Indigenous population continues to grow and is much younger than the non-Indigenous population, although the pace of growth has slowed

Archived Content

Information identified as archived is provided for reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It is not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards and has not been altered or updated since it was archived. Please "contact us" to request a format other than those available.

Released: 2022-09-21

Indigenous peoples, their communities, cultures and languages have existed since time immemorial in the land now known as Canada. The term "Indigenous peoples" refers to three groups—First Nations people, Métis and Inuit—who are recognized in the Constitution Act. However, while these groups are representative of the Indigenous population as a whole, each is tremendously diverse. This diversity is reflected in over 70 Indigenous languages that were reported during the 2021 Census, over 600 First Nations who represent their people across the country, the plurality of groups representing Métis nationhood, and the four regions and 50 communities of Inuit Nunangat that Inuit call home.

Much of Canada's cultural, economic and political landscape has been shaped by the achievements of Indigenous people. Generations of Indigenous people, including leaders, Elders, healers, educators, business leaders, artists and activists, have made invaluable contributions, touching all aspects of life in Canada.

Over multiple decades, census data have revealed that the Indigenous population has grown quickly, at a pace far surpassing that of the non-Indigenous population. There are two reasons for this growth. The first, often called "natural growth," relates to higher birth rates and increasing lifespans. The second has been termed "response mobility," which refers to people who once responded to the Indigenous identity questions one way on the census questionnaire, but now respond differently. Over time, respondents who had previously not identified as Indigenous have become more likely to do so. This may be related to personal reflection, social factors or external factors such as changes to legislation or court rulings.

The Indigenous population in Canada is one of the largest among countries that share a similar colonial history. In 2021, 1.8 million Indigenous people were enumerated during the census. This was more than double the number of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people living in Australia (812,728) in 2021, and the number of Maori in New Zealand (775,836) in 2018. In 2021, Indigenous people accounted for 5.0% of the total population in Canada, a larger share than in Australia (3.2%) but lower than in New Zealand (16.5%).

The colonial history of Canada has profoundly impacted Indigenous peoples, their governance, languages and cultures. However, through the efforts and resilience of Indigenous people and their communities, important steps have been taken toward reconciliation and the rebuilding of ties to the unique cultures and languages of First Nations people, Métis and Inuit. In recent years, federal initiatives have been implemented, including the Indigenous Languages Act; the Act respecting First Nations, Inuit and Métis children, youth and families, as well as modern treaty negotiations.

The 2021 Census was particularly challenging to conduct amid the respect for isolation due to the COVID-19 pandemic as well as regional forest fires that interfered with data collection. Because of these factors, enumeration could not be completed in 63 of the 1,026 census subdivisions that are classified as First Nations reserves.

Despite the challenges posed to in-person collection, the Census of Population remains the most comprehensive source of community-level data for the Indigenous population in Canada and robust data are available for First Nations, Métis and Inuit communities. Census data are used to inform policy and community work for Indigenous peoples, and are comparable across time and across multiple levels of geography. The collection and dissemination of these data would not have been possible without the participation of First Nations people, Métis and Inuit across Canada.

Highlights

The 2021 Census counted 1.8 million Indigenous people, accounting for 5.0% of the total population in Canada, up from 4.9% in 2016.

The Indigenous population grew by 9.4% from 2016 to 2021, surpassing the growth of the non-Indigenous population over the same period (+5.3%). However, this growth was not as rapid as in years past. For example, from 2011 to 2016, the Indigenous population grew by 18.9%—more than double the 2021 growth rate.

For the first time, the Census of Population enumerated more than 1 million First Nations people living in Canada (1,048,405).

In 2021, there were 624,220 Métis living in Canada, up 6.3% from 2016.

In 2021, there were 70,545 Inuit living in Canada, with just over two-thirds (69.0%) living in Inuit Nunangat—the homeland of Inuit in Canada.

The Inuit population living outside Inuit Nunangat grew at a faster pace than the population within the Inuit homeland (+23.6% versus +2.9%).

The Indigenous population living in large urban centres—801,045 people—has grown by 12.5% from 2016 to 2021.

The Indigenous population was 8.2 years younger, on average, than the non-Indigenous population overall. Just over one in six working-age Indigenous people (17.2%) were "close to retirement" (55 to 64 years), compared with 22.0% of the non-Indigenous population.

For First Nations, Métis and Inuit families, grandparents often play an important role in raising children as well as in passing down values, traditions and cultural knowledge to younger generations. In 2021, 14.2% of Indigenous children lived with at least one grandparent, compared with 8.9% of non-Indigenous children.

Indigenous people were more likely than the non-Indigenous population to be living in a dwelling that was in need of major repairs (16.4% versus 5.7%) or live in crowded housing (17.1% versus 9.4%) in 2021.

In 2021, almost one in five Indigenous people in Canada (18.8%) lived in a low-income household, using the low-income measure, after tax. This was down nearly 10 percentage points from 2016. The decline was likely driven by government transfers in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

In Canada, 237,420 Indigenous people could speak an Indigenous language well enough to conduct a conversation. While the number of people with an Indigenous mother tongue has been in decline, there has been growth in the number of Indigenous second-language speakers.

Over 1.8 million Indigenous people counted in the 2021 Census

The 2021 Census counted 1,807,250 Indigenous people, accounting for 5.0% of the total population of Canada, up from 4.9% in 2016.

The census questionnaire asked respondents if they were First Nations, Métis or Inuit—the three Indigenous groups recognized in the Constitution Act, 1982. Those who reported being First Nations accounted for over half (58.0%) of the Indigenous population, while just over one-third (34.5%) were Métis and 3.9% were Inuit. The remaining share of the population was those who reported multiple Indigenous identities (1.6%)—for example First Nations and Métis—and those who were part of the Indigenous population not included elsewhere (1.9%).

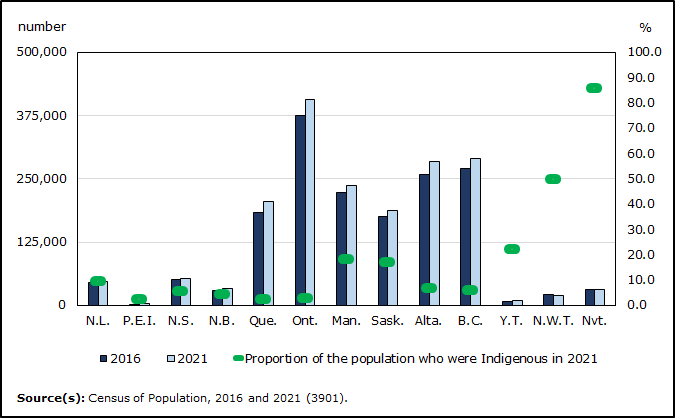

Ontario had the largest Indigenous population of all provinces and territories in 2021, at 406,590 people, accounting for 2.9% of people in the province. British Columbia had the next largest Indigenous population, at 290,210, accounting for 5.9% of people in the province, followed by Alberta (284,470 people, or 6.8%) and Manitoba (237,190 people, or 18.1%).

In 2021, Indigenous people made up a large share of the total population in the territories, accounting for over four-fifths (85.8%) of the population of Nunavut, almost half (49.6%) in the Northwest Territories and over one-fifth (22.3%) in Yukon. Provincially, Manitoba's population had the highest share of Indigenous people (18.1%), followed by Saskatchewan (17.0%), Newfoundland and Labrador (9.3%), and Alberta (6.8%).

Indigenous population still growing faster than non-Indigenous population, but pace of growth has slowed

The Indigenous population grew by 9.4% from 2016 to 2021, almost twice the pace of growth of the non-Indigenous population over the same period (+5.3%). Population projections for First Nations people, Métis and Inuit suggest that the Indigenous population could reach between 2.5 million and 3.2 million over the next 20 years.

The faster growth of the Indigenous population is generally attributed to higher birth rates, combined with changes in the way respondents answer the census questionnaire from one census to the next. In general, respondents have become more likely to identify as Indigenous over time. The reasons people are more likely to identify as Indigenous may be related to social factors and external factors, such as changes to legislation or court rulings. Also, past findings have highlighted a connection between having both Indigenous and non-Indigenous ancestry and response mobility.

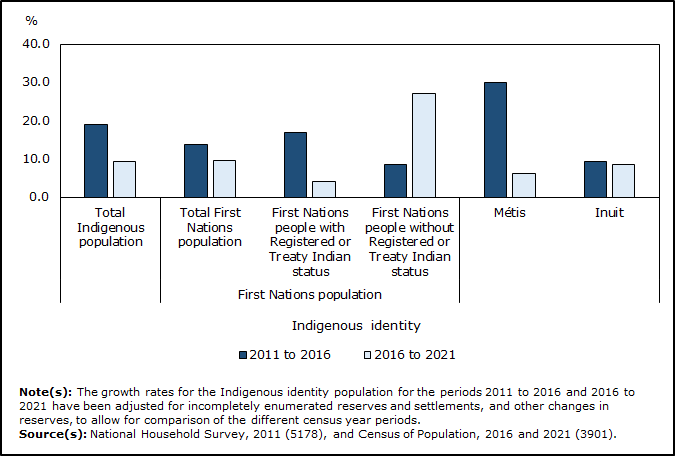

While the Indigenous population continues to grow more quickly than the non-Indigenous population, the difference in growth between the two groups (+9.4% versus +5.3%) was not as large as it was during previous iterations of the census. For example, the Indigenous population grew at over four times the pace of the non-Indigenous population from 2011 to 2016 (+18.9% versus +4.2%).

The First Nations population grew by 9.7% overall from 2016 to 2021. However, the pace of growth was much slower for First Nations people with Registered or Treaty Indian status (+4.1%), compared with those without Registered or Treaty Indian status (+27.2%). The Métis population grew by 6.3% over the five-year period, while the Inuit population grew by 8.5%.

In 2016, Indigenous children aged 4 years and younger accounted for 8.7% of the total Indigenous population, but by 2021 this share had fallen to 7.6%. While this accounts for some of the difference in growth rates, it does not explain it entirely. This may suggest that the second reason for Indigenous population growth—response mobility—was not as prevalent in 2021 as in previous census cycles.

The growth of the Indigenous population can also be viewed over a longer period. For example, from 2006 to 2021, the Indigenous population grew by 56.8%, or nearly four times faster than the non-Indigenous population during the same period (+15.4%). The Métis population grew by 60.7%, the First Nations population grew by 54.3% and the Inuit population grew by 40.1%.

Comparisons with past census numbers

The success of the 2021 Census would not have been possible without the involvement of Indigenous people. Thanks to their participation, high-quality data are available for Indigenous communities across the country. Statistics Canada would like to thank First Nations, Métis and Inuit communities for responding to the 2021 Census of Population.

The 2021 Census was uniquely challenging to conduct during the COVID-19 pandemic. Ensuring the health and safety of First Nations, Métis and Inuit communities was highly prioritized, and at times this presented challenges for in-person collection. In particular, this impacted data collection for some First Nations communities.

As part of a nation-to-nation relationship, Statistics Canada engages with First Nations through Indigenous Liaison Advisors, who request the permission of First Nations chiefs and council members to collect data on reserve. In situations where there were complications related to COVID-19 or regional forest fires, or if a given First Nation did not give permission, data collection could not be completed.

The spring of 2021 also marked the tragic confirmation of the unmarked graves of children who had attended the Kamloops Indian Residential School in British Columbia. In later months, similar grave sites were also documented in Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Alberta and British Columbia. In response, the Indigenous Liaison Program at Statistics Canada worked closely with First Nations and census collection was paused in several First Nations communities and, in some cases, halted entirely.

In general, the number of incompletely enumerated reserves and settlements has declined steadily over the past few decades. In 1996, 77 reserves and settlements were incompletely enumerated during the census. This fell to 30 in 2001 and then to 22 in 2006, before rising to 31 in 2011. There were 14 in 2016. Because of the aforementioned difficulties surrounding collection in 2021, there were 63 incompletely enumerated reserves and settlements out of a total of 1,026 census subdivisions in Canada that were classified as "on reserve."

Because of changes in the number of incompletely enumerated reserves and settlements over time, caution should be used when comparing 2021 Census data on Indigenous peoples with data from earlier iterations of the census—particularly for First Nations people living on reserve. Calculations of population growth within this document are conducted by adjusting for incompletely enumerated reserves and settlements.

For more information on incompletely enumerated reserves and settlements, see Appendix 1.5 – Incompletely enumerated reserves and settlements in the Guide to the Census of Population, 2021.

Over half of First Nations people live in Western Canada

The 2021 Census counted 1,048,405 First Nations people living in Canada, marking the first time that the First Nations population surpassed the 1 million mark in a census.

While more than half (55.5%) of all First Nations people lived in Western Canada, Ontario had the largest number of First Nations people provincially (251,030), making up nearly one-quarter (23.9%) of the First Nations population in Canada. Meanwhile, one in nine First Nations people (11.1%) lived in Quebec, and 7.6% lived in Atlantic Canada. The remaining 1.9% of First Nations people lived in the territories.

In 2021, almost three-quarters (71.8%) of First Nations people had Registered or Treaty Indian status under the Indian Act, while 28.2% did not. The share of First Nations people with Registered or Treaty Indian status was higher in 2016 (76.2%), reflecting the fact that the First Nations population who did not have Registered or Treaty Indian status grew at a much faster pace in 2021 than the population with Registered or Treaty Indian status (+27.2% versus +4.1%).

Among status First Nations people, just over two-fifths (40.6%) lived on reserve in 2021. The term "on reserve" refers to census subdivisions legally affiliated with First Nations or Indian bands. However, while this definition applies to some First Nations that have signed a modern treaty or a self-government agreement, it does not apply to all. For example, most First Nations in the Northwest Territories and Yukon have signed modern treaties, but their administered lands are not considered on reserve.

New questions added to 2021 Census

Two new questions were added to the long-form census questionnaire in 2021, following engagement with Indigenous communities and organizations and extensive questionnaire testing. These new questions will help Métis and Inuit governments and organizations better understand the demographic, social and economic characteristics of their members.

The first question asked respondents who identified themselves or another member of their household as an Indigenous person, "Is this person a registered member of a Métis organization or Settlement?". For more information on Métis in Canada, see the Census in Brief article "Membership in a Métis organization or Settlement: Findings from the 2021 Census of Population".

The second question asked respondents who identified themselves or another member of their household as an Indigenous person, "Is this person enrolled under, or a beneficiary of, an Inuit land claims agreement?".

Métis population in Canada grows at much slower pace in 2021, compared with five years earlier

The census counted 624,220 Métis living in Canada in 2021, up 6.3% from 2016. While the growth of the Métis population outpaced that of the non-Indigenous population over the same period (+5.3%), the difference was not as great as in years past. From 2011 to 2016, the population identifying as Métis grew by almost one-third (+30.0%).

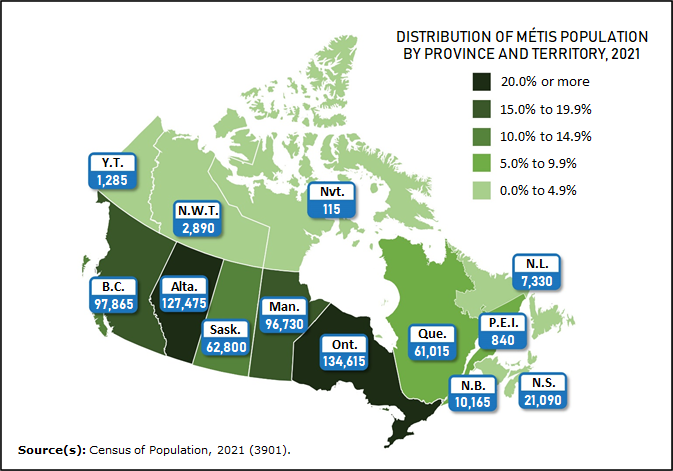

In 2021, over four in five Métis (83.2%) lived in either Ontario or Western Canada. Ontario had the largest Métis population (134,615), followed by Alberta (127,470).

Following engagement with Métis organizations, governments and stakeholders, the 2021 Census of Population long-form questionnaire collected data on membership in a Métis organization or Settlement for the first time.

The census counted 224,655 people reporting membership in a Métis organization or Settlement, with four-fifths (79.8%) reporting being a member of one of the five signatories of the Canada-Métis Nation Accord (2017). For more information on Métis in Canada, see the Census in Brief article "Membership in a Métis organization or Settlement: Findings from the 2021 Census of Population".

The Métis Nation of Alberta had the largest membership reported among Métis organizations, at 45,350 in 2021, followed closely by the Manitoba Metis Federation, at 43,920, and then by the Métis Nation of Ontario (36,240), Métis Nation British Columbia (27,140) and Métis Nation—Saskatchewan (26,700).

Along with Métis organizations, there are eight Metis Settlements of Alberta that were established though the 1938 Métis Population Betterment Act of the Alberta Legislature. These communities, located across central and northern Alberta, are the only land base for Métis officially recognized by a provincial government. In 2021, 3,540 people reported being a member of one of the eight Metis Settlements of Alberta, with Kikino being the largest (710).

More than two-thirds of Inuit live in Inuit Nunangat, but Inuit population outside Inuit Nunangat growing quickly

The census counted 70,545 Inuit living in Canada in 2021, up 8.5% from five years earlier.

Inuit Nunangat—the homeland of Inuit in Canada—is composed of four regions. The westernmost is the Inuvialuit region, found in the north of Yukon and the Northwest Territories. Next to it is Nunavut, Canada's third territory, which was officially established in 1999. Nunavik—the second most populated region—is located along the western and northern coastline of Quebec. Finally, Nunatsiavut is found along the north coast of Labrador.

Over two-thirds (69.0%) of Inuit lived in Inuit Nunangat in 2021, down from 72.8% in 2016, reflecting the faster growth of the Inuit population living outside Inuit Nunangat (+23.6%).

Over two in five Inuit (30,865 people) were living in Nunavut in 2021, accounting for 43.7% of the total Inuit population in Canada. A further 12,595 Inuit were living in Nunavik, 3,145 in the Inuvialuit region and 2,095 in Nunatsiavut.

Just over four-fifths (80.6%) of Inuit in Canada reported that they were enrolled under or were a beneficiary of an Inuit land claims agreement. The largest group of claimants (33,310 people) was part of the Nunavut Land Claims Agreement, and most (88.4%) of this group lived within the territory of Nunavut. The next largest group (15,505 people) was the James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement, with 79.5% of this group living in Nunavik.

Where the census counts people

The census collects data from respondents based on their usual place of residence. In some cases, respondents will have more than one option to consider. For example, a person may spend part of the year in a community where they are a member and another part of the year attending university or receiving long-term medical treatment in a nearby city, where more education or treatment options are available. In these types of circumstances, determining the place of residence is up to the respondent. Only one location is counted to ensure that people are not counted more than once.

Coverage studies are conducted by Statistics Canada to assess how well the census counts the population. These studies evaluate the net impact of some people being missed and others being counted more than once by the census. In 2023, coverage estimates will be available for the Indigenous population, based on the 2021 Census.

For more information, see The place you call home and Guide to the Census of Population, 2021.

Indigenous population continues to grow in large urban centres

The first release from the 2021 Census revealed that nearly three in four Canadians lived in a large urban centre of at least 100,000 people, referred to as a census metropolitan area. In 2021, 801,045 Indigenous people lived in a large urban centre.

Indigenous people were more likely to live in a large city in 2021 than in 2016. Over this five-year period, the Indigenous population living in a large urban centre grew by 12.5%. Within the total Indigenous population, the share of Indigenous people living in a large urban centre rose from 43.1% to 44.3%.

In some cases, Indigenous people—particularly those who live in remote, northern settings—may live temporarily in a large urban centre to access medical care or for other reasons. However, the Census of Population counts people based on their usual place of residence. This can show differences between the overall population in an urban centre at any given time and the population on Census Day.

In 2021, Winnipeg had the largest Indigenous population at 102,080 people, followed by Edmonton (87,605) and Vancouver (63,345).

The Indigenous population grew most in Edmonton (+11,400, +15.0%), Montréal (+11,265, +32.4%) and Winnipeg (+8,750, +9.4%) from 2016 to 2021. While the Indigenous population grew in most large urban centres over the same period, it declined slightly in Toronto (-1,685, -3.6%).

In 2021, 420,885 First Nations people lived in a large urban centre, accounting for 40.1% of the total First Nations population. This figure was higher for First Nations people without Registered or Treaty Indian status (59.4%) than it was for status First Nations people (32.6%).

More than half (55.4%) of Métis lived in a large urban centre in 2021. Winnipeg had the largest Métis population in Canada, followed by Edmonton, Calgary and Vancouver. Combined, these four urban centres accounted for almost one-quarter (24.1%) of the total Métis population in Canada.

In 2021, 15.3% of Inuit lived in a large urban centre, up from 13.0% in 2016. There were three urban centres that had an Inuit population of more than 1,000 people: Ottawa–Gatineau (1,730), Edmonton (1,290) and Montréal (1,130).

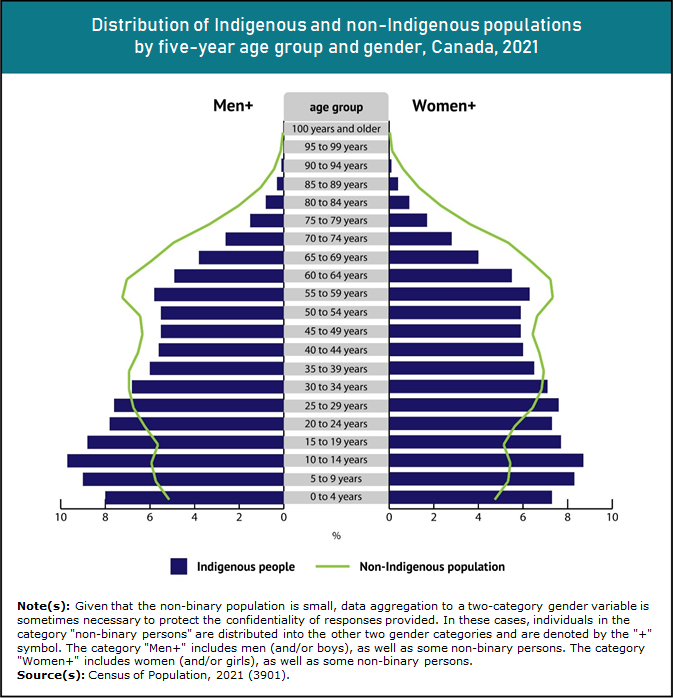

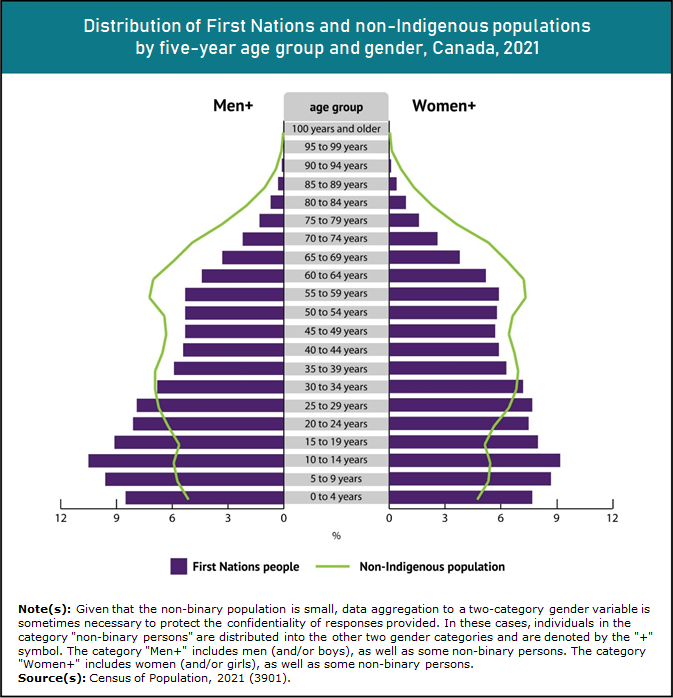

Nearly two-thirds of Indigenous people are working age

Continuing a trend observed in previous censuses, the 2021 Census showed that the Indigenous population is younger than the non-Indigenous population. The average age of Indigenous people was 33.6 years in 2021, compared with 41.8 years for the non-Indigenous population.

Inuit were the youngest of the three groups, with an average age of 28.9 years, followed by First Nations people (32.5 years) and Métis (35.9 years).

There were 459,215 Indigenous children aged 14 years and younger in 2021, accounting for one-quarter (25.4%) of the total Indigenous population. By comparison, 16.0% of the non-Indigenous population was 14 years of age and younger.

Just under two-thirds (65.1%) of Indigenous people were working age (15 to 64 years) in 2021. The 2021 Census release from April 27, 2022 on Canada's shifting demographic profile reported that the share of the working-age population near retirement was higher than at any point in the history of Canada. However, this was not the case among Indigenous people.

While the shares of Indigenous people and the non-Indigenous population aged 15 to 64 years were similar (65.1% versus 65.4%) in 2021, the share who were close to retirement age—55 to 64 years—was lower for the Indigenous population than for the non-Indigenous population. Just over one in six working-age Indigenous people (17.2%) were "close to retirement" age, compared with 22.0% for the non-Indigenous population. With a larger share of the non-Indigenous population nearing retirement age, future census data may see the Indigenous population accounting for a larger share of the labour force.

Despite the relative youth of Indigenous people, the share of Indigenous people aged 65 years and older continues to grow—as with the total population. From 2016 to 2021, the share of Indigenous people aged 65 years and older rose from 7.3% to 9.5%.

Gender diversity among Indigenous peoples

Following an extensive engagement process across Canada (The 2021 Census of Population Consultation Results: What we heard from Canadians), the Census of Population added new content on gender.

For many people, gender corresponds to their sex at birth (cisgender men and cisgender women). For some, these do not align (transgender men and transgender women) or their gender is not exclusively "man" or "woman" (non-binary people). Within many Indigenous communities and cultures, there has been a long-held acceptance of gender diversity—often reflected within the term, "Two-Spirit."

Most of the 1,348,040 Indigenous people in Canada aged 15 and older were either cisgender men (47.4%) or cisgender women (51.9%), meaning that their sex at birth corresponds to their gender as reported on the census questionnaire. Another 4,180 Indigenous people were transgender, with 43.7% of this group being transgender men and 56.3% being transgender women. The remaining 4,455 Indigenous people aged 15 and older were non-binary.

Indigenous people aged 15 and older were twice as likely to be transgender or non-binary as non-Indigenous people (0.6% versus 0.3%). This difference is partly a reflection of the younger average age of Indigenous people, as younger people were also more likely to be transgender or non-binary than older people. However, even among those aged 15 to 24, Indigenous people were more likely to be transgender or non-binary than non-Indigenous people (1.3% versus 0.8%).

For more information and analysis on gender diversity in Canada, see The Daily article "Canada is the first country to provide census data on transgender and non-binary people".

Indigenous children more likely to live with grandparents in their home

Past iterations of the census have noted the diverse family characteristics of Indigenous peoples, with many living in multigenerational homes, alongside parents, grandparents and other relatives. Among the 459,210 Indigenous children aged 14 years of age and younger, a higher proportion lived with at least one grandparent in their home, compared with non-Indigenous children. For First Nations, Métis and Inuit families, grandparents often play an important role in raising children and passing down values, traditions and cultural knowledge to younger generations.

In 2021, 14.2% of Indigenous children lived with at least one grandparent, compared with 8.9% of non-Indigenous children. Among all Indigenous children who lived with their grandparents, most (78.0%) lived in a multi-generational home, where at least one parent and at least one grandparent were present. The remaining 22.0% lived in a skip-generation family with at least one grandparent, but no parents present. This reflected previous findings from the 2021 Census on the living arrangements of people in Canada.

The majority (56.0%) of Indigenous children lived in a two-parent household in 2021.

More than one-third (35.8%) of Indigenous children lived in a lone-parent household. Most (79.5%) lived with their mother, while the remainder lived with their father.

In 2020, the Government of Canada instituted the Act respecting First Nations, Inuit and Métis children, youth and families. This legislation sought to reduce the overrepresentation of Indigenous children and youth in foster care and to improve child and family services. Of children in private households in 2021, Indigenous children were more likely to be in foster care than non-Indigenous children (3.2% versus 0.2%).

Altogether, Indigenous children accounted for over half (53.8%) of all children in foster care, while nationally, Indigenous children accounted for 7.7% of all children 14 years of age and younger. In 2021, the share of Indigenous children in foster care was essentially unchanged from five years earlier.

Share of Indigenous people living in dwellings that were crowded and dwellings in need of major repairs down since 2016, but remains higher than that of non-Indigenous population

Because of a number of barriers faced by Indigenous communities, inadequate housing conditions are a significant issue among Indigenous people in Canada. Indigenous people are more likely to live in remote or northern communities, where high costs and limited access to building materials and supplies contribute to the challenges of building or maintaining homes. In addition, for on-reserve First Nations communities, accessing financing to buy, build or renovate housing can be difficult because of the application of the Indian Act, which does not permit the use of property on reserves as collateral in a lending agreement.

Almost one in six Indigenous people (16.4%) lived in a dwelling that was in need of major repairs in 2021, a rate almost three times higher than for the non-Indigenous population (5.7%). Métis were the least likely among Indigenous people to live in a dwelling that was in need of major repairs (10.0%), followed by First Nations people (19.7%) and Inuit (26.2%).

Over one-third of First Nations people with Registered or Treaty Indian status (37.4%) living on reserve occupied a dwelling in need of major repairs in 2021, compared with 12.7% of those living off reserve. A similar pattern was apparent among Inuit, with those living in Inuit Nunangat almost three times more likely to live in a dwelling in need of major repairs than Inuit living outside Inuit Nunangat (32.7% versus 11.5%).

Despite overall higher shares of Indigenous people living in a dwelling that needed major repairs, the share of Indigenous people living in such a dwelling fell 2.7 percentage points from 2016 to 2021. The share declined for First Nations people (-3.9 percentage points) and Métis (-1.2 percentage points); however, the share for Inuit in 2021 was roughly the same as it had been five years prior. The gap between the share of Indigenous people and non-Indigenous people living in a dwelling in need of major repairs also decreased from 13.0 percentage points in 2016 to 10.7 percentage points in 2021.

In 2021, 17.1% of Indigenous people lived in crowded housing—housing considered not suitable for the number of people who lived there according to the National Occupancy Standard. By comparison, 9.4% of the non-Indigenous population lived in crowded housing. Inuit were the most likely to live in crowded housing in 2021 (40.1%), followed by First Nations people (21.4%) and Métis (7.9%).

First Nations people with Registered or Treaty Indian status living on reserve were almost twice as likely to live in crowded housing, compared with those who lived off reserve (35.7% versus 18.4%). The share of Inuit living in crowed housing was mainly driven by those living in Inuit Nunangat, who were more than four times as likely to live in crowded housing as Inuit living outside Inuit Nunangat (52.9% versus 11.4%).

While Indigenous people were more likely to live in crowded housing compared with the non-Indigenous population, the gap between the two groups narrowed from 9.5 percentage points in 2016 to 7.8 percentage points in 2021.

For more information on the housing conditions of Indigenous people in Canada, see the Census in Brief article "Housing conditions among First Nations people, Métis and Inuit in Canada from the 2021 Census."

Indigenous people much more likely to live in low-income household than non-Indigenous population

The 2021 Census marked the first time that low-income data were made available for all geographic regions in Canada, including reserves and northern areas. Of the 1.8 million Indigenous people living in Canada in 2021, 18.8% lived in a low-income household, as defined using the low-income measure, after tax, compared with 10.7% of the non-Indigenous population.

The share of Indigenous people living in a low-income household was much lower in 2021 than in 2016 (18.8% versus 28.1%). As the results from the census release on income have shown, this downward trend in low income has been observed across Canada and was largely driven by government transfers in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. The pandemic saw governments across Canada implementing restrictions on businesses, schools, universities and colleges to slow the spread of COVID-19, resulting in precarious work situations for millions of Canadians. To alleviate financial hardships related to the pandemic, the federal government created a number of relief programs, such as the Canada Emergency Response Benefit, the Canada Recovery Caregiving Benefit, and the Canada Emergency Student Benefit.

Among the three Indigenous groups, the low-income rate was highest among First Nations people (22.7%). It was particularly high among status First Nations people living on reserve, almost one in three (31.4%) of whom lived in a low-income household.

One in six Inuit (16.6%) and one in eight Métis (12.8%) lived in a low-income household. The share of Inuit living in a low-income household was similar for those living in Inuit Nunangat (16.5%) and those living outside Inuit Nunangat (16.8%). However, these figures do not take into account the relative costs of goods and housing in Inuit Nunangat, which are significantly higher than the national average.

Nearly one-quarter (24.6%) of Indigenous children aged 14 years and younger lived in a low-income household in 2021, more than double the rate among non-Indigenous children (11.1%).

Fewer Indigenous people report an Indigenous language as their mother tongue, while more are learning an Indigenous language as a second language

Over 70 Indigenous languages were reported in the 2021 Census, with 237,420 Indigenous people reporting that they could speak an Indigenous language well enough to conduct a conversation.

In 2019, the Indigenous Languages Act was signed into law to "support and promote the use of Indigenous languages." Following this legislative step, the Office of the Commissioner of Indigenous Languages was established with a mandate to support the efforts of Indigenous peoples to reclaim, revitalize, maintain and strengthen Indigenous languages.

While the work to revitalize Indigenous languages reflects their importance to Indigenous peoples, it also reflects the reality that many languages, which had at one time flourished, have become endangered. A number of Indigenous languages had fewer than 1,000 speakers. For example, Wolastoqewi (Malecite) the traditional language of many First Nations people in Atlantic Canada was spoken by 795 Indigenous people in 2021. Similarly, Gwich'in, in the Athabaskan language family, was spoken by 275 Indigenous people.

There are also Indigenous languages with smaller numbers of speakers that are "isolates", meaning that they cannot be categorized into a larger family of languages. These include Michif (1,845 speakers), which is the language of the Métis Nation, and Haida (220 speakers) and Ktunaxa (Kutenai) (210 speakers), both of which are spoken by First Nations people in British Columbia.

The most commonly spoken Indigenous languages among Indigenous people were Cree languages, with 86,480 speakers. While the most commonly reported version of Cree was "Cree" with no other specification (60,160 speakers), Cree languages can be further broken down into a number of different dialects, such as Nehiyawewin (Plains Cree) (11,730 speakers), Nihithawiwin (Woods Cree) (5,015 speakers), Iyiyiw-Ayimiwin (Northern East Cree) (4,785 speakers), Nehinawewin (Swampy Cree) (4,580 speakers), Inu Ayimun (Southern East Cree) (890 speakers) and Ililimowin (Moose Cree) (400 speakers).

Among First Nations people, the most common Indigenous languages spoken were Cree languages (80,175 speakers), Ojibway languages (24,255 speakers) and Oji-Cree (15,110 speakers).

The most common Indigenous languages among Métis were Cree languages (4,650 speakers), Michif (1,485 speakers) and Dene (1,035 speakers).

Collectively, the Indigenous languages spoken by Inuit are known as Inuktut. Inuktitut was the second largest Indigenous language in Canada, spoken by 39,620 Inuit. Other Inuktut dialects spoken by Inuit include Inuinnaqtun (735 speakers) and Inuvialuktun (330 speakers).

From 2016 to 2021, the number of Indigenous people who reported that they could speak an Indigenous language well enough to conduct a conversation declined by 4.3%. This was largely driven by declines in the number of Indigenous people with an Indigenous mother tongue—that is, the first language learned in childhood that was still understood—as this share fell by 8.1% over the period. However, the number of Indigenous people who could speak an Indigenous language but did not have an Indigenous mother tongue grew by 7.0% over the same period. This change reflects a growing share of Indigenous people who are learning an Indigenous language as a second language.

The majority (72.3%) of Indigenous people who could speak an Indigenous language reported that they had an Indigenous language as their mother tongue. This was a slightly lower share than in 2016, when just over three-quarters (75.3%) of Indigenous people who could speak an Indigenous language also had an Indigenous mother tongue.

Looking ahead

In the coming months, additional releases from the 2021 Census will reveal more details about First Nations people, Métis and Inuit in Canada, including information on education and labour force characteristics.

Note to readers

Canadians are invited to download the StatsCAN app to view the census results.

Definitions, concepts and geography

The population growth rates presented in this document were calculated by the difference in population size between two dates (e.g., between two censuses), then dividing that difference by the population of the earlier date. Rates are expressed as percentages. A further step is taken to adjust for incompletely enumerated reserves and settlements, where data were not collected in either of the two census cycles.

All data and findings presented in this document are based on the 2021 geographic boundaries.

For detailed definitions of census metropolitan areas, please refer to the Census Dictionary.

Beginning in 2021, the census asked questions about both the sex at birth and the gender of individuals. While data about sex at birth are needed to measure certain indicators, for the purposes of this release, gender (as opposed to sex) is the standard variable used in concepts and classifications. For more details on the new gender concept, see Age, Sex at Birth and Gender Reference Guide, Census of Population, 2021.

Given that the non-binary population is small, data aggregation to a two-category gender variable is sometimes necessary to protect the confidentiality of responses provided. In these cases, individuals in the category "non-binary persons" are distributed into the other two gender categories. Unless otherwise indicated in the text, the category "men" includes men (and/or boys), as well as some non-binary persons. The category "women" includes women (and/or girls), as well as some non-binary persons.

A fact sheet on gender concepts, Filling the gaps: Information on gender in the 2021 Census, is also available.

2021 Census of Population products and releases

Today, Statistics Canada is releasing a fifth set of results from the 2021 Census of Population.

Several 2021 Census products are available as of today on the 2021 Census Program web module. This module has been designed to provide easy access to census data, free of charge.

The analytical products include an article in The Daily, two Census in Brief articles and an infographic.

The data products include results on First Nations people, Métis and Inuit, for many standardized geographic regions, and are available through the Census Profile, and data tables.

The Focus on Geography Series provides data and highlights on key topics in this Daily release at various levels of geography.

Reference materials are designed to help users make the most of census data. These include the Guide to the Census of Population, 2021, the Dictionary, Census of Population, 2021, the 2021 Census of Population questionnaires, and the 2021 Census Data Quality Guidelines. The Indigenous Peoples Reference Guide is also available. The dictionary, reference guides and data quality guidelines are updated based on new information throughout the release cycle.

Geographic products and services related to the 2021 Census Program can be found under Census geography. This includes GeoSearch, an interactive mapping tool, Focus on Geography, and the Census Program Data Viewer, which are data visualization tools.

Videos on census concepts can also be viewed in the Census learning centre.

An infographic, First Nations people, Métis and Inuit in Canada, is also available.

Over the coming months, Statistics Canada will continue to release results from the 2021 Census of Population and provide an even more comprehensive picture of the Canadian population. Please see the 2021 Census release schedule to find out when data and analysis on the different topics will be released throughout 2022.

Contact information

For more information, or to enquire about the concepts, methods or data quality of this release, contact us (toll-free 1-800-263-1136; 514-283-8300; infostats@statcan.gc.ca) or Media Relations (statcan.mediahotline-ligneinfomedias.statcan@statcan.gc.ca).

- Date modified: