Canadians' perceptions of personal safety since COVID-19

Archived Content

Information identified as archived is provided for reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It is not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards and has not been altered or updated since it was archived. Please "contact us" to request a format other than those available.

Released: 2020-06-09

Perception of safety is an internationally recognized indicator of a nation's well-being. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, most Canadians reported that they were satisfied or very satisfied with their personal safety from crime. Among citizens of countries belonging to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Canadians tend to feel among the safest. Furthermore, over the past two decades, the general trends in many self-reported measures of safety have shown that Canadians feel safer than they did in the past.

From May 12 to May 25, more than 43,000 Canadians participated in an online crowdsourcing survey to share their perceptions of crime and personal safety in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. Readers should note that unlike other surveys conducted by Statistics Canada, crowdsourcing data are not collected under a design using a probability-based sampling. Therefore, caution should be exercised when interpreting the findings, and no inferences about the overall Canadian population should be made based on these results.

As the lives of Canadians have changed since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, examining their sense of safety from crime and violence is an important part of understanding the well-being of individuals and communities more generally. It is also a way to better understand the potential need for services to support individuals, families, and communities during the recovery period, particularly among those most affected.

Half of participants feel that the level of crime in their neighbourhood has not changed

Since the start of the pandemic, police and victims' services in Canada and internationally have reported changes in the volume and types of crime that are coming to their attention. For example, some police services have noted drops in impaired driving or crimes against the person such as robbery, while offences such as commercial theft seem to be increasing. Concerns have been raised about certain types of crime that may become more prevalent or severe during a time of isolation, such as fraud or family violence.

Half (50%) of the crowdsourcing participants felt that the level of crime in their neighbourhood had remained about the same since the start of the pandemic, 15% felt that crime had decreased and 11% felt that it had increased. The remaining 24% of participants said they did not know if crime had changed or stayed the same.

Although not directly comparable, the 2014 General Social Survey (GSS) found that almost three-quarters (74%) of Canadians felt that crime in their neighbourhood had remained the same over the previous five years, 11% felt it had increased and 9% felt it had decreased.

Women (11%) and men (11%) were equally likely to feel that crime in their neighbourhood had increased, while women (13%) were less likely than men (17%) to say it had decreased.

There is some evidence suggesting women may be more concerned about safety during the pandemic. For instance, a representative web panel survey conducted by Statistics Canada in March found that 10% of women and 6% of men were concerned about violence in the home during the pandemic.

Indigenous (17%) and visible minority (14%) participants were more likely than non-Indigenous or non-visible minorities (both at 11%) to feel crime had increased in their neighbourhood.

Participants in British Columbia (24%) were the most likely to feel that crime in their neighbourhood had increased since the start of the pandemic, well above the level in Alberta (15%), which ranked second, and the national average (11%).

Most participants say that they feel safe when walking alone in their neighbourhood after dark

As was the case pre-pandemic, the majority of participants said that they felt safe from crime when walking alone in their neighbourhood after dark. While just over 2 out of 10 (22%) participants said that they did not walk alone after dark in their neighbourhood since the start of the pandemic, 83% of those who said that they did stated that they felt either very safe (40%) or somewhat safe (43%).

According to the 2014 GSS, 92% of Canadians reported feeling either very safe (52%) or somewhat safe (40%) when walking alone after dark in their neighbourhood. The trend over the past 20 years had been one of an improving sense of safety.

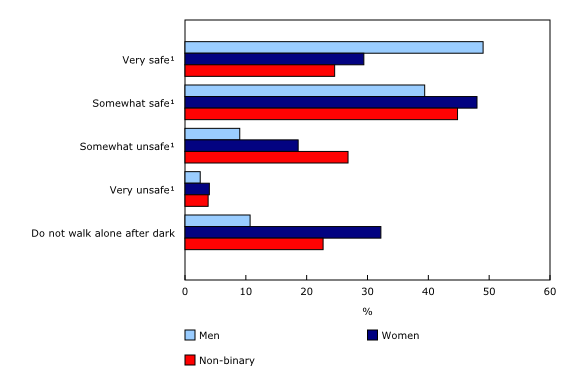

Female participants―particularly young women―less likely than men to report feeling safe when walking alone in their neighbourhood after dark

Women are generally less likely than men to report feeling safe when walking alone after dark in their neighbourhood. The 2014 GSS found that 64% of men who walk alone in their neighbourhood after dark felt very safe, compared with 38% of women. Feeling unsafe can reduce social cohesion and can have negative impacts on people's physical and mental health and overall well-being.

Almost half of men (49%) who participated in the crowdsourcing survey said that they felt very safe walking alone after dark in their neighbourhood since the start of the pandemic, compared with less than one-third of women (29%). Female participants were almost three times more likely to report not walking alone after dark in their neighbourhood (32%) than men (11%).

Young women were the least likely to report that they felt safe when walking alone after dark in their neighbourhood since the start of the pandemic. About one in eight (12%) women aged 15 to 24 and one in four (25%) women aged 25 to 34 reported that they felt very safe when walking alone after dark in their neighbourhood. Young female participants were also more likely to feel that crime had increased in their neighbourhood since the start of COVID-19.

Visible minorities (27%) and Indigenous (26%) participants were more likely to say that they feel unsafe walking alone in their neighbourhood after dark than non-visible minorities (15%) and non-Indigenous (16%) participants.

Among participants, 1 in 14 feel harassment or attacks based on race, ethnicity, or skin colour are increasing

Signs of social disorder such as harassment or attacks based on race, ethnicity, or skin colour, can also reduce sense of safety. This is particularly the case when they occur in one's neighbourhood, as perceptions of safety are largely influenced by characteristics of an individual's immediate environment.

Over one-third (37%) of those who participated in the crowdsourcing survey felt that harassment or attacks based on race, ethnicity, or skin colour were occurring in their neighbourhood at about the same frequency as before the pandemic, while just over half (52%) said they did not know. However, the proportion of those reporting that race-based incidents had increased in their neighbourhood (7%) was greater than the proportion of those indicating it had decreased (4%).

Over half (54%) of participants stated that harassment or attacks based on race, ethnicity, or skin colour were rare in their neighbourhood, 10% said these incidents occurred sometimes, and 2% stated that they happened often. Just over one-third of participants (35%) reported not knowing how often these incidents took place.

In the 2014 GSS, the vast majority of respondents (92%) said attacks or harassment due to race, skin colour, ethnicity, or religion were not a problem at all in their neighbourhood, 6% felt they were a big, small, or moderate problem, and 2% said they did not know.

Visible minority participants more likely to perceive an increase in race-based harassment or attacks

Men (8%) were somewhat more likely than women (6%) to say that they feel that harassment or attacks on the basis of race, ethnicity, or skin colour had increased since the start of the pandemic. Non-binary participants were considerably more likely than either men or women to perceive an increase (22%).

Younger participants aged 15 to 24 (11%) or 25 to 34 (9%) were most likely to report that harassment or attacks on the basis of race, ethnicity, or skin colour have increased in their neighbourhood since the start of the pandemic. The proportion fell consistently with age, to 4% among those aged 65 and older.

Some police services and media outlets across Canada have reported an increase in hate crimes since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, specifically those targeting Asian populations. Almost one in five (18%) visible minority participants felt that race-based incidents had increased since the start of the pandemic, compared with 6% of non-visible minorities. Nearly one-third (30%) of Chinese participants stated that there had been an increase, the highest level of any group.

Participants in British Columbia were most likely to perceive an increase in these incidents (15%), more than double the proportion in the next-highest provinces, Alberta (7%) and Ontario (7%). Those living in urban areas (8%) were more likely than rural participants (5%) to state that these incidents were more frequent since the start of the pandemic.

Women more likely than men to say that they contact victims' services because of crime

Depending on their mandate, victims' services provide support related to, for example, protection, information, shelter, or physical and mental health. The way in which these services are offered may have shifted due to the pandemic, but victims' services continue to be an important point of access for many who have been impacted by crime or violence—as victims, witnesses, or family or community members.

Overall, 10% of participants said that they have contacted a victims' service for a reason related to crime since the start of the pandemic. Women (11%) were more likely than men (8%) to report having done so. More specifically, 14% of women aged 15 to 24 said they had contacted or used a victims' service since the start of the pandemic, more than any other age group of women or men.

Those who indicated they had contacted the police or a victims' service were also more likely to feel that crime had increased in their neighbourhood and to report feeling unsafe walking alone after dark in their neighbourhood.

Most say their neighbours would call the police if they witnessed crime in their neighbourhood

Living in a neighbourhood where it is perceived that neighbours would call the police if they heard or witnessed what seemed like violence in someone's home can be a sign of social cohesion—which research has generally associated with a greater sense of personal safety.

Most participants felt it was very (37%) or somewhat (41%) likely that their neighbours would call the police if they heard or witnessed what seemed like violence in a home. In the 2014 GSS, about 9 in 10 Canadians felt it was very (65%) or somewhat (26%) likely that their neighbours would call the police if they witnessed crime in their neighbourhood.

Younger participants were less likely to feel their neighbours would call the police if they witnessed violence in someone's home. Seven in ten (70%) participants aged 15 to 24 felt it was very or somewhat likely that their neighbours would do so, a proportion which steadily increased with age, reaching 85% among those aged 65 and older.

Younger participants appear to perceive the most change in crime and safety since the start of the pandemic

Many participants did not perceive significant changes in crime or safety as a result of the pandemic. That said, results suggest that the pandemic may be having more of an impact on the perceptions of safety among younger people.

Younger participants, particularly young women, were more likely to feel that there has been an increase in crime and race-based harassment or attacks in their neighbourhood since the start of the pandemic. Young women were also more likely to report having contacted or used a victims' service, and less likely to report feeling safe when walking alone after dark in their neighbourhood since the start of the pandemic.

Note to readers

Over the next few weeks, new crowdsourcing initiatives will be launched to get timely information about other important issues, such as the extent to which COVID-19 is affecting the lives and well-being of different groups of Canadians. Canadians are invited to keep coming to the website in order to participate.

Methodological adjustments have been made to account for age, sex and provincial differences.

When it comes to measuring perceptions of crime and safety, many of those who are most susceptible to shifts in perceived safety or risk of crime may be unable to participate.

Contact information

For more information, or to enquire about the concepts, methods or data quality of this release, contact us (toll-free 1-800-263-1136; 514-283-8300; STATCAN.infostats-infostats.STATCAN@canada.ca) or Media Relations (613-951-4636; STATCAN.mediahotline-ligneinfomedias.STATCAN@canada.ca).

- Date modified: