Criminal victimization in Canada, 2019

Archived Content

Information identified as archived is provided for reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It is not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards and has not been altered or updated since it was archived. Please "contact us" to request a format other than those available.

Released: 2021-08-25

Self-reported victimization data, such as those collected in the General Social Survey (GSS) on Victimization, are an important complement to official police data. Research shows that the majority of crimes are not reported to police; therefore, data collected through surveys on self-reported victimization help provide a more complete picture of the nature and prevalence of crime.

Results from the 2019 GSS are being released today in the Juristat article "Criminal victimization in Canada, 2019." Analysis focuses on the prevalence of victimization, the characteristics of victims and incidents, and the impacts and consequences of victimization. In addition, levels of reporting to police and factors associated with the decision to report victimization to police are examined.

Data collection for the 2019 GSS ended in March 2020, just as the COVID-19 pandemic was beginning to take hold and drastically change the daily lives of everyone living in Canada. Though the data do not reflect the circumstances of the pandemic, they do present important baseline information on the patterns, impacts and consequences of victimization just prior to the pandemic.

Almost 6 million Canadians reported that they or their household had been affected by crime in 2019

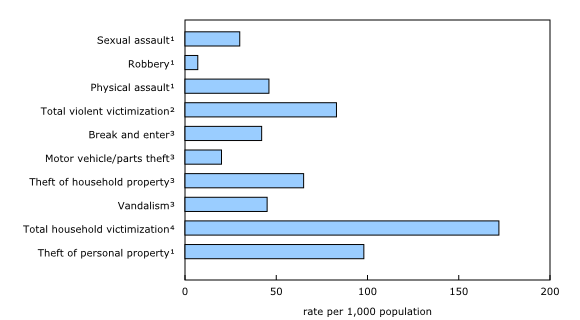

One in five Canadians—19%, or nearly 6 million people 15 years and older—reported that they or their household had experienced at least one of the crimes measured by the GSS in 2019. In total, there were more than 8 million incidents of criminal victimization, including sexual assault, robbery, physical assault, break and enter, theft of motor vehicles or parts, theft of household or personal property, and vandalism. Because of changes in collection methods for the GSS on Victimization, most notably the introduction of an online questionnaire to provide another way for Canadians to participate, comparisons with previous cycles are not recommended (see Note to readers).

The majority of these self-reported incidents—almost 7 in 10 (69%)—were non-violent in nature. Theft of personal property was the most common type of crime, accounting for more than one-third (37%) of all incidents.

More than 4 in 10 (42%) of those who were victimized personally or whose household was victimized experienced multiple incidents of crime.

In all, there were just over 2.6 million incidents of self-reported violent victimization (sexual assault, robbery and physical assault) in Canada in 2019. Expressed as a rate, there were 83 incidents of violent crime for every 1,000 Canadians 15 years and older. Physical assault was most common (46 incidents per 1,000 population), followed by sexual assault (30) and robbery (7). This is similar to police-reported data, which also show that physical assault is the most common type of violent crime and that sexual assault is more common than robbery.

Compared with the overall population, young people, women and sexual minorities are at higher risk of experiencing violence

Certain population groups were disproportionately impacted by violent victimization, according to the 2019 GSS. For example, young Canadians were more at risk of being a victim of a violent crime, with victimization rates highest among those aged 15 to 24 (176 incidents per 1,000 population) and those aged 25 to 34 (135 per 1,000). Rates declined with age, dropping to 20 incidents per 1,000 population among those aged 65 and older.

The rate of self-reported violent victimization was nearly twice as high among women (106 incidents per 1,000 women) than among men (59 incidents per 1,000 men) in 2019. This difference was driven by sexual assault, the rate of which was more than five times higher among women (50 per 1,000) than men (9 per 1,000).

In 2019, the violent victimization rate among bisexual Canadians was 655 incidents per 1,000 population, over nine times higher than that among heterosexual Canadians (70 per 1,000). There were no statistically significant differences in victimization rates between heterosexual Canadians and those who are lesbian or gay.

After other factors were controlled for, age, gender and sexual orientation all remained significantly associated with the likelihood of being victimized. Young people, women and people who reported a minority sexual identity were more at risk.

Rates of violent victimization higher among Indigenous people and people with a disability

Rates of violent victimization were almost three times higher among people with a disability (141 incidents per 1,000) than among those with no disability (53 per 1,000). In particular, women with a disability were more likely to be victimized, with 184 violent incidents for every 1,000 women with a disability, compared with 84 per 1,000 men with a disability.

The overall violent victimization rate among people designated as belonging to a visible minority group did not differ significantly from the rate for non–visible minorities. Relative to the overall visible minority population, rates were similar among Filipino people, while those who identified as Chinese recorded lower violent victimization rates. Because of the sample size, more detailed disaggregation of victimization rates among diverse populations is not possible.

In 2019, the rate of violent victimization among Indigenous people (First Nations, Métis or Inuit) (177 per 1,000) was more than double that among non-Indigenous people (80 per 1,000). In particular, Métis (225 per 1,000) and Inuit (265 per 1,000; use with caution) had higher rates; the violent victimization rate among First Nations people was not statistically different from that among non-Indigenous people.

A multitude of factors impact victimization rates, and differing victimization rates among certain populations may be related to variations in the prevalence of other risk factors among these groups. For example, childhood maltreatment is a significant risk factor for future victimization, and, based on the GSS on Victimization, Indigenous people experienced higher rates of physical and sexual abuse during childhood. The physical and sexual abuse of Indigenous children is a well-documented aspect of the historical and ongoing trauma and violence brought on by colonization, residential schools and the overrepresentation of Indigenous people in the child welfare system.

Childhood experiences of abuse, harsh parenting, neglect and witnessing violence are associated with higher rates of violent victimization

Research to date has found that adverse childhood experiences, such as physical abuse, sexual abuse, harsh parenting or neglect, and exposure to violence in the home, have all been linked to subsequent experiences of victimization in adulthood. Results from the 2019 GSS provide further support for these links.

Violent victimization rates were three to four times higher among people who were physically abused, sexually abused, experienced harsh parenting, and were exposed to violence in the home before the age of 15, compared with those who did not have these experiences.

Further information on child maltreatment is presented in the infographic "Childhood maltreatment and the link with victimization in adulthood: Findings from the 2019 General Social Survey," also available today.

Most criminal incidents are not reported to police

In 2019, most incidents of victimization were not reported to police, with about 3 in 10 (29%) coming to the attention of police. On the whole, incidents of household victimization were more likely than violent incidents to have been brought to the attention of police (35% versus 24%). One reason for this could be related to requirements set out by insurance companies for claims for stolen or damaged property, which was a reason cited by 45% of people who reported an incident of household crime to police.

Of all crimes measured by the GSS, sexual assault had the lowest rate of reporting to police, with 6% of incidents in 2019 having come to the attention of police. This figure is consistent with results from other self-reported surveys conducted both before and after the #MeToo movement.

Victims of violent crime may choose to report—or not report—an incident to police for a wide range of reasons. In 2019, about half of all victims of violent crime who did not report the incident to police did not report it because they felt that the crime was too minor (56%), the incident was not important enough (53%), they did not want the hassle of dealing with police (49%), the incident was private or personal (48%), or they felt no one was harmed (47%).

Note to readers

This Juristat article is based on results from the 2019 General Social Survey (GSS) on Canadians' Safety (Victimization). The main objective of the GSS on Victimization is to better understand issues related to the safety and security of Canadians, including perceptions of crime and the justice system, experiences of intimate partner violence, and how safe people feel in their communities.

The GSS on Victimization asked Canadians about their experiences with eight types of offences:

- Violent victimization: Sexual assault, robbery or physical assault.

- Sexual assault: Forced sexual activity; attempted forced sexual activity; unwanted sexual touching, grabbing, kissing or fondling; or sexual relations without being able to give consent.

- Robbery: Theft or attempted theft in which the offender had a weapon or there was violence or the threat of violence against the victim.

- Physical assault: An attack (victim hit, slapped, grabbed, knocked down or beaten), a face-to-face threat of physical harm, or an incident with a weapon present.

- Theft of personal property: Theft or attempted theft of personal property such as money, credit cards, clothing, jewellery, a purse or a wallet. Unlike robbery, the offender does not confront the victim.

- Household victimization: Break and enter, theft of motor vehicles or parts, theft of household property, or vandalism.

- Break and enter: Illegal entry or attempted entry into a residence or other building on the victim's property.

- Theft of motor vehicle or parts: Theft or attempted theft of a car, truck, van, motorcycle, moped or other vehicle, or part of a motor vehicle.

- Theft of household property: Theft or attempted theft of household property such as liquor, bicycles, electronic equipment, tools or appliances.

- Vandalism: Wilful damage of personal or household property.

To modernize collection activities and give Canadians another means through which they could participate in the survey, the GSS included the option to respond to the survey online in 2019. Any significant change in survey methodology can affect the comparability of the data over time. It is impossible to determine with certainty whether, and to what extent, differences in a variable are attributable to an actual change in the population and the behaviours being examined or to changes in the survey methodology between the collection cycles.

Consequently, comparisons of 2019 GSS results with results of previous GSS cycles conducted without the use of online questionnaires are not recommended, as any differences may be the result of a change in collection method rather than reflect actual changes in victimization patterns.

Methodological analysis shows that the data are of good quality and present an accurate picture of criminal victimization in Canada in 2019.

Products

The article "Criminal victimization in Canada, 2019" is now available as part of the publication Juristat (Catalogue number 85-002-X). The infographic "Childhood maltreatment and the link with victimization in adulthood: Findings from the 2019 General Social Survey" (Catalogue number 11-627-M) has also been released today.

Contact information

For more information, or to enquire about the concepts, methods or data quality of this release, contact us (toll-free 1-800-263-1136; 514-283-8300; STATCAN.infostats-infostats.STATCAN@canada.ca) or Media Relations (613-951-4636; STATCAN.mediahotline-ligneinfomedias.STATCAN@canada.ca).

- Date modified: