Students’ experiences of unwanted sexualized behaviours and sexual assault at postsecondary schools in the Canadian provinces, 2019

by Marta Burczycka, Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics

Highlights

- A majority (71%) of students at Canadian postsecondary schools witnessed or experienced unwanted sexualized behaviours in a postsecondary setting in 2019—either on campus, or in an off-campus situation that involved students or other people associated with the school. Among students, 45% of those who identified as women and 32% of those who identified as men personally experienced at least one such behaviour in the context of their postsecondary studies.

- One in ten (11%) women students experienced a sexual assault in a postsecondary setting during the previous year. About one in five (19%) women who were sexually assaulted said that the assault took the form of a sexual activity to which they did not consent after they had agreed to another form of sexual activity—for example, agreeing to have protected sex and then learning it had been unprotected sex.

- The majority of women (77%) and men (70%) who had experienced a sexual assault in a postsecondary setting stated that at least one incident had happened off campus. For women, off-campus restaurants or bars were the site of half (51%) of sexual assaults in a postsecondary setting.

- Most women (80%) and men (86%) who had experienced unwanted sexualized behaviours stated that the perpetrators of the behaviours were fellow students. Relatively few students said that the perpetrators were professors and others in positions of authority.

- For women students, there was no significant difference in the prevalence of sexual assault among those in programs where most students were men (15%) and those in programs where most students were women (13%). For men, sexual assault was more common for those in programs with a majority of women students (7%) than those in programs with mostly men (4%).

- Less than one in ten women (8%) and men (6%) who experienced sexual assault, and less than one in ten women (9%) and men (4%) who had experienced unwanted sexualized behaviours spoke about what happened with someone associated with the school (such as a teacher, peer support group or someone else associated with either the school administration or a student-led service). While many saw what happened as not serious enough to report, others cited a lack of knowledge about what to do or a mistrust in how the school would handle the situation.

- Most students chose not to intervene, seek help or take other action in at least one instance when they witnessed unwanted sexualized behaviours, including 91% of women and 92% of men who witnessed such behaviours. Many women did not act because they felt uncomfortable (48% of those who did not act), because they feared negative consequences (28%), or because they feared for their safety (18%).

Greater awareness of gender-based violence, sexual consent and related attitudes about what constitutes acceptable behaviour is emerging in many public spheres, including on postsecondary campuses and their online spaces. Widespread disclosures by survivors of various forms of sexual misconduct, propelled by platforms such as #MeToo, have increased the visibility of sexual assault and related behaviours and brought about discussions about their root causes (Hampson 2019; Tambe 2018).

Decades of research on sexual violence in Canada has found correlates between youth and increased risk of victimization (Conroy and Cotter 2017; Perreault 2015; Rotenberg 2017). Young people—particularly young people who identify as women—experience sexual assault and other forms of violence in higher proportions than other people. Additionally, previous Canadian research has found that this group experiences high rates of sexual assault (Conroy and Cotter 2017).

In addition to studies which focus on sexual assault, recent Canadian research has measured the prevalence of unwanted sexualized behaviours in various segments of the population (Burczycka 2019; Cotter 2019; Cotter and Savage 2019). While not necessarily criminal in nature, behaviours such as unwelcome sexual comments, actions or advances can have negative impacts on those who experience them and on others (Cotter and Savage 2019). The present study will be the first to describe the prevalence, characteristics, and attitudes surrounding unwanted sexualized behaviours and sexual assault among Canada’s 2.5 million postsecondary students (see Text box 1).

Developed and conducted by Statistics Canada, the Survey on Individual Safety in the Postsecondary Student Population (SISPSP) collected data from students at postsecondary schools in the Canadian provinces in 2019. The questions included in the survey aimed to measure the nature and prevalence of unwanted sexual and discriminatory behaviours and sexual assault among the students of Canadian postsecondary institutions. Information on students’ attitudes and beliefs was also collected. The survey was funded by the Department for Women and Gender Equality (WAGE) as part of It’s Time: Canada’s Strategy to Prevent and Address Gender-Based Violence. A report focussed on students’ experiences with discriminatory behaviours will follow the present study.

The SISPSP included questions on students’ experiences with ten sexualized behaviours. Some of these were explicitly defined as inappropriate or unwanted (for example, “unwanted physical contact” or “inappropriate discussion of sex life”). Other behaviours were not explicitly defined this way (for example, “sexual jokes” or “encouragement to view sexually explicit materials online”). It should be acknowledged that behaviours such as these may not have been seen by all survey participants as unwanted. However, regardless of how such behaviours are perceived by individuals, they can be indicative of a larger culture in which sexualized behaviours create an atmosphere of fear, disrespect, inequality and invalidation based on gender and sexuality—all of which can have negative consequences for those at whom these behaviours are directed, and for others (Hampson 2019; Levchak 2013; Sue 2010). Because of this, the sexualized behaviours described in the present study are considered to be unwanted, and this terminology is used throughout the analysis.

This Juristat article presents findings on the prevalence, characteristics and impacts of unwanted sexual behaviours, sexual assault and feelings of safety among students aged 18 to 24 at postsecondary institutions in the Canadian provinces (17 to 24 for students living in QuebecNote ). The context in which sexual assault and unwanted sexualized behaviours occurred—where they happened, who was responsible, and who was around—provides insight into the cultural underpinnings of unwanted sexualized behaviours on campus. Together with information on the attitudes and beliefs of students, this analysis provides an indication of postsecondary school culture when it comes to issues surrounding unwanted sexual behaviours and sexual assault.

Start of text box 1

Text box 1

Key terms

The 2019 Survey on Individual Safety in the Postsecondary Student Population (SISPSP) measures behaviours that occurred in the postsecondary school-related setting. Universities, colleges, CEGEPs and other postsecondary institutions are included.Note

The survey collected information on ten unwanted sexualized behaviours. These were:

Inappropriate verbal or non-verbal communication

- Sexual jokes

- Unwanted sexual attention, such as whistles, calls, etc.

- Inappropriate sexual comments about appearance or body

- Inappropriate discussion about sex life

Sexually explicit materials

- Displaying, showing, or sending sexually explicit messages or materials online

- Taking or posting inappropriate or sexually suggestive photos or videos of any student without consent

Unwanted physical contact or suggested sexual relations

- Indecent exposure or inappropriate display of body parts in a sexual manner

- Repeated pressure from the same person for dates or sexual relationships

- Unwelcome physical contact or getting too close

- Someone being offered personal benefits for engaging in sexual activity or being mistreated for not engaging in sexual activity

In addition, the SISPSP measures sexual assault that occurs in the postsecondary setting. For more information on how the survey measures sexual assault, see Text box 2.

The postsecondary school-related setting includes:

- On campus

- While travelling to or from school

- During an off-campus event organized or endorsed by the postsecondary school, including official sporting events

- During unofficial activities or social events organized by students, instructors, professors, either on or off-campus

- An employment at the school

- At a co-op or work term placement organized by the school

- Behaviours that occurred online where some or all of the people responsible were students, teachers or other people associated with the school.

Campus refers to the physical building or buildings in which classes, studies, and activities take place, including (for example) residences, cafeterias, libraries, and lecture halls, as well as adjacent outdoor spaces.

End of text box 1

Almost three-quarters of postsecondary students witnessed or experienced unwanted sexualized behaviours in the past year

Behaviours such as unwelcome sexual comments, actions or advances can have negative impacts on those who experience them, and can create or reinforce stereotypes that affect society more broadly. Some, like unwelcome physical contact or posting sexual photos without consent, could be considered criminal. Others, such as sexual jokes, can represent more subtle ways in which women in particular are objectified, stereotyped and devalued (Sue 2010). Some research has suggested that social environments where women are openly disrespected and objectified are also characterized by justifications for sexual assault and disbelief of those who disclose their experiences (Hampson 2019; Levchak 2013).

Unwanted sexualized behaviours were common in Canadian postsecondary schools in 2019. Overall, more than seven in ten (71%)Note postsecondary students either witnessed these behaviours happening or experienced these behaviours themselves. On the whole, women were more likely than men to have either witnessed or experienced these behaviours (73% versus 69%) (Table 1).Note A particularly large gap between women and men was noted in the prevalence of unwanted sexual attention such as whistles and “catcalls” (40% versus 23%). Large differences were also seen with respect to unwelcome physical contact or getting too close (31% of women, 19% of men) and repeated pressure from the same person for dates or sexual relationships (18% versus 10%)—both of which are behaviours which can meet the threshold for criminality.Note

Men were more likely than women to witness unwanted sexualized behaviours (such as whistles, “catcalls,” etc.) without personally experiencing them (18% versus 13%). However, the proportion of women who had both witnessed and experienced this type of behaviour was five times greater than that of men (27% versus 6%).

Personal experiences of unwanted sexualized behaviours more common for women students

While social environments where sexualized behaviours are frequently witnessed can have a generally negative impact on people’s feelings of being respected, valued and safe (Hampson 2019; Levchak 2013; Sue 2010), personally experiencing such behaviours can bring even stronger negative consequences.

According to the 2019 SISPSP, 45% of women and 32% of men reported having personally experienced at least one unwanted sexualized behaviour in the postsecondary setting during the previous 12 months (Table 2). Sexual jokes were the most common unwanted sexualized behaviour personally experienced by students in the postsecondary setting, including both women (27%) and men (25%), though similar proportions of women specifically also experienced unwanted sexual attention such as whistles and “catcalls” (27%) and unwelcome physical contact or getting too close (21%).

The largest gap between women and men was with respect to unwanted sexual attention, experienced by 27% of women and 6% of men. Major differences were also noted when it came to having personally experienced unwelcome physical contact or getting too close: three times as many women (21%) as men (7%) said that they had personally experienced this type of behaviour. This was also the case when it came to repeated pressure from the same person for dates or sexual relationships (experienced by 11% of women and 3% of men). Women were more likely to have personally experienced each of the ten unwanted sexualized behaviours measured by the survey.

Notably, both unwelcome physical contact or getting too close and repeated pressure from the same person for dates or sexual relationships are behaviours than can be considered criminal in some situations.Note The fact that these particular behaviours are significantly more common among women is telling. While the postsecondary environment appears to be one in which most students come into contact with sexual jokes, conversations and other noncriminal behaviours, women experience the potentially criminal behaviours more often than men—suggesting important disparities exist between how women and men experience the postsecondary environment.

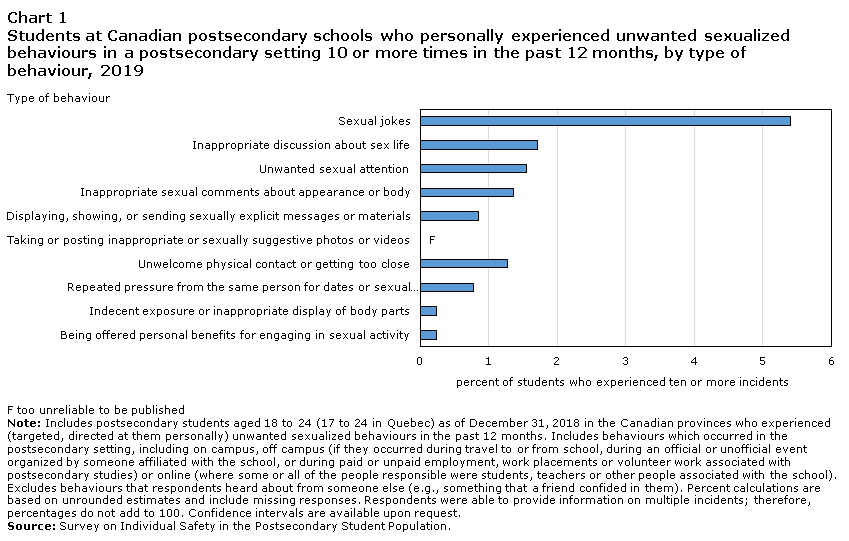

In addition to being the most common, certain behaviours related to inappropriate verbal and non-verbal communication were the ones students more often experienced repeatedly. Of all unwanted sexualized behaviours, sexual jokes were most often experienced ten or more times in the previous 12 months (5% of students). Compared to most other types of unwanted sexualized behaviours, unwanted sexual attention and inappropriate discussion about sex life were more often experienced ten or more times (Chart 1).

Chart 1 start

Data table for Chart 1

| Type of behaviour | Percent of students who experienced ten or more incidents |

|---|---|

| Sexual jokes | 5.4 |

| Inappropriate discussion about sex life | 1.7 |

| Unwanted sexual attention | 1.6 |

| Inappropriate sexual comments about appearance or body | 1.4 |

| Displaying, showing, or sending sexually explicit messages or materials | 0.9 |

| Taking or posting inappropriate or sexually suggestive photos or videos | Note F: too unreliable to be published |

| Unwelcome physical contact or getting too close | 1.3 |

| Repeated pressure from the same person for dates or sexual relationships | 0.8 |

| Indecent exposure or inappropriate display of body parts | 0.2 |

| Being offered personal benefits for engaging in sexual activity | 0.2 |

|

F too unreliable to be published Note: Includes postsecondary students aged 18 to 24 (17 to 24 in Quebec) as of December 31, 2018 in the Canadian provinces who experienced (targeted, directed at them personally) unwanted sexualized behaviours in the past 12 months. Includes behaviours which occurred in the postsecondary setting, including on campus, off campus (if they occurred during travel to or from school, during an official or unofficial event organized by someone affiliated with the school, or during paid or unpaid employment, work placements or volunteer work associated with postsecondary studies) or online (where some or all of the people responsible were students, teachers or other people associated with the school). Excludes behaviours that respondents heard about from someone else (e.g., something that a friend confided in them). Percent calculations are based on unrounded estimates and include missing responses. Respondents were able to provide information on multiple incidents; therefore, percentages do not add to 100. Confidence intervals are available upon request. Source: Survey on Individual Safety in the Postsecondary Student Population. |

|

Chart 1 end

It was less common for women than men to have ten or more experiences of the most common unwanted sexualized behaviour, sexual jokes (4% versus 7% among men). However, women were more likely to have experienced some other unwanted sexualized behaviours ten or more times, including unwanted sexual attention (3% versus 0.3%), and unwelcome physical contact or getting too close (2% versus 0.5 %).

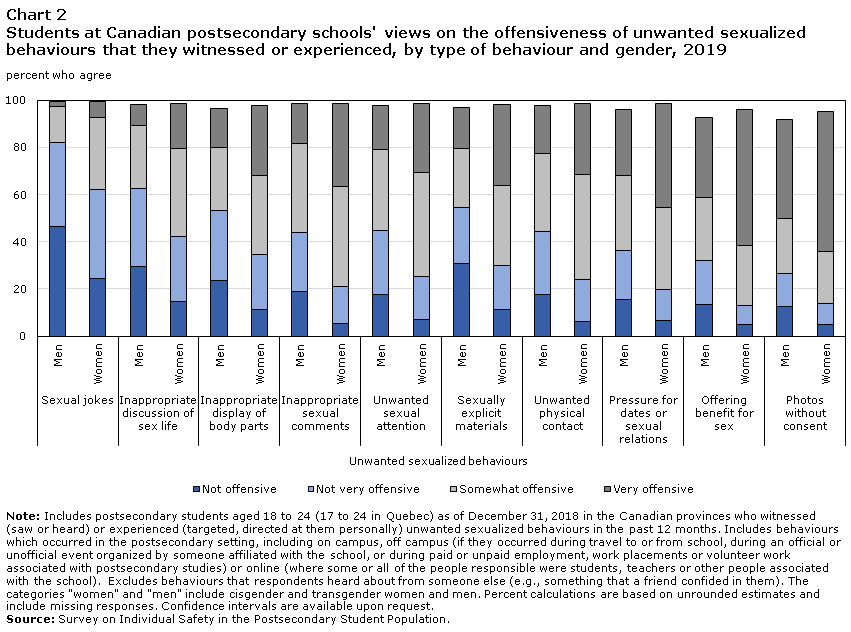

Taking or posting sexual images without consent seen as most offensive by students

Students were asked about how offensive they considered unwanted sexualized behaviours to be. Taking or posting inappropriate or sexually suggestive photos or videos of any student without consent was the behaviour most often seen as very offensive by both the women (59%) and the men (42%) who witnessed or experienced it (Chart 2); it was also the rarest of the ten unwanted sexualized behaviours (witnessed or experienced by 7% of women and 4% of men; Table 1).

Chart 2 start

Data table for Chart 2

| Unwanted sexualized behaviours | Not offensive | Not very offensive | Somewhat offensive | Very offensive | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| percent who agree | |||||

| Sexual jokes | Men | 46.3 | 35.8 | 15.3 | 2.2 |

| Women | 24.5 | 37.7 | 30.5 | 7.0 | |

| Inappropriate discussion of sex life | Men | 29.6 | 32.8 | 26.7 | 9.2 |

| Women | 14.5 | 27.7 | 37.4 | 19.2 | |

| Inappropriate display of body parts | Men | 23.8 | 29.7 | 26.8 | 16.2 |

| Women | 11.3 | 23.2 | 33.7 | 29.6 | |

| Inappropriate sexual comments | Men | 18.9 | 25.1 | 37.4 | 17.0 |

| Women | 5.4 | 15.5 | 42.6 | 35.4 | |

| Unwanted sexual attention | Men | 17.6 | 27.3 | 34.4 | 18.8 |

| Women | 6.9 | 18.5 | 43.9 | 29.3 | |

| Sexually explicit materials | Men | 30.8 | 23.6 | 25.1 | 17.5 |

| Women | 11.3 | 18.5 | 33.9 | 34.6 | |

| Unwanted physical contact | Men | 17.8 | 26.4 | 33.3 | 20.2 |

| Women | 6.3 | 17.6 | 44.5 | 30.4 | |

| Pressure for dates or sexual relations | Men | 15.4 | 20.8 | 32.1 | 27.9 |

| Women | 6.4 | 13.3 | 34.9 | 43.8 | |

| Offering benefit for sex | Men | 13.6 | 18.7 | 26.4 | 33.9 |

| Women | 5.1 | 7.9 | 25.5 | 57.7 | |

| Photos without consent | Men | 12.4 | 14.0 | 23.7 | 41.8 |

| Women | 4.9 | 8.8 | 22.1 | 59.5 | |

|

Note: Includes postsecondary students aged 18 to 24 (17 to 24 in Quebec) as of December 31, 2018 in the Canadian provinces who witnessed (saw or heard) or experienced (targeted, directed at them personally) unwanted sexualized behaviours in the past 12 months. Includes behaviours which occurred in the postsecondary setting, including on campus, off campus (if they occurred during travel to or from school, during an official or unofficial event organized by someone affiliated with the school, or during paid or unpaid employment, work placements or volunteer work associated with postsecondary studies) or online (where some or all of the people responsible were students, teachers or other people associated with the school). Excludes behaviours that respondents heard about from someone else (e.g., something that a friend confided in them). The categories "women" and "men" include cisgender and transgender women and men. Percent calculations are based on unrounded estimates and include missing responses. Confidence intervals are available upon request. Source: Survey on Individual Safety in the Postsecondary Student Population. |

|||||

Chart 2 end

Another behaviour that was considered particularly offensive was being offered personal benefits for engaging in sexual activity or being mistreated for not engaging in sexual activity, characterized as very offensive by women (58%) and, to a lesser degree, by men (34%) (Chart 2). Again, this type of behaviour was witnessed or experienced less often than almost all others (8% of women and 5% of men) (Table 1).

In contrast, those behaviours that were more common were also those usually considered less offensive by both women and men. For instance, sexual jokes—by far the most common type of unwanted sexualized behaviour witnessed or experienced by students—were seen as very offensive by a small proportion of both women (7%) and men (2%), while 30% and 15% (respectively) saw them as somewhat offensive. Meanwhile, the majority of students—62% of women and 82% of men—saw sexual jokes as either not very offensive or not offensive at all. Regardless of the type of behaviour or how rare or common it was, women were more likely than men to see unwanted sexualized behaviours as very offensive.

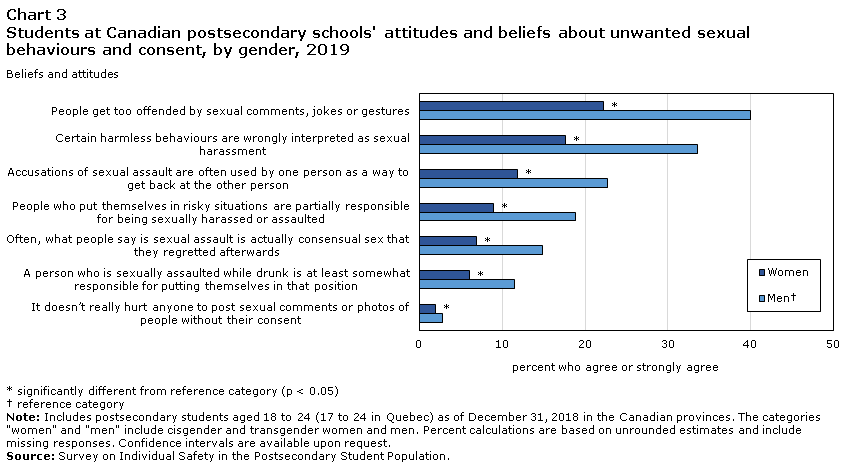

Women and men hold different opinions about some unwanted sexualized behaviours

In line with how offensive certain specific behaviours were perceived to be, students’ general attitudes about issues related to sexualized behaviour varied—especially between women and men. Through several questions adapted from the Campus Climate Validation Study (see Krebs et al. 2016), students were asked about the degree to which they agreed or disagreed with a series of statements. Statements such as “people get too offended by sexual comments, jokes or gestures” were meant to measure the degree to which students saw sexualized behaviours as harmful. Others, such as “accusations of sexual assault are often used by one person as a way to get back at the other person” aimed to gauge students’ rape myth adherence—that is, “attitudes and generally false beliefs about rape […] that serve to deny and justify male sexual aggression against women” (Lonsway and Fitzgerald 1994, p.133). Examples of rape myths include the idea that women who dress in a certain way entice men to commit sexual assault, or that sexual assault cannot happen within an intimate relationship.

When it came to the survey questions aimed to measure these attitudes, 40% of men agreed or strongly agreed with the statement “people get too offended by sexual comments, jokes or gestures,” almost twice the proportion of women (22%) that held that view. Similarly, almost one-quarter of men (23%), along with 12% of women, agreed or strongly agreed that “accusations of sexual assault are often used by one person as a way to get back at the other person.” In all cases, men were significantly more likely to agree or strongly agree with these kinds of statements (Chart 3).

Chart 3 start

Data table for Chart 3

| Beliefs and attitudes | MenData table Note † | Women |

|---|---|---|

| percent who agree or strongly agree | ||

| People get too offended by sexual comments, jokes or gestures | 40.1 | 22.2Note * |

| Certain harmless behaviours are wrongly interpreted as sexual harassment | 33.6 | 17.7Note * |

| Accusations of sexual assault are often used by one person as a way to get back at the other person | 22.8 | 11.8Note * |

| People who put themselves in risky situations are partially responsible for being sexually harassed or assaulted | 18.9 | 9.0Note * |

| Often, what people say is sexual assault is actually consensual sex that they regretted afterwards | 14.9 | 6.8Note * |

| A person who is sexually assaulted while drunk is at least somewhat responsible for putting themselves in that position | 11.5 | 6.0Note * |

| It doesn’t really hurt anyone to post sexual comments or photos of people without their consent | 2.8 | 1.9Note * |

Source: Survey on Individual Safety in the Postsecondary Student Population. |

||

Chart 3 end

Women students more likely to act when seeing others experience unwanted sexualized behaviours

When unwanted sexualized behaviours happen in public places, intervention by the people who witness it can be an effective way to both discourage perpetrators and support those who are targeted (Cadaret et al. 2019). Students were asked about any actions they took—or did not take—when they witnessed these kinds of behaviours in the postsecondary setting.

The majority of students—nine in ten—who witnessed unwanted sexualized behaviours in a postsecondary setting did not take action in response to at least one instance (91% of women and 92% of men) (Table 3). Among both women and men who did not take action, the most common reason was that they did not see the behaviour as serious enough to warrant bystander intervention (69% of women and 81% of men). A belief that it was not their responsibility to take action was also common among both women (32%) and men (26%) who witnessed unwanted sexualized behaviour and did nothing.

Aside from these reasons, many students who witnessed unwanted sexualized behaviours—particularly women—said that they did not take action because they felt uncomfortable, fearful and worried about doing so. Almost half (48%) of women who did not take action said they didn’t do so because they felt uncomfortable, while 28% worried that there could be negative consequences for themselves or others, and 18% feared for their safety. All of these reasons were significantly more common among women, across all three categories of unwanted sexualized behaviours—suggesting women feel different kinds of pressures and constraints when confronted with these situations.

Despite these worries, women were more likely than men to say that they had indeed taken action in at least one instance where they had witnessed unwanted sexualized behaviours (55% of women who had witnessed such behaviours, versus 41% of men). Overall, speaking to those who had been targeted and speaking to those responsible were the most common types of bystander action taken on by both women and men (68% and 60%, and 67% and 80%, of women and men who took action, respectively). Smaller proportions of students reported the behaviour to the school (12% of women, 9% of men), or spoke to someone at a service provided by either the school administration (10% of women, 7% of men) or a student group (6% each).

One in ten women students was sexually assaulted in a postsecondary setting in the previous year

Social environments where sexualized behaviours targeting women are commonplace can also carry an implicit tolerance of sexual assault (Hampson 2019; Warren et al. 2015). To understand how these concepts may interrelate in the postsecondary setting, the 2019 SISPSP aimed to measure Canadian students’ experiences with unwanted sexualized behaviours as well as with sexual assault.

A sexual assault can take different forms, including unwanted sexual touching, sexual activity to which a person did not or was not able to consent, and sexual attacks involving physical force (see Text box 2). One in ten (11%) women who were attending postsecondary school during the time indicated that they had been sexually assaulted in the postsecondary setting in the preceding year—approximately 110,000 individual women students (Table 4).Note Among men, the proportion was considerably smaller (4%). Additionally, almost one in seven women (15%) stated that they had been sexually assaulted in the postsecondary setting at one time during their time at school (either in the previous year or before). This represented approximately 197,000 women, and was proportionally three times higher than among men (5%).Note

In many cases, the same individuals experienced both sexual assault and unwanted sexualized behaviours in the preceding year. In fact, 18% of students who had experienced an unwanted sexualized behaviour in the postsecondary setting had also been sexually assaulted—including 23% of women and 10% of men who had experienced an unwanted sexualized behaviour. This compared to 1% of women and men who had not experienced an unwanted sexualized behaviour. Similarly, 93% of women and 79% of men who had been sexually assaulted in the postsecondary setting had also experienced an unwanted sexualized behaviour, compared to 39% of women and 30% of men who had not been sexually assaulted.

Start of text box 2

Text box 2

How the Survey

on Individual Safety in the Postsecondary Student Population measures sexual

assault

The Criminal Code of Canada includes a broad range of experiences in the definition of sexual assault—ranging from unwanted sexual touching to sexual violence resulting in physical injury or risk to life. Over time, Statistics Canada has incorporated these definitions into questions designed to measure sexual assault in the Canadian population. The 2019 Survey on Individual Safety in the Postsecondary Student Population (SISPSP) includes questions on four types of sexual assault:

- Sexual attack: Forcing or attempted forcing into any unwanted sexual activity, by threatening, holding down, or hurting in some way;

- Unwanted sexual touching: Touching against a person’s will in any sexual way, including unwanted touching or grabbing, kissing, or fondling;

- Sexual activity where unable to consent: Subjecting to a sexual activity to which a person was not able to consent, including being intoxicated, drugged, manipulated, or forced in ways other than physically;

- Sexual activity to which a person did not consent, after they consented to another form of sexual activity (for example, agreeing to protected sex and then learning it had been unprotected sex).

End of text box 2

Postsecondary institutions are spaces where there are many young people, and young people—especially young women—experience sexual assault in higher proportions than other people. Similar questions about sexual assault were asked to Canadians aged 18 to 24 in the general population by the Survey on Safety in Public and Private Spaces (SSPPS). Though the fact that it is not limited to the postsecondary setting makes it not directly comparable to answers provided by the student population, the SSPPS found that 14% of women aged 18 to 24 (17 to 24 in Quebec) in the provinces had been sexually assaulted in the previous 12 months. Among men, the proportion was 3%. In other words, sexual assault is a societal problem that reaches beyond postsecondary institutions; nonetheless, postsecondary institutions may be uniquely positioned to offer support to those who are sexually assaulted and possibly, to effect broader social change.

Most sexual assaults take the form of unwanted sexual touching

Among postsecondary students surveyed by the SISPSP, the most common form of sexual assault was unwanted sexual touching—a finding consistent with what has been seen historically in the general population (Conroy and Cotter 2017). Among women students, 9% indicated that they had experienced this type of sexual assault in the previous 12 months (Table 4). Further, more than half (55%) of women who had experienced unwanted sexual touching stated that they had experienced it more than once in the preceding year.Note

Sexual attacks—the most serious form of sexual assault measured by the SISPSP—were experienced by 2% of women in a postsecondary context in the previous year. The same proportion experienced sexual activity to which they were unable to consent because they were intoxicated, drugged, manipulated or forced in other non-physical ways, and sexual activity to which they did not consent after having consented to another form of sexual activity (for example, agreeing to have protected sex, then learning it was unprotected sex; 2%, respectively) (Table 4).

All forms of sexual assault were considerably less common among men, though the general distribution of the most common forms was similar. For instance, 3% of men experienced unwanted sexual touching in the preceding 12 months, 0.3% experienced sexual attacks, 1% experienced sexual activity to which they were unable to consent, and 0.4% experienced sexual activity to which they did not consent after having consented to another form of sexual activity.

Sexual assaults often include coercion, manipulation and inability to consent

Central to evolving definitions of sexual assault is the issue of consent. The Canadian Criminal Code makes explicit the requirement that sexual activity be consensual in order to be lawful, and outlines situations where consent is by definition impossible. These include situations where the complainant is incapable of consenting (Criminal Code, RSC 1985, c. C-46, s. 273.1 (2) (b)), where the accused induces the complainant to engage in sexual activity by abusing a position of trust or authority (c), where the complainant expresses a lack of agreement to continue to engage in a sexual activity (e), and others. In the wake of #MeToo, conversations about active and ongoing consent have gained momentum; this concept posits that for sexual activity to be unquestionably consensual, those involved should clearly express their continued consent to what is going on throughout the event (Hampson 2019).

In line with these developments, the SISPSP included two measures of sexual assault which specifically take into account the issue of consent: sexual activity where a person was unable to consent because they were intoxicated, drugged, manipulated or forced in other ways than physically; and sexual activity to which a person did not consent after having consented to another form of sexual activity (for example, agreeing to protected sex and then learning it had been unprotected sex) (see Text box 2).

Among women who had been sexually assaulted in a postsecondary setting during the previous 12 months, one in six (16%) indicated that at least one sexual assault had happened as a result of them being unable to consent because they were intoxicated, drugged, manipulated or forced in other non-physical ways (Table 5). About one in five (19%) stated that at least one sexual assault took the form of sexual activity to which they did not consent after they had consented to something else. Taken together—and keeping in mind that many women experienced multiple instances and types of sexual assault—these two kinds of sexual assault were experienced by three in ten (29%) women who had been sexually assaulted.

Proportions among men were somewhat similar, in that 27% of those who had been sexually assaulted indicated that at least one incident had occurred through lack of consent: either they could not consent because they were intoxicated, drugged, manipulated or forced in other ways, or because it was sexual activity to which they did not consent after having consented to another form of sexual activity. The latter type of sexual assault, however, was more common among women who had been sexually assaulted (19%, versus 11% of men).

In addition to sexual assaults which happened directly through coercion or manipulation, students who experienced of any kind of sexual assault were asked whether coercion or manipulation was part of what happened to them. Over one-third of women students who had been sexually assaulted in a postsecondary setting in the past year said that at least one incident had involved continuous verbal pressure even after they said “no” (40%); the same was true for 24% of men. Among women who had been sexually assaulted, 15% had been made afraid of what might happen if they refused, as were 9% of men; 8% of women and 10% of men were threatened with the spread of lies or rumours or the end of a relationship. Additionally, among women specifically,Note 5% were given alcohol or drugs without their knowledge or consent; and 3% (respectively) were threatened with the distribution of intimate content or were afraid that their studies or future career would be at risk if they refused sexual activity.

Students living with a disability, bisexual students more likely to experience sexual assault and unwanted sexualized behaviours

Students living with a disability were overrepresented in terms of having experienced unwanted sexualized behaviours and sexual assault in the postsecondary setting. Specifically, over twice the proportion of students who stated that they lived with some form of physical or mental disabilityNote experienced sexual assault in the past 12 months (12%, versus 5% of students with no disability) (Table 6). This included 15% of women living with a disability (compared to 8% of women with no disability) and 7% of men living with a disability (compared to 3% of men with no disability). These findings mirror those from other population studies, which also found that people living with disabilities—particularly women—were at especially high risk of sexual assault (Cotter 2018).

In addition to sexual assault, the SISPSP found that students living with disabilities also experienced unwanted sexualized behaviours more often (47% versus 34%). Over half (53%) of women students living with a disability experienced unwanted sexualized behaviours, as did almost four in ten of their counterparts who were men (37%).

A high prevalence of sexual assault and unwanted sexualized behaviours in the postsecondary context was noted among bisexual students. Sexual assault was twice as common among this group (16%) as among heterosexual students (7%), for example, and bisexual women had a particularly high incidence (18%)—again reflective of findings from other Canadian studies (Simpson 2018). Bisexual students were also more likely to have experienced unwanted sexualized behaviours (57% versus 37%), according to the SISPSP.

Among First Nations, Métis or InuitNote students, one in ten (10%) experienced a sexual assault in the postsecondary setting in the previous 12 months—a similar proportion to non-Indigenous students (8%).Note Notably, Indigenous men experienced a prevalence of sexual assault in the postsecondary setting that was more than double that of their non-Indigenous counterparts (9% versus 4%). Indigenous women, meanwhile, had a similar prevalence of sexual assault to non-Indigenous women (10% and 11%). Further, sexual assault was as common among Indigenous men as among Indigenous women—a marked contrast to what was seen among non-Indigenous students, where women were considerably more likely to have been sexually assaulted.

Unwanted sexualized behaviours were experienced by the same proportion (39%) of both Indigenous and non-Indigenous students. A larger proportion of Indigenous women 44% than Indigenous men 32% experienced these behaviours.

Sexual assault in the postsecondary setting was slightly less common among students who identified as members of a visible minority group, compared to students who did not. Smaller proportions of students who identified as a visible minority were sexually assaulted (7%, compared to 8% of non-visible minority students), including among women (10% of women students who identified as a visible minority versus 11% who did not) and among men (3% versus 4%).

The prevalence of unwanted sexualized behaviour was also slightly lower among students who identified as a visible minority (36%) than among students who did not identify this way (41%). This was the case for women, among whom those who identified as a visible minority were less likely to have experienced unwanted sexualized behaviours (41%, versus 46% of those who were not a visible minority group), and for men (30% versus 34%).

Other people often present when sexual assaults, unwanted sexualized behaviours happen

The situation in which a sexual assault or an unwanted sexualized behaviour occurred—where it happened and who was involved—can be telling. For example, these factors reveal whether the incident happened in a public space. Research on unwanted sexualized behaviours within other social settings has shown that the degree to which behaviours occur in public versus private spaces is important (Bastomski and Smith 2016; Burczycka 2019; Cotter 2019). Behaviours that take place “behind closed doors” may be less amenable to bystander intervention, while those that happen with many people around—or involved—may reflect a broader culture in which harmful behaviours are tolerated.

Though women students experienced sexual assault in the postsecondary setting in higher proportions than men, some aspects of the sexual assaults that they experienced were similar. For instance, both women and men overwhelmingly indicated that a sole person was most often responsible. More than three-quarters of women (77%) and men (79%) who had been sexually assaulted in a postsecondary setting stated that each instance had involved one perpetrator (Table 7). Smaller proportions stated that two or more people were always involved (5% of women and 6% of men who had been sexually assaulted), or that it varied from incident to incident (9% and 5%).Note

The situation was somewhat similar when it came to some unwanted sexualized behaviours: for instance, among students who had experienced unwanted physical contact or suggested sexual relations, 62% stated that one person was responsible (Table 8). Unwanted physical contact or suggested sexual relations committed by one person was slightly more common among women students who experienced this type of behaviour (64%) than among men (58%).

Although most students who experienced sexual assault or unwanted sexualized behaviours in a postsecondary setting indicated that one person was usually responsible, they also said that in many cases, other people were around when it happened. For instance, three-quarters (74%) of those who experienced inappropriate communication and 65% of those who experienced physical contact or suggested sexual relations said that was the case (Table 8).Note Similarly, many sexual assaults happened with other people present. This was the case for 60% of women students and 65% of men who had experienced at least one incident of unwanted sexual touching, and for 31% of women and 42% of men who experienced sexual activity to which they were unable to consent because they were intoxicated, drugged, manipulated or forced in another non-physical way (differences not found to be statistically significant). These findings suggest that many sexual assaults and unwanted sexualized behaviours do not happen in private, one-on-one situations.

Despite the fact that there were often people around when sexual assaults or unwanted sexualized behaviours happened, these people may not have been aware of the situation or its seriousness, or may have chosen not to act (see Table 3 for self-reported reasons bystanders did not take action). In fact, less than half of people who experienced sexual assault or unwanted sexualized behaviours with other people present said that these people took action in at least one instance. For instance, among women who experienced unwanted sexual touching with other people around, 36% stated that others did something in response to what was going on, such as intervening directly or offering assistance. Among men, this proportion was lower (19%). Similarly, in situations where others were present, 35% of students who experienced inappropriate communication, 34% who experienced sexually explicit materials, and 30% who experienced unwanted physical contact or suggested sexual relations said that someone took action in response (Table 8).

Not all forms of action taken by people that were present were positive for those who experienced sexual assault or unwanted sexualized behaviours. Notably, one in ten (10%) women students who were sexually assaulted in the presence of others who took action stated that the action taken was to encourage the sexual assault.Note

The same was true for unwanted sexualized behaviours. For example, a quarter of students who had experienced behaviours related to sexually explicit materials where others took action said that the action these people took was actually to encourage the behaviour (25%). This was the case for men (29%) and women (22%) who experienced this behaviour in situations where others were around and took action (a difference not found to be statistically significant).

Most sexual assaults, unwanted physical contact or suggested sexual relations happen off campus

Unwanted sexualized behaviours and sexual assaults that happened in the postsecondary context may have taken place on campus, or—if they involved a student, teacher, or happened at an event sanctioned or organized by students or the school—they may have happened in an off-campus or online space (see Text box 1).

Given their association with digital videos and images, behaviours related to sexually explicit materials most often occurred in a school-related online environment (62%, Table 9). Social media was the most common online environment in which students experienced sexually explicit material (78%). School-related online environments could include sites or platforms hosted by the school itself, or those hosted by other entities but on which interactions between students, instructors and others take place.

Inappropriate verbal or non-verbal communication most often occurred on campus (75%), including 73% of the women and 78% of the men who experienced it; the same was true for behaviours related to unwanted physical contact or suggested sexual relations (59%, including 60% of women and 57% of men). In contrast, when it came to sexual assault, almost eight in ten (77%) women and seven in ten (70%) men who had been sexually assaulted stated that at least one incident had occurred in a school-related situation off campus (Table 10).

Many unwanted sexualized behaviours, sexual assaults in the postsecondary setting occur in public areas

Whether they happened on campus or not, sexual assaults and unwanted sexualized behaviours often took place in areas open to the public. For instance, 59% of students (59% of women and 60% of men) who experienced inappropriate communication on campus said that at least one incident had happened at a non-residential building (such as a library, cafeteria or gym) (Table 9). Sexual assaults that happened on campus also most often happened in a non-residential location, as indicated by 41% of women and 36% of men who had been experienced an on-campus sexual assault (Table 10).

A large proportion of sexual assaults and unwanted sexualized behaviours that happened in a postsecondary setting took place in a restaurant or bar off-campus. For women, just over half (51%) of off-campus sexual assaults occurred in a restaurant or bar; among men who had been sexually assaulted off campus, 40% indicated that this was the type of place where it happened (Table 10). As with many other characteristics of sexual assault, its prevalence in bars and restaurants was largely reflective of incidents of unwanted sexual touching (the most common type of sexual assault): half (52%) of all students who experienced this type of sexual assault off campus said that it happened in a restaurant or bar.

Perhaps related to the fact that sexual assaults often happened in bars and restaurants, 48% of women and 55% of men who experienced at least one sexual assault in the postsecondary context said that they believed the sexual assault was related to the perpetrator’s use of alcohol or drugs (Table 7).Note Restaurants and bars were also frequently the setting of behaviours related to inappropriate communication (55%) and physical contact or suggested sexual relations (49%) that happened off campus (Table 9). Overall, similar proportions of women (56%) and men (53%) stated that off-campus unwanted sexualized behaviours happened at a restaurant or bar.

Notably, women who experienced unwanted sexualized behaviours off campus often said that incidents happened during their travels to and from school (40%, versus 22% among men). The same was true for 11% of women and 10% of men who were sexually assaulted off campus.

While most unwanted sexualized behaviours and sexual assaults happened in a public location, many sexual assaults—particularly those that took place off campus—happened in a residential setting. A house or apartment (other than those owned by a fraternity or sorority) was identified as the location of at least one sexual assault by 51% of women and 52% of men who had been sexually assaulted off campus. For men, this was the most common location for off-campus sexual assault (Table 10). Of note, students who either lived in on-campus housing or off campus with roommates had the highest incidence of sexual assault and unwanted sexualized behaviours, compared to students who lived with their parents, their partners, alone or had other arrangements (Table 6).

Fellow students most often responsible for sexual assaults and unwanted sexualized behaviours

The relationship between the person who was sexually assaulted and the perpetrator of the assault provides critical information about the situation in which the incident occurred. For example, situations where the perpetrator is a peer have different implications than situations where the perpetrator is in a position of authority—such as a professor or a coach, in the postsecondary context.

Students who had been sexually assaulted in the postsecondary environment, as well as those who experienced unwanted sexualized behaviours, most often said that peers were responsible. Close to nine in ten (86%) men and eight in ten (80%) women who had experienced unwanted sexualized behaviour stated that in at least one instance, the perpetrator was a student at their school (Table 11). The same was true for sexual assaults: most students who had been sexually assaulted indicated that at least one incident was committed by a fellow student or students (60% of women and 61% of men who were sexually assaulted) (Table 7).

These findings suggest that for the most part, sexual assault and unwanted sexualized behaviours in the postsecondary setting happened outside relationships in which power imbalances are formalized (such as those that exist between students and teachers, or employees and their supervisors). For example, relatively few women students who were sexually assaulted stated that the perpetrator was someone in a position of authority such as a professor, coach, supervisor or employer (2%)Note (Table 7).

However, unwanted sexualized behaviours that did happen within formalized power relationships were more commonly experienced by women. For example, 5% of women who had experienced unwanted sexualized behaviour stated that the perpetrator was a professor or instructor, compared to 2% of men (Table 11).

Current or former casual dating partners were implicated by 12% of both women and men who had been sexually assaulted in the postsecondary setting, and 10% of women and 7% of men said that the perpetrator was a current or former spouse, common-law partner or boyfriend or girlfriend (Table 7). Additionally, current or former spouses, boyfriends or girlfriends (14%) or casual dating partners (15%) were often implicated in behaviours related to sexually explicit materials (Table 8), including similar proportions of women (21%) and men (23%) who experienced this type of behaviour.Note This type of unwanted sexualized behaviour—which includes displaying, showing, or sending sexually explicit messages or materials and taking or posting inappropriate or sexually suggestive photos or videos without consent—could include what is sometimes referred to as “revenge porn,” or other situations in which intimate images shared between partners are later circulated to a wider group. These findings suggest that as is the case elsewhere in society, violence and abuse by intimate partners is an issue in the postsecondary environment.

Unwanted sexualized behaviours in the postsecondary setting most often perpetrated by men

Most often, students who experienced unwanted sexualized behaviours said that the behaviours had been perpetrated by men. More than half (55%) of students who experienced inappropriate communication said that a man or men were always responsible, as did 56% of students who experienced sexually explicit materials and 69% of those who experienced unwanted physical contact or suggested sexual relations (Table 8). This reflected the experiences of women: for instance, almost nine in ten (85%) of women who had experienced unwanted physical contact or suggested sexual relations said that a man or men were responsible, compared to a quarter (25%) of men who had experienced this type of behaviour. Unwanted physical contact or suggested sexual relations perpetrated by women, in contrast, was more common for men who experienced it (42% of men, compared to 4% of women). This pattern was similar, though less pronounced, for other forms of unwanted sexualized behaviours.

Men were responsible for most sexual assaults committed against students in the postsecondary setting: seven in ten (73%) students who had experienced a sexual assault said that every incident that they experienced was committed by a man. As most sexual assaults were committed against women students, this reflects the experiences of women who were sexually assaulted: 90% of women indicated that men were the perpetrators in all instances of sexual assault that they experienced in a postsecondary environment (Table 7). The experiences of men were very different: among men who had been sexually assaulted, 63% stated that women were responsible in all instances. A further 12% stated that a combination of men and women were involved.Note

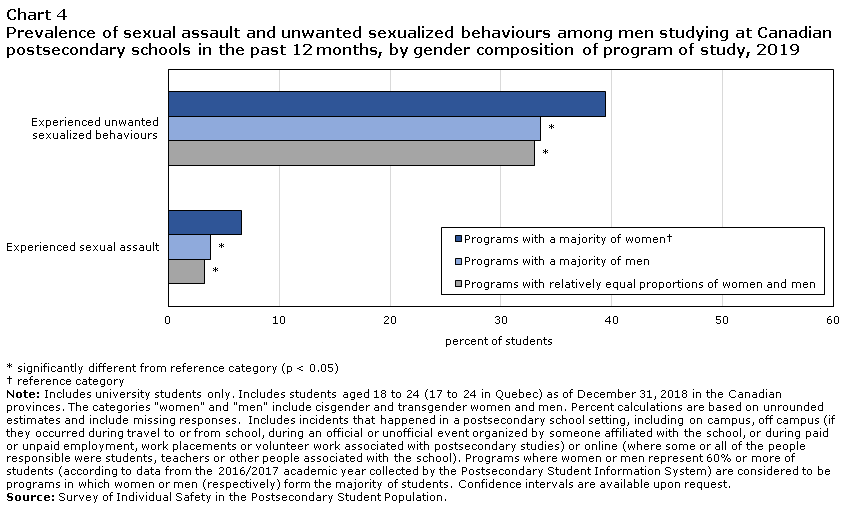

Prevalence of unwanted sexualized behaviours, sexual assault vary based on gender composition of university programs

The prevalence of unwanted sexualized behaviours and of sexual assault varied across university programs of study.Note Students who were enrolled in programs in where 60% or more of the students were women, where 60% or more were men, and where the proportions of men and women were relatively equal had different experiences.

For men, those enrolled in a program in which 60% or more of students were women had a higher prevalence of sexual assault than men enrolled in other programs. One in 14 (7%) men studying in a program where women outnumbered men to this degree had been sexually assaulted in the postsecondary setting, compared to 4% in programs where men represented 60% or more of students and 3% in programs with equal proportions of women and men. Similarly, men in programs where 60% or more of students were women were more likely to have experienced unwanted sexualized behaviours (39%) (Chart 4).

Chart 4 start

Data table for Chart 4

| Gender composition of program of study | Experienced sexual assault | Experienced unwanted sexualized behaviours |

|---|---|---|

| percent of students | ||

| Programs with a majority of womenData table Note † | 6.6 | 39.4 |

| Programs with a majority of men | 3.8Note * | 33.6Note * |

| Programs with relatively equal proportions of women and men | 3.2Note * | 33.0Note * |

Source: Survey of Individual Safety in the Postsecondary Student Population. |

||

Chart 4 end

The situation among women students was different. There was no statistically significant difference in the prevalence of sexual assault among women in programs in where men represented 60% or more of students (15%), compared to those in programs where either 60% or more of students were women (13%) or programs with relatively equal proportions of men and women students (12%).Note Findings were similar when it came to unwanted sexualized behaviours, which were experienced by just under half of women in each of the three program types (Chart 5).

Chart 5 start

Data table for Chart 5

| Gender composition of program of study | Experienced sexual assault | Experienced unwanted sexualized behaviours |

|---|---|---|

| percent of students | ||

| Programs with a majority of women | 12.7 | 49.0 |

| Programs with a majority of men | 15.2 | 47.1 |

| Programs with relatively equal proportions of women and men | 11.6 | 45.8 |

|

Note: Differences are not statistically significant. Includes university students only. Includes students aged 18 to 24 (17 to 24 in Quebec) as of December 31, 2018 in the Canadian provinces. The categories "women" and "men" include cisgender and transgender women and men. Percent calculations are based on unrounded estimates and include missing responses. Includes incidents that happened in a postsecondary school setting, including on campus, off campus (if they occurred during travel to or from school, during an official or unofficial event organized by someone affiliated with the school, or during paid or unpaid employment, work placements or volunteer work associated with postsecondary studies) or online (where some or all of the people responsible were students, teachers or other people associated with the school). Programs where women or men represent 60% or more of students (according to data from the 2016/2017 academic year collected by the Postsecondary Student Information System) are considered to be programs in which women or men (respectively) form the majority of students. Confidence intervals are available upon request. Source: Survey of Individual Safety in the Postsecondary Student Population. |

||

Chart 5 end

It should be noted that these programs represent students’ programs of study at the time the survey was conducted, and may or may not be the same program of study in which a student was enrolled at the time that they experienced a sexual assault or unwanted sexualized behaviour. Students may have transferred out of a program following a sexual assault, for example; information on that original program of study was not available. In addition, it is not known if the student who experienced a sexual assault or unwanted sexualized behaviour was in the same program of study as the perpetrator.

Other research has found that the unequal representation of men in certain fields of study and of women in others has negative consequences for individuals and for the fields of study themselves (Stratton et al. 2005; Wang and Degol 2017). Experiences of sexual assault and unwanted sexualized behaviours discourage some students from enrollment or continuation of study and contribute to ongoing gender disparity within some fields (Barthelemy et al. 2016; Clancy et al. 2014). However, it should be noted that many of these studies look at the interactions that occur in a strictly academic setting: meanwhile, data from the 2019 SISPSP show that most sexual assaults and unwanted sexualized behaviours that occur in the postsecondary context happen outside the classroom. Thus, while the experiences that students have with those with whom they share classes and fieldwork are important to understand, equally critical is an understanding of students’ experiences in other social settings related to their time at postsecondary school.

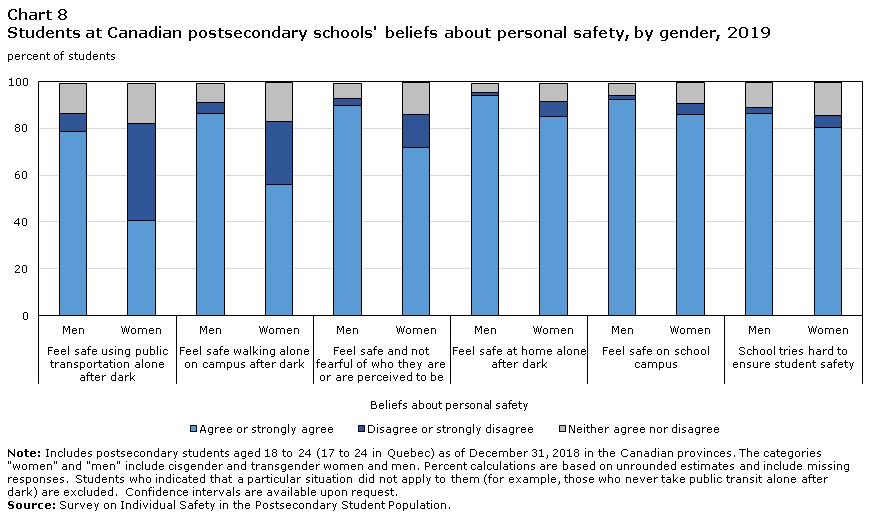

Women more likely to be fearful, change habits due to unwanted sexualized behaviours or sexual assault

Sexual assault and unwanted sexualized behaviours can have wide-ranging and potentially devastating impacts on those who experience them. The SISPSP asked students about how their experiences of sexual assault or unwanted sexualized behaviours in a postsecondary setting had impacted their emotional and mental health, as well as their academic life.

Sexual assault and unwanted sexualized behaviours negatively impacted the emotional well-being of many women and men who experienced them. When it came to the specific types of emotional impacts students reported, a few common issues emerged. Overall, while both women and men indicated that they had experienced negative emotional consequences as a result of their experiences, such consequences were more common for women (Table 12, Table 13). In particular, women were more likely to report impacts related to being fearful for their safety and impacts related to negative mental health. For instance, the proportion of women who said that they became fearful as a result of having experienced unwanted sexualized behaviours were almost six times higher than that of men: almost a quarter (23%) stated that the experience had made them fearful, compared to 4% of men (Table 12). Women who had been sexually assaulted were also more likely to say that they were fearful (38%, compared to 15% of men), while 60% of women who had been sexually assaulted said the experience had made them more cautious or aware (compared to 28% of men; Table 13).

Many women changed the way they travelled to and around their campuses in response to being sexually assaulted or having experienced unwanted sexualized behaviours, re-iterating the fact that these experiences had significant impacts on women’s feelings of safety. Women who were sexually assaulted reported avoiding specific buildings at school (18%) and changing their route to school (9%) (Table 13). These same responses were mentioned by women who had experienced unwanted sexualized behaviours, including avoiding specific buildings at school (18%), changing their routes to school (11%) and the time of day at which they travel to school (11%) (Table 12). These impacts are of particular interest, since many women indicated that unwanted sexualized behaviours happened to them while they were en route to school. The fact these experiences cause many women to live with fear for their personal safety makes clear the seriousness of both sexual assault and unwanted sexualized behaviours that happen in the postsecondary context.

Negative impacts of sexual assault, unwanted sexualized behaviours on mental health more common for women

Additionally, specific impacts on mental health were reported by many students who experienced sexual assault or unwanted sexualized behaviours. While both women and men described these kinds of impacts, they were more common among women: 31% of women who had experienced unwanted sexualized behaviours in the postsecondary context reported being anxious (versus 10% among men) and 8% reported being depressed (versus 4% among men; Table 12). The same was true among those who had been sexually assaulted: 40% of women reported feeling anxious (versus 19% among men), and 21% reported being depressed as a result (versus 9% among men; Table 13). Support from mental health professionals was sought by 7% of women and 2% of men who had personally experienced any unwanted sexualized behaviours in the postsecondary setting, and 12% of women students who had been sexually assaulted in the preceding year (Table 12; Table 13).Note

Women who had been sexually assaulted often felt ashamed (34%) or guilty (28%) as a result. These emotional impacts were less frequently reported by men (13% and 9%). Among men, 45% reported feeling annoyed, and 40% reported feeling confused (Table 13).

Also noteworthy was the proportion of students who said that they used alcohol or drugs to cope with a sexual assault. This was the case for 13% of women and 10% of men who had been sexually assaulted. Unlike many other mental health impacts, use of alcohol or drugs was as common among men as it was among women.

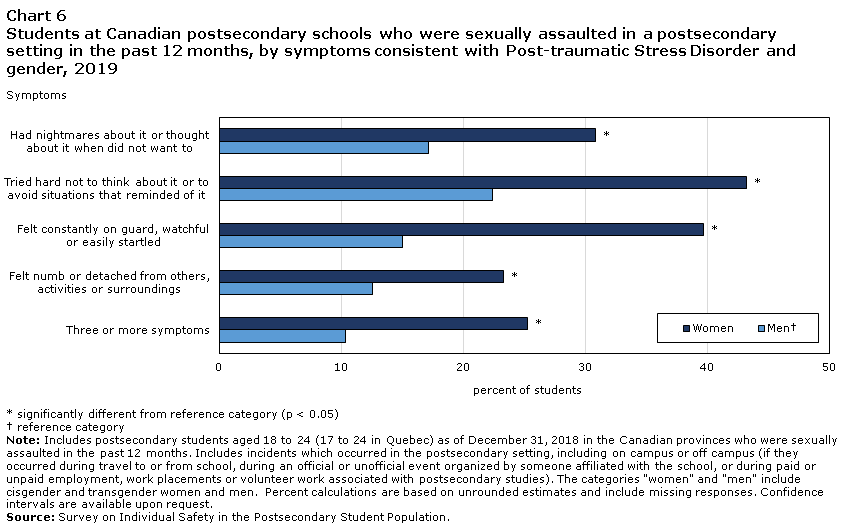

Symptoms consistent with Post-traumatic Stress Disorder reported by many students

In addition to questions about the impact sexual assault had on students’ emotional wellbeing, the SISPSP included a series of questions based on a screening tool used by mental health professionals to assess whether an individual may suffer from Post-traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD).Note Substantial proportions of students who had experienced sexual assault in the postsecondary context provided responses consistent with symptoms of PTSD.

As with other kinds of emotional impacts, symptoms consistent with PTSD were more common for women: for example, 40% of women who had been sexually assaulted felt constantly on guard, watchful or easily startled, compared to 15% of men. This pattern was similar with other symptoms consistent with PTSD, as well (Chart 6). Further, one-quarter (25%) of women who had been sexually assaulted in a postsecondary setting indicated that they had experienced any three of these four symptoms—which, according to the Primary Care PTSD Screen tool, indicates the possible presence of PTSD (Prins et al. 2003). This was more than twice the proportion of men (10%) who reported three or more PTSD-related symptoms.

Chart 6 start

Data table for Chart 6

| Symptoms | MenData table Note † | Women |

|---|---|---|

| percent of students | ||

| Had nightmares about it or thought about it when did not want to | 17.1 | 30.8Note * |

| Tried hard not to think about it or to avoid situations that reminded of it | 22.4 | 43.2Note * |

| Felt constantly on guard, watchful or easily startled | 15.0 | 39.7Note * |

| Felt numb or detached from others, activities or surroundings | 12.6 | 23.3Note * |

| Three or more symptoms | 10.3 | 25.3Note * |

Source: Survey on Individual Safety in the Postsecondary Student Population. |

||

Chart 6 end

Sexual assault, unwanted sexualized behaviours impact students’ academic life

Some students who experienced sexual assault and unwanted sexualized behaviours in a postsecondary setting also reported negative impacts on their academic life. Among students who had been sexually assaulted in the postsecondary setting, some reported stopping going to classes (9% of women and 7% of men who had been sexually assaulted), asking for extensions on assignments (7% of women and 6% of men), and dropping a class (5% of women and 6% of men) (Table 13). These types of impacts were as common among women and men who had been sexually assaulted.

Students who had experienced unwanted sexualized behaviours reported similar academic impacts. For example, 7% of women and 3% of men stated that they had stopped going to some of their classes; 4% of women and 1% of men dropped a class; others indicated that they had asked for extensions (6% of women, 3% of men) or for exams to be rescheduled (2% of women, 1% of men) (Table 12). However, unlike academic impacts of sexual assault, impacts related to unwanted sexualized behaviours were generally more common among women than men.

Few students spoke to someone associated with the school about the sexual assault, unwanted sexualized behaviours they experienced

While many students personally experienced negative impacts associated with both unwanted sexualized behaviours and sexual assault, relatively few spoke about it with someone associated with the school. Of those who had personally experienced unwanted sexualized behaviours in a postsecondary setting, 9% of women and 4% of men spoke with either a faculty member, student support service, campus security, mental health counsellor, chaplain, someone employed at their student residence or someone there who was responsible for students’ wellbeing, or someone else associated with the school (Table 14). Among students who had been sexually assaulted, relatively equal proportions of women (8%) and men (6%) men stated that they had reached out to someone associated with the school (Table 15).

Among students who did speak to someone associated with the school, most spoke to a person or group affiliated with the school administration (for example, a health services centre). This was the case for 60% of women and 63% of men who spoke to someone associated with the school about their experiences of unwanted sexualized behaviours, and 67% of students who spoke about a sexual assault.Note Smaller proportions spoke to someone associated with a student-run group such as peer support group, and others did not know the affiliation of the person or group that they spoke to.

Notably, women who had been sexually assaulted in a postsecondary setting and spoke to someone associated with the school often stated that they did so in order to receive mental health support (65%, Table 15).Note Similarly, seeking mental health support in regards to unwanted sexualized behaviour was a common reason that both women (48%) and men (36%) disclosed their experiences to the school (Table 14). These findings re-iterate the serious effects sexual assault and unwanted sexualized behaviours can have on students’ mental health.

While the proportion of students who spoke to someone associated with their school about their experiences was relatively low, it should be noted that speaking to resources not affiliated with the school was also infrequent. For instance, 11% of women who experienced a sexual assault in the postsecondary setting spoke to mental health resource not affiliated with the school, and 3% reported an incident to the police.Note Generally speaking, these patterns reflect the low rates of reporting found in the general population (Conroy and Cotter 2017).

Many students unaware that their experiences can be reported to the school

Students gave various reasons for why they did not speak to someone associated with their school about the sexual assault or unwanted sexualized behaviours that they experienced. Often, they felt that the issue was not serious enough: this was the case for 59% of women and 61% of men who did not speak to anyone associated with the school about a sexual assault, and 74% of women and 72% of men who did not speak to anyone associated with the school about unwanted sexualized behaviours (Table 14, Table 15).

Some students, however, also indicated that their reasons for not speaking to anyone associated with the school had more to do with the way that they perceived their options for doing so. For example, many students who experienced unwanted sexualized behaviours stated that they were not aware that this type of incident could be reported to the school (26% of women and 10% of men who did not report). This ambiguity may reflect the fact that many sexual assaults and unwanted sexualized behaviours that happened in the postsecondary setting actually happened off campus, and some students may not have been aware that the school could provide assistance in such cases.

Other students who did not speak to anyone associated with the school about unwanted sexualized behaviours stated that they did not do so because they did not think the school would take it seriously (19% of women and 9% of men who did not speak to anyone associated with the school), and that they did not know who at school could provide help (16% and 8%, respectively). Similarly, students who had been sexually assaulted stated that they did not think the school would take the incident seriously (19% of women, 12% of men who did not speak to anyone associated with the school), that they did not know who at the school could provide help (15% and 11%, respectively),Note and that they did not know where to go to get help at school (14% and 8%, respectively).

These findings reflect students’ overall awareness of their schools’ resources related to sexual assault and unwanted sexualized behaviours that happen in a postsecondary setting. When asked about their knowledge of various school policies and procedures, many students said that they were not aware of what was available at school for those who had experienced sexual assault and harassment, and had not received information on these topics from the school. Notably, women students were more likely than men to say that they were not aware of these things and that they had not received information. For example, half (50%) of women students said that they were unaware of procedures for dealing with reported incidents of harassment and sexual assault, compared to 35% of men; similarly, a third (33%) of women students stated that they had not received information from their school about what harassment is and how to recognize it, compared to 23% of men.

Interestingly, more students who had experienced sexual assault were unaware of services (38%) than students who had not been sexually assaulted (28%); the same was true when students who had experienced unwanted sexualized behaviours (33% of whom were unaware of services) were compared to students who had not experienced them (26% of whom were unaware of services) (Table 16). This pattern was repeated for all other questions about the information students had received from their school about sexual assault and harassment.

Notably, awareness of programs and policies was generally higher among students with more years of postsecondary schooling—perhaps reflective of the additional time they have had to learn about these programs.

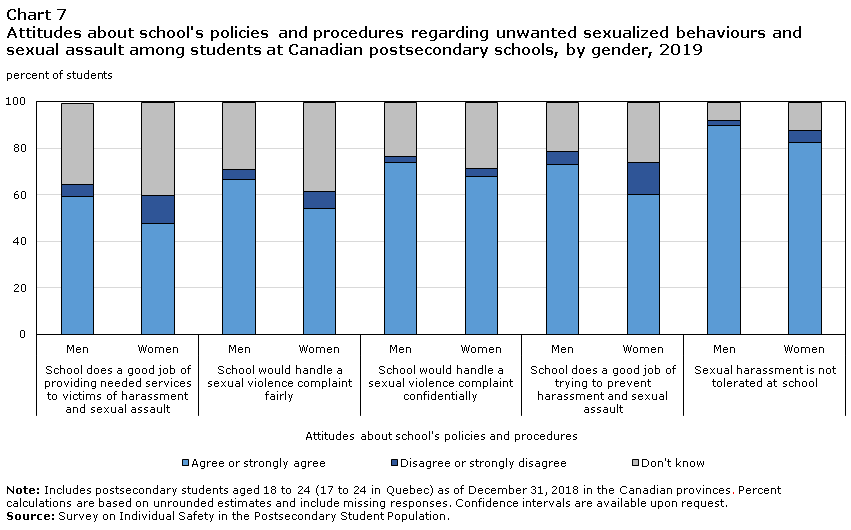

Experiences of sexual assault, unwanted sexualized behaviours tied to negative opinions about schools’ policies

Among students in general, most had positive attitudes about the policies, procedures and services that their school had in place to prevent and address sexual assault and unwanted sexualized behaviour. Negative opinions were, however, more common among women students. More often, women disagreed or strongly disagreed with statements like “my school does a good job of trying to prevent harassment and sexual assault” (14%, versus 6% of men), “my school does a good job of providing needed services to victims of harassment and sexual assault” (12% versus 5%), “my school would handle a sexual violence complaint” either “fairly” (7% versus 4%) or “confidentially” (4% versus 2%), and “sexual harassment is not tolerated at my school” 5% versus 2%) (Chart 7).Note

Chart 7 start

Data table for Chart 7

| Attitudes about school's policies and procedures | School does a good job of providing needed services to victims of harassment and sexual assault | School would handle a sexual violence complaint fairly | School would handle a sexual violence complaint confidentially | School does a good job of trying to prevent harassment and sexual assault | Sexual harassment is not tolerated at school | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | Women | |

| percent of students | ||||||||||

| Agree or strongly agree | 59.0 | 47.6 | 66.5 | 53.9 | 73.9 | 67.6 | 72.8 | 59.8 | 89.7 | 82.2 |

| Disagree or strongly disagree | 5.2 | 11.8 | 4.1 | 7.3 | 2.4 | 3.6 | 5.9 | 13.9 | 2.0 | 5.3 |

| Don't know | 35.1 | 40.0 | 28.9 | 38.5 | 23.1 | 28.4 | 20.8 | 25.8 | 7.9 | 12.2 |

|

Note: Includes postsecondary students aged 18 to 24 (17 to 24 in Quebec) as of December 31, 2018 in the Canadian provinces. Percent calculations are based on unrounded estimates and include missing responses. Confidence intervals are available upon request. Source: Survey on Individual Safety in the Postsecondary Student Population. |

||||||||||

Chart 7 end

Additionally, students who had personally experienced sexual assault or unwanted sexualized behaviours had opinions that were markedly less favorable when compared to those who had not had those experiences. For example, 23% of students who had experienced a sexual assault said that they disagreed or strongly disagreed that their school does a good job of trying to prevent sexual harassment and assault; this proportion was almost three times larger than that of students who had not been sexually assaulted (8%). Similarly, more than twice as many students who had experienced unwanted sexualized behaviours disagreed or strongly disagreed that their school does a good job of trying to prevent sexual harassment and sexual assault (15%, versus 6% of those who had not experienced unwanted sexualized behaviours).

Start of text box 3

Text box 3

Experiences of

transgender students

While anyone can experience sexual assault or unwanted sexualized behaviours, research suggests that transgender people are highly overrepresented among those who have these experiences (Griner et al. 2017; Mitchell et al. 2014). In the analysis that follows, transgender people are defined as anyone who does not identify as cisgender—that is, anyone who identifies with a gender other than the one that they were assigned to at birth, including individuals who do not identify with either of the binary genders, or who identify with a binary gender in addition to another gender.Note According to the SISPSP, 0.8% of postsecondary students were transgender, including 0.1% who were transgender women, 0.2% who were transgender men, and 0.4% who were gender diverse—in all, about 19,000 students.Note

As transgender students represented a small proportion of students surveyed by the SISPSP, limited analysis was possible; however, findings suggest that many transgender students face sexual assault and unwanted sexualized behaviours in the postsecondary setting. About one in six (18%) transgender students were sexually assaulted in a postsecondary setting during their time attending postsecondary school, and unwanted sexualized behaviours were experienced by almost half of transgender students (47%). However, no statistically significant difference was detected between these proportions and the proportions of cisgender students who experienced unwanted sexualized behaviours or sexual assault.

| Type of behaviour | CisgenderText box Note 1 | TransgenderText box Note 2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| percent | 95% confidence interval | percent | 95% confidence interval | |||

| from | to | from | to | |||

| Unwanted sexualized behaviours | 38.8 | 37.9 | 39.7 | 46.9 | 34.8 | 59.3 |

| Inappropriate verbal or non-verbal communicationText box Note 3 | 35.1 | 34.2 | 36.0 | 42.3 | 30.7 | 54.9 |

| Sexually explicit materialsText box Note 4 | 6.4 | 6.0 | 6.9 | Note F: too unreliable to be published | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable |

| Physical contact or suggested sexual relationsText box Note 5 | 18.4 | 17.7 | 19.2 | 22.3 | 13.6 | 34.4 |

| Sexual assault during postsecondary studiesText box Note 6 | 10.3 | 9.8 | 10.8 | 18.1 | 11.2 | 28.1 |

|

... not applicable F too unreliable to be published

Source: Statistics Canada, Survey on Individual Safety in the Postsecondary Student Population. |

||||||