Labour in Canada: Key results from the 2016 Census

Archived Content

Information identified as archived is provided for reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It is not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards and has not been altered or updated since it was archived. Please "contact us" to request a format other than those available.

Released: 2017-11-29

Today, Statistics Canada is releasing data on the Canadian labour market from the 2016 Census.

Since 2006, the working patterns of Canadians have evolved alongside social and economic changes, which have affected the labour market. Changes such as population aging, immigration, the 2008-2009 financial crisis, automation technologies, and the continued trend of increased participation among women create new challenges and opportunities for Canadians in the labour force.

Highlights

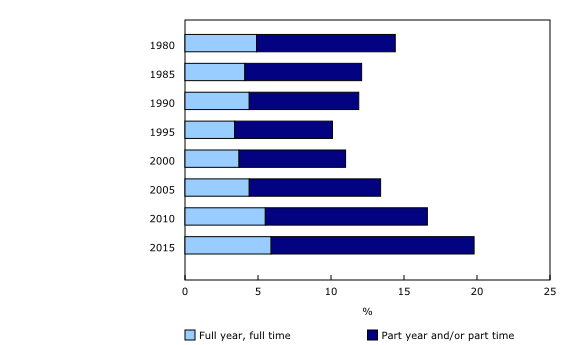

More people are working past the age of 65. Nearly one in five Canadians aged 65 and older reported working at some point during 2015. This was almost double the proportion in 1995. In 2015, 5.9% of seniors worked all year, full time, the highest level since comparable measures were introduced in the 1981 Census.

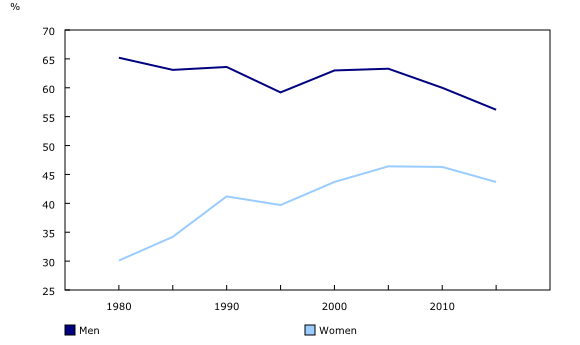

Fewer core-aged men (those aged 25 to 54) are working full-time all year. In 2015, 56.2% of men aged 25 to 54 worked full-time all year, down from 63.3% a decade earlier, and the lowest proportion since 1980—the first reference year for which comparable statistics were collected. The proportion of core-aged women who worked full-time all year also declined, but to a lesser extent.

From 2006 to 2016, the employment rate fell from 62.6% to 60.2%.

The Prairie provinces, as well as Yukon and the Northwest Territories, had the highest employment rates in 2016, while Newfoundland and Labrador and Nunavut had the lowest. These differences are related in part to variations in age structure and migration patterns across the country.

Immigrants accounted for nearly one-quarter of Canada's labour force in 2016. Core-aged recent immigrants (those who landed within the previous five years) had an employment rate of 68.5%, up from 67.0% in 2006. Over the same period, the employment rate for both the core-aged Canadian born and those who immigrated more than five years earlier edged down.

From 2006 to 2016, employment rates increased for core-aged Métis women and held steady for First Nations women aged 25 to 54 living off-reserve. It declined for other core-aged Aboriginal groups.

Youth aged 15 to 24 were less likely to work in 2016 compared with 2006, and the decline in the employment rate was greater for young men than for young women. As well, work activity decreased for both those who reported attending school as well as those who did not.

Continuing a trend which began more than 50 years ago, employment growth was strongest in service-producing industries from 2006 to 2016, most notably in health care and social assistance as well as in retail trade. At the same time, there were fewer people working in goods-producing sectors.

There were notable gender differences across occupational groups, with women outnumbering men four to one among fast-growing health occupations, while men outnumbered women three to one in high-tech occupations. Gender disparities in managerial occupations persisted, with men comprising 62.2% of that occupation group. At the same time, there were shifts in the types of managerial occupations by gender.

A larger proportion of people aged 65 and older are working

Nearly one in five (19.8%) Canadians aged 65 and older reported working at some point in 2015. This was almost double the proportion in 1995, with most of the increase coming from part-year and/or part-time work. In 2015, 25.7% of men and 14.6% of women aged 65 and older reported working.

Employment rates among seniors can be attributed to several economic and social changes. Some may work past traditional retirement age by choice, or out of necessity. Factors such as higher levels of educational attainment of seniors are associated with higher levels of employment. Higher employment rates could also be related to an increase in the debt levels of older Canadians, increased wages and more favourable employment opportunities, better health, and an increasingly service-sector oriented labour market with less manual labour.

In 2015, 5.9% of seniors worked full time/full year, the highest level since comparable measures were introduced in the 1981 Census. Canadians aged 65 and older with a bachelor's degree or higher and those without private retirement income were more likely to work than other seniors.

People aged 65 and older in the territories as well as in Saskatchewan, Alberta and Prince Edward Island were the most likely to work in 2015. Meanwhile, those in Newfoundland and Labrador, Quebec and New Brunswick were the least likely to do so. Across the country, seniors living in rural areas were more likely to work than seniors living elsewhere. These results are influenced by employment among older Canadians in the agriculture sector.

Increased employment among seniors is important to offset the impact of population aging. From 2006 to 2016, the number of Canadians aged 65 and older increased by 36.6% while the number of Canadians aged 15 to 64 grew by 7.7%. In 2016, 19.1% of the population aged 15 and older was over 65 years of age. According to the low-growth scenario of Statistics Canada's most recent population projections, this proportion could reach 29.3% by 2036.

Among older Canadians who are working, their median employment income has grown significantly since 2005. Canadians aged 65 to 74 who worked full year, full time saw their median employment income grow by 30.6%, from $33,842 to $44,193 (both in 2015 constant dollars). Those aged 65 to 74 who worked either part year and/or part time saw median employment income growth of 20.8% (from $11,816 to $14,274).

For more information on employment among older Canadians, please see the article entitled Working seniors in Canada from the Census in Brief series.

Fewer men and women aged 25 to 54 were working full-time all year in 2015

The period from 2005 to 2015 saw an overall shift from full-time, full-year employment to part-time or part-year work. The shift away from full-time, year-round employment to part-time and part-year work is related to a combination of social and economic changes, such as the 2008-2009 financial crisis and automation technologies, which have affected the labour market. It also coincides with a shift from traditional to more flexible work schedules—and personal choice.

In 2015, 56.2% of men aged 25 to 54 worked full time all year, down from 63.3% a decade earlier, and the lowest proportion since 1980—the first reference year for which comparable statistics were collected.

The proportion of core-aged women who worked full time all year also declined, but less markedly. In 2015, 43.7% of women in this age group worked full year and full time, down from 46.4% in 2005.

During this same period, the proportion of core-aged men who did not work at all during the year increased from 8.3% to 10.0%, but remained relatively stable among women, at 17.6%.

Regional trends in employment rates reflect population and migration changes

In May 2016, 17.2 million people were employed in Canada. The employment rate—that is, the number of workers as a proportion of the total population aged 15 and older—was 60.2%, down from 62.6% in May 2006.

Employment rates varied significantly across Canada in 2016, reflecting a number of factors, including growth in certain industries such as oil, the age structure of provinces and territories, and migration patterns over the past decade.

Employment rates in 2016 were above the national average on the Prairies, led by Alberta at 65.4%, and followed by Saskatchewan (63.5%) and Manitoba (61.7%). This is consistent with above-average migration growth in these provinces, with people moving there because of work prospects. However, in each of these provinces, the employment rate was lower than in 2006, partly due to the economic impact of lower oil prices.

The lowest employment rates were in Newfoundland and Labrador (49.5%) and Nunavut (53.6%). These two regions also had the lowest rates in 2006.

In May 2016, Yukon (68.5%) reported the highest employment rate in Canada, followed by the Northwest Territories (66.2%). Both territories have young and growing populations, and both had some of the highest proportions of workers in 2016 who were living in another province or territory five years earlier, indicating that many people are drawn to these areas specifically for work.

Among census metropolitan areas (CMAs), those on the Prairies generally had above-average employment rates. Regina had the highest rate at 66.8%, followed by Saskatoon (66.5%) and Calgary (66.5%). The lowest employment rates were in Saguenay (54.5%), Trois-Rivières (55.1%), Windsor (55.3%) and Peterborough (55.3%).

Some of the difference between the three highest and three lowest CMAs was accounted for by their age distributions; those with the lowest employment rates had an older population base. The difference in rates was also related to the general economic strength in the resource-based provinces, such as Alberta and Saskatchewan, and some weakness within the historically manufacturing-based provinces of Ontario and Quebec.

For the three largest CMAs, employment rates were slightly above the national average. Vancouver led the way at 61.8%, followed closely by Toronto (61.2%) and Montréal (61.0%).

Immigrants accounted for almost one-quarter of the labour force

From 2006 to 2016, about two-thirds of Canada's population growth was the result of migratory increase (the difference between the number of immigrants and emigrants). Similarly, the labour force was growing in large part due to increased immigration, with immigrants accounting for 23.8% of the labour force in 2016, up from 21.2% in 2006.

In 2016, half of the workforce in the CMA of Toronto were immigrants. The CMA of Vancouver had the second-highest proportion of immigrants in its labour force at 43.2%, followed by the CMA of Calgary at 32.5%.

The contribution of immigrants to the Canadian labour market is an important component of strategies to offset the impact of population aging, which might otherwise lead to a shrinking pool of workers and labour shortages. Many immigrants are admitted into Canada based on their skills and education.

In May 2016, among recent immigrants aged 25 to 54, 68.5% were employed, compared with an employment rate of 79.5% for core-aged immigrants who landed more than five years before the census, and 82.0% for the Canadian-born population. Among recent immigrants in this age group, 79.6% of men were employed, compared with 58.6% of women.

Although the employment rate for core-aged recent immigrants was lower than that of other immigrants and the Canadian-born, it increased from 67.1% in 2006 to 68.5% in 2016. For core-aged recent immigrant women, the employment rate increased from 56.8% in 2006 to 58.6% in 2016, and for core-aged recent immigrant men, the rate increased from 78.7% to 79.6%. In contrast, employment rates for core-aged Canadian-born men, as well as for non-recent immigrant men and women, declined over this 10-year period.

Employment rates increased for Métis women and held steady for off-reserve First Nations women

As reported in the 'Aboriginal census release,' Aboriginal peoples represent 4.9% of the population and are one of Canada's fastest growing populations. However, Aboriginal people of core working age have notably lower employment rates compared with other groups.

In 2016, the employment rates for Aboriginal people aged 25 to 54 ranged from 47.0% for First Nations people living on reserve, to 74.6% among Métis. The employment rate for Aboriginal men was higher compared with Aboriginal women for all Aboriginal groups, except for Inuit women living inside Inuit Nunangat and for First Nations women living on reserve.

Most employment rates for core-aged Aboriginal groups declined from 2006 to 2016. However, there were two exceptions: the employment rate for First Nations women living off-reserve was unchanged, at 61.5%, and the employment rate for Métis women increased 2.0 percentage points to 72.4%.

Youth employment declined

In 2016, for the second consecutive census, there were fewer people aged 15 to 24 (4.3 million) than people aged 55 to 64 (4.9 million).

This situation could lead to a number of challenges, particularly the renewal of the labour force, knowledge transfer, job retention, continuing education and labour productivity.

The employment rate for youths aged 15 to 24 fell from 57.2% in 2006 to 51.9% in 2016. Young men were less likely to work than their female counterparts in 2016, just as they were in 2006. The employment rate among young men fell 6.1 percentage points to 50.7% over this period, while it fell 4.4 percentage points to 53.1% among young women.

The overall employment rate for youth was highest in Quebec (54.8%) and Alberta (54.4%). Among the provinces and territories, young men in Yukon were most likely to work (54.6%) while young women in Quebec were most likely to work (56.8%). The youth employment rate was lowest in Nunavut (32.0%) and Newfoundland and Labrador (42.8%).

The percentage of youths aged 15 to 24 working full year, full time also declined, falling from 13.8% in 2005 to 11.5% in 2015. Part of this decline was associated with social and economic factors such as increased school attendance and delayed entry into the labour market compared with previous generations. However, work activity decreased for both those who reported attending school as well as those who did not.

Among youth aged 15 to 24 attending school, the proportion who worked part year and/or part time also fell between 2005 and 2015, down 4.4 percentage points to 56.3%. The proportion of this group which did not work at all increased by 5.8 percentage points over the same period. The part-year and/or part-time employment rate among those who did not attend school was similar between 2005 and 2015.

Job growth strongest in service industries

Continuing a trend which has existed for more than 50 years, employment growth was strongest in service-producing industries. From 2006 to 2016, employment in the services sector grew 12.0% to 13.7 million. At the same time, employment in the goods-producing sector fell 5.3% to 3.5 million. In May 2016, almost four out of five workers (79.7%) worked in the services sector, up from about 76.1% of the workforce in 1996.

The health care and social assistance industry was the largest employer among all industries in 2016, followed by retail trade. Just over two million people, representing 12.1% of all workers, were in health care and social assistance. Retail trade accounted for just under two million workers, or 11.5% of all workers.

The manufacturing sector had the third highest share of employment (8.8%) in 2016, totalling just over 1.5 million workers. In 2006, manufacturing had the highest share of workers, representing 11.9% of total employment. There were 385,200 (-20.3%) fewer people working in manufacturing in 2016 compared with 2006.

Employment in services-producing industries increased in every province and territory from 2006 to 2016. Over the same period, goods-producing employment growth was limited to Newfoundland and Labrador, Saskatchewan, Alberta, Yukon and Nunavut. Most of these regions had goods-producing increases concentrated in construction and, to a lesser extent, in mining, quarrying, and oil and gas extraction. In Alberta, employment in mining, quarrying, and oil and gas extraction declined 5.0% from 2006 to 2016, partly the result of subdued growth related to volatility in global oil prices over this period.

Retail salesperson remains the most common occupation

The most common occupations in Canada in 2016 were in the broad occupational category of sales and services, continuing a trend in recent decades. These jobs included food service counter attendants, service station attendants and grocery clerks. Many workers in sales and service work part time. The median age among these jobs (36.7 years) was among the lowest of all broad occupation groups. Just over one in four women had a job in sales and service, compared with about one in five men.

Specifically, retail salesperson was the most common occupation in 2016, with 626,775 working in this position, representing 3.6% of all workers and with a median age of 33.1 years. This was also the top occupation in 2006. The second most common occupation in 2016 was retail and wholesale trade manager, representing 387,320 or 2.2% of all workers and with a median age of 45.7 years.

Among women, retail salespersons accounted for 355,620 people, or 4.3% of total female employment. This was followed by registered nurses and registered psychiatric nurses (3.2%), cashiers (3.1%), elementary school and kindergarten teachers (2.9%) and administrative assistants (2.8%).

Among men, the most common occupation was transport truck drivers, with 278,505 workers representing 3.1% of total male employment. This was followed closely by retail salespersons (3.0%), retail and wholesale managers (2.5%), janitors, caretakers and building superintendents (1.8%) and construction trades helpers and labourers (1.7%).

More men than women in managerial occupations

More managerial positions were occupied by men than by women in May 2016 (62.2% versus 37.8%). Although the share of women in these occupations edged up from 36.5% in 2006 to 37.8% in 2016, significant gender differences persisted in managerial occupations in agriculture, construction and manufacturing. At the same time, women outnumbered men in managerial occupations in finance, in advertising, marketing and public relations, as well as in health and education.

Women outnumbered men four to one in health occupations

Just under one million women were employed in the broad occupational category of health. As in previous censuses, women outnumbered men four to one in health occupations, due mainly to the high proportion of female registered nurses, nursing assistants and nurse aides.

Women are making significant strides in the medical field. In 2016, general practitioners and specialist physicians were more likely to be women than 20 years earlier. Among core-aged people (those aged 25 to 54), 50.1% of general practitioners and specialist physicians were women in 2016, up from 34.0% in 1996.

High-tech occupations growing

Emerging trends in technology are reflected in the Canadian labour market. Employment in the high-skilled computer and information systems professionals group grew by nearly 56,000 workers (+18.8%) from 2006 to 353,550 workers in 2016, representing 2.1% of total employment.

Men comprised just over three-quarters of computer and information systems professionals (76.9%) in 2016, slightly above their share of 74.2% in 2006. The median age for this occupation group was 40.9 years, and ranged from 34.7 years for web designers and developers to 43.6 years for information systems analysts and consultants, as well as database analysts and data administrators.

Employment for computer and information systems professionals varied by region, with some "tech hubs" fostering a higher proportion of these workers. Employment in this group represented 4.9% of all employment in the CMA of Ottawa–Gatineau, more than in any other region. Among the other CMAs, Toronto had the second-highest share of computer and information systems professionals working in this occupation group as a proportion of its total employment (3.7%). This was followed by Kitchener–Cambridge–Waterloo and Québec.

More information about people with degrees in computer and information science and their labour market outcomes can be found in today's education Census in Brief release.

In celebration of the country's 150th birthday, Statistics Canada is presenting snapshots from our rich statistical history.

The first census after Confederation was conducted in 1871. At that time, occupations were grouped into six classes. The largest percentage of workers were the agricultural class (48%) and the industrial class (21%). Among the top 10 occupations, farmers represented the largest share of workers (47%), followed by labourers (12%) and female servants (4%). By 2016, the categorization of occupations had evolved to 10 broad groupings from the original 6, eliminating occupations that had disappeared and including new occupations that had emerged.

With increased educational attainment, globalization and technological advancement over the last 150 years, the professional class, which was once the smallest occupation class in 1871 at 4% of employment, had grown to 19% by 2016. Meanwhile, workers in natural resources and agriculture occupations in 2016 represented 2% of all workers, compared with about half of all workers in 1871.

Similarly, in 1871, carpenters and joiners had the fourth largest share of workers, but accounted for only 0.9% of employment in 2016. Shoemakers and blacksmiths, which made the top 10 list in 1871, have virtually disappeared in the 21st century.

English and French: Pathways to integration into the labour market

Information on the languages that Canadians used in the workplace in 2016 is also being released today.

Data on the language of work confirm the importance of English and French, Canada's official languages, as languages of communication in the public sphere. For example, 99.2% of Canadians (19,804,505 people) who were employed between January 1, 2015, and May 7, 2016 reported that they used English or French at least on a regular basis in the workplace.

The portrait of the use of languages at work is relatively stable throughout Canada. The proportion of workers who reported using English rose from 85.0% in 2006 to 85.8% in 2016, an increase of 1,538,205 people. In Canada outside Quebec, 98.6% of workers reported using English at least on a regular basis, and 9 out of 10 workers reported using only English.

Despite an increase across Canada in the number of workers who use French, up 277,015 to 4,986,905 in 2016, their proportion of all workers in Canada fell during this period. Canada-wide, the use of French edged down from 25.7% in 2006 to 25.0% in 2016. In Quebec, the predominant use of French in the workplace fell from 82.0% in 2006 to 79.7% in 2016. This decline was mainly in favour of the equal use of French and English, which rose from 4.6% in 2006 to 7.2% in 2016.

An increase in the overall use of English at work was observed in Quebec, from 40.4% in 2006 to 42.5% in 2016. This increase was driven by several factors, including increases in certain jobs where individuals were more likely to work in English (such as computer programmer) and the evolution in certain industry sectors (such as professional, scientific and technical services). This increase in the use of English at work was also observed for certain areas and cities in the province of Quebec. At a local level, these increases were not only driven by the factors mentioned above, but also by local industry.

Fewer than 5% of Canadian workers (970,910 people) reported using a language other than English or French in the workplace in 2016, either as the language they used most often at work (2.3%), or as a secondary language used on a regular basis (2.6%).

In Nunavut, where Inuktitut is an official language along with English and French, almost 6 in 10 workers (59.1%) used Inuktitut at work, down from 61.0% in 2006.

A more in-depth analysis is presented in the article Languages used in the workplace in Canada from the Census in Brief series.

Note to readers

Definitions and concepts

The Work Activity measure contains the following categories:

- Full year and full time (worked for 49 to 52 weeks, mostly full time)

- Full year and part time (worked for 49 to 52 weeks, mostly part time)

- Part year and full time (worked less than 49 weeks, mostly full time)

- Part year and part time (worked less than 49 weeks, mostly part time)

- Did not work at all in the reference year

Full time means usually working 30 hours or more. For the purposes of the labour analytical products, part year and/or part time refers to the sum of categories 2 to 4.

The Census Work Activity variable is a complement to the monthly estimates of labour force participation produced by the Labour Force Survey, in that it captures the 'intensity' of employment over a 12-month period. Those who worked full time throughout 2015, for example, can be distinguished from those who worked part time or who moved in and out of employment during the year.

Recent immigrant refers to an immigrant who first obtained his or her landed immigrant or permanent resident status in the five years prior to a given census.

Non-recent immigrant refers to an immigrant who first obtained his or her landed immigrant or permanent resident status more than five years prior to a given census. In the 2016 Census, this period refers to immigrants who landed prior to January 1, 2011.

Language of work

Since 2001, the Census of Population has included a two-part question on languages used in the workplace. Part A asks about the language used most often in the workplace, while Part B asks about the languages used regularly in the workplace, in addition to the main language, if applicable. For each part, multiple responses are accepted.

The expression "other language" refers to all languages other than English and French. It includes Aboriginal, immigrant and sign languages. Some data products also use the expression "non-official languages" to refer to the same concept.

2016 Census of Population products and releases

Today, Statistics Canada is releasing the sixth set of results from the 2016 Census of Population. These results focus on education, labour, journey to work and language of work in Canada.

Several 2016 Census products are also available today on the Census Program web module. This web module has been designed to provide easy access to census data, free of charge. Information is organized into broad categories, including analytical products, data products, reference materials, geography and a video centre.

Analytical products include an article from the Census in Brief series that focuses on work activity of seniors and another article that describes how the use of English, French and other languages in the workplace has evolved between 2006 and 2016.

Data products include the labour results for a wide range of standard geographic areas, available through the Data tables, Census Profile and Highlight tables.

In addition, the Focus on Geography Series provides data and highlights on key topics found in this Daily release and in the Census in Brief articles at various levels of geography.

Reference materials contain information to help understand census data. They include the Guide to the Census of Population, 2016, which summarizes key aspects of the census, as well as response rates and other data-quality information. They also include the Dictionary, Census of Population, 2016, which defines census concepts and variables, and the Labour Reference Guide and Languages Reference Guide, which explain census concepts and changes made to the 2016 Census. These reference guides also include information about data quality and historical comparability, and comparisons with other data sources. Both the Dictionary and the Guide to the Census of Population are updated with additional information throughout the release cycle.

Geography-related 2016 Census Program products and services can be found under Geography. These include GeoSearch, an interactive mapping tool, and thematic maps, which show labour data for Canada by economic region.

An infographic entitled Canadians in the workforce also illustrates some key findings, including changes in the full-year, full-time employment rate in 2005 and 2015 for Canada, the provinces and territories, by age group and sex, and family composition.

The public is also invited to chat with our experts on this topic.

November 29, 2017 marks the final major release from the 2016 Census of Population. Please see the 2016 Census Program release schedule for a full list of the topics that have already been released.

As well, consult the Census Program web module over the coming months for the release of additional data products providing an even more comprehensive picture of the Canadian population.

Contact information

For more information, or to enquire about the concepts, methods or data quality of this release, contact us (toll-free 1-800-263-1136; 514-283-8300; STATCAN.infostats-infostats.STATCAN@canada.ca) or Media Relations (613-951-4636; STATCAN.mediahotline-ligneinfomedias.STATCAN@canada.ca).

- Date modified: