Indigenous Peoples Survey: First Nations children living off reserve, Métis children and Inuit children and their families, 2022

Released: 2024-08-14

A new report, "First Nations children living off reserve, Métis children, and Inuit children and their families: Selected findings from the 2022 Indigenous Peoples Survey," provides key insights into the well-being of Indigenous children using new data from the 2022 Indigenous Peoples Survey (IPS), a national voluntary post-censal survey which, in this sixth cycle, focused on children and families. The report showcases the breadth of the survey, providing an overview of select findings on the well-being and health of First Nations children living off reserve, Métis children and Inuit children aged 1 to 14 years.

Recent and culturally relevant data on Indigenous children have constituted a significant data gap. The 2022 IPS helps to fill this gap with information on living arrangements, child care and Indigenous languages and cultures, while also providing essential information on outcomes related to education, employment, housing, mobility, health and access to services.

Family members support First Nations, Métis and Inuit children to understand their culture and history, with schools also playing a role

Child development experts assert that fostering positive self-identity, tied to cultural connection and sense of belonging, makes for healthier children and adults. However, the history of colonization in Canada and the effects of residential schools have had a profoundly negative impact on Indigenous cultures and languages.

In 2022, parents and grandparents were the most commonly cited supports for First Nations, Métis and Inuit children to understand their culture and history. Among children aged 6 to 14 years, 67% of Inuit children, 58% of First Nations children living off reserve and 49% of Métis children had a parent who helped them understand First Nations, Métis and Inuit culture and history. In addition, 46% of Inuit children, 36% of First Nations children living off reserve and 23% of Métis children had a grandparent or great-grandparent to help them understand their culture and history.

Schools can also play a role in exposing children to First Nations, Métis and Inuit cultures, including Indigenous languages. Nationally, 29% of First Nations children living off reserve and 14% of Métis children aged 6 to 14 years were taught an Indigenous language at school in 2022. Within Inuit Nunangat (the Inuit homeland), 92% of Inuit children aged 6 to 14 years were taught an Indigenous language at school compared with 12% of school-aged Inuit children living outside Inuit Nunangat.

In 2022, almost three-quarters of parents of First Nations children living off reserve (72%) and Métis children (73%) reported strongly agreeing that their child's school supports Indigenous culture. Among parents of Inuit children, 80% strongly agreed (93% for Inuit children living inside Inuit Nunangat and 51% for those living outside Inuit Nunangat).

Child care providers play a role in exposing children to Indigenous cultures

In 2022, half (51%) of Indigenous children aged 1 to 5 years (excluding those living on reserve) received regular child care (56% of Métis children, 49% of First Nations children living off reserve and 36% of Inuit children). "Child care" means any care for children by someone other than the parent or guardian, both formal and informal. This does not include occasional babysitting or kindergarten.

In comparison, 64% of non-Indigenous children aged 1 to 5 years were in child care in Canada in 2023 (according to the Canadian Survey on Early Learning and Child Care, 2023).

In 2022, among children participating in regular child care, 49% of First Nations children living off reserve, 30% of Métis children and 64% of Inuit children were reported as being in a child care arrangement that provided an environment that encourages learning about traditional and cultural Indigenous values and customs.

Most parents of young Indigenous children rate speaking and understanding an Indigenous language as important, but fewer think their child will be fluent

Research has shown that language is connected to cultural identity, sense of belonging, health and well-being. In 2022, two-thirds (67%) of parents of Indigenous children aged 1 to 5 years reported it being very or somewhat important for their children to speak or understand an Indigenous language, up from less than half (48%) in 2006.

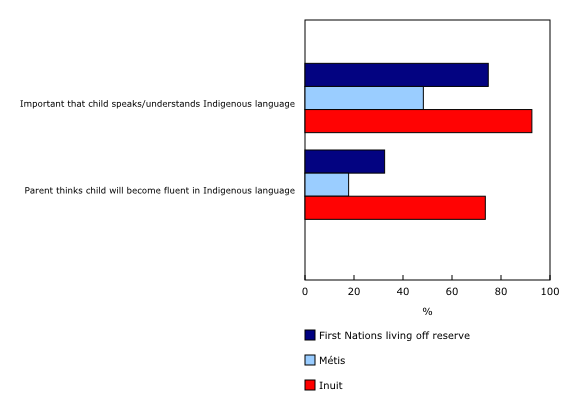

However, in 2022, a higher percentage of parents reported it being very or somewhat important for their child to speak and understand an Indigenous language compared with the percentage of parents who reported thinking their child will become fluent (Chart 1).

These gaps between parental aspirations and predictions of their children's future fluency in an Indigenous language may suggest that parents, while committed to the passing down of Indigenous languages to future generations, perceive obstacles in doing so.

Many Indigenous children live in households facing serious socioeconomic challenges

In 2022, 45% of parents of Indigenous children aged 1 to 14 years (excluding those living on reserve) reported their household income as being insufficient to cover an unexpected expense of $500, and 31% reported their household income as being not enough to meet their household needs for transportation, housing, food, clothing and other necessary expenses.

Among First Nations children living off reserve, in 2022, 47% of parents could not cover an unexpected expense of $500 (50% in urban areas compared with 39% in rural areas), and 32% reported their household income as being not enough to meet their needs.

In 2022, about two in five parents of Métis children (39%) reported being unable to cover an unexpected expense of $500, and just over one-quarter (27%) reported their household income as being not enough to meet their needs.

Among parents of Inuit children, 53% reported being unable to cover an unexpected expense of $500 in 2022. The proportion was significantly higher for parents of Inuit children living inside Inuit Nunangat (62%) than for those living outside Inuit Nunangat (30%). In addition, 43% of parents of Inuit children reported their household income as being not enough to meet their household needs.

Over two in five Indigenous children aged 1 to 14 years live in food insecure households

In 2022, 41% of Indigenous children aged 1 to 14 years (excluding those living on reserve) were living in food insecure households. Specifically, 9% lived in a marginally food insecure household (families worried about running out of food), 19% lived in moderately food insecure households (quality/quantity of food is compromised) and 14% lived in severely food insecure households (missing meals, reducing food intake and, in some cases, going without food) (Table 1). In 2019, the most recent year for which data are available, 16% of non-Indigenous children aged 1 to 14 years were living in food insecure households (according to the Canadian Health Survey on Children and Youth, 2019).

Food insecurity is a well-documented problem among Inuit, especially for those living in Inuit Nunangat due to the challenges of food access, high food costs and climate change. In 2022, more than three-quarters (77%) of Inuit children in Inuit Nunangat lived in households that experienced food insecurity, compared with 35% of their counterparts living outside Inuit Nunangat.

Most Indigenous children aged 1 to 14 years have seen a dental professional and are up to date on routine vaccinations

While results show that Indigenous children experience some challenges related to their oral health, in 2022, the majority (87%) of Indigenous children aged 1 to 14 years had seen a dental professional (dentist or dental hygienist) at some point. Older children aged 6 to 14 years (97%) were more likely to have seen a dental professional than younger children aged 1 to 5 years (65%).

In Canada, publicly funded, routine vaccinations for children are recommended against several diseases. In 2022, nearly all (94%) Indigenous children aged 1 to 14 years had received their routine (regular) vaccinations; the proportions were similar for Indigenous children aged 1 to 5 years (93%) and those aged 6 to 14 years (95%).

However, in 2022, 11% of Indigenous children aged 1 to 14 years (excluding those living on reserve) experienced a time in the previous 12 months when they needed health care but did not receive it. The proportions that reported having unmet health care needs were similar for Indigenous children aged 1 to 5 years (12%) and those aged 6 to 14 years (11%).

Among children who did not receive care, the most common reasons cited by parents of First Nations children living off reserve and Métis children in 2022 were long wait times and that care was not available at the time required. For Inuit children, the top cited reasons were that care was not available in the area and that care was not available at the time required.

Based on parents' perception, more than two-thirds of Indigenous children aged 1 to 14 years have excellent or very good mental health

It is important to examine the mental health status of children, as emotional and social development in early years can lay the foundation for mental health throughout life.

In 2022, just over two-thirds (69%) of Indigenous children aged 1 to 14 years (excluding those living on reserve) were reported by their parent as having excellent or very good mental health. Specifically, the proportions were 68% for First Nations children living off reserve, 70% for Métis children and 72% for Inuit children. The corresponding proportion for non-Indigenous children was 86% (according to the Canadian Health Survey on Children and Youth, 2019).

Did you know we have a mobile app?

Download our mobile app and get timely access to data at your fingertips! The StatsCAN app is available for free on the App Store and on Google Play.

Note to readers

The Indigenous Peoples Survey (IPS) sample is selected from the Census of Population respondents, making it a postcensal survey. For methodological details, see Indigenous Peoples Survey (IPS).

This release features analysis based on data from the 2022 IPS. The 2022 IPS is a national survey of the Indigenous identity population aged 1 year and older living in private dwellings, excluding people living on Indian reserves and settlements. The 2022 IPS represents the sixth cycle of the survey and focused on Indigenous children and their families. This cycle of the IPS was conducted from May 11, 2022, to November 30, 2022, with in-person follow up occurring from January 16, 2023, to March 31, 2023.

For respondents under the age of 15, the person most knowledgeable about the respondent was asked to complete the survey on their behalf. For the purposes of this release, the term "parent(s)" is used to refer to the person most knowledgeable.

This analysis includes differences between estimates that are statistically significant at the 95% confidence level.

New IPS data tables are also available, including tables on food security status (41100063), meeting basic needs and unexpected expenses (41100061), as well as regular child care use (41100064).

Products

The study "First Nations children living off reserve, Métis children, and Inuit children and their families: Selected findings from the 2022 Indigenous Peoples Survey" (89-653-X) is now available.

The product "Concepts and Methods Guide for the Indigenous Peoples Survey and Indigenous Peoples Survey – Nunavut Inuit Supplement, 2022," (89-653-X) is now available.

Contact information

For more information, or to enquire about the concepts, methods or data quality of this release, contact us (toll-free 1-800-263-1136; 514-283-8300; infostats@statcan.gc.ca) or Media Relations (statcan.mediahotline-ligneinfomedias.statcan@statcan.gc.ca).

- Date modified: