Juristat Bulletin—Quick Fact

Online child sexual exploitation and abuse: Criminal justice pathways of police-reported incidents in Canada, 2014 to 2020

by Dyna Ibrahim

Online child sexual exploitation and abuse encompasses a broad range of behaviours, including those related to child sexual abuse material, sexting materials (often distributed without consent),Note sextortion,Note grooming and luring, live child sexual abuse streaming and made-to-order content (Public Safety Canada, 2022). Research has documented the short- and long-term negative outcomes of childhood sexual victimization (Beitchman et al., 1991; Browne & Finkelhor ,1986; Hailes et al., 2019; Heidinger, 2022; Olafson, 2011). Similarly, studies have demonstrated the negative long-term effects and potential re-victimization that victims of online child sexual exploitation and abuse experience (Canadian Centre for Child Protection, 2017; Carnes, 2001; Hanson, 2017; Martin, 2015; Ospina et al., 2010; Say et al., 2015; Whittle et al., 2013).

Self-reported victimization data have shown that, overall, the majority of sexual offences never come to the attention of police (Burczycka & Conroy, 2017). Further, when a sexual offence involves a child victim, the incident is even more likely to be underreported for a number of reasons. For example, some children—especially younger children—may be unable to report or seek help, may fear reporting, or may not know how to report or seek help (Finkelhor et al., 2001; Taylor & Gassner, 2010). Additionally, as technology becomes more advanced, so too do the tactics used by offenders to lure and groom children for sexual exploitation and abuse, and with improved anonymity capabilities they can better hide their activities (WeProtect Global Alliance, 2019). This creates challenges for law enforcement to keep up with investigating incidents related to this crime, to identify victims for protection and to bring offenders to justice.

Sexual offences involving children—coupled with the proliferation of smart devices and advancements in technology—make online child sexual exploitation a highly underreported offence in official crime statistics. Still, since national data first became available in 2014, the number of police-reported incidents of online child sexual exploitation and abuse has increased, with the rate nearly tripling by 2020 (Ibrahim, 2022). Even though this crime is underreported and underestimated in police-reported data, this upward trend and the continuing advancements in technology underscore the importance of continued research in this area to help facilitate informed decision making and prevention efforts.

National-level statistics on police-reported incidents of online child sexual exploitation and abuse were presented in a preceding publication (Ibrahim, 2022). In addition to the previously published information on prevalence, trends, and characteristics of incidents, victims, accused persons, and court cases and charges, there are other questions about this type of crime that can be addressed using data collected from police and court records. These questions include, among others:

- What happens after an incident is reported to police?

- How do online child sexual exploitation and abuse incidents that were reported to police progress through the criminal justice system?

- What happens to accused persons who have been identified in relation to these incidents in terms of the types of charges laid and the outcomes of these charges?

- More broadly, how do the pathways of online child sexual exploitation and abuse incidents in the criminal justice system compare with other types of crime?

This article aims to answer these important questions.

Using data from the Incident-based Uniform Crime Reporting Survey and the Integrated Criminal Court Survey, the current article examines criminal justice outcomes of online child sexual exploitation and abuse incidents that were reported to police between 2014 and 2020, and the pathways of these incidents through the justice system, including court case outcomes. Understanding the pathways of these cases through the criminal justice system will shed light on the similarities between online child sexual exploitation and abuse compared with other forms of crime, and on the potential challenges and constraints related to the prosecution of those accused of the former that may be unique to or exacerbated by the online nature of these crimes.

It should be noted that, while the current article makes many references to the preceding Statistics Canada article on online child sexual exploitation and abuse (Ibrahim, 2022), the analyses presented herein aim to answer a different set of questions—specifically, those listed above. Additionally, while the preceding article used the same data sources individually, the current article is based on a record linkage between the two files. Therefore, any comparisons between the two articles should be made with caution.

When examining underreporting, attrition, and justice outcomes of sexual crimes, studies have often used physical assault as a benchmark for comparison (Felson & Paré, 2005; Rotenberg, 2017; Thompson et al., 2007). Additionally, while certain violations defined within the Criminal Code fall under the scope of online child sexual exploitation and abuse (Text box 1), the absence of a standard or specific Criminal Code offence for online child sexual exploitation and abuse, and a reliance on survey-specific fields to define it, presents challenges in comparing court outcomes of these incidents to different types of sexual offences—which are explicitly defined in the Criminal Code. Further, due to data constraints, comparisons to in-person incidents that take place in offline spaces (i.e., non-cybercrime incidents, also referred to in this article as ‘contact offences’) would be limited to data beginning in 2018— reducing the number of incidents of online child sexual exploitation and abuse that could be analyzed for court outcomes.Note For these reasons, in the current article, physical assault is used as a benchmark for comparisons throughout.Note

It should be noted that, while comparisons throughout this article are to total physical assaults, the findings and any differences to online child sexual exploitation and abuse incidents remained even when the analyses were limited to physical assaults involving child victims below the age of 18 years. Therefore, comparisons of online child sexual exploitation and abuse incidents to child physical assaults specifically are not discussed. However, data for child physical assaults, which represented approximately 13% of the reported physical assault incidents, are presented in the charts for reference. Additionally, using sexual assaults as proxy for contact sexual offences against children, further comparisons of online child sexual exploitation and abuse outcomes are explored in Text box 3.

This article was produced with funding support from Public Safety Canada.

Start of text box 1

Text box 1

Defining and measuring online child sexual exploitation and abuse using police-reported data

Beginning in 2014,Note the Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR) Survey has collected information related to online crime through the use of a cybercrime flag. An incident is flagged as a cybercrime when the crime targets information and communication technology (ICT), or when ICT was used to commit the offence.

ICT includes, but is not limited to, the Internet, computers, servers, digital technology, digital telecommunications devices, phones and networks. Crimes committed over text and through messages using social media platforms are also considered cybercrime activity.

Police services can report up to four violations for each incident reported in the UCR. The UCR classifies incidents according to the most serious violation occurring in the incident (generally the offence which carries the longest maximum sentence under the Criminal Code), with violations against the persons always classified as more serious than other violations. In order to maintain consistency in measuring the cyber aspect of crime, analyses of cybercrime data are based on the most serious violation in the incident that was most likely to have involved ICT, referred to as the cybercrime violation.

Incidents involving child pornography where an actual child victim was not identified are reported to the UCR with the most serious violation being “child pornography.” When an actual child victim is identified, the incident is reported to the UCR with the most serious violation as sexual assault, sexual exploitation, or other sexual violations against children, and child pornography may be reported as a secondary violation. Because of this difference, and to account for the complexities associated with investigating incidents of child pornography, analyses in this article are presented in terms of two categories of offences: online sexual offences against children and online child pornography.

Online sexual offences against children include:

- Sexual violations against children involve the following Criminal Code offences: sexual interference, invitation to sexual touching, sexual exploitation, parent or guardian procuring sexual activity, householder permitting prohibited sexual activity, luring a child, agreement or arrangement (sexual offences against a child) and bestiality (in presence of, or incites, a child),Note and

- Other sexual offences are Criminal Code sexual offences that are not specific to children but where a victim was identified as being younger than 18. These include: non-consensual distribution of intimate images, sexual assault (levels 1, 2 and 3), sexual exploitation of person with disability, bestiality (commits, compels another person), voyeurism, incest and other sexual crimes.

Online child pornography includes incidents excluded from the category of sexual offences against children and includes offences under section 163.1 of the Criminal Code which makes it illegal to make, distribute, possess or access child pornography.

Keeping with the above noted definitions and structure of the UCR, the current article defines online child sexual exploitation and abuse as police-reported cybercrime incidents involving Criminal Code child-specific sexual offences, including child pornography, and other Criminal Code sexual offences where a victim was identified as being a person younger than 18.

This definition is used for identifying police-reported incidents. Subsequent analyses on court outcomes and pathways are based on court records that were successfully linked to these police incidents. For additional information, see Text box 2.

In this article, the terms “online” and “cyber” are used interchangeably and, in the context of police-reported incidents, they all refer to situations where ICT was flagged. Further, “children and youth” refer to people aged 17 and younger.Note

When a police-reported incident has been flagged as cybercrime, any of the violations in the incident may have involved the use of technology. For analytical purposes, a specific violation within each cybercrime incident is identified as the cyber-related violation. This violation is the most serious in the incident which was most likely to have involved ICT.

End of text box 1

Retention or attrition of online child sexual exploitation and abuse cases in the criminal justice system

It has been well established that sexual offences involving child victims do not often come to the attention of police for numerous reasons such as children not knowing that they are being victimized, being afraid to report or knowing how to report or seek help (Finkelhor et al., 2001; Taylor & Gassner, 2010). Further, when such crimes are perpetrated or facilitated online, this presents additional barriers for police to identify and investigate, and for victims to be located or perpetrators to be identified and prosecuted. For example, with better technology comes advanced anonymity capabilities which may allow offenders to better hide their criminal activities (WeProtect Global Alliance, 2019). Thus, online child sexual exploitation and abuse, which encompasses a wide range of actions and behaviours, is highly susceptible to underreporting and underestimation.

Through several initiatives, Canada continues in its efforts to combat online child sexual exploitation and abuse. This includes work under Canada’s National Strategy for the Protection of Children from Sexual Exploitation on the Internet. For example, with support from Public Safety Canada, the Canadian Centre for Child Protection (C3P) manages Project Arachnid, an automated web crawler that detects and processes tens of thousands of images per second and sends take-down notices to online service providers to remove child sexual abuse material globally. Additionally, C3P is also responsible for Cybertip.ca, an online platform that facilitates the reporting of suspected online child sexual exploitation by Canadians. Additionally, Public Safety Canada, in collaboration with the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, is participating in collaborative working groups with international partners to minimize barriers for law enforcement to better tackle online child sexual exploitation and abuse.

Since 2014, when nationally representative cybercrime data first became available, the number of incidents constituting police-reported online child sexual exploitation and abuse has generally been on an upward trend. (Ibrahim, 2022). Understanding where retention or attrition occurs for these incidents, decisions and outcomes related to incidents that are retained, and at what point the gap widens relative to other crimes will help in identifying areas of focus for law practitioners, and program and policy makers. It will also aid in making programming and services, and the justice system as a whole, more responsive to incidents involving online child sexual exploitation and abuse and the unique needs of those who experience it.

In the context of this article, case retention is defined as the proportion of police-reported incidents that continue through the justice system, from an incident reported to police, to a court case with a reportable outcome. Conversely, attrition refers to points in the criminal justice pathways at which a case may “drop out” of the system. Here, it is the opposite of retention. In linked police and court data, there are several points at which case retention or attrition could be measured (Figure 1). First, examining clearance (where at least one accused had been identified in connection with the incident) and charge rates will indicate the proportion of incidents where the incident was considered solved, and subsequently whether charges were laid or recommended.Note Then, of those incidents where an accused person was identified and charged (or charges were recommended), the proportion that went to court is another case retention indicator.Note

Figure 1 start

Figure 1. From police report to sentencing: Criminal justice pathways, and case retention or attrition.

This figure shows retention or attrition of police-reported incidents through the criminal justice system, and court outcomes of those incidents that go to court. With a reported incident the process of retention or attrition begins. The reported incident is either not cleared or cleared. A cleared incident can result in no charges or charges laid or recommended by police. Charges laid or recommended by police can result in not going to court or going to court. Going to court leads to outcomes, which include: guilty; stayed, withdrawn, dismissed, or discharged; acquitted; or other. Other decisions include final decisions of found not criminally responsible and waived out of province or territory. This category also includes any order where a guilty decision was not recorded, the court's acceptance of a special plea, cases which raise Charter arguments and cases where the accused was found unfit to stand trial. Being found guilty may result in probation, custody or other, including conditional sentences, fines, community service, and other sentencing decisions.

Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics, Uniform Crime Reporting Survey and Integrated Criminal Court Survey.

Figure 1 end

Attrition in police-reported online child sexual exploitation and abuse incidents highest at the clearance stage

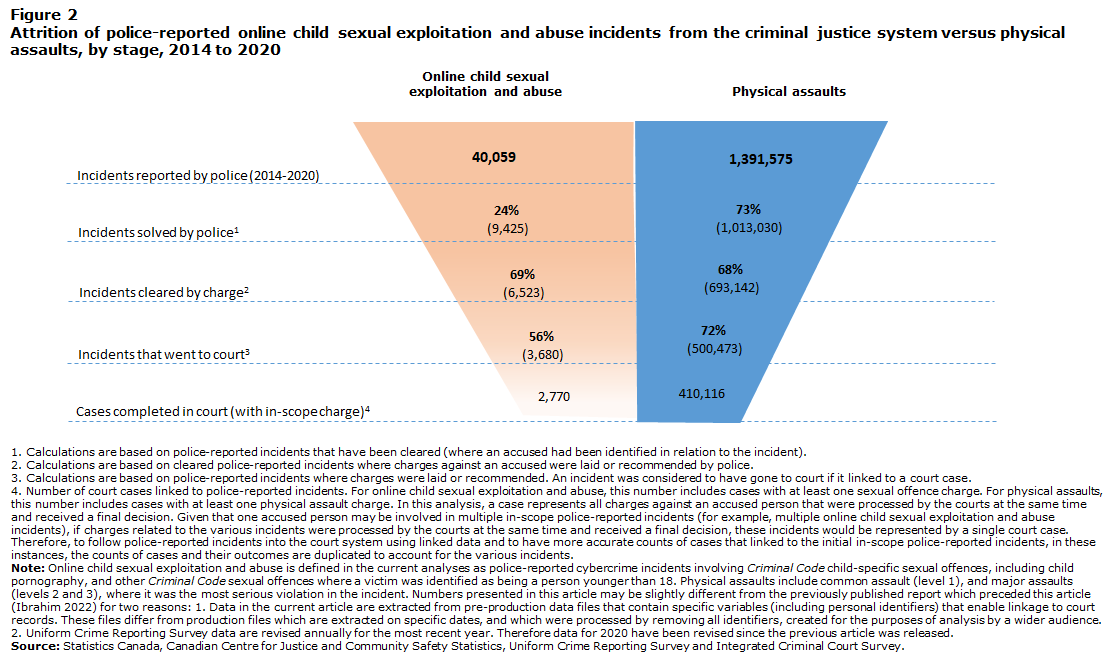

As mentioned, incidents of online child sexual exploitation and abuse are likely highly underreported, meaning, they don’t even enter the formal justice system. Further, incidents that do come to the attention of police continue to gradually drop out of the justice system. Figure 2 below illustrates the decline in the number of incidents that are retained within the system.

Figure 2 start

Data table for Figure 2

| Attrition stage | Online child sexual exploitation and abuse | Physical assaults | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| percent | number | percent | number | |

| Incidents reported by police (2014-2020) | Note ...: not applicable | 40,059 | Note ...: not applicable | 1,391,575 |

| Incidents solved by policeFigure 2 Note 1 | 24 | 9,425 | 73 | 1,013,030 |

| Incidents cleared by chargeFigure 2 Note 2 | 69 | 6,523 | 68 | 693,142 |

| Incidents that went to courtFigure 2 Note 3 | 56 | 3,680 | 72 | 500,473 |

| Cases completed in court (with in-scope charge)Figure 2 Note 4 | Note ...: not applicable | 2,770 | Note ...: not applicable | 410,116 |

... not applicable

Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics, Uniform Crime Reporting Survey and Integrated Criminal Court Survey. |

||||

Figure 2 end

Police-reported data indicate that from the time national level cybercrime data first became available in 2014, until 2020, there were 40,059 incidents of online child sexual exploitation and abuse.Note This number represents both online child sexual offences against children where the victim was identified by police, and child pornography incidents, where the child victim had not been identified. As previously reported, incidents involving an identified victim were much more likely to be cleared compared with child pornography incidents (Ibrahim, 2022). An incident is considered to be cleared, or solved, if police were able to identify an accused person in relation to the incident and had enough information to lay or recommend a charge against them.

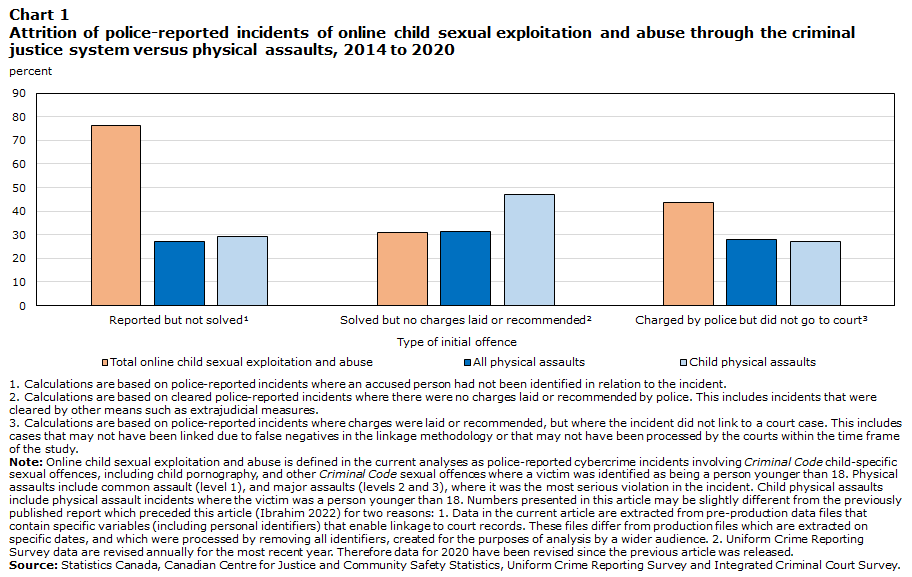

Among the stages included in the current article (clearance, charge, court), attrition for online child sexual exploitation and abuse incidents was highest at the clearance stage, with 24% of incidents being solved by police services (Figure 2). This means, for 76% of incidents, an accused person was not identified and therefore no charges could be laid or brought to court (Chart 1). This was also the stage where the biggest difference in attrition rates between online child sexual exploitation and abuse and physical assaults was observed (27% for physical assaults). This large drop-off is likely due to significant challenges police encounter in trying to solve a crime that was perpetrated online where accused persons can more easily evade detection. The next highest level of attrition for reported online child sexual exploitation and abuse is at the court stage: in more than four in ten (44%) incidents where there was an accused identified and charges were laid or recommended, the case did not proceed to court.Note

Chart 1 start

Data table for Chart 1

| Type of initial offence | Reported but not solvedData table for Chart 1 Note 1 | Solved but no charges laid or recommendedData table for Chart 1 Note 2 | Charged by police but did not go to courtData table for Chart 1 Note 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| percent | |||

| Total online child sexual exploitation and abuse | 76 | 31 | 44 |

| All physical assaults | 27 | 32 | 28 |

| Child physical assaults | 29 | 47 | 27 |

Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics, Uniform Crime Reporting Survey and Integrated Criminal Court Survey. |

|||

Chart 1 end

Making or distributing child pornography incidents most likely to drop out before going to court

Examining linked data from an attrition standpoint reveals some notable differences among the different types of police-reported online child sexual exploitation and abuse.Note

Compared with other forms of online child sexual exploitation and abuse, a much lower share of making or distributing child pornography incidents went to court. Over half (54%) of police-reported incidents of making or distributing child pornography did not go to court, resulting in this offence having the highest attrition rate at this stage (Chart 2).

Chart 2 start

Data table for Chart 2

| Type of initial offence | Reported but not solvedData table for Chart 2 Note 1 | Solved but no charges laid or recommendedData table for Chart 2 Note 2 | Charged by police but did not go to courtData table for Chart 2 Note 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| percent | |||

| Luring a child | 61 | 25 | 42 |

| Non-consensual distribution of intimate images | 52 | 71 | 33 |

| Invitation to sexual touching |

14 | 5 | 42 |

| Possessing or accessing child pornographyData table for Chart 2 Note 4 |

74 | 35 | 40 |

| Making or distributing child pornographyData table for Chart 2 Note 4 |

89 | 36 | 54 |

Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics, Uniform Crime Reporting Survey and Integrated Criminal Court Survey. |

|||

Chart 2 end

While, overall, attrition in online child sexual exploitation and abuse incidents was highest at the clearance stage, this was not the case for non-consensual distribution of intimate images, where attrition was in fact highest at the charge level, with a large majority (71%) of incidents not resulting in charges after an accused was identified. This is likely in large part attributable to the fact that this type of offence typically involved a youth accused (between the ages of 12 and 17 years) (Ibrahim, 2022). The Youth Criminal Justice Act dictates that youth accused should be dealt with through extrajudicial measures that divert them from the formal court system.

Another notable difference was for the offence of invitation to sexual touching which had the lowest attrition rate at the charge stage, with a 5% dropout rate. Relative to the other offence categories, this offence type also had the highest clearance rate (Ibrahim, 2022), yielding the lowest attrition rate at the clearance stage (14%) among all offence categories of online child sexual exploitation and abuse.Note These findings may be related to this type of offence being likely to involve multiple violations in the incident which, as previously reported, often results in a higher clearance rate and charges (Ibrahim, 2022).

Start of text box 2

Text box 2

Pathway of charges from police-reported incident to court

There is no definition for the offence of online child sexual exploitation and abuse in the Criminal Code. To examine justice outcomes of online child sexual exploitation and abuse in Canada, police-reported incidents from the Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR) Survey are defined based on a cybercrime flag (Text box 1). Then, these data are linked to court records from the Integrated Criminal Court Survey (ICCS) to explore their outcomes within the courts system. It is important to note that, in this article, proportions of cases or charges going to court are limited by the ability to successfully link a record from police-reported incidents to administrative court data. Therefore, some records may be missing from the linked file. This, however, is a limitation for all offences included in the study, and comparative offence groups.Note

It is also worth noting that there are many differences between the UCR Survey and the ICCS. One notable difference between the two is in how records are counted. For example, multiple police incidents can lead to a single court case, and one accused person in police records can be involved in multiple court cases. Similarly, charges laid or recommended by police may change once in court, and additional charges may be added once a court case has begun. Therefore, the relationship between the two data sources is not one-to-one. Given that there is no specific definition for the crime of online child sexual exploitation and abuse in the Criminal Code, this text box presents a brief analysis of the charges in police incidents and how court cases related to the online child sexual exploitation and abuse incidents are identified.

Of note, to simplify the analysis of charge information as they progress from police to court using the UCR Survey and ICCS, calculations in this text box are limited to single-accused incidents which represent 93% of all cleared online child sexual exploitation and abuse incidents.

About two-thirds (65%) of police-reported online child sexual exploitation and abuse incidents that were cleared by charge had information about the types of charges laid or recommended by police.Note Note Multiple charges were laid or recommended by police in the majority of these incidents: 28% involved two charges, 24% involved three charges, and 25% involved four or more charges. Single charge incidents represented 24% of incidents.

Overall, the large majority (89%) of online child sexual exploitation and abuse incidents with available police charge information included a charge for a sexual offence that matched the initial violation identified as the online child sexual exploitation and abuse offence (Text box 1).Note Note The remaining 410 incidents did not include a charge that matched the initial cybercrime violation. In these incidents, charges were most often laid or recommended for a different type of sexual offence.

Cases processed in court can involve multiple charges. Linked court data indicate that there were 31,557 charges processed in court in relation to the single-accused online child sexual exploitation and abuse incidents reported by police.Note Seven out of ten (70%) of the charges processed in court matched one of the charges laid or recommended by police.Note Another 23% of charges were for a sexual offence different than those laid or recommended by police. These charges could be for secondary violations which were not reported in the survey.Note Similarly, the vast majority (91%) of charges processed in court for incidents that started off as physical assaults—and where such charges were laid or recommended by police-- were the same as those seen in court.

As stated earlier, online child sexual exploitation and abuse is not explicitly defined in the Criminal Code and, as demonstrated above, court charges related to online child sexual exploitation and abuse incidents often remained the same as the charge laid or recommended by police, or changed to a charge for a different sexual offence. Moreover, sexual offences are generally slightly less likely to lead to a conviction, compared with physical assaults (Rotenberg, 2017). For these reasons, and due to a relatively small sample size, analysis of court outcomes in this article are based on all cases with at least one charge for a sexual offence violation. This represents 84% of all court cases linked to the online child sexual exploitation and abuse incidents reported by police. Additionally, throughout the article, conviction rates are presented for cases where there is a finding of guilt for any sexual offence charge in the case.

End of text box 2

Pathways and outcomes of online child sexual exploitation and abuse incidents that are retained in the criminal justice system

Relatively few online child sexual exploitation and abuse incidents compared with physical assaults are solved or make it to court, but conviction rates are much higher

Previous research found that sexual assaults involving child victims went to court less often than adult sexual assaults, and sexual assaults in general were more prone to dropping out of the justice system between police and court than physical assaults (Rotenberg, 2017). Consistent with this finding, and as shown above, the retention of police-reported online child sexual exploitation and abuse incidents from police to court was generally lower compared with physical assaults. Nevertheless, as demonstrated below, linked online child sexual exploitation and abuse cases that ended up in court had a much higher conviction rate for any charge in the case, compared with linked physical assault cases.Note

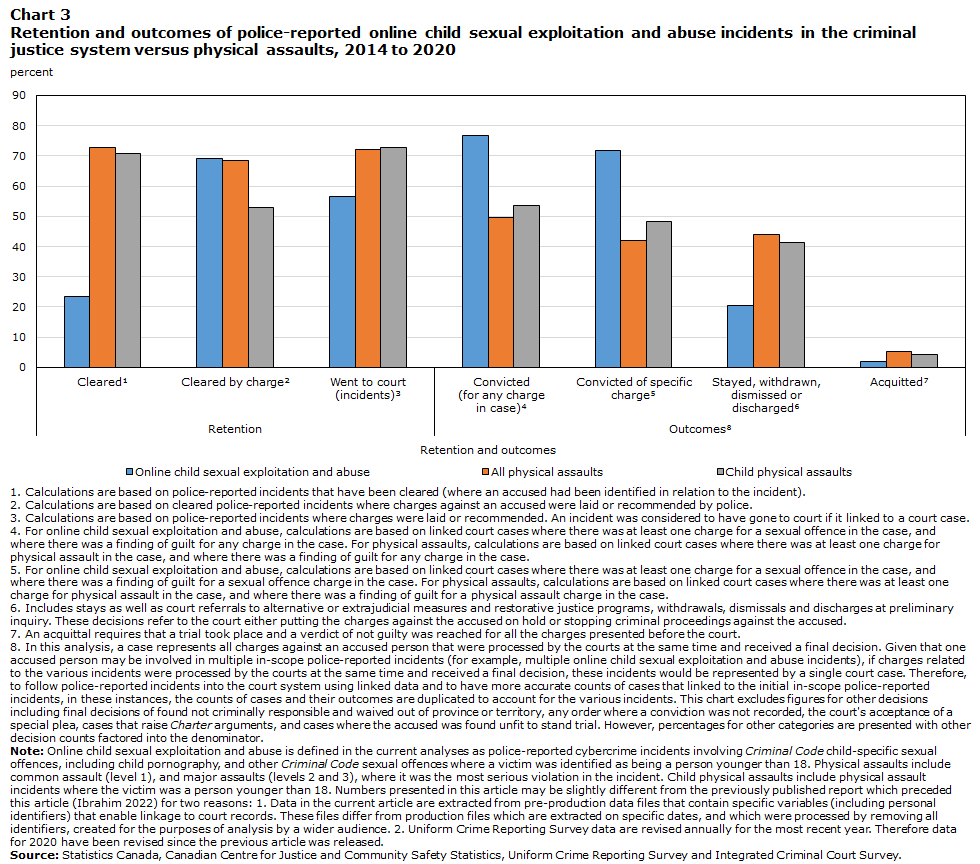

As indicated, of the 40,059 police-reported incidents of online child sexual exploitation and abuse reported between 2014 and 2020, about one-quarter (24%) were cleared, meaning an accused person was identified in relation to the incident (Table 1).Note In comparison, a much larger proportion of physical assaults reported over the same time were cleared (73%) (Chart 3). This may be expected as a physical assault, by its very nature, can generally be pinpointed to a specific location, making it easier to locate an accused person, which is in direct contrast to trying to locate an accused person who committed an online offence.

Chart 3 start

Data table for Chart 3

| Retention and outcomes | Online child sexual exploitation and abuse | All physical assaults | Child physical assaults | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| percent | ||||

| Retention | ClearedData table for Chart 3 Note 1 | 24 | 73 | 71 |

| Cleared by chargeData table for Chart 3 Note 2 | 69 | 68 | 53 | |

| Went to court (incidents)Data table for Chart 3 Note 3 | 56 | 72 | 73 | |

| OutcomesData table for Chart 3 Note 8 | Convicted (for any charge in case)Data table for Chart 3 Note 4 |

77 | 50 | 54 |

| Convicted of specific chargeData table for Chart 3 Note 5 | 72 | 42 | 48 | |

| Stayed, withdrawn, dismissed or dischargedData table for Chart 3 Note 6 | 20 | 44 | 41 | |

| AcquittedData table for Chart 3 Note 7 | 2 | 5 | 4 | |

Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics, Uniform Crime Reporting Survey and Integrated Criminal Court Survey. |

||||

Chart 3 end

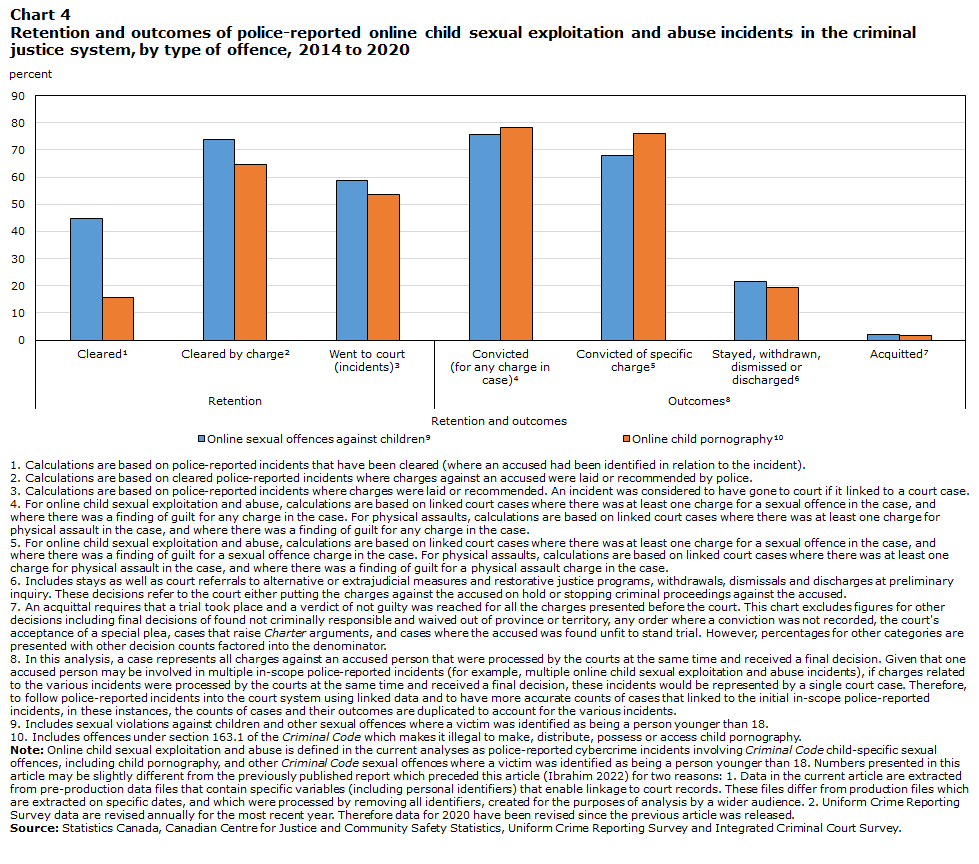

Overall, once an accused person was identified in connection with an online child sexual exploitation and abuse incident, it was very likely for the incident to result in charges being laid or recommended. There were charges laid or recommended in nearly seven in ten (69%) incidents that were cleared. This charge rate was similar to physical assaults where 68% of cleared incidents resulted in charges being laid or recommended. Charges were more common for online sexual offences against children than for online child pornography.

Just over half (56%) of online child sexual exploitation and abuse incidents that led to charges proceeded to court; these consisted of slightly more online sexual offences against children than online child pornography (59% and 53%, respectively).Note Note The overall proportion was much lower than the 72% of charged physical assault incidents that went to court.

While the trends seen in this article thus far yielded a lower overall retention rate for online child sexual exploitation and abuse incidents, relative to physical assaults, court outcomes reveal a different trajectory for these crimes. More specifically, of the linked online child sexual exploitation and abuse cases in court where there was at least one charge for a sexual offence, 77% led to a conviction (for any offence in the case).Note Overall, 72% of cases resulted in a guilty finding for a sexual offence charge. The remaining 5% of the linked cases led to a guilty finding for a non-sexual offence. Moreover, 20% of linked cases resulted in a stay, withdrawal, dismissal or discharge as the most serious decision in the case.Note This finding could also be considered a form of attrition, as these decisions all refer to the court stopping criminal proceedings against the accused. An acquittal was rare in linked online child sexual exploitation and abuse cases (2%).

Of note, overall conviction rates when considering all charges in the case were similar for police-reported incidents of online sexual offences against children (where a child victim had been identified) and online child pornography (where the child victim had not been identified) (Chart 4). However, linked online child pornography cases more often led to a conviction for a sexual offence charge specifically (76%), compared with online sexual offences against children (68%).

Chart 4 start

Data table for Chart 4

| Retention and outcomes | Online sexual offences against childrenData table for Chart 4 Note 9 | Online child pornographyData table for Chart 4 Note 10 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| percent | |||

| Retention | ClearedData table for Chart 4 Note 1 | 45 | 16 |

| Cleared by chargeData table for Chart 4 Note 2 | 74 | 64 | |

| Went to court (incidents)Data table for Chart 4 Note 3 | 59 | 53 | |

| OutcomesData table for Chart 4 Note 8 | Convicted (for any charge in case)Data table for Chart 4 Note 4 |

76 | 78 |

| Convicted of specific chargeData table for Chart 4 Note 5 | 68 | 76 | |

| Stayed, withdrawn, dismissed or dischargedData table for Chart 4 Note 6 | 21 | 19 | |

| AcquittedData table for Chart 4 Note 7 | 2 | 2 | |

Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics, Uniform Crime Reporting Survey and Integrated Criminal Court Survey. |

|||

Chart 4 end

In contrast, while a larger share of physical assault incidents proceeded to court, 50% of cases with at least one assault charge processed in court ended in a finding of guilt for a charge in the case, regardless of the type of charge. The proportion that resulted in a guilty finding for at least one assault charge (42%) was almost half of the proportion of online child sexual exploitation and abuse cases that resulted in a guilty finding for a sexual offence charge.Note Instead, a finding of stayed, withdrawn, dismissed or discharged was the most serious decision for any charge in the case in more than four in ten (44%) linked physical assault cases. In other words, although online child sexual exploitation and abuse incidents less often went to court, compared with physical assaults, when they did, they more often led to a conviction.

Of online child sexual exploitation and abuse cases with a guilty finding, almost nine in ten led to a custodial sentence

In total, there were 2,770 court cases linked to an online child sexual exploitation and abuse incident, where there was at least one charge for a sexual offence. The large majority (84%) were processed in adult courts, while cases completed in youth courts accounted for the remaining 16%.Note

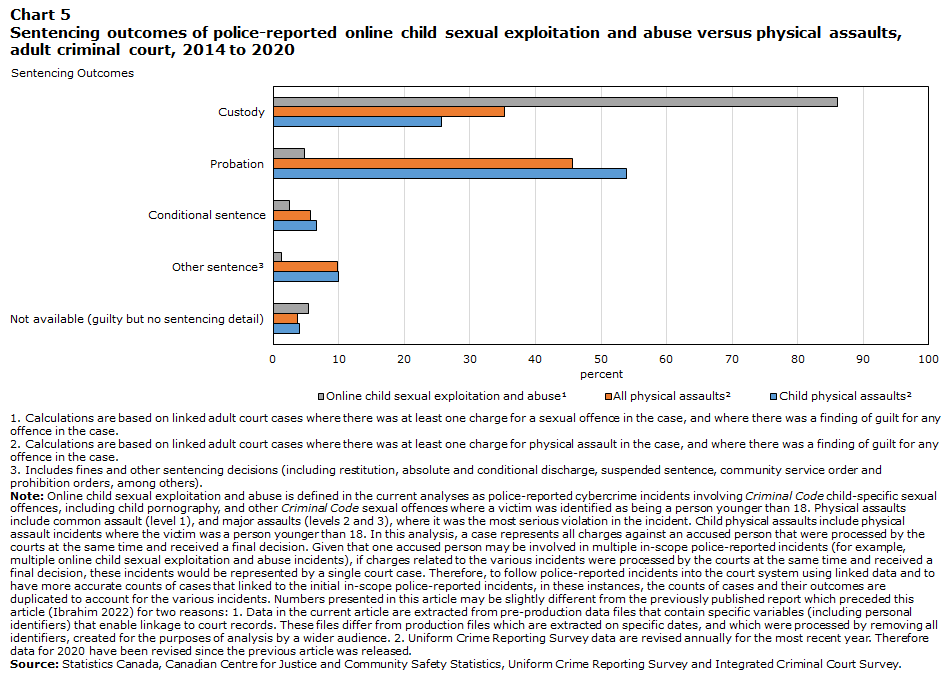

In adult courts, linked online child sexual exploitation and abuse cases with a guilty finding for any charge in the case most often led to custody (86%) (Chart 5).Note In comparison, a much lower proportion of linked cases of physical assaults with a guilty finding in adult courts resulted in a custody sentence (35%).

An adult custody sentence was slightly more common for linked online child pornography than online sexual offences against children (90% compared with 83%, respectively).

Chart 5 start

Data table for Chart 5

| Sentencing Outcomes | Online child sexual exploitation and abuseData table for Chart 5 Note 1 | All physical assaultsData table for Chart 5 Note 2 | Child physical assaultsData table for Chart 5 Note 2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| percent | |||

| Custody | 86 | 35 | 26 |

| Probation | 5 | 46 | 54 |

| Conditional sentence | 3 | 6 | 7 |

| Other sentenceData table for Chart 5 Note 3 | 1 | 10 | 10 |

| Not available (guilty but no sentencing detail) | 5 | 4 | 4 |

Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics, Uniform Crime Reporting Survey and Integrated Criminal Court Survey. |

|||

Chart 5 end

Some of these differences in custodial sentences for guilty cases may be partly attributable to mandatory minimum penalties which are imposed for the most serious offences under the Criminal Code. In 2005, mandatory minimum penalties were introduced for sexual violations against children and child pornography. There was a large increase in custody sentences for sexual violations against children and child pornography cases with guilty decisions following the introduction of mandatory minimum sentences in 2005 (Allen 2017).Note

Start of text box 3

Text box 3

Sexual offences against children: Online versus a proxy for contact offences

Prior to 2018, all cybercrime data collected through the Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR) Survey were kept in a separate database from other data collected through the UCR. Due to differences in the data processing methodologies between these databases, analysis identifying cybercrime incidents within all incidents was not feasible. As this change in methodology is related to data processing (particularly, when the different data sets were created), the cybercrime and all crime data sets are incomparable. However, this change does not impact the way data are collected. Therefore, while comparisons between cybercrime and non-cybercrime incidents cannot be made prior to 2018 due to these processing differences, the changes do not impact total year-to-year counts for cybercrime data alone. As such, the current article pools UCR data from 2014 to 2020. Beginning in 2018, cybercrime data were merged with all other UCR incident data to allow for comparisons between cybercrime data and non-cyber crime. This type of comparison can only be done using data beginning in 2018 (see Text box 3 in Ibrahim, 2022).

The current article presents analyses of online child sexual exploitation and abuse based on incidents where a specific sexual offence was identified in police-reported data as the cybercrime violation (Text box 1). Given that the UCR Survey defines the cybercrime violation based on the most serious violation that is likely to be a cybercrime, there were no sexual assault incidents that were identified as the cybercrime violation. As such, in this text box, sexual assaults are used as proxy for ‘contact’ (or in-person) sexual offences against children, allowing for comparisons of data collected over the same period of 2014 to 2020. Note Since there are some differences between online sexual offences against children, and online child pornography, comparisons to online child sexual exploitation and abuse will be limited to incidents where a victim was identified (or sexual offences against children—hereafter referred to in this text box as “online offences”).

Police services can report up to four violations for each incident. Further, in a small minority of incidents, the cybercrime violation is not the most serious violation in the incident (Ibrahim 2022). Therefore, it is possible that a small share of incidents overlaps between the online and contact incidents included in this analysis.

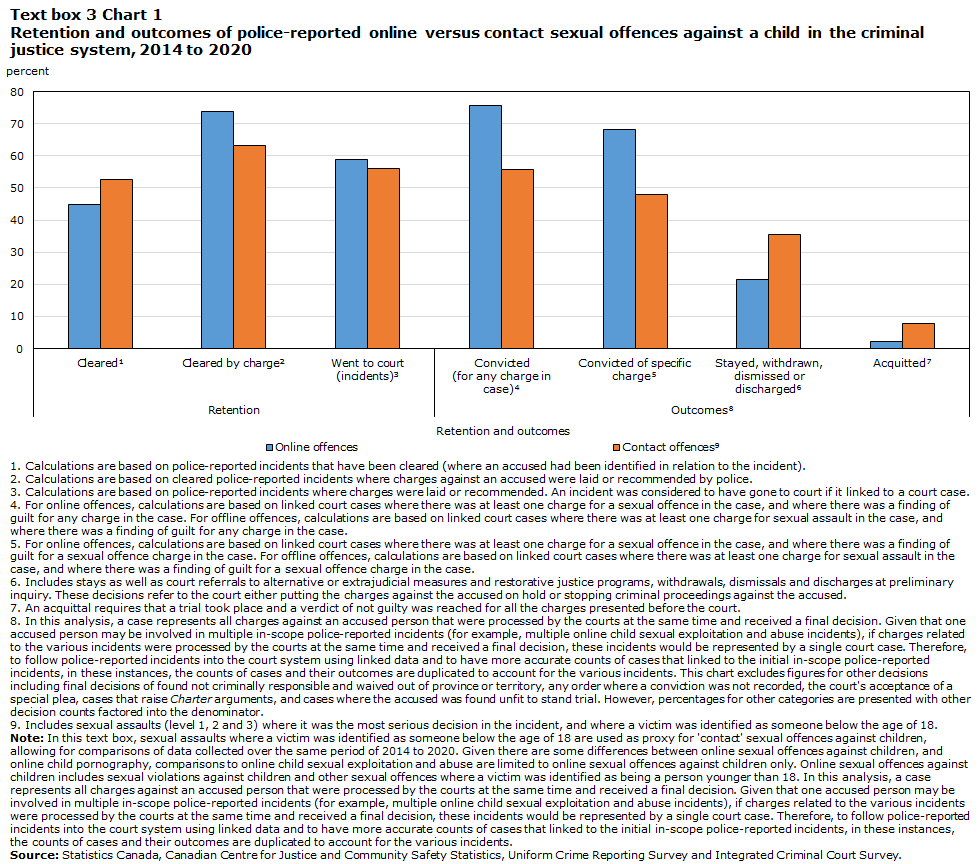

Online offences less commonly solved, but when they are, more often lead to charges, a conviction and adult custody

Between 2014 and 2020, police reported 61,537 incidents of sexual assaults against children (referred to hereafter in this text box as “contact offences”). More than half (53%) of the reported contact offences were solved compared to 45% of online offences, while fewer contact incidents resulted in charges being laid or recommended (63% compared with 74%).

Retention rates from police to court were almost the same for online and contact incidents (59% and 56%, respectively). Like the differences seen with physical assaults, online incidents more often led to a finding of guilt once in court, compared with cases linked to contact offences (76% versus 56%). A conviction for a sexual offence was also higher for cases linked to online (68%) than contact offences (48%) (Text box 3 Chart 1). The presence of online footprints or records that present as physical evidence that may aid in proving guilt may contribute to these differences, whereas physical evidence for contact sexual assaults may be more difficult to produce.

Textbox Chart 1 start

Data table for Textbox Chart 1

| Retention and outcomes | Online offences | Contact offencesData table for Text box 3 Chart 1 Note 9 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| percent | |||

| Retention | ClearedData table for Text box 3 Chart 1 Note 1 | 45 | 53 |

| Cleared by chargeData table for Text box 3 Chart 1 Note 2 | 74 | 63 | |

| Went to court (incidents)Data table for Text box 3 Chart 1 Note 3 | 59 | 56 | |

| OutcomesData table for Text box 3 Chart 1 Note 8 | Convicted (for any charge in case)Data table for Text box 3 Chart 1 Note 4 |

76 | 56 |

| Convicted of specific chargeData table for Text box 3 Chart 1 Note 5 | 68 | 48 | |

| Stayed, withdrawn, dismissed or dischargedData table for Text box 3 Chart 1 Note 6 | 21 | 36 | |

| AcquittedData table for Text box 3 Chart 1 Note 7 | 2 | 8 | |

Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics, Uniform Crime Reporting Survey and Integrated Criminal Court Survey. |

|||

Textbox Chart 1 end

In all, 59% of cases involving contact sexual offences against children were processed in adult courts, and 41% in youth courts. Like physical assaults, a custodial sentence in adult courts was less common for cases linked to contact offences than online offences (67% versus 83%) (Text box 3 Chart 2). Probation, instead, was more common for contact offences (17% compared with 6% for online offences). Outcomes for contact offence cases processed in youth courts were generally more in line with online offences, specifically, where probation was the most likely outcome.

Textbox Chart 2 start

Data table for Textbox Chart 2

| Sentencing outcomes | Online offences | Contact offencesData table for Text box 3 Chart 2 Note 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| percent | |||

| Adult | Custody | 83 | 67 |

| Probation | 6 | 17 | |

| Conditional sentence | 3 | 5 | |

| Other sentenceData table for Text box 3 Chart 2 Note 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| Not available (guilty but no sentencing detail) | 6 | 8 | |

| Youth | Custody and supervision | 8 | 9 |

| Probation | 59 | 60 | |

| Deferred custody and supervision | 3 | 7 | |

| Community services | 5 | 1 | |

| Other sentenceData table for Text box 3 Chart 2 Note 2 | 20 | 12 | |

| Not available (guilty but no sentencing detail) | 6 | 11 | |

Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics, Uniform Crime Reporting Survey and Integrated Criminal Court Survey. |

|||

Textbox Chart 2 end

End of text box 3

Retention and outcomes of online child sexual exploitation and abuse by incident characteristicsNote

Studies have shown that the nature and characteristics of crimes that are reported to police often influence how these incidents are treated in, and their progression through, the criminal justice system. For example, sexual assault cases with delays in reporting to police, incomplete or unknown incident information, involving female perpetrators or child victims often have lower retention rates compared with physical assaults (Rotenberg, 2017).

Having multiple violations in an incident did not have much influence on advancement to court

A larger majority (85%) of police-reported online child sexual exploitation and abuse incidents with a secondary violation resulted in charges, compared with incidents with no secondary violations (56%).Note However, similar proportions of both types of incidents proceeded to court (Table 1). In court, similar shares of single-violation and multiple-violation incidents resulted in a finding of guilt for a sexual offence charge (72% and 71%, respectively, Table 2).

Men and boys more often are charged, appear in court and convicted

Aligned with the aim of the Youth Criminal Justice Act to divert youth from the criminal justice system through the use of extrajudicial measures, significantly fewer incidents involving a youth accused (aged 12 to 17 years) resulted in charges, compared with incidents where the accused was an adult. The vast majority of people accused in online child sexual exploitation and abuse incidents were men and boys, varying in ages, while women and girls represented a smaller proportion, and most were youth (Ibrahim, 2022). Three quarters (76%) of cleared incidents involving men and boys as the accused resulted in charges being laid or recommended, compared with just over one-quarter (28%) of cleared incidents involving women and girls as the accused (Table 1).Note After charges were laid or recommended in an incident, a smaller but notable difference was observed in the proportions of incidents with the accused being men and boys (57%), and women and girls (52%) that proceeded to court.

Once in court, incidents involving men and boys as the accused much more often ended in a conviction in general (78%) and, in all, 73% resulted in a guilty finding for a sexual offence charge. In comparison, of the 51 cases that went to court involving a woman or girl charged in an online child sexual exploitation and abuse offence, about half (53% or 27 cases) concluded with a conviction for at least one charge in the case, and over four in ten cases (45% or 23 cases) ended in a conviction specifically for a sexual offence charge.

Vast majority of incidents have a single victim, but charges more common in multiple-victim incidents

Victim information was provided for 7,880 incidents, representing 20% of all online child sexual exploitation and abuse incidents reported to police between 2014 and 2020.Note The vast majority (91%) of these incidents involved one victim, while multiple victims were identified in the remaining 9% of the incidents. Incidents with multiple victims had a higher clearance rate than single-victim incidents, and they also more often led to charges. More specifically, half (49%) of online child sexual exploitation and abuse incidents with a single victim were cleared compared with about two-thirds (64%) of incidents with more than one victim. Moreover, incidents with a single victim had a lower charge rate, with 71% of cleared incidents leading to charges against the accused, compared with 85% of cleared multiple-victim incidents.

Some differences between single-victim and multiple-victim incidents in court were noted. While similar proportions of incidents went to court (60% of cleared by charge single-victim and 61% of cleared by charge multiple-victim incidents), there were notable differences in the court outcomes. For example, 77% of cases linked to single-victim incidents compared to 69% of multiple-victim cases resulted in a conviction for any offence in the case. A finding of guilt for a sexual offence charge was also different (72% of single-victim cases versus 63% of multiple-victim cases).

Once solved, incidents with younger victims more often lead to sexual offence convictions

Unlike the generally consistent differences seen by accused gender, differences by victim gender were generally less prominent across the various stages of the criminal justice process examined. Additionally, some differences were noted based on the age group of the victim. For example, fewer incidents involving child victims under the age of 12 years are solved. But, once solved, these incidents more often led to charges (76%) and resulted in a conviction for any charge in a court case (83%), compared with incidents involving youth victims aged 12 to 17 (70% led to charges and 76% resulted in conviction for any charge in the case).Note Incidents involving child victims also more often resulted in a conviction in court for a sexual offence specifically (81% versus 71% for linked cases involving youth victims).

In addition, clearance and charge rates differed based on accused to victim relationship. For example, while incidents involving a stranger were least likely to be cleared (29%), once an accused was identified, 75% of these incidents resulted in charges being laid or recommended. Incidents involving an authority figure had the highest charge rate, with 94% of incidents that had been cleared leading to charges. The proportion of incidents going to court (where the relationship was known) were some-what similar across relationship types, ranging between 54% and 67%. Once in court, a conviction for any charge in the case was most common for incidents involving strangers (82%), while incidents involving a friend (78%) or a family member had the highest proportions leading to a conviction for a sexual offence (76%).

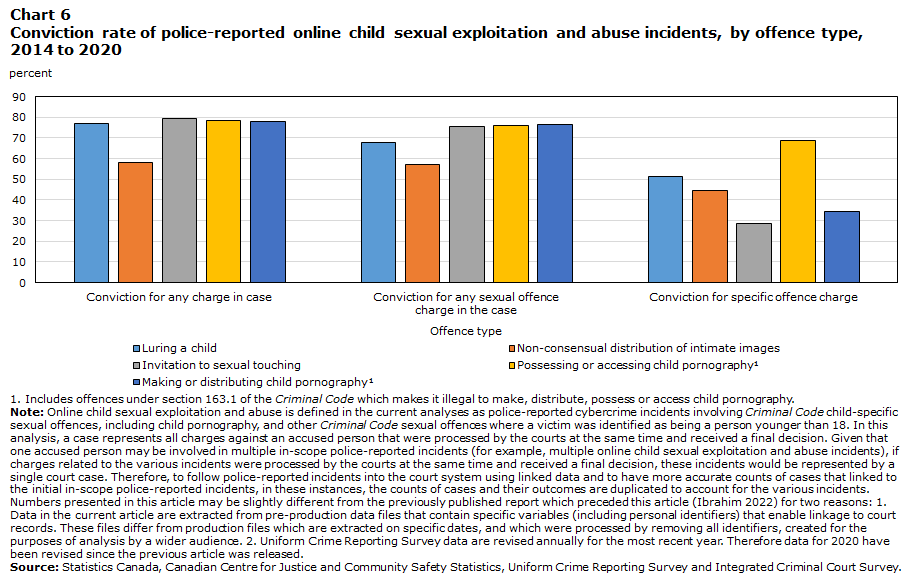

Making or distributing child pornography convictions least common

It was shown earlier that there are differences in how the various categories of online child sexual exploitation and abuse incidents progress through the justice system. For example, as noted, making or distributing child pornography incidents were most likely to drop out before proceeding to court. In court, further differences are observed among the various categories. For example, making or distributing child pornography cases had a relatively high conviction rate for any charge in the case (78%) and for any sexual offence in the case (77%) (Chart 6).Note , Note Yet, a conviction for the specific charge (making or distributing child pornography) was less common, with 35% of linked making or distributing child pornography cases resulting in a conviction for this specific charge. Similarly, despite having high conviction rates for any offence in the case, linked invitation to sexual touching cases less often resulted in a conviction for those specific charges (29%). In these cases, guilty findings were often for other sexual offence charges such as child luring.

Chart 6 start

Data table for Chart 6

| Offence type | Conviction for any charge in case | Conviction for any sexual offence charge in the case |

Conviction for specific offence charge |

|---|---|---|---|

| percent | |||

| Luring a child | 77 | 68 | 51 |

| Non-consensual distribution of intimate images | 58 | 57 | 45 |

| Invitation to sexual touching | 80 | 75 | 29 |

| Possessing or accessing child pornographyData table for Chart 6 Note 1 | 78 | 76 | 69 |

| Making or distributing child pornographyData table for Chart 6 Note 1 | 78 | 77 | 35 |

Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics, Uniform Crime Reporting Survey and Integrated Criminal Court Survey. |

|||

Chart 6 end

At the sentencing stage, across all offence categories of online child sexual exploitation and abuse, relatively smaller proportions of adult cases ended in non-custodial sentences —meaning, custody was often the most likely outcome.Note Proportions of cases resulting in non-custodial sentences generally ranged from 5% for making or distributing child pornography, to 11% for child luring —where, of the cases processed in adult courts, a different sentencing outcome than custody was observed, usually probation. As an exception to these findings, of the 14 linked cases for non-consensual distribution of intimate images processed in adult courts, a non-custodial sentence was likely (71%, or 10 cases).

Start of text box 4

Text box 4

Sextortion trends in Canada

Like online child sexual exploitation and abuse, there are various definitions for sextortion. In general terms, sextortion involves a person threatening to disseminate sexually explicit or intimate images of someone without their consent for the purposes of obtaining additional images, sexual acts or money (Canadian Centre for Child Protection, 2022b; Patchin & Hinduja, 2020; Wolak et al., 2018). Within the scope of online child sexual exploitation and abuse, sextortion is defined as the use of coercion and threats to extort child sexual exploitation images or videos from youth (either by other youth or adult offenders) (Public Safety Canada, 2022). Sextortion on its own is not a criminal offence in the Criminal Code. However, there are circumstances where sextortion could meet the criminal threshold, for example in situations where it involves child pornography, criminal harassment or non-consensual distribution of intimate images. Because of this potential for overlap, the current article uses other sources of data to examine recent trends in sextortion in Canada.

According to Cybertip.ca, Canada’s national tipline for the reporting of online child sexual exploitation, there has been an increase in the reporting of sextortion cases in Canada. Specifically, between December 2021 and May 2022, the national tipline saw a 150% increase in reporting of youths being victims of sextortion online. According to Cybertip.ca, young men and boys are most susceptible to being victims of sextortion, and they are often contacted via social media where they are tricked into sharing sexually explicit images or are unknowingly recorded while exposing themselves over livestream (Canadian Centre for Child Protection, 2022a; Canadian Centre for Child Protection, 2022b).

One in twenty young men and boys report someone sharing or posting embarrassing photos of them online

The 2019 General Social Survey (GSS) on Canadians’ Safety (Victimization) collected information on experiences of online victimization, such as cyber-stalking and cyber-bullying taking place in the preceding five years. While the survey did not collect information on sextortion specifically, the survey collected related information including incidents where someone shared or posted photos that were embarrassing or threatening to the respondent (may not be sexual in nature).

According to the GSS on Victimization, about 1 in 20 (4.2%) young males between the ages of 15 and 24 experienced someone sending out or posting pictures that embarrassed them or made them feel threatened within the preceding five years, in comparison to about 1 in 50 females in the same age group (2.2%). This finding is inline with the sextortion trends observed by Cybertip.ca where young men and boys are overrepresented.

For information on the victimization of men and boys in Canada, see Sutton, 2023.

End of text box 4

Summary

Online child sexual exploitation and abuse encompasses a broad range of behaviours, including those related to child sexual abuse material, sexting materials, sextortion, grooming and luring, live child sexual abuse streaming and made-to-order content. The current article identifies various stages within the justice system to measure retention and attrition of police-reported online child sexual exploitation and abuse; namely, at the clearance, charge and police-to-court stages.

In all, 24% of police-reported online child sexual exploitation and abuse incidents were cleared, meaning an accused person was identified by police in relation to the incident. Once an accused was identified, there were charges laid or recommended in nearly seven in ten (69%) incidents. More than half (56%) of online child sexual exploitation and abuse incidents that led to charges proceeded to court.

In comparison, 73% of physical assaults reported during the same time were cleared and 68% of those cleared resulted in charges. More than seven in ten (72%) physical assault incidents that were cleared by charge went to court. While physical assault had much higher clearance and police-to-court progression rates, relative to online child sexual exploitation and abuse incidents, the story changes once in court. Almost eight in every ten (77%) cases related to an online child sexual exploitation and abuse incident resulted in a conviction for any offence in the case, compared with 50% of linked physical assault cases. Further, after a guilty finding was rendered, 86% of adult cases linked to online child sexual exploitation and abuse incidents resulted in a custody sentence, much higher than the 35% observed for physical assault cases.

Beyond comparisons to physical assaults, differences in justice outcomes for online child sexual exploitation and abuse incidents were also observed among select incident, accused, and victim characteristics. For example, court cases linked to police-reported incidents with men and boys accused more often had charges laid or recommended by police, proceeded to court, and resulted in a finding of guilt. Additionally, once solved, incidents with younger victims, and accused friends or family members more often ended in a guilty finding for a sexual offence.

Understanding the progression of online child sexual exploitation and abuse incidents from police to court, the characteristics of those incidents and outcomes of linked court cases, and how these indicators compare with other types of crime is an important step in measuring the response of the criminal justice system to these incidents, and in gauging some of the challenges and limitations at different stages of the justice system. This information can be used to make informed policy and program decisions in responding to this serious, evolving, and underreported crime.

Detailed data tables

Survey description

Incident-based Uniform Crime Reporting Survey

The Incident-based Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR) Survey collects detailed information on criminal incidents that have come to the attention of police services in Canada. Information includes characteristics of victims, accused persons and incidents. In 2020, data from police services covered 99% of the population of Canada. The count for a particular year represents incidents reported during that year, regardless of when the incident actually occurred.

For the years 2014 and 2015, the municipal police services of Saint John, Québec and Calgary, the Ontario Provincial Police and Canadian Forces Military Police were excluded from the UCR cybercrime data. For the year 2016, the police services of Saint John and Calgary, the Ontario Provincial Police and Canadian Forces Military Police were excluded. For the year 2017, the municipal police service of Saint John and the Ontario Provincial Police were excluded. For the years 2018 and 2019, the municipal police service of Saint John and Canadian Forces Military Police were excluded.

Integrated Criminal Court Survey

The Integrated Criminal Court Survey (ICCS) collects statistical information on adult and youth court cases involving Criminal Code and other federal statute offences. All adult courts have reported to the adult component of the survey since the 2005/2006 fiscal year. Information from superior courts in Ontario, Manitoba and Saskatchewan as well as municipal courts in Quebec was not available for extraction from their electronic reporting systems and was therefore not reported to the survey. Superior court information for Prince Edward Island was unavailable until 2018/2019.

A completed charge refers to a formal accusation against an accused person or company involving a federal statute offence that was processed by the courts and received a final decision. A case is defined as one or more charges against an accused person or company that were processed by the courts at the same time and received a final decision. A case combines all charges against the same person having one or more key overlapping dates (date of offence, date of initiation, date of first appearance, date of decision, or date of sentencing) into a single case.

Record linkage (Uniform Crime Reporting Survey and Integrated Criminal Court Survey)

To infer criminal justice outcomes for police-reported incidents of online child sexual exploitation and abuse, an initial Incident-based Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR) Survey file was created from production files, which contained available personal and incident information to be used for linkage to the Integrated Criminal Court Survey (ICCS). While this methodology section focuses on the linkage process for online child sexual exploitation and abuse incidents, the same steps were also applied to link physical assault incidents and other comparison offences from police to courts.

The initial UCR file contained all police-reported incidents reported between 2014 and 2020 where a cybercrime violation was identified as one of the violations included in the definition of online child sexual exploitation and abuse, as outlined in Text box 1. The file was then subset to only include accused persons that were charged. While analysis in this article were rolled up to the incident level, linkage to ICCS is performed at the charged person level, as the ICCS information linked to the accused is at the charge level. Therefore, multiple ICCS rows is common if a link was possible.

For the linkage, first, a series of record joins between UCR and ICCS were performed based on personal identifiers. Personal identifiers included province, accused person’s date of birth, gender/sex, and Soundex, which is an algorithm that encrypts accused person’s names for confidentiality purposes. Joining online child sexual exploitation and abuse records based on personal identifiers yielded a 62.5% linkage rate, where there was at least one linkage match on some pre-set criteria.

Next, records with at least one match were put through a date matching process to ensure charge dates in ICCS match charge information from UCR. In all, this process resulted in an overall linkage rate of 41.2% for online child sexual exploitation and abuse records. Of note, this linkage rate is based on all counts of accused persons involved in the incidents, and as such does not match the police-to-court retention rate presented in the article, which is based on incident counts only.

Since multiple matches can exist for a single case, as a final step, matched cases underwent a series of violation matching processes to ensure the best court case was selected for each UCR record. Consistencies or similarities in the types of violations seen on the match court case and the UCR violations reported determines the quality of the match. In some instances, even after having personal identifier and date matching, cases would not be considered a good match due to having significantly different violations or unrelated violations. For this reason, the analytical approach taken for analyzing court data was to only consider cases with at least one sexual offence charge in the case to be a good match and is referred to as “going to court”.

Given that sexual offences generally take longer to be processed in court, it is possible that the linkage rate may be biased for online child sexual exploitation and abuse cases that were in court towards the end of the linkage period if they take longer to complete than physical assaults. However, Rotenberg, 2017 showcases that the gap in linkage rates between sexual assaults, more generally, and physical assaults remained consistent toward the end of the study period. Therefore, unless otherwise specified, to maintain the maximum number of linked cases, the current analysis retained all data from 2014 to 2020 for UCR, and 2013/2014 to 2020/2021 for ICCS. However, at the time of the current study, ICCS data was only available up to March 31, 2021.

As with any record linkage undertaking, linkage results are subject to false negative linkage issues where incidents may not have linked due to data quality issues in administrative data (e.g., incorrect birth dates or inconsistent personal identifiers used for the same accused). Consequently, in combination with other methodological considerations explained above, the retention rate from police to court may be an underestimation, and in turn, the attrition rate may be an overestimation.

References

Allen, M. (2017). Mandatory minimum penalties: An analysis of criminal justice system outcomes for selected offences. Juristat. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 85-002-X.

Beitchman, J.H., Zucker, K.J., Hood, J.E. & Akman, D. (1991). A review of the short-term effects of child sexual abuse. Child abuse & neglect. Vol. 15, no. 4: 537-556.

Browne, A. & Finkelhor, D. (1986). Impact of child sexual abuse: A review of the research. Psychological bulletin. Vol. 99, no. 1: 66.

Burczycka, M. & Conroy, S. (2017). Family violence in Canada: A statistical profile, 2015. Juristat. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 85-002-X.

Canadian Centre for Child Protection. (2017). Survivors’ Survey: Full Report 2017.

Canadian Centre for Child Protection. (2022a). How to Talk with Teens about Online Sexual Violence. Factsheet, (accessed December 20, 2022).

Canadian Centre for Child Protection. (2022b). Our results. (accessed December 20, 2022).

Carnes, P. J. (2001). Cybersex, courtship, and escalating arousal: Factors in addictive sexual desire. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity. Vol. 8, no. 1: 45-78.

Department of Justice Canada. (2012). A handbook for police and crown prosecutors on criminal harassment. Serving Canadians. Catalogue No. J2-166/2012E-PDF.

End Child Prostitution and Trafficking (ECPAT) International. (2016). Terminology Guidelines for the Protection of Children from Sexual Exploitation and Sexual Abuse.

Felson, R. B. & Paré, P.P. (2005). The reporting of domestic violence and sexual assault by nonstrangers to the police. Journal of Marriage and Family. Vol. 67, no. 3: 597-610.

Finkelhor, D., Wolakand, J. & Berliner, J. (2001). Police reporting and professional help seeking for child crime victims: A review. Child Maltreatment. Vol. 6, no. 1. p. 17-30.

Hailes, H.P., Yu, R., Danese, A. &Fazel, S. (2019). Long-term outcomes of childhood sexual abuse: an umbrella review. The Lancet Psychiatry. Vol. 6, no. 10: 830-839.

Hanson, E. (2017). The impact of online sexual abuse on children and young people. Online risk to children: Impact, Protection and Prevention: 97-122.

Heidinger, L. (2022). Profile of Canadians who experienced victimization during childhood, 2018. Juristat. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 85-002-X.

Ibrahim, D. (2022). Online child exploitation and abuse in Canada: A statistical profile of police-reported incidents and court charges, 2014 to 2020. Juristat. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 85-002-X.

Martin, J. (2015). Conceptualizing the harms done to children made the subjects of sexual abuse images online. Child & Youth Services. Vol. 36, no. 4: 267-287.

New Brunswick-Office of Attorney General. (2017). Public Prosecutions Operational Manual. (accessed February 8, 2023).

Olafson, E. (2011). Child sexual abuse: Demography, impact, and interventions. Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma. Vol. 4, no. 1: 8-21.

Ospina, M., Harstall, C. & Dennett, L. (2010). Sexual exploitation of children and youth over the internet: A rapid review of the scientific literature. Institute of Health Economics.

Patchin, J.W. & Hinduja, S. (2020). Sextortion among adolescents: Results from a national survey of U.S. youth.Sexual abuse, 32(1), 30-54.

Public Safety Canada. (2022). Child Sexual Exploitation on the Internet. Countering Crime. (accessed March 8, 2022).

Rotenberg, C. (2017). From arrest to conviction: Court outcomes of police-reported sexual assaults in Canada, 2009 to 2014: Highlights. Juristat. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 85-002-X.

Say, G. N., Babadağı, Z., Karabekiroğlu, K., Yüce, M. & Akbaş, S. (2015). Abuse characteristics and psychiatric consequences associated with online sexual abuse. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking. Vol. 18, no. 6: 333-336.

Sutton, D. (2023). Victimization of men and boys in Canada, 2021. Juristat. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 85-002-X.

Taylor, S.C. & Gassner, L. (2010). Stemming the flow: Challenges for policing adult sexual assault with regard to attrition rates and under-reporting of sexual offences. Police Practice and Research, 11(3), 240-255

Thompson, M., Sitterle, D., Clay, G. & Kingree, J. (2007). Reasons for not reporting victimizations to the police: Do they vary for physical and sexual incidents? Journal of American College Health. Vol. 55, no. 5. p. 277-282.

WeProtect Global alliance. (2019). Global Threat Assessment 2019; Working together to end the sexual exploitation of children online.

Whittle, H. C., Hamilton-Giachritsis, C. & Beech A. R. (2013). Victims’ voices: The impact of online grooming and sexual abuse. Universal Journal of Psychology. Vol. 1, no. 2: 59-71.

Wolak, J., Finkelhor, D., Walsh, W., & Treitman, L. (2018). Sextortion of minors: Characteristics and dynamics.Journal of Adolescent Health, 62(1), 72-79.

- Date modified: