Experiences of unwanted sexualized and discriminatory behaviours and sexual assault among students at Canadian military colleges, 2019

by Ashley Maxwell, Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics

Highlights

- In 2019, most (68%) Canadian military college (CMC) students witnessed or experienced unwanted sexualized behaviours in a postsecondary setting. The most common types of behaviours that were witnessed or experienced by CMC students were sexual jokes, inappropriate discussions about sex life and inappropriate sexual comments about appearance or body.

- Overall, women were more likely than men CMC students to personally experience unwanted sexualized behaviours (52% versus 31%), and they were also more likely to consider these behaviours as offensive. The largest gap among the behaviours reported was for unwanted sexual attention, such as whistles or “catcalls”, which women CMC students were six times more likely to personally experience than men (24% versus 4%).

- Two in five (40%) CMC students witnessed or experienced discriminatory behaviours in a postsecondary setting in the previous 12 months. The most common form of discrimination that was witnessed or experienced at Canadian military colleges was the suggestion that a man does not act like a man is supposed to act.

- One in six (17%) CMC students personally experienced some form of discrimination. Overall, women (33%) were more likely than men (13%) CMC students to personally experience discriminatory behaviours.

- More than six times as many women (28%) as men (4.4%) were sexually assaulted during their time as CMC students. More specifically, during the previous 12 months, 15% of women and 3.6% of men students were sexually assaulted. Sexual touching was the most common form of sexual assault for both women and men students.

- CMC students who experienced unwanted sexualized or discriminatory behaviours most frequently identified that these events occurred on campus (93% and 86%, respectively) and in environments that are often filled with people. Additionally, many students indicated that unwanted sexualized behaviours occurred at an off-campus restaurant or bar (84%).

- The perpetrators of unwanted sexualized or discriminatory behaviours were often fellow students from Canadian military colleges (94% and 86%, respectively).

- Women were more likely than men to experience emotional or mental health impacts from the unwanted sexualized or discriminatory behaviours that they experienced. Few CMC students overall indicated that their schooling was impacted by their experiences.

- CMC students who experienced unwanted sexualized or discriminatory behaviours in a postsecondary setting rarely spoke to someone associated with their school about the behaviours they experienced, but they were often aware of resources available to assist them.

- Most CMC students chose not to intervene, seek help or take other action when they witnessed unwanted sexualized or discriminatory behaviours, often because they did not think the situation was serious enough. Many women, in particular, did not act when witnessing sexualized behaviours because they felt uncomfortable (31%).

- Most CMC students felt safe on and around their military college campuses. Women and those who experienced unwanted sexualized behaviours or sexual assault were less likely to feel safe, than men and those who did not experience these types of behaviours.

Unwanted sexualized behaviours include acts other than sexual assault, and can range from sexual jokes to inappropriate discussions of a person’s sex life. While recent social movements such as #MeToo have largely focused on victims’ experiences of sexual assault, there is a continuum of harmful unwanted and inappropriate sexualized behaviours that are not necessarily criminal in nature. Research has shown that women tend to be the targets of such behaviours more often than men (Antecol and Cobb-Clark 2001; Conroy and Cotter 2017; Maher 2010; Snyder et al. 2012). Unwanted sexualized behaviours can have widespread impacts on those who experience them. They can also contribute to a negative culture in which individuals may feel targeted or vulnerable, and others may view these types of behaviours as acceptable (Sadler et al. 2018). In recent years, many organizations and institutions have started to look more closely at these types of behaviours in order to understand how to better support those who have been victimized and to prevent them from continuing to occur.

The rise of concern surrounding unwanted sexualized behaviours has prompted conversations on sexual consent and what constitutes acceptable behaviour in various environments and institutions. One such organization is the Canadian Armed Forces (CAF), which has recently undertaken research and data collection in order to better understand the prevalence of unwanted sexualized behaviours and discrimination in the CAF (Burczycka 2019; Cotter 2019; Cotter 2016), following the publication of an external review in 2014 which found an overall sexualized culture that tends to be hostile towards women (Deschamps 2015). More recently, two articles specifically examined these behaviours among Canadian postsecondary students, and were the first of their kind to explore these types of behaviours and their impacts in the Canadian postsecondary context (Burczycka 2020a; Burczycka 2020b). Building on this research, this article aims to measure the prevalence of unwanted sexualized and discriminatory behaviours, sexual assault and related attitudes specifically among Canada’s military college student population.Note Note

The Royal Military College of Canada (RMC) in Kingston, Ontario, and the Royal Military College Saint Jean (RMC SJ) in Saint-Jean-sur-Richelieu, Quebec are postsecondary institutions that provide university-level education to students (Royal Military College of Canada 2019).Note Similar to other postsecondary institutions, the student population at these colleges consists of mostly 18 to 24-year olds, many of whom are often experiencing newfound independence and peer pressure (Turchick and Wilson 2010). However, unlike typical postsecondary institutions, Canadian military colleges (CMCs) are largely male-dominated. Studies have shown that women in traditionally male-dominated institutions and occupations are at a greater risk of experiencing sexual harassment and unwanted behaviours in these environments (Castro et al. 2015; Leblanc and Coulthard 2015; Vogt et al. 2007). Additionally, CMCs have a similar structure to the military workplace environment of the CAF, which tends to be dominated by values such as formality, rank, leadership, loyalty and comradery (Castro et al. 2015; Rosen et al. 2003). All CMC students live on campus and their daily routines are much more regimented than the routines of those who attend other postsecondary institutions in Canada. Furthermore, the curriculum of military college students includes military-related activities, and there tend to be significant power differentials between junior and senior students—with senior students often having formal roles or authority over junior ones.

Between 2018 and 2019, Statistics Canada developed and conducted the Survey on Individual Safety in the Postsecondary Student Population (SISPSP). The questions included in the survey aimed to measure the nature and prevalence of unwanted sexualized and discriminatory behaviours and sexual assault among students in Canadian postsecondary institutions. Information on students’ attitudes and beliefs was also collected. Students in CMCs were also included in the survey.

The SISPSP included questions on students’ experiences with 15 unwanted sexualized and discriminatory behaviours, including some that were explicitly defined as inappropriate or unwanted, such as unwanted physical contact, and others that may or may not have been perceived that way by those who witnessed or experienced them, such as sexual jokes (see Text box 1). Understanding the prevalence of these behaviours as well as students’ perceptions of them can provide a measure of the culture of sexual violence and disrespectful behaviours that exists in many postsecondary institutions. Research has shown that environments where these behaviours occur frequently can send the message that they are common and tolerated by those in authority (Sadler et al. 2018).

This Juristat article presents findings on the prevalence, characteristics and impacts of unwanted sexualized behaviours, sexual assault, discriminatory behaviours and feelings of safety among Canada’s military college student population in 2019. The experiences of those who were targeted by these behaviours are analyzed, including the context in which they occurred: where they happened, who was responsible and who was around when they took place. Additionally, the article provides an overview of reporting related to unwanted sexualized and discriminatory behaviours, specifically awareness of available services and support and opinions about relevant school policies related to these behaviours and sexual assault. CMC students’ perceptions of safety at school is also explored. Throughout the article, various comparisons are made between CMC students and the general postsecondary student population in order to gauge any gaps between the two different types of student populations.Note

Start of text box 1

Text box 1

Key terms

The 2019 Survey on Individual Safety in the Postsecondary Student Population (SISPSP) measured behaviours that occurred in the postsecondary school-related setting. Universities, colleges, CEGEPs and other postsecondary institutions were included.Note

The survey collected information on ten unwanted sexualized behaviours and five discriminatory behaviours that occurred in the postsecondary setting. In addition, the SISPSP measured four types of sexual assault.

| Theme | Categories | Questionnaire items | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unwanted sexualized behaviours | Inappropriate verbal or non-verbal communication | Sexual jokes | ||||||

| Unwanted sexual attention, such as whistles, calls, etc. | ||||||||

| Inappropriate sexual comments about body appearance | ||||||||

| Inappropriate discussion about sex life | ||||||||

| Sexually explicit materials | Displaying, showing or sending sexually explicit messages or materials online | |||||||

| Taking or posting inappropriate or sexually suggestive photos or videos of any student without consent | ||||||||

| Unwanted physical contact or suggested sexual relations | Indecent exposure or inappropriate display of body parts in a sexual manner | |||||||

| Repeated pressure from the same person for dates or sexual relationships | ||||||||

| Unwelcome physical contact or getting too close | ||||||||

| Someone being offered personal benefits for engaging in sexual activity or being mistreated for not engaging in sexual activity | ||||||||

| Discriminatory behaviours | Discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation, gender or gender identity | Suggestions that a man does not act like a man is supposed to act | ||||||

| Suggestions that a woman does not act like a woman is supposed to act | ||||||||

| Someone being insulted, mistreated, ignored or excluded because of their gender | ||||||||

| Comments that people are not good at or should be prevented from being in a particular program because of their gender | ||||||||

| Someone being insulted, mistreated, ignored or excluded because of their sexual orientation or assumed sexual orientation | ||||||||

| Someone being insulted, mistreated, ignored or excluded because they are, or are assumed to be, transgender | ||||||||

| Sexual assault | Sexual attack | Forcing or attempted forcing into any unwanted sexual activity, by threatening, holding down, or hurting in some way | ||||||

| Unwanted sexual touching | Touching against a person's will in any sexual way, including unwanted touching or grabbing, kissing or fondling | |||||||

| Sexual activity where unable to consent | Subjecting to a sexual activity to which a person was not able to consent, including being drugged, intoxicated, manipulated, or forced in ways other than physically | |||||||

| Sexual activity where unable to consent, after they consented to another form of sexual activity | E.g., unprotected sex when it was protected sex that they consented to | |||||||

| Source: Statistics Canada, Survey on Individual Safety in the Postsecondary Student Population. | ||||||||

For Canadian military college (CMC) students, the postsecondary school-related setting includes:

- On campus

- While travelling to or from school

- During an off-campus event organized or endorsed by the school, including official sporting events

- During unofficial activities or social events organized by students, instructors, professors, either on or off campus

- At employment at the school

- During on-the-job trainingNote

- Behaviours that occurred online where some or all of the people responsible were students, teachers or other people associated with the school

It excludes any behaviours that occurred during the Basic Military Officer Qualification (BMOQ).Note

Campus refers to the physical building or buildings in which classes, studies and activities take place, including, for example, residences, cafeterias, libraries and lecture halls, as well as adjacent outdoor spaces.

End of text box 1

Nearly 7 in 10 Canadian military college students witnessed or experienced unwanted sexualized behaviours in the past year

In 2019, 68% of Canadian military college (CMC) students witnessed or experienced at least one type of unwanted sexualized behaviour in the previous 12 months (Table 1).Note This represented over 1,200 CMC students. Women, who represented 21% of all CMC students, were more likely than men to indicate that they had witnessed or experienced each of these types of behaviours (79% versus 66%).Note A much higher proportion of women CMC students in particular, indicated that they had witnessed or experienced inappropriate discussions about their own or someone else’s sex life (57%) and inappropriate sexual comments about someone’s appearance or body (55%), compared with men (34% and 32%, respectively).

The most common type of unwanted sexualized behaviour witnessed or experienced by both men and women was sexual jokes: 63% of men and 77% of women CMC students indicated that they had witnessed or experienced this form of behaviour in the past 12 months.

Overall, these findings are similar to what was observed in the general postsecondary student population (Burczycka 2020b). However, a larger proportion of women CMC students (79%) than women students generally (73%) witnessed or experienced at least one unwanted sexualized behaviour. In particular, much higher proportions of women at CMCs witnessed or experienced inappropriate discussions about sex life (57%) or sexual jokes (77%), compared with women in the general student population (41% and 61%, respectively). In contrast, there was no significant difference in the proportion of men at CMCs who witnessed or experienced unwanted sexualized behaviour (66%) compared with men students generally (69%). When there were differences for specific behaviours, men in the general student population witnessed or experienced unwanted sexualized behaviours more often than men at CMCs (Burczycka 2020b).

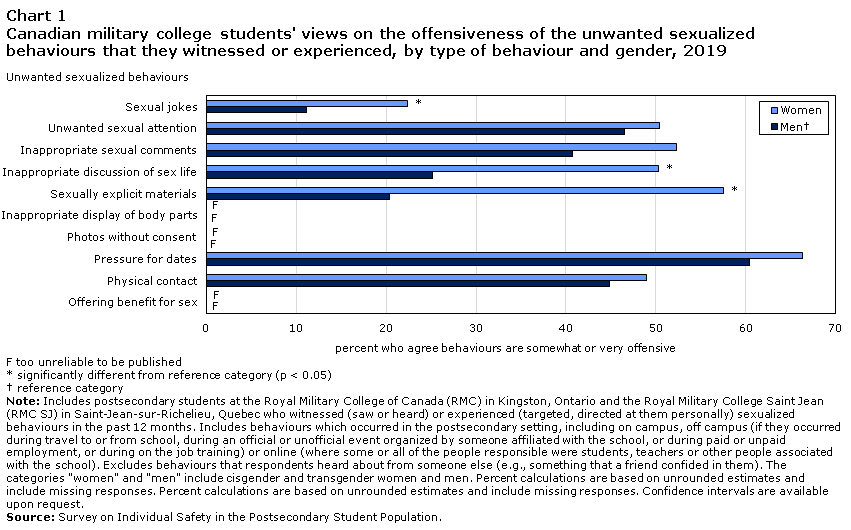

Women CMC students more likely to state that unwanted sexualized behaviours are offensive

Unwanted sexualized behaviours were generally viewed as offensive by both men and women Canadian military college students who witnessed or experienced them in the previous 12 months. However, women were more likely than men to find most types of behaviours offensive. When asked to rate different types of unwanted sexualized behaviours by offensiveness, the largest gender gap was observed for sexually explicit materials, which nearly three times as many women (58%) as men (20%) rated as somewhat or very offensive (Chart 1). Additionally, over twice the proportion of women as men CMC students viewed inappropriate discussions about sex life (50% versus 20%) as somewhat or very offensive. These findings are consistent with what was observed in the general student population, where women were more likely than men students to view each of the different types of unwanted sexualized behaviours as somewhat or very offensive (Burczycka 2020b).

Chart 1 start

Data table for Chart 1

| Unwanted sexualized behaviours | MenData table Note † | Women |

|---|---|---|

| percent who agree behaviours are somewhat or very offensive | ||

| Sexual jokes | 11 | 22Note * |

| Unwanted sexual attention | 47 | 50 |

| Inappropriate sexual comments | 41 | 52 |

| Inappropriate discussion of sex life | 25 | 50Note * |

| Sexually explicit materials | 20 | 58Note * |

| Inappropriate display of body parts | Note F: too unreliable to be published | Note F: too unreliable to be published |

| Photos without consent | Note F: too unreliable to be published | Note F: too unreliable to be published |

| Pressure for dates | 60 | 66 |

| Physical contact | 45 | 49 |

| Offering benefit for sex | Note F: too unreliable to be published | Note F: too unreliable to be published |

F too unreliable to be published

Source: Survey on Individual Safety in the Postsecondary Student Population. |

||

Chart 1 end

In terms of degree of offensiveness, CMC students indicated that the most offensive type of behaviour was repeated pressure for dates or a sexual relationship: 60% of men and 66% of women who witnessed or experienced it viewed it as somewhat or very offensive.

Compared with students in the general postsecondary student population, both men and women students at Canadian military colleges were less likely to view unwanted sexualized behaviours as somewhat or very offensive. For example, 41% of men and 52% of women CMC students viewed inappropriate sexual comments as somewhat or very offensive, compared with 54% of men and 78% of women general students.

The behaviours that occurred most frequently in a CMC postsecondary setting also tended to be the ones that were least often viewed by students as offensive. For instance, sexual jokes were viewed as not offensive or not very offensive for 9 in 10 (89%) men and nearly 8 in 10 (78%) women CMC students.

Women CMC students hold different attitudes and beliefs about unwanted sexualized behaviours than men

Women Canadian military college students tended to hold different attitudes than men in regards to unwanted sexualized behaviours. For example, nearly three times more men than women CMC students agreed or strongly agreed with the statement that “people get too offended by sexual comments, jokes or gestures” (45% versus 16%) (Chart 2). Similar findings were also observed in the general student population: 40% of men and 22% of women held this view (Burczycka 2020b). In addition, men CMC students were twice as likely as women CMC students to agree or strongly agree that “certain harmless behaviours are wrongly interpreted as sexual harassment” (33% of men versus 16% of women).

Chart 2 start

Data table for Chart 2

| Beliefs and attitudes | MenData table Note † | Women |

|---|---|---|

| percent who agree or strongly agree | ||

| People who report sexual assault are almost always telling the truth | 38 | 50Note * |

| It is always necessary to get consent before sexual activity regardless of whether you are in a relationship with that person or if you have just met | 87 | 93Note * |

| If one of your friends told you that they had experienced unwanted sexual contact, you would encourage them to report the incident to the military or civilian police | 82 | 84Note * |

| People get too offended by sexual comments, jokes or gestures | 45 | 16Note * |

| Certain harmless behaviours are wrongly interpreted as sexual harassment | 33 | 16Note * |

| Accusations of sexual assault are often used by one person as a way to get back at the other person | 22 | 9Note * |

| People who put themselves in risky situations are partially responsible for being sexually harassed or assaulted | 16 | Note F: too unreliable to be published |

| Often, what people say is sexual assault is actually consensual sex that they regretted afterwards | 17 | 8Note * |

| A person who is sexually assaulted while drunk is at least somewhat responsible for putting themselves in that position | 11 | Note F: too unreliable to be published |

| It doesn’t really hurt anyone to post sexual comments or photos of people without their consent | Note F: too unreliable to be published | Note F: too unreliable to be published |

F too unreliable to be published

Source: Survey on Individual Safety in the Postsecondary Student Population. |

||

Chart 2 end

Women CMC students were also more likely to agree with statements that were generally supportive of victims of unwanted sexualized behaviours. For instance, half (50%) of women agreed or strongly agreed with the statement that “people who report sexual assault are almost always telling the truth,” compared with less than two in five (38%) men. This particular finding was lower than what was observed among women in the general student population (60%), but not statistically different from men (40%).

The most common reason students do not intervene is because they did not think the incident was serious enough

Even though many Canadian military college students who witnessed or experienced unwanted sexualized behaviours in the postsecondary environment viewed them as offensive, the majority of students did not intervene when they witnessed these behaviours taking place. According to the SISPSP, 94% of men and 91% of women CMC students did not take action in at least one instance of witnessing unwanted sexualized behaviours in the CMC postsecondary setting (Table 2). Similar findings were also observed among students in the general student population (92% and 91%, respectively) (Burczycka 2020b).

The most common reason for both men and women CMC students to not intervene was that they did not think the situation was serious enough (85% and 65%, respectively). Another common reason cited by women was that they felt uncomfortable (31%), while 12% of men said the same. Additionally, 20% of women and 13% of men CMC students were worried that taking action would affect their peer relationships.

Overall, women CMC students (74%) were more likely than men (57%) to indicate that they did intervene in at least one instance of witnessing unwanted sexualized behaviours. For both women and men CMC students, this was a much higher proportion than what was observed in the general student population where 55% of women and 41% of men intervened in at least one instance of witnessing unwanted sexualized behaviours (Burczycka 2020b). Equal proportions of men and women CMC students who took action indicated that they spoke to the person(s) responsible for the behaviour (85%)—which was the most common type of intervention. The next most common type of intervention for both men and women was speaking to the person who was targeted by the behaviour, an action taken by 51% of men and 47% of women.

Nearly one-third of men and more than half of women personally experienced an unwanted sexualized behaviour at a Canadian military college in the past 12 months

According to the 2019 SISPSP, nearly one-third (31%) of men Canadian military college students and over one-half (52%) of women personally experienced at least one type of unwanted sexualized behaviour in the postsecondary setting in the previous 12 months (Table 3). For both men and women, the prevalence of unwanted sexualized behaviours was not statistically different from what was observed among the general postsecondary student population (Burczycka 2020b).

Overall, the most commonly experienced unwanted sexualized behaviour was sexual jokes, personally experienced by 28% of men and 40% of women CMC students in the previous 12 months. For women CMC students, the next most frequent behaviour experienced was inappropriate sexual comments about someone’s appearance or body (25%), while for men, it was inappropriate discussions about their or someone else’s sex life (14%). Similar findings were also observed among men in the general student population. However, for women in the general student population, unwanted sexual attention such as whistles or “catcalls” (27%) were equally as common as sexual jokes (27%). Notably, sexual jokes (27%) were less common among women students generally than among women in Canadian military colleges (40%) (Burczycka 2020b).

Women were more likely than men CMC students to have personally experienced most of the ten types of unwanted sexualized behaviours captured by the survey.Note A particularly large difference in experiences was observed for unwanted sexual attention such as whistles or “catcalls,” which women CMC students were six times (24%) more likely to experience than men (4%). The higher prevalence of this behaviour among women CMC students reflects what was also observed across genders in the general student population (27% of women versus 6% of men) (Burczycka 2020b), as well as findings among the general population and in the Canadian Armed Forces (Burczycka 2019; Cotter 2019; Cotter and Savage 2019).

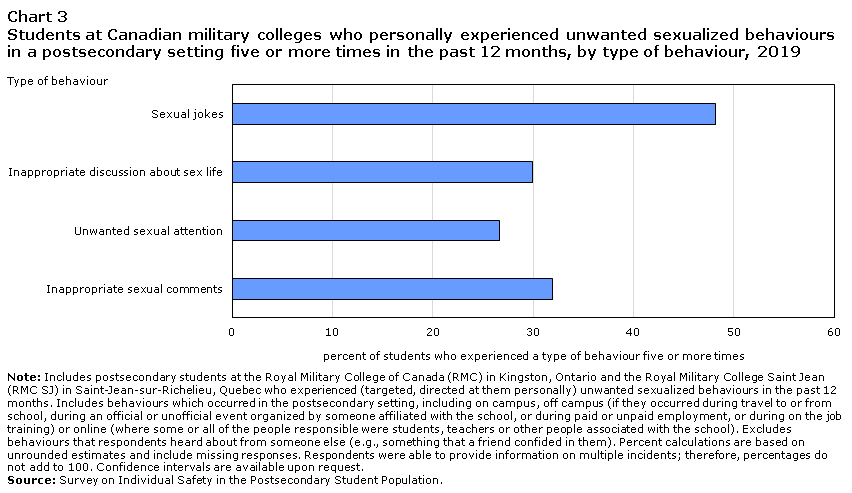

Many students who personally experienced unwanted sexualized behaviours indicated that they experienced them on more than one occasion. According to the SISPSP, 48% of the CMC students who experienced sexual jokes reported that the behaviour happened five or more times (Chart 3). Additionally, about three in ten of the students who experienced inappropriate sexual comments (32%) and inappropriate discussions about theirs or someone else’s sex life (30%) said that they experienced the behaviour five or more times. In comparison, 34% of students in the general student population who experienced sexual jokes said they occurred five or more times (Burczycka 2020b).

Chart 3 start

Data table for Chart 3

| Type of behaviours | Percent of students who experienced a type of behaviour five or more times |

|---|---|

| Sexual jokes | 48 |

| Inappropriate discussion about sex life | 30 |

| Unwanted sexual attention | 27 |

| Inappropriate sexual comments | 32 |

|

Note: Includes postsecondary students at the Royal Military College of Canada (RMC) in Kingston, Ontario and the Royal Military College Saint Jean (RMC SJ) in Saint-Jean-sur-Richelieu, Quebec who experienced (targeted, directed at them personally) unwanted sexualized behaviours in the past 12 months. Includes behaviours which occurred in the postsecondary setting, including on campus, off campus (if they occurred during travel to or from school, during an official or unofficial event organized by someone affiliated with the school, or during paid or unpaid employment, or during on the job training) or online (where some or all of the people responsible were students, teachers or other people associated with the school). Excludes behaviours that respondents heard about from someone else (e.g., something that a friend confided in them). Percent calculations are based on unrounded estimates and include missing responses. Respondents were able to provide information on multiple incidents; therefore, percentages do not add to 100. Confidence intervals are available upon request. Source: Survey on Individual Safety in the Postsecondary Student Population. |

|

Chart 3 end

Nearly three in ten women sexually assaulted during their time at a Canadian military college

Canadian military college students were also asked about their experiences of sexual assault in the postsecondary setting during their time as students at RMC or RMC SJ. For the purposes of the SISPSP, sexual assault includes sexual attacks, sexual touching, sexual activity where a person is unable to consent, or sexual activity where a person is unable to consent, after having consented to another form of sexual activity (see Text box 1).

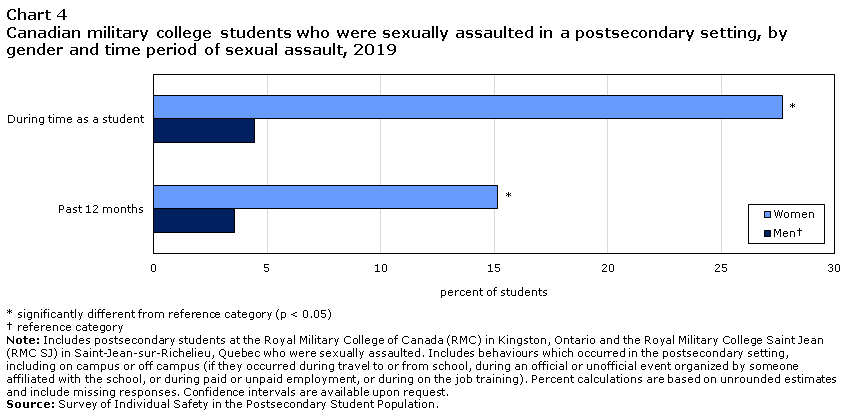

According to the SISPSP, more than six times as many women (28%) as men (4.4%) CMC students experienced some form of sexual assault during their time as students (Chart 4). For women in particular, this finding was much higher than what was observed among women in the general student population (15%), while the results for men were similar (5%) (Burczycka 2020b). Sexual touching was the most common form of sexual assault experienced by both women and men CMC students (22% and 3.9%, respectively). Many women indicated that they experienced sexual activity to which they were unable to consent because they were drugged, intoxicated, manipulated or forced in other non-physical ways (13%).Note Additionally, 11% of women CMC students indicated that they experienced sexual attacks—the most serious form of sexual assault.

Chart 4 start

Data table for Chart 4

| During time as a student | Past 12 months | |

|---|---|---|

| percent of students | ||

| Women | 28Note * | 15Note * |

| MenData table Note † | 4 | 4 |

Source: Survey of Individual Safety in the Postsecondary Student Population. |

||

Chart 4 end

These patterns were also seen among those in the general student population. For both women (13%) and men (4%) in the general student population, sexual touching was also the most common form of sexual assault that was experienced during their time at school. Similarly, sexual activity to which they were unable to consent or sexual attacks were less frequent, experienced by 4% and 3% of women students, respectively.

One in seven women CMC students sexually assaulted in the past 12 months

Canadian military college students were also asked about their experiences of sexual assault in the past 12 months.Note Overall, 15% of women CMC students indicated that they had been sexually assaulted in the postsecondary environment during the previous 12 months, a proportion more than four times higher than men (3.6%). Again, sexual touching was the most common form of sexual assault experienced by both women and men CMC students in the past year (14% and 3.3%, respectively).Note

The prevalence of sexual assault among those in the general postsecondary student population was not statistically different for women (11%) or men (4%) when compared to students in CMCs (Burczycka 2020b). When looking at a similar age range to those in the CMC, these findings are also consistent with what was observed among Regular Force members of the CAF: 15% of women and 3% of men under the age of 24 were sexually assaulted in the 12 months prior to the SSMCAF (Cotter 2019), as well as the general population, based on results from the Survey of Safety in Public and Private Spaces (SSPPS) (Cotter and Savage 2019).

Many unwanted sexualized behaviours take place in the presence of others

In many instances, Canadian military college students indicated that a single perpetrator was responsible for the unwanted sexualized behaviours that they experienced (23% of men and 28% of women) (Table 4). Most commonly, CMC students stated that the number of persons responsible varied per incident (36% of men and 41% of women).

Most CMC students indicated that other people, aside from the perpetrator, were around when the incident took place. The majority of the time (88%), other people were present when students experienced unwanted sexualized behaviours. However, this proportion varied depending on the type of unwanted sexualized behaviour that occurred. For instance, under half (45%) of the Canadian military college students who experienced a behaviour related to sexually explicit materials indicated that various people were around when the incident took place, compared with 87% of those who experienced inappropriate verbal or non-verbal communication. These findings suggest that many incidents of unwanted sexualized behaviours occur in group settings, but that this tends to vary depending on the type and severity of behaviour. Results were also similar in the general student population. According to the survey, 74% of the general students who experienced inappropriate verbal or non-verbal communication indicated that others were present when the incident took place, compared with 40% of students who experienced behaviours related to sexually explicit materials (Burczycka 2020b).

According to the SISPSP, 40% of the Canadian military college students who experienced unwanted sexualized behaviours when others were present indicated that other people took action during the situation. This proportion was not statistically different from what was observed among those in the general postsecondary student population (36%).

According to those who were targeted, the most common type of intervention taken by others at CMCs was confronting the perpetrator responsible for the behaviour (53%), which was closely followed by creating a distraction to try to stop the behaviour (46%). These proportions were consistent with what was observed for those in the general student population (56% and 46%) (Burczycka 2020b). Speaking to the person responsible was also the most commonly reported action among both men and women CMC students who said that they intervened when witnessing unwanted sexualized behaviours.

In contrast to these types of intervention, one in six (16%) CMC students indicated that the other people who were around actually took action by encouraging the unwanted sexualized behaviour.

Most unwanted sexualized behaviours occur on campus

Most Canadian military college students who experienced unwanted sexualized behaviours in the postsecondary setting in the previous 12 months indicated that they occurred on their CMC campus (93%)—where CMC students often spend the majority of their time—while smaller proportions experienced these behaviours off campus (44%) or online (21%) (Table 5).Note Generally, equal proportions of men and women experienced these behaviours on campus and online. However, there was a difference when it came to behaviours experienced off campus. According to the survey, just under half (49%) of men CMC students and about one-third (32%) of women students experienced these unwanted sexualized behaviours off campus.

All of the types of unwanted sexualized behaviours were also more likely to occur in public spaces or common areas, where there is often a greater chance that there will be other people present. For example, 84% of the Canadian military college students who experienced unwanted sexualized behaviours off campus indicated that they occurred at an off-campus bar or restaurant, while 78% of those who experienced them on campus indicated that they happened in an on-campus residence. Additionally, a large proportion of unwanted sexualized behaviours on campus occurred in a non-residential building (such as a library, cafeteria or gym) (54%), while most behaviours that occurred online happened on social media (85%). Similar findings were also observed among students in the general student population. For instance, 79% of general postsecondary students who indicated that they experienced unwanted sexualized behaviours online said it occurred on social media, while 61% who experienced sexualized behaviours on campus experienced them in a non-residential building.

Unwanted sexualized behaviours generally committed by fellow students

Other Canadian military college students were most frequently responsible for committing unwanted sexualized behaviours against fellow students (94%) (Table 4). Similarly, most students (82%) in the general student population also indicated that a fellow student at their school was responsible for the unwanted sexualized behaviours that they experienced (Burczycka 2020b).

More than half (53%) of the CMC students who experienced unwanted sexualized behaviours in the previous 12 months indicated that it was a friend or an acquaintance who was responsible. These proportions were similar for both men and women who were targeted. Notably, 18% of women CMC students reported that a stranger was responsible for the unwanted sexualized behaviour that they experienced.Note

Less commonly, students indicated that the person(s) responsible for the unwanted sexualized behaviours were individuals such as a member of a club or team to which they belonged (7%) or others associated with the school such as staff members or security staff (8%). Relatively few students in the general population also indicated that a person in authority such as a coach or professor committed the unwanted sexualized behaviours that they experienced (Burcycka 2020b).

Men more likely than women to be responsible for committing unwanted sexualized behaviours against CMC students

Just over four in ten (44%) of the Canadian military college students who experienced unwanted sexualized behaviours in the past 12 months indicated that the person(s) responsible for the behaviours was a man or multiple men (Table 4). In addition, 45% of students indicated that the gender(s) of the perpetrator(s) varied across instances or behaviours— but included both men and women.

Even though the gender composition of students at Canadian military colleges tends to be much different than the composition at most other universities and colleges—where there tends to be a more equal distribution of men and women among the student population—many students in the general student population also indicated that those responsible for the unwanted sexualized behaviours that they experienced were men, ranging from 55% of students who experienced inappropriate communication to 69% of those who experienced unwanted physical contact or suggested sexual relations (Burczycka 2020b).

Women more likely than men to experience emotional impacts as a result of unwanted sexualized behaviours

Unwanted sexualized behaviours can have a wide range of impacts on those who experience them, which can often vary depending on an individual’s interpretation of the behaviour, as well as the type and seriousness of the behaviour. For example, sexual jokes can be viewed as offensive by some individuals and in certain contexts, while others may view them as more widely acceptable. As a result, the impact of these kinds of behaviours on those who experience them is largely subjective.

According to the SISPSP, half (50%) of the Canadian military college students who personally experienced unwanted sexualized behaviours in the postsecondary setting in the past 12 months did not report experiencing any emotional impact as a result of the behaviours, and over one-third (35%) indicated that they did not experience much impact (Table 6). In contrast, a smaller proportion (27%) of students in the general population who personally experienced unwanted sexualized behaviour said they did not experience any negative emotional impact. About three in ten (29%) CMC students stated that they felt annoyed by the unwanted sexualized behaviours that they experienced, while a smaller proportion of students said that they were cautious (15%), confused (15%), frustrated (15%) or angry (15%).

The emotional impacts of unwanted sexualized behaviours tended to vary between men and women. For example, just under one in five (19%) women CMC students indicated that they experienced no emotional impact at all, while nearly two-thirds (63%) of men said the same. Women CMC students who personally experienced unwanted sexualized behaviours commonly indicated that they felt annoyed (40%), frustrated (34%), angry (29%) or more cautious or aware (29%).Note Women in the general postsecondary student population were also more likely to indicate that they felt fearful for their safety, or that they experienced impacts related to negative mental health (Burczycka 2020b).

Overall, most CMC students indicated that the unwanted sexualized behaviours that they experienced had very little impact on their schooling and academic life. Small proportions of students indicated that they avoided specific buildings because of the behaviours they experienced (9%), or asked for extensions on school work (5%). Furthermore, 6% indicated that they received help from a mental health professional.

CMC students who experience unwanted sexualized behaviours rarely speak to someone associated with the school about the incident

Four in ten (40%) Canadian military college students who personally experienced at least one instance of unwanted sexualized behaviour in the previous 12 months spoke about their experiences with someone not associated with the school, most commonly a friend (82%) or a family member (48%) (Table 7). Women CMC students were also more likely than men overall to indicate that they spoke about their experiences to someone not associated with the school (76% compared with 24%). In comparison, fewer than one in ten (7%) students sought help from someone associated with the school (e.g., campus security, school employee, instructor, etc.). Similar findings were also observed in the general student population, as 7% of students in the general student population spoke to someone associated with the school about their experiences (Burczycka 2020b).

CMC students commonly indicated that they did not speak to someone associated with the school about the behaviour that they experienced because they did not think the situation was serious enough (56%), they did not need help (43%) or because they resolved the issue on their own (40%). A smaller proportion of students said that their reason for not speaking to someone associated with the school was because they did not know where to go to get help at school, who could provide help, or if the incident could be reported (7%).

Students who experience unwanted sexualized behaviours are less likely to have positive opinions about student resources available to help them

Canadian military college students were also asked about their attitudes and awareness in regards to CMC resources related to sexual assault and harassment. Overall, most men (85%) and women (70%) CMC students were aware of CMC procedures for dealing with reported incidents of harassment and sexual assault. This was well above the proportions of men (40%) and women (31%) in the general student population who indicated the same (Burczycka 2020b).

CMC students who personally experienced unwanted sexualized behaviours were often more aware of their school policies related to these behaviours: 9 in 10 (90%) students who experienced at least one form of unwanted sexualized behaviour were aware of the school’s confidential resources for harassment and sexual assault and how to locate them, compared with 8 in 10 (80%) students who did not experience the behaviours (Table 8).Note However, CMC students who were sexually assaulted were often less aware of school policies. Just over two-in-three (68%) students who were sexually assaulted in the previous 12 months said they knew where to get help at school if a friend was harassed or sexually assaulted, compared with 8 in 10 (81%) students who were not sexually assaulted. These findings suggest that many CMC students believe they know where to get help at school if they experience an unwanted sexualized behaviour or sexual assault, but after they experience these types of incidents that they realize this was not the case.

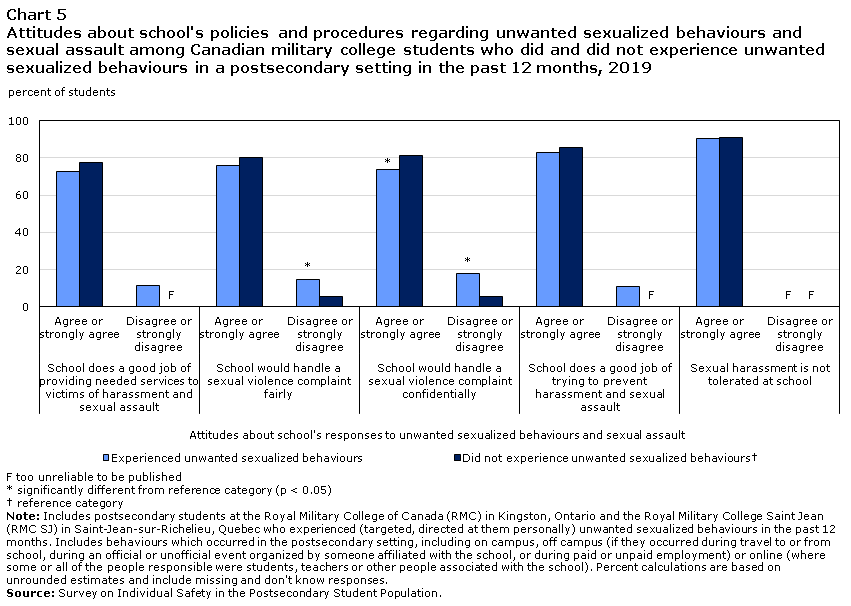

Additionally, women CMC students and those who experienced unwanted sexualized behaviours often held more negative attitudes regarding school-related support and services than men and students who did not experience the behaviours, findings which were also observed among the general student population (Burczycka 2020b). Among CMC students who experienced unwanted sexualized behaviours in the past 12 months, 15% disagreed or strongly disagreed with the statement that “the school would handle a sexual violence complaint fairly”, while 6% of students who did not experience these behaviours said the same (Chart 5).

Chart 5 start

Data table for Chart 5

| Attitudes about school's responses to unwanted sexualized behaviours and sexual assault |

School does a good job of providing needed services to victims of harassment and sexual assault | School would handle a sexual violence complaint fairly | School would handle a sexual violence complaint confidentially | School does a good job of trying to prevent harassment and sexual assault | Sexual harassment is not tolerated at school | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agree or strongly agree | Disagree or strongly disagree | Agree or strongly agree | Disagree or strongly disagree | Agree or strongly agree | Disagree or strongly disagree | Agree or strongly agree | Disagree or strongly disagree | Agree or strongly agree | Disagree or strongly disagree | |

| Experienced unwanted sexualized behaviours | 73 | 12 | 76 | 15 | 74 | 18 | 83 | 11 | 91 | Note F: too unreliable to be published |

| Did not experience unwanted sexualized behavioursData table Note † | 77 | Note F: too unreliable to be published | 80 | 6Note * | 82Note * | 6Note * | 85 | Note F: too unreliable to be published | 91 | Note F: too unreliable to be published |

F too unreliable to be published

Source: Survey on Individual Safety in the Postsecondary Student Population. |

||||||||||

Chart 5 end

These differences in opinions were also more pronounced for those who were sexually assaulted. For example, close to half (48%) of the CMC students who were sexually assaulted during the previous 12 months disagreed or strongly disagreed with the statement that “the school would handle a sexual violence complaint confidentially”, compared with 7% of students who were not sexual assaulted (Chart 6). Furthermore, 52% of students who were sexually assaulted agreed that their “school does a good job of providing needed services to victims of harassment and sexual assault”, compared with 77% of students who were not sexually assaulted. These findings all suggest that the seriousness of a CMC students’ personal experience with an unwanted sexualized behaviour or sexual assault in a postsecondary setting may be associated with their confidence in their school’s policies and programs to prevent or handle these incidents.

Chart 6 start

Data table for Chart 6

| Attitudes about school's responses to unwanted sexualized behaviours and sexual assault |

School does a good job of providing needed services to victims of harassment and sexual assault | School would handle a sexual violence complaint fairly | School would handle a sexual violence complaint confidentially | School does a good job of trying to prevent harassment and sexual assault | Sexual harassment is not tolerated at school | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agree or strongly agree | Disagree or strongly disagree | Agree or strongly agree | Disagree or strongly disagree | Agree or strongly agree | Disagree or strongly disagree | Agree or strongly agree | Disagree or strongly disagree | Agree or strongly agree | Disagree or strongly disagree | |

| Victim of sexual assault | 52 | Note F: too unreliable to be published | 61 | 36 | 42 | 48 | 71 | Note F: too unreliable to be published | 83 | Note F: too unreliable to be published |

| Not a victim of sexual assaultData table Note † | 77Note * | 4 | 80Note * | 7Note * | 82Note * | 7Note * | 86Note * | 5 | 92 | 2 |

F too unreliable to be published

Source: Survey on Individual Safety in the Postsecondary Student Population. |

||||||||||

Chart 6 end

In contrast, the vast majority of Canadian military college students agreed or strongly agreed with the statement that “sexual harassment is not tolerated at school” (83% of students who were sexually assaulted, and 92% of students who were not sexually assaulted).

Women CMC students more likely than men to witness or experience discrimination

Canadian military college students were also asked about their experiences of discrimination—another form of unwanted behaviour which can have widespread impacts on those who witness or experience it. Specifically, the SISPSP asked students about five types of discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation, gender and gender identity that occurred in the postsecondary context.

According to the survey, two in five (40%) Canadian military college students (representing over 700 students) witnessed or experienced some form of discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation, gender or gender identity in the previous 12 months (Table 1). The most common form of discrimination was suggestions that a man does not act like a man is supposed to act—witnessed or experienced by 30% of men and 39% of women CMC students. Similar to the findings related to unwanted sexualized behaviours, women CMC students were more likely than men to witness or experience each of the five types of discriminatory behaviours. In particular, a much higher proportion of women than men CMC students witnessed or experienced comments that people are not good at or should be prevented from being in a particular program because of their gender (33% of women versus 5% of men). In the general student population this form of discrimination was witnessed or experienced by much higher proportions of men (15%), but a similar proportion of women (28%). More specifically, findings from the general student population found that women in male-dominated programs of study were more likely to experience this type of discriminatory behaviour (Burczycka 2020a).Note

Most CMC students viewed discriminatory behaviours as somewhat or very offensive. However, compared with men, women CMC students were generally more likely than men to view discrimination as offensive, regardless of whether the discrimination pertained to their gender or not. For example, higher proportions of women (59%) than men (40%) viewed suggestions that a woman does not act like woman is supposed to act as somewhat or very offensive, just as more women than men thought that suggestions that a man does not act like a man is supposed to act was somewhat or very offensive (57% versus 34%).

More than three-quarters of students did not take action when witnessing discrimination

Women Canadian military college students were more likely than men to intervene in at least one instance of witnessing discrimination in the postsecondary setting (67% versus 49%) (Table 2). Similarly, women in the general student population were also more likely than men to take some sort of action when they witnessed discriminatory behaviours take place (55% of women versus 41% of men) (Burczycka 2020a). The most common type of intervention for both men and women CMC students was speaking to the person(s) responsible for the discriminatory behaviour (92% of men and 83% of women who intervened in some way). Many students who intervened in at least one instance spoke to the person who was targeted by the behaviour (43% of men and 46% of women). Similar proportions of both men and women CMC students indicated that they created a distraction to stop the situation (22% of men and 26% of women).

More than three-quarters of students who witnessed discrimination in the CMC postsecondary setting did not take action in at least one instance (77% for both men and women). Similar to unwanted sexualized behaviours, the most common reason for not intervening was the belief that the behaviour was not serious enough – particularly for men (68%) compared to women (40%). Many men in the general student population also did not intervene because they did not think the situation was serious enough to warrant intervention (66%), while a smaller proportion of women said the same (50%) (Burczycka 2020a). Many CMC students – women in particular - indicated that they did not intervene because they felt uncomfortable (19% of men and 39% of women).

Women Canadian military college students more likely than men to experience most types of discrimination

According to the SISPSP, around one in eight men (13%) and one in three women (33%) Canadian military college students personally experienced some form of discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation, gender or gender identity in the postsecondary setting in the previous 12 months (Table 3). For women CMC students, this was a much higher proportion than what was observed among women in the general postsecondary student population (20%) (Burczycka 2020a).

The most common form of discrimination personally experienced by both men and women CMC students was suggestions that they do not act like a man or woman is supposed to act (12% of men and 23% of women). Women were also more likely than men to have personally experienced most of the types of discrimination captured by the survey.

Bystanders commonly present for discriminatory behaviours, but often do not take action

More than one-third (37%) of the Canadian military college students who personally experienced discriminatory behaviours in the postsecondary setting said that a single person was responsible for the behaviour(s) (Table 4). Three in ten (30%) CMC students said that the number of perpetrators varied between experiences, while 22% indicated that two or more persons were responsible. Similar findings were also observed among those in the general student population. According to the SISPSP, 38% of students in the general student population indicated that a single person committed the discriminatory behaviour that they experienced (Burczycka 2020a).

Three-quarters of CMC students (75%) said that other people were around when the discriminatory incident took place. However, these witnesses did not take action most of the time—83% of the CMC students who experienced discrimination while others were present indicated that they experienced at least one instance where the other people did not take action.

Most discriminatory behaviours occur on campus

Canadian military college students most often experienced discriminatory behaviours on campus (86%), while a much smaller proportion of students indicated that they experienced discriminatory behaviours off campus (27%) (Table 5).Note Note Similarly, more than seven in ten (72%) students in the general student population experienced discriminatory behaviours on campus (Burczycka 2020a). Just over half of the CMC students who experienced discriminatory behaviours on campus indicated that these events occurred in a non-residential building (such as a library, cafeteria or gym) (57%) or at an on-campus residence (54%)—areas which are often open environments with other people around. Further, over one-third (37%) of CMC students experienced these behaviours in a learning environment.

Fellow CMC students often responsible for committing discriminatory behaviours

The majority of Canadian military college students who experienced discriminatory behaviours in a postsecondary setting in the previous 12 months identified a fellow student at their school as the person responsible for the incident (86%) (Table 4). Most students in the general student population also indicated that a fellow student committed the discriminatory behaviour that they experienced (72%). Furthermore, 37% of CMC students said that it was a friend or an acquaintance who committed the behaviour.

More than half (56%) of the CMC students who experienced discriminatory behaviours indicated that a single man or multiple men were responsible for the discriminatory behaviour that they experienced. The proportion of CMC students who identified their perpetrator(s) as a man or men was not statistically different between women (60%) and men (51%). About three in ten (32%) CMC students indicated that the discriminatory behaviours that they experienced were sometimes committed by men and sometimes by women.Note

More CMC students experience emotional impacts from discriminatory behaviours than from sexualized behaviours

According to the SISPSP, around half of the students who experienced at least one discriminatory behaviour in the past 12 months did not experience much (24%) or any (21%) emotional impact as a result of the behaviours (Table 6). In contrast, more than four in five CMC students who experienced sexualized behaviours said they had not much (35%) or no (50%) impact. CMC students commonly indicated that they felt annoyed by the discriminatory behaviours that they experienced (37%).

In comparison, 17% of students in the general student population who experienced discrimination said it had no emotional impact, while 19% said it did not have much of an emotional impact. The most common emotional impact that general students had as a result of these behaviours was feeling annoyed (51%) (Burczycka 2020a).

Overall, women CMC students were more likely than men CMC students to experience an emotional impact from discriminatory behaviours. In particular, as a result of the discriminatory behaviours, 42% of women felt angry, while 31% of women felt upset. In comparison, men were less likely to experience an emotional impact: 32% of men CMC students experienced not much emotional impact at all.Note Men commonly indicated that they were annoyed (25%) by the discriminatory behaviours that they experienced.

Additionally, relatively small proportions of students experienced impacts on their relationships with others, such as friends, roommates or peers (16%).

Most students do not speak to someone from the school about the discriminatory behaviours they experience

Nine in ten (88%) Canadian military college students who experienced discriminatory behaviours at RMC or RMC SJ did not speak about the situation with someone associated with the school (Table 7). Both men and women CMC students commonly indicated that the situation was not serious enough to speak to someone associated with the school (68% of both men and women). Similar proportions of CMC students indicated that they did not speak to someone from the school because they did not need help (56% of men and 59% of women), while some students said that they resolved the issue on their own (29% of men, 31% of women). On the other hand, 40% of Canadian military college students spoke about the discriminatory behaviours they experienced with a friend or family member.

Similarly, most students in the general student population also did not speak to someone from the school about the discriminatory behaviours that they experienced (92%). Most commonly, both men (65%) and women (65%) general students stated that they did not speak to anyone at the school because the situation was not serious enough (Burczycka 2020a).

Non-heterosexual CMC students and those with a disability more likely to be targets of unwanted sexualized or discriminatory behaviours

Similar to what was observed in the general postsecondary student population (Burczycka 2020a; Burczycka 2020b), as well as other research on the general population (Cotter and Savage 2019), Canadian military college students with certain characteristics tended to experience unwanted sexualized or discriminatory behaviours more often than those who did not possess those characteristics. For example, close to half (46%) of CMC students who had a disability experienced some form of unwanted sexualized behaviour in the previous 12 months, compared with 32% of students who did not have a disability (Table 9).Note The SISPSP also found that CMC students with a disability were more likely to experience discrimination, compared with those without a disability (28% versus 14%). All of these findings are consistent with what was observed among Regular Force members of the CAF (Cotter 2019).

Non-heterosexual CMC students also experienced a higher prevalence of unwanted sexualized or discriminatory behaviours (62% and 50%, respectively) than heterosexual students (33% and 15%, respectively).Note

The number of years CMC students had been enrolled had somewhat of an impact on the prevalence of unwanted sexualized and discriminatory behaviours. While four in ten CMC students who had less than one year (41%), one or two years (40%), or three or four years (40%) at school had personally experienced unwanted sexualized behaviours in the past 12 months, about half as many (22%) with five or more years indicated the same. The number of years of school did not make a significant difference in terms of the prevalence of discriminatory behaviours.

Most Canadian military college students feel safe on and around campus

Canadian military college students were also asked about their feelings of safety on and around their school campus. These feelings can often provide an indication of how a person experiences certain environments around them. Since CMC students spend the majority of their time on campus, findings from this portion of the SISPSP are particularly important.

According to the survey, in general, CMC students felt fairly safe in various school-related settings. For instance, 94% of men and 84% of women students felt safe on their CMC campus (Chart 7). Similar findings were also observed among the general student population (92% of men and 86% of women) (Burczycka 2020a). However, women tended to feel less safe than men overall for all safety scenarios captured by the survey. For example, 94% of men and 78% of women CMC students felt safe while walking alone on campus after dark. Additionally, a much lower proportion of women CMC students indicated that they felt safe using public transportation alone after dark (52% of women versus 87% of men). Women (83%) were also less likely than men (91%) to indicate that they agreed or strongly agreed with the statement that their “school tries hard to ensure student safety”. Previous research has shown that overall, women tend to rate their self-perceived safety lower than men (Perreault 2017).

Chart 7 start

Data table for Chart 7

| Feelings of safety | MenData table Note † | Women |

|---|---|---|

| percent who agree or strongly agree | ||

| School tries hard to ensure student safety | 91 | 83Note * |

| Feel safe on school campus | 94 | 84Note * |

| Feel safe at home alone after dark | 95 | 87Note * |

| Feel safe and not fearful of who they are or are perceived to be | 91 | 77Note * |

| Feel safe walking alone on campus after dark | 94 | 78Note * |

| Feel safe using public transportation alone after dark | 87 | 52Note * |

Source: Survey on Individual Safety in the Postsecondary Student Population. |

||

Chart 7 end

CMC students who personally experienced unwanted sexualized behaviours or sexual assault were also less likely to feel safe, when compared with students who did not experience these behaviours. Specifically, those who had been sexually assaulted during the previous 12 months were much less likely to feel safe, compared with those who were not sexually assaulted (Table 10). For example, 70% of students who were sexually assaulted agreed or strongly agreed with the statement that “they feel safe and not fearful of who they are or are perceived to be”, compared with 91% of students who were not sexually assaulted. Notably, 57% of students who were sexually assaulted stated that they felt safe using public transportation alone after dark, considerably lower than the 83% who had not been sexually assaulted. These proportions are similar to what was observed among women (52%) and men (87%) in the CMC , which may be related to the fact that women are more likely than men to have been victims of sexual assault, both in the CMC context and in general. Notably, in the general student population, a lower proportion of students felt safe using public transportation alone after dark, both among those who had been sexually assaulted (38%) and those who had not (59%).

Summary

Between 2018 and 2019, the Survey on Individual Safety in the Postsecondary Student Population (SISPSP) was conducted in order to measure the nature and prevalence of unwanted sexualized and discriminatory behaviours and sexual assault among students in Canadian postsecondary institutions, as well as those at Canadian military colleges.

In 2019, 68% of Canadian military college students witnessed or experienced unwanted sexualized behaviours in the postsecondary setting. The most common types of behaviours that were witnessed or experienced by CMC students were sexual jokes, inappropriate discussions about sex life and inappropriate sexual comments about appearance or body.

Women CMC students experienced all of the unwanted sexualized behaviours captured by the survey more often than men (52% versus 31%). Additionally, women CMC students were more likely to consider unwanted sexualized behaviours as offensive and to disagree with statements that minimized the potential harm of these behaviours. In comparison, men CMC students were more likely to view these types of behaviours—especially sexual jokes—as not offensive in the postsecondary setting.

Four in ten (40%) CMC students witnessed discriminatory behaviours at their Canadian military college—while 17% experienced them personally. Similarly, women were more likely than men to have been personally targeted by most types of discriminatory behaviours (33% and 13%, respectively). Overall, the most common form of discrimination at CMCs was suggestions that a man or woman does not act like they are supposed to act.

Nearly one in three (28%) women and fewer than one in twenty (4.4%) men Canadian military college students were sexually assaulted during their time at the Royal Military College of Canada or the Royal Military College Saint Jean. Additionally, 15% of women and 3.6% of men reported being sexually assaulted in the previous 12 months in a postsecondary school-related setting. Sexual touching was the most common form of sexual assault experienced by CMC students.

Many CMC students who witnessed unwanted sexualized or discriminatory behaviours in the postsecondary setting did not intervene to assist those who experienced them, often because they did not view the situation as serious enough.

CMC students who personally experienced unwanted sexualized or discriminatory behaviours frequently identified fellow students as the perpetrators, while smaller proportions identified friends or acquaintances, or strangers. Most of the time, unwanted sexualized or discriminatory behaviours occurred on campus, with others present—in public areas that tend to be open and could be filled with lots of people. Additionally, many CMC students indicated that these behaviours occurred at an off-campus restaurant or bar.

Some CMC students experienced negative emotional and mental health impacts because of the unwanted sexualized or discriminatory behaviours, though few indicated that their schooling or their relationships with others (e.g., friends, roommates or peers) were impacted. Women were more likely than men to indicate that they experienced these types of impacts.

Canadian military college students who experienced unwanted sexualized or discriminatory behaviours in the postsecondary setting rarely spoke to someone at their school regarding the behaviours that they experienced, but they were often aware of school resources available to assist them. Generally, women and CMC students who experienced these behaviours were less likely to hold positive opinions about the resources available to assist them than men and students who did not experience them.

Overall, most Canadian military college students indicated that they felt safe on and around their military college campuses. However, women students and those who experienced unwanted sexualized behaviours or sexual assault were less likely to feel safe.

Detailed data tables

Survey description

In 2019, Statistics Canada conducted the first cycle of the Survey on Individual Safety in the Postsecondary Student Population (SISPSP). The survey was developed in collaboration with various stakeholders, including academics, student groups, and others. The purpose of the survey is to collect information on the nature, extent and impact of inappropriate sexual and discriminatory behaviours and sexual assaults that occur in the postsecondary school-related setting in the Canadian provinces. Information on students’ knowledge and perceptions of school policies related to these issues is also collected. The survey was funded by the Department for Women and Gender Equality (WAGE) as part of It’s Time: Canada’s Strategy to Prevent and Address Gender-Based Violence.

The target population for the survey are students who attended the Royal Military College of Canada (RMC) or the Royal Military College Saint Jean (RMC SJ) in the fall of 2018. All full-time and part-time students, both on and off campus, are included. The sampling frame consisted of a list of students provided by the Royal Military College. All individuals on the student list were included in the sample and sent to collection.

Data collection took place from February to July 2019 inclusively. Responses were obtained by self-administered online questionnaire. Respondents were able to respond in the official language of their choice.

There were 512 respondents to the survey, and the overall response rate was 28%. Non-respondents included people who refused to participate. Respondents in the sample were weighted so that their responses represent students who attended the RMC or the RMC SJ in the fall of 2018.

For information on the methodology used for the SISPSP general student population, see (Burczycka 2020a; Burczycka 2020b).

Data limitations

As with any survey, there are some data limitations. The survey is subject to non-sampling error such as non-response error and measurement error.

For the quality of estimates, the lower and upper bounds of the confidence intervals are presented. Confidence intervals should be interpreted as follows: If the survey were repeated many times, then 95% of the time (or 19 times out of 20), the confidence interval would cover the true population value.

References

Antecol, H. and D. Cobb-Clark. 2001. “Men, Women, and Sexual Harassment in the U.S. Military.” Gender Issues. Winterm. p. 3-18.

Burczycka, M. 2020a. “Students’ experiences of discrimination based on gender, gender identity and sexual orientation at postsecondary schools in the Canadian provinces, 2019.” Juristat. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 85-002-X.

Burczycka, M. 2020b. “Students’ experiences of unwanted unwanted sexualized behaviours and sexual assault at postsecondary schools in the Canadian provinces, 2019.” Juristat. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 85-002-X.

Burczycka, M. 2019. Sexual Misconduct in the Canadian Armed Forces Primary Reserve, 2018. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 85-603-X.

Castro, C.A., Kintzle, S., Schuyler, A.C., Lucas, C.L., and Warner, C.H. 2015. “Sexual assault in the military.” Current Psychiatry Reports. Vol. 17, no. 54. p. 1-13.

Conroy, S. and A. Cotter. 2017. “Self-reported sexual assault in Canada, 2014.” Juristat. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 85-002-X.

Cotter, A. 2019. Sexual Misconduct in the Canadian Armed Forces Regular Force, 2018. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 85-603-X.

Cotter, A. 2016. Sexual Misconduct in the Canadian Armed Forces, 2016. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 85-603-X.

Cotter, A. and Savage, L. 2019. “Gender-based violence and unwanted sexual behaviour in Canada, 2018: Initial findings from the Survey of Safety in Public and Private Spaces.” Juristat. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 85-002-X.

Deschamps, M. 2015. External Review into Sexual Misconduct and Sexual Harassment in the Canadian Armed Forces.

Government of Canada. 2018. Canadian Forces Leadership and Recruit School. (accessed February 7, 2020).

Leblanc, M. and Coulthard, J. 2015. The Canadian Forces Workplace Harassment Survey: Findings from

Designated Group Members. Director General Military Personnel Research and Analysis Scientific Letter, DRDC-RDDC-2015-L179, June 2015.

Maher, T.M. 2010. “Police sexual misconduct: Female police officers’ views regarding its nature and extent.” Women and Criminal Justice. Vol. 20. p. 263-282.

Perreault, Samuel. 2017. “Canadians’ perceptions of personal safety and crime, 2014.” Juristat. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 85-002-X.

Rosen, L.N., Knudson, K.H. and P. Fancher. 2003. “Cohesion and the culture of hypermasculinity in U.S. Army Units.” Armed Forces & Society. Vol. 29, no. 3, Spring. p. 325-351.

Royal Military College of Canada. 2019. “About RMC.” (accessed December 10, 2019).

Sadler, A.G., Lindsay, D.R., Hunter, S.T. and Day, D.V. 2018. “The impact of leadership on sexual harassment and sexual assault in the military.” Military Psychology, Vol. 30, no.3. p. 252-263.

Snyder, J.A., Scherer, H.L., and Fisher, B.S. 2012. “Social organization and social ties: Their effects on sexual harassment victimization in the workplace.” Work. Vol. 42. p. 137-150.

Turchick, J.A. and S.M. Wilson. 2010. “Sexual assault in the U.S. military: A review of the literature and recommendations for the future.” Aggression and Violent Behavior. Vol. 15. p. 267-277.

Vogt, D., Bruce, T.A., Street, A.E. and J. Stafford. 2007. “Attitudes toward women and tolerance for sexual harassment among Reservists.” Violence Against Women. Vol. 13, no. 9. p. 879-900.

- Date modified: