Police-reported family violence in Canada, 2020

Archived Content

Information identified as archived is provided for reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It is not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards and has not been altered or updated since it was archived. Please "contact us" to request a format other than those available.

Released: 2021-11-04

With the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in Canada, lockdown measures and safety protocols led to heightened concern about family violence. According to recent reports from the United Nations, several factors that might be experienced in a lockdown situation—including increased economic stressors, higher exposure to toxic or abusive relationships, and reduced access to formal and informal supports—could lead to an increased risk of family violence.

Monitoring the level of violence experienced in and outside the home is important to understand risk factors and identify vulnerable populations. However, due to reduced access to external support systems and public health guidance that recommended limited contact with those outside the immediate household, monitoring has become much more difficult in the context of the pandemic. For many, regular contact with others is critical to the detection, intervention and prevention of potential incidents of family violence.

In Canada, 8% of Canadians who participated in a web panel survey conducted during the early months of the pandemic reported that they were very or extremely concerned about the possibility of violence in the home. This proportion was higher for women (10%) than for men (6%). In addition, about one-third (32%) of people were very or extremely concerned about family stress resulting from lockdown.

Police-reported violent crime during the pandemic

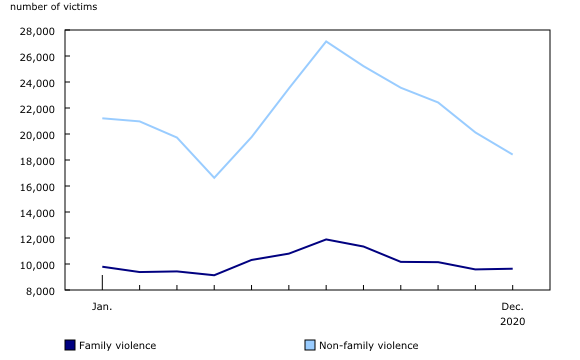

Despite researchers and victim service providers' having expressed concerns over increasing levels of violence in the home during periods of COVID-19 restrictions, police-reported data did not reveal a notable increase in 2020. Compared with 2019, the number of victims of police-reported family violence increased slightly (+1.5%) in 2020, while there was a 4% decrease in the number of victims of non-family violence.

While these year-over-year changes show broader annual trends, the monthly data as reported by the police throughout 2020 can reveal shorter-term fluctuations in police-reported crime. The following analysis looks at police-reported violent crime during four distinct time periods: prior to pandemic restrictions (January and February 2020), during the introduction of restrictions (March to May 2020), through the summer months when many restrictions were eased (July and August 2020), and through the fall and winter months as many jurisdictions reintroduced restrictions (September to December 2020). Comparing police-reported violent crime during these four time periods to their corresponding periods in 2019 allows for a more detailed review of year-over-year changes at various points of the pandemic.

As lockdown restrictions were put in place from March to May 2020, overall police-reported violent crime decreased considerably. The number of police-reported victims during these months was lower than that recorded in January and February 2020―before restrictions were imposed―and reached below numbers seen from March to May 2019. The relatively low numbers of victims reported by police during the lockdown months were then followed by an increase in victims of violence in July and August 2020, for both family and non-family violence, as some restrictions were eased. Compared with the same period in 2019, violent crime was also higher through the summer months.

The overall 4% annual decrease seen in non-family police-reported violence between 2019 and 2020 may be related to the fact that violence perpetrated by people other than family members—such as casual acquaintances, strangers or business associates—often occur when people are in public, outside of the home. As such, as pandemic restrictions reduced the time people spent in public and their contact with people outside of their household, violence perpetrated by non-family decreased. When restrictions were eased and people resumed public activities, non-family violence began to rise above the levels reported in the previous year.

Police-reported family violence in the context of the pandemic

Pandemic restrictions meant that many individuals spent more time at home with family members, often working from home and participating in virtual learning. Many experienced heightened stress due to social isolation, economic uncertainty, and other factors. Together, these factors led researchers and victim service providers to expect a significant increase in family violence during the period of restrictions.

Like overall violent crime, during the early months of the pandemic, the number of police reports of family violence declined. Declines were generally noted through March, April and May as restrictions were imposed, and the decline was larger for women than men. For instance, in April 2020, police reported 9% fewer women and 4% fewer men who were victims of family violence compared with April 2019.

The decline in police-reported family violence could be interpreted several ways, and police-reported data do not allow for a single, definitive interpretation. For instance, restrictions imposed in the context of the pandemic may have meant victims had less opportunity to report (as they were living with their abuser or reduced their interaction with people outside the home who would otherwise have either encouraged victims to report violence or reported violence to authorities themselves). Real or perceived pandemic considerations, such as a fear of exposure to COVID-19 at shelters or a belief that certain services or facilities were unavailable, may also have contributed to the decline.

Police-reported family violence in Canada's three largest police jurisdictions

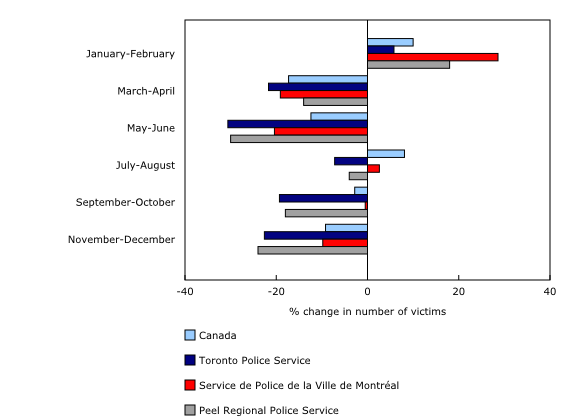

Underlying these broad national patterns is the reality that COVID-19 restrictions varied across regions. Some areas experienced school closures and curfews, while others experienced fewer or no restrictions that affected daily life.

In addition to the national picture, data from Canada's three largest municipal police services—Toronto Police Service, Peel Regional Police Service and Service de Police de la Ville de Montréal—which police densely populated areas and experienced several different restrictions, were analyzed. While not necessarily representative of experiences across Canada, these three police services were selected to illustrate the potential impacts of restrictions on trends in police-reported crime at a more local level. Due to their large size, these police services also had sufficient data to examine potential trends by month.

Data from these three police services show, on the whole, similar patterns. Compared with 2019, year-over-year declines were noted for police-reported family violence at the beginning of the pandemic, before returning to levels similar to those seen prior to the pandemic through the summer months, and reaching lower levels than the previous year again toward the end of 2020 as many restrictions were reintroduced in these three areas.

For example, the number of victims of family-related violence in April 2020 was considerably lower than in April 2019 in the municipalities of Toronto (-30%), Peel (-18%) and Montréal (-16%). These decreases, though notable, were substantially smaller than what was observed with non-family violence (-38%, -35% and -41%).

Family-related homicide in 2020

As with crime in general, there is no single factor that can explain variations in the prevalence of homicide, though increased tension or strain on individuals and households as the result of the pandemic and associated restrictions, and less ability to escape increasingly violent situations, could be factors. Homicide counts, which are included in the overall measure of police-reported violent crime, are also less likely to be impacted by changes in reporting behaviour. Homicide also represents the most serious manifestation of violence.

There were 56 more homicides in Canada in 2020 than in 2019, with increases noted in homicides committed by non-spousal family members (+11) and non-spousal intimate partners (+7). At the same time, there was a decrease in homicides committed by a spouse (-9). Non-family homicides also increased, with more homicides committed by strangers (+24) and acquaintances (+14) in 2020 than in 2019.

Detailed analysis of homicide in Canada in 2020 is scheduled to be published later in 2021.

Note to readers

While these data reveal patterns in police-reported violence during the beginning of the pandemic, they do not allow for inferences or conclusions about ongoing violence or an escalation of violence during COVID-19 pandemic restrictions. It is also important to note that family violence often does not come to the attention of police, even in a typical year.

Since 1998, Statistics Canada has released the annual publication "Family violence in Canada: A statistical profile" as part of the Government of Canada's Family Violence Initiative, which seeks to address intimate partner violence—and family-related violence against children and youth, and seniors. This year, however, the data tables from this publication are being released through a series of downloadable tables (35-10-0199-01, 35-10-0200-01, 35-10-0201-01 and 35-10-0202-01). The introduction of these tables allows the Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics to release annual police-reported family violence data in a more timely and user-friendly format.

Also released today by the Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics are a series of tables on victims of police-reported violent crime more broadly: tables 35-10-0049-01, 35-10-0050-01 and 35-10-0051-01.

Family violence refers to violence committed by spouses (legally married, separated, divorced and common-law, and current and former dating partners who lived together at the time of the incident), parents (biological, step, adoptive and foster), children (biological, step, adopted and foster), siblings (biological, step, half, adopted and foster) and extended family members (e.g., grandparents, uncles, aunts, cousins and in-laws). The definition of spousal violence was updated to include co-habitating dating partners (i.e., boyfriends and girlfriends). This change allows for more consistency in terms of how relationships are reported by police across jurisdictions in Canada.

The data presented in this article are from the Incident-based Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR 2) Survey, which collects detailed information on criminal incidents that have come to the attention of, and have been substantiated by, police services in Canada. Information includes characteristics of victims, accused persons and incidents. In 2019, data from police services covered 99% of the population of Canada. Victim age is calculated based on the end date of an incident, as reported by the police. Some victims experience violence over a period of time, sometimes years, all of which may be considered by the police to be part of one continuous incident.

The data presented in this article include victims with valid report dates. They Exclude victims of boyfriends and girlfriends aged 15 years and older who cannot be classified as victims of family violence (spouse or ex-spouse) because it is not known whether or not victims were living with the accused at the time of the incident. Given that small counts of victims identified as "gender diverse" may exist, the UCR aggregate data available to the public have been recoded to assign these counts to either "male" or "female," in order to ensure the protection of confidentiality and privacy. Victims identified as gender diverse have been assigned to either "male" or "female" based on the regional distribution of victims' gender.

Contact information

For more information, or to enquire about the concepts, methods or data quality of this release, contact us (toll-free 1-800-263-1136; 514-283-8300; STATCAN.infostats-infostats.STATCAN@canada.ca) or Media Relations (613-951-4636; STATCAN.mediahotline-ligneinfomedias.STATCAN@canada.ca).

- Date modified: