The evolution of English–French bilingualism in Canada from 1901 to 2011

Archived Content

Information identified as archived is provided for reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It is not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards and has not been altered or updated since it was archived. Please "contact us" to request a format other than those available.

From its earliest days, Canada's two official languages, English and French, have been at the heart of the Canadian identity. Three decades after the birth of the Canadian confederation in 1867, Canadians were asked for the first time what languages they could speak in the 1901 Census. This, despite the fact the first census following Confederation—the 1871 Census of Canada—recorded that the two principal ethnic groups in the country, the British and the French, accounted for 92% of the population, 61% of which was British and 31%, French.

In the 1901 Census, the population aged 5 and older was asked three questions about language: one about maternal language, one about knowledge of English, and another about knowledge of French. Since then, each census has included at least one question about languages spoken, used or understood by Canadians. In every case, with the exception of the 1976 Census, there have been one or two questions about the ability to speak English or French. The 110 years of census data collected from 1901 to 2011 show that the rate of English–French bilingualism has not seen constant growth, but that its evolution follows the socio-historical changes taking place in the country.

Status in 1901

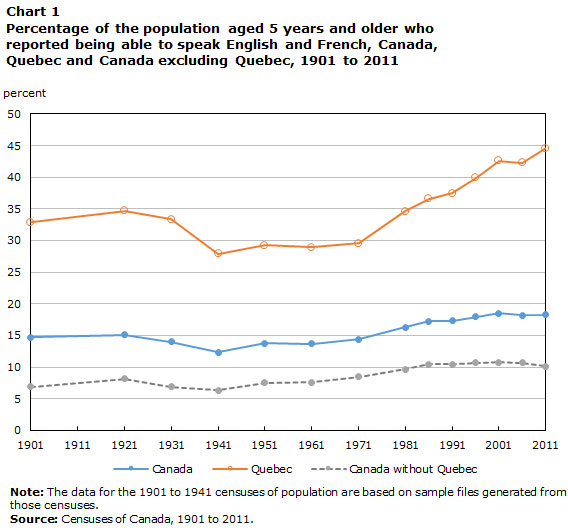

In 1901, Canada's population was just over 5.3 million, 88% of whom were 5 years of age or older. According to the 1901 Census, 78.5% of the population was able to speak English and 32.0% was able to speak French. In the province of Quebec, these percentages were 45.4% and 85.8% respectively. In Canada, 694,040 people could speak both languages. The proportion of the population speaking English and French (or bilingualism rate) was 14.7% for Canada as a whole, 32.9% for Quebec, and 6.9% for Canada outside Quebec.

From 1901 to 1941, a changing rate of bilingualism

The overall rate of English–French bilingualism in the population aged 5 and older changed considerably over the next century. In the entire Canadian population, the rate increased slightly between 1901 and 1921, then fell until 1941, when it appears to have reached a historic low of 12.4% in Canada, 27.9% in Quebec and 6.4% in Canada excluding Quebec.

The decline was greater in Quebec, with the rate of bilingualism falling from 34.7% to 27.9% from 1921 to 1941, compared with a decline of less than 2 percentage points in Canada outside Quebec. Several factors may have contributed to this decrease, including the strong growth in international immigration in the first three decades of the 20th century, the exodus of nearly a million French Canadians to New England from 1870 to 1930, and the high fertility rate among the Francophone population, especially in rural areas. That said, English–French bilingualism remained significantly higher in Quebec than in the rest of Canada, reflecting a different bilingualism dynamic in Quebec compared with the rest of the country.

Description for chart 1

| Year | Canada | Quebec | Canada without Quebec |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1901 | 14.7 | 32.9 | 6.9 |

| 1921 | 15.1 | 34.7 | 8.1 |

| 1931 | 14.0 | 33.4 | 6.9 |

| 1941 | 12.4 | 27.9 | 6.4 |

| 1951 | 13.7 | 29.2 | 7.5 |

| 1961 | 13.7 | 28.9 | 7.6 |

| 1971 | 14.4 | 29.6 | 8.5 |

| 1981 | 16.3 | 34.6 | 9.7 |

| 1986 | 17.2 | 36.6 | 10.5 |

| 1991 | 17.3 | 37.5 | 10.4 |

| 1996 | 17.9 | 39.9 | 10.7 |

| 2001 | 18.5 | 42.6 | 10.8 |

| 2006 | 18.2 | 42.3 | 10.7 |

| 2011 | 18.3 | 44.6 | 10.2 |

| Note: The data for the 1901 to 1941 censuses of population are based on sample files generated from those censuses. Source: Censuses of Canada, 1901 to 2011. |

|||

Major changes in the 1960s and 1970s

The following decades were marked by a rise in the overall rate of English–French bilingualism in the country. The increase began modestly in 1941, then strengthened across the country in the 1960s and in Quebec from 1970. This rise coincided with the work of the Royal Commission on Bilingualism and Biculturalism (1963–1970) and the adoption of the first Official Languages Act in 1969 that gave official, equal status to English and French in the federal government. The increase also reflected the growing recognition of the value of English–French bilingualism, and the impact of the first French immersion programs in the late 1960s, which were introduced first in Quebec, then throughout Canada.

Significant increase in bilingualism in Quebec in the 1970s

Some factors that contributed to the significant increase in English–French bilingualism in Quebec include the departure of many Anglophones—several of whom were unilingual—from Quebec to other provinces in the 1970s, the growing interest of young Anglophones in French immersion programs, and the effects of the implementation of Quebec's Charter of the French Language (enacted in 1977), particularly on the school attendance of children of immigrants and the language of work. The bilingualism rate rose from 29.6% to 34.6% from 1971 to 1981, an increase of 5 percentage points, compared with an increase of barely one percentage point in the rest of the country.

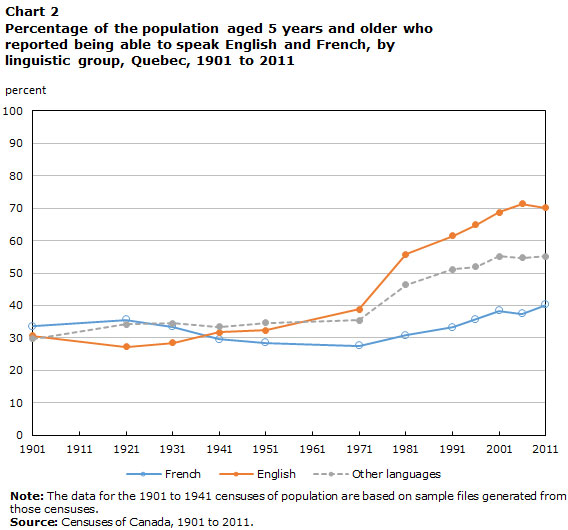

Beginning in 1971, the bilingualism rate of the English-mother-tongue population and the rest of the non-francophone population in Quebec grew faster than the rate of the population whose mother tongue was French, a gap that by 1991 had widened to almost 30 percentage points for Anglophones and about 15 percentage points for those with neither English nor French as their mother tongue. These differences are partly due to the fact that these populations were concentrated mainly in the Montréal census metropolitan area, where there was contact between French and other languages. In contrast, less than 40% of the population with French as its mother tongue lived in Montréal, and about one in two people lived in regions where little English was spoken.

Description for Chart 2

| Year | French | English | Other languages |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1901 | 33.6 | 30.7 | 29.7 |

| 1921 | 35.6 | 27.3 | 34.3 |

| 1931 | 33.4 | 28.4 | 34.5 |

| 1941 | 29.5 | 31.8 | 33.5 |

| 1951 | 28.5 | 32.4 | 34.6 |

| 1971 | 27.6 | 38.9 | 35.5 |

| 1981 | 30.8 | 55.8 | 46.4 |

| 1991 | 33.3 | 61.6 | 51.2 |

| 1996 | 35.7 | 64.9 | 51.9 |

| 2001 | 38.4 | 68.8 | 55.2 |

| 2006 | 37.4 | 71.3 | 54.7 |

| 2011 | 40.2 | 70.1 | 55.1 |

| Note: The data for the 1901 to 1951 censuses of population are based on sample files generated from those censuses. Source: Censuses of Canada, 1901 to 2011. |

|||

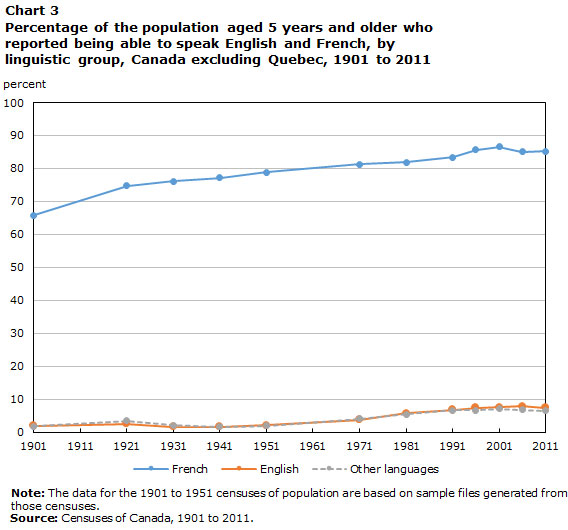

Rise in bilingualism in the rest of Canada from 1960 to 2001

In the rest of Canada, the rise in bilingualism was much less significant than in Quebec, where the bilingualism rate of Francophones was substantially higher than the rate for other linguistic groups.

For those with a mother tongue other than French, English–French bilingualism was most common among youth. The rise in bilingualism among non-Francophones outside Quebec since the 1960s is mainly due to higher enrollment in French-as-a-second-language programs, especially French immersion programs. For example, during the 2011–2012 school year, 356,500 elementary and secondary school students were enrolled in French immersion programs outside Quebec.

Description for Chart 3

| Year | French | English | Other languages |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1901 | 65.8 | 2.0 | 1.8 |

| 1921 | 74.8 | 2.6 | 3.4 |

| 1931 | 76.1 | 1.6 | 2.1 |

| 1941 | 77.2 | 1.6 | 1.6 |

| 1951 | 78.9 | 2.0 | 1.9 |

| 1971 | 81.2 | 3.7 | 4.1 |

| 1981 | 81.9 | 5.7 | 5.4 |

| 1991 | 83.5 | 6.8 | 6.6 |

| 1996 | 85.7 | 7.3 | 6.7 |

| 2001 | 86.7 | 7.5 | 7.1 |

| 2006 | 85.0 | 7.8 | 6.8 |

| 2011 | 85.3 | 7.4 | 6.4 |

| Note: The data for the 1901 to 1951 censuses of population are based on sample files generated from those censuses. Source: Censuses of Canada, 1901 to 2011. |

|||

Status from 2001 to 2011

From 2001 to 2011, the rate of bilingualism in Canada stagnated, and even declined. This decline was not offset by the increase observed in Quebec. One of the factors that contributed to this decrease outside Quebec was international immigration, which hovered around 250,000 people annually during this time and was the leading contributor to the growth of Canada's population. A strong majority of these immigrants had neither English nor French as their mother tongue, and less than 6% of these recent immigrants had knowledge of the two official languages when they arrived in the country. This directly impacts the evolution of Canada's English–French bilingualism rates.

Overall, the 20th century saw a significant rise in the number of bilingual Canadians

Since the start of the 20th century, the Canadian population aged 5 and older who can conduct a conversation in English and French has risen from 14.7% to 18.3%. Although this increase seems modest, the bilingual English–French population has increased substantially during the 20th century in Canada, from 656,530 in 1901 to almost 5.1 million in 2011.

Definitions

Bilingualism rate: The number of people who reported speaking or knowing English and French compared with the total population.

English or Anglophone: People whose native or principal language is English.

French or Francophone: People whose native or principal language is French.

References

Census of Canada, 1901: Canadian Families Project (CFP), University of Victoria, a 5% sample of the Canadian population. Open access data.

Censuses of Canada, 1921 to 1951: Canadian Century Research Infrastructure (CCRI), a 4% sample of the Canadian population (1921) and a 3% sample of the Canadian population (1931, 1941 and 1951). Data accessible through the research data centres.

Houle, R. and A. Cambron-Prémont. 2015. « Les concepts et les questions posées sur les langues aux recensements canadiens de 1901 à 1961 ». Cahiers québecois de démographie (à paraître) (French only).

Lepage, J.-F. and J.-P. Corbeil. 2013. The evolution of English–French bilingualism in Canada from 1961 to 2011. Insights on Canadian Society. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 75-006-X.

Contact information

To enquire about the concepts, methods or data quality of this release, contact René Houle (613-854-8473) or Jean-Pierre Corbeil (613-850-4762), Social and Aboriginal Statistics Division.

- Date modified: