Economic and Social Reports

Immigrant labour market outcomes during recessions: Comparing the early 1990s, late 2000s and COVID-19 recessions

DOI: https://doi.org/10.25318/36280001202200200003-eng

Skip to text

Text begins

Abstract

The labour market outcomes of recently arrived immigrants are often more negatively affected during recessions than those of the Canadian born. Entering the labour market during a recession may also result in “scarring” effects for both immigrants and Canadian-born workers. But the severity and characteristics of recessions vary significantly and may affect the outcomes of immigrants differently. This paper compares immigrants’ outcomes during the past three recessions. The early-1990s recession was more severe and lasted longer than the 2008/2009 recession. The 1990s recession had a large differential impact on the employment rates and earnings of recent immigrants, relative to the Canadian born, while the milder 2008/2009 recession had relatively little differential effect. Both recessions hit the goods-producing sector hardest, and disproportionately affected men, younger workers, and workers with lower levels of education and low seniority. During the COVID-19 downturn, accommodation and food services and retail trade were hit particularly hard; low-wage workers bore the brunt of the recessionary effect, along with less educated workers and young women. Recently immigrated women experienced a greater increase in unemployment than Canadian-born women during the COVID-19 recession, caused in part by their over-representation in some of these groups. There was a small difference between recently immigrated and Canadian-born men in employment and unemployment rates during the COVID-19 recession. There was evidence consistent with possible “scarring” effects for the longer-term earnings of immigrants entering during the early 1990s recession. Evidence from the 2008/2009 recession did not support such a conclusion. It is too early to assess the longer-term effects of the COVID-19 downturn.

Authors

Feng Hou is with the Social Analysis and Modelling Division, Analytical Studies and Modelling Branch, at Statistics Canada. Garnett Picot is with the Research and Evaluation Branch at Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada.

Acknowledgements

This study was conducted in collaboration with Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada. The authors would like to thank Cédric de Chardon, Rebeka Lee, René Morissette and Mikal Skuterud for their advice and comments on an earlier version of this paper.

Introduction

Immigrants often have more negative labour market outcomes during recessions than those born domestically. For Canada, Aydemir (2003) found that higher unemployment in the year of entry, typically during recessions, had an adverse effect on the labour force participation and employment probability of immigrants, relative to the Canadian born. Abbott and Beach (2011) found similar results during the early 1980s and early 1990s recessions. Hou and Picot (2014) showed that a national unemployment rate increase of 1.0 percentage point in the year of admission was associated with a 2.9 percentage point decline in earnings of immigrant men arriving that year, among immigrants admitted between 1980 and 2010. Kelly et al. (2011) found that the unemployment rate gap between immigrants and the Canadian born widened during and after the 2008/2009 recession, although there was significant regional variation. For the U.S., Orrenius and Zavodny (2009) concluded that immigrant economic outcomes are more strongly tied to the business cycle than those of the domestic born. Dustmann et al. (2010) observed larger unemployment responses to negative economic shocks for immigrants than for the domestic born in the United Kingdom and Germany.

Other researchers have focused on the “scarring” effect of entering the labour market during a recession. The idea is that entering the labour market during a period of high unemployment has a negative effect not only at that time, but also years into the future. Both U.S. and British studies have found the same results (Rothstein, 2020; Tumino, 2015). In a recent review, the consensus was that those scarring effects are substantial (Borland, 2020).

These effects may also be found among immigrants. Aydemir (2003) concluded that entering Canada during periods of high unemployment negatively affected immigrants’ economic integration trajectories over the coming years. A U.S. study by Mask (2018) found that for every 1.0 percentage point increase in the national unemployment rate upon arrival, refugees experienced a 3.5 percentage point reduction in wages after 5 years and a 3.7 percentage point reduction in employment after 4 years.

The characteristics of the last three recessions

Scarring effects likely differ across recessions, depending upon the nature of the downturn. The COVID-19 recession was significantly different from both the 2008/2009Note and the 1990-to-1992Note recessions. During the relatively mild 2008/2009 recession, employment bottomed out at about 98% of its pre-recession level after about eight months; during the early 1990s, the employment trough was reached 2.5 years in, at about 96.5%. During the COVID-19 downturn, employment fell rapidly to about 87% of its pre-recession levels after two months, but the recovery was also much faster. Employment returned to pre-recession levels 53 months after the recession began in the 1990s, versus 27 months in the 2008/2009 period (Gilmore and Larochelle-Cote, 2011). The final outcome for the COVID-19 recession remains to be seen, but by September 2021, total employment regained its pre-recession level.

There were considerable differences in the industries hit hardest by the three recessions. The COVID-19 downturn was concentrated among food and accommodation services and retail trade (Statistics Canada, 2021). The recessions of 2008/2009 and 1990 to 1992 were quite different. In both cases, the drop in GDP was concentrated among goods-producing sectors, notably manufacturing and construction. Consumer-based services such as retail trade and food and accommodation experienced a much smaller decline (Cross, 2011).

Differences in industries affected by the recessions resulted in different population groups bearing the weight of the downturns. With the good-producing sector being hit hardest in the two earlier recessions, workers in that sector, men, younger workers, the less educated and workers with low seniority were impacted most (Chan et al., 2011). During the pandemic, low-wage workers in particular were affected. The average layoff rate during the first few months of 2020—the worst of the downturn—was around 13% for workers in the bottom wage quartile, compared with only 2% to 3% on those in the top wage quartile. Among the employed, the proportion working at least one-half of their usual hours at the peak of the downturn (April 2020) fell by 65% among workers in the bottom wage decile compared with pre-downturn levels, but increased by 15% among those in the top wage decile (Statistics Canada, 2021). Other groups experiencing considerable employment loss during the pandemic included the less educated, recent immigrants and young women aged 18 to 24. Women and men aged 25 to 54 experienced similar patterns of employment loss and unemployment during the downturn and recovery (Statistics Canada, 2020 and 2021).

In addition to the severity and duration of each recession, other factors may also influence the relative outcomes for recent immigrants. For example, since the early 2010s, new immigrants were selected increasingly from the temporary foreign worker pool. They are generally more established economically and may be less affected by recessions than immigrants directly admitted from abroad, as was mostly the case in the 1990s.

The relative outcomes for recent immigrants during the 1990s and 2008/2009 recessions

The early 1990s recession had a much greater differential impact on recent immigrantsNote than did the less severe 2008/2009 recession. From 1993 to 1994, the employment incidenceNote among recent immigrant men dropped 14 percentage points below its pre-recession levels, compared with only 6 percentage points for men in the comparison group (including the Canadian born, and longer term immigrants who landed at least 10 years earlier, aged 20 to 49). Similar results were observed for women.Note The differential effect was smaller in the 2008/2009 recession. Between 2008 and 2010, the decline in employment incidence was small for both recently immigrated men and their comparison group (1.5 percentage points), and only marginally greater for female recent immigrants (2.0 percentage points, compared with 1.2 for the comparison group) (Chart 1).

Data table for Chart 1

| Recent immigrants | Comparison group | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recent immigrant men | Recent immigrant women | Comparison group men | Comparison group women | |

| percent | ||||

| 1988 | 92.1 | 77.5 | 93.8 | 79.1 |

| 1989 | 91.6 | 77.7 | 93.4 | 79.8 |

| 1990 | 89.4 | 76.2 | 91.9 | 79.5 |

| 1991 | 84.9 | 72.1 | 90.2 | 78.4 |

| 1992 | 81.6 | 68.7 | 89.0 | 77.5 |

| 1993 | 78.5 | 63.3 | 87.8 | 75.8 |

| 1994 | 78.3 | 62.1 | 87.8 | 75.8 |

| 1995 | 78.0 | 61.3 | 87.7 | 76.3 |

| 1996 | 78.3 | 60.4 | 87.6 | 76.5 |

| 1997 | 79.3 | 60.8 | 88.3 | 77.6 |

| 1998 | 80.5 | 61.8 | 88.7 | 78.7 |

| 1999 | 82.0 | 63.1 | 89.1 | 79.5 |

| 2000 | 83.1 | 64.8 | 89.2 | 80.6 |

| 2001 | 83.8 | 65.5 | 90.6 | 82.7 |

| 2002 | 83.2 | 64.9 | 90.0 | 82.5 |

| 2003 | 83.6 | 65.2 | 90.0 | 82.9 |

| 2004 | 84.3 | 65.8 | 90.1 | 83.2 |

| 2005 | 86.1 | 66.5 | 90.7 | 83.6 |

| 2006 | 85.6 | 67.2 | 90.3 | 83.7 |

| 2007 | 86.4 | 68.1 | 90.4 | 83.9 |

| 2008 | 87.1 | 68.5 | 90.2 | 84.0 |

| 2009 | 85.5 | 66.9 | 89.0 | 83.1 |

| 2010 | 85.6 | 66.5 | 88.7 | 82.8 |

| 2011 | 86.6 | 67.0 | 89.2 | 83.2 |

| 2012 | 87.3 | 67.4 | 89.3 | 83.2 |

| 2013 | 87.8 | 67.8 | 89.1 | 83.2 |

| 2014 | 88.7 | 68.9 | 89.2 | 83.4 |

| 2015 | 89.0 | 69.9 | 89.0 | 83.5 |

| 2016 | 89.6 | 70.8 | 88.9 | 83.6 |

| 2017 | 90.6 | 71.4 | 89.4 | 83.9 |

| 2018 | 91.8 | 73.5 | 89.6 | 84.4 |

|

Notes: Recent immigrants are those who landed 1 to 5 years ago, aged 20 to 44 at landing and aged 20 to 49 in the tax year. The comparison group consists of the Canadian born and immigrants who landed 10 years ago and were aged 20 to 49 in the tax year. Source: 2019 Longitudinal Immigration Database. |

||||

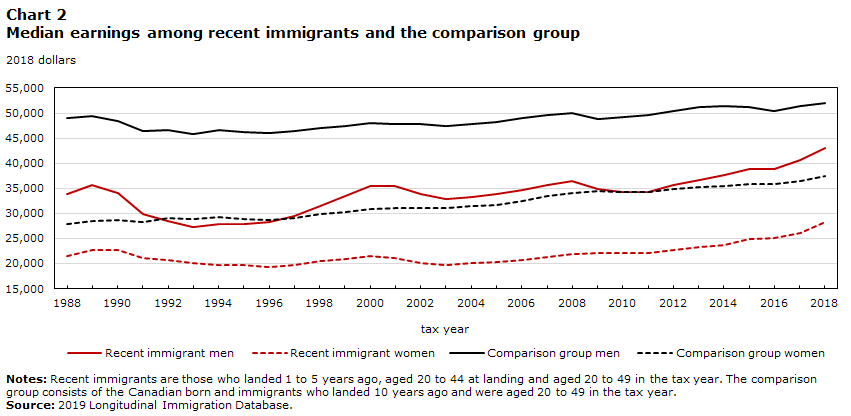

Median annual earnings among individuals with positive earnings tell a similar story (Chart 2). During the 1990s recession, the decline was considerable among recent immigrants, falling 24% from peak to trough among men and 15% among women. The comparison group experienced an 8% decline for men and no decline in annual earnings among women. The 2008/2009 recession saw virtually no decline in earnings among recently immigrated women and their comparison group, and a small decline among recently immigrated men (Chart 2). Overall, recent immigrants were hit much harder, both in absolute terms and relative to the comparison group, during the early 1990s recession than of 2008/2009.

Data table for Chart 2

| Recent immigrants | Comparison group | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recent immigrant men | Recent immigrant women | Comparison group men | Comparison group women | |

| 2018 dollars | ||||

| 1988 | 33,893 | 21,550 | 48,957 | 27,914 |

| 1989 | 35,682 | 22,690 | 49,404 | 28,417 |

| 1990 | 34,030 | 22,596 | 48,425 | 28,738 |

| 1991 | 29,894 | 21,132 | 46,345 | 28,291 |

| 1992 | 28,382 | 20,791 | 46,534 | 28,979 |

| 1993 | 27,250 | 20,176 | 45,906 | 28,815 |

| 1994 | 27,803 | 19,725 | 46,629 | 29,186 |

| 1995 | 27,948 | 19,611 | 46,266 | 28,950 |

| 1996 | 28,269 | 19,378 | 45,996 | 28,759 |

| 1997 | 29,520 | 19,614 | 46,332 | 29,041 |

| 1998 | 31,482 | 20,429 | 47,007 | 29,792 |

| 1999 | 33,489 | 20,885 | 47,423 | 30,318 |

| 2000 | 35,436 | 21,506 | 47,921 | 30,806 |

| 2001 | 35,445 | 21,142 | 47,869 | 31,138 |

| 2002 | 33,782 | 20,134 | 47,746 | 31,106 |

| 2003 | 32,860 | 19,742 | 47,450 | 31,090 |

| 2004 | 33,356 | 20,071 | 47,779 | 31,372 |

| 2005 | 33,937 | 20,204 | 48,196 | 31,623 |

| 2006 | 34,675 | 20,699 | 49,008 | 32,453 |

| 2007 | 35,566 | 21,279 | 49,570 | 33,370 |

| 2008 | 36,360 | 21,992 | 50,017 | 34,077 |

| 2009 | 34,860 | 22,114 | 48,815 | 34,477 |

| 2010 | 34,351 | 22,075 | 49,196 | 34,334 |

| 2011 | 34,333 | 22,117 | 49,558 | 34,341 |

| 2012 | 35,660 | 22,628 | 50,469 | 34,815 |

| 2013 | 36,621 | 23,232 | 51,188 | 35,305 |

| 2014 | 37,662 | 23,672 | 51,413 | 35,410 |

| 2015 | 38,832 | 24,807 | 51,168 | 35,839 |

| 2016 | 38,848 | 25,135 | 50,358 | 35,875 |

| 2017 | 40,592 | 26,116 | 51,310 | 36,455 |

| 2018 | 42,939 | 28,223 | 52,089 | 37,354 |

|

Notes: Recent immigrants are those who landed 1 to 5 years ago, aged 20 to 44 at landing and aged 20 to 49 in the tax year. The comparison group consists of the Canadian born and immigrants who landed 10 years ago and were aged 20 to 49 in the tax year. Source: 2019 Longitudinal Immigration Database. |

||||

How did immigrants entering Canada during the recession of the early 1990s and 2008/2009 fare economically in subsequent years?

Given the concern about possible scarring effects, it is useful to examine how immigrants entering Canada during the two recessions fared economically in subsequent years, compared with those entering prior to the recession during better economic times.

Regarding the 1990s recession, the decline in employment incidence experienced by successive new immigrant cohorts between 1988 and the mid-1990s is evident in Chart 3. Those entering Canada between 1991 and 1993 had much lower incidence of employment shortly after landing. However, about 7 to 15 years after landing there was relatively little difference in employment incidence between the cohorts that entered Canada prior to the recession (e.g., 1988 to 1989) and those that entered throughout it (1991 to 1993). There is little evidence of poorer long-term employment outcomes among cohorts entering during the recession.

Data table for Chart 3

| Years since immigration | 1988 | 1989 | 1990 | 1991 | 1992 | 1993 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| percent | ||||||

| 1 | 84.4 | 82.5 | 76.7 | 72.7 | 67.2 | 67.1 |

| 2 | 83.3 | 79.0 | 74.2 | 70.6 | 68.5 | 68.7 |

| 3 | 79.6 | 76.3 | 72.1 | 70.9 | 69.4 | 69.8 |

| 4 | 77.2 | 72.9 | 71.9 | 71.0 | 70.1 | 71.4 |

| 5 | 73.0 | 72.4 | 71.5 | 71.3 | 71.5 | 72.9 |

| 6 | 72.9 | 72.8 | 72.4 | 73.1 | 73.6 | 74.1 |

| 7 | 73.5 | 74.0 | 74.4 | 75.0 | 74.7 | 74.9 |

| 8 | 74.6 | 75.7 | 76.3 | 75.8 | 75.5 | 76.3 |

| 9 | 76.1 | 77.2 | 76.5 | 76.0 | 77.0 | 76.0 |

| 10 | 77.6 | 77.4 | 76.8 | 77.8 | 76.8 | 76.1 |

| 11 | 77.5 | 77.3 | 78.1 | 77.4 | 76.9 | 76.3 |

| 12 | 77.4 | 79.1 | 77.8 | 77.5 | 76.8 | 78.1 |

| 13 | 79.3 | 78.5 | 78.0 | 77.3 | 78.7 | 77.3 |

| 14 | 79.0 | 78.6 | 78.0 | 79.3 | 77.9 | 77.6 |

| 15 | 78.8 | 78.5 | 79.7 | 78.3 | 78.1 | 77.7 |

| 16 | 78.4 | 80.1 | 78.7 | 78.6 | 78.1 | 76.5 |

| 17 | 79.8 | 79.0 | 78.6 | 78.5 | 76.9 | 76.0 |

| 18 | 78.7 | 78.9 | 78.4 | 77.5 | 76.4 | 76.5 |

| 19 | 78.4 | 78.6 | 77.4 | 76.8 | 76.6 | 76.3 |

| 20 | 77.9 | 77.5 | 76.6 | 77.2 | 76.2 | 76.2 |

| Source: 2019 Longitudinal Immigration Database. | ||||||

Data on median earnings paint a different picture (Chart 4). As expected, median annual earnings were much lower among immigrants entering Canada during the recession (e.g., the 1991, 1992 and 1993 entering cohorts) than among the cohorts who entered prior to the recession in 1988 or 1989.Note However, this difference persisted over time. Even 20 years after entry, the recession cohort (1992 cohort) earned 13% less than the 1988 cohort. This result may be in part caused by differences in the observable characteristics of entering cohorts, or differences in economic conditions during various years. However, even after controlling for such factors,Note differences—although reduced—remained.Note For example, 20 years after landing, the earnings difference between the 1988 and 1992 cohorts was 7% rather than 13%.

Data table for Chart 4

| Years since admission | 1988 | 1989 | 1990 | 1991 | 1992 | 1993 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2018 dollars | ||||||

| 1 | 25,820 | 23,270 | 19,580 | 18,580 | 18,640 | 18,740 |

| 2 | 29,530 | 25,070 | 22,650 | 21,340 | 21,940 | 21,930 |

| 3 | 29,560 | 26,920 | 24,660 | 23,820 | 23,720 | 23,530 |

| 4 | 31,170 | 28,320 | 26,900 | 25,460 | 25,280 | 25,740 |

| 5 | 32,250 | 30,560 | 28,550 | 27,120 | 27,340 | 28,020 |

| 6 | 34,290 | 31,860 | 30,310 | 29,290 | 29,540 | 30,090 |

| 7 | 35,570 | 33,550 | 32,280 | 31,500 | 31,580 | 32,130 |

| 8 | 36,760 | 35,280 | 34,160 | 33,120 | 33,540 | 33,170 |

| 9 | 38,450 | 37,220 | 35,830 | 34,770 | 34,190 | 34,160 |

| 10 | 40,170 | 38,700 | 37,250 | 35,540 | 35,060 | 34,830 |

| 11 | 41,590 | 40,030 | 38,230 | 36,380 | 35,670 | 36,140 |

| 12 | 42,410 | 40,490 | 39,060 | 37,020 | 36,960 | 36,820 |

| 13 | 42,800 | 41,210 | 39,340 | 38,220 | 37,440 | 37,840 |

| 14 | 43,350 | 41,750 | 40,390 | 38,680 | 38,600 | 38,890 |

| 15 | 43,840 | 42,650 | 41,010 | 39,840 | 39,500 | 39,370 |

| 16 | 44,890 | 43,170 | 41,820 | 40,640 | 40,090 | 39,270 |

| 17 | 45,160 | 44,070 | 42,650 | 41,090 | 39,800 | 40,080 |

| 18 | 46,170 | 44,710 | 43,120 | 40,930 | 40,500 | 40,210 |

| 19 | 46,760 | 45,080 | 42,810 | 41,490 | 40,460 | 40,840 |

| 20 | 46,820 | 44,630 | 43,500 | 41,530 | 41,110 | 41,460 |

| Source: 2019 Longitudinal Immigration Database. | ||||||

Together, these results suggest that immigrants entering Canada during the early 1990s recession had a lower employment rate than immigrants entering prior to the recession, but this difference did not seem to persist several years after entry. Average annual earnings differences between pre-recession and recession cohorts did persist for many years afterward.

A similar analysis was conducted for immigrants landing in the years surrounding the 2008/2009 recession. Employment and earnings outcomes from up to 10 years after landing were examined for all entry cohorts admitted between 2006 and 2013. The results indicate that there was a continuous improvement in both employment rate and earnings from the 2006 cohort to the 2013 cohort, both immediately after landing and after 10 years in Canada. This is consistent with earlier work indicating an improvement in entry earnings for immigrants over these years (Hou et al., 2020). There was no indication that the 2008 and 2009 landing cohorts experienced poorer longer-run outcomes than other cohorts in spite of their entering during a recession. This may be related to the fact that the recession was a relatively mild one and that, during this period, more economic immigrants were selected from among temporary foreign workers.

The relative outcomes of recent immigrants during the COVID-19 recession

It is too early to determine what long-term effects the COVID-19 recession will have on the economic outcomes of recent immigrants. However, their experience during the recession, relative to the Canadian born, can be addressed. Recent immigrants—particularly women—are overrepresented in the accommodation and food service sector and in lower-paying jobs, and tend to have shorter job tenureNote than the Canadian born. Recent immigrants often have difficulty transferring their educational and employment qualifications into positive labour market outcomes and finding steady work with a good salary. Thus, it is possible that recent immigrants were more negatively affected by the COVID-19 recession than Canadian-born individuals.

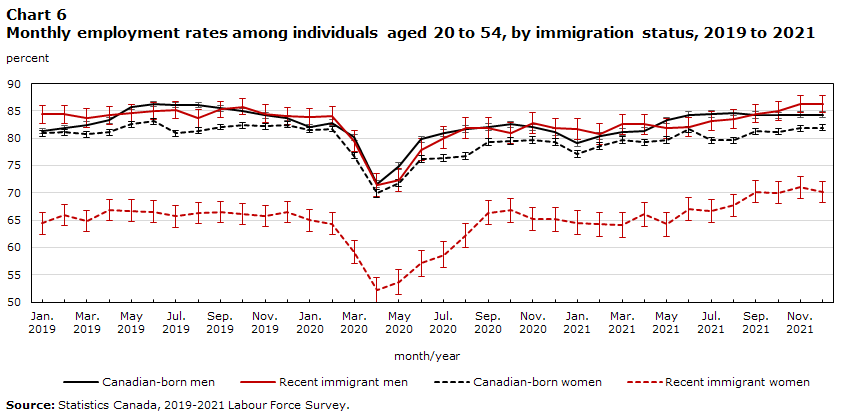

Female recent immigrants had poorer outcomes than their Canadian-born counterparts, with higher unemployment rates and lower employment rates, both prior to and during the recession. Male recent immigrants had employment and unemployment outcomes similar to those of the Canadian born (charts 5 and 6) during both periods. In terms of the relative change in these outcomes during the recession, results suggest a marginally greater effect on employment and unemployment rates for male recent immigrants (aged 20 to 54) than on their Canadian-born counterparts. Female recent immigrants experienced a greater differential effect regarding unemployment, as well as employment rates, mainly in May and June 2020.Note Overall, the differential effect of the COVID-19 recession on unemployment among female recent immigrants was significant, while it was relatively small among male recent immigrants.

Data table for Chart 5

| Canadian-born men | Recent immigrant men | Canadian-born women | Recent immigrant women | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| percent | Margin of error (percent) | percent | Margin of error (percent) | percent | Margin of error (percent) | percent | Margin of error (percent) | |

| 2019 | ||||||||

| January | 6.9 | 0.4 | 5.9 | 1.1 | 4.3 | 0.3 | 8.1 | 1.3 |

| February | 6.7 | 0.4 | 5.6 | 1.1 | 4.1 | 0.3 | 8.3 | 1.4 |

| March | 6.3 | 0.4 | 6.7 | 1.2 | 4.3 | 0.3 | 8.0 | 1.3 |

| April | 6.2 | 0.3 | 6.2 | 1.1 | 4.3 | 0.3 | 7.4 | 1.3 |

| May | 5.5 | 0.3 | 5.7 | 1.1 | 4.1 | 0.3 | 7.7 | 1.3 |

| June | 5.1 | 0.3 | 5.5 | 1.0 | 3.7 | 0.3 | 8.5 | 1.3 |

| July | 5.2 | 0.3 | 5.7 | 1.1 | 4.8 | 0.3 | 8.9 | 1.4 |

| August | 5.3 | 0.3 | 7.3 | 1.2 | 5.9 | 0.3 | 9.6 | 1.4 |

| September | 4.6 | 0.3 | 4.9 | 1.0 | 4.0 | 0.3 | 8.7 | 1.3 |

| October | 4.6 | 0.3 | 4.8 | 1.0 | 3.8 | 0.3 | 8.7 | 1.3 |

| November | 5.6 | 0.3 | 6.6 | 1.1 | 3.9 | 0.3 | 9.2 | 1.4 |

| December | 5.3 | 0.3 | 6.4 | 1.1 | 3.5 | 0.3 | 8.8 | 1.4 |

| 2020 | ||||||||

| January | 6.5 | 0.4 | 5.8 | 1.1 | 3.9 | 0.3 | 11.2 | 1.5 |

| February | 6.2 | 0.4 | 5.5 | 1.1 | 3.8 | 0.3 | 10.5 | 1.5 |

| March | 8.2 | 0.4 | 7.2 | 1.3 | 7.1 | 0.4 | 13.7 | 1.8 |

| April | 13.8 | 0.6 | 12.4 | 1.7 | 11.2 | 0.5 | 19.2 | 2.2 |

| May | 13.4 | 0.5 | 14.1 | 1.8 | 11.8 | 0.5 | 21.7 | 2.2 |

| June | 10.7 | 0.5 | 12.0 | 1.7 | 10.1 | 0.5 | 19.7 | 2.2 |

| July | 10.1 | 0.5 | 10.7 | 1.6 | 9.0 | 0.5 | 20.1 | 2.2 |

| August | 9.4 | 0.5 | 9.3 | 1.5 | 10.2 | 0.5 | 15.2 | 1.9 |

| September | 7.9 | 0.4 | 8.8 | 1.5 | 6.6 | 0.4 | 10.8 | 1.6 |

| October | 7.4 | 0.4 | 9.9 | 1.6 | 6.3 | 0.4 | 10.5 | 1.6 |

| November | 7.7 | 0.4 | 9.2 | 1.5 | 6.0 | 0.4 | 11.3 | 1.7 |

| December | 7.9 | 0.5 | 9.3 | 1.5 | 5.9 | 0.4 | 10.5 | 1.6 |

| 2021 | ||||||||

| January | 9.6 | 0.5 | 9.8 | 1.6 | 7.9 | 0.5 | 12.7 | 1.8 |

| February | 8.5 | 0.5 | 9.7 | 1.5 | 6.0 | 0.4 | 11.9 | 1.7 |

| March | 8.3 | 0.5 | 8.6 | 1.4 | 5.3 | 0.4 | 12.9 | 1.8 |

| April | 8.3 | 0.5 | 9.0 | 1.4 | 6.1 | 0.4 | 10.8 | 1.7 |

| May | 7.6 | 0.4 | 9.9 | 1.5 | 6.3 | 0.4 | 13.0 | 1.8 |

| June | 6.6 | 0.4 | 9.4 | 1.4 | 5.1 | 0.3 | 11.0 | 1.6 |

| July | 6.6 | 0.4 | 9.2 | 1.4 | 6.4 | 0.4 | 11.6 | 1.7 |

| August | 6.5 | 0.4 | 7.7 | 1.3 | 7.5 | 0.5 | 11.8 | 1.6 |

| September | 6.2 | 0.4 | 6.3 | 1.1 | 4.8 | 0.4 | 9.0 | 1.5 |

| October | 6.0 | 0.4 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 11.1 | 1.6 |

| November | 5.5 | 0.4 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 8.3 | 1.3 |

| December | 5.1 | 0.4 | 5.1 | 1.0 | 3.6 | 0.3 | 8.7 | 1.4 |

| Source: Statistics Canada, 2019-2021 Labour Force Survey. | ||||||||

Data table for Chart 6

| Canadian-born men | Recent immigrant men | Canadian-born women | Recent immigrant women | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| percent | Margin of error (percent) | percent | Margin of error (percent) | percent | Margin of error (percent) | percent | Margin of error (percent) | |

| 2019 | ||||||||

| January | 81.3 | 0.5 | 84.4 | 1.6 | 80.9 | 0.5 | 64.4 | 2.0 |

| February | 81.8 | 0.5 | 84.4 | 1.7 | 81.1 | 0.5 | 65.9 | 2.0 |

| March | 82.5 | 0.5 | 83.7 | 1.7 | 80.7 | 0.5 | 64.9 | 2.0 |

| April | 83.3 | 0.5 | 84.2 | 1.6 | 81.1 | 0.5 | 66.8 | 2.0 |

| May | 85.7 | 0.5 | 84.6 | 1.6 | 82.5 | 0.5 | 66.8 | 2.0 |

| June | 86.2 | 0.5 | 85.0 | 1.6 | 83.1 | 0.5 | 66.6 | 1.9 |

| July | 86.1 | 0.5 | 85.1 | 1.6 | 80.9 | 0.5 | 65.7 | 2.0 |

| August | 86.0 | 0.5 | 83.6 | 1.6 | 81.4 | 0.5 | 66.3 | 1.9 |

| September | 85.5 | 0.5 | 85.3 | 1.5 | 82.0 | 0.5 | 66.6 | 1.9 |

| October | 84.9 | 0.5 | 85.8 | 1.5 | 82.3 | 0.5 | 66.1 | 1.9 |

| November | 84.2 | 0.5 | 84.5 | 1.6 | 82.1 | 0.5 | 65.7 | 1.9 |

| December | 83.7 | 0.5 | 84.0 | 1.6 | 82.5 | 0.5 | 66.5 | 1.9 |

| 2020 | ||||||||

| January | 82.0 | 0.5 | 83.9 | 1.6 | 81.5 | 0.5 | 65.0 | 2.0 |

| February | 82.9 | 0.5 | 84.1 | 1.6 | 81.7 | 0.5 | 64.3 | 2.0 |

| March | 80.1 | 0.6 | 79.5 | 1.8 | 76.8 | 0.6 | 59.2 | 2.2 |

| April | 71.5 | 0.7 | 71.4 | 2.1 | 69.9 | 0.7 | 52.2 | 2.3 |

| May | 75.0 | 0.6 | 72.4 | 2.1 | 71.9 | 0.7 | 53.6 | 2.3 |

| June | 79.8 | 0.6 | 77.9 | 2.0 | 76.2 | 0.6 | 57.1 | 2.3 |

| July | 80.9 | 0.6 | 80.1 | 2.0 | 76.3 | 0.6 | 58.7 | 2.3 |

| August | 81.6 | 0.6 | 81.8 | 1.9 | 76.7 | 0.6 | 62.2 | 2.3 |

| September | 82.0 | 0.6 | 81.9 | 1.9 | 79.3 | 0.6 | 66.4 | 2.2 |

| October | 82.5 | 0.6 | 80.9 | 1.9 | 79.5 | 0.6 | 66.8 | 2.2 |

| November | 82.0 | 0.6 | 82.8 | 1.8 | 79.6 | 0.6 | 65.2 | 2.2 |

| December | 81.1 | 0.6 | 81.8 | 1.8 | 79.3 | 0.6 | 65.1 | 2.2 |

| 2021 | ||||||||

| January | 79.1 | 0.6 | 81.7 | 1.9 | 77.0 | 0.6 | 64.6 | 2.3 |

| February | 80.3 | 0.6 | 80.8 | 1.9 | 78.6 | 0.6 | 64.2 | 2.2 |

| March | 81.1 | 0.6 | 82.5 | 1.8 | 79.6 | 0.6 | 64.1 | 2.2 |

| April | 81.3 | 0.6 | 82.5 | 1.8 | 79.2 | 0.6 | 66.1 | 2.2 |

| May | 83.3 | 0.6 | 81.8 | 1.8 | 79.7 | 0.6 | 64.2 | 2.2 |

| June | 84.3 | 0.5 | 82.0 | 1.7 | 81.6 | 0.6 | 67.1 | 2.1 |

| July | 84.4 | 0.6 | 83.1 | 1.8 | 79.6 | 0.6 | 66.6 | 2.1 |

| August | 84.7 | 0.6 | 83.5 | 1.7 | 79.6 | 0.6 | 67.7 | 2.1 |

| September | 84.2 | 0.6 | 84.5 | 1.6 | 81.3 | 0.6 | 70.2 | 2.0 |

| October | 84.2 | 0.5 | 85.0 | 1.7 | 81.2 | 0.6 | 70.0 | 2.0 |

| November | 84.3 | 0.5 | 86.2 | 1.6 | 81.8 | 0.6 | 71.0 | 2.0 |

| December | 84.3 | 0.6 | 86.3 | 1.6 | 81.9 | 0.6 | 70.2 | 2.0 |

| Source: Statistics Canada, 2019-2021 Labour Force Survey. | ||||||||

An earlier study examined the transition rate at which workers left and entered employment during the downturn and recovery (Hou et al., 2020). The monthly transition rate of employment to non-employment is the share of individuals employed in one month who are not employed the following month. Prior to the lockdown, this rate was low and similarNote for both recent immigrants and the Canadian born. Early in the pandemic, it jumped to 17% among recent immigrants, compared with 13% among the Canadian born. By the end of 2020, the rate had returned to the approximate pre-recession level, around 4% for both groups. The rate of transition out of employment was highest among recently immigrated women, reaching 20% in April 2020, which was 7 percentage points higher than that of Canadian-born women. Statistical analysis indicated that this gap was largely caused by the over-representation of recently immigrated women in lower-wage jobs, shorter tenure jobs, and being employed in the accommodation and food services sectors.Note

In addition to leaving employment at a higher rate, recent immigrants also returned to employment at a lower rate during the initial period of recoveryNote (Hou et al., 2020). Again, movement into employment during the early recovery was lowest among recently immigrated women, lower than for Canadian-born women. This difference was driven by differential employment growth between recent immigrant and Canadian-born women within industrial sectors (notably accommodation and food services) and low-wage jobs.

Summary

This paper documents the labour market outcomes of immigrants relative to the Canadian born during the past three recessions, which were different in their severity and duration. The early 1990s recession was the most severe, with employment at below pre-recession levels for over four years. That of 2008/2009 was much less severe and employment effects lasted just over two years. In both recessions, it was the good-producing sector that was hit the hardest, notably manufacturing and construction. As a result, men, younger workers, the less educated, and workers with low seniority were impacted the most. The COVID-19 downturn was very different, as it was the result of a government-induced shutdown to curb the pandemic. Employment loss was swift and significant, but short lived relative to the earlier two recessions. The services sector was affected most severely, notably food and accommodation services and retail trade. By consequence, low-wage workers carried the burden of the decline, along with the less educated, and young women.

The more severe early 1990s recession had a much greater negative differential impact on recent immigrants than did that of 2008/2009 or of COVID-19. The 2008/2009 recession had little differential effect between recent immigrants and the Canadian born on employment rates and earnings. An earlier study did document a somewhat greater rise in unemployment rate among recent immigrants (Kelly et al. 2011). There was also evidence of a possible, significant scarring effect on the future earnings of immigrants that entered Canada during the early 1990s recession. There was little evidence of such an effect during the 2008/2009 recession.

At the trough of the COVID-19 downturn, female recent immigrants experienced a greater increase in unemployment rate than did their Canadian-born counterparts. This outcome was caused in part by a greater rise in the rate of transition out of employment during the downturn, which was in turn largely caused by the over-representation of recently immigrated women in lower-wage jobs with shorter tenure and in the accommodation and food services sectors. However, these differential effects were short lived. By eight months to one year into the recession, they had largely disappeared. There was little difference between male recent immigrants and their Canadian-born counterparts regarding the effect of the COVID-19 recession on employment and unemployment rates.

It is too early to tell whether the COVID-19 recession will have scarring effects on immigrant labour market outcomes. While unemployment increases were significant, they did not reach the levels observed during the early 1990s and were more short lived. On the other hand, long-duration unemployment, which may drive scarring more than short spells of unemployment, grew much faster and to higher levels during the COVID-19 recession than during two earlier recessions.Note

References

Abbott, M., & Beach, C. (2011). Immigrant earnings differences across admission categories and landing cohorts in Canada. [CLSSRN working paper]. University of British Columbia.

Aydemir, A. (2003). The effects of the business cycle on labour market assimilation of immigrants. (Analytical Studies Branch Research Paper Series, No. 203). Statistics Canada.

Borland, J. (2020). Scarring effects: A review of a stroke and an international literature. The Australian Journal of labour economics 23(2), 173–187.

Chan, W., Morissette, R., & Frenette, M. (2011). Workers laid off during the last three recessions: Who where they and how did they fare? (Analytical Studies Branch Research Paper Series, No. 337). Statistics Canada.

Cross, P. (2011). How did the 2008–2010 recession and recovery compare with previous cycles? The Canadian Economic Observer, January. Statistics Canada.

Dustmann, C., Glitz, A., & Vogel, T. (2010). Employment, wages, and the economic cycle: differences between immigrants and natives. The European Economic Review, 54, 1–17.

Gilmore, J., & Larochelle-Cote, S. (2011). Inside the Labour Market Downturn. Perspectives on Labour and Income, Spring 2011. Statistics Canada.

Hou, F., & Crossman, E., & Picot, G. (2020). Two-step immigrant selection: recent trends in immigrant labour market outcomes. (Economic Insights No. 113). Statistics Canada.

Hou, F., & Picot, G. (2014). Annual levels of immigration and immigrant entry earnings. Canadian Public Policy 40(2),166–181.

Hou, F., Picot, G., & Zhang, J. (2020). Transitions into and out of employment by immigrants during the COVID-19 lockdown and recovery. (Catalogue No. 4528000). Statistics Canada.

Kelly, P., Park S., & Lepper, L. (2011). Economic recession and immigrant labour market outcomes in Canada, 2006–2011. (Analytical Report No. 22). Toronto Immigrant Employment Data Initiative.

Mask, J. (2018). The consequences of immigrating during a recession: evidence from the U.S. refugee resettlement program. The Munich Personal RePEc Archives Paper No. 90456.

Orrenius, P.M., & Zavodny, M. (2009). Tied to the business cycle: How immigrants fare in good and bad economic times. The Migration Policy Institute. United States.

Rothstein, J. (2020). The lost generation? Labour market outcomes for post-great recession entrants. (NBER Working Paper Series, No. 27516).

Statistics Canada. (2020). The economic impacts and recovery related to the pandemic. (Statistics Canada catalogue number 11–631—X).

Statistics Canada. (2021). The Labour Force Survey Release for March. (Statistics Canada, April).

Tumino, A. (2015). The scarring effect of unemployment from the early ’90s to the great recession. Institute for Social and Economic Research Working Paper No. 2015 – 05.

- Date modified: