly in rural areas (+3%) between 2010 and 2020. In urban areas, there was a larger decline among non-senior men (-16%) compared to non-senior women (-8%). In rural areas, the rate remained stable for non-senior men (+0.1%) while it increased for non-senior women (+6%).

The rate of police-reported violence against seniors was lower in Canada’s largest cities—referred to as census metropolitan areas or CMAs—than it was in non-CMA areas (210 versus 253 per 100,000 population; Table 10).Note Of the CMAs, rates were highest in Brantford (493), Kitchener–Cambridge–Waterloo (390) and Lethbridge (344). Meanwhile, rates of senior victimization were lowest in Peterborough (113), Guelph (134), Trois-Rivières (138) and Thunder Bay (138).

Rates of senior victimization were higher among men compared to women in nearly all CMAs. The largest differences in victimization rates for senior men compared with senior women were noted in Saskatoon (291 versus 113, 2.6 times higher for senior men), Edmonton (262 versus 124, 2.1 times higher) and Trois-Rivières (192 versus 92, 2.1 times higher). The only CMAs where rates were higher among senior women compared to senior men were in Kitchener–Cambridge–Waterloo (410 versus 367), Brantford (542 versus 434) and Abbotsford–Mission (190 versus 186).

Start of text box 4

Text box 4

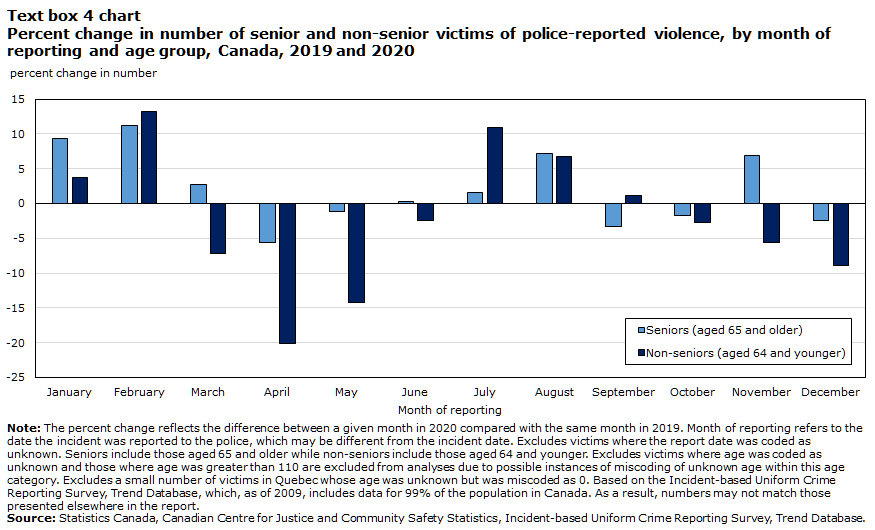

Police-reported violence against seniors during the COVID-19 pandemic

COVID-19 has caused significant disruptions and upheavals in daily activities worldwide. Although COVID-19 poses a risk for all age groups, seniors are at an increased risk of mortality and developing severe complications following infection (United Nations 2020). Those living in institutionalized settings are at particular risk. The pandemic exacerbated longstanding systemic issues within long-term care homes, leaving many seniors at increased risk of contracting the disease, all the while potentially experiencing instances of neglect, mistreatment and abuse (Marrocco et al. 2021).

Further, lockdown measures within communities and in long-term care facilities, which were designed to limit the spread of COVID, created additional challenges for seniors. Those living alone may have experienced a reduction in care or developed mental health problems due to isolation brought on by physical and social distancing (United Nations 2020). Meanwhile, others quarantined or locked down with family members or caregivers—who could also be experiencing higher levels of stress brought about by the pandemic—could also have experienced neglect and or other forms of abuse.

In order to determine whether or not restrictions placed on communities had an impact on the victimization of seniors, as reported to the police, month-to-month comparisons were drawn across 2019 and 2020 police-reported data. During the first two months of 2020, before lockdown measures were instituted, the number of senior victims of police-reported violence in Canada was about 10% greater than what was observed in January and February of 2019 (Text box 4 chart). Of note, over these two months, increases were also noted for victims under the age of 65, compared to the same months in 2019. However, following the implementation of lockdown measures, beginning in April, fewer instances of violence were being reported to the police compared to the same time in 2019 among Canadians, regardless of age. Sharper declines were observed in incidents involving victims under the age of 65 than was the case with seniors, despite both groups following similar patterns in general. It may be that lockdown measures had a stronger effect on curbing the activities of younger Canadians, activities which may otherwise have resulted in violent victimization.

Text box 4 chart start

Data table for Text box Chart 4

| Month of reporting | Seniors (aged 65 and older) | Non-seniors (aged 64 and younger) |

|---|---|---|

| percent change in number | ||

| January | 9.4 | 3.7 |

| February | 11.3 | 13.2 |

| March | 2.7 | -7.2 |

| April | -5.6 | -20.1 |

| May | -1.1 | -14.2 |

| June | 0.3 | -2.5 |

| July | 1.6 | 10.9 |

| August | 7.2 | 6.7 |

| September | -3.3 | 1.2 |

| October | -1.7 | -2.8 |

| November | 6.9 | -5.6 |

| December | -2.5 | -9.0 |

|

Note: The percent change reflects the difference between a given month in 2020 compared with the same month in 2019. Month of reporting refers to the date the incident was reported to the police, which may be different from the incident date. Excludes victims where the report date was coded as unknown. Seniors include those aged 65 and older while non-seniors include those aged 64 and younger. Excludes victims where age was coded as unknown and those where age was greater than 110 are excluded from analyses due to possible instances of miscoding of unknown age within this age category. Excludes a small number of victims in Quebec whose age was unknown but was miscoded as 0. Based on the Incident-based Uniform Crime Reporting Survey, Trend Database, which, as of 2009, includes data for 99% of the population in Canada. As a result, numbers may not match those presented elsewhere in the report. Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics, Incident-based Uniform Crime Reporting Survey, Trend Database. |

||

Text box 4 chart end

Presenting the month-to-month data in aggregate form conceals gender differences. Of note, a greater proportion of senior men were victimized in each month in 2020 (with the exception of December) compared to police-reported 2019 data. This finding was not observed for senior women, and non-senior men and women.

It is important to note that senior victimization often goes unreported. Relying on police-reported data alone may not capture the true scope of the issue. For example, one study conducted in the United States surveyed 897 residents nationwide and documented an 84% increase in senior abuse during the pandemic (Chang and Levy 2021).

End of text box 4

Section 4: Homicide of seniors

Existing homicide research often examines the prevalence and correlates of homicide among younger persons and cases involving select characteristics (e.g., firearms, intimate relationships and children). Research examining homicide among senior citizens, to contrast, has received much less attention despite the rapid growth of this population in recent years. Based on available data in the US, researchers have documented an increase in the homicide rate among people aged 50 and older since 2007 (Allen et al. 2020; Logan et al. 2019). A recent trend analysis, however, has not been explored in the Canadian context. This section uses pooled police-reported data from the Homicide Survey to examine characteristics of senior homicide victims that have been solved by the police from 2000 to 2020.

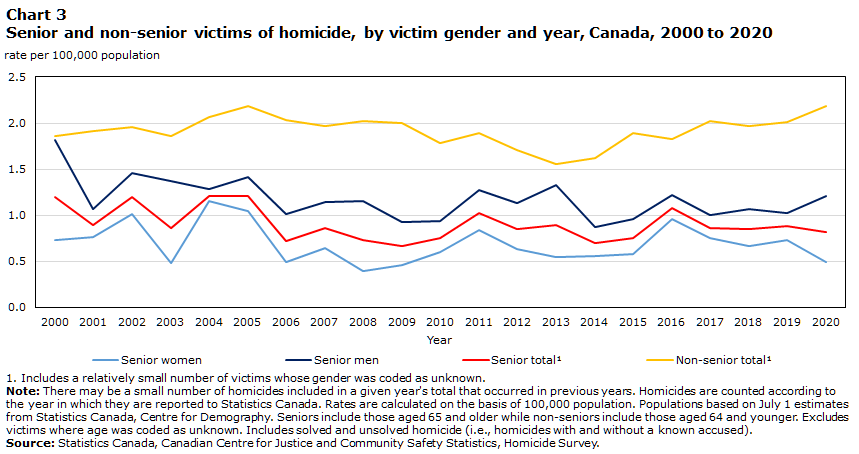

Increase in homicide rate among senior men since 2010, decrease for senior women

Between 2000 and 2020, 944 seniors have died by homicide in Canada, accounting for 7% of all homicide victims during this time. The large majority (88%) of homicides with senior victims were solved by police, meaning an accused person was identified, and this was more common among senior victims than non-senior victims (77%). Notwithstanding annual fluctuations, over this period, the homicide rate among seniors decreased (-31%) whereas the rate among non-seniors over the same period increased (+17%). However, the senior rate in 2000 was one of the highest in the time period analyzed and patterns change when a more recent reference year is used. For instance, since 2010, the homicide rate for those aged 65 and older increased (+9%) with a similar pattern noted since 2015 (+9%) (Chart 3). These rate increases were driven by the homicides of senior men which increased 28% since 2010. The homicide rate for senior women, in contrast, decreased 18% over the same period.

Chart 3 start

Data table for Chart 3

| Year | Senior women | Senior men | Senior totalData table for Chart 3 Note 1 | Non-senior totalData table for Chart 3 Note 1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| rate per 100,000 population | ||||

| 2000 | 0.7 | 1.8 | 1.2 | 1.9 |

| 2001 | 0.8 | 1.1 | 0.9 | 1.9 |

| 2002 | 1.0 | 1.5 | 1.2 | 2.0 |

| 2003 | 0.5 | 1.4 | 0.9 | 1.9 |

| 2004 | 1.1 | 1.3 | 1.2 | 2.1 |

| 2005 | 1.0 | 1.4 | 1.2 | 2.2 |

| 2006 | 0.5 | 1.0 | 0.7 | 2.0 |

| 2007 | 0.6 | 1.1 | 0.9 | 2.0 |

| 2008 | 0.4 | 1.2 | 0.7 | 2.0 |

| 2009 | 0.5 | 0.9 | 0.7 | 2.0 |

| 2010 | 0.6 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 1.8 |

| 2011 | 0.8 | 1.3 | 1.0 | 1.9 |

| 2012 | 0.6 | 1.1 | 0.9 | 1.7 |

| 2013 | 0.5 | 1.3 | 0.9 | 1.6 |

| 2014 | 0.6 | 0.9 | 0.7 | 1.6 |

| 2015 | 0.6 | 1.0 | 0.8 | 1.9 |

| 2016 | 1.0 | 1.2 | 1.1 | 1.8 |

| 2017 | 0.8 | 1.0 | 0.9 | 2.0 |

| 2018 | 0.7 | 1.1 | 0.8 | 2.0 |

| 2019 | 0.7 | 1.0 | 0.9 | 2.0 |

| 2020 | 0.5 | 1.2 | 0.8 | 2.2 |

Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics, Homicide Survey. |

||||

Chart 3 end

Two-thirds of senior men homicide victims killed by someone outside the family, two-thirds of senior women by an intimate partner or family member

Among victims of homicide that were solved, two-thirds (67%) of senior men were killed by a non-family member, most commonly a friend (30%) followed by a stranger (20%) or an acquaintance (17%) (Table 11). That said, about one in four (27%) senior men were killed by a family member, often their children (20%). In contrast, among senior women who were victims of homicide, two-thirds (67%) were killed by an intimate partner (32%) or a family member (35%). Within these relationships, accused persons were often a spouse or child of the victim. Nearly one in eight (13%) senior women were killed by a stranger.

Aligned with the relationships between accused persons and victims, the large majority (84%) of seniors were killed inside a residential location.Note This figure exceeded what was documented among non-seniors (59%).

Both senior men and women were most often killed by beating or blows (39% and 32%, respectively) or by stabbing (33% and 24%, respectively). These findings contrast with non-senior homicide victims, where men and boys were most often shot (39%) and women and girls were most often stabbed (32%).

Summary

According to the General Social Survey on Canadians’ Safety (Victimization), there were about 128,000 senior victims of violence—including physical assault, sexual assault and robbery—in Canada in 2019. Rates of self-reported victimization were five times lower among seniors compared to non-seniors (20 versus 100 incidents per 1,000 population). When victimization did occur, most seniors reported being physically assaulted, a finding that aligned with police-reported data.

Seniors’ overall lower experiences of victimization, relative to younger Canadians, may be tied to their perceptions of safety. Seniors reported high levels of satisfaction with their personal safety from crime, proportions which were much greater than younger Canadians. In addition, seniors perceived crime in their neighbourhood to be lower than other areas in Canada, felt a somewhat or very strong sense of community belonging, and perceived police as performing well across all measures.

There was a 22% increase in police-reported violent crime against seniors between 2010 and 2020. Rates were higher among senior men compared to senior women, in the territories compared to the provinces, and in provincial rural areas compared to urban areas. The overall low rates of victimization could, however, be impacted by underreporting. Seniors may not report their victimization to police due to privacy concerns, having a dependency on the abuser, fear of retaliation or institutionalization, and an inability to report due to cognitive or physical declines.

Almost two-thirds (64%) of police-reported violent crime against seniors was perpetrated by non-family members. The largest proportion of senior men were victimized by non-family members, specifically, acquaintances and strangers. Senior women were most often victimized by acquaintances, and equal proportions were victimized by a stranger or an intimate partner.

More than half (60%) of all police-reported violence against seniors involved the use or threat of physical force, an additional 19% involved the presence of a weapon. Just over one in three (35%) seniors suffered a physical injury as a result of the incident.

The homicide rate among senior victims has increased since 2010 (+9%), driven largely by the homicide of senior men (+28%). Similar to non-fatal victimization, two-thirds (67%) of senior men who were victims of homicide were killed by a member, while two-thirds (67%) of senior women were killed by an intimate partner or a family member.

Detailed data tables

Table 1 Senior and non-senior violent victimization, by age group and gender, Canada, 2019

Table 4 Senior and non-senior perceptions of police, by age group and gender, Canada, 2019

Survey description

General Social Survey on Canadians’ Safety (Victimization)

This article uses data from the General Social Survey (GSS) on Canadians’ Safety (Victimization). In 2019, Statistics Canada conducted the GSS on Victimization for the seventh time. Previous cycles were conducted in 1988, 1993, 1999, 2004, 2009 and 2014. The main objective of the GSS on Victimization is to better understand issues related to the safety and security of Canadians, including perceptions of crime and the justice system, experiences of intimate partner violence, and how safe people feel in their communities.

The target population was persons aged 15 and older living in the provinces and territories, except for those living full-time in institutions.

Data collection took place between April 2019 and March 2020. Responses were obtained by computer-assisted telephone interviews, in-person interviews (in the territories only) and, for the first time, the GSS on Victimization offered a self-administered internet collection option to survey respondents in the provinces and in the territorial capitals. Respondents were able to respond in the official language of their choice.

An individual aged 15 or older was selected within each sampled household to respond to the survey. An oversample of Indigenous people was added to the 2019 GSS on Victimization to allow for a more detailed analysis of individuals belonging to this population group. In 2019, the final sample size was 22,412 respondents.

In 2019, the overall response rate was 37.6%. Non-respondents included people who refused to participate, could not be reached, or could not speak English or French. Respondents in the sample were weighted so that their responses represent the non-institutionalized Canadian population aged 15 and older.

For the quality of estimates, the lower and upper bounds of the confidence intervals are presented in charts and tables. Confidence intervals should be interpreted as follows: if the survey were repeated many times, then 95% of the time (or 19 times out of 20), the confidence interval would cover the true population value.

Incident-based Uniform Crime Reporting Survey

The Incident-based Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR) Survey collects detailed information on criminal incidents that have come to the attention of police services in Canada. Information includes characteristics of victims, accused persons and incidents. In 2020, data from police services covered 99% of the population of Canada.

One incident can involve multiple offences. In order to ensure comparability, counts are presented based on the most serious offence related to the incident as determined by a standard classification rule used by all police services.

Victim age is calculated based on the end date of an incident, as reported by the police. Some victims experience violence over a period of time, sometimes years, all of which may be considered by the police to be part of one continuous incident. Information about the number and dates of individual incidents for these victims of continuous violence is not available. Excludes victims where age was greater than 110 due to possible instances of miscoding of unknown age within this age category.

Given that small counts of victims and accused persons identified as “gender diverse” may exist, the UCR data available to the public has been recoded to assign these counts to either “female” or “male” in order to ensure the protection of confidentiality and privacy. Victims and accused persons identified as gender diverse have been assigned to either female or male based on the regional distribution of victims’ and accused persons’ gender.

Homicide Survey

The Homicide Survey collects detailed information on all homicide that has come to the attention of, and have been substantiated by, police services in Canada. Information includes characteristics of victims, accused persons and incidents. In 2019, the survey went through a comprehensive redesign in order to improve data quality and enhance relevance.

Prior to 2019, Homicide Survey data was presented by the sex of the victims. Sex and gender refer to two different concepts. Caution should be exercised when comparing counts for sex with those for gender. Given that small counts of victims identified as “gender diverse” may exist, the aggregate Homicide Survey data available to the public has been recoded to assign these counts to either “male” or “female” in order to ensure the protection of confidentiality and privacy.

References

Addington, L. A. 2012. “Who you calling old? Measuring ‘elderly’ and what it means for homicide research.” Homicide Studies. Vol. 17, no. 2.

Advocacy Centre for the Elderly (ACE). 2013. Elder abuse – Introduction.

Allen, T., Salari, S. and G. Buckner. 2020. “Homicide illustrated across the ages: Graphic descriptions of victim and offender age, sex, and relationship.” Journal of Aging and Health. Vol. 32, no. 3-4.

Arriagada, P. 2020. “The experiences and needs of older caregivers in Canada.” Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 75-006-X.

Bows, H. 2019. “Domestic homicide of older people (2010-15): A comparative analysis of intimate-partner homicide and parricide cases in the UK.” British Journal of Social Work. Vol. 49.

Brijnath, B., Gartoulla, P., Joosten, M., Feldman, P., Temple, J. and B. Dow. 2021. “A 7-year trend analysis of the types, characteristics, risk factors, and outcomes of elder abuse in community settings.” Journal of Elder Abuse & Neglect. Vol. 33, no. 4.

Burczycka, M. 2016. “Trends in self-reported spousal violence in Canada, 2014.” In Family violence in Canada: A statistical profile, 2014. Juristat. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 85-002-X.

Canadian Institute for Health Information. 2021. Dementia in home and community care.

Chang E. and B. R. Levy. 2021. “High prevalence of elder abuse during the COVID-19 pandemic: Risk and resilience factors.” American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. Vol. 29, no. 11.

Conroy, S. 2021. “Family violence in Canada: A statistical profile, 2019.” Juristat. Statistics Canada catalogue no. 85-002-X.

Cotter, A. 2021a. “Criminal victimization in Canada, 2019.” Juristat. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 85-002-X.

Cotter, A. 2021b. “Intimate partner violence in Canada, 2018: An overview.” Juristat. Statistics Canada catalogue no. 85-002-X.

Department of Justice. 2019. Just facts: Sexual assault.

Department of Justice. 2015. Legal definitions of elder abuse and neglect.

Dowling, C., Morgan, A., Boyd, C. and I. Voce. 2018. “Policing domestic violence: A review of the evidence.” Australian Institute of Criminology.

Evenson, K. R., Rosamond, W. D., Cai, J., Diez-Roux, A. V. and F. L. Brancati. 2002. “Influence of retirement on leisure-time physical activity: The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study.” American Journal of Epidemiology. Vol. 155, no. 8.

Gabor, T. and J. Kiedowski. 2009. Crime and abuse against seniors: A review of the research literature with special reference to the Canadian situation. Government of Canada.

Gilmour, H. and P. L. Ramage-Morin. 2020. “Social isolation and mortality among Canadian seniors.” Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 82-003-X.

Government of Canada. 2017. Facts on psychological and emotional abuse of seniors.

Greve, W., Leipold B. and C. Kappes. 2018. “Fear of crime in old age: A sample case of resilience?” The Journals of Gerontology: Series B. Vol. 73, no. 7.

Hale, C. 1996. “Fear of crime: A review of the literature.” International Review of Victimology. Vol. 4, no. 2.

Hanslmaier, M., Peter, A. and B. Kaiser. 2018. “Vulnerability and fear of crime among elderly citizens: What role do neighbourhood and health play?” Journal of Housing and the Built Environment. Vol. 33.

Henderson, C. R., Caccamise, P., Soares, J. J. F., Stankunas, M. and J. Lindert. 2021. “Elder maltreatment in Europe and the United States: A transnational analysis of prevalence rates and regional factors.” Journal of Elder Abuse & Neglect. Vol. 33, no. 4.

Henning, G., Stenling, A., Bielak, A. A .M., Bjälkebring, P., Gow, A. J., Kivi, M., Muniz-Terrera, G., Johansson, B. and M. Lindwall. 2020. “Towards an active and happy retirement? Changes in leisure activity and depressive symptoms during the retirement transition.” Aging & Mental Health. Vol. 25, no. 4.

Lachs, M. S., Teresi, J. A., Ramirez, M., van Haitsma, K., Silver, S., Eimicke, J. P., Boratgis, G., Sukha, G., Kong, J., Besas, A. M., Luna, M. R. and K. A. Pillemer. 2016. “The prevalence of resident-to-resident elder mistreatment in nursing homes.” Annals of Internal Medicine. Vol. 165.

Lee, Y., Chi, I. and J.A. Ailshire. 2020. “Life transitions and leisure activity engagement among older Americans: Findings from a national longitudinal study.” Aging & Society. Vol. 40.

Logan, J. E., Haileyesus, T., Ertl, A., Rostad, W. L. and J. H. Herbst. 2019. “Nonfatal assaults and homicides among adults aged ≥ 60 Years — United States, 2002-2016.” CDC Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Vol. 68, no. 13.

MacDonald, L. 2018. “The mistreatment of older Canadians: Findings from the 2015 national prevalence study.” Journal of Elder Abuse & Neglect. Vol. 30, no. 3.

Marrocco, F. N., Coke, A. and J. Kitts. 2021. Ontario’s long-term care COVID-19 commission: Final report.

Michalski, C. A., Diemert, L. M., Helliwell, J. F., Goel, V. and L. C. Rosella. 2020. “Relationship between sense of community belonging and self-rated health across life stages.” SSM – Population Health. Vol. 12.

Miszkurka, M., Steensma, C. and S. P. Phillips. 2016. “Correlates of partner and family violence among older Canadians: A life-course approach.” Health Promotion and Chronic Disease Prevention in Canada. Vol. 36, no. 3.

Moreau, G. 2021. “Police-reported crime statistics in Canada, 2020.” Juristat. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 85-002-X.

Moreau, G., Jaffray, B. and A. Armstrong. 2020. “Police-reported crime statistics in Canada, 2019.” Juristat. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 85-002-X.

Pillemer, K., Burnes, D., Riffin, C. and M. Lachs. 2016. “Elder abuse: Global situation, risk factors, and prevention strategies.” The Gerontologist. Vol. 56.

Policastro, C. and M. A. Finn. 2017. “Coercive control and physical violence in older adults: Analysis using data from the National Elder Mistreatment Study.” Journal of Interpersonal Violence. Vol. 32, no. 3.

Preston, J. and J. Wahl. 2002. “Abuse education, prevention and response: A community training manual for those who want to address the issue of the abuse of older adults in their community.” Advocacy Centre for the Elderly.

Public Health Agency of Canada. 2020. Aging and chronic diseases: A profile of Canadian seniors.

Puxty, J., Rosenberg, M. W., Carver, L. and B. Crow. 2019. “Report on housing needs of seniors.” Employment and Social Development Canada.

Roger, K., Walsh, C. A., Goodridge, D., Miller, S., Cewick, M. and C. Liepert. 2021. “Under reporting of abuse of older adults in the Canadian prairie provinces.” Sage Open.

Rosay, A. B. and C. F. Mulford. 2017. “Prevalence estimates and correlates of elder abuse in the United States: The National Intimate Partner Sexual Violence Survey.” Journal of Elder Abuse & Neglect. Vol. 29, no. 1.

Royal Commission. 2020. “Experimental estimates of the prevalence of elder abuse in Australian aged care facilities.” Research Paper.

Savage, L. 2021. “Intimate partner violence: Experiences of young women in Canada, 2018.” Juristat. Statistics Canada catalogue no. 85-002-X.

Sheppard, C. L., Gould, S., Austen, A. and S. L. Hitzig. 2021. “Perceptions of risk: Perspectives on crime and safety in public housing of older adults.” The Gerontologist.

Srugo, S. A., Jiang, Y. and M. de Groh. 2020. “At-a-glance – Living arrangements and health status of seniors in the 2018 Canadian Community Health Survey.” Health Promotion and Chronic Disease Prevention in Canada. Vol. 40, no. 1.

Statistics Canada. 2022. “Census in brief: A generational portrait of Canada’s aging population from the 2021 Census.” Catalogue no. 98-200-X, issue 2021003.

Statistics Canada. 2021. Table 17-10-0005-01 – Population estimates on July 1st, by age and sex.

Statistics Canada. 2019a. “Population projections of Canada (2018 to 2068), provinces and territories (2018 to 2043).” Catalogue no. 91-520-X.

Statistics Canada. 2019b. Table 17-10-0057-01 – Projected population, by projection scenario, age and sex, as of July 1 (x 1,000).

United Nations. 2020. The impact of COVID-19 on older persons. Policy Brief.

Walsh, C. A., Olson, J. L., Ploeg, J., Lohfeld, L. and H. L. MacMillan. 2011. “Elder abuse and oppression: Voices of marginalized elders.” Journal of Elder Abuse & Neglect. Vol. 23.

Weissberger, G. H., Goodman, M. C., Mosqueda, L., Schoen, J., Nguyen, A. L., Wilber, K. H., Gassoumis, Z. D., Nguyen, C. P. and S. D. Han. 2020. “Elder abuse characteristics based on calls to the National Center on Elder Abuse resource line.” Journal of Applied Gerontology. Vol. 39, no. 10.

The World Bank. 2022. Population aged 65 and above (% of total population).

World Health Organization. 2021. Elder abuse.

Xu, D. and J. A. R. Drew. 2018. “What doesn’t kill you doesn’t make you stronger: The long-term consequences of nonfatal injury for older adults.” The Gerontologist. Vol. 58, no. 4.

Yin, P. P. 1980. “Fear of crime among the elderly: Some issues and suggestions.” Social Problems. Vol. 27, no. 4.

Yon, Y., Ramiro-Gonzalez, M., Mikton, C., Huber, M. and D. Sethi. 2018. “The prevalence of elder abuse in institutional settings: A systematic review and meta-analysis.” European Journal of Public Health. Vol. 29, no. 1.

Yon, Y., Mikton, C. R., Gassoumis, Z. D. and K. H. Wilber. 2017. “Elder abuse prevalence in community settings: A systematic review and meta-analysis.” Lancet Global Health. Vol. 5.

Yunus, R. M., Hairi, N. N. and W.Y. Choo. 2019. “Consequences of elder abuse and neglect: A systematic review of observational studies.” Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. Vol. 20, no. 2.

- Date modified: