Canadian residential facilities for victims of abuse, 2020/2021

by Dyna Ibrahim

Highlights

- In 2020/2021, there were 557 residential facilities across Canada that were primarily mandated to serve victims of abuse: 78% were short-term facilities with a general mandate of providing accommodations for less than three months, and 22% were long-term facilities which typically can provide accommodations for three months or more.

- The unprecedented impact of the COVID-19 pandemic was recounted across many facilities: about one in three (34%) facilities reported being impacted to a great extent by the pandemic, overall, while more than four in ten (44%) facilities were impacted to a moderate extent. The level of impact varied throughout the pandemic, with the period of initial lockdowns enforced at the beginning of the pandemic being the most challenging time.

- Accommodation capacity was the greatest pandemic-related challenge faced by shelters. Just under half (47%) of facilities reported that their accommodation capacity was impacted to a great extent. This was of particular concern for shelters in Ontario (61%) and Quebec (60%).

- Close to half (49%) of residential facilities for victims of abuse reported increases in the number of crisis calls received since the start of the pandemic, while more than half (53%) saw an increase in demand for support or services for victims outside their facilities. Compared to before the pandemic, demand for admissions more often declined or remained about the same.

- In total, residential facilities for victims of abuse admitted just under 47,000 people in 2020/2021, much lower (-31%) than reported in 2017/2018, when data was last collected.

- On the snapshot date of April 14, 2021, there were 5,466 people living in residential facilities for victims of abuse: more than half (54%) were adult women, and just over four in ten (44%) were children accompanying adults in the facilities.

- A large majority (84%) of the 2,749 women residing in the facilities for reasons of abuse on the snapshot day were escaping intimate partner violence; most often, the abuser was a current common-law partner (38%) or spouse (25%). Seven in ten (70%) women residents were living with their abuser prior to seeking shelter.

- Relative to their representation in the Canadian population, First Nations, Métis and Inuit women, non-permanent resident women, and women who could not speak English or French were overrepresented in residential facilities for victims of abuse on the snapshot day.

- Just over half (53%) of the beds in short-term facilities were occupied on the snapshot day, and about one in seven (15%) short-term facilities were full. Nevertheless, a total of 487 people were turned away from facilities that day, most commonly because the facility was considered at capacity—the reason associated with 71% of women being turned away.

- Among women who left residential facilities for victims of abuse on the snapshot day and where destination information was provided, three in ten (30%) returned to a home where the abuser was. Smaller but equal proportions of women returned home where the abuser did not reside, or left to live with friends or relatives (12% each).

- The large majority (81%) of facilities reported that a lack of affordable and appropriate long-term housing was one of the top issues facing their residents.

Supports availed to people at risk or victims of crime can help them escape their violent situations and help survivors to cope with the aftermath of their experiences. These supports come in many forms and from multiple sources including informal ones such as friends, family and colleagues, or from formal sources including victim services, mental health supports and sexual assault centres. For people experiencing intimate partner violence, the risk of homelessness and financial instability are of great concern when deciding to leave an abusive situation. In fact, intimate partner violence is a leading cause of homelessness among women (Maki 2021; Meyer 2016; Sullivan et al. 2019; Yakubovich and Maki 2021). Residential facilities for victims of abuse are a form of support that can help mitigate the risk of homelessness by providing victims of intimate partner violence a place to turn.

Research to date has noted that crises can exacerbate the factors known to increase the risk of violence and victimization and further negatively impact the health and well-being of victims (Centre for Research and Education on Violence against Women and Children 2021; Kaukinen 2020). Public health measures put in place throughout 2020 and 2021 to combat the COVID-19 pandemic resulted in Canadians spending more time at home. As a result of these measures, there were concerns that victims of domestic violence were now in situations where they were isolated at home with their abusers, and the financial impediments of the pandemic coupled with the mental health impacts of quarantine could lead to more violence in the home (Brooks et al. 2020; Evans et al. 2020; Humphreys et al. 2020; Ragavan et al. 2020). For example, the United Nations Population Fund (2020) had estimated that for every three months of lockdown extensions, there would be at least 15 million more domestic violence cases globally. According to research from early stages of the pandemic, one in ten (10%) Canadian women were very or extremely concerned about the possibility of violence in the home (Statistics Canada 2020). Further, earlier reports found that the pandemic created additional barriers for victims of domestic violence. Specifically, there was a reluctance for victims to seek help due to fears of contracting the virus while doing so, confusion over the impact of business closures and distancing protocols on shelter accessibility, other challenges related to COVID-19 protocols, and a preoccupation with other stressors such job losses and school closures (Moffitt et al. 2020; Trudell and Whitmore 2020; Women’s Shelters Canada 2020).

Based on data from the second iteration of the Survey of Residential Facilities for Victims of Abuse (SRFVA), this article examines the availability and accessibility of residential supports for victims of abuse across Canada during 2020/2021. The SRFVA collects information on facility characteristics, the clients they serve, and the types of services available. This information is presented, along with funding information, expenses and the challenges faced by the facilities and their residents in 2020/2021.

Crime data collected from police records can provide a wealth of information on incidents that are reported to police. However, according to the General Social Survey on Canadians’ Safety (Victimization), only a fraction of victims report their victimization experiences to the police (Cotter 2021a). Information from the SRFVA can provide further insight on victimization that may not have been reported to police. Further, information collected through the SRFVA can provide advocates, service providers and funding partners with information regarding the specific needs of victims seeking shelter and how they can best be supported.

In order to ensure that data from Statistics Canada are relevant and timely, a new section containing several COVID-related questions were added to the SRFVA in an effort to measure the impact that the pandemic and corresponding lockdown restrictions were having on shelters across the country. Analysis based on these questions is also presented to enhance knowledge on how victims may be further impacted—directly and indirectly—by the pandemic, and to help inform decisions currently being made by policy makers, which can have a profound impact on the resources available to, and experiences of victims.

The 2020/2021 cycle of the SRFVA was conducted with funding support from the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation.

Start of text box 1

Text box 1

Defining residential facilities for victims of abuse

The term “residential facility” refers to any building, location or service that provides housing to individuals, regardless of the length of stay (days, months or years). The primary mandate of such a facility refers to the main activity or service provided. For example, many facilities will offer services or support to individuals who may have experienced abuse, however, they may not explicitly include this in their mandate. The Survey of Residential Facilities for Victims of Abuse (SRFVA) focuses on facilities whose primary mandate is to provide residential services to victims of abuse, as opposed to facilities primarily mandated to provide housing services to persons who may or may not have experienced abuse (e.g., homeless shelters). For facilities that primarily support victims of abuse, they may support other people in addition to their primary mandate.

For the SRFVA, respondents were asked to report the type of facility they operated based on the expected length of stay provided in their mandate, regardless of practice. They were grouped into two categories:

Short-term residential facilities include those with a general policy of providing accommodation for less than three months, and they typically provide individual beds to residents, as opposed to separate apartments or units. Short-term facilities include, for example, those considered to be transition homes, domestic violence shelters or private homes that are part of safe home networks.

Long-term residential facilities include those with a general policy of providing accommodation for three months or more, and they typically provide residential units (e.g., apartments or houses) to residents. Long-term facilities include, for example, second- and third-stage housing, which are typically more permanent supportive types of housing that follow short-term housing.

The usual operations of short-term and long-term facilities are such that short-term facilities act as front-line centres for initial intakes and may refer residents to long-term facilities. As such, short-term facilities often provide different services given the nature of their operations. For example, of those facilities reporting the general services provided by staff or volunteers at the facility, 97% of short-term facilities provide a crisis telephone line, compared to 42% of long-term facilities.Note Similarly, 84% of short-term facilities offer transportation services for medical appointments and court dates, compared to 55% of long-term facilities.

In this article, the terms “residential facilities for victims of abuse” and “shelters” are used interchangeably.

End of text box 1

Impact of COVID-19 on residential facilities for victims of abuse

According to the Survey of Residential Facilities for Victims of Abuse (SRFVA), on the survey’s snapshot date of April 14, 2021, there were 557 facilities operating in Canada whose primary mandate was to serve victims of abuse.Note About one in three (34%) facilities serving victims of abuse reported that, overall, the pandemic had impacted their ability to serve victims to a great extent, while more than four in ten (44%) indicated the impact overall was moderate (Table 1).Note However, similar to results published by Women’s Shelters Canada (2020), facilities were affected differently at various times throughout the pandemic, which is not surprising given government orders for lockdowns varied within and across provinces and territories.

Ontario and Quebec facilities report more overall impact

When asked about the overall effect of the pandemic since the start, facilities in Ontario (49%) and Quebec (42%) were most likely to report that COVID-19 impacted them to a great extent (Table 1).Note Facilities in Saskatchewan (8%), British Columbia (13%) and the Atlantic provinces (22%) were least likely to report a great extent of impact overall. Instead, facilities in these provinces more often indicated that the pandemic has had a moderate impact on them, overall.

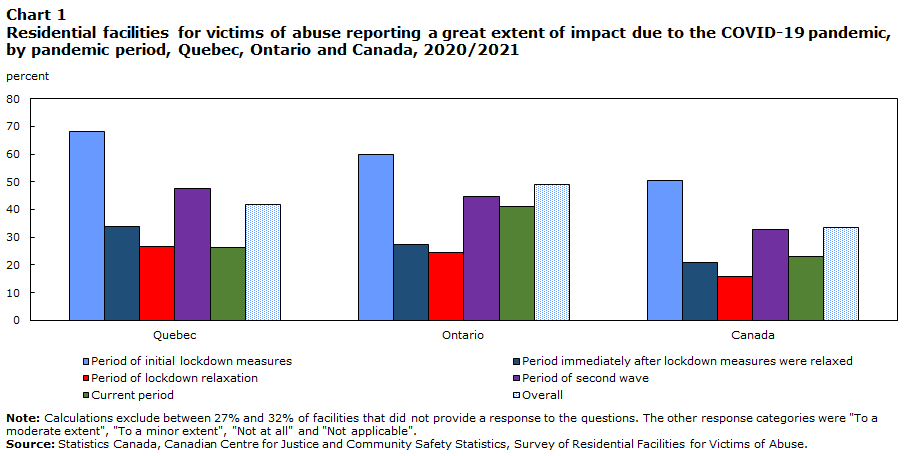

Measures implemented across the country to combat the pandemic followed different timelines in terms of when they were effected and when they were eased. The periods in which lockdown restrictions were imposed were the most impactful for shelters across Canada, particularly during the first wave of the pandemic. The impact reported during the initial lockdown period in Quebec and Ontario drove the national average. More specifically, 68% of facilities in Quebec and 60% of those in Ontario reported that during this time, they were impacted by the pandemic to a great extent (Table 1, Chart 1). Manitoba also reported a great impact that was above the national level (59% compared with 50%).

Chart 1 start

Data table for Chart 1

| Selected provinces | Period of initial lockdown measures | Period immediately after lockdown measures were relaxed | Period of lockdown relaxation | Period of second wave | Current period | Overall |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| percent | ||||||

| Quebec | 68 | 34 | 27 | 48 | 26 | 42 |

| Ontario | 60 | 27 | 24 | 45 | 41 | 49 |

| Canada | 50 | 21 | 16 | 33 | 23 | 34 |

|

Note: Calculations exclude between 27% and 32% of facilities that did not provide a response to the questions. The other response categories were "To a moderate extent", "To a minor extent", "Not at all" and "Not applicable". Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics, Survey of Residential Facilities for Victims of Abuse |

||||||

Chart 1 end

Similar results were seen in the second wave, but to a lesser degree. In Ontario (45%) and Quebec (48%), just under half of facilities reported being impacted to a great extent during this period of the pandemic.

More than a year after the onset of the pandemic (during the survey collection period of April to August 2021), the proportion of facilities in Quebec reporting a great impact had dropped to 26% compared to 23% in Canada overall.Note Instead, nearly half (45%) of Quebec facilities experienced minor impact or no impact at all. In contrast, 41% of facilities in Ontario reported that, at this point, the pandemic was continuing to have a great impact on their ability to continue serving victims of abuse. These differences may be reflective of the differences in measures put in place at this time in these provinces. For example, in Ontario, a province-wide stay-at-home order was declared in April 2021 that likely had an impact on facilities, while no such an order was enforced in Quebec during this period.

Accommodation capacity greatest pandemic-related challenge

Residential facilities for victims of abuse reported that the COVID-19 pandemic had affected their ability to provide services due to a number of challenges. Nearly half (47%) of facilities reported that the pandemic had a great impact on their ability to operate at full capacity due to physical distancing measures (Table 2). Maximum occupancy was reduced for shelters across Canada in order to meet public health regulations to limit the spread of the virus, with some shelters having to reduce their capacity by up to 50% or more (Women’s Shelters Canada 2020).

Capacity was particularly an issue in Ontario and Quebec, where 61% and 60% of facilities, respectively, reported that they were impacted to a great extent as a result of the pandemic. More than half (54%) of facilities in the territories also reported their accommodation capacity was impacted greatly by the pandemic. Half (50%) of Saskatchewan’s facilities also reported they were greatly impacted by accommodation capacity issues.

Among pandemic-related challenges faced by facilities, difficulties providing professional services or programs was also common as about one in three (31%) Canadian facilities reported experiencing a great impact. For example, professional services or programs such as legal services, addictions or substance use services, and counselling were reported to have been impacted greatly by the pandemic. This issue was of the greatest concern for facilities in Saskatchewan, where 50% reported that they were impacted to a great extent.

Some staffing-related issues were also reported by facilities. For example, about one in three reported that challenges related to hiring or training new staff (34%) and volunteer work (31%) were impacting them to a great extent, including experiences related to a shortage of volunteers and an inability to hire volunteers. Nearly one in five (19%) facilities reported that staff being restricted to work at one location only was impacting them to a great extent.

Other staffing issues such as reluctance or unavailability to work due to health concerns and mental health challenges (17%), self-isolation requirements (13%) and caregiving responsibilities (17%) were less commonly reported by facilities as causing a great extent of impact. About one in ten (9%) facilities were greatly impacted by staff shifting to working from home.

Crisis calls and demand for external supports increase

While residential facilities for victims of abuse have a general mandate to provide residential services to individuals seeking shelter, these facilities also offer additional victim supports such as counselling services and crisis lines. During the pandemic, about half (49%) of facilities indicated an increase in the number of crisis calls received (Chart 2).Note While the number of crisis calls remained about the same for some facilities, nearly one in six (17%) facilities reported a decrease.

Chart 2 start

Data table for Chart 2

| Demand for services | Increased | Remained about the same | Decreased |

|---|---|---|---|

| percent | |||

| Demand for admission for adults only | 32 | 33 | 29 |

| Demand for admission for adults and accompanying children | 25 | 36 | 34 |

| Number of crisis calls | 49 | 29 | 17 |

| Demand for support or services for victims outside facility | 53 | 29 | 12 |

| Use of text messaging or instant messaging to provide support or services to victims outside your facility | 55 | 20 | 1 |

| Use of email to provide support or services to victims outside your facility | 55 | 26 | 1 |

| Use of other methods of communication to provide support or services to victims outside your facility | 68 | 16 | 1 |

|

Note: Includes the response category "Not applicable". Calculations exclude between 27% and 28% of facilities that did not provide a response to the questions. Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics, Survey of Residential Facilities for Victims of Abuse. |

|||

Chart 2 end

In addition to the increase in crisis calls, demand for services outside the facilities also increased. For example, just over half (53%) of the facilities saw an increase in demand for support or services for victims outside the facility, including outreach services. Many facilities also expanded their services by supporting victims virtually outside the shelters through increasing the use of text or instant messaging (55%), email (55%) and other methods of communication such as video conferencing (68%).

According to the SRFVA, the increase in the number of crisis calls did not always translate to an increase in shelter admissions compared to pre-pandemic times. Less than one-third of facilities reported that demand for admissions for adults only (32%) and adults and accompanying children (25%) had increased. However, similar proportions indicated that demand for admissions remained unchanged. Some facilities reported decreases: 29% of facilities indicated that demand for admissions for adults only had decreased and 34% of facilities reported a decline in demand for admissions for families.

While these findings related to demand for admissions may be partly attributable to the accommodation capacity challenges cited by many facilities across Canada, they may also reflect the reality that some victims were unable to leave their homes to seek out support because their abusers were spending more time at home.

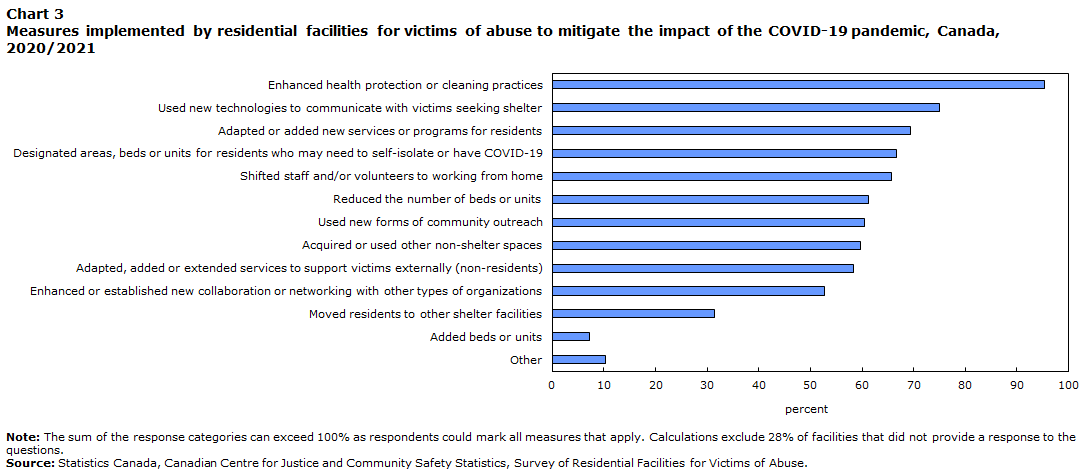

Facilities employ multiple measures to mitigate impact of the pandemic

In the face of the challenges and impact of restrictions imposed by the pandemic, residential facilities for victims of abuse implemented a variety of measures to allow them to continue serving victims while helping to reduce the risk of exposure to COVID-19. These measures included implementing better health protection practices, changing methods of daily operations and the way staff work, making physical changes in the facility and relying more on technology.

Enhanced health protection or cleaning practices was the most common measure put in place, reported by almost all (95%) facilities (Chart 3). Other commonly reported changes made to mitigate the impact of the pandemic on shelters included: using new technologies to communicate with victims (75%), adapting or adding new services or programs for residents (69%), designating self-isolation areas, beds or units (67%) and shifting staff or volunteers to working virtually (66%). Overall, six in ten (61%) facilities indicated that they had reduced the number of beds or units in their facilities.

Chart 3 start

Data table for Chart 3

| Type of measure | Percent |

|---|---|

| Enhanced health protection or cleaning practices | 95 |

| Used new technologies to communicate with victims seeking shelter | 75 |

| Adapted or added new services or programs for residents | 69 |

| Designated areas, beds or units for residents who may need to self-isolate or have COVID-19 | 67 |

| Shifted staff and/or volunteers to working from home | 66 |

| Reduced the number of beds or units | 61 |

| Used new forms of community outreach | 60 |

| Acquired or used other non-shelter spaces | 60 |

| Adapted, added or extended services to support victims externally (non-residents) | 58 |

| Enhanced or established new collaboration or networking with other types of organizations | 53 |

| Moved residents to other shelter facilities | 31 |

| Added beds or units | 7 |

| Other | 10 |

|

Note: The sum of the response categories can exceed 100% as respondents could mark all measures that apply. Calculations exclude 28% of facilities that did not provide a response to the questions. Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics, Survey of Residential Facilities for Victims of Abuse. |

|

Chart 3 end

Characteristics of facilities and residents

Majority of facilities serve women and their children only, few serve men, one in five serve adults of another gender

Residential facilities for victims of abuse typically have a general mandate or policy that governs their operations. Two-thirds (68%) of facilities reported that they were mandated to serve women and their children only and an additional 11% indicated they were mandated to serve women only.Note Note

No facilities reported being mandated to exclusively serve people of another gender. Nevertheless, 20% of facilities indicated that adults of another gender (e.g., not female or male) were among the population groups they were mandated to serve.Note In total, 24 facilities (or 4%) reported being mandated to serve men.Note Virtually all of these facilities were mandated to serve women as well.

Regardless of their mandate to serve specific population groups, about one in five (19%) facilities reported opening their doors to people other than those specified in their policies. For example, 8% of facilities reported admitting accompanying children to their facilities though their mandate only stipulates providing services to adults,Note and 5% of facilities admitted adults and accompanying children of another gender despite their mandates not specifying they serve such individuals.Note

In addition to the population groups that a facility may be mandated to serve, there are also specific types of victims who have experienced a particular kind of violence or abuse that a facility may be primarily mandated to serve. The vast majority (91%) of facilities in Canada were mandated to serve victims of various types of abuse. Spousal abuse was the most commonly reported type of abuse that facilities were mandated to serve, named by virtually all (99%) facilities responding to the SRFVA, followed by other intimate relationship abuse (88%) and other family abuse (77%). Many facilities also reported having a mandate to serve victims of senior abuse (64%) and abuse by an acquaintance or friend (56%). One in ten (10%) reported that other types of abuse are included in their mandates, beyond those indicated above or in the survey.

Less than one in ten (9%) facilities were mandated to serve victims of family violence only.Note One in five (20%) facilities were for intimate partner violence victims only.

The large majority (78%) of residential facilities for victims of abuse were short-term facilities, and the remaining 22% were long-term. While the types of services offered by residential facilities for victims of abuse differed between short- and long-term facilities (Table 3), there were no major differences between the mandates of the two in terms of the population groups served and types of abuse included.

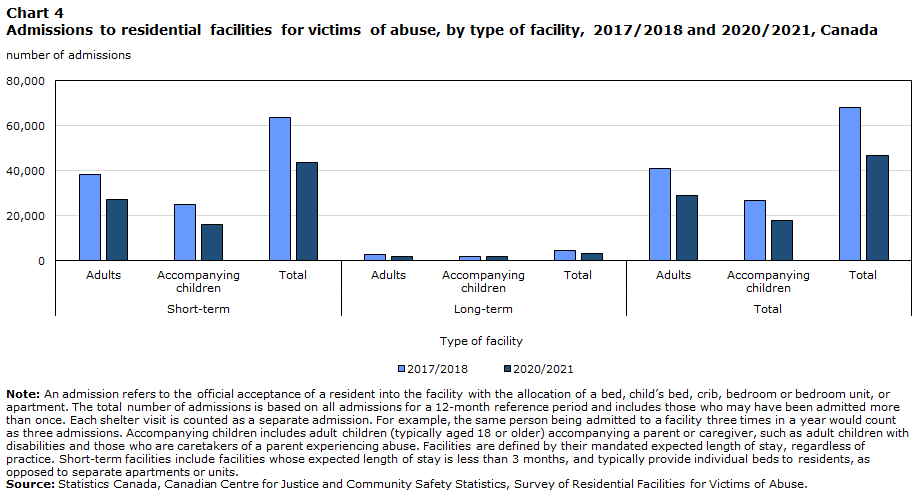

Total number of people admitted to residential facilities decreases in 2021/2022 while number of males admitted increases

In 2020/2021, residential facilities for victims of abuse admitted a total of 46,827 clients (Table 4). This number included 28,592 adult females, 223 adult males and 195 adults of another gender. Accompanying the adults who were admitted were 9,367 female children, 8,411 male children and 39 children of another gender.

The number of admissions reported in 2020/2021 was 31% lower compared to 2017/2018, when the SRFVA was last conducted (Chart 4).

Chart 4 start

Data table for Chart 4

| Type of facility | Type of resident | Number of admissions | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2017/2018 | 2020/2021 | ||

| Short-term | Adults | 38,460 | 27,271 |

| Accompanying children | 25,047 | 16,195 | |

| Total | 63,507 | 43,466 | |

| Long-term | Adults | 2,704 | 1,739 |

| Accompanying children | 1,895 | 1,622 | |

| Total | 4,599 | 3,361 | |

| Total | Adults | 41,164 | 29,010 |

| Accompanying children | 26,942 | 17,817 | |

| Total | 68,106 | 46,827 | |

|

Note: An admission refers to the official acceptance of a resident into the facility with the allocation of a bed, child’s bed, crib, bedroom or bedroom unit, or apartment. The total number of admissions is based on all admissions for a 12-month reference period and includes those who may have been admitted more than once. Each shelter visit is counted as a separate admission. For example, the same person being admitted to a facility three times in a year would count as three admissions. Accompanying children includes adult children (typically aged 18 or older) accompanying a parent or caregiver, such as adult children with disabilities and those who are caretakers of a parent experiencing abuse. Facilities are defined by their mandated expected length of stay, regardless of practice. Short-term facilities include facilities whose expected length of stay is less than 3 months, and typically provide individual beds to residents, as opposed to separate apartments or units. Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics, Survey of Residential Facilities for Victims of Abuse. |

|||

Chart 4 end

Although both the total number of adults and accompanying children had declined since the last cycle of the SRFVA, the decline in number of adult admissions was driven by the number of women admitted in 2020/2021 (-30%).Note In contrast, the number of men admitted had increased: there were 223 adult males admitted in 2020/2021 compared to 86 in 2017/2018. This difference is likely partly attributable to a slight increase in the number of facilities that serve men. Specifically, in 2020/2021, 24 facilities indicated that they were mandated to serve men, compared to 15 in the last survey cycle. In addition, 10 facilities reported that they had admitted men in the previous year even though their mandates did not include serving male victims of abuse, compared to 7 facilities stating the same in 2017/2018.

With the exception of Nunavut and the Yukon, where facilities reported an increase in the number of admissions compared to the last survey cycle (+38% and +11%, respectively), all other provinces and the Northwest Territories reported decreases in admissions. Facilities in the Northwest Territories saw the largest drop in admissions, reporting less than half of the number of admissions than in the previous cycle (333 versus 740 people). Among the provinces, Alberta (-41%) reported the largest decline in the number of admissions, followed by British Columbia (-38%) and Newfoundland and Labrador (-37%). Ontario and Quebec, which had the highest number of facilities and admissions, also reported 29% and 23% fewer admissions, respectively. Across all jurisdictions, changes in the overall number of admissions reported in 2020/2021 compared with 2017/2018 were in large part driven by changes in the number of admissions for women.

The vast majority (93%) of people admitted into a residential facility for victims of abuse in 2020/2021 were admitted into a short-term housing facility. Declines in the number of admissions since the last cycle of the SRFVA were reported among both short-term (-32%) and long-term facilities (-27%).

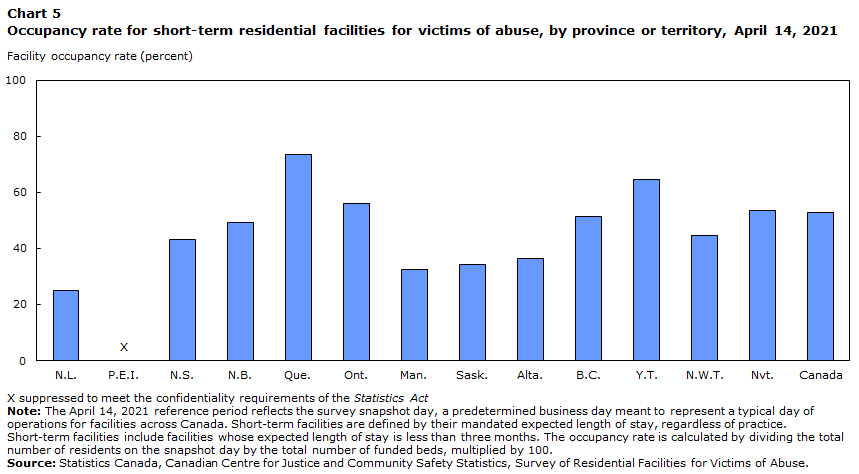

Most short-term facilities operating below capacity on the snapshot day

In total, there were 6,775 funded beds across all short-term facilities in Canada, and 1,273 long-term units (Table 5).Note On the snapshot date, just over half (53%) of the funded beds in short-term residential facilities for victims of abuse were occupied. Additionally, approximately one in seven (15%) short-term facilities across Canada were considered full (Text box 2).

Overall, occupancy on the snapshot day was considerably lower in 2020/2021 than reported in 2017/2018 when short-term facilities had a 78% occupancy rate, and the proportion of facilities that were considered full was double the current proportion (36%; Moreau 2019). These noteworthy differences further shed light on how the COVID-19 pandemic continued to impact shelters. As previously stated, many facilities indicated that their accommodation capacity was impacted by the pandemic. In an effort to combat the COVID-19 pandemic, shelters implemented various measures throughout 2020 and 2021 which reduced the maximum capacity of facilities. For example, physical distancing measures put in place resulted in shelters having to reduce the number of people they could accommodate at a given time—61% of facilities indicated that they reduced their number of beds or units as a measure to curb the spread of the virus in their facility. According to a report from Women’s Shelters Canada (2020), some shelters had to reduce their capacity by up to 50% or more. Therefore, while the occupancy rates may be lower than usual capacity, the maximum occupancy may have differed throughout various points of the pandemic, likely varying by region.

Start of text box 2

Text box 2

Occupancy rate and capacity

An occupancy rate for residential facilities provides an indicator of the total space being used at a given point in time.

- The short-term occupancy rate is calculated by dividing the total number of residents on the snapshot date by the total number of funded beds, multiplied by 100.

- The long-term occupancy rate is calculated by dividing the total number of funded units that were occupied on the snapshot date by the total number of funded units, multiplied by 100.

Typically, in the Survey of Residential Facilities for Victims of Abuse (SRFVA), short-term facilities would be identified as being full if their occupancy rate was 90% or more. An occupancy rate of 90% was selected to account for some misinterpretation of the question regarding number of funded beds, as well as for the fact that some facilities may operate with fewer resources than required to fill every available bed.

Due to measures put in place to combat the COVID-19 pandemic, the maximum occupancy for shelters was reduced, although some shelters still remained at full capacity (Women’s Shelters Canada 2020). To allow for comparisons between the 2020/2021 and 2017/2018 cycles of the SRFVA and because COVID-related measures implemented varied jurisdictionally and likely impacted shelters differently, for the purposes of this article, the 90% or higher occupancy rate was maintained as the standard to be considered full.

Long-term facilities were considered full if their occupancy rate was 100% as a unit is typically an apartment or house.

End of text box 2

More beds occupied in Quebec and Yukon

Occupancy rates for short-term facilities on the snapshot day were highest in Quebec, with 73% of beds occupied, and the Yukon (65%), while Newfoundland and Labrador reported the lowest occupancy rate, with 25% of the beds in the province being occupied that day (Table 6; Chart 5).

Chart 5 start

Data table for Chart 5

| Facility occupancy rate (percent) | |

|---|---|

| N.L. | 25 |

| P.E.I. | X |

| N.S. | 43 |

| N.B. | 49 |

| Que. | 73 |

| Ont. | 56 |

| Man. | 33 |

| Sask. | 34 |

| Alta. | 36 |

| B.C. | 51 |

| Y.T. | 65 |

| N.W.T. | 45 |

| Nvt. | 54 |

| Canada | 53 |

|

X suppressed to meet the confidentiality requirements of the Statistics Act Note: The April 14, 2021 reference period reflects the survey snapshot day, a predetermined business day meant to represent a typical day of operations for facilities across Canada. Short-term facilities are defined by their mandated expected length of stay, regardless of practice. Short-term facilities include facilities whose expected length of stay is less than three months. The occupancy rate is calculated by dividing the total number of residents on the snapshot day by the total number of funded beds, multiplied by 100. Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics, Survey of Residential Facilities for Victims of Abuse. |

|

Chart 5 end

Short-term facilities in urban areas report higher occupancy rates than in rural areas

Overall, one in three (34%) residential facilities for victims of abuse were located in rural areas.Note While the majority of facilities in both rural and urban areas were short-term, long-term facilities accounted for 13% of all facilities in rural areas, compared to 26% of those in urban areas. Long-term facilities in rural areas housed 22% of all long-term admissions in 2020/2021, compared to 30% of short-term admissions.

Similar to results seen in the past, short-term facilities in urban areas had higher occupancy rates than those in rural areas (56% versus 45%), however, overall there were more full short-term facilities in rural areas (19% versus 13% in urban areas, Table 6). Short-term facilities in urban parts of Quebec had the highest occupancy rate (76%) and more than one in five (23%) were full. Among the short-term urban facilities, this was followed by facilities in Ontario (59% occupancy rate), and 16% of the facilities were full.

Among facilities in rural areas of Canada, short-term facilities located in rural areas of Quebec (66%) and New Brunswick (57%) had bed occupancy rates that were much higher than average.

In terms of capacity in long-term facilities, the majority (82%) of units in these facilities were occupied on the snapshot date.Note Note Overall, just under half (45%) of long-term facilities indicated that all of their long-term units were full on the snapshot date.

Similar to short-term facilities, the occupancy rate of long-term facilities was lower in rural areas, with 66% of units being full on the snapshot date compared to 85% of long-term units in urban areas.

More than four in ten residents are children

Although many residential facilities for victims of abuse across Canada have the potential to serve victims of all genders, practically all (99%) of the people who were residing in these shelters on the snapshot date were adult women and their children. More specifically, on the survey snapshot date, there were 5,466 people living in residential facilities for victims of abuse (Table 7). More than half (54% or 2,975) were adult females, and 44% (or 2,423) were children accompanying the adults in the facilities. In total, there were 55 adult men and 13 adults of another gender living in these facilities on that day.

This profile was similar for short- and long-term facilities. Similarly, residents in rural and urban facilities were mostly women and children, though there were slightly more adult residents in rural areas.

Facilities included in the SRFVA were primarily mandated to serve victims of abuse. As such, the vast majority (93%) of people residing in these facilities on the snapshot date were there for reasons of abuse. The remaining 7% of residents were admitted for other reasons, such as homelessness. There is sometimes an overlap between facilities for victims of abuse and homeless shelters. For instance, some violence against women shelters are linked to women’s homeless shelters and services are provided to both groups, recognizing the potential for hidden homelessness among these overlapping populations (Maki 2020).

Notably, however, nearly two-thirds (64%) of adult males residing in facilities for victims of abuse were there for reasons other than abuse (reasons not specified in the survey).Note

Most women in shelters are escaping intimate partner violence

According to the 2018 Survey of Safety in Public and Private Spaces (SSPPS), more than four in ten (44%) women who had ever been in an intimate partner relationship experienced some form of intimate partner violence (physical, sexual, emotional or psychological abuse) during their lifetime (Cotter 2021b). Further, women disproportionally experience the most severe forms of intimate partner violence such as being choked, assaulted or threatened with a weapon, or being sexually assaulted (Breiding et al. 2014; Burczycka 2016).

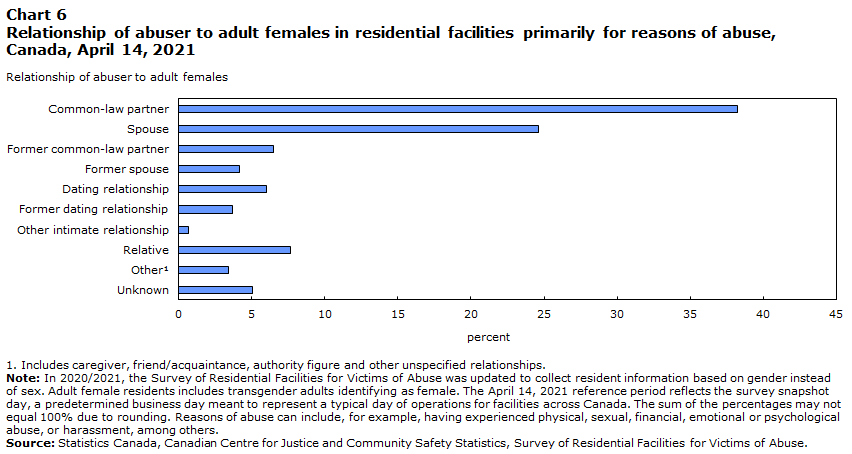

The SRFVA found that the large majority (84%) of women in residential facilities for victims of abuse were there primarily to escape intimate partner violence.Note In fact, almost two-thirds of the women residents were escaping violence involving a current common-law (38%) or spousal (25%) partnerships, and about one in ten were escaping abuse by a former common-law partner (7%) or former spouse (4%, Chart 6). Accordingly, most (70%) women residents in the shelters on the snapshot date were living with their abuser at the time they sought shelter. About one in four (26%) residents were not living with their abuser prior to seeking shelter.Note

Chart 6 start

Data table for Chart 6

| Relationship of abuser to adult females | Percent |

|---|---|

| Common-law partner | 38 |

| Spouse | 25 |

| Former common-law partner | 7 |

| Former spouse | 4 |

| Dating relationship | 6 |

| Former dating relationship | 4 |

| Other intimate relationship | 1 |

| Relative | 8 |

| OtherData table for chart 6 Note 1 | 3 |

| Unknown | 5 |

Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics, Survey of Residential Facilities for Victims of Abuse. |

|

Chart 6 end

Moreover, one in ten (10%) female residents were in facilities for victims of abuse due to violence in a dating context: 6% were escaping violence by a current dating partner and 4% by a former dating partner. Other intimate relationship violence was reported by 1% of female residents. Less than one in ten (8%) residents reported that their abuser was another family member.

According to the SSPPS, sexual minority women are overrepresented as victims of all forms of intimate partner violence (Jaffray 2021).Note Results from the SRFVA indicated that, 2% of adult female residents in shelters were abused by a same-gender intimate partner. Among these residents, similar to different-gender intimate partners, the perpetrator was most commonly (70%) a current common-law partner.

On the snapshot day, one in three (34%) adult female residents in the facilities were self-referred, and this was the most common source of referral for short-term residents. For long-term facilities, fewer residents (27%) were self-referrals. Instead, 40% of adult female residents in long-term facilities were referred by another residential facility for victims of abuse, compared to 7% of residents in short-term facilities. This is unsurprising, as a typical practice, residents often stay in a short-term facility prior to finding longer-term accommodations.

Majority of residents experience emotional, psychological or physical abuse

Psychological abuse, which according to the SSPPS encompasses forms of abuse that targets a person’s emotional, mental or financial well-being, or impedes their personal freedom or sense of safety, is the most common form of intimate partner violence experienced by victims (Cotter 2021b). A similar pattern was found among shelter residents wherein the majority of residents who were in the shelters on the snapshot day had experienced emotional or psychological abuse (89%) or physical abuse (76%, Table 8).Note More than half (54%) of residents had been financially abused.

Among female residents in the shelters, more than one-third (35%) had experienced sexual abuse. Harassment was also experienced by 34% of residents.

Further, while police-reported data show that human trafficking crimes account for a very small proportion of criminal incidents reported in Canada, this serious crime often affects girls and young women (Ibrahim 2021). According to the SRFVA, human trafficking was experienced by 4% of female residents in residential facilities on the snapshot date. In most cases (3%), these residents were victims of human trafficking related to sex work. In total, 15 residents (or less than 1%) had experienced forced labour or another form of human trafficking. These proportions were similar to those reported in 2017/2018.

Most women in shelters have parental responsibilities

Seven in ten (70%) adult females residing in residential facilities for victims of abuse had parental responsibilities.Note Among these residents, 76% were admitted with one or more of their children.

Residential facilities for victims of abuse reported that adult female residents with parental responsibilities were most often protecting their children from emotional or psychological abuse (78%) and exposure to violence (78%).Note Nearly half (48%) of these adult women were protecting their children from physical abuse, and about one in five (22%) from neglect. About one in eight (14%) of these residents were protecting their children from harassment, and nearly one in ten (9%) were protecting them from sexual abuse.

Majority of women in shelters are aged 25 to 44

Some socio-demographic characteristics have been identified as key factors for a higher risk of victimization in general, and for intimate partner violence in particular. For example, in addition to women being more likely to experience violent victimization, age has consistently been identified as one of the main factors in victimization, with rates generally declining with age. Other factors linked with higher victimization rates include having a disability and experiences of homelessness (Cotter 2018; Cotter 2021a). Similarly, in a series of articles on intimate partner violence using data from the SSPPS, intimate partner violence has been found to be more common among certain segments of the population including women (Cotter 2021b), younger women (Savage 2021a) and women with disabilities (Savage 2021b).

Residential facilities for victims of abuse in Canada reported that on the snapshot date, there were 2,749 women who were living in their facilities for reasons of abuse—representing the large majority of the adult residents in the facilities that day. There were an additional 2,281 accompanying children residing in the facilities for reasons of abuse.

Although there were fewer residents living in shelters for victims of abuse compared to the 2018 snapshot date, the age profile of residents remained consistent, and it matched that of victims of violence and intimate partner violence in that they are generally younger (Cotter 2021a; Cotter 2021b). Two-thirds (66%) of women in shelters were between 25 and 44 years old: 19% were aged 25 to 29, 22% were aged 30 to 34, and 26% were aged 35 to 44.Note When the number of women in the Canadian population is taken into account, the rate of women in residential facilities for victims of abuse was highest for women aged 30 to 34, representing 32 women in shelters per 100,000 women in the same age group in the general population.Note This rate was followed by 29 per 100,000 population aged 25 to 29 and 20 per 100,000 women aged 35 to 44.

Similar to 2017/2018 results (Moreau 2019), the large majority (80%) of children accompanying adults in shelters for reasons of abuse were below the age of 12 years: 41% were under the age of 5 and 39% were between 5 and 11 years of age. These proportions were similar for female and male children.Note

Indigenous women and children overrepresented in shelters for victims of abuse

The lived experiences of Indigenous people in Canada are unique because of the historical and ongoing impacts of colonization. Intergenerational trauma, ongoing socioeconomic inequities, systemic barriers and racism are among some of the factors continuing to put Indigenous people at increased risk of victimization. Indigenous women and girls, in particular, are disproportionally more likely to experience violence. Further, trauma is rooted in colonial policies such as the residential school system and Sixties Scoop. These policies have contributed to experiences of child abuse and exposure to violence including intimate partner violence and some of the most severe forms of spousal abuse (Heidinger 2021; The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada 2015; National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls 2019).

Residential facilities for victims of abuse responding to the SRFVA provided the Indigenous identity for the vast majority (91%) of their residents, while for the remaining 9% of residents, their Indigenous identity was not known.Note Note The large majority (71%) of women residing in shelters for reasons of abuse on the snapshot date were not Indigenous. However, relative to their representation in the population (5%), Indigenous women were overrepresented in residential facilities for victims of abuse (Table 9).Note Overall, about one in five (21%) women in facilities were of Indigenous identity. Similarly, while representing 8% of children in the Canadian population, Indigenous children represented 22% of all accompanying children in the facilities.Note These findings were similar to results from the last cycle of the SRFVA.

In 2020/2021, more than one in ten (12%) residential facilities for victims of abuse reported having ties to Indigenous communities or organizations, amounting to a total of 69 facilities. Facilities with ties to Indigenous organizations or communities are those that indicated they were an Indigenous organization; were located in a First Nations, Métis or Inuit community, or on a reserve; or were owned or operated by a First Nations government (band council). More than six in ten (63%) facilities did not have ties, and 24% did not provide a response related to these questions. The vast majority (63 out of 69) of facilities with ties to Indigenous communities were short-term facilities.

While Indigenous and non-Indigenous facilities share many similarities and some differences (Maxwell 2020), the overrepresentation of Indigenous women and children was not limited to Indigenous shelters. Indigenous women made up 16% of women in facilities that did not have ties to Indigenous communities, while Indigenous children accounted for 18% of all children in facilities with no ties to Indigenous communities.

Being able to meet the diverse needs of residents can create a more inclusive environment for survivors of abuse. Overall, nearly two-thirds (64%) of facilities reported having culturally sensitive services for Indigenous peoples (Table 3).Note Having dedicated services for Indigenous people, often means providing safe and equitable services that take into account the historical impacts of colonialism, and the social, cultural and economic factors that influence health outcomes, while empowering cultural identity, knowledge and traditions (Aguiar and Halseth 2015; Bombay et al. 2009; The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada 2015).

Three in ten women and children in shelters belong to a visible minority group

Consistent with self-reported victimization data from the SSPPS, 29% of women and 36% of children in residential facilities for victims of abuse on the snapshot day were identified as belonging to a group designated as visible minority.Note Note The findings were some-what consistent with the representation of visible minority people in the general Canadian population.Note

More than one in ten women (11%) and accompanying children (11%) living in facilities for victims of abuse were non-permanent residents.Note Similar to findings from the last cycle of the SRFVA, these proportions were notably higher than the proportion of non-permanent residents in the general Canadian population (3% and 1%, respectively) (Statistics Canada 2022). Additionally, facilities that reported information regarding the ability of residents to speak an official language indicated that just under one in ten (8%) women living in their facilities did not speak English or French.Note In comparison, according to the 2016 Census, 2% of women and children did not speak at least one official language (Statistics Canada 2016).Note

About half of shelters reported providing services for immigrants or refugees (56%) or in non-official languages (52%). Understanding the cultural contexts and impacts of domestic violence within immigrant and refugee populations is important for enhancing the safety of survivors, and can be a source of strength and support for intervention. Further, immigrants and non-permanent residents may be reluctant to use domestic violence services that inadequately account for, or are dismissive of, their cultural values and their complex and intersecting needs. Therefore, having culturally-informed approaches to providing services to immigrants and refugees, including linguistically-appropriate services, can reduce social isolation and improve social connection (Rossiter et al. 2018).

One in eight women residing in shelters have a disability

As previously noted, women with disabilities are generally overrepresented as victims of violence, including intimate partner violence (Cotter 2018; Savage 2021b). According to the SRFVA, 13% of women and 7% of children residing in shelters on the snapshot date had a disability.Note Note

The large majority (82%) of short-term facilities reported being wheelchair accessible, compared to just under half (48%) of long-term facilities.Note However, less than three in ten facilities reported offering services for persons with hearing disabilities (29%), developmental or intellectual disabilities (26%), visual disabilities (20%) or mobility disabilities (19%). When offered, these services were generally more common in short-term facilities.

Three out of ten women report abuse to the police

According to the General Social Survey on Victimization, in 2019, about one-quarter (24%) of violent incidents were reported to the police, with women and younger victims generally being less likely to report to police (Cotter 2021a). Even fewer incidents are reported to police when they involved a spousal partner, with 19% of spousal violence victims reporting that their spousal violence experience came to the attention of police. Most often, similar to reasons given by women who were victims of crime in general, women who were victims of spousal violence did not report to the police because they considered the incident to be a private or personal matter, that the crime was minor and not worth taking the time to report, or because they felt that no one was harmed (Conroy 2021; Cotter 2021a).

Among women who were in residential facilities for victims of abuse, three in ten (30%) had reported to police the abusive situation that led them to seek shelter (Chart 7). For half (50%) of the residents, the abusive situation did not come to the attention of police, and for the remaining 20% of residents, respondents did not know if the situation was reported to police.

Chart 7 start

Data table for Chart 7

| Region | Percent |

|---|---|

| AtlanticData table for chart 7 Note 1 | 33 |

| Quebec | 34 |

| Ontario | 30 |

| Manitoba | 22 |

| Saskatchewan | 33 |

| Alberta | 23 |

| British Columbia | 33 |

| TerritoriesData table for chart 7 Note 2 | 34 |

| Canada | 30 |

Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics, Survey of Residential Facilities for Victims of Abuse. |

|

Chart 7 end

Additionally, for about one out of seven (15%) women residing in facilities on the snapshot date, charges had been laid against the suspect. An order keeping the abuser away, such as a peace bond or restraining order, had been obtained for 15% of adult women residents.Note The status of whether charges were laid or an order had been obtained was not known for 41% and 36% of adult female residents.

One in five residents stayed at the same facility in the previous year

Nearly all (96%) residential facilities for victims of abuse indicated that they allowed repeat clients.Note Similar to results from the 2017/2018 cycle of the SRFVA, residential facilities which allowed repeat clients indicated that, among adult females residing in their facilities on the snap shot date, about one-third (32%) had previously been served by the same facility. More specifically, about one in five (21%) women residents had received services as residents in the previous year (and potentially through outreach as well). The remaining 11% had not been residents in the previous year, but instead had received services on an outreach basis only.

Of note, for 22% of women residents, it was not known whether or not they had received services in the previous year. It was also not known whether or not residents had received services at other facilities.

Six in ten long-term rural residents are repeat clientele

There were notable difference between residents in rural and urban facilities in terms of repeat clientele. Women residing in long-term rural facilities on the snapshot date were most likely to have received services previously, both as residents (60%) and on an outreach basis only (19%). Women residents of short-term facilities in urban areas were least likely to have been previous residents of the same facilities (15%), compared to women residing in long-term urban facilities (20%) or short-term rural facilities (33%). No notable differences were observed among women residents who received services on an outreach basis.Note

The higher prevalence of repeat clientele in rural areas may be partly attributable to limited availability of facilities in rural areas, where there are fewer options of facilities: 13% of facilities in rural areas are long-term compared with 26% of urban facilities.

Ontario facilities more likely to report longer average length of stay, especially in urban areas

Short-term facilities, by definition, have a general mandate of housing victims of abuse for a short period of time, usually less than three months (see Textbox 1). The average length of time that residents stayed in short-term facilities for victims of abuse remained somewhat the same in 2020/2021 as had had been reported in 2017/2018. Most facilities reported an average length of stay within the mandated three months: 36% reported an average stay of less than one month, and just under half (45%) reported an average of one month to less than three months. However, for nearly one in five (19%) facilities, residents typically stayed longer than the mandated three months.

Across the country, short-term facilities in most provinces and territories reported average lengths of stay that were within three months. However, facilities in Ontario were mostly likely to report an average length of stay that was three months or longer (42%, Chart 8). The lengthier average stay in Ontario shelters may be partly attributable to Ontario’s shortage of affordable housing. With increasing housing and rental prices, affordable housing is an issue faced by many Ontarians (Homeless Hub 2018). Among Canada’s provinces, Ontario has the highest rates of core housing need, second only to the territories (Statistics Canada 2017).Note While the proportion of facilities in British Columbia reporting an average length of stay of three months or more was slightly below the national level (16%), this proportion was the second highest in the country. Similar to Ontario, the rate of core housing need in British Columbia was among the highest in the country.Note

Chart 8 start

Data table for Chart 8

| Region | Less than one month | One to less than three months | Three months or more |

|---|---|---|---|

| percent | |||

| AtlanticData table for chart 8 Note 1 | 32 | 68 | 0 |

| Quebec | 32 | 56 | 11 |

| Ontario | 14 | 44 | 42 |

| Manitoba | 53 | 42 | 5 |

| Saskatchewan | 63 | 38 | 0 |

| Alberta | 75 | 18 | 8 |

| British Columbia | 52 | 32 | 16 |

| TerritoriesData table for chart 8 Note 2 | 31 | 62 | 8 |

| Canada | 36 | 45 | 19 |

Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics, Survey of Residential Facilities for Victims of Abuse. |

|||

Chart 8 end

Overall, facilities in urban areas were more likely to report lengthier average stays. One in five (21%) short-term facilities in urban areas of Canada reported that the average length of stay for residents in their facility in the previous year was three months or more, compared to 14% of rural facilities. Notably, 48% of facilities in urban parts of Ontario reported an average length of three or more months, compared to 29% of rural Ontario facilities.

Most people are turned away because shelter is full

Despite most facilities operating below capacity on the snapshot date, about three in ten (29%) facilities reported turning away people. Between midnight and noon on April 14, 2021, residential facilities across Canada turned away a total of 487 people, 47% fewer people turned away compared to the 2017/2018 snapshot date. The vast majority of the people turned away were women (79%) and children (20%). Most of the people turned away were turned away from short-term facilities (85%).

Reasons for turning people away in 2020/2021 were similar to those provided in 2017/2018. The shelter being full was the most commonly cited reason for turning away people. Specifically, for the 386 women who were turned away that day, 71% were turned away because the shelter was full.Note However, because of capacity restrictions imposed by COVID-19 measures, some shelters were likely considered full for all intents and purposes despite having empty beds or units.

Nearly one in three women leaving a shelter return to the home occupied by the abuser

In addition to people who were turned away from shelters on the snapshot date, 77 women, and 27 accompanying children and men had left the shelters that day. Just over half (52%) of all departures were from urban facilities, and the remaining 48% left rural facilities. All but 4 of the departures were from short-term facilities.

Among the women who left the shelter that day, for whom departure destination information was provided, three in ten (30%) returned to a home where the abuser was living. This was the most commonly cited place where women went after leaving the shelter. Some women returned to a home where the abuser did not reside (12%), and others left to live with friends or relatives (12%). Another 9% of women who left on the snapshot date left for another residential facility for victims of abuse. Few women headed to other destinations such as another type of residential facility, a new accommodation without the abuser or a hospital (combined total of 12%). For 24% of women who left, either the resident or the facility did not know their destination.

Close to four in ten women residents have a history of homelessness

People with a history of homelessness, particularly when recent, are significantly more likely to experience violence (Cotter 2021a). Additionally, intimate partner violence is a leading cause of homelessness among women and a cause of concern for many contemplating leaving an abusive home situation (Meyer 2016; Sullivan et al. 2019; Yakubovich and Maki 2021).

Residential facilities for victims of abuse did not report any women leaving the shelter on the snapshot date that were departing into homelessness. Nevertheless, to further highlight the intersection of homelessness and victimization, close to four in ten (38%) women residing in residential facilities for victims of abuse had a prior history of homelessness—meaning, they had been homeless at some point in their life prior to seeking shelter in the facility.Note A slightly higher proportion (42%) of the residents had never experienced homelessness, and for 20% of the residents for whom any information was reported, their prior history of homelessness was unknown. Additionally, 29% of accompanying children in the facilities had experienced homelessness.

There were no notable differences between women residing in rural and urban facilities who had a history of homelessness (39% versus 38%).

Lack of affordable and permanent housing most common issue faced by facilities and their residents

When asked about the top three issues or challenges facing residents of shelters for victims of abuse, the vast majority (81%) of facilities who provided a response on behalf of their residents indicated that a lack of affordable long-term housing upon departure was among the top (Table 10). Many facilities also indicated that underemployment and low incomes (45%), mental health issues (36%) and substance use issues (30%) were some of the main challenges faced by residents.

Further, a lack of permanent housing was the most commonly reported issue faced by the facilities themselves. About two in five (41%) facilities reported this as one of the top three issues that they were currently facing (Table 11). Other commonly reported issues named as the top three faced by facilities included: staff turnover (31%), meeting the diverse needs of clients (28%), low employee compensation (27%) and lack of funding (26%).

There were regional differences in the types of issues faced by facilities. For example, a lack of permanent housing was of particular concern for facilities in Ontario (51%) and British Columbia (55%). In Quebec, nearly seven in ten (69%) facilities reported staff turnover as one of the main issues they were facing, while more than four in ten (44%) facilities in Alberta indicated that meeting the diverse needs of clients was a key issue for them.

Overall, the main issues and challenges reported by facilities and their residents in 2020/2021 were similar to those reported in 2017/2018.

Revenues and expenditures

In general, funding for shelters across the country are provided through numerous sources, including government sources at all levels, private donations, as well as fundraising activities. Monitoring shelters’ revenues and mapping them against their expenditures is important in order to determine their funding needs and identify gaps in the ability of facilities to support clients.

Majority of funding for residential facilities for victims of abuse are from provincial and territorial governments

In 2020/2021, residential facilities for victims of abuse received more than $578.3 million in funding, with 90% going to short-term facilities. The majority (81%) of the funding came from government sources—particularly, from provincial and territorial governments. Provincial and territorial governments provided the large majority of the funding for short-term facilities (70%) and about half (48%) of the funding for long-term facilities. Federal government funding accounted for 10% and 7% of the revenues reported by short- and long-term facilities, respectively. For long-term facilities, more funding was provided by regional or municipal governments (12%). Additionally, in long-term facilities, 11% of their revenues were from charging fees for services and 10% were from foundations. Fundraising and donations provided 10% of the revenues for both short-term and long-term facilities.

There were some notable differences between the sources of funding for shelters with ties to Indigenous communities and those without such ties. For example, provincial or territorial government funding accounted for the largest share of the funding for both types of facilities, with much lower for Indigenous shelters (52% versus 71% for non-Indigenous shelters). Fundraising or donations also accounted for a notably lower proportion of the revenues for Indigenous shelters compared with non-Indigenous (3% versus 13%). However, nearly one-third (31%) of the revenues received by Indigenous facilities were from Federal government sources compared with 6% of the funding received by shelters with no ties to Indigenous communities. This difference may be partly reflective of the Federal government’s commitments, through its Violence Prevention Strategy, to providing funding support for gender-based violence shelters for Indigenous peoples (Government of Canada 2020).

Shelters spent over $509 million for their operations in 2020/2021. The large majority (89%) of these expenses were reported by short-term facilities, which accounted for 78% of all shelters (Table 12). In both short- and long-term facilities, salary costs represented the largest share of expenses, accounting for 73% of expenses in short-term facilities and 56% in long-term facilities. In long-term facilities, however, more money was spent on rent, mortgage and property taxes (14% versus 2% in short-term facilities), and other housing costs (11% versus 5%).

More than four in ten facilities make major physical repairs or improvements to the facility

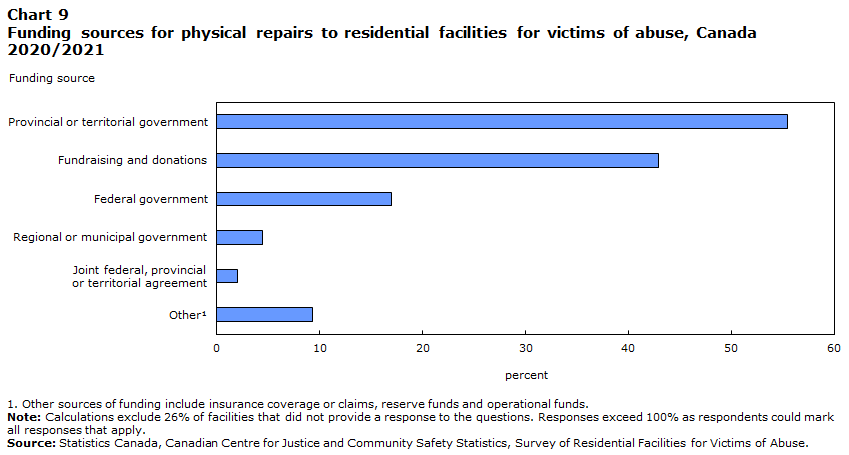

Previous research has found that most violence against women shelters across Canada are considered aging, having an average age of 45 years. It was found that most shelters needed some form of repairs and renovations, with a majority needing major repairs or renovations. However, funding for such repairs was an issued identified by many facilities (Maki 2019).

According to the SRFVA, about six in ten (61%) facilities indicated that they had made some type of physical repairs or improvements in 2020/2021. Just over three-quarters (77%) of these facilities reported minor repairs or improvements such as repairs to missing or loose floor tiles, or steps, railing or siding. More than four out of ten (43%) facilities reported making major physical repairs or improvements where there was a legal requirement to make repairs for safety reasons or for meeting building codes.

Provincial and territorial governments were the most common sources for funding for making physical repairs or improvements, reported by more than half (55%) of facilities that indicated making such repairs in the previous year (Chart 9). More than four in ten (43%) facilities reported that their repairs or improvements were funded through fundraising or donations. About one in six (17%) facilities reported that federal government funding was a source of funds for the repairs.

Chart 9 start

Data table for Chart 9

| Funding source | Percent |

|---|---|

| Provincial or territorial government |

55 |

| Fundraising and donations | 43 |

| Federal government | 17 |

| Regional or municipal government | 4 |

| Joint federal, provincial or territorial agreement | 2 |

| OtherData table for chart 9 Note 1 | 9 |

Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics, Survey of Residential Facilities for Victims of Abuse. |

|

Chart 9 end

Summary

The COVID-19 pandemic has had unprecedented impacts on how people live their lives, with measures such as lockdown restrictions and school closures. People being confined to their homes coupled with economic stressors has created situations that could lead to increases in intimate partner violence. People and organizations providing supports and services to victims of intimate partner violence have also been affected by the measures that were put in place to prevent further spread of the virus.

Residential facilities for victims of abuse across Canada implemented many measures in an effort to mitigate the impact of COVID-19, including enhancing health protection or cleaning practices, using new communication technologies, expanding their services and programs to support victims outside of their facilities, and designating isolation units or areas. About six in ten (61%) facilities reduced the number of beds or units in their facilities in an effort to minimize the spread of the virus. In 2020/2021, residential facilities for victims of abuse admitted more than 46, 800 people, approximately 31% fewer compared to the 2017/2018 cycle of the Survey of Residential Facilities for Victims of Abuse (SRFVA). Further, the occupancy rate for short-term facilities was considerably lower than in 2017/2018, with 53% of short-term beds being occupied on the snapshot date of April 14, 2021—a date representing a typical day of operations for shelters. About one in seven (15%) short-term facilities were considered full on the snapshot day. Nevertheless, 487 people were turned away from these facilities. Many facilities cited the shelter being at capacity as the main reason for turning people away.

The characteristics of shelters, and the profiles of their residents and the types of abuse they experienced, remained similar to the previous cycle of the survey. However, the pandemic appeared to have an impact on the number of admissions.

According to the SRFVA, the majority of shelters were impacted to a moderate or great extent by the pandemic restrictions. The initial lockdown measures enacted at the beginning of the pandemic presented the most challenging time for shelters, with 50% indicating that they were impacted to a great extent, and 30% to a moderate extent. Many facilities reported an increase in crisis calls and saw an uptake in support services required outside the shelters on an outreach basis. Some facilities also identified staffing-related challenges during the pandemic, including challenges related to hiring or training new staff, and volunteer work.

More than a year after the onset of the pandemic, 23% of facilities reported still being impacted to a great extent, while 38% indicated that the impact was moderate. Facilities reporting minor to no impact at all doubled, from 19% at the period of initial lockdowns to 38% in the spring and summer of 2021. Similar to the last SRFVA cycle, lack of affordable and permanent housing continued to be a common issue faced by facilities and their residents in 2020/2021.

The next cycle of the SRFVA is planned for 2022/2023. Results from the next cycle, to be published in 2024, will provide further insight into residential facilities and their clients, demands for services, and how facilities may be continuing to cope with the COVID-19 pandemic or its aftermath.

Detailed data tables

Table 7 Residents in facilities for victims of abuse, by province or territory, April 14, 2021

Survey description

Survey of Residential Facilities for Victims of Abuse

The Survey of Residential Facilities for Victims of Abuse (SRFVA) is a census of Canadian residential facilities primarily mandated to provide residential services to victims of abuse (defined as ongoing victimization). The SRFVA was conducted for the second time in 2020/2021, following a major redesign of its predecessor: the Transition Home Survey. The first cycle of the SRFVA was conducted in 2017/2018.

The objective of the SRFVA is to produce aggregate statistics on the services offered by these facilities during the previous 12-month reference period, as well as to provide a one-day snapshot of the clientele being served on a specific date (mid-April of the survey year). The intent of the survey is to provide information that is useful for various levels of government, sheltering and other non-profit organizations, service providers and researchers to assist in developing research, policy and programs, as well as identifying funding needs for residential facilities for victims of abuse.

Data collection

Active data collection for the SRFVA took place between April and August of 2021. Data collection was conducted through a self-administered electronic questionnaire. Follow-ups by Statistics Canada interviewers for non-respondents and cases of incomplete questionnaires were facilitated through the use of computer-assisted telephone interviews.

With the exception of analysis related to the impact of the pandemic on facilities which refers to pre- and post-pandemic periods, the information presented in this article refers to two distinct time periods: first, data pertaining to the number of annual admissions, average length of stay and financial information are based on a 12-month reference period (2020/2021) that preceded the SRFVA. Respondents were asked to select a 12-month reference period that most closely resembled the period their facility refers to in its annual reports. Categories included a standard fiscal year (April 1, 2020 to March 31, 2021), a calendar year (January 1, 2020 to December 31, 2020) or a 12-month period of their choosing. In 2020/2021, 92% of facilities responding to the survey reported their annual information based on the standard fiscal year. Second, the characteristics of facilities and the types of services offered, as well as the profile of those using residential facilities are based on the snapshot date of April 14, 2021. The snapshot date is a predetermined business day meant to represent a typical day of operations for facilities across Canada. The April 14, 2021 date was selected based on consultations with service providers. It reflected a period of relative stability in terms of admissions and respondents could maximize the resources available to respond to the survey. The snapshot day does not reflect seasonal differences in facility use nor long-term trends throughout the year.

Target population and response rates

Facilities surveyed were identified by Statistics Canada through its consultations with provincial and territorial governments, transition home associations, other associations and a review of entities on the Statistics Canada Business Register. Facilities potentially in-scope were then contacted prior to the collection of the survey to determine their primary mandate. These may include short-term, long-term and mixed-use facilities; transition homes; second stage housing; safe home networks; satellites; women's emergency centres; emergency shelters; Interim Housing (Manitoba only); Rural Family Violence Prevention Centres (Alberta only); family resource centres and; any other residential facilities offering services to victims of abuse with or without children.

Of the 557 residential facilities who identified their primary mandate as providing services to victims of abuse in 2020/2021, 437 returned their questionnaire for a response rate of 78%. For those respondents who did not provide their information through the questionnaire, and for those respondents who did not answer some key questions in their questionnaires, imputation was used to complete the missing data for key questions. Imputation methods included the use of trend-adjusted historical data when available and donor imputation, where values are taken from a similar record in terms of facility location, type and size. The key questions for which imputation was carried out are: number of beds, number of units, number of residents for reasons of abuse, whether or not facility serves repeat clients, relationship to primary abuser, number of people turned away from facility, number of departures from facility, average length of stay, number of admissions, revenues and expenses.

For more information and copies of the questionnaire, refer to the Statistics Canada survey information page: Survey of Residential Facilities for Victims of Abuse.

References

Aguiar, W. and R. Halseth. 2015. “Aboriginal Peoples and Historic Trauma: The Processes of Intergenerational Transmission.” National Collaborating Centre for Aboriginal Health.

Bombay, A., Matheson, K. and H. Anisman. 2009. “Intergenerational trauma: convergence of multiple processes among First Nations peoples in Canada.” Journal of Aboriginal Health. Vol. 5, no. 3.

Breiding, M.J., Chen J., and M.C. Black. 2014. “Intimate Partner Violence in the United States — 2010.” National Center for Injury Prevention and Control.

Brooks, S.K., Webster, R.K., Smith, L.E., Woodland, L., Wessely, S., Greenberg, N. and G.J. Rubin. 2020. “The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence.” The lancet. Vol. 395, no. 10227.

Burczycka, M. 2016. “Trends in self-reported spousal violence in Canada, 2014.” In Family Violence in Canada: A statistical profile, 2014. Juristat. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 85-002-X.

Centre for Research and Education on Violence Against Women and Children. 2021. “COVID-19 & Gender-Based Violence in Canada: Key Issues and Recommendations.” Learning Network.

Conroy, S. 2021. “Family violence in Canada: A statistical profile, 2019.” Juristat. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 85-002-X.