While English and French are still the main languages spoken in Canada, the country's linguistic diversity continues to grow

Archived Content

Information identified as archived is provided for reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It is not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards and has not been altered or updated since it was archived. Please "contact us" to request a format other than those available.

Released: 2022-08-17

Despite the impact that the COVID-19 pandemic has had on arrivals to the country, immigration has continued to enrich Canada's linguistic diversity.

English and French remain by far the most commonly spoken languages in Canada. More than 9 in 10 Canadians speak one of the two official languages at home at least on a regular basis.

The 2021 Census also found that 4.6 million Canadians speak predominantly a language other than English or French at home (in other words, they speak this language most often at home, without speaking other languages equally often; see the box "Languages known and spoken: Understanding the concepts"). These individuals represent 12.7% of the Canadian population, a proportion that has been increasing for 30 years. By comparison, the proportion was 7.7% in 1991, when immigration levels were rising.

In addition, one in four Canadians in 2021—or 9 million people—had a mother tongue other than English or French. This is a record high since the 1901 Census, when a question on mother tongue was first added.

Canada has a rich linguistic diversity. The languages known and spoken here are closely linked to the identity and culture of Canadians and to their relationship with their community. Languages are an integral part of the everyday lives of Canadians—be it in early childhood, at home, at school or at work—and extend beyond the country's borders into broader cultural and historical contexts. For example, in 2022, the Observatoire démographique et statistique de l'espace francophone (link is in French only) estimated that 321 million people around the world spoke French, with half living in Africa.

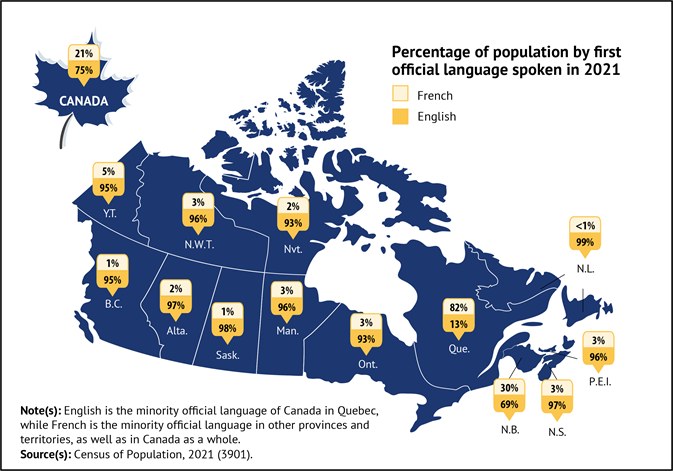

The vast majority of the Canadian population commonly uses English and French, Canada's official languages, to communicate and access services. Although both are spoken throughout the country, English is a minority language in Quebec, while French is a minority language in the other provinces and territories, as well as in Canada as a whole.

Indigenous languages existed long before Canada was formed. As the International Decade of Indigenous Languages kicks off, the preservation, vitality and growth of the more than 70 distinct Indigenous languages spoken in the country remain as relevant and important as ever.

Today, Statistics Canada is releasing a fourth set of 2021 Census results, on mother tongue, languages spoken at home and languages known by Canadians.

Census data on languages are essential to understanding how Canada's linguistic profile has changed, as well as for developing and improving programs and services for all Canadians. They are also used in the development, application and administration of various federal and provincial laws, such as the federal Official Languages Act and Indigenous Languages Act, New Brunswick's Official Languages Act, Ontario's French Language Services Act and Quebec's Charter of the French Language.

Highlights

English is the first official language spoken by just over three in four Canadians. This proportion increased from 74.8% in 2016 to 75.5% in 2021.

French is the first official language spoken by an increasing number of Canadians, but the proportion fell from 22.2% in 2016 to 21.4% in 2021.

From 2016 to 2021, the number of Canadians who spoke predominantly French at home rose in Quebec, British Columbia and Yukon, but decreased in the other provinces and territories.

The proportion of Canadians who spoke predominantly French at home decreased in all the provinces and territories, except Yukon.

For the first time in the census, the number of people in Quebec whose first official language spoken is English topped 1 million and their proportion of the population rose from 12.0% in 2016 to 13.0% in 2021. Moreover, 7 in 10 English speakers lived on Montréal Island or in Montérégie.

The proportion of bilingual English-French Canadians (18.0%) remained virtually unchanged from 2016. From 2016 to 2021, the increase in the bilingualism rate in Quebec (from 44.5% to 46.4%) offset the decrease observed outside Quebec (from 9.8% to 9.5%).

In Canada, 4 in 10 people could conduct a conversation in more than one language. This proportion rose from 39.0% in 2016 to 41.2% in 2021. In addition, 1 in 11 could speak three or more languages.

In 2021, one in four Canadians had at least one mother tongue other than English or French, and one in eight Canadians spoke predominantly a language other than English or French at home—both the highest proportions on record.

The number of Canadians who spoke predominantly a South Asian language such as Gujarati, Punjabi, Hindi or Malayalam at home grew significantly from 2016 to 2021, an increase fuelled by immigration. In fact, the growth rate of the population speaking one of these languages was at least eight times larger than that of the overall Canadian population during this period.

In contrast, there was a decline in the number of Canadians who spoke predominantly certain European languages at home, such as Italian, Polish and Greek.

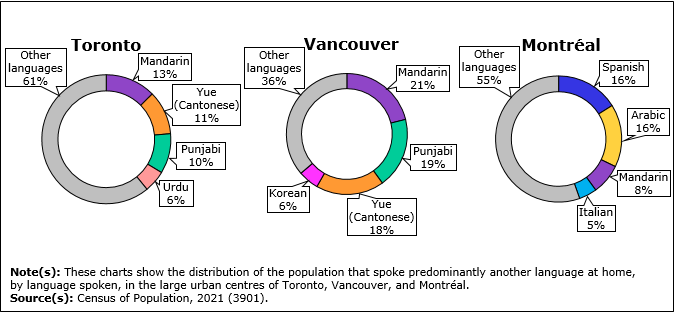

Aside from English and French, Mandarin and Punjabi were the country's most widely spoken languages. In 2021, more than half a million Canadians spoke predominantly Mandarin at home and more than half a million spoke Punjabi.

Among Canadians whose mother tongue is neither English nor French, 7 in 10 spoke an official language at home at least on a regular basis.

In 2021, 189,000 people reported having at least one Indigenous mother tongue and 183,000 reported speaking an Indigenous language at home at least on a regular basis. Cree languages and Inuktitut are the main Indigenous languages spoken in Canada.

Among individuals with an Indigenous mother tongue, four out of five spoke that language at home at least on a regular basis, and half spoke it predominantly.

Languages known and spoken: Understanding the concepts

Information on the mother tongue of Canadians, the languages they know and the languages they speak at home reveals a variety of linguistic contexts. Some contexts are simpler, such as Canadians who know only one language, while others are more complex (for example, Canadians who speak more than one language at home or have more than one mother tongue). The Census of Population concepts shed light on these different contexts.

Languages known

Canadians report knowing a language when they feel they can conduct a conversation in that language. Canadians who can have a conversation in two languages are bilingual and those who can have a conversation in three languages are trilingual.

Mother tongues

Canadians report a language as their mother tongue when they learned it in childhood and still understand it.

In 2021, 96.0% of Canadians reported only one mother tongue and 4.0% reported two or more mother tongues, meaning that they learned these languages at the same time in childhood. The number and proportion of people who reported having more than one mother tongue has been on the rise since 2006.

In this release, unless otherwise stated, we refer to the number of people with only one mother tongue. When referring to all individuals with a given mother tongue—i.e., Canadians who reported that mother tongue alone or together with one or more other mother tongues—we specify that this is the number of people who reported that mother tongue "alone or with another language."

Languages spoken at home

In this release, the number of Canadians who speak a language at home "at least on a regular basis" corresponds to the total number of people who reported speaking that language at home, either on a regular basis or most often, alone or with other languages. In 2021, more than four in five Canadians (81.3%) spoke only one language at home at least on a regular basis, while 18.7% spoke more than one language at home at least on a regular basis.

The number of Canadians who speak a language "predominantly" at home corresponds to the number of people who speak only one language most often at home. Therefore, this number includes those who speak only one language at least on a regular basis at home and those who, even if they speak more than one language at home, identified one—and only one—language spoken most often at home. Some people don't speak any language predominantly at home; these are people who report speaking more than one language most often, that is to say, equally (4.3% of the population).

First official language spoken

The first official language spoken refers to the first official language between English and French spoken by Canadians. It is determined from the knowledge of languages, mother tongue and language spoken most often at home. More information on this concept is available in the reference document "First official language spoken of person."

In this release, unless otherwise stated, we refer to the number of people whose first official language spoken is only English or only French. The number of Canadians whose first official language spoken is both English and French (476,000 people, representing 1.3% of the population) was not distributed between English and French. Moreover, 673,000 Canadians (1.8% of the population) did not have a first official language spoken.

For more information

For more information on the processing and interpretation of multiple responses to census language questions, please refer to the guide "Interpreting and presenting census language data." Videos on language concepts in the census are also available.

The proportion of Canadians with English as their first official language spoken rises, while those with French decreases

The vast majority of Canadians know and speak at least one of Canada's two official languages. In 2021, 98.1% of the Canadian population could have a conversation in English or French, and 92.9% spoke one of these languages at home at least on a regular basis.

Of the two official languages, most Canadians spoke English at home at least on a regular basis (74.2%) or predominantly (63.8%), and English was the mother tongue of more than half of the country's population (54.9%). From 2016 to 2021, the number of Canadians with English as their first official language spoken rose from 26.0 million to 27.6 million. The proportion they represent also increased during this period, from 74.8% to 75.5%.

In fact, the number and proportion of Canadians with English as their first official language spoken have been rising since 1971, the first year the census collected information on first official language spoken.

As in the past, immigration contributed to this trend, given that most immigrants turn to using English after they arrive in Canada. For example, in 2021, 80.6% of Canadians with a mother tongue other than English or French (referred to as "non-official languages" hereinafter) had English as their first official language spoken, compared with 6.1% who had French. Canadians with a non-official mother tongue include a significant proportion of immigrants.

French was the first official language spoken by more than 7.8 million Canadians in 2021, up from 7.7 million in 2016. However, since this growth (+1.6%) was slower than the growth of the population overall (+5.2%), the proportion of the Canadian population whose first official language spoken is French decreased from 22.2% in 2016 to 21.4% in 2021, continuing the downward trend seen in recent decades. In 1971, French was the first official language spoken by 27.2% of Canadians.

Most indicators of the evolution of French in Canada follow this same trend, where the absolute numbers increase whereas the percentage of the population decreases. This is because the number of speakers of languages other than French increases faster in proportion.

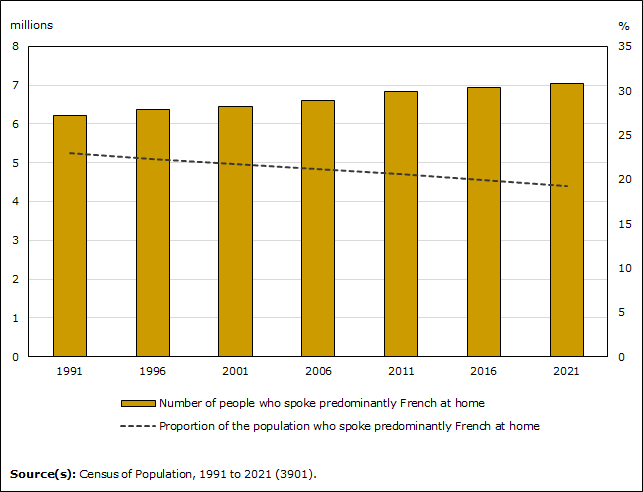

In 2021, more than one in five Canadians (22.6%) spoke French at home at least on a regular basis. In addition, from 2016 to 2021, the number of Canadians who spoke predominantly French at home rose from 6.9 million to 7.0 million, but their proportion in the population fell from 20.0% to 19.2%. Similarly, the number of Canadians whose mother tongue was French rose slightly (from 7,167,000 to 7,189,000), but their proportion in the population decreased (from 20.6% to 19.6%). This was also observed for the number of people who could have a conversation in French, reaching 10.7 million in 2021, continuing the decrease in proportion that began in 1981. Back then, 31.8% of Canadians could have a conversation in French, compared with 29.1% in 2021.

In Quebec, the proportion of the population who speak predominantly French at home has been decreasing since 2001

Echoing the situation at the national level, the number of French speakers in Quebec is increasing, but their proportion in Quebec's population is decreasing.

In 2021, 85.5% of the Quebec population reported speaking French at home at least on a regular basis. The number of people who spoke predominantly French at home increased from 6.4 million in 2016 to 6.5 million in 2021, but their proportion in the population fell from 79.0% to 77.5%. Meanwhile, the proportion of the Quebec population who spoke French most often at home equally with another language rose slightly from 2016 (3.3%) to 2021 (3.5%).

Furthermore, while the number of people in Quebec with French as their mother tongue rose from 2016 to 2021, their proportion in Quebec's population decreased from 77.1% to 74.8%. Increasing numbers and declining proportions were also observed for people in Quebec with French as their first official language spoken (down from 83.7% to 82.2%) or who could have a conversation in French (down from 94.5% to 93.7%).

In most of Quebec's 17 regions, French remained the first official language spoken by more than 90% of the population (for instance, 91.3% in the Laurentides, 97.9% in Mauricie, 99.1% in Bas-Saint-Laurent). However, the situation was different in Montérégie (84.6%), in Outaouais (77.1%), in Laval (68.9%), on Montréal Island (58.4%) and in Nord-du-Québec (31.1%).

From 2016 to 2021, the proportion of the population with French as their first official language spoken decreased in all regions of Quebec, except in Gaspésie–Îles-de-la-Madeleine (+1.1 percentage points). The largest declines were observed in Nord-du-Québec (-3.6 percentage points), in Laval (-3.0 percentage points), in Outaouais (-2.4 percentage points) and on Montréal Island (-2.4 percentage points).

Outside Quebec and the territories, the number of Canadians with French as their only first official language spoken is decreasing in all provinces, except British Columbia

In its Action Plan for Official Languages – 2018-2023: Investing in Our Future, the Government of Canada stressed the importance of the vitality of official language minority communities in the country's social fabric, while recognizing a decline in the percentage of French-speaking people in Canada outside Quebec.

In Canada outside Quebec, French remained the second most common language in 2021, after English. More than 2.7 million people (or 1 in 10) could have a conversation in French in Canada outside Quebec.

In addition, in Canada outside Quebec, nearly 1.1 million people spoke French at home at least on a regular basis, including more than half a million (532,000) who spoke predominantly French. However, since 2016, the number of people who spoke predominantly French at home outside Quebec fell by 36,000.

The number of people whose only mother tongue was French also decreased outside Quebec from 2016 to 2021 (-49,000), continuing the trend observed from 2011 to 2016.

However, accounting for an increasing number of people who learned French at the same time as another language in their childhood (English most of the time), the trend differs. Instead, from 2016 to 2021, the number of people who had French as their mother tongue, alone or with another language, rose by 36,000 to 1.1 million.

The number of residents of Canada outside Quebec who had French as their exclusive first official language spoken (not including those who had both English and French as their first official languages spoken; see the box "Languages known and spoken: Understanding the concepts") has decreased by 36,000 since 2016, but has continued to top 900,000. This decline—the first since the period from 1991 to 1996—was observed in all the provinces, except British Columbia (+1,200). In the territories, the number of speakers was fairly stable, except in Yukon where it grew (+200). Moreover, the proportion of Canadians living outside Quebec whose first official language spoken is French was down from 3.6% in 2016 to 3.3% in 2021.

This decrease is attributable to a combination of factors, such as an older population on average (generally speaking, there are more deaths in an older population), incomplete transmission of French from one generation to the next, and linguistic transfers (when a person speaks a language at home that is different from their mother tongue). Also, the effect of interprovincial and international migration on these figures varies depending on the period and the region.

In Canada outside Quebec, more than half of the population whose first official language spoken is French lived in Ontario and one-quarter lived in New Brunswick. In 2021, French was the first official language spoken by 30.0% of New Brunswick's population, by 4.5% of Yukon's population and by 3.4% of Ontario's population.

In many municipalities in Canada outside Quebec, a large proportion of the population had French as their first official language spoken. For example, more than one-third of the population of Wellington (Fire District), Prince Edward Island (42%), Clare, Nova Scotia (56%), Paquetville (Parish), New Brunswick (98%), Hearst, Ontario (86%), St-Pierre-Jolys, Manitoba (40%), and Falher, Alberta (41%) had French as their first official language spoken.

French was also the first official language spoken by a significant proportion of the population in many large urban centres (also known as census metropolitan areas) outside Quebec, such as Moncton (32.6%), Greater Sudbury (22.7%) and Ottawa (14.9%) (see the Note to readers for more information about Ottawa). However, in these three centres, the proportion of individuals whose first official language spoken is French decreased from 2016 to 2021 (-2.2 percentage points in Moncton, -2.9 percentage points in Greater Sudbury, and -1.1 percentage points in Ottawa).

In Quebec, 1 in 10 people speak predominantly English at home

English is one of Canada's official languages, but in Quebec, it is a minority language. From 2016 to 2021, the proportion of Quebec's population whose sole mother tongue is English was relatively stable (from 7.5% in 2016 to 7.6% in 2021), but the number of speakers rose (+38,000) to 639,000. Accounting for all Quebeckers who have English as their sole mother tongue or together with another language, the gain is much bigger (+125,000). This is driven by an increase in the number of individuals who reported both English and French as their mother tongues.

Almost one in five people in Quebec (19.2%) spoke English at home at least on a regular basis, more than half of whom spoke it along with French, another language, or French and another language. The number of people who spoke predominantly English at home (874,000 in 2021) accounted for 10.4% of the Quebec population, up from 9.7% in 2016. The demographic weight of those who spoke English most often at home equally with another language also grew (from 2.3% in 2016 to 2.8% in 2021).

Furthermore, the proportion of people whose first official language spoken is English rose from 12.0% in 2016 to 13.0% in 2021, at about the same level as in 1981. For the first time since comparable data have been compiled, the number of people in Quebec with English as the first official language spoken topped the 1 million mark in 2021.

A number of factors explain the increase in the relative proportion of English speakers in Quebec, including the English-speaking population being younger on average (and therefore having proportionally fewer deaths) and specific recent migration trends. Other data sources indicate that the number of non-permanent residents has risen considerably in Quebec since 2016 and that the province's net interprovincial migration—though still in a deficit—improved over the recent period. Historically, English-speaking populations are overrepresented in Quebec's interprovincial migratory movements.

Those with English as their first official language spoken were concentrated in certain areas of the province. For example, more than 7 in 10 speakers (71.7%) lived on Montréal Island or in Montérégie.

The demographic weight of those with English as their first official language spoken was highest in the regions of Nord-du-Québec (54.4%), Montréal Island (30.6%), Outaouais (19.1%) and Laval (19.0%). These regions also saw this population's demographic weight increase the most from 2016 to 2021 (+7.8 percentage points in Nord-du-Québec, +2.2 percentage points on Montréal Island, +1.7 percentage points in Laval and +1.7 percentage points in Outaouais). In contrast, English was the first official language spoken by less than 1% of the population of the regions of Saguenay–Lac-Saint-Jean (0.7%) and Bas-Saint-Laurent (0.7%).

Finally, in 2021, more than one in two people in Quebec could have a conversation in English. This is the first time this level has been observed since the 1901 Census, when information on the knowledge of official languages began being collected. In 2021, the vast majority of these individuals could also conduct a conversation in French.

The English-French bilingualism rate is up in Quebec, but down in Canada outside Quebec

Among the different types of multilingualism that exist, the ability to have a conversation in English and French is of particular interest, especially given that the dynamics of Canada's two official languages are the focus of many policies and programs.

In 2021, the English-French bilingualism rate in Canada was 18.0%. This rate was relatively stable compared with its previous peak in 2016 (17.9%).

This relative stability stems from two divergent trends: the rate of English-French bilingualism rising in Quebec, but decreasing outside Quebec.

In Quebec, the proportion of bilingual English-French individuals rose from 44.5% in 2016 to 46.4% in 2021. Except for a dip from 2001 to 2006, the rate of English-French bilingualism has been rising in Quebec in recent decades. It was at 25.5% in 1961.

Although the number of bilingual English-French individuals rose in Canada outside Quebec (+53,000) from 2016 to 2021, the English-French bilingualism rate decreased, falling from 9.8% to 9.5%. This is due to faster growth in the number of people who can conduct a conversation only in English, or in neither English nor French. The rate of English-French bilingualism peaked in Canada outside Quebec in 2001 (10.3%).

The concentration of bilingual English-French individuals in Quebec rose from 2016 to 2021. In 2021, nearly 6 in 10 bilingual English-French Canadians (59.2%) lived in Quebec, compared with 57.7% in 2016.

In New Brunswick, the only officially bilingual province in the country, the rate of English-French bilingualism remained fairly stable over this period (33.9% in 2016 and 34.0% in 2021).

The proportion of bilingual English-French Canadians was higher among those whose mother tongue was French. From 2016 to 2021, the rate of English-French bilingualism increased among Canadians with a French mother tongue (from 46.2% to 47.6%), and decreased slightly among those whose mother tongue is English (from 9.2% to 9.0%) or another language (from 11.7% to 11.5%).

The English-French bilingualism rate was also particularly high among Canadians whose mother tongue is an official language in a minority situation, that is, English in Quebec and French in Canada outside Quebec. Compared with 2016, the rate of English-French bilingualism was stable in 2021 among people with a French mother tongue in Canada outside Quebec, at 85.3%. Among English-mother-tongue individuals in Quebec, it decreased from 68.8% in 2016 to 67.1% in 2021.

Overall, more than 4 in 10 Canadians can have a conversation in more than one language

In addition to the language or languages learned in childhood and spoken at home, many Canadians can conduct a conversation in one, two or several other languages (either official or non-official languages). If we consider all languages, in 2021, 58.8% of Canadians could have a conversation in one language, 32.1% were bilingual, 7.6% were trilingual, and 1.5% could have a conversation in four or more languages.

In 2021, the proportion of Canadians who could conduct a conversation in more than one language (41.2%) was up from 2016 (39.0%).

By comparison, in the Europe of 28 (EU-28) in 2016, the European Commission reported that about one-third of adults aged 25 to 64 spoke two languages, and another one-third knew at least three languages. This varied greatly from one country to another. For example, one-third of the population 25 to 64 years of age in the United Kingdom spoke more than one language, compared with 6 in 10 people in France. In European countries with more than one official language, it is not uncommon for a high proportion of adults aged 25 to 64 to know three or more languages. In 2016, this was the case for more than 6 in 10 Belgians, Swiss or Finns.

In Canada in 2021, among the provinces and territories, Nunavut had the highest rate of bilingualism (68.0%), thanks to Inuktitut–English bilingualism, and Quebec had the highest rate of trilingualism (12.2%). In the large urban centre of Montréal, nearly one in five people were trilingual in 2021.

Montréal stood out in this regard, with 69.8% of its population capable of having a conversation in two or more languages. This is the highest proportion of all large urban centres in Canada, followed by Ottawa–Gatineau (60.0%) and Toronto (56.1%). Conversely, this proportion was lower in St. John's (13.5%), Belleville–Quinte West (14.6%) and Peterborough (15.0%).

Immigration drives up the number of Canadians who speak a language other than English or French at home, especially a South Asian language

The number of Canadians who speak certain languages other than English or French has grown significantly from 2016 to 2021. The number of Canadians who speak predominantly a non-official language at home rose 16.0%, from 4.0 million to 4.6 million.

While the Canadian population increased 5.2% during this period, driven mainly by immigration, the number of Canadians who spoke predominantly a South Asian language at home grew faster, particularly speakers of Malayalam (+129% to 35,000 people), Hindi (+66% to 92,000 people), Punjabi (+49% to 520,000 people) and Gujarati (+43% to 92,000 people). In fact, the growth rate of the number of speakers of these languages was at least eight times larger than that of the entire Canadian population.

Other languages spoken predominantly at home also grew rapidly, including Tigrigna, an East African language (+114% to 22,000 people), Turkish (+48% to 28,000 people), Tagalog (+29% to 275,000 people), Arabic (+28% to 286,000 people), Persian languages (+26% to 180,000 people) and Spanish (+20% to 317,000 people).

Mandarin (531,000 speakers) and Punjabi (520,000 speakers) remained the two languages other than English and French spoken predominantly at home by the largest number of Canadians in 2021. The number of Mandarin speakers grew from 2016 to 2021 (+15%), but was outpaced by the growth in the number of Punjabi speakers (+49%).

The rapid growth in the number of speakers of certain languages is mostly due to immigration. According to the Longitudinal Immigration Database, one-quarter of the permanent residents who arrived in Canada from May 2016 to December 2020 were born in a South Asian country, and one in five was born in India. Furthermore, during the same period, about 1 in 10 permanent residents who arrived in Canada was born in China or the Philippines, where Mandarin and Tagalog are spoken, respectively.

The situation was different for a number of European languages. For example, the number of Canadians who spoke predominantly Italian (-23,000), Polish (-10,000) or Greek (-6,000) at home fell from 2016 to 2021. This decrease is primarily linked to the speakers of these languages aging, a significant proportion of whom immigrated to Canada before 1980. What's more, there were relatively few immigrants from Italy, Poland or Greece who recently arrived in Canada.

Canadians who spoke predominantly a language other than English or French at home were more likely to live in a large urban centre than other Canadians. In 2021, fewer than 3 in 4 Canadians (73.8%) lived in a large urban centre, compared with more than 9 in 10 Canadians who spoke predominantly a language other than English or French at home (92.4%). Each year, large urban centres are the destination of a significant proportion of immigrants who settle in Canada, which helps to increase the diversity of these centres.

Meanwhile, in the United States…

While Canada has two official languages and the United States does not, parallels can be drawn between these two countries with respect to languages spoken at home.

According to the 2019 American Community Survey, more than one in five Americans (21.8%) aged 5 years and older spoke a language other than English at home. In Canada, 22.7% of the population spoke a language other than English or French at home at least on a regular basis in 2021. Spanish is the main language spoken in the United States, after English and ahead of Chinese languages, Vietnamese, Tagalog and Arabic. In 2019, there were also over 1 million people who spoke French at home in the United States.

From 2016 to 2019, an increase was observed in the number of speakers of Chinese and South Asian languages (including Hindi and Gujarati) in both the United States and Canada. In addition, the number of people in the United States who speak Polish, Greek or Italian at home decreased, as it did in Canada.

Nearly 7 in 10 Canadians whose mother tongue is neither English nor French speak an official language at home

Canada's two official languages, English and French, remain the languages of convergence—meaning that they are learned, spoken and adopted as the languages of everyday life by many Canadians for whom neither is their mother tongue.

In fact, many Canadians whose mother tongue is a language other than English or French speak one of Canada's two official languages at home, either on a regular basis or predominantly.

In 2021, nearly 7 in 10 Canadians (68.8%) with a non-official mother tongue spoke an official language at home at least on a regular basis. Also, more than one-third (34.8%) spoke predominantly an official language, a proportion that was identical in 2016.

In Quebec, nearly one in two individuals with a non-official mother tongue (47.9%) spoke French at home at least on a regular basis in 2021, while 37.5% spoke English. From 2016 to 2021, the proportion of individuals with a non-official mother tongue living in Quebec speaking predominantly French at home rose slightly (from 18.8% to 20.1%), while the proportion who spoke predominantly English at home remained relatively stable over the same period (from 15.3% to 15.4%).

In Canada outside Quebec, 68.5% of individuals with a non-official mother tongue spoke English at home at least on a regular basis, and 1.5% spoke French at least on a regular basis in 2021. However, the proportion of individuals whose mother tongue is a non-official language and who spoke French at home at least on a regular basis was higher in New Brunswick (8.6%) and some large urban centres, such as Ottawa (10.4%) and Moncton (14.0%).

More than 180,000 people in Canada speak an Indigenous language at home at least on a regular basis

"Indigenous languages are fundamental to the identities, cultures, spirituality, relationships to the land, world views and self-determination of Indigenous peoples." (excerpt from the Indigenous Languages Act)

Indigenous Languages Act

Enacted in 2019, the Indigenous Languages Act provides for the implementation of mechanisms and measures to facilitate appropriate, sustainable and long-term funding to reclaim, revitalize, maintain and strengthen Indigenous languages spoken in Canada. This law establishes the Office of the Commissioner of Indigenous Languages, which is mandated to help promote Indigenous languages, support the efforts of Indigenous peoples to revitalize Indigenous languages, facilitate the resolution of disputes and review complaints, and promote public awareness and understanding in respect of the diversity and richness of Indigenous languages.

Incompletely enumerated reserves and settlements

The COVID-19 pandemic posed some challenges in collecting information from a number of First Nations, Métis or Inuit communities. Some reserves and settlements that were enumerated in 2016 were incompletely enumerated in 2021, which could have impacted the number of people who reported knowing or speaking certain Indigenous languages. As a result, comparisons with previous censuses should be made with caution. For more information, please refer to the technical note on this topic.

It is possible to assess the change in the number of speakers of Indigenous languages by including only the municipalities, reserves and settlements that participated in both the 2016 and 2021 censuses. According to this method, the number of individuals reporting an Indigenous mother tongue, alone or with another language, declined 6.8% from 2016 to 2021 in Canada, while the number of individuals reporting they could have a conversation in an Indigenous language decreased by 3.3% over the same period.

In September 2022, Statistics Canada will release more information on Indigenous languages and identity.

In 2022, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) launched the International Decade of Indigenous Languages to highlight the importance of preserving and revitalizing Indigenous languages, particularly to uphold the right of Indigenous peoples to liberty of expression, education and participation in public life in their mother tongue.

According to UNESCO, the state of Indigenous languages in a number of countries is precarious, including in Canada, where a number of Indigenous languages are vulnerable or endangered. In Canada, the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples shed light of the negative consequences from centuries of colonial history on the use and transmission of Indigenous languages.

More than 70 different Indigenous languages are spoken in Canada. In many cases, incomplete transmission to future generations is reflected in the decrease and the aging of populations speaking these languages. In 2021, more than 20 Indigenous languages in Canada were the mother tongue of 500 or fewer people, whose median age was 60 years and older.

A number of efforts to revitalize Indigenous languages are underway in Canada, including by means of the Indigenous Languages Act.

In Canada, 189,000 individuals reported having an Indigenous mother tongue, alone or in combination with another language, and 183,000 reported speaking an Indigenous language at home at least on a regular basis in 2021. Of these, 86,000 spoke predominantly an Indigenous language at home.

More individuals could conduct a conversation in an Indigenous language—243,000 people in 2021. As in prior censuses, the number of people who can have a conversation in an Indigenous language is greater than the number of people reporting an Indigenous mother tongue. This is an indication that Indigenous languages are being learned as second languages in Indigenous communities.

Cree languages and Inuktitut are the main Indigenous languages spoken at home in Canada. The Inuit language or Inuktut, which includes Inuktitut, Inuinnaqtun and Inuvialuktun, has official language status in Nunavut and the Northwest Territories.

The most widely spoken Indigenous languages differ by region. In the Atlantic provinces, Mi'kmaq is the most common Indigenous language spoken predominantly at home, except in Newfoundland and Labrador, where it is Innu (Montagnais).

Cree languages are the most widely spoken Indigenous languages in Quebec and the Prairie provinces, while in Ontario, Ojibway languages are most common.

The main Indigenous languages spoken at home were different in British Columbia (Dakelh [Carrier]), the Northwest Territories (Tlicho [Dogrib]) and Nunavut (Inuktitut). In Yukon, several Indigenous languages are spoken by a similar number of speakers, such as Tutchone languages, Kaska (Nahani) and Gwich'in.

Of those with an Indigenous mother tongue, alone or with another language, 4 in 10 lived in one of the Prairie provinces and one-quarter lived in Quebec. In fact, Quebec had the largest number of people with at least one Indigenous mother tongue (45,600). Other provinces and territories where Indigenous languages are spoken by a significant number of people included Saskatchewan (27,500), Manitoba (26,500), Alberta (24,600) and Nunavut (23,000).

When a person speaks their mother tongue at home, it is an indicator of that language being retained and a factor associated with its transmission to future generations.

In 2021, nearly four out of five people whose mother tongue is an Indigenous language spoke that language at home at least on a regular basis (78.2%) and more than half spoke it predominantly at home (51.3%).

This proportion was higher for some languages. In 2021, approximately three-quarters of those whose mother tongue was Atikamekw, Innu (Montagnais), Inu Ayimun (Southern East Cree) or Inuktitut spoke predominantly that language at home. This proportion also varied by age. For example, among individuals under 25 years of age with an Indigenous mother tongue, around two-thirds (65.6%) spoke predominantly that language at home.

Looking ahead: Telling the stories of Canadians

The 2021 Census data to be released in the coming months will help to complete the portrait of the Canadian population.

The next releases of 2021 Census of Population data, scheduled for September 21, 2022, will be on First Nations, Métis and Inuit in Canada and on housing in Canada.

On November 30, 2022, other releases will examine the languages used at work and, for the first time, provide information on instruction in the minority official language in Canada.

Please see the 2021 Census release schedule to find out when data and analysis on the different topics will be published throughout 2022.

Note to readers

We encourage you to download the StatsCAN app to consult the census results.

A more accurate portrait of languages spoken at home and multilingualism

In the 2021 Census, the questions on the language spoken at home were changed from previous censuses to make them easier to understand, reduce response burden and improve data quality.

In each census from 2001 to 2016, every Canadian had to answer two questions on the languages spoken at home. The first question asked the entire population which language they spoke most often at home, and the second asked which other languages they spoke at home on a regular basis.

In the 2021 Census, however, the first question asked Canadians which languages they spoke at home at least on a regular basis. Then, only those who provided more than one answer to this question were asked which of the languages specified they spoke most often at home. As a result, Canadians who speak only one language at home had only one question to answer, rather than two.

The concepts and data on the language spoken most often at home are still comparable with previous cycles. However, comparisons for languages spoken equally most often at home must be made with caution. Finally, it is not recommended to compare data for the language spoken at home at least on a regular basis with previous cycles.

Finally, a new category was introduced in the 2021 Census to combine individuals who reported more than one non-official language as their mother tongue or language spoken at home. In previous censuses, there was no distinction between individuals who reported a non-official language and those reporting two or more. The new category "Multiple other languages" is used to better represent the different types of multilingualism of Canadians. The introduction of this new category has minimal impacts on comparisons with previous cycles.

Definitions, concepts and geography

The population growth rates presented in this release are calculated by determining the difference in population size between two dates (such as between two censuses), divided by the population of the first date. They are expressed as a percentage change.

All the results presented in this release are based on 2021 geographic boundaries.

In this release, the term "large urban centre" refers to a census metropolitan area (CMA). A CMA is an urban centre with 100,000 or more people.

The large urban centre of Ottawa corresponds to the Ontario part of the Ottawa–Gatineau CMA.

The term "region" here refers to an economic region.

In this release, the term "municipality" refers to a census subdivision.

The term "Canadians" refers to residents of Canada, regardless of citizenship status.

For a detailed definition of the census language and geography concepts, please consult the Census Dictionary or see the conceptual videos.

2021 Census of Population products and releases

Today, Statistics Canada is releasing a fourth set of results from the 2021 Census of Population.

Several 2021 Census products are also available today on the 2021 Census Program web module. This web module has been designed to provide easy access to census data, free of charge.

The analytical products include this article in The Daily and two infographics. Additional Census in Brief articles will be released in the coming months.

The data products include results on knowledge of official languages, mother tongue, and languages spoken at home, for many standardized geographic regions, and are available through the Census Profile, highlight tables and data tables.

The Focus on Geography series provides data and highlights on key topics found in this Daily release at various levels of geography.

Reference materials are designed to help users make the most of census data. These include the Guide to the Census of Population, 2021, the Dictionary, Census of Population, 2021, the 2021 Census of Population questionnaires, and the 2021 Census Data Quality Guidelines. The Languages Reference Guide, Census of Population, 2021 and the Instruction in the Minority Official Language Reference Guide, Census of Population, 2021 are also available.

Geography-related 2021 Census products and services can be found under Census geography. These include GeoSearch, an interactive mapping tool, and thematic maps, which show data for various standard geographic areas, along with Focus on Geography and the Census Program Data Viewer, which are data visualization tools.

Videos on census concepts can be found in the Census learning centre.

The interactive tree map, Mother tongue by geography, 2021 Census, shows the proportion of the population by mother tongue.

The following two infographics, Increasing diversity of languages, other than English or French, spoken at home and More than one language in the bag: The rate of English–French bilingualism is increasing in Quebec and decreasing outside Quebec, are also available.

Over the coming months, Statistics Canada will continue to release results from the 2021 Census of Population and provide an even more comprehensive picture of the Canadian population. Please see the 2021 Census release schedule to find out when data and analysis on the different topics will be released throughout 2022.

Contact information

For more information, or to enquire about the concepts, methods or data quality of this release, contact us (toll-free 1-800-263-1136; 514-283-8300; infostats@statcan.gc.ca) or Media Relations (statcan.mediahotline-ligneinfomedias.statcan@statcan.gc.ca).

- Date modified: