Acknowledgments

This report is the result of a collaboration between the Government of Nunavut’s Department of Culture and Heritage and Statistics Canada’s Center for Demography and Center for Indigenous Statistics and Partnerships.

This study was made possible thanks to the valuable comments, insights and work of several key contributors. In particular the authors would like to thank Pierre Ducy, Allison Seguin, Isabelle Dika and Taylor Lavallee from the Government of Nunavut's Department of Culture and Heritage, Éric Caron-Malenfant, Marie Desnoyers, Julien Acaffou, and Mélanie Bélanger from Statistics Canada’s Center for Demography, as well as Vivian O’Donnell, Thomas Anderson and Tommy Akulukjuk from Statistics Canada’s Center for Indigenous Statistics and Partnerships.

Start of text box

- In 2021, close to two-thirds of Nunavut residents reported

Inuktut as their mother tongue, alone or together with another language

(62.7%), while one-third reported English as their sole mother tongue (33.1%).

Among Inuit, 73.1% had Inuktut as their mother tongue, where Inuktut

collectively refers to Inuktitut, Inuinnaqtun and other Inuit

languages.

- Younger Inuit were less likely to report Inuktut as their mother

tongue than older Inuit: 65.6% of Inuit under the age of 15 had Inuktut among

their mother tongues, compared with 90.9% of Inuit aged 55 and over.

- Over two thirds of Nunavut residents could converse in more than

one language (68.0%) in 2021. The most common forms of bilingualism were

Inuktut-English (62.4%) and English–French (3.8%).

- In 2021, 70.0% of Nunavut residents could conduct a conversation

in Inuktut, alone or together with another language. In contrast, 94.1% of

Nunavut residents could conduct a conversation in English, and 4.0% could

converse in French.

- Among Inuit, 81.0% could converse in Inuktut. Younger Inuit were

less likely to report the ability to converse in Inuktut, with 73.7% of Inuit

aged under 15 having knowledge of the language, compared with 96.2% of those

aged 55 and over. Among non-Inuit, 8.6% had knowledge of Inuktut, with

non-Inuit youth aged 15 to 24 having the highest proportion, at 15.4%.

- In 2021, about three in four Nunavut residents spoke English at

home at least on a regular basis (71.9%), alone or together with another

language, with English being the predominant home language of 46.6% of

residents. In contrast, 64.6% of Nunavut residents spoke Inuktut at home at

least on a regular basis, and 41.4% predominantly spoke Inuktut at home. Compared

with English (40.2%), Inuktut remained the predominant home language of a

larger proportion of Inuit (48.4%).

- Nearly all workers used English at work at least on a regular

basis in Nunavut (94.6%), while 42.8% used Inuktut at least on a regular basis.

Among Inuit workers, 43.2% used Inuktut most often at work, alone or together

with another language.

- Three-quarters of Nunavut residents with Inuktitut as a mother

tongue spoke the language predominantly at home (74.1%). In contrast, among

people whose mother tongue is Inuinnaqtun, one-fifth (20.2%) spoke the language

predominantly at home.

- About half of people with Inuinnaqtun as their mother tongue were

aged 55 and over. However, people who could conduct a conversation in

Inuinnaqtun as a second language had a lower median age than mother tongue

speakers (35 years versus 54 years), meaning that younger people were learning

Inuinnaqtun as a second language.

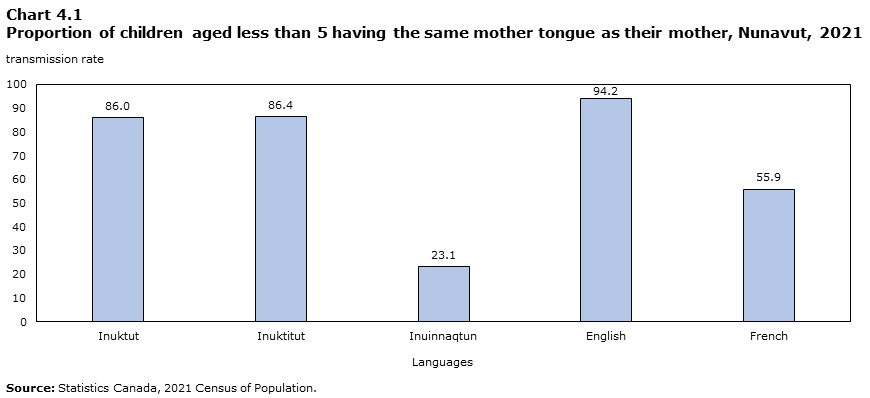

- Among children born to English-mother-tongue mothers, 94.2% had

the same mother tongue as their mother, alone or together with another

language. This proportion was lower among children born to mothers whose mother

tongue is Inuktitut (86.4%) or Inuinnaqtun (23.1%).

End of text box

1. Introduction

Nunavut stands

out in Canada: two-thirds of its population report an Inuit identity, and

Nunavut boasts the highest rate of bilingualism among provinces and

territories. In 2021, 68.0% of NunavummiutNote

could conduct a conversation in two or more languages, for the most part in

Inuktitut and English. Nunavut’s multilingualism is reflected in the fact it

has four official languages: Inuktitut, Inuinnaqtun,Note English and

French.

Inuktitut,

Inuinnaqtun and other Inuit languages are collectively referred to as Inuktut

languages. The Inuktut languages are indigenous to Inuit Nunangat,Note which

Nunavut is a part of, and most speakers of Inuktut languages are Inuit.

While language

is a vector for culture and identity, Indigenous languages have seen challenges

to their sustained use. In Canada, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission

documented the lasting impacts of discriminatory colonial policies that aimed

to eradicate the use of Inuktut and other Indigenous languages, notably through

the residential school system.Note

According to the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural

Organization (UNESCO), numerous Indigenous languages in Canada and around the

world are losing speakers and see their future threatened.Note The

organization launched the International Decade of Indigenous Languages in 2022

to shed light on the issue.

The persisting

and renewed use of Inuktut languages in Nunavut is a priority for the

territorial government. A longstanding goal of the Government of Nunavut is to

promote and support the use of Inuktut languages in all spheres of society, be

it in school, at work, or when accessing services provided by the government or

by the private sector, all while preserving the rights of English and French

speakers. The intended result is a fully bilingual society.Note In this

context, the Government of Nunavut mandated Statistics Canada to produce the

2019 report entitled “Evolution of the language situation in Nunavut, 2001 to 2016” to assess the progress towards this objective.

The findings

highlighted in the 2019 reportNote

included, for instance, that while the number of Nunavut residents whose mother

tongue is Inuktut or who could conduct a conversation in Inuktut is increasing,

their proportion has decreased from 2001 to 2016, especially in the Kitikmeot

region of western Nunavut. In particular, the rate of transmission of Inuktut

from parents to children has been decreasing. However, a growing proportion of

Nunavut residents spoke Inuktut at home, although increasingly as a second

language rather than as a main language.

Now that results

from the 2021 Census are available, the Government of Nunavut mandated

Statistics Canada to provide an up-to-date picture of the language situation in

Nunavut with results from the latest census. This report covers the mother

tongues and languages known, spoken at home or used at work among Inuit and

non-Inuit Nunavummiut. To provide explanation and context for these trends,

this report also examines factors associated with the growth or decline in the

number of speakers of Nunavut’s official languages, such as the

intergenerational transmission of language, home language retention, and

migrations to and from the territory. Key census results for each of Nunavut’s

three regions (Qikiqtaaluk, Kivalliq and Kitikmeot) and 25 communities are provided

in the appendix.

In addition, the

report provides results from the 2017 Aboriginal Peoples Survey that inform

other aspects of the language situation of Nunavut, such as the self-rated

ability to speak and understand Inuktut and the perceived importance of

speaking an Indigenous language.

1.1 Data sources and limits

This report is

based on data from the 2021 Census of Population and the 2017 Aboriginal

Peoples Survey.

The 2021 Census

of Population offers the most complete and up-to-date portrait of the languages

known and spoken by the population of Nunavut. However, data collection for the

2021 Census of Population occurred in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, which

presented unique challenges compared with past cycles. Some of these challenges,

such as travel restrictions and unavailability of local staff, affected

in-person enumeration. In fact, in 2021, early enumeration did not take place

as it did in the past in Nunavut, and data collection extended into the summer,

when many residents of Nunavut are away from home.

The 2021 Census

of Population in Nunavut differed from previous censuses because of a higher

rate of census net undercoverage,Note

the introduction of self-enumerationNote

and more extensive data imputation.Note

In addition, changes to the two-part questions on languages spoken at home and

languages used at work affected comparability with previous censuses.Note

Because of the

important differences between the 2021 Census and prior censuses in Nunavut, data

users should be cautious when comparing 2021 Census results on languages in

Nunavut with those of past cycles. In this report, selected comparisons with

prior cycles appear in text boxes where interpretations consider the specific

circumstances of the 2021 Census.

In Nunavut, the 2017

Aboriginal Peoples Survey covered the Indigenous population aged 15 and

over. Missing values (“don’t know,” “not stated” and “refusal”)

were excluded from the denominator when calculating percentages. In 2022, the

Aboriginal Peoples Survey was renamed the Indigenous Peoples Survey. At the

time this report was written, the 2022 Indigenous Peoples Survey data were not

yet available.

Start of text box

Inuit identity refers to

whether a person identified as Inuk (Inuit) in the census.

Mother tongue refers to

the first language learned at home in childhood and still understood by the

person at the time the data were collected.

Knowledge of a language

refers to whether a person reported they could conduct a conversation in the

language.

Language spoken at home

refers to a language a person spoke at home on a regular basis at the time of

data collection. People can report speaking languages at home at various

frequencies. A language is the only language spoken at home when it is

the only language reported by the person. A language is mostly spoken

at home when it is the only language spoken most often at home, but another

language is also spoken on a regular basis as a secondary language. People

who only or mostly speak a given language at home speak the language

predominantly. A language is spoken equally often at home when

another language is also spoken most often. A language is spoken only on a

regular basis as a secondary language when another language is spoken

most often at home.

Language used at work

refers to a language a person used at work on a regular basis at the time of

data collection. People can report using languages at work at various

frequencies. A language is the only language used at work when it is

the only language reported by the person. A language is mostly used at

work when it is the only language used most often at work, but another

language is also used on a regular basis as a secondary language. People who

use only or mostly a given language at work use the language predominantly.

A language is used equally often at work when another language is also

used most often. A language is used only on a regular basis as

a secondary language when another language is used most often at work.

Information on languages used at work is presented for people who were

employed during the census reference week.Note

In this report, the term region

refers to census divisions. The term community refers to census

subdivisions with a census population of 50 people or more.

Description of Map A1

This map shows the population size in the 25 communities of Nunavut in 2021. In this report, a community is a census subdivision (CSD) with a population of at least 50 people.

On the map, the 3 regions of Nunavut are represented by 3 different colours, where Qikiqtaaluk is represented by green, Kivalliq by blue and Kitikmeot by red. The communities are represented by circles whose size corresponds to the population size of that community.

There are 6 communities in Qikiqtaaluk (Grise Fiord, Resolute, Arctic Bay, Qikiqtarjuaq, Hall Beach and Kimmirut) with a population size between 145 and 999.

There are 5 communities in Qikiqtaaluk (Pond Inlet, Pangnirtung, Cape Dorset, Clyde River and Sanikiluaq) with a population size between 1,000 and 1,999.

There is 1 community in Qikiqtaaluk (Igloolik) with a population size between 2,000 and 2,999.

There is 1 community in Qikiqtaaluk (Iqaluit) with a population size between 3,000 and 7,420.

There are 2 communities in Kivalliq (Chesterfield Inlet and Whale Cove) with a population size between 145 and 999.

There are 2 communities in Kivalliq (Coral Harbour and Naujaat) with a population size between 1,000 and 1,999.

There are 3 communities in Kivalliq (Baker Lake, Arviat and Rankin Inlet) with a population size between 2,000 and 2,999.

There is 1 community in Kitikmeot (Taloyoak) with a population size between 145 and 999.

There are 4 communities in Kitikmeot (Kugaaruk, Gjoa Haven, Kugluktuk and Cambridge Bay) with a population size between 1,000 and 1,999.

End of text box

2. Inuit identity

Inuit have inhabited the territory of Nunavut since time

immemorial. In the Census of Population, people report whether they identify as

Inuk (Inuit). In this report, the Inuit population comprises all individuals who

reported an Inuit identity, alone or in combination with another Indigenous

identity.

In 2021, there were 31,050 Inuit in Nunavut, accounting for

84.4% of the total Nunavut population. Chart 2.1 shows the age structure

of the Nunavut population in 2021, by Inuit identity. The comparison between

the Inuit and non-Inuit populations in 2021 shows a clear disparity in the age

distribution, with Inuit being on average younger than non-Inuit. For instance,

in 2021, more than one-third of Inuit were aged under 15 (36.0%), compared with

15.8% of non-Inuit. In contrast, most of the non-Inuit population was in the

core working-age group, aged 25 to 54 (57.4%), while a smaller proportion of

Inuit was in this group (35.8%).

Data table for Chart 2.1

Data table for chart 2.1

Table summary

This table displays the results of Data table for chart 2.1. The information is grouped by Age group (appearing as row headers), Inuit and Non-Inuit, calculated using number of people units of measure (appearing as column headers).

| Age group |

Inuit |

Non-Inuit |

| number of people |

| 80 years and over |

160 |

15 |

| 75 to 79 years |

190 |

20 |

| 70 to 74 years |

405 |

70 |

| 65 to 69 years |

520 |

195 |

| 60 to 64 years |

820 |

350 |

| 55 to 59 years |

1,145 |

450 |

| 50 to 54 years |

1,485 |

495 |

| 45 to 49 years |

1,400 |

510 |

| 40 to 44 years |

1,550 |

550 |

| 35 to 39 years |

1,745 |

595 |

| 30 to 34 years |

2,415 |

590 |

| 25 to 29 years |

2,510 |

450 |

| 20 to 24 years |

2,620 |

210 |

| 15 to 19 years |

2,900 |

170 |

| 10 to 14 years |

3,475 |

215 |

| 5 to 9 years |

3,695 |

295 |

| 0 to 4 years |

4,015 |

365 |

Because of these differences in age distribution, the

proportion of the population who reported an Inuit identity is higher among

younger Nunavut residents. While 84.4% of all Nunavut residents were Inuit,

92.7% of those aged under 15 identified as Inuit. In contrast, just under three

in four Nunavut residents aged 35 and over (74.4%) were Inuit.

3. Languages in 2021

3.1 Mother tongue

In 2021, 62.7% of the Nunavut population reported an Inuktut

language as their mother tongue, alone or together with another language. More

specifically, over half of Nunavut residents reported Inuktitut as their only

mother tongue (52.2%), whereas 0.6% reported Inuinnaqtun as their sole mother

tongue.

Data table for Chart 3.1.1

Data table for chart 3.1.1

Table summary

This table displays the results of Data table for chart 3.1.1. The information is grouped by Languages (appearing as row headers), Percentage of population (appearing as column headers).

| Languages |

Percentage of population |

| Inuktut |

62.7 |

| Inuktitut only |

52.2 |

| Inuinnaqtun only |

0.6 |

| Inuktut n.i.e. |

0.1 |

| Inuktut and English |

9.8 |

| English only |

33.1 |

| French only |

1.4 |

| Other languages |

2.9 |

In total, 42.8% of Nunavut residents reported English as one

of their mother tongues, with 33.1% reporting English only and 9.8% reporting

both Inuktut and English as their mother tongues. People who participated in

the 2021 Census were more likely to report multiple mother tongues than in

prior censuses in Canada as a whole and in Nunavut in particular.Note

Start of text box

Increases

in the population with an Inuktut mother tongue stop in the 2021 Census

The number of

Nunavut residents reporting Inuktut as their mother tongue increased with each

census from 2001 to 2016, from 19,040 to 23,215 people. However, in 2021, the

number of people with an Inuktut mother tongue, alone or together with

another language, decreased by 300 speakers. The decline was more significant

among those reporting only Inuktut as their mother tongue (-3,225 speakers). However,

demographic factors alone (births, deaths, migration) cannot explain this

decrease.

The census

population in Nunavut was lower than expected in 2021, largely because of factors

associated with enumeration in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. This

lower census population is likely to have impacted the number of speakers of

Inuktut enumerated in the 2021 Census.

End of text box

About three-quarters (73.1%) of the Inuit population

reported an Inuktut mother tongue in 2021, alone or in combination with another

language, whereas 4.6% of non-Inuit reported the same. About two in five Inuit

reported English as one of their mother tongues (38.1%).

English was the most reported mother tongue among non-Inuit,

followed by French (8.8%). In addition, about one in five non-Inuit reported

languages other than Inuktut, English or French as their mother tongue in 2021

(18.0%). Among these other languages, Tagalog (240 speakers), Spanish (55

speakers), Arabic (45 speakers) and Urdu (30 speakers) were the most commonly

reported.

Data table for Chart 3.1.2

Data table for chart 3.1.2

Table summary

This table displays the results of Data table for chart 3.1.2 Inuktut, Inuktut and English, English only, French only and Other languages, calculated using percentage of population units of measure (appearing as column headers).

|

Inuktut |

Inuktut and English |

English only |

French only |

Other languages |

| percentage of population |

| Total |

52.9 |

9.8 |

33.1 |

1.4 |

2.9 |

| Inuit |

61.7 |

11.4 |

26.7 |

0.1 |

0.2 |

| Non-inuit |

3.6 |

1.0 |

68.7 |

8.8 |

18.0 |

Chart 3.1.3 shows the distribution of mother tongues by age

group among Inuit in 2021. The proportion of Inuit who reported Inuktut as

their only mother tongue was lower among younger age groups, at 54.4% among

children aged under 15 years and at 80.2% among adults aged 55 years and older.

Over 1 in 10 Inuit reported Inuktut and English as their mother tongues across

all age groups.

Data table for Chart 3.1.3

Data table for chart 3.1.3

Table summary

This table displays the results of Data table for chart 3.1.3. The information is grouped by Age group (appearing as row headers), Inuktut, Inuktut and English, English and Other languages, calculated using percentage of population units of measure (appearing as column headers).

| Age group |

Inuktut |

Inuktut and English |

English |

Other languages |

| percentage of population |

| 0 to 14 years |

54.4 |

11.2 |

34.1 |

0.3 |

| 15 to 24 years |

58.2 |

10.6 |

31.0 |

0.3 |

| 25 to 39 years |

61.9 |

12.0 |

25.9 |

0.3 |

| 40 to 54 years |

70.5 |

12.5 |

16.8 |

0.2 |

| 55 years and over |

80.2 |

10.7 |

8.9 |

0.2 |

In contrast, the proportion of Inuit who reported only

English as their mother tongue was higher in younger age groups. About

one-third (34.1%) of Inuit children (0 to 14 years) had English as their only

mother tongue, and this proportion was 8.9% among Inuit aged 55 years and over.

Start of text box

The

relative proportion of people with an Inuktut mother tongue is decreasing in

Nunavut

The

proportion of Nunavut residents whose sole mother tongue was Inuktut decreased

from 2001 (69.6%) to 2016 (61.9%). This trend continued in 2021, with the

proportion falling to 52.9%. However, this decrease was less steep when

taking into account all people who reported an Inuktut mother tongue, alone

or together with another language—their proportion went from 65.3% in 2016 to

62.6% in 2021, down from 71.2% in 2001. The proportion of Inuit who reported

an Inuktut mother tongue, alone or together with another language, also

decreased from 2001 (84.3%) to 2016 (76.6%) and 2021 (73.1%).

People who

participated in the 2021 Census were more likely to report multiple mother

tongues than in past cycles. This was observed in Canada as a whole and in

Nunavut in particular. In Nunavut, the introduction of self-enumeration

and the electronic questionnaire for the 2021 Census might have played a

role, among other factors, with more people providing a different response to

the mother tongue question compared with past cycles, by reporting for

example both Inuktut and English as mother tongues rather than only Inuktut.

End of text box

3.2 Knowledge of languages

In the census, the knowledge of a language refers to the

capacity to conduct a conversation in that language.

In 2021, over two-thirds of Nunavut residents reported being

able to converse in Inuktut in 2021, alone or in combination with another

language (70.0%). About 4 out of 5 Inuit reported being able to speak in

Inuktitut specifically (79.4%) whereas only 8.5% non-Inuit could converse in

the language in 2021. A much smaller proportion of Nunavut residents reported

ability to converse in Inuinnaqtun (1.4%).

Data table for Chart 3.2.1

Data table for chart 3.2.1

Table summary

This table displays the results of Data table for chart 3.2.1 Total, Inuit and Non-Inuit, calculated using percentage of population units of measure (appearing as column headers).

|

Total |

Inuit |

Non-Inuit |

| percentage of population |

| Inuktut |

70.0 |

81.0 |

8.6 |

| Inuktitut |

68.7 |

79.4 |

8.5 |

| Inuinnaqtun |

1.4 |

1.7 |

0.1 |

| English |

94.1 |

93.3 |

99.1 |

| French |

4.0 |

0.8 |

21.7 |

Over 9 in 10 people in Nunavut reported being able to

conduct a conversation in English, alone or in combination with another

language (94.1%). As highlighted by chart 3.2.1, this proportion varied by

Inuit identity, the proportion of persons who could converse in English being

marginally lower among the Inuit (93.3%) than among the non-Inuit (99.1%).

Start of text box

The

proportion of Inuit who report knowledge of Inuktut is trending downward, while

the proportion is increasing among non-Inuit

The proportion

of Inuit who could conduct a conversation in Inuktut slightly

decreased from 2001 (91.5%) to 2016 (89.0%). This proportion fell markedly in

2021 to 81.0%. Knowledge of Inuktut among Inuit decreased among all age

groups from 2016 to 2021, especially among people aged under 55 years. While

people may lose the capacity to conduct a conversation in a language over

time, these results might also be explained by the specific circumstances

of enumeration in the 2021 Census.

Among

non-Inuit, the proportion who could conduct a conversation in Inuktut rose

from 7.3% in 2001 to 8.3% in 2016, and continued growing in 2021, reaching

8.6%.

End of text box

Charts 3.2.2 and 3.2.3 compare the knowledge of languages of

Inuit and non-Inuit by age group.

The proportion of Inuit who reported being able to converse

in an Inuktut language was higher among older age groups. The proportion of

Inuit who could conduct a conversation in Inuktut ranged from 73.7% among

children (under 15 years) to 96.2% among older adults (55 years and over).

Data table for Chart 3.2.2

Data table for chart 3.2.2

Table summary

This table displays the results of Data table for chart 3.2.2. The information is grouped by Languages (appearing as row headers), Total, 0 to 14 years, 15 to 24 years, 25 to 39 years, 40 to 54 years and 55 years and over, calculated using percentage of population units of measure (appearing as column headers).

| Languages |

Total |

0 to 14 years |

15 to 24 years |

25 to 39 years |

40 to 54 years |

55 years and over |

| percentage of population |

| Inuktut |

81.0 |

73.7 |

76.9 |

82.6 |

91.0 |

96.2 |

| English |

93.3 |

85.6 |

99.1 |

99.4 |

98.1 |

90.2 |

| French |

0.8 |

0.7 |

0.8 |

0.7 |

1.2 |

0.7 |

Over 9 in 10 Inuit reported the ability to conduct a

conversation in English across all age groups, except children aged 0 to 14

years, among whom the proportion of English speakers was a little lower (85.6%).

In 2021, almost all non-Inuit reported being able to converse in English

(99.1%).

Start of text box

Box B: How important is it to Inuit in Nunavut

to speak and understand an Indigenous language? How often are they exposed to

an Indigenous language?

The vast

majority of Inuit aged 15 and over in Nunavut reported that speaking and

understanding an Indigenous language was important. Among the 19,720 Inuit

aged 15 and over living in Nunavut in 2017, as estimated by the Aboriginal

Peoples Survey, about 9 in 10 (86%) reported that it was “very important,”

and another 1 in 10 (11%) said that it was “somewhat important.” The

remaining Inuit of this age group in the territory said that speaking and

understanding an Indigenous language was either “not very important” or “not

important” or reported not having an opinion on the subject.

Almost all

Inuit aged 15 and over in Nunavut (99%) reported that they were exposed to an

Indigenous language either at home or outside the home. Many were frequently

exposed to an Indigenous language in both environments. In 2017, about 8 in

10 (78%) of the 19,720 Inuit aged 15 and over living in Nunavut reported

being exposed to an Indigenous language “on a daily basis” both at home and

outside the home.

End of text box

Data table for Chart 3.2.3

Data table for chart 3.2.3

Table summary

This table displays the results of Data table for chart 3.2.3. The information is grouped by Languages (appearing as row headers), Total, 0 to 14 years, 15 to 24 years, 25 to 39 years, 40 to 54 years and 55 years and over, calculated using percentage of population units of measure (appearing as column headers).

| Languages |

Total |

0 to 14 years |

15 to 24 years |

25 to 39 years |

40 to 54 years |

55 years and over |

| percentage of population |

| Inuktut |

8.6 |

9.6 |

15.4 |

7.7 |

7.4 |

8.4 |

| English |

99.1 |

95.6 |

100.0 |

99.8 |

99.7 |

99.5 |

| French |

21.7 |

20.5 |

15.2 |

25.6 |

22.1 |

18.5 |

In 2021, while over four in five Inuit

could conduct a conversation in Inuktut (81.0%), a much lower proportion of

non-Inuit could converse in the language (8.6%). However, this proportion was

almost double among non-Inuit aged 15 to 24, 15.4% of whom could conduct a

conversation in Inuktut.

About one in five non-Inuit in Nunavut could conduct a

conversation in French (21.7%). This was the case of 1.0% of Inuit.

Over half of Nunavut residents (53.8%) who reported

knowledge of English did not acquire English as their mother tongue but instead

learned English later in life, as a second language. This proportion was

highest among Inuit, three in five of whom learned English as a second language

(59.2%).

Data table for Chart 3.2.4

Data table for chart 3.2.4

Table summary

This table displays the results of Data table for chart 3.2.4. The information is grouped by Knowledge of languages (appearing as row headers), Mother tongue speakers and Second language speakers, calculated using percentage of population units of measure (appearing as column headers).

| Knowledge of languages |

Mother tongue speakers |

Second language speakers |

| percentage of population |

| Total |

|

| Inuktitut |

88.6 |

11.4 |

| Inuinnaqtun |

63.9 |

36.1 |

| English |

46.2 |

53.8 |

| French |

44.5 |

55.5 |

| Inuit |

|

| Inuktitut |

89.3 |

10.7 |

| Inuinnaqtun |

64.5 |

35.5 |

| English |

40.8 |

59.2 |

| French |

25.9 |

74.1 |

| Non-Inuit |

|

| Inuktitut |

51.3 |

48.7 |

| Inuinnaqtun |

14.3 |

85.7 |

| English |

74.8 |

25.2 |

| French |

48.7 |

51.3 |

About 1 in 10 Nunavut residents who could converse in

Inuktitut spoke it as a second language (11.4%), whereas almost 4 in 10

Inuinnaqtun speakers had learned it as a second language (36.1%). Almost half

of non-Inuit who could speak Inuktitut had learned it as a second language

(48.7%), while 10.7% of Inuit who could conduct a conversation in Inuktitut

were second-language speakers.

Start of text box

Box C: How well is Inuktut spoken: very well,

relatively well, with effort or only a few words? How well is Inuktut

understood?

The previous

section showed information about Inuit in Nunavut who spoke Inuktut well

enough to conduct a conversation based on census data. In Box C, language

data from the 2017 Aboriginal Peoples Survey are used to provide

complementary insights into how Inuit in Nunavut rated their ability to speak

Inuktut, from “only a few words” to “very well,” in addition to how well they

understood the language.

In 2017,

among the estimated 19,720 Inuit aged 15 and over living in Nunavut, 97% said

that they could speak at least a few words of Inuktut.

The majority

of Inuit aged 15 and over in Nunavut who spoke Inuktut in 2017 said they

speak it “very well” (65%), while another 15% said they speak it “relatively

well.” By contrast, 11% were able to speak “only a few words” of Inuktut,

while the remaining 9% said they could speak it “with effort” (Chart C.1).Note

However, a

minimal ability to speak Inuktut does not necessarily mean that the language

is not well understood. Among the 3,700 Inuit aged 15 and over who spoke

Inuktut with effort or who could speak only a few words, about 40% reported being

able to understand it either “relatively well” or “very well.”

Data table for Chart C.1

Data table for chart C.1

Table summary

This table displays the results of Data table for chart C.1 Speaks very well, Speaks relatively well, Speaks with effort and Speak only a few words, calculated using percent units of measure (appearing as column headers).

|

Speaks very well |

Speaks relatively well |

Speaks with effort |

Speak only a few words |

| percent |

| Inuit aged 15 and over speaking Inuktut |

65 |

15 |

9 |

11 |

The

self-rated ability to speak Inuktut varied by age group. Older adults were

more likely to speak Inuktut well compared with Inuit youth. Among Inuktut

speakers, almost all Inuit aged 55 and over (97%) and about 84% of Inuit aged

25 to 54 reported speaking Inuktut very well or relatively well. The

proportion was lower for Inuit youth. Among Inuit youth aged 15 to 24 who

could speak Inuktut, about 65% said they speak the language very well or

relatively well (Chart C.2).

While about

one-third of Inuit youth reported speaking Inuktut with effort or only a few

words, a number could understand it very well or relatively well. Among the

1,870 Inuit youth aged 15 to 24 who were unable to speak Inuktut well, 37%

could still understand it well.

Data table for Chart C.2

Data table for chart C.2

Table summary

This table displays the results of Data table for chart C.2 Speaks very well or relatively well , Speaks with effort or only a few words, percentage and 95% confidence interval, calculated using lower limit and upper limit units of measure (appearing as column headers).

|

Speaks very well or relatively well |

Speaks with effort or only a few words |

| percentage |

95% confidence interval |

percentage |

95% confidence interval |

| lower limit |

upper limit |

lower limit |

upper limit |

| Aged 15 and over |

80 |

78 |

83 |

20 |

17 |

22 |

| Aged 15 to 24 |

65Note * |

60 |

70 |

35 |

30 |

39 |

| Aged 25 to 54 |

84Data table for chart C.2 Note † |

80 |

87 |

16 |

13 |

20 |

| Aged 55 and over |

97Note * |

94 |

98 |

3Note E: Use with caution |

2 |

6 |

End of text box

3.3 Bilingualism and multilingualism

Bilingualism refers to the capacity to conduct a

conversation in two languages, while multilingualism refers to the ability to

converse in three languages or more.

Among Canada’s provinces and territories, Nunavut stands out

as having the highest rate of bilingualism among its population. In 2021, over

two-thirds of the Nunavut population could conduct a conversation in two or

more languages (68.0%), with about 2.2% among them being able to converse in three

or more languages. In 2021, the rate of bilingualism was higher among Inuit (73.9%)

than among non-Inuit (35.2%). However, about 1 in 10 non-Inuit could converse

in three or more languages (9.8%), while very few Inuit could (0.9%).

Data table for Chart 3.3.1

Data table for chart 3.3.1

Table summary

This table displays the results of Data table for chart 3.3.1 Monolingual, Bilingual and Mutilingual, calculated using percentage of population units of measure (appearing as column headers).

|

Monolingual |

Bilingual |

Mutilingual |

| percentage of population |

| Total |

29.8 |

68.0 |

2.2 |

| Inuit |

25.2 |

73.9 |

0.9 |

| Non-Inuit |

55.0 |

35.2 |

9.8 |

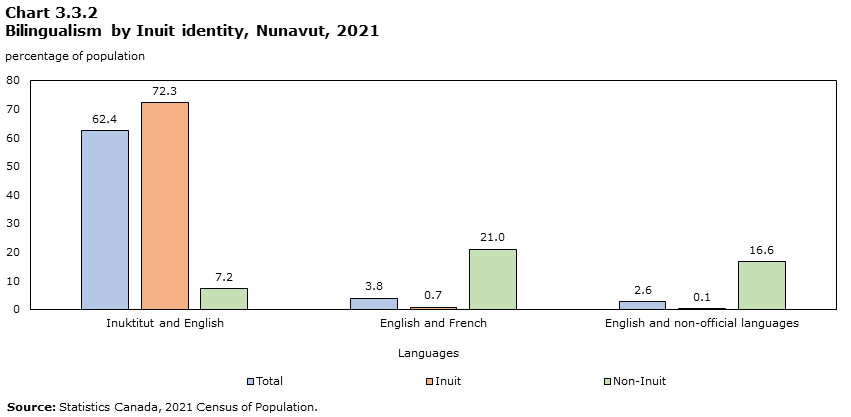

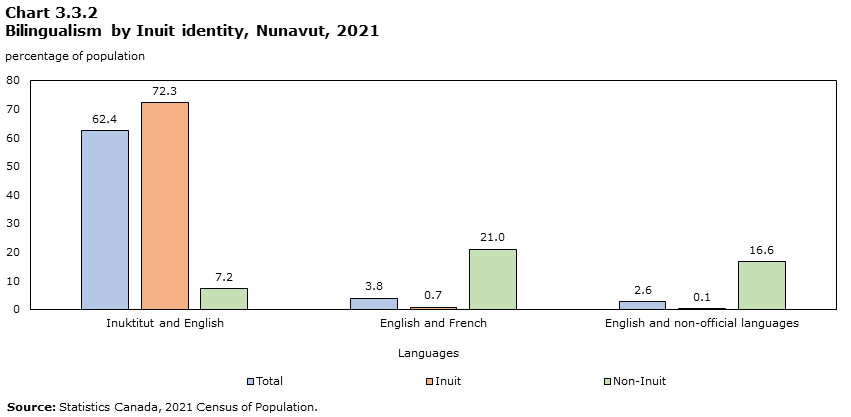

The most common form of bilingualism

observed among Inuit was Inuktitut-English: almost three in four Inuit (72.3%)

reported they could converse in both Inuktitut and English in 2021. In contrast

with Inuit, the most common form of bilingualism reported by non-Inuit in

Nunavut was English and French. In 2021, one in five non-Inuit reported being

able to converse in both English and French (21.0%).

Data table for Chart 3.3.2

Data table for chart 3.3.2

Table summary

This table displays the results of Data table for chart 3.3.2. The information is grouped by Languages (appearing as row headers), Total, Inuit and Non-Inuit, calculated using percentage of population units of measure (appearing as column headers).

| Languages |

Total |

Inuit |

Non-Inuit |

| percentage of population |

| Inuktitut and English |

62.4 |

72.3 |

7.2 |

| English and French |

3.8 |

0.7 |

21.0 |

| English and non-official languages |

2.6 |

0.1 |

16.6 |

3.4 Languages spoken at home

Many Nunavut residents speak more than one language at home.

In 2021, about two in five Nunavut residents spoke two languages or more at

least on a regular basis at home (40.6%). In contrast, this proportion was

18.6% in Canada as a whole.

English was the most commonly spoken home language in

Nunavut, with about three-quarters (71.9%) of Nunavut residents speaking

English at home at least on a regular basis, alone or together with another

language. Close to half of Nunavut residents predominantly spoke English at

home (46.6%), meaning they spoke this language most often at home, without

speaking other languages equally often.

Table 3.4

Distribution of languages spoken at home by frequency, Nunavut, 2021

Table summary

This table displays the results of Distribution of languages spoken at home by frequency. The information is grouped by Languages (appearing as row headers), Frequency of language spoken at home, Total, Only, Mostly, Equally and Regularly, calculated using number and percent units of measure (appearing as column headers).

| Languages |

Frequency of language spoken at home |

| Total |

Only language spoken at home |

Language spoken most often, with another language spoken on a regular basis |

Language spoken equally most often with another language |

Language spoken on a regular basis, with another language spoken most often |

| number |

percent |

number |

percent |

number |

percent |

number |

percent |

number |

percent |

| Inuktut |

23,630 |

64.6 |

9,885 |

27.0 |

5,260 |

14.4 |

3,525 |

9.6 |

4,955 |

13.5 |

| Inuktitut |

23,280 |

63.6 |

9,855 |

26.9 |

5,225 |

14.3 |

3,485 |

9.5 |

4,725 |

12.9 |

| Inuinnaqtun |

340 |

0.9 |

30 |

0.1 |

25 |

0.1 |

40 |

0.1 |

240 |

0.7 |

| English |

26,315 |

71.9 |

11,630 |

31.8 |

5,425 |

14.8 |

3,760 |

10.3 |

5,500 |

15.0 |

| French |

705 |

1.9 |

235 |

0.6 |

105 |

0.3 |

110 |

0.3 |

260 |

0.7 |

Inuktut was the second most commonly spoken

language at home in the territory, with almost two-thirds of people in Nunavut

speaking Inuktut at home at least on a regular basis (64.6%). In particular, 41.4%

of the Nunavut population predominantly spoke Inuktitut at home in 2021.

However, Inuktut remained the language

spoken predominantly at home by the largest share of Inuit (48.4%), as seen in

Chart 3.4.1. Furthermore, about 1 in 10 Inuit in Nunavut spoke equally most

often a combination of Inuktut and English at home (11.2%) in 2021. Among

non-Inuit, 2.1% spoke Inuktut predominantly at home and 0.8% spoke Inuktut and

English equally most often.

Data table for Chart 3.4.1

Data table for chart 3.4.1

Table summary

This table displays the results of Data table for chart 3.4.1 English only, Inuktut and English, Inuktut, French only and Other languages, calculated using percentage of population units of measure (appearing as column headers).

|

English only |

Inuktut and English |

Inuktut |

French only |

Other languages |

| percentage of population |

| Total |

46.6 |

9.6 |

41.4 |

0.9 |

1.5 |

| Inuit |

40.2 |

11.2 |

48.4 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

| Non-Inuit |

82.3 |

0.8 |

2.1 |

5.8 |

9.1 |

The proportion of Inuit who predominantly

spoke English at home was half that of non-Inuit (40.2% among Inuit and 82.3%

among non-Inuit). Almost one in six non-Inuit predominantly spoke a language

other than English or Inuktut at home (14.8%), such as French (5.8%). Very few

Inuit predominantly spoke a language other than English or Inuktut at home (0.1%).

Start of text box

Change to the question on languages spoken at home in the 2021

Census

In the 2021 Census, the wording of the question on languages

spoken at home was modified to improve data quality and alleviate response

burden. Across Canada, this change impacted the comparability of results

pertaining to all languages spoken at home and languages spoken at home on a

regular basis, which should not be compared with those of prior cycles. The

results on languages spoken most often at home remain comparable with those

of prior cycles in Canada, with caution when interpreting multiple responses.

The change to the home language question occurred in the context

of challenges with data collection in Nunavut in 2021. In Nunavut, the

proportion of Inuit speaking Inuktut predominantly at home fell from 67.4% in

2001 to 58.4% in 2016, and then decreased to 48.4% in 2021. However, the

proportion of Inuit who spoke both Inuktut and English equally most often at

home increased from 1.6% in 2016 to 11.2% in 2021. As a result, the

proportion of Inuit who spoke Inuktut most often at home, alone or together

with English, remained fairly stable (from 60.0% in 2016 to 59.6% in 2021).

Among non-Inuit, the proportion who spoke predominantly Inuktut at

home increased from 2001 (0.8%) to 2016 (1.4%) and 2021 (2.1%).

End of text box

3.5 Languages used at work

Nunavut workers were more likely to use more than one

language at work than other workers in Canada. In 2021, about two in five

Nunavut workersNote

used more than one language at work (39.7%), while this was the case for 11.7%

of workers nationally.

English was overall the most commonly used language in

Nunavut workplaces: 94.6% of workers reported using it at least on a regular

basis, alone or together with another language, while 42.8% of workers reported

using Inuktitut at least on a regular basis. In contrast, 2.5% of workers used

French at work at least on a regular basis, and very few workers used

Inuinnaqtun (0.5%).

Almost three out of four Nunavut workers (70.1%) reported

predominantly using English at work, while 17.6% predominantly used Inuktut.

Table 3.5

Distribution of languages used at work by frequency, Nunavut, 2021

Table summary

This table displays the results of Distribution of languages used at work by frequency. The information is grouped by Languages (appearing as row headers), Frequency of language spoken at work, Total, Only, Mostly, Equally and Regularly, calculated using number and percent units of measure (appearing as column headers).

| Languages |

Frequency of language spoken at work |

| Total |

Only language used at work |

Language used most often, with another language used on a regular basis |

Language used equally most often with another language |

Language used on a regular basis, with another language used most often |

| number |

percent |

number |

percent |

number |

percent |

number |

percent |

number |

percent |

| Inuktut |

5,115 |

42.8 |

625 |

5.2 |

1,485 |

12.4 |

1,390 |

11.6 |

1,610 |

13.5 |

| Inuktitut |

5,055 |

42.3 |

625 |

5.2 |

1,485 |

12.4 |

1,380 |

11.6 |

1,580 |

13.2 |

| Inuinnaqtun |

60 |

0.5 |

- |

0.0 |

- |

0.0 |

10 |

0.1 |

45 |

0.4 |

| English |

11,295 |

94.6 |

6,560 |

54.9 |

1,815 |

15.2 |

1,405 |

11.8 |

1,510 |

12.6 |

| French |

295 |

2.5 |

25 |

0.2 |

20 |

0.2 |

25 |

0.2 |

225 |

1.9 |

Chart 3.5.1 shows that a majority of Inuit workers

predominantly worked in English (56.8%), while 43.2% of Inuit workers used Inuktut

most often at work, alone or in combination with English.

Data table for Chart 3.5.1

Data table for chart 3.5.1

Table summary

This table displays the results of Data table for chart 3.5.1 Inuktut, Inuktut and English, English only, French only and Other languages, calculated using percentage of population units of measure (appearing as column headers).

|

Inuktut |

Inuktut and English |

English only |

French only |

Other languages |

| percentage of population |

| Total |

17.7 |

11.6 |

70.1 |

0.4 |

0.2 |

| Inuit |

26.2 |

17.0 |

56.8 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

| Non-Inuit |

0.5 |

0.7 |

97.1 |

1.2 |

0.5 |

Nearly all non-Inuit workers used

English predominantly at work (97.1%) in 2021, while only 1.2 % of non-Inuit workers

used Inuktut most often at work, alone or in combination with English.

Overall, 30.2% of workers were employed in public administration. A similar proportion

of workers who predominantly used English at work were employed in this sector

(32.6%). Additionally, over one-quarter of the workers who used a combination

of Inuktitut and English (27.2%) and just under one-quarter of those who used

only Inuktitut most often (24.1%) at work were employed in the public

administration sector.

Start of text box

Change to the question on languages used at work in the 2021

Census

In the 2021 Census, the wording of the question on languages used

at work was changed to improve data quality and alleviate response burden.

Across Canada, this change impacted the comparability of results pertaining

to languages used at work on a regular basis or equally most often with

another language. In Nunavut in particular, the change to the question

occurred in the context of challenges to enumeration.Note

Moreover, data collection occurred in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic,

which impacted the world of work, such as employment rates, the distribution

of employment in different industry sectors, and the occurrence of work from

home.Note

In Nunavut, the proportion of Inuit workers using Inuktut

predominantly at work fell from 45.3% in 2001 to 36.1% in 2016, and then to 26.2%

in 2021. In contrast, few Inuit workers reported using Inuktut and English

equally most often at work in 2016 (2.3%), while their proportion was 17.0%

in 2021. Therefore, the proportion of Inuit workers who used Inuktut most

often at work, alone or equally most often with another language, rose from

38.3% in 2016 to 43.2% in 2021.

End of text box

Overall, one-third of workers who used an Inuktut language

predominantly at work were either in educational services (15.8%) or in

wholesale and retail trade (16.3%). A lower proportion of workers working

predominantly in English were in these sectors (9.7% and 12.3%, respectively).

Start of text box

Box D: Nunavut Land Claims Agreement beneficiaries in and outside Nunavut

The 2021 Census was the first to collect information on people who

are enrolled under, or beneficiaries of, Inuit land claims agreements. These

agreements cover issues such as land titles, fishing and trapping rights, and

financial compensation.

In 2021, 29,670 Nunavut residents were enrolled under a land

claims agreement, representing 81.1% of the territory’s population. Nearly

all of them were Inuit (99.8%) and enrolled specifically under the Nunavut

Land Claims Agreement (99.2%).Note

While some Nunavut Inuit residents were not enrolled under a land claims

agreement (1,430 people), 3,880 people who were enrolled under the Nunavut

Land Claims Agreement resided outside Nunavut. A few of these beneficiaries

resided elsewhere in Inuit NunangatNote

(1.8%), but most resided in large urban centresNote

in southern Canada (61.4%), such as Ottawa–Gatineau (24.1%), Winnipeg (7.0%)

and Edmonton (6.4%).

Data table for Chart D.1

Data table for chart D.1

Chart summary

This table displays the results of Data table for chart D.1 Total, Reside in Nunavut and Reside outside Nunavut, calculated using percentage units of measure (appearing as column headers).

|

Total |

Reside in Nunavut |

Reside outside Nunavut |

| percentage |

| Can conduct a conversation in Inuktut |

76.1 |

82.0 |

31.2 |

| Has an Inuktut mother tongue |

68.7 |

74.1 |

27.5 |

| Speaks Inuktut at home at least on a regular basis |

69.8 |

76.0 |

22.6 |

| Uses Inuktut at work at least on a regular basis |

55.9 |

62.4 |

14.8 |

People

enrolled under the Nunavut Land Claims Agreement who

live outside Inuit Nunangat were less likely to be able to conduct a

conversation in Inuktut, have Inuktut as a mother tongue, and speak Inuktut

at home or use it at work. About three-quarters of beneficiaries in Nunavut

had Inuktut as their mother tongue (74.1%), more specifically either

Inuktitut (61.7%), Inuktitut and English (11.2%), Inuinnaqtun (0.7%), or Inuinnaqtun and English (0.4%). Outside Nunavut, a little over one-quarter of

beneficiaries had Inuktut as their mother tongue (27.5%), more specifically

Inuktitut (21.0%), Inuktitut and English (4.9%), Inuinnaqtun (1.0%), or

Inuinnaqtun and English (0.2%).

End of text box

3.6 Differences between regions and communities

Knowledge and use of languages varies by region and community

in Nunavut. Key results for each region and community of Nunavut are featured

in the appendix.

Almost all Kitikmeot residents were able to converse in

English (99.2%), whereas knowledge

of the language was not as widespread in Qikiqtaaluk (92.1%) and Kivalliq (94.8%).

In contrast, the proportion of residents who could converse in an Inuktut

language was almost twice as high in the regions of Qikiqtaaluk (74.2%) and

Kivalliq (80.9%) compared with Kitikmeot (38.8%).

About 1 in 20 Nunavut residents could conduct a conversation

in French in Nunavut as a whole (4.0%). This proportion was higher in the

community of Iqaluit, where almost one in six people (15.2%) could converse in

French.

Less than 2% of Nunavut residents could conduct a

conversation in Inuinnaqtun, except in the Kitikmeot communities of Kugluktuk

(18.3%) and Cambridge Bay (15.0%).

A little under three in four residents in Qikiqtaaluk (70.4%)

and Kivalliq (70.7%) had an Inuktut language as their mother tongue, whereas

only one in four residents in Kitikmeot (25.7%) reported the same. However, the

region of Kitikmeot had almost three times the proportion of residents with only

English as their mother tongue (72.4%) compared with the regions of Qikiqtaaluk

(23.2%) and Kivalliq (27.4%). Almost 1 in 10 residents (9.6%) in Iqaluit had a

mother tongue other than English, French or Inuktut, much higher than the

overall proportion for Nunavut (2.9%).

Across Nunavut, over half of residents spoke an Inuktut

language most often at home, alone or together with another language (51.0%).

This holds true for the regions of Qikiqtaaluk and Kivalliq, where 62.6% and

54.8% of residents respectively spoke an Inuktut language most often at home.

In contrast, only 1 in 10 Kitikmeot residents spoke an Inuktut language most

often at home (9.5%).

Description for Map 3.6.1

This map shows the proportion of the population with an Inuktut mother tongue in the communities of Nunavut in 2021. In this report, a community is a census subdivision with a population of at least 50 people.

On the map, the 3 regions of Nunavut are represented by 3 different colours where Qikiqtaaluk is represented by green, Kivalliq by blue and Kitikmeot by red. The communities are represented by circles whose size corresponds to the population size of that community. The colour of the circles represent the proportion of the population with an Inuktut mother tongue.

In Qikiqtaaluk, 1 community (Resolute) had a population size between 145 and 999, and 40.0% to 64.9% had Inuktut as their mother tongue.

In Qikiqtaaluk, 1 community (Grise Fiord) had a population size between 145 and 999, and 65.0% to 89.9% had Inuktut as their mother tongue.

In Qikiqtaaluk, 4 communities (Arctic Bay, Qikiqtarjuaq, Hall Beach and Kimmirut) had a population size between 145 and 999, and 90.0% to 100.0% had Inuktut as their mother tongue.

In Qikiqtaaluk, 5 communities (Pond Inlet, Clyde River, Pangnirtung, Cape Dorset and Sanikiluaq) had a population size between 1,000 and 1,999, and 90.0% to 100.0% had Inuktut as their mother tongue.

In Qikiqtaaluk, 1 community (Igloolik) had a population size between 2,000 and 2,999, and 90.0% to 100.0% had Inuktut as their mother tongue.

In Qikiqtaaluk, 1 community (Iqaluit) had a population size between 3,000 and 7,420, and under 40.0% had Inuktut as their mother tongue.

In Kivalliq, 2 communities (Chesterfield Inlet and Whale Cove) had a population size between 145 to 999, and 65.0% to 89.9% had Inuktut as their mother tongue.

In Kivalliq, 1 community (Coral Harbour) had a population size between 1,000 to 1,999, and 65.0% to 89.9% had Inuktut as their mother tongue.

In Kivalliq, 1 community (Naujaat) had a population size between 1,000 to 1,999, and 90.0% to 100.0% had Inuktut as their mother tongue.

In Kivalliq, 2 communities (Baker Lake and Rankin Inlet) had a population size between 2,000 to 2,999, and 40.0% to 64.9% had Inuktut as their mother tongue.

In Kivalliq, 1 community (Arviat) had a population size between 2,000 to 2,999, and 90.0% to 100.0% had Inuktut as their mother tongue.

In Kitikmeot, 1 community (Taloyoak) had a population size between 145 to 999, and under 40.0% had Inuktut as their mother tongue.

In Kitikmeot, 4 communities (Kugluktuk, Cambridge Bay, Gjoa Haven and Kugaaruk) had a population size between 1,000 to 1,999, and under 40.0% had Inuktut as their mother tongue.

Description for Map 3.6.2

This map shows the distribution of the knowledge of Inuktut among the communities of Nunavut in 2021. In this report, a community is a census subdivision with a population of at least 50 people.

On the map, the 3 regions of Nunavut are represented by 3 different colours where Qikiqtaaluk is represented by green, Kivalliq by blue and Kitikmeot by red. The communities are represented by circles whose size corresponds to the population size of that community. The colour of the circles represent the proportion of the population that could conduct a conversation in Inuktut.

In Qikiqtaaluk, 1 community (Resolute) had a population size between 145 to 999, and 40.0% to 64.9% were able to conduct a conversation in Inuktut.

In Qikiqtaaluk, 1 community (Grise Fiord) had a population size between 145 to 999, and 65.0% to 89.9% were able to conduct a conversation in Inuktut.

In Qikiqtaaluk, 2 communities (Arctic Bay, Qikiqtarjuaq, Hall Beach and Kimmirut) had a population size between 145 to 999, and 90.0% to 100.0% were able to conduct a conversation in Inuktut.

In Qikiqtaaluk, 5 communities (Pond Inlet, Clyde River, Pangnirtung, Cape Dorset and Sanikiluaq) had a population size between 1,000 to 1,999, and 90.0% to 100.0% were able to conduct a conversation in Inuktut.

In Qikiqtaaluk, 1 community (Igloolik) had a population size between 2,000 to 2,999, and 90.0% to 100.0% were able to conduct a conversation in Inuktut.

In Qikiqtaaluk, 1 community (Iqaluit) had a population size between 3,000 to 7,420, and 40.0% to 64.9% were able to conduct a conversation in Inuktut.

In Kivalliq, 2 communities (Chesterfield Inlet and Whale Cove) had a population size between 145 to 999, and 65.0% to 89.9% were able to conduct a conversation in Inuktut.

In Kivalliq, 2 communities (Coral Harbour and Naujaat) had a population size between 1,000 to 1,999, and 90.0% to 100.0% were able to conduct a conversation in Inuktut.

In Kivalliq, 1 community (Baker Lake) had a population size between 2,000 to 2,999, and 40.0% to 64.9% were able to conduct a conversation in Inuktut.

In Kivalliq, 1 community (Rankin Inlet) had a population size between 2,000 to 2,999, and 65.0% to 89.9% were able to conduct a conversation in Inuktut.

In Kivalliq, 1 community (Arviat) had a population size between 2,000 to 2,999, and 90.0% to 100.0% were able to conduct a conversation in Inuktut.

In Kitikmeot, 1 community (Taloyoak) had a population size between 145 to 999, and 40.0% to 64.9% were able to conduct a conversation in Inuktut.

In Kitikmeot, 1 community (Gjoa Haven) had a population size between 1,000 to 1,999, and 40.0% to 64.9 were able to conduct a conversation in Inuktut.

In Kitikmeot, 3 communities (Kugluktuk, Cambridge Bay and Kugaaruk) had a population size between 1,000 to 1,999, and under 40.0% were able to conduct a conversation in Inuktut.

4. Factors associated with change in the number of speakers

4.1 Intergenerational

transmission of language

The intergenerational transmission

of a language reflects its continued use from one generation to the next and is

a criterion with which the vitality of a language can be assessed. In this

report, the intergenerational transmission of mother tongue refers to the fact

children first learn in childhood the same language as their mother in

childhood, meaning both child and mother have the same mother tongue. The rate

of intergenerational transmission is the proportion of children under 5 years

of age who have the same mother tongue as their mother, alone or in combination

with another language.

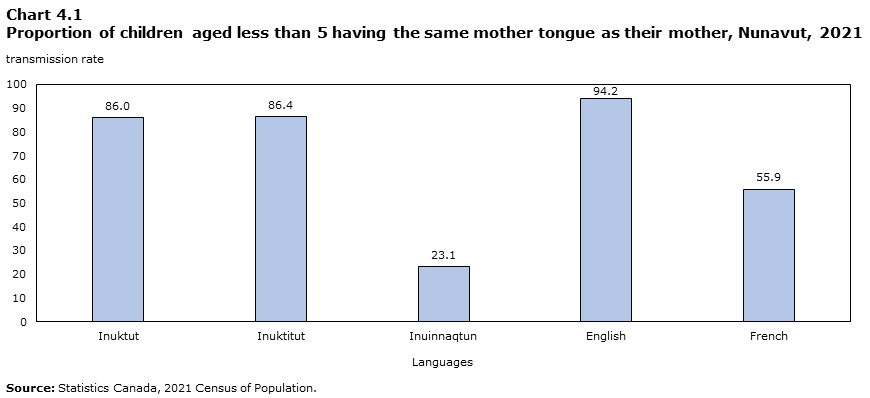

Data table for Chart 4.1

Data table for chart 4.1

Table summary

This table displays the results of Data table for chart 4.1. The information is grouped by Languages (appearing as row headers), Transmission rate (appearing as column headers).

| Languages |

Transmission rate |

| Inuktut |

86.0 |

| Inuktitut |

86.4 |

| Inuinnaqtun |

23.1 |

| English |

94.2 |

| French |

55.9 |

The intergenerational transmission rate for English was

94.2%, which indicates that the vast majority of children born to mothers with

English as their mother tongue also had English as their mother tongue in 2021.

This proportion was 8.4 percentage points lower among children born to mothers

with Inuktitut as their mother tongue—86.4% of those children also had

Inuktitut as their mother tongue. The intergenerational transmission rate was

markedly lower among children born to mothers with Inuinnaqtun as their mother

tongue; nearly one-quarter of these children also had Inuinnaqtun as their

mother tongue (23.1%).

Among children born to mothers with an Inuktut mother tongue

who had a different mother tongue, the vast majority first learned English in

childhood. Several reasons may explain why these children first learned English

as their mother tongue instead of Inuktut. For example, the child’s father

might have English as their mother tongue, or English might be the predominant

home language in the child’s household.

The intergenerational transmission rate of Inuktitut was

88.8% among children born to parents who both had Inuktitut as their mother

tongue. In contrast, the intergenerational transmission rate of English was

higher, at 97.6%, among children born to parents who both had English as their

mother tongue. In exogamous couples where one parent’s mother tongue was

Inuktitut and the other parent’s was English, the intergenerational

transmission rate of Inuktitut was 40.7% while the intergenerational

transmission rate of English was 69.6%, including 20.5% of children who learned

both Inuktitut and English at the same time in their childhood.

4.2 Language retention and transfers

Language retention refers to a situation where a person

predominantly speaks their mother tongue at home. When a mother tongue is no

longer spoken at home, this results in a situation called language transfer,

which is where a person stops using their mother tongue as a home language. A

partial language transfer is a situation where a person still speaks their

mother tongue most often at home, but in combination with another language.

The vast majority of Nunavut residents whose mother tongue

is English predominantly spoke the language at home (95.7%). This was the case

among both Inuit (94.3%) and non-Inuit (98.7%).

The rate of language retention in 2021 was lower among Inuit

who had Inuktitut as their mother tongue, three in four of whom spoke the

language predominantly at home (74.3%). In contrast, about one-quarter of Inuit

with Inuktitut as their mother tongue no longer predominantly spoke Inuktitut

at home, with partial and complete transfer rates of 8.6% and 17.1%,

respectively. Among Nunavut residents with Inuktitut as their mother tongue who

spoke a different language than Inuktut at home, nearly all of them predominantly

spoke English at home (99.6%).

Data table for Chart 4.2

Data table for chart 4.2

Table summary

This table displays the results of Data table for chart 4.2. The information is grouped by Mother tongue (appearing as row headers), Retention, Partial transfer and Complete transfer, calculated using percentage of population units of measure (appearing as column headers).

| Mother tongue |

Retention |

Partial transfer |

Complete transfer |

| percentage of population |

| Total |

|

| Inuktitut |

74.1 |

8.6 |

17.4 |

| Inuinnaqtun |

20.2 |

9.6 |

70.2 |

| English |

95.7 |

2.1 |

2.2 |

| French |

55.7 |

Note ...: not applicable |

44.3 |

| Inuit |

|

| Inuktitut |

74.3 |

8.6 |

17.1 |

| English |

94.3 |

3.0 |

2.8 |

| French |

29.4 |

Note ...: not applicable |

70.6 |

| Non-Inuit |

|

| Inuktitut |

52.5 |

7.1 |

40.4 |

| English |

98.7 |

0.2 |

1.1 |

| French |

57.5 |

Note ...: not applicable |

42.5 |

Among non-Inuit, over two in five people with Inuktitut

(40.4%) or French (42.5%) as a mother tongue were in a situation of complete

language transfer, since they no longer spoke their mother tongue most often at

home.

Among people in Nunavut with Inuinnaqtun as their mother

tongue, one in four continued to speak Inuinnaqtun predominantly at home

(20.2%), while three-quarters (70.2%) reported predominantly speaking English.

The language spoken at home by parents is most likely the

first language that will be learned by children. A parallel can therefore be

drawn between the lower rates of language retention for people whose mother

tongue is Inuktut and the lower rates of intergenerational transmission of

Inuktut languages.

4.3 Aging of speakers

In a context where there is low intergenerational

transmission of a language, fewer people in younger generations may report the

language as a mother tongue.

The distribution of mother tongue speakers by age group in

Nunavut shows that overall, English speakers were a bit younger than Inuktitut

speakers. That being said, a large proportion of speakers of either language

were aged under 15 years (36.2% of English speakers and 32.7% of Inuktitut

speakers).

Data table for Chart 4.3.1

Data table for chart 4.3.1

Table summary

This table displays the results of Data table for chart 4.3.1 Languages, Inuktitut, Inuinnaqtun, English and French, calculated using percentage of population units of measure (appearing as column headers).

|

Languages |

| Inuktitut |

Inuinnaqtun |

English |

French |

| percentage of population |

| 0 to 14 years |

32.7 |

8.0 |

36.2 |

23.6 |

| 15 to 24 years |

16.9 |

6.6 |

16.1 |

6.9 |

| 25 to 39 years |

21.9 |

15.5 |

23.4 |

28.2 |

| 40 to 54 years |

16.1 |

21.1 |

15.3 |

26.1 |

| 55 years and over |

12.4 |

48.8 |

9.0 |

15.2 |

By contrast, almost half of people with Inuinnaqtun as a

mother tongue were aged 55 and over in 2021 (48.8%). This aging of speakers

signifies that a decline in the number of people reporting Inuinnaqtun as a

mother tongue is to be expected in coming years.

Among people who could conduct a conversation in Inuktitut,

the median age of second-language speakers was lower (23 years) than that of

mother tongue speakers (25 years). This difference in the median age was more

pronounced among those who could conduct a conversation in Inuinnaqtun, with a

19-year difference between the median age of mother tongue speakers (54 years)

and second-language speakers (35 years). These results mean that younger people

are learning Inuktitut and Inuinnaqtun as second languages.

Data table for Chart 4.3.2

Data table for chart 4.3.2

Table summary

This table displays the results of Data table for chart 4.3.2. The information is grouped by Languages (appearing as row headers), Mother tongue speakers and Second language speakers, calculated using median age units of measure (appearing as column headers).

| Languages |

Mother tongue speakers |

Second language speakers |

| median age |

| Inuktitut |

25 |

23 |

| Inuinnaqtun |

54 |

35 |

| English |

23 |

29 |

| French |

35 |

37 |

4.4 Internal migration

Internal migration refers to a person moving to Nunavut from

another province or territory in Canada or leaving Nunavut for another province

or territory in Canada.

In recent decades, there has been a high level of internal

in-migration and internal out-migration in Nunavut, especially among non-Inuit.Note However, the

number of people leaving the territory tended to be similar to the number of

people entering the territory, meaning that internal migration generally had

little direct impact on the language situation in Nunavut.Note

The context of the COVID-19 pandemic changed migration flows

in Canada.Note

For instance, several people moved back to their province or territory of

origin. From 2016 to 2021, 2,175 people moved to Nunavut, while 3,265 people

departed Nunavut for another province or territory, resulting in a loss of

about 1,090 residents because of internal migration. Most internal in-migrants

and out-migrants in Nunavut have English as a mother tongue. In fact, the

English-mother-tongue population lost 925 speakers to internal migration from

2016 to 2021. In contrast, net internal migration for Inuktitut, Inuinnaqtun

and French speakers was only slightly negative during that period.

Data table for Chart 4.4

Data table for chart 4.4

Table summary

This table displays the results of Data table for chart 4.4 Net migration, In-migration and Out-migration, calculated using number units of measure (appearing as column headers).

|

Net migration |

In-migration |

Out-migration |

| number |

| Inuktitut |

-55 |

180 |

-235 |

| Inuinnaqtun |

-10 |

10 |

-20 |

| English |

-925 |

1,440 |

-2,365 |

| French |

-30 |

225 |

-255 |

Among English-mother-tongue internal migrants who moved to

Nunavut between 2016 and 2021, 36.4% arrived from the western provinces and

31.8% from Ontario. Among those who left Nunavut during the same period, one-third

moved to the Atlantic provinces (33.3%) and 26.8% moved to Ontario. In

contrast, over half of French-mother-tongue internal migrants who moved to

Nunavut between 2016 and 2021 arrived from Quebec (56.0%), while Quebec was the

destination of 36.0% of French-mother-tongue internal migrants who left Nunavut

during the same period.

Among Inuktitut-mother-tongue internal migrants who moved to

Nunavut between 2016 and 2021, 36.1% arrived from Ontario and 35.0% from the

western provinces. Among those who left Nunavut during the same period, the

main destinations were also Ontario (26.8%) and the western provinces (28.9%).

4.5 International migration

From 2016 to 2021, 180 people moved

to Nunavut from outside Canada and were still in Nunavut in 2021. Among them,

37.4% reported English as their only mother tongue, and 51.0% reported a

language other than English, French or Inuktut as their mother tongue. Very few

international migrants had Inuktut or French as their mother tongue.

About one in four people who moved to Nunavut from abroad

between 2016 and 2021 were actually Canadian-born people returning to the

country (25.2%). The other main country of origin of international migrants who

moved to Nunavut was the Philippines (16.7%).

5. Conclusion

The Government of Nunavut mandated

Statistics Canada to provide an up-to-date and extensive portrait of languages

in Nunavut in this report based on data from the 2021 Census of Population.

Because of challenges related to data collection in the territory in the

context of the COVID-19 pandemic, a certain level of caution is necessary when

comparing the data with those of prior cycles. Emerging trends observed in

2021, such as a decrease in the number of Nunavut residents reporting an

Inuktut mother tongue, and the acceleration of existing trends, such as the

faster decrease in the proportion of Nunavut residents with knowledge of

Inuktut, will have to be confirmed with data collected in the 2026 Census of

Population.

This report showed younger Inuit are less likely than older

Inuit to have Inuktut as their mother tongue, or to report the ability to

conduct a conversation in Inuktut. In addition, the intergenerational

transmission of Inuktut languages remains lower than that of English. English

is spoken at home and used at work by more Nunavut residents than Inuktut, but

Inuktut remains the predominant home language of a large proportion of Inuit.

There are notable differences between Inuktitut and

Inuinnaqtun. Inuinnaqtun has a low number of speakers, few people with

Inuinnaqtun as a mother tongue speak the language at home, and

intergenerational transmission of the language is lower than that of English or

Inuktitut. Half of people with Inuinnaqtun as a mother tongue are aged 55 years

and over, signalling potential challenges for the sustained use of the

language. That being said, younger people are learning Inuinnaqtun, as shown by

the lower median age of second-language speakers.

By contrast, over two-thirds of Nunavut residents can

conduct a conversation in Inuktitut. Inuktitut speakers are young; one-third of

people with Inuktitut as their mother tongue are children under the age of 15

years.

Among Nunavut residents who can conduct a conversation in

Inuktitut, 11.4% learned the language as a second language. This proportion is

37.2% among people who can converse in Inuinnaqtun. Nunavut residents, Inuit

and non-Inuit alike, continue to engage with Inuktut languages. As more recent

data on the official languages of Nunavut are collected, close attention will

have to be paid to the sustained use of Inuktitut and Inuinnaqtun, especially

among younger Inuit.

6 Region and Community profiles

A - Nunavut

Description for Infographic A

This figure contains 5 charts and demographic information pertaining to Nunavut in 2021. The total population of Nunavut was 36,605 people with 85% Inuit and a median age of 25 years. Throughout the charts, the category “Inuktut” includes all mentions of Inuktut, alone or together with another language.

The first chart is a bar graph that shows the knowledge of languages broken down by Inuit identity: 70%, 94% and 4% of the total population could conduct a conversation in Inuktut, English and French respectively. Among Inuit, 81%, 93% and 1% could conduct a conversation in Inuktut, English and French respectively. Among non-Inuit, 9%, 99% and 22% could conduct a conversation in Inuktut, English and French respectively.

The second chart is a bar graph that shows the knowledge of an Inuktut language by age groups. In Nunavut in 2021, 68% of children aged 0 to 4 years, 68% of children aged 5 to 9 years, 72% of children aged 10 to 14 years and 73% of children aged 15 to 24 years could conduct a conversation in Inuktut. Among the people aged 25 to 54 years and 55 years and older, 68% and 74% could conduct a conversation in Inuktut respectively.

The third chart is a pie chart that shows the distribution of mother tongue in Nunavut in 2021: 63% were Inuktut mother tongue speakers, 33% had only English as their mother tongue, 1% had only French as their mother tongue and 3% had other languages as their mother tongue.

The fourth chart is a pie chart that shows the distribution of languages spoken most often at home in Nunavut in 2021: 51% spoke Inuktut most often at home, 47% spoke only English most often at home, 1% spoke only French most often at home and 1% spoke other languages most often at home.

The fifth chart is a pie chart that shows the distribution of languages used most often at work among the Nunavut population that was employed during the Census reference week in 2021: 29% used Inuktut most often at work, 70% used only English most often at work, 0% used only French most often at work and 0% used other languages most often at work.

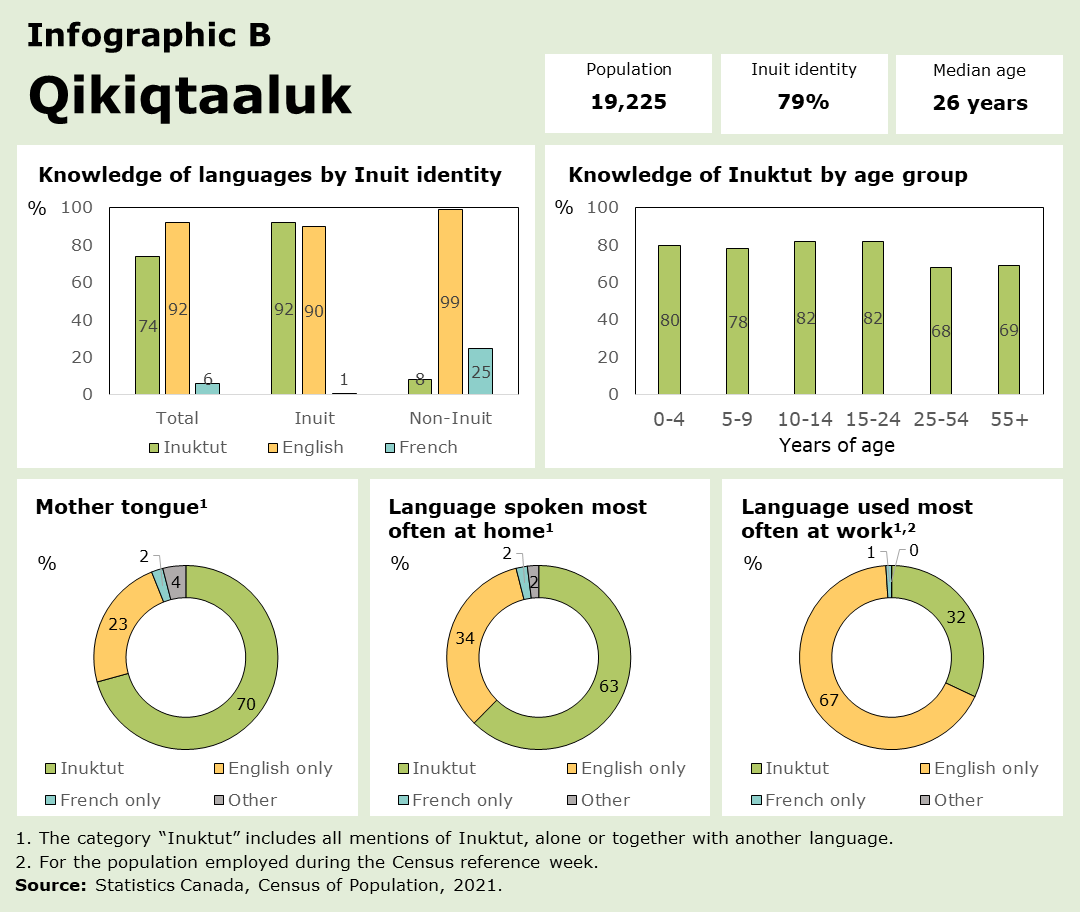

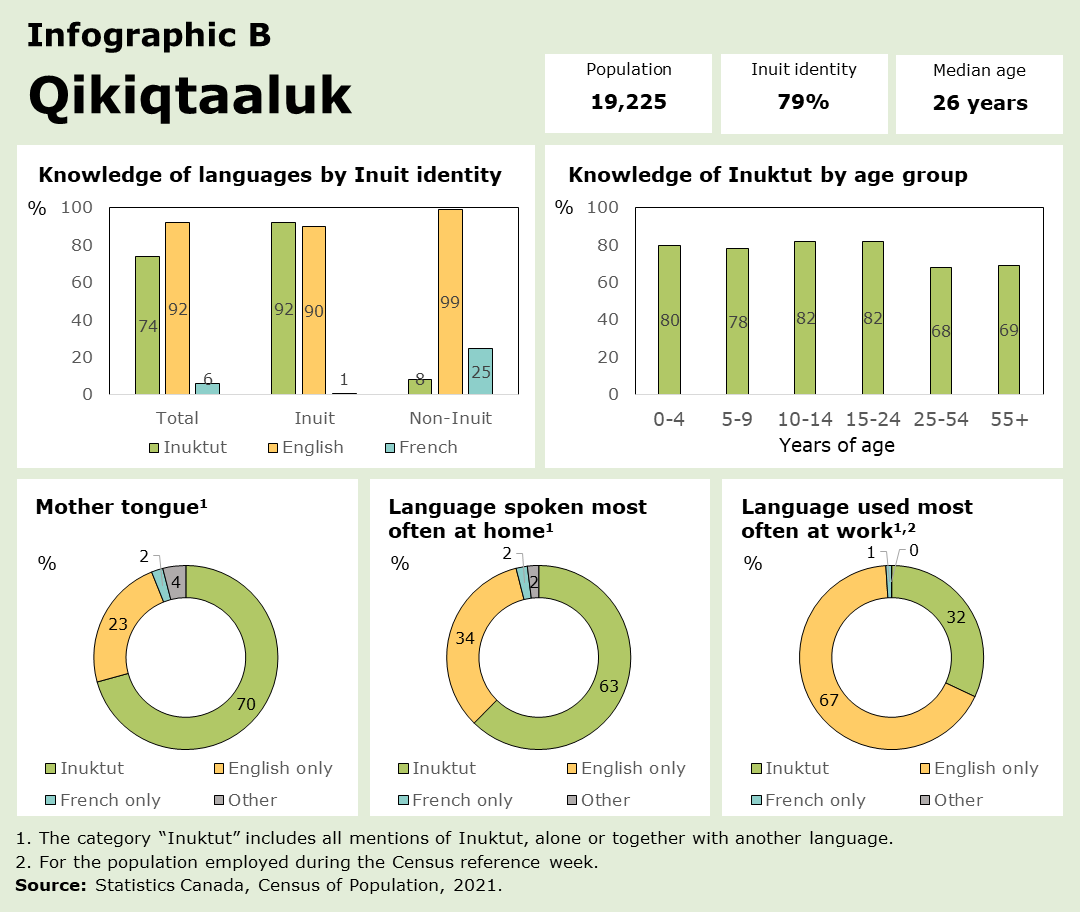

B - Qikiqtaaluk

Description for Infographic B

This figure contains 5 charts and demographic information pertaining to Qikiqtaaluk in 2021. The total population of Qikiqtaaluk was 19,225 people with 79% Inuit and a median age of 26 years. Throughout the charts, the category “Inuktut” includes all mentions of Inuktut, alone or together with another language.

The first chart is a bar graph that shows the knowledge of languages broken down by Inuit identity: 74%, 92% and 6% of the total population could conduct a conversation in Inuktut, English and French respectively. Among Inuit, 92%, 90% and 1% could conduct a conversation in Inuktut, English and French respectively. Among non-Inuit, 8%, 99% and 25% could conduct a conversation in Inuktut, English and French respectively.

The second chart is a bar graph that shows the knowledge of an Inuktut language by age groups. In Qikiqtaaluk in 2021, 80% of children aged 0 to 4 years, 78% of children aged 5 to 9 years, 82% of children aged 10 to 14 years and 82% of children aged 15 to 24 years could conduct a conversation in Inuktut. Among the people aged 25 to 54 years and 55 years and older, 68% and 69% could conduct a conversation in Inuktut respectively.