Insights on Canadian Society

The role of social capital and ethnocultural characteristics in the employment income of immigrants over time

Archived Content

Information identified as archived is provided for reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It is not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards and has not been altered or updated since it was archived. Please "contact us" to request a format other than those available.

by Rose Evra and Abdolmohammad Kazemipur

Skip to text

Text begins

Start of text box

This study examines the impact of social capital and ethnocultural characteristics on the evolution of employment income of a cohort of immigrants who arrived in Canada in 2001, based on two linked datasets: the Longitudinal Survey of Immigrants to Canada (LSIC) and the Longitudinal Immigration Database (IMDB). The study examines the employment income of this cohort in their first 15 years in Canada (i.e., from 2002 to 2016).

- Among immigrants aged 25 to 54 who came to Canada in 2001, nearly half had relatives living in the country prior to their admission (44%), and almost two-thirds (63%) reported that they had friends living in the country prior to their admission.

- About 58% of immigrants from this cohort reported that nearly all friends made in the first six months after their admission were from their ethnic group, and 20% reported that most of their post-immigration friends were from outside their ethnic group. About 11% said that their post-immigration friends were equally divided between those who were from their own ethnic group and those who were not. The remainder (12%) did not make friends during their first six months in Canada.

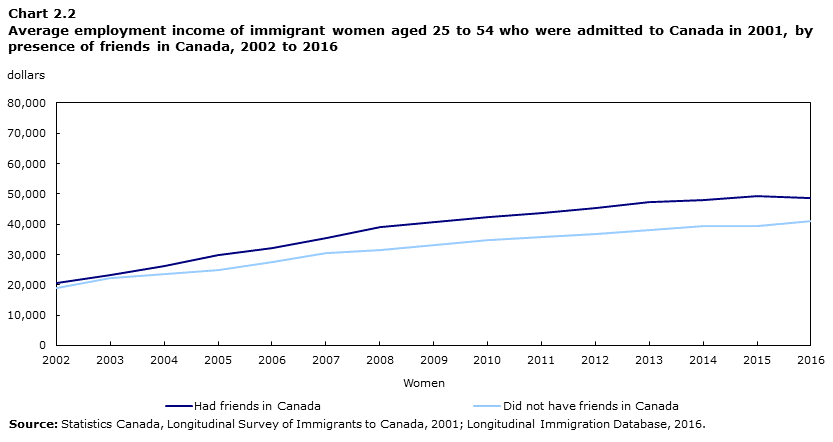

- Having friends was positively correlated with employment income. In 2002, immigrant women who had friends in Canada prior to their admission earned as much as those who did not have friends, but, by 2016, those who had friends in Canada prior to their admission earned about $7,000 more than those who did not have friends.

- Among immigrants, some groups designated as visible minorities (as defined under the Employment Equity Act) and some categories of religious affiliation consistently had lower employment incomes during the period (from 2002 to 2016). This suggests that the income disadvantage associated with some ethnocultural characteristics persists over time.

End of text box

Introduction

In recent years, the number of permanent residents admitted into Canada has been increasing, and reached record levels in 2018 when the government admitted 321,055 permanent residents.Note 1 In the 2016 Census, it was estimated that over 20% of Canadians were foreign born.Note 2 The Canadian immigration program admits individuals in three main categories: economic immigrants, immigrants sponsored by family and refugees. Immigrants admitted as principal applicants in the economic category are selected for their ability to contribute to the Canadian economy, whereas refugees are immigrants who are admitted based on a well-founded fear of returning to their home country. Most immigrants admitted to Canada in recent decades have been economic immigrants selected for their training and job skills.

The Longitudinal Immigration Database (IMDB)—a longitudinal database that combines immigrant admission data and taxation information—has been used in the past to examine how well immigrants do financially over time. An earlier study found that, relative to the average income of the Canadian-born population, the initial earnings of immigrant cohorts admitted in the early 2000s were lower than those who were admitted earlier.Note 3 However, despite that initial disadvantage, their average income levels caught up faster with those of the Canadian-born population (relative to earlier cohorts of immigrants). One limitation of the IMDB is that it does not include any information about the social relations of immigrants or their ethnic or cultural background, which may also affect incomes.

By integrating the IMDB with the Longitudinal Survey of Immigrants to Canada (LSIC), additional information can be retrieved on key immigrant characteristics that also influence employment income, such as social capital and ethnocultural characteristics.

Social capital refers to resources that are embedded in individuals’ social ties, such as friends, associations and communities. These resources can be converted into other social goods, including better education, better employment opportunities, improved health, safer societies and more functional democracies.Note 4 Social connections or affiliation with a civic association can help the larger economy by facilitating the flow of information in the market and reducing transaction costs. Social capital can also positively affect individuals’ economic performance by providing them with employment opportunities through informal channels and with work opportunities in the informal economy.

Social capital takes many different shapes, with different influences. One way to classify these differences is by separating “bonding” social capital from “bridging” social capital—sometimes called “strong” ties and “weak” ties. The former refers to ties between people with similar backgrounds and shared histories, and the latter refers to ties between people with different backgrounds, social statuses and social environments. In terms of economic performance, bonding social capital is good for “getting by,” while bridging social capital is good for “getting ahead.”Note 5 Bonding social capital tends to be more homogeneous and normally materializes through personal and family or friend connections, while bridging social capital is more diverse and materializes through formal associations and organizations.

Social capital is a particularly relevant factor in understanding the economic experiences of immigrants since the size, nature, density and consequences of their social connections are drastically different from those of the mainstream population.Note 6 For instance, immigrants experience a social capital deficit directly as a result of their migration and the uprooting that results from it.Note 7 In the words of another study, “immigrants tend to leave behind their social networks and other social relations that could otherwise help them in job acquisitions and occupational mobility.”Note 8

Similarly, ethnocultural characteristics can also be a factor in immigrants’ income. The sociopolitical environment of immigrant-receiving countries has undergone a drastic transformation in the past few decades. Some studies in the United States have pointed to rising intolerance directed at immigrants.Note 9 In Canada, a large number of studies have demonstrated the presence of biases in the job market against immigrant groups of certain ethnic and cultural backgrounds. The disadvantaged groups include those identified as visible minorities; religious minorities; and from certain source regions, such as the Middle East.Note 10

In this study, LSIC data were matched with IMDB data to examine the potential impact of social capital and ethnocultural characteristics on the income trajectory of immigrants across a 15 year period, for a cohort of immigrants aged 25 to 54 who came to Canada in 2001 (see the section Data sources, methods and definitions for additional details).

Nearly half of immigrants who came to Canada in 2001 had relatives living in the country prior to their admission

In the LSIC, various aspects of social capital are examined, including whether immigrants had any relatives living in Canada prior to admission, whether they had friends living in the country prior to admission, the characteristics of friends they made in Canada in their first six months after admission, and whether they contacted a work-related organization (for example, to get help in finding a job) or a non-work-related organization (such as ethnic or immigrant associations, or community organizations).

Nearly half (44%) of immigrants had relatives in the country prior to their admission, while a larger proportion (63%) reported that they had friends in the country prior to admission (Table 1). Women were more likely than men to have relatives who were living in the country prior to their admission in 2001 (48% compared with 41%), but were less likely than men to have pre-admission friends (59% compared with 66%).

Start of table 1

| Total | Men | Women | |

|---|---|---|---|

| percent | |||

| Relatives in Canada prior to admission | |||

| Had relatives living in Canada prior to admission | 44.3 | 41.0 | 47.9 |

| Did not have relatives living in Canada prior to admission | 55.7 | 59.0 | 52.1 |

| Friends in Canada prior to admission | |||

| Had friends living in Canada prior to admission | 63.0 | 66.4 | 59.3 |

| Did not have friends living in Canada prior to admission | 37.0 | 33.7 | 40.7 |

| Friends made in the first six months after admission in Canada | |||

| Most post-immigration friends are of different ethnicity than the immigrant | 19.5 | 19.9 | 19.0 |

| About half of post-immigration friends are of different ethnicity than the immigrant | 10.9 | 12.0 | 9.6 |

| Most post-immigration friends are of the same ethnicity as the immigrant | 57.5 | 57.7 | 57.3 |

| No friends made after six months | 12.2 | 10.4 | 14.2 |

| Contacted organizations in Canada | |||

| Contacted work-related organization within first six months after admission | 1.4 | 1.7 | 1.1 |

| Contacted non-work-related organization within first six months after admission | 20.7 | 21.6 | 19.8 |

| No contact with organization | 77.8 | 76.7 | 79.1 |

| Source: Statistics Canada, Longitudinal Survey of Immigrants to Canada, 2001; Longitudinal Immigration Database, 2016. | |||

End of table

The LSIC also includes information about the type of friends made in the first six months after migrating to Canada. About 58% of immigrants who were admitted in 2001 reported that the friends they made after they were admitted to Canada were mostly from their own ethnic group. About 20% of immigrants reported that most of the friends they made after migrating to Canada were from outside their ethnic group. Another 11% said that their post-immigration friends were equally divided between those who were from the same ethnic group and those who were from other ethnic groups. The remainder reported that they did not make any friends in their first six months after admission (12%). Results were similar between men and women.

Another way for immigrants to build social capital is to contact organizations, either for help in finding a job or for help with other aspects of life, such as finding a place to live or getting better access to services. In the first six months following admission, however, a relatively small proportion of immigrants reported having contacted a work-related organization (about 1%). Approximately one in five reported having participated in the activities or were members of a social organization that was unrelated to finding work, with small differences between men and women.

Ethnocultural variables present in the LSIC include visible minority status and religious affiliation (as reported by LSIC respondents six months after their admission in Canada). Results indicate that one-quarter of immigrants admitted in 2001 reported no religious affiliation—the highest result of all categories. About 18% of immigrants were Catholic, 18% were Muslim, 17% reported an Eastern religion (including Hindu, Sikh and Buddhist) and 12% were Protestant (Table 2). With regard to visible minority status, one-quarter of the immigrants admitted in 2001 were Chinese, one-quarter were South Asian or Southeast Asian, and one-fifth were not part of a visible minority group. The rest were distributed across other visible minority groups.

Start of table 2

| Total | Men | Women | |

|---|---|---|---|

| percent | |||

| Religion six month after admission to Canada | |||

| None | 25.7 | 25.4 | 26.0 |

| Catholic | 18.2 | 17.4 | 19.0 |

| Protestant | 11.9 | 11.4 | 12.4 |

| Orthodox | 8.1 | 7.6 | 8.7 |

| Muslim | 18.3 | 20.4 | 15.9 |

| Eastern religion | 16.9 | 16.6 | 17.3 |

| Other | 1.0 | 1.2 | 0.8 |

| Designated visible minority group | |||

| Not in a visible minority group | 20.1 | 20.2 | 20.0 |

| Filipino | 7.5 | 7.4 | 7.7 |

| Latin American | 2.6 | 2.2 | 3.0 |

| Chinese | 24.9 | 23.4 | 26.5 |

| Black | 4.5 | 4.7 | 4.4 |

| South and Southeast Asian | 25.5 | 26.0 | 24.8 |

| Arab | 5.9 | 7.0 | 4.7 |

| West Asian | 3.4 | 3.5 | 3.3 |

| Korean and Japanese | 4.6 | 4.5 | 4.7 |

| Multiple or not stated | 1.0 | 1.1 | 0.9 |

| Source: Statistics Canada, Longitudinal Survey of Immigrants to Canada, 2001; Longitudinal Immigration Database, 2016. | |||

End of table

Immigrants who did not make friends after their admission had lower levels of income than those who made friends

The research on the impact of social capital on immigrants’ economic performance has yielded mixed results, with some suggesting little to no impact and others even finding a negative effect.Note 11 More particularly, a previous study found that immigrants’ wages were negatively affected by the number of relatives in Canada and their proximity.Note 12 Conversely, recent studies have found that social capital has a positive impact on immigrants’ wages, beyond the contribution of their education or experience.Note 13

In this section, average employment income levels of immigrants from 2002 to 2016 are examined across various types of social capital.

The descriptive data shown in charts 1.1 and 1.2 indicate that, for both sexes, employment income was higher for immigrants without relatives in Canada at the time of their admission, by a margin of about $9,000 for men and $7,000 for women in 2016. For the most part, this result is because the profiles of immigrants with and without relatives in Canada differ. Immigrants admitted in the sponsored family categories, in particular, generally report lower earnings than economic immigrants.Note 14

Data table for Chart 1.1

| Men | Had relatives in Canada | Did not have relatives in Canada |

|---|---|---|

| dollars | ||

| 2002 | 31,400 | 33,600 |

| 2003 | 34,700 | 37,400 |

| 2004 | 38,100 | 41,800 |

| 2005 | 41,700 | 45,200 |

| 2006 | 44,800 | 50,200 |

| 2007 | 48,300 | 55,200 |

| 2008 | 50,300 | 57,700 |

| 2009 | 49,700 | 58,000 |

| 2010 | 52,300 | 60,600 |

| 2011 | 53,400 | 62,500 |

| 2012 | 54,900 | 65,300 |

| 2013 | 57,500 | 66,600 |

| 2014 | 58,200 | 67,800 |

| 2015 | 59,600 | 69,300 |

| 2016 | 60,900 | 70,200 |

| Source: Statistics Canada, Longitudinal Survey of Immigrants to Canada, 2001; Longitudinal Immigration Database, 2016. | ||

Data table for Chart 1.2

| Women | Had relatives in Canada | Did not have relatives in Canada |

|---|---|---|

| dollars | ||

| 2002 | 18,600 | 21,100 |

| 2003 | 21,400 | 24,200 |

| 2004 | 24,200 | 26,100 |

| 2005 | 26,300 | 29,100 |

| 2006 | 28,400 | 32,400 |

| 2007 | 31,300 | 35,500 |

| 2008 | 32,700 | 39,200 |

| 2009 | 34,500 | 40,600 |

| 2010 | 36,200 | 42,400 |

| 2011 | 36,400 | 44,300 |

| 2012 | 37,600 | 45,900 |

| 2013 | 39,200 | 47,900 |

| 2014 | 40,400 | 48,600 |

| 2015 | 41,300 | 49,000 |

| 2016 | 41,700 | 49,100 |

| Source: Statistics Canada, Longitudinal Survey of Immigrants to Canada, 2001; Longitudinal Immigration Database, 2016. | ||

Having friends, by contrast, was positively related to immigrants’ employment incomes. In their first six years in Canada, men reported similar levels of income, regardless of whether they had pre-admission friends (Chart 2.1). However, after 2008,Note 15 a gap started emerging, and by 2016, immigrant men with pre-admission friends earned more than $10,000 more than those who did not have friends in the country prior to their admission ($69,700 compared with $59,400). For women, the difference in income was noticeable after the second year of landing and grew over time. By 2016, women who had pre-admission friends earned more than $7,000 more than their counterparts who did not (Chart 2.2).

Data table for Chart 2.1

| Men | Had friends in Canada | Did not have friends in Canada |

|---|---|---|

| dollars | ||

| 2002 | 32,800 | 32,400 |

| 2003 | 36,700 | 35,400 |

| 2004 | 40,800 | 39,100 |

| 2005 | 44,400 | 42,400 |

| 2006 | 48,400 | 47,000 |

| 2007 | 52,800 | 51,300 |

| 2008 | 55,700 | 52,400 |

| 2009 | 56,300 | 51,100 |

| 2010 | 59,300 | 52,800 |

| 2011 | 61,200 | 53,700 |

| 2012 | 63,200 | 56,400 |

| 2013 | 65,800 | 56,700 |

| 2014 | 66,700 | 58,000 |

| 2015 | 68,900 | 58,100 |

| 2016 | 69,700 | 59,400 |

| Source: Statistics Canada, Longitudinal Survey of Immigrants to Canada, 2001; Longitudinal Immigration Database, 2016. | ||

Data table for Chart 2.2

| Women | Had friends in Canada | Did not have friends in Canada |

|---|---|---|

| dollars | ||

| 2002 | 20,500 | 19,000 |

| 2003 | 23,200 | 22,200 |

| 2004 | 26,300 | 23,500 |

| 2005 | 29,700 | 24,900 |

| 2006 | 32,300 | 27,700 |

| 2007 | 35,500 | 30,400 |

| 2008 | 39,000 | 31,500 |

| 2009 | 40,600 | 33,200 |

| 2010 | 42,500 | 34,800 |

| 2011 | 43,600 | 35,800 |

| 2012 | 45,200 | 36,900 |

| 2013 | 47,400 | 38,200 |

| 2014 | 48,100 | 39,500 |

| 2015 | 49,300 | 39,300 |

| 2016 | 48,500 | 41,100 |

| Source: Statistics Canada, Longitudinal Survey of Immigrants to Canada, 2001; Longitudinal Immigration Database, 2016. | ||

Incomes also appeared to grow faster for immigrants who had made friends in Canada six months after their admission. From 2002 to 2016, those who did not make any friends during their first six months after admission had employment income levels that were almost consistently lower than those who made friends.

The ethnic characteristics of friends also made a difference in employment income levels. Among men, for example, the incomes of those whose friends were from their own ethnic group were lower than the incomes of those who had friends from different ethnic groups (Chart 3.1). For example, those whose friends were mostly from different ethnic backgrounds earned $72,600 on average in 2016, compared with $64,400 among those whose friends were mostly of the same ethnicity, and $60,900 among those who did not make friends at all in their first six months after their admission.

Data table for Chart 3.1

| Men | Most friends were from a different ethnic group | About half of friends were from a different ethnic group | Most friends were from the same ethnic group | No friends made after six months |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| dollars | ||||

| 2002 | 40,100 | 37,300 | 29,500 | 29,500 |

| 2003 | 44,500 | 42,000 | 32,800 | 32,600 |

| 2004 | 46,100 | 45,200 | 37,700 | 36,400 |

| 2005 | 48,800 | 48,400 | 41,900 | 38,300 |

| 2006 | 53,900 | 54,000 | 45,700 | 42,600 |

| 2007 | 58,300 | 58,500 | 50,200 | 45,000 |

| 2008 | 61,700 | 61,900 | 52,200 | 45,200 |

| 2009 | 62,200 | 60,400 | 52,400 | 44,800 |

| 2010 | 63,300 | 63,700 | 55,100 | 48,400 |

| 2011 | 63,700 | 64,300 | 57,400 | 49,100 |

| 2012 | 66,300 | 66,100 | 59,500 | 52,600 |

| 2013 | 66,800 | 68,200 | 61,800 | 54,400 |

| 2014 | 68,600 | 67,000 | 63,000 | 55,700 |

| 2015 | 71,800 | 70,500 | 63,500 | 57,400 |

| 2016 | 72,600 | 69,700 | 64,400 | 60,900 |

| Source: Statistics Canada, Longitudinal Survey of Immigrants to Canada, 2001; Longitudinal Immigration Database, 2016. | ||||

Among women, all categories had similar earning levels at the beginning of the period (in 2002), but those who made friends in the first months after their admission eventually earned higher incomes than those who did not make any friends during their post-admission months (Chart 3.2). By 2016, women who did not make friends in the first six months after admission had an employment income that was slightly over $40,000, compared with income levels that varied between $46,000 and $48,000 for those who made friends after their admission. For women, the ethnicity of their post-admission friends did not seem to make a difference on employment income.

Data table for Chart 3.2

| Women | Most friends were from a different ethnic group | About half of friends were from a different ethnic group | Most friends were from the same ethnic group | No friends made after six months |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| dollars | ||||

| 2002 | 21,700 | 20,600 | 19,400 | 18,600 |

| 2003 | 26,100 | 23,600 | 21,900 | 21,400 |

| 2004 | 29,600 | 24,800 | 24,600 | 21,600 |

| 2005 | 31,200 | 28,500 | 27,400 | 23,800 |

| 2006 | 34,600 | 30,800 | 30,400 | 24,800 |

| 2007 | 35,600 | 37,000 | 33,300 | 28,600 |

| 2008 | 37,900 | 38,800 | 36,500 | 29,400 |

| 2009 | 40,200 | 42,000 | 37,800 | 30,200 |

| 2010 | 42,300 | 43,200 | 39,600 | 31,600 |

| 2011 | 43,200 | 43,400 | 40,900 | 32,800 |

| 2012 | 43,400 | 45,300 | 42,500 | 35,100 |

| 2013 | 44,000 | 45,900 | 44,900 | 37,100 |

| 2014 | 46,100 | 46,100 | 45,300 | 39,200 |

| 2015 | 47,100 | 47,200 | 45,700 | 39,900 |

| 2016 | 46,600 | 47,700 | 46,000 | 40,800 |

| Source: Statistics Canada, Longitudinal Survey of Immigrants to Canada, 2001; Longitudinal Immigration Database, 2016. | ||||

Although few immigrants contacted a work-related organization prior to their admission, those who did contact work-related organizations saw higher employment levels than those who contacted other types of organizations or those who did not contact any such organization. The results were similar for both men and women (charts 4.1 and 4.2).

Data table for Chart 4.1

| Men | Contacted work-related organization | Contacted other type of organization | Did not contact any organization |

|---|---|---|---|

| dollars | |||

| 2002 | 38,600 | 35,700 | 31,600 |

| 2003 | 43,300 | 38,800 | 35,400 |

| 2004 | 49,000 | 43,600 | 39,100 |

| 2005 | 58,600 | 45,800 | 42,700 |

| 2006 | 64,800 | 51,600 | 46,500 |

| 2007 | 73,900 | 57,500 | 50,300 |

| 2008 | 80,700 | 58,100 | 53,000 |

| 2009 | 77,500 | 57,600 | 53,100 |

| 2010 | 80,100 | 58,100 | 56,300 |

| 2011 | 85,800 | 59,300 | 57,800 |

| 2012 | 84,100 | 62,000 | 60,000 |

| 2013 | 83,100 | 62,700 | 62,300 |

| 2014 | 83,800 | 65,200 | 63,000 |

| 2015 | 85,400 | 66,400 | 64,500 |

| 2016 | 88,000 | 66,100 | 65,600 |

| Source: Statistics Canada, Longitudinal Survey of Immigrants to Canada, 2001; Longitudinal Immigration Database, 2016. | |||

Data table for Chart 4.2

| Women | Contacted work-related organization | Contacted other type of organization | Did not contact any organization |

|---|---|---|---|

| dollars | |||

| 2002 | 33,800 | 20,000 | 19,700 |

| 2003 | 37,400 | 22,900 | 22,600 |

| 2004 | 37,700 | 26,400 | 24,600 |

| 2005 | 35,200 | 29,200 | 27,300 |

| 2006 | 40,500 | 31,900 | 30,000 |

| 2007 | 49,500 | 35,000 | 32,800 |

| 2008 | 48,000 | 38,900 | 35,100 |

| 2009 | 47,500 | 37,600 | 37,500 |

| 2010 | 52,300 | 40,500 | 39,000 |

| 2011 | 55,700 | 41,900 | 40,000 |

| 2012 | 60,800 | 42,600 | 41,600 |

| 2013 | 62,000 | 44,000 | 43,500 |

| 2014 | 58,800 | 45,000 | 44,500 |

| 2015 | 55,900 | 45,200 | 45,300 |

| 2016 | 64,600 | 44,000 | 45,800 |

| Source: Statistics Canada, Longitudinal Survey of Immigrants to Canada, 2001; Longitudinal Immigration Database, 2016. | |||

Immigrants from groups identified as visible minorities persistently had lower employment income levels than those who were not part of a designated visible minority group

This section examines the association between two ethnocultural characteristics collected in LSIC—visible minority group and religious affiliation—and the long-term employment incomes of immigrants.

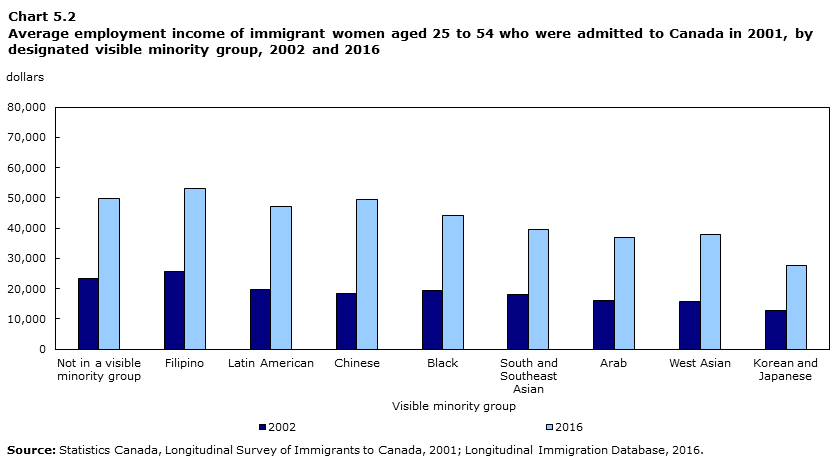

In 2002, at the beginning of the period, the incomes of immigrants who were part of designated visible minority groups were significantly lower than the incomes of those who were not part of a designated visible minority group (charts 5.1 and 5.2). Among men, for instance, immigrants not designated as visible minorities earned $42,900 in employment income, compared with $30,000 or less among immigrants who were Latin American ($29,000), Black ($27,100), West Asian ($26,400), Chinese ($25,800), Arab ($25,300), or Korean or Japanese ($22,300).

Data table for Chart 5.1

| Visible minority group | 2002 | 2016 |

|---|---|---|

| dollars | ||

| Not in a visible minority group | 42,900 | 76,500 |

| Filipino | 33,500 | 59,600 |

| Latin American | 29,000 | 72,000 |

| Chinese | 25,800 | 69,000 |

| Black | 27,100 | 52,700 |

| South and Southeast Asian | 34,700 | 70,000 |

| Arab | 25,300 | 54,900 |

| West Asian | 26,400 | 48,300 |

| Korean and Japanese | 22,300 | 43,000 |

| Source: Statistics Canada, Longitudinal Survey of Immigrants to Canada, 2001; Longitudinal Immigration Database, 2016. | ||

Data table for Chart 5.2

| Visible minority group | 2002 | 2016 |

|---|---|---|

| dollars | ||

| Not in a visible minority group | 23,400 | 49,900 |

| Filipino | 25,600 | 53,000 |

| Latin American | 19,800 | 47,200 |

| Chinese | 18,500 | 49,600 |

| Black | 19,300 | 44,300 |

| South and Southeast Asian | 18,000 | 39,500 |

| Arab | 16,100 | 36,800 |

| West Asian | 15,900 | 37,800 |

| Korean and Japanese | 12,900 | 27,600 |

| Source: Statistics Canada, Longitudinal Survey of Immigrants to Canada, 2001; Longitudinal Immigration Database, 2016. | ||

Although employment income levels increased in all visible minority groups over the period, the differences between visible minority groups were still significant 15 years later (in 2016). Among men, immigrants who were not part of a designated visible minority group earned $76,500 on average, more than any other group. Among visible minority groups, those who earned the least were those who reported being Korean or Japanese, at $43,000 on average, while those who reported being Latino American earned the most, at $72,000. Similar differences could be found for women as well. These results suggest that, although the incomes of groups designated as visible minorities do improve, differences in income levels persist over time.

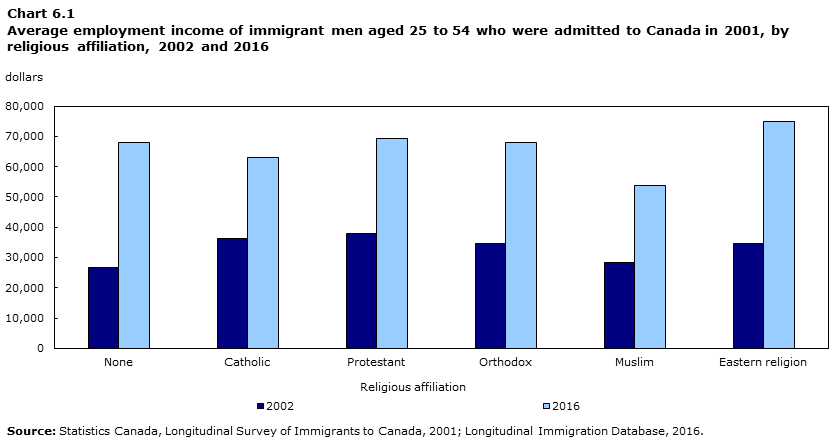

Income levels also varied across religious affiliation categories. Income levels rose for all groups between 2002 and 2016, in line with previous findings in the literature. As they stay in the country longer, immigrants add to their language, culture and job market knowledge, and expand their social networks. This has a positive impact on their employment income.

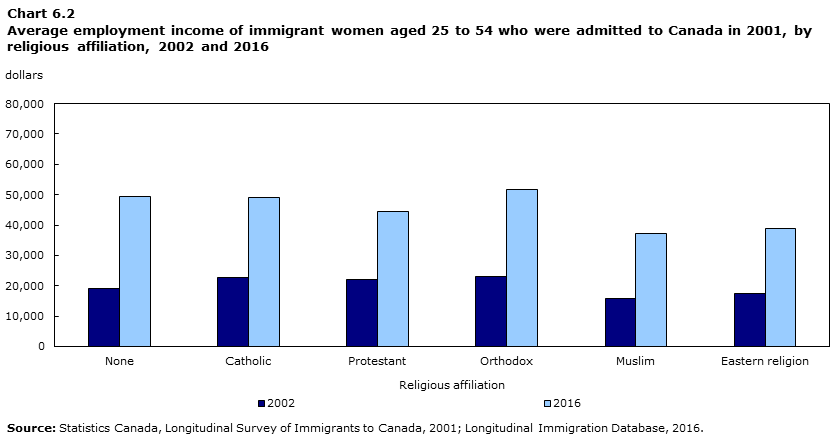

Differences across religious groups, however, remained consistent throughout the whole period covered, especially for men. In 2002 (and in 2003), Muslim men and men with no religious affiliation were almost tied for the lowest reported income, but Muslim men had the lowest income in all subsequent years.Note 16 By 2016, Muslim men earned $53,800 on average (Chart 6.1), compared with an average employment income of at least $63,000 for men in all other religious affiliation categories. Among women, Muslims and those who practised an Eastern religion consistently reported the lowest employment incomes, both in 2002 and in 2016 (Chart 6.2). Of note, in 2016, men who were affiliated to an Eastern religion had the highest level of employment income compared with other categories of religious affiliation.

Data table for Chart 6.1

| Men | 2002 | 2016 |

|---|---|---|

| dollars | ||

| None | 26,600 | 68,100 |

| Catholic | 36,300 | 63,200 |

| Protestant | 38,000 | 69,300 |

| Orthodox | 34,700 | 68,100 |

| Muslim | 28,300 | 53,800 |

| Eastern religion | 34,700 | 74,800 |

| Source: Statistics Canada, Longitudinal Survey of Immigrants to Canada, 2001; Longitudinal Immigration Database, 2016. | ||

Data table for Chart 6.2

| Women | 2002 | 2016 |

|---|---|---|

| dollars | ||

| None | 19,000 | 49,500 |

| Catholic | 22,800 | 49,100 |

| Protestant | 22,000 | 44,600 |

| Orthodox | 22,900 | 51,700 |

| Muslim | 15,800 | 37,300 |

| Eastern religion | 17,600 | 39,000 |

| Source: Statistics Canada, Longitudinal Survey of Immigrants to Canada, 2001; Longitudinal Immigration Database, 2016. | ||

Even after other factors are controlled for, the association between social capital and employment income remains significant

The results above are descriptive and do not control for other characteristics that also have an influence on employment income, such as education, knowledge of an official language, region of origin, or immigration category. To account for these factors, a regression analysis was used, the results of which are shown in Table 3. A positive coefficient suggests that those who belong to a specific category had higher incomes than those who were in the reference category during the period. By contrast, a negative coefficient suggests that those who were in the corresponding category had lower employment incomes than those who were in the reference category.

Start of table 3

| All | Men | Women | |

|---|---|---|---|

| coefficients | |||

| Social capital variables | |||

| Family members in Canada prior to admission | |||

| No relatives (ref.) | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable |

| Relatives living in Canada | 0.020 | -0.013 | 0.050 |

| Friends in Canada prior to admission | |||

| No friends (ref.) | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable |

| Pre-immigration friends in Canada | 0.056Note ** | 0.043 | 0.050Note * |

| Friends made in the first six months after admission in Canada | |||

| Most are from a different ethnic group (ref.) | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable |

| About half are from a different ethnic group | -0.037 | -0.047 | -0.058 |

| Most are from the same ethnic group | -0.099Note ** | -0.110Note ** | 0.000 |

| No friends made after six months | -0.070Note * | -0.097Note * | -0.012 |

| Organizations contacted | |||

| Did not contact any organization (ref.) | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable |

| Work-related organizationTable 3 Note 1 | 0.227Note ** | 0.245Note * | 0.179 |

| Other types of organizations | -0.015 | -0.001 | -0.045 |

| Ethnocultural variables | |||

| Visible minority group | |||

| Not in a visible minority group (ref.) | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable |

| Filipino | 0.073 | -0.015 | 0.160 |

| Latin American | -0.205Note * | -0.265Note * | -0.168 |

| Chinese | -0.205Note ** | -0.307Note ** | -0.092 |

| Black | -0.201Note ** | -0.292Note ** | -0.143 |

| South and Southeast Asian | -0.076 | -0.040 | -0.135 |

| Arab | -0.183Note ** | -0.109 | -0.314Note ** |

| West Asian | -0.046 | -0.067 | -0.017 |

| Korean and Japanese | -0.338Note ** | -0.437Note ** | -0.209Note * |

| Multiple or not stated | -0.057 | -0.169 | 0.096 |

| Religious affiliation | |||

| No religion | 0.016 | -0.002 | 0.045 |

| Catholic (ref.) | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable |

| Protestant | 0.087Note * | 0.137Note * | 0.061 |

| Orthodox | 0.044 | 0.100 | -0.008 |

| Muslim | -0.241Note ** | -0.202Note ** | -0.286Note ** |

| Eastern religion | 0.017 | 0.070 | -0.021 |

| Other | 0.152 | 0.216 | 0.047 |

... not applicable

Source: Statistics Canada, Longitudinal Survey of Immigrants to Canada, 2001; Longitudinal Immigration Database, 2016. |

|||

End of table

With respect to social capital variables, several results are worth noting. First, having relatives in Canada prior to admission was not significantly associated with employment income when other variables were taken into account, both for men and women. This is somewhat expected, as previous literature has suggested that the most rewarding social ties are “weak” ties (i.e., ties connecting people who are different from each other and that typically provide access to a wider variety of resources).Note 17

Second, among women, those who had friends in Canada prior to admission had higher incomes than those who did not. This relationship was not statistically significant for men. In fact, among men, friends made after their admission seemed to make more of a difference on income levels. Specifically, those who had no post-admission friends or whose post-admission friends were mostly from their own ethnic group had significantly lower incomes than those whose friends were mostly from a different ethnic group. These results are consistent with the descriptive results presented above.

Third, as was the case in the descriptive results, those who contacted a work-related organization prior to their admission had higher employment incomes than those who did not contact any organization in Canada, although that relationship was significant only for men. Contacting another type of organization, by contrast, did not have a significant impact on the employment incomes of men or women.

With regard to the two ethnocultural characteristics examined in the model, although nearly all coefficients for visible minority groups were negative—which indicates that visible minority groups, for the most part, had lower incomes than non-visible minorities—not all relationships were significant. Interestingly, being part of a designated visible minority group seemed to have more of an impact on employment income for men than for women. Among men, those who identified as Latin American, Chinese, Black, Korean or Japanese had significantly lower incomes than those who were not part of a designated visible minority group. Among women, those who identified as Arab, or as Korean or Japanese had significantly lower employment incomes than those who were not identified as part of a designated visible minority group.

Lastly, after other factors were accounted for, there was little relationship between religious affiliation and employment income. This runs contrary to the descriptive results, which found significant income differences between religious affiliation categories, and suggests that the relationship found in the descriptive results was caused by other factors, including belonging to a visible minority group. There was one exception to this rule—results show that employment incomes of Muslim men and women were significantly lower than the reference category (Catholics).Note 18

Conclusion

This study traced the income trajectory of a particular group of immigrants to Canada who were admitted in 2001 and surveyed through the LSIC. LSIC data were linked with IMDB data, which allowed for the examination of changes in immigrants’ employment income during the first 15 years of their lives in Canada. To the extent that data allowed, contributing factors to the observed income trends and changes in the nature of their contribution over time were examined. The focus was on two variable categories: those related to social capital and those related to the ethnocultural characteristics of the admitted immigrants.

The results from this study showed that not every form of social capital is positively correlated with employment income. For example, the presence of relatives does not seem to have much of an impact, but having friends does, especially post-immigration friends for men and pre-immigration friends for women. Combined, these results are consistent with the “strength of the weak ties” theory as a source of knowledge and connection with environments unfamiliar to immigrants. However, it is important to note that the benefits of social capital should not be limited to how much they influence income; there is an array of other benefits (social, psychological, cultural, etc.) that may be affected more visibly by these types of social capital. In addition, results associated with social capital may be associated with non-measured characteristics that can influence employment income, such as people skills.

Lastly, the results point to some ethnocultural biases in the Canadian labour market, reflected in the income penalties experienced by immigrants of certain ethno-religious backgrounds over a long period. Female immigrants with an Arab and Muslim background, in particular, are lagging behind others in terms of income, even after other factors related to their immigration admission categories, human capital, or demographic characteristics are controlled for. More research will be needed to understand why these groups experience long-term difficulties in the labour market. Also, a similar study for other cohort of immigrants could indicate if these results are specific to the 2001 cohort or applicable to immigrants in general.

Rose Evra is an analyst with the Social and Aboriginal Statistics Division at Statistics Canada, and Abdolmohammad Kazemipur is a professor of sociology and Chair of Ethnic Studies at the University of Calgary.

Start of text box

Data sources, methods and definitions

Data sources

The data used in this study come from two sources: the Longitudinal Immigration Database (IMDB) and the Longitudinal Survey of Immigrants to Canada (LSIC). The first source, the IMDB, includes immigrant admission records and annual tax records for immigrants admitted in Canada after 1979. The immigrant characteristics include age at admission, education at admission, source country, knowledge of official languages at admission, and immigration category (e.g., skilled worker, family or refugee). The tax records provide information on immigrants’ earnings since admission.

The second source, the LSIC, includes information from a longitudinal survey of a cohort of immigrants who arrived in 2001 and were surveyed three times (six months, two years and four years after arrival). The LSIC provides a wide range of demographic and social information on immigrants, including their ethnocultural characteristics and social capital.

The first LSIC wave had a sample size of about 12,000 immigrants aged 15 and over at admission. For the purpose of this study, we focused on respondents who were between the ages of 25 to 54—a sample of 8,085 respondents—to avoid biasing the results because of immigrants who were still getting their education and were not fully in the labour market, or who arrived close to retirement age.

This study is the first study in which the immigration data (from the LSIC, which includes data on social interaction and perception a few months and years after admission) are combined with the taxation data up to 15 years after admission.

Methodology

This paper uses a generalized linear model to examine the association between independent variables and annual employment. The dependent variable is the natural log of employment earnings. Employment income includes earnings and self-employment income. To exclude short-term, low-wage employment that does not signal strong labour market attachment, a minimum threshold of $1,000 was imposed. This method was also used in previous papers that studied employment participation of immigrants using administrative data.Note 19 The standard errors are adjusted using bootstrapped weights to account for the complex sampling design of the LSIC. Clustering effect was also taken into account since a given individual can have up to 15 records in the sample (i.e., every year between 2002 and 2016). All income figures are expressed in 2016 constant dollars.

In addition to social capital and ethnocultural variables, a quadratic term for age was included along with the original term since the effect of age is not linear and tends to diminish with time. A variable representing year since admission was added to the model to take into account time spent in the country. Other variables include immigrant admission categories, human capital variables (education, language skills and work experience) and regional variables (region of origin and region of residence).

Because of the complexity of the data structure, this study focused only on the main effects of the included variables and did not take into account the possible interaction effects between variables.

End of text box

- Date modified: