Labour Force Survey, July 2022

Released: 2022-08-05

Employment was little changed (-31,000) in July, and the unemployment rate was unchanged at 4.9%.

Employment declined among older and core-aged women, while it was up among older men.

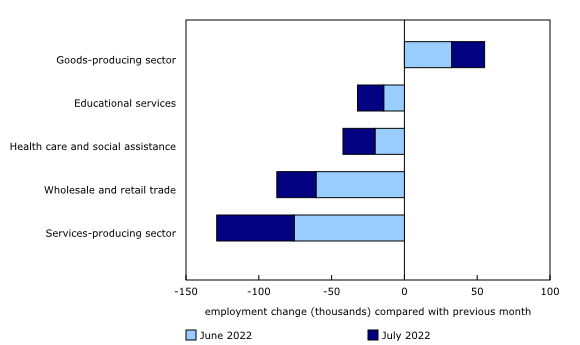

At the industry level, a decline in the services-producing sector was offset by an increase in the goods-producing sector.

A decrease in the number of employees working in the public sector was tempered by a gain among self-employed workers.

Fewer people were working in Ontario and Prince Edward Island, while employment was little changed in all other provinces.

Total hours worked were down 0.5% in July, after increasing 1.3% in June. Compared with a recent peak in March 2022, total hours worked were down 1.5% in July.

The average hourly wages of employees were up 5.2% (+$1.55 to $31.14) on a year-over-year basis in July, matching the pace of wage growth recorded in June.

Highlights

Employment little changed in July

Employment was little changed on a monthly basis in July (-31,000). Compared with May, employment was down 74,000 (-0.4%).

The number of public sector employees fell by 51,000 (-1.2%) in July, while the number of self-employed workers increased by 34,000 (+1.3%). The number of private sector employees was little changed.

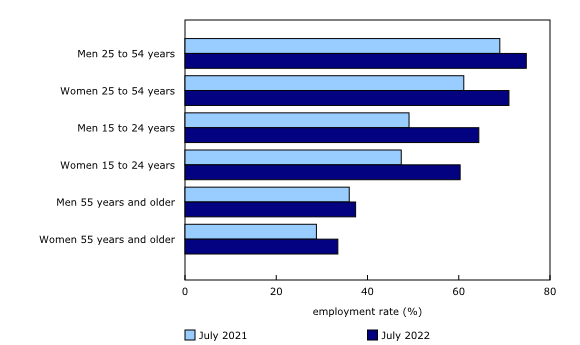

Employment fell among women aged 55 and older (-33,000; -1.7%) and women aged 25 to 54 (-31,000; -0.5%) in July. For men aged 55 and older, employment rose by 32,000 (+1.4%). It was little changed among youth aged 15 to 24 and men aged 25 to 54.

In the services-producing sector, employment fell by 53,000 (-0.3%) in July, with losses spread across several industries, including wholesale and retail trade, health care and social assistance, and educational services.

Employment rose in the goods-producing sector (+23,000; +0.6%) in July.

Total hours worked were down 0.5% in July.

The average hourly wages of employees were up 5.2% (+$1.55 to $31.14) on a year-over-year basis in July, matching the pace of wage growth recorded in June.

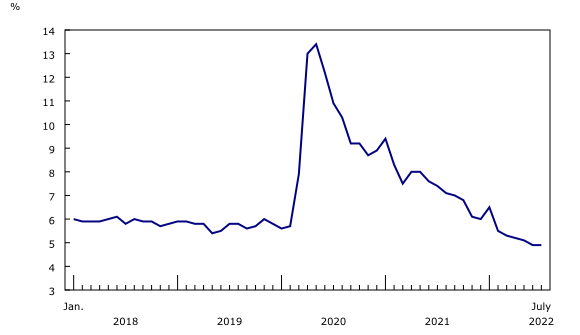

Unemployment rate remains at record low

The unemployment rate held steady at 4.9% in July, matching the historic low reached in June.

The adjusted unemployment rate—which includes people who were not in the labour force but wanted to work—remained at 6.8% in July, also matching its record low.

Long-term unemployment dropped 23,000 (-12.2%) to 162,000 in July, the third consecutive monthly decline.

Employment little changed in July after declining in June

While employment was little changed on a monthly basis in July (-31,000), cumulative declines from May to July totalled 74,000 (-0.4%). From May 2021 to May 2022, employment had increased by more than one million (+1,056,000; +5.7%).

Employment down among public sector employees, up among self-employed

Employment among public sector employees fell by 51,000 (-1.2%) in July, the first decline in the sector in 12 months. The decrease was largely concentrated in Ontario and Quebec. On a year-over-year basis, public sector employment was up 5.3% (+215,000).

After falling by 59,000 (-2.2%) in June, the number of self-employed workers increased by 34,000 (+1.3%) in July. Despite this increase, self-employment remained flat on a year-over-year basis and was 214,000 (-7.4%) below its pre-pandemic February 2020 level. Self-employment accounted for 13.6% of employment in July, 1.6 percentage points less than the average from 2017 to 2019 (15.2%).

Across the population, the share of workers who were self-employed ranged from 6.0% among Filipino Canadians and 7.6% among First Nations people living off-reserve to 18.3% among Korean Canadians and 18.6% among West Asian Canadians (three-month moving averages, not seasonally adjusted).

The number of employees working in the private sector was little changed in July and last increased in February 2022. Compared with 12 months earlier, the number of private sector employees was up 3.8% (+458,000) in July.

No indication of increased labour market churn

As of July, there was little indication that tight labour market conditions in recent months had led to an increase in the likelihood of workers voluntarily leaving a job or switching jobs. The number of core-aged (25 to 54 years) job leavers—people who left a job voluntarily in the previous 12 months and remained not employed in the Labour Force Survey (LFS) reference week—stood at 346,000 in July, down 3.4% (-12,000) compared with before the pandemic in July 2019. The number of core-aged job leavers trended down throughout 2020 and early 2021, and reached a record low of 217,000 in April 2021 (not seasonally adjusted).

Similarly, the job-changing rate—which measures the proportion of workers who remain employed from one month to the next but who change jobs between months—was 0.6% in both June and July, comparable to the period from 2016 to 2019, when it averaged 0.7%. The job changing rate reached a recent peak of 0.8% in January 2022.

Another indicator of job churn is the proportion of workers who have been in their current position for a short period. For example, the proportion of workers with job tenure of six months or less was 13.7% in July, virtually unchanged from 13.6% in July 2019.

Understanding labour market churn

Over the past year, as labour market conditions have tightened and Canadians have continued to adjust to the economic impacts of COVID-19, there has been renewed focus on labour market churn, or the rate at which people are changing jobs or changing employment status.

As with other measures of labour market conditions, understanding labour market churn requires the use of a broad range of complementary indicators, as well as consideration of past trends.

The labour force participation rate, especially for those aged 25 to 54, is an overall measure of the extent to which Canadians are either employed or looking for work, rather than pursuing other interests or responsibilities.

• In July 2019, the core-age labour force participation rate was 87.2%.

• After falling in the first months of the pandemic, the rate reached a record high of 88.6% in March 2022.

• In July 2022, the core-age labour force participation rate was 87.9%.

Information on labour force participation by sex, age group, and province is available from table 14-10-0287-01.

The job-changing rate measures the proportion of workers who remain employed from one month to the next but who change jobs between months.

• From 2016 to 2019, the job changing rate averaged 0.7% and never fell below 0.6% or rose above 0.8%.

• In July 2019, the job-changing rate was 0.7%.

• Three years later, in July 2022, the job-changing rate was essentially unchanged, at 0.6%.

Core-aged job leavers are people aged 25 to 54 who left a job voluntarily in the previous 12 months and remained not employed in the Labour Force Survey (LFS) reference week.

• In July 2019, the LFS measured 358,000 core-aged job leavers (not seasonally adjusted).

• This number trended down through late 2020 and early 2021, and reached a record low of 217,000 in April 2021.

• In July 2022, there were 346,000 core-aged job leavers, down 3.4% (-12,000) from July 2019.

Information on core-age job leavers is available by sex, age group, and province in table 14-10-0125-01.

Especially for those aged 55 and older, the proportion of people moving into retirement is a key measure of current labour market dynamics, as well as an indicator of future labour supply.

• In July 2019, of those aged 55 and older who had left a job in the previous 12 months and remained not employed, 74.1% had left their last job because they retired.

• In July 2022, the equivalent proportion was 76.9%.

Information on those leaving jobs due to retirement is available by sex, age group, and province in table 14-10-0125-01.

Job tenure is a measure of how long employees have been in their current job. An increase in the proportion of employees in low-tenure jobs can be an indication of increased labour market churn.

• In July 2019, 13.6% of employees had been in their position for six months or less.

• In July 2022, this proportion was 13.7%, essentially unchanged from three years earlier.

Information on job tenure by sex, age group, province, and other variables is available in tables 14-10-0050-01, 14-10-0054-01, and 14-10-0304-01.

Employment down among older and core-aged women

Employment among women aged 55 and older fell by 33,000 (-1.7%) in July. This was entirely due to a decline of 30,000 (-7.7%) among women aged 65 and older, as employment was little changed for women aged 55 to 64.

As with other age groups, women aged 55 and older move in and out of employment for a number of reasons. For some, it may be a response to short-term labour market conditions, while for others it is the result of a decision to retire. Among women aged 65 and older who were not employed in July and had left a job within the previous 12 months, 85.8% (66,000) did so due to retirement, up from 79.7% in July 2019.

Employment rose by 32,000 (+1.4%) for men aged 55 and older in July, fully offsetting the decline of 32,000 recorded in June. The increase was entirely due to men aged 55 to 64 and was driven by gains in manufacturing, and in professional, scientific and technical services. Employment was little changed among men aged 65 and older in July.

Employment among women aged 25 to 54 fell 31,000 (-0.5%) in July, the first decline since January 2022. While all of the July losses were in full-time work (-34,000; -0.7%), full-time employment for this group was up by 233,000 (+4.8%) compared with July 2021. From June to July 2022, the employment rate of core-aged women fell 0.5 percentage points to 80.8%, but remained close to the record high of 81.4% reached in May 2022.

Both employment and the employment rate (87.9%) were little changed among core-aged men in July.

For a fifth consecutive month, employment was little changed among youth aged 15 to 24 in July. The youth employment rate (58.6%) was similar to its pre-pandemic February 2020 level, as it has been since February 2022.

Across the youth population, the employment rate in July ranged from 43.7% among Chinese youth to 69.4% among Métis youth (three-month moving averages, not seasonally adjusted).

Employment rate among teenage returning students holding strong in July

To shed light on the summer employment of students, from May to August the LFS collects labour market data on youth aged 15 to 24 who were full-time students in March and who intend to return to school full time in September.

Favourable labour market conditions for students continued in July, as the overall employment rate for returning students aged 15 to 24 was 58.7%, 2.6 percentage points higher than in July 2019. The unemployment rate for returning students was 11.0% in July, the lowest July rate for this group since 1989 (not seasonally adjusted).

July data include information on the labour market experiences of returning students aged 15 and 16, many of whom were still in school until the end of June. The employment rate for this group (36.6%) was up 4.3 percentage points compared with July 2019, mostly due to an increase among male teens in this age group (+8.2 percentage points to 36.7%). More than three-fifths (62.1%) of students aged 15 and 16 who were employed in July were working in retail trade or accommodation and food services (not seasonally adjusted).

Employment rate in July reaches a record high among First Nations people living off-reserve

The employment rate of First Nations people living off-reserve rose 8.4 percentage points on a year-over-year basis to 61.0% in July, reaching its highest level since the beginning of the data series in 2007 (three-month moving averages, not seasonally adjusted).

The increase was particularly notable among First Nations youth aged 15 to 24, with the employment rate rising 15.3 percentage points to 64.4% among young men and 12.9 percentage points to 60.3% among young women. Sales and service occupations (+12,000; +39.2%) accounted for nearly half of overall year-over-year employment gains among First Nations youth (+26,000; +43.3%) (three-month moving averages, not seasonally adjusted).

The employment rate among Métis increased 4.3 percentage points on a year-over-year basis to 65.6% in July (three-month moving averages, not seasonally adjusted).

Share of workers working most of their hours at home edges up in July

With the number of COVID-19 cases increasing in July, some employers and workers may have started to respond by increasing the number of hours worked from home. Among people who were at work in July, the proportion who worked most of their hours at home edged up 0.4 percentage points to 24.2% (population aged 15 to 69; not seasonally adjusted).

Alongside short-term shifts in work location, many employers have continued to implement a longer-term transition towards hybrid work arrangements in recent months, with employees working some hours at home and some hours in a location other than home. In July, the proportion of employees who usually work some hours at home and some hours at a location other than home increased 1.2 percentage points to 7.4% (population aged 15 to 69; not seasonally adjusted). The proportion of employees with hybrid arrangements has more than doubled since January 2022 (up 4.1 percentage points from 3.3%).

Unemployment rate remains at record low

The unemployment rate held steady at 4.9% in July, matching the historic low reached in June. There was little movement in the rate across the major demographic groups. Among those aged 25 to 54, the unemployment rate was 4.0%, and was little changed compared with June for both core-aged men (4.0%) and women (4.1%). The rate was also little changed in July for those aged 55 and older (4.7%) and for youth aged 15 to 24 (9.2%).

The total number of unemployed people held steady at 1.0 million in July. In addition, 426,000 people wanted a job in July but did not look for one, and therefore did not meet the definition of unemployed. This was little changed for the sixth consecutive month. The adjusted unemployment rate—which accounts for this source of potential labour supply—remained at 6.8% in July, the lowest rate since comparable data first became available in 1997.

Long-term unemployment falls for the second consecutive month

Long-term unemployment dropped 23,000 (-12.2%) to 162,000 in July, the second consecutive monthly decline. While some people in long-term unemployment eventually transition to employment, others leave the labour force, either because they are discouraged from actively searching for work, or to pursue other activities. From May to July, of the people who had been continuously unemployed for 27 weeks or more in the previous month, an average of 21.0% left the labour force, 12.0% transitioned into employment, and 67.0% remained unemployed (three-month moving averages, not seasonally adjusted.)

Long-term unemployment expressed as a proportion of the total labour force dropped to 0.8% in July (-0.1 percentage points), after returning to its pre-pandemic level for the first time in June.

Core-age labour force participation rate eases down from historic high

The overall labour force participation rate—the proportion of the population aged 15 and older who were either employed or unemployed—decreased 0.2 percentage points to 64.7% in July, following a 0.4 percentage point drop in June.

Among people aged 25 to 54, the participation rate continued to ease down from the record high of 88.6% reached in March 2022. The rate fell 0.3 percentage points to 87.9% in July, the third decrease in four months, and 0.7 percentage points below the record set in March. Declines in July were seen among both core-aged men (-0.2 percentage points to 91.5%) and core-aged women (-0.5% percentage points to 84.3%).

Among core-aged women, the labour force participation rate in July was relatively low among West Asian (70.9%) and Korean women (72.7%) and relatively high among Filipino women (89.0%). Among core-aged men, the participation rate ranged from 81.0% for First Nations men living off-reserve to 94.5% for South Asian men and 95.5% for Filipino men (three-month moving averages, not seasonally adjusted).

Among people aged 55 and older, the labour force participation rate (36.1%) was unchanged in July, after falling in May and June.

The proportion of youth aged 15 to 24 who were either employed or unemployed was also little changed in July at 64.5%.

Employment declines for a second consecutive month in the services-producing sector

Employment fell by 53,000 (-0.3%) in the services-producing sector in July, with month-over-month losses in wholesale and retail trade (-27,000; -0.9%), health care and social assistance (-22,000; -0.8%), educational services (-18,000; -1.2%), and business building and other support services (-12,000; -1.7%). Finance, insurance, real estate, rental and leasing (+11,000; +0.8%) was the only services-producing industry to see employment gains in the month.

For a second consecutive month, employment declines in services were moderated by an increase in the goods-producing sector, where employment rose 23,000 (+0.6%) in July. Compared with 12 months earlier, employment in the goods-producing sector was up by 177,000 (+4.6%), compared with an increase of 510,000 (+3.4%) in services over that same period.

Wholesale and retail trade contributes the most to losses in the services-producing sector

The number of people working in wholesale and retail trade fell by 27,000 (-0.9%) in July, the second consecutive monthly decline in the industry. The vast majority of the net decrease took place in Ontario (-14,000; -1.3%) and Quebec (-12,000; -1.8%). According to the latest data from the Survey of Employment, Payrolls and Hours, payroll employment in retail trade fell in both April and May. Within retail trade, 9 of the 12 subsectors recorded payroll employment decreases in May.

Compared with 12 months earlier, employment in wholesale and retail trade—as measured by the LFS—was up 82,000 (+2.9%) in July.

Employment falls in health care and social assistance despite growing pressure on health care systems

The number of people working in health care and social assistance also declined for a second consecutive month, falling by 22,000 (-0.8%) in July. On a year-over-year basis, employment in the industry was little changed.

The employment declines in June and July occurred despite continued strong labour demand in the industry. According to the Job Vacancy and Wage Survey, there were 143,400 job vacancies in health care and social assistance in May, up 20.0% (+23,900) from May 2021. This industry includes hospitals, ambulatory health care services, and nursing and residential care facilities, as well as a variety of social services such as community food and housing services, and child day-care services.

Fewer people working in educational services

Employment in educational services was down for a second consecutive month, falling by 18,000 (-1.2%) in July. The majority of the decrease occurred in Quebec (-14,000; -3.8%). On a year-over-year basis, there were 42,000 (+2.9%) more people working in the industry in July.

Employment declines in Ontario and Prince Edward Island

Employment declined in both Ontario and Prince Edward Island in July, while there was little change in all other provinces. For further information on key province and industry level labour market indicators, see "Labour Force Survey in brief: Interactive app."

Employment in Ontario fell by 27,000 (-0.4%) in July, with declines in full-time work partly offset by gains in part-time employment. The provincial unemployment rate rose 0.2 percentage points to 5.3%. Industries with notable employment losses in the month included wholesale and retail trade, and educational services. Employment rose in manufacturing and in finance, insurance, real estate, rental and leasing. In the census metropolitan area (CMA) of Toronto, both employment and the unemployment rate (5.7%) were little changed. Across the province, the unemployment rate ranged from a high of 6.5% in Windsor CMA to a low of 3.2% in Guelph CMA (three-month moving averages).

In Prince Edward Island, employment fell by 2,300 (-2.6%) in July, largely erasing gains in May and June which totalled 2,700 (+3.2%). The unemployment rate increased 0.8 percentage points to 5.7% in July.

Following declines in two of the previous three months, employment held steady in Quebec in July and the unemployment rate (4.1%) continued to hover around a record low. In the Montréal CMA, employment was little changed, and the unemployment rate remained at 4.7%.

In Manitoba, employment was little changed in July, following a gain in June. The unemployment rate in the province continued on a steady downward trend, falling 0.3 percentage points to 3.5%, on par with previous record lows seen in various months from 2006 to 2008. The Winnipeg CMA posted an unemployment rate of 4.2% (three-month moving average).

In the spotlight: wages and multiple jobholding; absences and paid sick leave; and overtime among nurses

Multiple jobholding stable amid accelerating inflation

Average hourly wages for employees rose 5.2% (+$1.55 to $31.14) on a year-over-year basis in July, the same year-over-year rate of increase observed in June (+5.2%; +$1.54). For a second consecutive month, average hourly wages grew at a similar pace among part-time (+5.0%; +$1.05) and full-time (+4.9%; +$1.52) employees in July. Earlier in 2022, wage growth had been slower among part-time employees than among their full-time counterparts. The most recent inflation data indicated that the Consumer Price Index rose 8.1% on a year-over-year basis in June, the largest annual change in nearly 40 years.

When consumer prices increase at a faster rate than wages, workers may respond in a number of ways, including changing their spending habits, working more hours, or looking for a higher-paying job. In addition, some workers, particularly those whose main job is part-time or lower-paid, may take on a second job to help pay their bills. Given current labour market conditions, which include historic low unemployment rates and an unprecedented number of vacant positions, this may be a particularly viable option for many.

As of July 2022, there was little indication that rising prices or other factors have so far led to an increase in multiple jobholding. The proportion of employed people who held more than one job was 5.4% in the month, unchanged from one year earlier, and similar to the average for the month of July recorded from 2017 to 2019 (5.6%). In the context of unprecedented job losses associated with COVID-19, the multiple jobholding rate had dropped to a low of 3.9% in July 2020.

Consistent with historical trends, workers employed part-time at their main job were more likely than full-time workers to be multiple jobholders in July. Around 1 in 10 (10.1%) workers whose main job offered less than 30 hours per week had a second job, more than double the rate among those whose main job was full-time (4.5%). This multiple jobholding rate was similar to pre-pandemic levels for both full-time and part-time workers.

In the context of affordability, people working in lower wage positions can be particularly vulnerable to rising consumer prices, and are typically more likely to hold multiple jobs. Employees whose usual hourly wage at their main job was within the lowest wage quartile in July ($19.33 per hour or less) were more likely (6.9%) to hold multiple jobs than employees in the highest wage quartile (3.8%), in line with historical trends.

While working more than one job may be an indication that the main job provides insufficient earnings, people may hold multiple jobs for other reasons, including to help accumulate skills and expertise in other occupations. For more information on historical trends in multiple jobholding, see "Multiple jobholders, 1976 to 2021," part of the Quality of Employment in Canada publication.

No spike in absences during July reference week

In the July reference week (July 10 to 16), as workers and employers faced the seventh wave of COVID-19, 5.5% (947,000) of employees were absent from work due to illness or disability. This was 0.6 percentage points higher than the July average from 2017 to 2019, but less than the record high of 10.0% set in January 2022, during the fifth wave of COVID-19 (not seasonally adjusted).

In the health care and social assistance industry, which typically has one of the highest proportions of employees absent due to illness and disability, the proportion in July 2022 (8.7%) exceeded the average in the month of July from 2017 to 2019 by 1.6 percentage points but remained below the high reached in January 2022 (13.3%). Other industries where the proportion of employees missing work for this reason was somewhat higher than the average July included retail trade (+1.5 percentage points to 6.0%), construction (+1.1 percentage points to 4.9%) and natural resources (+0.9 percentage points to 4.3%).

With working from home now more common in certain parts of the labour market, some employers and workers may be more able to adapt to changing public health conditions by temporarily increasing the amount of time worked from home. Among people who were at work in July, the proportion who worked most of their hours at home edged up 0.4 percentage points to 24.2% (population aged 15 to 69; not seasonally adjusted).

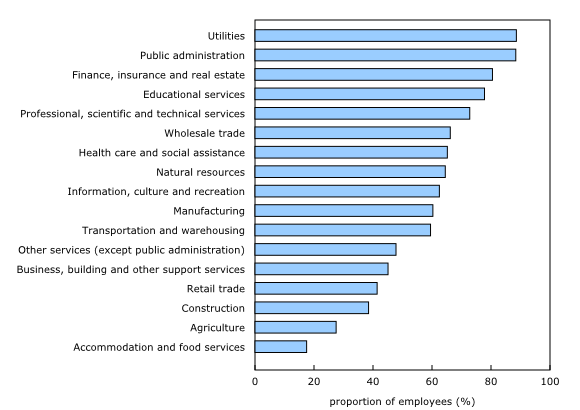

In addition to factors like close contact with others which may affect the likelihood of becoming sick, absences due to illness or disability may be influenced by access to paid sick leave. New annual data from the LFS shed light on this important aspect of quality of employment, showing that 6 in 10 employees (59.9%) had paid sick leave benefits in 2021. This included 67.8% of full-time employees and 64.5% of permanent employees.

The share of employees with access to paid sick leave varied widely across industries in 2021, with the highest rates in utilities (88.6%), public administration (88.4%) and finance, insurance, real estate, rental and leasing (80.5%). Industries where the proportion of employees with paid sick leave was below average included accommodations and food services (17.5%), agriculture (27.5%), construction (38.5%) and retail trade (41.4%).

More than one in five nurses worked paid overtime in July

As Canada faced a seventh wave of COVID-19 in June and July, some hospitals across the country reported that the combination of COVID-19 infections among staff and labour shortages had forced them to reduce some services, including temporarily closing some emergency rooms.

These reductions and closures occurred against the backdrop of unprecedented levels of unmet labour demand in the health care sector, particularly among nurses. While LFS recorded an employment increase of 30,000 (+8.8%) in professional occupations in nursing from December 2020 to December 2021, this was not sufficient to meet rising labour demand, and the Job Vacancy and Wage Survey reported 23,620 vacant nursing positions in the first quarter of 2022. Nursing vacancies in early 2022 were more than triple (+219.8%) the level of five years earlier, illustrating the extent to which longer-term trends may be contributing to the current challenges facing hospitals and other health care employers.

Meeting the demand for labour can be particularly challenging if workplaces face high levels of absences among existing employees. In the context of the seventh wave of COVID-19, absences among nurses due to illness or disability were somewhat above the average seen in the years before the pandemic. In July 2022, 11.2% of nurses who were employees were off sick for at least part of the week, 2.8 percentage points higher than the average of 8.4% seen in July from 2017 to 2019 (three-month moving averages, not seasonally adjusted).

One of the ways hospitals and clinics can respond to absences and unmet labour demand is by scheduling more employees to work extra hours. In July 2022, the proportion of nurses working paid overtime was at its highest level for the month of July since comparable data became available in 1997. More than one in five (21.6%) employees working in professional occupations in nursing and who were not absent from work completed paid overtime hours in July, more than double the proportion for all other employees who were at work (9.7%) and up 2.2 percentage points compared with July 2021 (three-month moving averages, not seasonally adjusted).

The leading role that health care professionals, including nurses, have played in responding to COVID-19 has focussed attention on various aspects of their quality of employment, including the extent to which nurses work 49 or more hours per week, the threshold for very long work hours defined by the International Labour Organization.

In July, 7.8% of nurses who were at work worked 49 or more total hours during the LFS reference week, a higher proportion than one year earlier (7.3%) and well above the average level observed in the month of July from 2017 to 2019 (5.4%). For more information on workers who usually work long hours, see "Long working hours, 1976 to 2021," part of the Quality of Employment in Canada publication.

Sustainable Development Goals

On January 1, 2016, the world officially began implementation of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development—the United Nations' transformative plan of action that addresses urgent global challenges over the next 15 years. The plan is based on 17 specific sustainable development goals.

The Labour Force Survey is an example of how Statistics Canada supports the reporting on the Global Goals for Sustainable Development. This release will be used in helping to measure the following goals:

Note to readers

The Labour Force Survey (LFS) estimates for July are for the week of July 10 to 16, 2022.

The LFS estimates are based on a sample and are therefore subject to sampling variability. As a result, monthly estimates will show more variability than trends observed over longer time periods. For more information, see "Interpreting Monthly Changes in Employment from the Labour Force Survey."

This analysis focuses on differences between estimates that are statistically significant at the 68% confidence level.

LFS estimates at the Canada level do not include the territories.

The LFS estimates are the first in a series of labour market indicators released by Statistics Canada, which includes indicators from programs such as the Survey of Employment, Payrolls and Hours (SEPH); Employment Insurance Statistics; and the Job Vacancy and Wage Survey. For more information on the conceptual differences between employment measures from the LFS and those from the SEPH, refer to section 8 of the Guide to the Labour Force Survey (71-543-G).

Since March 2020, all LFS face-to-face interviews have been replaced by telephone interviews conducted by interviewers working from their home to protect the health of both respondents and interviewers. While this has resulted in a decline in the LFS response rate, more than 49,000 interviews were completed in July and in-depth data quality evaluations conducted each month confirm that the LFS continues to produce an accurate portrait of Canada's labour market.

The employment rate is the number of employed people as a percentage of the population aged 15 and older. The rate for a particular group (for example, youths aged 15 to 24) is the number employed in that group as a percentage of the population for that group.

The unemployment rate is the number of unemployed people as a percentage of the labour force (employed and unemployed).

The participation rate is the number of employed and unemployed people as a percentage of the population aged 15 and older.

Full-time employment consists of persons who usually work 30 hours or more per week at their main or only job.

Part-time employment consists of persons who usually work less than 30 hours per week at their main or only job.

Total hours worked refers to the number of hours actually worked at the main job by the respondent during the reference week, including paid and unpaid hours. These hours reflect temporary decreases or increases in work hours (for example, hours lost due to illness, vacation, holidays or weather; or more hours worked due to overtime).

In general, month-to-month or year-to-year changes in the number of people employed in an age group reflect the net effect of two factors: (1) the number of people who changed employment status between reference periods, and (2) the number of employed people who entered or left the age group (including through aging, death or migration) between reference periods.

Supplementary indicators used in the July 2022 analysis

Employed, worked zero hours includes employees and self-employed who were absent from work all week, but excludes people who have been away for reasons such as 'vacation,' 'maternity,' 'seasonal business,' and 'labour dispute.'

Employed, worked less than half of their usual hours includes both employees and self-employed, where only employees were asked to provide a reason for the absence. This excludes reasons for absence such as 'vacation,' 'labour dispute,' 'maternity,' 'holiday,' and 'weather.' Also excludes those who were away all week.

Not in labour force but wanted work includes persons who were neither employed, nor unemployed during the reference period and wanted work, but did not search for reasons such as 'waiting for recall (to former job),' 'waiting for replies from employers,' 'believes no work available (in area, or suited to skills),' 'long-term future start,' and 'other.'

Unemployed, job searchers were without work, but had looked for work in the past four weeks ending with the reference period and were available for work.

Unemployed, temporary layoff or future starts were on temporary layoff due to business conditions, with an expectation of recall, and were available for work; or were without work, but had a job to start within four weeks from the reference period and were available for work (don't need to have looked for work during the four weeks ending with the reference week).

Labour underutilization rate (specific definition to measure the COVID-19 impact) combines all those who were unemployed with those who were not in the labour force but wanted a job and did not look for one; as well as those who remained employed but lost all or the majority of their usual work hours for reasons likely related to COVID-19 as a proportion of the potential labour force.

Potential labour force (specific definition to measure the impact of COVID-19) includes people in the labour force (all employed and unemployed people), and people not in the labour force who wanted a job but didn't search for reasons such as 'waiting for recall (to former job),' 'waiting for replies from employers,' 'believes no work available (in area, or suited to skills),' 'long-term future start,' and 'other.'

New data table on the labour force characteristics of Indigenous peoples living off-reserve

A new data table (14-10-0401-01) presenting labour force characteristics of Indigenous peoples living off-reserve is now available on the Statistics Canada website. This new table provides estimates based on 3-month moving averages and can help users monitor recent trends in employment, unemployment and labour force participation among Indigenous peoples.

New information in July

The information on employment benefits (including paid sick leave) comes from one of five new questions that were added to the LFS in March 2020. The topics of the other four questions were: the main activity of people not in the labour force, the total number of jobs held by multiple job holders, the earnings of self-employed workers and working by necessity or choice among people aged 60 and older. Results for these five questions are now available as custom requests for the period from March 2020 to February 2022. Results for more recent months, as well as ongoing monthly updates, will be available in Fall 2022.

Seasonal adjustment

Unless otherwise stated, this release presents seasonally adjusted estimates, which facilitate comparisons by removing the effects of seasonal variations. For more information on seasonal adjustment, see Seasonally adjusted data – Frequently asked questions.

The seasonally adjusted data for retail trade and wholesale trade industries presented here are not published in other public LFS tables. A seasonally adjusted series is published for the combined industry classification (wholesale and retail trade).

Next release

The next release of the LFS will be on September 9, 2022. August data will reflect labour market conditions during the week of August 14 to 20, 2022.

Correction

In November 2022, an error was identified with the data for the following racialized groups: Arab and Latin American. Estimates for these groups will not be available while the data is being revised.

Products

More information about the concepts and use of the Labour Force Survey is available online in the Guide to the Labour Force Survey (71-543-G).

The product "Labour Force Survey in brief: Interactive app" (14200001) is also available. This interactive visualization application provides seasonally adjusted estimates by province, sex, age group and industry.

The product "Labour Market Indicators, by province and census metropolitan area, seasonally adjusted" (71-607-X) is also available. This interactive dashboard provides customizable access to key labour market indicators.

The product "Labour Market Indicators, by province, territory and economic region, unadjusted for seasonality" (71-607-X) is also available. This dynamic web application provides access to labour market indicators for Canada, province, territory and economic region.

The product Labour Force Survey: Public Use Microdata File (71M0001X) is also available. This public use microdata file contains non-aggregated data for a wide variety of variables collected from the Labour Force Survey. The data have been modified to ensure that no individual or business is directly or indirectly identified. This product is for users who prefer to do their own analysis by focusing on specific subgroups in the population or by cross-classifying variables that are not in our catalogued products.

Contact information

For more information, or to enquire about the concepts, methods or data quality of this release, contact us (toll-free 1-800-263-1136; 514-283-8300; infostats@statcan.gc.ca) or Media Relations (statcan.mediahotline-ligneinfomedias.statcan@statcan.gc.ca).

- Date modified: