Crimes related to the sex trade: Before and after legislative changes in Canada

by Mary Allen and Cristine Rotenberg, Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics

Highlights

- In December, 2014, the Protection of Communities and Exploited Persons Act (PCEPA) changed the laws related to the sex trade, shifting the focus of criminalization from those who sell their own sexual services onto those who purchase sexual services and those who benefit financially from others’ sexual services. This article examines changes in sex-trade-related crime reported by police before and after the change in legislation.

- Between 2010 and 2019, there was a 55% decline in sex-trade-related crime driven by a 95% decline in incidents of stopping or impeding traffic, or communicating for the purpose of offering, providing or obtaining sexual services. Most of this decline occurred prior to the adoption of the PCEPA in 2014.

- Fewer women were accused or charged in incidents of stopping or communicating offences after the introduction of the PCEPA. The number of men accused in incidents relating to stopping or communicating offences also dropped considerably between 2010 and 2014. Charging rates also declined for men accused in this type of incident, but not to the same extent.

- With the drop in charges for stopping or communicating offences, there was a large decline in the number of court cases involving these offences. Fewer women were tried in court for stopping or communicating offences in the five-year period after the new legislation than the five-year period preceding the change (-97%). In addition, far fewer women were found guilty, and, of those, none were sentenced to custody.

- The PCEPA placed a new focus on activities related to the purchasing of sexual services. Between 2015 and 2017, incidents of the new offence of obtaining sexual services from an adult increased sharply before declining for two consecutive years. Individuals accused in these incidents were mostly men.

- After the drop in the number of men accused in incidents of stopping or communicating offences prior to the PCEPA, the number of men accused increased once the new legislation was in place (obtaining sexual services from an adult). There was also an increase in men accused in incidents of obtaining sexual services from a minor. Most of the men accused of purchasing sexual services were charged. In the courts, over four in five men tried for obtaining services from a minor were found guilty, and this was the case for about one in seven cases of obtaining sexual services from an adult.

- The number of police-reported incidents related to profiting from the sexual services of others increased after the change in legislation, as procuring and receiving material benefit incidents reached a high point in 2019, almost double what was reported in 2010.

- Both before and after the change in legislation, men were more often accused in incidents related to procuring or receiving material benefit than women, even more so after the PCEPA (67% of accused were men prior to the PCEPA and 82% after). This shift was the result of the drop in women accused in these incidents, coupled with a substantial increase in the number of men accused. In the courts, among cases involving a charge related to profiting from sexual services, men were more likely than women to be convicted in the five-year period before and after the PCEPA. Most of those convicted in these cases were sentenced to custody. Though an infrequent offence in terms of the number of cases processed, advertising sexual services offences also saw high conviction rates.

- After the PCEPA, fewer sex-trade-related offences occurred on the street or in an open area and proportionally more took place in a home or a commercial dwelling unit such as a hotel. This was driven by a considerable decline in offences that are public by definition (i.e., stopping or impeding traffic or communicating offences). The increase in incidents occurring in a home or a commercial dwelling unit is mostly explained by the large increase in incidents of procuring or receiving material benefit as well as the creation of the new offence related to obtaining sexual services from an adult.

In December 2014, Canada introduced new legislation with the main objective to reduce the demand for sexual services in order to protect women and girls, who are disproportionately negatively impacted by the sex trade (Department of Justice Canada 2014). One objective of the new legislation is to shift the criminal burden from those who sell their own sexual services onto those who create the demand and those who financially benefit from the sale of others’ sexual services (Department of Justice Canada 2014).

Other countries have taken a similar legislative approach that views the sex trade as negatively impacting women and girls, and the practice of capitalizing on the demand for sexual services posing too high a risk of exploitation. Referred to as the “Nordic Model”, this approach targets purchasers of sexual services and third parties who develop economic interests in others’ sexual services, while providers of their own sexual services are not criminalized; rather, they are viewed as needing “support and assistance, not blame and punishment” (Department of Justice Canada 2014). The Nordic Model originated in Sweden in 1999 and more recently, in the past decade, versions of it have been incorporated into law in Norway, Iceland, Northern Ireland, France and Israel.

Former Bill C-36, the Protection of Communities and Exploited Persons Act (PCEPA), which came into force on December 6, 2014, responded to the Supreme Court of Canada’s 2013 Bedford decision which found that three now repealed Criminal Code “prostitution” offences violated life, liberty and security of the person rights under the Charter on the basis that they prevented those that work in the sex trade from taking steps to protect themselves when engaged in risky, but legal activity (Canada (Attorney General) v. Bedford 2013). Most pre-existing Criminal Code offences related to the sex trade were subsequently repealed and new related offences were created (see Text box 1).

Under the PCEPA, changes were made to the Criminal Code specifically aimed at targeting the purchasers of sexual services in addition to third parties who profit off the sale of others’ sexual services. New laws made it illegal to purchase sexual services from an adult, communicate in any place for that purpose, or to advertise sexual services. An immunity provision was also introduced, which ensured that individuals selling their own sexual services cannot be held criminally liable for their role in purchasing and third party offences. As a result of these reforms, for the first time in Canada, purchasing sexual services from adults and advertising others’ sexual services became criminal offences. For some offences, the maximum penalties for sex-trade-related crimes were increased. Purchasing and third party offences (e.g., receiving material benefit from others’ sexual services and procuring others to provide sexual services) are now classified as “crimes against the person” and thus considered violent offences.Note

Previous research has found that, prior to the implementation of the PCEPA, police-reported rates of sex trade-related offences had been decreasing for many years, driven by a large decline in the offence of stopping or impeding traffic, or communicating for the purpose of purchasing or selling sexual services.Note In the five years preceding the new law, while the Bedford case proceeded through the courts, police-reported incidents of sex-trade-related crimes declined considerably. Women and men were accused in sex-trade-related offences at nearly equal proportions during this period: under the previous legislation, the law did not differentiate between offences committed by persons accused of providing and persons accused of purchasing sexual services. However, women, who are largely the providers of sexual services were more often the accused in sex-trade-related incidents during this period than in other types of crime, and they were more likely than men to have repeated contacts with police or be found guilty of sex-trade-related crimes (Rotenberg 2016).

This Juristat article uses data from the Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR) Survey and the Integrated Criminal Court Survey (ICCS) to examine crimes related to the sex trade before and after the PCEPA legislative changes came into force in December of 2014. Offences that target the purchasers of sexual services and third-party offences (such as procuring or receiving material benefit) are isolated throughout this article in order to align the findings with the distinct parties targeted in these laws. An examination of changes in the nature of police-reported incidents of sex-trade-related offences is also presented, along with characteristics of persons accused in these crimes, victim characteristics and court case outcomes. Findings related to the different types of offences are presented using two five-year periods of pooled data, before and after the change in legislation. This provides a pre- and post-PCEPA analysis and groups data to better control for year-over-year variations due to low counts. Figures are provided by year where relevant and meaningful.

This study was commissioned and funded by the Department of Justice Canada.

Trends in crimes related to the sex trade

Long term decline in police-reported crimes related to the sex trade largely occurred prior to new legislation, driven by decrease in stopping or communicating offences

Prior to the enactment of the PCEPA in 2014, rates of police-reported crime related to the sex trade in Canada had been in steady decline since the 1985 implementation of the law prohibiting communicating in public places for the purposes of purchasing or selling sexual services (Rotenberg 2016). Between 2010 and 2019, the years examined in this study, the number of police-reported crimes related to the sex trade decreased by 55%.Note

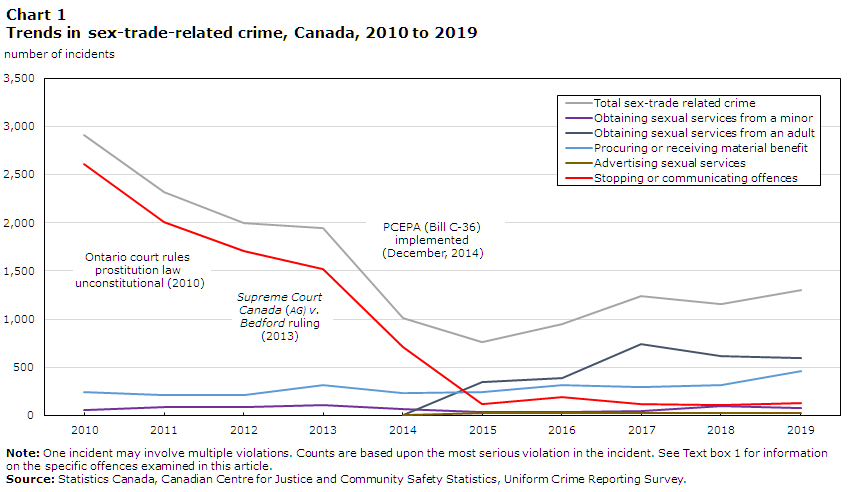

This decline was driven by a substantial (-95%) decrease in the number of incidents of stopping or communicating offences (Criminal Code of Canada s. 213). In 2010, police reported over 2,600 incidents of these offences which then dropped to 134 incidents in 2019 (Table 1). Much of this decrease occurred in the years leading up to the enactment of the PCEPA (Chart 1). In addition, one of the offences under section 213 (communicating for the purpose of providing or obtaining sexual services) was repealed by the PCEPA, and a new, narrower offence prohibiting communicating for the purposes of selling sexual services near school grounds, playgrounds and day care centres was added to section 213 (see Text box 1).

Chart 1 start

Data table for Chart 1

| 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| number of incidents | ||||||||||

| Total sex-trade related crime | 2,904 | 2,315 | 1,999 | 1,941 | 1,014 | 765 | 952 | 1,240 | 1,159 | 1,298 |

| Obtaining sexual services from a minor | 56 | 89 | 83 | 103 | 68 | 32 | 33 | 49 | 94 | 76 |

| Obtaining sexual services from an adult | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | 4 | 343 | 388 | 743 | 613 | 593 |

| Procuring or receiving material benefit | 240 | 217 | 210 | 320 | 228 | 247 | 315 | 299 | 312 | 465 |

| Advertising sexual services | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | 1 | 21 | 29 | 29 | 29 | 30 |

| Stopping or communicating offences | 2,608 | 2,009 | 1,706 | 1,518 | 713 | 122 | 187 | 120 | 111 | 134 |

|

... not applicable Note: One incident may involve multiple violations. Counts are based upon the most serious violation in the incident. See Text box 1 for information on the specific offences examined in this article. Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics, Uniform Crime Reporting Survey. |

||||||||||

Chart 1 end

In addition, a new offence was enacted by the PCEPA directed specifically at criminalizing the purchasing of sexual services from an adult, and communicating in any place for that purpose (s. 286.1(1)). Between 2015 and 2017, incidents of the new purchasing offence increased sharply before declining for two consecutive years, reaching 593 incidents in 2019. The number of incidents related to obtaining sexual services from a minor varied from year to year between 2010 and 2019, with 75 incidents reported in 2019.

Notably, when looking at changes in the number of crimes involving third parties who profit from the sexual services of others, police-reported incidents of procuring or receiving material benefit from sexual services almost doubled from 240 incidents in 2010 to 465 in 2019.Note Note In addition, the number of incidents of the new offence related to advertising sexual services (s. 286.4), increased from 21 incidents in 2015 to 30 incidents reported in 2019.

Like other crimes, the number of police-reported sex-trade-related crimes may vary from year to year for various reasons (see Text box 2).

Start of text box 1

Text box 1

Definitions and concepts

This text box outlines the specific sex-trade-related offences examined in this study, and how these offences changed with the introduction of the Protection of Communities and Exploited Persons Act (PCEPA). For the information on police-reported incidents from the Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR) Survey, data is reported using specific UCR violation definitions which are not always directly comparable with specific Criminal Code sections.Note This analysis focuses primarily on incidents where the most serious violation reported by police in the incident was related to the sex trade.Note The article also provides a discussion of the nature of incidents where a sex-trade-related offence was not the most serious violation in the incident. Victim analysis is based on the most serious violation against the victim, which may or may not be the most serious violation in the incident.

Information from the Integrated Criminal Court Survey (ICCS) is reported by Criminal Code section and is based on cases where the most serious offence in the case was a sex-trade-related offence.Note Detailed information required to distinguish specific types of offence defined in subsections or paragraphs is not always available.

Violations related to the purchasing of sexual services

Obtaining sexual services from a minor: Prior to the PCEPA, subsection 212(4) prohibited obtaining sexual services for consideration from a person under the age of 18, or communicating with anyone for that purpose, and carried a maximum penalty of five years imprisonment.Note The PCEPA re-enacted this offence as subsection 286.1(2) which now recognizes it as a violent offence. Subsection 286.1(2) prohibits exactly the same conduct as did subsection 212(4). However, it carries a maximum penalty of 10 years, as well as mandatory minimum penalties.

Obtaining sexual services from an adult: Subsection 286.1(1) made it illegal, for the first time, to purchase sexual services from an adult by prohibiting obtaining sexual services for consideration from anyone, or communicating in any place for that purpose. It carries a maximum penalty of five years on indictment and mandatory minimum fines. It is also punishable on summary conviction with a maximum penalty that was increased from 18 months to two years less a day in 2019. Mandatory minimum fines apply.

Violations related to profiting from the sale of sexual services

Offences related to procuring or living on the avails/receiving material benefit: Procuring involves causing or inducing someone else to provide sexual services for consideration. The PCEPA repealed the section of the Criminal Code related to procuring or living on the avails of prostitution (s. 212) and enacted two new offences: sections 286.2 and 286.3. Section 286.3 prohibits procuring a person to offer or provide sexual services. Subsection 286.3(1) applies where the victim is an adult and carries a maximum penalty of 14 years. Subsection 286.3(2) applies where the victim is under the age of 18 and carries a maximum penalty of 14 years and mandatory minimum penalties. The maximum penalty for procuring increased from 10 to 14 years where the victim is an adult. Section 286.2 prohibits receiving a financial or other material benefit from others’ sexual services. Subsection 286.2(1) applies where the victim is an adult and carries a maximum penalty of 10 years on indictment. Subsection 286.2(2) applies where the victim is under the age of 18 and carries a maximum penalty of 14 years, as well as mandatory minimum penalties. This offence does not apply where the benefit received is in the context of a legitimate family or business relationship (e.g., family members or landlords), or in the context of independent or cooperative working arrangements.

Prior to the PCEPA, the UCR had a single violation category for procuring, and separate categories for living on the avails of the prostitution of a person under the age of 18 (s. 212(2)) and obtaining sexual services from a minor (s. 212(4)). In addition, prior to the PCEPA, the UCR violation category for procuring also included section 170 (parent or guardian procuring sexual activity of a person under the age of 18) and section 171 (householder permitting unlawful sexual activity of a person under the age of 18).Note

With the change in legislation, the UCR now makes additional distinctions. For procuring activities, it distinguishes between procuring an adult and procuring a minor (ss. 286.3(1) and 286.3(2)) and between receiving material benefit where the victim was an adult or a minor (ss. 286.2(1) and 286.2(2)).Note

Because of differences in the offences included in the UCR violation categories resulting from the PCEPA changes, these violations (procuring, living on the avails and receiving material benefit) are analysed as a single category in this analysis to support the comparison of police-reported information before and after the PCEPA.

Advertising sexual services: The PCEPA created a new offence (s. 286.4), which prohibits advertising others’ sexual services. It carries a maximum penalty of five years on indictment and two years less a day on summary conviction.

It is important to note that for offences related to purchasing (s. 286.1), receiving material benefit (s. 286.2), procuring (s. 286.3) or advertising (s. 286.4), an immunity provision ensures that individuals who sell their own sexual services cannot be held criminally liable for any role they play in these offences (s. 286.5).

Stopping or communicating offences

Paragraphs 213(1)(a) and (b), which are summary conviction offences, prohibit stopping or attempting to stop a motor vehicle in a public place, or impeding the free flow of pedestrian or vehicular traffic in a public place, for the purposes of either purchasing or selling sexual services. These offences remain in force as they existed prior to PCEPA. Paragraph 213(1)(c), which was also a summary conviction offence, prohibited communicating in a public place for the purposes of either purchasing or selling sexual services. Paragraph 213(1)(c) was struck down by the Supreme Court of Canada’s 2013 Canada (Attorney General) v. Bedford decision and repealed by the PCEPA.

The PCEPA enacted a new summary conviction offence prohibiting communicating “for the purpose of offering or providing sexual services for consideration—in a public place, or in any place open to public view, that is or is next to a school ground, playground or daycare centre” (subsection 213(1.1)). This offence excludes the activities of the potential purchaser which are covered by section 286.1.

It should be noted that section 213 is the only provision that contains offences targeting activities related to the sale of sexual services.

Previous sex-trade-related offences not included in this analysis

Bawdy house offences (s. 210 and 211): These offences prohibited certain activities in relation to places that are kept or occupied for the purposes of prostitution or for the practice of acts of indecency. In its 2013 Bedford decision, the Supreme Court of Canada struck down these provisions where they applied to places kept for the purposes of prostitution. The PCEPA repealed the bawdy house provisions’ reference to “prostitution” and, in 2019, former Bill C-75 repealed all the bawdy house provisions.

End of text box 1

Rates of police-reported crime related to the sex trade vary by region

Trends in police-reported crimes related to the sex trade vary across the provinces and territories as well as the largest cities in Canada (census metropolitan areas) (Table 2; Table 3). This was the case both before and after the enactment of the PCEPA.

A comparison of the average rates reported in the five-year periods before and after the PCEPA shows that the provinces with the largest declines were British Columbia (-72%), Ontario (-66%) and Newfoundland and Labrador (-63%). At the national level, the five-year average rate of these incidents (2010 to 2014 versus 2015 to 2019) fell 50%.Note

It is important to note that differences in the reporting of incidents involving sex-trade-related violations among police services can be influenced by differences in enforcement and reporting practices in different jurisdictions (see Text box 2). In addition, differences in the trends in these violations before and after the enactment of the PCEPA may reflect how and when police services adapted their enforcement practices to the new legislation.

Start of text box 2

Text box 2

Impact of police enforcement and reporting practices on trends

in incidents of sex-trade-related violations

As with many violations reported to the Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR) Survey, there are many factors that influence variations between jurisdictions or over time. These may include differences in socioeconomic conditions, as well as police resources, priorities and enforcement. Fluctuations in counts between years or across police services are common and may reflect changes in police enforcement of laws related to the sex-trade as opposed to the actual prevalence of sex trade activity in a given year or community. Clusters of arrests may be made when police services undertake sting operations. The statistics presented in this article are based solely on incidents that come to the attention of and are reported by police.

Change in police reporting of unfounded incidents

In addition to changes in the legislation and subsequent changes in police intervention in their communities, changes in the way these incidents were reported by police services have also had an impact on the rates of sex-trade-related crime in this article.

On January 1, 2018, Statistics Canada, in collaboration with police, changed the definition of “founded” criminal incidents to include incidents where there is no credible evidence to confirm that the reported incident did not take place. With the new definition, there is the potential that police will classify more incidents as founded. In turn, the UCR introduced new ways of reporting founded incidents that were not cleared (or solved) to allow for more specificity in reasons for not clearing an incident that came to the attention of police. Among the new categories added to the UCR is the category “insufficient evidence to proceed”. Previously, these incidents may have been classified as unfounded by police, and therefore excluded from the count of incidents.

While the effective date of the new reporting standards for founded incidents was January 2018, police services transitioned to the new standards at different points throughout the year. Some police services, including all of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) detachments across Canada and municipal police services in British Columbia, transitioned to the new standards on January 1, 2019.

In some jurisdictions, the new reporting standards had a notable impact on the number of sex-trade-related incidents reported. As such, there was a significant increase in the number of sex-trade-related incidents scored as “insufficient evidence to proceed” between 2018 and 2019, particularly those reported by the Codiac Regional RCMP detachment (police of jurisdiction—Moncton, Dieppe and Riverview) in the Moncton census metropolitan area (CMA). Any indication of a suspicious transaction in an area frequented by sex trade workers (i.e. known sex trade workers having a conversation with someone in a vehicle) was reported and scored as “insufficient evidence to proceed”. The increase in sex-trade-related crime reported in the Moncton CMA accounted for 42% of the national increase between 2018 and 2019 (Table 3).

For more information on changes in police reporting of unfounded criminal incidents, see Canadian Centre for Justice Statistics 2018.

End of text box 2

Police-reported incidents involving a sex-trade-related violation

About one in six sex-trade-related incidents reported by police involved a more serious offence

In the five years prior to the PCEPA, between 2010 and 2014, police reported 12,155 criminal incidents involving at least one violation related to the sex-trade. In contrast, about half that number were reported in the five-year period following the change in legislation (6,431 between 2015 and 2019). In both time frames, the sex-trade-related offence was the most serious violation in the incident in 83% of incidents. The most serious violation in an incident is determined by police, based on a number of classification rules used uniformly across the country, including the type of offence and the maximum penalty under the Criminal Code.

The remaining incidents involved situations where the sex-trade-related offence was not the most serious violation in the incident, but rather a secondary violation.Note These differed before and after the change in legislation due to the fact that the new laws changed the relative seriousness of some offences.Note In 1 in 10 (10%) incidents, the most serious violation reported for these incidents between 2010 and 2014 was a non-violent offence such as mischief, breach of probation or failure to comply with conditions.Note This was the case for less than 1% of incidents between 2015 and 2019 after many of the sex-trade related offences were now classified as offences against the person (violent offences in the UCR).

Both before and after the PCEPA, some incidents where sex-trade-related offences were a secondary violation had a sexual offence as the most serious violation.Note This was the case in 3% (377 incidents) of incidents involving a sex-trade-related offence prior to the PCEPA and 7% (420 incidents) in the period after it was enacted. Notably, between 2015 and 2019, in incidents where the sex-trade-related offence was a secondary violation, the most serious violation in the incident was most frequently human trafficking. It was the most serious violation in 1% of incidents (137 incidents) involving a sex-trade-related violation prior to the PCEPA, and 7% after (429 incidents) (see Text box 3).

Start of text box 3

Text box 3

Human trafficking

For some, the sex trade can be a gateway into human trafficking (Barrett 2013; Cho et al. 2012), which is a serious crime involving the exploitation of persons usually for profit, including in the sex trade. In this context, victims are often young women. As defined by the Criminal Code, trafficking in persons occurs when someone recruits, transports, transfers, receives, holds, conceals or harbours a person, or exercises control, direction or influence over the movements of a person for the purpose of exploiting them or facilitating their exploitation by someone else, typically through forced labour or in the sex trade. In addition, section 118 of the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act makes cross-border trafficking an offence punishable by law. As such, many human trafficking incidents may also involve sex-trade-related crime.

Although human trafficking crimes reported to the Uniform Crime Reporting Survey cannot be analyzed by type of trafficking (e.g., sex trafficking, forced labour, debt bondage or organ removals), it is estimated that half of human trafficking globally is sex trafficking (UNODC 2020), whereby victims are sexually exploited and coerced into providing sexual services to financially benefit their trafficker. Sex trafficking in Canada disproportionately affects women and youth, as well as vulnerable populations including Indigenous women, immigrants, and those of low socioeconomic status (Public Safety Canada 2019).

The Protection of Communities and Exploited Persons Act (PCEPA) also amended the Criminal Code with respect to human trafficking, including by imposing mandatory minimum penalties for section 279.01 as well as all other human trafficking offences involving a child victim.

Rates of police-reported human trafficking in Canada have been increasing since 2010. In the five years prior to the PCEPA (2010 to 2014), there were 466 incidents where a human trafficking offence was reported in the incident.Note After PCEPA (2015 to 2019), this figure more than tripled, with 1,824 incidents reported over the five-year period. Whether before or after PCEPA, less than one-third of human-trafficking-related incidents also involved a sex-trade-related offence (31% pre-PCEPA; 25% post-PCEPA).Note More specifically, in the context of the overall increase in human trafficking incidents, the number of human-trafficking-related incidents where a sex-trade-related violation was also reported increased from 5 incidents in 2010 to 96 in 2019.Note Most of these incidents reported in 2019 (73) involved a procuring violation and 53 incidents involved receiving material benefit.

More information on human trafficking incidents reported in 2019 can be found in “Trafficking in persons in Canada, 2019” (Ibrahim 2021).

End of text box 3

Characteristics of individuals accused by police in sex-trade-related crimes

The PCEPA was introduced to reduce the demand for sexual services, on the basis that the sex trade disproportionately negatively impacts on women and girls. The new laws aimed to shift the burden of criminalization from those who sell their own sexual services to those who purchase those services or who profit from others’ sexual services (procuring or receiving material benefit or advertising sexual services) (Department of Justice Canada 2014). Previous analysis of the six years prior to the introduction of the PCEPA (2009 to 2014) found that 43% of accused in sex-trade-related offences were women; a much higher proportion than for police-reported crime generally (23%). Moreover, many women accused in sex-trade-related offences were more likely to have repeated contact with police than men (Rotenberg 2016). Research suggests that in Canada, the vast majority of people who pay for sexual services are men, and that up to 80% of those who provide sexual services are women (Benoit and Shumka 2015; Conseil du statut de la femme 2012; Department of Justice Canada 2014). This research also suggests that the individuals who provide sexual services are not exclusively women; rather, there is literature on men and transgender people who also work in the sex trade (Carter and Walton 2000).Note

It is important to note that up until the introduction of the PCEPA in 2014, the law governing stopping or communicating offences (s. 213) did not differentiate between offences committed by persons accused of activities related to providing sexual services and those purchasing them. Section 213 offences applied both to individuals who provide sexual services as well as those who purchase them, and both could be accused under these offences. As a result, analysis of police-reported crime data could not distinguish whether a person accused in a sex-trade-related incident was the individual providing the services or a purchaser of those services, only whether the accused identified as a man or a woman. After the PCEPA, this is still the case for two offences contained in section 213(1).

The information from the UCR identifies the most serious violation in the incident and can identify individuals accused in the incident and whether or not they were charged. However, sex-trade-related crime may involve more than one perpetrator and more than one violation. Information was not available for this analysis to identify the specific offence in an incident for which an individual was accused or charged. Before the PCEPA, 10% of individuals accused in a sex-trade-related crime were involved in an incident with more than one accused. This was the case for 13% of accused after the PCEPA.Note

A comparison of the characteristics of individuals accused in sex-trade-related offences shows a clear shift in the number of women and men accused in these incidents, resulting primarily from the decline in incidents of stopping or communicating offences (s. 213).Note At the same time, there was an increase in individuals (mostly men) accused in police-reported incidents of the new offence of obtaining sexual services from an adult as well as offences related to third parties who profit from the sale of others’ sexual services (procuring or receiving material benefit or advertising sexual services).

Very few women accused in sex-trade-related incidents since 2014

The number of women accused in sex-trade-related incidents dropped off considerably leading up to the enactment of new legislation in 2014, primarily as a result of changing police enforcement practices given the ongoing court challenge at the time (Chart 2) (Rotenberg 2016). This translated primarily into a large decline in women accused in incidents of stopping or communicating offences. Overall, the proportion of individuals accused in sex-trade-related incidents who were women dropped from 42% in 2010 to 22% in 2014 and 5% by 2019 after the PCEPA had been in effect for a few years.

Chart 2 start

Data table for Chart 2

| 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| number of accused | ||||||||||

| Women | 966 | 824 | 647 | 472 | 103 | 54 | 71 | 59 | 48 | 36 |

| Men | 1,361 | 969 | 865 | 944 | 376 | 450 | 586 | 874 | 793 | 664 |

|

Note: Includes accused aged 12 years and older. Children under the age of 12 cannot be charged with a criminal offence. See Text box 1 for information on the specific offences examined in this article. Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics, Incident-based Uniform Crime Reporting SurveyTrend file. |

||||||||||

Chart 2 end

After the introduction of the PCEPA, the number of women accused in sex-trade-related incidents remained low, particularly for stopping or communicating offences (s. 213). The number of women accused under section 213 fell from 888 in 2010 to the point where they were very few, with just five women accused in Canada in 2019.

As a result of the large decline in stopping or communicating offences, a higher proportion of women accused in sex-trade-related crime were accused in incidents of the more serious offences of procuring or receiving material benefit from sexual services. That being said, the number of women accused in these offences fell from 237 in the five years prior to the PCEPA (2010 to 2014) to 148 women accused in the five years following the new legislation (2015 to 2019) (Table 4). These were offences which were more likely to involve younger women accused both before and after the change in legislation. While the number of women under the age of 25 accused in incidents of these offences increased after the introduction of the PCEPA (from 89 to 101 accused), the number of women aged 25 years and older accused in these incidents declined from 148 prior to the change in legislation to 46 afterwards.Note In 2019, 29 women were accused in incidents of procuring or receiving material benefit in Canada, 17 of whom were under the age of 25.

Very few women were accused in incidents specific to purchasing sexual services after the introduction of the PCEPA. Between 2015 and 2019, 23 women were accused in these incidents.

After the change in legislation, 93% of individuals accused in sex-trade-related incidents were men

The number of men accused by police (whether charged or not) in incidents of stopping or communicating offences also dropped considerably between 2010 and 2014. However, after introduction of the PCEPA, the number of men accused in sex-trade related crimes increased as a result of the new offence of obtaining sexual services from an adult. After the change in legislation, 93% of individuals accused in sex-trade-related incidents were men.

Prior to the PCEPA, between 2010 and 2014, 3,911 men were accused in incidents of stopping or communicating offences. With the change in legislation, this number was dramatically lower, with 211 men accused in stopping or communicating incidents between 2015 and 2019. Instead, 2,304 men were accused in incidents of the new offence of obtaining sexual services from an adult. At the same time, there was an increase in men accused in incidents of obtaining sexual services from a minor (from 131 accused prior to the PCEPA to 185 after).

In both periods, men were more often accused in incidents related to procuring or receiving material benefit than women, even more so after the PCEPA (67% of accused prior to the PCEPA and 82% after). This was the result of the drop in women accused in these incidents, and also a substantial increase in the number of men accused, from 472 in the five-year period prior to the PCEPA to 652 after. The increase was the result of more accused under the age of 25, and many under age 18. Overall, few men accused in sex-trade-related incidents were under the age of 18, but their numbers increased after the PCEPA. Between 2015 and 2019, 62 young men under the age of 18 were accused in a sex-trade-related incident, more than double the number (24) in the five-year period prior to the PCEPA. The majority of these teenage boys accused after the PCEPA (35 out of 62) were accused in incidents of procuring or receiving material benefit from sexual services.

Accused individuals charged in sex-trade-related incidents

Notably fewer charged in incidents of stopping or communicating offences in more recent years

For the most part, a large proportion of individuals accused in sex-trade-related incidents were charged, both before and after the change in legislation. The notable exception was for women accused in incidents of stopping or communicating offences (s. 213), among whom charge rates were lower after the change in legislation.Note Charging rates (the proportion of accused who were criminally charged) were also lower for men accused in this type of incident, but not to the same extent (Table 4) (Chart 3).

Chart 3 start

Data table for Chart 3

| Selected offences | 2010 to 2014 | 2015 to 2019 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| percent charged | |||

| Women | Procuring or receiving material benefit | 73 | 72 |

| Stopping or communicating offences | 88 | 41 | |

| Men | Procuring or receiving material benefit | 67 | 75 |

| Stopping or communicating offences | 86 | 63 | |

| Obtaining sexual services for consideration from an adult | Note ...: not applicable | 92 | |

|

... not applicable Note: These data are based on the most serious violation in the incident which may not reflect the actual charge for all accused in incidents where there was more than one accused. Includes accused aged 12 years and older. Children under the age of 12 cannot be charged with a criminal offence. The charge rate for women accused of obtaining sexual services for consideration from an adult is not presented due to low counts. A description of the offences can be found in Text box 1. Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics, Incident-based Uniform Crime Reporting Survey Trend file. |

|||

Chart 3 end

Not only did the number of women accused in incidents of stopping or communicating offences fall considerably between 2010 and 2019, but women accused in these incidents were much less likely to be charged after the PCEPA. Between 2010 and 2014, 2,701 women were accused in incidents of these offences under section 213 and 2,364 (88%) were charged. Meanwhile, in the five-year period following the new law, 83 women were accused and 34 (41%) were charged. (Table 4).

After the change in legislation, 63% of men accused in incidents of stopping or communicating offences were charged (compared to 86% prior to the PCEPA). However, for men accused in incidents of the new offence of obtaining sexual services from an adult between 2015 and 2019, over 9 in 10 (92%) were charged.Note

In contrast to the less serious offences where there was a clear change in the charging of women accused, there was little change in charging rates where the offences were more serious. For men and women accused in incidents of procuring or receiving material benefit from sexual services, over two-thirds were charged both before and after the PCEPA. Before the PCEPA, 73% of women and 67% of men accused in incidents of procuring or receiving material benefit were charged. After the PCEPA, 72% of women and 75% of men accused in incidents of these offences were charged.

Characteristics of victims of sex-trade-related crimes

With the introduction of the PCEPA, most of the new offences (ss. 286.1 to 286.4) are considered violent crimes under the Criminal Code.Note As a result, police may now report information on the characteristics of victims identified in the incident to the UCR.Note In addition, any incident involving a violation categorized as non-violent (including all sex-trade-related offences prior to 2015) may include information on victim characteristics if the most serious violation was a violent offence, such as a sexual offence or human trafficking. However, police are not required to submit information on victims to the UCR for some types of violent offences (including the new sex-trade-related offences), and no victim information is collected for non-violent offences.Note Where a victim record is provided, information is reported on the most serious violation against the victim.

It is important to note that the UCR only has information on incidents reported to police. According to self-reported data from the 2018 Survey of Safety in Public and Private Spaces, the vast majority of violent crime occurring in the 12 months preceding the survey did not come to the attention of police: a small minority (5%) of women who had been sexually assaulted stated that police found out about the most serious incident that they experienced, while 26% of women and 33% of men who were physically assaulted said likewise (Cotter and Savage 2019). Moreover, the lack of willingness of individuals involved in the sex trade to report to police is an important concern as it may exacerbate their vulnerability. They may be concerned that they will not be taken seriously by police, or that they may themselves be arrested. In a recent study of 200 sex trade workers in five Canadian cities, 31% reported “being unable to call 911 if they or another sex trade worker were in a safety emergency due to fear of police detection of themselves, their colleagues or management” (Crago et al. 2021). For these reasons, it is important to underscore that the data presented in this article are limited to crimes reported to and by police, which are likely an underestimation of the extent of victims of sex-trade-related offences in Canada.

This section examines the characteristics of victims in the periods before and after the enactment of the PCEPA where any of the violations reported in the incident was a sex-trade-related offence. This allows for a comparison of victims in these types of offences both before and after the enactment of the PCEPA. See the section “Police-reported incidents involving a sex-trade-related violation” for information on incidents where the most serious violation was not related to the sex trade.

In the five years before the PCEPA, there were 937 victims reported by police where any violation in the incident involved a sex-trade-related offence. Among these victims, 160 (17%) were victims of human trafficking, 439 (47%) were victims of a sexual offence (sexual assault or a sexual violation against a child)Note and another 167 (18%) were victims of assault.Note These were the offences identified as the most serious violation against the victim, not necessarily the most serious violation in the incident.

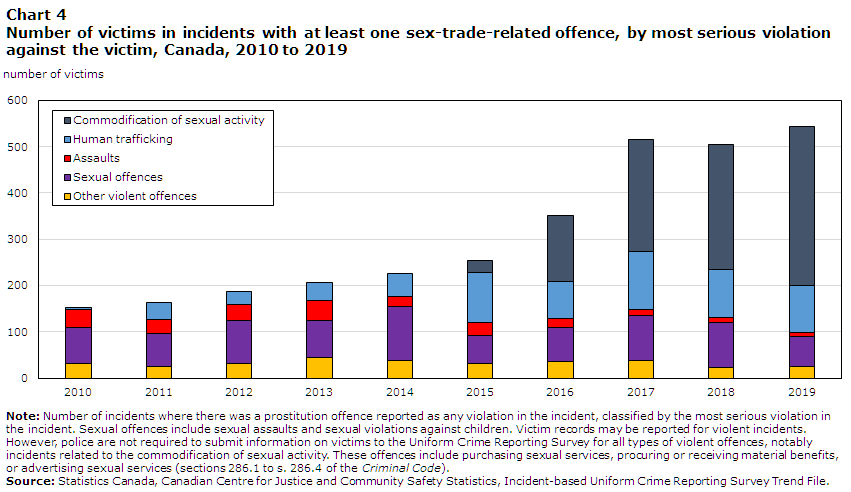

After 2014, the number of victims in any incident involving a sex-trade-related offence increased primarily as a result of the fact that victim records could now be reported to the UCR for the new offences; however, a notable increase in victims of human trafficking where a sex-trade-related offence was a secondary violation was also a key driver (Chart 4).Note

Chart 4 start

Data table for Chart 4

| Commodification of sexual activity | Human trafficking | Assaults | Sexual offences | Other violent offences | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| number of victims | |||||

| 2010 | Note ...: not applicable | 5 | 39 | 78 | 31 |

| 2011 | Note ...: not applicable | 36 | 30 | 71 | 26 |

| 2012 | Note ...: not applicable | 29 | 33 | 93 | 32 |

| 2013 | Note ...: not applicable | 40 | 42 | 81 | 44 |

| 2014 | Note ...: not applicable | 50 | 23 | 116 | 38 |

| 2015 | 26 | 109 | 27 | 61 | 32 |

| 2016 | 143 | 81 | 18 | 75 | 35 |

| 2017 | 242 | 125 | 13 | 98 | 37 |

| 2018 | 269 | 104 | 12 | 96 | 23 |

| 2019 | 344 | 101 | 9 | 66 | 24 |

|

... not applicable Note: Number of incidents where there was a prostitution offence reported as any violation in the incident, classified by the most serious violation in the incident. Sexual offences include sexual assaults and sexual violations against children. Victim records may be reported for violent incidents. However, police are not required to submit information on victims to the Uniform Crime Reporting Survey for all types of violent offences, notably incidents related to the commodification of sexual activity. These offences include purchasing sexual services, procuring or receiving material benefits, or advertising sexual services (sections 286.1 to s. 286.4 of the Criminal Code). Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics, Incident-based Uniform Crime Reporting Survey Trend File. |

|||||

Chart 4 end

Between 2015 and 2019, there were a total of 2,170 victims in incidents where there was at least one sex-trade-related offence recorded as part of the incident. Of these victims, almost half (1,024 or 47%) were reported as victims of one of the newly enacted (s. 286) sex-trade-related offences, most frequently procuring (735 or 34%)) or obtaining sexual services for consideration (202 or 9%)).Note Another 520 (24%) were identified as a victim of human trafficking and 396 (18%) were victims of a sexual offence.Note

Both before and after the new legislation, the vast majority of victims were women

For the most part, the characteristics of victims in incidents where a sex-trade-related offence was reported were very similar before and after the change in legislation. The vast majority of victims were women. However, this was the case for an even greater proportion after 2015 (94% compared to 87% previously). This was driven in part by the shift to the new sex-trade-related offences for which victim records could now be reported. These were primarily women victims of offences related to procuring or receiving material benefit. The increase is also partly attributable to the increasing number of human trafficking victims. These types of offences involved women as victims almost exclusively (95% of victims of sex-trade-related offences; 99% of sex-trade-related human trafficking victims in both periods).Note

Four in ten victims were youth aged 12 to 17 in both time periods

Youth (aged 12 to 17 years) accounted for more than 4 in 10 victims in violent crimes involving at least one sex-trade-related offence both before and after the new legislation (44% before and 43% after the PCEPA). Few victims were children under age 12, even fewer after the new law (4% before the PCEPA and less than 1% after).Note The median age of women victims was 18 in both time periods. Victims who were men were older after the change in legislation (median age 17 before and 20 after the PCEPA).

Victims less likely to report injuries after new legislation

Victims in incidents involving at least one sex-trade-related offence were less likely to have a physical injury as a result of the incident in the five-year period after the introduction of the PCEPA (17% compared to 29% in the five years preceding the PCEPA).Note Most of these injuries were minor. Injuries were most common when the most serious violation against the victim was assault, sexual assault or human trafficking. For victims of the newly classified sex-trade-related offences, 1 in 10 (10%) was injured. This was driven by rates of injury for adult victims of procuring (20%).

The decline in reported injuries occurred for both youth (aged 12 to 17) and adult victims. However, in both time periods, youth victims were less likely than adult victims to have an injury reported. Further, women victims were more likely than men to have an injury in both time periods. Before the PCEPA, 30% of women victims in a sex-trade-related incident reported an injury compared to 17% in the five years afterwards. For victims who were men, the proportion reporting an injury dropped from 19% in the five years prior to the PCEPA to 10% afterwards.

Fewer homicides of sex trade workers after change in legislation

The Homicide Survey collects data on homicides in Canada and includes information related to a victim’s occupation.Note According to the Homicide Survey, 35 victims of homicide were identified as sex trade workers between 2015 and 2019, which was notably fewer than the 54 homicide victims reported as sex trade workers between 2010 and 2014. This was especially notable given that, between these two time periods, the number of homicides in Canada overall increased from 2,745 to 3,229. In both time frames, almost all victims of homicide identified as sex trade workers were women (53 of the 54 victims prior to the PCEPA, 33 of the 35 victims after).

For sex trade worker homicides where a suspect had been identified, in the five years prior to the change in the law, the perpetrator was most frequently identified as being in a criminal relationship with the victim (e.g., sex trade workers and their clients, drug dealers and their clients, gang members) (43% of victims). This was less common after the PCEPA (29%); instead, between 2015 and 2019, 38% of sex trade worker victims were killed by a casual acquaintance or a stranger.

Between 2010 and 2014, 20 of the 54 sex trade worker homicide victims were identified as Indigenous. In the five-year period following the PCEPA, 7 of the 35 victims were identified as Indigenous.

Characteristics of police-reported sex-trade-related incidents

More police-reported sex-trade-related offences occurring in residential or private commercial spaces after PCEPA

With the change in legislation, which aimed to shift the criminalization focus away from individuals providing sexual services, the nature of police-reported sex-trade-related incidents also changed. Overall, after the introduction of the PCEPA, fewer incidents occurred on the street or in an open area and proportionally more occurred in a house, other dwelling unit or commercial dwelling unit, such as a hotel. Between 2010 and 2014, about three-quarters (78%) of police-reported sex-trade-related offences occurred on the street or in an open area (7,748 incidents), while one in nine (11% or 1,125 incidents) took place in a house, other dwelling unit or commercial dwelling unit.Note In comparison, in the five-year period after the change in law, nearly half (48% or 2,529 incidents) occurred on the street or in an open area. Over one-third (35% or 1,811 incidents) took place in a house, other dwelling unit or commercial dwelling unit, more than prior to the PCEPA despite the overall decline in incidents.

The decline in reported incidents occurring in the street or open areas was largely tied to the decrease in stopping or communicating offences (s. 213), which only applied to activities occurring in a public place or a place open to public view.Note In contrast, the PCEPA created new offences such as obtaining sexual services from an adult, which applied in any location. It is also worth noting that use of the internet for communicating may also impact the reported location of these activities.

Notably, the increase in incidents occurring in a house, other dwelling unit or commercial dwelling unit is partly explained by the increase in procuring or receiving material benefit offences. The proportion of these incidents that occurred in a home or commercial dwelling unit increased from 44% (486 incidents) prior to the PCEPA to 54% (818 incidents) after. Between 2015 and 2019, incidents of procuring or receiving material benefit accounted for almost half (45%) of sex-trade-related incidents occurring in a house, other dwelling unit or commercial dwelling unit.

Between 2015 and 2019, 64% (1,701 incidents) of incidents of obtaining sexual services from an adult occurred on the street or in an open area, while 25% (665 incidents) occurred in a house, other dwelling unit or commercial dwelling unit.

Of note, there was also a shift in location of the less frequent offence of obtaining sexual services from a minor. Prior to the introduction of the PCEPA, half (50% or 192 incidents) occurred on the street or in an open area, compared with one in five (20% or 52 incidents) in the five years following the change in legislation. Instead, this offence was much more likely to occur in a house, other dwelling unit or commercial dwelling unit after the change in legislation (61% or 160 incidents compared to 31% or 118 incidents prior to the PCEPA).

Sex-trade-related offences in the courts

During the five-year period prior to the enactment of the PCEPA, between 2009/2010 and 2013/2014,Note there were 5,561 criminal cases completed in adult and youth court where a sex-trade-related offence was the most serious offence (Table 5).Note As with police-reported offences, the introduction of the PCEPA in 2014 coincided with a decline in sex-trade-related cases in criminal court.Note Between the five-year period before and after the change in legislation, the number of sex-trade-related cases completed in court declined by 62% (to 2,096 cases between 2014/2015 and 2018/2019).

Given the declines noted among certain sex-trade-related crimes reported and charged by police, the courts consequently saw much of their overall decline in cases driven by a reduction in stopping or communicating (s. 213) cases. These cases combined decreased by 95% between the five-year period prior to and after the PCEPA (from 4,960 cases between 2009/2010 and 2013/2014 to 254 cases completed between 2014/2015 and 2018/2019). As with police-reported incidents, this decline had already begun in the years leading up to the enactment of the PCEPA.

Three in five court cases after PCEPA for offences related to purchasing sexual services

Despite the overall decline, as of 2014/2015, there were newly introduced PCEPA crimes moving through the court system. Purchasing-related offences, which include obtaining sexual services for consideration, represented three in five (61%) cases involving offences related to the sex trade that were completed in court between 2014/2015 and 2018/2019. The majority (71%) were cases involving obtaining sexual services from an adult (s. 286.1(1)), while 10% were obtaining sexual services from a minor (either under the new subsection 286.1(2) legislation or previous subsection 212(4)).Note Overall, there were 1,273 cases related to purchasing sexual services that were completed in court after the PCEPA, up from 96 cases in the five-year period prior to the legislation. In fact, the most common sex-trade-related offence tried in court after the PCEPA was the newly enacted obtaining sexual services from an adult (s. 286.1(1)) offence, which accounted for more than two in five (43%) of all sex-trade-related cases completed in court between 2014/2015 and 2018/2019.Note

Offences related to the profiting from others’ sexual services represented just over one-quarter (27%) of all court cases involving crimes related to the sex trade completed after the PCEPA between 2014/2015 and 2018/2019. Most (64%) of these 569 cases involved procuring offences, 250 of which were under previously existing legislation and 115 of which fell under new procuring laws introduced by the PCEPA (s. 286.3(1) and (2)). Other profiting-related cases include living on the avails and receiving material benefit offences, which together accounted for 30% of profiting cases in the post-PCEPA period. This includes living on the avails of prostitution of a minor or receiving a material benefit from a minor (98 cases) and receiving a material benefit from an adult (70 cases). The new advertising sexual services offence (s. 286.4) represented 6% of profiting-related cases (36 cases post-PCEPA).

Between 2009/2010 and 2013/2014, 4,960 stopping or communicating cases were completed in court, declining by 95% to 254 cases between 2014/2015 and 2018/2019. Said otherwise, before the new legislation, stopping or communicating offences represented the vast majority (89%) of all sex-trade-related court cases in the five-year period leading up to the PCEPA, but they represented a minority (12%) of cases after the PCEPA, as the new legislation prioritized offences relating to the purchasing and third-party profiting from others’ sexual services.

Cases involving women accused of crimes related to the sex trade saw large decline

Similar to findings from police-reported statistics, sex-trade-related court cases saw large shifts in the gender of the accused, with the number of womenNote in court declining significantly (Chart 5). In the five-year period before the PCEPA, over one in four (27%) sex-trade-related cases completed in court involved a woman accused, dropping to less than one in ten (9%) in the five-year period after PCEPA. There was also a notable decrease in the number of cases related to the sex trade involving accused women, from 1,429 to 176 (a decline of 88%). The overall number of cases involving men accused also declined, though to a lesser degree than for women (from 3,919 to 1,783, a decrease of 55%).

Chart 5 start

Data table for Chart 5

| 2009/2010 | 2010/2011 | 2011/2012 | 2012/2013 | 2013/2014 | 2014/2015 | 2015/2016 | 2016/2017 | 2017/2018 | 2018/2019 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| number of criminal court cases | ||||||||||

| Purchasing offences, men accused | 6 | 8 | 13 | 35 | 22 | 20 | 22 | 251 | 429 | 457 |

| Profiting offences, men accused | 70 | 72 | 69 | 89 | 75 | 102 | 92 | 92 | 66 | 63 |

| Stopping or communicating offences, men accused | 976 | 1,005 | 544 | 445 | 490 | 155 | 20 | 4 | 8 | 2 |

| Purchasing offences, women accused | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 5 |

| Profiting offences, women accused | 12 | 18 | 25 | 27 | 28 | 21 | 26 | 34 | 25 | 23 |

| Stopping or communicating offences, women accused | 429 | 307 | 242 | 171 | 166 | 14 | 4 | 13 | 6 | 2 |

|

0 true zero or a value rounded to zero Note: A case is one or more charges against an accused person that were processed by the courts at the same time and received a final decision. Includes court cases where a prostitution-related offence was the most serious offence in the case. Includes cases completed in adult and youth court. Data exclude cases in which the gender of the accused was unknown or a company. Information from superior courts in Ontario, Manitoba and Saskatchewan as well as municipal courts in Quebec was not available for extraction from their electronic reporting systems and was therefore not reported to the survey. Superior court information for Prince Edward Island was unavailable until 2018/2019. Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics, Integrated Criminal Court Survey. |

||||||||||

Chart 5 end

The decline in court cases involving women accused of crimes related to the sex trade was primarily driven by the decrease in stopping or communicating (s. 213) cases, which declined by 97% (from 1,315 to 39) between the five years before and after the PCEPA. This decline was on par with that for men accused (-95%; from 3,460 to 189). However, countering this decline for men were cases involving obtaining sexual services from an adult (s. 286.1(1)), a new PCEPA offence, of which there were 841 cases completed between 2014/2015 and 2018/2019.Note In contrast, there were only 8 cases involving women who were accused this offence.

After new law, women mostly in court for profiting offences, men for purchasing offences

Overall, men represented the majority of persons accused in court cases where a sex-trade-related crime was the most serious offence in the case, both in the five-year period preceding the PCEPA (73%) and in the five-year period following (91%). In the five-year period following the PCEPA, men accounted for virtually all (99%) of those accused of a purchasing offence and three in four (76%) of those accused of a profiting offence. Of the small number of women (176) in court for a sex-trade-related offence post-PCEPA, most were for procuring offences (40%),Note followed by offences related to living on the avails of the prostitution a minor or receiving a material benefit from an adult or a minor (24%). Over half (53%) of completed court cases involving women accused of profiting from the sale of others’ sexual services were for new offences introduced by the PCEPA (ss. 286.2, 286.3 and 286.4), compared with under half (45%) for men accused of a profiting-related offence.

By contrast, women were seldom tried in court for a purchasing offence. Among the women in court for a sex-trade-related crime, 5% of cases were for purchasing offences, whereas this was far more common among court cases involving men accused of a crime related to the sex trade (66%). Between 2014/2015 and 2018/2019, 1,179 completed court cases involved men accused of a purchasing offence (Chart 5), with the majority (71%) of offences being obtaining sexual services from an adult (a new offence under section 286.1(1)).

In the five-year period prior to the PCEPA, men represented four in five (81%) procuring (s. 212) cases completed in court. After the new legislation, the proportion of men accused in combined section 286.2, 286.3 and 286.4 cases completed in the five-year period after the PCEPA declined to just under three in four (73%). Consequently, the proportion of women accused in these cases had increased from 19% (s. 212) to 27% (ss. 286.2, 286.3 and 286.4).

Stopping and communicating offences (s. 213) represented the vast majority of sex-trade-related cases completed in court between 2009/2010 and 2013/2014, whether the accused was a man (88%) or a woman (92%). In the five-year period after the PCEPA, there was a large decline in the number of stopping and communicating offences processed in the courts for both men and women accused (95% and 97% declines, respectively).

Conviction rate higher for profiting offences, lower for purchasing offences

The overall conviction rateNote for court cases involving crimes related to the sex trade was the same (29%) in the five-year period before and after the PCEPA; however, this varied when analyzed by particular offence type and the gender of the accused.

Overall, higher conviction rates were seen in profiting cases related to procuring or receiving material benefit after the PCEPA (46%), whereas lower conviction rates were observed among cases related to purchasing sexual services (24%) in the same period. More specifically, among the 569 cases involving a crime related to profiting from sexual services completed in court between 2014/2015 and 2018/2019, 263 resulted in a guilty verdict. Most (60%) of these profiting offences were for procuring, following by receiving a material benefit (22%). Although the offence of advertising sexual services (s. 286.4) represented a small proportion of completed court cases overall in the five-year period after the PCEPA (2%), it had a notably high conviction rate at 81% (29 out of 36 cases found guilty). Among the 1,273 cases involving a purchasing offence, guilty findings were most common among obtaining sexual services from a minor (s. 286.1(2)), where four in five (81%) of cases completed in the five-year post-PCEPA period resulted in a guilty finding. Of note, the previous offence of obtaining sexual services from a minor (s. 212(4)) had a conviction rate nearly half that of the new offence, at 53% post-PCEPA (37 out of 70 cases found guilty). Obtaining sexual services from an adult had the lowest conviction rate among purchasing offences, with 18% found guilty between 2014/2015 and 2018/2019.Note

Stopping or communicating (s. 213) offences saw lower conviction rates in the five-year period after the PCEPA compared with the five-year period prior to (14% versus 27%).This shift was impacted by the overall decline in volume of stopping or communicating offences processed through the courts shortly after the introduction of the new legislation.

Conviction rates lower for women and higher for men after new legislation

Overall, women accused of crimes related to the sex trade were less likely to be convicted after the PCEPA, while men accused saw higher conviction rates. Between 2009/2010 and 2013/2014, the conviction rate for men was just under 1 in 5 (18%), increasing to nearly 3 in 10 (27%, representing 475 cases) after the implementation of the PCEPA, between 2014/2015 and 2018/2019. By contrast, for women accused of a sex-trade-related offence, the conviction rate dropped from nearly three in five (58%) to one in three (33%), with just 58 women convicted of an offence related to the sex trade in the five-year period after the PCEPA. These findings are consistent with one of the goals of the new legislation, which aimed to reduce the criminalization of women for selling their own sexual services, as evidenced by the fact that the vast majority of women convicted for sex trade-related offences were not convicted for activities related to the sale of their own sexual services.

With respect to conviction rates, among offences related to profiting, men were more likely to be convicted than women in both the five-year period before the PCEPA (47% versus 33%) and the five-year period after (47% versus 41%). Conviction rates were highest for men accused of obtaining sexual services from a minor (s. 286.1(2)), of which 83% of cases completed between 2014/2015 and 2018/2019 were found guilty. Though an infrequent offence in terms of the number of cases processed in the courts, advertising sexual services (s. 286.4) offences also saw high conviction rates, with 88% of men (15 out of 17) and 75% of women (12 out of 16) accused found guilty in the five-year period after the PCEPA.

Fewer women and more men sentenced to custody for sex-trade-related crimes after new legislation

As a declining number of crimes related to the sex trade involving women were processed through the courts after the PCEPA, there were few cases where a woman was convicted and sentenced to custody. Of the 57 guilty cases completed between 2014/2015 and 2018/2019 involving a woman accused, 22 (39%) were sentenced to probation and 20 (35%) were sentenced to custody. Nearly all (19 out of 20) women sentenced to custody for a crime related to the sex trade had been convicted of a profiting offence, whether procuring, living on the avails or receiving a material benefit.

In contrast, more men found guilty of a crime related to the sex trade were sentenced to custody after the PCEPA than before. In the five-year period prior, one in four (25%) convicted men were sentenced to custody, compared with half (50%) in the five-year period after the PCEPA. The volume of cases involving men sentenced to custody increased as well (from 176 to 227). Post-PCEPA, most men sentenced to custody were convicted of a profiting offence (64%), specifically procuring (whether under old or new legislation).Note The proportion of convicted men sentenced to custody was highest for profiting offences (76%), compared with purchasing offences (33%), where the more common sentence was a fine (48%).

Women sentenced less severely for stopping or communicating offences

After the PCEPA, stopping or communicating (s. 213) offences had lower conviction rates for women, with 5% of cases resulting in a conviction between 2014/2015 and 2018/2019, compared with 61% in the five-year period prior to the change in legislation. The conviction rate was largely unchanged between the two periods for section 213 cases involving a man accused (13% after the PCEPA versus 14% before). Before the PCEPA, most women who were convicted of these stopping and communicating offences were sentenced to probation (44%), followed by custody (33%). Between 2014/2015 and 2018/2019, 2 out of the 39 women tried were convicted under section 213, neither of whom were sentenced to custody.

Human trafficking charge present in three in ten profiting offence cases after new law

Human trafficking and sex-trade-related offences have historically been inter-related with overlap at the charge level (Ibrahim 2021; see Text box 3). This section explores court cases related to the sex trade that also had a human trafficking charge present in the case.Note Coinciding with a dramatic increase in the number of police-reported incidents of human trafficking in the past decade, the number of sex-trade-related court cases involving a human trafficking offence increased sharply after the introduction of the PCEPA. In the five-year period prior to the PCEPA, 0.8% of the 5,561 completed sex-trade-related cases in the courts also involved a human trafficking charge,Note compared with 8% of the 2,096 cases completed after the new legislation (2014/2015 to 2018/2019). Notably, when considering cases involving crimes related to profiting from the sale of sexual services completed after the legislation change, 3 in 10 (30%) also included a human trafficking charge, up from 1 in 10 (9%) prior to the adoption of the new law. More specifically, these human trafficking charges were most commonly charged alongside receiving a material benefit (s. 286.2) charges, of which nearly half (48%) had a human trafficking charge in the case between 2014/2015 and 2018/2019.Note Human trafficking charges were present in virtually no purchasing or stopping or communicating offences.

In the five-year period preceding the PCEPA (2009/2010 to 2013/2014), men accused of profiting-related offences in court were almost four times more likely than women accused of the same to also be charged with human trafficking (11% versus 3%). After the new legislation, both of these proportions increased and the gap narrowed between men and women as the nature of cases relating to the sex trade largely involved more serious offences (32% for men, 27% for women between 2014/2015 and 2018/2019).

Summary

This study examined changes in police-reported sex-trade-related offences before and after the introduction of the Protection of Communities and Exploited Persons Act (PCEPA), which came into force on December 6, 2014. Prior to the enactment of the PCEPA, rates of police-reported sex-trade-related incidents had been falling for two decades, with sharp declines in the years leading up to 2014. These declines were driven in part by the anticipation of incoming legislation, and more specifically by a large decline in stopping or impeding traffic offences, communicating for the purpose of offering, and providing or obtaining sexual services for consideration (Criminal Code s. 213).

The PCEPA aimed to shift the burden of criminalization from individuals who provide sexual services, who are primarily women and girls, to the purchasers of those services and third parties who profit from the sale of sexual services. Notably fewer women were accused in incidents of stopping or communicating offences in the years following the new legislation. Further, women accused in these incidents were less likely to be charged in the five-year period following the change in legislation. Moreover, information from the criminal courts for the five years prior to the PCEPA shows that the majority of women who were tried in court for these offences were convicted and many sentenced to custody. In contrast, between 2014/2015 and 2018/2019, two women were convicted for a stopping or communicating offence and none were sentenced to custody.

At the same time, while the number of men accused in incidents of stopping or communicating offences dropped considerably between 2010 and 2014, the introduction of the new offence of obtaining sexual services from an adult led to an increase in the number of men accused in sex-trade-related incidents. Over 9 in 10 of the men accused by police in incidents of this new offence were charged.

The PCEPA also aimed to shift the burden from individuals who provide sexual services to those who have economic interests in those sexual services. This was reflected in changes in the nature of the more serious crimes related to procuring or receiving material benefit from others’ sexual services. Between 2010 and 2019, the number of incidents related to these offences almost doubled. While men were more often the accused in these offences, both before and after the change in legislation, over two-thirds of individuals accused in incidents of procuring or receiving material benefit were charged by police, irrespective of the gender of the accused.

In the criminal courts, shifts in the profile of persons accused of crimes related to the sex trade were similar to those reported by police. The overall number of court cases related to the sex trade decreased post-legislation change, specifically with a decline in women accused and convicted of crimes related to the selling of sexual services. Men accounted for the majority of accused convicted in court, whether for purchasing or profiting offences. After the legislative change, 3 in 10 court cases related to profiting from sexual services also involved a human trafficking charge, up from 1 in 10 prior.

Detailed data tables

Table 1 Police-reported crime related to the sex trade, by detailed offence, Canada, 2010 to 2019

Table 2 Police-reported crime related to the sex trade, by province or territory, 2010 to 2019

Table 3 Police-reported crime related to the sex trade, by census metropolitan area, 2010 to 2019

Survey description

Uniform Crime Reporting Survey

The Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR) Survey was established in 1962 with the co-operation and assistance of the Canadian Association of Chiefs of Police. The survey is a compilation of police-reported crimes that have been substantiated through investigation from all federal, provincial and municipal police services in Canada.

Coverage of the UCR aggregate data reflects virtually 100% of the total caseload for all police services in Canada. One incident can involve multiple offences. Aggregate counts from the UCR presented in this article are based upon the most serious offence. The most serious violation is determined by police according to standardized classification rules in the UCR which consider, for instance, whether or not the offence is violent, the maximum penalty imposed by the Criminal Code and the relationship of the offender to the victim.

Incident-based Uniform Crime Reporting Survey trend file

The Incident-based Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR2) Survey trend file is a microdata survey that captures detailed information on crimes reported to and substantiated by police, including the characteristics of victims, accused persons and incidents. Coverage from the UCR2 between 2009 and 2014 is estimated at 99% of the population of Canada and includes only those police services who have consistently responded in order to allow for comparisons over time.

Homicide Survey

The Homicide Survey collects police-reported data on the characteristics of all homicide incidents, victims and accused persons in Canada. The Homicide Survey began collecting information on all murders in 1961, however a variable for occupation that identified victims as sex trade workers was not introduced until 1991. Further, a question that identified whether the homicide was a result of the victim’s occupation was added in 1997.

Whenever a homicide becomes known to police, the investigating police service completes the survey questionnaires, which are then sent to Statistics Canada. There are cases where homicides become known to police months or years after they occurred. These incidents are counted in the year in which they become known to police. Information on persons accused of homicide are only available for solved incidents (i.e., where at least one accused has been identified). Accused characteristics are updated as homicide cases are solved and new information is submitted to the Homicide Survey.

Information collected through the victim and incident questionnaires are also accordingly updated as a result of a case being solved.

The Homicide Survey recently underwent a redesign to improve data quality and enhance relevance. Changes were made to existing questions and additional questions have been added for the 2019 reporting period.

Integrated Criminal Court Survey

The Integrated Criminal Court Survey (ICCS) collects statistical information on adult and youth court cases involving Criminal Code and other federal statute offences.