Youth court statistics in Canada, 2010/2011

Archived Content

Information identified as archived is provided for reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It is not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards and has not been altered or updated since it was archived. Please "contact us" to request a format other than those available.

By Shannon Brennan

- Number of cases completed in youth court declines for second year in a row

- Majority of cases completed in youth court involve non-violent offences

- Older youth most likely to appear in court

- Proportion of youth court cases resulting in an outcome of guilt continues to decline

- Cases involving property and violent offences result in guilty findings less often than other cases

- Probation most common sentence imposed by youth courts

- Fewer youth sentenced to custody

- Time taken to complete cases in youth court has increased over past 10 years

- Summary

- Data Sources

- Detailed data tables

- References

- Notes

In Canada, youth and adults accused of crimes have been governed by separate justice systems for over a century. From the introduction of the Juvenile Delinquents Act in 1908, to the Young Offenders Act in 1984, to the Youth Criminal Justice Act (YCJA) enacted in 2003, it has been long acknowledged that the principles of justice that apply to adults are not necessarily suitable for youth (Casavant et al. 2008).

Attitudes surrounding youth and their involvement in Canada's justice system have transformed and evolved over many years. Under the current legislation, the Youth Criminal Justice Act, emphasis is placed on attempting to divert youth (ages 12 to 17) accused of minor, non-violent offences away from the formal court system through the use of diversionary and extrajudicial measures. These measures are meant to provide timely and meaningful consequences for youth while avoiding the stigma attached to formal involvement in the justice system (Department of Justice Canada 2011).

Although the number of cases completed in youth court has decreased since the implementation of the YCJA, many youth do still come into contact with the formal justice system (Milligan 2010). Statistics Canada collects information on youth court cases through the Integrated Criminal Court Survey (ICCS).

Using data from the youth component of the 2010/2011 ICCS, this Juristat article examines trends in youth court cases.Note 1 More specifically, it looks at the number and types of cases completed at the national, territorial and provincial levels, and the characteristics of youth appearing in court. Further, the article examines case decisions, trends in sentencing, and the length of time taken to complete a case.

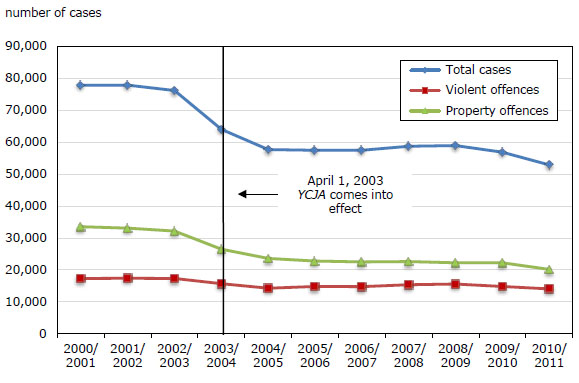

Number of cases completed in youth court declines for second year in a row

In 2010/2011, the number of cases completed in youth court declined for the second year in a row, down 7% from the previous year (Table 1). Overall, there were more than 52,900 cases completed in youth court in 2010/2011, involving over 178,000 Criminal Code and other federal statute offences.

The number of cases completed in youth court has declined considerably (-32%) over the past decade. The most notable decreases occurred in 2003/2004 and 2004/2005, the two years following the implementation of the YCJA (Chart 1).

Chart 1

Cases completed in youth court, Canada, 2000/2001 to 2010/2011

Note: A case is one or more charges against an accused person or company that were processed by the courts at the same time and received a final disposition. Total cases include violent offences, property offences, administration of justice offences, other Criminal Code offences, Criminal Code traffic offences and other federal statutes.

Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Centre for Justice Statistics, Integrated Criminal Court Survey.

Almost every province reported a decline in youth court cases in between 2009/2010 and 2010/2011.Note 2 The largest decrease was seen in Nova Scotia, down 15% from the previous year, followed by Prince Edward Island (-13%) and Alberta (-11%). Manitoba was the only province to report an increase in youth court cases in 2010/2011 (+3%) (Table 2). Overall, Saskatchewan recorded the highest rate of completed youth court cases, as has been the case since 1994/1995.

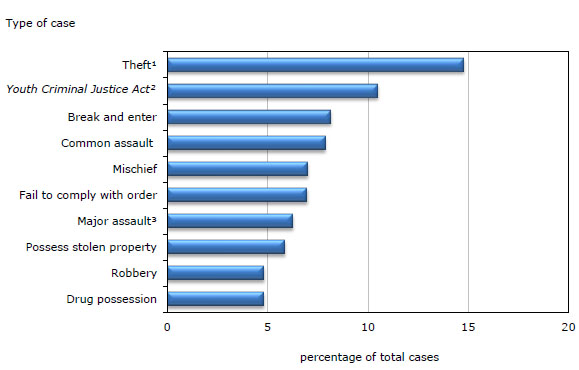

Majority of cases completed in youth court involve non-violent offences

The majority of cases completed in youth court in 2010/2011 involved non-violent offences.Note 3 More specifically, property offences, administration of justice offences, other Criminal Code offences, traffic offences and other federal statute offences (e.g., drug offences) accounted for close to three-quarters (73%) of cases completed in youth court. Violent offences accounted for the remaining 27% of youth court cases.

As in previous years, there were 10 offences that comprised the majority (78%) of youth court cases in 2010/2011 (Chart 2). The most common types of cases completed in youth court were theft (15%), Youth Criminal Justice Act offences (e.g., failure to comply with a sentence, failure to comply with a designated temporary place of detention) (11%), and break and enter (8%).

Chart 2

Ten most common cases completed in youth court, Canada, 2010/2011

1. Includes, for example, theft over and under $5,000 as well as taking a motor vehicle without consent.

2. Includes the offences of inducing a young person, failure to comply with a sentence or disposition, publishing the identity of offenders, victims or witnesses and failure to comply with a designated place of temporary detention.

3. Includes, for example, assault with a weapon (level 2) and aggravated assault (level 3).

Note: A case is one or more charges against an accused person or company that were processed by the courts at the same time and received a final disposition. Cases that involve more than one charge are counted according to the most serious offence.

Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Centre for Justice Statistics, Integrated Criminal Court Survey.

In 2010/2011, the decline in the number of completed youth court cases occurred across all major offence categories (Table 3). For example, cases involving violent offences declined by 5% from the previous year, and included decreases in uttering threats (-12%), and major assault (-7%). Despite the overall decline in youth court cases involving violent offences, there were some increases among individual offence types, most notably in cases involving criminal harassment, up by 13% from the previous year.

Cases involving property offences also declined in 2010/2011, down 9% from the previous year. Decreases were seen for all property offences, with the greatest declines occurring among cases involving fraud (-25%) and mischief (-13%).

Criminal Code administration of justice cases, such as failure to comply with an order, also decreased in 2010/2011; however, the decrease did not occur across all offence types. For example, completed cases involving breach of probation and failure to appear both increased, up 7% and 3% respectively.

Cases involving Criminal Code traffic offences showed the greatest decline, decreasing by 16% from 2009/2010. Conversely, cases involving other federal statute offences (e.g., drug possession) showed the smallest decline at 2%.

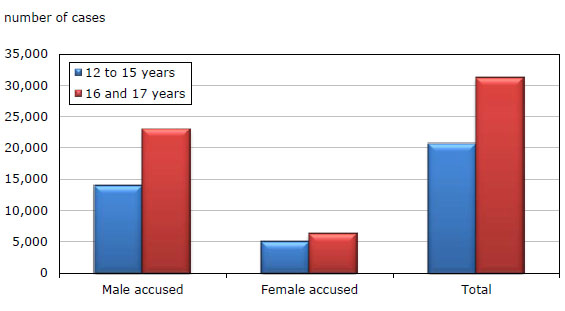

Older youth most likely to appear in court

Police-reported data show that youth and young adults tend to be disproportionately accused of crime. In general, rates of offending increase incrementally among those 12 to 17, with rates peaking among 18 year olds (Brennan and Dauvergne 2011). Data from Canada's youth courts show a similar trend, despite the fact that not all crimes that come to the attention of police necessarily proceed to court. Overall, youth court cases were more likely to involve older youth (ages 16 and 17), compared to younger youth (12 to 15 years old).Note 4, Note 5 This was true among both males and females (Chart 3).

Chart 3

Cases completed in youth court, by age group and sex of accused, Canada, 2010/2011

Note: A case is one or more charges against an accused person or company that were processed by the courts at the same time and received a final disposition. Age represents the age of the accused at the time of the offence. Excludes cases in which the age and/or the sex of the accused was unknown.

Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Centre for Justice Statistics, Integrated Criminal Court Survey.

While older youth were the accused in most completed cases, this varied somewhat depending on the type of case. For example, impaired driving (96%) and prostitution-related cases (93%) predominantly involved youth aged 16 or 17. Conversely, sexual assault and other sexual offences cases were more likely to involve youth aged 12 to 15 (65% and 60% respectively).

As is the case with crime in general, the majority of youth court cases completed in 2010/2011 involved a male accused. More specifically, cases involving male accused accounted for 77% of the youth court caseload, while those involving females accounted for the remaining 23%.Note 6

Regardless of the type of case, males were consistently more likely than females to be the accused. Cases with the highest representation of males included: sexual assault (98%), attempted murder (96%), and other sexual offences (95%). Cases with the highest representation of females included common assault (37%), theft (37%) and fraud (35%).

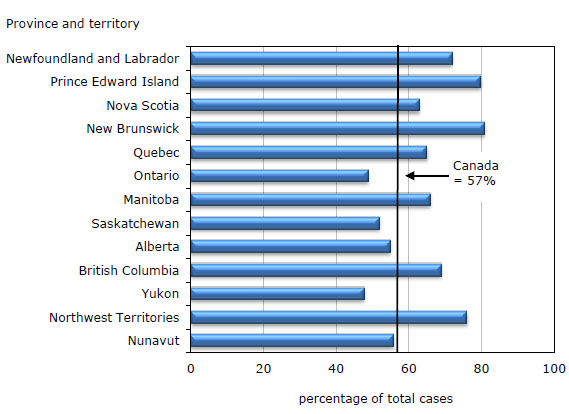

Proportion of youth court cases resulting in an outcome of guilt continues to decline

Previous studies have shown that in general, youth court cases typically result in one of three outcomes. The first and most common is a guilty outcome, where the accused youth pleads guilty or is found guilty for having committed a criminal offence. The second outcome is a stay/withdrawal or dismissal, in which the court stops or interrupts proceedings against the accused. Finally, youth court cases may result in an acquittal,Note 7 where the youth is found not guilty of the charges presented before the court.Note 8

In 2010/2011, over one-half (57%) of youth court cases resulted in a guilty outcome, while an additional 42% of cases were stayed, withdrawn or dismissed. Similar to previous years, few cases completed in youth court were acquitted (1%), while another 1% resulted in another type of decision, such as the accused being found not criminally responsible or unfit to stand trial (Table 4).

Over the past 10 years, youth courts have seen a shift in youth court decisions, with the proportion of cases resulting in guilty outcomes decreasing, and those being stayed or withdrawn increasing. For example, in 2000/2001, 67% of cases resulted in a decision of guilt, compared to 57% of cases in 2010/2011. Conversely, the proportion of cases being stayed or withdrawn increased from 31% in 2000/2001 to 42% in 2010/2011.

This shift in youth court decisions may be related in part to the introduction of extrajudicial measures under the YCJA. As more youth are being dealt with through the use of diversionary and extrajudicial measure programs, fewer cases (and charges) are proceeding to youth court. Studies have shown that youth court cases are more likely to result in a guilty finding when there are multiple charges (Moyer 2005). Further, the increased use of extrajudicial measures may also impact the proportion of cases being stayed or withdrawn. In general, charges are stayed or withdrawn upon successful completion of extrajudicial sanctions (Public Prosecution Service of Canada 2004).

There was considerable variation among the provinces and territories in regards to youth court outcomes.Note 9 The proportion of youth court cases resulting in guilty outcomes ranged from 81% in New Brunswick, to 49% in Ontario (Chart 4). This variation may be partly related to the use of pre-charge screening, where a Crown prosecutor (as opposed to police) determines whether a charge is officially laid and proceeds to court. New Brunswick, Quebec and British Columbia, all have pre-charge screening systems in place. In all three provinces, the proportion of youth court cases resulting in a finding of guilt exceeded the national average.

Chart 4

Guilty cases in youth court, by province and territory, 2010/2011

Note: A case is one or more charges against an accused person or company that were processed by the courts at the same time and received a final disposition. Jurisdictional differences in the structure and operation of courts may have an impact on survey results. Therefore, any comparisons between jurisdictions should be made with caution.

Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Centre for Justice Statistics, Integrated Criminal Court Survey.

Cases involving property and violent offences result in guilty findings less often than other cases

Cases involving particular types of offences were more likely to result in a guilty finding compared with others. Of the major offence categories, cases involving violent and property offences were among the least likely to result in a decision of guilt (57% and 48% respectively), while cases involving Criminal Code traffic offences were the most likely (82%) (Table 4).

Among the individual offence types, cases for youth being unlawfully at large were found guilty most often (90%), followed by impaired driving cases (86%), and offences under the YCJA (82%). Conversely, drug possession cases were the least likely to end with a decision of guilt (34%).

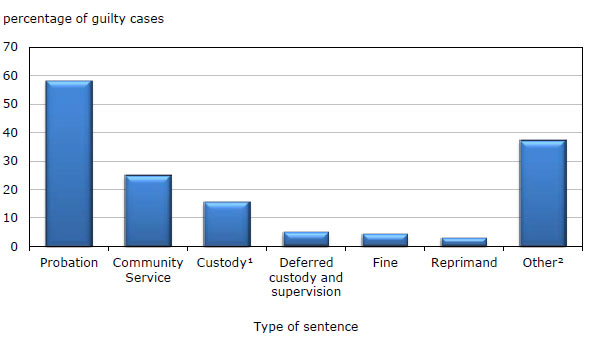

Probation most common sentence imposed by youth courts

In general, the purpose of sentencing is to hold youth accountable for the offence committed. Under the YCJA, judges must consider sentences that will have meaningful consequences for the youth and promote the youth's rehabilitation and reintegration into society. Further, the sentence should also take into consideration the long-term protection of the public (Justice Canada 2011). Given the complexities of determining an appropriate sentence, many youth court cases result in more than one type of sanction (e.g., probation and community service order).

Similar to previous years, probation was the most common type of sentence imposed by youth courts in 2010/2011 (Chart 5, Table 5). A form of community-based sentence, youth on probation are placed under supervision of a probation officer or other designated officer, and must abide by a number of conditions imposed by the court (e.g., keep the peace, appear in court as required). Overall, more than one-half (58%) of guilty youth court cases were given a sentence of probation, either as a single sentence or in combination with another sentence.

Chart 5

Guilty cases in youth court, by type of sentence, Canada, 2010/2011

1. Figures for custody include a mandatory period of post-custody supervision.

2. Other sentences include absolute discharge, restitution, prohibition, seizure, forfeiture, compensation, pay purchaser, essays, apologies, counseling programs and conditional discharge.

Note: Cases may involve more than one type of sentence, therefore, percentages do not total 100%. A case is one or more charges against an accused person or company that were processed by the courts at the same time and received a final disposition. Other sentences imposed by not shown include: conditional sentences, intensive support and supervision, and attending a non-residential program.

Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Centre for Justice Statistics, Integrated Criminal Court Survey.

Under the YCJA, youth can be sentenced to probation for a maximum of two years. As in previous years, in 2010/2011 the median length of probation sentences imposed was 365 days (Table 5).Note 10

Community service orders were another relatively common sentence imposed by youth courts in 2010/2011. Overall, 1 in 4 guilty youth court cases resulted in the youth having to perform unpaid work for the community. The provisions of the YCJA stipulate that sentences of community service may not exceed 240 hours and must be completed within one year.

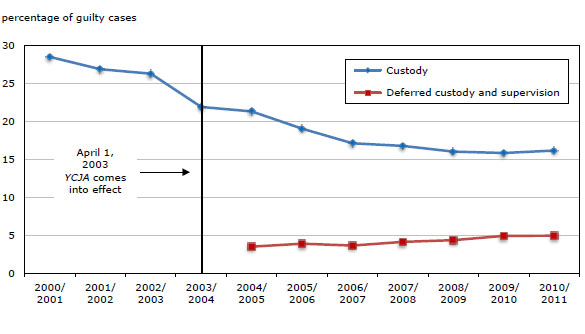

Fewer youth sentenced to custody

Custodial sentences, in which youth are detained in a correctional facility, are viewed as the most serious of all available sentencing options. Under the YCJA, all reasonable alternatives to custody must be considered before a judge may impose a custodial sentence. On the whole, custodial sentences for youth are meant to be used primarily for violent and serious repeat offenders (Justice Canada 2011).

In 2010/2011, 16% of guilty youth court cases were sentenced to custody. Consistent with the objectives of the YCJA, the use of custody has decreased over the past 10 years (Chart 6). More specifically, the proportion of guilty youth court cases being sentenced to custody fell from 29% in 2000/2001 to 16% in 2010/2011. Conversely, the use of deferred custody and supervision orders has increased slightly since being introduced in 2003.Note 11 Seen as an alternative to custody, deferred custody orders allow a young person who would otherwise be sentenced to custody to serve their sentence in the community under a set of strict conditions. If these conditions are violated, the young person may be sent to custody to serve the balance of their sentence.

Chart 6

Guilty cases in youth court by selected sentence, 2000/2001 to 2010/2011

Note: A case is one or more charges against an accused person or company that were processed by the courts at the same time and received a final disposition. Deferred custody and supervision is a sentence under the Youth Criminal Justice Act effective April 1, 2003. Includes only those jurisdictions for which YCJA sentencing data was available as of 2004/2005: Prince Edward Island, Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Quebec, Ontario, Alberta, British Columbia, Northwest Territories, Yukon and Nunavut.

Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Centre for Justice Statistics, Integrated Criminal Court Survey.

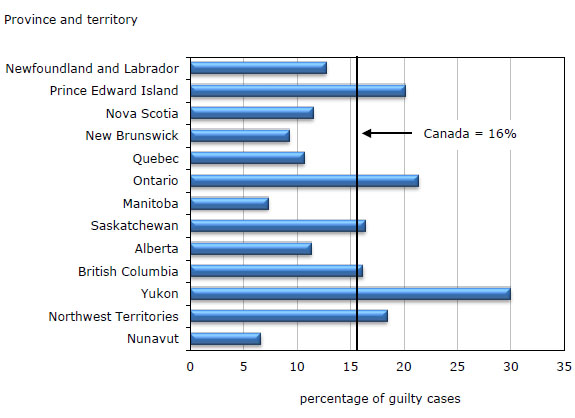

In general, there was wide variation in the use of custody across the provinces and territories (Chart 7).Note 12 Overall, Ontario (21%) and Prince Edward Island (20%) reported the highest use of custody, while Manitoba (7%) and New Brunswick (9%) reported the lowest.

Chart 7

Guilty cases in youth court sentenced to custody, by province and territory, 2010/2011

Note: A case is one or more charges against an accused person or company that were processed by the courts at the same time and received a final disposition. Jurisdictional differences in the structure and operation of courts may have an impact on survey results. Therefore, any comparisons between jurisdictions should be made with caution.

Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Centre for Justice Statistics, Integrated Criminal Court Survey.

In 2010/2011, custodial sentences were ordered primarily for cases involving administration of justice offences and violent offences. More specifically, attempted murder cases and cases where youth were found to be unlawfully at large resulted in custodial sentences most often (Table 5).

In 2010/2011, the median length of custodial sentences imposed by youth courts was just over one month, at 35 daysNote 13 (Table 5). However, the amount of time sentenced to custody varied by type of case, with cases involving violent offences receiving the longest terms of custody. More specifically, homicide cases received the longest custodial sentences at 795 days, followed by attempted murder (575 days), and sexual assault (150 days).

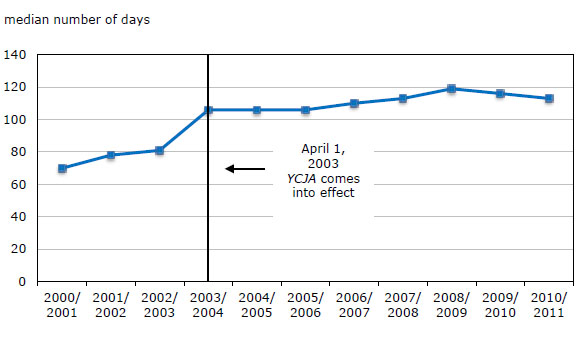

Time taken to complete cases in youth court has increased over past 10 years

In addition to collecting information on the number and types of cases completed in youth court, the ICCS is able to calculate the length of time from the youth's first court appearance to the date the case is completed.

On the whole, the median length of time to process cases in youth court has increased over the past 10 years. In 2010/2011, the median elapsed time to complete a youth court case was 113 days, over a month longer than the median elapsed time of 70 days in 2000/2001 (Table 3). The largest increase in processing times occurred between 2002/2003 and 2003/2004; however, since then, the length of time to process cases in youth court has remained in the range of three and a half months (Chart 8).

Chart 8

Median length of cases completed in youth court, 2000/2001 to 2010/2011

Note: The median represents the mid-point of the number of days taken to complete a case, from the first to last court appearance. A case is one or more charges against an accused person or company that were processed by the courts at the same time and received a final disposition.

Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Centre for Justice Statistics, Integrated Criminal Court Survey.

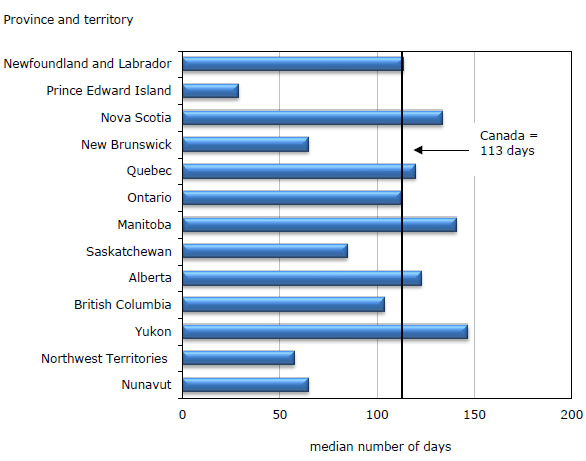

There was considerable provincial and territorial variation in the amount of time taken to process youth court cases in 2010/2011 (Chart 9)Note 14. Among the provinces, median processing times were longest in Manitoba (141 days) and shortest in Prince Edward Island (29 median days).

Chart 9

Median length of cases completed in youth court, by province and territory, 2010/2011

Note: The median represents the mid-point of the number of days taken to complete a case, from the first to last court appearance. A case is one or more charges against an accused person or company that were processed by the courts at the same time and received a final disposition. Jurisdictional differences in the structure and operation of courts may have an impact on survey results. Therefore, any comparisons between jurisdictions should be made with caution.

Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Centre for Justice Statistics, Integrated Criminal Court Survey.

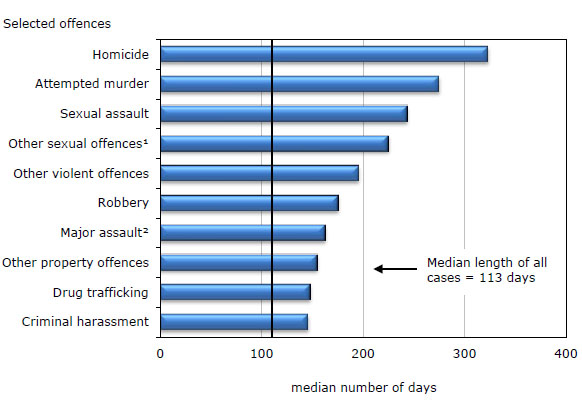

The amount of time to process youth court cases also varied by case type (Chart 10). In general, cases involving violent offences took the longest time to process. More specifically, in 2010/2011, homicide cases took the longest to complete with a median length of 323 days, followed by attempted murder cases (275 days) and sexual assault cases (244 days).

Chart 10

Median length of cases completed in youth court, by selected offence, Canada, 2010/2011

1. Includes, for example, sexual interference, invitation to sexual touching, child pornography, luring a child via a computer and sexual exploitation.

2. Includes, for example, assault with a weapon (level 2) and aggravated assault (level 3).

Note: The median represents the mid-point of the number of days taken to complete a case, from the first to last court appearance. A case is one or more charges against an accused person or company that were processed by the courts at the same time and received a final disposition.

Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Centre for Justice Statistics, Integrated Criminal Court Survey.

Summary

In 2010/2011 the number of cases completed in youth court declined for the second year in a row. The decrease in caseload occurred across the majority of jurisdictions, and across most crime categories. The majority of cases heard in youth court involved non-violent offences, with theft, Youth Criminal Justice Act offences, and break and enter being among the most common types of cases completed.

Similar to previous years, the most common decision in youth court cases was one of guilt. However, over the past 10 years the proportion of cases resulting in a guilty outcome has decreased, while the proportion of cases resulting in a stay or withdrawal has increased.

Consistent with sentencing principles under the YCJA, the proportion of youth court cases being sentenced to custody continued to decline in 2010/2011, while the proportion of youth court cases given a sentence of deferred custody and supervision has increased. Overall, probation continued to be the most common sentence handed down in youth court cases.

In general, the length of time to complete youth court cases has increased over the past 10 years, with the largest increase occurring between 2002/2003 and 2003/2004. On the whole, it took three and a half months to process a youth court case in 2010/2011.

Data source

The Integrated Criminal Court Survey (ICCS) is administered by the Canadian Centre for Justice Statistics (Statistics Canada) in collaboration with provincial and territorial government departments responsible for criminal courts in Canada. The survey collects statistical information on adult and youth court cases involving Criminal Code and other federal statute charges.Data contained in this article represent the youth court portion of the survey. The individuals involved are persons aged 12 to 17 years (up to the 18th birthday) at the time of the offence. All youth courts in Canada have reported data to the YCS since the 1991/1992 fiscal year.

The primary unit of analysis is a case. A case is defined as one or more charges against an accused person or company that were processed by the courts at the same time and received a final disposition. A case combines all charges against the same person having one or more key overlapping dates (date of offence, date of initiation, date of first appearance, date of decision, or date of sentencing) into a single case.

A case that has more than one charge is represented by the charge with the "most serious offence" (MSO). The most serious offence is selected using the following rules. First, court decisions are considered and the charge with the "most serious decision" (MSD) is selected. Court decisions for each charge in a case are ranked from most to least serious as follows: 1) guilty, 2) guilty of a lesser offence, 3) acquitted, 4) stay of proceeding, 5) withdrawn, dismissed and discharged, 6) not criminally responsible, 7) other, and 8) transfer of court jurisdiction.

Second, in cases where two or more charges result in the same MSD (e.g., guilty), Criminal Code sanctions are considered. The charge with the most serious offence type is selected according to an Offence Seriousness Scale, based on actual sentences handed down by courts in Canada.Note 15 Each offence type is ranked by looking at (a) the proportion of guilty charges where custody was imposed and (b) the average (mean) length of custody for the specific type of offence. These values are multiplied together to arrive at the final seriousness ranking for each type of offence. If, after looking at the offence seriousness scale, two or more charges remain tied then information about the sentence type and duration of the sentence are considered (e.g., custody and length of custody, then probation and length of probation, etc.).

Cases are counted according to the fiscal year in which they are completed. Each year, the ICCS database is "frozen" at the end of March for the production of court statistics pertaining to the preceding fiscal year. However, these counts do not include cases that were pending an outcome at the end of the reference period. Once an outcome is reached, or a one-year period of inactivity elapses, these cases are deemed complete and are subsequently updated and reported in the next year's release of the data. For example, upon the release of 2010/2011 data, the 2009/2010 data are updated with revisions that were determined when processing data for the next fiscal year. Data are revised once and are then permanently "frozen". Historically, updates to a previous year's numbers have resulted in an increase of about 2%.

Lastly, there are many factors that influence variations between jurisdictions. These may include Crown and police charging practices, offence distributions, and various forms of diversion programs. Therefore, any comparisons between jurisdictions should be interpreted with caution.

Detailed data tables

Table 1 Cases and charges completed in youth court, 2000/2001 to 2010/2011

Table 2 Cases completed in youth court, by province and territory, 2009/2010 and 2010/2011

Table 3 Cases completed in youth court, by type of offence, 2009/2010 and 2010/2011

Table 4 Cases completed in youth court, by type of offence and decision, Canada, 2010/2011

Table 5 Cases completed in youth court, by type of offence and selected sentence, Canada, 2010/2011

References

Brennan, Shannon and Mia Dauvergne. 2011. "Police-reported crime statistics in Canada, 2010." Juristat. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 85-002-X.

(accessed January 23, 2012).

Casavant, Lyne, Robin MacKay and Dominique Valiquet. 2008. Youth Justice Legislation in Canada. Legal and Legislative Affairs Division. Library of Parliament. PRB-08-23E. Ottawa. Canada.

(accessed February 9, 2012).

Dauvergne, Mia. 2012. "Adult criminal court statistics in Canada, 2010." Juristat. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 85-002-X.

Department of Justice Canada. 2011. The Youth Criminal Justice Act: Summary and Background. Ottawa, Canada.

(accessed February 9, 2012).

Milligan, Shelley. 2010. "Youth court statistics, 2008/2009." Juristat. Vol. 30, no. 2. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 85-002-X.

(accessed March 16, 2012).

Moyer, Sharon. 2005. A Comparison of Case Processing under the Young Offenders Act and the First Six Months of the Youth Criminal Justice Act. Department of Justice Canada.

(accessed March 16, 2012).

Public Prosecution Service of Canada. 2004. The Federal Prosecution Service Deskbook. Ottawa, Canada.

(accessed March 16, 2012).

Notes

- For information on 2010/2011 adult criminal court statistics in Canada, see Dauvergne 2012.

- Jurisdictional differences in the structure and operation of courts may have an impact on survey results. Therefore, any comparisons between jurisdictions should be made with caution.

- Youth court cases that involve more than one charge are counted according to the most serious offence rule. For further information, see Data source section.

- Reflects the accused person's age on the day the offence was alleged to have been committed.

- Excludes all cases where the age of the accused was unknown.

- Excludes all cases where the sex of the accused was unknown.

- In Newfoundland and Labrador, the terms 'acquittal' and 'dismissed' are used interchangeably, resulting in an under-count of the number of acquittals in that province. In other provinces, the number of acquittals may be over-counted due to administrative practices.

- A small proportion of cases result in other decisions including: final decisions of found not criminally responsible waived in province/territory, and waived out of province/territory. This category also includes mistrials, the court's acceptance of a special plea (e.g., "autrefois acquit"), cases which raise Charter arguments and cases where the accused was found unfit to stand trial following a fitness hearing.

- See Note 2.

- Excludes cases of probation where the length of the sentence was not known.

- Based on a subset of jurisdictions who have reported YCJA sentencing data to the ICCS since 2004/2005.

- See Note 2.

- The length of custodial sentences may be affected by time spent in pre-trial detention. For example, 'time served', the time spent in custody prior to the decision of the court and sentencing, which often occurs with more serious offences, is likely to affect the sentence length.

- See Note 2.

- The offence seriousness scale is calculated using data from both the Adult Criminal Court (ACCS) and Youth Court Survey (YCS) components of the Integrated Criminal Court Survey (ICCS) from 2002/2003 to 2006/2007.

- Date modified: