Intersectional Gender Wage Gap in Canada, 2007 to 2022

Released: 2023-09-21

This release looks at the gender wage gap and how it varies across groups of women, and how it changed from 2007 to 2022. The results are for paid workers aged 20 to 54 years. It uses data from the Labour Force Survey to examine the experiences of Indigenous women, immigrant women and non-Indigenous women born in Canada.

While men still earn more than women, this gap continued to narrow from 16% in 2007 to 12% by 2022 among paid workers aged 20 to 54 years. However, women from diverse groups—namely Indigenous women living off-reserve, non-Indigenous Canadian-born women, immigrant women who landed in Canada in childhood (at the age of 18 years or younger) and those who landed in adulthood (older than 18 years)—experience the gender wage gap differently.

This release defines the gender wage gap as the difference between hourly wages of non-Indigenous Canadian-born men and of women from different groups expressed as a proportion of Canadian-born men's hourly wages. In the rest of this release, "Canadian-born" refers to non-Indigenous workers born in Canada.

When compared with Canadian-born men, wage gaps in 2022 were largest for immigrant women who landed as adults (21%) and Indigenous women (20%) and were smallest for immigrant women who landed as children (11%) and Canadian-born women (9%).

A new study released today aims to understand the differences in hourly wages among diverse groups of women compared with those of Canadian-born men. This study, titled "Intersectional Perspective on the Canadian Gender Wage Gap," uses data from the Labour Force Survey to analyze how the gender wage gap among paid workers aged 20 to 54 years evolved for diverse groups of women from 2007 to 2022.

The gender wage gap narrows since 2007

The gender wage gaps narrowed the most for the groups facing the largest gaps. The gaps for Indigenous women and immigrant women who landed as adults each narrowed by 7 percentage points. The gap for Canadian-born women narrowed by 6 percentage points and that for immigrant women who landed as children narrowed by 4 percentage points.

Along most dimensions, Canadian-born women face smaller gaps than Indigenous and immigrant women

Not all women experience the same life transitions or experience them in the same way, and consequently, differences emerge in the gender pay gaps they face.

While the gender wage gap has declined in most age groups since 2007, the age at which the most dramatic improvements occurred differed across the groups of women. The wage gap experienced by older Canadian-born women (aged 45 to 49 years) narrowed from 21% in 2007 to 14% in 2022. In addition, the wage gap for young Indigenous women (aged 20 to 24 years) narrowed from 20% in 2007 to 8% in 2022. The wage gap improved the most for immigrant women aged 25 to 29 years. In 2022, for immigrant women who landed as children, the wage gap was non-existent, while it was 11% in 2007. For immigrant women who landed as adults, it narrowed from 31% in 2007 to 12% in 2022.

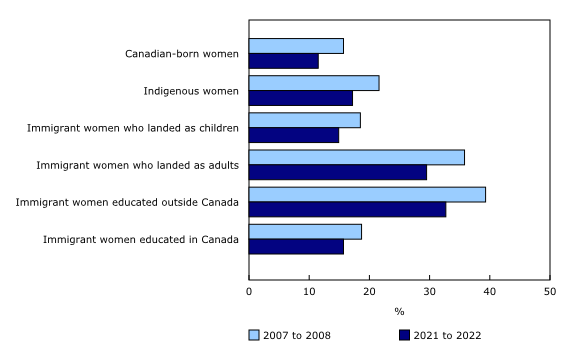

Higher education is associated with smaller wage gaps, but this varied by group. Among paid workers with a bachelor's degree or higher in 2022, the gender wage gap was 12% for Canadian-born women compared with 15% for immigrant women who landed as children, 17% for Indigenous women and 30% for immigrant women who landed as adults. Immigrant women who obtained their credentials outside Canada (33%) faced larger wage gaps than those educated in Canada (16%).

Gender wage gaps are larger among full-time workers than among those working part time. In 2022, among full-time workers, the gender wage gaps faced by Indigenous women (18%) and immigrant women who landed in Canada as adults (20%) were about twice as large as those faced by Canadian-born women (8%) and immigrant women who landed as children (10%). Among part-time workers, Canadian-born women out earned Canadian-born men by 7%, likely because of their higher incidence in professional occupations in health, education and government. In contrast, Canadian-born men earned more than Indigenous women (by 9%) and immigrant women who landed as adults (by 7%). These women are concentrated in the same low-wage industries and occupations as men, as well as in support occupations in business and health.

Gender wage gaps are smaller among men and women who do not live in a couple and do not have any children, and they are larger when the presence and age of children are considered. When men and women do not live in a couple and do not have children, Canadian-born women earned 3% less than Canadian-born men, immigrant women who landed as children earned 2% less, immigrant women who landed as adults earned 6% less and Indigenous women earned 13% less. Larger gaps were observed among couples with young children (aged 0 to 5 years), especially for Indigenous women (25%) and immigrant women who landed as adults (30%). These gaps have narrowed since 2007.

Factors accounting for the narrowing pay gap

A key factor in the convergence was that women from all groups continued to improve their labour market qualifications.

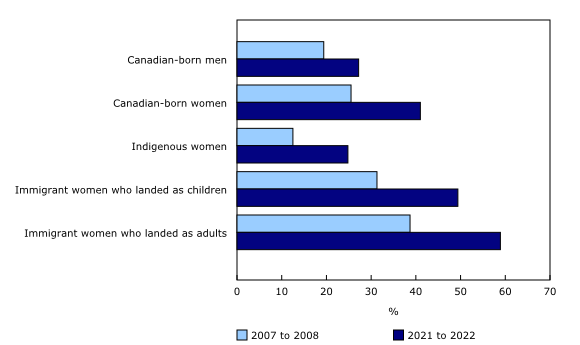

While men and women have become more educated since 2007, the educational attainment of women from most groups surpassed that of men, and this difference has grown. In 2022, the proportion of Canadian-born men (27%) with a bachelor's degree continued to be lower than the comparable proportions of immigrant women who landed as adults (59%), immigrant women who landed as children (49%) and Canadian-born women (41%). The proportion of Indigenous women in the workforce with a bachelor's degree or higher almost doubled, from 13% in 2007 to 25% in 2022.

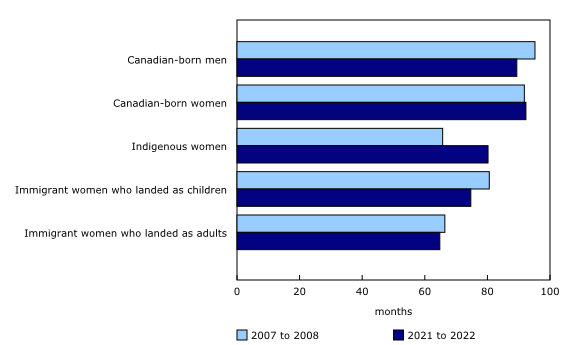

There is little difference between the length of time Canadian-born men and Canadian-born women have worked for their current employer. However, Canadian-born women typically have longer job tenure than Indigenous women (by 12 months), immigrant women who landed as children (by 18 months) and immigrant women who landed as adults (by 28 months). The average job tenure of Indigenous women has increased by 15 months since 2007, likely the result of a smaller proportion of them being employed in short-term jobs of less than one year in 2022 (22%) than in 2007 (30%).

Another key factor in the convergence was that women from all groups held different types of jobs.

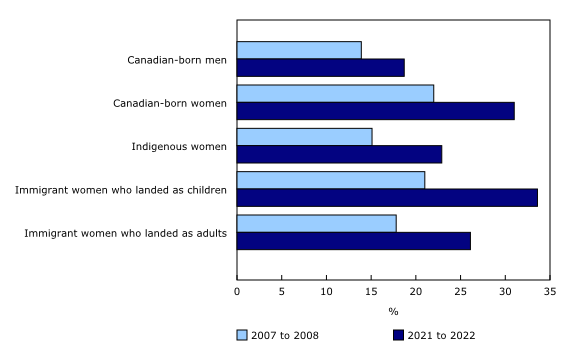

In 2022, Canadian-born women (31%) and immigrant women who landed as children (34%) were more likely to work in professional occupations than Indigenous women (23%) and immigrant women who landed as adults (26%). These differences have grown since 2007.

Employment in jobs covered by collective bargaining agreements also differed. In 2022, 39% of Canadian-born women and 37% of Indigenous women worked in these jobs compared with about 28% of all immigrant women. These differences are mainly attributable to immigrant women's over-representation in the private sector, where coverage rates are typically lower.

The concentration of women within specific industries and occupations also contributed to the gender pay gap. Women's representation in low-wage jobs was not equal among all groups. Indigenous women (36%) and immigrant women who landed as adults (35%) were more likely to work in the five lowest-paid occupations than Canadian-born women (26%) and immigrant women who landed as children (28%). At the same time, women from all groups reduced their concentration in sales, service and administrative support occupations. About half of Indigenous women and Canadian-born women worked in health care and social assistance, educational services and retail trade industries. Immigrant women who landed as children (21%) were more likely to work in professional, scientific and technical service industries and finance and insurance than Canadian-born women (14%).

These factors suggest that the changing composition of the labour force and differences in job characteristics play a role in reducing the pay gap between Canadian-born men and women from diverse groups.

In fact, compositional changes accounted for most of the narrowing of the wage gap. Women's relative improvement in educational attainment, longer job tenure and having full-time employment explained the narrowing of the gap, ranging from 20% for Canadian-born women to 28% for immigrant women who landed as children. Changes in industry and occupation also largely explained the narrowing in the gender wage gap, ranging from 31% for Indigenous women to 74% for immigrant women who landed as adults.

More progress made at the lower end of the wage distribution than at the upper end

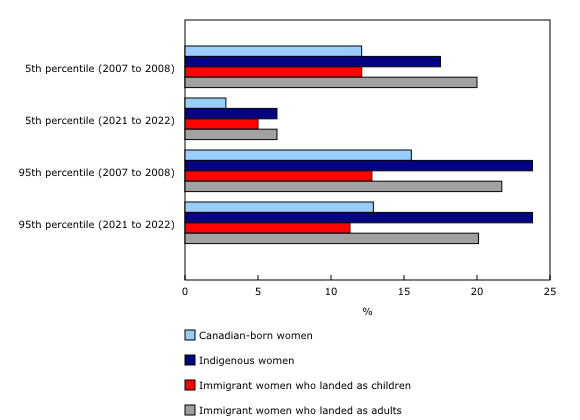

At the lower end of the pay distribution (5th percentile), Canadian-born women earned 3% less than Canadian-born men in 2022, compared with 12% less in 2007. Similar numbers were reported for immigrant women who landed as children. At this point, the wage gap for Indigenous women narrowed by 11 percentage points from 18% in 2007 to 6% in 2022. For immigrant women who landed as adults, their wage gap narrowed by 14 percentage points, from 20% in 2007 to 6% in 2022.

At the upper end of the pay distribution (95th percentile) in 2022, Indigenous women (24%) and immigrant women who landed as adults (20%) faced larger wage gaps than Canadian-born women (13%) and immigrant women who landed as children (11%). This is little changed from 2007.

Rising employment rates slow the narrowing of the gender wage gap

Employment rates vary across diverse groups of women and have changed at different rates since 2007. To examine the impact of changing employment rates on the gender wage gap, wages are linked to a consistent mix of characteristics at different points in time.

The gap narrowed more than previously reported, by an additional 6 percentage points for Indigenous women, 3 percentage points for immigrant women who landed as adults, and 1 percentage point each for Canadian-born women and immigrant women who landed as children.

Note to readers

This release uses data from the Labour Force Survey (LFS) from 2007 to 2022. The LFS is a monthly household survey collecting information about the labour market activities of the population aged 15 years and older, excluding residents of collective dwellings, persons living on reserves and other settlements in the provinces, and full-time members of the Canadian Forces.

The analytical sample includes paid workers aged 20 to 54 years living in one of the provinces, excluding full-time students, unpaid family members and non-permanent residents.

Women's average hourly wage rate is significantly less than men's (p < 0.05) for each group and in each year unless otherwise indicated.

Definitions

In this article, the wage gap is calculated on an hourly wage basis, and this differs from measures of the earnings gap. The gender wage gap refers to the difference between hourly wages of Canadian-born men and of women from different groups expressed as a proportion of Canadian-born men's hourly wages.

Products

The article entitled "Intersectional Perspective on the Canadian Gender Wage Gap" is now available in Studies on Gender and Intersecting Identities (45200002), and the infographic entitled "Intersectional perspective on the gender wage gap in Canada, 2007 to 2022" (11-627-M) is also available.

Contact information

For more information, or to enquire about the concepts, methods or data quality of this release, contact us (toll-free 1-800-263-1136; 514-283-8300; infostats@statcan.gc.ca) or Media Relations (statcan.mediahotline-ligneinfomedias.statcan@statcan.gc.ca).

- Date modified: