Economic and Social Reports

International students as a source of labour supply: Engagement in the labour market after graduation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.25318/36280001202101200002-eng

Skip to text

Text begins

Abstract

This study examines the extent to which international students are engaged in the labour market through the Post-Graduation Work Permit Program (PGWPP) after having held a study permit at the postsecondary level (yet before immigration). The number of international students participating in the PGWPP after their studies has increased markedly, driven by increasing numbers of international students in Canada and larger shares of international student graduates obtaining a post-graduation work permit (PGWP). The labour market participation of PGWP holders (defined as the share of PGWP holders with positive T4 earnings) remained fairly stable from 2008 to 2018, with roughly three-quarters reporting T4 earnings annually. With rising numbers of PGWP holders, this equated to the number of PGWP holders with T4 earnings growing more than 13 times in size, from 10,300 in 2008 to 135,100 in 2018. Median annual earnings received by PGWP holders with employment income also rose over this period, from $14,500 (in 2018 dollars) in 2008 to $26,800 in 2018, suggesting an increase in the average amount of labour input. Almost three-quarters of all PGWP holders became permanent residents within five years of having obtained their PGWP. Through participation in the PGWPP and subsequent transition to permanent residence, international students have provided a growing source of labour for the Canadian labour market that extends well beyond their periods of study.

Authors

Eden Crossman is with the Research and Evaluation Branch at Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada. Yuqian Lu and Feng Hou are with the Social Analysis and Modelling Division, Analytical Studies and Modelling Branch, at Statistics Canada.

Acknowledgements

This study was conducted in collaboration with Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada. The authors would like to thank Cédric de Chardon, Marc Frenette, Rebeka Lee, Katherine Wall and Linda Wang for their advice and comments on an earlier version of this paper.

Introduction

The number of international students has grown considerably worldwide, primarily from developing countries to Western developed countries. In recent years, Canada has led other major Western countries in the growth of international students. For instance, from 2008 to 2019, the number of permits issued to tertiary-level international students increased 2.8 times from 45,900 to 173,000 in Canada, compared with a growth of 7% from 340,700 to 364,000 in the United States, 50% from 249,000 to 374,000 in the United Kingdom, and 52% from 114,400 to 173,400 in Australia (OECD 2020). The faster growth in the inflows of international students in Canada is likely related to both the changing reception environment in other major receiving countries (particularly the United States, where the new admission of tertiary-level international students declined 23% from 2016 to 2019Note ) and concrete measures adopted by the Canadian government to attract international students.Note

The opportunity for international students to work in Canada after graduation and to potentially become permanent residents, and ultimately Canadian citizens, is considered a draw factor for prospective international students. When international students decide to stay and work in Canada after graduation, one of the main avenues to do so is through the Post-Graduation Work Permit Program (PGWPP). The PGWPP is a temporary worker program that provides labour market opportunities for international student graduates of public postsecondary and private degree-granting educational institutions. On the one hand, the PGWPP allows international students who have graduated from a recognized Canadian postsecondary institution to gain work experience in Canada and can provide the necessary job experience required to apply for some permanent residence streams. On the other hand, the PGWPP facilitates international students’ contribution to the Canadian labour market, increases the pool of qualified candidates for eventual immigration and serves to make Canada a more attractive destination of study (CIC 2010).

The PGWPP started in 2003 as a pilot program in selected provinces and expanded nationwide in 2005. Further enhancements in 2008 allowed recent graduates to obtain an open work permit for up to three years (depending on the length of their program of study) with no restrictions on location of work, employer, occupation or requirement of a job offer. With a post-graduation work permit (PGWP), as with all open work permits, graduates can work full time, work part time and be self-employed (CIC 2010). In 2014, international student program regulatory changes took effect and included amendments that extended to the period after graduation (Government of Canada 2014). Before 2014, study permit holders were not authorized to work after the completion of their studies while awaiting approval of their PGWP. With the changes, eligible international graduates are authorized to work full time after their studies are completed until a decision is made on their application for a PGWP.

Currently, to obtain a PGWP, the applicant must have graduated from an eligible designated learning institution. They must also have completed an academic, vocational or professional training program at an eligible institution in Canada that is at least eight months in duration leading to a degree, diploma or certificate. They had to have maintained full-time student status in Canada during each academic session of the program or programs of study they have completed. Students are ineligible for a PGWP if they have completed an English or French as a second language course or program of study, general interest or self-improvement courses, or a course or program of study at a private career college. Applicants can receive only one PGWP in their lifetime.

Little research has been done to examine how international students have taken advantage of the PGWPP by obtaining the PGWP, finding employment and transitioning to permanent residency. To fill this knowledge gap, this article assesses the extent to which international students are engaged in the labour market through the PGWPP after having held a study permit at the postsecondary level. This article is part of a series that provides a broad overview of international students as a source of labour in Canada. It seeks to better understand the activities of international students in the labour market after their period of study (yet before immigration).Note Specifically, this article examines the trends in the number and share of international students participating in the PGWPP and the share of PGWP holders with employment income and their earnings levels. The transitions of PGWP holders to permanent residency are also examined.

The analysis is based on international students who held a study permit at the postsecondary education level between 2004 and 2018 and on those who subsequently obtained a PGWP over the period from 2008 to 2018.Note For aspects of the analysis that look at study permits, information comes from the first study permit issued (and before the PGWP) and includes study permit holders who were aged 15 to 59 in the signing year.Note One PGWP is attributed to an individual, keeping the first one issued. This study relies on data from the Longitudinal Immigration Database that were integrated with T4 National Accounts Longitudinal Microdata File tax files.

The number of new post-graduation work permit holders has increased, with the largest gains occurring among those from India and those intending to work in Ontario

The number of international students participating in the PGWPP after their studies has increased markedly, alongside increasing numbers of international students in Canada. The number of first-time study permit holders has increased fairly steadily since the mid-2000s (when this number was roughly 75,000), accelerating notably after 2015 and reaching 250,000 in 2019 (Crossman, Choi and Hou 2021). At the same time, larger shares of international students are obtaining a PGWP after graduation. Chart 1 shows the cumulative rate of international students who obtained a PGWP by years after their first study permit expired. More recent cohorts of international students (defined by their first study permit expiration year) tended to have higher shares of students obtaining a PGWP. One year after their study permits had expired, 16% of international students with a study permit that expired in 2008 had obtained a PGWP; this compares with 43% of those with a study permit that expired in 2017. Five years after their first study permits had expired, 29% of the 2008 international student cohort had obtained a PGWP, compared with 48% of the 2012 cohort.

Data table for Chart 1

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| percent | |||||

| 2008 Cohort | 16 | 20 | 24 | 27 | 29 |

| 2009 Cohort | 18 | 23 | 28 | 32 | 34 |

| 2010 Cohort | 20 | 26 | 31 | 35 | 36 |

| 2011 Cohort | 25 | 32 | 36 | 39 | 41 |

| 2012 Cohort | 33 | 39 | 42 | 46 | 48 |

| 2013 Cohort | 37 | 42 | 47 | 50 | 52 |

| 2014 Cohort | 37 | 45 | 49 | 52 | Note ...: not applicable |

| 2015 Cohort | 36 | 43 | 48 | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable |

| 2016 Cohort | 34 | 42 | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable |

| 2017 Cohort | 43 | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable |

|

... not applicable Source: Statistics Canada, 2019 Longitudinal Immigration Database. |

|||||

From 2008 to 2018, the annual number of new PGWP holders grew more than six times in size, from 10,300 to 64,700 (Table 1). While this increase occurred for both men and women, the share of male PGWP holders was consistently larger than that of female PGWP holders throughout the period. By age, the share of PGWPs obtained by those aged 24 and younger has trended upwards over time, and made up almost half (49%) of all PGWPs signed in 2018. In contrast, the share signed by those aged 25 to 34 trended downwards, falling from 56% in 2008 to 46% in 2018, although their number rose continuously from 5,800 to 29,400.

The large majority of PGWP holders came from two source countries, India and China. Together, these two source countries comprised 66% of all PGWPs issued in 2018, up from 51% in 2008. The share of PGWPs obtained by international students from India grew more than four times in size from 10% in 2008 to 46% in 2018. The trend was reversed for the share obtained by international students from China, falling from 41% to 20%. Over this period, international students from India intending to study at the postsecondary level increased much faster than those from China (Crossman, Choi and Hou 2021).

The large majority of PGWP holders intended to work in Ontario, followed by those intending to work in British Columbia and Quebec. For PGWPs obtained in 2018, 56% were for those intending to work in Ontario (up from 44% in 2008); these shares were 16% for British Columbia and 11% for Quebec (down from 19% and 13%, respectively, in 2008).

| Post-graduation work permit signing year | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | |

| percent | |||||||||||

| Sex | |||||||||||

| Male | 54 | 55 | 56 | 57 | 59 | 57 | 58 | 57 | 55 | 55 | 56 |

| Female | 46 | 45 | 44 | 43 | 41 | 43 | 42 | 43 | 45 | 45 | 44 |

| Age group at PGWP signing year | |||||||||||

| Younger than 25 | 41 | 42 | 45 | 46 | 47 | 45 | 44 | 43 | 42 | 46 | 49 |

| 25 to 34 | 56 | 55 | 52 | 51 | 50 | 52 | 53 | 54 | 54 | 49 | 46 |

| 35 and older | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 |

| Top source country (2018 PGWP ranking) | |||||||||||

| India | 10 | 10 | 16 | 25 | 32 | 32 | 32 | 28 | 23 | 32 | 46 |

| China | 41 | 36 | 33 | 29 | 27 | 30 | 30 | 33 | 33 | 27 | 20 |

| France | 3 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 3 |

| South Korea | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Brazil | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Nigeria | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 |

| Iran | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Vietnam | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| United States | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| Pakistan | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Other countries | 31 | 33 | 32 | 28 | 24 | 22 | 21 | 22 | 24 | 23 | 19 |

| Intended destination | |||||||||||

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | 0 |

| Prince Edward Island | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | 0 |

| Nova Scotia | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | Note ...: not applicable | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| New Brunswick | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Quebec | 13 | 17 | 17 | 16 | 14 | 14 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 11 |

| Ontario | 44 | 42 | 45 | 46 | 48 | 48 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 56 |

| Manitoba | 5 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| Saskatchewan | 2 | 2 | 3 | 6 | 6 | 3 | Note ...: not applicable | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Alberta | 10 | 9 | 8 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 |

| British Columbia | 19 | 19 | 17 | 16 | 15 | 16 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 16 |

| Territories | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | 0 | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | 0 |

| Not stated | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | 0 | 95 | 90 | 94 | 94 | 1 |

| number | |||||||||||

| Total | 10,300 | 11,800 | 13,500 | 18,100 | 23,000 | 29,500 | 32,100 | 27,200 | 33,300 | 44,800 | 64,700 |

|

... not applicable Note: PGWP stands for post-graduation work permit. Sources: Statistics Canada, 2019 Longitudinal Immigration Database and T4 - National Accounts Longitudinal Microdata File. |

|||||||||||

The share of post-graduation work permit holders reporting earnings has remained fairly stable but differs by source country

The number of PGWP holders with positive T4 earnings rose more than 13 times in size from 10,300 in 2008 to 135,100 in 2018 (Table 2). This equated to roughly three-quarters of PGWP holders with T4 earnings in each year over the period.Note The share of PGWP holders reporting earnings provides a measure of their participation in the labour market. In this sense, their labour market participation rate has remained fairly stable over the period.

Although the proportions of male and female PGWP holders reporting employment earnings were roughly similar in the 2017 and 2018 tax years, the share for men was generally higher throughout the period (with the exception of 2008 and 2009). There was little difference by age in the share of PGWP holders reporting earnings.

Nigeria was the source country with the highest share of PGWP holders reporting earnings in 2018 (95%), followed by Brazil (91%), Vietnam (88%), and Iran and Pakistan (at 86% each). The major source country associated with the lowest share reporting earnings in this same year was China (62%), followed by the United States (67%), India (75%) and France (76%).

By destination, the highest share of PGWP holders reporting earnings in 2018 was for those intending to work in the territories (95%), followed by Newfoundland and Labrador (87%) and New Brunswick (86%). The intended destinations with the lowest shares of PGWPs reporting earnings in 2018 were Ontario (72%), British Columbia (75%) and Nova Scotia (76%). Some of the lowest shares of PGWP holders reporting earnings therefore occurred for destinations with the largest shares of PGWP holders, namely Ontario, British Columbia and Quebec.

| Tax year | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | |

| percent | |||||||||||

| Sex | |||||||||||

| Male | 77 | 73 | 70 | 69 | 73 | 75 | 76 | 76 | 75 | 75 | 75 |

| Female | 79 | 73 | 68 | 66 | 68 | 69 | 71 | 71 | 71 | 73 | 73 |

| Age group in the tax year | |||||||||||

| Younger than 25 | 78 | 72 | 69 | 69 | 73 | 73 | 75 | 75 | 75 | 76 | 73 |

| 25 to 34 | 79 | 74 | 69 | 67 | 70 | 72 | 73 | 73 | 73 | 73 | 75 |

| 35 and older | 75 | 71 | 68 | 68 | 69 | 71 | 72 | 72 | 74 | 77 | 81 |

| Top source country (2018 PGWP ranking) | |||||||||||

| India | 86 | 84 | 83 | 84 | 87 | 87 | 87 | 87 | 86 | 84 | 75 |

| China | 73 | 67 | 61 | 57 | 58 | 60 | 61 | 61 | 61 | 60 | 62 |

| France | 82 | 72 | 72 | 71 | 70 | 67 | 69 | 71 | 72 | 74 | 76 |

| South Korea | 72 | 65 | 58 | 58 | 62 | 65 | 69 | 71 | 72 | 76 | 80 |

| Brazil | 74 | 73 | 69 | 73 | 65 | 68 | 76 | 78 | 84 | 89 | 91 |

| Nigeria | 94 | 88 | 81 | 81 | 80 | 83 | 86 | 90 | 92 | 94 | 95 |

| Iran | 80 | 80 | 79 | 80 | 80 | 82 | 78 | 78 | 80 | 83 | 86 |

| Vietnam | 87 | 80 | 68 | 67 | 68 | 73 | 79 | 81 | 84 | 83 | 88 |

| United States | 82 | 74 | 68 | 63 | 63 | 63 | 61 | 62 | 62 | 66 | 67 |

| Pakistan | 86 | 78 | 78 | 77 | 83 | 83 | 83 | 84 | 83 | 85 | 86 |

| Other countries | 81 | 76 | 73 | 70 | 71 | 71 | 74 | 75 | 75 | 78 | 82 |

| Intended destination of PGWP | |||||||||||

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 81 | 83 | 75 | 72 | 75 | 76 | 73 | 65 | 55 | 77 | 87 |

| Prince Edward Island | 88 | 88 | 81 | 70 | 78 | 67 | 63 | 64 | 48 | Note ...: not applicable | 82 |

| Nova Scotia | 79 | 73 | 69 | 67 | 63 | 64 | 62 | 57 | 49 | 73 | 76 |

| New Brunswick | 84 | 76 | 72 | 69 | 70 | 75 | 75 | 78 | 70 | 85 | 86 |

| Quebec | 74 | 70 | 68 | 67 | 69 | 67 | 67 | 62 | 59 | 67 | 78 |

| Ontario | 75 | 71 | 67 | 67 | 70 | 72 | 74 | 70 | 64 | 73 | 72 |

| Manitoba | 82 | 74 | 74 | 72 | 78 | 79 | 78 | 69 | 61 | 89 | 81 |

| Saskatchewan | 87 | 81 | 79 | 85 | 87 | 85 | 79 | 63 | 56 | 80 | 82 |

| Alberta | 90 | 86 | 80 | 78 | 82 | 84 | 82 | 75 | 71 | 82 | 80 |

| British Columbia | 80 | 73 | 67 | 61 | 63 | 66 | 66 | 62 | 58 | 68 | 75 |

| Territories | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | 91 | Note ...: not applicable | 91 | 87 | 71 | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | 95 |

| Not stated | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | 75 | 76 | 78 | 76 | 75 | 74 |

| Total | 78 | 73 | 69 | 68 | 71 | 72 | 74 | 74 | 74 | 74 | 74 |

| number | |||||||||||

| Total number of PGWP holders with T4 earnings | 10,300 | 20,300 | 28,900 | 40,300 | 50,500 | 64,900 | 77,800 | 83,500 | 92,900 | 104,700 | 135,100 |

|

... not applicable Note: PGWP stands for post-graduation work permit. Sources: Statistics Canada, 2019 Longitudinal Immigration Database and T4 - National Accounts Longitudinal Microdata File. |

|||||||||||

Median earnings of post-graduation work permit holders have risen over the past decade

While Table 2 quantifies the percentage of PGWP holders who have employment income in a given tax year, Table 3 shows the median annual earnings of those who have employment income. Changes in earnings levels over time can provide an indication of changes in intensity of labour market engagement by PGWP holders who have paid employment. Over the past decade, the median earnings received by PGWP holders with employment income rose from $14,500 (in 2018 dollars) in 2008 to $26,800 in 2018, indicative of increased labour market engagement (e.g., hours worked during the tax year).

Earnings of male PGWP holders were consistently higher than those of their female counterparts. While earnings of PGWP holders were generally highest at the older end of the age spectrum, earnings growth was stronger for the younger age groups from 2008 to 2018.

In 2018, PGWP holders from Iran had the highest median earnings, followed by those from Nigeria and Pakistan. In contrast, earnings were lowest for those from China, followed by those from the United States and Vietnam. Over the period, earnings increased most among those from the United States, France and South Korea.

In 2018, the highest median earnings were reported by PGWP holders working in the territories, followed by those employed in Alberta and Saskatchewan. The lowest earnings were reported by those employed in Quebec, Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island. From 2008 to 2018, growth in earnings was highest among PGWP holders employed in Newfoundland and Labrador, followed by Quebec and New Brunswick. Growth was lowest among those working in Alberta, Prince Edward Island and Manitoba.

In 2018, median earnings were highest for those PGWP holders employed in mining and oil and gas extraction, utilities, and public administration. In contrast, the lowest earnings amounts were reported by those employed in educational services; administrative and support, waste management and remediation services; accommodation and food services; and retail trade. These differences across sectors are consistent with the general pattern among all Canadian workers. Earnings growth over the 2008-to-2018 period was highest for those PGWP holders working in accommodation and food services, retail trade, real estate and rental and leasing, and educational services.

| Tax year | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2008 | 2010 | 2012 | 2014 | 2016 | 2018 | |

| 2018 constant dollars | ||||||

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 15,900 | 20,000 | 23,000 | 25,200 | 29,300 | 28,100 |

| Female | 13,500 | 17,100 | 19,400 | 20,300 | 23,700 | 25,300 |

| Age at tax year | ||||||

| Younger than 25 | 12,800 | 14,100 | 16,600 | 18,600 | 21,800 | 23,500 |

| 25 to 34 | 16,000 | 21,600 | 24,300 | 25,600 | 29,000 | 28,800 |

| 35 and older | 17,300 | 20,800 | 24,000 | 25,200 | 27,300 | 29,000 |

| Top source countries (2018 PGWP ranking) | ||||||

| India | 16,100 | 18,000 | 22,100 | 26,300 | 31,600 | 27,500 |

| China | 13,800 | 17,400 | 18,200 | 18,900 | 21,900 | 23,100 |

| France | 13,800 | 18,400 | 23,600 | 22,400 | 22,600 | 27,100 |

| South Korea | 13,500 | 18,700 | 21,400 | 20,600 | 24,500 | 25,700 |

| Brazil | 17,600 | 21,600 | 26,600 | 25,000 | 25,300 | 28,800 |

| Nigeria | 19,600 | 22,300 | 25,200 | 24,700 | 27,900 | 31,900 |

| Iran | 22,000 | 18,800 | 24,000 | 22,700 | 26,900 | 32,100 |

| Vietnam | 17,400 | 23,700 | 25,000 | 21,000 | 23,900 | 25,300 |

| United States | 11,500 | 17,400 | 18,500 | 19,800 | 21,800 | 24,200 |

| Pakistan | 17,300 | 28,100 | 28,900 | 27,800 | 32,400 | 31,300 |

| Other | 15,400 | 19,500 | 22,600 | 22,600 | 24,700 | 27,500 |

| Province of employment in the tax yearTable 3 Note 1 | ||||||

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 10,100 | 15,700 | 19,000 | 21,900 | 27,300 | 26,300 |

| Prince Edward Island | 15,300 | 25,600 | 17,200 | 19,900 | 21,400 | 24,000 |

| Nova Scotia | 12,400 | 17,100 | 17,400 | 19,800 | 26,600 | 23,400 |

| New Brunswick | 13,400 | 20,200 | 23,000 | 24,800 | 28,800 | 27,800 |

| Quebec | 10,600 | 13,500 | 17,400 | 16,500 | 19,400 | 23,200 |

| Ontario | 13,300 | 19,200 | 20,000 | 21,400 | 26,000 | 26,000 |

| Manitoba | 15,700 | 19,300 | 15,400 | 23,500 | 24,100 | 25,200 |

| Saskatchewan | 16,900 | 14,300 | 26,100 | 32,300 | 32,300 | 30,400 |

| Alberta | 24,000 | 27,300 | 30,600 | 30,100 | 33,900 | 32,000 |

| British Columbia | 14,700 | 18,200 | 20,600 | 21,700 | 27,800 | 28,400 |

| Industry of employment in the tax yearTable 3 Note 2 | ||||||

| Agriculture, forestry, fishing and hunting | 15,800 | 17,600 | 19,400 | 23,200 | 29,600 | 29,900 |

| Mining and oil and gas extraction | 45,900 | 52,400 | 52,800 | 49,300 | 41,400 | 47,600 |

| Utilities | 33,600 | 45,000 | 44,800 | 47,100 | 48,900 | 42,300 |

| Construction | 22,900 | 24,500 | 27,000 | 28,900 | 32,000 | 32,000 |

| Manufacturing | 22,000 | 29,900 | 30,600 | 31,200 | 36,200 | 33,600 |

| Wholesale trade | 15,900 | 22,000 | 25,800 | 27,300 | 31,000 | 30,500 |

| Retail trade | 9,100 | 13,700 | 16,900 | 19,200 | 21,700 | 22,800 |

| Transportation and warehousing | 17,300 | 21,800 | 26,300 | 31,000 | 32,700 | 31,700 |

| Information and cultural industries | 19,700 | 25,500 | 27,100 | 30,300 | 37,300 | 32,800 |

| Finance and insurance | 20,900 | 29,500 | 32,100 | 33,300 | 36,000 | 35,500 |

| Real estate and rental and leasing | 12,400 | 20,500 | 22,000 | 23,300 | 27,400 | 29,000 |

| Professional, scientific, and technical services | 22,200 | 28,100 | 32,600 | 32,400 | 34,900 | 33,900 |

| Management of companies and enterprises | 20,100 | 25,800 | 29,800 | 29,900 | 32,600 | 31,000 |

| Administrative and support, waste management and remediation services | 11,900 | 14,800 | 15,300 | 17,200 | 20,500 | 22,100 |

| Education services | 8,600 | 10,900 | 11,100 | 12,300 | 15,300 | 19,500 |

| Health care and social assistance | 17,500 | 25,400 | 26,100 | 27,500 | 31,000 | 30,300 |

| Arts, entertainment and recreation | 11,200 | 13,000 | 18,000 | 19,200 | 20,500 | 23,000 |

| Accommodation and food services | 8,800 | 11,000 | 15,900 | 17,000 | 20,100 | 22,200 |

| Other services (except public administration) | 14,300 | 17,300 | 19,000 | 20,900 | 24,300 | 25,900 |

| Public administration | 25,300 | 35,000 | 39,000 | 41,000 | 46,200 | 40,000 |

| Overall | 14,500 | 18,700 | 21,500 | 23,100 | 26,800 | 26,800 |

Sources: Statistics Canada, 2019 Longitudinal Immigration Database and T4 - National Accounts Longitudinal Microdata File. |

||||||

The number of post-graduation work permit holders transitioning to permanent residency is increasing, particularly among those with a study permit at the college or master’s degree level

A previous study shows that among international students who arrived in the 2000s, about 3 in 10 became landed immigrants within 10 years of their arrival (Choi, Crossman and Hou 2021). It is expected the PGWP holders would have high transition rates, because Canadian work experience would improve their chance to be selected as economic immigrants, and because they may have stronger motivation to seek permanent residency than those who did not apply for a PGWP.

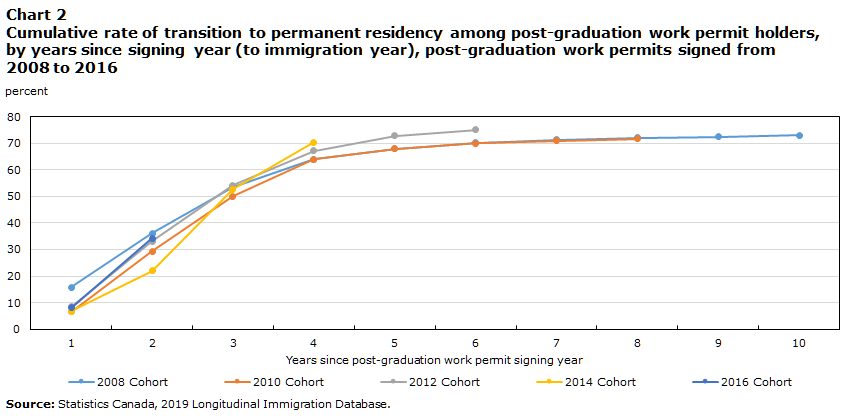

The overall cumulative share of transitions of PGWP holders to permanent residents by years since PGWP signing year (to immigration year) for PGWPs signed from 2008 to 2016 are shown in Chart 2. Overall, the rate of transition to permanent residency among PGWP holders remained consistently high across cohorts of PGWPs signed from 2008 to 2016. For cohorts from 2008 to 2012, almost three-quarters of PGWP holders became permanent residents within five years of having signed their PGWP, with little increase in this share in subsequent years. For the 2008 cohort, by the 10th year, 73% had become permanent residents.Note

Data table for Chart 2

| Years since post-graduation work permit signed | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |

| percent | ||||||||||

| 2008 Cohort | 16 | 36 | 53 | 64 | 68 | 70 | 71 | 72 | 72 | 73 |

| 2010 Cohort | 7 | 29 | 50 | 64 | 68 | 70 | 71 | 72 | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable |

| 2012 Cohort | 8 | 33 | 54 | 67 | 73 | 75 | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable |

| 2014 Cohort | 7 | 22 | 53 | 70 | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable |

| 2016 Cohort | 8 | 34 | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable |

|

... not applicable Source: Statistics Canada, 2019 Longitudinal Immigration Database. |

||||||||||

Differences in the transition to permanent residency among PGWP holders were evident by level of study. The cumulative transitions of PGWP holders to permanent residents by selected level of study and by years since PGWP signing year (to immigration year) for PGWPs signed from 2008 to 2016 are shown in Table 4. Generally speaking, when levels of study are compared, the rate of transition to permanent residency appears highest among those who held a study permit at the master’s degree level, followed by those at the college level. For both of these groups, there is also a trend towards increased transition rates across cohorts, with more recent cohorts having higher rates of transition at similar points in time, relative to earlier cohorts. While those who held a study permit at the bachelor’s degree level had the next highest rates of transition to permanent residency, these shares were more stable across cohorts. PGWP holders who held a study permit at the doctoral level had the lowest transition rates relative to other levels of study. However, some of the more recent cohorts had higher transition rates at similar points in time relative to earlier cohorts.

| PGWP signing year | Years since PGWP signing year | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |

| percent | ||||||||||

| Non-university postsecondary programs | ||||||||||

| 2008 | 12 | 31 | 49 | 62 | 67 | 70 | 72 | 72 | 73 | 74 |

| 2009 | 7 | 24 | 47 | 57 | 64 | 66 | 68 | 68 | 69 | Note ...: not applicable |

| 2010 | 4 | 30 | 50 | 66 | 70 | 72 | 74 | 74 | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable |

| 2011 | 4 | 34 | 62 | 72 | 77 | 79 | 80 | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable |

| 2012 | 5 | 32 | 57 | 72 | 78 | 81 | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable |

| 2013 | 5 | 21 | 44 | 67 | 76 | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable |

| 2014 | 3 | 16 | 52 | 74 | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable |

| 2015 | 4 | 29 | 61 | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable |

| 2016 | 7 | 33 | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable |

| University—bachelor's degree | ||||||||||

| 2008 | 15 | 36 | 53 | 63 | 67 | 69 | 70 | 71 | 71 | 72 |

| 2009 | 9 | 26 | 47 | 58 | 64 | 66 | 67 | 68 | 68 | Note ...: not applicable |

| 2010 | 6 | 26 | 46 | 60 | 65 | 67 | 68 | 69 | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable |

| 2011 | 7 | 26 | 48 | 59 | 64 | 66 | 67 | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable |

| 2012 | 8 | 27 | 44 | 58 | 64 | 66 | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable |

| 2013 | 5 | 20 | 38 | 55 | 62 | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable |

| 2014 | 6 | 17 | 45 | 60 | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable |

| 2015 | 5 | 25 | 49 | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable |

| 2016 | 6 | 29 | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable |

| University—master's degree | ||||||||||

| 2008 | 25 | 46 | 62 | 71 | 73 | 75 | 76 | 76 | 76 | 77 |

| 2009 | 17 | 34 | 55 | 64 | 69 | 70 | 71 | 72 | 72 | Note ...: not applicable |

| 2010 | 11 | 37 | 60 | 71 | 74 | 75 | 75 | 76 | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable |

| 2011 | 15 | 43 | 66 | 74 | 77 | 78 | 79 | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable |

| 2012 | 17 | 46 | 67 | 75 | 78 | 79 | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable |

| 2013 | 13 | 43 | 65 | 75 | 79 | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable |

| 2014 | 15 | 40 | 69 | 80 | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable |

| 2015 | 11 | 48 | 74 | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable |

| 2016 | 16 | 51 | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable |

| University—doctoral degree | ||||||||||

| 2008 | 21 | 32 | 42 | 49 | 52 | 55 | 56 | 57 | 58 | 58 |

| 2009 | 29 | 42 | 50 | 56 | 60 | 60 | 61 | 63 | 63 | Note ...: not applicable |

| 2010 | 16 | 34 | 51 | 59 | 63 | 64 | 66 | 67 | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable |

| 2011 | 20 | 37 | 47 | 56 | 59 | 60 | 61 | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable |

| 2012 | 22 | 44 | 57 | 67 | 68 | 70 | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable |

| 2013 | 20 | 44 | 57 | 67 | 70 | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable |

| 2014 | 21 | 41 | 55 | 64 | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable |

| 2015 | 15 | 38 | 63 | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable |

| 2016 | 12 | 42 | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable |

|

... not applicable Note: PGWP stands for post-graduation work permit. Sources: Statistics Canada, 2019 Longitudinal Immigration Database and T4 - National Accounts Longitudinal Microdata File. |

||||||||||

Conclusion

This study examined the extent to which international students are engaged in the labour market through the Post-Graduation Work Permit Program (PGWPP) after having held a study permit at the postsecondary level (yet before immigration). The number of international students participating in the PGWPP after their studies has increased markedly, driven by increasing numbers of international students in Canada and larger shares of international student graduates obtaining a post-graduation work permit (PGWP).

The labour market participation of PGWP holders (defined as the share of PGWP holders with positive T4 earnings) remained fairly stable from 2008 to 2018, with roughly three-quarters of PGWP holders reporting T4 earnings annually. With the rise in the number of PGWP holders, the number of PGWP holders with T4 earnings grew more than 13 times, from 10,300 in 2008 to 135,100 in 2018. Median annual earnings received by PGWP holders with employment income also rose over this period, from $14,500 (in 2018 dollars) in 2008 to $26,800 in 2018.

Almost three-quarters of all PGWP holders became permanent residents within five years of having obtained their PGWP. When levels of study are compared, the rates of transition to permanent residency were highest among those who held a study permit for college- and master’s-level programs. Both of these education groups showed a trend towards increased transition rates across cohorts, with more recent cohorts having higher rates of transition at similar points in time relative to earlier cohorts.

In sum, increasing numbers of international students have meant that increasing numbers of PGWP holders have engaged in the Canadian labour market over the past decade. Through participation in the PGWPP and subsequent transition to permanent residency for many, international students provided a growing source of labour for the Canadian labour market that extended well beyond their periods of study.

References

Choi, Y., E. Crossman, and F. Hou. 2021. “International students as a source of labour supply: Transition to permanent residence.” Economic and Social Reports 1 (6): 1–10. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 36-28-0001.

CIC (Citizenship and Immigration Canada). 2010. Evaluation of the International Student Program. Evaluation Division. Ottawa: CIC.

Crossman, E., Y. Choi, and F. Hou. 2021. “International students as a source of labour supply: The growing number of international students and their changing sociodemographic characteristics.” Economic and Social Reports 1 (7): 1–11. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 36-28-0001.

Government of Canada. 2014. “Immigration and Refugee Protection Act: Regulations Amending the Immigration and Refugee Protection Regulations.” Canada Gazette Part II, 148 (4). Available at: https://gazette.gc.ca/rp-pr/p2/2014/2014-02-12/html/sor-dors14-eng.html.

Israel, E., and J. Batalova. 2021. International Students in the United States. Migration Policy Institute. Available at: https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/international-students-united-states-2020.

OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development). 2020. International Migration Outlook 2020. Paris: OECD Publishing. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1787/ec98f531.

- Date modified: