Analytical Studies Branch Research Paper Series

Moving Forward on Well-being (Quality of Life) Measures in Canada

Skip to text

Text begins

Abstract

There is continued and growing awareness of the need to integrate information on economic, social and environmental conditions to better measure the well-being or quality of life and progress of nations, a need to move ‘Beyond GDP.’ Many countries are moving beyond just the measurement and monitoring of indicators to a more fulsome integration of quality of life into the policy process. The Government of Canada is moving in a similar direction. This provides Statistics Canada with an opportunity to take stock and review the status of well-being measurement in Canada. The overall objective of this paper is to provide an overview of selected approaches to measuring and reporting well-being in Canada and internationally, and to identify opportunities to move forward with new and enhanced measures to address current social, economic and environmental issues facing Canada that may impact the well-being of its population. This report highlights six trends and proposes a range of data development and measurement activities to advance well-being measurement in the following key areas: digitization, affordability and economic uncertainty, the quality of jobs, social cohesion, neighbourhoods and the built environment and climate change.

Start of text box

Note to Readers:

This report was prepared prior to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, which has had and continues to have unprecedented health, social, and economic impacts on the quality of the lives of Canadians. This has only served to further amplify the importance of moving forward with the further development of a comprehensive quality of life framework that integrates social, economic and environmental measures to guide and monitor progress related to the pandemic recovery. The deliberations and recommendations in this report remain, if not are more, relevant given the new context and reality Canadians are facing.

End of text box

Executive summary

There is continued and growing awareness of the need to integrate information on economic, social and environmental conditions to better measure the well-being and progress of nations, a need to move ‘Beyond GDP’ to account for social and environmental outcomes in addition to standard economic measures. The proliferation of well-being measures have moved leaders in some countries to go beyond just the measurement and monitoring of these indicators to a more fulsome integration of well-being into the policy process. The Government of Canada is moving in a similar direction. This provides Statistics Canada with an opportunity to take stock and review the status of well-being measurement in Canada. As the country’s national statistical organization responsible for many of the indicators used in current well-being frameworks, Statistics Canada is well positioned to conduct such a stock-take and identify opportunities to strengthen the statistical system with respect to quality of life measurement to support the federal government plans moving forward. The overall objective of this paper is to provide an overview of selected approaches to measuring and reporting well-being in Canada and internationally, and to identify opportunities to move forward with new and enhanced measures to address current social, economic and environmental issues facing Canada that may impact the well-being of its population.

The review of well-being frameworks focusses on three well-being multi-dimensional frameworks national in scope and to which Statistics Canada is a major contributor of data for the indicators—the Canadian Index of Well-being (University of Waterloo), the Better Life Initiative (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development), and Sustainable Development Goals (United Nations). While each framework has been developed independently to meet different needs and goals, there is a clear convergence of domains into four key areas: society, economy, environment and institutions. Common domains include health, living standards, jobs and employment, education, time use, and community vitality. Other approaches to well-being measurement include the subjective approach which advocates an umbrella measure of quality of life (e.g., life satisfaction) and efforts to integrate well-being measures in the System of National Accounts.

Internationally, countries are moving beyond the simple reporting of well-being measures toward the integration of this concept in the policy process. Those countries who moved forward with this approach have developed largely multi-dimensional indicator based well-being frameworks that have been led by key government departments (e.g., Finance or Treasury), created through consultations, and leveraged measurement expertise from their respective national statistical organizations. In many cases, governments have used a range of legislative and policy mechanisms to support the use of well-being frameworks in the policy process, including mandatory reporting of well-being indicators.

In 2019, the Minister of Innovation, Science and Industry, as the Minister responsible for Statistics Canada, was tasked with supporting the Minister of Middle Class Prosperity and Associate Minister of Finance to better incorporating quality of life measurements into decision-making and budgeting. This represents a unique opportunity to take a critical look at the current state of well-being measurement in Canada. The results of this paper point to opportunities to advance a new government-led framework that both builds on existing well-being measures and advances new measures to address gaps related to the current social, economic and environmental trends impacting the lives of Canadians. This report highlights six trends and proposes a range of data development and measurement activities to advance well-being measurement in the following key areas: digitization, affordability and economic uncertainty, the quality of jobs, social cohesion, neighbourhoods and the built environment, and climate change.

1 Introduction

There is continued and growing awareness of the need to integrate information on economic, social and environmental conditions to better measure the well-being and progress of nations. High-profile reports since the last recession have coalesced around the notion that the measurements of economies have not sufficiently reflected the experiences of citizens nor captured the true costs of production (Stiglitz, Sen and Fitoussi 2009). They argue that the focus on aggregate economic outcomes is misplaced when growth is not inclusive or when environmental degradation and negative social outcomes are not fully accounted for. In this context, there is increased focus among governments at all levels to look at the economy, civil society and environment in an integrated manner that goes ‘Beyond GDP.’

At the United Nations (UN), this effort is reflected in the 2030 Agenda of leaving no one behind and the development of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).Note At the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and in several member countries, new models that make better use of well-being indicators are being used to measure, track and analyze well-being and sustainability. Canada, too, is moving in this direction. Canada’s statistical infrastructure continues to evolve in response to the many changes in its economy, society and environment, and federal departments are implementing new indicator frameworks to guide, monitor and evaluate policies and programs. Work is also on-going at the provincial and municipal levels and within academia and non-governmental organizations.

In late 2019, the new Minister of Middle Class Prosperity was tasked:

…to better incorporate quality of life measurements into government decision-making and budgeting, drawing on lessons from other jurisdictions such as New Zealand and Scotland. (Justin Trudeau, Prime Minister of Canada 2019)

This increases both the importance of, and demands upon, statistical measures of quality of life, alternatively titled well-being, as the government seeks to embed this concept more deeply in the policy process.

The understanding and definition of well-being is thus central within this context. Various approaches to well-being are evident in the research literature and international policy community. The overall objective of this paper is to provide an overview of selected approaches to measuring and reporting on well-being and identify opportunities to move forward with new and enhanced measures to address current social, economic and environmental issues facing Canada that may impact the well-being of its population.

The paper is divided into six sections. Sections 2 to 4 provide an overview of three approaches to measuring well-being, including well-being indicator frameworks, the subjective well-being approach, and briefly, the System of National Accounts (SNA). Emphasis is on the first two approaches as they are most germane to the mandated task above. Section 2 focuses more specifically on three well-being indicator frameworks which are multi-dimensional and national in scope and to which Statistics Canada is a major contributor of indicators—the Canadian Index of Well-being (University of Waterloo), the Better Life Initiative (OECD), and Sustainable Development Goals (UN). This section also includes insights regarding how the concept of well-being and related indicators are being more closely integrated in the policy process.

Section 5 draws attention to economic, social and environmental issues that have potential impacts for the well-being of citizens including digitization, job quality, affordability and economic uncertainty, the role of neighbourhoods and built environment and climate change. These issues are raised and discussed in the context of implications for well-being being measurement, highlighting the work Statistics Canada is doing to advance well-being measures as well as identify remaining gaps. While there are a broad range of indicators currently used to monitor and track the well-being of Canadians, there are opportunities to further develop new and timely measures to address these key issues which are also the focus of policy makers.

Finally, Section 6 draws the main elements of Statistics Canada’s strategy for engaging in, and supporting the Government of Canada’s objective of incorporating well-being within the policy process and advancing measurement in key areas.

2 Well-being indicator frameworks

Well-being indicator frameworks are being developed and used for policy purposes in a growing number of countries. Such frameworks typically comprised various aspects, or domains, identified as important contributors to, or elements of, well-being. Multi-dimensional frameworks typically include domains such as health, education, work, material conditions, social ties, and environment, with a set of indicators presented within each. Differences in indicator scores can be tracked over time or compared between groups to gauge improvements or deteriorations in conditions. Indicators are sometimes combined into an aggregated well-being index or set of well-being indices. The well-being indicator field itself has a fifty-year history, as discussed in a recent edition of Social Indicators Research (volume no. 135) (Land and Michalos 2018).

Over the last decade or so, the application of well-being indicator frameworks have become more prominent in public policy discussions. The United Kingdom (U.K.) was one of the first countries to measure well-being with the implementation of their Measuring Well-being Program in 2010 (Everett 2015), with a Measures of National Well-being Dashboard (United Kingdom. Office of National Statistics 2019) published by the Office of National Statistics. France and Wales introduced statutory requirements to report to Parliament regularly on the state of national well-being to inform policy development. In New Zealand, the Living Standards Framework (LSF) was developed by the New Zealand Treasury (Smith 2018). The LSF Dashboard, first released in 2018, informs the New Zealand Treasury’s advice to Ministers on priorities for improving wellbeing (Government of New Zealand. The Tresury n.d.). This initiative led to the first well-being budget, which prioritizes a range of initiatives in the areas of mental health, vulnerable populations, and an environmentally sustainable economy. The outcomes of their budget will be measured using their Treasury’s LFS (Government of New Zealand 2019).

Initiatives in other countries are profiled in Exton and Shinwell (2018). Further information regarding international frameworks is available upon request.

2.1 Selected well-being indicator frameworks

In recent years, as the recognition of the importance of well-being has been emphasized throughout the world, a multitude of well-being frameworks have been developed both in Canada and beyond (appendices A, B and C provide an overview of some of these). Many of these frameworks focus on individual-level well-being, while others focus on families, children and youth, or communities. A comprehensive review of these frameworks is useful, if not essential, in understanding well-being from various perspectives and within different societal contexts.

For the purposes of this paper, three specific well-being indicator frameworks, to which Statistics Canada is a primary contributor of data and/or indicators, are considered in detail.

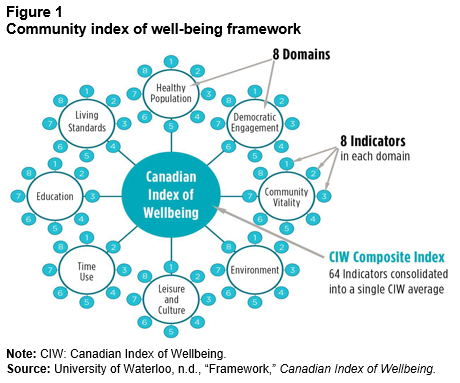

2.1.1 Canadian Index of Well-being

The Canadian Index of Well-being (CIW) began in the early 2000s under the auspices of the Atkinson Charitable Foundation and is designed to measure the economic, health, social and environmental well-being of Canadians. The initiative commenced with three rounds of public consultations and with input from researchers, indicator users, and various agencies and organizations. This culminated in the identification of a set of core values underpinning well-being (i.e., fairness, diversity, equity, inclusion, health, safety, economic security, democracy and sustainability) and a set of 8 domains of life that contribute to, and affect, the well-being of Canadians (CIW 2019; Smale 2019; Michalos et al. 2011). These domains include community vitality, democratic engagement, education, environment, healthy populations, leisure and culture, living standards, and time use (see Figure 1). Each domain is populated with 8 indicators. The overall CIW framework thus includes 64 indicators, 8 sub-indices and the aggregate CIW itself. Each of the 8 indicators in each domain is assigned equal weight in the construction of the domain index, and each of the 8 domain sub-indices are assigned equal weight in the construction of the CIW overall.

Description for Figure 1

The title of Figure 1 is “Community index of well-being framework.”

The figure consist of a large oval surrounded by medium-sized ovals. The medium-sized ovals have the same size. Each medium-sized oval is connected to the large one with a straight line. Around each medium-sized oval are eight small ovals. The small ovals are of the same size. They are connected to the medium-sized ovals with a straight line. The background colour of the large and small ovals as well as the frame around the medium-sized ovals is the same colour (blue). The medium-sized ovals have a white background.

The text in the large oval is “Canadian Index of Wellbeing.” It is white. The tip of a grey arrow is touching the large oval. The text at the beginning of the grey arrow, which is situated outside the diagram, in the lower-right area of the image, is “CIW Composite Index, 64 indicators consolidated into a single CIW average.” (CIW is the abbreviation for “Canadian Index of Wellbeing.”)

The text in each one of the medium-sized ovals is different. It is as follows, starting from the upper-portion of the diagram: “Healthy Population,” “Democratic Engagement,” “Community Vitality,” “Environment,” “Leisure and Culture,” “Time Use,” “Education,” and “Living Standards.” The small ovals around each medium-sized oval are numbered from 1 to 8. The numbers are white in colour.

The tip of one grey arrow touches the medium-sized oval “Healthy Population” and the tip of another touches the medium-sized oval “Demographic Engagement.” The beginning of each of these two grey arrows converges to the text “8 Domains” written in black. This text is located outside the diagram in the top right area of the image.

The tip of one grey arrow touches the small oval “1” attached to the “Community Vitality” medium-sized oval, the tip of another grey arrow touches the small oval “2,” and the tip of another grey arrow touches the small oval “3” attached to the same medium-sized oval. The beginning of each of these three arrows converge to the text “8 Indicators in each domain” written in black. This text is located outside the diagram in the upper right portion of the image.

This diagram conveys the following message: The medium-sized ovals with their respective labels (Healthy Population, Democratic Engagement, Community Vitality, Environment, Leisure and Culture, Time Use, Education, Living Standards) represent the eight domains of life that contribute to, and affect, the well-being of Canadians. Each domain has an index and is populated with eight indicators represented by the eight small ovals numbered 1 to 8. Each of the eight indicators in each domain is assigned equal weight in the construction of the domain index, and each of the domain sub-indices are assigned equal weight in the construction of the Canadian Index of Wellbeing. The overall Canadian Index of Wellbeing includes 64 indicators.

The note and source of Figure 1 read as follows:

Note: CIW: Canadian Index of Wellbeing.

Source: University of Waterloo, n.d., “Framework,” Canadian Index of Wellbeing.

The CIW draws on a wide range of data sources, although information from Statistics Canada is used most extensively (e.g., General Social Survey [GSS], Canadian Community Health Survey, Labour Force Survey, Census of Population). Indicators are available at different frequencies, from annually to every five years.

The most recent annual report of the CIW was published in 2016, providing results up to 2014. In addition to national-level results for Canada, the CIW provides provincial-level information for Ontario, Nova Scotia, and Saskatchewan. The CIW experience in local communities across Canada is noteworthy. The CIW developed its Community Well-being Survey, with the questionnaire designed to collect information in each of the eight domains applying many of the questions available on Statistics Canada surveys such as the GSS. Between 2012 and 2020, the survey was fielded in 11 locations across Canada, as the CIW responded to local needs and worked in close collaboration with local stakeholders.Note A collaborative initiative involving the CIW and Engage Nova Scotia, a non-profit organization, is currently underway. Survey responses have been collected from almost 13,000 individuals residing in 10 regions of the province using a non-probabilistic sampling technique.

In 2010, the CIW was moved from the Atkinson Foundation to the University of Waterloo, Faculty of Applied Health Science, where it has been headquartered since. Discussions are currently underway to move the initiative to a new institution.

2.1.2 Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development—Better Life Initiative (How’s Life?)

The OECD’s Better Life Initiative to measure well-being and progress (OECD n.d.) was launched in May 2011 in response to the recommendations in the 2009 report of the Commission on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress (Stiglitz, Sen and Fitoussi 2009). The Better Life initiative is composed of three components—building the evidence base (i.e., Framework, How’s Life?), building better measures and stimulating debate—and is designed to support the OECD’s mandate of “better policies for better lives.” The OECD Well-being framework builds on national and international initiatives, the academic literature, the recommendations of Stiglitz, Sen and Fitoussi (2009), and input from National Statistical Offices (NSOs) represented on the OECD Committee on Statistics and Statistical Policy.

The How’s Life? framework identifies three pillars for understanding and measuring well-being—quality of life, material conditions and sustainability. These pillars are supported by 11 dimensions of current well-being and 4 sources of capital supporting future well-being. The 11 dimensions of current well-being include 8 reflecting quality of life (health status, work-life balance, knowledge and skills, social connections, civic engagement and governance, environmental quality, personal security, and subjective well-being) and three reflecting material conditions (income and wealth, jobs and earning, and housing). In addition to tracking progress over time, the Better life data are used to measure and monitor inequalities across a range of dimensions, such as education, age, income, gender, and migrant status (OECD 2017).

The How’s Life? report is published every two years and provides information on well-being across approximately 40 countries. The results are targeted to a broad audience using a range of dissemination products, such as regional and country-specific reports, downloadable data, and an online platform (OECD Better Life Index n.d.) that enables individuals to construct a customized well-being index using the values (or weights) that they themselves attach to each of the 11 well-being dimensions.

How’s Life? is supported by data from national statistical organizations, the United Nations, the OECD itself, and the Gallup World Poll. Statistics Canada is a major contributor of data for Canada. The OECD plans to expand the How’s Life? initiative to more countries, improve well-being indicators in domains in which measurement is currently weak, and adapting existing indicators to changing circumstances.

In the most recent edition, How’s Life? 2020, the OECD Statistics and Data Directorate charts whether life is getting better for people in 37 OECD countries and 4 partner countries (OECDiLibrary 2020). This fifth edition presents the latest evidence from an updated set of over 80 indicators, covering current well-being outcomes, inequalities, and resources for future well-being. Since 2010, people’s well-being has improved in many respects, but progress has been slow or deteriorated in others, including how people connect with each other and their government. Large gaps by gender, age and education persist across most well-being outcomes. Generally, OECD countries that do better on average also feature greater equality between population groups and fewer people living in deprivation. Many OECD countries with poorer well-being in 2010 have since experienced the greatest gains. However, advances in current well-being have not always been matched by improvements in the resources that sustain well-being over time, with warning signs emerging across natural, human, economic and social capital. Beyond an overall analysis of well-being trends since 2010, this report explores in detail the 15 dimensions of the OECD Better Life Initiative, including health, subjective well-being, social connections, natural capital, and more, and looks at each country’s performance in dedicated country profiles.

Description for Figure 2

The title of Figure 2 is “The Well-being Framework of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development”

The figure consists of a square divided in two parts horizontally. The title of each part is written in white on a grey background. The title of the upper part is “Current Well-being.” The title of the lower part is “Resources for Future Well-being.”

In the “Current Well-being” part, there are two sections. The section at the left has the following title: “Key dimensions.” The title is written in grey on a white background. It is surrounded by a square grey frame. Under this title, 11 dimensions are listed in two columns (six dimensions in the left column and five in the right column. The dimensions appear together with their respective icons. The icons are circles of different colours that appear at the left of the dimensions. Each of the circles contains an image. The dimensions and their respective images are as follows: “Income and Wealth” (stack of dollars); “Work and Job Quality” (briefcase; “Housing” (house); “Health” (cross); “Knowledge and Skills” (book); “Environment Quality” (fir tree); “Subjective Well-being (heart)”; “Safety” (person running); “Work-life Balance” (scale); “Social Connections” (three persons); and “Civil Engagement” (crossed-out square).

At the right side of the list of dimensions and their respective icons is a grey vertical line bent with a point at the center in the direction of the section at the right.

The section at the right has the following title: “How we measure them.” The title is written in grey on a white background. It is surrounded by a square grey frame. In this section there are four rectangles of the same size. The rectangles are grey. Each rectangle contains an image and has a title under it. The images are white. The titles are black.

The upper-left image is bull’s eye with an arrow pointing to its centre. Its title is “Averages.”

The upper-right image contains three symbols. The symbols for a man and a woman that are superposed and contain the “equal” symbol in their centre. This symbol is located at the upper-left corner. The symbol for a diploma. This symbol is located at the upper-right corner. Three persons of decreasing size: the one at the left is large, the one in the center is medium-sized and the one at the right is small. This symbol is located at the bottom and center of the image. The title of the upper-right image is “Inequalities between groups.”

The lower-left image contains a staircase with one person standing on the bottom stair and another person standing on the top stair. Its title is “Inequalities between top and bottom performers.”

The lower-right image contains a person that is sitting, head hanging down and arms resting on thighs. Its title is “Deprivations.”

In the “Resources for Future Well-being part of the image, there are also two sections. The section at the left is named “Key dimensions.” The title is written in grey on a white background. It is surrounded by a square grey frame. Under this title, four dimensions are listed in two columns (two dimensions in the left column and two in the right column. The dimensions appear together with their respective icons. The icons are black circles. They appear at the left of the dimensions. Each of the circles contains a white image. The dimensions and their respective images are as follows: “Natural Capital” (tree, bird and land); “Economic Capital” (bridge); Human Capital (silhouette of a human head seen sideways with three lights in the brain area); “Social Capital” (handshake).

At the right side of the list of dimensions and their respective icons is a grey vertical line bent with a point at the center in the direction of the section at the right.

The section at the right has the following title: “How we measure them.” The title is written in grey on a white background. It is surrounded by a square grey frame. In this section there are four rectangles of the same size. The rectangles are grey. Each rectangle contains an image and has a title beside it. The images are white. The titles of the images are black.

In the upper-left image there are two piles of coins. The image title is “Stocks.” In the upper right image are six arrows, the three top ones point to the right and the three bottom ones point to the left. The image title is “Flows.”

In the lower-left image is a triangle with a grey-coloured exclamation mark in its centre. The title of the image is “Risk factors.”

In the lower-right image is the representation, of a muscled human arm with elbow bent. The title of the image is “Resilience.”

The source of the image is as follows:

Source: OECD i Library, 2020, How’s Life? 2020: Measuring Well-being.

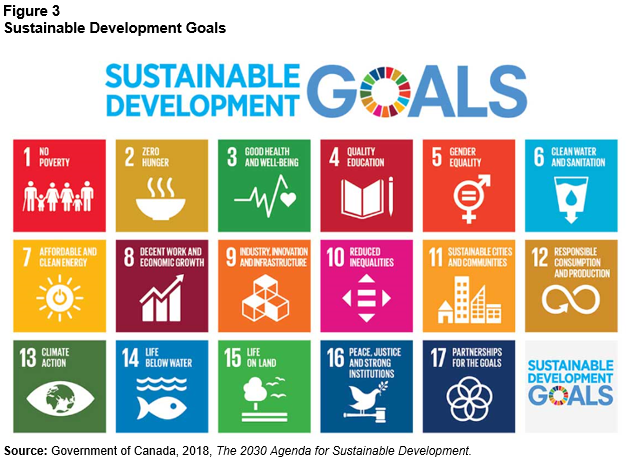

2.1.3 Sustainable Development Goals

The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (UNDESA. Sustainable Development n.d.) represents a shared vision for partnership, peace and prosperity and a commitment to leave no one behind. The Agenda is supported by 17 Social Development Goals (SDGs) (United Nations. Sustainable Development Goals n.d.a), 169 targets (The Global Goals for Sustainable Development 2018) and more than 232 indicators (United Nations. Sustainable Development Goals. n.d.b) (Figure 3). These address the three equally important pillars of sustainable development—the economy, the society and the environment. The SDGs also cover five key elements, also known as the 5 Ps: people, prosperity, planet, peace, and partnership.

The initiative draws on the success of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) (World Health Organization 2018), a series of 8 goals that UN Member States had agreed to try to achieve between the year 2000 and 2015. The MDG targets included halving extreme poverty rates, halting the spread of HIV/AIDS and providing universal primary education (United Nations 2015). In contrast to the SDGs, which target all countries, the MDGs were mainly aimed at developing countries, with the support of developed countries and international organisations.

The SDGs also adopted three important principles:

- Interlinkages: Goals and indicators are interlinked and can have impacts, positive or negative, on each other.

- Leave no one behind: The idea that nobody should be left behind, and that a country will be as successful as the least successful of its people. This element points to the importance of data disaggregation, to ensure the whole spectrum of different realities is represented.

- Reporting: Reporting is central to the achievement of the SDGs. Results and progress should be tracked as often as possible and reported in a neutral and impartial way.

Description for Figure 3

The title of Figure 3 is “Sustainable Development Goals.”

The figure consists of 18 squares of equal size and dimensions. They are arranged in three rows of six squares each. The bottom right square is not numbered. The other squares are numbered from 1 to 17. They are have a different background colour. In each square, except the unnumbered bottom right one, the goal numbers appear at the top left corner, with a goal name to the right of them. Below the goal number and name is the symbol for the goal. The number, goal name and symbol are mostly white.

Centered above the 18 squares is written the title “Sustainable Development Goals” in large print on a white background. The colour of “Sustainable Development” is in a lighter shade of blue than the colour of “Goals,” except for the letter “o” in “Goals”: it is composed of 17 sections of different colours. These colours are the same as the background colours of the squares representing the goals. The word “Goals” is in larger print than the words “Sustainable Development.”

In the unnumbered bottom-right square “Sustainable Development Goals” also appears in the same 17 colours as those of the text centered above the 18 squares, but in a smaller font. It appears in a square of the same dimensions as the 17 other squares. Its background is light grey.

The number, goal name and symbol for each of the 17 goals are as follows, from left to right and top to bottom: 1, No Poverty (6 persons of different gender and ages, the three at the left holding hands); 2, Zero Hunger (bowl of hot food); 3, Good Healh and Well Being (graphical representation of a heart beat with a heart shape at the right end of it); Quality Education (copybook and pencil); 5, Gender Equality (superposed symbols for men and women with an equal symbol in the middle); 6, Clean Water and Sanitation (glass delineated in black, full of water in white colour with a blue water drop in the middle; the bottom of the glass takes the shape of the tip of an arrow); 7, Affordable and Clean Energy (white symbol of a sun with rays, in its centre is the power symbol found on the button of some technological devices; the power symbol is the same colour as the background); 8, Decent Work and Economic Growth (three bars of a bar chart with an arrow going in an upwards direction placed on top of them); 9, Industry Innovation and Infrastructure (four blocks stacked to form a corner; three blocks have one white face, the other faces delineated in white look transparent); 10, Reduced Inequalities (equal sign surrounded with four arrow heads [one on top, one at the bottom, one at the right, and one at the left]; the arrow heads point to the opposite side of the symbol and form the four corners of a square); 11 Sustainable Cities and Communities (faces of four buildings of equal width but of various heights and shapes); 12, Responsible Consumption and Production (curved line in the shape of the number 8 in a horizontal position, one of the ends of the line is in the shape of an arrow head); 13, Climate Action (white oval shape with the representation of the earth in the centre; the continents are green and the water is white; the overall shape resembles an open eye); 14, Life Below Water (two horizontal curved lines representing water and a white fish seen sideways under the curved lines); 15, Life on Land (a tree on the left, three birds in flight on the right, and two straight horizontal lines below them representing the surface of the land); 16, Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions (a white bird seen from the side and carrying a small tree branch with leaves in its beak; the bird is standing on a judge’s hammer); 17, Partnerships for the Goals (five circles delineated in white, partially overlapping on each side; the overlapped portions form the shape of a flower with five petals).

The source for Figure 3 is as follows:

Source: Government of Canada, 2018, The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.

While there are similarities between the UN SDGs and the OECD’s How’s Life? (e.g., multi-dimensionality, similar domains), it has been noted that “the OECD well-being framework is an analytic and diagnostic tool to assess the conditions of a community, whereas the 2030 Agenda is a list of policy commitments agreed by world leaders.” (OECD 2019, p. 4).

In 2015, Canada pledged commitment to the SDGs and work began on the development of a national strategy led by the Department of Employment and Social Development Canada (ESDC), supported by Statistics Canada, on behalf of the Government of Canada. The approach is one of developing a whole-of-Canada national strategy for the 2030 Agenda built on numerous engagements with a range of stakeholders including federal, provincial and municipal governments, Indigenous peoples, the private sector, civil society and Canadians at large. The development of the strategy was informed by a national consultation conducted between March 15, 2019, and May 15, 2019, with a range of stakeholders using multiple platforms and approaches. The results formed the basis of recommendations for Canada’s 2030 Agenda and proposed actions in the areas of leadership, governance and policy coherence; awareness, engagement and partnerships; accountability, transparency and reporting; Reconciliation and the 2030 Agenda and investing in SDGs (Government of Canada 2019a).

In an effort to advance the strategy, recommendations were made to further embed the SDGs in the federal government policy process as part of 30 Actions to 2030 (Government of Canada 2019a, Annex I – 30 actions to 2030). This includes recommendations pertaining to leadership, links to policy, and a new Canadian Indicator Framework.

2.1.4 Mapping well-being frameworks

In order to evaluate the relative relevance of different well-being frameworks to the current Canadian experience, and to ensure that no domains of importance are overlooked when developing a new framework for Canada, it us useful to undertake a comparative mapping of existing frameworks.

While each of the three frameworks considered in this paper has been developed independently to meet different needs and goals, a comparative review of the specific domains and indicators identifies numerous areas of convergence (Table 1). Overall, the three frameworks can be summarized as identifying domains of well-being in four key areas: society, economy, environment and institutions. Within each domain, the frameworks share similar areas of focus such as health, basic living standards, education and community as well as similar indicators (see Appendix A for a more detailed summary). This demonstrates the solid base which can be leveraged to move forward with a quality of life framework in Canada as well as identify potential gaps to meet emerging social, economic and environmental concerns moving forward.

| Key areas | Areas of focus | Canadian Index of Well-being | SDGs, Canadian Indicator Framework | OECD Better Life |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Society | Individuals | Healthy Population | SDG 3 Good health and well-being | Health status |

| Individuals | Living Standards | SDG 1 No Poverty SDG 2 Zero Hunger SDG 8 Decent Work and Economic Growth |

Jobs and Earnings Housing Subjective Well-being (life satisfaction) |

|

| Individuals | Education | SDG 4 Quality Education | Education and Skills Human CapitalTable 1 Note 1 |

|

| Individuals | Time Use | not applicable | Work-life Balance | |

| Individuals | Leisure and Culture | not applicable | not applicable | |

| Equality Across Groups | not applicable | SDG 5 Gender Equality SDG 10 Reduced Inequalities |

not applicable | |

| Communities | Community Vitality | SDG 11 Sustainable Cities and Communities | Social CapitalTable 1 Note 1 Personal Security Social Connections |

|

| Economy | not applicable | not applicable | SDG 9 Industry Innovation and Infrastructure | Economic CapitalTable 1 Note 1 |

| not applicable | Environment | SDG 6 Clean Water and Sanitation SDG 7 Affordable and Clean Energy |

Environmental Quality Natural CapitalTable 1 Note 1 |

|

| Environment | not applicable | not applicable | SDG 12 Sustainable Consumption and Production SDG 13 Climate Action SDG 14 Life Below Water SDG 15 Life on Land |

not applicable |

| Institutions | not applicable | Democratic Engagement | SDG 16 Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions | Civic Engagement and Governance |

|

||||

2.2 Well-being indicator frameworks and the policy process—international experiences

Well-being frameworks are beneficial for use in a public policy setting because they can provide the “potential for prevention rather than crisis-driven policy.” (Wollny, Apps and Henricson 2020). The degree to which well-being indicator frameworks are currently integrated within the policy process, however, can be viewed along a continuum.

At one end are indicator frameworks that have no formal connection with policy processes, but are offered instead as public information. Barrington-Leigh and Escande (2018) note the challenges of visibility and longevity that such initiatives have faced. And while the OECD notes that indicator initiatives provided for public information may shift opinion and inform public and policy debate, it goes on to note that “it is necessary to go beyond simply making indicators available to wide audiences” and look further to their role in policy (Exton and Shinwell 2018, p. 19). Whitby et al. (2014) distinguish between parallel and integrated approaches to policy in the context of ‘Beyond GDP’, arguing that “…it is important to emphasise that ‘balanced’ [policy making] does not just mean the adoption of social and environmental goals in parallel with economic goals (experience tells us that economic objectives tend to trump other ones) but rather a more integrated approach to economic and other policy making” (p. 12).

In 2018, the OECD released a study highlighting the progress made by several countries towards the development and regular reporting of well-being indicators, and identifying the mechanisms used to entrench them in the policy process. The study was based on a review of 15 countries and detailed case studies on their use in policy making in seven. These included Ecuador, France, Italy, New Zealand, Scotland, Sweden, and the United Kingdom (Exton and Shinwell 2018). Among those countries engaged in the development of well-being frameworks and indicators, the following observations were noted:

- Most frameworks were developed in the last decade, with the exception of some countries including the Netherlands whose Life Situation Index which dates back to 1974;

- All the frameworks have adopted a multi-dimensional approach with indicators reflecting a range of economic and material well-being and overall quality of life supported by both objective and subjective measures including measures of subjective well-being (i.e., satisfaction with life);

- Consultation with a broad range of stakeholders were held with varying levels of intensity to inform the development of the measurement framework;

- Government leadership at the national level was key in all cases but varied with some using Centre of Government offices (i.e., Prime Minister’s office Israel, Sweden and Finland; Federal Chancellery in Germany) or ministries responsible for finance and or planning (e.g., Italy, France, Ecuador, New Zealand) with a clear intent of integrating the frameworks in the policy process;

- In the majority of cases, the National Statistical Office (NSO) played a key role as either the lead or co-lead agency for the development of the well-being measurement framework.

The study, now two years old in a rapidly changing world, found that countries varied in the extent to which well-being metrics are incorporated in the policy process. Among countries engaged in well-being indicator measurement, some used well-being metrics in a single stage of the policy process, such as priority/agenda setting (the Netherlands) or policy formulation (New Zealand), while others include well-being metrics in multiple stages of the process (Ecuador, France, Italy, Scotland, Sweden, United Kingdom, and United Arab Emirates).

Exton and Shinwell (2018) also report that governments have used a range of legislative and policy mechanisms to support the use of well-being frameworks. Mandatory reporting of well-being indicators at the outset of budgeting or policy processes is one example (the Netherlands), while legislative requirements for the monitoring and reporting of selected indicators is another (France, Italy, and Ecuador). Lastly, the OECD also notes that government leadership at the national level, with a clear intent of integrating well-being frameworks in the policy process, was a key element in well-being framework initiatives implemented over the past decade.

In an earlier review based on case studies in seven countries, Whitby et al. (2014) highlight a range of challenges facing the integration of well-being frameworks within the policy process, grouping these into three categories:

- Political barriers: The effectiveness of alternative well-being frameworks in the policy process may be limited if well-being indicators are not publicly accepted or endorsed as desired outcomes, resulting in a lack of democratic legitimacy. Exton and Shinwell (2018) note that countries implementing well-being frameworks over the past decade engaged in public consultation “…with varying levels of intensity, scale and goals.” (p. 9). Public consultation was also a critical element in the development of the CIW. Whitby et al. (2018) also identify “lack of [a] strong narrative that engages the public” and “lack of a clear political imperative” as two other potential political barriers to the use of alternative well-being frameworks in the policy process.

- Indicator barriers: Conceptual and methodological challenges regarding the measurement of well-being may pose a challenge to well-being frameworks. The frequency of data collection and timeliness of indicators are two challenges. Data collected on a five-year cycle or indicators that are two or three years out of data are likely to be inadequate for policy decision-making. The construction of composite indices, and the weights that are applied to each of the constituent elements, is another persistent challenge.

- Process and structural barriers: Integrating alternative well-being frameworks into the policy process may pose, what Whitby et al. call ‘process’ challenges. Alternative well-being frameworks are, by design, multi-dimensional and their use in policy processes requires an approach that cuts across government departments, policy areas, and disciplinary boundaries. The multi-dimensionality of alternative well-being frameworks also necessitates the use of a range of methodological approaches and analytical techniques. Whitby et al. (2014) report:

We found persistent perceptions among mainstream policy actors that if alternative indicators are to succeed their methodologies must be consistent with the current economic model and be directly linkable to existing economic instruments and tools (e.g., cost-benefit analysis, resource efficiency)” (p. 15)

In an effort to promote the sharing of experiences and expertise among officials working to embed wellbeing outcomes in economic policy, the governments of Scotland, Iceland and New Zealand formally launched the Wellbeing Economy Governments (WEG) initiative in 2018. WEG Members attended the October 2019 OECD Workshop, Putting Well-being Metrics into Policy Action (OECD 2019), aimed at exploring the policy uptake of well-being, inclusiveness and sustainability indicators, focussing on the types of evidence and analysis that policy makers need, and how practical policy mechanisms could be adapted to apply this evidence on a more systematic basis.

2.3 Well-being indicator frameworks and the policy process—Canadian experiences

While Canada currently does not have a well-being framework integrated in the policy process at the federal level, it is important to draw attention to the range of existing initiatives to integrate aspects of well-being in selected policy areas. There are several national level frameworks developed to support federal policies related to the well-being of specific populations (see appendices B and C). A few of these include the Community Well-being Index for Indigenous peoples (Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada and Indigenous Services Canada and other Agencies), the Canadian Index for Measuring Integration (2020) which examines four dimensions of immigrant integration to assess the gaps between immigrants and the Canadian-born population (The Canadian Institute for Identities and Migration, the Association of Canadian Studies and Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada), the Gender Results Framework (Women and Gender Equality), and the Veterans’ Well-being Act (Veterans Affairs Canada and Department of National Defence and Canadian Forces). With the support of Employment and Social Development Canada and Social Development Partnerships funding, the Vanier Institute of the Family has been developing a Family Well-being Index and associated indicators in consultation with project advisors (Vanier Institute of the Family 2020a). These frameworks vary in their dimensions and indicators as they are designed to highlight issues and metrics of particular relevance to specific populations.

There are also numerous federal policies that touch on specific dimensions of well-being. For example, the Public Health Agency of Canada, in collaboration with national and provincial organizations including Statistics Canada, released indicators on health inequalities across socio-economic groups as part of the Health Inequalities Reporting Initiative. The intersectionality of well-being in the domains across health, income and employment is highlighted. Similarly, Canadian Heritage is leading Canada’s anti-racism strategy—Building a Foundation for Change: Canada’s Anti-Racism Strategy 2019–2022. The objective is to find ways to counter racism in its various forms, with a strong focus on community-based projects. The strategy is guided by a vision of Canada where all Canadians benefit from equitable access to and participation in the economic, cultural, social and political spheres. Brief summaries of selected well-being frameworks and polices in Canada are provided in Appendix B.

Nonetheless, the large number of indicator initiatives fielded by federal, provincial and regional governments, non-governmental organizations, academics, and private sector institutions testifies to the ‘sea of indicators’ characterizing the current environment. This diversity and ‘over-abundance’ of indicators may itself pose challenges, such as competition between the producers of indicator frameworks and confusion among potential users (Whitby et al. 2014).

The incorporation of well-being measurement into the policy process has implications for Canada’s statistical system. Statistics Canada data are used extensively in indicator initiatives, both nationally and internationally. It is important for the agency to continue to be responsive to the evolving needs of indicator users.Note

3 The subjective well-being approach

While most well-being frameworks include subjective measures, the subjective well-being approach advocates for use of quality of life as the primary measure of well-being. In a recent report, Helliwell (2018) argues for the use of a subjective measure such as life satisfaction as they provide an “umbrella measure” of quality of life.

In the subjective well-being (SWB) approach, “fundamental importance is attached to the evaluations that people make of their own lives.” Proponents of the approach view “…the appeal and usefulness of subjective measures of well-being data, and especially life evaluations, as being due to their primary nature—as unvarnished measures of what people actually think about the quality of their lives” (Helliwell 2018, p. 966).

In its 2013 OECD Guidelines on Measuring Subjective Well-being (OECD 2013), the OECD defines SWB as:

Good mental states, including all of the various evaluations, positive and negative, that people make of their lives and the affective reactions of people to their experiences (p. 10).

This definition covers different aspects of well-being, which the OECD further delineates into three elements:

- Life evaluations—the reflective assessments that people make of their life, or some aspect of it

- Affect—a person’s feelings or emotional state, usually at a particular time (e.g., sadness, worry or happiness yesterday)

- Eudaimonia—an individual’s sense of purpose or meaning in life, and psychological functioning.

The OECD recommends that a question pertaining to life satisfaction serve as the primary measure of SWB, when a single measure is required. This question asks:

The following question asks how

satisfied you feel, on a scale from 0 to 10. Zero means you feel “not at all

satisfied” and 10 means to feel “completely satisfied”.

Overall, how satisfied are you with

life as a whole these days?”

Life satisfaction provides an ‘umbrella measure’ that allows the factors contributing to, or detracting from, well-being to be identified. These measures can thus be used to compare well-being across communities and populations (including measuring inequalities, support research to better understand what drives quality of life), and to inform policy priority setting and decision-making. This approach avoids several challenges facing well-being indicator frameworks including the inherent difficulty of creating a single index from multiple indicators and the choices that must be made regarding which indicators to include, and how to weight reflect their relative importance. If a single composite measure is not created, how to comprehensively understand well-being across multiple indicators and domains is a challenge. Instead, indicators should be used to better understand what drives differences and changes over time in an overall umbrella measure of well-being such as life satisfaction.

3.1 World happiness reports

In 2011, the United Nations General Assembly adopted a resolution calling on member states “to undertake steps that give more importance to happiness and well-being in determining how to achieve and measure social and economic development.” (cited in Helliwell 2019a). The following year, the first edition of the World Happiness Report was released (Global Council for Happiness and Wellbeing 2019). Based on a review of international data and evidence related to the science of happiness, the report demonstrated that the quality of people’s lives can be coherently, reliably and validly assessed by a collection of subjective measures of well-being collectively referred to as “happiness.”

Subsequent annual World Happiness Reports present new evidence on the factors that support well-being, in-depth country assessments, and happiness scores across countries, drawing primarily on data provided by the Gallup World Poll. For example, the 2017 World Happiness Report showed that three-quarters of the variation in average life evaluations observed across more than 150 countries are explained by six variables: gross domestic product (GDP) per capita, healthy life expectancy, having someone to count on in times of trouble, sense of freedom to make key life decisions, trust, and generosity (Helliwell, Huang and Wang 2017). The 2019 World Happiness Report compared average life evaluations in 132 countries over the period from 2005–2008 to 2016–2018 concluding that the greatest losses in life evaluation occurred in Venezuela and Syria (Global Council for Happiness and Wellbeing 2019).

3.2 Integrating subjective well-being into policy

As with well-being indicator frameworks, the integration of Subjective Well-Being (SWB) measures within policy processes is still in its early days. Nonetheless, many applications of SWB tools and metrics can be found in different policy areas. The Global Happiness and Well-being Policy Report 2019, published by the Global Council for Happiness and Wellbeing (2019), highlights innovative practices, evidence and policy recommendations to promote happiness and well-being in six areas: education, workplace, personal happiness, public health, city design, and metrics.

New projects to incorporate happiness in the policy processes are underway in Canada. Statistics Canada has been asked by Canadian Heritage (PCH) and the Canada Council for the Arts to develop an app to address a critical data gap in SWB measures. For these partners, there is a need to empirically demonstrate outcomes related to investments in arts, culture and heritage activities. In response, Statistics Canada is piloting a first use of an app for smartphones that will test the Experience Sampling Method (ESM), which will collect data on SWB measured in the moment against the activity of the respondent at the moment—a method endorsed by the OECD as the most appropriate method for collecting in the moment subjective measures of well-being (OECD 2013). The ESM app will enable reporting of cause-and-effect results at the outcomes level on program and policy areas (Fujiwara and MacKerron 2015).

Another application in the policy domain is life satisfaction analysis designed to convert the difference in life satisfaction associated with an observed characteristic—say, percentage of green space in a neighbourhood—into the estimated change in income that would be required to yield the same increase in well-being (Ambrey and Fleming 2014). This approach was used by PCH to estimate the value of the wellbeing impacts of arts, culture and sports participation in Canada (Lemyre, Mader, and Ambard 2018). This approach is also currently being assessed by federal researchers with the Privy Council Office and Public Health Agency of Canada in a study titled A life satisfaction approach to valuing the impacts of healthy behaviours on subjective-well-being (Joyce 2019). They report that physical activity and smoke-free living are associated with increases in life satisfaction that are equivalent to increases in weekly household income of $631 and $563 respectively. The research community is also engaged in the development of SWB-based tools, including the monetization of life satisfaction for inclusion in the policy process. For example, a special session on Government Budgeting for Happiness is scheduled for the 2020 annual conference of the Society for Quality-of-Life Studies.

3.3 Implications for data collection and measurement

Subjective measures of well-being have been the subject of much methodological assessment. The validity of SWB measures has been confirmed in various studies using alternative approaches and lines of evidence (see reviews in Frijters et al. [2019] and Helliwell and Wang [2012]). Likewise, the relationships between the different elements of SWB—life evaluations, positive and negative affect, and eudaimonia—have been scrutinized, as have various survey design and measurement issues. This is evident in the 265 pages of the OECD’s Guidelines on Measuring Subjective Well-being (OECD 2013), and in a large research literature. Statistics Canada too has assessed life satisfaction responses, analysing issues such as item non-response, survey day and survey month effects, survey framing effects, and survey mode effects (Bonikowska et al. 2014; Arim and Schellenberg 2019).

Statistics Canada has collected a large volume of information using the life satisfaction question. The question is easy to administer, taking less than 20 seconds to answer, and yields a low rate of item non-response (again, supporting the view that the respondents understand and are able to answer the question). The life satisfaction question has been included on the General Social Survey (GSS) in most years since 2003, on the Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS) since 2009, on the Longitudinal and International Survey of Adults (LISA) since 2014, and on the Canadian Housing Survey (CHS) since 2018. Altogether, between 2009 and 2018 Statistics Canada collected information on the life satisfaction of approximately 800,000 survey respondents. Large samples across household surveys create opportunity for ‘pooling’ data across sources and survey years, thereby increasing the scope for research on specific populations or detailed geographies. Linkages between these large pooled samples and administrative data sources create further opportunity for research. This large repository of life satisfaction data is situated within a broad and rich set of both individual- and neighbourhood-level covariates, providing scope to further expand the evidence related to SWB. The ability to combine and interpret life satisfaction data from a range of surveys is dependent in part on comparability and understanding the impacts of questions asked in the context of different surveys.

4 Economic frameworks—the System of National Accounts

In addition to the well-being indicator framework and SWB approaches discussed above, adaptations and innovations in other measurement systems are underway. The objective of this section is to highlight work on the System of National Accounts (SNA). It is widely recognized that gross domestic product (GDP) is a measure of economic activity, not a metric of economic well-being or sustainability. Yet many believe there should be a much closer relationship between macroeconomic accounting frameworks, governed by the international SNA, and well-being and sustainability.

An update to the SNA2008, the current standard for national accounting, is underway, and the need to incorporate well-being and sustainability measures is one of three key streams on the research agenda. With a leadership role for this research stream, Statistics Canada is well positioned to influence the effort, which involves input from a wide variety of international experts in a range of research spheres.

A long-term vision for expanding the traditional SNA framework to encompass elements of well-being and sustainability might involve a fully elaborated, integrated information system that drills down to micro data sets, and integrates information from a broad range of multidisciplinary spheres. Recognizing that this vision is not practically viable as a generalized international standard in the short term, a more pragmatic approach is being taken for the next update, drawing on key areas where significant measurement frameworks have been developed in the form of specialized “satellite accounts,” closely connected with the dimensions of well-being and sustainability.

Five areas are currently in scope for elaboration, each drawing on a team of designated experts for its development. In general, these are areas where well-established information frameworks and international guidance already exist. They are briefly described below:

- Unpaid household work: Recognizing non-market activities undertaken in the home (often by women) and trade-offs with work in the labour market, caregiving and volunteering. Relationships with time use and developments in the digital economy.

- Environmental–economic accounting: Building in dimensions of the System of Integrated Environmental and Economic Accounts (SEEA) for a more fully elaborated SNA framework explicitly accounting for natural resources, ecosystem services and other environmental impacts.

- Distributions for the household sector: Regularly reporting on distributions of national accounts household income consumption, saving and wealth by quantile or socio-demographic characteristics.

- Education and human capital: Recognizing education and human capital as an investment that creates and ongoing return. More explicitly accounting for labour characteristics in macroeconomic outputs and productivity measures.

- Health and social conditions: Appropriate measurement of non-market outputs in the health care sector and capacity to link outputs to health outcomes.

4.1 Updating the System of National Accounts

While the challenges are considerable and will differ by domain, the intent is to build elaborations or extensions to the SNA rather than radically redefine existing macro measures, such as the GDP, which adequately serve their intended purpose. Neither is the intent to replace the GDP with another single headline indicator. The new, broader, information framework would not be restricted to monetary measures and would aim to enable analysis of interactions of these new dimensions with traditional monetary indicators, as well as linkages among the added dimensions. The expanded system would also relate, at a broad level, to established well-being frameworks, such as the OECD Better Life Index or the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

The development of new international standards to better integrate established measures of economic growth (i.e., GDP) with measures of well-being and environmental sustainability will involve an elaborate range of stakeholders and take considerable time to establish and implement. There may, however, be a number of short-term opportunities to take further steps in this direction, to better showcase work that has already been done, and to build awareness opportunities for collaborative work. Some specific ideas, outlined below, could be a starting point for further development:

- Establish a regular quarterly release for the household sector drawing on information already produced, including context from the Distributions of Household Economic Accounts program.

- Update estimates of households’ unpaid work with recent time use information, with a focus on developments in the digital economy (e.g., offering services on line, participation in platform/“gig” economy).

- Further develop and implement output-based measures for dimensions of the health care sector.

- Build socio-economic characteristics of employment and hours worked into the labour productivity database, facilitating analysis aligned with national accounts indicators and the bridging of social and economic measures in labour accounts.

- Highlighting work on economic–environmental linkages.

5 Current social, economic and environmental trends—implications for well-being measurement

Regardless of how it is measured, the well-being of Canadians continues to be impacted by a broad range of economic, social and environmental developments. Proponents of both the well-being indicator framework approach and the SWB approach have both drawn attention to common themes and issues which represent potential gaps in current measurement frameworks. Six of these are highlighted and described below including implications for the measurement of new and/or timely measures of well-being. In all cases, the following proposals to advance the measurements of well-being will be conducted in accordance with best practices for the development of indicators and would leverage the range of data collection options available at Statistics Canada. More information regarding criteria for quality indicators and data collection options are available in appendices D and E respectively.

5.1 Digitalization

It is now widely recognized that the digital transformation—the social and economic changes associated with Information and Communication Technologies (ICT), automation, artificial intelligence, and other digital technologies—continues to reshape the lives of individuals, communities, and societies. The breadth of the digital transformation is immense, affecting virtually all aspects of peoples’ lives. The impacts of the digital transformation are also varied, ranging from minor adaptations in daily life to potentially transformative changes in fundamental values and processes. And individuals, while often leading ‘tech-saturated’ lives already, continue to face rapid and ongoing technological change.

There are divergent views regarding the opportunities and risks that the digital transformation poses to well-being. For example, a 2018 Pew Research Center study involving over 1,100 technology experts, health specialists, and other key informants found that 47% expect well-being “...to be more helped than harmed by digital life in the next decade,” 32% expect well-being to be more harmed than helped, while the remaining 21% did not expect much change in well-being (Anderson and Rainie 2018). More broadly, questions regarding the impacts of technological change are being raised across many quarters. For example, a recent expert panel identified five aspects of well-being that appear susceptible to the impacts of technology but have received little or no attention in well-being frameworks. These include: human development (including early childhood learning), mental health across the life span, social inclusion, personal and public security, and governance (Gluckman and Allen 2018). This highlights how much is still unknown and how wide ranging the data needs are in this field.

The potential impacts of technological change on well-being have been underscored by well-being researchers. For example, Land and Michalos (2018) highlight the scope and potential impacts of automation and social media, and underscore the importance of updating well-being indicator frameworks to reflect these challenges. Similarly, the impacts of new technologies on well-being are the focus of several chapters of the 2019 World Happiness Report.

Implications for well-being measurement

To better understand the implications of digitization for the measurement of well-being, Statistics Canada is leading an in-depth review of data collect practices in the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE) member countries for the Conference of European Statisticians (CES). The review will be published by the CES in 2020. Several of the following initiatives could subsequently be undertaken by Statistics Canada:

- Engaging with the international community: Statistics Canada is prepared to lead an international working group on ‘Measuring Well-Being in the Era of the Digital Society’ for the CES. Building on the in-depth review, the broad objective would be to further advance data collection and measurement practices in this area, with specific priorities established at the CES Plenary meetings held semi-annually.

- Using existing data to inform new well-being indicators: Information on technology use is currently available on Statistics Canada surveys, such as the 2016 GSS (Canadians at Work and Home), the 2014 and 2019 GSS (Victimization) (Statistics Canada 2019a), the 2018 Canadian Internet Use Survey (CIUS), and the LISA. A program of research that exploits this information will be undertaken on issues such as the perceived impacts of social media use; on-line victimization; digital skills; and technology use among population groups (e.g., seniors). This research will help inform the identification of relevant indicators moving forward, including the intensity and frequency use of digital devices and their impact on adults and children, as well as by other intersecting identities. Further work and data collection are needed to understand the link with mental health.

- Embedding well-being in existing surveys: The CIUS will be fielded in 2020 and 2022, offering opportunity to update survey content in response to emerging issues and priorities. Questions on well-being are among the refinements being made to the 2020 survey. Further refinements to the 2022 survey will be informed by consultation and analysis.

- Using a new survey approach to address gaps: In 2020, Statistics Canada started piloting its Web Panel Survey—an online data collection platform that will field approximately 10 minutes of questionnaire content to representative samples of Canadians on a monthly basis. An experimental module of questions on Canadians’ perceptions and experiences of disinformation developed for the Internet and is scheduled to be fielded in the fall of 2020. Information on other aspects of digitalization and well-being could be collected using this vehicle.

- Using new technologies to advance well-being measurement: As part of a new application that will collect real time information from Canadians using smart technologies, Statistics Canada intends to field the Well-being Check. This app will measure in-the-moment well-being indicators (e.g., happiness, anxiety) as well as contextual information (e.g., what you are doing, who you are with). This initiative, which uses Experience Sampling Method, is set to be piloted in the summer of 2020. This approach could be used to collect well-being measures moving forward.

- Measuring the impact of free services: Estimate the impact of free services such as social networks, cloud storage, point-to-point video service (e.g., Skype) on the well-being of users.

- Evaluate individuals’ satisfaction and happiness in light of these changes.

It is not enough to know how the “average” Canadian is doing. It is also important to identify who is being left behind, who may be more resilient and who may experience the greatest degree of opportunity flourishing, so that appropriate policy responses can be designed to support different populations in Canada. Therefore, the development of new indicators must provide an understanding of how the benefits and costs of digital transformation are being realized by different demographic groups such as women, youth, persons with a disability, persons at risk of poverty, Indigenous Peoples, recent immigrants, minority groups and seniors.

5.2 Job quality in a changing new world of work

Changes in Canadian workplaces are relevant to the discussion of well-being. Indeed, given the fact that most working-age individuals spend a significant fraction of their lives working creates a strong link between quality of life and job satisfaction. Today’s jobs differ drastically from those in the past. The remarkable changes in industrial structure, along with technological advancements, changes in the intensity of firm competition and international trade over the past four decades have resulted in changes in several job characteristics. Overall today’s jobs are less likely to be full-time, permanent, unionized or covered by a registered pension plan than they were in the early 1980s.

Job characteristics have changed in different ways for different groups of workers. For example, wages in full-time jobs have grown faster for older workers than for younger ones. Jobs in education, health care and social assistance have become relatively more important for women but not for men. The manufacturing decline observed since the early 2000s reduced wages and full-year, full-time employment rates of men, especially less-educated men living in the affected areas, but had little impact on women (Morissette 2018).

Not all workers are equally represented in high-quality jobs. An assessment of job quality in Canada (Chen and Mehdi 2018) finds diverse patterns of job quality across sectors and socio-demographics groups. In particular, workers with a high school diploma or less education are more likely than other workers to be in jobs involving less flexible work schedules, low autonomy, lack of training opportunities and employment benefits. While young workers are more likely than older workers to hold jobs with involuntary and irregular work schedules, they do relatively well in terms of manageable workload and access to informal training.

As a result of automation driven by the introduction of computer-based technologies, some occupations saw their share of total employment drop significantly (Frenette and Frank 2020). For example, only 7% of women aged 17 to 64 were employed in office support occupations in 2019, down from 13% in 1989. Several groups of workers are more likely to face a high risk, including older workers (55 or above), workers with no postsecondary credentials or with postsecondary credentials in certain fields, individuals with low literacy or numeracy proficiency, low earners, part-time workers, employees in small firms, and manufacturing workers.

Along with the changes documented above, gig employment is another changing dimension of work. Contrary to employees, gig workers are usually not in an employer–employee relationship. This includes highly skilled freelancers as well as on-demand workers hired for jobs through the growing number of online platforms. Statistics Canada has pioneered a clearly defined methodological framework for identifying gig workers in Canada based on various Canadian administrative sources (Jeon, Liu and Ostrovsky 2019). The study shows that the percentage of workers involved in gig work increased from 5.5% in 2005 to 8.2% in 2016. More than half of gig workers combine gig work with wages and salaries from another job, and the annual income of a typical gig worker was usually low. Gig work was more prevalent among workers in occupations in arts, entertainment and recreation, and among immigrants.

The changing nature of work and impact on well-being are also influenced by the decisions of firms. These include decisions that directly impact workers, such as levels of remuneration, the nature of the employment contract, the availability of pensions and health plans, work-life balance initiatives, and employee and family support programs. The impacts of automation and technologies in the workplace on task content, skill requirements and job security are also centre stage in research and public discussion. Business decisions also affect consumers and the public at large, such as charitable and philanthropic initiatives, the creation of safe and healthy products, and the fostering of a secure and healthy environment both in the workplace and in the community at large.

Based on their meta-analysis of 339 studies undertaken by Gallup, Krekel, Ward and de Neuve (2019) report a positive correlation between employee well-being and several firm-level measures of performance, including productivity, customer satisfaction, staff turnover, and stock price. They go on to highlight workplace interventions pertaining to social relationships (e.g., employee supervision), task content and work-life balance.

Implications for well-being measurement

These new forms of employment interrelate with multiple facets of economic well-being of Canadians, such as work conditions and benefits, access to employment insurance, family-work balance and older workers’ transition to retirement and retirement income. To continue to build the data and evidence base to understand the changing nature of work and impact on well-being, the following activities could be undertaken to advance well-being measurement in this area:

- Measuring the gig-economy: While some research already confirms that workers in non-standard employment arrangements cumulate many disadvantages in the workplace other than being low-paid, it remains unclear how gig employment exactly intersects with precarity and overall socio-economic well-being. Statistics Canada is looking at potential survey–administrative integrated data sources that could shed light on multidimensional quality indicators of non-standard employment.

- Understanding quality of work by sector: Impacts of all these changes diverge at the regional and sectoral levels. Certain sectors and regions are facing significant labour and skill shortages while some others have much higher unemployment rates. This labour market imbalance was voiced by many industrial stakeholders and urges more nuanced analysis. Moreover, with some resource-based industries transitioning to a low-carbon economy, the way in which workers transition at local labour markets and across industries, as well as needs for necessary reskilling and upskilling are emerging questions that require further integrated data and analytical evidence linking the labour demand and supply information at a more granular level. Statistics Canada has started to consider the possibilities of linking demand data such as Job Vacancy and Wage Survey of employers with supply data such as Labour Force Survey to gauge the unmet needs and address this information gap.