Police-reported crime statistics in Canada, 2020

by Greg Moreau, Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics

Highlights

- The COVID-19 pandemic has had profound impacts on Canada’s economy, health care system and society in general. Policies enacted to contain the spread of the virus have resulted in unprecedented disruptions in the social and economic lives of Canadians, changing how we interact, socialize, learn, work and consume.

- The volume of police-reported crime in the early months of the pandemic was far lower compared to the previous year. In the first three months of 2020, the number of police-reported criminal incidents was 4% higher than the same three-month period in 2019. In April 2020, the first full month of the pandemic and generally the month with the most country-wide restrictions in place, there were 18% fewer criminal incidents compared to April 2019. Overall, crime levels were lower than the previous year throughout the pandemic period from March to December.

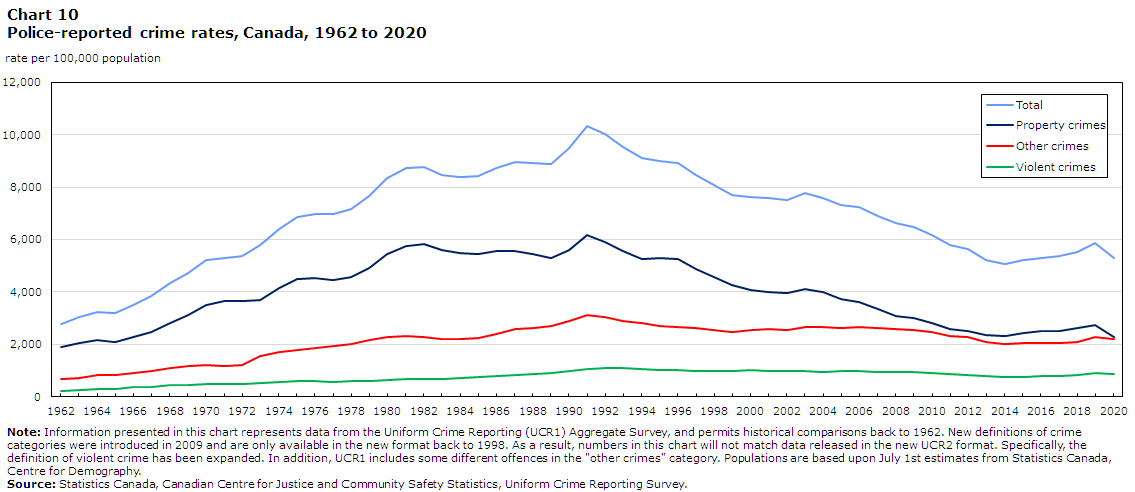

- There were over 2 million police-reported Criminal Code incidents (excluding traffic) in 2020, about 195,000 fewer incidents than in 2019. At 5,301 incidents per 100,000 population, the police-reported crime rate—which measures the volume of crime—decreased 10% in 2020. The police-reported property crime rate decreased 13%, the largest percentage change, up or down, dating back to 1998.

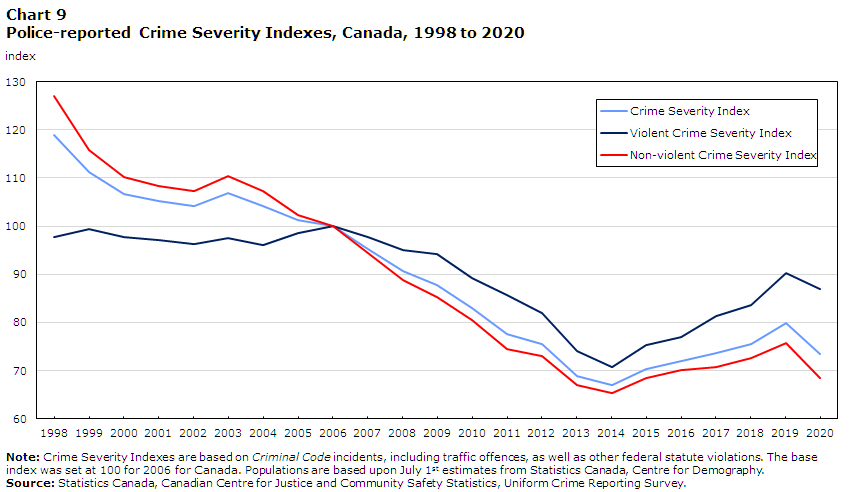

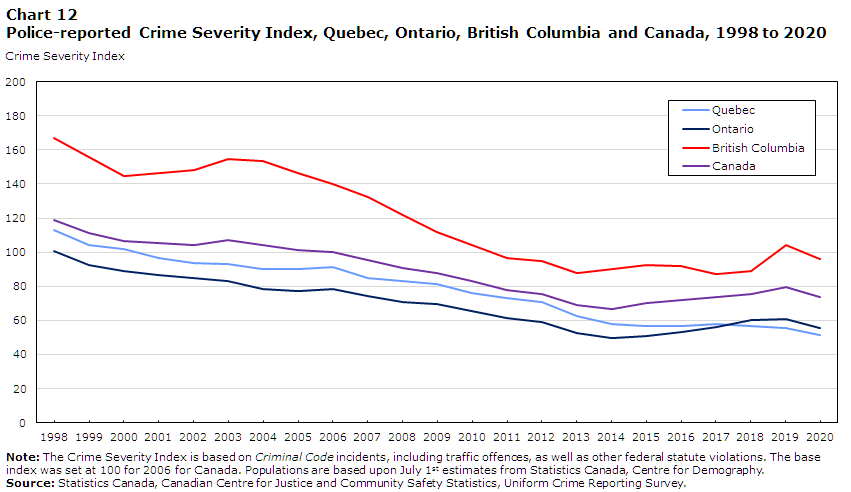

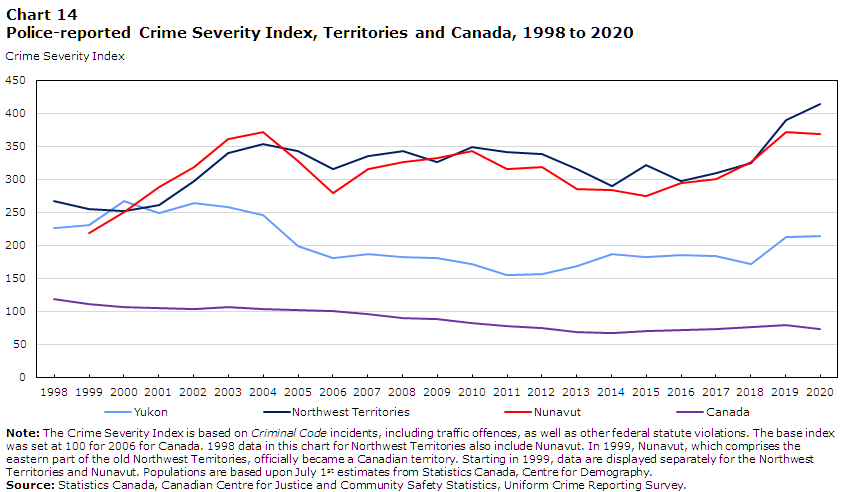

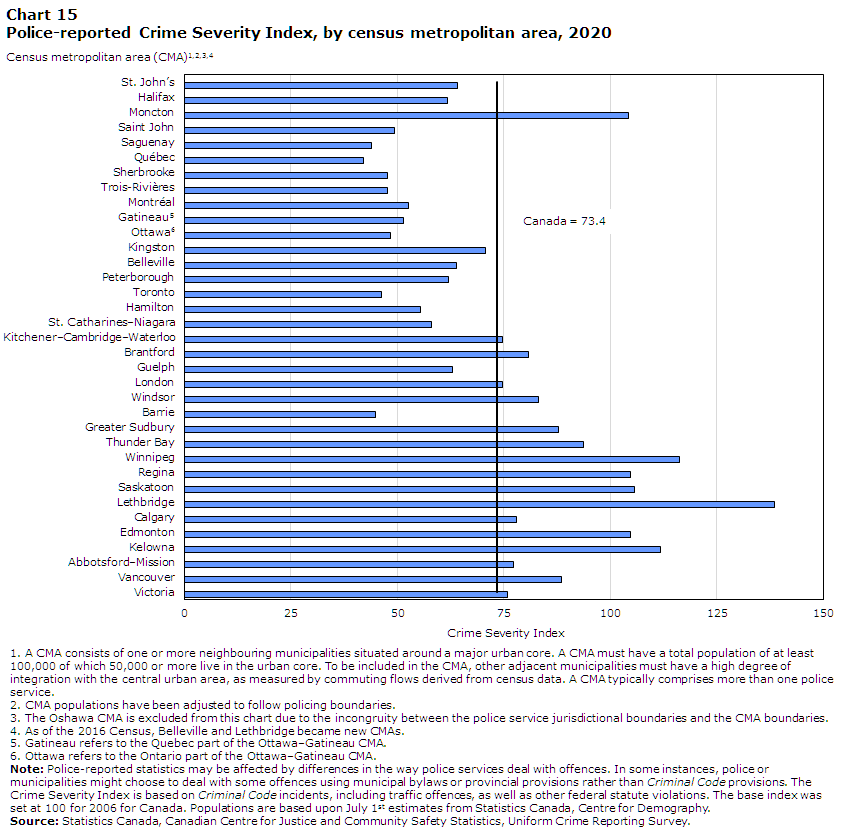

- Police-reported crime in Canada, as measured by the Crime Severity Index (CSI), decreased 8% from 79.8 in 2019 to 73.4 in 2020, and was -11% lower than a decade earlier in 2010. The CSI measures the volume and severity of police-reported crime in Canada, and it has a base index value of 100 for 2006.

- The decline in the overall CSI in the first year of the pandemic was the result of decreases in police-reported rates of numerous offences. Most notably, there were decreases in the rates of police-reported breaking and entering (-16%), theft of $5,000 or under (-20%), robbery (-18%), shoplifting of $5,000 or under (-36%), administration of justice violations (-17%) and sexual assault (level 1) (-9%).

- In 2020, all measures of the CSI—the overall CSI, the Violent CSI and the Non-violent CSI—decreased for the first time after five years of increases. The combined volume and severity of violent crimes, as measured by the Violent CSI, was 87.0, a 4% decrease from 2019. The combined volume and severity of non-violent crime, as measured by the Non-violent CSI, decreased 10% in 2020. This was the largest year-over-year change in the Non-violent CSI dating back to 1998, the first year for which CSI data are available.

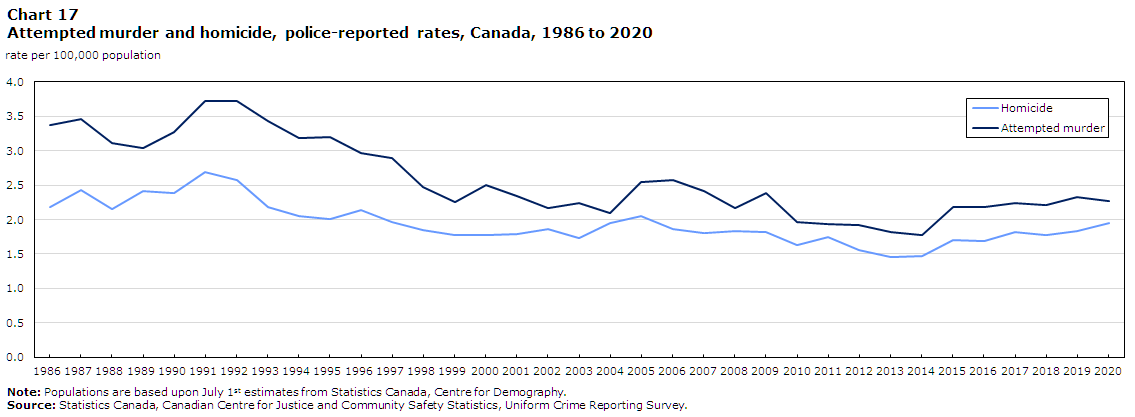

- In April 2020, 22 people were killed and 3 others were injured in a mass shooting in Nova Scotia, marking the deadliest mass shooting in Canadian history. Nationally, there were 743 homicides, 56 more than the previous year. The national homicide rate increased 7% from 1.83 homicides per 100,000 population in 2019, to 1.95 homicides per 100,000 population in 2020.

- In 2020, police reported 201 Indigenous victims of homicide, 22 more than in 2019. Of these victims, 62% were identified by police as First Nations peoples, 4% as Métis and 9% as Inuk (Inuit). For an additional 24% of Indigenous victims of homicide, the Indigenous group to which they belonged was not identified. The rate of homicide for Indigenous peoples was approximately 7 times higher than the rate for non-Indigenous people (10.05 homicides per 100,000 compared to 1.42 per 100,000).

- The first year of the pandemic saw 718 more police-reported hate crimes compared with 2019, a 37% increase. The 2,669 police-reported hate crimes in 2020 were the largest number recorded since comparable data became available in 2009. This increase was largely the result of more police-reported hate crimes targeting the Black population (+318 incidents or +92%), the East or Southeast Asian population (+202 incidents or +301%), the Indigenous population (+44 incidents or +152%), and the South Asian population (+38 incidents or +47%).

- In 2020, there were 5,142 opioid-related offences in Canada, representing a rate of 14 per 100,000 population, a 34% increase compared to 2019. Opioid-related offences were the only specific drug type to increase in 2020 compared to 2019; police-reported rates of cannabis (-25%), heroin (-15%), ecstasy (-7%), methamphetamine (-5%) and cocaine-related drug offences (-2%) all decreased.

Since 1962, Statistics Canada has collected information on all criminal incidents reported by Canadian police services through its annual Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR) Survey.Note In addition to the UCR, Statistics Canada also collects information on self-reported criminal victimization through the General Social Survey (GSS) on Canadians’ Safety (Victimization), which is conducted every five years. Unlike the UCR, the GSS on Victimization collects self-reported data which includes incidents that may not have been brought to the attention of the police. These complementary surveys provide a more complete picture of crime and victimization in Canada.

This Juristat article presents findings from the 2020 UCR Survey to provide information on police-reported crime across Canada and over time. To publish police-reported crime statistics in a timely manner, this article relies mostly on aggregate data (totals), which are the first crime data available each calendar year. To inform some safety issues which are particularly relevant to the pandemic, such as family violence and hate crime, this article also draws on detailed disaggregated data on the characteristics of incidents, victims and accused persons. These disaggregated data will also be available for custom requests and will be included in future analytical products.Note Crime counts presented in the article are based on the most serious violation in a criminal incident (see “Key terminology and definitions”).

This article first provides an overview of important context surrounding Canadian crime in 2020 given the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. This is followed by an analysis of the key statistical trends reported by police in 2020, and the offences driving these trends in crime. The article also explores more general trends in the volume and severity of police-reported crime at the national, provincial/territorial and census metropolitan area (CMA) levels, as well as more detailed information on changes in violent and non-violent criminal offences. Finally, the article looks at trends for youth accused of crime.Note

COVID-19 context for police-reported crime statistics in 2020

Police-reported crime statistics reflect only those incidents that are reported to the police, which can be affected by large-scale criminal events, social movements and changes in legislation, policies and procedures (see Text box 1).

The COVID-19 pandemic has had profound impacts on Canada’s economy, health care system and society in general. Policies enacted to contain the spread of the virus have resulted in unprecedented disruptions in the social and economic lives of Canadians, changing how we interact, socialize, learn, work and consume. Since March 2020, the vast majority of Canada’s population were typically spending more time at home and many businesses closed or turned to new methods of operation, often online. These changes have, at least partially, affected crime patterns across the country.

Stay-at-home orders meant more people were home for longer periods of time, increasing guardianship, while fewer people were outside with the opportunity to commit crimes. For some people, however, confinement at home posed a risk where family violence was a factor. For crimes that can be difficult to report due to the nature of the offence—for example crimes committed by family members—confinement and reduction or changes in services for victims could have also impacted reporting to police.

During the pandemic, Canadians turned to the Internet to facilitate work, school, shopping, health care and social interaction (Bilodeau et al. 2021; Statistics Canada 2020a). A greater online presence could increase the risk for different types of criminal offences facilitated by the Internet.

Finally, the pandemic could have also impacted offences against the administration of justice, such as breach of probation and failure to appear in court or at mandatory meetings with probation or parole officers. Lockdown conditions meant fewer opportunities to breach conditions and the reduction of court processes and in-person hearings would impact the possibility to fail to appear. Information on the broader social and economic impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic can be found on “Statistics Canada’s COVID-19 hub.”

Start of text box 1

Text box 1

Factors influencing police-reported crime

There are many factors that influence police-reported crime statistics. First, an incident must come to the attention of police. The decision by an individual to report a criminal incident to police has a considerable impact on the number of crimes ultimately recorded by police. The 2019 General Social Survey on Canadians’ Safety (Victimization), which provides information on the crime reporting behaviour of Canadians aged 15 and older for selected offences, indicated that about one-third (29%) of crimes are reported to police (see Text box 9 for more information on self-reported and police-reported data).

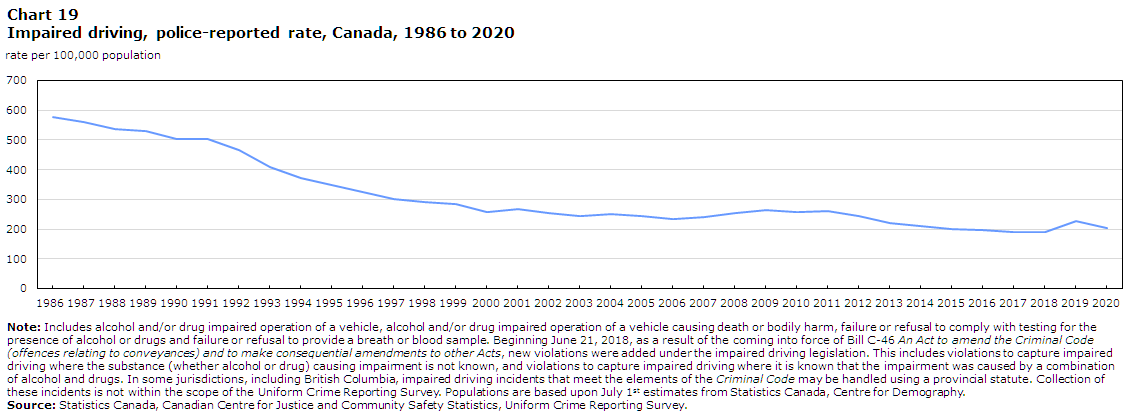

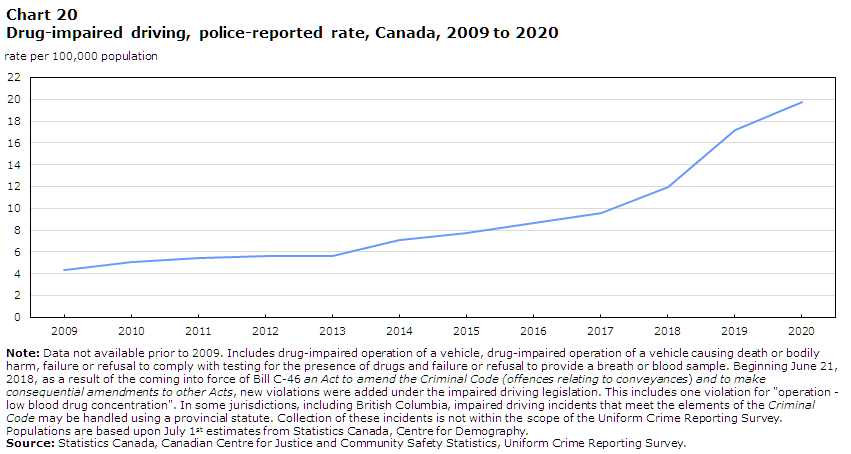

Second, differences between individual police services—such as available resources or departmental priorities, policies and procedures—can also have an effect on police-reported crime. For instance, as a crime prevention measure, some police services have implemented initiatives to focus attention on prolific or repeat offenders within the community. Moreover, certain crimes such as impaired driving and drug offences can be significantly affected by enforcement practices, with some police services devoting more resources to these specific types of crime. Some police services may also rely on municipal bylaws or provincial statutes to respond to minor offences such as mischief and disturbing the peace.

Third, and more broadly, social and economic factors can influence the volume of police-reported crime at a national, regional, municipal or neighbourhood level. In particular, crime rates can be affected by changes in age demographics (Britt 2019; Loeber et al. 2015), economic conditions (Wilson 2018; Janko and Popli 2015), neighbourhood characteristics (Ha and Andresen 2017), the emergence of new technologies (Milivelojevic and Radulski 2020; Brewer et al. 2018; McGovern 2015) and Canadians’ attitudes toward crime and risky behaviour (Ouimet 2004).

End of text box 1

Police-reported monthly crime far lower throughout the pandemic compared to the previous year

Overall, the police-reported crime rate (excluding traffic offences) in Canada decreased 10% from 2019 to 2020. The annual rates of violent crime (-2%), property crime (-13%), and other Criminal Code offences (-10%) all decreased for the first time after five years of increases. Additionally, the rates of police-reported drug offences under the CDSA and the Cannabis Act (-5%) and other federal statute violations (-22%) saw large declines in 2020 (Table 1).

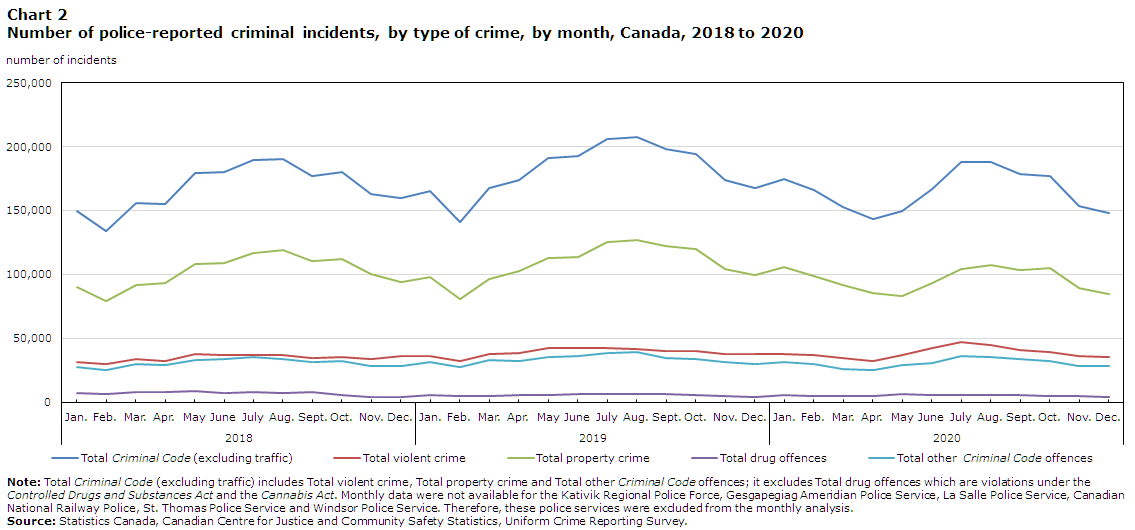

In the first three months of 2020, the number of police-reported criminal incidents increased 4% compared to the same three-month period in 2019 (Chart 1).Note Both violent crime and property crime were up during this time. From March to April 2020, the first full month of the pandemic and generally the month with the most country-wide restrictions in place, the number of police-reported crimes decreased 6%. The volume of crime reported during the month of April 2020 was 18% lower compared to April 2019.

Chart 1 start

Data table for Chart 1

| Month | Total Criminal Code (excluding traffic) - 2019 | Total Criminal Code (excluding traffic) - 2020 | Total violent crime - 2019 | Total violent crime - 2020 | Total property crime - 2019 | Total property crime - 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| number of incidents | ||||||

| January | 165,389 | 174,417 | 36,197 | 37,712 | 97,721 | 105,472 |

| February | 140,960 | 165,690 | 32,592 | 36,837 | 80,981 | 98,602 |

| March | 167,357 | 152,381 | 37,865 | 35,002 | 96,640 | 91,655 |

| April | 174,052 | 143,128 | 38,859 | 32,373 | 103,067 | 85,509 |

| May | 190,862 | 149,505 | 42,235 | 37,362 | 112,935 | 82,886 |

| June | 192,594 | 167,033 | 42,424 | 42,352 | 113,729 | 93,710 |

| July | 206,127 | 187,872 | 42,693 | 47,480 | 125,203 | 104,125 |

| August | 207,788 | 187,636 | 41,540 | 44,934 | 127,225 | 107,262 |

| September | 198,019 | 178,663 | 40,448 | 41,275 | 122,519 | 103,329 |

| October | 194,035 | 176,949 | 40,562 | 39,772 | 119,889 | 104,971 |

| November | 173,705 | 153,806 | 37,976 | 36,214 | 104,517 | 89,206 |

| December | 167,812 | 147,899 | 37,663 | 35,226 | 99,818 | 84,519 |

|

Note: Total Criminal Code (excluding traffic) includes "other Criminal Code" offences not included in Total violent crime or Total property crime. Monthly data were not available for the Kativik Regional Police Force, Gesgapegiag Ameridian Police Service, La Salle Police Service, Canadian National Railway Police, St. Thomas Police Service and Windsor Police Service. Therefore, these police services were excluded from the monthly analysis. Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics, Uniform Crime Reporting Survey. |

||||||

Chart 1 end

In recent years, crime was typically at its lowest in the first quarter of the year, specifically in January and February. Crime would then begin to increase to a peak in July and August, before dropping again in the fall and winter months (Chart 2). This pattern remained fairly similar in 2020, although overall crime levels were typically lower than the two previous years throughout the pandemic period from March to December. Comparing monthly data for 2020 with 2019, violent and non-violent crime showed relatively large decreases in March, April and May, while for the months of July (+11%), August (+8%) and September (+2%), violent crime increased above the pre-pandemic 2019 levels. This was largely the result of more incidents of assault (level 1 and 2), uttering threats and sexual assault (level 1) during the summer months.

Chart 2 start

Data table for Chart 2

| Year and month | Total Criminal Code (excluding traffic) | Total violent crime | Total property crime | Total drug offences | Total other Criminal Code offences | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| number of incidents | ||||||

| 2018 | Jan. | 149,379 | 31,380 | 89,958 | 7,373 | 28,041 |

| Feb. | 134,322 | 29,746 | 79,353 | 6,189 | 25,223 | |

| Mar. | 155,848 | 33,928 | 91,975 | 8,153 | 29,945 | |

| Apr. | 155,291 | 32,698 | 93,411 | 8,018 | 29,182 | |

| May | 179,198 | 37,658 | 108,295 | 8,518 | 33,245 | |

| June | 179,804 | 37,137 | 109,133 | 7,506 | 33,534 | |

| July | 189,116 | 37,065 | 116,923 | 8,334 | 35,128 | |

| Aug. | 190,214 | 37,013 | 118,979 | 7,611 | 34,222 | |

| Sept. | 177,083 | 35,004 | 110,153 | 7,971 | 31,926 | |

| Oct. | 180,449 | 35,640 | 112,270 | 5,744 | 32,539 | |

| Nov. | 162,978 | 33,959 | 100,371 | 4,208 | 28,648 | |

| Dec. | 159,502 | 36,235 | 94,447 | 4,090 | 28,820 | |

| 2019 | Jan. | 165,389 | 36,197 | 97,721 | 5,579 | 31,471 |

| Feb. | 140,960 | 32,592 | 80,981 | 5,254 | 27,387 | |

| Mar. | 167,357 | 37,865 | 96,640 | 5,285 | 32,852 | |

| Apr. | 174,052 | 38,859 | 103,067 | 5,821 | 32,126 | |

| May | 190,862 | 42,235 | 112,935 | 6,046 | 35,692 | |

| June | 192,594 | 42,424 | 113,729 | 6,290 | 36,441 | |

| July | 206,127 | 42,693 | 125,203 | 6,287 | 38,231 | |

| Aug. | 207,788 | 41,540 | 127,225 | 6,349 | 39,023 | |

| Sept. | 198,019 | 40,448 | 122,519 | 6,496 | 35,052 | |

| Oct. | 194,035 | 40,562 | 119,889 | 6,061 | 33,584 | |

| Nov. | 173,705 | 37,976 | 104,517 | 5,162 | 31,212 | |

| Dec. | 167,812 | 37,663 | 99,818 | 4,182 | 30,331 | |

| 2020 | Jan. | 174,417 | 37,712 | 105,472 | 5,853 | 31,233 |

| Feb. | 165,690 | 36,837 | 98,602 | 5,383 | 30,251 | |

| Mar. | 152,381 | 35,002 | 91,655 | 4,622 | 25,724 | |

| Apr. | 143,128 | 32,373 | 85,509 | 5,323 | 25,246 | |

| May | 149,505 | 37,362 | 82,886 | 6,582 | 29,257 | |

| June | 167,033 | 42,352 | 93,710 | 5,699 | 30,971 | |

| July | 187,872 | 47,480 | 104,125 | 5,582 | 36,267 | |

| Aug. | 187,636 | 44,934 | 107,262 | 5,671 | 35,440 | |

| Sept. | 178,663 | 41,275 | 103,329 | 6,030 | 34,059 | |

| Oct. | 176,949 | 39,772 | 104,971 | 5,301 | 32,206 | |

| Nov. | 153,806 | 36,214 | 89,206 | 5,337 | 28,386 | |

| Dec. | 147,899 | 35,226 | 84,519 | 4,450 | 28,154 | |

|

Note: Total Criminal Code (excluding traffic) includes Total violent crime, Total property crime and Total other Criminal Code offences; it excludes Total drug offences which are violations under the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act and the Cannabis Act. Monthly data were not available for the Kativik Regional Police Force, Gesgapegiag Ameridian Police Service, La Salle Police Service, Canadian National Railway Police, St. Thomas Police Service and Windsor Police Service. Therefore, these police services were excluded from the monthly analysis. Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics, Uniform Crime Reporting Survey. |

||||||

Chart 2 end

Start of text box 2

Text box 2

Special monthly data collection: Police-reported crime and calls for service

during the COVID-19 pandemic

To track information on selected types of Criminal Code violationsNote during the COVID-19 pandemic, Statistics Canada began collecting preliminary monthly crime data in the early months of the pandemic from a subset of police services representing 71% of the Canadian population. At the same time, preliminary information was collected on selected calls for police service—that is, calls for help which may not be related to crime.Note

Police-reported calls for service during the COVID-19 pandemic

Alongside responding to criminal events, police perform many duties including responding to events that are directly related to public safety and well-being, otherwise referred to as “calls for service.”

Police services in this special study responded to 9% more selected calls for service during the pandemic months in 2020 (i.e., March to December 2020) than they did over the same period in 2019. In particular, the police services that were able to report data on these calls for service responded to more calls related to general well-being checks (+16%), mental health-related calls such as responses to a person in emotional crisis or apprehensions under the Mental Health Act (+13%), and domestic disturbances (+7%).

See Text box 3 for more detailed information on family violence during the pandemic.

Early crime trend in 2021

Early data collected for 2021 from the same subset of police services indicate that crime was down 20% in the first quarter of 2021 compared to the first quarter of 2020.Note The month of April 2021, however, was 9% higher than April 2020, the first full month of the pandemic. Data for this project will continue to be collected on a monthly basis and released regularly.

See data table 35-10-0169-01 for more information.Note

End of text box 2

Key findings for police-reported crime in Canada in 2020

Significant decrease in rates of violations related to theft, including breaking and entering, robbery and shoplifting

Decreases in property crime were the main contributors to the overall decline in crime in 2020. With stay-at-home orders and many individuals working remotely, most Canadians were not leaving their homes as often, increasing guardianship and reducing opportunities for some property crimes. Violations such as breaking and entering, shoplifting of $5,000 or under and theft of $5,000 or under experienced large decreases from 2019 to 2020 (Chart 3). Robbery, which is considered a violent offence because it involves the use or threat of violence during the commission of a theft, similarly experienced a large annual decrease (see Key terminology and definitions).

Chart 3 start

Data table for Chart 3

| Year | Breaking and entering | Robbery | Shoplifting of $5,000 or under | Theft of $5,000 or under |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| rate per 100,000 population | ||||

| 1998 | 1,163 | 109 | 303 | 2,063 |

| 1999 | 1,046 | 107 | 276 | 1,955 |

| 2000 | 956 | 100 | 262 | 1,899 |

| 2001 | 901 | 99 | 258 | 1,869 |

| 2002 | 879 | 96 | 257 | 1,871 |

| 2003 | 901 | 101 | 271 | 1,944 |

| 2004 | 864 | 97 | 240 | 1,871 |

| 2005 | 811 | 101 | 237 | 1,743 |

| 2006 | 772 | 106 | 245 | 1,652 |

| 2007 | 704 | 104 | 234 | 1,530 |

| 2008 | 635 | 97 | 238 | 1,425 |

| 2009 | 613 | 97 | 276 | 1,386 |

| 2010 | 579 | 90 | 268 | 1,286 |

| 2011 | 528 | 87 | 260 | 1,197 |

| 2012 | 508 | 80 | 264 | 1,175 |

| 2013 | 446 | 66 | 250 | 1,096 |

| 2014 | 429 | 59 | 265 | 1,069 |

| 2015 | 447 | 62 | 280 | 1,085 |

| 2016 | 444 | 61 | 285 | 1,091 |

| 2017 | 437 | 62 | 296 | 1,086 |

| 2018 | 433 | 61 | 337 | 1,100 |

| 2019 | 430 | 62 | 374 | 1,130 |

| 2020 | 362 | 51 | 239 | 904 |

|

Note: Populations are based upon July 1st estimates from Statistics Canada, Centre for Demography. Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics, Uniform Crime Reporting Survey. |

||||

Chart 3 end

In 2020, the rate of breaking and entering declined 16% nationally to 362 incidents per 100,000 population. Since peaking in 1991, the police-reported rate of breaking and entering has generally been declining in Canada. Over the last decade, the rate of breaking and entering has fallen 38%. Despite this decrease, breaking and entering continued to be one of the more common forms of property crime; just over 137,500 incidents were reported by police in 2020, accounting for 12% of property crime, the same proportion as the previous year.

All provinces and territories reported declines in breaking and entering in 2020, with rates from 11% to 33% lower across the country (Table 2). Given its relatively high volume and CSI weight, changes in rates of breaking and entering had a measurable impact on CSIs in all jurisdictions (see Text box 7 and Text box 10). In 2020, 30 out of 35 census metropolitan areas (CMAs)Note reported decreases or no change in breaking and entering (Table 3).

Using incident characteristics, it is possible to analyze changes in the location of breaking and entering incidents. Residential and commercial breaking and entering made up the vast majority (92%) of police-reported breaking and entering incidents in 2020.Note From 2019 to 2020, the number of residential break and enters decreased 18%, while the number of commercial break and enters decreased 9%. Comparing the first three months of the pandemic (March, April and May 2020) to the same period in 2019, the number of residential break and enters decreased 18%, while commercial break and entering incidents were 9% higher. Therefore, there was an uptick in commercial breaking and entering during the early months of the pandemic relatively to the same period a year earlier. Additionally, the number of residential break and enters in 2020 decreased month-over-month (e.g., March 2020 compared with February 2020) in March (-4%), April (-6%) and May (-7%), before increasing in June (+10%), July (+8%) and August (+10%). Commercial break and enters, on the other hand, increased in March (+15%) and April (+6%), before decreasing in May (-37%) and June (-3%) (July had no change and August increased 18%).

National rates of police-reported robbery, which had remained fairly stable over the last five years, dropped 18% from 62 incidents per 100,000 to 51 incidents per 100,000. Rates of robbery declined in all provinces and territories with the exceptions of Nova Scotia (+11%) and Yukon (+3%), and rates declined or remained the same in 25 of 35 CMAs.

In 2020, as could be expected given the nation-wide restrictions put in place to contain the pandemic, such as the temporary closures of many businesses or moves toward curbside pickup, the rates of shoplifting and theft of $5,000 or under both dropped in all provinces and territories, and in almost all CMAs (Peterborough reported an increase in theft of $5,000 or under, while Barrie remained unchanged). While both violations are less severe relative to breaking and entering or robbery, the volume of these crimes contributed to their relatively large impact on the CSI across the country. In 2020, police-reported about 90,900 incidents of shoplifting of $5,000 or under, representing a rate of 239 per 100,000 population, 36% lower than in 2019. Similarly, the rate of other theft of $5,000 or under dropped 20% from 1,130 to 904.

Rate of police-reported sexual assault down for the first time in five years

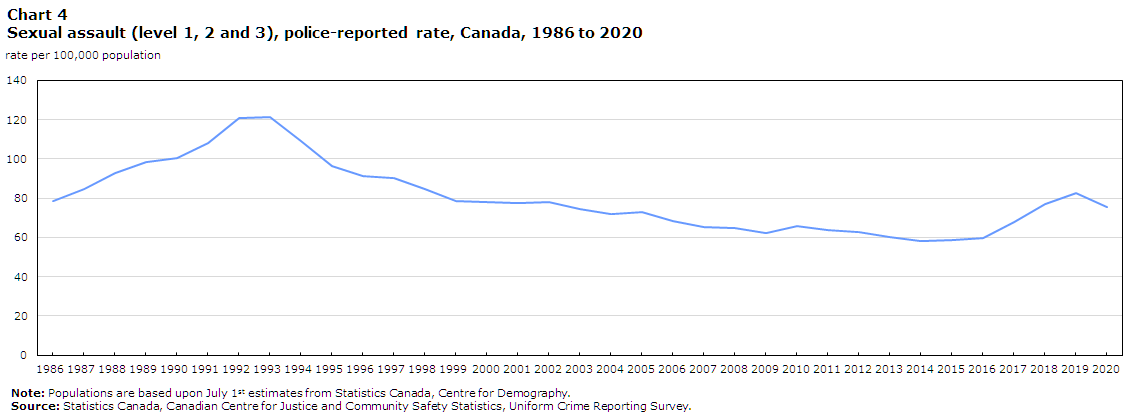

In 2020, there were 28,639 police-reported sexual assaults (level 1, 2 and 3), or 75 incidents per 100,000 population (Table 1). This rate was 9% lower than in 2019, marking the first decrease in sexual assault following five years of increases. This was also the largest decrease since a 12% decline in 1995 (Chart 4). From 2019 to 2020, the rate of police-reported sexual assault (level 1, 2 and 3) decreased in most provinces and territories, with the exceptions of Newfoundland and Labrador (+9%), Nunavut (+7%) and Quebec (+2%) (Table 2).Note

Chart 4 start

Data table for Chart 4

| Year | Rate per 100,000 population |

|---|---|

| 1986 | 79 |

| 1987 | 85 |

| 1988 | 93 |

| 1989 | 98 |

| 1990 | 101 |

| 1991 | 108 |

| 1992 | 121 |

| 1993 | 121 |

| 1994 | 109 |

| 1995 | 96 |

| 1996 | 91 |

| 1997 | 90 |

| 1998 | 85 |

| 1999 | 78 |

| 2000 | 78 |

| 2001 | 78 |

| 2002 | 78 |

| 2003 | 74 |

| 2004 | 72 |

| 2005 | 73 |

| 2006 | 68 |

| 2007 | 65 |

| 2008 | 65 |

| 2009 | 62 |

| 2010 | 66 |

| 2011 | 64 |

| 2012 | 63 |

| 2013 | 60 |

| 2014 | 58 |

| 2015 | 59 |

| 2016 | 60 |

| 2017 | 68 |

| 2018 | 77 |

| 2019 | 82 |

| 2020 | 75 |

|

Note: Populations are based upon July 1st estimates from Statistics Canada, Centre for Demography. Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics, Uniform Crime Reporting Survey. |

|

Chart 4 end

Despite considerable public discussion of issues around sexual violence in recent years, the number of sexual assaults reported by police is likely a significant underestimation of the true extent of sexual assault in Canada, as these types of offences often go unreported to police. The most recently available self-reported data from the 2019 General Social Survey on Canadians’ Safety (Victimization) show that only 6% of sexual assault incidents experienced by Canadians aged 15 and older in the previous 12 months were brought to the attention of police (Cotter forthcoming 2021). Similarly, data from the 2018 Survey of Safety in Public and Private Spaces indicate that police were informed about the most serious incident of sexual assault reported by 5% of the women who were victims for sexual assault in the 12 months preceding the survey (Cotter and Savage 2019).

Pandemic-related lockdown conditions could have exacerbated issues around underreporting of sexual assaults. With widespread stay-at-home orders and overburdened hospital and medical care resources, it may be more difficult for victims to come forward to report instances of sexual assault, and less likely that a third-party (for example a doctor or teacher) would identify signs of abuse, particularly for children and youth. There are some indications that family violence services and victims of family violence may also have been disproportionately impacted by the pandemic (see Text box 3).

In 2020, just under one in ten (9%) level 1 sexual assaults reported to police were classified as unfounded, meaning it had been determined through police investigation that the incident reported did not occur, nor was it attempted. This represents a continued decrease in unfounded incidents from a high of 14% in 2017 (Table 4). For comparison, the proportion of common physical assault (level 1) classified as unfounded dropped from 11% in 2017 to 9% in 2020. For more detailed information on the potential impact of unfounded criminal incidents in previous years, refer to Text box 2 in Moreau 2020.

Start of text box 3

Text box 3

Family violence during the pandemic

Starting in March 2020, many organizations within Canada and internationally raised concerns about increased domestic violence under lockdown restrictions brought in to address the COVID-19 pandemic (United Nations 2020; Vaeza 2020; WAGE 2021). Social isolation, loss of employment and reduced income may be factors that increase the risk of domestic violence and these conditions have been heightened since March 2020, particularly in periods with families confined at home, the closure of schools and child care facilities, and possible increased tension in the home.

In 2020, the overall rate of police-reported family violence remained unchanged from the previous year.Note In contrast, the rate of victims of non-family violence decreased 4% in 2020. Changes in the rates of family violence differed by age group. Rates for seniors increased for the fifth year in a row (+5%). The rate was also up in 2020 for adults aged 18 to 64 (+2%), continuing a four year upward trend. In contrast, after four years of increases, the police-reported rate of family violence among children decreased 5% between 2019 and 2020.

According to a web panel survey conducted in March 2020 asking Canadians how concerned they were about different situations, 10% of women and 6% of men reported that they were concerned about the possibility of violence in the home during the pandemic (Statistics Canada 2020b). A subsequent crowdsourcing initiativeNote conducted in April 2020 echoed this finding as women were more likely than men to report being very or extremely concerned about the possibility of violence in the home during the pandemic (8.7% vs 6.5%) (Statistics Canada 2020c).

As in previous years, the majority (6 in 10) of victims of family violence in 2020 were living with the accused at the time of the incident, potentially exacerbated by stay-at-home orders and restrictions on mobility throughout the pandemic. In addition, for those experiencing violence, especially within the home, contacting police or accessing help may have been more difficult because of restricted contact with networks and sources of support, both formal (schools, counsellors, and victim services) and informal (family and friends). A detailed Statistics Canada report on family violence during the pandemic is planned for release in the Fall, 2021.

End of text box 3

Continued increase in rate of police-reported child pornography

While many police-reported crimes declined during the pandemic, the rate of police-reported child pornographyNote increased 23% to 29 incidents per 100,000 population. This follows a 47% increase in 2019 and the rate has generally been trending upward since 2008 (Chart 5).Note Note In 2020, police reported 2,178 more incidents than in 2019 (Table 1). Circumstances of the pandemic have been noted as potentially exacerbating the conditions for victimization, especially with children and youth spending more time online (BC Gov News 2021; Public Safety Canada 2020). According to Cybertip.ca, Canada’s national tip line for reporting child sexual exploitation online, more than 4 million exploitation reports have been processed between 2002 and 2020, the vast majority of which were reported from 2017 onward (Cybertip 2021).Note

Chart 5 start

Data table for Chart 5

| Year | Rate per 100,000 population |

|---|---|

| 2008 | 4 |

| 2009 | 4 |

| 2010 | 5 |

| 2011 | 6 |

| 2012 | 6 |

| 2013 | 8 |

| 2014 | 11 |

| 2015 | 12 |

| 2016 | 18 |

| 2017 | 18 |

| 2018 | 16 |

| 2019 | 24 |

| 2020 | 29 |

|

Note: Since 2015, reporting requirements for total child pornography include separate violations for accessing or possessing child pornography, and making or distributing child pornography, which, combined, make up total child pornography. Prior to 2015, different child pornography offences were reported simply as child pornography. Due to the complexity of these cyber incidents, the data likely reflect the number of active or closed investigations for the year rather than the total number of incidents reported to police. Data are based on police-reported incidents that are recorded in police services’ records management systems. The offence of “child pornography” includes offences under section 163.1 of the Criminal Code which makes it illegal to access, possess, make, print, or distribute child pornography. When the actual victim is not identified, this offence is reported to the Uniform Crime Reporting Survey with the most serious offence being “child pornography” which falls under the larger crime category of “other Criminal Code offences”. In cases where an actual victim is identified, police will report the most serious offence as sexual assault, sexual exploitation or other sexual violations against children, which fall under the category of “violent crimes” and child pornography may be reported as a secondary violation. Populations are based upon July 1st estimates from Statistics Canada, Centre for Demography. Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics, Uniform Crime Reporting Survey. |

|

Chart 5 end

Among the provinces, most reported increases in the rate of child pornography incidents from 2019 to 2020, including Prince Edward Island (+4%), Nova Scotia (+55%), New Brunswick (+81%), Quebec (+30%), Ontario (+2%), Manitoba (+32%) and British Columbia (+44%). The majority of the national increase was due to more incidents in British Columbia (+1,465 incidents, +44% rate) and Quebec (+417 incidents, +30% rate).

Among the CMAs, Vancouver (+870 incidents), Montréal (+351 incidents), Winnipeg (+144 incidents) and Victoria (+129 incidents) reported the largest increases in the number of child pornography violations. Together, these four CMAs represented 75% of the increase in incidents in child pornography among CMAs from 2019 to 2020.

As in 2019, these particularly large increases in total child pornography incidents may be attributed in part to an increase in the number of cases forwarded to local police services by the RCMP’s National Child Exploitation Coordination Centre (NCECC), which serves as the national law enforcement arm of the National Strategy for the Protection of Children from Sexual Exploitation on the Internet. In 2019, Public Safety Canada announced the expansion of the National Strategy with increased funding over three years to support awareness of online child sexual exploitation, reduce stigma of reporting, and increase Canada’s ability to pursue and prosecute offenders of sexual exploitation of children online (Public Safety Canada 2019a). Additionally, part of the increase in British Columbia could be the result of work initiated by the British Columbia Behavioural Sciences Group – Integrated Child Exploitation Unit (BSG) in 2014. The BSG uses software developed by the Child Rescue Coalition to identify computers located in the province that were used to access or share child pornography on the Internet, from which they could open an investigation (for more information on the software see Child Rescue Coalition 2020).

Another factor cited by police services that may have contributed to the increase in rates of total child pornography is the continued compliance with former Bill C-22 “An Act respecting the mandatory reporting of Internet child pornography by persons who provide an Internet service (2011).” Essentially, the Act requires that persons or entities providing an Internet service to the public must report known or suspected offences of child pornography to the police.

In 2020, there were over 7,200 cybercrime-related child pornography violations, up 35% from 5,375 violations in 2019.Note

Police-reported opioid drug offences were the only specific drug type to experience an increase in 2020

According to the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC), the COVID-19 pandemic is worsening the ongoing public health crisis of opioid overdose deaths and hospitalizations. Between January 2016 and December 2020, PHAC reported 21,174 apparent opioid toxicity deaths occurred in Canada. In the first nine months following the implementation of COVID-19 prevention measures (April to December 2020), there were 5,148 opioid-related deaths, an 89% increase from the same period in 2019. Of all accidental apparent opioid toxicity deaths in 2020, 82% involved fentanyl or fentanyl analogues. Opioid-related deaths and hospitalizations have also been linked to the use of stimulants such as cocaine and methamphetamine, reflecting the polysubstance nature of the crisis (Special Advisory Committee on the Epidemic of Opioid Overdoses 2021).Note

A number of factors were cited as possible contributors to a worsening of the opioid overdose crisis during the pandemic, including the increasingly toxic drug supply, increased feelings of isolation, stress and anxiety and limited availability or accessibility of services for people who use drugs (Special Advisory Committee on the Epidemic of Opioid Overdoses 2021).

In 2020, there were 5,142 opioid-related offences in Canada, representing a rate of 14 per 100,000 population, a 34% increase compared to 2019 (Table 5).Note All opioid-related drug violations increased, including more possession, trafficking, production and importation or exportation offences (Table 6). Among the provinces, the highest rates were reported in British Columbia (54 per 100,000 population), Alberta (12) and Ontario (10) (Table 5). The CMAs with the highest rates of opioid-related offences were Kelowna (208 per 100,000 population) and Lethbridge (97), followed by Vancouver (43), Guelph (32), Abbotsford-Mission (31), Kitchener-Cambridge-Waterloo (30) and St. Catharines-Niagara (29). In terms of opioid-related deaths, Western Canada continues to be the most impacted region of the country since 2016, but rates have begun to increase in other areas as well, notably in Ontario (Special Advisory Committee on the Epidemic of Opioid Overdoses 2021).

Opioid-related offences were the only specific drug type to experience an increase in 2020 compared to 2019; police-reported rates of cannabis (-25%), heroin (-15%), ecstasy (-7%), methamphetamine (-5%) and cocaine-related drug offences (-2%) all decreased. Overall, police-reported rates of cocaine (40 incidents per 100,000 population), methamphetamine (37), cannabis (33) and opioid-related offences (14) were highest among the specific drug types (Table 5).

While the rates of these other drug types decreased, the polysubstance nature of the opioid crisis may impact how particular drug offences, namely those related to methamphetamine and cocaine, are reported, given that only one drug type will be indicated as the most serious violation for a particular criminal incident. According to data reported by PHAC from six provinces and territories, around half (52%) of accidental opioid toxicity deaths in 2020 also involved a stimulant. Of these deaths, 68% involved cocaine, while 47% involved methamphetamines. Similarly, 84% of deaths identified as apparent stimulant toxicity deaths also involved an opioid over the same time period.

Rates of police-reported cannabis offences continue to drop

Nationally, rates of police-reported cannabis offences continued to drop two years after the legalization of cannabis on October 17, 2018. The Cannabis Act provides a legal framework for the legalization and regulation of the production, distribution, sale, possession, importation and exportation of cannabis in Canada (Parliament of Canada 2018).

According to the National Cannabis Survey, in the fourth quarter of 2020, 20% of Canadians 15 years and older consumed cannabis in the three months preceding the survey, up 2% from the first quarter of 2019 (following legalization), and 6% from the first quarter of 2018 (prior to legalization). Over the same time period, the proportion of consumers who reported getting cannabis from a legal source rose from 23% to 68%, while the proportion who reported getting cannabis from an illegal source dropped from 51% to 35% (respondents could select more than one source, therefore the percentages do not add up to 100%). Furthermore, the number of legal retail cannabis stores in Canada increased nearly eightfold since the fourth quarter of 2018, from 182 stores to 1,445 (Rotermann 2021).

Since 2012, national police-reported rates of cannabis-related drug offences have been declining, with notable decreases from 2018 to 2020 (Chart 6). In 2020, there were just over 66,800 total drug offences reported by police, representing a rate of 176 per 100,000 population, of which cannabis-related drug offences accounted for 19%Note (Table 6). As would be expected following legalization, this is by far the lowest proportion of cannabis offences relative to all drug-related offences; from 1986 to 2015, cannabis offences accounted for, on average, 68% of all drug-related offences.

Chart 6 start

Data table for Chart 6

| Year | CannabisData table for Chart 6 Note 1 | CocaineData table for Chart 6 Note 2 | Other drugsData table for Chart 6 Note 2 Data table for Chart 6 Note 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| rate per 100,000 population | |||

| 1986 | 159 | 26 | 31 |

| 1987 | 163 | 31 | 39 |

| 1988 | 149 | 41 | 31 |

| 1989 | 148 | 59 | 39 |

| 1990 | 140 | 46 | 33 |

| 1991 | 119 | 57 | 28 |

| 1992 | 123 | 50 | 34 |

| 1993 | 125 | 44 | 29 |

| 1994 | 140 | 43 | 25 |

| 1995 | 150 | 39 | 22 |

| 1996 | 160 | 39 | 24 |

| 1997 | 160 | 38 | 24 |

| 1998 | 169 | 40 | 26 |

| 1999 | 197 | 39 | 27 |

| 2000 | 216 | 42 | 29 |

| 2001 | 219 | 39 | 30 |

| 2002 | 222 | 41 | 33 |

| 2003 | 193 | 45 | 36 |

| 2004 | 213 | 53 | 40 |

| 2005 | 188 | 60 | 43 |

| 2006 | 183 | 69 | 44 |

| 2007 | 191 | 70 | 47 |

| 2008 | 197 | 66 | 45 |

| 2009 | 195 | 52 | 44 |

| 2010 | 221 | 51 | 49 |

| 2011 | 228 | 51 | 51 |

| 2012 | 212 | 53 | 52 |

| 2013 | 210 | 49 | 52 |

| 2014 | 194 | 46 | 56 |

| 2015 | 171 | 43 | 66 |

| 2016 | 154 | 40 | 73 |

| 2017 | 136 | 38 | 80 |

| 2018 | 99 | 39 | 91 |

| 2019 | 44 | 41 | 101 |

| 2020 | 33 | 40 | 102 |

Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics, Uniform Crime Reporting Survey. |

|||

Chart 6 end

In 2020, the rate of cannabis-related incidents under the Cannabis Act and Controlled Drugs and Substances Act dropped 25% from the previous years.Note Police reported a total of 12,591 incidents, representing a rate of 33 incidents per 100,000 population. The most commonly reported offences were related to importation or exportation (61% of all Cannabis Act offences), possession (11%), and distribution (9%) (Table 6). By comparison, in 2018, prior to the legalization of cannabis, possession accounted for three-quarters (75%) of cannabis offences. Due to legalization under the Cannabis Act, possession is only illegal under certain circumstances.

In the first year of the pandemic, the rate of offences related to importation or exportation accounted for the largest decrease among Cannabis Act offences, dropping 31% from 29 incidents per 100,000 to 20 incidents per 100,000. In total, there were 3,211 fewer incidents of importation or exportation under the Cannabis Act in 2020. The Montréal CMA in Quebec accounted for the majority of the national decrease in importation or exportation offences reported under the Cannabis Act, decreasing 72% (4,180 fewer incidents) from 2019 to 2020. The large decrease in offences year-over-year was due in part to fewer postal seizures and seizures conducted by the Canada Border Services Agency in Montréal since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. Additionally, the Vancouver CMA in British Columbia accounted for 56% of all importation or exportation offences reported under the Cannabis Act (4,194 of the 7,552 offences reported nationally). The high proportion of offences was due in part to seizure cases, conducted by the Canada Border Services Agency and the Canada Post Mail Centre in the Vancouver CMA, being forwarded for processing and investigation. As a result of this exchange, the year in which occurrences were reported by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police may not always correspond to the year in which they occurred.

Provincially, the rates of cannabis offences in British Columbia (102 per 100,000 population) and Quebec (42 per 100,000 population) were higher than the national rate (33 per 100,000 population) (Table 5). Historically, British Columbia reported the highest rates of cannabis-related drug offences under the CDSA legislation relative to the other provinces, while Quebec reported the second highest rates in 2017 and 2018.

Increases in offences related to harassing and threatening behaviours

In contrast to the fairly widespread declines in many types of crime in 2020, Canada saw continued increases in the rates of various criminally harassing and threatening behaviours. In particular, non-consensual distribution of intimate images (+229 incidents, +10% rate), uttering threats (+3,343 incidents, +3% rate), criminal harassment (+1,174 incidents, +4% rate per 100,000 population), and indecent or harassing communications (+2,471 incidents, +9% rate) all saw increases compared with 2019 (Table 1; Chart 7).

Chart 7 start

Data table for Chart 7

| Year | Uttering threats | Criminal harassment | Indecent or harassing communications | Non-consensual distribution of intimate images |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| rate per 100,000 population | ||||

| 2009 | 234 | 59 | 69 | Note ...: not applicable |

| 2010 | 225 | 63 | 64 | Note ...: not applicable |

| 2011 | 209 | 63 | 59 | Note ...: not applicable |

| 2012 | 203 | 64 | 54 | Note ...: not applicable |

| 2013 | 182 | 61 | 47 | Note ...: not applicable |

| 2014 | 176 | 55 | 39 | Note ...: not applicable |

| 2015 | 176 | 56 | 41 | 1 |

| 2016 | 169 | 53 | 42 | 2 |

| 2017 | 173 | 54 | 45 | 4 |

| 2018 | 180 | 53 | 48 | 4 |

| 2019 | 215 | 62 | 62 | 5 |

| 2020 | 221 | 64 | 68 | 6 |

|

... not applicable Note: Indecent or harassing communications was amended in the Protecting Canadians from Online Crime Act: Bill C-13 (2015) to include all means of telecommunication, not only phone calls. Non-consensual distribution of intimate images is an offence created by the Protecting Canadians from Online Crime Act: Bill C-13 (2015), therefore only data from 2015 to 2020 is shown. Populations are based upon July 1st estimates from Statistics Canada, Centre for Demography. Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics, Uniform Crime Reporting Survey. |

||||

Chart 7 end

In addition to legislative amendments and new offences that came into force in 2015 by the former Bill-C13 “Protecting Canadians from Online Crime Act,”Note Note the national increases in harassing and threatening offences can be attributed, in part, to increases in the accessibility and use of the Internet and social media. In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, individuals are using computers and the Internet more often for school, work and socializing, potentially affording more opportunities for criminal violations that do not require a physical presence. For instance, in 2020, there were over 14,900 cybercrime-related harassing and threatening behaviour violations, up 17% from 2019.Note The perceived anonymity of the Internet and social media can facilitate criminal harassment, uttering threats and indecent and harassing behaviours (Dhillon 2012; Perrin 2018). In addition, advancements in cell phone technology and the availability of cloud-based sharing platforms could have contributed to the increases seen in the non-consensual distribution of intimate images. Increased focus on the enforcement and reporting accuracy of cybercrime, and increased awareness of cybercrime by both the public and police may have also contributed to the change.

Start of text box 4

Text box 4

Police-reported hate crime during the COVID-19 pandemic

During the pandemic, various issues related to safety and discrimination were exposed and exacerbated in Canada, including hate crime. According to a crowdsourcing initiativeNote conducted by Statistics Canada, in the early months of the pandemic, the proportion of participants designated as visible minorities who perceived an increase in race-based harassment or attacks was three times larger than the proportion among the rest of the population (18% versus 6%) (Statistics Canada 2020d). This difference was most pronounced among Chinese (30%), Korean (27%), and Southeast Asian (19%) participants.

Hate crimes target the integral and visible parts of a person's identity and may disproportionately affect the wider community. A hate crime incident may be carried out against a person or property and may target race, colour, national or ethnic origin, religion, sexual orientation, gender identity or expression, language, sex, age, mental or physical disability, or any other similar factor. In addition, four specific offences are listed as hate propaganda or hate crimes in the Criminal Code of Canada: advocating genocide, public incitement of hatred, willful promotion of hatred and mischief motivated by hate in relation to property used by an identifiable group.

The number of police-reported hate crimes in Canada increased by 37% in 2020, rising from 1,951 incidents to 2,669. This marks the largest number of police-reported hate crimes recorded since comparable data became available in 2009. Police-reported hate crimes targeting race or ethnicity almost doubled (+80%) compared with the previous year, accounting for the vast majority of the national increase in hate crimes. Ontario (+321 incidents targeting race or ethnicity), British Columbia (+196 incidents) and Alberta (+105 incidents) reported the biggest increases.

Much of the rise in police-reported hate crimes targeting race or ethnicity was the result of crimes targeting the Black population (+318 incidents or +92%), the East or Southeast Asian populationNote (+202 incidents or +301%), the Indigenous populationNote (+44 incidents or +152%), and the South Asian populationNote (+38 incidents or +47%). In 2020, police reported the highest number of hate crimes targeting each of these populations since comparable data have been available.

Police-reported hate crimes targeting religion were down as a result of fewer incidents targeting the Muslim population (-100 incidents),Note while incidents targeting the Jewish population rose slightly (+15 incidents). Hate crimes targeting sexual orientation dropped slightly (-6 incidents) after a peak in 2019. Among all hate crimes, both non-violent (+42%) and violent (+30%) hate crimes increased in 2020.

Police data on hate crimes reflect only those incidents that come to the attention of police and that are subsequently classified as hate crimes. As a result, fluctuations in the number of reported incidents may be attributable to a true change in the volume of hate crimes, but they might also reflect changes in reporting by the public because of increased community outreach by police or heightened sensitivity after high-profile events.

A detailed analytical Juristat on police-reported hate crime in Canada for the year 2020 will be released in early 2022.

| Detailed motivation | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| number | percent | number | percent | number | percent | |

| Race or ethnicity | 793 | 44 | 884 | 46 | 1,594 | 62 |

| Black | 295 | 16 | 345 | 18 | 663 | 26 |

| East or Southeast Asian | 60 | 3 | 67 | 4 | 269 | 11 |

| South Asian | 84 | 5 | 81 | 4 | 119 | 5 |

| Arab or West Asian | 93 | 5 | 125 | 7 | 123 | 5 |

| Indigenous (First Nations, Métis or Inuit) | 39 | 2 | 29 | 2 | 73 | 3 |

| White | 42 | 2 | 48 | 3 | 81 | 3 |

| Other race or ethnicityText box 4 Note 1 | 163 | 9 | 150 | 8 | 193 | 8 |

| Race or ethnicity not specified | 17 | 1 | 39 | 2 | 73 | 3 |

| Religion | 657 | 37 | 613 | 32 | 515 | 20 |

| Jewish | 372 | 21 | 306 | 16 | 321 | 13 |

| Muslim | 166 | 9 | 182 | 10 | 82 | 3 |

| Catholic | 44 | 2 | 51 | 3 | 42 | 2 |

| Other religionText box 4 Note 2 | 52 | 3 | 57 | 3 | 41 | 2 |

| Religion not specified | 23 | 1 | 17 | 1 | 29 | 1 |

| Sexual orientation | 186 | 10 | 265 | 14 | 259 | 10 |

| Other motivationText box 4 Note 3 | 159 | 9 | 150 | 8 | 189 | 7 |

| Motivation unknown | 22 | Note ...: not applicable | 39 | Note ...: not applicable | 112 | Note ...: not applicable |

| Total | 1,817 | 100 | 1,951 | 100 | 2,669 | 100 |

... not applicable

Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics, Incident-based Uniform Crime Reporting Survey. |

||||||

End of text box 4

Increase in rate of Criminal Code firearm offences for sixth consecutive year

The Criminal Code specifies a number of violent offences involving the use of a firearm, including discharging a firearm with intent, pointing a firearm and using a firearm in the commission of an indictable offence.Note More serious crimes, however, such as homicide, robbery, assault and sexual assault, may have also involved a firearm. To measure all violent firearm-related crime, information on the incident characteristics must be used. In 2020, there were 8,344 victims of violent crime where a firearm was present during the commission of the offence, or a rate of 29 per 100,000 population.Note This rate was unchanged compared to 2019 (29); since reaching its lowest point in recent years in 2013, firearm-related violent crime has generally been increasing, with the exception of a decline between 2017 and 2018.Note

Among violent offences involving the use of a firearm that are specified in the Criminal Code, 45% in 2020 were for discharging a firearm with intent, while another 40% were for pointing a firearm. The remaining 15% were for using a firearm in the commission of an indictable offence. The number of violent offences specific to firearms increased by 593 incidents in 2020 (from 3,544 in 2019 to 4,137 in 2020), resulting in a 15% rate increase (Table 1). This marks the sixth consecutive annual increase. Rates rose across all three violent firearm violations: discharging a firearm with intent (+21%, +339 incidents), pointing of a firearm (+14%, +227 incidents), and using a firearm in the commission of an indictable offence (+3%, +27 incidents). Much of the increase in firearm-related offences in 2020 was the result of more incidents in Alberta (+185), Quebec (+148) and Ontario (+132).

Additionally, the rate of non-violent weapons violations (e.g., possession of weapons and unsafe storage of firearms) has increased for the sixth consecutive year, rising 3% to 51 incidents per 100,000 population (Table 1). The vast majority (91%) of these violations were related to possession of weapons offences and breach offences for weapons possession contrary to an order.

Police-reported fraud stable, with differences in fraud sub-types

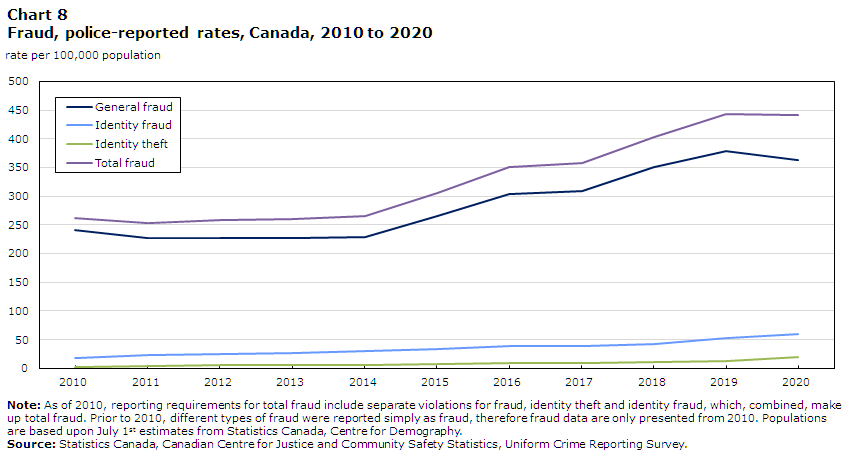

The rate of police-reported total fraud did not increase for the first time in nine years, remaining essentially stable (the rate was 443 per 100,000 population in 2019 and 442 in 2020); the rate was 69% higher than the rate reported a decade ago (Chart 8; Table 1).Note The overall stability was the result of offsetting changes in different types of fraud: general fraud, the most voluminous type of fraud, declined 4% from 2019 to 2020, while rates for identity fraud (+12%) and identity theft (+52%) increased.

Chart 8 start

Data table for Chart 8

| Year | General fraud | Identity fraud | Identity theft | Total fraud |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| rate per 100,000 population | ||||

| 2010 | 240 | 18 | 2 | 261 |

| 2011 | 226 | 23 | 4 | 254 |

| 2012 | 227 | 26 | 5 | 258 |

| 2013 | 227 | 27 | 6 | 260 |

| 2014 | 229 | 30 | 6 | 266 |

| 2015 | 264 | 33 | 7 | 305 |

| 2016 | 304 | 39 | 9 | 351 |

| 2017 | 310 | 39 | 9 | 358 |

| 2018 | 351 | 43 | 10 | 404 |

| 2019 | 378 | 53 | 13 | 443 |

| 2020 | 363 | 59 | 19 | 442 |

|

Note: As of 2010, reporting requirements for total fraud include separate violations for fraud, identity theft and identity fraud, which, combined, make up total fraud. Prior to 2010, different types of fraud were reported simply as fraud, therefore fraud data are only presented from 2010. Populations are based upon July 1st estimates from Statistics Canada, Centre for Demography. Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics, Uniform Crime Reporting Survey. |

||||

Chart 8 end

Despite the dip in fraud, new or evolving scams continue to draw the attention of the Canadian Anti-fraud Centre (CAFC) and the news media, particularly those involving tax returns with the Canada Revenue Agency, COVID-19-related scams including Canada Emergency Response Benefit (CERB) scams, fake vaccines and fake test results, as well as other general online, telephone or text message scams (CAFC 2021). A recent survey on cyber security during the pandemic shows that just over 4 in 10 Canadians (42%) experienced at least one type of cyber security incident since the beginning of the pandemic, including phishing attacks, malware, fraud, and hacked accounts (Statistics Canada 2020a). Of those who experienced a cyber security incident, less than one-third (29%) reported the incident to a relevant service provider, financial institution or credit card company, and just 5% of individuals reported the incident to an authority such as the police. According to the Canadian Anti-Fraud Centre, from March 2020 to May 2021, there were 19,610 victims and $7.4 million lost due to COVID-related fraud alone.

While fraud is not an especially severe crime in the CSI, it is a relatively high-volume crime, which contributed to making fraud, typically general fraud, an important driver of the CSI and Non-Violent CSI in several jurisdictions in Canada (see Text box 7 and Text box 10).

Among the provinces, Western Canada, the Prairies and Ontario reported decreases in the rate of total fraud, while Quebec and the Atlantic provinces (excluding Newfoundland and Labrador) reported increases (Table 2). In each province and territory, there was a year-over-year increase in at least one fraud sub-type. Total fraud decreased in 20 of 35 CMAs in 2020 (Table 3).

Start of text box 5

Text box 5

Police involvement in enforcing measures to help manage the pandemic and the

administration of justice

Police involvement in enforcing measures to help manage the pandemic

Early in the pandemic, in an effort to minimize the impact and spread of the virus, the Government of Canada enacted regulatory amendments under the Contraventions Act. These amendments allow law enforcement agencies to issue tickets to individuals who do not comply with orders under the Quarantine Act.Note In 2020, police reported 931 incidents under the Quarantine Act. The majority of these incidents were reported in British Columbia (348 incidents), Ontario (231 incidents), Alberta (156 incidents) and Quebec (90 incidents).

As a complementary measure to police-reported violations of the Quarantine Act, the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) has been forwarding referrals for compliance verification to the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP). To limit the spread of COVID-19, the Government of Canada implemented emergency orders in March 2020 requiring a mandatory 14-day quarantine or isolation for all travellers entering Canada. From April 1, 2020 to June 28, 2021, according to data from PHAC, the agency had sent the RCMP 110,831 high priority referrals for compliance verification, based on police capacity and resources. This resulted in 102,483 law enforcement follow-ups that were reported to the Agency by June 28. Enforcement actions have resulted in 2,871 fines for offences under the Quarantine Act, and 16 court summons for charges laid under the Quarantine Act.

Canadian courts and corrections

Prior to COVID-19, Canadian criminal courts were experiencing challenges with timely case processing, resulting in a Supreme Court of Canada decision (R. v. Jordan 2016) which set out new timelines for case completion (R. v. Jordan 2016, Karam et al. 2020). As a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, many courts across the country were unable to continue operating at normal capacity, which in some cases caused lengthy delays. Delays can have an adverse impact on persons accused of committing a crime, as well as offenders, victims and witnesses (Statistics Canada 2021a).

Additionally, the Canadian custodial population saw an unprecedented decrease during the early months of the pandemic (Statistics Canada 2021b). While balancing public safety concerns, reducing the number of persons held in correctional institutions was seen as a preventive measure to reduce the public health risk associated with COVID-19 transmission for those in custody and correctional staff. During March and April 2020, the first months of the COVID-19 pandemic, there was a historic decline of 15% in the number of adults in Canadian correctional institutions. In May and June 2020, the declines slowed, and from July to November, the average daily count of adults in custody increased slightly every month. In December, when confirmed COVID-19 cases in Canada were on the rise during a second wave of infections, the average daily count of adults in custody decreased slightly (-2%) (Statistics Canada 2021b).

Potentially as a consequence of the reduced activity in Canadian courts and corrections, the rate of administration of justice violationsNote declined 17% in 2020, after having increased each of the previous five years. The majority of administration of justice violations are for failure to comply with an order (63%), breach of probation (20%) and failure to appear (11%). The rates of all three violations decreased substantially: failure to appear (-42%), breach of probation (-23%), and failure to comply with an order (-6%).

End of text box 5

Police-reported crime in Canada – General trends in Crime Severity Index and crime rate

Canada’s Crime Severity Index decreases, following five years of increases

The Crime Severity Index (CSI) measures both the volume and severity of police-reported crime in Canada and has a base index value of 100 for 2006 (Text box 5). The CSI dropped 8% from 79.8 in 2019 to 73.4 in 2020, the first decrease following five years of increases (Table 7; Chart 9). Between 1998 and 2014, however, the CSI had steadily declined, with the exception of a 3% increase reported in 2003. The 2020 CSI was 11% lower than a decade prior.

Chart 9 start

Data table for Chart 9

| Year | Crime Severity Index | Violent Crime Severity Index | Non-violent Crime Severity Index |

|---|---|---|---|

| index | |||

| 1998 | 118.8 | 97.8 | 126.9 |

| 1999 | 111.2 | 99.4 | 115.8 |

| 2000 | 106.7 | 97.8 | 110.2 |

| 2001 | 105.3 | 97.2 | 108.4 |

| 2002 | 104.1 | 96.2 | 107.2 |

| 2003 | 106.8 | 97.6 | 110.4 |

| 2004 | 104.1 | 96.0 | 107.2 |

| 2005 | 101.3 | 98.5 | 102.4 |

| 2006 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| 2007 | 95.3 | 97.8 | 94.3 |

| 2008 | 90.6 | 95.1 | 88.9 |

| 2009 | 87.8 | 94.3 | 85.3 |

| 2010 | 82.9 | 89.2 | 80.5 |

| 2011 | 77.6 | 85.7 | 74.5 |

| 2012 | 75.5 | 82.0 | 73.0 |

| 2013 | 68.9 | 74.0 | 66.9 |

| 2014 | 66.9 | 70.7 | 65.4 |

| 2015 | 70.4 | 75.3 | 68.4 |

| 2016 | 72.0 | 76.9 | 70.1 |

| 2017 | 73.6 | 81.3 | 70.7 |

| 2018 | 75.6 | 83.6 | 72.6 |

| 2019 | 79.8 | 90.3 | 75.8 |

| 2020 | 73.4 | 87.0 | 68.4 |

|

Note: Crime Severity Indexes are based on Criminal Code incidents, including traffic offences, as well as other federal statute violations. The base index was set at 100 for 2006 for Canada. Populations are based upon July 1st estimates from Statistics Canada, Centre for Demography. Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics, Uniform Crime Reporting Survey. |

|||

Chart 9 end

The first year of the pandemic was marked by widespread changes to how people live, work and interact with others as a result of varying lockdowns, stay-at-home orders and other restrictions. The 8% decline in the CSI in 2020 was driven by decreases in police-reported rates for numerous offences, primarily those related to property crime. Most notably, there were decreases in police-reported breaking and entering, theft of $5,000 or under,Note robbery, shoplifting of $5,000 or under, administration of justice violations and sexual assault (level 1).

At 5,301 incidents per 100,000 population, the police-reported crime rate—which measures the volume of crime per 100,000 population—decreased 10% in 2020 (Table 8; Chart 10).

Chart 10 start

Data table for Chart 10

| Year | Total | Property crimes | Other crimes | Violent crimes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| rate per 100,000 population | ||||

| 1962 | 2,771 | 1,891 | 659 | 221 |

| 1963 | 3,022 | 2,047 | 726 | 249 |

| 1964 | 3,245 | 2,146 | 815 | 284 |

| 1965 | 3,199 | 2,091 | 809 | 299 |

| 1966 | 3,511 | 2,258 | 907 | 347 |

| 1967 | 3,850 | 2,484 | 985 | 381 |

| 1968 | 4,336 | 2,826 | 1,087 | 423 |

| 1969 | 4,737 | 3,120 | 1,164 | 453 |

| 1970 | 5,212 | 3,515 | 1,217 | 481 |

| 1971 | 5,311 | 3,649 | 1,170 | 492 |

| 1972 | 5,355 | 3,634 | 1,224 | 497 |

| 1973 | 5,773 | 3,704 | 1,546 | 524 |

| 1974 | 6,388 | 4,151 | 1,684 | 553 |

| 1975 | 6,852 | 4,498 | 1,769 | 585 |

| 1976 | 6,984 | 4,533 | 1,867 | 584 |

| 1977 | 6,971 | 4,466 | 1,933 | 572 |

| 1978 | 7,154 | 4,579 | 1,995 | 580 |

| 1979 | 7,666 | 4,903 | 2,153 | 610 |

| 1980 | 8,343 | 5,444 | 2,263 | 636 |

| 1981 | 8,736 | 5,759 | 2,322 | 654 |

| 1982 | 8,773 | 5,840 | 2,262 | 671 |

| 1983 | 8,470 | 5,608 | 2,182 | 679 |

| 1984 | 8,387 | 5,501 | 2,185 | 701 |

| 1985 | 8,413 | 5,451 | 2,227 | 735 |

| 1986 | 8,727 | 5,550 | 2,392 | 785 |

| 1987 | 8,957 | 5,553 | 2,575 | 829 |

| 1988 | 8,919 | 5,439 | 2,613 | 868 |

| 1989 | 8,892 | 5,289 | 2,692 | 911 |

| 1990 | 9,485 | 5,612 | 2,900 | 973 |

| 1991 | 10,342 | 6,160 | 3,122 | 1,059 |

| 1992 | 10,040 | 5,904 | 3,052 | 1,084 |

| 1993 | 9,538 | 5,575 | 2,881 | 1,082 |

| 1994 | 9,125 | 5,257 | 2,821 | 1,047 |

| 1995 | 9,008 | 5,292 | 2,707 | 1,009 |

| 1996 | 8,932 | 5,274 | 2,656 | 1,002 |

| 1997 | 8,475 | 4,880 | 2,603 | 993 |

| 1998 | 8,093 | 4,569 | 2,529 | 995 |

| 1999 | 7,695 | 4,276 | 2,449 | 971 |

| 2000 | 7,610 | 4,081 | 2,534 | 996 |

| 2001 | 7,592 | 4,004 | 2,593 | 995 |

| 2002 | 7,516 | 3,976 | 2,560 | 980 |

| 2003 | 7,773 | 4,125 | 2,670 | 978 |

| 2004 | 7,601 | 3,976 | 2,668 | 957 |

| 2005 | 7,326 | 3,744 | 2,620 | 962 |

| 2006 | 7,246 | 3,605 | 2,673 | 968 |

| 2007 | 6,908 | 3,335 | 2,621 | 952 |

| 2008 | 6,632 | 3,096 | 2,598 | 938 |

| 2009 | 6,462 | 3,005 | 2,531 | 926 |

| 2010 | 6,160 | 2,802 | 2,451 | 907 |

| 2011 | 5,781 | 2,586 | 2,325 | 870 |

| 2012 | 5,639 | 2,524 | 2,272 | 843 |

| 2013 | 5,207 | 2,348 | 2,089 | 769 |

| 2014 | 5,062 | 2,328 | 1,998 | 736 |

| 2015 | 5,232 | 2,437 | 2,040 | 755 |

| 2016 | 5,298 | 2,490 | 2,039 | 769 |

| 2017 | 5,375 | 2,523 | 2,060 | 791 |

| 2018 | 5,513 | 2,625 | 2,068 | 819 |

| 2019 | 5,878 | 2,734 | 2,259 | 886 |

| 2020 | 5,301 | 2,265 | 2,193 | 843 |

|

Note: Information presented in this chart represents data from the Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR1) Aggregate Survey, and permits historical comparisons back to 1962. New definitions of crime categories were introduced in 2009 and are only available in the new format back to 1998. As a result, numbers in this chart will not match data released in the new UCR2 format. Specifically, the definition of violent crime has been expanded. In addition, UCR1 includes some different offences in the "other crimes" category. Populations are based upon July 1st estimates from Statistics Canada, Centre for Demography. Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics, Uniform Crime Reporting Survey. |

||||

Chart 10 end

Canadian police services reported just over 2 million Criminal Code incidents (excluding traffic) in 2020, about 195,000 fewer incidents than in 2019. In addition, there were about 125,200 Criminal Code traffic offences, about 66,800 CDSA and Cannabis Act offences, and about 18,800 other federal statute violations (such as offences under the Youth Criminal Justice Act and the Customs Act) recorded by police in 2020. In total, there were over 2.2 million police-reported Criminal Code and “other federal statute” violations in 2020.

Although the CSI and the crime rate are separate measures, with the CSI accounting not only for volume but also changes in the relative severity of police-reported crime (Text box 6), both measures show similar trends in police-reported crime in Canada since 1998.

Start of text box 6

Text box 6

Measuring police-reported crime

In Canada, there are two complementary ways to measure police-reported crime: the traditional crime rate and the Crime Severity Index (CSI). While both measures take into account the volume of police-reported crime, the CSI also accounts for the severity of crime. Both the traditional crime rate and the CSI measure crime based on the most serious violation in the criminal incident (see “Survey description” for more details). The most serious violation is determined by criteria in the following order of priority: violations against a person take precedence over violations not against a person, the greatest maximum penalty prescribed by law, violations causing death take precedence over other violations with the same maximum penalty and—if the above rules do not break a tie—the police service uses discretion to determine which is the most serious violation in the incident.Note

To publish the most timely police-reported crime statistics, this article relies on aggregate data (totals), which are the first crime data available each calendar year. More detailed data on the characteristics of incidents, victims and accused persons will be available following the release of this article, and data will be accessible for custom requests or possible inclusion in future editions of Juristat.

Crime rate

The traditional crime rate has been used to measure police-reported crime in Canada since 1962, and it is generally expressed as a rate per 100,000 population. The crime rate is calculated by summing all Criminal Code incidents reported by the police and dividing by the population count. The crime rate excludes Criminal Code traffic violations, as well as other federal statute violations such as drug offences.

To calculate the traditional police-reported crime rate, all offences are counted equally, regardless of their severity. For example, one incident of homicide is counted as equivalent to one incident of theft. As such, one limitation of the traditional crime rate is that it can easily fluctuate as a result of variations in higher volume but less serious offences, such as theft of $5,000 or under and mischief. In other words, a large decline in common but less serious violations may cause the police-reported crime rate to decrease even when the number of more serious but lower volume offences, such as homicide and robbery, increased.

In addition to the overall crime rate, rates are calculated for violent crime, property crime and other Criminal Code offences. Further, the rates of youth who have either been charged by police or dealt with through the use of extrajudicial measures are available for all crime categories.

Crime Severity Index

The CSI was developed to address the limitation of the police-reported crime rate being driven by high-volume, but relatively less serious, offences. The CSI not only takes into account the volume of crime, but also the relative severity of crime. As such, the CSI will vary when changes in either the volume of crime or the average severity of crime—or both the volume and the average severity—are recorded.

In order to calculate the police-reported CSI, each violation is assigned a weight. CSI weights are based on the violation’s incarceration rate, as well as the average length of prison sentence handed down by criminal courts.Note The more serious the average sentence, the higher the weight assigned to the offence, meaning that the more serious offences have a greater impact on the CSI. Unlike the traditional crime rate, all offences, including Criminal Code traffic violations and other federal statute violations such as drug offences, are included in the CSI.

To calculate the CSI, the weighted offences are summed and then divided by the population. Similar to other indexes (e.g., Consumer Price Index), to allow for ease of comparison, the CSI is then standardized to a base year of “100” (for the CSI, the base year is 2006). All CSI values are relative to the Canada-level CSI for 2006. CSI values are available back to 1998.

In addition to the overall CSI, both a Violent CSI (VCSI) and a Non-violent CSI (NVCSI) have been created, which—like the overall CSI—are available back to 1998. The VCSI is comprised of all police-reported violent violations, and the NVCSI is comprised of all police-reported property violations, other Criminal Code violations, Criminal Code traffic violations, and other federal statute violations. All types of CSI measures are also available for youth who have been accused of a crime (charged and not charged).

To adjust to changes in sentencing patterns from the courts, and amendments to the Criminal Code and other federal statutes, the weights are updated every five years. The most recent update was carried out in 2018 and applies to 2019 revised and 2020 data presented in this article.

For more information on the CSI, see Measuring Crime in Canada: Introducing the Crime Severity Index and Improvements to the Uniform Crime Reporting Survey (Wallace et al. 2009), The Methodology of the Police-reported Crime Severity Index (Babyak et al. 2009), Updating the Police-Reported Crime Severity Index Weights: Refinements to the Methodology (Babyak et al. 2013), Updating the Police-Reported Crime Severity Index: Calculating 2018 Weights (Cormack and Tabuchi 2020), and the Measuring Crime in Canada: A detailed look at the Crime Severity Index video (Statistics Canada 2016).

End of text box 6

Most provinces report decreases in Crime Severity Index

Between 2019 and 2020, 8 of Canada’s 10 provinces, and 1 territory (Nunavut) reported decreases in their CSI (Table 9). Nova Scotia (+8%) and New Brunswick (+3%) reported increases in their CSI. Approximately 40% of the increase in Nova Scotia was due to the mass shooting in Nova Scotia which ended in 22 lives lost and 3 people injured.Note As has been the case since 1998, the Prairie provinces and British Columbia have had the highest CSIs among the provinces, while the three Territories have reported the highest CSIs overall.Note Breaking and entering, theft and shoplifting of $5,000 or under, robbery, fraud and homicide offences were common contributing factors for increases or decreases in CSIs among the provinces and territories (Text box 7).

Start of text box 7

Text box 7

Violations contributing to the change in the Crime Severity Index (CSI) between

2019 and 2020, by province or territory

| Province or territory | Percent change in CSI from 2019 to 2020 | Violations driving the change in CSI |

|---|---|---|

| Canada | -8 | Decrease in breaking and entering, theft of $5,000 or under (non-shoplifting), robbery, shoplifting of $5,000 or under, as well as administration of justice violations and sexual assault (level 1). |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | -4 | Decrease in breaking and entering, as well as theft of $5,000 or under (non-shoplifting), shoplifting of $5,000 or under and robbery; partially offset by increase in mischief and trafficking, production, importation or exportation of cocaine. |

| Prince Edward Island | -11 | Decrease in breaking and entering and theft of $5,000 or under (non-shoplifting), as well as homicide and robbery; partially offset by increase in dangerous operation of a motor vehicle evading police (traffic violation) and fraud. |

| Nova ScotiaText box 7 Note 1 | 8 | Increase in homicide, fraud and child pornography; partially offset by decrease in breaking and entering and theft of $5,000 or under (non-shoplifting). |

| New Brunswick | 3 | Increase in fraud, identity theft, dangerous operation of a motor vehicle evading police (traffic violation), child pornography and trafficking, production, importation or exportation of methamphetamine; partially offset by decrease in breaking and entering, and theft of $5,000 or under (non-shoplifting). |

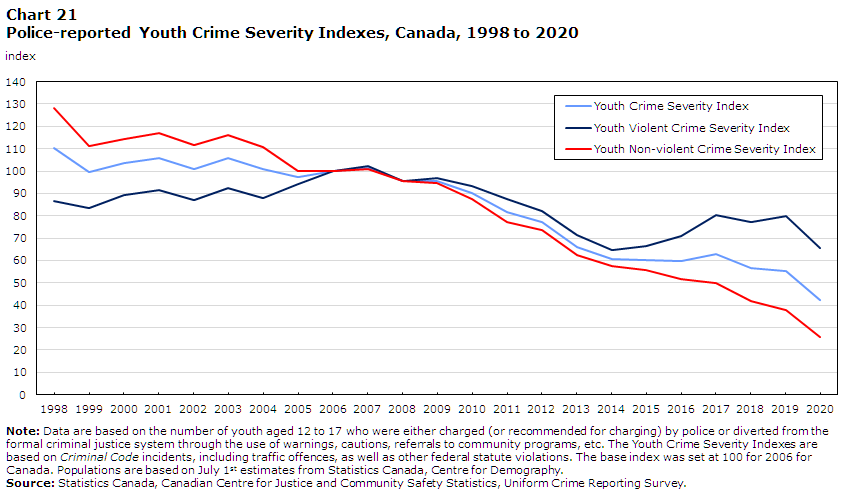

| Quebec | -7 | Decrease in breaking and entering, as well as importation or exportation under the Cannabis ActText box 7 Note 2 and robbery; partially offset by increase in fraud. |