Victimization of men and boys in Canada, 2021

by Danielle Sutton

Highlights

- In 2021, 192,413 men and boys were victims of police-reported violent crime in Canada, representing a rate of 1,015 victims per 100,000 male population and accounting for just under half (46%) of all victims of violent crime reported to police.

- Between 2016 and 2021, the rate of victimization of men and boys increased 12%, with increases observed for most age groups. The largest increase was documented among men aged 45 and older (+22%).

- In 2021, the highest rate of victimization against men and boys was reported by police in the territories, followed by Manitoba and Saskatchewan. However, among the provinces, for boys aged 11 and younger, the highest rate was in Newfoundland and Labrador and, for those aged 12 to 17, in New Brunswick.

- The rate of victimization against men and boys was higher in almost all provincial rural areas, driven by violence in the rural North. The rate of violent victimization against men and boys was 3,519 per 100,000 population in the rural North, three times higher than the rate in the rural South (1,034) and nearly four times higher than in urban areas (936).

- Of the census metropolitan areas, the highest rate of victimization against men and boys was documented in Thunder Bay (1,737), followed by Lethbridge (1,633) and Moncton (1,575).

- Compared to women and girls, men and boys experienced higher rates of more severe forms of victimization: homicide, other violations causing death and attempted murder, assault level 2, robbery, assault level 3 and extortion. Sexual assault was a notable exception to this trend.

- Physical force was used against half (51%) of all male victims and an additional 30% experienced victimization with a weapon present. Four in ten (40%) males sustained a physical injury as a result of the violent victimization.

- In 2021, of those whose violent victimization was reported to police, eight in ten (79%) men and boys were victimized by someone outside the family. Boys aged 11 and younger were most often victimized by a family member (59%) but, with increasing age, proportionately more males were victimized by a non-family member.

- In 2021, the homicide rate for men and boys was three times higher than that for women and girls (3.08 versus 1.02 per 100,000 population). The highest homicide rate among all groups was for men aged 18 to 24 (6.72).

- Between 2011 and 2021, the homicide rate among men and boys increased 22%, driven largely by the homicide of men aged 25 and older (+32%).

- Males aged 12 and older were most commonly killed by someone outside the family, such as by a friend, stranger or acquaintance.

- Between 2011 and 2021, shooting was the most common method used to cause the death of men and boys, almost double what was documented for women and girls (40% versus 22%).

In recent years, there have been several calls to action to address and prevent violence against women, with the acknowledgement that women experience certain forms of violence, within particular relationships, disproportionately. This has resulted in the recognition of violence against women as a public health concern requiring immediate attention. The Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics has released many gender-based violence reports which highlight the victimization of women and girls and, while corresponding data for men and boys is shown comparatively, they have typically not been the focus of analysis. As a result, there is a gap in understanding the trends and characteristics associated with violence against men and boys in Canada and internationally. This gap is important to fill considering that police-reported data in Canada have consistently shown similarity in violent victimization rates between men and women (Allen & McCarthy, 2018; Conroy, 2018; Moreau,2022), yet the circumstances and risk factors surrounding such victimization often differ.

For example, prior research has shown that, compared to women, violence against men often occurs between non-intimates—typically strangers or acquaintances—is more likely to have a weapon present and often involves quite different, sometimes more severe forms of victimization (e.g., violations causing death, robbery, aggravated assault) (Allen & McCarthy, 2018; Conroy, 2018; Cotter & Savage, 2019; Lauritsen & Carbone-Lopez, 2011; Statistics Canada, 2022a; Warnken & Lauritsen, 2019). Moreover, violence can affect the well-being—both short- and long-term—of men, women and gender-diverse individuals personally, in their relationships with others and with the community (Coker et al., 2002; Mercy et al., 2017). Consequences of victimization include, but are not limited to, physical injury and mental health problems, increased substance use, economic losses, the development of infectious and non-communicable diseases as well as increased risk of future violence (Mercy et al., 2017; UNODC, 2019a).

Using police-reported data from the Incident-based Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR) Survey and the Homicide Survey, and self-reported data from the General Social Survey on Canadians’ Safety (Victimization), this Juristat explores trends and characteristics of violence against men and boys in Canada. While some gender comparisons are drawn, the primary objective is to spotlight male victimization in Canada by examining police-reported and self-reported data.

Start of text box 1

Text box 1

Data sources and definitions

This Juristat article presents information drawn predominately from police-reported data sources, specifically the Incident-based Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR) Survey and the Homicide Survey. As such, the focus of this article is to provide information on violent crime that was reported to and substantiated by police services in Canada.Note However, because not all crime is reported to police, especially among males whose victimization, relative to females, is less likely to be reported to the authorities (Bosick et al., 2012), this article also presents self-reported data drawn from the General Social Survey (GSS) on Canadians’ Safety (Victimization) to complement police-reported data. The GSS surveys a sample of Canadians aged 15 and older on their experiences of victimization, regardless of whether such experiences were reported to the police. Though the data are not directly comparable with police-reported data, the two sources can be used together to provide a fulsome picture of the experiences of victims of crime.

Because the risk of and experiences with victimization vary across the lifespan (Conroy, 2018; Kelsay et al., 2017; UNODC, 2019b), victims are grouped into the following age categories for analysis of UCR data:

- Victims aged 11 and younger

- Victims aged 12 to 17

- Victims aged 18 to 24

- Victims aged 25 to 34

- Victims aged 35 to 44

- Victims aged 45 and older

While the focus of this article is on the victimization of men and boys, information on violence against women and girls will also be presented and discussed where differences exist.

For both police-reported and self-reported data, victim gender refers to public expressions and internal feelings of gender identity which may differ from the sex they were assigned at birth (i.e., male or female). As such, within this article, males refer to those who present or identify as male, and females as those who present or identify as female, regardless of their sex at birth.Note

End of text box 1

Section 1: Police-reported victimization of men and boys

This section draws from police-reported data, specifically the Incident-based Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR) Survey, to present information on the characteristics and trends associated with the victimization of men and boys in Canada. All self-reported information related to men’s experiences with violent victimization are limited to text boxes to clearly distinguish data sources.

Rate of police-reported violence against men and boys increases until the 25-to-29-year age group before declining

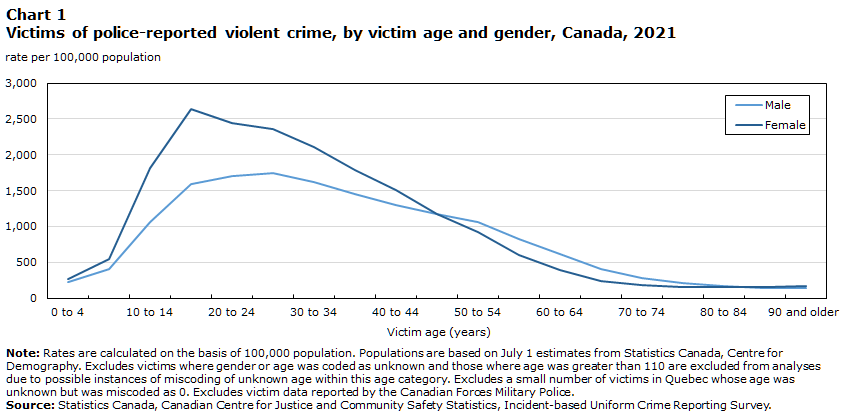

In 2021, there were 192,413 male victims of police-reported violent crime in Canada,Note representing a rate of 1,015 victims per 100,000 male population and accounting for just under half (46%) of all victims of violent crime reported to police. Overall, the highest rate of violent victimization was found among men aged 25 to 34 (1,681), followed closely by those aged 18 to 24 (1,660). These findings contrast with rates documented among women and girls, where the highest rate of police-reported violence was among girls aged 12 to 17 (2,574).

Taking a closer look at age, the rate of violent victimization steadily increased for boys and men up to the 25-to-29-year age group, where the rate peaked at 1,741 victims per 100,000 men (Chart 1). In general, the rate of victimization then began to decline with increasing age. On the other hand, the victimization rate among girls and women peaked within the 15-to-19-year age group (2,633). The rate of violent victimization of girls and women exceeded what was documented among similarly aged boys and men until the 50-to-54-year age group at which point the victimization rate was higher for men than women, until age 80 to 84.

Chart 1 start

Data table for Chart 1

| Victim age | Male | Female |

|---|---|---|

| rate per 100,000 population | ||

| 0 to 4 | 228 | 267 |

| 5 to 9 | 414 | 551 |

| 10 to 14 | 1,070 | 1,817 |

| 15 to 19 | 1,597 | 2,633 |

| 20 to 24 | 1,701 | 2,448 |

| 25 to 29 | 1,741 | 2,364 |

| 30 to 34 | 1,621 | 2,111 |

| 35 to 39 | 1,453 | 1,788 |

| 40 to 44 | 1,302 | 1,503 |

| 45 to 49 | 1,172 | 1,176 |

| 50 to 54 | 1,058 | 923 |

| 55 to 59 | 832 | 606 |

| 60 to 64 | 614 | 400 |

| 65 to 69 | 403 | 247 |

| 70 to 74 | 282 | 186 |

| 75 to 79 | 207 | 154 |

| 80 to 84 | 167 | 153 |

| 85 to 89 | 139 | 152 |

| 90 and older | 147 | 175 |

|

Note: Rates are calculated on the basis of 100,000 population. Populations are based on July 1 estimates from Statistics Canada, Centre for Demography. Excludes victims where gender or age was coded as unknown and those where age was greater than 110 are excluded from analyses due to possible instances of miscoding of unknown age within this age category. Excludes a small number of victims in Quebec whose age was unknown but was miscoded as 0. Excludes victim data reported by the Canadian Forces Military Police. Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics, Incident-based Uniform Crime Reporting Survey. |

||

Chart 1 end

Much of the gender gap in the rate of victimization, however, was driven by sexual assault offences. Research has shown that women and girls comprise the majority of sexual assault victims (Allen & McCarthy, 2018; Conroy, 2018; Cotter, 2021a; Cotter & Savage, 2019), whereas physical assault offences are common among men and boys. As such, when looking at victimization rates by offence type, a different pattern emerges. Specifically, rates of physical assault offences are higher for boys than girls up to the 15-to-19-year age group, at which time victimization rates among females exceed males up to and including the 40-to-44-year age group (Chart 2).

Chart 2 start

Data table for Chart 2

| Victim age | Male victims | Female victims | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical assault offences | Sexual assault offences | Physical assault offences | Sexual assault offences | |

| rate per 100,000 population | ||||

| 0 to 4 | 149 | 41 | 116 | 111 |

| 5 to 9 | 266 | 101 | 181 | 323 |

| 10 to 14 | 661 | 139 | 541 | 983 |

| 15 to 19 | 1,002 | 93 | 1,096 | 1,022 |

| 20 to 24 | 1,179 | 37 | 1,479 | 410 |

| 25 to 29 | 1,276 | 29 | 1,526 | 279 |

| 30 to 34 | 1,193 | 22 | 1,392 | 208 |

| 35 to 39 | 1,054 | 17 | 1,175 | 154 |

| 40 to 44 | 925 | 14 | 982 | 111 |

| 45 to 49 | 837 | 9 | 754 | 86 |

| 50 to 54 | 744 | 9 | 590 | 59 |

| 55 to 59 | 581 | 6 | 379 | 38 |

| 60 to 64 | 424 | 3 | 246 | 20 |

| 65 to 69 | 272 | 3 | 150 | 13 |

| 70 to 74 | 188 | 1 | 115 | 12 |

| 75 to 79 | 134 | 2 | 93 | 16 |

| 80 to 84 | 113 | 2 | 96 | 18 |

| 85 to 89 | 110 | 3 | 100 | 25 |

| 90 and older | 111 | 5 | 132 | 25 |

|

Note: Rates are calculated on the basis of 100,000 population. Populations are based on July 1 estimates from Statistics Canada, Centre for Demography. Physical assault offences include all physical assault related violations (e.g., all assault levels, unlawfully causing bodily harm, discharge firearm with intent, other). Sexual assault offences include all sexual assault related violations (e.g., all sexual assault levels, sexual offences against children). Victims where gender or age was coded as unknown and those where age was greater than 110 are excluded from analyses due to possible instances of miscoding of unknown age within this age category. Excludes a small number of victims in Quebec whose age was unknown but was miscoded as 0. Excludes victim data reported by the Canadian Forces Military Police. Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics, Incident-based Uniform Crime Reporting Survey. |

||||

Chart 2 end

Higher rates of physical assault offences among men and boys

In 2021, men and boys experienced high rates of physical assault offences (708 per 100,000 male population) relative to all other violent offences (Table 1). Specifically, police-reported data revealed assault level 1 as the most common violation (433), followed by assault level 2 (207).Note

While the overall rate of police-reported victimization was higher among women and girls compared to men and boys (1,190 versus 1,015 per 100,000 population), higher rates of more severe forms of victimization, excluding sexual assault, were seen among men and boys. For example, and lending support to prior research highlighting increased violence severity among males (Conroy, 2018; Felson, 2002), men and boys were victims of homicide, other violations causing death and attempted murder at a rate three times greater than women and girls (6 versus 2). Similarly, for men and boys, higher rates were documented for assault level 2 (207), robbery (58), assault level 3 (14) and extortion (14) than what was the case for women and girls (155, 25, 6 and 7, respectively).

Women and girls, on the other hand, experienced higher rates of assault level 1 (508 per 100,000 population), sexual offences (220), criminal harassment (65), and indecent or harassing communications (31) compared to men and boys (433, 31, 21 and 13, respectively). Notwithstanding similar rates of police-reported violence across genders in aggregate form for physical assault offences and other offences involving violence or the threat of violence, with the exception of sexual offences, it is important to note that men and women have different experiences with certain types of violent offences in Canada.

Start of text box 2

Text box 2

Sextortion

Based on available Canadian data, one type of crime that appears to affect boys and young men disproportionately is sextortion. Sextortion involves a person threatening to disseminate sexually explicit or intimate images of someone without their consent for the purposes of obtaining additional images, sexual acts or money (Canadian Centre for Child Protection, 2022b; Patchin & Hinduja, 2020; Wolak et al., 2018). While the term “sextortion” is not used in the Criminal Code, the term often refers to conduct that is a type of extortion, which is an offence under the Criminal Code. In addition, there are a number of charges (e.g., child pornography offences, harassment, non-consensual distribution of intimate images) which can be laid by police and prosecutors depending on the circumstances of each case.

Data compiled by CyberTip, Canada’s national tipline for reporting the abuse and exploitation of children online, revealed a 150% increase in reported instances of youth being sextorted online between December 2021 and May 2022 (Canadian Centre for Child Protection, 2022b).Note The vast majority (87%) of sextortion incidents reported to CyberTip affected boys—typically those aged 15 to 17—who were often contacted via social media where they were tricked into sharing sexually explicit images or were unknowingly recorded while exposing themselves over livestream (Canadian Centre for Child Protection, 2022a; Canadian Centre for Child Protection, 2022b; Canadian Centre for Child Protection, 2021). Following this, the extortionist makes demands and threatens to share the photos or videos with the youth’s social network if they do not comply.

One in twenty males between the ages of 15 to 24 reported someone sharing or posting embarrassing photos of themselves online

The 2019 General Social Survey on Canadians’ Safety (Victimization) did not capture information on sextortion specifically. However, it did collect information on cyber-bullying or cyber-stalking experiences within the five years preceding the survey, including where someone shared or posted photos that were embarrassing or made the respondent feel threatened. Though not specific to the distribution of sexually explicit or intimate photos, results reveal important information.

Just over one percent of Canadians reported having such experiences, of which 49% were male. Of these males, more than half (55%) were between the ages of 15 and 24, while about 26% of females were aged 15 to 24. Stated differently, about 1 in 20 (4.2%) young males reported having an embarrassing photo shared or posted within the past five years compared to about 1 in 50 similarly aged females (2.2%).

End of text box 2

Start of text box 3

Text box 3

Self-reported victimization and associated emotional impacts

According to the 2019 General Social Survey (GSS) on Canadians’ Safety (Victimization), about 548,000 men aged 15 and older experienced violent victimization in the 12 months preceding the survey,Note representing a rate of 59 victims per 1,000 male population. Of these men, the highest overall rate of violent victimization was documented among those aged 15 to 24 (103 victims per 1,000 male population).Note Men aged 15 to 24 also reported the highest rates of sexual assault and robbery (27 and 17 victims per 1,000, respectively). The highest rate of physical assault, however, was documented among men aged 25 to 34 (68 victims per 1,000).

Of the men who experienced non-spousal violent victimization in the 12 months preceding the survey, more than seven in ten (72%) reported an emotional impact as a result of their victimization. The most commonly reported emotional impact was anger (46%), followed by feeling upset, confused or frustrated (37%), annoyed (33%) and being more cautious or aware (30%).Note Prior research indicates that only a fraction of men seek formal assistance for emotional problems related to victimization (Campagna & Zaykowski, 2020) and, according to the GSS, a significantly smaller proportion of men than women reported seeking out formal services for any reason following violent victimization (7% versus 18%).

Finally, of those who had reported an emotional impact following the violent victimization, about three in ten (29%) men reported a longer term consequence. Specifically, one-fifth (20%) indicated they felt constantly on guard, watchful or easily startled. One in six (17%) had tried hard not to think about the incident or went out of their way to avoid situations that reminded them of the victimization and one in eight (13%) reported feeling numb or detached from others, activities or surroundings.

End of text box 3

Rates of police-reported violent crime against men and boys increasing since 2016

Between 2011 and 2021, according to UCR data, the rate of victimization against men and boys declined by about 6%, largely due to declines in the victimization of boys aged 12 to 17 and young men aged 18 to 24 (-28% and -26%, respectively) (Table 2).Note Of note, the rate of victimization against men aged 45 and older increased by 16% over the same period whereas minor rate changes were documented among the other age categories.

However, since 2016, the rate of male victimization increased 12%, with increases observed for every age group with the exception of men aged 18 to 24, where there was a slight decline (-1.3%). The largest increase was documented against men aged 45 and older (+22%). Men aged 45 and older were also the only age group with a higher rate of victimization in 2021 compared to similarly aged women (659 versus 516 per 100,000 population).

Rate of police-reported violence against men and boys highest in the territories and the Prairie Provinces

In 2021, similar to patterns documented in previous years (Allen & McCarthy, 2018; Conroy, 2021b; Conroy, 2018; Perreault & Simpson, 2016), the highest rate of victimization against men and boys was reported by police in the Northwest Territories (7,926 per 100,000 male population), followed by Nunavut (7,003) and Yukon (3,276) (Table 3). Aligned with age patterns observed in Canada overall, the highest rate of violence in each of the territories was documented against men aged 25 to 34 years. That said, the relatively small population counts in the territories, alongside a comparatively younger median age of inhabitants, produces higher and more unstable rates that should be interpreted cautiously. Of note, these areas of the country are regions where violent crime is high overall (Moreau, 2022).

In the provinces, the rate of violence against men and boys was highest in Manitoba (1,805 per 100,000 male population), followed by Saskatchewan (1,666). Some provincial variation exists, however, when examining rates among younger males. For boys aged 11 and younger, the highest rate of violence was in Newfoundland and Labrador (727 per 100,000 boys) and for those aged 12 to 17, police in New Brunswick reported the highest rate (2,553). For all other age groups, the highest rates of violent victimization were reported in Manitoba.

Compared to urban areas, higher rate of violence against men and boys in most rural areas

In 2021, the overall rate of police-reported violence against men and boys was 1.5 times higher in rural compared to urban areas (1,438 versus 936 per 100,000 male population).Note Indeed, the rate of victimization against men and boys was higher in almost all provincial rural areas, with the exception of Prince Edward Island, than what was documented in provincial urban areas.Note

The high rates of rural violence, however, were due in large part to victimization reported to police in the rural North (Table 3).Note Specifically, in 2021, the rate of violent victimization against men and boys was 3,519 per 100,000 population in the rural North, three times higher than the rate in the rural South (1,034) and nearly four times higher than in urban areas (936). Among the provinces, the largest differences were noted in Saskatchewan, where the rate of victimization was seven times higher in the rural North versus the rural South (10,952 versus 1,528) and almost nine times higher than in urban areas (1,242). Similarly, in Manitoba, the rate of violence against men and boys was about six times higher in the rural North compared to the rural South (7,784 versus 1,340) and five times higher than what was documented in urban areas (1,434).

It follows that the rate of violence against men and boys was lower in census metropolitan areas (CMAs)Note compared to non-CMAs (871 versus 1,379) (Table 4). That said, rates varied widely among the CMAs. The highest rates of victimization among men and boys were found in Thunder Bay (1,737),Note followed by Lethbridge (1,633) and Moncton (1,575). To contrast, the lowest rates of violence were documented in Guelph (454), followed by Barrie (550) and Ottawa (624).Note

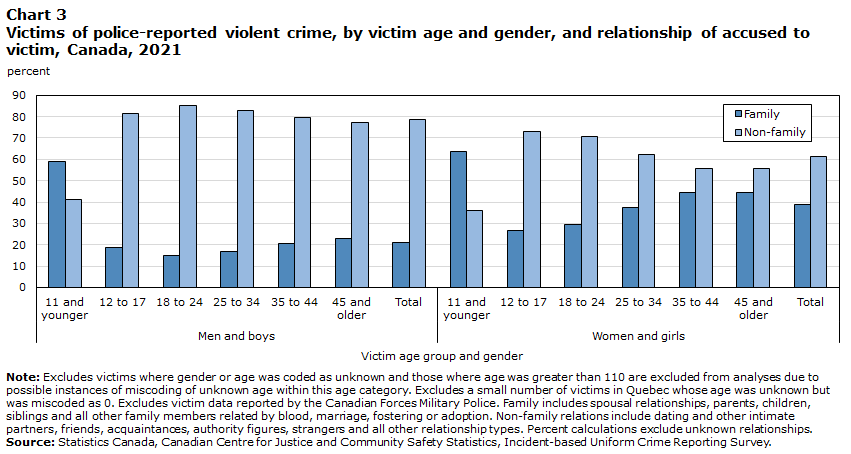

Most young boys victimized by a family member, older boys and men by a casual acquaintance or stranger

In 2021, of those whose violent victimization was reported to police, eight in ten (79%) men and boys were victimized by someone outside their family compared to about six in ten (61%) women and girls (Chart 3). The largest proportion of males who were victimized by a family member were aged 11 and younger (59%), of whom, three quarters (75%) were victimized by a parent.Note However, with increasing age, and as individuals’ social networks begin to extend beyond family, proportionately more males were victimized by someone outside of their family. This finding reflects a longstanding trend, even throughout the pandemic whereby lockdown restrictions meant people spent an increased amount of time in the home, oftentimes with family.

Chart 3 start

Data table for Chart 3

| Victim age group and gender | Family | Non-family | |

|---|---|---|---|

| percent | |||

| Men and boys | 11 and younger | 59 | 41 |

| 12 to 17 | 19 | 81 | |

| 18 to 24 | 15 | 85 | |

| 25 to 34 | 17 | 83 | |

| 35 to 44 | 20 | 80 | |

| 45 and older | 23 | 77 | |

| Total | 21 | 79 | |

| Women and girls | 11 and younger | 64 | 36 |

| 12 to 17 | 27 | 73 | |

| 18 to 24 | 29 | 71 | |

| 25 to 34 | 38 | 62 | |

| 35 to 44 | 45 | 55 | |

| 45 and older | 44 | 56 | |

| Total | 39 | 61 | |

|

Note: Excludes victims where gender or age was coded as unknown and those where age was greater than 110 are excluded from analyses due to possible instances of miscoding of unknown age within this age category. Excludes a small number of victims in Quebec whose age was unknown but was miscoded as 0. Excludes victim data reported by the Canadian Forces Military Police. Family includes spousal relationships, parents, children, siblings and all other family members related by blood, marriage, fostering or adoption. Non-family relations include dating and other intimate partners, friends, acquaintances, authority figures, strangers and all other relationship types. Percent calculations exclude unknown relationships.

Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics, Incident-based Uniform Crime Reporting Survey. |

|||

Chart 3 end

Boys aged 12 to 17 were most commonly victimized by a casual acquaintance (39%), followed by a stranger (28%). From age 18 onwards, the largest proportion of men within each age group were victimized by a stranger. Specifically, about four in ten (42%) men aged 18 to 24 were victimized by a stranger, followed by those aged 25 to 34 (37%). Equal proportions of men aged 35 to 44 (33%) and 45 and older (33%) were victimized by a stranger.

In contrast, most women and girls experienced victimization by a family member or intimate partner with proportions ranging from 41% to 64% depending on the age group.

Start of text box 4

Text box 4

Male victims of intimate partner violence

While intimate partner violence (IPV) is recognized as a gendered crime, affecting females disproportionately, men are not immune to experiencing such violence. IPV has varying definitions but commonly includes acts of physical, psychological, financial or sexual violence between current or former intimate partners who may or may not live together (Conroy, 2021b; Cotter, 2021b).

Victimization surveys in Canada have consistently shown small, albeit statistically significant, differences in the proportion of men and women who experience IPV (see Conroy, 2021a; Cotter, 2021b). Gender differences are much more apparent in police-reported data due to reporting practices. Specifically, only a fraction of victims of IPV say the violence they experienced came to the attention of the authorities and, of those who did, most were female (Conroy, 2021a).Note Indeed, prior research has revealed substantial gender differences in reporting IPV: for every ten female victims who contact police, one male victim will do so (Dutton, 2012).Note

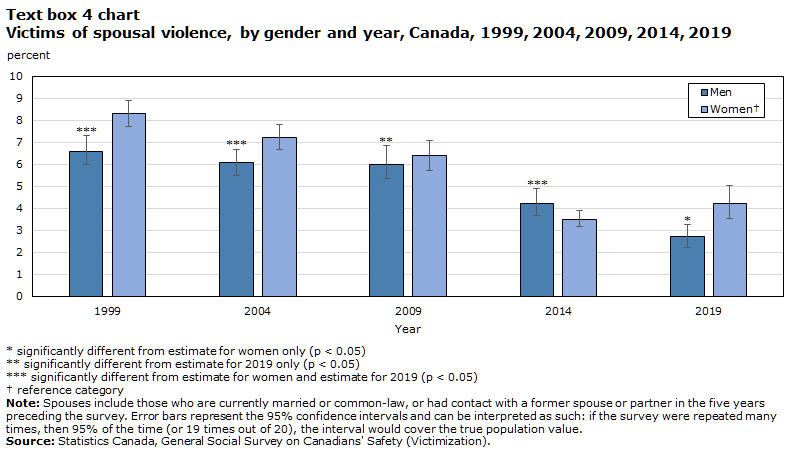

For 20 years, the General Social Survey on Canadians’ Safety (Victimization) has captured information related to spousal violence—a subset of IPV—occurring within the five years preceding each survey cycle (i.e., 1999, 2004, 2009, 2014 and 2019).Note Over time, proportions of spousal violence have been somewhat different between men and women. While proportions were relatively low across genders, significantly more women reported experiencing spousal violence in each year, with the exception of 2014 where the proportion was higher among men and in 2009 where there was no significant difference between genders (Text box 4 chart).

Text box 4 chart start

Data table for Text box 4 chart

| Year | Men | WomenData table for Text box 4 chart Note † | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| percent who experienced violent victimization by spouse | 95% confidence interval | percent who experienced violent victimization by spouse | 95% confidence interval | |||

| from | to | from | to | |||

| 1999 | 6.6Note *** | 6.0 | 7.3 | 8.3 | 7.7 | 8.9 |

| 2004 | 6.1Note *** | 5.5 | 6.7 | 7.2 | 6.7 | 7.8 |

| 2009 | 6.0Note ** | 5.3 | 6.8 | 6.4 | 5.7 | 7.1 |

| 2014 | 4.2Note *** | 3.7 | 4.9 | 3.5 | 3.2 | 3.9 |

| 2019 | 2.7Note * | 2.2 | 3.3 | 4.2 | 3.5 | 5.0 |

Source: Statistics Canada, General Social Survey on Canadians' Safety (Victimization). |

||||||

Text box 4 chart end

Notwithstanding overall declines in IPV noted for both genders since 1999, it is important to note that just under 1 in 30 men in Canada have experienced IPV in the five years preceding the 2019 survey. Moreover, men rarely seek formal assistance following IPV victimization (Burczycka, 2016; Cotter, 2021b; Cotter & Savage, 2019; Lysova & Dim, 2022; Roebuck et al., 2020). When they do, many report experiencing barriers ranging from inconsistent police response, to biases in the court processes and risk assessment tools to a lack of services tailored to address men’s experiences with violence (Dim & Lysova, 2021; Roebuck et al., 2020). The removal of such barriers is a critical step towards ensuring equity between genders when addressing IPV in Canada.

End of text box 4

Young boys most commonly experience victimization on private property, proportions decrease with age

In 2021, according to UCR data, more than two-thirds (68%) of all boys aged 11 and younger were victimized on private property – including houses, dwelling units and other structures located on private property (Table 5). However, as age increases, proportionately fewer males were victimized at such locations. Rather, sizeable proportions of men experienced violence in outdoor and commercial locations, especially those aged 18 to 24 (49%). In contrast, the largest proportion of females, regardless of age, were victimized on private property. These findings align with previous research using self-reported data whereby men were more likely than women to be victimized outside the home (Cotter & Savage, 2019; Perreault, 2020).

It may be that the location of victimization aligns with the relationships shared between victims and accused alongside lifestyle and leisure activities. For instance, the largest proportion of men aged 18 to 24 were victimized by a stranger. Of these stranger victimizations, 75% were victimized at a school, outdoor or commercial location.Note This contrasts with men who were victimized by a casual acquaintance, whereby more than half (53%) of those aged 18 to 24 were victimized on private property.

In support of the above, the majority (59%) of men aged 18 to 24 were victimized in the evening and nighttime hours (Table 5). Research has shown a correlation between violent victimization and nighttime activities, especially among males, where nighttime activities help to explain the relationship between age and victimization (Bunch et al., 2015). Specifically, younger people may participate in nighttime activities—such as going to work, school, clubs, bars or restaurants—at a greater frequency than their older counterparts, thus increasing the risk of victimization (Cotter, 2021a). In contrast, the largest proportion of boys aged 11 and younger, and those aged 12 to 17, were victimized in the morning and afternoon (64% and 57%, respectively).

Four in ten males sustained a physical injury as a result of the violent victimization

In 2021, according to UCR data, physical force was used against half (51%) of all male victims (Table 5). An additional 30% of males experienced victimization where a weapon was present, double what was documented among female victims (15%). Broken down by age, the presence of a weapon was least common among boys aged 11 and younger (20%) and most commonly reported among male victims aged 18 to 24 (35%), followed closely by those aged 25 to 34 (33%) and men aged 35 to 44 (32%).

Four in ten (40%) males sustained a physical injury as a result of the violent victimization, compared with 37% of females. Looking at variation across age groups, injury was least common among boys aged 11 and younger (35%) and was most common among men aged 25 to 34 (43%). Of all men and boys who sustained an injury, nine in ten (91%) had a minor injury and the remaining 9% had a major injury.

Charges laid or recommended against two-thirds of persons accused of victimizing men and boys

According to UCR data, in 2021, four in ten (43%) incidents of violent victimization against male victims were not cleared—meaning the incident was still under investigation, there was insufficient evidence to proceed or an accused had not been identified—compared to over one-third (37%) of incidents involving female victims.Note This difference could be related to incident characteristics, as males were more often victimized by a stranger, potentially increasing the difficulty in identifying and subsequently laying charges against an accused. For instance, one-third (34%) of all male victims were victimized by a stranger and, of incidents involving stranger victimization, more than half (56%) were not cleared.

That said, there were 74,648 police-reported incidents of violence against men and boys in which there was a single victim and single accused person.Note Of these incidents, and aligned with patterns noted above, about half involved the victimization of men and boys by an acquaintance (24%) or a stranger (24%). Women and girls, on the other hand, were most commonly victimized by an intimate partner or family member (70%).

Among persons accused of victimizing men and boys, two-thirds (66%) had charges laid or recommended against them. Charges were most common among persons accused of violence against men aged 25 to 34 (71%) and 35 to 44 (70%). Charges were least common among persons accused of victimizing male youth aged 12 to 17 (50%).

Start of text box 5

Text box 5

Perceptions of safety and confidence in the police among men

The 2019 General Social Survey on Canadians’ Safety (Victimization) included questions designed to capture people’s perceptions of their personal safety and confidence in the police. In general, a significantly larger proportion of men indicated they were very or somewhat satisfied with their personal safety from crime compared to women (82% versus 74%). The same was true when examining questions related to personal safety using behavioural indicators. For instance, a larger proportion of men compared to women reported feeling very or reasonably safe from crime when walking alone in their neighbourhood after dark (92% versus 83%), were not at all worried about using or waiting for public transit alone after dark (65% versus 40%) and were not at all worried about their safety from crime when home alone in the evening after dark (88% versus 76%).Note About one-fifth (21%) of Canadians indicated they had taken measures to protect themselves or their property from crime in the 12 months prior to the survey, where more women than men had indicated doing so (23% versus 19%).Note Despite men reporting greater satisfaction with their personal safety from crime than women, a slightly larger proportion indicated they had not very much or no confidence in the local police service (10% versus 9%).

Focusing on men exclusively, of those who had experienced violent victimization, a smaller proportion reported being very or somewhat satisfied with their personal safety from crime compared to men who had not been victimized (70% versus 82%). Similarly, men who had experienced violent victimization more commonly reported being very or somewhat worried about their personal safety while using or waiting for public transit alone after dark compared to men who had not been victimized (53%E versus 34%). They were also more likely to have taken measures to protect themselves or their property from crime in the 12 months preceding the survey (30% versus 19% of men who had not been victimized). Finally, a significantly larger proportion of men who had experienced victimization reported having not very much or no confidence in police compared to those who had not been victimized (21% versus 10%).

End of text box 5

Section 2: Homicide of men and boys

Increase in homicide rate involving male victims

In 2021, 586 men and boys were victims of homicide in Canada. The homicide rate among men and boys was 3.08 per 100,000 male population, almost unchanged from the previous year (3.04) but more than three times the homicide rate for women and girls (1.02) (Table 6). Broken down by age group, and consistent with prior trends, the highest homicide rate was documented among men aged 18 to 24 (6.72) (Chart 4). These findings are consistent with global trends showing that the male homicide rate in general is far higher than that of females and often peaks in young adulthood (UNODC, 2019b).

Chart 4 start

Data table for Chart 4

| Year | 17 and younger | 18 to 24 | 25 and older | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| rate per 100,000 population | ||||

| 2011 | 1.01 | 6.31 | 2.44 | 2.52 |

| 2012 | 0.76 | 4.43 | 2.43 | 2.28 |

| 2013 | 0.84 | 4.38 | 2.09 | 2.06 |

| 2014 | 0.73 | 4.36 | 2.20 | 2.11 |

| 2015 | 0.87 | 4.41 | 2.61 | 2.43 |

| 2016 | 0.72 | 5.97 | 2.65 | 2.57 |

| 2017 | 0.77 | 6.45 | 2.77 | 2.71 |

| 2018 | 0.68 | 5.64 | 2.84 | 2.67 |

| 2019 | 0.92 | 6.08 | 2.91 | 2.82 |

| 2020 | 1.32 | 5.93 | 3.14 | 3.04 |

| 2021 | 0.87 | 6.72 | 3.23 | 3.08 |

|

Note: There may be a small number of homicides included in a given year's total that occurred in previous years. Homicides are counted according to the year in which they are reported to Statistics Canada. Rates are calculated on the basis of 100,000 population. Populations are based on July 1 estimates from Statistics Canada, Centre for Demography. Excludes victims where gender or age was coded as unknown. Includes solved and unsolved homicide (i.e., homicides with and without a known accused). Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics, Homicide Survey. |

||||

Chart 4 end

Between 2011 and 2021, the homicide rate among men and boys has increased (+22%), driven largely by the homicide of men aged 25 and older (+32%). A similar pattern is evident when examining the change in rates since 2016. The homicide rate among men and boys as victims increased by 20%, with the most substantial increases documented among men aged 25 and older (+22%) and boys aged 17 and younger (+20%).

Males aged 12 and older most commonly killed by a non-family member

Aligned with global patterns (UNODC, 2019a), between 2011 and 2021, the large majority (87%) of homicide victims aged 11 and younger were killed by a family member (Table 7). From age 12 and onward, however, on average 83% of male homicide victims aged 12 to 17, 18 to 24 and 25 and older were killed by someone outside of their family, most commonly by a friend, stranger or acquaintance. More specifically, male youth victims aged 12 to 17 were most often killed by a friend (41%), followed by a stranger (20%) or an acquaintance (19%). A similar pattern was observed among men aged 18 to 24, albeit with slightly higher proportions (44%, 25% and 22%, respectively). Lastly, of male homicide victims aged 25 and older, the largest proportion was again killed by a friend (34%), followed by an acquaintance (25%) and a stranger (20%).

Four in ten male homicide victims died by shooting

Overall, between 2011 and 2021, shooting was the most common primary method used to cause the death of men and boys (40%), almost double what was documented for women and girls (22%) (Table 8). The method used to cause death among men and boys, however, varied by victim age. For instance, the largest proportion of boys aged 11 and younger died by beating (36%), whereas stabbing was the most common method used to kill male youth aged 12 to 17 (44%). For adult victims, shooting was the most common method of killing for male victims aged 18 to 24 and for those aged 25 and older (54% and 37%, respectively). Recent Canadian data illustrates the gendered nature of gang-related homicides and the predominance of firearms in carrying them out, which can help explain the high proportion of young men dying in firearm-related homicides (see Cotter, 2022; David & Jaffray, 2022).

Start of text box 6

Text box 6

Victimization of Indigenous men and boys in Canada

Canadian research has consistently shown how rates of violent victimization are higher among Indigenous (First Nations people, Métis and Inuit) compared to non-Indigenous people (Boyce, 2016; Heidinger, 2021; Heidinger, 2022; Perreault, 2022). With the exception of homicide, however, police-reported data on the Indigenous identity of victims or persons accused of a violent crime is not reliably recorded within and across police services in Canada. As part of Statistics Canada’s Disaggregated Data Action Plan, a new initiative will improve data collection on the racialized identity of all victims and accused persons who are involved in criminal incidents as reported through the Uniform Crime Reporting Survey (see Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics, 2022). Such an initiative is crucial to enhance understanding of the experiences and interactions First Nations people, Métis and Inuit have with police and the Canadian justice system.

The overrepresentation of Indigenous people as victims and persons accused of crime in Canada has been linked to historical and ongoing colonialism and its associated laws and policies (Department of Justice, 2022; Heidinger, 2022; Perreault, 2022). Specifically, policies such as the residential school system, the Sixties Scoop and current child welfare practices which remove children from their families thereby contributing to the overrepresentation of Indigenous children in the child welfare system, affect the relationships many Indigenous people have with each other and the broader community. The impacts of these policies are overwhelmingly negative and far reaching. For example, living with intergenerational trauma resulting from residential school experiences has contributed to high rates of mental health issues, suicide, substance use, child maltreatment and family violence among the Indigenous populations (Menzies, 2020).

To illustrate, according to the 2019 General Social Survey on Canadians’ Safety (Victimization), Indigenous people were more likely to have reported experiencing harsh parenting and childhood sexual or physical violence, bared witness to parental violence and been under the legal responsibility of the government compared to non-Indigenous people (Perreault, 2022). Indigenous men were also twice as likely as non-Indigenous men to have been victims of at least one violent crime in the 12 months preceding the survey (Perreault, 2022). Homicide data are even more illuminating. For example, despite comprising about 5% of the Canadian population (Statistics Canada, 2022b), in 2021, one-quarter (25%) of all homicide victims were Indigenous, representing a rate six times higher than non-Indigenous people (9.17 victims per 100,000 Indigenous people versus 1.55 victims per 100,000 non-Indigenous people) (David & Jaffray, 2022). Indeed, focusing on Indigenous males exclusively, between 2011 and 2021, 30% of all male homicide victims aged 17 and younger were Indigenous and about one quarter (24%) of male victims aged 18 and older were Indigenous.

End of text box 6

Summary

In 2021, there were 192,413 male victims of police-reported crime in Canada, representing a rate of 1,015 victims per 100,000 male population and accounting for just under half (46%) of all victims of violent crime. The rate of violent victimization increased steadily for boys and men, peaking between the ages of 25 and 29, before declining with increasing age.

While the overall rate of police-reported victimization was higher among women and girls compared to men and boys (1,190 versus 1,015 per 100,000 population), men and boys experienced higher rates of many more severe forms of victimization, such as homicide, other violations causing death and attempted murder, assault level 2, robbery, assault level 3 and extortion.

Consistent with previous Canadian trends, the highest rate of victimization against men and boys was reported by police in the territories, followed by Manitoba and Saskatchewan. For boys aged 11 and younger, however, the highest rate of violence was in Newfoundland and Labrador and for male youth aged 12 to 17, police in New Brunswick reported the highest rate.

In 2021, the overall rate of police-reported violence against men and boys was higher in rural compared to urban areas (1,438 versus 936 per 100,000 male population). The high rates of rural violence were due largely to victimization rates reported in the rural North, which were about three times higher than rates in the rural South.

With the exception of boys aged 11 and younger, the largest proportion of males were victimized by someone outside the family, oftentimes by a casual acquaintance or a stranger. Physical force was used against half (51%) of all male victims and an additional 30% experienced victimization with a weapon present, double what was documented among female victims (15%). Four in ten (40%) males sustained a physical injury as a result of the violent victimization.

In 2021, the homicide rate among men and boys was more than three times higher than the homicide rate for women and girls (3.08 versus 1.02 victims per 100,000 population). Between 2011 and 2021, the homicide rate among men and boys has increased (+22%), driven largely by the homicide of men aged 25 and older (+32%). From age 12 and onward, most male homicide victims were killed by someone outside of their family.

Previously, police-reported data related to the violent victimization of men and boys were used as a point of comparison when examining violence against women and girls. While victimization rates are similar across genders overall, important differences—such as the type of victimization experienced, at what age and by whom—are often concealed. Highlighting such nuances is an important step towards ensuring gender equity when addressing violent victimization in Canada.

Detailed data tables

Table 6 Victims of homicide, by victim age group and gender, and year, Canada, 2011 to 2021

Survey description

General Social Survey on Canadians’ Safety (Victimization)

This article uses data from the General Social Survey (GSS) on Canadians’ Safety (Victimization). In 2019, Statistics Canada conducted the GSS on Victimization for the seventh time. Previous cycles were conducted in 1988, 1993, 1999, 2004, 2009 and 2014. The main objective of the GSS on Victimization is to better understand issues related to the safety and security of Canadians, including perceptions of crime and the justice system, experiences of intimate partner violence, and how safe people feel in their communities.

The target population was persons aged 15 and older living in the provinces and territories, except for those living full-time in institutions.

Data collection took place between April 2019 and March 2020. Responses were obtained by computer-assisted telephone interviews, in-person interviews (in the territories only) and, for the first time, the GSS on Victimization offered a self-administered internet collection option to survey respondents in the provinces and in the territorial capitals. Respondents were able to respond in the official language of their choice.

An individual aged 15 or older was selected within each sampled household to respond to the survey. An oversample of Indigenous people was added to the 2019 GSS on Victimization to allow for a more detailed analysis of individuals belonging to this population group. In 2019, the final sample size was 22,412 respondents.

In 2019, the overall response rate was 37.6%. Non-respondents included people who refused to participate, could not be reached, or could not speak English or French. Respondents in the sample were weighted so that their responses represent the non-institutionalized Canadian population aged 15 and older.

For the quality of estimates, the lower and upper bounds of the confidence intervals are presented in charts and tables. Confidence intervals should be interpreted as follows: if the survey were repeated many times, then 95% of the time (or 19 times out of 20), the confidence interval would cover the true population value.

Incident-based Uniform Crime Reporting Survey

The Incident-based Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR) Survey collects detailed information on criminal incidents that have come to the attention of police services in Canada. Information includes characteristics of victims, accused persons and incidents. In 2021, data from police services covered 99% of the population of Canada.

One incident can involve multiple offences. In order to ensure comparability, counts are presented based on the most serious offence related to the incident as determined by a standard classification rule used by all police services.

Victim age is calculated based on the end date of an incident, as reported by the police. Some victims experience violence over a period of time, sometimes years, all of which may be considered by the police to be part of one continuous incident. Information about the number and dates of individual incidents for these victims of continuous violence is not available. Excludes victims where age was greater than 110 due to possible instances of miscoding of unknown age within this age group.

The option for police to code victims as “gender diverse” in the UCR Survey was implemented in 2018. In the context of the UCR, “gender diverse” refers to a person who publicly expresses as neither exclusively male nor exclusively female. Given that small counts of victims identified as being gender diverse may exist, the UCR data available to the public has been recoded with these victims distributed in the “male” or “female” categories based on the regional distribution of victims’ gender. This recoding ensures the protection of confidentiality and privacy of victims.

Homicide Survey

The Homicide Survey collects detailed information on all homicide that has come to the attention of, and have been substantiated by, police services in Canada. Information includes characteristics of victims, accused persons and incidents. In 2019, the survey went through a comprehensive redesign in order to improve data quality and enhance relevance.

Prior to 2019, Homicide Survey data was presented by the sex of the victims. Sex and gender refer to two different concepts. Caution should be exercised when comparing counts for sex with those for gender. Given that small counts of victims and accused persons identified as “gender diverse” may exist, the aggregate Homicide Survey data available to the public has been recoded to assign these counts to either “male” or “female” in order to ensure the protection of confidentiality and privacy. Victims and accused persons identified as gender diverse have been distributed to either the male or female category based on the regional distribution of victims’ or accused persons’ gender.

References

Allen, M., & McCarthy, K. (2018). Victims of police-reported violent crime in Canada: National, provincial and territorial fact sheets, 2016. Juristat. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 85-002-X.

Bosick, S.J., Rennison, C.M., Gover, A.R., & Dodge, M. (2012). Reporting violence to the police: Predictors through the life course. Journal of Criminal Justice, 40(6), 441-451.

Boyce, J. (2016). Victimization of Aboriginal people in Canada, 2014. Juristat. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 85-002-X.

Bunch, J., Clay-Warner, J., & Lei, M. (2015). Demographic characteristics and victimization risk: Testing the mediating effects of routine activities. Crime & Delinquency, 61(9), 1181-1205.

Burczycka, M. (2016). Trends in self-reported spousal violence in Canada, 2014. In Family violence in Canada: A statistical profile, 2014. Juristat. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 85-002-X.

Campagna, L., & Zaykowski, H. (2020). Health consequences and help-seeking among victims of crime: An examination of sex differences. International Review of Victimology, 26(2), 181-195.

Canadian Centre for Child Protection. (2022a). Boys aggressively targeted on Instagram and Snapchat, analysis of Cybertip.ca data shows.

Canadian Centre for Child Protection. (2022b). Online harms: Sextortion.

Canadian Centre for Child Protection. (2021). Further rise in the sextortion of male teens.

Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics. (2022). Police-reported Indigenous and racialized identity statistics via the Uniform Crime Reporting Survey. Statistics Canada.

Coker, A.L., Davis, K.E., Arias, I., Desai, S., Sanderson, M., Brandt, H.M., & Smith, P.H. (2002). Physical and mental health effects of intimate partner violence for men and women. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 23(4), 260-268.

Conroy, S. (2021a). Spousal violence in Canada, 2019. Juristat. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 85-002-X.

Conroy, S. (2021b). Family violence in Canada: A statistical profile, 2019. Juristat. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 85-002-X.

Conroy, S. (2018). Police-reported violence against girls and young women in Canada, 2017. Juristat. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 85-002-X.

Cotter, A. (2022). Firearms and violent crime in Canada, 2021. Juristat Bulletin – Quick Fact. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 85-002-X.

Cotter, A. (2021a). Criminal victimization in Canada, 2019. Juristat. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 85-002-X.

Cotter, A. (2021b). Intimate partner violence in Canada, 2018: An overview. Juristat. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 85-002-X.

Cotter, A., & Savage, L. (2019). Gender-based violence and unwanted sexual behaviour in Canada, 2018: Initial findings from the Survey of Safety in Public and Private Spaces. Juristat. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 85-002-X.

David, J.-D., & Jaffray, B. (2022). Homicide in Canada, 2021. Juristat. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 85-002-X.

Department of Justice. (2022). Understanding the overrepresentation of Indigenous people in the criminal justice system.

Dim, E., & Lysova, A. (2021). Male victims’ experiences with and perceptions of the criminal justice response to intimate partner abuse. Journal of interpersonal violence, 37(15-16), 1-25.

Dowling, C., Morgan, A., Boyd, C., & Voce, I. (2018). Policing domestic violence: A review of the evidence. Australian Institute of Criminology.

Dutton, D.G. (2012). The case against the role of gender in intimate partner violence. Aggression & Violent Behavior, 17(1), 99-104.

Felson, R.B. (2002). Violence and gender re-examined. American Psychological Association.

Heidinger, L. (2022). Violent victimization and perceptions of safety: Experiences of First Nations, Métis and Inuit women in Canada. Juristat. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 85-002-X.

Heidinger, L. (2021). Intimate partner violence: Experiences of First Nations, Métis and Inuit women in Canada, 2018. Juristat. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 85-002-X.

Kelsay, J.D., Skubak Tillyer, M., Tillyer, R., & Ward, J.T. (2017). The violent victimization of children, adolescents, adults, and the elderly: Situational characteristics and victim injury. Violence and victims, 32(2), 342-361.

Lauritsen, J.L., & Carbone-Lopez, K. (2011). Gender differences in risk factors for violent victimization: An examination of individual-, family-, and community-level predictors. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 48(4), 538-565.

Lysova, A., & Dim, E.E. (2022). Severity of victimization and formal help seeking among men who experienced intimate partner violence in their ongoing relationships. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 37(3-4), 1404-1429.

Menzies, P. (2020). Intergenerational trauma and residential schools. The Canadian Encyclopedia.

Mercy, J.A., Hillis, S.D., Butchart, A., Bellis, M.A., Ward, C.L., Fang, X., & Rosenberg, M.L. (2017). Interpersonal violence: Global impact and paths to prevention. In C.L. Ward, R. Nugent, O. Kobusingye & K.R. Smith (Eds.), Injury prevention and environmental health, 3rd edition.

Moreau, G. (2022). Police-reported crime statistics in Canada, 2021. Juristat. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 85-002-X.

Patchin, J.W., & Hinduja, S. (2020). Sextortion among adolescents: Results from a national survey of U.S. youth. Sexual abuse, 32(1), 30-54.

Perreault, S. (2022). Victimization of First Nations people, Métis and Inuit in Canada. Juristat. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 85-002-X.

Perreault, S. (2020). Gender-based violence: Sexual and physical assault in Canada’s territories, 2018. Juristat. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 85-002-X.

Perreault, S. (2019). Police-reported crime in rural and urban areas in the Canadian provinces, 2017. Juristat. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 85-002-X.

Perreault, S., & Simpson, L. (2016). Criminal victimization in the territories, 2014. Juristat. Statistics Canada catalogue no. 85-002-X.

Public Safety Canada. (2021). Government of Canada awareness campaign addresses growing risk of online child sexual exploitation.

Roebuck, B., McGlinchey, D., Hastie, K., Taylor, M., Roebuck, M., Bhele, S., Hudson, E., & Xavier, R.G. (2020). Male survivors of intimate partner violence in Canada. Victimology Research Centre, ON: Algonquin College.

Statistics Canada. (2022a). Table 35-10-0050-01 Victims of police-reported violent crime and traffic violations causing bodily harm or death, by gender of victim and type of violation. [Data table].

Statistics Canada. (2022b). Indigenous population continues to grow and is much younger than the non-Indigenous population, although the pace of growth has slowed. The Daily. Statistics Canada catalogue no. 11-001-X.

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). (2019a). Global study on homicide: Killing of children and young adults.

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). (2019b). Global study on homicide: Understanding homicide.

Warnken, H., & Lauritsen, J.L. (2019). Who experiences violent victimization and who accesses services: Findings from the National Crime Victimization Survey for expanding our reach. Center for Victim Research.

Wolak, J., Finkelhor, D., Walsh, W., & Treitman, L. (2018). Sextortion of minors: Characteristics and dynamics. Journal of Adolescent Health, 62(1), 72-79.

- Date modified: