Insights on Canadian Society

Results from the 2016 Census: Commuting within Canada’s largest cities

Archived Content

Information identified as archived is provided for reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It is not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards and has not been altered or updated since it was archived. Please "contact us" to request a format other than those available.

by Katherine Savage

Skip to text

Text begins

Start of text box

Today, Insights on Canadian Society is releasing a study based on 2016 Census data. This study uses census information on place of work and main mode of commuting.

End of text box

Start of text box

Using data from the 1996 and 2016 Census of Population, this study examines the geographic location of jobs, people’s commute and how they have changed over time. The commuting patterns for Canada’s eight largest census metropolitan areas (CMAs)—Toronto, Montréal, Vancouver, Calgary, Ottawa–Gatineau, Edmonton, Québec and Winnipeg—are compared.

- Since 1996, jobs have been moving away from the city centre in large metropolitan areas. In Toronto, for example, the proportion of people working 25 kilometres (km) or more from the city centre increased from 20% in 1996 to 26% in 2016. As a result, the average distance from place of work to city centre increased in the eight largest CMAs.

- Over the past two decades, the number of car commuters in the city core declined in the eight largest CMAs. Montréal had the largest decline in the number of car users who worked within 5 km of the city centre, declining by 28% (representing 62,900 commuters).

- All eight CMAs have experienced changes in commuting patterns. The proportion of commuters doing the traditional commute (from a suburb to the city core) increased, as did the proportion of suburban commuters (within a suburb, or from one suburb to another suburb) and reverse commuters (from the city core to a suburb).

- Among traditional commuters, the proportion of public transit commuters increased in all eight CMAs. Montréal had the largest increase in the proportion of traditional commuters taking public transit to work, from 38% in 1996 to 55% in 2016. Vancouver and Toronto saw similar growth.

- Among those who work and live in the city core, the proportion of those who use active modes of transportation (such as walking and biking) increased—from 19% to 47% in Toronto, from 16% to 38% in Montréal, from 15% to 38% in Calgary, from 17% to 39% in Vancouver and from 22% to 42% in Ottawa-Gatineau.

End of text box

Introduction

This study looks at the geographic location of jobs and commuting patterns in Canada’s eight largest census metropolitan areas (CMAs): Toronto, Montréal, Vancouver, Calgary, Ottawa–Gatineau, Edmonton, Winnipeg, and Québec. The CMAs differ from one another with regard to age, size, growth rate, industrial structure, development policies, public transit access and geographic characteristics. These and other factors influence the location of jobs in the respective CMAs.Note This study uses data over a 20-year period to examine the evolving location of jobs in large CMAs and the implications for commuting, public transit and other transportation infrastructure such as pedestrian and bike lanes. Commuting to work makes up a large part of all journeys around the globe and significant transportation resources are invested to address this type of travelling.Note

The commuting flow of Canadians has undergone changes over time. Throughout the 20th century, employment became increasingly decentralized.Note Historically, most people lived near where they worked and jobs were located near the downtown core. There was a sharp growth in suburban jobs in the decades that followed the Second Word War, much of it because of the manufacturing sector, which was moving out of the city core to larger and less expensive spaces. As cities expanded after the Second World War, cars became more prevalent. More developed infrastructure and public transportation systems meant more people started living in the suburbs and commuting to the city core. In recent decades, however, evidence has emerged showing that some of this commuting flow has reversed—more people are living and working in the suburbs, living in the city core and commuting outside the core, or living in one suburb and commuting to another suburb.Note

Information on commuting flows is crucial for understanding the degree of interconnectedness among Canada’s communities. Commuting behaviour provides, among other things, an insight into local labour markets, residential housing markets and shortfalls in public transportation. Commuting also has economic implications for regional development, has environmental impacts, and has potential impacts on economic growth. The relationship and trade-offs between commuting, residential choice and migration are crucial for the development of transportation, housing policy and community development given concerns about work–life balance and sustainable communities.Note

In addition to the various economic aspects, the social aspects of commuting should also be considered. For some individuals, the regular commute to work is a routine activity that is of little concern. For others, however, it is a source of dissatisfaction, high stress levels and work–life imbalance.Note According to results from the 2010 General Social Survey, dissatisfaction was more common in larger population centres, where it was observed that frequent encounters with traffic congestion had a large impact on the likelihood of being dissatisfied with commuting times.

This study is divided into three parts. The first part examines the decentralization of jobs within CMAs over a period of 20 years (from 1996 to 2016). Although many jobs remain within the city core, employment located outside the city core is growing at a faster pace. The second part examines commuting distances and main modes of commuting in large metropolitan areas. The third part looks at the various types of commutes—within the city core; traditional and reverse; and within-suburban and between-suburban commutes—with a focus on changes in the main mode of commuting over time for each type of commute. These changes in commuting patterns have significant implications for transportation infrastructure, traffic congestion and air pollution. The study is based on data from the 1996 and 2016 censuses, which are using consistent definitions on commuting modes and place of work (see the Data sources, methods and definitions section for additional information).

Since 1996, jobs are moving away from the city centre

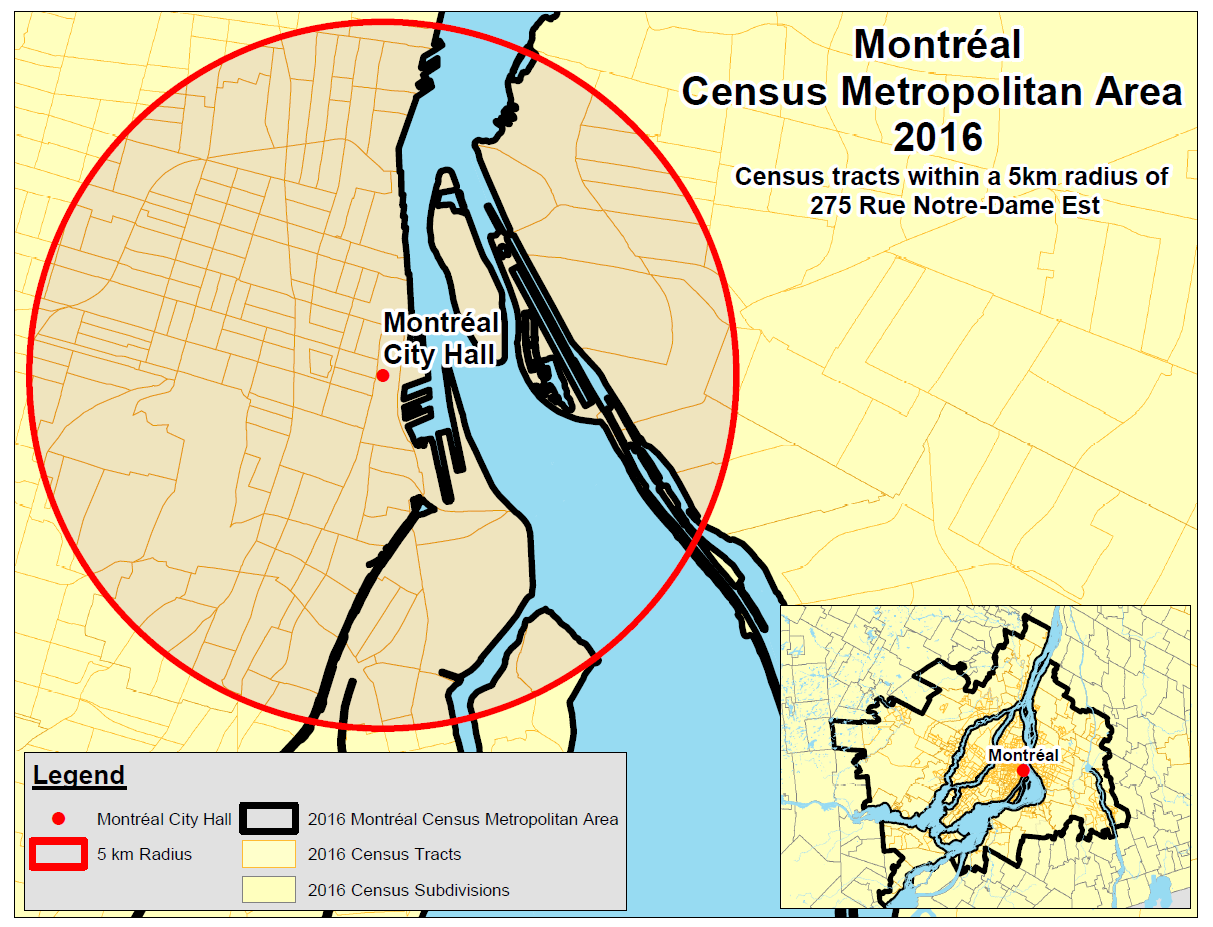

In this study, the city core is defined as census tracts that are located within 5 kilometres (km) of the city centre, identified in every city as the location of the city hall (the maps below show the Toronto, Montréal and Vancouver city centres).

Map 1 description

This map shows the census tracts that are located within a 5 km radius of the city centre in the Census Metropolitan Area of Toronto, located at 100 Queen Street West. The city centre is defined as the census tract where the city hall is located.

Map 2 description

This map shows the census tracts that are located within a 5 km radius of the city centre in the Census Metropolitan Area of Montréal, located at 275 Rue Notre-Dame Est. The city centre is defined as the census tract where the city hall is located.

Map 3 description

This map shows the census tracts that are located within a 5 km radius of the city centre in the Census Metropolitan Area of Vancouver, located at 453 W 12th Ave. The city centre is defined as the census tract where the city hall is located.

In 2016, the CMA with the highest share (48%) of workers in its city core was Winnipeg, followed by Ottawa–Gatineau (46%). In the three largest CMAs, a smaller proportion worked within the city core: 23% in Toronto, 26% in Montréal and 30% in Vancouver (Table 1).

Start of table 1

| Census metropolitan area | Distance | Employment | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 to 4.9 km | 5 to 9.9 km | 10 to 14.9 km | 15 to 19.9 km | 20 to 24.9 km | 25 km or more | ||

| percent | number | ||||||

| 2016 | |||||||

| Toronto | 23.1 | 7.5 | 11.5 | 14.8 | 17.4 | 25.7 | 2,566,700 |

| Montréal | 26.1 | 21.1 | 19.1 | 11.3 | 6.8 | 15.6 | 1,757,100 |

| Vancouver | 29.7 | 24.0 | 10.4 | 8.8 | 10.5 | 16.8 | 1,006,600 |

| Calgary | 38.3 | 37.3 | 14.1 | 5.8 | 1.1 | 3.5 | 587,300 |

| Ottawa–Gatineau | 45.5 | 26.3 | 9.6 | 8.0 | 5.1 | 5.5 | 595,900 |

| Edmonton | 30.2 | 35.2 | 19.0 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 10.5 | 553,700 |

| Québec | 37.3 | 40.7 | 12.7 | 4.9 | 3.4 | 1.1 | 375,700 |

| Winnipeg | 47.5 | 40.4 | 9.1 | 1.1 | 0.8 | 1.0 | 344,300 |

| 1996 | |||||||

| Toronto | 22.7 | 10.1 | 14.0 | 18.8 | 14.6 | 19.7 | 2,165,800 |

| Montréal | 27.8 | 24.7 | 20.6 | 8.5 | 6.3 | 12.1 | 1,613,500 |

| Vancouver | 32.7 | 25.8 | 10.2 | 10.0 | 8.4 | 12.8 | 854,200 |

| Calgary | 49.4 | 39.4 | 7.5 | 1.1 | 0.0 | 2.7 | 416,600 |

| Ottawa–Gatineau | 51.8 | 26.4 | 8.7 | 5.5 | 3.1 | 4.5 | 513,800 |

| Edmonton | 38.2 | 39.9 | 9.7 | 1.2 | 2.2 | 8.8 | 411,800 |

| Québec | 42.9 | 37.4 | 11.3 | 2.9 | 4.2 | 1.4 | 328,900 |

| Winnipeg | 54.1 | 36.9 | 7.3 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.8 | 328,300 |

Source: Statistics Canada, Census of Population, 1996 and 2016. |

|||||||

End of table

In most CMAs, the proportion of people working in the city core has declined and the proportion of people working outside the city core has increased. Calgary saw the largest proportional decline in workers whose job was located within 5 km of the city centre, decreasing 11 percentage points (from 49% to 38%) since 1996. The second largest decrease in workers who worked within 5 km of the city centre (a decline of 8 percentage points, to 30%) was seen in Edmonton. In the eight CMAs, a majority of workers were located outside the city core in 2016.

From 1996 to 2016, there was an increase in the proportion of commuters who worked 25 km or more from the city centre in seven of the eight CMAs, with the exception of Québec. In 2016, Toronto had the highest proportion of workers with jobs 25 km or more from the city centre at 26%, increasing 6 percentage points since 1996.

It is not only the proportion of jobs located outside the city core that is increasing, but also the proportion of commuters whose residence is located outside the city core. This is related to the preference for single-family homes on larger and more affordable lots, located further away from the city core. From 1996 to 2016, there was an increase in the proportion of workers who lived 25 km or more from the city centre in all eight CMAs (Table 2). Toronto had the highest increase in the proportion of workers living 25 km or more from the city centre, increasing from 29% in 1996 to 45% in 2016. In addition, there was a decrease in the proportion of workers whose residence was located within 5 km of the city centre across all eight CMAs. The largest decrease (a decline of 16 percentage points) was seen in Calgary, followed by Ottawa–Gatineau (a decline of 10 percentage points).

Start of table 2

| Census metropolitan area | Distance | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 to 4.9 km | 5 to 9.9 km | 10 to 14.9 km | 15 to 19.9 km | 20 to 24.9 km | 25 km or more | |

| percent | ||||||

| 2016 | ||||||

| Toronto | 9.6 | 10.8 | 11.4 | 10.8 | 12.1 | 45.4 |

| Montréal | 9.9 | 23.2 | 16.7 | 10.0 | 11.9 | 28.4 |

| Vancouver | 19.2 | 18.5 | 13.2 | 9.5 | 13.9 | 25.8 |

| Calgary | 14.1 | 26.3 | 29.7 | 17.4 | 2.4 | 10.1 |

| Ottawa–Gatineau | 15.3 | 25.8 | 16.1 | 16.9 | 7.8 | 18.1 |

| Edmonton | 15.2 | 27.2 | 31.6 | 7.7 | 3.9 | 14.6 |

| Québec | 20.0 | 29.0 | 24.1 | 11.5 | 3.6 | 11.8 |

| Winnipeg | 28.4 | 39.3 | 20.7 | 1.6 | 2.4 | 7.6 |

| 1996 | ||||||

| Toronto | 11.7 | 13.0 | 14.7 | 17.2 | 14.0 | 29.4 |

| Montréal | 15.7 | 25.8 | 19.0 | 12.1 | 8.8 | 18.5 |

| Vancouver | 25.3 | 21.6 | 17.1 | 9.9 | 8.9 | 17.3 |

| Calgary | 30.5 | 37.4 | 19.6 | 4.3 | 0.4 | 7.8 |

| Ottawa–Gatineau | 25.5 | 35.6 | 13.6 | 10.2 | 4.2 | 10.9 |

| Edmonton | 24.8 | 37.5 | 19.9 | 3.5 | 2.5 | 12.0 |

| Québec | 23.4 | 41.2 | 19.5 | 6.4 | 4.1 | 5.4 |

| Winnipeg | 36.8 | 41.9 | 11.8 | 2.6 | 1.8 | 5.1 |

Source: Statistics Canada, Census of Population, 1996 and 2016. |

||||||

End of table

In most CMAs, the number of workers in the city core increased despite proportional declines in the number of jobs situated in the city core, due to the overall employment growth (Table 3). There were two exceptions: city core employment fell by 14,100 in Winnipeg over this 20-year period, and fell by 1,200 in Québec. Approximately 25% of all new jobs in Toronto from 1996 to 2016 were located in the city core. This is different from the other CMAs, which had little growth in the city core.

Start of table 3

| Census metropolitan area | Distance is less than 5 kilometres | Distance is 5 kilometres or more | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1996 | 2016 | Change in number of jobs, 1996 to 2016 | 1996 | 2016 | Change in number of jobs, 1996 to 2016 | |

| percent | number | percent | number | |||

| Toronto | 22.7 | 23.1 | 102,000 | 77.3 | 76.9 | 298,800 |

| Montréal | 27.8 | 26.1 | 11,200 | 72.2 | 73.9 | 132,500 |

| Vancouver | 32.7 | 29.7 | 18,900 | 67.3 | 70.4 | 133,500 |

| Calgary | 49.4 | 38.3 | 19,500 | 50.6 | 61.7 | 151,200 |

| Ottawa–Gatineau | 51.8 | 45.5 | 5,300 | 48.3 | 54.5 | 76,800 |

| Edmonton | 38.2 | 30.2 | 10,200 | 61.8 | 69.8 | 131,700 |

| Québec | 42.9 | 37.3 | -1,200 | 57.1 | 62.7 | 48,000 |

| Winnipeg | 54.1 | 47.5 | -14,100 | 45.9 | 52.5 | 30,200 |

Source: Statistics Canada, Census of Population, 1996 and 2016. |

||||||

End of table

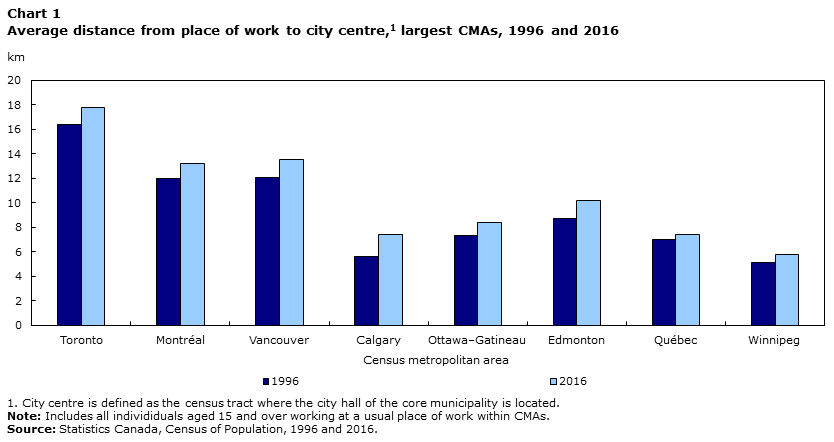

Chart 1 shows the average distance from workers’ place of work to the city centre for 1996 and 2016. The land area of CMAs should be taken into consideration when comparing the average distances among the various CMAs (see Table A1 in the Supplementary information section for details). Edmonton has the largest land area of all CMAs, at 9,400 km2 while Vancouver has the smallest at 2,900 km2.

Data table for Chart 1

| Census metropolitan area | Average distance | |

|---|---|---|

| 1996 | 2016 | |

| kilometres | ||

| Toronto | 16.4 | 17.8 |

| Montréal | 12.0 | 13.2 |

| Vancouver | 12.1 | 13.5 |

| Calgary | 5.6 | 7.4 |

| Ottawa–Gatineau | 7.3 | 8.4 |

| Edmonton | 8.7 | 10.2 |

| Québec | 7.0 | 7.4 |

| Winnipeg | 5.1 | 5.8 |

|

1. City centre is defined as the census tract where the city hall of the core municipality is located. Note: Includes all individiduals aged 15 and over working at a usual place of work within CMAs. Source: Statistics Canada, Census of Population, 1996 and 2016. |

||

In 2016, Toronto had the greatest average distance (17.8 km) from place of work to city centre, followed by Vancouver (13.5 km). Both CMAs had an increase of 1.4 km from 1996 to 2016. The decentralization of jobs is related to both population and employment growth in the respective CMAs. As employment within CMAs grows, there is a need to expand job locations to outside the city core. This creates more jobs and places of residence outside the city core.

Since 1996, the average distance from workers’ place of work to the city centre has increased in all eight CMAs. Calgary had the greatest increase in distance from place of work to city centre (by 1.8 km on average).

Toronto commuters are travelling the greatest distances to work

For some people, the time spent commuting provides an opportunity to get some work done or engage in a leisure activity, such as reading a book. For others however, morning and evening commutes corresponds to higher stress levels.Note Increased commuting distances, associated with road traffic congestion, are also likely to raise levels of vehicular carbon emissions. When analyzing commuting distances, it is important to bear in mind that many factors influence the actual distance that individuals travel, such as available transportation routes, construction zones and road closures. The calculation of distance available using census data is the straight-line distance from place of residence to place of work, which might underestimate the actual distance travelled.

In all eight CMAs, more than 60% of workers commuted more than 5 km to get to work, and for many the commute was 25 km or more (Table 4). In Toronto, nearly 1 in 5 workers travelled at least 25 km to work. In 2016, Toronto had the greatest median distance at 10.5 km, followed by Ottawa–Gatineau at 9.2 km. The CMAs with the smallest median distance were Winnipeg (6.6 km) followed by Québec (7.5 km). For all eight CMAs, the highest proportions of commuters were travelling between 5 km and 14.9 km to get to work.

Start of table 4

| Census metropolitan area | Commuters | Commuting distance | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Less than 5 km | 5 to 14.9 km | 15 to 24.9 km | 25 km or more | Median distance | ||

| number | percent | km | ||||

| 2016 | ||||||

| Toronto | 2,566,700 | 27.1 | 36.4 | 17.1 | 19.4 | 10.5 |

| Montréal | 1,757,100 | 32.2 | 39.1 | 16.9 | 11.8 | 8.6 |

| Vancouver | 1,006,600 | 35.5 | 40.1 | 15.3 | 9.1 | 7.6 |

| Calgary | 587,300 | 29.0 | 47.4 | 15.9 | 7.6 | 9.0 |

| Ottawa–Gatineau | 595,900 | 29.6 | 39.7 | 17.2 | 13.5 | 9.2 |

| Edmonton | 553,700 | 30.8 | 45.4 | 13.8 | 9.9 | 8.6 |

| Québec | 375,700 | 34.9 | 45.9 | 10.3 | 8.9 | 7.5 |

| Winnipeg | 344,300 | 37.8 | 48.9 | 6.4 | 6.8 | 6.6 |

| 1996 | ||||||

| Toronto | 2,165,800 | 27.2 | 37.6 | 17.3 | 18.0 | 10.1 |

| Montréal | 1,613,500 | 32.9 | 39.5 | 16.1 | 11.5 | 8.4 |

| Vancouver | 854,200 | 33.1 | 40.3 | 16.3 | 10.3 | 7.9 |

| Calgary | 416,600 | 31.2 | 53.2 | 8.0 | 7.6 | 7.7 |

| Ottawa–Gatineau | 513,800 | 31.8 | 41.3 | 13.5 | 13.4 | 8.3 |

| Edmonton | 411,800 | 33.2 | 45.9 | 10.5 | 10.5 | 7.7 |

| Québec | 328,900 | 37.3 | 46.4 | 9.1 | 7.3 | 7.0 |

| Winnipeg | 328,300 | 39.6 | 48.5 | 5.0 | 6.8 | 6.3 |

|

Note: Includes all individiduals aged 15 and over working at a usual place of work within CMAs. Source: Statistics Canada, Census of Population, 2016. |

||||||

End of table

The median distance from residence to place of work increased in seven of the eight CMAs, with the exception of Vancouver, where it decreased from 7.9 km in 1996 to 7.6 km in 2016. Vancouver is the only CMA where the proportion of commuters who live less than 5 km from their place of work has increased since 1996 (from 33% in 1996 to 36% in 2016), a result that may be related to the rapid condominium development that took place in the city core over the period.

The suburbanization of jobs and workers, and longer distances to and from work, can be a challenge for cities that are trying to increase public transit take-up rates and promote active modes of transportation. The next section provides a profile of commuters grouped according to the distance from their place of work to the city centre and their main mode of commuting to work.

Canadians working within 5 kilometres of the city centre were more likely to use public transit

The main mode of commuting that people use to get to work depends on a number of factors, including where they live and work, cost, availability and personal preference. In 2016, most people still commuted to work by car as either a driver or a passenger (78%).Note However, over the years, the number of people using alternative modes of transportation such as public transit, walking or cycling to get to work increased.

Across Canada, increasing public transit use is a central goal in transportation planning. This goal is in response to several pressing needs, which include alleviating road congestion and decreasing emissions. Both regional and municipal governments are investing substantially in new transit infrastructure to encourage car drivers to switch to public transit for their daily commute.Note In 2016, a greater proportion took public transit than ever before.Note

Commuters who worked further away from the city centre were more likely to use a car to go to work than those who worked closer. Nevertheless, in Winnipeg, 72% of those who worked less than 5 km from the city centre were commuted by car, the highest proportion of all eight CMAs (Table 5). Toronto had the lowest proportion of car commuters among those who worked less than 5 km from the city centre, at 25%. Access to public transportation and to parking spaces is not necessarily the same across CMAs for people who work in the city core.

Start of table 5

| Main mode of commuting | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Car, truck or van | Public transit | Walk | Bicycle | Other method | |

| percent | |||||

| Toronto | |||||

| 0 to 4.9 km | 24.9 | 58.1 | 11.9 | 4.2 | 1.0 |

| 5 to 9.9 km | 57.2 | 31.6 | 8.1 | 1.9 | 1.3 |

| 10 to 14.9 km | 68.7 | 26.1 | 3.8 | 0.5 | 0.9 |

| 15 to 19.9 km | 80.5 | 16.0 | 2.4 | 0.4 | 0.7 |

| 20 to 24.9 km | 86.7 | 10.7 | 1.8 | 0.3 | 0.6 |

| 25 km or more | 88.7 | 6.4 | 3.5 | 0.5 | 1.0 |

| Total | 67.7 | 24.7 | 5.3 | 1.4 | 0.9 |

| Montréal | |||||

| 0 to 4.9 km | 35.9 | 51.4 | 7.6 | 4.4 | 0.7 |

| 5 to 9.9 km | 66.0 | 24.0 | 7.1 | 2.2 | 0.7 |

| 10 to 14.9 km | 82.7 | 12.6 | 3.3 | 0.8 | 0.6 |

| 15 to 19.9 km | 87.7 | 8.9 | 2.3 | 0.6 | 0.5 |

| 20 to 24.9 km | 87.0 | 6.6 | 4.5 | 0.9 | 1.0 |

| 25 km or more | 90.9 | 2.5 | 4.7 | 0.9 | 1.0 |

| Total | 69.1 | 22.8 | 5.4 | 2.0 | 0.7 |

| Vancouver | |||||

| 0 to 4.9 km | 42.4 | 38.2 | 13.0 | 5.2 | 1.2 |

| 5 to 9.9 km | 71.3 | 20.6 | 5.1 | 2.1 | 1.0 |

| 10 to 14.9 km | 75.8 | 16.4 | 4.7 | 1.9 | 1.2 |

| 15 to 19.9 km | 78.4 | 14.7 | 5.3 | 0.8 | 0.9 |

| 20 to 24.9 km | 81.6 | 11.7 | 5.0 | 0.6 | 1.0 |

| 25 km or more | 87.5 | 5.7 | 4.8 | 0.8 | 1.2 |

| Total | 67.6 | 21.4 | 7.3 | 2.5 | 1.1 |

| Calgary | |||||

| 0 to 4.9 km | 62.9 | 25.8 | 7.6 | 2.9 | 0.9 |

| 5 to 9.9 km | 84.6 | 10.4 | 3.2 | 1.0 | 0.7 |

| 10 to 14.9 km | 86.4 | 7.9 | 3.6 | 0.6 | 1.5 |

| 15 to 19.9 km | 85.4 | 7.3 | 4.7 | 0.6 | 2.0 |

| 20 to 24.9 km | 88.3 | 5.5 | 3.8 | 0.5 | 1.9 |

| 25 km or more | 90.8 | 1.3 | 5.4 | 1.2 | 1.4 |

| Total | 76.8 | 15.4 | 5.1 | 1.6 | 1.0 |

| Ottawa–Gatineau | |||||

| 0 to 4.9 km | 57.0 | 29.8 | 8.8 | 3.7 | 0.7 |

| 5 to 9.9 km | 81.4 | 11.8 | 4.6 | 1.5 | 0.7 |

| 10 to 14.9 km | 82.5 | 10.7 | 4.5 | 1.2 | 1.1 |

| 15 to 19.9 km | 84.2 | 9.3 | 4.3 | 1.1 | 1.2 |

| 20 to 24.9 km | 87.3 | 7.0 | 3.7 | 1.1 | 1.0 |

| 25 km or more | 91.1 | 1.3 | 5.4 | 0.8 | 1.3 |

| Total | 71.5 | 18.9 | 6.5 | 2.4 | 0.8 |

| Edmonton | |||||

| 0 to 4.9 km | 67.3 | 23.5 | 6.6 | 2.1 | 0.6 |

| 5 to 9.9 km | 87.0 | 9.0 | 2.5 | 0.7 | 0.8 |

| 10 to 14.9 km | 87.8 | 6.9 | 3.5 | 0.7 | 1.1 |

| 15 to 19.9 km | 93.7 | 1.6 | 2.5 | 0.4 | 1.9 |

| 20 to 24.9 km | 93.5 | 0.8 | 3.9 | 0.5 | 1.3 |

| 25 km or more | 90.9 | 3.3 | 4.1 | 0.6 | 1.1 |

| Total | 82.0 | 12.0 | 4.1 | 1.1 | 0.9 |

| Québec | |||||

| 0 to 4.9 km | 70.1 | 17.4 | 10.2 | 1.8 | 0.5 |

| 5 to 9.9 km | 84.6 | 10.0 | 3.8 | 1.1 | 0.6 |

| 10 to 14.9 km | 86.9 | 5.8 | 5.3 | 1.0 | 1.1 |

| 15 to 19.9 km | 91.2 | 1.5 | 5.2 | 0.8 | 1.3 |

| 20 to 24.9 km | 94.3 | 0.5 | 3.4 | 0.7 | 1.1 |

| 25 km or more | 89.6 | 0.7 | 7.5 | 0.3 | 1.9 |

| Total | 80.2 | 11.4 | 6.5 | 1.3 | 0.7 |

| Winnipeg | |||||

| 0 to 4.9 km | 72.2 | 19.0 | 5.9 | 2.2 | 0.7 |

| 5 to 9.9 km | 84.8 | 9.8 | 3.3 | 1.3 | 0.9 |

| 10 to 14.9 km | 81.3 | 10.7 | 5.2 | 1.4 | 1.3 |

| 15 to 19.9 km | 94.1 | 2.0 | 2.2 | 0.8 | 1.0 |

| 20 to 24.9 km | 95.5 | 0.3 | 3.6 | 0.3 | 0.4 |

| 25 km or more | 91.5 | 0.7 | 6.6 | 0.6 | 0.6 |

| Total | 78.8 | 14.0 | 4.7 | 1.7 | 0.8 |

|

Note: Includes all individiduals aged 15 and over working at a usual place of work within CMAs. Source: Statistics Canada, Census of Population, 2016. |

|||||

End of table

A notable finding on the main mode of commuting is that, in the three largest CMAs (Toronto Montréal and Vancouver), there were proportionally fewer car commuters and proportionally more public transportation users. Toronto had the highest proportion of public transit users among those who worked within 5 km of the city centre (58%) followed by Montréal (51%). Vancouver had the highest proportion of commuters working within 5 km of the city centre who walked (13%) or cycled (5%). Toronto came in a close second, with 12% and 4%, respectively.

In large CMAs such as Toronto, Montréal and Vancouver, the use of public transit among those whose place of work was 5 km to 9.9 km away from the city centre was still relatively high, at 32% in Toronto, 24% in Montréal, and 21% in Vancouver. Owing to their large populations and geographies, the three largest CMAs in the country have expanded public transit systems and, therefore, commuters who live away from the city centre may contemplate alternatives to car use. In smaller CMAs, by contrast, car use was predominant among those whose job was at least 5 km away from the city centre.

In the eight largest CMAs, there were fewer people going to work by car in the city core

With more and more workers having job locations further away from the city core, the main modes of commuting they use to get to work are changing. According to a previous study, “the car encourages low-density, sprawled cities, but the costs imposed are three-fold: lost labour income from commuting time, high automobile operating costs and reduced environmental quality.”Note

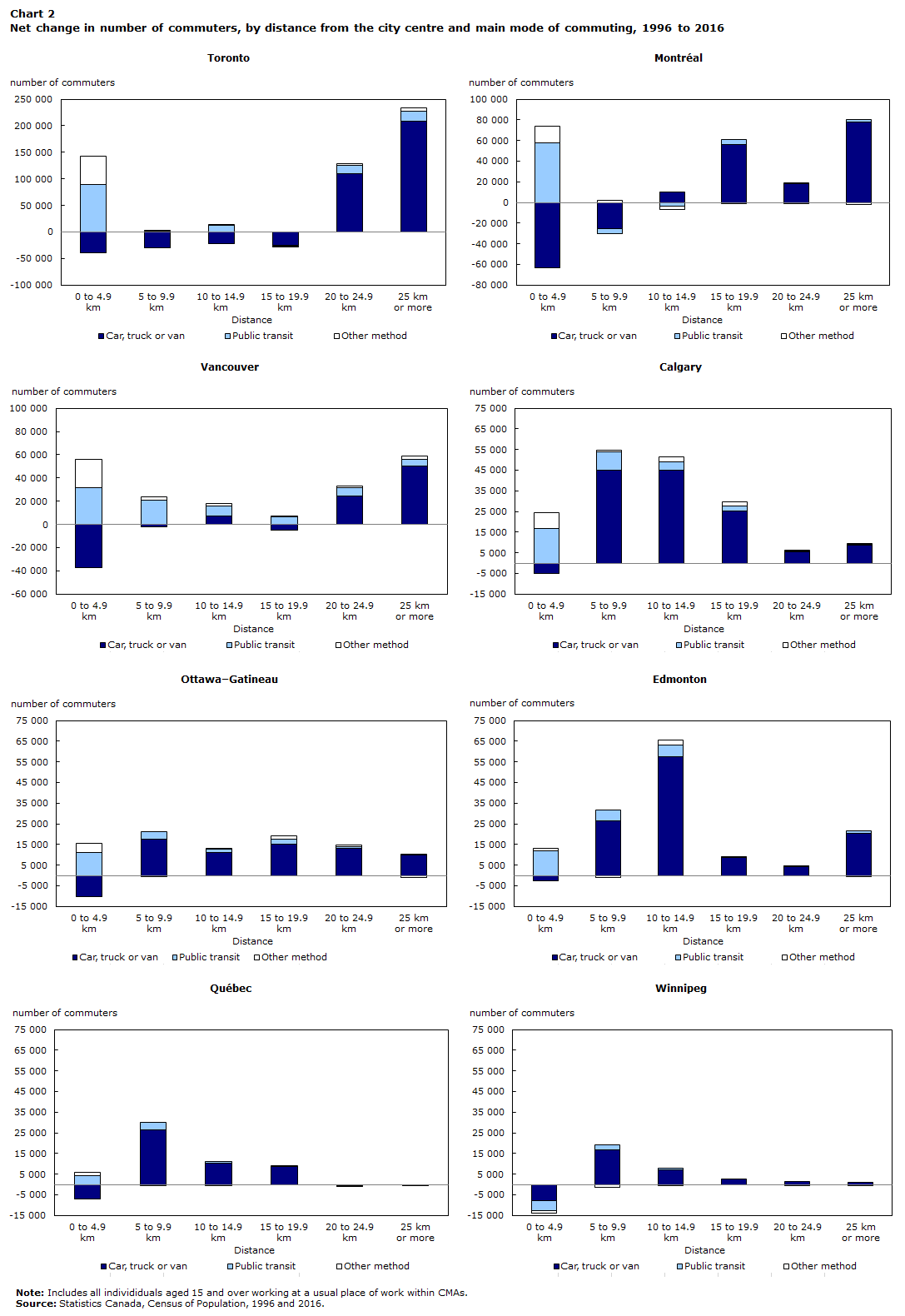

While job locations are becoming more decentralized, car use is on the decline and public transit popularity is increasing among those who worked in the city core.

In all eight CMAs, there were fewer people going to work by car in the city core in 2016 compared with 1996. Montréal was the CMA with the largest decrease in the number of workers going to work by car in the city core during this 20-year period, declining by 62,900 (28%). In contrast, 58,100 additional workers used public transit to get to their place of work in the Montréal city core between 1996 and 2016 (chart 2).

Data table for Chart 2

| Distance of job from city centre | Car, truck or van | Public transit | Other method |

|---|---|---|---|

| number of commuters | |||

| Toronto | |||

| 0 to 4.9 km | -39,900 | 89,700 | 52,300 |

| 5 to 9.9 km | -29,400 | 1,100 | 2,200 |

| 10 to 14.9 km | -22,700 | 12,200 | 1,300 |

| 15 to 19.9 km | -25,800 | -700 | -1,700 |

| 20 to 24.9 km | 109,700 | 16,100 | 2,700 |

| 25 km or more | 208,400 | 18,900 | 6,500 |

| Montréal | |||

| 0 to 4.9 km | -62,900 | 58,100 | 16,000 |

| 5 to 9.9 km | -25,000 | -5,400 | 2,300 |

| 10 to 14.9 km | 10,500 | -3,700 | -2,700 |

| 15 to 19.9 km | 56,300 | 4,800 | -600 |

| 20 to 24.9 km | 18,500 | 200 | -1,400 |

| 25 km or more | 78,300 | 1,800 | -1,600 |

| Vancouver | |||

| 0 to 4.9 km | -37,100 | 31,800 | 24,300 |

| 5 to 9.9 km | -2,400 | 20,600 | 2,800 |

| 10 to 14.9 km | 7,000 | 8,700 | 2,000 |

| 15 to 19.9 km | -4,700 | 6,600 | 500 |

| 20 to 24.9 km | 24,500 | 7,100 | 1,700 |

| 25 km or more | 50,000 | 6,200 | 2,800 |

| Calgary | |||

| 0 to 4.9 km | -4,900 | 16,800 | 7,600 |

| 5 to 9.9 km | 45,000 | 9,000 | 700 |

| 10 to 14.9 km | 44,900 | 4,200 | 2,400 |

| 15 to 19.9 km | 25,300 | 2,200 | 2,000 |

| 20 to 24.9 km | 5,500 | 300 | 400 |

| 25 km or more | 8,700 | 200 | 300 |

| Ottawa–Gatineau | |||

| 0 to 4.9 km | -10,100 | 11,200 | 4,200 |

| 5 to 9.9 km | 17,700 | 3,600 | -100 |

| 10 to 14.9 km | 11,300 | 1,300 | 200 |

| 15 to 19.9 km | 15,200 | 2,500 | 1,300 |

| 20 to 24.9 km | 13,000 | 1,100 | 600 |

| 25 km or more | 9,900 | 200 | -800 |

| Edmonton | |||

| 0 to 4.9 km | -2,800 | 12,100 | 900 |

| 5 to 9.9 km | 26,600 | 5,100 | -1,000 |

| 10 to 14.9 km | 57,600 | 5,500 | 2,300 |

| 15 to 19.9 km | 8,600 | 100 | 300 |

| 20 to 24.9 km | 4,300 | 100 | 400 |

| 25 km or more | 20,200 | 1,600 | -100 |

| Québec | |||

| 0 to 4.9 km | -7,000 | 4,400 | 1,400 |

| 5 to 9.9 km | 26,500 | 3,700 | -100 |

| 10 to 14.9 km | 10,400 | 800 | -500 |

| 15 to 19.9 km | 8,500 | 0 | 200 |

| 20 to 24.9 km | -200 | -200 | -500 |

| 25 km or more | -100 | 0 | -300 |

| Winnipeg | |||

| 0 to 4.9 km | -7,800 | -5,000 | -1,300 |

| 5 to 9.9 km | 16,900 | 2,200 | -1,200 |

| 10 to 14.9 km | 6,900 | 800 | -300 |

| 15 to 19.9 km | 2,500 | 0 | 0 |

| 20 to 24.9 km | 1,600 | 0 | -200 |

| 25 km or more | 1,100 | 0 | -100 |

|

Note: Includes all individiduals aged 15 and over working at a usual place of work within CMAs. Source: Statistics Canada, Census of Population, 1996 and 2016. |

|||

Toronto had the second-largest decline of car commuters among those who worked less than 5 km from the city centre (a decrease of 39,900 or 21%), followed by Vancouver (a decrease of 37,100 or 23%). On the other hand, public transit use among workers who worked within 5 km of the city centre increased in every CMA except Winnipeg, which had a decline of 5,000 (14%). The number of workers using other modes of transportation to get to work in the city core, including walking and cycling, also increased substantially during the period (by 52,300 in Toronto, for example).

In Toronto, 362,300 more workers commuted from home to locations 20 km or more from the city centre in 2016 compared with 1996 (representing a 90% increase). This shows that most of the job growth occurred outside of city core. In 2016, of the commuters who worked 20 or more km from Toronto’s city centre, 88% of them used the car to go to work. In comparison, 8% of these commuters took public transit to work. The number of commuters in Toronto who worked within the city core also increased, by 102,000 since 1996. Of the workers who worked within the city core in 2016, 58% took public transit to work in 2016, up from 52% in 1996. Conversely, the proportion of car commuters within the city core decreased from 38% in 1996 to 25% in 2016.

In Montréal, employment growth was also largest in the area outside the city core, with the largest growth seen in commuters who worked 15 km or more from the city centre. In 2016, 156,300 more commuters headed for job locations more than 15 km from the city centre compared with 20 years earlier. Of these commuters, there was an increase in the proportion who commuted by car, increasing from 86% in 1996 to 89% 2016. In Vancouver, employment growth was also largest in the area outside the city core. In Vancouver, the proportion of commuters who worked within 5 km of the city centre and took public transit increased by 9 percentage points since 1996.

Commuters living in Toronto were the most likely to live and work outside the city core

As mentioned above, from 1996 to 2016, job locations moved from the city core. Suburb-to-city core commuting was dominant during most of the 20th century because the city centre was the major source of suburban income.Note In the United States, by the 1990s, suburbs had become the main work destination for commuters. The economic diversity of suburbs in the United States has grown to nearly match that of central cities.Note

To describe this movement, each CMA has been divided into five commuting types: (1) within-city core commutes, defined as the residence and job location being within 5 km of the city centre,Note (2) traditional commutes, defined as the job location being within 5 km of the city centre and the residence being more than 5 km from the city centre, (3) reverse commutes, defined as the job location being further than 5 km from the city centre and the residence being within 5 km of the city centre, (4) short suburban commutes, defined as both the residence and job locations being further than 5 km from the city centre, but with a commuting distance of less than 5 km, and (5) long suburban commutes, defined as both the residence and job locations being further than 5 km from the city centre, but with a commuting distance of 5 km or more. For the sake of this discussion, categories 4 and 5 are referred to as “within-suburb” commuting and “between-suburb” commuting, respectively. These commuting types illustrate how commuters are getting to work, and allow for analysis of how commuting patterns across Canada are changing over time.

Many CMAs still have a significant number of commuters who live and work in the city core. However, commuting patterns have evolved since 1996. Commute types have shifted, accompanied by a decline in within-city core commuters and a rise in traditional, reverse, and within-suburban and between-suburban commute types.

In 2016, compared with the other seven largest CMAs, Toronto had the highest proportion of suburban commuters, with nearly 3 in 4 workers both living and working outside the city core. Furthermore, in Toronto, within-suburban commuters made up 20% of workers, and between-suburban commuters made up 55% of workers (Table 6). Winnipeg had the largest proportion of within-city core commuters, with 17% of commuters both living and working in the city core, followed by Vancouver (13%). In addition, Winnipeg also had the highest proportion of reverse commuters (12%), followed by Quebec (8%). Meanwhile, Toronto and Montréal had the lowest proportions of reverse commuters (3% and 4%, respectively).

Start of table 6

| Distribution of workers | ||

|---|---|---|

| 1996 | 2016 | |

| percent | ||

| Toronto | ||

| Within city-core commute | 9.7 | 6.9 |

| Traditional commute (outside-to-inside city core) | 13.0 | 16.3 |

| Reverse commute (inside-to-outside city core) | 2.0 | 2.8 |

| Within-suburban commute (suburban commute less than 5 km) | 20.8 | 19.5 |

| Between-suburban commute (suburban commute more than 5 km) | 54.5 | 54.6 |

| Montréal | ||

| Within city-core commute | 13.1 | 6.4 |

| Traditional commute (outside-to-inside city core) | 14.6 | 19.8 |

| Reverse commute (inside-to-outside city core) | 2.6 | 3.6 |

| Within-suburban commute (suburban commute less than 5 km) | 24.7 | 23.3 |

| Between-suburban commute (suburban commute more than 5 km) | 45.0 | 47.0 |

| Vancouver | ||

| Within city-core commute | 20.3 | 12.6 |

| Traditional commute (outside-to-inside city core) | 12.4 | 17.0 |

| Reverse commute (inside-to-outside city core) | 5.0 | 6.5 |

| Within-suburban commute (suburban commute less than 5 km) | 21.0 | 22.5 |

| Between-suburban commute (suburban commute more than 5 km) | 41.3 | 41.3 |

| Calgary | ||

| Within city-core commute | 22.4 | 8.9 |

| Traditional commute (outside-to-inside city core) | 27.0 | 29.5 |

| Reverse commute (inside-to-outside city core) | 8.1 | 5.3 |

| Within-suburban commute (suburban commute less than 5 km) | 16.6 | 17.9 |

| Between-suburban commute (suburban commute more than 5 km) | 25.9 | 38.5 |

| Ottawa–Gatineau | ||

| Within city-core commute | 21.9 | 10.8 |

| Traditional commute (outside-to-inside city core) | 29.9 | 34.7 |

| Reverse commute (inside-to-outside city core) | 3.6 | 4.5 |

| Within-suburban commute (suburban commute less than 5 km) | 15.6 | 16.2 |

| Between-suburban commute (suburban commute more than 5 km) | 29.0 | 33.9 |

| Edmonton | ||

| Within city-core commute | 18.5 | 8.5 |

| Traditional commute (outside-to-inside city core) | 19.7 | 21.7 |

| Reverse commute (inside-to-outside city core) | 6.3 | 6.7 |

| Within-suburban commute (suburban commute less than 5 km) | 19.7 | 20.5 |

| Between-suburban commute (suburban commute more than 5 km) | 35.9 | 42.7 |

| Québec | ||

| Within city-core commute | 21.2 | 12.0 |

| Traditional commute (outside-to-inside city core) | 21.8 | 25.3 |

| Reverse commute (inside-to-outside city core) | 2.2 | 8.0 |

| Within-suburban commute (suburban commute less than 5 km) | 20.2 | 18.7 |

| Between-suburban commute (suburban commute more than 5 km) | 34.7 | 36.1 |

| Winnipeg | ||

| Within city-core commute | 29.7 | 16.9 |

| Traditional commute (outside-to-inside city core) | 24.5 | 30.6 |

| Reverse commute (inside-to-outside city core) | 7.2 | 11.5 |

| Within-suburban commute (suburban commute less than 5 km) | 16.9 | 16.5 |

| Between-suburban commute (suburban commute more than 5 km) | 21.8 | 24.4 |

|

Note: Includes all individiduals aged 15 and over working at a usual place of work within CMAs. Source: Statistics Canada, Census of Population, 1996 and 2016. |

||

End of table

In 2016, Ottawa–Gatineau had the highest proportion of traditional commuters (35%)—those living outside the city core but working inside it—followed by Winnipeg (31%).

The proportion of within-city core commuters decreased in all eight CMAs

Commuting patterns in Canada have become more complex as population growth in municipalities and communities outside the city core has increased, coupled with workplaces becoming more spread-out over CMAs.Note

Since 1996, the proportion of commuters who worked and lived in the city core decreased across all eight CMAs, with the largest decrease in Calgary (a decline of 14 percentage points) and the smallest in Toronto (a decline of 3 percentage points). The proportion of between-suburban commuters has risen in seven of the eight CMAs during that time, with the exception of Vancouver where it has remained unchanged. The largest increase in the proportion of between-suburban commuters was in Calgary, increasing 13 percentage points over the 20-year period. The proportion of within-suburban commuters increased in four of the eight largest CMAs since 1996.

The proportion of traditional commuters increased in all eight CMAs over the 20-year period; Winnipeg saw the greatest increase (an increase of 6 percentage points). Since 1996, the proportion of people with a reverse commute has increased in all CMAs, with the exception of Calgary, where it has decreased by 3 percentage points. The greatest increase was seen in Québec, where the proportion rose from 2% in 1996 to 8% in 2016. These findings confirm the recent trends towards suburbanization of commutes, as proportionally more workers and workplaces are located outside the traditional city core.

The number of within-city core commuters declined in the three largest CMAs

Table 7 illustrates the changes in number of commuters by type of commute in Canada’s three largest CMAs: Toronto, Montréal and Vancouver. When the employment growth in commuting types from 1996 to 2016 is examined, there is large growth in traditional and reverse commuters in all three CMAs. Vancouver had the largest employment growth for traditional commuters, increasing 61% (representing 65,200 additional workers) since 1996. In all three CMAs, there was a decline in the number of within-city core commuters, with the largest decrease in Montréal, falling from 212,000 in 1996 to 111,500 in 2016 ( a decline of 47%).

Start of table 7

| Commuters | Change in number of commuters, 1996 to 2016 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1996 | 2016 | ||

| number | percent | ||

| Toronto | |||

| Within city-core commute | 209,900 | 176,000 | -16.2 |

| Traditional commute (outside-to-inside city core) | 282,000 | 417,900 | 48.2 |

| Reverse commute (inside-to-outside city core) | 43,900 | 71,300 | 62.4 |

| Within-suburban commute (suburban commute less than 5 km) | 450,900 | 500,300 | 11.0 |

| Between-suburban commute (suburban commute more than 5 km) | 1,179,200 | 1,401,200 | 18.8 |

| All commute types | 2,165,800 | 2,566,700 | 18.5 |

| Montréal | |||

| Within city-core commute | 212,000 | 111,500 | -47.4 |

| Traditional commute (outside-to-inside city core) | 236,100 | 347,800 | 47.3 |

| Reverse commute (inside-to-outside city core) | 42,000 | 62,500 | 48.8 |

| Within-suburban commute (suburban commute less than 5 km) | 397,700 | 409,000 | 2.8 |

| Between-suburban commute (suburban commute more than 5 km) | 725,700 | 826,400 | 13.9 |

| All commute types | 1,613,500 | 1,757,100 | 8.9 |

| Vancouver | |||

| Within city-core commute | 173,400 | 127,100 | -26.7 |

| Traditional commute (outside-to-inside city core) | 106,100 | 171,300 | 61.5 |

| Reverse commute (inside-to-outside city core) | 42,500 | 65,700 | 54.6 |

| Within-suburban commute (suburban commute less than 5 km) | 179,700 | 226,700 | 26.2 |

| Between-suburban commute (suburban commute more than 5 km) | 352,500 | 415,800 | 18.0 |

| All commute types | 854,200 | 1,006,600 | 17.8 |

|

Note: Includes all individiduals aged 15 and over working at a usual place of work within CMAs. Source: Statistics Canada, Census of Population, 1996 and 2016. |

|||

End of table

Of the three largest CMAs, Vancouver has the highest proportion of reverse commuters, with 7% of commuters travelling from the city core into a suburban area for work in 2016. This number was up slightly from 5% in 1996. In all three CMAs, there were large increases in employment growth for reverse commuters from 1996 to 2016. The largest increase was in Toronto (a 62% increase).

Public transit use higher among traditional commuters

In all eight CMAs, the share of commuters taking public transit was lower for within-suburban and between-suburban commuters, compared with traditional and reverse commuting types. These results are expected, given that routes into the city core are often the general focus of public transit infrastructure. The low proportion of public transit commuting in the suburban areas could be for a number of reasons. Either the infrastructure does not exist, or if the public transit option does exist, most of the time driving is preferred because of cost, time or simply convenience.

The three largest CMAs have higher proportions of public transit commuting across all commuting types (Table 8). Within-city core commuters working in Montréal have the highest public transit use (42%), followed by Toronto (38%). Traditional and reverse commuters working in Toronto have the highest public transit use (67% and 41%), followed by Montréal (55% and 35%) and Vancouver (45% and 31%).

Start of table 8

| Census metropolitan area | Type of commute | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Within city-core commute | Traditional commute (outside-to-inside city core) | Reverse commute (inside-to-outside city core) | Within-suburban commute (suburban commute less than 5 km) | Between-suburban commute (suburban commute more than 5 km) | All commute types | |

| percent | ||||||

| Public transit use in 2016 | ||||||

| Toronto | 37.8 | 66.6 | 41.4 | 16.7 | 12.5 | 24.7 |

| Montréal | 41.6 | 54.6 | 35.2 | 13.8 | 10.3 | 22.8 |

| Vancouver | 29.6 | 44.5 | 30.5 | 12.8 | 12.7 | 21.4 |

| Calgary | 19.0 | 27.8 | 16.6 | 10.1 | 7.4 | 15.4 |

| Ottawa–Gatineau | 25.1 | 31.3 | 23.9 | 10.1 | 7.7 | 18.9 |

| Edmonton | 24.8 | 23.0 | 14.1 | 9.2 | 4.9 | 12.0 |

| Québec | 20.3 | 16.0 | 19.7 | 8.2 | 4.9 | 11.4 |

| Winnipeg | 23.1 | 16.7 | 18.9 | 9.4 | 5.0 | 14.0 |

| Public transit use in 1996 | ||||||

| Toronto | 51.1 | 52.5 | 41.3 | 15.2 | 13.1 | 22.9 |

| Montréal | 42.0 | 37.7 | 28.9 | 16.1 | 12.4 | 21.3 |

| Vancouver | 29.3 | 29.5 | 14.6 | 8.5 | 8.8 | 15.8 |

| Calgary | 20.8 | 19.4 | 12.1 | 8.1 | 6.3 | 13.9 |

| Ottawa–Gatineau | 27.8 | 25.0 | 16.0 | 9.8 | 8.1 | 18.0 |

| Edmonton | 18.4 | 16.3 | 10.2 | 6.8 | 4.4 | 10.2 |

| Québec | 16.8 | 11.6 | 10.0 | 7.9 | 7.1 | 10.4 |

| Winnipeg | 24.1 | 15.7 | 16.1 | 9.2 | 7.2 | 15.3 |

| Use of active transportation in 2016 | ||||||

| Toronto | 47.4 | 2.9 | 4.8 | 13.6 | 0.4 | 6.7 |

| Montréal | 37.8 | 3.6 | 8.3 | 15.9 | 0.7 | 7.4 |

| Vancouver | 39.2 | 2.7 | 5.5 | 16.5 | 0.9 | 9.9 |

| Calgary | 38.2 | 2.1 | 4.7 | 12.8 | 0.6 | 6.8 |

| Ottawa–Gatineau | 42.3 | 3.2 | 5.3 | 16.1 | 0.9 | 8.9 |

| Edmonton | 26.7 | 1.5 | 3.0 | 10.7 | 0.5 | 5.2 |

| Québec | 33.9 | 1.6 | 4.5 | 14.1 | 0.9 | 7.8 |

| Winnipeg | 19.9 | 1.6 | 3.7 | 12.1 | 0.6 | 6.4 |

| Use of active transportation in 1996 | ||||||

| Toronto | 19.3 | 1.7 | 3.1 | 13.0 | 1.0 | 5.4 |

| Montréal | 16.0 | 2.2 | 4.7 | 17.4 | 1.5 | 7.5 |

| Vancouver | 16.6 | 2.3 | 2.5 | 16.3 | 1.9 | 8.0 |

| Calgary | 15.3 | 1.8 | 2.8 | 13.9 | 1.6 | 6.9 |

| Ottawa–Gatineau | 21.9 | 3.3 | 7.0 | 16.9 | 2.5 | 9.4 |

| Edmonton | 15.0 | 2.5 | 3.4 | 13.1 | 1.5 | 6.6 |

| Québec | 20.1 | 2.1 | 4.9 | 16.2 | 2.7 | 9.0 |

| Winnipeg | 13.2 | 1.9 | 3.8 | 16.0 | 1.9 | 7.8 |

|

Note: Includes all individiduals aged 15 and over working at a usual place of work within CMAs. Source: Statistics Canada, Census of Population, 1996 and 2016. |

||||||

End of table

The proportion of public transit commuters increased in all eight CMAs for both traditional and reverse commuters. Montréal had the largest increase in the proportion of traditional commuters taking public transit to work, increasing from 38% in 1996 to 55% in 2016. Vancouver and Toronto also had similar growth. At the same time, there was not much growth in other CMAs. Conversely, the largest increase in the proportion of public transit commuting among reverse commuters was in Vancouver (16 percentage points), followed by Québec (10 percentage points). Public transit use was not as high in suburban commutes and did not increase over the period in most CMAs, with the exception of Vancouver, where the proportion of both within-suburban and between-suburban commuters taking public transit increased since 1996.

The proportion of within-city core commuters using active transportation increased since 1996

Active transportation includes those walking or cycling to work. Not only does active transportation have obvious health benefits, but it also has environmental benefits, as it results in fewer vehicles on the road. Within-city core commuters had the highest proportion of workers using a form of active transportation to get to work, followed by within-suburban commuters. This is expected, given that these commuters are travelling relatively shorter distances to work compared with the other commuting types.

From 1996 to 2016, the proportion of within-city core commuters who walked or cycled to work increased in all eight CMAs. Within-city core commuters in Toronto have had the largest increase in active transportation (an increase of 28 percentage points) used for getting to work since 1996, followed by Vancouver and Calgary (both with an increase of 23 percentage points), Montréal (an increase of 22 percentage points), and Ottawa–Gatineau (an increase of 20 percentage points). Since 1996, Montréal has had the largest increase in reverse commuters using active transportation (by 4 percentage points), followed by Vancouver (by 3 percentage points).

In 2016, the two CMAs with the largest proportion of within-city core commuters using active transportation were Toronto (47%) and Ottawa–Gatineau (42%). In contrast, Winnipeg had the lowest proportion of within-city core commuters walking or cycling to work, with about 1 in 5 such commuters opting for this commuting type. Furthermore, the CMAs with the largest proportion of within-suburban commuters who used active transportation in 2016 were Vancouver (17%) and Ottawa–Gatineau (16%).

Conclusion

Using data from the Census of Population, this study examines changes in the commuting behaviour of Canadians working in the country’s largest CMAs over a 20-year period. The results of the analysis point to a constantly evolving pattern of the commuting flows of workers. In the past, more people took a traditional approach to commuting by travelling from the outer area of the CMA to within the city core. However, there is evidence of suburbanization of both place of residence and place of work, as seen by the general decrease in the proportion of commutes within-city cores and a corresponding increase in the proportion of commutes within and across communities outside the city core, and of traditional and reverse commutes.

This paper found that, although there is still a large proportion of jobs situated within the city core, there has been a decentralization of job locations since 1996. The three largest CMAs, Toronto, Montréal and Vancouver, had the highest shares of people working outside the city core. The decentralization of jobs is related to both population and employment growth. As employment within CMA grows, there is a need to expand job locations to outside the city core. This creates more place of residence and place of work locations further away from the city centre.

In 2016, most people still used the car to go to work. However, car use is generally on the decline—principally among those working in the city core—as more and more people are using alternative modes of transportation such as public transit, walking and cycling to get to work. Over the last 20 years, significant investments have been made in public transit infrastructure across CMAs. From 1996 to 2016, the proportion of traditional and reverse commuters who take public transit to work has increased. During the same period, among those who lived and worked in the city core, the proportion using active modes of transportation also rose. However, job growth is increasing outside the city core, with many commuters living and working in suburban areas, who are less likely to use public transit or to use active modes of transportation to go to work. These findings have implications for the design strategies of CMAs and their efforts to decrease the reliance of suburban commuters on cars to get to work.

Katherine Savage is an analyst with the Labour Statistics Division at Statistics Canada.

Start of text box

Data sources, methods and definitions

Data sources and methodology

For the purposes of analyzing commuting flows, descriptive statistics were produced using Census of Population data, linking respondents’ place of residence and place of work location for non-institutional residents aged 15 and over who reported a usual place of work within a selected CMA. This paper reports information about individuals working at a usual place in a CMA, but these may include individuals living in other CMAs or non-CMAs. For instance, many individuals working in Toronto actually live in Oshawa or Hamilton. For the purpose of this paper, the focus is on CMA workers—individuals working in the CMA even if they live in a different CMA. Individuals working outside selected CMAs were excluded from the analysis. Similarly, individuals working at home, outside Canada or working with no fixed workplace address were excluded from the analysis. The 1996 Census of Population data were produced using 2016 Census of Population geographic boundaries for historical comparability.

The analysis focuses on Canada’s eight largest CMAs by population according to the 2016 Census: Toronto, Montréal, Vancouver, Calgary, Ottawa–Gatineau, Edmonton, Québec and Winnipeg. Over one-half (54%) of the 13.9 million commuters with a usual place of work live in the top eight CMAs. These highly populated areas are of special interest from the commuting point of view because they include developed public transportation systems and a large concentration of businesses in the city core, and complex commuting flows potentially exaggerated by periodic traffic congestion.

Definitions

Census metropolitan area (CMA) is formed by one or more adjacent municipalities centred on a population centre (known as the core). A CMA must have a total population of at least 100,000 of which 50,000 or more must live in the core based on adjusted data from the previous Census of Population Program.

Census tracts (CTs) are small, relatively stable geographic areas that usually have a population of less than 10,000, based on data from the previous Census of Population Program. They are located in census metropolitan areas and in census agglomerations that had a core population of 50,000 or more in the previous census.

Distance from home to work refers to the straight-line distance, in kilometres, between a person's residence and their usual place of work.

Distance from job location to city centre refers to the straight-line distance, in kilometres, between a person's usual place of work and the census tract where the city hall of the CMA in which they work is located.

Distance from residence to city centre refers to the straight-line distance, in kilometres, between a person's residence and the census tract where the city hall of the CMA in which they work is located.

Main mode of commuting refers to the main mode of transportation a person uses to travel between their home and their place of work.

End of text box

- Date modified: