Gender-related homicide of women and girls in Canada

by Danielle Sutton

Highlights

- For the purposes of this Juristat, gender-related homicides of women and girls are solved homicides committed by a male accused who: (a) was an intimate partner or family member of the victim, (b) inflicted sexual violence on the victim as part of the killing or (c) killed a victim who was identified as a sex worker.

- Between 2011 and 2021, police reported 1,125 gender-related homicides of women and girls in Canada. Of these homicides, two-thirds (66%) were perpetrated by an intimate partner, 28% a family member, 5% a friend or acquaintance and the remaining 1% a stranger.

- While the rate of gender-related homicide of women and girls has generally declined since 2001, there was a 14% increase between 2020 and 2021 (from 0.48 to 0.54 victims per 100,000 women and girls), marking the highest rate recorded since 2017.

- In 2021, the territories recorded the highest rate of gender-related homicide of women and girls (3.20 per 100,000 women and girls) and, for the provinces, the highest rate was in Saskatchewan (1.03), followed by Manitoba (0.72) and Alberta (0.68).

- In 2021, the rate of gender-related homicide in Canada was more than 2.5 times greater in rural areas compared to urban areas (1.13 versus 0.44 per 100,000 women and girls).

- Between 2011 and 2021, of all gender-related homicides of women and girls, the largest proportion died by stabbing (34%). About four times as many victims of gender-related homicide died of strangulation, smothering or drowning (17%) compared to victims of non-gender-related homicides (4%).

- One-third (32%) of gender-related homicides of women and girls were reported by police as motivated primarily by the accused’s anger, frustration or despair, almost triple the proportion found among non-gender-related homicides (12%).

- Over the 11-year period (i.e., 2011 to 2021), one in five (21%) persons accused of a gender-related homicide where at least one woman or girl was killed resulted in the suicide of the accused, seven times higher than what was found among persons accused of committing a non-gender-related homicide (3%).

- Data between 2011 and 2021 show that of all gender-related homicides of women and girls, 21% (n=233) of victims were Indigenous, despite comprising only 5% of the female population in Canada in 2021.

- In 2021, the rate of gender-related homicide of Indigenous victims was more than triple that of gender-related homicides of women and girls overall (1.72 versus 0.54 per 100,000 women and girls).

- Data between 2011 and 2021 show that compared to the gender-related homicide of women and girls overall, when the victim was Indigenous a larger proportion were younger and died by beating.

- In 2021, there was a rate of 0.27 gender-related attempted murders per 100,000 women and girls in Canada.

- The rate of gender-related attempted murder of women and girls has been on the decline since 2017, except for 2019 where the rate increased from 0.29 victims in 2018 to 0.41 victims per 100,000 women and girls.

- Between 2011 and 2021, the largest proportion of gender-related attempted murders of women and girls occurred at residential locations, involved the presence of a weapon and resulted in physical injury.

Although most homicide victims are men and boys, women and girls are disproportionately killed by someone they know, namely an intimate partner or a family member (David & Jaffray, 2022; Dawson et al., 2021; UNODC, 2022a; UNODC, 2018).Note Globally, it is estimated that nearly six in ten (56%) homicides involving a woman or girl were perpetrated by an intimate partner or a family member in 2021 (UNODC, 2022a). In Canada, of solved homicides that occurred in 2021, almost three quarters (72%) of women and girls were killed by an intimate partner or a family member (David & Jaffray, 2022). In comparison, men are most often killed by someone with whom they share a more distant relationship (e.g., an acquaintance, friend, stranger) (Sutton, 2023).

While previous studies have examined trends and characteristics of homicide victims in Canada (Armstrong & Jaffray, 2021; David & Jaffray, 2022), less is known about a subset of victims—those whose death was gender-related. Gender-related homicide of women and girls is broadly defined as the killing of women and girls because of their gender or killings that affect them disproportionately (ACUNS, 2017; UNODC, 2022b).Note Examples include, but are not limited to, the homicide of women and girls by an intimate partner or family member, the killing of women who worked in the sex trade, experienced sexual violence, had a history of violent victimization by the perpetrator or whose body was disposed of publicly (UNODC, 2022b). Some researchers argue that these killings occur due to the existence of gender norms and stereotypes, discrimination directed toward women and girls, and unequal power relations across genders within society and the family (Sarmiento et al., 2014; UNODC, 2022b; UNODC, 2018).

Current data available in Canada do not allow for an analysis of the underlying sociocultural or systemic factors and are instead limited to individual and incident characteristics. Such data limitations are not unique to Canada. For example, the only criterion used by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (2022a; 2018) to identify gender-related homicides of women and girls is when they are perpetrated by an intimate partner or family member because this information is collected more often than other contextual factors, thereby yielding comparable data across countries.Note This approach, however, has been critiqued for its simplicity. Gender-related killings are a complex phenomenon that is difficult to conceptualize with only a couple of core determinants (i.e., gender and relationship) (Dawson & Carrigan, 2021).

Building on this criticism, for the purposes of this Juristat, gender-related homicides of women and girls are defined as homicides perpetrated by a male accused who: (a) was an intimate partner or family member,Note (b) inflicted sexual violence on the victim as part of the homicide,Note or (c) killed a woman or girl who was identified as a sex worker. To be considered gender-related, the homicide must have been perpetrated by a male accused,Note and applies to solved (i.e., cleared) homicides only.Note The additional qualifiers of women who experienced sexual violence as part of the killing or who were identified as sex workers are factors known to disproportionately affect women and girls and can be seen as evidence of how attitudes of male dominance may be relevant in some homicide cases (UNODC, 2018).

This Juristat draws on data from Statistics Canada’s Homicide Survey to explore trends and characteristics of gender-related homicides of women and girls over time and across location to enhance public understanding of gender-related killings. The current study pools eleven years of police-reported data to present information on victim, accused and incident characteristics of gender-related homicides overall, as well as those with Indigenous women and girls as victims.Note These data provide an important overview of recent trends in gender-related homicides of women and girls in Canada. The final section relies on data from the Incident-based Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR) Survey to present an analysis of gender-related attempted murders of women and girls.

This article was produced with funding support from Women and Gender Equality Canada.

Section 1: Gender-related homicide of women and girls

Between 2011 and 2021, police reported 1,847 women and girls who died by homicide in Canada.Note Of these homicides, one in ten (10%; n=191) were not cleared, meaning the homicide was still under investigation or there was insufficient evidence to proceed. Focusing on cleared (i.e., solved) homicides of women and girls, almost nine in ten (88%) involved a male accused, while 12% were perpetrated by a female accused (see Text box 2).

Of the cleared homicides of women and girls involving a male accused, more than three-quarters (77%) may be classified as being gender-related; that is, homicides committed by an intimate partner or a family member, involved victims who had experienced sexual violence as part of the killing or who were identified as sex workers. In total then, between 2011 and 2021, 1,125 women and girls were victims of gender-related homicide in Canada, which averages to about 102 women and girls per year.

Among the gender-related homicides of women and girls that occurred during the 11-year period, 93% (N=1,051) were committed by a male family member or intimate partner, 6% (N=67) involved a victim who was a sex worker,Note and 4% (N=49) involved evidence of sexual violence.Note

The primary aim of this section is to examine the gender-related homicide of women and girls, providing information on victim, accused and incident characteristics using data from the Homicide Survey. Non-gender-related homicides—defined as all homicides of men and boys as well as the homicides of women and girls that were: (a) unsolved,Note (b) committed by a female accused and (c) those without the documentation of at least one characteristic used to identify gender-related homicides—will be used as a point of comparison. The analysis excludes homicides where the victim or accused person’s gender was unknown.Note In 2019, the Homicide Survey began collecting data on the racialized group identity of victims and accused. Given this short timeframe, these data are unavailable for most years examined and are therefore not included in the analysis.

Recent increase in gender-related homicide of women and girls

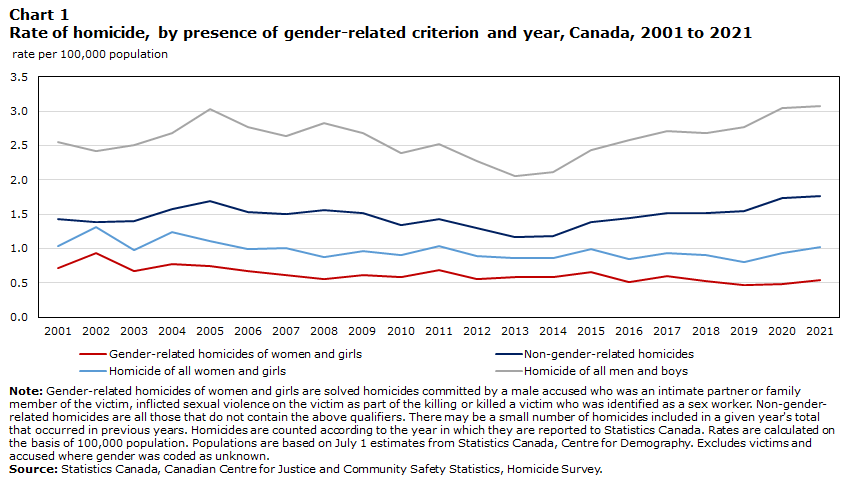

Since 2001, there have been minor year-to-year fluctuations in the rate of gender-related homicides of women and girls in Canada (Chart 1). Over the past two decades, the rate was highest in 2002 (0.93 victims per 100,000 women and girls) and lowest in 2019 (0.47). While the rate of gender-related homicide of women and girls has generally declined over time, it increased 14% between 2020 and 2021 (from 0.48 to 0.54 victims per 100,000 women and girls), marking the highest documented rate since 2017. In contrast, the overall rate of non-gender-related homicide has shown year-over-year increases since 2013 from 1.16 to 1.77 victims per 100,000 population, representing a 53% increase over the nine-year period.Note These patterns resemble larger trends in homicide rates documented across genders. Specifically, between 2020 and 2021, a similar, albeit smaller rate increase was documented for the homicide of all women and girls (+10%). Likewise, for men and boys, there was a 49% increase in the homicide rate since 2013, from 2.06 to 3.07 victims per 100,000 population.

Chart 1 start

Data table for Chart 1

| Year | Gender-related homicides of women and girls | Non-gender-related homicides | Homicide of all women and girls | Homicide of all men and boys |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| rate per 100,00 population | ||||

| 2001 | 0.72 | 1.42 | 1.03 | 2.54 |

| 2002 | 0.93 | 1.39 | 1.31 | 2.41 |

| 2003 | 0.68 | 1.40 | 0.98 | 2.51 |

| 2004 | 0.77 | 1.57 | 1.24 | 2.69 |

| 2005 | 0.74 | 1.69 | 1.11 | 3.03 |

| 2006 | 0.67 | 1.53 | 0.99 | 2.76 |

| 2007 | 0.61 | 1.51 | 1.00 | 2.64 |

| 2008 | 0.56 | 1.56 | 0.88 | 2.83 |

| 2009 | 0.61 | 1.51 | 0.96 | 2.69 |

| 2010 | 0.58 | 1.34 | 0.90 | 2.39 |

| 2011 | 0.69 | 1.42 | 1.04 | 2.52 |

| 2012 | 0.55 | 1.30 | 0.90 | 2.28 |

| 2013 | 0.58 | 1.16 | 0.85 | 2.06 |

| 2014 | 0.58 | 1.19 | 0.86 | 2.11 |

| 2015 | 0.66 | 1.38 | 0.99 | 2.44 |

| 2016 | 0.51 | 1.45 | 0.85 | 2.57 |

| 2017 | 0.59 | 1.52 | 0.94 | 2.71 |

| 2018 | 0.53 | 1.52 | 0.90 | 2.68 |

| 2019 | 0.47 | 1.55 | 0.81 | 2.77 |

| 2020 | 0.48 | 1.74 | 0.93 | 3.04 |

| 2021 | 0.54 | 1.77 | 1.02 | 3.07 |

|

Note: Gender-related homicides of women and girls are solved homicides committed by a male accused who was an intimate partner or family member of the victim, inflicted sexual violence on the victim as part of the killing or killed a victim who was identified as a sex worker. Non-gender-related homicides are all those that do not contain the above qualifiers. There may be a small number of homicides included in a given year's total that occurred in previous years. Homicides are counted according to the year in which they are reported to Statistics Canada. Rates are calculated on the basis of 100,000 population. Populations are based on July 1 estimates from Statistics Canada, Centre for Demography. Excludes victims and accused where gender was coded as unknown. Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics, Homicide Survey. |

||||

Chart 1 end

The recent increase in the rate of gender-related homicide of women and girls could be a product of random fluctuations. Alternatively, it may be that the COVID-19 pandemic with its corresponding lockdown measures exacerbated the stressors and violence some were already experiencing while simultaneously limiting access to services, shelters and supports (Gadermann et al., 2021; Piquero et al., 2021). Lending support to the latter, recent Canadian data note that about half of residential shelters for victims of abuse documented an increase in the number of crisis calls at during the pandemic, while simultaneously reporting their accommodation capacity was impacted to a great extent due in part to physical distancing measures, staff shortages and high turnover (Ibrahim, 2022; Moffitt et al., 2020; Nelson et al., 2022; Sánchez et al., 2020).

The territories and Prairie provinces report the highest rate of gender-related homicide of women and girls

In 2021, there were 104 gender-related homicides of women and girls in Canada, representing a rate of 0.54 homicides per 100,000 women and girls (Table 1). Despite small counts in comparison to the provinces, the highest rate was reported in the territories (3.20 per 100,000 population), which is due to the population size being small relative to the provinces. For the provinces, the highest rate of gender-related homicide of women and girls was reported in Saskatchewan (1.03),Note followed by Manitoba (0.72) and Alberta (0.68) – all of which were above the national rate. Of note, these provinces also recorded the highest provincial rates of homicide and overall violent crime in 2021 (David & Jaffray, 2022; Moreau, 2022).

Aligned with previous research noting higher rates of violence in rural compared to urban areas (David & Jaffray, 2022; Gillespie & Reckdenwald, 2017; Perreault, 2023), in 2021, the rate of gender-related homicide of women and girls in Canada was more than 2.5 times greater in rural areas compared to urban areas (1.13 versus 0.44 per 100,000 population).Note In fact, the rate of gender-related homicide of women and girls was higher in all provincial and territorial rural areas than what was documented in urban parts of Canada. Among the provinces, the largest differences were noted in Manitoba, where the gender-related homicide rate was 10 times higher in rural compared to urban areas (2.0 versus 0.20) and in Saskatchewan, where the rate was nearly four times higher in rural compared to urban areas of the province (2.03 versus 0.52).

Recent research has sought to explain the heightened risk of fatal and non-fatal intimate partner violence in rural locations and has pointed to factors such as geographic isolation, socioeconomic disadvantage, rural culture (e.g., firearm acceptance, patriarchal values), limited anonymity or confidentiality, a lack of public transportation and sparsely distributed emergency services as contributors (Dawson et al. 2019b; Dawson et al., 2021; DeKeseredy, 2020; Gillespie & Reckdenwald, 2017; Youngson et al., 2021). Not only are these factors potential contributors to violence, they can also impede help-seeking and medical treatment if violence occurs (Youngson et al., 2021).

Two-thirds of gender-related homicides of women and girls involve an intimate partner as the accused

Not surprisingly given the definition of gender-related homicide used in this article, between 2011 and 2021, two-thirds (66%) of all women and girls who were victims of gender-related homicide were killed by an intimate partner (Table 2). Of these victims, the largest proportion were killed by their legally married spouse (30%), followed by a common-law partner (28%) and a non-spousal intimate partner (26%).Note The remaining 15% were killed by a former legal spouse or common-law partner.Note These figures support past research which found a greater proportion of intimate partner homicides occur between current rather than former partners (Dawson et al., 2021; Reckdenwald et al., 2019). However, a woman or girl leaving a relationship—or expressing the desire to do so—has been shown to be a frequent precursor to intimate partner homicide (Beyer et al., 2013; Johnson et al., 2019; Sarmiento et al., 2014). The Homicide Survey, however, does not currently capture information on separation or the potential of separation as a contributing factor to intimate partner homicides.

More than one in four gender-related homicides of women and girls were perpetrated by a non-spousal family member

According to police-reported data, between 2011 and 2021, more than a quarter (28%) of gender-related homicides of women and girls were perpetrated by a non-spousal family member. Of these, 49% were committed by the victim’s child (i.e., son) and these victims were often older; six in ten (62%) were aged 55 and older. Another 24% of gender-related homicides were perpetrated by the victim’s parent (i.e., father or stepfather) with the majority (71%) of victims aged 11 and younger. In the latter killings, three quarters (74%) were perpetrated by the victim’s biological parent and 26% by a stepparent.Note Of the remaining gender-related familial homicides, 20% were perpetrated by an extended family member and 6% by a sibling.Note

Of gender-related homicides of women and girls involving a family member or intimate partner, nearly half (48%) involved a history of family or intimate partner violence, which is one of the most commonly documented risk factors for intimate partner homicide (Campbell et al., 2009; Cullen et al., 2019; Johnson et al., 2019).Note While these data are crucial for identifying who is most at risk, this information was available for 68% of victims and may be further limited by underreporting practices. Moreover, the direction of the pre-existing violence is not captured in the Homicide Survey (i.e., whether it was perpetrated by the accused against the victim or vice versa).

Six in ten gender-related homicides of women and girls involve victims aged 35 years and older

When examining homicides by victim age group, some differences were documented between gender-related homicides of women and girls compared to their non-gender-related counterparts. Between 2011 and 2021, and aligned with the high proportions of women killed by their spouse or child, nearly six in ten (59%) victims of gender-related homicide were aged 35 and older (Chart 2). This proportion is also representative of their makeup in the general population; in 2021, 60% of the female population in Canada was aged 35 and older (Statistics Canada, 2023). However, Canadian research has also shown that younger women (i.e., aged 15 to 24) are more likely to self-report prior experiences with intimate and non-intimate partner violence than their older counterparts (Cotter, 2021; Savage, 2021). With respect to intimate partner violence, younger women are also more likely to report having separated from their abuser than older women (Savage, 2021). Because prior violence is a known risk factor for intimate partner homicide, the high proportion of gender-related homicide victims aged 35 and older could be explained, in part, by ongoing violence that culminated in death.

Chart 2 start

Data table for Chart 2

| Age group (years) | Gender-related homicides of women and girls | Non-gender-related homicides |

|---|---|---|

| percentage | ||

| 11 and younger | 5.8 | 4.0 |

| 12 to 17 | 3.5 | 3.8 |

| 18 to 24 | 11.9 | 19.5 |

| 25 to 29 | 10.1 | 14.8 |

| 30 to 34 | 9.4 | 11.3 |

| 35 to 39 | 9.9 | 9.1 |

| 40 to 44 | 8.3 | 7.7 |

| 45 to 49 | 7.5 | 7.2 |

| 50 to 54 | 7.7 | 6.2 |

| 55 to 59 | 7.2 | 5.3 |

| 60 to 64 | 6.6 | 3.7 |

| 65 to 69 | 3.6 | 2.2 |

| 70 and older | 8.6 | 5.2 |

|

Note: Gender-related homicides of women and girls are solved homicides committed by a male accused who was an intimate partner or family member of the victim, inflicted sexual violence on the victim as part of the killing or killed a victim who was identified as a sex worker. Non-gender-related homicides are all those that do not contain the above qualifiers. There may be a small number of homicides included in a given year's total that occurred in previous years. Homicides are counted according to the year in which they are reported to Statistics Canada. Excludes victims where gender or age was coded as unknown. Excludes accused where gender was coded as unknown. Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics, Homicide Survey. |

||

Chart 2 end

While the rate of homicide of senior women (i.e., those aged 65 and older) has declined 18% since 2010 (Conroy & Sutton, 2022), about one in eight (12%) gender-related homicides involved a senior woman.Note In comparison, 7% of non-gender-related homicides involved a victim aged 65 and older. Prior research has noted how senior women are most often killed by an intimate partner or family member (Allen et al., 2020; Bows, 2019; Conroy & Sutton, 2022; Sutton & Dawson, 2017). With a rapidly aging senior population in Canada, these findings could signal a need for additional supports and improved practices for identifying signs of violence among senior women.

In contrast, more than half (53%) the victims of non-gender-related homicides were aged 34 and younger, with the largest proportion aged 18 to 24 (19%), despite this age group representing 9% of the total population in 2021 (Statistics Canada, 2023).

Nearly nine in ten gender-related homicides of women and girls occur at a residence

Reinforcing previous claims of the home being the most dangerous place for women (Beyer et al., 2013; Dawson et al., 2021), since 2011 almost nine in ten (87%) gender-related homicides of women and girls occurred at a residence (Table 3).Note This compares with just under six in ten (56%) non-gender-related homicides, larger proportions of which occurred in open areas (32% versus 9%) or other locations like restaurants or bars (12% versus 4%).

Stabbing most common method in the gender-related homicide of women and girls

Over the 11-year period (i.e., 2011 to 2021), of all gender-related homicides of women and girls, one-third (34%) of the victims died by stabbing, nearly one-quarter (23%) by shooting and one-fifth (21%) by beating (Table 3). About four times as many victims of gender-related homicide of women and girls died of strangulation, smothering or drowning compared to victims of non-gender-related homicide (17% versus 4%), who most commonly died by shooting (38%).

However, a different pattern emerges when the method used to cause death is examined according to urban and rural locations. Specifically, in urban areas, of the gender-related homicides of women and girls, the largest proportion of victims died by stabbing (39%), followed by beating (19%) or strangulation (19%) and 18% died by firearm. In contrast, when such homicides occur in rural areas, most victims died by firearm (33%), followed by beating (25%) and stabbing (22%).Note For non-gender-related homicide victims, shooting was the most common method used to cause death in urban areas (40%), whereas stabbing (36%) was the most common method in rural areas.

One-third of gender-related homicides of women and girls are motivated by anger, frustration or despair

Tracking and understanding the primary motive behind gender-related homicides is important as it is often used to inform definitions of what constitutes these killings, while helping to understand risk factors and develop prevention programs. Reporting on this information is not intended to place blame on the victim, but rather to provide context and show how gender-related homicides of women and girls differ from other homicides. The data provided here reflect the primary apparent motive most relevant to the homicide incident as determined by the police investigation and may not coincide with motives presented later in the criminal justice process.Note

When the primary homicide motive was known (93% of victims), police reported one-third (32%) of gender-related homicides of women and girls were motivated by the accused’s anger, frustration or despair, almost triple the proportion found among non-gender-related homicides (12%) (Table 3). An additional 30% of gender-related homicides were reported to have been motivated by an argument or quarrel between the victim and accused, a slightly smaller proportion than what was documented for non-gender related killings (34%). Finally, one in seven (14%) gender-related killings of women and girls were motivated by jealousy or envy, a motive four times more common than what was documented for non-gender-related killings (3%). These differences may result from the close relationships often shared between victims and accused in gender-related homicides of women and girls such that these “emotional” motives are perceived by police to play a role and recorded at a higher frequency compared to non-gender-related homicides.

While the motive in any individual homicide does not determine or reveal its gender-related context, looking at the broader patterns in motivations and how they differ from non-gender related homicides can point to other, potentially systemic, issues that contribute to gender-related homicides, including but not limited to the accused’s loss of control, possessiveness, misogynistic attitudes or a victim’s attempt to leave the relationship.

Start of text box 1

Text box 1

Femicide and gender-related motives and indicators

The term “femicide”—broadly understood as the intentional killing of women because they are women (World Health Organization, 2012)—is growing in use both nationally and internationally within research fields, politics, the media and law enforcement. Its origin can be traced to the work of feminist pioneer Diana Russell who first used the term in 1976 as an alternate to the gender-neutral term “homicide” (Sarmiento et al., 2014). Its definition evolved over time, initially as “the murder of women by men motivated by hatred, contempt, pleasure, or a sense of ownership of women” (Caputi & Russell, 1990, p. 34).

Nevertheless, there is no agreed upon definition of femicide in a global or national context (UNODC, 2018). Rather, definitions vary in their scope, content and implications according to the perspective from which the phenomenon is studied and the discipline measuring it (Sarmiento et al., 2014). In response, efforts have been made to standardize the identification of femicides through the presence of at least one sex or gender-related motive or indicator (SGRMI) (Dawson & Carrigan, 2021; Sarmiento et al., 2014; UNODC, 2022b). Originating from the Latin American Model Protocol for the Investigation of Gender-Related Killings of Women (Femicide/Feminicide), SGRMIs are not understood as motives in the traditional sense (i.e., in police investigations or court processes), but are contextual factors rooted in misogyny and are meant to differentiate femicides from the homicide of men and the non-gender-related killing of women and girls (Dawson & Carrigan, 2021; Dawson et al., 2021; Sarmiento et al., 2014). Examples of SGRMIs include a history of violence between the victim and accused; the use of excessive force; degradation or public disposal of human remains; sexual violence and enforced disappearances (Dawson & Carrigan, 2021; Dawson et al., 2021; Sarmiento et al., 2014).

The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (2022b) has recently developed a statistical framework, listing gender-related motivations in attempt to standardize the collection of femicide data across communities, regions and countries.Note The statistical framework adopts a tiered approach whereby all intentional killings of women and girls committed by current or former intimate partners and family members are included, regardless of the accused gender. Next, intentional killings involving known or unknown accused are included if they have one or more of the following eight gender-related characteristics:

- the homicide victim had a previous record of physical, sexual, or psychological violence/harassment perpetrated by the author of the killing;

- the homicide victim was a victim of illegal exploitation, for example, in relation to trafficking in persons, forced labour or slavery;

- the homicide victim was in a situation where she was abducted or illegally deprived of her liberty;

- the victim was working in the sex industry;

- sexual violence against the victim was committed before and/or after the killing;

- the killing was accompanied by mutilation of the body of the victim;

- the body of the victim was disposed of in a public space;

- the killing of the woman or girl constituted a gender-based hate crime, i.e. she was targeted because of a specific bias against women on the part of the perpetrator(s).

While Statistics Canada’s Homicide Survey does not currently capture data on femicide or record information on all the above factors, some variables and indicators that are commonly used to operationalize this concept are collected. Moreover, police are also able to provide additional information in short written narratives which are captured along with the Homicide Survey. In future analysis, these narratives of female victims will be reviewed and the information collected can be used to allow for better identification of gender-related homicides.

End of text box 1

Fewer persons accused of committing a gender-related homicide of women and girls had a criminal history, compared to those accused of non-gender-related homicides

Between 2011 and 2021, police reported 1,077 distinct persons accused of committing a homicide involving at least one female victim whose homicide could be classified as gender-related. Nearly all gender-related homicides involved a single accused, whereas 3% (n=33) of these homicides involved multiple accused.Note Based on the qualifying criteria of what constitutes a gender-related homicide, all persons accused in these incidents were male, whereas for non-gender-related homicides the vast majority of accused persons were men (86%) and 14% were women (Table 4).

Of the 1,077 persons accused of perpetrating a gender-related homicide of women and girls, just under half (48%) had a criminal history known to police, most of which involved violence (33%). These proportions are lower than what was observed among persons accused of non-gender-related homicides, where a much higher proportion (65%) of accused had a criminal history, most often involving violent crimes (46%). These differences may have more to do with reporting and recording practices than true offending patterns; a history of violence is a common precursor to the gender-related killing of women and girls, but Canadian data have shown that intimate partner violence and sexual assault often go unreported (Conroy, 2021; Cotter, 2021).

Based on the information available (for 89% of accused), about one-third (32%) of persons accused of gender-related homicides of women and girls had a suspected or known mental or developmental disorder, compared to one in five (19%) persons who were accused of a non-gender-related homicide. It is important to note that this information is based on the investigating officer’s assessment of the accused at the time of the incident and is not a medical diagnosis. As a result, it is unknown whether the mental or developmental disorder was suspected or confirmed or whether it was necessarily relevant to the homicide incident.

One in five persons accused of committing gender-related homicide of women and girls died by suicide

Of the 1,077 persons accused of perpetrating a gender-related homicide involving at least one female victim, one in five (21%) died by suicide (Table 4).Note In comparison, 3% of the 3,868 persons accused of committing a non-gender-related homicide died by suicide. These findings are aligned with prior research noting how murder-suicide occurs more often within the context of intimate or domestic relationships compared to other relationship types (Brennan & Boyce, 2013; Kivisto, 2015).

Among cleared homicides excluding those where the accused died by suicide, equal proportions of persons accused of gender-related and non-gender-related homicides were cleared by the recommendation or laying of charges (98%). Of this group, similar proportions of persons accused of gender-related and non-gender-related homicides had a second degree charge laid or recommended (53% and 55%, respectively). First degree murder charges were more commonly laid or recommended for persons accused of gender-related homicides (38% versus 28%) whereas manslaughter charges were laid or recommended more often for persons accused of non-gender-related homicides (17% versus 9%).

Start of text box 2

Text box 2

Homicides of women and girls by a female accused

Traditionally, the study of gender-related killings of women and girls has either focused on all homicides involving a female victim, or on a subset involving those killed by intimate partners, which typically involve a male accused (Dawson & Carrigan, 2021). By contrast, very little research has focused on gender-related killings of women and girls by a female accused (see Glass et al., 2004; Muftic & Braumann, 2012). This gap is important to fill seeing as in some cases women and girls can also perpetrate gender-related homicide (e.g., in carrying out “honour” killings, same-sex intimate partner homicide) (UNODC, 2018). Female-perpetrated gender-related homicide is not included in the definition used in this article; however, these types of homicide are examined in this text box to provide additional important context.

Between 2011 and 2021, there were 195 homicides involving women and girls both as victims and accused. Of these, 111 (57%) can be classified as gender-related – that is, they were perpetrated by a female intimate partner or family member, sexual violence was part of the homicide or involved victims who were identified as sex workers. An analysis of these cases revealed notable differences compared with gender-related homicides of women and girls perpetrated by a male accused.

Previous research has found that female-perpetrated gender-related killings most often occur between family members, specifically a mother killing her child (Muftic & Baumann, 2012). According to data from the Homicide Survey, between 2011 and 2021, 85% (n=94) involved the homicide of non-spousal family members, more than half of which involved the accused killing her daughter (57%; n=54),Note followed by an extended family member (17%; n=16), a parent (16%; n=15) or sibling (10%; n=9). Of all gender-related homicides of women and girls by a female accused, 8% (n=9) were perpetrated by an intimate partner and the remaining 7% (n=8) by a friend, acquaintance or stranger. Aligned with these patterns, most gender-related homicides occurred at a residential location (88%; n=98).

Frustration, anger or despair most common police-reported motive

Like gender-related homicides of women and girls by a male accused, of those that involved a female accused, stabbing was the most common primary method used to cause death (44%; n=48). However, unlike gender-related homicides where the accused was male, the second most common method was strangulation, suffocation, drowning (21%; n=23), followed by beating (18%; n=19). About 2% (n=2) of gender-related victims killed by a female accused died by shooting.

Four in ten (39%; n=38) female-perpetrated gender-related homicides of women and girls were reported to be motivated primarily by frustration, anger or despair and an additional third (33%; n=32) by an argument or quarrel.Note

Lower proportion of female accused have a criminal history, but a higher proportion have suspected or known mental illness

There were 110 females accused of committing a homicide involving at least one female victim whose homicide was deemed gender-related. Of these, and relative to gender-related homicides of women and girls by a male accused (48%), a lower proportion of female accused (32%; n=35) were reported to have a criminal history. However, a higher proportion of female accused (47%; n=46) were thought by police to have a known or suspected mental or developmental disorder compared to male accused (32%).Note

About one in eight (12%; n=13) female accused died by suicide, a much smaller proportion than what was found when the accused was male (21%). Excluding incidents where the accused died by suicide, 99% (n=96) of gender-related homicides of women and girls by a female accused were cleared by the recommendation or laying of charges. Of these accused, most were charged with second degree murder (56%; n=54), followed by first degree murder (27%; n=26) and manslaughter (17%; n=16). There were no homicides where the most serious charge laid against the accused was infanticide.

End of text box 2

Section 2: Gender-related homicide of Indigenous women and girls involving a male accused

The overrepresentation of Indigenous (First Nations people, Métis and Inuit) populations as victims and persons accused of crime in Canada has a longstanding recognition (Boyce, 2016; Chartrand, 2019; Clark, 2019; Department of Justice, 2022; Heidinger, 2022; Heidinger, 2021; Perreault, 2022; Roberts & Reid, 2017). In addition to their overrepresentation among persons accused of crime, Indigenous people are more likely to have experienced victimization including childhood maltreatment and abuse (Brownridge et al., 2017; Burczycka, 2017; Cotter & Savage, 2019; Heidinger, 2022; Perreault, 2022), violence in general and intimate partner violence in particular (Cotter, 2021; Heidinger, 2021; Heidinger, 2022) and homicide (David & Jaffray, 2022) compared to non-Indigenous people.

The overrepresentation of Indigenous people as victims and persons accused of crime, as well as their increased risk of experiencing violence, are rooted in settler-colonialism and its associated laws and policies (Clark, 2019; Department of Justice, 2022; MMIWG, 2019). With colonization, Indigenous people were dispossessed of their land and resources and subjected to external control with the aim of assimilation or cultural destruction (Clark, 2019; Klingspohn, 2018; MMIWG, 2019). Policies such as the residential school system, the Sixties Scoop and current child welfare practices which remove children from their families continue to maintain colonial violence through the attempted suppression of language, religion and cultural practices, and by the separation of Indigenous families and communities (MMIWG, 2019; Sharma et al., 2021). The immediate and intergenerational trauma associated with these polices has contributed to high rates of mental health issues, suicide, substance use, child maltreatment and family violence among Indigenous populations (Clark, 2019; Menzies, 2020; MMIWG, 2019). Intergenerational trauma, coupled with high rates of poverty, homelessness and barriers preventing equitable access to education, employment, health care and culturally appropriate supports set the foundation for, while simultaneously increasing the risk of, violence.

Moreover, prior Canadian data has shown that Indigenous women and girls experience higher rates of non-lethal violence than Indigenous men and boys (Bingham et al., 2019; Perreault, 2022). Through the lens of intersectionality, higher rates can be explained by multiple, intersecting forms of oppression whereby factors related, but not limited, to gender, class, ability and sexuality can increase the risk of violence (Crenshaw, 1991; MMIWG, 2019). While data limitations restrict an intersectional analysis,Note this section takes the same approach as the analysis presented above, but with a focus on Indigenous (First Nations, Métis and Inuit) victims of gender-related homicide.Note The true number of Indigenous victims of gender-related homicide may be underestimated due to the number of Indigenous women and girls who are missing, died under suspicious circumstances or whose homicide remains unsolved. The analysis excludes homicides where the victim or accused person’s gender was unknown and victims whose Indigenous identity was unknown.Note

One in five gender-related homicides of women and girls involve an Indigenous victim

While only 5% of the female population in Canada identified as Indigenous in 2021 (Statistics Canada, 2022), over the 11-year period of analysis (i.e., 2011 to 2021), police reported that 21% of all gender-related homicides involved Indigenous women and girls, amounting to 233 victims (Table 5).Note Of these victims, and based on information available (for 65% of victims), 11% of Indigenous victims had an active missing person’s report filed with any police service at the time of their death.Note

Another 1,290 non-gender-related homicides of Indigenous people, including both men and women, occurred during the same time period, 8% of whom had an active missing person’s report filed.Note Of the gender-related homicides of Indigenous women and girls, most (62%) victims were identified as First Nations, followed by Inuit (14%) and Métis (6%). The remaining 18% of victims were Indigenous, but there was no recorded indicator to specify if they were First Nations, Métis or Inuit.

Gender-related homicide rate in 2021 for Indigenous women and girls is more than triple the rate of gender-related homicides overall

Since 2001, the rate of gender-related homicide of Indigenous women or girls has fluctuated—with higher rates noted in 2002, 2004, 2007 and 2015, peaks which were in alignment with the homicide rate of Indigenous women and girls overall (Chart 3). In 2021, the rate of gender-related homicide of Indigenous women and girls was more than triple that of gender-related homicides of women and girls overall (1.72 versus 0.54 per 100,000 women and girls).

Chart 3 start

Data table for Chart 3

| Year | Gender-related homicides of Indigenous women and girls | All homicides of Indigenous women and girls | Gender-related homicides of women and girls |

|---|---|---|---|

| rate per 100,000 population | |||

| 2001 | 2.59 | 4.25 | 0.72 |

| 2002 | 5.34 | 7.66 | 0.93 |

| 2003 | 2.75 | 5.15 | 0.68 |

| 2004 | 4.64 | 7.46 | 0.77 |

| 2005 | 2.40 | 4.97 | 0.74 |

| 2006 | 2.79 | 4.96 | 0.67 |

| 2007 | 2.99 | 5.83 | 0.61 |

| 2008 | 2.59 | 3.31 | 0.56 |

| 2009 | 2.23 | 5.15 | 0.61 |

| 2010 | 1.89 | 3.90 | 0.58 |

| 2011 | 2.61 | 4.43 | 0.69 |

| 2012 | 2.51 | 4.52 | 0.55 |

| 2013 | 2.67 | 4.00 | 0.58 |

| 2014 | 2.34 | 3.63 | 0.58 |

| 2015 | 3.17 | 4.87 | 0.66 |

| 2016 | 1.97 | 3.28 | 0.51 |

| 2017 | 2.33 | 4.03 | 0.59 |

| 2018 | 2.47 | 4.64 | 0.53 |

| 2019 | 2.01 | 4.62 | 0.47 |

| 2020 | 2.06 | 4.11 | 0.48 |

| 2021 | 1.72 | 4.31 | 0.54 |

|

Note: Gender-related homicides of women and girls are solved homicides committed by a male accused who was an intimate partner or family member of the victim, inflicted sexual violence on the victim as part of the killing or killed a victim who was identified as a sex worker. Non-gender-related homicides are all those that do not contain the above qualifiers. "Indigenous identity" includes those identified by police as First Nations persons (either status or non-status), Métis, Inuit or an Indigenous identity where the Indigenous group was not known to police. There may be a small number of homicides included in a given year's total that occurred in previous years. Homicides are counted according to the year in which they are reported to Statistics Canada. Rates are calculated on the basis of 100,000 population. Populations are based on July 1 estimates from Statistics Canada, Centre for Demography. Excludes victims where Indigenous identity or gender was coded as unknown. Excludes accused where gender was coded as unknown. Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics, Homicide Survey. |

|||

Chart 3 end

In addition to factors related to colonialism and intergenerational trauma, Indigenous women and girls may experience higher rates of homicide due to systemic and structural barriers which hinder the ability to seek culturally safe supports and help (Klingspohn, 2018; MMIWG, 2019). For example, Indigenous women, especially those living in rural or remote areas, may have trouble accessing supports or services,Note experience racism or discrimination by health care providers, have concerns surrounding confidentiality, and refrain from reporting violence due to a general distrust of police and lack of confidence in the justice system owing, in part, to prior experiences of systemic racism and discrimination (McLane et al., 2022; MMIWG, 2019). As a consequence, without these supports, Indigenous women may remain in dangerous situations that increase the risk of fatal violence occurring.

About six in ten gender-related homicides of Indigenous women and girls are perpetrated by an intimate partner

Similar to findings for gender-related homicides of women and girls overall, between 2011 and 2021, the majority (63%) of gender-related homicides of Indigenous women and girls were perpetrated by an intimate partner, followed by a non-spousal family member (28%) and about one in ten (9%) a non-family member (Table 6). Of the intimate partner gender-related homicides, more than half (52%) were committed by a common-law partner. Of the non-spousal family gender-related homicides, 32% were committed by an extended family member, followed by the victim’s child (30%), a parent (26%) and a sibling (12%). Of these homicides, about seven in ten (69%) had a history of intimate partner or family violence with their accused.Note

There were 226 persons accused of committing a homicide involving at least one Indigenous female victim between 2011 and 2021 whose homicide could be classified as gender-related (Table 7). Just over three quarters (78%) of these accused had a known criminal history, with the largest proportion having a history of violent crimes (61%). Approximately one in five (19%) persons accused of gender-related killings of Indigenous women and girls were thought by police to have a suspected or known mental or developmental disorder.

Conflict within the family and violent behaviour in general can be seen as an extension of the trauma experienced as a result of colonialism, specifically through forced attendance in residential schools, where many Indigenous people were subjected to physical, emotional and sexual abuse (Menzies, 2020; MMIWG, 2019). Due to the frequent use of punishment, coercion and control commonly found in residential schools, as well as negative experiences associated with the Sixties Scoop and the child welfare system, many Indigenous people lacked experiences with nurturing familial environments; all of which are known correlates to perpetrating and experiencing subsequent violence.

Nearly one in four gender-related homicides of Indigenous women and girls involve victims aged 18 to 24

Approximately one quarter (23%) of gender-related homicides of Indigenous women and girls involved victims aged 18 to 24 (Chart 4). While the Indigenous population is younger, on average, than their non-Indigenous counterparts in Canada (Statistics Canada, 2022), this figure is nearly double what was documented among gender-related homicides of women and girls overall (12%).

Chart 4 start

Data table for Chart 4

| Age group (years) | Gender-related homicides of Indigenous women and girls | Non-gender-related homicides of Indigenous people | Gender-related homicides of women and girls |

|---|---|---|---|

| percentage | |||

| 11 and younger | 8.6 | 3.3 | 5.8 |

| 12 to 17 | 7.3 | 5.3 | 3.5 |

| 18 to 24 | 22.7 | 19.6 | 11.9 |

| 25 to 29 | 13.3 | 17.5 | 10.1 |

| 30 to 34 | 10.3 | 15.3 | 9.4 |

| 35 to 39 | 12.4 | 11.9 | 9.9 |

| 40 to 44 | 6.4 | 8.1 | 8.3 |

| 45 to 49 | 9.0 | 7.0 | 7.5 |

| 50 to 54 | 4.7 | 5.0 | 7.7 |

| 55 and older | 5.2 | 7.1 | 26.1 |

|

Note: Gender-related homicides of women and girls are solved homicides committed by a male accused who was an intimate partner or family member of the victim, inflicted sexual violence on the victim as part of the killing or killed a victim who was identified as a sex worker. Non-gender-related homicides are all those that do not contain the above qualifiers but include an Indigenous victim. "Indigenous identity" includes those identified by police as First Nations persons (either status or non-status), Métis, Inuit or an Indigenous identity where the Indigenous group was not known to police. There may be a small number of homicides included in a given year's total that occurred in previous years. Homicides are counted according to the year in which they are reported to Statistics Canada. Excludes victims where Indigenous identity or gender was coded as unknown. Excludes accused where gender was coded as unknown. Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics, Homicide Survey. |

|||

Chart 4 end

More than eight in ten gender-related homicides of Indigenous women and girls occur at a residence

Like gender-related killings of women and girls in general, between 2011 and 2021, more than eight in ten (83%) gender-related homicides of Indigenous women and girls were reported to have occurred at a residential location and about 14% occurred in an open area (Table 5).

Beating most common method in gender-related homicide of Indigenous women and girls

Over the 11-year period of analysis (i.e., 2011 to 2021), the largest proportion (40%) of gender-related homicides of Indigenous women and girls were caused by beating (Table 5). Another quarter (26%) of victims died by stabbing and about one in six (16%) were killed with a firearm. These figures contrast with patterns noted above whereby the largest proportion of gender-related homicides of women and girls overall died by stabbing (34%), followed by shooting (23%) and then beating (21%).

Nearly four in ten gender-related homicides of Indigenous women and girls primarily arose from an argument or quarrel, according to police

While gender-related homicides of women and girls in general were most often motivated by frustration, anger or despair (32%), an argument or a quarrel was the most common (38%) primary motive reported by police in gender-related homicides of Indigenous women and girls (Table 5). That said, nearly one quarter (23%) of such homicides were primarily motivated by frustration, anger or despair and about one in five (18%) resulted from jealousy or envy. Again, the data presented here reflect the primary apparent motive most relevant to the homicide incident as determined by the police investigation and may not coincide with motives presented later in the criminal justice process.

Compared to other homicides involving Indigenous victims, gender-related homicides of Indigenous women and girls more often involve the accused dying by suicide

Between 2011 and 2021, of the 226 persons accused of committing a homicide where at least one Indigenous female victim’s death was classified as gender-related, 12% died by suicide, about half what was documented for incidents of gender-related homicides of women and girls in general (21%) (Table 7). By contrast, 1% of the 1,012 persons accused of committing a non-gender-related homicide of an Indigenous person died by suicide.

After selecting out incidents where the accused died by suicide, nearly all (99.5%) persons accused of committing a gender-related homicide of an Indigenous woman or girl were cleared by the recommendation or laying of charges. Second degree charges were most commonly laid or recommended (66%), followed by first degree (20%) and manslaughter (14%) for persons accused of the gender-related homicide of an Indigenous woman or girl. These findings differ slightly from persons accused of non-gender-related homicide of an Indigenous person whereby second degree charges were laid or recommended most frequently (64%), followed by manslaughter (21%) and first degree murder (15%).

Start of text box 3

Text box 3

The victimization of 2LGBTQ+ and gender diverse individuals

The year 2019 marked the first cycle of collection of the Homicide Survey data for which information on gender identity was reported for victims and persons accused of homicide. Given the small counts of victims and accused persons reported or were identified as being non-binary, their data cannot be presented to protect privacy and confidentiality. Survey data, however, can shed light on the violent victimization of 2LGBTQ+ and gender diverse individuals.Note

According to the Survey of Safety in Public and Private Spaces (SSPPS), in 2018, about 4% of the Canadian population aged 15 and older identified as a sexual minority – that is, being gay, lesbian, bisexual or non-heterosexual sexual – slightly more than half (52%) of whom were women (Jaffray, 2020).

Lending support to research conducted in the United States (Bender & Lauritsen, 2021; Truman & Morgan, 2022), overall, sexual minorities in Canada were more likely to be violently victimized in their lifetime, and within the 12 months preceding the survey even when controlling for age, compared to heterosexual Canadians (Jaffray, 2020).Note While similar proportions of sexual minority men and women reported experiencing physical assault, sexual minority women were much more likely to have been sexually assaulted compared to both sexual minority men and heterosexual women (Jaffray, 2020). The risk of violent victimization was heightened among bisexual women, sexual minorities with a disability and sexual minorities who identified as Indigenous (Jaffray, 2020).

According to the SSPPS, approximately 75,000 people in Canada– or 0.24% of the population aged 15 and older – are transgender, that is individuals whose sex at birth does not match their current gender identity (Jaffray, 2020). Like sexual minorities, transgender people in Canada were more likely to have experienced violent victimization in their lifetime compared to cisgender Canadians (59% versus 37%) (Jaffray, 2020).Note

An intersectional framework can help explain higher rates of violence among sexual- and gender-minority groups. Intersectionality posits that certain individuals are at a higher risk of experiencing violence, discrimination and oppression than others due to intersecting identities (e.g., gender, sexuality, age, class, race, ethnicity) that exacerbate risk or create unique challenges not faced by others (Crenshaw, 1991; Worthen 2020). For example, in addition to being younger on average than their heterosexual and cisgender counterparts, some members of the 2LGBTQ+ community may also experience homophobic, transphobic and heteronormative discrimination which can translate to lower income, education and employment disparities, increased drug use and precarious housing—factors which are known correlates of violent victimization (Grant et al., 2011; Jaffray, 2020; Meyer, 2012; Worthen, 2020).

End of text box 3

Section 3: Gender-related attempted murder of women and girls in Canada

In addition to examining incidents of lethal gender-related violence, it is also informative to look at other forms of severe violence that could have resulted in death to better understand who is most at risk. The following section relies on data from the Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR) Survey on gender-related attempted murders of women and girls, defined as attempted murders perpetrated by a male intimate partner or family member that have been cleared by police.Note Including an analysis of attempted gender-related murders is important as it will help to enhance knowledge on gender-related homicide given the similarities in underlying factors and can help to inform programs and policies. Evidence-based programs and policies can lead to improved access to healthcare in rural areas and more progress in medical technology to treat trauma, which increase the likelihood of surviving injuries that would have historically been fatal (Jena et al., 2014; Morgan & Calleja, 2020; Wilson et al., 2020).

Decline in rate of gender-related attempted murder of women and girls since 2020

Between 2011 and 2021, there were 671 gender-related attempted murders of women and girls perpetrated by a male intimate partner or family member. The rate of gender-related attempted murder of women and girls has been declining since 2017, except for in 2019 where there was a sharp increase (Chart 5). Overall, this trend differs from what was noted above with gender-related homicides of women and girls overall. For example, 2019 marked the year with the lowest rate of recorded gender-related homicides of women and girls, a rate which has increased 16% since that time.

Chart 5 start

Data table for Chart 5

| Year | Attempted murders of all women and girls | Attempted murders of women and girls involving male accused | Attempted murders of women and girls involving a male intimate partner or family member | Attempted murders of all men and boys |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| rate per 100,000 population | ||||

| 2011 | 0.47 | 0.43 | 0.36 | 0.96 |

| 2012 | 0.48 | 0.40 | 0.31 | 0.87 |

| 2013 | 0.52 | 0.45 | 0.36 | 0.87 |

| 2014 | 0.47 | 0.43 | 0.32 | 0.88 |

| 2015 | 0.45 | 0.42 | 0.34 | 1.00 |

| 2016 | 0.53 | 0.51 | 0.36 | 0.88 |

| 2017 | 0.51 | 0.48 | 0.35 | 1.05 |

| 2018 | 0.45 | 0.40 | 0.29 | 0.95 |

| 2019 | 0.54 | 0.50 | 0.41 | 0.94 |

| 2020 | 0.46 | 0.43 | 0.35 | 0.98 |

| 2021 | 0.45 | 0.39 | 0.27 | 0.80 |

|

Note: For the purposes of analysis, includes cleared incidents with a single victim and a single accused. Rates are calculated on the basis of 100,000 population. Populations are based on July 1 estimates from Statistics Canada, Centre for Demography. Excludes victims and accused where gender was coded as unknown. Based on the Incident-based Uniform Crime Reporting Survey, Trend Database, which, as of 2009, includes data for 99% of the population in Canada. Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics, Incident-based Uniform Crime Reporting Survey, Trend Database. |

||||

Chart 5 end

A different trend occurred with the attempted murder of men and boys, as the rate peaked in 2017, had another uptick in 2020 before declining to the lowest rate documented in the time period analyzed.

Rate of gender-related attempted murder of women and girls highest in Quebec

In 2021, there was a rate of 0.27 gender-related attempted murders per 100,000 women and girls in Canada (Table 8). Quebec and Ontario were the only provinces with rates which exceeded the national rate (0.42 and 0.31, respectively). There were no gender-related attempted murders of women and girls documented in Manitoba, Saskatchewan and the territories in 2021. These rates may be indicative of the proportion of the population living in urban versus rural areas and corresponding access to and quality of healthcare such that the high rates of gender-related attempted murders in Ontario and Quebec reflect the availability of lifesaving measures, which may not have been available in the Prairie provinces and territories where a higher population of the population live in rural areas.

Compared to 2011, in 2021 there was a 25% decline in the rate of gender-related attempted murder of women and girls in Canada. In fact, declines were documented in each province, except for Atlantic Canada and Ontario which had increases in gender-related attempted murder rates (+44% and +4%, respectively).Note

When examining the annual rate of gender-related attempted murders of women and girls in the provinces at three different points in time (i.e., 2011, 2016 and 2021), Quebec had the highest for each of the years, a rate which consistently exceeded what was documented nationwide. Indeed, in each of the years, the rates in Quebec were similar when comparing gender-related and non-gender-related attempted murders, an observation not found in other provinces. The accessibility and quality of healthcare in Quebec may be a contributing factor—the higher rates of attempted murder may reflect an increased availability of lifesaving measures; an explanation supported in part by the often lower rates of gender-related and non-gender-related homicide in that province. Other possible explanations include differing charging practices in Quebec (e.g., the laying of an attempted murder charge rather than assault level 3), increased clearance rates for attempted murder or that the three years examined were outliers and not necessarily reflective of Quebec’s situation.

Vast majority of gender-related attempted murders of women and girls occur at residential locations

Over the 11-year period (i.e., 2011 to 2021), 87% of all gender-related attempted murders of women and girls occurred at residential locations—including houses, dwelling units and other structures located on private property (Table 9). This figure exceeds the proportion of non-gender-related attempted murders, where half (51%) occurred at residential locations and around one-third (34%) in open areas such as parking lots, streets and on public transit or associated facilities.

Nearly one in five gender-related attempted murders of women and girls involve physical force alone

Between 2011 and 2021, nearly one in five (18%) gender-related attempted murders were committed with physical force alone. This compares to only 4% of non-gender-related attempted murders, whereby a much higher proportion involved the presence of a weapon (96% versus 82%).

While similar proportions of gender-related and non-gender-related attempted murders involved victims who sustained a physical injury (93% and 94%, respectively), a smaller proportion of gender-related attempted murders of women and girls involved victims who were reported to have sustained a major physical injury (59% versus 75%).

Start of text box 4

Text box 4

The Canadian Femicide Observatory for Justice and Accountability

In 2015, the United Nations Special Rapporteur on Violence Against Women called for all countries to develop femicide watches to document, collect and analyze data on the gender-related killings of women and girls to generate comparable data to be used for preventative and protective purposes (ACUNS, 2017). In responding to this call, the Canadian Femicide Observatory for Justice and Accountability (CFOJA), a non-governmental agency funded by the Centre for the Study of Social and Legal Responses to Violence, University of Guelph, the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada and the Canada Research Chair Program, was launched on December 6, 2017. The CFOJA, supported by an interdisciplinary advisory panel of experts nationwide, aims to increase the visibility of femicide in Canada by documenting such killings as they occur while simultaneously monitoring government, legal and social responses to these killings (Dawson et al., 2019b).

The CFOJA defines femicide “as the killing of all women and girls primarily, but not exclusively, by men” (Dawson et al. 2019a; Dawson et al., 2019b; Dawson et al., 2021). It is the goal of the CFOJA, however, to direct subsequent efforts to develop more specific parameters that can capture the “killed because they were women” elements of narrower definitions of femicide and to identify its various subtypes.

Since its inception in 2017, the CFOJA has collected, analyzed and shared open source data on the homicides of women and girls in Canada, as reported in the media and public court records, from 2016 to 2021 inclusive. On an annual basis, they release a report which presents annual statistical data on the characteristics of women and girls killed in Canada, describes and applies common sex/gender-related motives and indicators to individual cases, while also touching upon special topics, and current and emerging research priorities.

End of text box 4

Summary

Using 11 years (i.e., 2011 to 2021) of pooled data from the Homicide Survey and Uniform Crime Reporting Survey, this Juristat examined trends and characteristics of gender-related homicides and gender-related attempted murders of women and girls in Canada.

There were 1,125 gender-related homicides of women and girls in Canada; that is, solved homicides committed by a male accused who was an intimate partner or family member of the victim, inflicted sexual violence on the victim as part of the killing or killed a victim who was identified as a sex worker. There were an additional 671 gender-related attempted murders of women and girls perpetrated by a male intimate partner or family member.

In 2021, the highest rate of gender-related homicide of women and girls was reported in the territories, followed by Saskatchewan and Manitoba. For gender-related attempted murders, the opposite was true as there were no recorded incidents in those regions. These differences may be due to the high proportion of these residents living in rural locations where the healthcare necessary to treat potentially fatal injuries may be sparse or difficult to access.

Of all gender-related homicides of women and girls that occurred between 2011 and 2021, most victims died by stabbing, although when focusing on rural areas specifically, a larger proportion died by shooting. Police reported that gender-related homicides of women and girls were most often motivated by the accused’s anger, frustration or despair – almost triple the proportion found among non-gender-related homicides.

Between 2011 and 2021, one in five gender-related homicides involved an Indigenous woman or girl. There were notable differences between these homicides and gender-related homicides of women and girls overall. Specifically, Indigenous victims were younger, the largest proportion died by beating and police most often reported the homicide as being motivated by an argument or quarrel.

While these findings provide novel information on the gender-related homicide of women and girls in Canada, they are limited by the data currently available. The Homicide Survey captures some indicators commonly used by experts to identify gender-related homicides—such as those used in the definition adopted in this Juristat—but not others (e.g., prior violence across all relationship types, mutilation or public disposal of the victim’s body). Despite these limitations, the current article provides an important overview of recent trends in gender-related homicides of women and girls in Canada. Future work can further supplement this analysis by combining data from the Homicide Survey with other sources to explore other contextual factors surrounding this type of gender-based violence.

Detailed data tables

Survey description

Homicide Survey

The Homicide Survey collects police-reported data on the characteristics of all homicide incidents, victims and accused persons in Canada. The Homicide Survey began collecting information on all murders in 1961 and was expanded in 1974 to include all incidents of manslaughter and infanticide. Although details on these incidents are not available prior to 1974, counts are available from the Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR) Survey and are included in the historical aggregate totals.

When a homicide becomes known to police, the investigating police service completes the survey questionnaires, which are then sent to Statistics Canada. There are cases where homicides become known to police months or years after they occurred. These incidents are counted in the year they become known to police (based on the report date). Information on persons accused of homicide is only available for solved incidents (i.e., where at least one accused has been identified). Accused characteristics are updated as homicide cases are solved, and new information is submitted to the Homicide Survey. Information collected through the victim and incident questionnaires is also updated accordingly when a case is solved. For incidents involving more than one accused, only the relationship between the victim and the closest accused is recorded.

Because of revisions to the Homicide Survey database, annual data reported by the Homicide Survey prior to 2015 may not match the annual homicide counts reported by the UCR Survey. Data from the Homicide Survey are appended to the UCR database each year for the reporting of annual police-reported crime statistics. Each reporting year, the UCR Survey includes revised data reported by police for the previous survey year. In 2015, a review of data quality was undertaken for the Homicide Survey for all survey years from 1961 to 2014. The review included the collection of incident, victim, and charged and suspect-chargeable records that were previously unreported to the Homicide Survey. In addition, the database excludes deaths and associated accused records, which are not deemed as homicides by police any longer (i.e., occurrences of self-defence, suicide, criminal negligence causing death that had originally been deemed, but no longer considered homicides, by police). For operational reasons, these revisions were not applied to the UCR Survey.

Incident-based Uniform Crime Reporting Survey

The Incident-based Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR) Survey collects detailed information on criminal incidents that have come to the attention of police services in Canada. Information includes characteristics of victims, accused persons and incidents. In 2021, data from police services covered 99% of the population of Canada.

One incident can involve multiple offences. In order to ensure comparability, counts are presented based on the most serious offence related to the incident as determined by a standard classification rule used by all police services.

Victim age is calculated based on the end date of an incident, as reported by the police. Some victims experience violence over a period of time, sometimes years, all of which may be considered by the police to be part of one continuous incident. Information about the number and dates of individual incidents for these victims of continuous violence is not available.

The option for police to code victims as “gender diverse” in the UCR Survey was implemented in 2018. In the context of the UCR Survey, “gender diverse” refers to a person who publicly expresses as neither exclusively male nor exclusively female. Given that small counts of victims identified as being gender diverse may exist, the UCR data available to the public has been recoded with these victims distributed in the “male” or “female” categories based on the regional distribution of victims’ gender. This recoding ensures the protection of confidentiality and privacy of victims.

References

Academic Council on the United Nations System (ACUNS). (2017). Femicide volume VII: Establishing a femicide watch in every country.

Allen, T., Salari, S., & Buckner, G. (2020). Homicide illustrated across the ages: Graphic descriptions of victim and offender age, sex, and relationship. Journal of Aging and Health, 32(3-4).

Armstrong, A., & Jaffray, B. (2021). Homicide in Canada, 2020. Juristat. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 85‑002-X.

Bender, A.K., & Lauritsen, J.L. (2021). Violent victimization among lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations in the United States: Findings from the National Crime Victimization Survey, 2017-2018. AJPH Research and Analysis, 111(2), 318-326.

Beyer, K.M.M., Layde, P.M., Hamberger, L.K., & Laud, P.W. (2013). Characteristics of the residential neighbourhood environment differentiate intimate partner femicide in urban versus rural settings. Journal of Rural health, 39, 281-293.

Bingham, B., Moniruzzaman, A., Patterson, M., Sareen, J., Distasio, J., O’Neil, J., & Somers, J.M. (2019). Gender differences among Indigenous Canadians experiencing homelessness and mental illness. BMC Psychology, 7(57), 1-12.

Bows, H. (2019). Domestic homicide of older people (2010-15): A comparative analysis of intimate-partner homicide and parricide cases in the UK. British Journal of Social Work, 49(5).

Boyce, J. (2016). Victimization of Aboriginal people in Canada, 2014. Juristat. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 85-002-X.

Brennan, S., & Boyce, J. (2013). Family-related murder-suicides. Family violence in Canada: A statistical profile, 2011. Juristat. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 85-002-X.

Brownridge, D., Taillieu, T., Afifi, T., Chan, K., Emery, C., Lavoie, J., & Elgar, F. (2017). Child maltreatment and intimate partner violence among Indigenous and non-Indigenous Canadians. Journal of Family Violence, 32(6), 607-619.

Burczycka, M. (2017). Profile of Canadian adults who experienced childhood maltreatment. In Family violence in Canada: A statistical profile, 2015. Juristat. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 85-002-X.

Campbell, J., Webster, D.W., & Glass, N. (2009). The Danger Assessment: Validation of a lethality risk assessment instrument for intimate partner femicide. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 24(4), 653-674.

Caputi, J., & Russell, D.E. (1990). Femicide: Speaking the unspeakable.

Chartrand, V. (2019). Unsettled times: Indigenous incarceration and the links between colonialism and the penitentiary in Canada. Canadian Journal of Criminology and Criminal Justice, 61(3), 67-89.

Clark, S. (2019). Overrepresentation of Indigenous people in the Canadian criminal justice system: Causes and responses. Research and Statistics Division, Department of Justice.

Conroy, S., & Sutton, D. (2022). Violence against seniors and their perceptions of safety in Canada. Juristat. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 85-002-X.

Conroy, S. (2021). Spousal violence in Canada, 2019. Juristat. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 85-002-X.

Cotter, A. (2021). Intimate partner violence in Canada, 2018: An overview. Juristat. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 85-002-X.

Crenshaw, K. (1991). Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanford Law Review, 43(6), 1241–1299.

Cullen, P., Vaughan, G., Li, Z., Price, J., Yu, D., & Sullivan, E. (2019). Counting dead women in Australia: An in-depth case review of femicide. Journal of Family Violence, 34(1), 1-8.

David, J.-D., & Jaffray, B. (2022). Homicide in Canada, 2021. Juristat. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 85‑002‑X.

Dawson, M., & Carrigan, M. (2021). Identifying femicide locally and globally: Understanding the utility and accessibility of sex/gender-related motives and indicators. Current Sociology, 69(5), 682-704.

Dawson, M., Sutton, D., Zecha, A., Boyd, C., Johnson, A., & Mitchell, A. (2021). #CallItFemicide: Understanding sex/gender-related killings of women and girls in Canada, 2020. Canadian Femicide Observatory for Justice and Accountability.

Dawson, M., Sutton, D., Carrigan, M., Grand’Maison, V., Bader, D., Zecha, A., & Boyd, C. (2019a). #CallItFemicide: Understanding gender-related killings of women and girls in Canada 2019. Canadian Femicide Observatory for Justice and Accountability.

Dawson, M., Sutton, D., Carrigan, M., & Grand’Maison, V. (2019b). #CallItFemicide: Understanding gender-related killings of women and girls in Canada 2018. Canadian Femicide Observatory for Justice and Accountability.

Department of Justice. (2022). Understanding the overrepresentation of Indigenous people in the criminal justice system.

DeKeseredy, W.S. (2020). Woman abuse in rural places. London: Routledge.

Gadermann, A.C., Thomson, K.C., Richardson, C.G., Gagné, M., McAuliffe, C., Hirani, S., & Jenkins, E. (2021). Examining the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on family mental health in Canada: Findings from a national cross-sectional study. BMJ Open, 11(1), 1-11.

Gillespie, L.K., & Reckdenwald, A. (2017). Gender equality, place, and female-victim intimate partner homicide: A county-level analysis in North Carolina. Feminist Criminology, 12(2), 171-191.

Glass, N., Koziol-McLain, J., Campbell, J., & Block, C.R. (2004). Female-perpetrated femicide and attempted femicide: A case study. Violence Against Women, 10(6), 606-625.

Government of Saskatchewan. (2022). Action plan on interpersonal violence and abuse: Backgrounder.

Grant, J.M., Mottet, L.A., & Tanis, J. (2011). Injustice at every turn: A report of the National Transgender Discrimination Survey.

Heidinger, L. (2022). Violent victimization and perceptions of safety: Experiences of First Nations, Métis and Inuit women in Canada. Juristat. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 85-002-X.

Heidinger, L. (2021). Intimate partner violence: Experiences of First Nations, Métis and Inuit women in Canada, 2018. Juristat. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 85-002-X.

Ibrahim, D. (2022). Canadian residential facilities for victims of abuse, 2020/2021. Juristat. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 85-002-X.

Jaffray, B. (2020). Experiences of violent victimization and unwanted sexual behaviours among gay, lesbian, bisexual and other sexual minority people, and the transgender population, in Canada, 2018. Juristat. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 85-002-X.

Jena, A.B., Sun, E.C., & Prasad, V. (2014). Does the declining lethality of gunshot injuries mask a rising epidemic of gun violence in the United States? Journal of General Internal Medicine, 29(7), 1065-1069.

Johnson, H., Eriksson, L., Mazerolle, P., & Wortley, R. (2019). Intimate femicide: The role of coercive control. Feminist Criminology, 14(1), 3-23.