Online child sexual exploitation and abuse in Canada: A statistical profile of police-reported incidents and court charges, 2014 to 2020

By Dyna Ibrahim, Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics

Highlights

- Between 2014 and 2020, police reported 10,739 incidents of online sexual offences against children (where the victim had been identified by police) and 29,028 incidents of online child pornography (where the victim had not been identified).

- The overall rate of police-reported incidents of online child sexual exploitation and abuse has been on an upward trend, increasing from 50 incidents per 100,000 population in 2014, when cybercrime data were first collected nationally, to 131 per 100,000 in 2020.

- Luring a child accounted for the large majority (77%) of online sexual offences against children. In addition, 11% were non-consensual distribution of intimate images, 8% were invitation to sexual touching and 5% were other online sexual offences against children. More than two-thirds (68%) of child pornography incidents involved making or distributing child pornography and about one-third (32%) were possessing or accessing child pornography.

- Seven in ten (73%) victims identified in online sexual offences against children were girls aged 12 to 17 and 13% were girls under age 12. Boys aged 12 to 17 accounted for 11% of victims and the remaining 3% were boys under age 12.

- About two out of three (65%) victims of online child sexual offences were victimized by a stranger (39%) or a casual acquaintance (25%), and nearly one in four (23%) were victimized by a friend (8%), a family member (7%) or an intimate partner (7%).

- More than one in four (27%) online sexual offences against children involved a secondary violation, usually child pornography (17% of all online sexual offences against children).

- More than four in ten (44%) police-reported incidents of online sexual offences against children were cleared (or solved). Charges were laid or recommended in 74% of all sexual offences against children where an accused had been identified in relation to the incident. In contrast, the large majority (85%) of child pornography incidents were not cleared. Among child pornography incidents where an accused had been identified, 64% were cleared by charge.

- The vast majority (91%) of people accused of online child sexual exploitation and abuse (including sexual violations against children and child pornography) were men and boys—and they were generally much older than victims. The median age of men and boys accused of online sexual offences against children was 24 years, and men and boys accused of child pornography had a median age of 29 years. Non-consensual distribution of intimate images online involved victims and accused persons with a median age of 15.

- The Criminal Code includes the use of telecommunications in its definition of luring a child, and agreement or arrangement (sexual offence against a child). In addition to these two types of offences, police-reported data show that child pornography and non-consensual distribution of intimate images (involving child victims) are often committed online. In total, between 2014/2015 and 2019/2020, criminal courts in Canada processed 27,522 charges related to these child sexual offences which were likely committed online. More than eight in ten (85%) were processed in adult courts.

- Charges related to child sexual offences likely committed online were more likely to result in a guilty decision than charges involving other (likely offline) sexual violations against children: More than one in three (36%) court charges of child sexual offences likely committed online resulted in the accused being found guilty, compared with 29% of offline charges. Charges related to non-consensual distribution of intimate images were most likely to result in a guilty decision (45%).

- About six in ten (61%) court cases involving at least one charge related to a child sexual offence likely committed online involved a guilty decision as the most serious decision rendered for any of those charges. This compared to 41% of cases with at least one charge of child sexual offences likely committed offline.

- Eight in ten (80%) adults convicted of a child sexual offence likely committed online were sentenced to custody, a proportion slightly lower than the proportion of adults sentenced to custody after a guilty finding for child sexual offences likely committed offline (83%).

More than ever, technology, and the Internet in particular, has become an integral part of the daily lives of Canadians. In 2018, it was estimated that all but about 1% of Canadian households with children had access to the Internet (Frenette et al. 2020). Concerns over online safety and online victimization were exacerbated with many daily activities moving online in 2020 as Canadians grappled with the COVID-19 pandemic. As public health measures were put in place across Canada to combat the virus, many children relied on virtual learning and spent more time indoors and online (Moore et al. 2020). Undoubtedly, there are many advantages to using technology and, for children, being connected helps them learn, grow and fulfil their potential (UNICEF 2017). However, the use of technology and the Internet also comes with risks. Among the most serious risks of spending time online, especially for children, is the susceptibility to online sexual exploitation and abuse (ECPAT 2016; UNICEF 2017).

There is no one standard definition for online child sexual exploitation and abuse. It encompasses a wide range of behaviours and situations, from sexual solicitation of a child—with or without a response from the child—to sexual grooming (the trust-building period prior to abuse), to sexual interaction online (cybersex) or offline (meeting in person), to accessing, producing or sharing images related to the abuse of children and youth (De Santisteban and Gamez-Guadix 2018; Kloess et al. 2014). It can be committed by adults or youths, and it can involve strangers or family members and acquaintances (Mitchell et al. 2005). Generally, in the Canadian legal context, the crime of online child sexual exploitation and abuse includes: child sexual abuse material, self-generated materials and sextingNote (often distributed without consent), sextortion,Note grooming and luring, live child sexual abuse streaming and made-to-order content (Public Safety Canada 2022).

The short- and long-term effects of childhood sexual victimization are well documented (Beitchman et al. 1991; Browne and Finkelhor 1986; Hailes et al. 2019; Olafson 2011). More recently, research on the effects of online child sexual exploitation has found that victims of this crime often suffer a range of negative impacts including psychological difficulties, negative sexual development, and subsequent substance misuse and depressive symptomology (Carnes 2001; Hanson 2017; Ospina et al. 2010; Say et al. 2015; Whittle et al. 2013a). Additionally, victims of online child sexual exploitation continue to experience victimization through the actual or threatened re-distribution of their images, long after any contact abuse has ended (Canadian Centre for Child Protection 2017; Martin 2015).

Every child has a right to protection, as a fundamental human right. Children (under age 18) also have specific rights, recognized in the 1989 Convention on the Rights of the Child, given their vulnerability and dependence. In 1991, Canada ratified the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, pledging to protect children from all forms of exploitation and abuse, among other forms of harm and endangerment. The provision and protection of children’s Convention rights is the primary responsibility of governments at all levels (UNICEF Canada 2022). Canada has also signed on to the Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child on the sale of children, child prostitution and child pornography (United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner 2022). As the use of technology among Canadians has increased in recent years, so too have Canada’s efforts to protect children from online predators. In 2004, the National Strategy for the Protection of Children from Sexual Exploitation on the Internet was developed to combat this crime in Canada. Since then, the National Strategy has been renewed and expanded, and in 2019, a renewed commitment was made with the Government of Canada allocating funds to supports efforts to raise awareness, reduce the stigma associated with reporting, increase Canada’s ability to pursue and prosecute offenders and work together with the digital industry to find new ways to combat the sexual exploitation of children online. Most recently, budget 2021 proposed to provide $20.7 million over five years, starting in 2021-22, for the Royal Canadian Mounted Police to enhance its ability to pursue online child sexual exploitation investigations, identify victims and remove them from abusive situations, and bring offenders to justice—including those who offend abroad (Public Safety Canada 2022).

Currently, little is known about the prevalence and characteristics of online child sexual exploitation and abuse within the Canadian context. To provide some insight, this Juristat article presents an analysis of police-reported data from the Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR) Survey where children and youth under the age of 18 were victims of Criminal Code sexual offences, and where information and communication technology was integral in the commission of the offence—better known as cybercrime. Moreover, data on court charges and cases involving sexual offences against children (which likely involved an online component) are presented using data from the Integrated Criminal Court Survey (ICCS), along with the outcomes of these cases.

Generally, only a fraction of sexual offences come to the attention of police and, subsequently, the courts (Burczycka and Conroy 2017). Further, when a sexual offence involves a child victim, the incident is even more likely to be underreported for a number of reasons. For example, some children—especially younger children—may be unable to report or seek help, may fear reporting, or may not know how to report or seek help (Finkelhor et al. 2001; Taylor and Gassner 2010). Additionally, as technology becomes more advanced, so too do the tactics used by offenders to lure and groom children for sexual exploitation and abuse, and with improved anonymity capabilities they can better hide their activities (WeProtect Global Alliance 2019). This creates challenges for law enforcement to keep up with investigating incidents related to this crime, to identify victims for protection and to bring offenders to justice. Nevertheless, the analyses presented in this article can provide a baseline of information on incidents of online child sexual exploitation and abuse that did come to the attention of Canadian police and Canadian criminal courts to better inform programs and policies related to combatting this crime. In addition, to give a more complete picture of the occurrence of this crime in Canada, some publicly available data from Canada’s national tipline for the reporting of child sexual exploitation online, Cybertip.ca, are presented in Text box 4.

This report was produced with the funding support of Public Safety Canada.

Start of text box 1

Text box 1

Measuring and defining online child sexual exploitation and abuse using

police-reported data

Beginning in 2014,Note the Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR) Survey has collected information related to online crime through the use of a cybercrime flag. An incident is flagged as a cybercrime when the crime targets information and communication technology (ICT), or when the crime used ICT to commit the offence.

ICT includes, but is not limited to, the Internet, computers, servers, digital technology, digital telecommunications devices, phones and networks. Crimes committed over text and through messages using social media platforms are also considered cybercrime activity.

Police services can report up to four violations for each incident reported in the UCR. The UCR classifies incidents according to the most serious violation occurring in the incident (generally the offence which carries the longest maximum sentence under the Criminal Code), with violations against the persons always classified as more serious than other violations. In order to maintain consistency in measuring the cyber aspect of crime, analysis of cybercrime data are based on the most serious violation in the incident which was most likely to have involved ICT, referred to as the cybercrime violation (see Text box 2).

Incidents involving child pornography where an actual child victim was not identified are reported to the UCR with the most serious violation being “child pornography.” When an actual child victim is identified, the incident is reported to the UCR with the most serious violation as sexual assault, sexual exploitation, or other sexual violations against children, and child pornography may be reported as a secondary violation. Because of this difference, as well as to account for the complexities associated with investigating incidents of child pornography, analyses in this article are mainly presented in terms of two categories of offences: online sexual offences against children, which allows for the analysis of incident and victim characteristics, and online child pornography, which includes incidents where the victim was not identified. However, a summary of trends in both categories of offences are presented together at the outset.

Online sexual offences against children include:

- Sexual violations against children, which involve the following Criminal Code offences: sexual interference, invitation to sexual touching, sexual exploitation, parent or guardian procuring sexual activity, householder permitting prohibited sexual activity, luring a child, agreement or arrangement (sexual offences against a child) and bestiality (in presence of, or incites, a child),Note and

- Other sexual offences, which are Criminal Code sexual offences that are not specific to children but where a victim was identified as being younger than 18. These include: non-consensual distribution of intimate images, sexual assault (levels 1, 2 and 3), sexual exploitation of person with disability, bestiality (commits, compels another person), voyeurism, incest and other sexual crimes.

Online child pornography includes incidents excluded from the category of sexual offences against children, and includes offences under section 163.1 of the Criminal Code which makes it illegal to make, distribute, possess or access child pornography.

Keeping with the above noted definitions and structure of the UCR, the current article therefore defines online child sexual exploitation and abuse as police-reported cybercrime incidents involving Criminal Code child-specific sexual offences, including child pornography, and other Criminal Code sexual offences where a victim was identified as being a person younger than 18.

Given that there is no specific definition for the crime of online child sexual exploitation and abuse in the Criminal Code, details of how court charges were defined in this article are presented in the courts section below.

In this article, the terms “online,” “cyber” and “technology-facilitated (or use)” are used interchangeably and, in the context of police-reported incidents, they all refer to situations where ICT was indicated. Further, “children and youth” refer to people aged 17 and younger.Note

End of text box 1

Online child sexual exploitation and abuse increases by more than one-quarter in first year of the COVID-19 pandemic

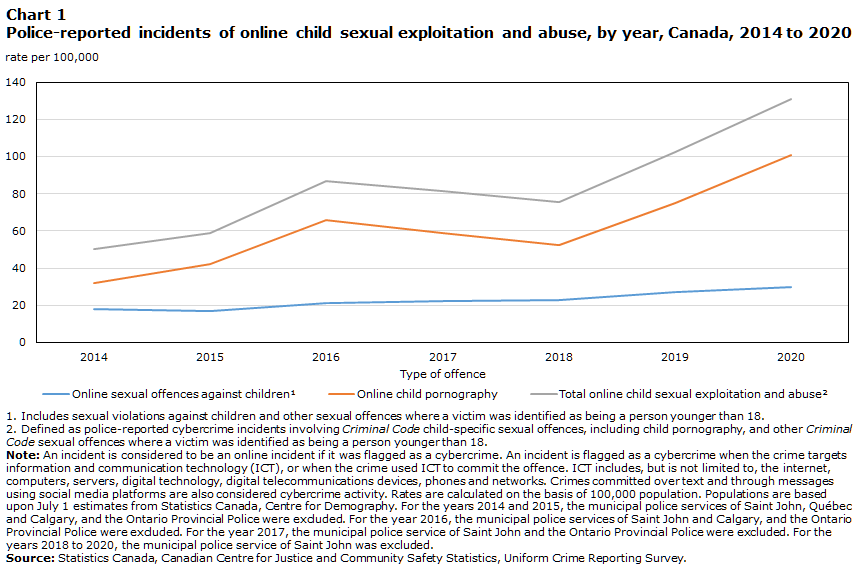

Since 2014, when nationally representative cybercrime data first became available, the number of incidents constituting police-reported online child sexual exploitation and abuse has generally been on an upward trend. By 2020, the number of incidents reported annually had significantly increased from 3,080 incidents in 2014 to 9,441. When the number of children in the Canadian population is taken into account, the overall rate of this crime nearly tripled during this time, from 50 incidents to 131 incidents per 100,000 Canadians below the age of 18 (Chart 1).

Chart 1 start

Data table for Chart 1

| Type of offence | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rate per 100,000 | |||||||

| Online sexual offences against childrenData table for Chart 1 Note 1 | 18 | 17 | 21 | 23 | 23 | 27 | 30 |

| Online child pornography | 32 | 42 | 66 | 59 | 52 | 75 | 101 |

| Total online child sexual exploitation and abuseData table for Chart 1 Note 2 | 50 | 59 | 87 | 81 | 76 | 102 | 131 |

Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics, Uniform Crime Reporting Survey. |

|||||||

Chart 1 end

It is important to note that increases in the number of police-reported incidents may in part be attributable to an uptake in the use of the cybercrime flag since its inaugural year. But, there have been other indications of the occurrence of this crime being indeed on the rise in Canada including reports from Cybertip.ca, Canada’s national tipline for reporting child sexual exploitation online (Public Safety Canada 2021). The increases in this crime are attributable to a number of factors including wider access to the Internet across the country, coupled with its increased use and the proliferation of cell phones and other smart devices among children. See Text Box 4 for more information from Cybertip.ca.

Between 2019 and 2020, the overall police-reported rate of crime—including sexual assaults—decreased after several years of increases (Moreau 2021). These decreases were expected as lockdown conditions brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic meant there were fewer opportunities for in-person crimes to take place as people spent more time at home and many businesses closed. However, in contrast, cybercrime in general was on the rise with 31% more police-reported cybercrime incidents in 2020 than in 2019. In 2020, the first year of the pandemic, the rate of police-reported online child pornography (101 per 100,000 population) was 35% higher than in 2019, while the rate of online sexual offences against children was 10% higher (30 versus 27 per 100,000).Note Note

There was a 28% overall increase in the rate of online child sexual exploitation and abuse between 2019 and 2020. This increase was in large part driven by increases in the rates of both possessing or accessing child pornography (33% increase between 2019 and 2020) and making or distributing child pornography (35% increase), as well as a 22% increase in the rate of child luring offences from the previous year (Chart 2). Child pornography incidents were the main drivers of change in the overall rate of online child sexual exploitation and abuse over the seven-year period.

Chart 2 start

Data table for Chart 2

| Type of offence | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rate per 100,000 | |||||||

| Luring a child | 15 | 14 | 17 | 16 | 17 | 19 | 24 |

| Non-consensual distribution of intimate imagesData table for Chart 2 Note 1 | Note ..: not available for a specific reference period | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 |

| Invitation to sexual touching | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Other sexual offences against childrenData table for Chart 2 Note 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| Possessing or accessing child pornographyData table for Chart 2 Note 3 | 32 | 28 | 20 | 16 | 9 | 16 | 21 |

| Making or distributing child pornographyData table for Chart 2 Note 3 | Note ..: not available for a specific reference period | 14 | 46 | 43 | 44 | 59 | 80 |

|

.. not available for a specific reference period 0 true zero or a value rounded to zero

Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics, Uniform Crime Reporting Survey. |

|||||||

Chart 2 end

Characteristics of online sexual offences against children and youth

Police-reported data show that between 2014 and 2020 there were a total of 10,739 incidents of online sexual offences against children and youth, representing an average annual rate of 23 incidents per 100,000 Canadian children and youth.Note Note

The offence of luring a child made up the large majority (77%) of the incidents reported between 2014 and 2020 (Table 1). In 2015, the Protecting Canadians from Online Crime Act came into effect, making non-consensual distribution of intimate images an offence. From its introduction into the Criminal Code in 2015 and up to 2020, this offence accounted for 11% of the online sexual offences against children, followed by invitation to sexual touching (8%), and other online sexual offences against children made up the remaining 5% of the incidents.Note

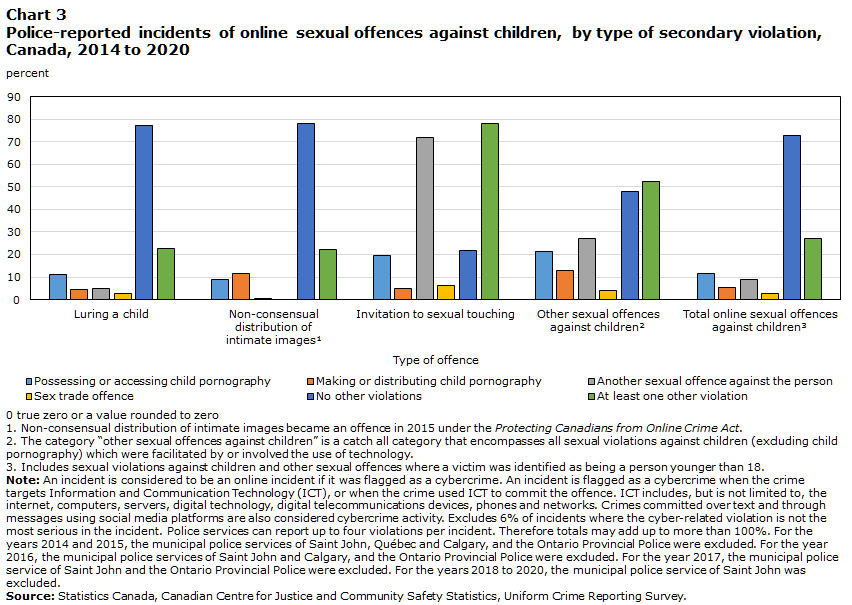

One in six online sexual offences include a secondary offence of child pornography

Police services are able to report up to four violations for each incident to the UCR. In nearly three-quarters (73%) of online sexual offences against children reported between 2014 and 2020, no secondary violations were reported.Note More than one in four (27%) incidents included at least one other violation, and more than half (53%) of these involved child pornography. Said otherwise, about one in six (17%) incidents of online child sexual violations against children also involved child pornography offences (Chart 3). Possessing or accessing (12%) child pornography was more commonly reported as a secondary violation compared to making or distributing (6%).Note About one in ten (9%) incidents also involved other sexual offences.

Chart 3 start

Data table for Chart 3

| Type of offence | Possessing or accessing child pornography | Making or distributing child pornography | Another sexual offence against the person | Sex trade offence | No other violations | At least one other violation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| percent | ||||||

| Luring a child | 11 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 77 | 23 |

| Non-consensual distribution of intimate imagesData table for Chart 3 Note 1 | 9 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 78 | 22 |

| Invitation to sexual touching | 19 | 5 | 72 | 6 | 22 | 78 |

| Other sexual offences against childrenData table for Chart 3 Note 2 | 21 | 13 | 27 | 4 | 48 | 52 |

| Total online sexual offences against childrenData table for Chart 3 Note 3 | 12 | 6 | 9 | 3 | 73 | 27 |

0 true zero or a value rounded to zero

Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics, Uniform Crime Reporting Survey. |

||||||

Chart 3 end

Police-reported incidents of online sexual offences against children rarely indicated the co-occurrence of offences related to the sex trade (3%). When a sex-trade-related offence was reported as a secondary violation, it was usually in conjunction with the offence of invitation to sexual touching (6%). Given that the UCR classifies incidents according to the most serious violation occurring in the incident, no human trafficking offences (whether Criminal Code offences or violations against the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act which makes trafficking of persons illegal) were reported as secondary violations in online child sexual offences. However, it is worth noting that examining data reported between 2018 and 2020 involving human trafficking as the most serious violation in the incident revealed a co-occurrence of human trafficking and child sexual offences, though there was no indication that these child-specific offences were facilitated online. More specifically, 11% of human trafficking incidents reported over these three years, where a secondary violation was reported, involved sexual offences against children or child pornography, but there was no indication that the child sexual violations were cybercrime.Note It has been reported that sexually exploiting children, particularly through grooming and luring them online, can sometimes lead child victims into the sex trade or human trafficking. For example, personal information, images and videos used or shared online can be accessed and used by traffickers to identify, communicate with and lure potential victims, or to blackmail or coerce them. However, these pathways cannot be measured through the UCR (Atwater Library and Computer Centre, 2017; Farley et al. 2013; Kotrla 2010; Trafficking in America Task Force 2021).

It is important to note that while police services are able to report up to four violations for each incident to the UCR, reporting of these secondary violations is not mandatory. Therefore information on related offences may be underestimated.

Youth aged 12 to 17 make up the majority of victims of online child sexual offences, and victims are usually girls

In total, 7,743 children were identified as victims of sexual violations facilitated through online means between 2014 and 2020 (Table 2).Note In addition, 1,243 children were also identified as victims in these incidents, but where the cybercrime violation was not the most serious violation against them.Note

Youth between the ages of 12 and 17 made up the majority of victims of online child sexual offences. More specifically, more than seven in ten (73%) victims identified in online child sexual offences were older girls aged 12 to 17, and 13% of all victims were younger girls under 12 (Chart 4).Note

Boys were generally less likely to be victims in police-reported incidents of online child sexual offences. It is important to note, however, that sexual offences involving men and boys as victims are often underreported (Sivagurunathan et al. 2019; Weiss 2009). Older boys aged 12 to 17 were more likely to be the victims identified in online child sexual offences than boys younger than this age range (11% and 3%, respectively).

Chart 4 start

Data table for Chart 4

| Type of offence | Children (aged 11 years and younger) | Youth (aged 12 to 17 years) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Girls | Boys | Girls | Boys | |

| percent | ||||

| Luring a child | 15 | 3 | 71 | 11 |

| Non-consensual distribution of intimate imagesData table for Chart 4 Note 1 | 1 | 1 | 86 | 11 |

| Invitation to sexual touching | 15 | 2 | 72 | 12 |

| Other sexual offences against childrenData table for Chart 4 Note 2 | 14 | 7 | 64 | 15 |

| Total online sexual offences against childrenData table for Chart 4 Note 3 | 13 | 3 | 73 | 11 |

Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics, Uniform Crime Reporting Survey. |

||||

Chart 4 end

These findings are consistent with previously published results which found that the rate of police-reported violent crime is highest against girls aged 12 to 17, and that the rate of sexual offences in particular are higher among girls in this age group compared with their boy counterparts, and younger girls and boys (Conroy 2018; Cotter and Beaupré 2014).

Although they made up the large majority of victims in all offence categories, girls aged 12 to 17 were especially overrepresented as targets of non-consensual distribution of intimate images (86%). Meanwhile, about one in ten (11%) victims of this crime were boys in this age group.

Children younger than 12 were generally less likely to be the victims in police-reported incidents of online sexual exploitation and abuse. However, when a younger child victim was identified in these incidents, they were more often the victims of other violent sexual offences facilitated by technology. More specifically, one in seven (14%) victims of other online sexual offences were girls younger than 12, and 7% were boys younger than 12.

Overall, young children under the age of 8 were underrepresented in police-reported incidents of online sexual offences (1%). The lower proportion of very young children being reported as victims of online sexual offences may be attributable to a number of factors including: less access to online communication and reduced autonomy, and behavioural differences between younger and older children (Kuoppamäki et al. 2011; Ospina et al. 2010; Whittle et al. 2013b). Additionally, as reporting to police among younger children depends on the adults around them, it is likely that police-reported incidents involving very young children are an underestimation—related to cybercrime or otherwise. Results from the 2017 International Survivors Survey conducted by the Canadian Centre for Child Protection show that for over half (56%) of victims whose child sexual abuse had been recorded, the abuse began before age 5 (Canadian Centre for Child Protection 2017).

About two in three victims of online sexual offences are victimized by a stranger or casual acquaintance

Previously published police-reported data show that, in general, woman and girl victims of sexual offences are less commonly victimized by a stranger (Conroy 2018; Rotenberg 2017). Conversely, and likely due to the anonymity of crimes committed online, about two-thirds (65%) of victims of online child sexual offences were victimized by a stranger (39%) or a casual acquaintance (25%) and for nearly one in four victims (23%) the perpetrator was someone close to them, either a friend (8%), a family member (7%) or an intimate partner (7%) .Note Note However, there were variations depending on the type of offence and age group of the victim (Table 3).

Children younger than 12, who represented 15% of all victims of online sexual offences against children, were more often victimized by a stranger (57% compared with 36% of youth victims). Children younger than 12 were more likely than youth aged 12 to 17 to be victims of online sexual offences involving a family member as the perpetrator (12% versus 6%). It has been found that when it comes to online child sexual exploitation and abuse, younger children are particularly vulnerable to abuse by an adult or older peers within the family or in a setting or relationship where there is a position of trust (UNICEF 2017). Younger children who were victims of luring were most often victimized by a stranger (63%).

Like younger children, youth aged 12 to 17 who were victims of luring a child were also most often victimized by a stranger, but fewer youth were victimized by a stranger compared with younger children (45% versus 63%). A casual acquaintance was accused of luring a child for one-quarter (25%) of youth victims. Similarly, invitation to sexual touching often involved a stranger (30%) or a casual acquaintance (31%) as the accused among youth victims. Among younger children who were victims of this crime, 38% were victimized by a stranger and 11% by a casual acquaintance. A notable 17% of victims younger than 12 were the victims of invitation to sexual touching by a family member, a proportion almost double that of youth victims of this crime (9%).

Almost half of youth victims of non-consensual distribution of intimate images victimized by intimate partner or friend

The offence of non-consensual distribution of intimate images is a crime that can involve people of any age as victims or offenders. However, research suggests that “sexting”—the act of consensually sharing sexually explicit messages, images or self-generated sexualised images of themselves—is quite common among youth (Chaudhary et al. 2017; Madigan et al. 2018; Soyeon et al. 2020). Given that the act of sexting is popular among youth, there may be an increased likelihood of youth sharing such images beyond the intended recipient.

Non-consensual distribution of intimate images, an offence predominantly involving youth aged 12 to 17, more commonly involved an accused person known to the victim. Almost half (48%) of all youth victims of this offence were victimized by an intimate partner (28%) or a friend (21%), and for more than one-third (36%) of youth victims, the accused was a casual acquaintance.Note A stranger was the accused for about one in ten (11%) victims.

The prevalence of this crime among youth, combined with the overrepresentation of youth as both perpetrators (as seen below) and victims of non-consensual distribution of intimate images, along with the finding that this type of offence typically involved victims and accused persons known to each other, is an indication that youth are particularly vulnerable to this type of crime.

Charges more likely when incidents involved multiple violations

Crimes that are sexual in nature are less likely to be solved by police for various reasons, including investigative challenges as well as the characteristics of the incidents which come to the attention of police, such as delays in reporting and less available case information compared to physical assaults, for example (Rotenberg 2017). The occurrence of these crimes, or even some aspects of their facilitation online, can present further complications and challenges for investigators to identify and locate perpetrators.

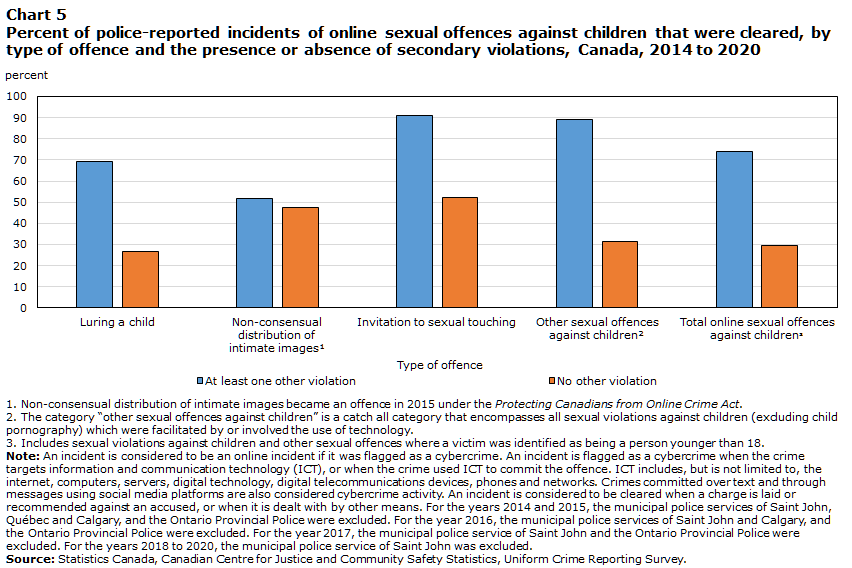

More than half (56%) of online child sexual offences reported to police between 2014 and 2020 were not cleared, meaning police were not able to identify an accused person in relation to the incident, while the remaining 44% of the incidents were solved. The majority (74%) of incidents that were cleared were cleared by the laying or recommendation of a charge, and 26% were cleared otherwise.Note Overall, charges were laid or recommended in less than one-third (32%) of all online child sexual offence incidents that came to the attention of police during this time.

Incidents involving at least one other violation were much more likely to be solved. Overall, more than seven in ten (74%) incidents of online sexual offences against children where there was a secondary violation were cleared (Chart 5). In comparison, three in ten (30%) incidents with no other violations were cleared. Further, incidents were much more likely to be cleared with a charge when they involved multiple violations. More specifically, among incidents that were cleared, charges were laid or recommended in the large majority (88%) of online child sexual offence incidents involving secondary violations (Table 4). This was much higher than the proportion of incidents resulting in charges being laid or recommended when there were no secondary violations in the incident (58%).

Chart 5 start

Data table for Chart 5

| Type of offence | At least one other violation | No other violation |

|---|---|---|

| percent | ||

| Luring a child | 69 | 27 |

| Non-consensual distribution of intimate imagesData table for Chart 5 Note 1 | 52 | 47 |

| Invitation to sexual touching | 91 | 52 |

| Other sexual offences against childrenData table for Chart 5 Note 2 | 89 | 31 |

| Total online sexual offences against childrenData table for Chart 5 Note 3 | 74 | 30 |

Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics, Uniform Crime Reporting Survey. |

||

Chart 5 end

Incidents involving invitation to sexual touching had the highest charge rate (96%). However, this was also the type of online sexual offence against children and youth most likely to involve multiple violations in the incident. Nevertheless, charges were more common in incidents involving this crime when there was a secondary violation compared to those without (97% versus 83%).

Non-consensual distribution of intimate images least likely to lead to charges

Just under half (48%) of police-reported non-consensual distribution of intimate images, a crime less likely to involve secondary violations, were cleared. Further, these incidents were least likely to result in charges—about three in ten (29%) incidents where an accused was identified were cleared by charge.

Notably, non-consensual distribution of intimate images was most likely to be cleared otherwise (71%, compared to 26% overall). Given that youth make up the majority of people accused in non-consensual distribution of intimate images of children (see below), this finding is in line with a previous study which found that youth were less likely to be charged in peer-to-peer sexual offences than when the incident involved a child victim and a youth accused (Allen 2016).Note The Youth Criminal Justice Act ensures that efforts are made to deal with youth accused of crime through means other than the laying of charges, such as giving them warnings or placing them in diversionary programs. The rate of youth who are formally charged has therefore been on a decline (Keighley 2017).

When the analysis of incident clearance rates is limited to incidents where victim data were provided, incidents that involved child victims were less likely to be cleared than incidents where the victims were youth (30% versus 49%).Note Although incidents involving child victims were also less likely to have a secondary violation than those involving youth victims (23% versus 31%), the finding was still true even after taking into account the existence of a secondary violation in the incident: 61% of incidents involving both child victims and secondary violations were cleared, compared with 72% of incidents involving youth victims and secondary violations. Similarly, 20% of incidents involving child victims without secondary violations were cleared compared to 39% of incidents involving youth victims where there were no secondary violations. This finding might speak to the challenges of investigating incidents involving younger children as they are less likely to be witnesses or provide detailed information about the incident.

Start of text box 2

Text box 2

Online child sexual offences involving a more serious violation, and other

incidents involving making sexually explicit material available to children

When an incident has been flagged as Cybercrime, any or all of the violations in the incident may have involved the use of technology. For analytical purposes, a specific violation within each cybercrime incident is identified as the cyber-related violation. This violation is the most serious in the incident which was most likely to have involved information and communication technology.

In the vast majority (98%) of incidents reported by police between 2014 and 2020 involving online child sexual crimes, the cybercrime violation was the most serious offence in the incident. For a minority of incidents (2% or 812 incidents), a different violation in the incident was identified as the most serious in the incident. These incidents most often involved luring a child (37% or 298 incidents), invitation to sexual touching (31% or 253 incidents) or child pornography (22% or 182 incidents) as the cybercrime violation.

In the large majority (75%) of these incidents where the cyber violation was identified as a secondary offence, sexual interference was the most serious violation reported and one in five (20 %) involved sexual assault (level 1). Charges were laid in nearly nine out of ten (88%) incidents involving online child sexual offences where there was a more serious violation in the incident—and this proportion jumps to 96% when looking at all incidents that were solved, and 4% were cleared otherwise.

Making sexually explicit material available to children

Section 171.1 of the Criminal Code makes transmitting, making available, distributing or selling sexually explicit material to a child for the purpose of facilitating the commission of an offence, in and of itself, a criminal offence. Understanding the characteristics of this crime in the context of online child sexual exploitation and abuse is critically important as it has been found to be a method that offenders employ to groom child victims for exploitation as well as during the abuse. For example, sexual material is often introduced by offenders soon after contacting children online or by showing child victims adult pornography during the commission of the abuse (Canadian Centre for Child Protection 2017; Winters et al. 2017).

Between 2014 and 2020, there were 602 police-reported technology-facilitated incidents of making sexually explicit material available to children. Similar to online child sexual exploitation and abuse, more incidents were reported with each passing year since cybercrime data became available, with 25 incidents reported in 2014 compared with 147 incidents in 2020.

Making sexually explicit material available to children was the most serious violation in almost all (96%) incidents where this cybercrime was indicated. Similar to incidents of online child sexual exploitation and abuse, the remaining 25 incidents involved sexual interference as the most serious violation in the incident.

A secondary violation was reported in over half (53%) of online incidents of making sexually explicit material available to children, with child luring being the most commonly reported secondary violation (39% of all cyber incidents of making sexually explicit material available to children where it was the most serious violation in the incident). Note More than one in ten (13%) incidents involved possessing or accessing child pornography and 7% had making or distributing child pornography as a secondary violation.

Over half (53%) of online incidents of making sexually explicit material available to children were cleared—most (83% of all cleared incidents) by the laying or recommendation of a charge. Consistent with what was seen in police-reported online child sexual exploitation and abuse incidents more generally, the charge rate was driven by the presence of a secondary violation: when the incident involved a secondary violation, it was about three times more likely to be cleared by charge (95% compared with 33% when a secondary violation was not identified).

End of text box 2

Characteristics of online child pornography

Until now, the analysis has presented police-reported online abuse data wherein a victim had been identified. The following section will examine incidents of child pornography, wherein a victim had not been identified and, thus, information about victimized children was not known to the police.

There is a significant number of child pornography images on the Internet, and the number of reports of such child sexual abuse material continues to increase (Canadian Centre for Child Protection 2022a). As such, counts of police-reported child pornography incidents included in this article likely represent cases that have been actioned or opened by police in a given year, and not necessarily all cases that have come to their attention over this period.Note

Of note, the Criminal Code does not limit the definition of child pornography to instances where telecommunications or online means are used. However, given the online focus of this article, and to allow for comparisons to be drawn between offence types, only child pornography incidents where information and communication technology (ICT) was indicated are included. However, it is likely that a large share of police-reported child pornography incidents over the seven years included in this article were in fact cyber-related (see Text box 3).

Start of text box 3

Text box 3

Cybercrime as a percentage of all crime, 2018-2020

Prior to 2018, all cybercrime data collected through the Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR) Survey were kept in a separate database. However, in order to allow for a more comparative analysis between cybercrime data and non-cyber-related crime, beginning in 2018, cybercrime data were merged with all other UCR incident data. Due to this change and any differences in the data processing methodologies before and after the 2018 merge, analysis differentiating cybercrime from non-cybercrime incidents can only be conducted using data from 2018 onward.

Overall, 2% of all crimes reported to police between 2018 and 2020 were cybercrime. Two-thirds (68%) of cybercrime incidents did not involve violations against the person. In fact, more than half (54%) of cybercrime incidents are related to fraud.Note Violations against the person (also known as violent crime, and excludes child pornography offences) accounted for about one-third (32%) of cybercrime incidents reported during this time—most commonly harassment (14%), uttering threats (8%) or extortion (4%).Note

Child pornography represented 11% of all cybercrime incidents: 9% were making or distributing, and the remaining 2% were related to possessing or accessing child pornography.

Online sexual offences against children accounted for 4% of all cybercrime.Note In other words, over the three-year period, online child sexual offences accounted for about 0.1% of all police-reported incidents.

Notably, by their Criminal Code definitions, the two criminal offences of luring a child, and agreement or arrangement (sexual offence against a child) are characterized by the use of telecommunication in the committing of the offence and are thus assumed to have occurred online.

Further, nearly two-thirds (63%) of child pornography incidents reported between 2018 and 2020 were flagged as cybercrime. Lower proportions of incidents involving non-consensual distribution of intimate images (39%) and invitation to sexual touching offences (13%) were flagged as cybercrime.

For additional information on police-reported cybercrime, see Statistics Canada 2021.

End of text box 3

Child pornography represents more than two-thirds of all police-reported online child sexual exploitation and abuse incidents

Between 2014 and 2020, Canadian police reported a total of 29,028 incidents of online child pornography.Note This means, overall, in nearly three-quarters (73%) of all police-reported incidents of online child sexual exploitation and abuse, a victim was not identified.

This is not to imply that child pornography is a victimless crime. Rather, it simply means that the police were unable to identify the actual victims. Police can rely solely on the images they come across in which perpetrators can hide any identifying features of the victims, making it difficult for police or automated web crawlers (tools used to sift through the web detecting images) to make matches to victims. In police data, however as previously mentioned, child pornography was indicated as a secondary offence in 17% of online child sexual exploitation and abuse incidents where a victim had been identified. Additionally, victim accounts and testimony play an important role in the criminal justice process. For example, victims are often the main witnesses and assist in police investigations and the identification of perpetrators, and their assessment of the impact of the crime on their life carries weight on court decisions and outcomes for the accused (Cameron 2003; Department of Justice 2021; Haskell and Randall 2019). Further, children whose sexual abuse had been recorded (whether distributed or not) experience many negative outcomes including negative family life both as children and later on as adults, difficulties engaging in romantic or sexual relationships in adulthood, and negative economic outcomes in adulthood (Canadian Centre for Child Protection 2017).

While it cannot be measured through police-reported data, the nature of online sexual victimization is such that it perpetuates repeat victimization. Images of the same victim could be duplicated and shared many times, further victimizing the victim even after the contact aspect of the offence has ended.

Two-thirds of online child pornography incidents involve making or distributing

In the UCR, child pornography offences are grouped into two categories: child pornography (possessing or accessing) and child pornography (making or distributing).Note About one in three (32%) online child pornography incidents involved possessing or accessing child pornography, while two-thirds (68%) involved making or distributing child pornography.

Virtually all (99%) online child pornography incidents did not have a different secondary violation identified in the incident. Any secondary violations identified were in relation to making or distributing offences which were identified as the most serious violation in an incident and where the secondary violation was possessing or accessing child pornography.

Charges less common in incidents of online child pornography

There are a number of known factors which could impact whether or not charges are laid, including victim and accused characteristics such as gender or age, the nature of the relationship between the victim and the accused, and level of harm or injuries to the victim (Baiden et al. 2017; Dawson and Hotton 2014). Additionally, as noted, online sexual offences against children were more likely to result in charges when they involved multiple violations. However, the complexities and challenges of investigating online offences, and in particular child pornography, make it difficult to identify victims and locate offenders, subsequently affecting the charge rates for this crime.

The large majority (85%) of police-reported online child pornography incidents were not cleared. This means that, in addition to these incidents not having any victim information, no accused persons were identified. This could be in part due to the fact that even when an incident is reported to police, often anonymously, it is still difficult to locate or pinpoint the exact location of the accused. This is especially true when the child pornography was discovered in, or accessed using, a public or communal space or Internet Protocol (IP) address, and with an accused who may have changed locations. For the remaining incidents, 10% were cleared by charge and 5% were cleared otherwise, proportions much lower than incidents where the child victim was identified (32% and 11%, respectively). In other words, 64% of child pornography incidents that were cleared involved the laying or recommendation of charges, compared with 74% of incidents where a victim was identified.

Incidents involving the making or distributing of child pornography were less likely to be cleared (90% were not cleared, by charge or otherwise) and were slightly less likely to have charges laid even when an accused is identified (63%; Chart 6). In comparison, 65% of possessing or accessing child pornography incidents that were solved were cleared by charge and 35% were cleared otherwise.

Chart 6 start

Data table for Chart 6

| Type of offence | Not cleared | Cleared by chargeData table for Chart 6 Note 1 | Cleared otherwiseData table for Chart 6 Note 1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| percent | |||

| Possessing or accessing child pornography | 74 | 65 | 35 |

| Making or distributing child pornography | 90 | 63 | 37 |

Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics, Uniform Crime Reporting Survey. |

|||

Chart 6 end

Start of text box 4

Text box 4

Cybertip.ca

The Canadian Centre for Child Protection (C3P) is a national charity dedicated to the personal safety of all children. The organization’s goal is to reduce the sexual abuse and exploitation of children through programs, services, and resources for Canadian families, educators, child-serving organizations, law enforcement, and other parties. C3P also operates Cybertip.ca ® — Canada’s national tipline to report child sexual abuse and exploitation on the internet; and Project Arachnid ® — a web platform designed to detect known images of child sexual abuse material (CSAM) on the clear and dark web and issue removal notices to industry. Cybertip.ca has been operational since September 26, 2002, and was adopted under the Government of Canada’s National Strategy for the Protection of Children from Sexual Exploitation on the Internet in May 2004. In December 2011, C3P (through the Cybertip.ca program) was named within the regulations under Canada’s Act respecting the mandatory reporting of Internet child pornography by persons who provide an Internet service as the designated reporting entity under Section 2.

Reports to Cybertip.ca are submitted by the public relating to one of eight types of online crimes committed against children: CSAM; luring; non-consensual distribution of intimate images; making explicit material available for a child; agreement or arrangement with another person to commit a sexual offence against a child; commercial sexual exploitation of children; child trafficking and travelling to sexually exploit a child.

In 2020, there were 33,903 reports processed by Cybertip.ca.Note The vast majority (94%) of these reports were child pornography incidents. Non-consensual distribution of intimate images (3%) and luring (2%) accounted for about 5% of the incidents.Note

Just under half (49%) of these reports originated from an international jurisdiction.Note Among the remaining reports which originated in Canada, the most common reporting jurisdictions were Ontario (27% of all reports), Quebec (5%), British Columbia (4%) and Alberta (3%).

Among all reports received in 2020, 12% (or 4,135 reports) were forwarded to Canadian police or child welfare agencies. About seven in ten (71%) reports were forwarded to the Royal Canadian Mounted Police’s National Child Exploitation Crime Centre.Note Corresponding to the origin of the reports received, the remaining reports were forwarded to local jurisdictions, most commonly Ontario (11%), Quebec (5%), Alberta (4%) and British Columbia (4%).

Cybertip.ca data indicate that online child sexual exploitation and abuse is on the rise. The national tipline processed more than 4 million reports between 2014 and 2020. In 2021, Cybertip.ca saw a 37% increase over the previous year in the overall online victimization of children, 83% increase in reports of online luring, 38% increase in reports of non-consensual distribution of intimate images, 74% increase in reports of sextortion on online platforms often used by youth, and an increase in youth’s intimate images appearing on adult pornography sites and being shared on popular social media platforms (Canadian Centre for Child Protection 2022a).

Analysis presented in this text box are based on data published by Cybertip.ca (Canadian Centre for Child Protection 2022b).

For more information about Cybertip.ca visit: About Cybertip.ca

End of text box 4

Characteristics of people accused of online child sexual exploitation and abuse offences

Fewer accused persons identified in child pornography incidents

Between 2014 and 2020, police services across Canada identified 9,766 individuals as accused in incidents involving online child sexual exploitation and abuse.Note

While online child pornography incidents made up a larger share of incidents reported, fewer people were identified as accused in relation to these incidents. Specifically, 49% of persons accused in relation to online child sexual exploitation and abuse were accused of child pornography. In contrast, there were proportionally more people accused in incidents of child luring (32%), non-consensual distribution of intimate images (8%) and invitation to sexual touching (7%). An additional 4% were accused in other online-related sexual offences against children.

The median age of victims of online child sexual offences reported between 2014 and 2020 was 14 years for girls and boys. In contrast, accused persons in these types of crimes were generally older. The median age of an accused person in an online sexual offence against a child (excluding child pornography) was 23 years, and this nine-year difference between the median accused and victim age is attributable to the number of adult men accused in these incidents. Specifically, while victims are usually young girls, the vast majority (93%) of accused persons in incidents where victims were identified were men with a median age of 24 years, compared with a median age of 15 years among accused women and girls (Table 5).

These findings are consistent with previous research on police-reported sexual assaults (not necessarily cyber-related), which found that a large majority of incidents involving child victims were perpetrated by people who were ten or more years older than their victims, many of whom met the age-based criteria of clinical pedophilia (Rotenberg 2017).

Men accused in incidents involving invitation to sexual touching or other online sexual offences against children were generally much older than victims, with a median age of 28 and 35 years, respectively. While, overall, women accused were generally younger than the men accused, women involved in invitation to sexual touching or other online sexual offences against children were generally older (median age of 29 and 23, respectively, compared to victims of these crimes who had a median age of 13 and 15, respectively). In sum, regardless of the gender of the accused, incidents involving the invitation to sexual touching or other sexual offences against children are not often perpetrated by childhood peers, but rather by adults who are considerably older than victims.

While women and girls generally represented a small proportion (7%) of all accused in police-reported online child sexual offences where a victim was identified, they were overrepresented (23%) as persons accused in the non-consensual distribution of intimate images. Among both men and boys accused, and women and girls accused, youth between 12 and 17 years of age were responsible for the majority of the non-consensual distribution of intimate images incidents (89% and 94%, respectively). In other words, non-consensual distribution of intimate images often involved peers, with victims and accused persons having the same median age of 15, each.

Compared to online sexual offences against children, more women and girls accused in child pornography incidents, most often youth

Similar to online sexual offences against children, men and boys made up the large majority (89%) of persons accused in online child pornography incidents. However, there were more women and girls accused in child pornography incidents than online child sexual offences against children. Specifically, over one in ten people accused of possessing or accessing child pornography (11%) or making or distributing child pornography (12%) were women and girls, compared with 7% of persons accused in online child sexual offences against children (where a victim was identified).

The profile of women and girls accused in child pornography incidents mirrored that of women and girls accused in non-consensual distribution of intimate images. For example, the vast majority of women and girls accused in child pornography offences, whether possessing or accessing (82%) or making or distributing (72%), were aged 12 to 17. However, unlike men and boys accused in incidents of non-consensual distribution of intimate images who were also usually youth, child pornography offences less often involved boys aged 12 to 17 as the accused—the youth accused in these incidents represented about one-quarter (26%) of all men and boys accused.Note Instead, more than half of men and boys accused of possessing or accessing child pornography (53%) or making or distributing child pornography (56%) were aged 25 to 64. Overall, men accused of online child pornography incidents had a median age of 29.

Women more often accused with others, men generally acted alone

Persons accused in online child sexual exploitation and abuse between 2014 and 2020 were identified in connection with 8,768 incidents. Less than one in ten (7%) of these incidents where an accused had been identified involved multiple accused—that is, more than one person was involved as a suspect in the crime. About one out of six (16%) people accused were involved in an incident alongside at least one other accused person.

Accused women and girls were much more likely to be involved in online child sexual exploitation and abuse incidents where there were multiple accused, while men and boys generally were the only accused in these incidents. Specifically, more than half (56%) of women and girls accused were involved in multi-accused incidents compared to 13% of accused men and boys. This difference was observed across all offence categories included in online child sexual exploitation and abuse. However, the gap was smaller for people accused of non-consensual distribution of intimate images, with 64% of women and girls, and 47% of men and boys accused in these incidents being involved in multi-accused incidents.

Start of text box 5

Text box 5

Where are online child sexual exploitation and abuse incidents reported? A

focus on geography from 2018-2020

Unlike crimes that take place offline, which can generally be pinpointed to a particular physical location or vicinity, the borderless and spatially non-restrictive nature of online activities means that a victim of cybercrime might reside in one area, but the perpetrator can be anywhere. For example, according to a 2017 global report (UNICEF 2017), the vast majority of the world’s child sexual abuse websites are hosted in five countries, among which Canada is one.Note Therefore, understanding where victims are likely to be targeted and the physical location of where accused persons are identified, provide two different and important points of focus for people and organizations working to combat this crime in Canada and elsewhere. Therefore, this text box focuses on geography, presenting police-reported data related to where incidents involving identified victims and accused occur.

In Canada, local police services may deal with initial complaints or reports of online child sexual exploitation and abuse. However, the National Child Exploitation Coordination Centre (NCECC) is the Canadian body responsible for conducting investigations related to this crime, and is the point of contact for international agencies reporting child sexual exploitation materials which were uploaded in Canada. The NCECC is an extension of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) and provides services and support to Canadian and international police (Royal Canadian Mounted Police 2019).

Any geographical comparisons related to crime using police-reported data may be impacted by jurisdictional priorities, regional programs and policies, and reporting practices. Online child sexual exploitation and abuse incidents are likely among those more susceptible to these biases. For example, the presence or absence of designated Internet Child Exploitation Units or experts in investigating these types of crimes within a particular police service could impact the ability to identify victims or locate offenders. Additionally, as noted previously, reporting of child sexual abuse images by Internet Service Providers is mandatory in Canada. Therefore, locations where internet service providers reside or where technology hubs exist in Canada may influence the number of reports of online child pornography to particular police services. Further, reporting practices, for example whether the number of open or active investigations or total number of incidents are being reported, particularly for child pornography incidents—may impact the number of incidents reported to the Uniform Crime Reporting Survey (UCR).

Due to data coverage limitations affecting data collected prior to 2018, analysis based on geography are limited to data collected from 2018 to 2020 only (see Data sources).

More accused persons identified in the territories and Quebec relative to population

From 2018 to 2020, there were 5,761 police-reported incidents of online child sexual offences where a victim was identified, and approximately 4,800 people were identified as accused. These numbers represented an average annual rate of 27 incidents per 100,000 children and youth in Canada, and about 5 people accused for every 100,000 population aged 12 and over (Table 6).Note

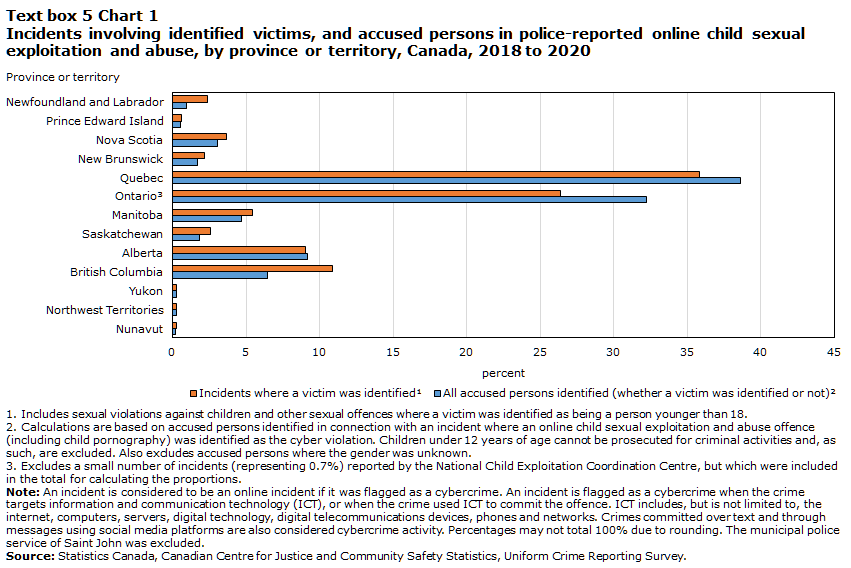

The largest proportion of persons accused of online child sexual exploitation and abuse (regardless of whether a victim was identified) was in Quebec (39%) followed by Ontario (32%) (Text box 5 Chart 1).Note When population size is taken into account, Quebec had a rate of 8 people accused per 100,000 population, the highest among the provinces, followed by Manitoba (7 per 100,000). While, combined, the territories represented less than 1% of all accused persons identified in police-reported online child sexual exploitation and abuse over the three years, the rates of accused in the territories were higher than the national average. The average annual rates of accused in the Yukon (12 per 100,000), Nunavut (12) and the Northwest Territories (11) were higher than the Canadian average (5).

Incident rates where a victim was identified were highest in the Yukon (57 incidents per 100,000 children and youth) and the Northwest Territories (53 per 100,000). Among the provinces, Newfoundland and Labrador reported the highest incident rate where a victim was identified (52 per 100,000 population).

Text box 5 Chart 1 start

Data table for Text box 5 Chart 1

| Province or territory | Incidents where a victim was identifiedData table for Text box 5 Chart 1 Note 1 | All accused persons identified (whether a victim was identified or not)Data table for Text box 5 Chart 1 Note 2 |

|---|---|---|

| percent | ||

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 2.4 | 1.0 |

| Prince Edward Island | 0.6 | 0.5 |

| Nova Scotia | 3.7 | 3.1 |

| New Brunswick | 2.2 | 1.7 |

| Quebec | 35.8 | 38.6 |

| OntarioData table for Text box 5 Chart 1 Note 3 | 26.4 | 32.3 |

| Manitoba | 5.4 | 4.7 |

| Saskatchewan | 2.6 | 1.8 |

| Alberta | 9.0 | 9.2 |

| British Columbia | 10.9 | 6.4 |

| Yukon | 0.2 | 0.3 |

| Northwest Territories | 0.3 | 0.3 |

| Nunavut | 0.3 | 0.2 |

Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics, Uniform Crime Reporting Survey. |

||

Text box 5 Chart 1 end

Child luring victims more commonly reported in Quebec, British Columbia and Manitoba

Across all provinces and territories, child luring offences accounted for the majority of the online sexual violations where a child was identified. However during the three years between 2018 and 2020, in some parts of Canada such as in Quebec (84%), Manitoba (82%) and British Columbia (82%), this crime accounted for larger proportions of the incidents reported. It is important to note that these are the regions where victims reported to police, though where the accused resided was usually unknown.

Overall, when it comes to incidents where a victim had not been identified (child pornography), British Columbia accounted for nearly half (49%) of the incidents reported over the three years, and the vast majority (93%) of all child sexual exploitation and abuse incidents reported by the province over this time. That is to say that police services in British Columbia were made aware of the existence of online child sexual exploitation which could have originated in any part of the world. Quebec (17%), Ontario (12%) and Alberta (7%) followed British Columbia in the proportion of child pornography incidents in Canada. However, as mentioned previously, police-reported child pornography incidents where a victim or accused had not been identified are particularly susceptible to reporting biases. Therefore, geographical analysis of these incidents do not necessarily reflect where these crimes are originating or where victims are, but may indicate differences in how police services are reporting these incidents to the UCR.

Additionally, it is important to reiterate that geographical differences seen may reflect the presence or absence of special programs or policies targeted at addressing this issue at the provincial or territorial level. For example, in Quebec, the Sûreté du Québec has had a provincial strategy since 2012. As part of the strategy, there are coordinated specialized units across the province dedicated to detecting and investigating cybercrime (for more information about the work of these specialized units see The Sûreté du Québec 2022). In British Columbia, some work was initiated by the British Columbia Behavioural Sciences Group – Integrated Child Exploitation Unit (BSG) using software developed by the Child Rescue Coalition to identify computers located in the province that were used to access or share child pornography on the Internet, from which they could open an investigation (for more information on the software see Child Rescue Coalition 2020). Such initiatives and policies may impact the number of these incidents reported in the regions implementing them.

End of text box 5

Court charges and outcomes of child sexual offences likely committed or facilitated online

The Integrated Criminal Court Survey (ICCS) collects statistical information on adult criminal and youth court cases involving Criminal Code and other federal statute offences.

Sections 172.1(1) (2) and 172.2(2) of the Criminal Code explicitly mention the use of telecommunications in its definitions of two offences relating to the sexual victimization of children: luring a child, and agreement or arrangement (sexual offence against a child). An analysis of court charges involving these offences are presented in this section, along with charges of other Criminal Code violations that have a higher chance of being committed or facilitated online, namely, child pornography and the non-consensual distribution of intimate images (based on what is shown in police-reported data; see Text box 3).Note In this section, combined, these offences are also referred to as online child sexual offences.

From April 2014 to March 2020, criminal courts in Canada processed 27,522 charges related to child sexual offences which were likely committed or facilitated online.Note These charges were processed as part of 9,138 completed cases which comprised 58,984 total charges.Note Based on the number of total charges and cases completed over these six years, adult cases averaged 6.8 charges per case, and youth cases had an average of 4.7 charges per case. More specifically, adult cases averaged 3.1 charges related to online child sexual offences compared with 2.6 such charges per case in youth courts.

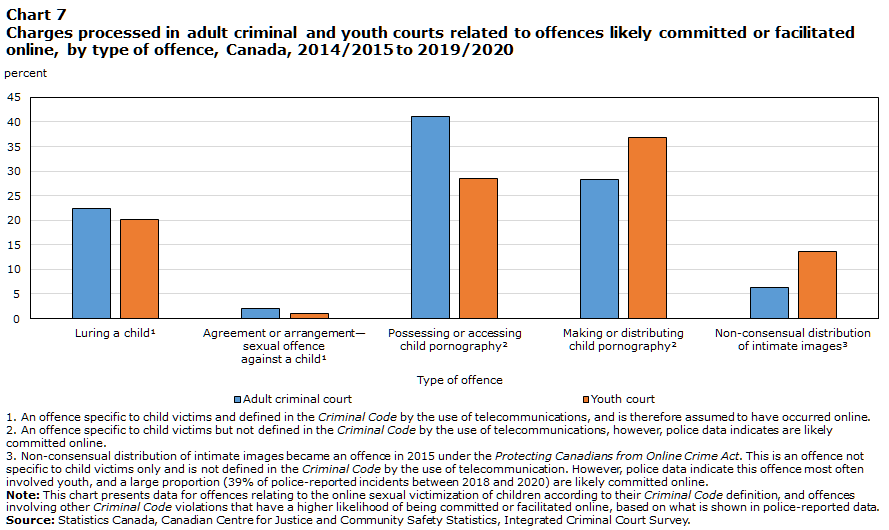

As seen with police-reported data, in both adult criminal and youth courts, child pornography which includes making or distributing, and possessing or accessing child pornography made up the largest proportion of online child sexual offence charges that were processed over the 6 years (69% of the adult charges and 65% of the youth charges). Overall, over eight out of every ten (85%) charges related to online child sexual offences were processed in adult courts. Charges of possessing or accessing child pornography were the most common type of charge related to child sexual offences likely committed online in adult courts (41% versus 29% in youth courts), while the most common type of charge processed in youth courts was related to the making or distribution of child pornography (37% versus 28%) (Chart 7).Note Consistent with incidents reported to police, youth courts also processed proportionally more charges related to the non-consensual distribution of intimate images than adult courts (14% compared to 6% of adult charges).

Chart 7 start

Data table for Chart 7

| Type of offence | Adult criminal court | Youth court |

|---|---|---|

| percent | ||

| Luring a childData table for Chart 7 Note 1 | 22 | 20 |

| Agreement or arrangement—sexual offence against a childData table for Chart 7 Note 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Possessing or accessing child pornographyData table for Chart 7 Note 2 | 41 | 29 |

| Making or distributing child pornographyData table for Chart 7 Note 2 | 28 | 37 |

| Non-consensual distribution of intimate imagesData table for Chart 7 Note 3 | 6 | 14 |

Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics, Integrated Criminal Court Survey. |

||

Chart 7 end

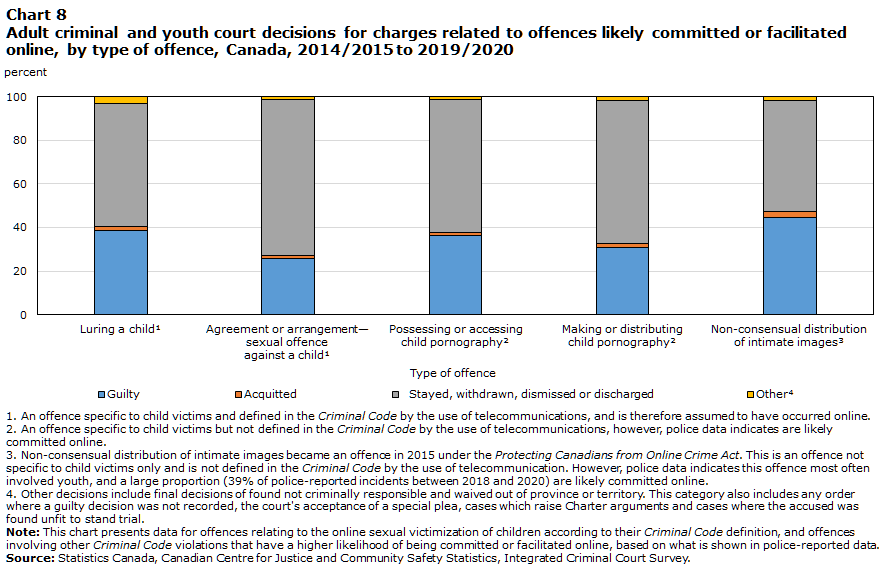

Between April 2014 and March 2020, less than four in ten (36%) charges laid for child sexual offences likely committed online resulted in a guilty finding. About six in ten (61%) of these charges were stayed, withdrawn, dismissed or discharged. Further, 2% of child sexual offence charges likely committed online were acquitted.Note Charges related to child sexual offences likely committed online were more likely to result in a guilty decision than charges involving other sexual violations against children—which were likely committed offline: 29% of these charges resulted in a guilty finding, 62% were stayed, withdrawn, dismissed or discharged, and the accused was acquitted for 7% of the charges.Note

Proving sexual crimes in court is a challenge that has been well documented (Dodge 2018; Randall 2010; Sheehy 1999). However, the higher prevalence of charges related to sexual offences committed online resulting in a guilty decision may indicate that, when brought to court, these crimes are easier to prove than other types of sexual crimes. The presence of physical evidence, or traceable online prints or records may contribute to the court outcomes observed.

Charges of non-consensual distribution of intimate images most likely to result in a finding of guilt

Perpetrators were most commonly found guilty of charges related to non-consensual distribution of intimate images (45%), followed by child luring charges (38%) (Chart 8). Agreement or arrangement (sexual offence against a child) charges were least likely among these offence types to result in a finding of guilt (26%)—the majority of these charges were stayed, withdrawn, dismissed or discharged (72%).

Chart 8 start

Data table for Chart 8

| Type of offence | Guilty | Acquitted | Stayed, withdrawn, dismissed or discharged | OtherData table for Chart 8 Note 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| percent | ||||

| Luring a childData table for Chart 8 Note 1 | 38 | 2 | 56 | 3 |

| Agreement or arrangement—sexual offence against a childData table for Chart 8 Note 1 | 26 | 1 | 72 | 1 |

| Possessing or accessing child pornographyData table for Chart 8 Note 2 | 36 | 1 | 61 | 1 |

| Making or distributing child pornographyData table for Chart 8 Note 2 | 31 | 2 | 66 | 2 |

| Non-consensual distribution of intimate imagesData table for Chart 8 Note 3 | 45 | 3 | 51 | 2 |

Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics, Integrated Criminal Court Survey. |

||||

Chart 8 end

Guilty finding related to online child sexual offence charges more common in youth courts

Online child sexual offence charges processed in youth courts were more likely to result in a guilty decision than the same type of charges processed in adult courts. Overall, 45% of charges processed in youth courts related to child sexual offences likely committed online resulted in a guilty finding for the charge, compared with about one-third (34%) of charges processed in adult courts (Table 7). This difference was largely driven by a greater number of charges related to child luring, and agreement or arrangement (sexual offences against a child) resulting in a finding of guilt in youth courts than adult courts. More than half (56%) of child luring charges and nearly as many (45%) agreement or arrangement charges processed in youth courts resulted in a guilty decision, compared with 36% and 24% in adult courts, respectively. In adult courts, these charges were more likely to have been stayed, withdrawn, dismissed or discharged.

These findings were also reflected when considering decisions rendered for child-specific sexual offence charges that were likely committed offline. Just under four in ten (39%) child sexual offence charges for crimes likely committed offline that were processed in youth courts between April 2014 and March 2020 resulted in a guilty finding, and 52% were stayed, withdrawn, dismissed or discharged. In comparison, 26% of those processed in adult courts resulted in a guilty finding, and 65% were stayed, withdrawn, dismissed or discharged.

These findings may be partly attributable to cases processed in adult courts being more likely to include more charges as part of a case, giving prosecutors more opportunities to prove guilt or the accused accepting a guilty plea related to other charges within the case, and charges related to online child sexual offences getting dropped (Sheehy 2012; Spohn 2001). A case can have more than one charge, which may include multiple charges for the same offence or other related charges. Further, these charges are not mutually exclusive and, as such, a case can also involve multiple types of child sexual offence charges.

While a finding of guilt for charges related to online child sexual offences were more common in youth courts, among online child sexual offence charges processed in adult courts, the proportion of charges resulting in a finding of guilty varied by type of offence. For example, a guilty finding for charges related to non-consensual distribution of intimate images was most common among younger adults aged 18 to 24, and appeared to decrease with age. Conversely, a guilty decision related to possessing or accessing child pornography charges appeared to increase with age, with people aged 55 and over being most likely to be found guilty.

Higher proportion of cases involving child sexual offences likely committed online result in guilty decision compared to cases with other sexual offences

In more than six in ten (61%) completed cases with at least one charge related to online child sexual offences, the most serious decision for any of these offences was guilty.Note In comparison, 41% of cases with at least one charge of child sexual offences likely committed offline resulted in a finding of guilt for any of those charges. Cases involving offline child sexual offence charges were more likely to result in other types of decisions as the most serious decisions for those charges including stayed, withdrawn, dismissed or discharges (49% versus 35% of online cases), acquitted (8% versus 3%) or other decisions (2% versus 1%).

Slightly fewer women are found guilty of online child sexual offence charges