Study: Occupations with older workers

Archived Content

Information identified as archived is provided for reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It is not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards and has not been altered or updated since it was archived. Please "contact us" to request a format other than those available.

Released: 2019-07-25

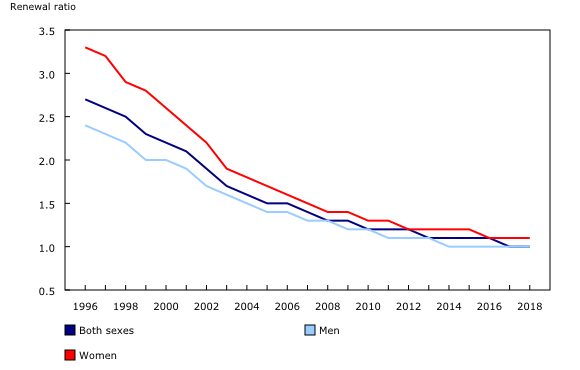

As Canada's population is aging, so too is its workforce. In 1996, there were 2.7 workers aged 25 to 34 for every worker aged 55 and older. By 2018, the ratio declined to 1.0.

The aging of the workforce is mostly the result of the large cohort of baby boomers who are entering their retirement years. This has resulted in a larger share of people aged 55 and older in the labour force than has previously been the case.

Knowledge of the pattern and pace of aging within occupations is essential to understand a well-functioning labour force. While a higher proportion of older workers may reflect occupations that require higher levels of skills and experience, it can also foreshadow the decline of an occupation or challenges in replacing older workers.

A new study published today in Insights on Canadian Society finds that an aging workforce is affecting all occupations, but also that there is considerable variation in the extent and pace of aging across occupations.

The study, titled "Results from the 2016 Census: Occupations with older workers", uses the Census of Population (1996 and 2016) and the Labour Force Survey (1996 to 2018) to examine changes in the age composition of occupations.

The aging of the workforce is affecting all occupations

The aging of the workforce can be examined by calculating the ratio of younger workers to older workers, which is defined in this study as the number of workers aged 25 to 34 for every worker aged 55 and older.

In 1996, there were 2.7 workers aged 25 to 34 for every worker aged 55 and older. Over the following two decades, this ratio declined rapidly, reaching 1.0 by 2018.

From 1996 to 2018, the proportion of workers aged 55 and older almost doubled, from 10% to 21% of the workforce. The proportion of older workers increased in all major occupations over this period. The aging of the workforce, however, was not uniform across occupations for a variety of reasons.

Entry of women mitigates the impact of aging in several occupations

In some occupations, the impact of an aging workforce was moderated by the entry of women in large numbers in recent years.

For example, among general practitioners and family physicians in 2016, the proportion of men aged 55 and older (38%) was double that of women (19%), resulting from faster growth among women general practitioners in the 20-year period leading up to 2016.

A similar pattern was seen in other professional occupations as well, such as lawyers and Quebec notaries, and financial auditors and accountants. In these occupations, the recent entry of women also contributed to slowing the impact of an aging workforce.

Health care professions are aging rapidly

Health care and social assistance was the largest industry in Canada in 2016, accounting for 2.3 million or 13%, of all workers. This industry also had one of the most rapid growth rates in the number of workers from 1996 to 2016 (+68%).

Despite the rising demand for health care services, workers who are providing health care to an increasingly older population are themselves aging. For instance, among registered nurses and registered psychiatric nurses—the largest occupation related to health care—about 1 in 5 was aged 55 and older in 2016, compared with less than 1 in 10 in 1996.

In 1996, there were 4.5 female nurses aged 25 to 34 for each female nurse aged 55 and older. By 2016, that ratio had declined to 1.6.

Similarly, specialist physicians had one of the largest shares of older workers at 31% in 2016, compared with 23% in 1996.

In some occupations, aging is largely the result of structural declines

In some other occupations, workforce aging occurred simply because workers in these occupations are less in demand, often as a result of automation and globalization. These occupations are therefore less attractive to younger workers.

Among managers in agriculture, for instance, more than half (52%) were aged 55 and older in 2016. This reflects the long-term decline in agricultural employment over the past century, which is related to socioeconomic changes that include the concentration of farming operations and the growing use of new technology, such as automation.

Several occupations in manufacturing industries also saw large declines, since some of these industries contracted sharply over the past two decades.

For instance, the number of industrial sewing machine operators declined by 73% over the past two decades – the largest decline of all major occupations. At the same time, this occupation had the highest percentage point increase in workers aged 55 and older across all occupations, from 12% in 1996 to 42% (+30 percentage points) in 2016.

Emerging occupations are less affected by an aging workforce

In contrast to many occupations in manufacturing or agriculture, emerging occupations are characterized by rapid growth, and therefore had a slower pace of aging as well as renewal ratios well above replacement.

From 1996 to 2016, the total number of workers in professional occupations in advertising, marketing and public relations grew by 256%, while the share of workers aged 55 and older rose less quickly than in most other occupations, from 8% to 13%. Computer and information systems managers also saw rapid growth (+209%) as well as a below-average proportion of older workers in 2016 (16%).

Furthermore, some occupations related to computer and information systems that were prevalent in 2016 had no direct equivalent in 1996. This reflects the growing importance of the knowledge economy.

Information systems analysts and consultants, computer programmers and interactive media developers, and computer network technicians were the three most common such occupations, representing nearly 325,000 workers in 2016. These also tended to be occupations with younger workers, and relatively small shares of workers aged 55 and older (ranging from 9% to 16%).

Note to readers

In this study, Census of Population data from 1996 and 2016 are used to examine occupations with at least 10,000 workers aged 15 and older for both census years. According to the 2016 Census, occupations with at least 10,000 workers aged 15 years and older in 2016 represented 14.6 million workers across more than 270 occupations, out of a total of 17.2 million workers.

The Labour Force Survey (LFS) is a monthly survey of about 54,000 households. The LFS sample is representative of the civilian non-institutionalized population aged 15 and older. It gathers information on the labour force status of those surveyed, as well as detailed information on the nature of the main occupation of those employed. In this study, LFS data are used to compute the renewal ratio and draw comparisons over time.

Products

The study "Results from the 2016 Census: Occupations with older workers" is now available in Insights on Canadian Society (Catalogue number 75-006-X).

Contact information

For more information, contact us (toll-free 1-800-263-1136; 514-283-8300; STATCAN.infostats-infostats.STATCAN@canada.ca).

To enquire about the concepts, methods or data quality of this release, contact Bertrand Ouellet-Léveillé (613-864-6641; bertrand.ouellet-leveille@canada.ca).

For more information on Insights on Canadian Society, contact Sébastien LaRochelle-Côté (613-951-0803; sebastien.larochelle-cote@canada.ca).

- Date modified: