Violent victimization and perceptions of safety: Experiences of First Nations, Métis and Inuit women in Canada

by Loanna Heidinger, Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics

Highlights

- Violence against Indigenous peoples reflects the traumatic and destructive history of colonialization that impacted and continues to impact Indigenous families, communities and Canadian society overall.

- Violent victimization is defined in the 2018 Survey of Safety in Public and Private Spaces (SSPPS), as a physical assault (an attack, a threat of physical harm, or an incident with a weapon present) or a sexual assault (forced sexual activity or attempted forced sexual activity).

- Results from the SSPPS indicate that more than six in ten (63%) Indigenous women have experienced physical or sexual assault in their lifetime.

- Almost six in ten (56%) Indigenous women have experienced physical assault while almost half (46%) of Indigenous women have experienced sexual assault. In comparison, about a third of non-Indigenous women have experienced physical assault (34%) or sexual assault (33%) in their lifetime.

- About two-thirds of First Nations (64%) and Métis (65%) women have experienced violent victimization in their lifetime.

- Certain characteristics were associated with a higher likelihood of experiencing lifetime violent victimization among Indigenous women, including having a disability or ever experiencing homelessness.

- Indigenous women (11%) were almost six times more likely than non-Indigenous women (2.3%) to have ever been under the legal responsibility of the government and about eight in ten (81%) Indigenous women who were ever under the legal responsibility of the government have experienced lifetime violent victimization.

- Indigenous women (42%) were more likely than non-Indigenous women (27%) to have been physically or sexually abused by an adult during childhood and to have experienced harsh parenting by a parent or guardian. These childhood experiences were associated with an increased prevalence of lifetime violent victimization.

- Results from the 2019 General Social Survey (GSS) on Canadians’ Safety (Victimization) indicated that Indigenous women (71%) were more likely to perceive indicators of social disorder in their neighbourhood compared with non-Indigenous women (57%).

- Indigenous women (17%) were more than twice as likely to report having not very much or no confidence in the police compared with non-Indigenous women (8.2%).

First Nations, Métis and Inuit (Indigenous) peoples are diverse and have unique histories, languages, cultural practices and spiritual beliefs. Indigenous peoples are overrepresented as victimsNote of violence in Canada. The disproportionately high rates of violence and victimization of Indigenous peoples is rooted in the traumatic and destructive history of colonialization that impacted and continues to impact Indigenous families, communities and Canadian society overall (Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada 2015). Indigenous peoples were subjected to racist and oppressive laws and regulations that suppressed language and religion, destroyed culture, and dismantled Indigenous families and communities (Sharma et al. 2021). Across multiple generations, Indigenous peoples were and continue to be subjected to the detrimental harms of colonialism.

Indigenous women, in particular, have faced and continue to face high rates of violence, as reflected by the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls 2019). In order to understand the disproportionate experience of violence among Indigenous women, it is important to highlight the damaging history of colonialization which shifted the role of Indigenous women in the household and in Indigenous communities (Sharma et al. 2021). Prior to colonialization, women held a significant place in Indigenous societies. Indigenous women were highly valued individuals holding positions of leadership and decision making power. However, colonialization forcibly altered traditional matrilineal views while contributing to the normalization of violence against Indigenous women. In particular, policies such as the Indian Act denied Indigenous women of many rights and excluded Indigenous women from community governance (Sharma et al. 2021).

Experiences of violent victimization are concerning and have a profound impact on outcomes such as social, economic, and emotional well-being; however, a large proportion of violent crime is not reported to authorities, such as the police (Cotter 2021b; Perreault 2015). For Indigenous women, the issue of reporting is complex and may be largely impacted by the mistrust in police and criminal justice systems. In particular, a history of colonialization and ongoing structural and systemic realities negatively impacted relations between Indigenous women and authorities in Canada (Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada 2015). In addition, Indigenous women may face unique barriers to reporting experiences of violent victimization or seeking help following victimization, including a lack of access to culturally appropriate resources, inaccessibility of support services, a general distrust of law enforcement, and perceived lack of confidentiality in the justice system (Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada 2015).

This Juristat article will present the most current self-reported data on the lifetime (since age 15)Note prevalence of violent victimization, as well as the prevalence of violent victimization in the past 12 months, of IndigenousNote womenNote in Canada. Where possible, results are provided separately for First Nations, Métis and Inuit Indigenous identity groups. The article further highlights experiences of childhood abuse and maltreatment, and explores the intersectionality of violent victimization with other demographic and socioeconomic factors. In addition, the article assesses perceptions of safety and neighbourhood disorder, and confidence and trust in the police and the justice system among Indigenous women. Lastly, homicide data highlights the prevalence and characteristics among homicide of Indigenous women in Canada. The article uses data from multiple sources including the 2018 Survey of Safety in Public and Private Spaces (SSPPS), 2019 General Social Survey (GSS) on Canadians’ Safety (Victimization), and five years (2015 to 2020) of data from the Homicide Survey.

Start of Text Box 1

Text box 1

Defining and measuring violent victimization

The Survey of Safety in Public and Private Spaces (SSPPS) collected information on Canadians’ experiences of lifetime violent victimization (violent victimization since age 15) and experiences of violent victimization in the 12 months that preceded the survey. Total violent victimization includes experiences of physical or sexual violence perpetrated by either intimate partners or those other than intimate partners (non-intimate partners), such as acquaintances, friends, family members, coworkers and others. Experiences of physical and sexual victimization are self-reported, providing a more inclusive approach to measuring violent victimization than estimates that focus solely on victimization reported to police.

The “dark figure of crime” are crimes that are not reported to, or recorded by, police and comprise the majority of criminal incidents, such as intimate partner violence and sexual assault, where only a small proportion are reported to authorities. Since many instances of violent victimization are not reported to police or other authorities, relying on police-reported violent victimization data may skew the understanding of violent victimization and estimates may not be representative of victimization in Canada. The SSPPS focuses on self-reported instances of violent victimization, and as such intends to increase knowledge and understanding of gender-based violence beyond police-reported estimates. It was developed as part of the Federal Government of Canada’s strategy (It’s Time: Canada’s Strategy to Prevent and Address Gender-Based Violence) to prevent and address gender-based violence in Canada and provides a more comprehensive estimate of violent victimization in Canada.

In the SSPPS violent victimization is defined as:

Physical assault: An attack (being hit, slapped, grabbed, pushed, knocked down, or beaten), a threat of physical harm, or an incident with a weapon present; and

Sexual assault: Forced sexual activity, attempted forced sexual activity, unwanted sexual touching, grabbing, kissing or fondling, or sexual relations without being able to give consent.

End of text box 1

More than six in ten Indigenous women experience violence in their lifetime

According to the SSPPS, lifetime violent victimization includes any experience of physical or sexual assault or any threat of physical or sexual assault experienced since age 15. Experiences of physical or sexual assault can have lasting detrimental implications for victims, their families, their communities, and society as a whole.

Indigenous women are overrepresented as victims of various types of violence (Brownridge et al. 2017; Burczycka 2016; Heidinger 2021). Generations of Indigenous peoples continue to be impacted by the negative consequences of colonialization and related policies that resulted in violence and trauma that continues to be perpetuated across multiple generations (National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls 2019). Results from the SSPPS confirms that Indigenous women are overrepresented in lifetime experiences of violent victimization. More than six in ten (63%) Indigenous women have experienced physical or sexual violence committed by an intimate partner or a non-intimate partner in their lifetime, such as an acquaintance, colleague or stranger. In comparison, the prevalence of lifetime violence was lower among non-Indigenous women (45%; Table 1A; Chart 1A).Note

Chart 1A start

Data table for Chart 1A

| Physical assault | Sexual assault | Total violent victimization | |

|---|---|---|---|

| percent | |||

| Indigenous women | |||

| Intimate partnerData table for chart 1A Note 1 | 41.7Note * | 21.2Note * | 43.7Note * |

| Non-Intimate partnerData table for chart 1A Note 2 | 42.7Note * | 43.2Note * | 54.9Note * |

| Total | 55.5Note * | 46.2Note * | 62.7Note * |

| Non-Indigenous womenData table for chart 1A Note † | |||

| Intimate partnerData table for chart 1A Note 1 | 22.3 | 11.1 | 25.1 |

| Non-Intimate partnerData table for chart 1A Note 2 | 25.6 | 29.9 | 38.2 |

| Total | 34.3 | 32.9 | 44.7 |

Source: Statistics Canada, Survey of Safety in Public and Private Spaces. |

|||

Chart 1A end

Almost six in ten (56%) Indigenous women have experienced physical assault while almost half (46%) of Indigenous women have experienced sexual assault in their lifetime. In comparison, about a third of non-Indigenous women have experienced physical assault (34%) or sexual assault (33%) in their lifetime. When asked about violence experienced in the previous year, Indigenous women were almost twice as likely to have experienced physical assault (6.2% versus 3.5% among non-Indigenous women; Table 2A; for results by Indigenous identity group see Table 2B).

Two-thirds of First Nations and Métis women experience physical or sexual assault in their lifetime

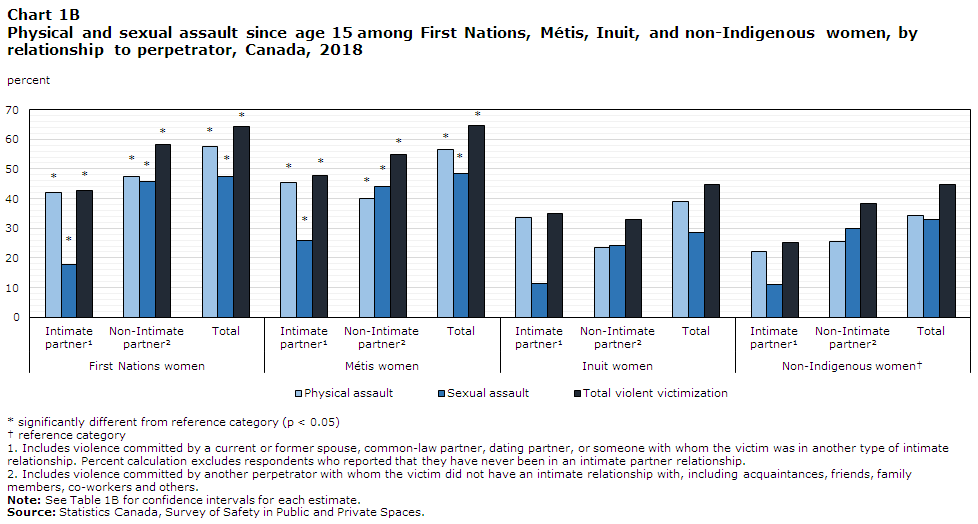

When looking at victimization by Indigenous identity group, about two-thirds of First Nations (64%) and Métis (65%) women have experienced violent victimization, physical or sexual assault, in their lifetime (Table 1B; Chart 1B). Of note, differences between reported experiences of violent victimization among Inuit (45%) versus non-Indigenous (45%) women were not statistically significant. Some studies suggest that a history of trauma and violence stemming from colonialization and related policies have contributed to the intergenerational violence that place Inuit women at a greater risk of growing up in abusive households where violence becomes a normalized part of interpersonal relationships and may be expected or perceived as acceptable (Brassard et al. 2015; National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls 2019; Pauktuutit Inuit Women of Canada and Comack 2020; Perreault 2020; Williams 2019).This normalization of violence may contribute to the decreased likelihood of viewing oneself as a victim of violence and the overall underreporting of violence among Inuit women (Gone 2013; Pauktuutit Inuit Women of Canada and Comack 2020), which may explain similar reported victimization rates among Inuit and non-Indigenous women.

Chart 1B start

Data table for Chart 1B

| First Nations women | Physical assault | Sexual assault | Total violent victimization |

|---|---|---|---|

| percent | |||

| Intimate partnerData table for chart 1B Note 1 | 42.0Note * | 17.7Note * | 42.7Note * |

| Non-Intimate partnerData table for chart 1B Note 2 | 47.6Note * | 45.7Note * | 58.1Note * |

| Total | 57.6Note * | 47.5Note * | 64.4Note * |

| Métis women | |||

| Intimate partnerData table for chart 1B Note 1 | 45.5Note * | 25.8Note * | 47.7Note * |

| Non-Intimate partnerData table for chart 1B Note 2 | 40.1Note * | 44.0Note * | 54.9Note * |

| Total | 56.6Note * | 48.4Note * | 64.8Note * |

| Inuit women | |||

| Intimate partnerData table for chart 1B Note 1 | 33.6Note * | 11.3Note * | 35.0Note * |

| Non-Intimate partnerData table for chart 1B Note 2 | 23.4Note * | 24.1Note * | 33.0Note * |

| Total | 39.0Note * | 28.4Note * | 44.8Note * |

| Non-Indigenous womenData table for chart 1B Note † | |||

| Intimate partnerData table for chart 1B Note 1 | 22.3 | 11.1 | 25.1 |

| Non-Intimate partnerData table for chart 1B Note 2 | 25.6 | 29.9 | 38.2 |

| Total | 34.3 | 32.9 | 44.7 |

Source: Statistics Canada, Survey of Safety in Public and Private Spaces. |

|||

Chart 1B end

Across all provinces, violent victimization was higher among Indigenous women

In each of the Canadian provinces and regions outside of the territories, Indigenous women were more likely than non-Indigenous women to have experienced violent victimization in their lifetime. This was the case for Indigenous women in the Atlantic provinces (64% versus 45% of non-Indigenous women in Atlantic provinces), Central Canada (62% versus 43%), the Prairies (61% versus 48%), and British Columbia (65% versus 50%). In the territories there was no significant difference in the reported prevalence of lifetime violent victimization between Indigenous (62%) and non-Indigenous women (61%; Table 3).Note

Start of Text Box 2

Text box 2

Intimate partner and non-intimate partner violence

The Survey of Safety in Public and Private Spaces (SSPPS) differentiates between experiences of intimate partner violence (IPV) and non-intimate partner violence—violence by another perpetrator that occurs in other contexts outside of intimate partner relationships. Although IPV and non-intimate partner violence are often combined to estimate a total prevalence of criminal victimization, this text box presents results for intimate and non-intimate partner violence separately due to differences in the context and nature of these experiences.

Intimate partner violence

IPV is a serious public health issue that has profound impacts on victims, families, and communities (World Health Organization 2017). IPV encompasses a broad range of behaviours, such as physical and sexual assault, as well as emotional, psychological and financial abuse; however, only a small proportion of IPV is reported to authorities. In addition to the negative consequences victims of IPV experience, such as post-traumatic stress disorder, financial hardship, injury and profound emotional distress, IPV further contributes to the cycle of intergenerational violence (Public Health Agency of Canada 2020).

Overall, both men and women experience IPV; however, women are overrepresented as victims of police-reported IPV (Conroy 2021) and are more likely to experience more severe types of IPV (Cotter 2021a; Women and Gender Equality Canada 2021). In addition, women victims of homicide are more likely to have been killed by an intimate partner than by any other perpetrator. The overall risk of victimization is heightened among Indigenous women who experience higher rates of IPV than non-Indigenous women (Boyce 2016; Heidinger 2021; Perreault 2015).

The SSPPS defines an intimate partner as a current or former spouse, common-law partner or dating partner and measures IPV using 27 broad items (for a complete list of items included in measures of IPV see Table 4). In line with total experiences of violent victimization, the range of abusive behaviours include indicators of physical and sexual violence. In addition, psychological abuse, including emotional and financial abuse, are included in measures of IPV.

More than four in ten Indigenous women experience physical or sexual assault by an intimate partner

According to the SSPPS, Indigenous women were more likely than non-Indigenous women to experience IPVNote in their lifetime—that is, violence committed by a current or former legally married or common-law spouse, dating partner, or other intimate partner. More than four in ten (44%) Indigenous women have experienced physical or sexual violence by an intimate partner in their lifetime. In comparison, one-quarter (25%) of non-Indigenous women have experienced physical or sexual assault by an intimate partner in their lifetime, significantly less than Indigenous women (Table 1A; Chart 1A).

When looking at IPV by Indigenous identity group, four in ten (43%) First Nations women and almost half (48%) of Métis women have experienced physical or sexual violence by an intimate partner in their lifetime. More than a third (35%) of Inuit women have experienced physical or sexual IPV in the same time frame, though this proportion was not statistically different from that of non-Indigenous women (25%; Table 1B; Chart 1B).

In addition to being more likely to experience physical or sexual violence by an intimate partner, Indigenous women also disproportionately experienced multiple specific physical and sexual abusive behaviours by an intimate partner compared with non-Indigenous women. These physical and sexual abusive behaviours are often considered some of the most severe types of abuse and Indigenous women were overrepresented in all of them.

For example, Indigenous women were about two times more likely to have been: shook, pushed, grabbed or thrown (32% versus 17% of non-Indigenous women) or hit with a fist or object, or kicked or bit (26% versus 11%) by an intimate partner. Indigenous women were about three times more likely to have been: threatened with a weapon (13% versus 3.6% of non-Indigenous women); choked (17% versus 6.1%); or beat (16% versus 5.7%) by an intimate partner. Furthermore, Indigenous women were twice as likely to have had an intimate partner who: made them perform sex acts that they did not want to perform (17% versus 8.2% of non-Indigenous women) or forced or tried to force them to have sex (19% versus 9.5%; Table 4).

Overall, six in ten Indigenous women experience psychological abuse by an intimate partner in their lifetime

While physical and sexual assault are often considered the most severe types of violence, other forms of abuse exist in intimate partner relationships. Psychological abuse is characterized by behaviours that are intended to control, isolate, manipulate or humiliate victims. This type of abuse can have detrimental and long lasting consequences on victims that continue long after contact with an abuser ends (Karakurt et al. 2014).

Though it may be considered a less overt form of IPV, experiences of psychological abuse was the most common type of IPV experienced among women overall. However, as with physical and sexual violence, Indigenous women (60%) were more likely to have experienced psychological abuse by an intimate partner in their lifetime (Table 4). In particular, significantly higher proportions of First Nations (57%) and Métis (63%) women have experienced psychological abuse by an intimate partner compared with non-Indigenous women (42%).

Furthermore, Indigenous women were overrepresented in several specific types of psychologically abusive behaviours by an intimate partner. Indigenous women were more likely to have had an intimate partner who: was jealous and didn’t want them to talk to other men or women (46% versus 29% of non-Indigenous women); put them down or called them names to make them feel bad (50% versus 31%); or told them they were crazy, stupid, or not good enough (44% versus 26%).

Notably, lifetime experiences of financial abuse by an intimate partner was significantly more prevalent among Indigenous women. More specifically, Indigenous women were almost three times more likely than non-Indigenous women to have been forced to give their partner money or possessions (16% versus 6.0% of non-Indigenous women), or to have been kept from having access to a job, money, or financial resources by their partner (13% versus 4.8%; Table 4).

Financial cost is a known barrier to leaving an abusive partner. Experiences of financial abuse can create an economic dependency that may increase the difficulty of leaving an abusive relationship. The lack of access to financial resources or the lack of control over finances in abusive relationships may further trap victims to abusive partners (Postmus et al. 2020), in particular for Indigenous women who experience higher rates of poverty and marginalization (Truth and Reconciliation report 2015).

Indigenous women more likely to experience fear, anxiety and feelings of being controlled or trapped by an intimate partner

Results from the SSPPS indicate that Indigenous women are more likely to experience IPV compared with non-Indigenous women. In addition, measures of emotional and psychological impacts of IPV can provide additional context to experiences of abuse. Being afraid of a partner can indicate the severity of IPV and may reveal a pattern of repeated abuse that is more coercive and controlling in nature (Johnson and Leone 2005).

Indigenous women were more likely to experience emotional and psychological impacts of IPV. Just over half (52%) of Indigenous women who had experienced IPV were ever afraid of an intimate partner and almost six in ten (56%) Indigenous women who had experienced IPV ever felt controlled or trapped by an abusive partner. In comparison, among non-Indigenous women who had experienced IPV, more than one-third (36%) were ever afraid of an intimate partner and about four in ten (42%) ever felt controlled or trapped by an abusive partner. Similar proportions of Indigenous women (62%) and non-Indigenous women (57%) who had experienced IPV were ever anxious or on edge due to a partners abusive behaviours.

Consequences and actions following IPV similar for Indigenous and non-Indigenous women

In addition to the emotional and psychological impacts of IPV, the SSPPS measured consequences and actions taken by women who were victims of IPV in the 12 months preceding the survey. Overall, there were no significant differences in self-reported outcomes or actions among Indigenous women compared with non-Indigenous women (Chart 2).

Chart 2 start

Data table for Chart 2

| Impact | Indigenous women | Non-Indigenous womenData table for chart 2 Note † | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| percent | standard error | percent | standard error | |

| Incident had an emotional impact | 94 | 3.6 | 92 | 1.0 |

| Spoke with someone | 70 | 7.1 | 68 | 1.7 |

| Victim was injuredData table for chart 2 Note 1 | 19 | 8.1 | 20 | 2.7 |

| Separated due to violence | 30 | 6.5 | 17 | 1.6 |

| Symptoms consistent with PTSD | 25 | 0.7 | 12 | 1.3 |

| Used or contacted a service | 12 | 4.5 | 13 | 1.4 |

| Victim lost consciousness | Note F: too unreliable to be published | Note ...: not applicable | 3 | 1.1 |

|

... not applicable F too unreliable to be published

Source: Statistics Canada, Survey of Safety in Public and Private Spaces. |

||||

Chart 2 end

The vast majority of Indigenous (94%) and non-Indigenous (92%) women who experienced IPV in the 12 months preceding the survey reported that the incident had an emotional impact. About seven in ten Indigenous (70%) and non-Indigenous (68%) women spoke with someone, such as a family member, friend, doctor, or lawyer, about the abuse, and about one in ten Indigenous (12%) and non-Indigenous (13%) women used or contacted a service following abuse experienced in the 12 months preceding the survey.

Similar proportions of Indigenous (19%) and non-Indigenous (20%) women who experienced IPV in the past 12 months sustained a physical injury, such as a bruise, cut, fracture, or internal injury, from the abuse. One-quarter (25%) of Indigenous women who experienced IPV in the past month experienced symptoms consistent with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD); this proportion was not statistically different from the proportion among non-Indigenous women (12%) who experienced IPV in the same time frame.

Non-significant differences in consequences and actions following IPV may reflect barriers among Indigenous women to report experiences of IPV or access services following abuse. Some barriers include the inaccessibility of resources, supports and services due to a lack of culturally relevant programs and services, as well as a lack of available services in more remote locations (National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls 2019; Pauktuutit Inuit Women of Canada and Comack 2020). In addition, Indigenous women may seek other forms of support, such as cultural practices and processes of healing within Indigenous communities, which may not be captured in the measures collected in the SSPPS.

For additional results on the experience of IPV among Indigenous women in Canada, see Heidinger 2021.

More than half of Indigenous women experience non-intimate partner violence

As with violence committed by an intimate partner, a higher proportion of Indigenous women have experienced violent victimization committed by a non-intimate partner—another perpetrator with whom the victim did not have an intimate relationship with, including acquaintances, friends, family members, co-workers, strangers and others. Overall, more than half (55%) of Indigenous women have experienced violent physical or sexual assault by a non-intimate partner in their lifetime (Table 5A; Chart 1A). More specifically, First Nations (58%) and Métis (55%) women have experienced significantly higher levels of violent victimization by a non-intimate partner. In comparison, about four in ten (38%) non-Indigenous women have experienced violent victimization by a non-intimate partner (Table 5B; Chart 1B).

Indigenous women more likely to experience physical or sexual victimization by a non-intimate partner in their lifetime

Indigenous women (43%) were significantly more likely to have experienced physical violence by a non-intimate partner in their lifetime. In particular, almost half (48%) of First Nations women and four in ten (40%) Métis women have experienced physical assault by a non-intimate partner in their lifetime. In contrast, about a quarter (26%) of non-Indigenous women have experienced physical assault by a non-intimate partner. The proportion of non-intimate partner physical assault reported by Inuit women (23%) was not statistically different from the proportion reported by non-Indigenous women (Table 5B).

As with physical violence by a non-intimate partner, Indigenous women were overrepresented as victims of sexual violence by a non-intimate partner in their lifetime, with more than four in ten (43%) Indigenous women experiencing sexual violence during this time frame. More specifically, almost half of First Nations (46%) and Métis (44%) women have experienced sexual assault by a non-intimate partner. Approximately one quarter (24%) of Inuit women reported experiencing sexual violence by a non-intimate partner in their lifetime; this proportion was not statistically different from the proportion reported among non-Indigenous women (30%; Table 5B).

End of text box 2

Intersection of Indigenous identity with other factors increases prevalence of violent victimization

Various demographic and socioeconomic factors, such as age, intersect and may be associated with a higher prevalence of violent victimization. While, lifetime violent victimization was higher among Indigenous women overall, the intersectionality of Indigenous identity with other socio-economic and demographic factors may contribute to differences in the prevalence of lifetime violent victimization among Indigenous women.

Among Indigenous women, those with a disability (74%) were more likely than Indigenous women without a disability (50%) to have experienced lifetime violent victimization. In addition, Indigenous women with a disability were more likely than non-Indigenous women with a disability to have experienced lifetime violent victimization (74% versus 57%, respectively). In the 12 months preceding the survey, Indigenous women with a disability (12%) were two and a half times more likely than Indigenous women without a disability (5.0%) to have experienced violent victimization (Table 6).

Experiences of homelessness among Indigenous women associated with lifetime violent victimization

According to the SSPPS, 9.4% of Indigenous women have ever experienced homelessness—that is, having to live in a shelter, on the street, or in an abandoned building. This proportion was almost five times larger than the proportion among non-Indigenous women (1.9%). Furthermore, about a quarter (26%) of Indigenous women ever had to temporarily live with family or friends or anywhere else because they had nowhere else to stay compared with one in ten (10%) non-Indigenous women.

Among Indigenous women who reported experiencing homelessness, the vast majority (91%) also experienced lifetime violent victimization compared with six in ten (60%) Indigenous women who had not experienced homelessness. Similarly, Indigenous women who ever had to temporarily live with family or friends or anywhere else because they had nowhere else to live (85%) were more likely than Indigenous women who did not have to temporarily live elsewhere (55%) to have experienced violent victimization in their lifetime (Table 6).

Indigenous women six times more likely to have ever been under the legal responsibility of the government

A history of colonialization and forced assimilation has impacted Indigenous families negatively and contributed to the financial hardship and neglect present in a disproportionate number of Indigenous families and communities (Truth and Reconciliation report 2015). The legacy of the wide spread apprehension of Indigenous children, and placement of these children into systems that failed to protect them, has had lasting harms. In particular, Indigenous children were forcibly removed from families and communities and placed in residential schools intended to dismantle Indigenous culture and identity. Experiences of sexual, physical, and emotional abuse and maltreatment were rampant in residential schools and contributed to a learned behaviour of violence (Sharma et al. 2021).

As residential school systems were dismantled, the apprehension of thousands of Indigenous children continued. During the Sixties Scoop, large numbers of Indigenous children were forcibly removed from their families and placed in adoptive or foster homes (Sharma et al. 2021). While the last residential school in Canada closed in 1996, Indigenous children continue to be removed from their homes and communities. The disproportionate number of Indigenous children in the child welfare system and the especially high rate of death among Indigenous children within this system further suggests that these systems continue the oppression and assimilation of Indigenous communities (Truth and Reconciliation report 2015).

In certain circumstances, the government may assume the rights and responsibilities of a parent for the purpose of the child’s care, custody and control, such as in foster care, group home under child protection or child welfare services, or residential school for Indigenous children. The SSPPS asked respondents if as a child, they were ever under the legal responsibility of the government.Note Results indicated that Indigenous women had disproportionately experienced placement in the child welfare system compared with non-Indigenous women. Notably, Indigenous women (11%) were almost six times more likely than non-Indigenous women (2.3%) to have ever been under the legal responsibility of the government (Table 7A). Specifically, about one in six (16%) First Nations women were ever under the legal responsibility of the government, eight times higher than non-Indigenous women. The proportion of Métis (7.0%) and Inuit (6.9%) women ever under the legal responsibility of the government was over three times higher than non-Indigenous women (Table 7B).

Being under the legal responsibility of the government was associated with a greater likelihood of lifetime violent victimization. About eight in ten (81%) Indigenous women who were ever under the legal responsibility of the government experienced lifetime violent victimization. In comparison, six in ten (60%) Indigenous women who were never under the legal responsibility of the government experienced lifetime violent victimization (Table 8).

More than four in ten Indigenous women experienced physical or sexual abuse during childhood

In addition to being under the legal responsibility of the government, early childhood experiences of abuse and neglect can also increase the risk for violent victimization in adulthood (Cotter 2021a; Perreault 2021; Whitfield et al. 2003).

A history of abuse and trauma rooted in experiences of colonialization continue to have a negative impact on Indigenous peoples (Andersson and Nahwegahbown 2010). Experiences of trauma and displacement at an early age, linked to placement in residential schools and foster care systems where abuse and maltreatment were rampant, may further perpetuate violence through the cycle of intergenerational trauma and contribute to an increased risk of child abuse.

Results from the SSPPS indicate that Indigenous women are overrepresented as victims of childhood violence and maltreatment by an adult, such as a parent, other family member, friend, neighbour, or other adult. Overall, Indigenous women (42%) were more likely than non-Indigenous women (27%) to have been physically or sexually abused by an adult before the age of 15 (Table 7A). In particular, more than four in ten First Nations (42%) and Métis (43%) women experienced physical or sexual assault by an adult during childhood (Table 7B).

About three in ten (32%) Indigenous women have experienced physical abuse by an adult during childhood with about a third of First Nations (33%) and Métis (34%) women having experienced physical abuse before the age of 15. In comparison, about two in ten (22%) non-Indigenous women have experienced physical abuse by an adult during childhood.

Indigenous women (22%) were two times more likely than non-Indigenous women (11%) to have experienced sexual abuse by an adult before the age of 15. More specifically, about two in ten First Nations (22%) and Metis (22%) women have experienced sexual abuse during childhood.

All types of childhood maltreatment measured were more common among Indigenous women

Overall, Indigenous women have experienced childhood physical and sexual abuse by an adult at higher rates relative to non-Indigenous women; this was true for each of the specific forms of child maltreatment measured (Table 7A; Chart 3). Indigenous women were more likely to have been slapped on the face, on the head or ears or hit with a hard object (26% versus 19% of non-Indigenous women) by an adult during childhood. Notably, Indigenous women were almost two times more likely to have been pushed, grabbed or shoved or had a hard object thrown at them (22% versus 12% of non-Indigenous women), or to have been kicked, bit, punched, choked, burned or physically attacked in some way (12% versus 5.2%) by an adult during childhood.

Chart 3 start

Data table for Chart 3

| Indigenous women | Non-Indigenous womenData table for chart 3 Note † | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| percent | standard error | percent | standard error | |

| Experienced physical or sexual assault | 41.9Note * | 2.4 | 27.4 | 0.5 |

| Experienced physical assault | 31.9Note * | 2.2 | 22.0 | 0.5 |

| Ever slapped or hit by an adult | 25.8Note * | 2.1 | 18.7 | 0.4 |

| Ever pushed, grabbed, or shoved by an adult | 22.0Note * | 2.1 | 12.0 | 0.4 |

| Ever kicked, punched or choked by an adult | 11.6Note * | 1.5 | 5.2 | 0.2 |

| Experienced sexual assault | 21.8Note * | 2.0 | 11.4 | 0.3 |

| Ever forced into unwanted sexual activity by an adult | 14.6Note * | 1.7 | 5.0 | 0.2 |

| Ever touched in a sexual way by an adult | 21.4Note * | 2.0 | 11.1 | 0.3 |

|

||||

Chart 3 end

Furthermore, Indigenous women were three times more likely to have been forced into unwanted sexual activity by an adult (15% versus 5.0% of non-Indigenous women) and about twice as likely to have been touched in a sexual way by an adult (21% versus 11%) during childhood (Table 7A).

One in ten Indigenous women had basic needs unmet during childhood

In addition to a higher prevalence of child abuse, the history of trauma and forced assimilation linked to experiences of colonialization may also negatively impact parenting patterns and impede the success of Indigenous families across generations through the cycle of abuse (Truth and Reconciliation report 2015). Prior to colonialization, child-rearing in Indigenous communities involved a network of family, extended family and community. However, in addition to the loss of tradition, language and culture, colonialization resulted in the loss of family and community connections. In particular, residential schools contributed to the dismantling of Indigenous culture and traditional parenting patterns and resulted in a lack of parenting skills and positive parenting role models (Lafrance and Collins 2013).

Harsh parenting during childhood, as defined in the SSPPS, includes having been slapped, spanked, made to feel unwanted or unloved, or been neglected or having basic needs unmet by parents or guardians. It is important to note that a disproportionately large proportion of Indigenous children have spent part or all of their lives in foster care; therefore, experiences of harsh parenting among Indigenous women may not have occurred by a parent or guardian within the birth family.

Overall, similar proportions of Indigenous women and non-Indigenous women have experienced harsh parenting during childhood (68% and 65%, respectively). However, during childhood, Indigenous women were more likely to have had a parent or guardian who made them feel unwanted or unloved (29% versus 22% of non-Indigenous women) and were two times more likely to have had a parent or guardian who did not take care of their basic needsNote (10% versus 4.1%; Table 7A; Chart 4). Experiences of having basic needs unmet may be the result of economic difficulties rather than parental neglect; however, the vast majority of women, both Indigenous and non-Indigenous, who did not have their basic needs met also experienced at least one other type of harsh parenting by a parent or guardian.

Chart 4 start

Data table for Chart 4

| Indigenous women | Non-Indigenous womenData table for chart 4 Note † | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| percent | standard error | percent | standard error | |

| Experienced harsh parenting | 67.8 | 2.3 | 64.9 | 0.5 |

| Ever spanked or slapped by parent | 54.8 | 2.4 | 54.4 | 0.6 |

| Parent ever said things that hurt feelings | 44.5 | 2.5 | 42.5 | 0.6 |

| Ever felt not wanted or loved by parent | 28.8Note * | 2.1 | 21.9 | 0.5 |

| Parent did not take care of your basic needs | 10.2Note * | 1.5 | 4.1 | 0.2 |

|

||||

Chart 4 end

More specifically, First Nations women (13%) were three times more likely, and Métis women (8.1%) were two times more likely, to have had a parent or guardian who did not take care of their basic needs during childhood compared with non-Indigenous women (4.1%; Table 7B). There were no significant differences for these experiences between Inuit women and non-Indigenous women.

Witnessing violence during childhood is another early childhood experience that can have detrimental consequences during adulthood. Indigenous women were overrepresented in experiences of hearing or witnessing violence during childhood. In particular, during childhood, Indigenous women were more likely to have heard or seen any of their parents or caregivers say hurtful or mean things to each other or to another adult in their home (54% versus 46% of non-Indigenous women) and two times more likely to have heard or seen any one of their parents, step-parents or guardians hit each other or another adult (25% versus 12%).

Experiences of childhood physical or sexual abuse associated with lifetime violent victimization

Childhood experiences of victimization and maltreatment are important risk factors for violent victimization in adulthood (Brownridge et al. 2017; Burczycka 2017; Cotter 2021a; Perreault 2015). For Indigenous peoples in particular, the forced removal of children from homes and communities and the placement of Indigenous children in residential schools or foster homes resulted in many Indigenous children experiencing abuse and neglect. This dismantling of culture and identity coupled with experiences of childhood trauma and maltreatment has had long lasting consequences that continues to perpetuate across generations (Andersson and Nahwegahbown 2010; Gone 2013). Results from the SSPPS further highlight the disproportionate prevalence of violence among Indigenous women with a history of childhood abuse and maltreatment.

Experiencing physical or sexual abuse by an adult during childhood was associated with a higher likelihood of lifetime victimization for women overall. However, Indigenous women who had experienced abuse by an adult during childhood were two times more likely to have experienced lifetime violent victimization (88%) compared with Indigenous women who had not experienced abuse during childhood (44%). Similarly, non-Indigenous women who had experienced childhood abuse by an adult were two times more likely to have experienced lifetime violent victimization (72%) than non-Indigenous women who had not experienced abuse during childhood (34%; Table 8).

Experiences of harsh parenting in childhood associated with increased risk of lifetime violent victimization

Experiencing harsh parenting by a parent or guardian during childhood was also associated with lifetime violent victimization. Approximately three-quarters (73%) of Indigenous women who had experienced harsh parenting by a parent or guardian during childhood experienced lifetime violent victimization, significantly larger than the proportion of Indigenous women who had not experienced harsh parenting (41%). This pattern was also evident among non-Indigenous women where a higher proportion who had experienced harsh parenting by a parent or guardian during childhood experienced lifetime violent victimization (56%) compared with the proportion of non-Indigenous women who had not experienced harsh parenting (23%; Table 8).

In addition, Indigenous women who witnessed violence before the age of 15 were more likely to experience lifetime victimization compared with Indigenous women who did not witness violence during childhood. In particular, Indigenous women who saw or heard any of their parents or caregivers say hurtful or mean things to each other or to another adult in their home were more likely to have experienced lifetime victimization (74%) compared with Indigenous women who had not experienced this type of violence (49%). Similarly, Indigenous women who saw or heard any one of their parents, step-parents or guardians hit each other or another adult were more likely to have experienced lifetime violent victimization (83%) compared with Indigenous women who had not experienced this type of violence (56%).

This pattern was also evident among non-Indigenous women. A higher proportion of non-Indigenous women who saw or heard any of their parents or caregivers say hurtful or mean things to each other or to another adult in their home experienced lifetime violent victimization (59%) compared with the proportion of non-Indigenous women who had not experienced this type of violence (32%). Non-Indigenous women who saw or heard any one of their parents, step-parents or guardians hit each other or another adult were also more likely to have experienced lifetime violent victimization (69%) compared with non-Indigenous women who had not experienced this type of violence (42%).

Start of Text Box 3

Text box 3

Homicide among Indigenous women in Canada

Homicide is a relatively rare occurrence in Canada and accounts for a small proportion of police-reported violence; however, it is the most severe form of violence and, similar to violent victimization, Indigenous women are overrepresented as victims of this type of violence (Armstrong and Jaffray 2021).

In response to the murder and disappearance of Indigenous women and girls in large numbers, the Government of Canada, along with other agencies, launched a National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls in 2016. The inquiry highlighted that Indigenous women and girls are 12 times more likely to be missing or murdered compared with non-Indigenous women and girls (National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls 2019).

According to the Homicide Survey, between 2015 and 2020 there were 1,000 womenNote who were victims of homicide in Canada. While Indigenous women represent approximately 5% of women in Canada, they represented almost one-quarter (24%; 241 victims) of all women homicide victims over this time. From 2015 to 2020, police have reported 168 First Nations women (17% of all women victims of homicide), 26 Inuit women (3%), and 12 Métis women (1%) as victims of homicide. An additional 35 women homicide victims were reported by police as being Indigenous but their specific Indigenous identity group was unknown. These victims accounted for 4% of women victims.

Indigenous women victims of homicide were generally younger than non-Indigenous women victims of homicide on average from 2015 to 2020. Results mirror the age distribution of the general population, whereby the Indigenous population is younger than the non-Indigenous population. Just over one in ten (13%) Indigenous women victims of homicide were considered a missing person at the time of their death from 2015 to 2020 (Table 9).

The majority of women victims of homicide between 2015 and 2020 knew their killer. The proportion of Indigenous women (3.9%) who were killed by a stranger during this time frame was smaller than the proportion of non-Indigenous women (11%) who were killed by a stranger. Among Indigenous women victims of homicide, about a quarter (26%) were killed by an acquaintance (i.e., non-family) and more than half (54%) were killed by a family member, including 27% by a current or former spouse and 27% by another family member.

In 2020, about 23% (163 homicides) of homicide victims were women and almost one-quarter (23%; 38 homicides) of those were Indigenous. The homicide rate for Indigenous women (3.8 per 100,000 Indigenous women) in 2020 was more than five times that of non-Indigenous women (0.7 per 100,000 non-Indigenous women; Table 10; Chart 5).

Chart 5 start

Data table for Chart 5

| Indigenous womenData table for chart 5 Note 1 | Non-Indigenous womenData table for chart 5 Note 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| number | rateData table for chart 5 Note 3 | number | rateData table for chart 5 Note 3 | |

| 2015 | 43 | 4.9 | 134 | 0.8 |

| 2016 | 30 | 3.3 | 122 | 0.7 |

| 2017 | 38 | 4.1 | 132 | 0.8 |

| 2018 | 45 | 4.7 | 121 | 0.7 |

| 2019 | 47 | 4.8 | 100 | 0.6 |

| 2020 | 38 | 3.8 | 125 | 0.7 |

Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics, Homicide Survey. |

||||

Chart 5 end

For more information on homicide in Canada, see Armstrong and Jaffray 2021.

End of text box 3

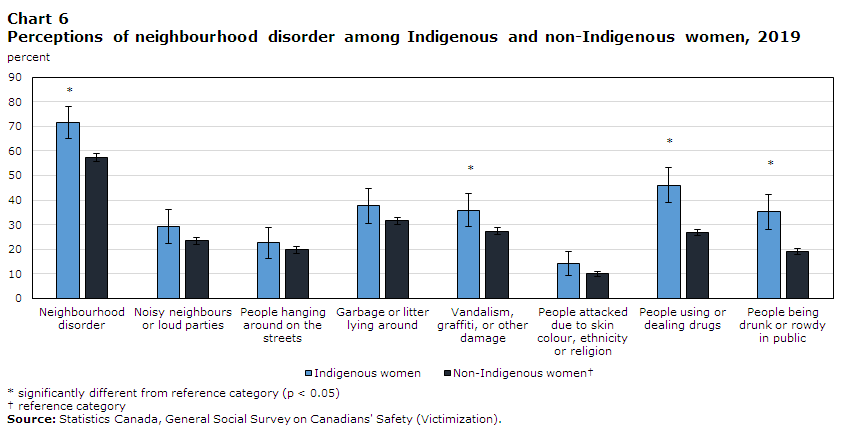

Indigenous women more likely to perceive indicators of social disorder in their neighbourhood

The 2019 General Social Survey (GSS) on Canadians’ Safety (Victimization) included questions on perceptions of neighbourhood, including a measure of social cohesion and whether social or physical disorder were problems in participants’ neighbourhoods. Perceptions of neighbourhoods can be reliable indicators of safety and trust within a social environment and can be used to gage the level of social order and control (Gau and Pratt 2008).

According to the GSS on Victimization, a larger proportion of Indigenous women lived in communities where they were acquainted with their neighbours. Specifically, about half (48%) of Indigenous women reported residing in a neighbourhood where they know most or many of the people compared with about one-third (34%) of non-Indigenous women (Table 11A). While knowing most or many people in a neighbourhood is a good indicator of social cohesion and a measure of neighbourhood community, integration and shared values, other neighbourhood factors, such as the level of neighbourhood disorder, may also contribute to an increased risk of victimization.

Neighbourhood disorder or social disorder is associated with higher victimization rates and lower levels of life satisfaction, and is linked to perceptions of neighbourhood safety, including elevated fear when walking alone at night or taking public transportation (Cotter 2016; Perreault 2015). Neighbourhood disorder is often an indicator of the level of perceived safety and crime in neighbourhoods. Indigenous women were more likely to perceive indicators of social disorder in their neighbourhood, with about seven in ten (71%) Indigenous women reporting at least one small, moderate, or big problem in their neighbourhood. In comparison, almost six in ten (57%) non-Indigenous women perceived social disorder in their neighbourhood (Table 11A). The measure of social disorder included indicators such as the extent of noisy neighbours or loud parties, garbage or litter lying around, people being attacked due to skin colour, ethnicity or religion, and people using or dealing drugs in their neighbourhood (Chart 6).

Chart 6 start

Data table for Chart 6

| Indigenous women | Non-Indigenous womenData table for chart 6 Note † | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| percent | standard error | percent | standard error | |

| Neighbourhood disorder | 71.5Note * | 3.4 | 57.4 | 0.8 |

| Noisy neighbours or loud parties | 29.2 | 3.5 | 23.4 | 0.7 |

| People hanging around on the streets | 22.6 | 3.2 | 19.7 | 0.6 |

| Garbage or litter lying around | 37.6 | 3.6 | 31.6 | 0.8 |

| Vandalism, graffiti, or other damage | 35.9Note * | 3.4 | 27.3 | 0.7 |

| People attacked due to skin colour, ethnicity or religion | 14.3 | 2.5 | 9.9 | 0.5 |

| People using or dealing drugs | 46.1Note * | 3.6 | 26.8 | 0.7 |

| People being drunk or rowdy in public | 35.3Note * | 3.7 | 19.2 | 0.6 |

|

||||

Chart 6 end

Similar proportions of Indigenous (13%) and non-Indigenous (17%) women felt somewhat or very unsafe when walking alone in their neighbourhood after dark. These proportions are based on respondents who walked alone after dark, and did not include about one-quarter of respondents who said they did not walk alone after dark in their neighbourhood. The choice to not walk alone in neighbourhood after dark may be due to concerns about safety.

Indigenous women twice as likely to have not very much or no confidence in police

Perceptions of police may be associated with the level of crime in a neighbourhood or community and as such are a critical aspect of public safety. Confidence and opinions about the police may be shaped by varying factors including direct personal experience, the influence of others, and the influence of the media (Chow 2012). Negative experiences with police, such as experiences of discrimination or inequality, can impact perceptions of police, and how citizens view police may further influence reporting of crime and victimization (Ibrahim 2020).

For Indigenous peoples, experiences of colonialization and the historical involvement of police in systems of oppression, such as residential schools, have tarnished the relationship between Indigenous peoples and the police (Cao 2014). Other studies suggest that involvement with the criminal justice system and the overrepresentation of Indigenous peoples in the correctional system may further perpetuate the mistrust in police among Indigenous peoples (Truth and Reconciliation report 2015).

While a large majority of Indigenous women indicated having a great deal of confidence in police (82%), the proportion was lower than among non-Indigenous women (91%). Moreover, Indigenous women (17%) were more than twice as likely to report having not very much or no confidence in the police compared with non-Indigenous women (8.2%; Table 11A; for results by Indigenous identity group see Table 11B).

Summary

This article examined violent victimization and perceptions of safety among Indigenous women, and provides an overall statistical overview of gender-based violence experienced by First Nations, Métis and Inuit women in Canada.

According to data from the Survey of Safety in Public and Private Spaces (SSPPS), Indigenous women are overrepresented as victims of violence with more than six in ten (63%) Indigenous women having experienced physical or sexual violence in their lifetime compared with non-Indigenous women (45%). This overrepresentation of Indigenous women in experiences of violent victimization is linked to historical and continued experiences of violence and trauma linked to colonialization and related policies aimed at erasing Indigenous cultures and dismantling Indigenous families and communities.

Certain characteristics were associated with a higher likelihood of experiencing lifetime violent victimization among Indigenous women, including having a disability or ever having experienced homelessness. Childhood experiences, including experiences of abuse, maltreatment and neglect were also associated with a higher likelihood of lifetime violent victimization. Notably, Indigenous women who had ever been under the legal responsibility of the government were more likely to have experienced violent victimization compared with Indigenous women who were never under the legal responsibility of the government.

When looking at perceptions of neighborhood cohesion and disorder, data from the General Social Survey (GSS) on Canadians’ Safety (Victimization) found that while Indigenous women were more likely than non-Indigenous women to be acquainted with their neighbours, Indigenous women were also more likely to perceive indicators of social disorder in their neighbourhood. Compared with non-Indigenous women, Indigenous women were more than twice as likely to report having not very much or no confidence in the police.

Detailed data tables

Table 7A Childhood abuse and maltreatment among women, by Indigenous identity, Canada, 2018

Table 7B Childhood abuse and maltreatment among women, by Indigenous identity group, Canada, 2018

Table 10 Homicides among women, by Indigenous identity and year, Canada, 2015 to 2020

Survey description

Survey of Safety in Public and Private Spaces

In 2018, Statistics Canada conducted the first cycle of the Survey of Safety in Public and Private Spaces (SSPPS). The purpose of the survey is to collect information on Canadians’ experiences in public, at work, online, and in their intimate partner relationships.

The target population for the SSPPS is the Canadian population aged 15 and over, living in the provinces and territories. Canadians residing in institutions are not included. This means that the survey results may not reflect the experiences of intimate partner violence among those living in shelters, institutions, or other collective dwellings. Once a household was contacted, an individual 15 years or older was randomly selected to respond to the survey.

In the provinces, data collection took place from April to December 2018 inclusively. Responses were obtained by self-administered online questionnaire or by interviewer-administered telephone questionnaire. Respondents were able to respond in the official language of their choice. The sample size for the 10 provinces was 43,296 respondents. The response rate in the provinces was 43.1%.

In the territories, data collection took place from July to December 2018 inclusively. Responses were obtained by self-administered online questionnaire or by interviewer-administered in-person questionnaire. Respondents were able to respond in the official language of their choice. The sample size for the 3 territories was 2,597 respondents. The response rate in the territories was 73.2%.

Non-respondents included people who refused to participate, could not be reached, or could not speak English or French. Respondents in the sample were weighted so that their responses represent the non-institutionalized Canadian population aged 15 and older.

General Social Survey on Victimization

This article uses data from the General Social Survey (GSS) on Canadians’ Safety (Victimization). In 2019, Statistics Canada conducted the GSS on Victimization for the seventh time. Previous cycles were conducted in 1988, 1993, 1999, 2004, 2009 and 2014. The main objective of the GSS on Victimization is to better understand issues related to the safety and security of Canadians, including perceptions of crime and the justice system, experiences of intimate partner violence, and how safe people feel in their communities.

The target population was persons aged 15 and older living in the provinces and territories, except for those living full-time in institutions.

Data collection took place between April 2019 and March 2020. Responses were obtained by computer-assisted telephone interviews (CATI), in-person interviews (in the territories only) and, for the first time, the GSS on Victimization offered a self-administered internet collection option to survey respondents in the provinces and in the territorial capitals. Respondents were able to respond in the official language of their choice.

An individual aged 15 or older was randomly selected within each household to respond to the survey. An oversample of Indigenous people was added to the 2019 GSS on Victimization to allow for a more detailed analysis of individuals belonging to this population group. In 2019, the final sample size was 22,412 respondents.

In 2019, the overall response rate was 37.6%. Non-respondents included people who refused to participate, could not be reached, or could not speak English or French. Respondents in the sample were weighted so that their responses represent the non-institutionalized Canadian population aged 15 and older.

Data limitations

As with any household survey, there are some data limitations. The results are based on a sample and are therefore subject to sampling errors. Somewhat different results might have been obtained if the entire population had been surveyed.

For the quality of estimates from the SSPPS and GSS on Victimization, the lower and upper bounds of the confidence intervals are presented. Confidence intervals should be interpreted as follows: If the survey were repeated many times, then 95% of the time (or 19 times out of 20), the confidence interval would cover the true population value.

Homicide Survey

The Homicide Survey collects police-reported data on the characteristics of all homicide incidents, victims and accused persons in Canada. The Homicide Survey began collecting information on all murders in 1961 and was expanded in 1974 to include all incidents of manslaughter and infanticide. Although details on these incidents are not available prior to 1974, counts are available from the Uniform Crime Reporting Survey (UCR) and are included in the historical aggregate totals.

Whenever a homicide becomes known to police, the investigating police service completes the survey questionnaires, which are then sent to Statistics Canada. There are cases where homicides become known to police months or years after they occurred. These incidents are counted in the year in which they become known to police (based on the report date). Information on persons accused of homicide are only available for solved incidents (i.e., where at least one accused has been identified). Accused characteristics are updated as homicide cases are solved and new information is submitted to the Homicide Survey. Information collected through the victim and incident questionnaires is also accordingly updated as a result of a case being solved. For incidents involving more than one accused, only the relationship between the victim and the closest accused is recorded.

Due to revisions to the Homicide Survey database, annual data reported by the Homicide Survey prior to 2015 may not match the annual homicide counts reported by the UCR. Data from the Homicide Survey are appended to the UCR database each year for the reporting of annual police-reported crime statistics. Each reporting year, the UCR includes revised data reported by police for the previous survey year. In 2015, a review of data quality was undertaken for the Homicide Survey for all survey years from 1961 to 2014. The review included the collection of incident, victim and charged/suspect-chargeable records that were previously unreported to the Homicide Survey. In addition, the database excludes deaths, and associated accused records, which are not deemed as homicides by police any longer (i.e., occurrences of self-defense, suicide, criminal negligence causing death that had originally been deemed, but no longer considered homicides, by police). For operational reasons, these revisions were not applied to the UCR.

Defining Indigenous identity for the Homicide Survey

Indigenous identity is reported by police to the Homicide Survey and is determined through information found with the victim or accused person, such as status cards, or through information supplied by victims' or accused persons' families, the accused persons themselves, community members, or other sources (i.e., such as band records). Forensic evidence such as genetic testing results may also be an acceptable means of determining the Indigenous identity of victims.

For the purposes of the Homicide Survey, Indigenous identity includes those identified as First Nations persons (either status or non-status), Métis, Inuit, or an Indigenous identity where the Indigenous group is not known to police. Non-Indigenous identity refers to instances where the police have confirmed that a victim or accused person is not identified as an Indigenous person. Indigenous identity reported as ‘unknown’ by police includes instances where police are unable to determine the Indigenous identity of the victim or accused person, where Indigenous identity is not collected by the police service, or where the accused person has refused to disclose their Indigenous identity to police.

References

Andersson, N. and A. Nahwegahbow. 2010. “Family violence and the need for prevention research in First Nations, Inuit, and Métis Communities.” Pimatisiwin. Vol. 8, no. 2. p. 9-33

Armstrong, A. and B. Jaffray. 2021. “Homicide in Canada, 2020.” Juristat. Catalogue no. 85-002-X.

Boyce, J. 2016. “Victimization of Aboriginal people in Canada, 2014.” Juristat. Catalogue no. 85-002-X.

Brassard, R., Montminy, L., Bergeron, A., and I. Sosa-Sanchez. 2015. “Application of Intersectional analysis to data on domestic violence against Aboriginal women living in remote communities in the province of Quebec.” Aboriginal Policy Studies. Vol. 4, no. 1. p. 3-23.

Brownridge, D., Taillieu, T., Afifi, T., Chan, K., Emery, C., Lavoie, J., and F. Elgar. 2017. “Child Maltreatment and Intimate Partner Violence among Indigenous and Non-Indigenous Canadians.” Journal of Family Violence. Vol. 32, no. 6. p. 607-619

Burczycka, M. 2016. “Trends in self-reported spousal violence in Canada, 2014.” In “Family violence in Canada: A statistical profile, 2014.” Juristat. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 85-002-X.

Cao, L. 2014. “Aboriginal people and confidence in the police.” Canadian Journal of Criminology and Criminal Justice. Vol. 1. p. 1-34.

Chow, H. 2012. “Attitudes towards police in Canada: A study of perceptions of university students in a western Canadian city.” International Journal of Criminal Justice Sciences. Vol. 7, no. 1. p. 508-523.

Conroy, S. 2021. “Family violence in Canada: A statistical profile, 2019.” Juristat. Catalogue no. 85-002-X.

Cotter, A. 2016. “Canadians’ perceptions of neighbourhood disorder, 2014. Spotlight on Canadians: Results from the General Social Survey.” Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 89-652-X.

Cotter, A. 2021a. “Intimate partner violence in Canada, 2018: An overview.” Juristat. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 85-002-X.

Cotter, A. 2021b. “Criminal Victimization in Canada, 2019.” Juristat. Catalogue no. 85-002-X.

Gau, J.M. and T.C. Pratt. 2008. “Broken windows or window dressing? Citizens’ (in)ability to tell the difference between disorder and crime.” Criminology and Public Policy. Vol. 7, no. 2. p. 163-194.

Gone, J. 2013. “Redressing First Nations Historical Trauma: Theorizing mechanisms for Indigenous culture as mental health treatment.” Transcultural Psychiatry. Vol. 50, no. 5. p. 683-706.

Heidinger, L. 2021. “Intimate partner violence: Experiences of First Nations, Métis, and Inuit women in Canada, 2018.” Juristat. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 85-002-X.

Ibrahim, D. 2020. “Public perceptions of the police in Canada’s provinces, 2019.” Juristat. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 85-002-X.

Johnson, M.P. and J.M. Leone. 2005. “The differential effects of intimate terrorism and situational couple violence: Findings from the National Violence Against Women Survey.” Journal of Family Issues. Vol. 26, no. 3. p. 322‑349.

Karakurt, G., Smith, D. and J. Whiting. 2014. “Impact of Intimate Partner Violence on Women’s Mental Health.” Journal of Family Violence. Vol. 29, no. 7. p. 693–702.

Lafrance, J. and D. Collins. 2013. Residential School and Aboriginal Parenting: Voices of Parents. Native Social Work Journal. 4(1). p. 104-125.

National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls. 2019. “Reclaiming Power and Place: The Final Report of the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls.”

Pauktuutit Inuit Women of Canada and E. Comack. 2020. “Addressing Gendered Violence against Inuit Women: A review of police policies and practices in Inuit Nunangat.” Report in Brief and Recommendations.

Perreault, S. 2020. “Gender-based violence: Sexual and physical assault in Canada’s territories, 2018.” Juristat. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 85-002-X.

Perreault, S. 2015. “Criminal victimization in Canada, 2014.” Juristat. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 85-002-X.

Postmus, J., Hoge, G., Breckenridge, J., Sharp-Jeffs, N., and D. Chung. 2020. “Economic Abuse as an Invisible Form of Domestic Violence: A multicountry review.” Trauma, Violence and Abuse. Vol. 21, no. 2. p. 261-283.

Public Health Agency of Canada. 2020. “Family Violence Initiative.”

Sharma, R., Pooyak, S., Jongbloed, K., Zamar, D., Pearce, M. E., Mazzuca, A., Schechter, M. T., Spittal, P. M., and Cedar Project Partnership. 2021. “The Cedar Project: Historical, structural and interpersonal determinants of involvement in survival sex work over time among Indigenous women who have used drugs in two Canadian cities.” International Journal of Drug Policy. Vol. 87.

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. 2015. “Honouring the truth, reconciling for the future: summary of the final report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada.”

Whitfield, C., Anda, R., Dube, S., and V. Felitti. 2003. “Violent childhood experiences and the risk of intimate partner violence in adults: Assessment in a large health maintenance organization.”Journal of Interpersonal Violence. Vol. 18, no. 2. p. 166-185.

Williams, J., Gifford, W., Vanderspank-Wright, B., and J. Phillips. 2019. “Violence and health promotion among First Nations, Métis, and Inuit women: A systemic review of qualitative research.”Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. p. 1-17.

Women and Gender Equality Canada. 2021. “Fact Sheet: Intimate Partner Violence.”

World Health Organization. 2017. “Violence against women.”

- Date modified: