Research to Insights: A look at Canada’s economy and society three years after the start of the COVID-19 pandemic

Skip to text

Text begins

About Research to Insights

The Research to Insights series of presentations features a broad range of findings on selected research topics. Each presentation draws from and integrates evidence from various studies that use innovative and high-quality data and methods to better understand relevant and complex policy issues.

Based on applied research of valuable data, the series is intended to provide decision makers, and Canadians more broadly, a comprehensive and horizontal view of the current economic, social and health issues we face in a changing world.

Three years on…

March 11, 2023, marks three years since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. COVID-19 is still evolving and circulating widely across Canada and many other countries. The Government of Canada (GC) acknowledges that the virus remains a public health emergency of international concern and continues to focus on protecting the health and safety of all Canadians (GC, 2023). To date, 97 million vaccination doses have been administered, but the over 51,000 Canadians who have died from COVID-19 remind us of the true cost of the pandemic (GC, 2023).

The Omicron wave marked a turning point for the pandemic in Canada. Most COVID-19 restrictions were eased or lifted in early 2022, and people began to live with the virus. Today, national transmission indicators and outbreak incidence remain stable, though many of the social impacts of the pandemic, particularly those related to mental health challenges and substance abuse among younger Canadians, may be slow to ease.

Life in Canada, as in other countries, has changed in many ways since the start of the pandemic—some changes were direct impacts of the pandemic, while others were trends that were accelerated by it. Over the past year, Canadian households and businesses have faced a range of challenges. This presentation is the last in a series that has documented the impacts of the pandemic on the lives of Canadians (COVID-19 in Canada: A One-year Update on Social and Economic Impacts and COVID-19 in Canada: A Two-year Update on Social and Economic Impacts). In this edition, we highlight several of the major economic and social trends that continue to impact the lives of Canadians. It includes an overview of recent economic and labour market developments, financial pressures related to inflation and affordability, and trends related to excess mortality and well-being.

For more information: Update on the COVID-19 situation in Canada – January 27, 2023 and COVID-19 epidemiology update: Key updates.

Economic conditions: Economic activity remains resilient as households and businesses adjust to higher borrowing costs

- Canada’s gross domestic product (GDP) growth has outpaced that of other G7 countries since the second quarter of 2021.

- Output rose steadily throughout most of 2022, albeit at a slower pace late in the year. As of December, real GDP was 2.7% above pre-pandemic levels.

- Higher financing costs have weighed on activity in sectors that are sensitive to interest rate changes. Activity at real estate agents and brokers contracted for the tenth consecutive month in December 2022. Residential construction has also pulled back as borrowing costs have risen.

- According to the Bank of Canada, it typically takes 18 months to two years for changes in the policy interest rate to work their way through the economy.

Data table for chart 1

| Gross Domestic Product (LHS) | Bank rate (RHS) | |

|---|---|---|

| month-over-month percentage growth | percent | |

| 2021 | ||

| June | 0.8 | 0.5 |

| July | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| August | 0.6 | 0.5 |

| September | 0.3 | 0.5 |

| October | 0.8 | 0.5 |

| November | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| December | 0.1 | 0.5 |

| 2022 | ||

| January | -0.2 | 0.5 |

| February | 0.7 | 0.5 |

| March | 0.7 | 0.8 |

| April | 0.1 | 1.3 |

| May | 0.2 | 1.3 |

| June | 0.3 | 1.8 |

| July | 0.2 | 2.8 |

| August | 0.2 | 2.8 |

| September | 0.2 | 3.5 |

| October | 0.1 | 3.5 |

| November | 0.1 | 4.0 |

| December | -0.1 | 4.5 |

| 2023 | ||

| January | Note ...: not applicable | 4.5 |

|

... not applicable Notes: RHS refers to right hand scale and LHS referes to left hand scale. Sources: Statistics Canada, table 36-10-0434-01 and Bank of Canada. |

||

For more information: Understanding how monetary policy works.

Economic conditions: Business entry slows as challenges and uncertainty persist

- The number of active businesses fully recovered to pre-pandemic levels in late 2021.

- Business closures have outpaced business openings since the summer of 2022 as borrowing costs have increased. Closures have remained relatively stable since the summer months, while openings in November 2022 fell to their lowest level in over two years.

- Excluding the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, November 2022 was the first month on record that the number of active businesses did not post positive growth for five consecutive months, as rising inflation, high input costs and labour-related obstacles continue to impact the outlook.

- Businesses in retail trade and tourism experienced declines in the number of active businesses in recent months.

- Business insolvencies rose sharply in 2022 as supply chain challenges, inflationary pressures and labour-related obstacles affected many businesses.

Data table for chart 2

| Active businesses (LHS) | Net business openings (RHS) | |

|---|---|---|

| number of businesses | number of net business openings | |

| 2020 | ||

| January | 905,700 | 1,056 |

| February | 907,917 | -1,522 |

| March | 873,143 | -22,313 |

| April | 816,869 | -75,035 |

| May | 791,352 | -28,780 |

| June | 800,294 | 1,334 |

| July | 821,070 | 24,792 |

| August | 835,072 | 21,853 |

| September | 852,067 | 17,357 |

| October | 861,301 | 14,697 |

| November | 863,789 | 6,764 |

| December | 878,019 | 11,797 |

| 2021 | ||

| January | 883,896 | 7,153 |

| February | 887,985 | 4,042 |

| March | 893,274 | 5,228 |

| April | 894,192 | -1,023 |

| May | 892,756 | 875 |

| June | 894,678 | 146 |

| July | 901,784 | 7,392 |

| August | 903,051 | 1,263 |

| September | 904,364 | 347 |

| October | 907,178 | 3,452 |

| November | 912,341 | 4,768 |

| December | 913,622 | 1,399 |

| 2022 | ||

| January | 921,375 | 6,806 |

| February | 921,081 | -271 |

| March | 922,070 | 1,208 |

| April | 926,306 | 3,567 |

| May | 927,393 | 1,195 |

| June | 928,524 | 1,185 |

| July | 927,691 | -1,082 |

| August | 927,775 | -1,017 |

| September | 927,080 | -583 |

| October | 925,164 | -2,719 |

| November | 921,116 | -6,003 |

|

Notes: RHS refers to right hand scale and LHS referes to left hand scale. Source: Statistics Canada, table 33-10-0270-01. |

||

For more information: The Daily — Canadian Survey on Business Conditions, fourth quarter 2022 (statcan.gc.ca).

Labour market conditions: Strong employment growth as elevated vacancies begin to ease

- Employment has strengthened in recent months, with the number of private sector employees increasing by over one-quarter of a million from September 2022 to January 2023. Employment rates among core-age women and men remained at or near record levels.

- Total employment in January 2023 was about 800,000 above its pre-COVID-19 baseline. All the net gains since the onset of the pandemic have been in full-time work.

- Employment growth in the private sector has been driven largely by gains in professional, scientific and technical services, while public administration and health care jobs have bolstered employment in the public sector.

Tight labour market conditions persist as vacancies begin to moderate

- Job vacancies eased in late 2022 but remain elevated. On a monthly basis, vacancies totaled about 850,000 in December, down from a peak of just over 1 million in May 2022.

- Vacancies in health care and social assistance have trended higher, reaching about 150,000 in December 2020. Almost half of all health care vacancies in the third quarter, have remained unfilled for 90 days or more, suggesting greater difficulties filling positions.

Data table for chart 3

| Public | Private | Self Employed | |

|---|---|---|---|

| thousands of persons | |||

| Accommodation and food services | Note ...: not applicable | -115.4 | 4.9 |

| Transportation and warehousing | 32.3 | -54.5 | -42.8 |

| Health care and social assistance | 146.0 | -17.1 | -9.9 |

| Public administration | 167.6 | 1.7 | Note ...: not applicable |

| Educational services | 87.8 | 22.3 | 19.4 |

| Wholesale and retail trade | 1.9 | 47.0 | -32.4 |

| Information, culture and recreation | -1.4 | 64.2 | -1.5 |

| Manufacturing | -0.9 | 64.9 | -6.5 |

| Construction | 0.1 | 132.8 | -28.8 |

| Finance, insurance, real estate, rental and leasing | 9.5 | 164.4 | -27.0 |

| Professional, scientific and technical services | 3.6 | 253.7 | 32.4 |

|

... not applicable Source: Statistics Canada, table 14-10-0026-01. |

|||

Demographic trends: Strategies to mitigate population aging are essential for labour force growth

- One in five working-age Canadians is set to retire in the coming years. The gap between those about to leave the labour market (55- to 64-year-olds) and those entering the labour market (15- to 24-year-olds) is at record levels.

- Population aging is now shaping labour market trends, despite the fact that workers are working just as much now as they reach key age milestones. If the age distribution of the working age population had remained constant over the past three years, there would currently be over 330,000 more people in the labour force.

- Population aging will put more pressure on productivity growth to fuel increases in living standards. Business investment spending is a key contributor to productivity growth.

- After rising sharply in the early stages of the pandemic, labour productivity declined for seven consecutive quarters, before increasing in the second and third quarters of 2022. Business productivity has just rebounded to pre-COVID-19 levels, while unit labour costs are 13% above their pre-COVID-19 baseline.

Data table for chart 4

| 1966 | 1971 | 1976 | 1981 | 1986 | 1991 | 1996 | 2001 | 2006 | 2011 | 2016 | 2021 | 2026 | 2031 | 2036 | 2041 | 2046 | 2051 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| number | ||||||||||||||||||

| Historic: 15 to 24 years | 3,299,000 | 4,003,700 | 4,479,100 | 4,658,700 | 4,178,200 | 3,830,500 | 3,857,200 | 4,009,100 | 4,220,900 | 4,365,600 | 4,268,900 | 4,215,200 | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable |

| Projected: 15 to 24 years | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | 4,215,200 | 4,607,000 | 4,885,600 | 5,000,200 | 5,102,400 | 5,212,800 | 5,341,300 |

| Historic: 55 to 64 years | 1,479,700 | 1,731,700 | 1,924,400 | 2,159,200 | 2,328,300 | 2,399,600 | 2,489,500 | 2,868,000 | 3,674,500 | 4,393,300 | 4,910,800 | 5,218,900 | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable |

| Projected: 55 to 64 years | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | Note ...: not applicable | 5,218,900 | 5,021,900 | 4,722,000 | 4,866,500 | 5,263,000 | 5,641,800 | 5,879,600 |

|

... not applicable Notes: Gray areas indicate baby boomers turning 15 years old between 1966 and 1980 and turning 55 years old between 2001 and 2020. Double arrow shows a record gap in 2021 between the population aged 15 to 24 years and the population aged 55 to 64 years. Data for 2026 to 2051 are population projections from the M1 medium-growth scenario and are based on the 2016 Census. For reasons of comparability, the census net undercoverage has been removed from the projected populations presented in this chart. Sources: Census of Population, 1966 to 2021 (3901). The custom population projections are based on the Population Projections for Canada, Provinces and Territories, 2018 to 2068 (91-520-X). |

||||||||||||||||||

For more information: People nearing retirement outnumber people old enough to enter the labour market (statcan.gc.ca).

Demographic trends: Immigration will only partially alleviate the impacts of population aging

- Since early 2020, over 1.2 million permanent and temporary immigrants have come to Canada, accounting for nearly 90% of total population growth.

- Canada’s population increased by 362,000 in the third quarter of 2022, the highest quarterly population growth rate (+0.9%) since 1957.

- In the first nine months of 2022, Canada’s total population growth (+776,000 people) had already surpassed the annual growth in any full-year period since Confederation in 1867, with much of this growth resulting from an increase in non-permanent residents.

- Many newcomers’ skills are underused when entering the labour market in Canada.

- Most newcomers settle in Canada’s largest cities, which are experiencing deteriorating housing affordability and rising rental prices.

Data table for chart 5

| Net immigration | Net non-permanent residents | Natural increase | Total Change | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| number of persons | |||||

| 2019 | Q1 | 53,524 | 30,488 | 13,699 | 97,711 |

| Q2 | 88,356 | 65,112 | 24,816 | 178,284 | |

| Q3 | 95,894 | 80,013 | 32,901 | 208,808 | |

| Q4 | 67,456 | 15,217 | 16,290 | 98,963 | |

| 2020 | Q1 | 58,867 | 6,462 | 11,852 | 77,181 |

| Q2 | 32,122 | -24,348 | 13,210 | 20,984 | |

| Q3 | 41,602 | -66,091 | 24,371 | -118 | |

| Q4 | 35,487 | -3,151 | 4,066 | 36,402 | |

| 2021 | Q1 | 59,673 | 14,691 | 6,559 | 80,923 |

| Q2 | 69,799 | 12,174 | 20,152 | 102,125 | |

| Q3 | 117,866 | 57,767 | 24,342 | 199,975 | |

| Q4 | 121,790 | -38,851 | 6,726 | 89,665 | |

| 2022 | Q1 | 100,944 | 29,012 | -1,174 | 128,782 |

| Q2 | 111,995 | 157,310 | 15,677 | 284,982 | |

| Q3 | 115,468 | 225,198 | 21,787 | 362,453 | |

|

Note: Population growth in the second and third quarter of 2022 was led by large inflows of non-permanent residents. Sources: Statistics Canada, tables 17-10-0059-01 and 17-10-0040-01. |

|||||

Converging pressure points: Many economic and social challenges are interrelated

Description for Figure 1

The text in the bubble is, “Over 80% of the growth in the labour force comes from immigration. By 2041, immigrants could account for nearly one-third of Canada’s population, up from a quarter in 2021.”

There are three sub-bubbles pointing to the bubble.

The headline of the first sub-bubble is “Housing challenges.” This is followed by two sub-bullets. The first sub-bullet is, “In 2021, 1 in 10 households were in core housing need.” The second sub-bullet is, “Prior to the pandemic, 56% of recent immigrants were renters, compared with 27% of the total population.”

The headline of the second sub-bubble is “Healthcare strain.” This is followed by two sub-bullets. The first sub-bullet is, “Nursing vacancies in early 2022 were more than triple their level five years earlier.” The second sub-bullet is, “In July, the proportion of nurses working paid overtime was at record levels.”

The headline of the third sub-bubble is “Social cohesion.” This is followed by one sub-bullet. This sub-bullet is, “Nearly half of immigrants believe that Canadians share values on ethnic and cultural diversity, compared with one-quarter of Canadian-born people.”

There is a note below the last sub-bubble. The note is, “Core housing need refers to whether a household’s housing falls below at least one of the indicator thresholds for housing adequacy, affordability or suitability, and the household would have to spend 30% or more of its total before-tax income to pay the median rent of alternative local housing.”

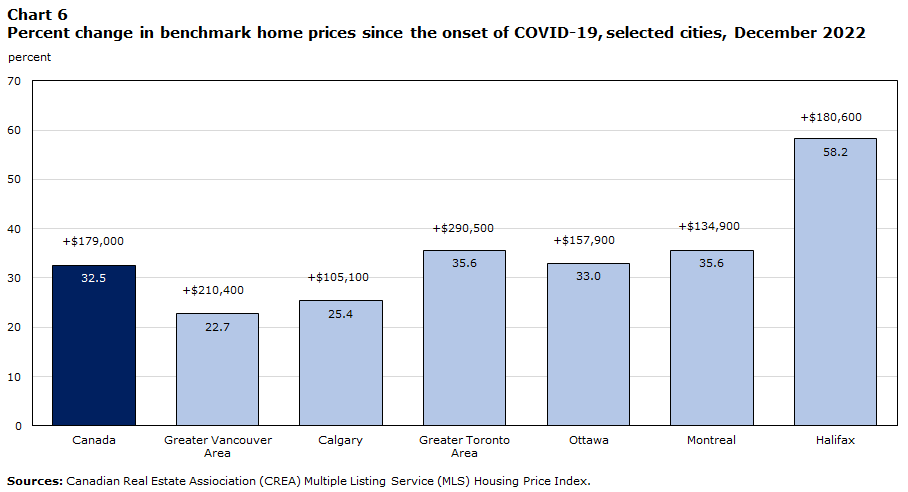

Economic challenges: Housing affordability deteriorates as debt levels rise

- While housing prices are well below peak levels reported in early 2022, the average cost of a home in Canada remains 33%, or $179,000, above pre-pandemic levels.

- Rising borrowing costs have pushed many potential homeowners out of the market, further straining an already hot rental market. The Bank of Canada’s housing affordability index, which measures how difficult it is to afford a home, has reached its highest point since 1990.

- Mortgage interest costs have risen 18% in the 12 months to December 2022 and have been a key source of inflationary pressure in recent months.

- Recent increases in living costs are having a negative impact on net saving and wealth, in particular among households with lower incomes, with lower wealth and in younger age groups.

- Net saving for the bottom 40% of income earners in the third quarter was down about 12% compared with the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, while economically vulnerable households also had higher-than-average increases in their debt.

Data table for chart 6

| Percent | Dollars | |

|---|---|---|

| Canada | 32.5 | 179,400 |

| Greater Vancouver Area | 22.7 | 210,400 |

| Calgary | 25.4 | 105,500 |

| Greater Toronto Area | 35.6 | 290,500 |

| Ottawa | 33.0 | 157,900 |

| Montreal | 35.6 | 134,900 |

| Halifax | 58.2 | 180,600 |

| Sources: Canadian Real Estate Assiociation (CREA) Multiple Listing Service (MLS) Housing Price Index. | ||

For more information: Real estate market: Definitions, graphs and data.

Economic challenges: While headline inflation eases, pressures on affordability remain widespread

- December 2022 marked the 21st consecutive month that headline consumer inflation has been above 3% and the 10th consecutive month above 6%.

- While headline inflation has eased from 40-year highs, underlying cost of living pressures, in particular around food and shelter, remain elevated as price increases continue to outpace wage growth.

- Over the course of 2022, there was a sharp rise in the share of grocery spending on food items that have seen yearly price increases of more than 10%, with little relief as headline inflation eased late in the year.

- In December 2022, grocery items with yearly price increases in the double-digit range accounted for two-thirds of food outlays.

- For context, grocery prices rose 8.6% from late 2014 to late 2019. They have risen 15.8% between December 2020 and December 2022.

Data table for chart 7

| 3.0% or less | 3.1% to 10.0% | Greater than 10% | |

|---|---|---|---|

| percent | |||

| 2021 | |||

| January | 93.9 | 5.2 | 0.9 |

| February | 75.5 | 23.6 | 0.9 |

| March | 75.2 | 18.5 | 6.3 |

| April | 89.4 | 10.6 | 0.0 |

| May | 76.7 | 23.3 | 0.0 |

| June | 62.0 | 32.9 | 5.1 |

| July | 67.5 | 30.6 | 1.9 |

| August | 52.5 | 43.7 | 3.8 |

| September | 44.3 | 43.7 | 12.0 |

| October | 32.9 | 59.6 | 7.5 |

| November | 30.7 | 60.8 | 8.5 |

| December | 19.5 | 71.2 | 9.3 |

| 2022 | |||

| January | 9.3 | 71.8 | 18.8 |

| February | 4.3 | 76.4 | 19.3 |

| March | 6.7 | 60.6 | 32.7 |

| April | 2.7 | 59.2 | 38.1 |

| May | 1.5 | 51.3 | 47.2 |

| June | 2.5 | 65.1 | 32.4 |

| July | 4.8 | 55.1 | 40.1 |

| August | 4.6 | 35.8 | 59.6 |

| September | 4.4 | 29.6 | 66.0 |

| October | 6.6 | 44.3 | 49.1 |

| November | 6.5 | 33.2 | 60.3 |

| December | 4.6 | 27.9 | 67.6 |

|

Note: Data are limited to food products purhased from stores. Source: Statistics Canada, Consumer Price Index, special tabulations. |

|||

For more information: Research to Insights: Consumer price inflation, recent trends and analysis (statcan.gc.ca).

Economic challenges: Financial stress builds as rising prices weigh on family budgets

- In April 2022, nearly three in four Canadians reported that rising prices were affecting their ability to meet day-to-day expenses.

- Three in 10 Canadians were very concerned about whether they could afford housing or rent.

- About one-quarter of Canadians reported that they have had to borrow money from friends or relatives, take on additional debt, or use credit to meet day-to-day expenses.

- By late 2022, almost half (44%) of Canadians said they were very concerned with their household’s ability to afford housing or rent.

- Young adults were among those most concerned over finances, with almost half of 35- to 44‑year-olds saying they found it difficult to meet their financial needs during the previous 12 months.

- In late 2022, one in four Canadians said they were unable to cover an unexpected expense of $500. This level rises to more than one-third among 35- to 44-year-olds.

Data table for chart 8

| Spring 2022 | Fall 2022 | |

|---|---|---|

| percent | ||

| Food | 66 | 76 |

| GasolineData table for chart 8 Note ‡ | 67 | 44 |

| Housing or rent | 30 | 44 |

Sources: Statistics Canada, Portrait of Canadian Society (PCS) and Canadian Social Survey (CSS). |

||

Social impacts: Impacts on well-being and mental health persist, in particular among young Canadians

- The COVID-19 pandemic has had significant impacts on the personal well-being of Canadians. Self-reported mental health declined sharply during the pandemic, especially among younger Canadians.

- In late 2021, about 6 in 10 working-age Canadians reported having a strong sense of meaning and purpose—indicating that they felt strongly that the things they do in life are worthwhile.

- Nearly two-thirds of seniors aged 65 to 74 reported having a strong sense of meaning and purpose, while just over half of 15- to 24-year-olds reported the same.

- Over the past two years, older adults were far more likely than younger Canadians to report high levels of perceived well-being based on a range of quality-of-life indicators. About 4 in 10 of 65- to 84-year-olds reported high well-being scores, compared with one-quarter of 20- to 29‑year-olds.

Data table for chart 9

| Men | Women | |

|---|---|---|

| percent | ||

| 15 to 24 years | 50 | 55 |

| 25 to 34 years | 48 | 58 |

| 35 to 44 years | 55 | 63 |

| 45 to 54 years | 61 | 61 |

| 55 to 64 years | 61 | 65 |

| 65 to 74 years | 65 | 65 |

| 75 years and older | 61 | 64 |

| Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Social Survey (CSS). | ||

Social challenges: Alcohol and drug use during the pandemic contributes to excess mortality among younger Canadians

- While COVID-19 has been a main driver of excess deaths overall, other factors are also driving excess mortality, in particular among younger Canadians.

- Deaths attributed to alcohol and drug use increased to new highs during the pandemic.

- Provisional data at the national level show that the number of deaths attributed to accidental poisoning and overdoses was 4,605 in 2020 and 6,310 in 2021, and these numbers are expected to increase with future revisions to the data.

- In comparison, at the previous height of the overdose crisis in 2017, 4,830 deaths were attributed to unintentional poisonings.

- Younger age groups made up a disproportionate number of deaths from overdoses. Among individuals aged younger than 45 years, there were 2,640 accidental poisoning deaths in 2020 and 3,600 in 2021.

Data table for chart 10

| Excess deaths | COVID-19 deaths | |

|---|---|---|

| percent | ||

| 0 to 44 years | 12.4 | 2.4 |

| 45 to 64 years | 16.7 | 12.2 |

| 65 to 84 years | 40.0 | 40.2 |

| 85 years and older | 30.8 | 45.2 |

| Source: Statistics Canada, special tabulations. | ||

Summary

- Economic resilience: Economy-wide output has increased in 16 of the last 18 months and, in December 2022, was 2.7% above pre-pandemic levels. While output growth moderated in late 2022, employment strengthened into early 2023 as the unemployment rate remained near a record low. Employment rates for core-aged workers are well above their pre-pandemic baseline.

- Pressures on affordability: While headline inflation eased in the second half of 2022, key sources of upward price pressure—including food and shelter—showed little sign of moderating. While home prices have fallen considerably from peak levels, housing affordability has deteriorated as mortgage interest costs have risen.

- Newcomers bolster population growth: In the third quarter of 2022, Canada posted the largest population growth rate (+0.9%) since the late 1950s. Population growth in recent quarters has reflected large increases in non-permanent residents, along with high levels of immigration. Non-permanent residents have also contributed substantially to employment gains in recent months.

- Persistent social impacts: Self-reported well-being and mental health were adversely affected by the pandemic, especially among young Canadians. From March 2020 to October 2022, there were 7.9% more deaths than expected had a pandemic not occurred. While COVID 19 has been a main driver of excess deaths overall, other factors have also been driving excess mortality, in particular among younger Canadians.

For more information, please contact

analyticalstudies@statcan.gc.ca

- Date modified: