Economic and Social Reports

Working from home in Canada: What have we learned so far?

Correction notice

The data points have been modified in the section titled Increases in the proportions of Canadians working from home could potentially reduce greenhouse gas emissions due to commuting

DOI: https://doi.org/10.25318/36280001202101000001-eng

Skip to text

Text begins

Since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, Statistics Canada has produced several studies on working from home. This article synthesizes the key findings of these studies, provides an international perspective and identifies questions for future research.

Roughly 40% of Canadian jobs can be done from home

In the context of a pandemic, telework feasibility (i.e., the degree to which Canadians hold jobs that can be done from home) is an important parameter. Deng, Messacar and Morissette (2020) apply the methodology of Dingel and Neiman (2020) to the 2019 Labour Force Survey data and estimate that 39% of Canadian workers hold jobs that can plausibly be carried out from home.

The feasibility of working from home varies substantially across wage deciles, education levels, industries and regions

The degree to which Canadians hold jobs that can be done from home varies substantially across several dimensions. Almost 6 in 10 workers with a bachelor’s degree or higher education (59%) can work from home, compared with 10% of their counterparts with no high school diploma (Deng, Messacar and Morissette 2020).Note Of the dual-earner salaried couples who are in the top decile of the family earnings distribution, 54% hold jobs in which both spouses can work from home. The corresponding percentage for dual-earner salaried couples in the bottom decile is 8% (Messacar, Morissette and Deng 2020).

The degree to which Canadians can work from home also varies substantially across industries. For example, about 85% of workers in finance and insurance, or in professional, scientific and technical services can potentially work from home (Deng, Messacar and Morissette 2020). In contrast, less than 1 in 10 workers in accommodation and food services (6%) can do so.

Since different regions have different industrial structures, these numbers explain partly why telework feasibility varies across regions. Because office jobs are generally concentrated in large cities, they tend to have greater proportions of jobs that can be done from home than smaller communities (Morissette, Deng and Messacar 2021).

The feasibility of working from home predicted well the degree to which Canadians worked from home during the pandemic

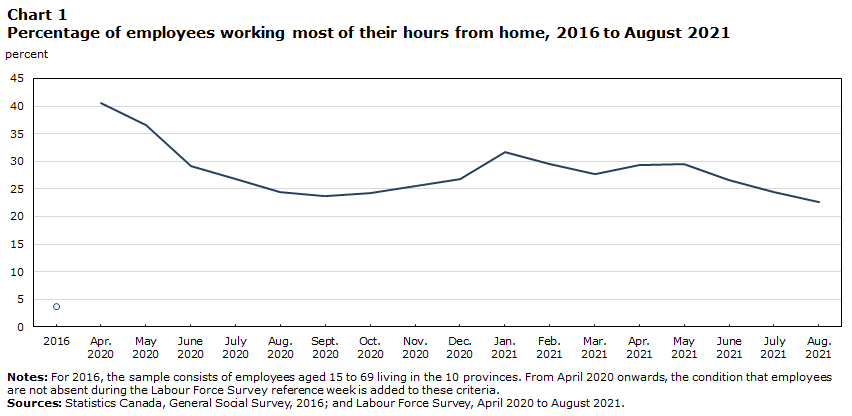

The indicator of the feasibility of working from home developed by Dingel and Neiman (2020) is a good predictor of the degree to which Canadians actually worked from home during the COVID-19 pandemic. It is in line with the maximum amount of work from home that has been observed since the beginning of the pandemic. In April 2020, about 40% of employees worked most of their hours from home, compared with 4% in 2016 and 23% in August 2021 (Chart 1). The indicator of feasibility also predicts well group-level differences in the amount of work from home. Specifically, groups of workers—defined by wage deciles, education, industry or region—who held jobs conducive to telework ended up working from home to a greater extent than other workers from April 2020 to June 2021. For example, roughly 70% of workers in finance and insurance or in professional, scientific and technical services worked most of their hours from home during that period (Statistics Canada 2021). In contrast, 5% of workers in accommodation and food services did so.Note

New teleworkers favourably assess productivity and report strong preferences for working from home

Mehdi and Morissette (2021a) analyzed new teleworkers (i.e., employees who usually worked outside the home prior to the COVID-19 pandemic but switched to telework during the pandemic) who had been with the same employer at least one year prior to the beginning of the economic shutdown announced in mid-March 2020. Most of these workers (90%) reported being at least as productive at home as they were previously on the business premises. Mehdi and Morissette also found that 80% of them would like to work at least half of their hours from home once the COVID-19 pandemic is over. Mehdi and Morissette (2021b) estimate that once the COVID-19 pandemic is over, the hours that Canadian employees would prefer working from home might amount, in the aggregate, to 24% of their total work hours. This estimate, which accounts only for worker preferences and does not incorporate employer preferences, equals almost five times the overall share of total hours worked from home observed in 2016 or 2018.

Increases in the proportions of Canadians working from home could potentially reduce greenhouse gas emissions due to commuting

By reducing the amount of commuting, working from home could potentially reduce the demand for public transit and greenhouse gas emissions. Morissette, Deng and Messacar (2021) estimate that a transition to full telework capacity—a situation in which all workers who can plausibly work from home would work all of their hours from home—could, through reduced commuting, lead to a reduction in annual emissions of greenhouse gases of about 9.5 megatonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent in Canada. This represents 6.7% of the direct greenhouse gas emissions from Canadian households in 2015, and 12.1% of their emissions attributable to transportation that year.

An increased feasibility of working from home may increase job security in future pandemics

In addition to its potential impact on productivity, public transit and greenhouse gas emissions, working from home might insulate workers from work interruptions during future pandemics, and, thus, might increase their job security during such periods. Frenette and Morissette (2021) define a new concept of job security that focuses on triple-protected jobs. These are jobs that (a) have no predetermined end date, (b) have a low risk of automation and (c) are resilient to pandemics. Jobs that are resilient to pandemics can be done from home, provide essential services or involve sufficient physical distancing. The likelihood of holding triple-protected jobs, like the feasibility of working from home, varies substantially across wage deciles, education levels and regions. For example, 9% of employees in the bottom decile of the wage distribution held triple-protected jobs in 2019, compared with 87% of employees in the top decile.

International comparisons

Much like in Canada, working from home is a relatively new experience for many employees around the world. While 39% of Canadian workers hold jobs that can plausibly be done from home, the corresponding estimates equal 37% for the United States and Germany, 38% for France, 35% for Italy, and 44% for the United Kingdom (Dingel and Neiman 2020). The percentages of workers who can work from home are substantially lower in countries such as Brazil (26%), Chile (26%) and Mexico (22%). The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) found that all of its member countries experienced increased rates of work from home during the pandemic (OECD 2021a). Working from home was most prevalent in knowledge-intensive sectors and least prevalent in manufacturing (OECD 2021b).

COVID-19 has accelerated the acceptance of working from home around the world. The sustainability of working from home hinges not on only employees’ productivity and preferences for working from home, but also on how employers feel about it. To assess this issue, Criscuolo et al. (2021) conducted an OECD survey of thousands of firms across 25 countries. They found that 90% of workers expressed a preference for doing more of their work from home in the future. Managers, meanwhile, expected around 60% of their workforce to do more of their work from home, with two to three days per week being the modal preference for working from home. Relatedly, as of August 2020, about 60% of Canadian employers expected a portion of their workforce to perform some work from home after the pandemic (OECD 2021a). Across the OECD, over 60% of managers saw increases in worker productivity as an advantage of working from home, while more than 75% expressed the main disadvantage of working from home as being the difficulty of teamwork.

Questions for future research

Several questions about working from home remain unanswered. One issue is the degree to which the preferences of Canadian workers for working from home and the preferences of their employers align. In addition, the extent of this alignment or misalignment may vary across industries and groups of workers. A second issue is the degree to which demand for public transit and office space will fall in Canada as a result of increased telework once the COVID-19 pandemic is over. The degree to which employers will use working from home as a tool to attract and retain talented workers also remains to be seen.

Data table for Chart 1

| Percentages from Labour Force Survey | Percentage from General Social Survey | |

|---|---|---|

| percent | ||

| 2016 | Note ...: not applicable | 3.6 |

| Apr. 2020 |

40.5 | Note ...: not applicable |

| May 2020 |

36.6 | Note ...: not applicable |

| June 2020 |

29.1 | Note ...: not applicable |

| July 2020 |

26.7 | Note ...: not applicable |

| Aug. 2020 |

24.5 | Note ...: not applicable |

| Sept. 2020 | 23.7 | Note ...: not applicable |

| Oct. 2020 |

24.3 | Note ...: not applicable |

| Nov. 2020 | 25.4 | Note ...: not applicable |

| Dec. 2020 |

26.7 | Note ...: not applicable |

| Jan. 2021 |

31.6 | Note ...: not applicable |

| Feb. 2021 |

29.6 | Note ...: not applicable |

| Mar. 2021 |

27.6 | Note ...: not applicable |

| Apr. 2021 |

29.4 | Note ...: not applicable |

| May 2021 |

29.4 | Note ...: not applicable |

| June 2021 |

26.5 | Note ...: not applicable |

| July 2021 |

24.4 | Note ...: not applicable |

| Aug. 2021 |

22.6 | Note ...: not applicable |

|

Notes: For 2016, the sample consists of employees aged 15 to 69 living in the 10 provinces. From April 2020 onwards, the condition that employees are not absent during the Labour Force Survey reference week is added to these criteria. Sources: Statistics Canada, General Social Survey, 2016; and Labour Force Survey, April 2020 to August 2021. |

||

Authors

Tahsin Mehdi and René Morissette are with the Social Analysis and Modelling Division at Statistics Canada.

References

Criscuolo, C., P. Gal, T. Leidecker, F. Losma, and G. Nicoletti. 2021. “Telework after COVID-19: Survey evidence from managers and workers on implications for productivity and well-being.” OECD Global Forum on Productivity.

Deng, Z., D. Messacar, and R. Morissette. 2020. Running the Economy Remotely: Potential for Working from Home During and After COVID-19. StatCan COVID-19: Data to Insights for a Better Canada, no. 26. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 45280001. Ottawa: Statistics Canada.

Dingel, J.I., and B. Neiman. 2020. How Many Jobs Can Be Done at Home? National Bureau of Economic Research working paper no. 26948. Cambridge: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Frenette, M., and R. Morissette. 2021. “Job security in the age of artificial intelligence and potential pandemics.” Economic and Social Reports 1 (6). Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 36-28-0001.

Mehdi, T., and R. Morissette. 2021a. Working from Home: Productivity and Preferences. StatCan COVID-19: Data to Insights for a Better Canada, no. 12. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 45280001. Ottawa: Statistics Canada.

Mehdi, T., and R. Morissette. 2021b. “Working from home after the COVID-19 pandemic: An estimate of worker preferences.” Economic and Social Reports 1 (5). Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 36-28-0001.

Messacar, D., R. Morissette, and Z. Deng. 2020. Inequality in the Feasibility of Working from Home During and After COVID-19. StatCan COVID19: Data to Insights for a Better Canada. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 45280001.

Morissette, R., Z. Deng, and D. Messacar. 2021. “Working from home: Potential implications for public transit and greenhouse gas emissions.” Economic and Social Reports 1 (4). Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 36-28-0001.

OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development). 2021a. Measuring Telework in the COVID-19 Pandemic. OECD Digital Economy Papers, no. 314. Paris: OECD Publishing.

OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development). 2021b. “Productivity gains from teleworking in the post COVID-19 era: How can public policies make it happen?” OECD Policy Responses to Coronavirus (COVID-19). Paris: OECD Publishing.

Statistics Canada. 2021. “Working from home during the COVID-19 pandemic: April 2020 to June 2021.” The Daily. August 4. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 11-001-X. Available at: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/210804/dq210804b-eng.htm.

- Date modified: