Selected police-reported crime and calls for service during the COVID-19 pandemic, March to October 2020

Archived Content

Information identified as archived is provided for reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It is not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards and has not been altered or updated since it was archived. Please "contact us" to request a format other than those available.

Released: 2021-01-27

The daily lives of Canadians have been altered in many ways because of the COVID-19 pandemic, with unprecedented impacts on the health care system, economy and society. Since the start of the pandemic, Statistics Canada has committed to measuring the impact of COVID-19 and providing timely information.

Previous studies have shown that during the pandemic, Canadians reported lower levels of life satisfaction, heightened concerns around health and mental health issues and, for some groups, feeling less safe, including concerns about violence in the home.

This analysis is the third in a series that examines police-reported crime and calls for service as part of a special monthly data collection from 19 police services across Canada, following releases in September 2020 and November 2020. Examining levels of police-reported crime and calls for service is important to understand the well-being and safety of individuals and communities during this difficult time.

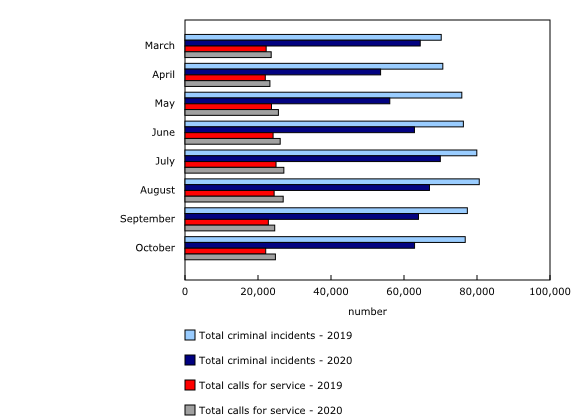

In the first eight months of the pandemic, 19 police services across Canada reported that selected criminal incidents were down by almost one-fifth (18%) compared with the same period a year earlier. In contrast, the number of calls for service, particularly wellness checks, mental health calls and calls to attend domestic disturbances, rose 8%.

In the first full month of the pandemic, the police services in this study reported that selected Criminal Code incidents decreased 17% from March to April, while calls for service were down 2% (correction). As lockdown restrictions and physical distancing measures eased under reopening plans during the summer months, the volume of crime and calls for service increased, peaking in July. From August to October, the volume of crime and calls for service began to decline again, yet remained higher than at the beginning of the pandemic.

Fewer selected police-reported criminal incidents in the first eight months of the pandemic compared with the same period last year

Data reported by 19 police services show that there were 18% fewer criminal incidents for select offences in the first eight months of the pandemic compared with the same period one year earlier. Collectively, these police services reported fewer incidents in 12 of the 13 crime types surveyed from March to October. The lone exception was uttering threats by a family member, with police reporting 2% more incidents in the first eight months of the pandemic compared with the previous year.

These 19 police services are some of the largest nationally and serve nearly three-quarters (71%) of the Canadian population. Nevertheless, these results are not representative of overall police-reported crime in Canada and caution should be exercised when interpreting the findings from this data collection activity. The criminal offences surveyed include several serious offences such as sexual assaults, assaults, robbery and break and enter (see the note to readers for more information on the police services and crimes included).

Following a low in April, crime rose as businesses, services and public spaces began to reopen, but fell again toward the end of the summer

Police services in this study reported a decline in almost all types of crimes from March to April, when non-essential businesses were closed and most Canadians stayed at home. However, as businesses, services and public spaces began to reopen, police reported that crime increased from April to May (+5%), from May to June (+12%), and from June to July (+11%). Even with these increases, police-reported crime was still lower than in the same period in 2019.

Following the peak summer months, police-reported crime began to decrease again toward the end of the summer, from July to August (-4%), from August to September (-4%), and from September to October (-2%). This general trend is similar to the one seen in the same months in 2019.

Fewer violent crimes and property crimes reported to police services during the pandemic compared with the same period a year earlier

Overall, the 19 police services reported fewer violent crimes during the pandemic, compared with the same period a year earlier. The number of reported sexual assaults decreased (-20%), including those committed by non-family members (-21%) and by family members (-10%). The number of reported assaults also declined (-9%), including those committed by non-family (-10%) and family members (-4%).

Despite the general decline in violent crime reported during the pandemic, police in this study reported slightly more incidents of violent crime in July 2020 compared with July 2019, due to increases in uttering threats (+11% in July 2020 compared with July 2019) and assault (+1% in July 2020 compared with July 2019).

With cities and communities shut down and Canadians staying at home, it is perhaps not surprising that police reported a drop in some of the more common types of property crime. Police services in this study reported that shoplifting was down by nearly half (-47%), residential breaking and entering was down by over one-quarter (-27%), and motor vehicle theft was down by under a fifth (-18%) from March to October compared with the same period a year earlier. One exception was non-residential breaking and entering, which increased in March (+26%) and April (+13%) compared with the same months a year earlier.

Since the onset of the pandemic, police have reported 9% fewer incidents of fraud (including identity theft and identity fraud) compared with the same period in 2019. A recent release, however, shows that just over 4 in 10 Canadians (42%) experienced at least one type of cyber security incident since the beginning of the pandemic, including phishing attacks, malware, fraud, and hacked accounts.

Of those who experienced a cyber security incident, less than one-third (29%) reported the incident to a relevant service provider, financial institution or credit card company, and 5% of individuals reported the incident to an authority such as the police. According to the Canadian Anti-Fraud Centre, from March to October 2020, there were 5,411 victims and over $6.6 million lost due to COVID-related fraud.

During the pandemic, violent crime and property crime peaked in July

Following a 15% decrease in reported violent criminal incidents in the study from March to April, violent crime increased significantly, peaking in July. Selected violent crimes rose 44% from April to July. Specifically, sexual assault (+84%), assault (+44%), and uttering threats (+41%) all rose sharply during this period. Following the peak in July, these types of crimes began to decrease, though violent crime as a whole remained 14% higher in October than in April. Although there was a sharp increase in violent crime during this period, it was still lower than in the same period in 2019 with the exception of July.

Victimization surveys have shown that rates of reporting to the police are lower for sexual assaults and spousal violence than for other types of crimes. For victims of violence, especially within the home, previous releases have shown that accessing services during the pandemic may be more difficult because of restricted contact with networks and sources of formal (schools, counsellors, victim services) and informal (family and friends) support.

Overall, property crime decreased 18% from March to April 2020, and fell again by 2% from April to May. Then, as with violent crime, property crime peaked in July, increasing 26% from its low in May. Shoplifting (+50%), fraud (+44%), impaired driving (+29%), and motor vehicle theft (+24%) all increased substantially during this period. Again, similar to violent crime, property crime remained 22% higher in October than its low in May. Notwithstanding the increases, property crime in 2020 was still lower than in 2019.

Calls for service to police up in the first eight months of the pandemic compared with the same period a year earlier

Police perform many duties, including responding to events that are directly related to public safety and well-being, even if they are not criminal in nature. These events are referred to as "calls for service."

Police services in this study responded to 8% more calls for service from March to October than they did over the same period in 2019. In particular, police services that were able to report data on calls for service responded to more calls related to general well-being checks (+13%), mental health-related calls such as responses to a person in emotional crisis or apprehensions under the Mental Health Act (+12%), and domestic disturbances (+8%).

The police services in this study reported more calls for service throughout the pandemic than they did for the same months the year before. From March to July, there were 7% more calls in 2020 compared with the same period a year earlier, while from August to October, there were 10% more calls.

Calls to police classified as domestic disturbances or domestic disputes can involve anything from a verbal quarrel to reports of violence at a residence.

Police involved in enforcing measures related to managing the pandemic

The police, along with by-law and public health officers, have been responsible for enforcing legislation related to containing the pandemic. These included enforcing municipal by-laws, provincial and territorial emergency health acts and the federal Quarantine Act. However, local police do not usually enforce by-laws and the enforcement of provincial or territorial emergency health acts is shared with public health officers. As such, data on these enforcements reflect police involvement and not necessarily the number of occurrences.

From mid-March to October, the 14 police services that provided data on the enforcement of pandemic-related provincial/territorial legislation reported involvement in 22,867 infractions of these acts. Spikes in provincial/territorial infractions linked to the pandemic were noted in three months. The first occurred in April at the beginning of the pandemic (+250%), the second in July (+18%) when more businesses began to reopen and larger social "bubbles" were permitted between households, and the third in September (+19%) when many schools and child care centres reopened.

To limit the spread of COVID-19, the Government of Canada implemented emergency orders in March 2020 requiring a mandatory 14-day quarantine or isolation for all travellers entering Canada. As of October 31, according to data from the Public Health Agency of Canada, the Agency had sent the RCMP 281,354 high and medium priority referrals for compliance verification, based on police capacity and resources. Of the 23,444 law enforcement follow-ups that were reported to the Public Health Agency of Canada by October 31, 99 resulted in fines for offences under the Quarantine Act, and 7 in court summons for charges laid under the Quarantine Act.

Note to readers

The Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics is conducting a special survey collection from a sample of police services across Canada to measure the impact of COVID-19 on selected types of crimes and calls for service. In addition, counts of police responses to infractions of municipal by-laws or provincial/territorial acts to contain the COVID-19 pandemic were requested. An initial report included findings from March to June 2020 compared with the same period a year earlier. A subsequent report included findings from March to August 2020, comparing monthly data throughout the pandemic. Data will continue to be collected monthly until December 2021 and to be reported regularly.

This is the third release of this special data collection by Statistics Canada. Previously published data may have been revised.

For this reference period of March to October, 19 police services provided data on a voluntary basis. These police services include the Calgary Police Service, Edmonton Police Service, Halton Regional Police Service, Kennebecasis Regional Police Force, London Police Service, Montréal Police Service, Ontario Provincial Police (OPP), Ottawa Police Service, Regina Police Service, Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP), Royal Newfoundland Constabulary, Saskatoon Police Service, Sûreté du Québec, Toronto Police Service, Vancouver Police Department, Victoria Police Department, Waterloo Regional Police Service, Winnipeg Police Service, and York Regional Police.

Police services that responded to this survey serve more than two-thirds (71%) of the Canadian population. Since the Edmonton Police Service, Montréal Police Service, RCMP, Sûreté du Québec and Winnipeg Police Service were unable to provide data on calls for service, the police services that did provide these data serve one-third (32%) of the Canadian population.

Selected crime types include the following: assaults; sexual assaults; assaults against a peace or public officer; uttering threats; robbery; dangerous operation causing death or bodily harm, impaired driving or impaired driving causing death or bodily harm; breaking and entering; motor vehicle theft; shoplifting; fraud / identity theft / identity fraud, and; failure to comply with order.

Calls for service are defined as calls received by police services that are citizen-generated or officer-initiated, and that required police resources to be tasked (such as a call to a 9-1-1 emergency line that resulted in the dispatch of an officer).

Correction note

On April 14, 2021, data for "Calls for service, overdose"; "Calls for service, child welfare check"; "Calls for service, child custody matter – domestic"; and "Total calls for service" for all reference periods were corrected due to an error in the application of selected response categories.

Contact information

For more information, or to enquire about the concepts, methods or data quality of this release, contact us (toll-free 1-800-263-1136; 514-283-8300; STATCAN.infostats-infostats.STATCAN@canada.ca) or Media Relations (613-951-4636; STATCAN.mediahotline-ligneinfomedias.STATCAN@canada.ca).

- Date modified: