Aboriginal Peoples Survey

Harvesting activities among First Nations people living off reserve, Métis and Inuit: Time trends, barriers and associated factors

Archived Content

Information identified as archived is provided for reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It is not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards and has not been altered or updated since it was archived. Please "contact us" to request a format other than those available.

by Mohan B. Kumar, Chris Furgal, Peter Hutchinson, Wade Roseborough and Stephanie Kootoo-Chiarello

Skip to text

Text begins

Mohan B. Kumar, Wade Roseborough and Stephanie Kootoo-Chiarello: Statistics Canada

Chris Furgal: Indigenous Environmental Studies & Sciences Program, Trent University

Peter Hutchinson: Canadian Partnership Against Cancer

Note to readers: Chris Furgal and Peter Hutchinson were primarily involved in the Inuit- and Métis-related parts of the study, respectively.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the valuable contribution of Eric Loring, Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami in the development of the proposal, analysis and drafting of the paper. His insight and interpretations greatly strengthened the paper. They also acknowledge the input and feedback on draft versions of the article provided by Esther Usborne (Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami); Annie Gingras (The Congress of Aboriginal Peoples); and Christopher Penney, James Falconer and Jennie Thompson (Indigenous Services Canada (ISC) and Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada (CIRNAC)).

Executive summary

Harvesting activities such as hunting, fishing, trapping and gathering wild plants have been part of Indigenous peoples’ ways of living for millennia. They have endured despite the impact of colonization, including the impacts of residential schools, relocation to permanent settlements and introduction of the wage economy. This paper examines trends in harvesting activities, specifically hunting, fishing or trapping and gathering wild plants or berries, among First Nations people living off reserve, Métis and Inuit using four cycles of the Aboriginal Peoples Survey (2001, 2006, 2012 and 2017). It also explores self-reported barriers to participation in harvesting activities and associated factors.

Key findings

First Nations people living off reserve

In 2017, one in three (33%) First Nations people living off reserve hunted, fished or trapped, and three in ten (30%) gathered wild plants or berries. Across four cycles of the Aboriginal Peoples Survey (APS), spanning 2001 and 2017, overall, little variation in prevalence of harvesting was seen. Characteristics that were associated with hunting, fishing or trapping include remoteness of residence, sex, household income, age, household type and involvement in First Nations organizations, social events or cultural activities. For example, the likelihood of hunting, fishing or trapping increased with increasing household income. Characteristics associated with gathering include remoteness, sex, being unemployed, household type, having spent time trying to find out more about First Nations history, traditions and culture, and being active in First Nations organizations, social events or cultural activities. First Nations people who had not hunted, fished or trapped in the previous year despite being interested reported several barriers to participation. The leading self-reported barriers to harvesting activities were time constraints and location: 41% reported not having enough time to hunt, fish or trap, and 28% cited location barriers. Time constraints were more likely to be reported by employed individuals (54%) than those unemployed (27%Note E : use with caution) or out of the labour force (23%). The results allude to the ties between harvesting activities and the wage economy.

Métis

Among Métis, in 2017, about one in three (35%) had hunted, fished or trapped. Across four cycles of the APS, the prevalence of hunting, fishing or trapping was lower in 2012 (36%) and 2017 (35%) compared to 2006 levels (44%). Among youth and young adults, a significant downward trend was evident after 2006. It decreased from 46% in 2006 to 38% in 2012 and 33% in 2017. For gathering wild plants or berries, no significant upward or downward trend was observed. Several characteristics were associated with participation in hunting, fishing or trapping including remoteness of place of residence, sex, household income, labour force status, age, health, and involvement in Métis organizations, social events or cultural activities. For example, those who were employed were significantly more likely to hunt, fish or trap than out-of-the-labour-force Métis. In 2017, Métis who had not harvested in the previous year in spite of being interested cited several barriers to participation. The leading barrier to hunting, fishing or trapping was time, reported by 47%. Nearly two-thirds (62%) of those employed reported not having enough time for these activities while a significantly smaller proportion of those unemployed (37%Note E : use with caution) and out of the labour force (20%) did so. For gathering, remoteness, sex, being unemployed, having spent time trying to find out more about Métis history, traditions and culture, and being active in Métis organizations, social events or cultural activities were associated with participation in this activity, and the predominant barrier was time. The findings on associated characteristics complement the self-reported barriers, and describe the relationship between participation in harvesting activities and the wage economy.

Inuit

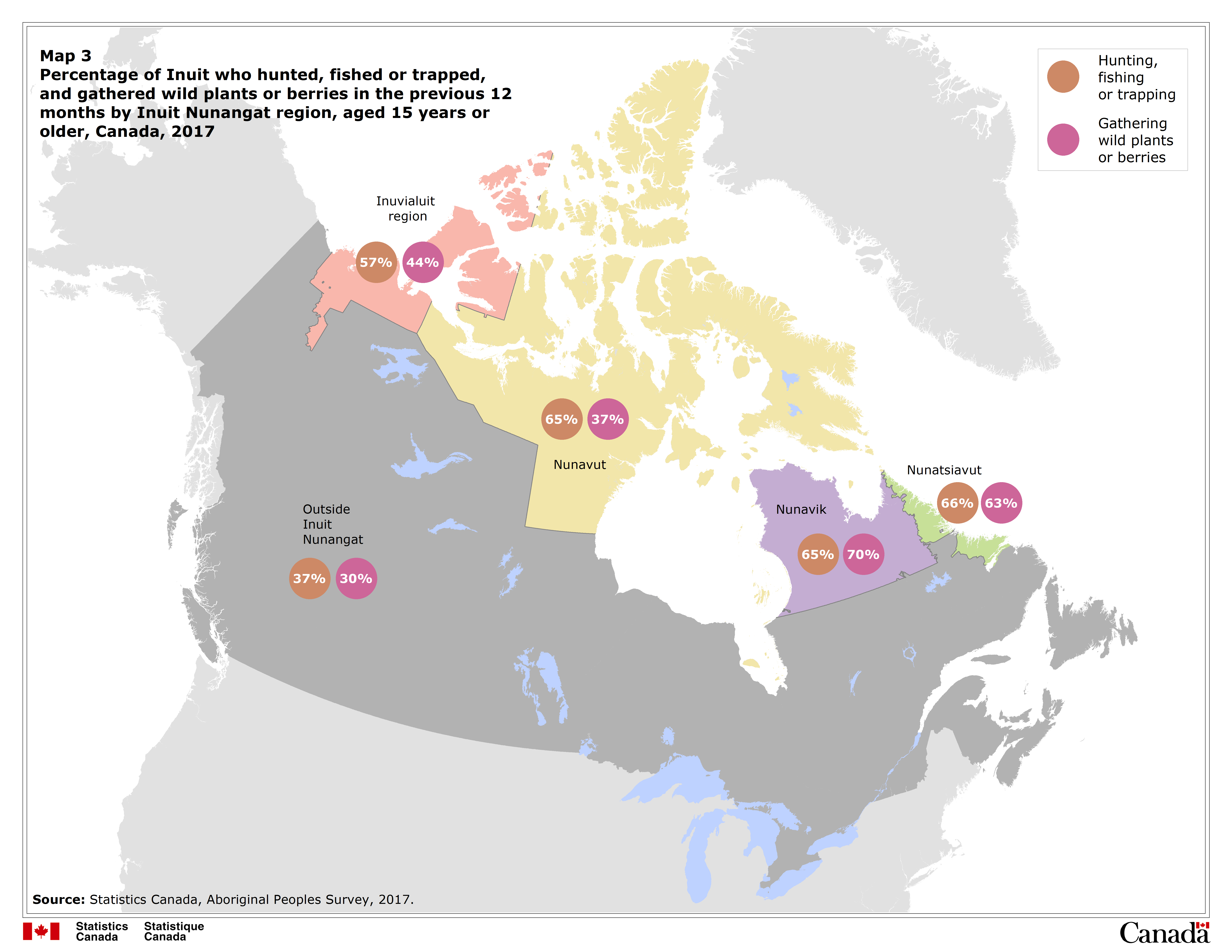

Among Inuit in Inuit Nunangat, the Inuit homeland in Canada, about two-thirds (65%) had hunted, fished or trapped and about one-half (47%) had gathered wild plants or berries in 2017. Across four cycles of the APS, spanning nearly 20 years, a decreasing trend in participation in hunting, fishing or trapping emerged after 2006. When examined by age group, the declining trend was seen only among working-age adults. Participation decreased from 70% in 2006 to 63% in 2012 to 58% in 2017. Several socioeconomic and demographic characteristics were associated with participation in hunting, fishing or trapping including sex, labour force status, household type and involvement in Inuit organizations, social events or cultural activities. For example, employed Inuit were more likely than unemployed and out-of-the-labour-force Inuit to hunt, fish or trap. For gathering wild plants or berries, only Inuit Nunangat region of residence, sex, being out of the labour force and being active in Inuit organizations, social events or cultural activities were associated with participation. Inuit who had not hunted, fished or trapped in the previous year despite being interested identified several barriers to participation. The predominant barriers include time, money and location. Time (33%) and monetary (29%) barriers were cited by about one in three, while location barriers were reported by one in five (19%). Inuit who were employed (47%) were more than twice as likely to report time-related barriers to hunting, fishing or trapping than those unemployed (21%Note E : use with caution) or out of the labour force (20%Note E : use with caution). In contrast, employed Inuit (21%) were significantly less likely to report monetary barriers than the other two labour force groups (58% among the unemployed and 31% among out-of-the-labour-force Inuit). These factors and barriers describe some of the features of the mixed economy in Inuit regions that blends harvesting with the wage economy, and allude to the tensions between participation in harvesting activities and wage economy.

Background

Harvesting activities such as hunting, fishing, trapping and gathering wild plants have been part of Indigenous peoples’ way of life in Canada for millennia. Despite the impact of colonization, and the resulting effect of residential schools, relocation to permanent settlements, introduction of the wage economy, and political constraints which directly or indirectly impacted harvesting activities,Note 1Note 2Note 3 they have endured. However, as a result of continuing economic, social and political pressures, emerging climatic factors, and potentially decreased transmission of traditional knowledge and skills, participation in these activities in many communities is declining.Note 3Note 4 This is of great concern considering the multiple benefits of engagement in harvesting activities.

Participation in harvesting activities has been identified as being important for the fostering cultural identity and morale.Note 5 Among InuitNote 5Note 6Note 7 and First Nations people on reserve,Note 8 it is key to meeting nutritional needs and supporting food security. Other advantages include increased physical activity, prevention of chronic disease, better mental health, and lower food costs.Note 5 There are also mostly unrecognized benefits to the economy. Harvesting and gathering activities are conservatively estimated to have a “shadow value” of over $10 million in the Qikiqtaaluk Region of Nunavut alone.Note 9 Despite these benefits, a clear national picture of harvesting activities is missing.

Some studies have examined prevalence of participation at a snapshot in time. In 1991, approximately 50-80% of Registered Indians, or those who are registered under the Indian Act of Canada, participated in traditional activities with differences being influenced by place of residence, age group and gender.Note 10 Among Métis in Canada, in 2006, fishing and gathering wild plants were the most prevalent harvesting activities, with 40% and 30%, respectively, of those 15 years or older engaged in these activities.Note 11 Among Inuit, studies have alluded to a decline in participation in harvesting activities in the younger generation.Note 12Note 13Note 14 However, few studies have examined trends over time among off-reserve First Nations people and Métis. Further, there is ample evidence of growing and shifting challenges to harvesting activities among First Nations people and Inuit.Note 3Note 4Note 14

Many studies have explored barriers to participation in harvesting activities. Time limitations due to employment is the most frequently reported barrier.Note 3 School attendance and family responsibilities also exacerbate the time constraint. This is followed by ever-increasing financial cost for vehicles, equipment and fuel,Note 15Note 16Note 17Note 18 ammunition costs, longer travel distances, and obtaining gun licences.Note 3Note 16Note 19 Employment in the context of harvesting activities has been portrayed as a double-edged sword since it provides the financial resources to procure equipment and supplies but reduces the time available for these activities.Note 3 Other factors include a lack of interest and/or knowledge required for harvesting activities,Note 3Note 16 poor health or disability, school attendance, childcare and declining game animal population numbers.Note 3

The role of the residential school system on harvesting activities today is expected to be significant because of its impact on multiple aspects of Indigenous peoples lives.Note 20Note 21Note 22Note 23 In this system, parents and elders could not transmit their traditional knowledge and skills when children were removed from their home, and many were prohibited from practicing traditional activities.Note 24 The intergenerational impacts of residential school attendance extend to harvesting activities.Note 3Note 24

Climate change is also playing an increasingly significant role in influencing harvesting activities, particularly among Indigenous people in the Arctic, since it is making these activities more dangerous and, by some reports, restricting access to typical hunting areas.Note 25Note 26Note 27 It has influenced changes in the appearance and availability of fish species, declines in numbers of caribou and moose, hunting periods, and changes to weather conditions affecting travel and safe access to harvesting areas.Note 28Note 19 Other environmental impacts on harvesting include contamination of traditional foods.Note 29 In totality, the barriers to harvesting activities are considered “complex, dynamic, and occur[ing] at multiple scales of experience.”Note 3

Several programs have been developed to support harvesting activities among First Nations people, Métis and Inuit. These programs include the Commercial Harvest Program, Traditional Harvest Program, Western Harvester’s Assistance Program, community organized hunts, Take a Kid Trapping Program, to name a few.Note 29Note 30 In Nunavut, the Nunavut Harvester Support Program helps members obtain hunting and fishing supplies.Note 16 In Nunavik the Inuit Hunting, Fishing and Trapping Support Program provides a variety of forms of support and assistance to increase participation in, success of and contributions by participation in these activities to community health and well-being.Note 31

While there are numerous studies on harvesting activities, many are often limited to Inuit or on-reserve First Nations peoples. Furthermore, a national picture on trends, reasons for participating or not participating, and factors associated with harvesting activities among First Nations people living off reserve, Métis and Inuit is lacking. This paper will contribute to the growing body of literature and could inform the development of tailored programs and policies to increase participation.

Aim of study

This paper aims to address existing information gaps on prevalence, trends and factors associated with harvesting activities by answering several questions using the nationally representative APS over several cycles. These questions include: (1) is participation in harvesting activities – specifically, hunting, fishing or trapping and gathering wild plants or berries – changing over time among First Nations people living off reserve, Métis and Inuit, (2) what labour force, socioeconomic and demographic factors are associated with participation in harvesting activities, and (3) what are the reasons for participation and non-participation in harvesting activities, and are they different by sex, age group, labour force status, place of residence and family type? The findings could further understanding of harvesting barriers and facilitators among these populations. This could inform the development of policies and programs to increase participation in harvesting activities.

Note to reader: While the time trends are based on four cycles of the APS, the bulk of the statistics presented are based on two cycles of the APS: 2012 and 2017. The 2012 APS was used where similar data was not available from the 2017 APS. The reference years are indicated at the beginning of the section as applicable.

Results

Harvesting among First Nations people living off-reserve

Hunting, fishing, trapping and gathering wild plants have been an integral part of First Nations people’s way of living since time immemorial. These activities are the foundations of cultural identity for many First Nations people in Canada. They are also important for livelihood, nutrition, health and physical fitness, and retaining traditional knowledge of the land and way of life of First Nations people.Note 32 Land-based practices vary by region, availability of food species and traditional practices.Note 32 In spite of the detrimental effects of colonization, including the impacts of residential schools and other economic, social and political factors such as the introduction of the wage economy, harvesting activities have endured.Note 3Note 24

Several barriers to harvesting have been identified previously among First Nations people living on reserve. These include time limitations as a result of employment and lack of interest and/or harvesting knowledge.Note 3 Other constraints include poor health, childcare responsibilities and cost of harvesting. Barriers vary by region and community. For example, among two communities in the same reserve in Alberta, the predominant barriers differed. In one, it was the financial cost of harvesting, while in the other it was not having enough time as a result of being employed.Note 3 Barriers also vary by age and sex.

Little is known about these activities among First Nations people living off reserve. This section explores trends in participation in harvesting activities, factors associated with participation, and reasons for participation and non-participation among off-reserve First Nations people aged 15 years or older.

Prevalence of harvesting activities among off-reserve First Nations people varies little by province and territory

In 2017, nearly one-half (47%) of First Nations people living off reserve reported having engaged in harvesting activities, i.e. hunting, fishing, trapping or gathering wild plants or berries in the past 12 months. One in three (33%) hunted, fished or trapped, and a somewhat lower proportion (30%) gathered wild plants or berries.

Prevalence of hunting, fishing or trapping (Map 1) showed little variation by province and territory with the exception of Yukon (58%) and Newfoundland and Labrador (56%), where First Nations people living off reserve were significantly more likely to engage in this activity than those in other jurisdictions (ranging from 28% to 37%). The patterns were similar for gathering wild plants or berries (Map 2).

Description for Map 1

| Province or Territory | Percent |

|---|---|

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 56 |

| Prince Edward Island | Note F: too unreliable to be published |

| Nova Scotia | 33 |

| New Brunswick | 35 |

| Quebec | 35 |

| Ontario | 34 |

| Manitoba | 30 |

| Saskatchewan | 33 |

| Alberta | 32 |

| British | 28 |

| Yukon | 58 |

| Northwest Territories | 37 |

| Nunavut | 43Note E: Use with caution |

|

E use with caution F too unreliable to be published Source: Statistics Canada, Aboriginal Peoples Survey, 2017. |

|

This map shows the percent of First Nations people living off reserve, aged 15 or older, who had hunted, fished or trapped in the previous 12 months in 2017 by province and territory. The provinces and territories are shown in lighter or darker shades of green based on the percent.

| Colour | Description |

|---|---|

| Lightest green | Represents percentages less than 25% |

| Second darkest green | Represents percentages from 25% to less than 34% |

| Third darkest green | Represents percentages from 34% to less than 50% |

| Darkest green | Represents percentages 50% or greater |

Description for Map 2

| Province or Territory | Percent |

|---|---|

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 64 |

| Prince Edward Island | Note F: too unreliable to be published |

| Nova Scotia | 41 |

| New Brunswick | 44 |

| Quebec | 24 |

| Ontario | 28 |

| Manitoba | 23 |

| Saskatchewan | 24 |

| Alberta | 29 |

| British | 30 |

| Yukon | 47 |

| Northwest Territories | 30 |

| Nunavut | Note F: too unreliable to be published |

|

F too unreliable to be published Source: Statistics Canada, Aboriginal Peoples Survey, 2017. |

|

This map shows the percent of First Nations people living off reserve, aged 15 or older, who had gathered wild plants or berries in the previous 12 months in 2017 by province and territory. The provinces and territories are shown in lighter or darker shades of purple based on the percent.

| Colour | Description |

|---|---|

| Lightest purple | Represents percentages less than 25% |

| Second darkest purple | Represents percentages from 25% to less than 34% |

| Third darkest purple | Represents percentages from 34% to less than 50% |

| Darkest purple | Represents percentages 50% or greater |

Little variation in prevalence of hunting, fishing or trapping across cycles among First Nations people living off reserve

While the picture from 2017 provides the most recent snapshot of harvesting activities among First Nations people living off reserve, examining prevalence over time could identify potential trends. To date, few studies have examined trends in prevalence of harvesting over time among First Nations people,Note 33 particularly among those living off reserve. When participation in harvesting activities was compared over four cycles of the APS among First Nations people living off reserve aged 15 or older, some variation in prevalence of hunting, fishing or trapping was evident. The prevalence was lower in 2017 (33%) compared to 2001 and 2006 (37%), representing a 10% decrease. The prevalence of gathering wild plants or berries did not markedly vary across the four cycles.

Among the three age groups, older adults (aged 55 or older) were consistently less likely to hunt, fish or trap than youth and young adults (aged 15 to 24) or core working-age adults (aged 25 to 54) across the cycles (Chart 1). No significant upward or downward trend was seen in the three age groups. However, among youth and young adults, the prevalence in 2017 (33%) was significantly lower than in 2006 (41%) and 2012 (38%).

Data table for Chart 1

| Age group | 2001 | 2006 | 2012 | 2017 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percent | 95% confidence interval | Percent | 95% confidence interval | Percent | 95% confidence interval | Percent | 95% confidence interval | |||||

| Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | |||||

| 15 to 24 years | 36 | 33 | 39 | 41 | 38 | 44 | 38 | 34 | 41 | 33 | 30 | 35 |

| 25 to 54 years | 39 | 37 | 42 | 38 | 37 | 40 | 37 | 34 | 39 | 36 | 34 | 38 |

| 55 years or older | 27 | 24 | 31 | 29 | 26 | 32 | 26 | 23 | 30 | 28 | 26 | 30 |

| Sources: Statistics Canada, Aboriginal Peoples Survey, 2001, 2006, 2012 and 2017. | ||||||||||||

Youth and young adults were less likely to participate in wild plant or berry gathering than those in other age groups in most cycles (Chart 2). Little variation in prevalence was evident across cycles among the three age groups.

Data table for Chart 2

| Age group | 2001 | 2006 | 2012 | 2017 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percent | 95% confidence interval | Percent | 95% confidence interval | Percent | 95% confidence interval | Percent | 95% confidence interval | |||||

| Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | |||||

| 15 to 24 years | 20 | 17 | 22 | 26 | 24 | 28 | 23 | 21 | 26 | 22 | 20 | 24 |

| 25 to 54 years | 31 | 29 | 33 | 31 | 30 | 33 | 30 | 28 | 33 | 32 | 30 | 34 |

| 55 years or older | 28 | 25 | 33 | 28 | 25 | 31 | 31 | 27 | 35 | 33 | 31 | 35 |

| Sources: Statistics Canada, Aboriginal Peoples Survey, 2001, 2006, 2012 and 2017. | ||||||||||||

Males were consistently more likely to hunt, fish or trap than females. For males, a significantly lower percentage (17% lower) participated in 2017 (42%) compared with 2006 (50%). Among females, little variation was seen from cycle to cycle. Females were consistently more likely to gather wild plants or berries than males. No upward or downward trend emerged in either sex.

Off-reserve First Nations people living in rural areas were consistently more likely to hunt, fish or trap and gather wild plants or berries than those in urban areas with no notable difference in prevalence over cycles.

Between Status Indians, or those who are Registered or Treaty Indians as defined by the Indian Act of Canada, and non-Status Indians, no significant differences in prevalence of hunting, fishing or trapping was seen from one cycle to another with the exception of 2006, when it was significantly higher among Status Indians (41%) than non-Status Indians (35%). In both groups, no upward or downward trend was evident. No significant differences across cycles or a trend was seen for gathering wild plants or berries.

Trends in potentially influential factors

Harvesting trends should be viewed in the context of changes to potentially influential factors including urbanization, engagement in the wage economy, socio-political environment, demographic changes to name a few.

Despite its youthful structure, the population of First Nations people living off reserve is somewhat aging (Chart 3). In fact, the proportion of those over the age of 55 has increased since 2001. However, the proportion of youth and young adults has remained somewhat invariant, while the proportion of 35-to-44-year-olds has significantly decreased. The median age of the 15-plus population increased from 35 years in 2001 to 39 years in 2017.

Data table for Chart 3

| Socioeconomic and demographic characteristics | 2001 | 2006 | 2012 | 2017 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percent | 95% confidence interval | Percent | 95% confidence interval | Percent | 95% confidence interval | Percent | 95% confidence interval | |||||

| Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | |||||

| Age | ||||||||||||

| 15 to 24 years | 24 | 23 | 25 | 23 | 22 | 25 | 24 | 23 | 25 | 24 | 23 | 24 |

| 25 to 34 years | 22 | 21 | 24 | 19 | 18 | 20 | 18 | 17 | 19 | 18 | 17 | 20 |

| 35 to 44 years | 25 | 23 | 26 | 21 | 20 | 22 | 20 | 18 | 21 | 16 | 15 | 17 |

| 45 to 54 years | 16 | 15 | 17 | 19 | 18 | 20 | 18 | 16 | 19 | 19 | 18 | 20 |

| 55 to 64 years | 8 | 7 | 9 | 11 | 10 | 12 | 13 | 11 | 14 | 14 | 13 | 14 |

| 65 years or older |

5 | 4 | 6 | 7 | 6 | 8 | 8 | 7 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 10 |

| Median age of 15+ population (years) | 35 | 35 | 36 | 38 | 37 | 39 | 38 | 38 | 39 | 39 | 38 | 40 |

| Education | ||||||||||||

| Less than high school | 38 | 36 | 39 | 35 | 33 | 36 | 25 | 24 | 27 | 20 | 19 | 21 |

| High school | 14 | 13 | 16 | 15 | 14 | 16 | 15 | 14 | 17 | 16 | 15 | 18 |

| Post-secondary education below bachelor's level | 42 | 41 | 44 | 41 | 39 | 42 | 50 | 48 | 52 | 53 | 51 | 54 |

| University or higher |

5 | 5 | 6 | 10 | 9 | 11 | 10 | 9 | 11 | 11 | 10 | 12 |

| Labour force status | ||||||||||||

| Employment rate | 57 | 55 | 59 | 60 | 59 | 61 | 57 | 55 | 58 | 55 | 53 | 56 |

| Unemployment rate | 14 | 13 | 15 | 10 | 9 | 11 | 14 | 12 | 16 | 14 | 13 | 15 |

| Not in the labour force | 34 | 32 | 36 | 33 | 32 | 35 | 35 | 33 | 36 | 36 | 35 | 38 |

| Geography | ||||||||||||

| Urban | 76 | 75 | 77 | 76 | 74 | 77 | 80 | 79 | 82 | 77 | 76 | 78 |

| Rural | 23 | 22 | 24 | 24 | 22 | 25 | 19 | 18 | 21 | 23 | 22 | 24 |

| Sources: Statistics Canada, Aboriginal Peoples Survey, 2001, 2006, 2012 and 2017. | ||||||||||||

The off-reserve First Nations population is also making educational advancements. The proportion of those with less than a high school education has significantly decreased year over year (Chart 3). In parallel, the proportion of those with a post-secondary education has increased. Despite these trends, the employment rate has decreased, while the unemployment rate has not changed significantly. However, it is important to note that these rates are a snapshot in time and reflect the economic conditions at the time of the survey. Year-by-year analysis has previously show that there are significant fluctuations in rates over time among First Nations people living off reserve.Note 34 First Nations people living off reserve predominantly reside in urban areas (roughly 75%) (Chart 3). This has changed little over the last four cycles of the APS.

While examination of these characteristics suggests factors that may have potentially influenced the trends, it is important to note that the statistical associations between these characteristics and the trends in participation were not explored in this report.

First Nations people living off reserve harvest mainly for own use

In 2017, almost all First Nations people who had participated in hunting, fishing or trapping did so either for their own, or their own family’s use (85%) or for pleasure or leisure (81%). In interpreting the findings for pleasure or leisure, it is important to distinguish this from sport hunting, which is often associated with reasons of pleasure and leisure. For many First Nations people these activities provide a sense of identity, connection with the land, and an opportunity to spend time with community members, family or friends.Note 35Note 36 Roughly four in ten engaged in hunting, fishing or trapping to share with the community (40%) or for cultural reasons (37%). Far fewer (4%) did so for money or to supplement their income.

Almost all off-reserve First Nations people that had gathered wild plants or berries, did so for their own or own family’s use (92%), and about seven in ten (72%) for pleasure or leisure. About one half engaged in this activity to share the harvest with their community (50%) or for cultural reasons (49%). Four percent engaged in this activity for money or to supplement their income.

Why off-reserve First Nations people hunt, fish or trap varies by socioeconomic and demographic factors

Select reasons for hunting, fishing or trapping were examined by socioeconomic and demographic factors with the aim of uncovering findings that could inform tailored programs and policies. Also, specifically, it can identify those who are more likely to share their harvest with others in the community. These may have implications for nutrition and food security. It should be noted that the reasons are not mutually exclusive as individuals could report more than one reason for participating.

When it came to hunting, fishing or trapping for own use or own family’s use, the only difference was seen between age groups – youth and young adults (76%) were less likely to participate for this reason than working-age adults (86%) or older adults (89%) (Table 1). Hunting, fishing or trapping to share with others in the community was significantly more prevalent among unemployed First Nations people (58%) than those employed (37%) or out of the labour force (39%). This was also more likely among males (42%) than females (37%). Youth and young adults (32%) were less likely to hunt, fish or trap for cultural reasons than core working-age adults (39%) and older adults (40%). Unemployed individuals (48%) were more likely to participate for cultural reasons than those that were employed (36%) or out-of-the-labour-force (37%). Males (5%) were more than twice as likely as females (2%Note E : use with caution) to engage in this activity for money or to supplement income. Unemployed individuals (9%Note E : use with caution) were three times as likely as employed individuals (3%Note E : use with caution) to partake for this reason. Those living in rural areas (5%) were also more likely to report this reason than those in urban areas (3%). Some of these patterns were similar when examining gathering wild plants or berries for monetary reasons and cultural reasons (Table 1).

| Reasons for hunting, fishing or trapping in the previous 12 months | Reasons for gathering wild plants or berries in the previous 12 months | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| For pleasure or leisure | Own use/family’s use | To share with others in the community | For cultural reasons | For money or to supplement income | For some other reason | For pleasure or leisure | Own use/family’s use | To share with others in the community | For cultural reasons | For money or to supplement income | For some other reason | |

| percent | ||||||||||||

| Sex | ||||||||||||

| Males | 81 | 84 | 42Note * | 37 | 5Note * | 9 | 67Note * | 91 | 48 | 44Note * | 5Note * | 9 |

| Females (reference category) | 81 | 86 | 37 | 38 | 2Note E: Use with caution | 9 | 75 | 94 | 51 | 51 | 3Note E: Use with caution | 10 |

| Age group | ||||||||||||

| 15 to 24 years | 80 | 76Note * | 37 | 32Note * | 5Note E: Use with caution | 10 | 69 | 88 | 45 | 42Note * | 5Note E: Use with caution | 10 |

| 25 to 54 years (reference category) | 81 | 86 | 40 | 39 | 3Note E: Use with caution | 8 | 71 | 92 | 50 | 49 | 3Note E: Use with caution | 8 |

| 55 years or older | 81 | 89 | 44 | 40 | 5 | 10 | 74 | 96Note * | 54 | 51 | 3Note E: Use with caution | 11 |

| Labour force status | ||||||||||||

| Employed (reference category) | 84 | 84 | 37 | 36 | 3Note E: Use with caution | 8 | 72 | 92 | 50 | 49 | 3Note E: Use with caution | 9 |

| Unemployed | 72Note * | 84 | 58Note * | 48Note * | 9Note E: Use with cautionNote * | 11Note E: Use with caution | 69 | 92 | 55 | 54 | 8Note E: Use with cautionNote * | 12 |

| Out of the labour force | 77Note * | 87 | 39 | 37 | 5Note * | 8 | 71 | 94 | 49 | 47 | 4Note E: Use with caution | 9 |

| Place of residence | ||||||||||||

| Urban | 83Note * | 84 | 39 | 37 | 3Note * | 8 | 72 | 92 | 49 | 50 | 3 | 9 |

| Rural (reference category) | 77 | 86 | 41 | 38 | 5 | 10 | 70 | 94 | 51 | 45 | 4Note E: Use with caution | 10 |

E use with caution

Source: Statistics Canada, Aboriginal Peoples Survey, 2017. |

||||||||||||

Four in ten off-reserve First Nations people who harvest do it at least weekly during season

Knowledge of frequency of participation and the perception of adequacy of time spent, and their socioeconomic and demographic profiles, can also better inform policies and programs to support harvesting among off-reserve First Nations people.

Frequency of participation

In 2017, off-reserve First Nations people who had engaged in harvesting activities were asked how often they participated in these activities during harvesting season. About four in ten (39%) had hunted, fished or trapped at least once a week (“higher frequency”). Three in ten had participated at least once a month but less than once a week, and a similar proportion had participated less than once a month (32%). Patterns were similar for gathering wild plants or berries.

Older adults (49%) were significantly more likely to hunt, fish or trap at a higher frequency than youth and young adults and core working-age adults (36% each) (Table 2). Interestingly, unemployed (48%) and out-of-the-labour-force individuals (43%) were more likely to do so than employed (35%). Somewhat similar patterns also emerged for gathering wild plants or berries.

| Hunted, fished or trapped at least once a week during season | Gathered wild plants or berries at least once a week during season | |

|---|---|---|

| percent | ||

| Sex | ||

| Males | 43Note * | 43 |

| Females (reference category) | 33 | 45 |

| Age group | ||

| 15 to 24 years | 36 | 30Note * |

| 25 to 54 years (reference category) | 36 | 44 |

| 55 years or older | 49Note * | 54Note * |

| Labour force status | ||

| Employed (reference category) | 35 | 40 |

| Unemployed | 48Note * | 43 |

| Out of the labour force | 43Note * | 52Note * |

| Place of residence | ||

| Urban | 33Note * | 37Note * |

| Rural (reference category) | 50 | 59 |

Source: Statistics Canada, Aboriginal Peoples Survey, 2017. |

||

Six in ten off-reserve First Nations people who harvest would like to spend more time on this activity

In 2012, those who had engaged in these activities for money, to supplement their income, for own use or their family’s use, or to share with others in their own or other communities, were asked if they were satisfied with time spent on harvesting activities.

About six in ten (57%) wanted to spend more time on hunting, fishing or trapping (than they had in the past 12 months) and four in ten (42%) thought they were spending the right amount of time participating in these activities. Off-reserve First Nations men (61%) were more likely to want to spend more time on this activity than women (50%). So were core working-age adults (62%) when compared with youth and young adults (48%) or older adults (50%). The perception did not vary significantly by degree of rurality or between Status- and non-Status Indians.

When it came to gathering wild plants or berries, about six in ten (62%) thought they were spending the right amount of time on this activity and one in three (35%) expressed that they would like to spend more time participating in these activities. Socioeconomic and demographic patterns for gathering were similar to that for hunting, fishing or trapping.

When those who had wanted to spend more time were asked what reasons have prevented them from doing these activities more often, the leading reason, expressed by two-thirds, was not having enough time. About one in six (16%) said they did not have enough money for supplies or equipment. About one in eight said the location (12%) prevented them from hunting, fishing or trapping more often. Time barrier was more likely to be reported by working-age adults (74%) than youth and young adults (55%) or older adults (48%). This was also the case among employed (80%) when compared with unemployed (46%Note E : use with caution) or out-of-the-labour-force individuals (40%). A monetary barrier was cited by unemployed (33%Note E : use with caution) more than employed (13%Note E : use with caution) individuals. For the location barrier, youth and young adults (21%) were twice as likely as core working-age adults (10%Note E : use with caution) to identify this as a limitation. This was also the case for unemployed (22%Note E : use with caution) compared with employed individuals (9%Note E : use with caution).

For gathering wild plants or berries, the leading barriers to more frequent participation were time (66%) and location (19%). Core working-age adults (73%) were more likely than older adults (49%) to report time constraints. Employed (80%) as opposed to out-of-the-labour-force individuals (42%) were nearly twice as likely to cite this reason. Off-reserve First Nations people living in urban areas (24%) were nearly five times as likely to say location was a barrier as those in rural areas (5%Note E : use with caution).

Barriers to participation: Time and location constraints leading barriers to harvesting

In 2012, among off-reserve First Nations people who had not participated in hunting, fishing or trapping in the prior year, about four in ten (38%) expressed interest in participating. Men (49%) were more likely than women (32%) to acknowledge interest. Core working-age adults (42%) were more likely than youth and young adults (38%) and older adults (27%) to want to hunt, fish or trap. Unemployed individuals (47%) were more likely than employed (39%) or out-of-the-labour-force individuals (34%) to express interest. Status Indians (40%) were more likely than non-Status Indians (34%) to be interested in participating. The leading reason for not participating was not having enough time (41%) followed by location (28%) (Chart 4). About one in seven reported not having enough money, having no one to do it with or other reasons.

Data table for Chart 4

| Reasons for non-participation | Percent | 95% confidence interval | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||

| Not enough time | 41 | 36 | 45 |

| Location | 28 | 25 | 32 |

| Not enough money for equipment or supplies |

15 | 12 | 17 |

| No one to hunt, fish or trap with | 13 | 11 | 16 |

| Physical disability | 9 | 5 | 14 |

| Quota restrictions | 2 | 1 | 4 |

| Fewer animals | Note F: too unreliable to be published | Note F: too unreliable to be published | Note F: too unreliable to be published |

| Other | 16 | 13 | 19 |

|

F too unreliable to be published Note: Percentages are computed using the number of people who were interested but did not participate in the described activity in the previous year as the denominator. Source: Statistics Canada, Aboriginal Peoples Survey, 2012. |

|||

One in four off-reserve First Nations people who had not gathered wild plants or berries in the previous year wanted to engage in these activities. Women (29%) were more likely than men (20%) to express this interest. Core working-age adults (28%) were more likely than youth and young adults (20%) and older adults (22%) to want to do this activity. Unemployed off-reserve First Nations people (30%) were more likely than employed (24%) or those in not the labour force (24%) to report this. Those in female lone-parent households (31%) were more likely to want to gather than those in couple-headed households with children (23%) or male lone-parent households (21%Note E : use with caution). Status Indians (27%) were more likely than non-Status Indians (19%) to want to gather. The leading reason for not having gathered wild plants or berries despite an interest was not having enough time (41%). About three in ten (29%) cited location while one in five (21%) cited having no one to teach the skills needed. Other reasons were significantly less prevalent (10% or less).

To add to the picture on harvesting barriers among off-reserve First Nations people, the reasons for not participating were examined by select socioeconomic and demographic factors (Table 3). Among the age groups, youth and young adults (42%) and working-age adults (44%) were more likely than older adults (28%Note E : use with caution) to cite time barriers. Monetary barriers were less prevalent among older adults (7%Note E : use with caution) than core working-age adults (15%). Youth and young adults (21%) were more likely to indicate they had no one to hunt, fish or trap with than other age groups (about one in ten).

| Reasons for not having hunted, fished or trapped | Reasons for not having gathered wild plants or berries | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not enough time | Location | Not enough money for supplies or equipment | No one to do it with | Physical disability | Fewer animals | Quota restrictions | Other | Not enough time | Location | No one to teach needed skills | Physical disability, health or medical reasons | Not enough money for supplies or equipment | Fewer plants/berries to harvest | Other | |

| percent | |||||||||||||||

| Sex | |||||||||||||||

| Males | 44 | 26 | 13 | 12 | 8Note E: Use with caution | Note F: too unreliable to be published | Note F: too unreliable to be published | 15 | 46 | 27 | 16Note E: Use with caution | 7Note E: Use with caution | 3Note E: Use with caution | Note F: too unreliable to be published | 9Note E: Use with caution |

| Females (reference category) | 38 | 30 | 16 | 14 | 9Note E: Use with caution | Note F: too unreliable to be published | Note F: too unreliable to be published | 16Note E: Use with caution | 38 | 30 | 23 | 8Note E: Use with caution | 4Note E: Use with caution | 7Note E: Use with caution | 10Note E: Use with caution |

| Age group | |||||||||||||||

| 15 to 24 years | 42 | 26 | 19 | 21Note * | Note F: too unreliable to be published | Note F: too unreliable to be published | Note F: too unreliable to be published | 16 | 42 | 28 | 24 | Note F: too unreliable to be published | Note F: too unreliable to be published | 7Note E: Use with caution | 8Note E: Use with caution |

| 25 to 54 years (reference category) | 44 | 31 | 15 | 11 | 7Note E: Use with caution | Note F: too unreliable to be published | 2Note E: Use with caution | 15 | 44 | 31 | 22 | 4Note E: Use with caution | 4Note E: Use with caution | 7Note E: Use with caution | 10Note E: Use with caution |

| 55 years or older | 28Note E: Use with cautionNote * | 20Note E: Use with cautionNote * | 7Note E: Use with cautionNote * | 11Note E: Use with caution | 25Note E: Use with cautionNote * | Note F: too unreliable to be published | Note F: too unreliable to be published | Note F: too unreliable to be published | 29Note E: Use with cautionNote * | 26Note E: Use with caution | 13Note E: Use with cautionNote * | 26Note E: Use with cautionNote * | Note F: too unreliable to be published | Note F: too unreliable to be published | 11Note E: Use with caution |

| Labour force status | |||||||||||||||

| Employed (reference category) | 54 | 26 | 13 | 11 | Note F: too unreliable to be published | Note F: too unreliable to be published | Note F: too unreliable to be published | 15 | 53 | 24 | 19 | 2Note E: Use with caution | Note F: too unreliable to be published | 6Note E: Use with caution | 10Note E: Use with caution |

| Unemployed | 27Note E: Use with cautionNote * | 39Note * | 22Note E: Use with cautionNote * | 21Note E: Use with cautionNote * | Note F: too unreliable to be published | Note F: too unreliable to be published | Note F: too unreliable to be published | 11Note E: Use with caution | 23Note E: Use with cautionNote * | 39Note E: Use with cautionNote * | 36Note E: Use with cautionNote * | Note F: too unreliable to be published | Note F: too unreliable to be published | Note F: too unreliable to be published | Note F: too unreliable to be published |

| Out of the labour force | 23Note * | 28 | 15 | 14 | 20Note E: Use with caution | Note F: too unreliable to be published | Note F: too unreliable to be published | 19Note E: Use with caution | 27Note * | 34Note * | 19 | 17Note E: Use with cautionNote * | 2Note E: Use with caution | 6Note E: Use with caution | 10 |

| Place of residence | |||||||||||||||

| Urban | 39 | 32Note * | 16Note * | 14 | 8Note E: Use with caution | Note F: too unreliable to be published | Note F: too unreliable to be published | 14 | 40 | 31Note * | 22 | 7Note E: Use with caution | 4Note E: Use with caution | 6Note E: Use with caution | 9 |

| Rural (reference category) | 49 | 7Note E: Use with caution | 6Note E: Use with caution | 10Note E: Use with caution | 11Note E: Use with caution | Note F: too unreliable to be published | Note F: too unreliable to be published | 24Note E: Use with caution | 47 | 17Note E: Use with caution | 17Note E: Use with caution | 9Note E: Use with caution | Note F: too unreliable to be published | Note F: too unreliable to be published | 12Note E: Use with caution |

|

E use with caution F too unreliable to be published

Source: Statistics Canada, Aboriginal Peoples Survey, 2012. |

|||||||||||||||

Working-age adults (31%) were more likely than older adults (20%Note E : use with caution) to identify location as barrier. For gathering wild plants or berries, the predominant reason was not having enough time (41%). About three in ten (29%) reported location as a barrier to gathering. Other reasons were reported by one in ten or less. Core working-age adults (44%) were more likely than older adults (29%Note E : use with caution) to cite time as a barrier to gathering (Table 3). Not having someone to teach the skills needed was more likely to be identified as a barrier by youth and young adults (24%) and working-age adults (22%) than older adults (13%Note E : use with caution). Older adults (26%Note E : use with caution) were several times more likely to cite poor health or disability as a barrier than working-age adults (4%Note E : use with caution).

Given that the off-reserve First Nations population is mostly urban, the reasons for non-participation were broken down by place of residence – urban and rural. Significant differences in monetary and location barriers emerged between those living in urban and rural areas (Table 3). As expected, location was more frequently cited among urban off-reserve First Nations people (32%) as a barrier to hunting, fishing or trapping than those living in rural areas (7%Note E : use with caution). Urban dwellers (16%) were more likely to cite monetary reasons for not hunting, fishing or trapping than rural dwellers (6%Note E : use with caution).

Do employed, unemployed and out-of-the-labour-force individuals face different challenges to participating in hunting, fishing or trapping? As expected, employed off-reserve First Nations people (54%) were more likely to face time constraints than unemployed (27%Note E : use with caution) or out-of-the-labour-force people (23%) (Table 3). Unemployed people (22%Note E : use with caution) were more likely to cite not having enough money for equipment or supplies as the reason for not hunting, fishing or trapping than those employed (13%) or out of the labour force (15%). Interestingly, unemployed people (21%Note E : use with caution) were nearly twice as likely to report not having someone to hunt, fish or trap with as a barrier as employed people (11%). A similar trend for those citing location as a barrier was evident (39% for unemployed and 26% for employed). For gathering wild plants or berries, as with hunting, fishing or trapping, employed (53%) individuals were more likely than the unemployed (23%Note E : use with caution) or out-of-the-labour-force individuals (27%) to say time constraints prevented them from taking part in these activities.

When examining family type, female lone-parent families (22%) were significantly more likely to report monetary reasons for not hunting, fishing or trapping than couple-headed families with (13%) or without children (8%Note E : use with caution) (Table 3). They were also more likely to cite not having anyone to do it with (21%) when compared couple-headed families without (7%Note E : use with caution) and with children (14%Note E : use with caution).

Factors associated with participation in harvesting activities among First Nations people living off reserve: household income and remoteness matter among other factors

Examining socioeconomic and demographic characteristics of those who had and had not participated in harvesting activities offers insight into factors that are correlated with participation. However, it is important to examine associations of each of these factors with participation in the context of other factors. For example, participation varied by age group, and it could be suggested that age is a factor for participation. Yet, it is important to investigate if age would remain a factor after accounting for health and household income, for example. To this end, multivariate analysis was carried out using the 2017 APS. This enables an examination of the association of each factor while simultaneously accounting for other factors that could also be associated. Factors included in this analysis were remoteness, the individual’s sex, age group, health, household income (quintiles of household income after tax, adjusted for household size), labour force status, household type and sense of belonging to First Nations culture and activities. These factors were chosen based on previous findings related to harvesting activities among First Nations people, Métis and Inuit and bivariate analysis (data not shown). Other factors, while important, could not be explored here due to data limitations. These include levels of transmission of traditional knowledge, awareness of hunting rights of First Nations people, and changes to policies related to harvesting. Since education and labour force status were considered in this analysis as potential factors, the analysis was restricted to those 25 years or older.

In 2017, after adjusting for other factors, as expected, remoteness of the place of residence was significantly associated with the likelihood of participation. The remoteness index used here is based on proximity to and the size of the population (or service) agglomerations.Note 37 A one unit increase in remoteness was associated with a 3% increase in odds of having hunted, fished or trapped after adjusting for other factors (Table 4). For example, an off-reserve First Nations person living in Edmonton was predicted to be 31% likely to have hunted, fished or trapped. In comparison, in Sioux Lookout, Ontario it was 52%, while in Norman Wells, Northwest Territories, it was 70%.

Sex and age were significantly associated with hunting, fishing or trapping. Off-reserve First Nations men were predicted to be 1.6 times more likely to participate compared with women (Table 4). Older adults were less likely to hunt, fish or trap than core working-age adults. Self-rated health was not significantly associated with participation.

| Predicted marginal (or odds ratioTable 4 Note 1) | 95% confidence interval | Risk ratioTable 4 Note 3 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||

| Remoteness indexTable 4 Note 1 | 1.03Note * | 1.02 | 1.03 | Note ...: not applicable |

| percent | ratio | |||

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 45 | 42 | 49 | 1.56Note * |

| Female (reference category) | 29 | 27 | 31 | 1.00 |

| Adjusted after-tax household income quintilesTable 4 Note 2 | ||||

| Quintile 1 (poorest) | 27 | 22 | 34 | 0.65Note * |

| Quintile 2 | 30 | 26 | 35 | 0.72Note * |

| Quintile 3 | 35 | 32 | 39 | 0.83Note * |

| Quintile 4 | 39 | 36 | 43 | 0.93 |

| Quintile 5 (richest) (reference category) | 42 | 38 | 46 | 1.00 |

| Labour force status | ||||

| Employed (reference category) | 37 | 35 | 40 | 1.00 |

| Unemployed | 36 | 29 | 44 | 0.97 |

| Out of the labour force | 34 | 30 | 38 | 0.91 |

| Age group | ||||

| Working age adults (25-54 years) (reference category) | 38 | 35 | 41 | 1.00 |

| Older adults (55 years or older) | 31 | 28 | 34 | 0.81Note * |

| Health | ||||

| Excellent, very good or good | 37 | 35 | 39 | 1.09 |

| Fair or poor (reference category) | 34 | 30 | 38 | 1.00 |

| Household type | ||||

| Couple-headed family (reference category) | 38 | 36 | 40 | 1.00 |

| Male lone-parent family | 32 | 24 | 41 | 0.84 |

| Female lone-parent family | 29 | 24 | 34 | 0.76Note * |

| Spent time finding out more about First Nations history, traditions and culture |

||||

| Strongly agree | 38 | 35 | 42 | 1.42 |

| Agree | 37 | 34 | 39 | 1.36 |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 38 | 29 | 47 | 1.39 |

| Disagree | 31 | 27 | 36 | 1.15 |

| Strongly disagree (reference category) | 27 | 18 | 38 | 1.00 |

| Active in First Nations organizations, social events or cultural activities |

||||

| Strongly agree | 45 | 40 | 51 | 1.49Note * |

| Agree | 42 | 38 | 45 | 1.37Note * |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 36 | 29 | 43 | 1.17 |

| Disagree | 31 | 28 | 34 | 1.00 |

| Strongly disagree (reference category) | 30 | 25 | 37 | 1.00 |

... not applicable

|

||||

Harvesting activities, and hunting specifically, is an expensive endeavour. The high price of vehicles, equipment and gas impact First Nations peoples’, and in particular women’s, ability to engage in this activity.Note 29 Household income was significantly associated with the likelihood of having hunted, fished or trapped. The likelihood increased with increasing household income (Table 4). Compared to those in the richest income quintile, those in the poorest quintile were 35% (risk ratio=0.65) less likely to hunt, fish or trap. Those in the third quintile were 17% (risk ratio=0.83) less likely to participate compared with those in the richest. However, the likelihood was not significantly different between the fourth and fifth quintiles.

Labour force status was not significantly associated with the likelihood of participating in hunting, fishing or trapping. In initial models of the multivariate analysis, before the inclusion of household type, out-of-the-labour-force individuals were less likely than employed individuals to hunt, fish or trap (appendix Table A.1).

Household type or composition may influence the likelihood of participation in harvesting activities. Previous studies have suggested that children in lone-parent families were less likely to participate in hunting or fishing than those in couple-headed families.Note 38 Previously, among female heads of households in two First Nations communities, the odds of harvesting was significantly lower compared with their male counterparts.Note 3 In the current analysis, a similar finding emerged (Table 1). Those in female lone-parent households were less likely than those in couple-headed households (reference category) to engage in hunting, fishing or trapping.

Sense of belonging to First Nations culture and identity was assessed using several questions in the 2017 APS. Two measures of sense of belonging were examined in this analysis, namely having spent time trying to find out more about First Nations history, traditions, and culture; and being active in First Nations organizations, social events or cultural activities. The former was not associated with hunting, fishing or trapping while the latter was. Participation in hunting, fishing or trapping appeared to increase with being active in First Nations organizations, social events or cultural activities.

In another multivariate analysis, the association between socioeconomic and demographic factors and participation in gathering wild plants or berries among First Nations people living off reserve was examined (data not shown). As with hunting, fishing or trapping, remoteness of place of residence was associated with gathering. In contrast to hunting, fishing or trapping, men were less likely to participate than women. Also, age group and household income were not associated unlike that seen for hunting, fishing or trapping. Interestingly, off-reserve First Nations people who were unemployed were more likely to gather than those employed. Family type was associated with gathering wild plants or berries. Those in lone-parent households were less likely than couple-headed families to engage in gathering. Finally, those who were active in First Nations people organizations, social events or cultural activities, and those who had spent time trying to find out more about First Nations history, traditions and culture were more likely to gather wild plants or berries than their counterparts.

Discussion

Based on four cycles of APS data, the prevalence of hunting, fishing or trapping among off-reserve First Nations people showed a 10% decline between 2006 and 2017. While no significant downward or upward trend was seen in any age group, among youth and young adults, prevalence in 2017 was lower than in 2006 and 2012. Previously, among First Nations adults living on reserve across Canada, a decline of 43% for hunting and trapping and 33% for fishingNote 33 was observed from 2002/03 to 2015/16. The demographic and socioeconomic characteristics of the off-reserve First Nations population from each of the APS cycles provide some potential reasons for the decrease in prevalence of hunting, fishing or trapping in 2017. While no notable changes in proportion of urban dwellers was evident, there was an increase in education levels particularly post-secondary education below a bachelor’s level. It is possible that school attendance may have imposed time constraints resulting in less time to devote to harvesting, as has been seen among their on-reserve counterparts, particularly young adults.Note 3 It should be noted that higher levels of education completion may facilitate and hinder participation in harvesting activities. Higher levels of education is associated with being employed, which provides the financial means to harvest, but limits the time available for this activity. Other factors could also be implicated. The demands of family life, lack of interest and rising costs of hunting, fishing or trapping have been previously identified.Note 3

The self-reported barriers among youth and young adults add to the findings from the socioeconomic and demographic profile. The leading reasons for non-participation in this group were: not having enough time, location, no one to do it with and not having enough money for equipment or supplies. Previously among 20-to-39-year-old individuals, including First Nations people living in two reserve communities, not having enough time due to employment, lack of knowledge or interest and cost were the leading barriers to harvesting.Note 3 In the current analysis, the barriers of location and not having someone to partake in this activity are not unexpected given that these were reported by those living off reserve. Finding others who are interested and with harvesting skills and knowledge may be limited in urban areas where most off-reserve First Nations people live. However, many off-reserve First Nations people sometimes harvest on reserve in their communities.Note 39 Importantly, the common barriers of time and expense allude to their pervasiveness among First Nations people living on and off reserve.

While financial costs were not a leading barrier, it was more likely to be cited by the unemployed (compared with employed) and those in female lone-parent households (compared with couple-headed households). This is supported by the multivariate findings. Household income was significantly associated with hunting, fishing or trapping.

These results together provide some understanding of how the pressures of the wage economy and education, inadequate financial resources and family responsibilities intersect and could potentially affect participation in harvesting activities among First Nations people living off reserve.

Location was the second leading concern among First Nations people living off reserve. Harvesting areas may be located at a considerable distance away from urban areas. This is supported by the findings that location was about five times more likely to be reported as a barrier among those living in urban areas than rural areas.

The multivariate findings also suggest potential facilitators, or factors that are associated with increased participation. Specifically, being active in First Nations organizations, social events or cultural activities. The likelihood of participation increased with engagement in the above activities.

It should be noted that other previously-identified barriers could not be explored in this paper due to data limitations. The lack of or inadequate knowledge has been identified as a barrierNote 40 among First Nations people living on reserve. This could be a barrier among those living off reserve as well. However, data on this was not collected in the APS. Data on barriers relating to school attendance, and childcare responsibilities, which have been previously identified,Note 3 was also not collected.

These findings could inform tailored programs to reduce barriers and increase participation in harvesting activities among First Nations people living off reserve. Among youth and young adults, in addition to the leading barrier of time, factors such as location, having no one to harvest with and money were also identified. Organized harvesting activities or community hunts, similar to those that occur in many First Nations reserves,Note 41Note 42 could address some of these barriers off reserve as well. On many reserves, community hunts are also important for nutrition, knowledge transmission and decreasing inequities in availability of country food among elders, single mothers and others in need.Note 42Note 43 They may have similar benefits among First Nations people living off reserve. Findings on sociodemographic characteristics of non-participants who expressed interest in participation could inform tailored initiatives. For example, unemployed individuals were likely that employed or out-of-the-labour-force individuals to express interest in harvesting activities.

Harvesting activities among Métis

To date, there has been limited research on harvesting activities among Métis. Historically, Métis have engaged in hunting, fishing and trapping, and played a prominent role in the fur trade beginning in the latter half of the 1700s.Note 44Note 45 The semi-annual, large-scale Métis buffalo hunts in the 19th century are a part of Métis history and has been documented extensively.Note 44Note 46 To many Métis, harvesting activities are an integral part of Métis way of life and identity. In fact, hunting, fishing or trapping has been suggested to be one of the historical factors that impacted Métis identity.Note 47 Métis continue to engage in harvesting activities today. In 2006, fishing was found to be the most prevalent harvesting activity among Métis followed by gathering wild plants and hunting.Note 11 However, there is little other research on contemporary Métis harvesting activities or long-term trends in harvesting activities.

The challenges to participation in harvesting activities faced by Métis have not been explored sufficiently in previous literature with the exception of the social and political barriers.Note 46Note 48Note 49 For example, Métis were often stripped of hunting and trapping rights.Note 46 It is also expected that the pressures of the wage economy, socio-demographic changes and the impacts of residential school affect participation in harvesting activities. Several Métis children attended church-run boarding schools or other residences funded by the federal or provincial governments in the 20th century.Note 46 Residential school attendance has been associated with several negative health outcomes among Métis,Note 22 both directly and indirectly through socio-economic and community level factors.Note 23

This section explores trends in participation in hunting, fishing or trapping and gathering wild plants or berries using four cycles of the Aboriginal People Survey. It also examines factors associated with participation, and reasons for participation and non-participation among Métis aged 15 years or older.

A potential declining trend in hunting, fishing or trapping among Métis youth and young adults

Studies of trends in harvesting activities among Métis are few. In 2015, the Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources, Government of Northwest Territories published trends in hunting and fishing among Dene/Métis in the territory. These suggested that prevalence of hunting or fishing for subsistence had changed little from 1983 to 1993 (about 30%).Note 50 Trends including estimates for more recent years have yet to be published. In this section, using the 2001, 2006, 2012 and 2017 APS cycles, trends in participation in harvesting activities among Métis are examined.

Among Métis aged 15 or older, the prevalence of hunting, fishing or trapping was lower in 2012 and 2017 than in 2001 and 2006. The prevalence in 2017 (35%) represented a 19% decrease compared with the 2006 level (44%). However, the prevalence in the latest two cycles (2012 and 2017) were not significantly different from each other. No significant changes in prevalence was seen for gathering wild plants or berries over the four cycles (data not shown).

Among the three age groups, the prevalence of hunting, fishing or trapping was consistently lower among those 55 years or older (older adults) compared to the others (Chart 5). Among youth and young adults (aged 15 to 24), a significant downward trend was apparent after 2006. Prevalence decreased from 46% in 2006 to 38% in 2012 and 33% in 2017. However, when compared with 2001 levels, no downward trend was observed.

Data table for Chart 5

| Age group | 2001 | 2006 | 2012 | 2017 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percent | 95% confidence interval | Percent | 95% confidence interval | Percent | 95% confidence interval | Percent | 95% confidence interval | |||||

| Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | |||||

| 15 to 24 years | 40 | 37 | 43 | 46 | 44 | 49 | 38 | 35 | 42 | 33 | 31 | 36 |

| 25 to 54 years | 43 | 42 | 45 | 46 | 44 | 47 | 39 | 36 | 41 | 39 | 37 | 41 |

| 55 years or older | 32 | 28 | 36 | 34 | 31 | 37 | 29 | 26 | 33 | 30 | 29 | 32 |

| Sources: Statistics Canada, Aboriginal Peoples Survey, 2001, 2006, 2012 and 2017. | ||||||||||||

Youth and young adults were less likely to have participated in the gathering of wild plants or berries over most cycles when compared to other age groups (Chart 6). Little variation between cycles was seen in any age group.

Data table for Chart 6

| Age group | 2001 | 2006 | 2012 | 2017 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percent | 95% confidence interval | Percent | 95% confidence interval | Percent | 95% confidence interval | Percent | 95% confidence interval | |||||

| Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | |||||

| 15 to 24 years | 20 | 17 | 22 | 25 | 23 | 27 | 20 | 17 | 22 | 19 | 17 | 21 |

| 25 to 54 years | 30 | 29 | 32 | 32 | 31 | 34 | 30 | 28 | 33 | 28 | 27 | 30 |

| 55 years or older | 32 | 29 | 36 | 26 | 24 | 29 | 33 | 29 | 37 | 30 | 28 | 32 |

| Sources: Statistics Canada, Aboriginal Peoples Survey, 2001, 2006, 2012 and 2017. | ||||||||||||

Males were consistently more likely to hunt, fish or trap than females, however both males and females exhibited similar trends over time (data not shown). Prevalence of gathering wild plants or berries was not significantly different across cycles. And, the trends in both sexes remained relatively unchanged across cycles. While the prevalence of gathering wild plants or berries was higher among Métis women compared with men in some cycles, in others, no significant differences emerged.

Métis in rural areas were consistently more likely to hunt, fish or trap and gather wild plants or berries than those in urban areas. Prevalence of hunting, fishing or trapping in urban areas in 2012 and 2017, while not significantly different from rural areas, was lower in 2006 (data not shown). Regarding gathering of wild plants or berries, no significant differences across cycles were evident.

Trends in potentially influencing factors

Changes in factors such as urbanization, engagement in the wage economy, socio-political environment, demographic changes may have influenced the trends in harvesting activities, and harvesting trends should be examined in the context of these changes.

Despite its youthful structure, the Métis population has been getting somewhat older. This is clearly evident with the increase in median age of the Métis population (Chart 7). Among those aged 15 years or older, the median age increased from 36 to 42 years from 2006 to 2017. And, the proportions of 15-to-24-year-olds, 25-to-34-year-olds and 35-to-44-year olds decreased, and the proportion of adults 55 years or older increased.

Data table for Chart 7

| Socioeconomic and demographic characteristics | 2001 | 2006 | 2012 | 2017 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percent | 95% confidence interval | Percent | 95% confidence interval | Percent | 95% confidence interval | Percent | 95% confidence interval | |||||

| Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | |||||

| Age | ||||||||||||

| 15 to 24 years | 26 | 24 | 27 | 22 | 21 | 24 | 22 | 21 | 24 | 20 | 20 | 21 |

| 25 to 34 years | 21 | 19 | 22 | 19 | 18 | 20 | 18 | 17 | 19 | 17 | 16 | 19 |

| 35 to 44 years | 23 | 22 | 24 | 21 | 20 | 22 | 17 | 16 | 18 | 16 | 15 | 17 |

| 45 to 54 years | 17 | 16 | 18 | 19 | 18 | 20 | 19 | 18 | 21 | 19 | 18 | 20 |

| 55 to 64 years | 9 | 8 | 10 | 11 | 10 | 12 | 14 | 13 | 15 | 17 | 16 | 17 |

| 65 years or older |

5 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 6 | 8 | 9 | 8 | 10 | 11 | 11 | 12 |

| Median age of 15+ population (years) | 36 | 35 | 36 | 38 | 38 | 39 | 39 | 39 | 40 | 42 | 41 | 43 |

| Education | ||||||||||||

| Less than high school | 34 | 33 | 36 | 29 | 28 | 30 | 21 | 20 | 23 | 15 | 14 | 16 |

| High school | 16 | 15 | 17 | 16 | 15 | 17 | 18 | 16 | 19 | 16 | 15 | 17 |

| Post-secondary education below bachelor's level | 44 | 43 | 46 | 45 | 43 | 46 | 50 | 48 | 52 | 56 | 55 | 57 |

| University or higher |

6 | 5 | 6 | 10 | 9 | 11 | 11 | 10 | 12 | 13 | 11 | 14 |

| Labour force status | ||||||||||||

| Employment rate | 64 | 62 | 65 | 67 | 66 | 69 | 64 | 62 | 66 | 64 | 63 | 65 |

| Unemployment rate | 12 | 11 | 13 | 8 | 7 | 9 | 10 | 8 | 12 | 9 | 8 | 10 |

| Not in the labour force | 28 | 26 | 29 | 27 | 26 | 28 | 29 | 28 | 31 | 30 | 29 | 31 |

| Geography | ||||||||||||

| Urban | 70 | 69 | 71 | 71 | 70 | 73 | 74 | 73 | 76 | 72 | 71 | 73 |

| Rural | 29 | 28 | 30 | 28 | 27 | 30 | 26 | 24 | 27 | 28 | 27 | 29 |

| Sources: Statistics Canada, Aboriginal Peoples Survey, 2001, 2006, 2012 and 2017. | ||||||||||||

The education profile of the Métis population has been steadily improving as seen by the decreasing proportions of those with less than a high school education, and increasing proportions of those with post-secondary education (Chart 7). The labour market profile has changed somewhat over the cycles. The employment rate remained relatively unchanged, but the unemployment rate decreased after 2001 but increased in 2012. The proportion of those not in the labour force increased after 2006 and remained unchanged in the subsequent two cycles. However, it is important to note that these rates are a snapshot in time and reflect the economic conditions at the time of the survey. Year-by-year analysis has previously show that there are significant fluctuations in rates over time among Métis.Note 34 In terms of place of residence, the Métis population has remained predominantly urban (roughly 70%) with little variability. While examination of these characteristics suggests factors that may have influenced the trends, it is important to note that the statistical associations between these characteristics and the trends in participation were not explored in this report.

Métis primarily participate in harvesting for own use

Self-reported reasons for participation and non-participation in harvesting activities was examined to better understand the facilitators and barriers to harvesting activities among Métis. Almost all Métis who hunted, fished or trapped did so for pleasure or leisure (90%) or for own or own family’s use (84%). It should be recognized that for many Métis, engagement in harvesting activities is part of their identity and provides opportunities to commune with family and community.Note 36 In interpreting the findings for pleasure or leisure, it is important to distinguish this from sport hunting, which is often associated with reasons of pleasure and leisure. Three in ten (30%) had engaged in this activity to share the harvest with the community. About one in four (23%) had done it for cultural reasons. Three percent had done it for money or supplement their income.

Almost all Métis who had gathered wild plants or berries did so for own use or own family’s use (95%), while three fourths did so for pleasure or leisure (78%). About four in ten (44%) participated to share with the community and one in three for cultural reasons (33%). Lastly, four percent gathered wild plants or berries for monetary reasons.

Why Métis hunt, fish or trap varies by socioeconomic and demographic factors

Reasons for harvesting are expected to vary by socioeconomic and demographic factors, and could inform tailored programs and policies to support harvesting. Also, specifically, it can identify Métis who are more likely to share their harvest with others in the community. This may have implications for nutrition and food security. With this in mind, self-reported reasons were broken down by socioeconomic and demographic factors using data from the 2017 APS.

Youth and young adults (77%) were less likely to hunt, fish or trap for own use or own family’s use than core working-age adults (85%) or older adults (88%) (Table 5). Those in rural areas (89%) were more likely to participate for this reason compared with those in urban areas (81%). Unemployed Métis (40%) were more likely to hunt, fish or trap to share with others in the community than employed Métis (28%). Those in rural areas (35%) were also more likely to report this reason than those in urban areas (27%). Youth and young adults (15%) were less likely than working-age adults (24%) and older adults (26%) to hunt, fish or trap for cultural reasons. Those in rural areas (27%) were more likely to do so than those in urban areas (20%). Métis males (3%) were three times as likely to hunt, fish or trap for money or to supplement income as females (1%Note E : use with caution). Unemployed individuals (7%Note E : use with caution) were also more likely to engage in these activities for the same reason than employed (2%Note E : use with caution) or out-of-the-labour-force individuals (3%Note E : use with caution). This trend was also observed between Métis in rural areas (5%Note E : use with caution) compared with those in urban areas (1%Note E : use with caution). Such patterns did not always emerge for gathering wild plants or berries.

| Reasons for hunting, fishing or trapping in the previous 12 months | Reasons for gathering wild plants or berries in the previous 12 months | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| For pleasure or leisure | Own use/family’s use | To share with others in the community | For cultural reasons | For money or to supplement income | For some other reason | For pleasure or leisure | Own use/family’s use | To share with others in the community | For cultural reasons | For money or to supplement income | For some other reason | |

| percent | ||||||||||||

| Sex | ||||||||||||

| Males | 91 | 85 | 33Note * | 24 | 3Note * | 9 | 75Note * | 94 | 45 | 34 | 4Note E: Use with caution | 9 |

| Females (reference category) | 89 | 82 | 25 | 21 | 1Note E: Use with caution | 8 | 81 | 95 | 44 | 32 | 4 | 11 |

| Age group | ||||||||||||

| 15 to 24 years | 90 | 77Note * | 29 | 15Note * | 2Note E: Use with caution | 9 | 81 | 92 | 47 | 21Note * | 3Note E: Use with caution | 13Note E: Use with caution |

| 25 to 54 years (reference category) | 90 | 85 | 28 | 24 | 3Note E: Use with caution | 8 | 79 | 95 | 44 | 34 | 3Note E: Use with caution | 8 |

| 55 years or older | 90 | 88 | 34Note * | 26 | 4Note E: Use with caution | 9 | 75 | 96 | 43 | 36 | 4Note E: Use with caution | 12Note * |

| Labour force status | ||||||||||||

| Employed (reference category) | 91 | 84 | 28 | 23 | 2Note E: Use with caution | 9 | 79 | 95 | 44 | 32 | 3Note E: Use with caution | 9 |

| Unemployed | 82Note * | 81 | 40Note * | 26 | 7Note E: Use with cautionNote * | Note F: too unreliable to be published | 71 | 98Note * | 52 | 33 | Note F: too unreliable to be published | 9Note E: Use with caution |

| Out of the labour force | 88 | 84 | 32 | 21 | 3Note E: Use with caution | 6Note * | 77 | 95 | 44 | 35 | 5Note E: Use with cautionNote * | 12 |

| Place of residence | ||||||||||||

| Urban | 91Note * | 81Note * | 27Note * | 20Note * | 1Note E: Use with cautionNote * | 9 | 80Note * | 94 | 44 | 33 | 2Note E: Use with cautionNote * | 12Note * |