Analytical Studies Branch Research Paper Series

Examining the Labour-productivity Gap Between Women-owned and Men-owned Enterprises: The Influence of Prior Industry Experience

Skip to text

Text begins

Acknowledgements

This study is funded by Women and Gender Equality Canada. The authors would like to thank Horatio Morgan, Charles Bérubé, Ibrahim Bousmah, Jamie Dzikowski and reviewers from Women and Gender Equality Canada.

Abstract

An increase in the economic participation of women has been identified as a major driver of economic growth, leading to increased interest in supporting the entrepreneurial activities of women. This paper uses newly developed data on the gender of business owners to investigate differences in labour productivity between men-owned, women-owned and equally owned enterprises. A regression model with propensity score weighting was implemented to provide an estimate of the impact of the owner’s prior industry experience on labour productivity. By using propensity score weighting to adjust for various factors, including the prior income of the owner, this paper is able to provide insight into the causal relationship between the gender of ownership and many relevant factors, given the effect of prior experience on labour productivity by groups of enterprises. The results of this analysis can then be used to calculate labour-productivity gaps between the groups.

This paper presents a number of results concerning the gender of ownership of an enterprise. First, there are some significant differences between the principal owners of men-owned, women-owned and equally owned enterprises, with principal owners of men-owned enterprises being the most likely to have prior industry experience. For this paper, enterprise owners have prior industry experience if they owned an incorporated enterprise in the same industry as the new enterprise in the five years prior to entry. The principal owner of an enterprise is defined as the owner with the highest level of shares. Second, even when industry and other enterprise characteristics are controlled for, women-owned and equally owned enterprises have significantly lower labour productivity than men-owned enterprises, and the difference is larger for women-owned enterprises than it is for equally owned enterprises. Third, prior industry experience of the enterprise owner increases relative labour productivity, and this effect is much larger in women-owned enterprises. As a result, the labour-productivity gap between women- and men-owned enterprises is significantly smaller among enterprises where the owners have prior industry experience. Fourth, controlling for prior experience and owner characteristics results in a lower overall estimated productivity gap between women- and men-owned enterprises. Finally, productivity gains from prior experience may occur through accumulated knowledge and skills related to the management of employees.

Executive summary

An increase in the economic participation of women has been identified as a major driver of economic growth, leading to increased interest in supporting the entrepreneurial activities of women. This paper uses newly developed data on the gender of business owners to investigate differences in labour productivity between men-owned, women-owned and equally owned enterprises. First, a model was implemented to provide an estimate of the impact of the owner’s prior industry experience on labour productivity. By controlling for various factors, including the characteristics of the owner, this paper is able to provide an estimate of the impact of relevant prior experience on labour productivity by groups of enterprises. The results of this analysis can then be used to calculate labour-productivity gaps between the groups.

This paper presents a number of results concerning the gender of ownership of an enterprise. First, there are some significant differences between the owners of men-owned, women-owned and equally owned enterprises, with owners of men-owned enterprises being the most likely to have prior industry experience. Second, even when industry and other enterprise characteristics are controlled for, women-owned and equally owned enterprises have significantly lower labour productivity than men-owned enterprises, and the difference is larger for women-owned enterprises than it is for equally owned enterprises. Third, prior industry experience of the enterprise owner increases relative labour productivity, and this effect is much larger in women-owned enterprises. As a result, the labour-productivity gap between women- and men-owned enterprises is significantly smaller among enterprises where the owners have prior industry experience. Fourth, controlling for prior industry experience and owner characteristics results in a lower overall estimated productivity gap between women- and men-owned enterprises. Finally, productivity gains from prior experience may occur through accumulated knowledge and skills related to the management of employees.

These results are relevant for policy making in that they provide causal insights into the factors influencing the relative labour productivity of women-owned firms. First, they highlight the relevance of owner characteristics and prior owner experience in explaining the labour productivity of enterprises. Second, they show how these variables are important for understanding gaps in the labour productivity of groups of enterprises, specifically men-owned, women-owned and equally owned enterprises. Finally, and as a consequence of the first two points, the findings support the fact that policies aiming at reducing labour-productivity gaps among groups of enterprises could target the experience of business owners, especially their experience in the industry of the enterprise they own.

1 Introduction

An increase in the economic participation of women has been identified as a major driver of economic growth, leading to increased interest in supporting the entrepreneurial activities of women (Couture and Houle 2020). In the Canadian context, women-owned enterprises have been found to lag behind men-owned enterprises in terms of survival, productivity and other indicators of business performance, even when controlling for firm characteristics, e.g., assets and number of employees, and for industry (Couture and Houle 2020; Grekou 2020). This paper provides new evidence on the labour-productivity gap by examining the prior industry experience of enterprise owners. Specifically, it focuses on providing evidence regarding three main questions. First, what is the relationship between prior industry experience and labour productivity by gender? Second, can the prior industry experience of owners be used to explain a portion of the labour-productivity gap? This question is motivated by existing research that finds that owners of women-owned enterprises are less likely to have relevant prior industry experience than owners of men-owned enterprises (Grekou 2020). Third, is there evidence that returns to prior industry experience occur through accumulated knowledge and skills related to the management of employees? This last question is motivated by research by Flabbi et al. (2019), who find evidence that female executives increase firm performance because they are more effective at assigning female employees tasks that match their skills.

To address these questions, this paper uses the Canadian Employer–Employee Dynamics Database (CEEDD), described in detail in the next section. The CEEDD is a linkable data environment containing administrative data on the complete set of Canadian enterprises. It also contains information on all Canadian employees issued a T4 Statement of Remuneration. By linking enterprise owners to employment records, the CEEDD can be used to examine the impact of prior industry experience on enterprise-level productivity by gender. For this paper, enterprise owners have prior industry experience if they owned an enterprise in the same industry as the new enterprise in the five years prior to entry. For the analysis, data from 2006 through 2017 were restricted to new incorporated enterprises with at least one employee, in order to create a set of comparable enterprises. Using this restricted set, propensity score weighting is employed to obtain an estimate of the impact of prior industry experience on labour productivity by adjusting for owner characteristics and controlling for enterprise characteristics.

Despite the advantages provided by the CEEDD, the main empirical challenge arises from the possibility that prior industry experience is correlated with factors that have a causal impact on labour productivity. For example, if individuals with prior industry experience have higher personal wealth, and higher personal wealth causes higher labour productivity, then the coefficient estimate for prior industry experience will capture the impact of personal wealth. In this case, the coefficient cannot be interpreted as the direct effect of prior industry experience. In this example, interpretation would be especially difficult if prior industry experience and prior wealth vary by gender of owner, since the empirical exercise is to estimate the impact of prior industry experience by gender of owner. To overcome this empirical challenge, this study uses logistic regression and owner characteristics to estimate three propensity scores for each enterprise, where the three scores reflect the probabilities of being in each of three groups: women-owned enterprises, men-owned enterprises and equally owned enterprises. These propensity scores can then be transformed into generalized propensity scores, which are then used as weights in regression analysis. The mechanism by which this empirical method improves estimation is explained in more detail in Section 3. This model is used to estimate labour-productivity gaps, and an extension of the model is implemented to determine whether the results are consistent with those of Flabbi et al. (2019).

Before employing this empirical strategy, a baseline is obtained by estimating a model with controls for industry, region and enterprise characteristics. Relative to men-owned enterprises, women-owned enterprises were estimated to be 18.0% less productive, and equally owned enterprises were estimated to be 9.1% less productive. After prior industry experience was added and owner characteristics corrected for using generalized propensity scores, the estimate of the labour-productivity gaps fell to 16.5% for women-owned enterprises and 5.9% for equally owned enterprises, respectively. Prior industry experience had a statistically significant impact on labour productivity for all three groups of enterprises, but the gain was significantly larger for majority women-owned enterprises. Among enterprises where the principal owner did not have prior industry experience, women-owned enterprises were 20.9% less productive than men-owned enterprises, but among enterprises where the owners had prior industry experience, women-owned enterprises were 0.2% less productive, and the gap was not statistically significant. Owners of equally owned enterprises did not experience significantly different gains to experience from owners of men-owned enterprises. After the labour-productivity gaps were estimated, the model was extended to add an interaction term between prior industry experience and the number of employees for owners of women-owned enterprises. For owners of women-owned enterprises, productivity gains from prior experience were greater when the number of employees was larger. This may be because owners with prior experience have accumulated knowledge and skills related to the management of employees and the effect of this knowledge is larger for women, who have previously been shown to be effective in realizing labour-related efficiency gains (Flabbi et al. 2019).

These results add to a large literature—mostly based on survey data—on the performance of women-owned enterprises. Comparing women-owned enterprises with men-owned enterprises, several papers find that women-owned enterprises underperform in at least one measure (Brush 1992; Fisher 1992; Rosa, Carter and Hamilton 1996; Du Rietz and Henrekson 2000; Fairlie and Robb 2009). However, Du Rietz and Henrekson (2000) find that in an extensive multivariate regression with a large number of controls, women-owned enterprises have lower sales but not profitability; the authors suggest that women entrepreneurs have a weaker preference for sales growth than men entrepreneurs. Consistent with this result, subsequent papers argue that differences in enterprise size and risk aversion explain much of the “underperformance” in business measures (Robb and Watson 2012; Marlow and McAdam 2013). Women also face barriers to entrepreneurship that could impede performance. Bates (2002) finds that women-owned enterprises in the manufacturing sector have less access to business clients than men-owned enterprises, and Brush et al. (2018) find that female entrepreneurs are significantly less likely to receive external financing from venture capital. Rosa and Sylla (2016) find that Canadian women-owned small and medium enterprises (SMEs) seeking loans face higher interest rates than men-owned SMEs and are less likely to receive the amount of financing requested. These barriers may limit women to small, slow-growth enterprises. Studies using administrative data in the Canadian context have found that gaps persist in revenue and employment (Grekou 2020) and labour productivity and survival (Houle and Couture 2020), even when controlling for enterprise characteristics. This paper adds to the literature by providing causal insights into the relationship between labour productivity and prior industry experience of the enterprise owner by gender. Specifically, it provides evidence that there are significant labour productivity gains from prior industry experience for principal owners of women-owned enterprises. Combined with the fact that owners of women-owned enterprises are less likely to have prior industry experience, this finding helps to explain a proportion of the labour-productivity gap.

The remainder of this paper proceeds as follows. Section 2 describes the data and their limitations and provides some descriptive statistics on enterprises by gender of owner. Section 3 outlines the empirical framework used to estimate the impact of prior experience on the labour-productivity gap. Section 4 presents the results. Section 5 provides a conclusion.

2 Data and descriptive statistics

2.1 Data

A detailed description of the data is given by Grekou (2020). The present paper uses Statistics Canada’s CEEDD, which provides information on business owners, such as gender, age, marital status, immigrant status, earnings from paid jobs, self-employment income, earnings from owned corporations, number of children by age group, and ownership shares. This information is augmented with information about their workplace, such as the sector of activity, labour productivity (to be defined below), total assets, number of employees, and spending in research and development. The ownership information determines whether a Canadian-controlled private corporation (CCPC) is a men-owned enterprise, women-owned enterprise or an equally owned enterprise (Grekou 2020). Essentially, if the shares owned by women or men are greater than or equal to 51%, the enterprise is considered as women-owned or men-owned; if women and men own 50% of the shares, the enterprise is considered equally owned.

This paper uses the CEEDD to gather information on businesses in the 2001-to-2017 time period, with information on their principal owner defined as the owner with the highest level of shares and of the same ownership type as the firm owned.Note

The analysis file is restricted to CCPCs operating in any industry except public administration (North American Industry Classification System [NAICS], 91) and that were not owned by a public entity according to the Business Register. The enterprises were also restricted to those with at least one employee for at least six months.

The analysis focuses on cohorts of new enterprises from 2006 to 2017. In this paper, an enterprise is considered a new enterprise if, in any given year, it (1) had a new business number and (2) had at least one employee for 6 months.

2.2 Limitations

The universe of business owners in this paper follows Grekou and Liu (2018), who restrict business owners to individuals listed in Schedule 50 of a T2 tax return whose employment status generating the highest income (i.e., their primary activity) is business ownership.Note Business owners are therefore defined as CCPC owners with at least a 10% share, whose business ownership activity is their primary activity.

Important clarifications are necessary. First, this paper considers primary employment status only. The possible employment statuses in the CEEDD are business ownership, self-employment (i.e., unincorporated business owners), paid employment (identified with a T4 form), and non-employment (if not identified in any of the other three categories). Hence, in this paper, individuals who own an incorporated business but derive most of their income from self-employment or paid employment are not considered business owners. This intends to restrict the focus to true business owners, since the CEEDD is a large administrative database, not a dedicated database on business owners.Note However, this restriction makes entry into business ownership more restrictive. Second, in the CEEDD, individuals can become business owners by starting a new enterprise or by buying shares in an existing enterprise.

The variables used in the paper are described in detail in Table A1 in the appendix.

2.3 Trends in labour productivity

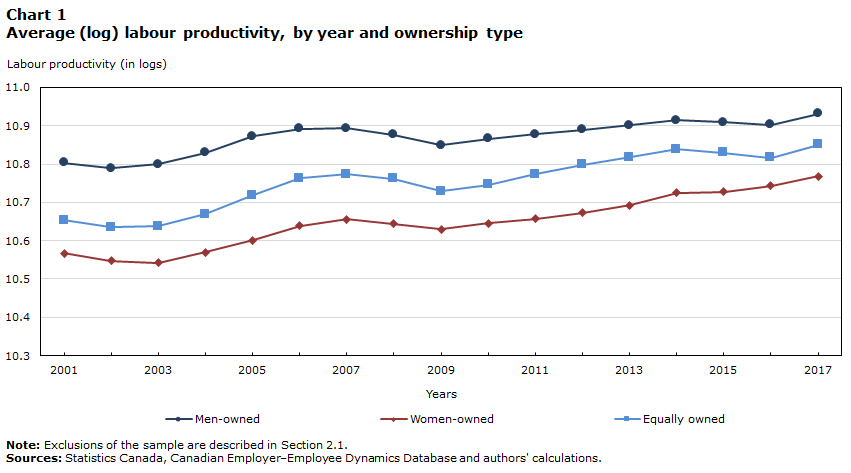

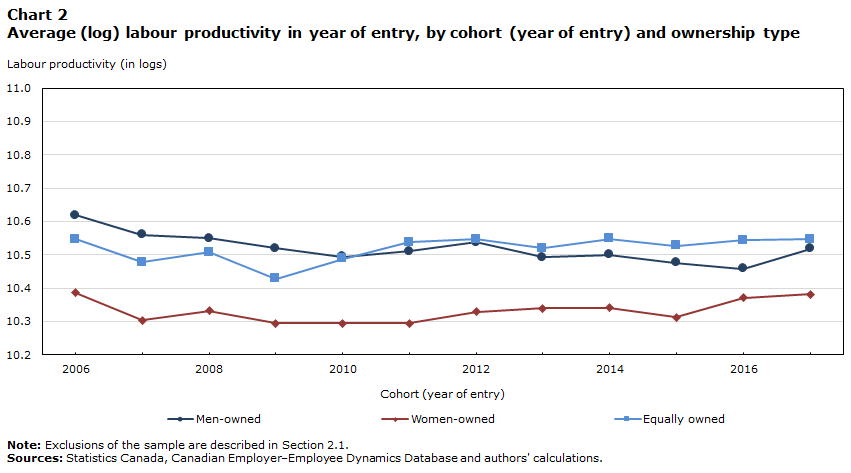

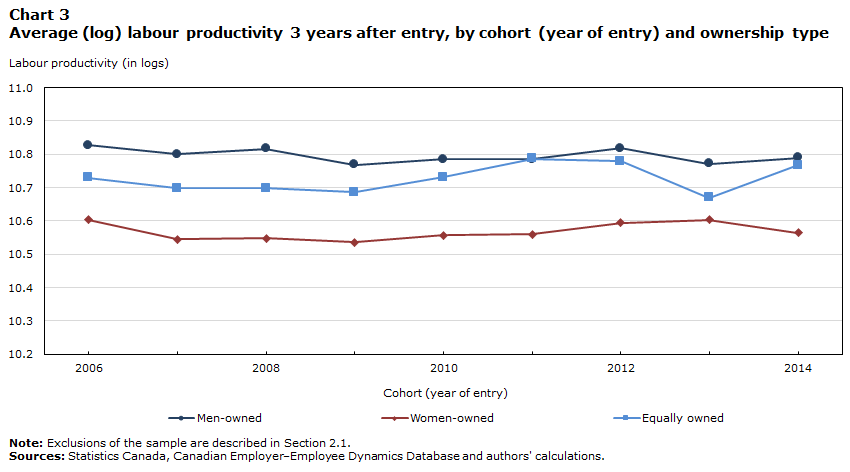

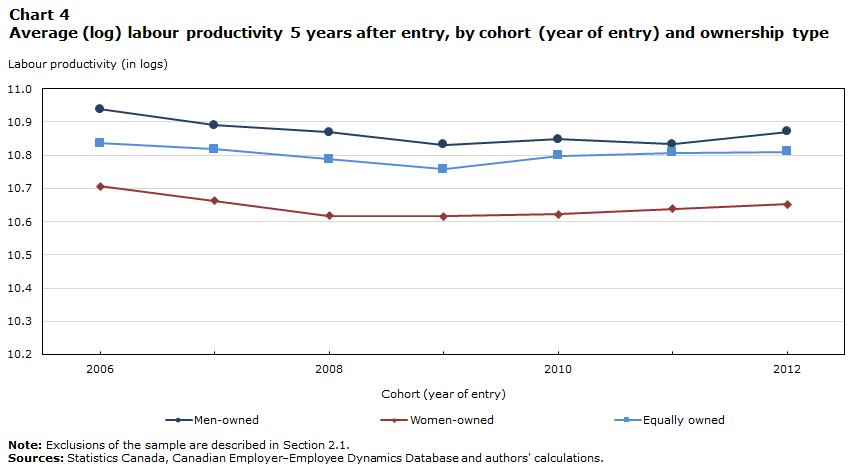

This subsection presents labour productivity by ownership type. Labour productivity is measured at the firm level. It is defined as value-added output divided by the total number of employees where value-added output is computed as the sum of profit (net income before tax), labour costs (T4 payroll) and capital cost allowance (as a measure of depreciation of capital).Note The CEEDD allows an analysis of labour productivity in at least two manners: analysis of the average labour productivity of all enterprises in a given year (Chart 1) or, alternatively, the analysis of the average labour productivity by cohort of entry (Charts 2 to 4).

The analysis shows that men-owned enterprises tended to have higher levels of labour productivity. This is verified from 2001 to 2017 (Chart 1), as well as by cohort of entry three or five years after entry (Charts 3 and 4, respectively). Importantly, women-owned enterprises tended to have labour productivity that fell below that of men-owned and equally owned enterprises. This is consistent with the literature that describes that women-owned enterprises in Canada tended to have lower levels of labour productivity (Couture and Houle 2020) as well as other performance indicators (e.g., Rosa and Sylla 2016; Grekou 2020). Significantly, the differences in labour productivity between men-owned enterprises and women-owned enterprises and between men-owned enterprises and equally owned enterprises closed slightly, as illustrated by the narrowing gaps (Chart 1).

Data table for Chart 1

| Years | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Labour productivity (in logs) | |||||||||||||||||

| Men-owned | 10.8028 | 10.7892 | 10.7999 | 10.8297 | 10.8727 | 10.8918 | 10.8931 | 10.8760 | 10.8494 | 10.8665 | 10.8777 | 10.8895 | 10.9013 | 10.9145 | 10.9084 | 10.9022 | 10.9311 |

| Women-owned | 10.5671 | 10.5470 | 10.5420 | 10.5697 | 10.6016 | 10.6389 | 10.6559 | 10.6446 | 10.6302 | 10.6452 | 10.6575 | 10.6730 | 10.6930 | 10.7254 | 10.7277 | 10.7428 | 10.7687 |

| Equally owned | 10.6532 | 10.6352 | 10.6382 | 10.6693 | 10.7188 | 10.7633 | 10.7736 | 10.7618 | 10.7296 | 10.7460 | 10.7730 | 10.7978 | 10.8173 | 10.8385 | 10.8292 | 10.8170 | 10.8509 |

|

Note: Exclusions of the sample are described in Section 2.1. Sources: Statistics Canada, Canadian Employer–Employee Dynamics Database and authors' calculations. |

|||||||||||||||||

For cohorts that started their business after 2010, equally owned enterprises had, on average, higher levels of labour productivity than men-owned enterprises and women-owned enterprises (Chart 2). However, it is interesting to note that men-owned enterprises were nevertheless able to generate the highest level of labour productivity three or five years after entry (Charts 3 and 4).

Data table for Chart 2

| Cohort (year of entry) | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Labour productivity (in logs) | ||||||||||||

| Men-owned | 10.6188 | 10.5605 | 10.5502 | 10.5201 | 10.4939 | 10.5101 | 10.5379 | 10.4927 | 10.5007 | 10.4759 | 10.4583 | 10.5176 |

| Women-owned | 10.3864 | 10.3040 | 10.3329 | 10.2953 | 10.2951 | 10.2950 | 10.3291 | 10.3395 | 10.3409 | 10.3123 | 10.3706 | 10.3819 |

| Equally owned | 10.5467 | 10.4784 | 10.5084 | 10.4286 | 10.4878 | 10.5381 | 10.5467 | 10.5204 | 10.5481 | 10.5277 | 10.5439 | 10.5467 |

|

Note: Exclusions of the sample are described in Section 2.1. Sources: Statistics Canada, Canadian Employer–Employee Dynamics Database and authors' calculations. |

||||||||||||

Data table for Chart 3

| Cohort (year of entry) | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Labour productivity (in logs) | |||||||||

| Men-owned | 10.8273 | 10.8002 | 10.8163 | 10.7685 | 10.7855 | 10.7857 | 10.8182 | 10.7720 | 10.7890 |

| Women-owned | 10.6038 | 10.5455 | 10.5478 | 10.5355 | 10.5575 | 10.5605 | 10.5953 | 10.6043 | 10.5653 |

| Equally owned | 10.7301 | 10.6975 | 10.6982 | 10.6859 | 10.7313 | 10.7872 | 10.7796 | 10.6692 | 10.7678 |

|

Note: Exclusions of the sample are described in Section 2.1. Sources: Statistics Canada, Canadian Employer–Employee Dynamics Database and authors' calculations. |

|||||||||

Data table for Chart 4

| Cohort (year of entry) | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Labour productivity (in logs) | |||||||

| Men-owned | 10.9371 | 10.8901 | 10.8680 | 10.8305 | 10.8471 | 10.8324 | 10.8694 |

| Women-owned | 10.7055 | 10.6625 | 10.6180 | 10.6160 | 10.6217 | 10.6389 | 10.6525 |

| Equally owned | 10.8357 | 10.8179 | 10.7875 | 10.7580 | 10.7985 | 10.8070 | 10.8107 |

|

Note: Exclusions of the sample are described in Section 2.1. Sources: Statistics Canada, Canadian Employer–Employee Dynamics Database and authors' calculations. |

|||||||

2.4 Enterprise characteristics

The next sections will explain the gaps in productivity among men-owned, women-owned and equally owned enterprises. Specifically, they will estimate the impact of prior experience of the principal owner. Besides the principal owner’s individual characteristics, characteristics of the firm, such as total assets, number of employees and expenses in research and development, will be controlled for. Table 1 presents the average levels of these three variables in the year of entry over the 2006-to-2017 period.

At entry throughout the 2006-to-2017 time period, men-owned enterprises had, on average, higher levels of assets and research and development, and comparable number of employees to women-owned enterprises. They were followed by equally owned enterprises. These differences may be partially explained by differences in industry composition, as women are more likely to own firms in service-based industries as opposed to goods-based industries (Couture and Houle 2020).

| Total assets | Number of employees | Research and development | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Men-owned | 411,674 | 3.27 | 62,645 |

| Women-owned | 282,471 | 3.03 | 28,913 |

| Equally owned | 226,452 | 2.47 | 17,714 |

| Sources: Statistics Canada, Canadian Employer–Employee Dynamics Database and authors' calculations. | |||

3 Empirical framework

The first goal of the empirical framework is to provide causal insight regarding the impact of prior industry experience of the principal owner on the labour productivity of an enterprise. The second goal is to determine the impact of prior industry experience on the estimated labour-productivity gap between men-owned enterprises, women-owned enterprises and equally owned enterprises. The challenge in estimating the impact of prior industry experience is that it may be correlated with several variables (such as income) that are also correlated with measures of enterprise success (such as labour productivity). To estimate the impact of prior industry experience, it is desirable to estimate an effect akin to the average treatment effect on the treated:

This can be estimated by groups—in this case, women-owned enterprises, men-owned enterprises and equally owned enterprises. Here, is an indicator that is equal to 1 when the owner of enterprise has prior industry experience, is the observed outcome for an enterprise where the owner that has prior industry experience, and is the counterfactual outcome. In other words, it is the outcome that would be observed if the owner did not have prior industry experience, but was otherwise the same. It is not possible to observe or know the counterfactual outcome. Instead, causal methods work by constructing an appropriate counterfactual from control units (in this case, enterprise owners’ prior industry experience). In this case, the unadjusted data likely does not provide the appropriate counterfactual because owners with prior experience are meaningfully different from owners without prior experience. Similarly, any estimate of the labour-productivity gap is contaminated by the fact that owners of women-owned enterprises are meaningfully different from owners of other enterprises.

Propensity score estimation adjusts data to allow the creation of meaningful comparison groups (Smith and Todd 2005). In some cases, propensity scores are used to match units between groups and units that do not match are discarded, with the result that the adjusted groups are more similar than the unadjusted groups. This method reduces the size of the sample, but it may be necessary when the groups of interest are extremely different. In this case, there appears to be sufficient overlap between the characteristics of owners within each group (men-owned, women-owned and equally owned enterprises), so propensity score estimation is used to reweight records, rather than discard records. This allows for the preservation of the dataset and sample size.

3.1 Model to estimate generalized propensity scores

The goal of propensity score estimation is to create comparable groups by balancing characteristics between groups (Smith and Todd 2005). In this particular case, the propensity score model is used to estimate generalized propensity scores, which can then be used as weights in a labour-productivity model. Observations should be weighted so that the weighted means of characteristics between groups are more similar than the unweighted means of characteristics between groups. In practice, only characteristics observed in data can be used to perform balancing, but in theory, balancing can reduce unobserved differences between groups when the observed characteristics are correlated with unobserved characteristics. For example, if prior income is associated with ability to obtain external financing, balancing on prior income reduces the bias incurred from differences in the ability to obtain external financing, even if external financing is not observed.

Since, in this case, there are three relevant groups and the order of the groups is not important, the model used to estimate the scores is a generalized (or unordered) multinomial logistic regression model, also referred to as a generalized multinomial logit model (Allison 2018). With majority men-owned enterprises as the reference group, the model simultaneously estimates the following equations:

Where and are vectors of owner characteristics and and are the corresponding coefficients, is the natural logarithm function and is a probability function. These models are estimated simultaneously via maximum likelihood estimation and the outcomes of the model are log-odds, which give the relative odds of an enterprise being in a certain group compared with the reference group. The results of this model can be used to estimate the probability that a record is in each group, and these probabilities sum to 1 for each enterprise.

Taking these probabilities, the generalized propensity score for an enterprise in group is

In other words, the lowest probability for enterprise is divided by the probability of the enterprise being in their observed group. For example, suppose that the model predicts that given its owner information, an enterprise has a 60% chance of being a men-owned enterprise, a 30% chance of being an equally owned enterprise, and a 10% chance of being a women-owned enterprise. If the enterprise is a men-owned enterprise, the weight is about 0.166 (10/60), if it is an equally owned enterprise the weight is about 0.333 (10/30), and if it is a women-owned enterprise, the weight is 1 (10/10). Note that the enterprise is assigned the highest weight when they are observed in the most unlikely group. The logic here is that enterprises that have characteristics that are not typical of their group (but rather are typical of another group) should be given more weight if the goal is to balance characteristics between groups. In this example, the fact that the enterprise has a high chance of being a men-owned enterprise indicates that the enterprise has owner characteristics typical of a men-owned enterprise. If the enterprise turns out to be a women-owned enterprise, then giving it a relatively high weight brings the average characteristics for women-owned enterprises closer to the average characteristics for men-owned enterprises.

3.2 Model to estimate the impact of prior experience on labour productivity

The labour-productivity model can be used to estimate the impact of prior industry experience on labour productivity, and the coefficients of the model can be transformed to estimate labour-productivity gaps between groups of enterprises. The baseline and full model are the following:

Both models are estimated using pooled data from 2006 through 2017. The dependent variable is the natural logarithm of labour productivity three years after the entry of the enterprise (results for the year of entry and for five years after entry are presented in the appendix). “WOE” is a dummy indicating whether the enterprise is majority women-owned, “EOE” is a dummy indicating whether the enterprise is equally owned,enterprise controls is a vector of enterprise characteristics, and industryis a vector of industry dummies, where industry is based on the two-digit NAICS code (Statistics Canada 2020). Prior industry experience is a dummy indicating whether the owner owned an incorporated business in the same NAICS category as the new enterprise in the five years prior to entry. Both models are estimated with and without weights, where the weights are the generalized propensity scores from the propensity score model. For the baseline model, the reference group is majority men-owned enterprises. For the full model, the reference group is men-owned enterprises where the owner does not have prior industry experience.

Since the dependent variable is the natural logarithm of an outcome, and the independent variables are binary, the resulting coefficients are in log-odds. To obtain labour-productivity gaps in percentages, the coefficients must be transformed. Table 2 shows the relationships between the coefficients of the full model and various labour-productivity gaps.

| Desired labour-productivity gap, relative to equivalent men-owned enterprises | Estimated gap, as a percentage, relative to equivalent men-owned enterprises |

|---|---|

| Women-owned enterprises | |

| No prior industry experience | 100*(exp(β1) – 1) |

| Prior industry experience | 100*(exp(β1 + β5) – 1) |

| Equally owned enterprises | |

| No prior industry experience | 100*(exp(β2) – 1) |

| Prior industry experience | 100*(exp(β2 + β6) – 1) |

|

Notes: Exp() is the exponential function. Recall that prior experience must occur as the owner of an incorporated enterprise. Source: Statistics Canada, authors' tabulations. |

|

Lastly, we estimate an extension of the full model with an additional interaction term that allows us to test whether productivity gains come from accumulated skills and knowledge related to the management of labour, consistent with Flabbi et al. (2019). The model is as follows:

If the estimate of is positive, then principal owners of women-owned enterprises realize greater returns to experience when the number of employees is higher. This would be consistent with results observed by Flabbi et al. (2019), namely that female executives are able to realize productivity gains through efficient division of labour.

4 Results

This section begins by presenting the results of the generalized propensity score model. The primary purpose of the generalized propensity score model is to generate weights that can be used in the labour-productivity model. However, the results in themselves are meaningful because they relate owner characteristics to the probability of being a principal owner of a men-owned, women-owned or equally owned enterprise. The section continues by presenting the results of the labour-productivity model and by using the coefficients from the model to derive estimates of labour-productivity gaps between groups. The section concludes by presenting an extension of the model which allows gains to experience to vary by the number of employees in the new enterprise.

4.1 Results of the generalized propensity score model

The general (or unordered) multinomial logistic regression relates owner characteristics to the probability of being the principal owner of a men-owned, women-owned or equally owned enterprise (Table 3). The reference group is men-owned enterprises, and the coefficients must be interpreted relative to this reference group. An enterprise has reduced odds of being women-owned (versus men-owned) if the owner is a recent immigrant, has a spouse, or is in a rural area. An enterprise has greatly increased odds of being women-owned if there are children in the owner’s family.

In terms of financial variables, an enterprise has reduced odds of being woman-owned if the owner has higher family income or higher savings. The savings variable is limited because it only captures registered savings reported on tax. Detailed variable descriptions are in the appendix.

| Variable and response | Estimate | Standard error | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | |||

| Majority women-owned enterprise | -1.046Note ** | 0.0373 | <0.001 |

| Equally-owned enterprise | -2.848Note ** | 0.0504 | <0.001 |

| Age | |||

| Majority women-owned enterprise | 0.002Note * | 0.0008 | 0.0135 |

| Equally-owned enterprise | 0.003Note ** | 0.0009 | <0.001 |

| Recent immigrant | |||

| Majority women-owned enterprise | -0.314Note ** | 0.0335 | <0.001 |

| Equally-owned enterprise | -0.150Note ** | 0.0316 | <0.001 |

| Non-recent immigrant | |||

| Majority women-owned enterprise | 0.042Note * | 0.0198 | 0.0358 |

| Equally-owned enterprise | -0.199Note ** | 0.0217 | <0.001 |

| Has spouse | |||

| Majority women-owned enterprise | -0.375Note ** | 0.0191 | <0.001 |

| Equally-owned enterprise | 1.839Note ** | 0.0361 | <0.001 |

| Rural | |||

| Majority women-owned enterprise | -0.150Note ** | 0.0259 | <0.001 |

| Equally-owned enterprise | 0.305Note ** | 0.0242 | <0.001 |

| Children younger than 7 years old | |||

| Majority women-owned enterprise | 0.710Note ** | 0.0404 | <0.001 |

| Equally-owned enterprise | 0.449Note ** | 0.0431 | <0.001 |

| Children aged 7 to 16 years | |||

| Majority women-owned enterprise | 0.784Note ** | 0.0402 | <0.001 |

| Equally-owned enterprise | 0.293Note ** | 0.0470 | <0.001 |

| Five-year savings ($1,000s) | |||

| Majority women-owned enterprise | -0.015Note ** | 0.0028 | <0.001 |

| Equally-owned enterprise | -0.056Note ** | 0.0035 | <0.001 |

| Five-year family income ($1,000s) | |||

| Majority women-owned enterprise | 0.000Note * | 0.0001 | 0.0358 |

| Equally-owned enterprise | -0.001Note ** | 0.0001 | <0.001 |

| Five-year income shock | |||

| Majority women-owned enterprise | 0.102Note ** | 0.0185 | <0.001 |

| Equally-owned enterprise | -0.004 | 0.0191 | 0.8454 |

Sources: Statistics Canada, Canadian Employer–Employee Dynamics Database and authors' calculations. |

|||

A key takeaway from the results is that these characteristics are significant predictors of the ownership type of the enterprise. If any of these characteristics are related to labour productivity, then the groups of enterprises are not comparable without adjustment.

The performance of the generalized propensity score model can be evaluated via balancing tests (Table 4). Balancing tests determine whether propensity score estimation reduces bias between groups, where bias is measured as the difference in means of characteristics (Smith and Todd 2005). In this case, propensity scores are used to weight records, rather than to drop records and therefore, the balancing test compares the weighted and unweighted means. For example, when considering unweighted means, 14.2% of principal owners of men-owned enterprises and 12.7% of principal owners of women-owned enterprises live in a rural area, respectively (Table 4). The absolute percentage difference is 10.7%. When considering the means weighted using the generalized propensity scores, the percentages are 13.9% and 14.2% for men-owned and women-owned enterprises, respectively. The absolute percentage difference is 2.3%. The bias falls from 10.7% to 2.3%, or by 78.7%.

The model performs well, with bias being reduced for all but one characteristic (age) for women-owned enterprises, and all characteristics for equally owned enterprises. Referring back to the results of the regression model, the coefficient on Age for women-owned enterprises is small compared to other coefficients, so it is logical that age is the characteristic that is not balanced by the model.

| Variable and sample | MOE | WOE | EOE | Bias WOE-to-MOE | Bias change | Bias EOE-to-MOE | Bias change |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mean | percent | ||||||

| Age | |||||||

| Unadjusted | 41.8 | 41.5 | 42.3 | 0.70 | 201.50 | 1.30 | -58.90 |

| Adjusted | 42.7 | 41.8 | 42.5 | 2.20 | Note ...: not applicable | 0.50 | Note ...: not applicable |

| Recent immigrant | |||||||

| Unadjusted | 10.80 | 7.70 | 11.60 | 28.10 | -80.90 | 7.80 | -70.10 |

| Adjusted | 8.40 | 8.80 | 8.60 | 5.40 | Note ...: not applicable | 2.30 | Note ...: not applicable |

| Non-recent immigrant | |||||||

| Unadjusted | 27.90 | 29.80 | 26.10 | 7.10 | -33.00 | 6.40 | -78.10 |

| Adjusted | 31.50 | 30.00 | 31.10 | 4.70 | Note ...: not applicable | 1.40 | Note ...: not applicable |

| Has spouse | |||||||

| Unadjusted | 73.90 | 67.10 | 94.60 | 9.30 | -97.90 | 28.00 | -99.90 |

| Adjusted | 93.00 | 93.10 | 92.90 | 0.20 | Note ...: not applicable | 0.00 | Note ...: not applicable |

| Rural | |||||||

| Unadjusted | 14.20 | 12.70 | 19.70 | 10.70 | -78.70 | 38.60 | -98.60 |

| Adjusted | 13.90 | 14.20 | 13.80 | 2.30 | Note ...: not applicable | 0.50 | Note ...: not applicable |

| Children younger than 7 years old | |||||||

| Unadjusted | 3.10 | 7.50 | 6.30 | 138.70 | -94.50 | 100.50 | -95.40 |

| Adjusted | 8.10 | 7.50 | 7.70 | 7.60 | Note ...: not applicable | 4.60 | Note ...: not applicable |

| Children aged 7 to 16 years | |||||||

| Unadjusted | 2.90 | 7.60 | 4.90 | 161.10 | -92.70 | 69.10 | -90.90 |

| Adjusted | 6.80 | 6.00 | 6.40 | 11.80 | Note ...: not applicable | 6.30 | Note ...: not applicable |

| Five-year savings ($1,000s) | |||||||

| Unadjusted | 2.1 | 1.9 | 1.6 | 8.80 | -9.90 | 22.90 | -94.60 |

| Adjusted | 1.9 | 1.8 | 1.9 | 7.90 | Note ...: not applicable | 1.20 | Note ...: not applicable |

| Five-year family income ($1,000s) | |||||||

| Unadjusted | 55.3 | 52.3 | 48.2 | 5.40 | -35.60 | 12.80 | -77.30 |

| Adjusted | 51.5 | 49.7 | 50 | 3.50 | Note ...: not applicable | 2.90 | Note ...: not applicable |

| Five-year income shock | |||||||

| Unadjusted | 63.50 | 67.30 | 62.10 | 6.00 | -74.60 | 2.20 | -79.40 |

| Adjusted | 65.90 | 64.90 | 65.60 | 1.50 | Note ...: not applicable | 0.50 | Note ...: not applicable |

|

... not applicable Notes: MOE = Majority men-owned enterprise. WOE = Majority women-owned enterprise. EOE = Equally owned enterprise. Variable definitions in appendix. The matched mean is the weighted mean using the generalized propensity scores as weights. Firms without a two-digit North American Industry Classification System code are excluded as unclassified firms. Sources: Statistics Canada, Canadian Employer–Employee Dynamics Database and authors' calculations. |

|||||||

4.2 Results of the labour-productivity model

Table 5 presents the results of the baseline model and the full model, unweighted and weighted, estimated using labour productivity three years after entry, and pooled data from 2006 through 2017. The baseline model without weights (column 1), estimates that women-owned and equally owned enterprises are less productive than men-owned enterprises, but the magnitude of the gap is much larger for women-owned enterprises. Adding the weights to this model (column 2) lowers the gaps, but they are still statistically significant. A decrease in the gaps is an expected result since the weights adjust for differences in owner characteristics between groups (for example, they adjust for the fact that owners of men-owned enterprises have higher average family income in the five years before entry).

Care must be taken when comparing the models with and without prior experience. Comparing the unweighted models, the addition of prior experience (column 3) decreases the coefficient on WOE from -0.1979 to -0.2167, but the former coefficient represents the overall productivity gap while the latter does not. Rather, the second coefficient represents the productivity gap (in log-odds) between women-owned enterprises and men-owned enterprises where the owners do not have prior industry experience. For owners with experience, the interaction term must also be considered, as shown above in Table 2.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline model, unweighted | Baseline model, weighted | Full model, unweighted | Full model, weighted | |

| ln(Labour productivity three years after entry) | ||||

| Intercept | ||||

| Estimate | 11.4279Note ** | 11.302Note ** | 11.3252Note ** | 11.2541Note ** |

| Standard error | (0.6416) | (1.2457) | (0.6411) | (1.2444) |

| WOE | ||||

| Estimate | -0.1979Note ** | -0.1834Note ** | -0.2167Note ** | -0.2087Note ** |

| Standard error | (0.0107) | (0.0102) | (0.0115) | (0.0111) |

| EOE | ||||

| Estimate | -0.0944Note ** | -0.0617Note ** | -0.0878Note ** | -0.0624Note ** |

| Standard error | (0.0106) | (0.0099) | (0.0113) | (0.0107) |

| Prior industry experience | ||||

| Estimate | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | 0.0571Note ** | 0.0154 |

| Standard error | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | (0.0131) | (0.0178) |

| WOE Prior industry experience | ||||

| Estimate | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | 0.1814Note ** | 0.2072Note ** |

| Standard error | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | (0.0305) | (0.0275) |

| EOE Prior industry experience | ||||

| Estimate | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | -0.0206 | 0.0116 |

| Standard error | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | (0.0323) | (0.0276) |

| Enterprise controls | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Industry controls | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| R-squared | 0.2737 | 0.2791 | 0.2751 | 0.2806 |

| Observations | 52,046 | 51,351 | 52,046 | 51,351 |

... not applicable

Sources: Statistics Canada, Canadian Employer–Employee Dynamics Database and authors' calculations. |

||||

With or without weights, the full model estimates that for all groups, having prior industry experience relatively increases labour productivity, but that the gains are significantly larger for owners of women-owned enterprises. Similar to the baseline model, weighting changes the estimated coefficients so that the labour-productivity gaps are somewhat smaller. The change in the estimates between the unweighted and weighted model suggests that it is important to adjust for owner characteristics—such as prior personal income—when estimating the labour-productivity gap.

The model provides causal evidence that majority women-owned enterprises receive greater returns to prior experience, but cannot be used to explain why this occurs. One theory for why prior experience matters is that it allows individuals to obtain knowledge and skills that are relevant to the tasks in their current role (Dokko et al. 2009). If this is the mechanism, our results would imply that knowledge and skills gained through prior experience as a business owner provide greater benefits to women owners. One possible explanation is that within companies women are often limited to specific roles, and may have greater difficulty gaining management experience compared to men. Business ownership gives women a method of accumulating knowledge and skills related to a wide variety of tasks, including tasks concerning the division of labour. This relates to the finding of Flabbi et al. (2019) that female executives increase the productivity of firms because they are better at assigning female employees to tasks that match their skills. We explore this mechanism more in the next subsection.

Other mechanisms, which cannot be tested, cannot be excluded. One conjecture is that experienced entrepreneurs have different preferences than inexperienced entrepreneurs, and that this effect is greater for women. Survey data from The United States provides evidence that women are less likely to have the goal of growing their enterprise and more likely to prefer working less than full-time (Fairlie and Robb 2009). With this in mind, inexperienced entrepreneurs may not be as comparable as experienced entrepreneurs because they are more likely to have preferences towards part-time work and slow growth. Having prior experience may also allow women to better overcome the barriers commonly faced by women entrepreneurs, such as the inability to obtain full financing (Rosa and Sylla 2016).

Relative to the baseline model without weights, using the full model with weights reduces the labour-productivity gap for both women-owned and equally owned enterprises (Table 6). According to the baseline model and relative to men-owned enterprises, women-owned enterprises are 18.0% less productive and equally owned enterprises are 9.1% less productive.

| Women-owned enterprises | Equally owned enterprises | |

|---|---|---|

| percent | ||

| Model with no experience and no weights | -18.00Note ** | -9.10Note ** |

| Model with experience and weights | ||

| Overall | -16.50Note ** | -5.90Note ** |

| No prior industry experience | -20.90Note ** | -6.10Note ** |

| Has prior industry experience | -0.20 | -5.00Note * |

Sources: Statistics Canada, Canadian Employer–Employee Dynamics Database and authors' calculations. |

||

By using the full model with weights, the labour-productivity gaps decrease to 16.5% and 5.9%, respectively. Among enterprises where the owners have prior industry experience, the gaps are 0.2% and 5.0%, respectively. The gap is not statistically significant between men- and women-owned enterprises, suggesting that there is no significant labour productivity difference between men and women-owned enterprises when the owners have prior industry experience.

4.2.1 Results of the labour-productivity model with heterogeneous effects by number of employees

In this section we present the results of the extended model, which includes an additional interaction term between prior industry experience and the number of employees, for owners of women-owned enterprises only. The coefficient estimate is positive, which suggests that the productivity gains from prior industry experience are greater in firms with more employees. This is consistent with our theory that the gains to prior experience for owners of women-owned enterprises could come from accumulated knowledge and skills related to the management of labour. This is because these skills would be relatively more important as the number of employees increases.

| Ln(Labour productivity three years after entry) | |

|---|---|

| Intercept | |

| Estimates | 11.2511Note ** |

| Standard error | (1.2442) |

| WOE | |

| Estimates | -0.2087Note ** |

| Standard error | (0.0111) |

| EOE | |

| Estimates | -0.0627Note ** |

| Standard error | (0.0107) |

| Prior industry experience | |

| Estimates | 0.0181 |

| Standard error | (0.0178) |

| WOE Prior industry experience | |

| Estimates | 0.1668Note ** |

| Standard error | (0.0294) |

| EOE Prior industry experience | |

| Estimates | 0.0103 |

| Standard error | (0.0276) |

| WOE prior industry experience employees | |

| Estimates | 0.0042Note ** |

| Standard error | (0.0011) |

| Enterprise controls | Yes |

| Industry controls | Yes |

| R-squared | 0.2808 |

| Number of observations | 51,351 |

Sources: Statistics Canada, Canadian Employer–Employee Dynamics Database and authors' calculations. |

|

5 Conclusion

This paper uses recently developed administrative data on the gender of enterprise owners to examine differences in the labour productivity of firms between 2005 and 2017. Analysis finds that even when industry and other enterprise characteristics are controlled for, women-owned and equally owned enterprises have significantly lower labour productivity than men-owned enterprises, and the difference is larger for women-owned enterprises than it is for equally owned enterprises. By controlling for owner characteristics and adding prior industry experience as a control, the analysis finds that prior industry experience of the principal owner increases relative labour productivity and this effect is much larger in women-owned enterprises. This means that the labour-productivity gap between men- and women-owned enterprises is lower among enterprises with experienced owners than among enterprises with inexperienced owners. Controlling for prior industry experience also reduces the overall labour-productivity gap between all men-owned enterprises and all women-owned enterprises.

The result that owners of women-owned enterprises experience greater gains from prior experience could be explained by various mechanisms, but we find some evidence that accumulated knowledge and skills related to the division of labour is more beneficial for women. However, we cannot rule out other factors, such as preferences. Also beyond the scope of this study, the accumulated knowledge and skills acquired in other industries could potentially have an influence that differs across industries. Nevertheless, this research shows that it is important to control for owner characteristics and prior industry experience when comparing the labour productivity of groups of enterprises.

These results are relevant for policy making in that they provide causal insights into the factors influencing the relative labour productivity of women-owned firms. In particular, the findings support the fact that policies aiming to reduce labour-productivity gaps among groups of enterprises could target the experience of business owners and especially experience in the industry of the enterprise owned.

Appendix

| Variable/Concept | Source | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Variables used to restrict dataset | ||

| Entrant | T2 Schedule 50 | Individual who is a business owner (i.e., present in T2 Schedule 50) in the current year but not the prior year. The dataset comprises cohorts of entrants from 2006 through 2017. |

| Employees | T2 (NALMF) | The number of employees. The dataset includes firms with at least one employee. The owner may be included in the count depending on whether they issued themselves a T4. This variable is also used as a control in regression, since firm size may predict performance. |

| Gender of owner | T2 Schedule 50 | If the shares owned by women (men) are greater than or equal to 51%, the enterprise is considered women-owned (men-owned); if women and men own 50% of the shares, the enterprise is considered equally owned. Firms where the gender of the owner cannot be determined are excluded from the study. |

| Labour productivity | T2 (NALMF) | Value-added output divided by the total number of employees where value-added output is computed as the sum of profit (net income before tax), labour costs (T4 payroll) and capital cost allowance (as a measure of depreciation of capital). |

| Variables used in propensity score estimation | ||

| Age | T1 | Age of the individual, derived from the date of birth. When missing, imputed using other years. |

| Immigrant | Immigrant landing file | Indicate whether the individual is not Canadian-born. |

| Recent immigrant | Immigrant landing file | Recent immigrants are the individuals whose year of landing (i.e., year when they enter Canada as a permanent resident) is within five years of the year of entry into business ownership. |

| Has spouse | T1FF | An indicator that is equal to 1 when the individual was married or in a common-law relationship in the year preceding entry. |

| Rural | T1 | The second character of the postal code is indicative of the coverage of the postal code. A postal code with a "0" in the second character is classified as "rural" and all other postal codes are considered as urban by Canada Post. A dummy indicator is created flagging whether the second digit of the individual's postal code is 0. |

| Children younger than 7 years | T1FF | Dummy variable indicating whether the family of the owner has children younger than 7 years old for whom child care expenses have been claimed. The family is based on the census family concept. |

| Children aged 7 to 16 years | T1FF | Dummy variable indicating whether the family of the owner has children from 7 through 16 years old for whom child care expenses have been claimed. |

| Five-year savings | T1 | Contributions to a Registered Pension Plan (RPP) or Registered Retirement Saving Plan (RRSP). Other types of savings are not available. Cumulative savings are obtained by summing available information for the five years preceding entry. |

| Five-year family income | T1FF | The family total income after tax calculated, deflated using CPI (unit: constant 2006 dollars). The cumulative income is obtained by summing available information for the five years preceding entry. Family is based on the census family concept. |

| Five-year income shock | T1FF | Dummy variable indicating whether an individual experienced a negative income shock of at least 10% within the five years preceding entry. |

| Variables used in regression analysis | ||

| Prior industry experience | T1-FD, T2-Schedule 50 and T4 and T2 (NALMF) | The working path is established over the last five years. The working path is the list of firms where the owner had an incorporated business. The path is determined using the business number from the T2 Schedule 50. Experience must occur in the same industry as defined by 2-digit NAICS. |

| Employees | T2 (NALMF) | The number of employees. The owner may be included in the count depending on whether they issued themselves a T4. |

| Research and development | T2 (NALMF) | Funds spend on research and development in the year of entry, according to T2 tax values. |

| Total assets | T2 (NALMF) | Total assets in the year of entry, according to T2 tax values. This is a measure of capital. |

| Industry | T2 (NALMF) | Industry dummies based on 2-digit NAICS. Firms without a 2-digit NAICS are excluded as unclassified firms. |

| Province of enterprise | T2 (NALMF) | Dummies for the main province or territory of operation of the enterprise. |

| Cohort | T2 (NALMF) | Dummies for the cohort (2006 through 2017) of the enterprise. An enterprise belongs to a cohort when it is an entrant in that year. |

|

Notes: NAICS: North American Industry Classification System; NALMF: National Accounts Longitudinal Microdata File; T1: Income Tax and Benefit Return; T1 BD: T1 Business Declaration; T1 FD: T1 Financial Declaration; T1FF: T1 Family File; T2: Corporation Income Tax Return Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Employer–Employee Dynamics Database. |

||

| ln(Labour productivity, year of entry) | ln(Labour productivity, three years after entry) | ln(Labour productivity, five years after entry) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | |||

| Estimates | 10.0614Note ** | 11.2541Note ** | 11.1602Note ** |

| Standard error | (0.6916) | (1.2444) | (1.4754) |

| WOE | |||

| Estimates | -0.1796Note ** | -0.2087Note ** | -0.2102Note ** |

| Standard error | (0.0094) | (0.0111) | (0.0136) |

| EOE | |||

| Estimates | -0.0054 | -0.0624Note ** | -0.0659Note ** |

| Standard error | (0.0092) | (0.0107) | (0.0132) |

| Relevant prior experience | |||

| Estimates | 0.0971Note ** | 0.0154 | 0.0144 |

| Standard error | (0.0151) | (0.0178) | (0.0218) |

| WOE relevant prior experience | |||

| Estimates | 0.2106Note ** | 0.2072Note ** | 0.1334Note ** |

| Standard error | (0.0233) | (0.0275) | (0.0348) |

| EOE relevant prior experience | |||

| Estimates | -0.0409 | 0.0116 | 0.0552 |

| Standard error | (0.0237) | (0.0276) | (0.0343) |

| Enterprise controls | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Industry controls | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| R-squared | 0.2656 | 0.2806 | 0.2836 |

| Number of observations | 85,887 | 51,351 | 33,390 |

Sources: Statistics Canada, Canadian Employer–Employee Dynamics Database and authors' calculations. |

|||

References

Allison, P.D. 2012. Logistic Regression Using SAS: Theory and Application. SAS institute.

Bates, T. 2002. “Restricted access to markets characterizes women-owned businesses.” Journal of Business Venturing 17: 313–324.

Brush, C. 1992. “Research on women business owners: Past trends, a new perspective and future directions.” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice: 5–30.

Brush, C., P. Greene, L. Balachandra, and A. Davis. 2018. “The gender gap in venture capital-progress, problems, and perspectives.” Venture Capital 20 (2): 115–136.

Couture, L., and S. Houle. 2020. Survival and Performance of Start-ups by Gender of Ownership: A Canadian Cohort Analysis. Analytical Studies Branch Research Paper Series, no. 450. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 11F00019M. Ottawa: Statistics Canada.

Dokko, G., S.L. Wilk, and N.P. Rothbard. 2009. “Unpacking prior experience: How career history affects job performance.” Organization Science 20 (1): 51–68.

Du Rietz, A., and M. Henrekson. 2000. “Testing the female underperformance hypothesis.” Small Business Economics 14 (1): 1–10.

Fairlie, R., and A. Robb. 2009. “Gender differences in business performance: evidence from the characteristics of business owners survey.” Small Business Economics 33 (4): 375–395.

Fischer, E. 1992. “Sex differences and small business performance among Canadian retailers and service providers.” Journal of Small Business and Entrepreneurship 9 (4): 2–13.

Flabbi, L., M. Macis, A. Moro, and F. Schivardi 2019. “Do female executives make a difference? The impact of female leadership on gender gaps and firm performance.” Economic Journal 129 (622): 2390–2423.

Grekou, D. 2020. Labour Market Experience, Gender Diversity and the Success of Women-owned Enterprises. Analytical Studies Branch Research Paper Series, no. 447. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 11F00019M. Ottawa: Statistics Canada.

Grekou, D., and H. Liu. 2018. The Entry into and Exit out of Self-employment and Business Ownership in Canada. Analytical Studies Branch Research Paper Series, no. 407. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 11F0019M. Ottawa: Statistics Canada.

Marlow, S., and M. McAdam. 2013. “Gender and entrepreneurship: Advancing debate and challenging myths; exploring the mystery of the under-performing female entrepreneur.” International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviour & Research 19 (1): 114–124.

Robb, A.M., and J. Watson. 2012. “Gender differences in firm performance: Evidence from new ventures in the United States.” Journal of Business Venturing 27 (5): 544–558.

Rosa, J.M., and D. Sylla. 2016. A Comparison of the Performance of Female-owned and Male-owned Small and Medium Enterprises. Report from the Centre for Special Business Projects, Statistics Canada.

Rosa, P., S. Carter., and D. Hamilton. 1996. “Gender as a determinant of small business performance: Insights from a British study.” Small Business Economics 8 (6): 463–478.

Smith, J.A., and P.E. Todd. 2005. “Does matching overcome LaLonde’s critique of nonexperimental estimators?” Journal of Econometrics 125 (1–2): 305–353.

Statistics Canada. 2020. North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) Canada 2017 Version 3.0. Ottawa: Statistics Canada. Available at: https://www23.statcan.gc.ca/imdb/p3VD.pl?Function=getVD&TVD=1181553 (accessed August 31, 2020).

- Date modified: