Economic and Social Reports

Use of child care for children younger than six during COVID-19

DOI: https://doi.org/10.25318/36280001202100800003-eng

Skip to text

Text begins

Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a significant impact on many aspects of the lives of Canadians, including the ability to secure and provide child care. This article examines the use of child care for children younger than 6, based on results from the 2020 Survey on Early Learning and Child Care Arrangements, collected between November 2020 and January 2021. Findings suggest that 52% of children younger than 6 were in regulated or unregulated child care, 8 percentage points lower than pre-pandemic levels. Although patterns in the types of care used, reasons parents selected that care and difficulties finding care were similar before and during the pandemic, some parents did cite pandemic-specific reasons for their use of care. For example, 14% of parents using care reported that at least one of the reasons they were using their current arrangement was because of limited availability during the pandemic. Furthermore, among parents not using child care, more than one-quarter (28%) felt that using child care was unsafe during the pandemic.

Authors

Leanne C. Findlay is with the Health Analysis Division, Analytical Studies and Modelling Branch at Statistics Canada. Lan Wei is with the Centre for Income and Socioeconomic Well-being Statistics at Statistics Canada

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a significant impact on many aspects of the lives of Canadians, including the ability to secure and provide child care. In the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, precautionary child care closures were widespread, with most provinces and territories mandating closure of licensed child care centres, although limited child care was available for essential workers. The status of regulatedNote and unregulated home child care varied across the Canadian provinces and territories. However, by late 2020, many child care facilities were operational, albeit with additional safety measures in place, including enhanced health and safety practices, and, in some cases, reduced capacity. From a labour market perspective, many Canadians, including parents, had returned to work, with rates being higher among those with teleworking capacity (Statistics Canada 2021), although balancing home and work responsibilities can be a challenge for parents (Findlay and Arim 2020).

Pre-pandemic results from the 2019 Survey on Early Learning and Child Care Arrangements revealed that 60% of children younger than 6 were in child care, which included centre-based care and regulated or unregulated home-based child care (Findlay 2019). However, information from early stages of the pandemic (May and June 2020) suggested that 72% of child care centres and 39% of regulated family child care homes closed at some point (Friendly et al. 2020), and that during this time only 10% of parents reported using child care services (Findlay and Arim 2020). Child care has increasingly been cited as being critical to economic recovery (Stanford 2020) and work–life balance, and in particular to stimulate women’s participation in the labour force, since mothers tend to shoulder the greatest weight in terms of child care (Moyser and Burlock 2018).

In terms of risks to children from participating in child care during a pandemic, international evidence does not suggest an association between child care participation and COVID-19 transmission (Gilliam et al. 2021). Furthermore, children appear to be less likely to be infected or to be transmitters of the virus (Ludvigsson 2020; Rajmil 2020). However, parents may be concerned for their children’s well-being and be less likely to send their children to a child care arrangement, or they may have different child care needs or preferences during the pandemic.

Just over half of children younger than 6 were participating in regulated or unregulated child care

According to the 2020 Survey on Early Learning and Child Care Arrangements, 52% of children younger than 6 participated in regulated or unregulated child care between November 2020 and January 2021 (Table 42-10-0004-01). As was the case in 2019, differences in participation rates were shown across the provinces and territories (see Chart 1). The highest participation rates were in Quebec; 75% of children younger than 6 were in child care in 2020, close to the 78% in 2019. By comparison, children living in Alberta were much less likely to participate in child care during the pandemic (41%), significantly lower than participation in 2019 (54%).

Data table for Chart 1

| 2020 | 2019 | |

|---|---|---|

| percentage of children in care | ||

| Canada | 52.2Note * | 59.9 |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 60.1 | 57.8 |

| Prince Edward Island | 60.7 | 65.6 |

| Nova Scotia | 54.9Note * | 61.0 |

| New Brunswick | 59.1 | 60.9 |

| Quebec | 75.2 | 78.2 |

| Ontario | 44.2Note * | 53.6 |

| Manitoba | 46.2 | 50.5 |

| Saskatchewan | 46.7 | 53.0 |

| Alberta | 41.4Note * | 54.1 |

| British Columbia | 49.9Note * | 57.6 |

| Yukon | 54.0 | 59.0 |

| Northwest Territories | 49.6 | 56.2 |

| Nunavut | 34.7 | 36.7 |

|

||

Participation in child care also differed based on the child’s age, although the trends by age group were similar to 2019. About 1 in 5 children younger than 1 were in some type of child care arrangement (20%), compared with 6 in 10 1- to 3-year-olds (60%). Among 4- and 5-year-olds, more than half (57%) of children were attending some form of child care regardless of school or kindergarten attendance—63% of children who were not in school and 54% of those who were in school.

Type of child care used was not different during the COVID-19 pandemic

During the pandemic, it is possible that parents used different types of child care arrangements compared with before the pandemic (Table 42-10-0005-01). However, the findings suggest that patterns of child care use were similar to 2019. Like before the pandemic, daycare centres, preschools or centres de la petite enfance (CPE) were the most commonly used types of arrangements among those using child care (49%), followed by care by a relative other than a parent (28%), and a family child care home (19%). Children were slightly more likely to be cared for by a relative in 2020 compared with 2019 (28% versus 26%), and slightly less likely to be in a before- or after-school programNote (7% versus 9%).

Child age plays a key role in the type of child care arrangement used. Of children younger than 1 participating in child care, 30% were in a daycare centre, preschool or CPE, and 50% were cared for by a relative. By comparison, of children aged 1 to 3 in child care, 52% were in a daycare centre, preschool or CPE, and 28% were cared for by a relative.

Among those aged 4 or 5 and participating in child care, 65% of those who were not in school or kindergarten were attending a daycare centre, preschool or CPE. Among those aged 4 or 5 participating in child care and in school or kindergarten, about one-third of those in child care were in a daycare centre, preschool or CPE and one-third were in a before- or after-school program.

Parent-reported reasons for choosing a specific type of care included availability during the COVID-19 pandemic

In 2020, parents’ and guardians’ reasons for choosing a particular child care arrangement were similar to reasons provided before the pandemic (Table 42-10-0006-01), with the most common being location (55% of parents with children in child care), characteristics of the person providing care (47%), affordable cost (40%), and hours of operation (36%). However, at the time of the survey, 14% of parents and guardians using care reported that limited availability during the pandemic was the reason for their current child care arrangement. The survey did not ask whether parents were required to change their arrangement during this time.

Parents reported difficulties finding child care arrangements

Approximately 4 in 10 parents who were using regulated or unregulated child care reported having difficulties finding child care (Table 42-10-0001-01). Of parents who self-reported using licensed care for their main child care arrangement, 38% reported having difficulties, and among those using unlicensed care (which includes relative care), 46% reported at least one difficulty. Among those using child care, parents of children aged 1 to 3 were the most likely to report difficulties (41%), followed by children younger than 1 year old (36%), children aged 4 or 5 not attending school (35%), and children aged 4 or 5 attending school (28%).

The majority of parents who were not using care had not looked for child care (63%). However, for those parents who were not using child care and who had looked, more than half had experienced difficulties. Although respondents were not specifically asked, it is possible that having difficulties finding care would result in not using care.

In terms of the types of difficulties that parents had, among parents who were using child care and who reported having difficulties, 56% reported that they had difficulty finding care in their community, and 43% had difficulty finding affordable care (Table 42-10-0008-01). Just over one in four said that they had difficulty finding care during the COVID-19 pandemic. For parents who were not using child care and who reported having difficulties, almost 6 in 10 (59%) said that the difficulty was finding affordable care, and 43% had difficulty finding care during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Having difficulties finding child care can affect parents’ ability to work

Having difficulties finding child care can result in one or more negative consequences for the parent, including having an impact on their ability to work (Table 42-10-0009-01). This may be particularly true during the pandemic, especially for mothers (Leclerc 2020). For those parents who were using child care and had difficulties, the most commonly reported consequences included changing their work schedule (36%), working fewer hours (31%), or having to use multiple arrangements or a temporary arrangement (29%). Among parents who had difficulties and were not currently using child care, 41% had postponed their return to work.

Not using child care is related to concerns for safety during the pandemic

There are many reasons that parents chose not to use child care arrangements during the pandemic, although these reasons were largely similar to the 2019 results (Table 42-10-0010-01). Both before and during the pandemic, the most common reasons for not using any child care (regulated or unregulated) were that the parent or guardian reported that they had decided to stay at home (37% of those not using child care in 2020; 43% in 2019), a parent was on maternity or parental leave (25% in 2020; 28% in 2019), or a parent was unemployed (14% in 2020; 16% in 2019). Almost one in four parents (23% in 2020; 25% in 2019) of children younger than 6 who were not using child care reported that the reason was that the cost was too high.

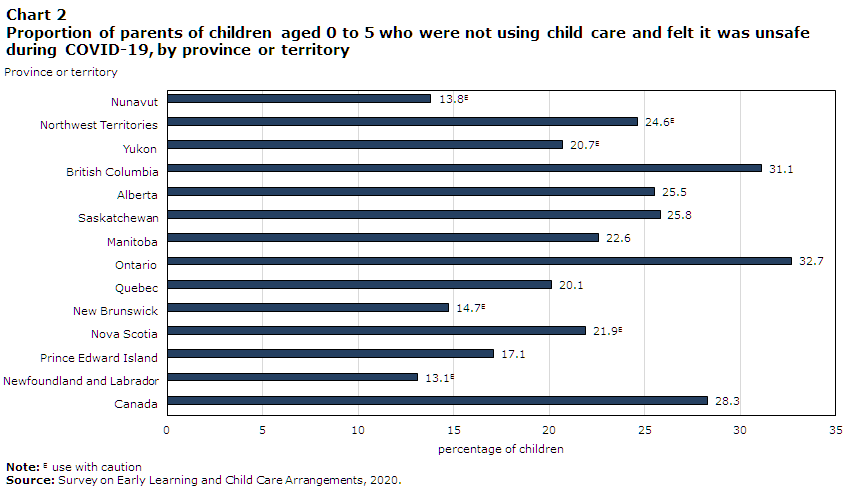

Parents reported specific reasons for not using child care during the pandemic. On the survey, 28% of parents who were not using any child care arrangement said that they did not feel it was safe during the pandemic, although differences were found by province and territory (see Chart 2). Approximately one in eight parents in Newfoundland and Labrador and in Nunavut who were not using child care said that they felt it was unsafe to use child care during the COVID-19 pandemic, compared with about one in three parents in Ontario and British Columbia. As well, 3 in 10 parents who were not currently using child care said that they had used child care previously (29%), although information about precisely when they had used child care and the type of child care used (i.e., before the pandemic) was not collected.

Data table for Chart 2

| Geography | Percentage of children |

|---|---|

| Canada | 28.3 |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 13.1Note E: Use with caution |

| Prince Edward Island | 17.1 |

| Nova Scotia | 21.9Note E: Use with caution |

| New Brunswick | 14.7Note E: Use with caution |

| Quebec | 20.1 |

| Ontario | 32.7 |

| Manitoba | 22.6 |

| Saskatchewan | 25.8 |

| Alberta | 25.5 |

| British Columbia | 31.1 |

| Yukon | 20.7Note E: Use with caution |

| Northwest Territories | 24.6Note E: Use with caution |

| Nunavut | 13.8Note E: Use with caution |

|

E use with caution Source: Survey on Early Learning and Child Care Arrangements, 2020. |

|

Data and methodology

The Survey on Early Learning and Child Care Arrangements (SELCCA) provides a snapshot of early child care use in Canada and was conducted in all provinces and territories from November 2020 to January 2021. The response rate was 57% in the provinces and 42% in the territories, yielding a sample size of 10,605 children, which represents about 2.3 million children in Canada. This response rate is similar to other Rapid Stats surveys and to the 2019 SELCCA.

The target population was children aged 0 to 5 years who were randomly selected from the Canada Child Benefit file (one child per household). The survey was completed by a parent, guardian or person who was knowledgeable about the child’s care arrangements (or lack thereof). The respondent was female in 91% of cases. Children living in institutions or on reserve were excluded from the target population surveyed.

In this survey, child care arrangements include any form of care for children younger than 6, regulated or unregulated, by someone other than the parent or guardian. Examples include the use of centre-based facilities and care in a home by a relative or non-relative, and before- and after-school programs. Occasional babysitting and kindergarten were not considered child care for purposes of this survey, although it is possible that some parents use kindergarten as a form of non-parental child care.

Survey sampling weights were applied to render the analyses representative of Canadian children younger than 6 living in the provinces or territories. Bootstrap weights were also applied when testing for significant differences (p < 0.05) to account for the complex survey design.

Conclusion

The SELCCA provides current information on child care participation during COVID-19 that can be compared with patterns of pre-pandemic participation. The findings suggest an 8% decrease in child care participation during the pandemic, with 52% of children younger than 6 participating in some type of regulated or unregulated arrangement during the pandemic, compared with 60% in 2019. However, the patterns of the types of arrangements used were largely unchanged. There are many complexities related to the use and type of care that children participate in during the pandemic when parents likely experience work disruptions such as dealing with pandemic-related closures and re-openings, working extended hours (e.g., front-line workers), working from home, or having different options available to them because of varying and changing regulations across the provinces and territories.

During the pandemic, one in four parents and guardians who were using child care and reported difficulty finding child care said that the difficulty was specifically related to the pandemic. Among those not using child care at all, just over one-quarter said that they felt it was unsafe during the COVID-19 pandemic. These results point to the impact that COVID-19 has had on parents in finding and using child care and may also speak to the additional burden placed on families’ ability to participate in the labour force, children’s opportunities to socialize, and children’s safety and well-being.

Child care and school closures are an unintended consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic. The economic trade-off of such closures is the increased difficulty for parents to work, in particular parents with young children and essential workers, including those in the health care field (Bayhem and Fenichel 2020). This may be particularly relevant for women, who are more likely to bear the weight of child care responsibilities (Sevilla and Smith 2020; Zamarro and Prados 2021). Patterns of future use, child care availability, and safety will be of utmost importance to post-pandemic recovery for families and their young children.

References

Bayhem, J., and E.P. Fenichel. 2020. “Impact of school closures for COVID-19 on the US health-care workforce and net mortality: A modeling study.” The Lancet: Public Health 5 (5): E271–E278.

Findlay, L.C. 2019. Early Learning and Child Care for Children Aged 0 to 5 Years: A Provincial/Territorial Portrait. Economic Insights. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 11-626-X.

Findlay, L.C., and R. Arim. 2020. Child Care Use During and After the Pandemic. StatCan COVID-19: Data to Insights for a Better Canada. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 45280001. Ottawa: Statistics Canada.

Friendly, M., B. Forer, R. Vickerson, and S. Mohamed. 2020. Canadian Child Care: Preliminary Results from a National Survey During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Toronto: Childcare Resource and Research Unit, Canadian Child Care Federation, Child Care Now.

Gilliam, W.S., A.A. Malik, M. Shafiq, M. Klotz, C. Reyes, J.E. Humphries, Murray, T., Elharake, J.A., Wilkinson, D. and S.B. Omer. 2021. “COVID-19 transmission in US child care programs.” Pediatrics 147 (1): e2020031971.

Leclerc, K. 2020. Caring for Their Children: Impacts of COVID-19 on Parents. StatCan COVID-19: Data to Insights for a Better Canada. Catalogue no. 45280001. Ottawa: Statistics Canada.

Ludvigsson, J.F. 2020. “Systematic review of COVID-19 in children shows milder cases and better prognosis than adults.” Acta Paediatrica 109 (6): 1088–1095.

Moyser, M., and A. Burlock. 2018. “Time use: Total work burden, unpaid work, and leisure.” In Women in Canada: A Gender-based Statistical Report. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 89-503-X. Ottawa: Statistics Canada.

Rajmil, L. 2020. “Role of children in the transmission of the COVID-19 pandemic: A rapid scoping review.” BMJ Paediatrics Open 4 (1).

Sevilla, A., and S. Smith. 2020. Baby Steps: The Gender Division of Childcare During the COVID-19 Pandemic. IZA Discussion Papers Series, no. 13302. Bonn: IZA Institute of Labor Economics, (accessed May 17, 2021).

Stanford, J. 2020. The Role of Early Learning and Child Care in Rebuilding Canada’s Economy After COVID-19. Vancouver: Centre for Future Work.

Statistics Canada. 2021. COVID-19 in Canada: A One-year Update on Social and Economic Impacts. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 11-631-X. Ottawa: Statistics Canada.

Zamarro, G., and M.J. Prados. 2021. “Gender differences in couples’ division of childcare, work and mental health during COVID-19.” Review of Economics of the Household 19: 11–40.

- Date modified: