Intimate partner violence in Canada, 2018: An overview

by Adam Cotter, Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics

Intimate partner violence (IPV) encompasses a broad range of behaviours, ranging from emotional and financial abuse to physical and sexual assault. Due to its widespread prevalence and its far-ranging immediate and long-term consequences for victims,Note their families, and for communities as a whole, IPV is considered a major public health problem (World Health Organization 2017). In addition to the direct impacts on victims, IPV also has broader economic consequences (Peterson et al. 2018) and has been linked to the perpetuation of a cycle of intergenerational violence, leading to additional trauma.

Many victimization surveys in Canada and elsewhere show that the overall prevalence of self-reported IPV is similar when comparing women and men. That said, looking beyond a high-level overall measure is valuable and can reveal important context and details about IPV. An overall measure often encompasses multiple types of IPV, including one-time experiences and patterns of abusive behaviour. These differences in patterns and contexts help to underscore the point that there is not one singular experience of IPV. Rather, different types of intimate partner victimization—and different profiles among various populations—exist and are important to acknowledge as they will call for different types of interventions, programs, and supports for victims.

Research to date has shown that women disproportionately experience the most severe forms of IPV (Burczycka 2016; Breiding et al. 2014), such as being choked, being assaulted or threatened with a weapon, or being sexually assaulted. Additionally, women are more likely to experience more frequent instances of violence and more often report injury and negative physical and emotional consequences as a result of the violence (Burczycka 2016). Though most instances of IPV do not come to the attention of police, women comprise the majority of victims in cases that are reported (Conroy 2021). Furthermore, homicide data have consistently shown that women victims of homicide in Canada are more likely to be killed by an intimate partner than by any other type of perpetrator (Roy and Marcellus 2019). Among solved homicides in 2019, 47% of women who were victims of homicides were killed by an intimate partner, compared with 6% of homicide victims who were men.

This article, focusing on the overall Canadian population, is one in a series of short reports examining experiences of intimate partner violence among members of different population groups, based on self-reported data from the 2018 Survey of Safety in Public and Private Spaces (SSPPS) for various populations. It explores the prevalence, nature, and impact of IPV on Canadians taking a gender-based approach by comparing the experiences of women and men.Note Experiences of IPV among Indigenous women (Heidinger 2021), sexual minority women (Jaffray 2021a) and men (Jaffray 2021b), women with disabilities (Savage 2021a), young women (Savage 2021b), and visible minority women (Cotter 2021) are examined in the other reports within this series.Note

In this article, the term “intimate partner violence” is used to refer to all forms of violence committed in the context of an intimate partner relationship (see Text box 1). Other organizations may prefer other terms, or use them interchangeably with intimate partner violence, such as spousal violence, dating violence, or domestic violence. However, these terms can exclude certain types of intimate partner violence by limiting the scope to a particular type of intimate partner relationship, or could encompass other types of violence which take place in another type of relationship but within the domestic context, such as child abuse or elder abuse (World Health Organization 2012).

Start of text box 1

Text box 1

Measuring and defining intimate partner violence

The Survey of Safety in Public and Private Spaces (SSPPS) collected information on Canadians’ experiences of intimate partner violence (IPV) since the age of 15 and in the 12 months that preceded the survey. The survey used a broad range of items covering abusive and violent behaviours committed by intimate partners, including psychological, physical, and sexual violence. The definition of partner was also broad and included current and former legally married spouses, common-law partners, dating partners, and other intimate partner relationships.

The 27 items used in the SSPPS were drawn from various sources, including the Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS), the Composite Abuse Scale Revised Short Form (CASr-SF) (Ford-Gilboe et al. 2016), and new items designed to address gaps in both of these measures (see Table 1A for a complete list of all items included in the survey, as well as their source). Including a broad range of IPV types was critical to ensuring that all forms of violence were captured in order to reflect the experiences of various individuals and populations. This includes experiences of IPV in relationships involving partners of the same or of a different gender, as well as specific experiences of IPV among men and women.

Defining and counting intimate partner violence

Intimate partner violence can be defined in a number of ways, and the definition can evolve over time to include emerging forms of IPV. For example, Statistics Canada defines police-reported intimate partner violence as violent offences that occur between current and former partners who may or may not live together (Burczycka 2018). The Royal Canadian Mounted Police (2019) defines IPV as, broadly, harm caused by an intimate partner, which takes many forms but is often the result of an attempt to gain or assert power or control over a partner.

In the SSPPS, intimate partner violence is defined as any act or behaviour committed by a current or former intimate partner, regardless of whether or not these partners lived together. In this article, intimate partner violence is broadly categorized into three types: psychological violence, physical violence, and sexual violence.

Psychological violence encompasses forms of abuse that target a person’s emotional, mental, or financial well-being, or impede their personal freedom or sense of safety. This category includes 15 specific types of abuse, including jealousy, name-calling and other put-downs, stalking or harassing behaviours, manipulation, confinement, or property damage (for a complete list of items included in this category, see Table 1A). It also includes being blamed for causing the abusive or violent behaviour, which was measured among those respondents who experienced certain forms of IPV.Note

Physical violence includes forms of abuse that involve physical assault or the threat of physical assault. In all, 9 types of abuse are included in this category, including items being thrown at the victim, being threatened with a weapon, being slapped, being beaten, and being choked (see Table 1A).

Sexual violence includes sexual assault or threats of sexual assault and was measured using two items from the CASr-SF: being made to perform sex acts that the victim did not want to perform, and forcing or attempting to force the victim to have sex.

Physical and sexual intimate partner violence are sometimes collapsed into one category, particularly when data on IPV are combined with non-IPV data in order to derive a total prevalence of criminal victimization.

Frequency of intimate partner violence

In addition to measuring the prevalence of intimate partner violence, the SSPPS also measured the frequency of each form of intimate partner violence in the past 12 months. Respondents who stated that they had experienced any of the 27 forms of abuse were asked to specify the frequency of that abuse—that is, if the abuse had happened once, a few times, monthly, weekly, or daily or almost daily within the past 12 months. This information provides additional context and nuance in highlighting the experiences of victims and when making comparisons between different populations.

Analytical approach

The analysis presented in this article takes an inclusive approach to the broad range of behaviours that comprise IPV. For the purposes of this analysis, those with at least one response of ‘yes’ to any item on the survey measuring IPV are included as having experienced intimate partner violence, regardless of the type or the frequency.

IPV data from other sources

While this analysis relies on data from the SSPPS, there are other sources of national data on IPV in Canada. Most notably, the General Social Survey on Victimization (GSS) has collected information on intimate partner violence using the Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS) every 5 years since 1999, with data for 2019 available in 2021. Unlike the SSPPS, the GSS focused on the past 5-year and past 12-month occurrence of emotional, physical, and sexual violence committed by a current or former legally married or common-law spouse or partner. In 2014, dating violence was captured through the addition of a brief module, which was expanded to align with the CTS in 2019.

The advantage of the GSS is that it allows for analysis of this type of intimate partner violence over time, as well as greater international comparability. On the other hand, the SSPPS includes a broader scope of abusive behaviours and potential abusive relationships, and the key ability to provide a measure of lifetime prevalence and a measure of frequency of all types of behaviour, beyond those that are physically or sexually violent. IPV data from the GSS will be published in future Juristat articles.

Data on IPV are also collected in the Uniform Crime Reporting Survey (UCR). The UCR includes details on the incidents, accused, and victims, but is limited only to those incidents that come to the attention of police. For the most recent UCR IPV data, see Conroy (2021).

End of text box 1

More than four in ten women and one-third of men have experienced some form of IPV in their lifetime

While physical and sexual assault are the most overt forms of intimate partner violence (IPV), they are not the only forms of violence that exist in intimate partner relationships. IPV also includes a variety of behaviours that may not involve physical or sexual violence or rise to the current level of criminality in Canada, but nonetheless cause victims to feel afraid, anxious, controlled, or cause other negative consequences for victims, their friends, and their families.

On the whole, experiences of IPV are relatively widespread among both women and men. Overall, 44% of women who had ever been in an intimate partner relationship—or about 6.2 million women 15 years of age and older—reported experiencing some kind of psychological, physical, or sexual violence in the context of an intimate relationship in their lifetime (since the age of 15Note ) (Table 1A, Table 2).Note Among ever-partneredNote men, 4.9 million reported experiencing IPV in their lifetime, representing 36% of men.Note

By far, psychological abuse was the most common type of IPV, reported by about four in ten ever-partnered women (43%) and men (35%) (Table 1A, Table 2). This was followed by physical violence (23% of women versus 17% of men) and sexual violence (12% of women versus 2% of men). Notably, nearly six in ten (58%) women and almost half (47%) of men who experienced psychological abuse also experienced at least one form of physical or sexual abuse. Regardless of the category being measured, significantly higher proportions of women than men had experienced violence.

In addition to having a higher overall likelihood of experiencing psychological, physical and sexual IPV than men, women who were victimized were also more likely to have experienced multiple specific abusive behaviours in their lifetime. Nearly one in three (29%) women who were victims of IPV had experienced 10 or more of the abusive behaviours measured by the survey, nearly twice the proportion than among men who were victims (16%). In contrast, men who were victims were more likely to have experienced one, two, or three abusive behaviours (53%), compared with 38% of women.

Most forms of intimate partner violence more prevalent among women

Among women who experienced IPV, the most common abusive behaviours were being put down or called names (31%), being prevented from talking to others by their partner (29%), being told they were crazy, stupid, or not good enough (27%), having their partner demand to know where they were and who they were with at all times (19%), or being shaken, grabbed, pushed, or thrown (17%) (Table 1A).

Four of these five—being prevented from talking to others (27%), being put down (19%), being told they were crazy, stupid, or not good enough (16%), and having their partner demand to know their whereabouts (15%)—were also the most common types of IPV experienced by men. However, the prevalence among women was higher for each of these abusive behaviours, as it was for almost all IPV behaviours measured by the survey.

Of the 27 individual IPV behaviours measured by the survey, all but two were more prevalent among women than men. Of the two exceptions, one was being slapped (reported by 11% of both women and men, but was the fifth most common type of IPV among men). The other was an item asked only of those who reported a minority sexual identity (lesbian, gay, bisexual, or another sexual orientation that was not heterosexual): having a partner reveal, or threaten to reveal, their sexual orientation or relationship to anyone who they did not want to know this information. This was reported by 6% of sexual minority men and 7% of sexual minority women, a difference that was not statistically significant.

There were several types of IPV behaviour that were more than five times more prevalent among women than among men. These forms of violence tended to be the less common but more severe acts measured by the survey. Women, relative to men, were considerably more likely to have experienced the following abusive behaviours in their lifetime: being made to perform sex acts they did not want to perform (8% versus 1%), being confined or locked in a room or other space (3% versus 0.5%), being forced to have sex (10% versus 2%), being choked (7% versus 1%), and having harm or threats of harm directed towards their pets (4% versus 0.8%).

Nearly seven in ten women and men experienced IPV by one partner

Though their overall prevalence of IPV differed, women and men reported similar numbers of abusive partners in their lifetimes, with most indicating that one intimate partner was responsible for the abuse they had experienced. This was the case for 68% of women and 69% of men who experienced IPV.

A smaller proportion of victims reported having multiple abusive partners. One in five (22%) women said they had had two abusive partners since the age of 15, while fewer reported three (6%), four (1%), or five or more (1%) abusive partners. These proportions did not differ from those reported by men who experienced IPV (20%, 4%, 1%, and 1%, respectively).

Women more likely to experience fear, anxiety, and feelings of being controlled or trapped by a partner

Measures of intimate partner violence often take into account the levels of fear victims experience. Being afraid of a partner can indicate that experiences of violence are more coercive, relatively more severe, and more likely to reflect a pattern of behaviour by an abusive partner (Johnson and Leone 2005). This understanding of patterns and impacts of IPV underlie legislative projects that have been undertaken; for example, in 2015, the United Kingdom introduced the criminal offence of “coercive control”, designed to criminalize forms of abuse that may not, on their own, constitute criminal behaviour, but occur on a repeated or continuous basis and cause the victim to fear for their safety from violence or result in substantial adverse effects (Home Office 2015).Note In Canada, meanwhile, a 2021 amendment to the Divorce Act introduced definitions of family violence to the legislation, including a specific mention of coercive and controlling behaviours, which may include specific acts that are not criminal but is a pattern of abusive behaviours designed to control or dominate another (Department of Justice 2021).

Fear is considerably more common among women who experience IPV; nearly four in ten (37%) women who were IPV victims said that they were afraid of a partner at some point in their life because of their experiences, well above the proportion of men (9%).

Notably, the type of IPV experienced is associated with the likelihood of experiencing fear. Among victims of IPV who experienced solely psychological forms of abuse, 12% of women and 4% of men stated that they had ever been afraid of a partner. In contrast, 55% of women who experienced physical or sexual IPV feared a partner at some point, as did 14% of men.

Beyond the broad categories, looking at the volume of different abusive behaviors an individual experiences suggests that those who experience multiple types of violence experience greater levels of fear. For example, those who experienced the largest range of IPV behaviours were considerably more likely to have ever feared a partner. Of women who had experienced one type of IPV since age 15, 4% had been afraid of a partner at some point. This increased to 10% and 15% among those who experienced 2 or 3 behaviours, respectively, ultimately reaching 74% among women who experienced 10 or more types of IPV. Though far fewer men ever feared their partner, the pattern was similar as 2% of men who experienced one type of IPV reported fearing a partner at some point, increasing to 28% among men who experienced 10 or more types. These findings are especially poignant since most people who experienced IPV stated that the abuse had been perpetrated by one partner, suggesting that many individuals—particularly women—are subject to a broad range of abusive, controlling, and violent behaviours committed by one partner whom they fear.

While adding important context, fear is just one of several possible emotional and psychological impacts of IPV. Other emotional impacts of IPV were therefore included in the SSPPS to provide additional context to experiences of abuse; namely, feeling controlled or trapped by an abusive partner, or feeling anxious or on edge due to a partner’s abusive behaviour.

These emotions were more common than fear for both women and men, and the gender gap was smaller. For both women and men, feeling anxious or on edge (57% of women and 36% of men) was most common, followed by feeling controlled or trapped by an abusive partner (43% of women and 24% of men). As with feelings of fear, those who experienced a higher number of different types of abusive behaviour measured by the SSPPS reported these emotional impacts far more often.

More than one in ten women and men experienced IPV in the past 12 months

In addition to information on intimate partner violence that people experience over their lifetime, the SSPPS asked questions about partner abuse that had happened in the previous year. In the 12 months preceding the survey, 12% of women and 11% of men were subjected to some form of IPV, proportions that were not statistically different (Table 1A, Table 2). Women and men were equally as likely to report experiencing psychological abuse (12% and 11%, respectively) or physical or sexual violence (3% each). That said, while the prevalence of physical violence was similar between women (2.4%) and men (2.8%), sexual violence was about three times more common among women (1.2%) than men (0.4%).

Mirroring the lifetime data, the four most common types of IPV reported by women in the past 12 months were being put down or called names (8%), being told they were crazy, stupid, or not good enough (7%), having their partner be jealous and not want them to talk to other men or women (5%), and having their partner demand to know where they were and who they were with (3%). These were also the four most common IPV behaviours reported by men (6%, 5%, 7%, and 4%, respectively).

Some forms of IPV were more frequently reported by men than women in the past 12 months, unlike what was seen in the lifetime prevalence data. In the past 12 months, men were more likely than women to have experienced their partner being jealous and preventing them from talking to others (7% versus 5%), demanding to know where they were and who they were with at all times (4% versus 3%), slapping them (1.7% versus 0.8%), or hitting them with a fist or object, biting, or kicking them (1.3% versus 0.7%).

On the other hand, 12 of the 27 behaviours measured were higher among women than men. Notably, this included both measures of sexual assault, being choked, threats to harm or kill them or someone close to them, being harassed, and being followed or having their partner hang around their home or workplace.

More than one-quarter of IPV victims experienced violence or abuse monthly or more in the previous year—and one in ten women experienced it almost daily

Intimate partner violence tends to happen repeatedly, instead of on a one-time basis. About one in five people who experienced IPV in the 12 months preceding the survey said that it occurred once during that time. This was the case for a slightly higher proportion of men who were victims (22%) than women (17%).

Instead, among IPV victims, 30% of women and 27% of men stated that at least one type of IPV (physical, sexual or psychological) had occurred repeatedly: either on a monthly basis or more often (Table 1B). Likewise, over half of women (54%) and men (51%) who experienced IPV said that at least one specific abusive behaviour occurred “a few times” over the twelve month period—that is, more than one time but less than on a monthly basis. In both instances, the differences between women and men who were victims were not statistically different; however, women were twice as likely as men to have experienced at least one abusive behaviour on a daily or almost daily basis in the past 12 months (12% versus 6%)—suggesting yet another way in which IPV disproportionately impacts women.

In part due to relatively small sample size, there were few statistically significant differences between women and men in terms of the frequency of each individual behaviour. However, when differences were present, it was always the case that women were more likely than men to report a behaviour happening once a month or more, while men were more likely to report a behaviour happening one time in the past 12 months (Table 1B).

Even among the types of IPV that were less common, most women who were victims of IPV said that the behaviours occurred more than once in the past 12 months. For example, while 1% of all women said that an intimate partner forced or tried to force them to have sex in the past 12 months, three-quarters (76%) of those women said that it happened more than once. Overall, one in five (20%) women who experienced sexual violence committed by an intimate partner in the past 12 months said that it happened monthly or more in the past 12 months. The frequency with which women experience this kind of IPV is particularly notable, as these types of violence are often also considered to be the most severe.

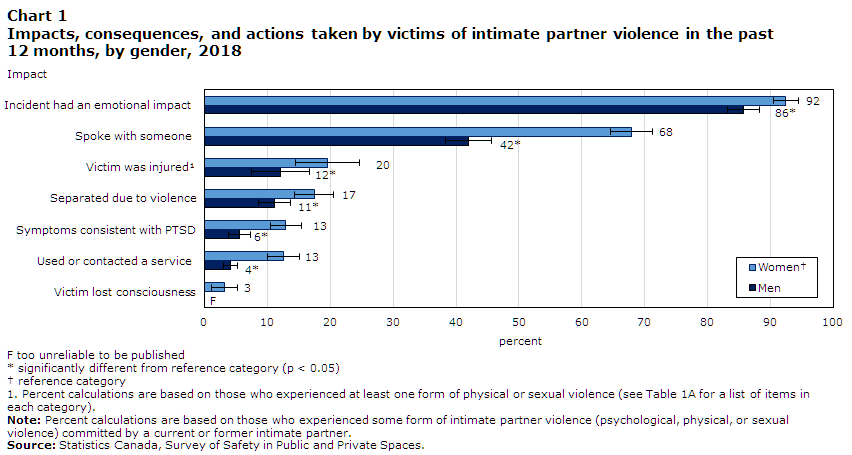

Women more likely to report emotional, physical consequences of IPV

About nine in ten victims of IPV in the past 12 months—both women (92%) and men (86%)—said that the incident had an emotional impact on them (Chart 1). Women, who experienced IPV more frequently and in forms that were often more severe, reported more extreme impacts on their physical and psychological health and on their way of life. For example, many women who were victims of IPV were injuredNote (20%), separated from their partner due to the violence (17%), and had symptoms consistent with a suspicion of post-traumatic stress disorderNote (PTSD) (13%).

Chart 1 start

Data table for Chart 1

| Impact | WomenData table for Chart 1 Note † | Men | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| percent | standard error | percent | standard error | |

| Incident had an emotional impact | 92 | 1.0 | 86Note * | 1.3 |

| Spoke with someone | 68 | 1.7 | 42Note * | 1.9 |

| Victim was injuredData table for Chart 1 Note 1 | 20 | 2.6 | 12Note * | 2.4 |

| Separated due to violence | 17 | 1.6 | 11Note * | 1.3 |

| Symptoms consistent with PTSD | 13 | 1.2 | 6Note * | 0.9 |

| Used or contacted a service | 13 | 1.3 | 4Note * | 0.5 |

| Victim lost consciousness | 3 | 1.1 | Note F: too unreliable to be published | Note ...: not applicable |

|

... not applicable F too unreliable to be published

Source: Statistics Canada, Survey of Safety in Public and Private Spaces. |

||||

Chart 1 end

Notably, a considerable proportion of men who experienced IPV suffered similar consequences: 12% were injured, 11% were separated due to the violence, and 6% had symptoms consistent with PTSD.

These findings may suggest a cumulative impact of violence, as those who experienced IPV more frequently tended to report greater impacts. For example, about one in 20 women who experienced IPV once (4%) or a few times (6%) in the past 12 months reported symptoms consistent with PTSD. Among women who experienced IPV on a monthly basis or more, almost one in three (30%) reported such symptoms. Similarly, one-third (32%) of women who experienced IPV monthly or more were separated from their partner due to the violence, compared with about one in ten of those who experienced IPV once (9%) or a few times (12%).

In addition to these impacts, there were also some differences in the actions taken by women and men who were victims of IPV. Women were considerably more likely to have spoken with someone about the abuse or violence they experienced (68%, compared with 42% of men). Women (13%) were also more likely than men (4%) to have used or contacted a victims’ service because of the abusive or violent behaviours they had experienced in the past 12 months.

The gender gap in seeking out both formal and informal supports is consistently seen in Canadian self-report surveys (Cotter and Savage 2019; Cotter 2018; Burczycka 2016). Research suggests that many factors contribute to this pattern. For example, gender norms surrounding masculinity can minimize men’s help-seeking behaviours in a number of contexts, not only limited to IPV victimization (Ansara and Hindin 2010; Lysova et al. 2020). In other words, men are less likely to seek informal or formal help in the first place—and, if they do seek out such help, there are generally fewer services for IPV victims available for men than for women (Ansara and Hindin 2010; Lysova et al. 2020).

In addition to its correlation with more severe impacts on victims, a higher frequency of IPV was associated with greater likelihood of the violence coming to the attention of police. Women who experienced IPV on a monthly basis or more (13%) were more likely to say that the abuse had come to the attention of police, compared to those who had experienced IPV once (2%) or a few times (5%). Regardless of frequency, however, the vast majority of IPV did not come to the attention of police. This could reflect the fact that some of the IPV behaviours measured may not be perceived by victims as a criminal matter or as something that can or should be reported to police. According to the 2014 General Social Survey, the two most common reasons for not reporting spousal violence to the police were a belief that the abuse was a private or personal matter and a perception that it was not important enough to report (Burczycka 2016).

As noted, the majority of IPV victims had not used or consulted a formal service in the past 12 months. The most common reasons given by IPV victims who did not use these services were that they didn’t want or need help (51% of women and 56% of men) or that the incident was too minor (38% of women and 29% of men). A small number of victims did not use or contact any services due to logistical issues or barriers to access—there were none available (1% of all victims), there were none available in the victims’ language (0.8%), they were too far away from any services (0.5%), or there was a waiting list (0.5%).Note

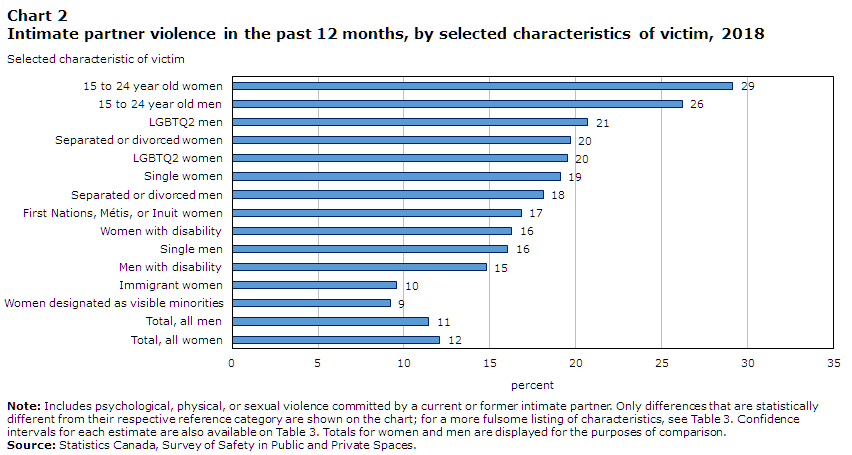

IPV much more common among certain populations

In addition to gender, other individual and socioeconomic characteristics intersect to impact the likelihood of experiencing intimate partner violence (Table 3). For example, the prevalence of IPV was notably higher among Indigenous women (see Heidinger 2021), LGBTQ2 women (see Jaffray 2021a), LGBTQ2 men (see Jaffray 2021b), women with disabilities (Savage 2021a), and young women (see Savage 2021b), both since age 15 and in the past 12 months.

Victimization research has consistently shown that age is a major risk factor, with younger people being more likely to be victims of violent crime (Cotter and Savage 2019; Perreault 2015). This is also the case with IPV. Three in ten (29%) women 15 to 24 years of age reported having experienced IPV in the past 12 months, more than double the proportion found among women between the ages of 25 to 34 or 35 to 44, and close to six times higher than that among women 65 years of age or older (Table 3, Chart 2). Likewise, for men, 26% of 15- to 24-year-olds had experienced some form of IPV in the past 12 months, declining to 5% among those 65 years of age and older. Research has shown that adolescence and young adulthood, when many are negotiating intimate relationships and boundaries for the first time, is a time of higher risk for IPV (Johnson et al. 2015). For more information on young women who experienced IPV, see Savage (2021b).

Chart 2 start

Data table for Chart 2

| Selected characteristic of victim | Percent |

|---|---|

| 15 to 24 year old women | 29 |

| 15 to 24 year old men | 26 |

| LGBTQ2 men | 21 |

| Separated or divorced women | 20 |

| LGBTQ2 women | 20 |

| Single women | 19 |

| Separated or divorced men | 18 |

| First Nations, Métis, or Inuit women | 17 |

| Women with disability | 16 |

| Single men | 16 |

| Men with disability | 15 |

| Immigrant women | 10 |

| Women designated as visible minorities | 9 |

| Total, all men | 11 |

| Total, all women | 12 |

|

Note: Includes psychological, physical, or sexual violence committed by a current or former intimate partner. Only differences that are statistically different from their respective reference category are shown on the chart; for a more fulsome listing of characteristics, see Table 3. Confidence intervals for each estimate are also available on Table 3. Totals for women and men are displayed for the purposes of comparison. Source: Statistics Canada, Survey of Safety in Public and Private Spaces. |

|

Chart 2 end

Indigenous (First Nations, Métis, and Inuit) women (61%) and men (54%) were more likely to have been victims of IPV in their lifetime compared with their non-Indigenous counterparts (44% and 36%, respectively) (Table 3).Note Indigenous women (17%) were also more likely than non-Indigenous women (12%) to have experienced IPV in the past 12 months. For more information, see Heidinger (forthcoming 2021).

Notably, the prevalence of IPV in the past 12 months among women living in rural areas (12%) was the same as that among women living in urban Canada (12%), while it was higher among men residing in urban areas (12%) compared with those in rural Canada (9%). For rural victims of IPV, feelings of isolation or being trapped due to IPV may be exacerbated further due to remoteness, lower availability of services, or trouble leaving the community (Women’s Shelters Canada 2020).

Lower household income associated with lifetime experiences of IPV

Lifetime experiences of IPV were more common among women (57%) and men (53%) who reported a household income of less than $20,000 in 2018 (Table 3). These proportions were not significantly different from each other, but were higher than any other income group for either women or men.

There were no significant differences in the past-12 month prevalence of IPV when looking at women of varying household incomes, which suggests that income itself is not necessarily a predictor of experiencing IPV. Rather, experiencing IPV in one’s lifetime may be a factor that leads to relatively lower income later in life, as the SSPPS measured income at the time of the survey but asked about any incidents of IPV since the age of 15. Furthermore, for those who experience IPV, having a lower income may pose additional challenges or barriers to leaving a violent relationship.

IPV linked to early experiences of child abuse

Slightly more women (28%) than men (26%) reported that, at some point before the age of 15, they were physically or sexually abused by an adult; women were much more likely than men to have been sexually abused (12% versus 4%), while physical abuse was more common among men (25%) than women (22%). Victimization surveys and research consistently show that adverse childhood experiences are associated with a higher risk of being a victim of violence during adulthood (Burczycka 2017; Widom et al. 2008). This is particularly the case with intimate partner violence; women with a history of physical or sexual abuse before the age of 15 were about twice as likely as women with no such history to have experienced IPV either since age 15 (67% versus 35%) or in the past 12 months (18% versus 10%).

This pattern was also evident among men; over half (53%) of those who were physically or sexually abused during childhood reported experiencing IPV at some point in their lifetime, while this was the case for three in ten (30%) men who were not abused during childhood. Likewise, men who were abused during childhood were more likely than those who were not to have experienced IPV in the past 12 months (17% versus 10%).

In a similar way, emotional abuse during childhood has been shown to be associated with an increased risk of intimate partner victimization in adulthood (Richards et al. 2017). This was also the case when it came to harsh parenting—that is, having been slapped, spanked, made to feel unwanted or unloved, or been neglected or having basic needs go unmet by parents or caregivers. Such experiences were reported by 65% of women and 62% of men, who subsequently were more likely to report IPV in their lifetime. Approximately half of women (54%) and men (45%) who experienced harsh parenting or neglect had also experienced IPV since age 15, compared with 25% and 21%, respectively, who did not experience harsh parenting.

Research has shown that childhood experiences of violence in the home are associated with an increased risk of violent victimization. That is, the likelihood of future perpetration of violence as well as victimization is increased among people exposed to violence in childhood, as individuals may learn to expect violence as part of an interpersonal relationship and model this behaviour in their own lives (Neppl et al. 2019; Richards et al. 2017; Widom et al. 2014). Findings from the SSPPS support this: two-thirds (64%) of women who were exposed to violence between their parents or other adults during childhood experienced violence in their own relationship at some point in their adult lives, compared with 41% of women not exposed to such violence as a child. Similarly, 59% of women who were exposed to emotional abuse between their parents or caregivers subsequently experienced IPV, while this was the case for 32% of women who were not.

Among men, there was an even wider gap between those who were exposed to violence and those who were not than what was seen among women. Close to six in ten (58%) men who were exposed to violence between their parents or other adults during childhood experienced IPV in their lifetime, compared with 33% of men who were not. Likewise, more than half (53%) of men who were exposed to emotional abuse between parents or caregivers reported IPV in their own relationships, a proportion that was more than double that among men who were not (25%).

Start of text box 2

Text box 2

Lifetime violent victimization

While the analysis in this report focused on violence perpetrated by intimate partners, a fulsome analysis of experiences of gender-based violence also includes experiences of violence perpetrated by those other than intimate partners. This text box examines lifetime experiences of all violent victimization (physical and sexual assault) measured by the Survey of Safety in Public and Private Spaces (SSPPS), including both intimate partner violence and violence that happens in other contexts outside of intimate partner relationships.

Close to half of women have been physically or sexually assaulted in their lifetime

Understanding experiences of violent victimization across the life course—both within and outside of intimate partnerships— is important when it comes to understanding the population that is affected, developing services and prevention programs, and predicting mental and physical health needs. As such, a measure of lifetime victimization was identified as a data gap to be addressed when developing the SSPPS.Note

When combining violence committed by intimate partners and violence committed by other perpetrators, more women (45%) stated that they have been physically or sexually assaulted at least once since the age of 15 than men (40%) (Table 4).

One in three women sexually assaulted in their lifetime

The overrepresentation of women as victims of violence was largely driven by sexual assault, as one-third (33%) of women have been sexually assaulted at some point since age 15—more than three times the proportion among men (9%) (Table 4, Chart 3). Both intimate partner sexual assault (12% versus 2%) and non-intimate partner sexual assault (30% versus 8%) were notably higher among women than men.

Chart 3 start

Data table for Chart 3

| Physical assault | Sexual assault | Total violent victimization | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| percent | ||||

| WomenData table for Chart 3 Note † | Intimate partnerData table for Chart 3 Note 1 | 23.0 | 11.5 | 25.7 |

| Non-intimate partner | 26.1 | 30.2 | 38.7 | |

| Total | 35.0 | 33.3 | 45.2 | |

| Men | Intimate partnerData table for Chart 3 Note 1 | 16.5Note * | 2.0Note * | 17.0Note * |

| Non-intimate partner | 33.3Note * | 8.2Note * | 35.4Note * | |

| Total | 37.9Note * | 9.1Note * | 39.6Note * | |

Source: Statistics Canada, Survey of Safety in Public and Private Spaces. |

||||

Chart 3 end

In contrast, women (35%) were slightly less likely than men (38%) to have been physically assaulted at some point since age 15. The gendered nature of this violence is notable here: while physical assault outside of intimate partner relationships was more common for men (33%) than women (26%), physical assault within an intimate relationship was more common among women (23%) than men (17%).

For women, the most common type of assault differed depending on the type of relationship. When looking at violence committed by an intimate partner, physical assault was more common than sexual assault. The reverse was true when looking at violence not committed by an intimate partner. For men, regardless of the relationship to the perpetrator, physical assault was far more common than sexual assault. Similar patterns were seen in the past-12 month data (Table 5).

In every province and territory, women more likely than men to be victims of physical or sexual IPV

In each of the provinces and territories, women were more likely than men to have experienced physical or sexual assault committed by an intimate partner since the age of 15 (Table 6). When combining intimate partner and non-intimate partner violence, the lifetime prevalence was higher among women than men in Prince Edward Island, New Brunswick, Quebec, Ontario, Saskatchewan, Alberta, and British Columbia. In every other province and each of the territories, there was no significant difference in the prevalence of violent victimization since age 15 when comparing women and men. Of note, between half and two-thirds of all women have experienced physical or sexual assault since the age of 15 in Nova Scotia (49%), Alberta (50%), British Columbia (50%), Nunavut (57%), Northwest Territories (61%), and Yukon (66%).

End of text box 2

Detailed data tables

Table 2 Intimate partner violence, since age 15 and in the past 12 months, Canada, 2018

Survey description

In 2018, Statistics Canada conducted the first cycle of the Survey of Safety in Public and Private Spaces (SSPPS). The purpose of the survey is to collect information on Canadians’ experiences in public, at work, online, and in their intimate partner relationships.

The target population for the SSPPS is the Canadian population aged 15 and older, living in the provinces and territories. Canadians residing in institutions are not included. This means that the survey results may not reflect the experiences of intimate partner violence among those living in shelters, institutions, or other collective dwellings. Once a household was contacted, an individual 15 years or older was randomly selected to respond to the survey.

In the provinces, data collection took place from April to December 2018 inclusively. Responses were obtained by self-administered online questionnaire or by interviewer-administered telephone questionnaire. Respondents were able to respond in the official language of their choice. The sample size for the 10 provinces was 43,296 respondents. The response rate in the provinces was 43.1%.

In the territories, data collection took place from July to December 2018 inclusively. Responses were obtained by self-administered online questionnaire or by interviewer-administered in-person questionnaire. Respondents were able to respond in the official language of their choice. The sample size for the 3 territories was 2,597 respondents. The response rate in the territories was 73.2%.

Non-respondents included people who refused to participate, could not be reached, or could not speak English or French. Respondents in the sample were weighted so that their responses represent the non-institutionalized Canadian population aged 15 and older.

Data limitations

As with any household survey, there are some data limitations. The results are based on a sample and are therefore subject to sampling errors. Somewhat different results might have been obtained if the entire population had been surveyed.

For the quality of estimates, the lower and upper bounds of the confidence intervals are presented. Confidence intervals should be interpreted as follows: If the survey were repeated many times, then 95% of the time (or 19 times out of 20), the confidence interval would cover the true population value.

References

Ansara, D.L. and Hindin, M.J. 2010. “Formal and informal help-seeking associated with women’s and men’s experiences of intimate partner violence in Canada.” Social Science & Medicine, Vol. 70. p. 1011-1018.

Breiding, M.J., Chen J., and Black, M.C. 2014. Intimate Partner Violence in the United States — 2010. Atlanta, GA National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Burczycka, M. 2019. "Police-reported intimate partner violence in Canada, 2018." In Family violence in Canada: A statistical profile, 2018. Juristat. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 85-002-X.

Burczycka, M. 2017. "Profile of Canadian adults who experienced childhood maltreatment." In Family violence in Canada: A statistical profile, 2015. Juristat. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 85-002-X.

Burczycka, M. 2016. “Trends in self-reported spousal violence in Canada, 2014.” In Family violence in Canada: A statistical profile, 2014. Juristat. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 85-002-X.

Conroy, S. 2021. Family violence in Canada: A statistical profile, 2019. Juristat. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 85-002-X.

Cotter, A. 2021. “Intimate partner violence: Experiences of visible minority women in Canada, 2018.” Juristat. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 85-002-X.

Cotter, A. and Savage, L. 2019. “Gender-based violence and inappropriate sexual behaviour in Canada, 2018: Initial findings from the Survey of Safety in Public and Private Spaces.” Juristat. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 85-002-X.

Cotter, A. 2018. “Violent victimization of women with disabilities in Canada, 2014.” Juristat. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 85-002-X.

Department of Justice Canada. 2021. Divorce and Family Violence. (accessed 1 March 2021).

Ford-Gilboe, M., Wathen, C.N., Varcoe, C., MacMillan, H.L., Scott-Storey, K., Mantler, T., Hegarty, K. and N. Perrin. 2016. “Development of a brief measure of intimate partner violence experiences: The Composite Abuse Scale (Revised)—Short Form (CASR-SF).” BMJ Open. Vol. 6, no. 12.

Heidinger, L. 2021. “Intimate partner violence: Experiences of First Nations, Métis, and Inuit women in Canada, 2018.” Juristat. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 85-002-X.

Home Office. 2015. Controlling or Coercive Behaviour in an Intimate or Family Relationship—Statutory Guidance Framework. (accessed 25 February 2021).

Jaffray, B. 2020. “Experiences of violent victimization and unwanted sexual behaviours among gay, lesbian, bisexual and other sexual minority people, and the transgender population, in Canada, 2018”. Juristat. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 85-002-X.

Jaffray, B. 2021a. “Intimate partner violence: Experiences of sexual minority women in Canada, 2018.” Juristat. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 85-002-X.

Jaffray, B. 2021b. “Intimate partner violence: Experiences of sexual minority men in Canada, 2018.” Juristat. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 85-002-X.

Johnson, M.P. and Leone, J.M. 2005. "The differential effects of intimate terrorism and situational couple violence: Findings from the National Violence Against Women Survey." Journal of Family Issues. Vol. 26, no. 3. p. 322‑349.

Johnson, W.L., Manning, W.D., Giordano, P.C. and M.A. Longmore. 2015. “Relationship context and intimate partner violence from adolescence to young adulthood.” Journal of Adolescent Health. Vol. 57, no. 6. p. 631-636.

Lysova, A., Hanson, K., Dixon, L., Douglas, E. M., Hines, D. A., and E.M. Celi. 2020. “Internal and external barriers to help seeking: Voices of men who experienced abuse in the intimate relationships.” International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology. Advance online publication.

Neppl, T.K., Lohman, B.J., Senia, J.M., Kavanaugh, S.A., and M. Cui. 2019. “Intergenerational continuity of psychological violence: Intimate partner relationships and harsh parenting.” Psychology of Violence. Vol. 9, no. 3. p. 298-307.

Perreault, S. 2015. "Criminal victimization in Canada, 2014." Juristat. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 85-002-X.

Perreault, S. 2020a. “Gender-based violence: Unwanted sexual behaviours in Canada’s territories, 2018.” Juristat. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 85-002-X.

Perreault, S. 2020b. “Gender-based violence: Sexual and physical assault in Canada’s territories, 2018.” Juristat. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 85-002-X.

Peterson, C., Kearns, M.C., McIntosh, W.L., Estefan, L.F., Nicolaidis, C., McCollister, K.E., Gordon, A., and C. Florence. 2018. “Lifetime economic burden of intimate partner violence among U.S. adults.” American Journal of Preventative Medicine. Vol. 55, no. 4. p. 433-444.

Richards, T.N., Tillyer, M.S. and E.M. Wright. 2017. “Intimate partner violence and the overlap of perpetration and victimization: Considering the influence of physical, sexual, and emotional abuse in childhood.” Criminology and Criminal Justice Faculty Publications. No. 46.

Roy, J. and S. Marcellus. 2019. “Homicide in Canada, 2018.” Juristat. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 85-002-X.

Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP). 2019. Intimate Partner Violence and Abuse. (accessed 25 February 2021).

Savage, L. 2021a. “Intimate partner violence: Experiences of women with disabilities in Canada, 2018.” Juristat. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 85-002-X.

Savage, L. 2021b. “Intimate partner violence: Experiences of young women in Canada, 2018.” Juristat. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 85-002-X.

Statistics Canada. 1993. “The violence against women survey.” The Daily. November 18. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 11-001-E.

Widom, C. S., Czaja, S. J. and M. A. Dutton. 2008. “Childhood victimization and lifetime revictimization.” Child Abuse & Neglect. Vol. 32. p. 785-796.

Widom, C.S., Czaja, S.J. and M.A. Dutton. 2014. “Child abuse and neglect and intimate partner violence victimization and perpetration: A prospective investigation.” Child Abuse & Neglect. Vol. 38, no. 4. p. 650-663.

Women’s Shelters Canada. 2020. “Special issue: The impact of COVID-19 on VAW shelters and transition houses.” Shelter Voices.

World Health Organization. 2012. Understanding and Addressing Violence Against Women. (accessed 25 February 2021).

World Health Organization. 2017. Violence Against Women. (accessed 8 January 2021).

- Date modified: