Health Reports

Exploring the intersectionality of characteristics among those who experienced opioid overdoses: A cluster analysis

by Kenneth Chu, Gisèle Carrière, Rochelle Garner, Keven Bosa, Deirdre Hennessy and Claudia Sanmartin

DOI: https://www.doi.org/10.25318/82-003-x202300300001-eng

Abstract

Background

As Canada continues to experience an opioid crisis, it is important to understand the intersection between the demographic, socioeconomic and service use characteristics of those experiencing opioid overdoses to better inform prevention and treatment programs.

Data and methods

The Statistics Canada British Columbia Opioid Overdose Analytical File (BCOOAF) represents people’s opioid overdoses between January 2014 and December 2016 (n = 13,318). The BCOOAF contains administrative health data from British Columbia linked to Statistics Canada data, including on health, employment, social assistance and police contacts. Cluster analysis was conducted using the k-prototypes algorithm.

Results

The results revealed a six-cluster solution, composed of three groups (A, B and C), each with two distinct clusters (1 and 2). Individuals in Group A were predominantly male, used non-opioid prescription medications and had varying levels of employment. Individuals in Cluster A1 were employed, worked mostly in construction, had high incomes and had a high rate of fatal overdoses, while individuals in Cluster A2 were precariously employed and had varying levels of income. Individuals in Group B were predominantly female; were mostly taking prescription opioids, with about one quarter or less receiving opioid agonist treatment (OAT); mostly had precarious to no employment; and had low to no income. People in Cluster B1 were primarily middle-aged (45 to 65 years) and on social assistance, while people in Cluster B2 were older, more frequently used health services and had no social assistance income. Individuals in Group C were primarily younger males aged 24 to 44 years, with higher prevalence of having experienced multiple overdoses, were medium to high users of health care services, were mostly unemployed and were recipients of social assistance. Most had multiple contacts with police. Those in Cluster C1 predominantly had no documented use of prescription opioid medications, and all had no documented OAT, while all individuals in Cluster C2 were on OAT.

Interpretation

The application of machine learning techniques to a multidimensional database enables an intersectional approach to study those experiencing opioid overdoses. The results revealed distinct patient profiles that can be used to better target interventions and treatment.

Keywords

opioid overdose; cluster analysis; linked data; intersectionality

Authors

Kenneth Chu and Keven Bosa are with the Data Science Division, Statistics Canada. Gisèle Carrière, Rochelle Garner and Deirdre Hennessy are with the Health Analysis Division, Statistics Canada. Claudia Sanmartin is with the Analytical Studies and Modelling Branch, Statistics Canada.

What is already known on this subject?

- In Canada, apparent opioid toxicity deaths increased by 96% in the first year of the pandemic (April 2020 to March 2021) compared with the same period the preceding year.

- Provincial and territorial surveillance reports have identified several subpopulations that are most affected by this opioid crisis, including people without housing or who were precariously housed, those with lower levels of income and education, those with unstable employment, and people employed within certain industries (e.g., construction).

What does this study add?

- Distinct profiles of people’s health system use (or non-use), socioeconomic circumstances and justice system contact (or non-contact) among people who experienced opioid overdoses in British Columbia, Canada, were revealed by applying machine learning techniques.

- This approach to analyzing complex dynamics among the factors contained in these multidimensional data can be used to provide information to support policy and program planning aimed at better targeting interventions to assist people’s treatment and preventing or lessening overdose harms.

Introduction

Canada continues to experience an unregulated drug toxicity crisis primarily involving opioids. There was a total of 32,632 apparent opioid toxicity deaths between January 2016 and June 2022.Note 1 The COVID-19 pandemic is contributing to this crisis by indirectly affecting the health of Canadians as a result of changes to the drug supply; reduced access to services; and increasing feelings of isolation, stress and anxiety.Note 2Note 3Note 4Note 5 During the first year of the pandemic (from April 2020 to March 2021), 7,362 deaths occurred, representing a 96% increase from the same period the year preceding the pandemic.Note 1

Attention has increasingly been turning toward better understanding the characteristics of individuals who experience opioid overdoses to better target prevention and harm reduction programs.Note 6Note 7Note 8 A review of provincial and territorial surveillance reports identified several subpopulations most affected by the opioid crisis, including people without housing or who are precariously housed, people who are incarcerated, and First Nations people.Note 9 A national study of opioid poisoning-related hospitalizations revealed higher rates among people with lower levels of income and education, people who were unemployed or out of the labour force, Indigenous people, people living in lone-parent households, and people who spend more than 50% of their income on housing.Note 10

A recent study describing individuals who experienced opioid overdoses in British Columbia highlights the heterogeneity within this population. Approximately one-third were employed and most worked in construction in the year prior to their index overdose. Most employed people experienced periods of unemployment in the five years prior to their index opioid overdose, and half received social assistance during that same period. Approximately 40% of them experienced at least one contact with police in the two years prior to their overdose. In addition, 62% of individuals visited an emergency department in the year prior to their overdose, with 37% of these visits having been for an injury or poisoning (other than an opioid overdose).Note 11 Similar results were observed for those individuals who experienced an opioid overdose in the Simcoe Muskoka region of Ontario between 2018 and 2019.Note 12 Most recently, it was reported that for Ontario overall, people with a history of employment in construction were disproportionately overrepresented in opioid toxicity deaths.Note 13

While these findings provide greater insights regarding the upstream socioeconomic circumstances and service use of individuals experiencing opioid overdoses, largely through univariate analysis, a better understanding of the intersections between these characteristics is required to guide targeted approaches for prevention and treatment. Machine learning techniques, such as clustering, consider a large number of variables and complex interactions to generate comprehensive profiles, including for the purposes of describing people suffering from substance use overdose.Note 14 This approach has been commonly used with demographic, health and socioeconomic information to identify distinct groups or phenotypes among patients who use substances, including people with diagnosed opioid and stimulant use disorders,Note 15Note 16 people who inject drugs,Note 17 and people who use cannabis or consume alcohol.Note 18Note 19

This study aims to identify distinct groups of individuals with unique sets of characteristics and experiences among those who had an opioid overdose in one Canadian province between 2014 and 2016. This is achieved by conducting a cluster analysis using an integrated dataset containing demographic, socioeconomic, health care service use and police contact information. The study applied an unsupervised machine learning technique that partitions data points into clusters based on their similarity.Note 20

Methods

Data

This study used the Statistics Canada British Columbia Opioid Overdose Analytical File (BCOOAF), an integrated database representing individuals experiencing fatal and non-fatal opioid overdoses between 2014 and 2016 in British Columbia. The BCOOAF is composed of administrative health data sources from British Columbia (BC Emergency Health Services, Medical Services Plan, PharmaNet and BC Coroners Service) integrated with administrative data available at Statistics Canada, including health (Discharge Abstract Database, National Ambulatory Care Reporting System and Canadian Vital Statistics Database), employment (Longitudinal Worker File), social assistance (T5007 forms) and justice (Uniform Crime Reporting Survey, Integrated Criminal Court Survey and Integrated Correctional Services Survey) data. Linkages were conducted using a range of methods within the Social Data Linkage Environment (SDLE) at Statistics Canada. The SDLE is a highly secure linkage environment established to support the creation of linked population data files for analysis through linkage to a central depository called the Derived Record Depository, a dynamic relational database containing only basic personal identifiers.Note 21 Opioid overdoses were identified using the protocol published by researchers at the British Columbia Centre for Disease Control.Note 22 Information on the data integration methods and cohort definitions are published elsewhere.Note 23

Study cohort

The BCOOAF includes 13,318 individuals who experienced a total of 19,125 opioid overdose events over a three-year period (January 1, 2014, to December 31, 2016), of which 1,475 were fatal. Cohort characteristics are provided in Table 1.

| All | Females | Males | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N=13,318 | % | N=4,626 | % | N=8,682 | % | |

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | 4,626 | 34.73 | 4,626 | 100.00 | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable |

| Male | 8,682 | 65.19 | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | 8,682 | 100.00 |

| Unknown | 10 | 0.08 | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable |

| Age group | ||||||

| Younger than 15 | 71 | 0.53 | 35 | 0.76 | 35 | 0.40 |

| 15 to younger than 25 | 1,916 | 14.39 | 773 | 16.71 | 1,142 | 13.15 |

| 25 to younger than 45 | 6,085 | 45.69 | 1,896 | 40.99 | 4,184 | 48.19 |

| 45 to younger than 65 | 4,104 | 30.82 | 1,355 | 29.29 | 2,746 | 31.63 |

| 65 and older | 1,142 | 8.57 | 567 | 12.26 | 575 | 6.62 |

| Number of opioid overdoses | ||||||

| 1 | 10,389 | 78.01 | 3,691 | 79.79 | 6,691 | 77.07 |

| 2 or more | 2,929 | 21.99 | 935 | 20.21 | 1,991 | 22.93 |

| Fatal overdose | ||||||

| No | 11,843 | 88.92 | 4,318 | 93.34 | 7,515 | 86.56 |

| Yes | 1,475 | 11.08 | 308 | 6.66 | 1,167 | 13.44 |

| Health care use in the year prior to the opioid overdose | ||||||

| Any prescription | ||||||

| No | 1,711 | 12.85 | 324 | 7.00 | 1,377 | 15.86 |

| Yes | 11,607 | 87.15 | 4,302 | 93.00 | 7,305 | 84.14 |

| Opioid prescriptionTable 1 Note 1 | ||||||

| No | 7,209 | 54.13 | 2,229 | 48.18 | 4,970 | 57.24 |

| Yes | 6,109 | 45.87 | 2,397 | 51.82 | 3,712 | 42.76 |

| Opioid agonist treatment | ||||||

| No | 10,238 | 76.87 | 3,638 | 78.64 | 6,590 | 75.90 |

| Yes | 3,080 | 23.13 | 988 | 21.36 | 2,092 | 24.10 |

| Emergency department visitsTable 1 Note 2 | ||||||

| None | 5,055 | 37.96 | 1,654 | 35.75 | 3,401 | 39.17 |

| 1 to 3 | 5,003 | 37.57 | 1,755 | 37.94 | 3,243 | 37.35 |

| 4 or more | 3,260 | 24.48 | 1,217 | 26.31 | 2,038 | 23.47 |

| Hospital admissionsTable 1 Note 3 | ||||||

| None | 9,424 | 70.76 | 3,005 | 64.96 | 6,412 | 73.85 |

| 1 to 3 | 3,287 | 24.68 | 1,340 | 28.97 | 1,944 | 22.39 |

| 4 or more | 607 | 4.56 | 281 | 6.07 | 326 | 3.75 |

| EmploymentTable 1 Note 4 history five years prior to the opioid overdose | ||||||

| Number of years employedTable 1 Note 4 | ||||||

| None | 5,397 | 40.52 | 2,330 | 50.37 | 3,059 | 35.23 |

| 1 | 1,377 | 10.34 | 459 | 9.92 | 918 | 10.57 |

| 2 | 1,295 | 9.72 | 361 | 7.80 | 933 | 10.75 |

| 3 | 1,161 | 8.72 | 330 | 7.13 | 831 | 9.57 |

| 4 | 1,265 | 9.50 | 366 | 7.91 | 899 | 10.35 |

| 5 | 2,689 | 20.19 | 722 | 15.61 | 1,966 | 22.64 |

| Unknown | 134 | 1.01 | 58 | 1.25 | 76 | 0.88 |

| Main industry of employmentTable 1 Note 5 (NAICS) in the calendar year of the index overdose | ||||||

| Unclassified (0) | 45 | 0.34 | 21 | 0.45 | 24 | 0.28 |

| Agriculture, forestry, fishing and hunting (11) | 107 | 0.80 | 10 | 0.22 | 97 | 1.12 |

| Mining, quarrying, and oil and gas extraction (21) | 86 | 0.65 | 7 | 0.15 | 79 | 0.91 |

| Construction (23) | 951 | 7.14 | 47 | 1.02 | 904 | 10.41 |

| Manufacturing (31 to 33) | 324 | 2.43 | 36 | 0.78 | 288 | 3.32 |

| Wholesale trade (41) | 161 | 1.21 | 26 | 0.56 | 135 | 1.55 |

| Retail trade (44 and 45) | 436 | 3.27 | 210 | 4.54 | 226 | 2.60 |

| Transportation and warehousing (48 and 49) | 231 | 1.73 | 38 | 0.82 | 193 | 2.22 |

| Information and cultural industries (51) | 70 | 0.53 | 18 | 0.39 | 51 | 0.59 |

| Finance and insurance (52) | 71 | 0.53 | 38 | 0.82 | 33 | 0.38 |

| Real estate and rental and leasing (53) | 78 | 0.59 | 18 | 0.39 | 60 | 0.69 |

| Professional, scientific and technical services (54) | 127 | 0.95 | 37 | 0.80 | 90 | 1.04 |

| Administrative and support, waste management and remediation services (56) | 542 | 4.07 | 72 | 1.56 | 470 | 5.41 |

| Educational services (61) | 84 | 0.63 | 47 | 1.02 | 37 | 0.43 |

| Health care and social assistance (62) | 221 | 1.66 | 157 | 3.39 | 64 | 0.74 |

| Arts, entertainment and recreation (71) | 74 | 0.56 | 34 | 0.73 | 40 | 0.46 |

| Accommodation and food services (72) | 521 | 3.91 | 250 | 5.40 | 270 | 3.11 |

| Other services (except public administration (81) | 197 | 1.48 | 82 | 1.77 | 115 | 1.32 |

| Public administration (91) | 108 | 0.81 | 50 | 1.08 | 58 | 0.67 |

| Not employed or unknown | 8,868 | 66.59 | 3,423 | 73.99 | 5,437 | 62.62 |

| dollars | ||||||

| Annual earnings in the year prior to the index overdoseTable 1 Note 5 | ||||||

| Median | Note ...: not applicable | 0 | Note ...: not applicable | 0 | Note ...: not applicable | 0 |

| 25th percentile | Note ...: not applicable | 0 | Note ...: not applicable | 0 | Note ...: not applicable | 0 |

| 75th percentile | Note ...: not applicable | 6,877 | Note ...: not applicable | 1,738 | Note ...: not applicable | 10,770 |

| number | percent | number | percent | number | percent | |

| Social assistance receipt in the five years prior to the opioid overdoseTable 1 Note 6 | ||||||

| Received social assistance in the calendar year of the index overdoseTable 1 Note 6 | ||||||

| No | 6,542 | 49.12 | 2,192 | 47.38 | 4,343 | 50.02 |

| Yes | 6,642 | 49.87 | 2,376 | 51.36 | 4,263 | 49.10 |

| Unknown | 134 | 1.01 | 58 | 1.25 | 76 | 0.88 |

| Number of years on social assistanceTable 1 Note 6 | ||||||

| 0 | 5,792 | 43.49 | 2,017 | 43.60 | 3,767 | 43.39 |

| 1 | 931 | 6.99 | 250 | 5.40 | 681 | 7.84 |

| 2 | 863 | 6.48 | 268 | 5.79 | 595 | 6.85 |

| 3 | 848 | 6.37 | 247 | 5.34 | 601 | 6.92 |

| 4 | 874 | 6.56 | 275 | 5.94 | 599 | 6.90 |

| 5 | 3,876 | 29.10 | 1,511 | 32.66 | 2,363 | 27.22 |

| Unknown | 134 | 1.01 | 58 | 1.25 | 76 | 0.88 |

| dollars | ||||||

| Amount of social assistance received in the year prior to the index overdoseTable 1 Note 6 | ||||||

| Median | Note ...: not applicable | 0 | Note ...: not applicable | 0 | Note ...: not applicable | 0 |

| 25th percentile | Note ...: not applicable | 0 | Note ...: not applicable | 0 | Note ...: not applicable | 0 |

| 75th percentile | Note ...: not applicable | 7,649 | Note ...: not applicable | 9,324 | Note ...: not applicable | 7,216 |

| number | percent | number | percent | number | percent | |

| Police contactsTable 1 Note 7 | ||||||

| None | 8,148 | 61.18 | 3,264 | 70.56 | 4,874 | 56.14 |

| 1 | 1,744 | 13.10 | 537 | 11.61 | 1,207 | 13.90 |

| 2 or more | 3,426 | 25.72 | 825 | 17.83 | 2,601 | 29.96 |

... not applicable

Source: Statistics Canada British Columbia Opioid Overdose Analytical File, Statistics Canada. |

||||||

Variables

All variables were measured at the person level (see Table 1). Demographic variables included sex and age (grouped) at the time of the index (or first) opioid overdose. People who died between January 1, 2014, and December 31, 2016, and whose death was determined by the BC Coroner to be attributable to illicit drug toxicity (i.e., opioids that were not prescribed) were classified as having had fatal overdoses. Other individuals, including those who may have died during the same observation period because of other causes, were classified as having had non-fatal overdoses, because they had one or more opioid overdoses but were not among the opioid-related decedents provided by the BC Coroner. Based on information contained in the PharmaNet data, individuals were classified as either having been dispensed any prescription medications in the year prior to the overdose (yes, no). If yes, then prescribed opioids were identified and among these, whether opioids were prescribed for opioid agonist treatment (OAT) or not. The use of health care services in the year prior to the index opioid overdose included the number of visits to an emergency room and the number of acute care hospital admissions. Social assistance was classified as any receipt of assistance in the five years prior to the index opioid overdose (yes, no) and the number of years in which there was any receipt (i.e. , none to five years). A similar approach was used for employment (i.e. , any, duration) and North American Industry Classification System codes for industry of employment. The total amounts of personal income and social assistance were entered as separate continuous variables estimated on an annual basis; those who were not employed or who did not receive social assistance in a given year were assigned $0 for income and social assistance, respectively.

Statistical methods

Since the collection of explanatory variables is a mixture of continuous and categorical variables, the k-prototype algorithm was chosen to perform the cluster analysis. The k‑prototype is a variant of k-means clustering designed to handle explanatory variables of mixed types.Note 24 The k-prototype clustering used the function kproto in the R package clustMixType (version 0.2-1), run in the R statistical computing environment (version 3.5.3).Note 25

For each execution of kproto, 10,000 random initializations were used (nstart = 10,000), and a common value for the continuous/discrete trade-off parameter lambda was used for all the discrete variables. For each execution of kproto, the common lambda value was set with the default mechanism, namely the return value of the lambdaest function in clustMixType with parameter values num.method = fac.method = 1. Nine rounds of clustering were conducted with prescribed numbers of n-cluster solutions beginning with n = 2, 3, … to 10.

Elbow and silhouette plots were used to inform the selection of the optimal n-cluster solution. While these measures provide guidance, they cannot be used in isolation. Review by subject-matter experts to assess face validity and corroboration with other research are also required to determine the final n-cluster solution.Note 19 This was conducted through several rounds of review by the authors of the distribution of characteristics across the cluster solutions for each prescribed number (n) of clusters (n = 2, 3, …, 10).

A stability assessment was conducted of the resulting clusters relative to the random initiations of the k-prototype algorithm. Following a review of the cluster solutions, 10 rounds of clustering by k-prototype, each with 10,000 random starts, were conducted for three of the potentially final cluster solutions, yielding 45 = 10 (10 - 1) / 2 distinct pairs for each of the three candidate prescribed numbers of clusters. For each pair, two similarity measures were calculated:

- the joint-entropy-normalized mutual information (JE-NMI), a complement to the normalized variation of information (NVI)

- the maximal overlap over cluster relabelling (MOCR) similarity score.Note 26Note 27

While the JE-NMI is supported by well-developed theory, it is difficult to interpret numerically. On the other hand, the MOCR provides a more intuitive numerical interpretation, with values bounded between 0 and 1 representing the level of agreement between the pairs. For example, an MOCR = 0.95 means that, under optimal cluster relabelling, there is a 95% level of agreement at the individual record level between the two pairs of cluster solutions. Cluster stability was assessed using the resulting density plot and histogram of the two stability measures.

Results

Study cohort

The characteristics of the study cohort are presented in Table 1. Overall, 65.2% were male and 76.5% were aged 25 to 64 years. The majority (78.0%) experienced one opioid overdose during the observation period, and 88.9% did not experience a fatal opioid overdose during that time. Most individuals (87.2%) were dispensed a prescription medication in the two years prior to the index opioid overdose; 45.9% were dispensed at least one opioid prescription (females: 51.8%; males: 42.8%) and 23.1% were dispensed an OAT. In the year prior to their index opioid overdose, the majority of individuals (62.1%) experienced at least one emergency room visit, and females were hospitalized more often than males (35.0% and 26.2%, respectively). Half (50.4%) of the females and over one-third (35.2%) of the males were not employed in the five years prior to their index opioid overdose—the interquartile range (25th and 75th percentiles) of annual earnings ranged between $0 and $1,738 among females and $0 to $10,770 among males. Approximately half of the cohort (49.9%) received social assistance at least once in the five years preceding the index opioid overdose, with 29.1% receiving it for all five years (females: 32.7%; males: 27.2%), ranging from $0 (25th percentile) to $9,324 (75th percentile) annually among females and $0 to $7,216 among males. Overall, 61.2% of cohort members did not have any contact with police in the two years prior to the index opioid overdose, with higher no-contact prevalence among females (70.6%) compared with males (56.1%).

Cluster analysis

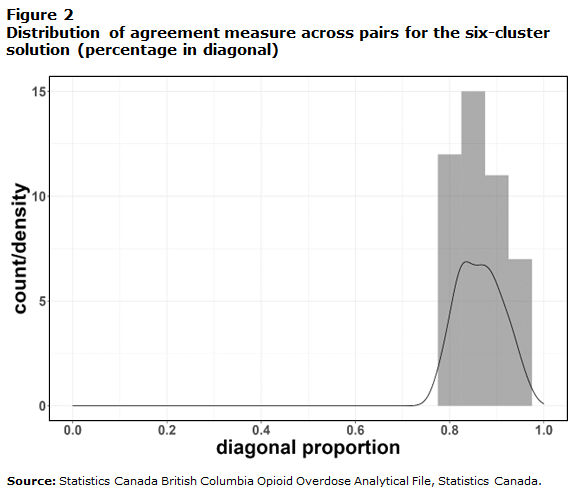

The results of the cluster analysis revealed a six-cluster solution. While both the elbow and silhouette plots (Figures 1A and 1B) appear to indicate a two-cluster solution, upon review it was noted that there was significant heterogeneity within each of the two clusters. Following a review and stability assessment of the six-, seven- and eight-cluster options, the six-cluster solution was deemed optimal. The range of MOCR scores across all pair comparisons for the six‑cluster solution was 78% to 96%, with an overall average of 86.4% (Figure 2). Similar patterns were noted in the NVI. The correlation between the MOCR and JE-NMI scores was 0.99.

A narrative description of the six clusters is provided in Table 2, with frequency distributions provided in Table 3. While there were six distinct clusters, similarities were noted that yielded three groups (A, B and C) each containing two different clusters. Individuals in Group A were predominantly male, used prescription medications (but largely not opioids), had limited use of health care services and received little to no social assistance. Most had no police contacts. The primary differences between clusters A1 and A2 were employment history, income, occupation and the likelihood of experiencing a fatal overdose. Specifically, those in Cluster A1 were primarily of working age (i.e., 25 to 44 years), were employed in all five years prior to the index opioid overdose (with a significant proportion working in construction) and had the highest level of income across the clusters. They were more likely to have experienced a fatal overdose compared with those in Cluster A2, who were more precariously employed and had lower income levels (Table 3).

| Cluster group | General cluster group description | Cluster 1 | Cluster 2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | Males, taking prescription medications but not opioids, some use of emergency room services, little to no use of hospital services, varying levels of employment, income from employment, little to no use of social assistance, most with no police contacts | A1—Aged 25 to 45 years, employed all five years, worked mostly in construction (27%), have highest income levels, have highest rate of fatal overdoses | A2—Varying ages, half not employed, half employed some time, lower income levels |

| B | Females, most taking prescription opioids but not in treatment, precarious to no employment, low income, most with no police contacts | B1—Middle-aged (45 to 65 years); most are on social assistance for five years prior to overdose, are generally unemployed, have low income | B2—Middle to older ages, with one-third older than 65 years, high users of emergency room and hospital services, precariously or not employed, very low to no income |

| C | Males, most taking prescription medications, medium to high users of emergency room services, most unemployed and on social assistance for five years prior to overdose, low income, multiple contacts with police | C1—Few taking prescription opioids, none in treatment | C2—All on opioid agonist treatment, high users of emergency room services |

| Source: Statistics Canada British Columbia Opioid Overdose Analytical File, Statistics Canada. | |||

| Group A | Group B | Group C | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cluster A1 | Cluster A2 | Cluster B1 | Cluster B2 | Cluster C1 | Cluster C2 | |

| N=2,226 | N=3,091 | N=1,846 | N=1,651 | N=2,323 | N=2,181 | |

| percent | ||||||

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | 18.90 | 28.70 | 63.30 | 70.40 | 21.60 | 22.20 |

| Male | 81.00 | 71.10 | 36.70 | 29.50 | 78.40 | 77.80 |

| Age group | ||||||

| 15 to younger than 25 | 6.42 | 34.40 | 5.47 | 9.81 | 9.51 | 8.90 |

| 25 to younger than 45 | 70.30 | 24.00 | 22.00 | 17.60 | 66.30 | 70.70 |

| 45 to younger than 65 | 22.10 | 18.80 | 71.00 | 45.50 | 23.20 | 19.80 |

| 65 and older | 1.26 | 19.60 | 1.46 | 26.90 | 0.90 | 0.69 |

| Number of opioid overdoses | ||||||

| 1 | 85.10 | 87.00 | 77.80 | 81.60 | 72.10 | 61.70 |

| 2 or more | 14.90 | 13.00 | 22.20 | 18.40 | 27.90 | 38.30 |

| Fatal overdose | ||||||

| No | 85.00 | 89.10 | 86.70 | 94.10 | 88.50 | 91.20 |

| Yes | 15.00 | 10.90 | 13.30 | 5.94 | 11.50 | 8.85 |

| Health care use in the year prior to the opioid overdose | ||||||

| Any prescription | ||||||

| No | 22.50 | 23.00 | 4.28 | 1.64 | 16.90 | 0.00 |

| Yes | 77.50 | 77.00 | 95.70 | 98.40 | 83.10 | 100.00 |

| Opioid prescriptionTable 3 Note 1 | ||||||

| No | 75.40 | 79.30 | 32.40 | 19.60 | 93.00 | 0.00 |

| Yes | 24.60 | 20.70 | 67.60 | 80.40 | 7.02 | 100.00 |

| Opioid agonist treatment | ||||||

| No | 91.30 | 94.20 | 72.80 | 84.30 | 100.00 | 10.80 |

| Yes | 8.72 | 5.79 | 27.20 | 15.70 | 0.00 | 89.20 |

| Emergency department visitsTable 3 Note 2 | ||||||

| None | 55.80 | 62.90 | 44.50 | 14.30 | 19.50 | 16.40 |

| 1 to 3 | 34.10 | 25.80 | 29.40 | 58.60 | 53.20 | 32.10 |

| 4 or more | 10.20 | 11.30 | 26.10 | 27.10 | 27.30 | 51.40 |

| Hospital admissionsTable 3 Note 3 | ||||||

| None | 87.60 | 87.70 | 68.20 | 30.50 | 70.40 | 62.60 |

| 1 to 3 | 11.40 | 9.67 | 24.90 | 61.80 | 25.60 | 30.30 |

| 4 or more | 1.03 | 2.59 | 6.93 | 7.63 | 4.05 | 7.15 |

| EmploymentTable 3 Note 4 history five years prior to the opioid overdose | ||||||

| Number of years employedTable 3 Note 4 | ||||||

| None | 0.00 | 45.00 | 64.80 | 48.70 | 42.90 | 46.20 |

| 1 | 1.53 | 11.80 | 12.00 | 8.12 | 14.00 | 13.60 |

| 2 | 4.04 | 11.60 | 8.34 | 6.48 | 13.30 | 12.60 |

| 3 | 5.93 | 9.96 | 6.18 | 8.12 | 10.70 | 10.30 |

| 4 | 9.30 | 11.40 | 5.09 | 10.50 | 10.20 | 9.22 |

| 5 | 79.20 | 8.12 | 3.52 | 15.40 | 8.27 | 7.52 |

| Main industry of employmentTable 3 Note 5 (NAICS) in the calendar year of the index overdose | ||||||

| Construction (23) | 27.90 | 3.43 | 0.87 | 1.03 | 4.30 | 4.17 |

| Manufacturing (31 to 33) | 7.99 | 2.33 | Note x: suppressed to meet the confidentiality requirements of the Statistics Act | 0.90 | 1.33 | 0.88 |

| Wholesale trade (41) | 3.77 | 1.16 | Note x: suppressed to meet the confidentiality requirements of the Statistics Act | 0.61 | 0.65 | Note x: suppressed to meet the confidentiality requirements of the Statistics Act |

| Retail trade (44 and 45) | 6.56 | 4.66 | 1.90 | 3.33 | 1.55 | 0.92 |

| Transportation and warehousing (48 and 49) | 5.84 | 1.13 | Note x: suppressed to meet the confidentiality requirements of the Statistics Act | 1.39 | 0.90 | 0.64 |

| Administrative and support, waste management and remediation services (56) | 7.28 | 3.40 | 2.44 | 1.88 | 4.86 | 3.94 |

| Health care and social assistance (62) | 4.94 | 0.81 | 0.98 | 2.91 | 0.43 | 0.46 |

| Accommodation and food services (72) | 6.24 | 5.99 | 2.00 | 3.57 | 2.76 | 1.70 |

| dollars | ||||||

| Annual earnings in the year prior to the index overdoseTable 3 Note 4 | ||||||

| Median | 36,176 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 25th percentile | 21,211 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 75th percentile | 58,704 | 2,031 | 0 | 1,747 | 561 | 300 |

| Social assistance receiptTable 3 Note 6 | ||||||

| percent | ||||||

| Received social assistance in the calendar year of the index overdoseTable 3 Note 6 | ||||||

| No | 90.80 | 87.90 | 2.11 | 83.10 | 8.48 | 8.94 |

| Yes | 9.16 | 10.00 | 97.90 | 14.20 | 90.90 | 90.60 |

| Number of years on social assistanceTable 3 Note 6 | ||||||

| 0 | 79.40 | 80.30 | 0.00 | 74.70 | 5.08 | 8.80 |

| 1 | 8.81 | 5.89 | 2.60 | 6.36 | 9.43 | 8.30 |

| 2 | 5.84 | 4.95 | 4.71 | 5.03 | 10.40 | 7.75 |

| 3 | 3.37 | 3.24 | 5.36 | 4.66 | 12.30 | 9.72 |

| 4 | 2.16 | 2.39 | 7.75 | 4.06 | 12.30 | 11.80 |

| 5 | 0.45 | 1.20 | 79.60 | 2.48 | 49.90 | 53.10 |

| Unknown | 0.00 | 2.07 | 0.00 | 2.67 | 0.65 | 0.50 |

| dollars | ||||||

| Amount of social assistance receivedTable 3 Note 6 in the year prior to the index overdose | ||||||

| Median | 0 | 0 | 10,945 | 0 | 6,488 | 6,848 |

| 25th percentile | 0 | 0 | 8,763 | 0 | 2,436 | 2,143 |

| 75th percentile | 0 | 0 | 11,312 | 0 | 10,176 | 10,489 |

| percent | ||||||

| Police contactsTable 3 Note 7 | ||||||

| None | 75.70 | 75.30 | 80.90 | 85.60 | 27.90 | 26.50 |

| 1 | 14.90 | 12.40 | 13.10 | 7.93 | 14.80 | 14.30 |

| 2 or more | 9.34 | 12.20 | 5.96 | 6.42 | 57.30 | 59.20 |

x suppressed to meet the confidentiality requirements of the Statistics Act

Source: Statistics Canada British Columbia Opioid Overdose Analytical File, Statistics Canada. |

||||||

Description for Figure 1

Source: Statistics Canada British Columbia Opioid Overdose Analytical File, Statistics Canada.

A : The elbow plot is a scatterplot connected by a line of number of clusters from 0 to 10 on the x-axis by the within-cluster sum of squares from 0 to 200,000 on the y-axis. The following table represents the data points on the graph :

| Number of clusters | Within-cluster sum of squares |

|---|---|

| 1 | 180,000 |

| 2 | 145,000 |

| 3 | 138,000 |

| 4 | 128,000 |

| 5 | 120,000 |

| 6 | 117,000 |

| 7 | 114,000 |

| 8 | 111,000 |

| 9 | 108,000 |

| 10 | 105,000 |

B : The silhouette plot is a scatterplot connected by a line of number of clusters from 0 to 10 on the x-axis by silhouette index from -1.0 to 1.0 on the y-axis. The following table represents the data points on the graph :

| Number of clusters | Silhouette index |

|---|---|

| 2 | 0.28 |

| 3 | 0.22 |

| 4 | 0.12 |

| 5 | 0.12 |

| 6 | 0.12 |

| 7 | 0.12 |

| 8 | 0.12 |

| 9 | 0.12 |

| 10 | 0.12 |

Description for Figure 2

The figure overlaps a histogram and a density curve of diagonal proportion from 0.0 to 1.0 on the x-axis and by count/density from 0 to 15 on the y-axis. The histogram shows four bars centered at 0.80, 0.85, 0.90 and 0.95 with respective count/density of 12, 15, 11 and 7. The density curve shows a count/density of 0 from 0.0 to 0.7, peaks at 0.85 at a count/density of 7 and goes back to a count/density of 0 at a diagonal proportion of 1.0 in a bell-shape curve.

Individuals in Group B were predominantly female; were mostly taking prescription opioids, with less than one-quarter receiving OAT; had precarious to no employment; and had low to no income. Most had no police contacts. The primary differences between clusters B1 and B2 were age profiles, the proportion having fatal overdoses, income and the use of health care services. Individuals in Cluster B1 were primarily (71%) middle-aged (45 to 64 years), and most (97.9%) received social assistance at least once in the five years prior to the index opioid overdose and had low income. They were more than twice as likely to have experienced a fatal overdose as individuals in Cluster B2. Those in Cluster B2 were also predominantly middle-aged or older but were less likely to be aged 45-64 years (45.5%), had very low to no income, and had more frequent use of emergency department and hospital services (Table 3).

Finally, individuals in Group C were primarily younger males aged 24 to 44 years, were more likely to have experienced multiple overdoses, were medium to high users of emergency department and hospital services, and were largely unemployed and in receipt of social assistance in the five years prior to the index opioid overdose. Most had multiple contacts with police. The primary difference between clusters C1 and C2 was the use of prescription opioids; few (7.0%) of those in Cluster C1 were dispensed any prescription opioid medications in the two years prior to the index opioid overdose, while all of those in Cluster C2 were dispensed a prescription opioid medication, with the majority (89.2%) being dispensed opioids targeted as OAT (Table 3).

Discussion

Cluster analysis applied to multidimensional data enables an intersectional analysis of factors related to opioid overdose, producing profiles of distinct groups that can inform targeted prevention programs. The results of this study suggest a six-cluster solution with three groups composed of two clusters each. The resulting cluster profiles are supported by existing evidence from studies considering a broader range of characteristics among those experiencing opioid overdoses.

The identification of a group (Group A) consisting primarily of males employed in specific sectors (with approximately 27% in construction) was anticipated given existing evidence. Several U.S. studies have shown that use of opioids, including long-term use to address chronic musculoskeletal disorders, is associated with a higher risk of opioid use disorder.Note 28Note 29 Within Group A, however, clusters A1 and A2 differed in terms of employment, income, age and the prevalence of fatal overdose. Compared with individuals in Cluster A2, those in Cluster A1 were more stably employed, with a higher prevalence of working in construction (27.9% in A1 vs. 3.4% in A2); had higher incomes; had a higher prevalence of prescribed opioids and OAT; and had a greater prevalence of fatal overdose. The identification of a distinct Cluster A1 is consistent with recent research from Ontario that focused on fatal opioid toxicity among construction workers. It revealed that these workers were primarily male and were more likely to be aged 25 to 44 years, be employed, and have higher incomes and use of non-prescribed opioids, compared with those who experienced an opioid toxicity event but had no employment history in construction.Note 13

Higher incomes in Cluster A1 may have enabled more intense purchasing and consumption of opioids. Another study found links between higher income and exceeding thresholds for heavy alcohol consumption.Note 30 Greater rates of fatal overdose despite greater prevalence of OAT are partly what differentiated Cluster A1 from Cluster A2. The reported patterns among people in Cluster A1 are consistent with what might be expected given that recognized factors other than OAT and opioids prescribing—that were not measured in this study—may be driving higher fatality, such as the impact of the unpredictability of unregulated drugs.Note 13 Crabtree et al. (2020) showed prescribed opioids were found among only 2% of all people who died from drug toxicity between 2015 and 2017, whereas a high prevalence of non-prescribed, unregulated fentanyl and stimulants was found among the remaining decedents.Note 31 Furthermore, other work has shown that it is not the receipt of OAT per se that relates to fatal overdose, but rather OAT initiation or cessation that greatly increases risk of fatal opioid overdose.Note 32

The identification of Group B, composed primarily of middle- to older-aged females receiving prescription opioids, with a higher prevalence of OAT compared to Group A, or Cluster C1, higher use of health care services and low socioeconomic status, is supported by existing evidence primarily from the United States. Marchand et al. (2012) reported associations between low socioeconomic status and poor health outcomes among women who had engaged with OAT.Note 33 Similarly, a review conducted by Barbosa-Leiker et al. (2020) examining the epidemiology of opioid-related hospitalizations and death among women in the U.S. population concluded that women with substance use disorder were less likely to be employed; were significantly and disproportionately affected by low socioeconomic status and psychosocial needs; and faced housing issues.Note 34

The results of this study also highlight important sex differences as demonstrated by the distinct health care use profiles of groups A and B, composed primarily of males and females, respectively. Overall, females in Group B had a higher prevalence of emergency and hospital service use and of opioid prescriptions and OAT. Evidence suggests that women are twice as likely to be prescribed opioids than men.Note 31Note 33Note 35 Similarly, Milaney et al. (2021) reported that females with a diagnosis of a mental health or addiction condition were 28 times more likely to receive hospital care than males who had received such diagnoses.Note 36

The identification of clusters in Group C that were primarily composed of males younger than 45 years, with high unemployment and receipt of social assistance, and many with multiple contacts with police, is also consistent with existing evidence. Keen et al. (2021) concluded that, compared with British Columbia residents in general, people who had a non-fatal opioid toxicity event were about 10 years younger, predominantly male and more likely to have been incarcerated.Note 37 A U.S.-based study reported that the number of opioid-related police contacts increased in the 12 months following an initial drug-related contact.Note 38 This finding may reflect police behaviour change and/or greater engagement with survival drug trades (e.g., theft from cars) among people with a substance dependence, especially in the context of income-related marginalization such as that experienced by people in Group C. Important differences regarding use of OAT distinguished Cluster C1 from Cluster C2. Males in Cluster C1 had a lower rate of engagement with health services and of OAT receipt and a higher proportion of fatal opioid overdoses compared with males in Cluster C2. In general, the receipt of OAT is associated with lower mortality attributable to overdose.Note 37Note 39 More specifically, Krawczyk et al. (2021) found a similar relationship among justice-involved individuals (i.e., people with records of arrests, incarceration and community supervision). From a review of state justice records, the researchers observed that the majority of individuals (80%) were male and that those with opioid use disorder reduced their odds of fatal overdose by 60% when in receipt of agonist medications.Note 32Note 40

Despite the unique linked database and innovative analytical methods, the following study limitations are noted. While the BCOOAF provides comprehensive information regarding the characteristics of those who experienced opioid overdoses during the study period, several factors, such as Indigenous identity and housing status, were not available. Had such information been available, the results may have led to the identification of additional or different clusters. The chosen clustering algorithm (k-prototypes) requires random initialization, which could raise the question of the stability of its clustering results with respect to different initializations. To address this issue, a stability assessment was conducted. While the resulting profiles are reflective of the BCOOAF, the generalizability of the results to other cohorts experiencing opioid overdoses is unknown. The cluster analysis results could be validated on other cohorts in the future. Other limitations related to coverage of the data sources used to generate the BCOOAF are noted elsewhere.Note 23

The application of machine learning techniques to a multidimensional database enables an intersectional approach to study characteristics and system interactions of people experiencing opioid overdoses. This systematic identification of distinct clusters with specific profiles provides a more comprehensive understanding of people experiencing opioid overdoses, which hopefully can lead to more targeted interventions.

- Date modified: